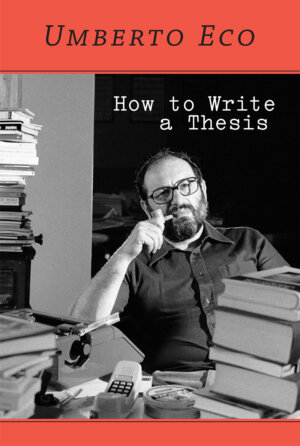

How to Write a Thesis, According to Umberto Eco

In 1977, three years before Umberto Eco’s groundbreaking novel “ The Name of the Rose ” catapulted him to international fame, the illustrious semiotician published a funny and unpretentious guide for his favorite audience: teachers and their students. Now translated into 17 languages (it finally appeared in English in 2015), “How to Write a Thesis” delivers not just practical advice for writing a thesis — from choosing the right topic (monograph or survey? ancient or contemporary?) to note-taking and mastering the final draft — but meaningful lessons that equip writers for a lifetime outside the walls of the classroom. “Your thesis is like your first love” Eco muses. “It will be difficult to forget. In the end, it will represent your first serious and rigorous academic work, and this is no small thing.”

“Full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it,” praised one critic, “the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own.” An excerpt from that chapter can be read below.

Once we have decided to whom to write (to humanity, not to the advisor), we must decide how to write, and this is quite a difficult question. If there were exhaustive rules, we would all be great writers. I could at least recommend that you rewrite your thesis many times, or that you take on other writing projects before embarking on your thesis, because writing is also a question of training. In any case, I will provide some general suggestions:

You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences. If they come into your head, write them, but then break them down. Do not be afraid to repeat the subject twice, and stay away from too many pronouns and subordinate clauses. Do not write,

The pianist Wittgenstein, brother of the well-known philosopher who wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicusthat today many consider the masterpiece of contemporary philosophy, happened to have Ravel write for him a concerto for the left hand, since he had lost the right one in the war.

Write instead,

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Since Paul was maimed of his right hand, the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

The pianist Paul Wittgenstein was the brother of the famous philosopher, author of the Tractatus. The pianist had lost his right hand in the war. For this reason the composer Maurice Ravel wrote a concerto for him that required only the left hand.

Do not write,

The Irish writer had renounced family, country, and church, and stuck to his plans. It can hardly be said of him that he was a politically committed writer, even if some have mentioned Fabian and “socialist” inclinations with respect to him. When World War II erupted, he tended to deliberately ignore the tragedy that shook Europe, and he was preoccupied solely with the writing of his last work.

Rather write,

Joyce had renounced family, country, and church. He stuck to his plans. We cannot say that Joyce was a “politically committed” writer even if some have gone so far as describing a Fabian and “socialist” Joyce. When World War II erupted, Joyce deliberately ignored the tragedy that shook Europe. His sole preoccupation was the writing of Finnegans Wake.

Even if it seems “literary,” please do not write,

When Stockhausen speaks of “clusters,” he does not have in mind Schoenberg’s series, or Webern’s series. If confronted, the German musician would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the series has ended. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. On the other hand Webern followed the strict principles of the author of A Survivor from Warsaw. Now, the author of Mantra goes well beyond. And as for the former, it is necessary to distinguish between the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio agrees: it is not possible to consider this author as a dogmatic serialist.

You will notice that, at some point, you can no longer tell who is who. In addition, defining an author through one of his works is logically incorrect. It is true that lesser critics refer to Alessandro Manzoni simply as “the author of the Betrothed,” perhaps for fear of repeating his name too many times. (This is something manuals on formal writing apparently advise against.) But the author of The Betrothed is not the biographical character Manzoni in his totality. In fact, in a certain context we could say that there is a notable difference between the author of The Betrothed and the author of Adelchi , even if they are one and the same biographically speaking and according to their birth certificate. For this reason, I would rewrite the above passage as follows:

When Stockhausen speaks of a “cluster,” he does not have in mind either the series of Schoenberg or that of Webern. If confronted, Stockhausen would not accept the requirement to avoid repeating any of the twelve notes before the end of the series. The notion of the cluster itself is structurally more unconventional than that of the series. Webern, by contrast, followed the strict principles of Schoenberg, but Stockhausen goes well beyond. And even for Webern, it is necessary to distinguish among the various phases of his oeuvre. Berio also asserts that it is not possible to think of Webern as a dogmatic serialist.

You are not e. e. cummings. Cummings was an American avant-garde poet who is known for having signed his name with lower-case initials. Naturally he used commas and periods with great thriftiness, he broke his lines into small pieces, and in short he did all the things that an avant-garde poet can and should do. But you are not an avant-garde poet. Not even if your thesis is on avant-garde poetry. If you write a thesis on Caravaggio, are you then a painter? And if you write a thesis on the style of the futurists, please do not write as a futurist writes. This is important advice because nowadays many tend to write “alternative” theses, in which the rules of critical discourse are not respected. But the language of the thesis is a metalanguage , that is, a language that speaks of other languages. A psychiatrist who describes the mentally ill does not express himself in the manner of his patients. I am not saying that it is wrong to express oneself in the manner of the so-called mentally ill. In fact, you could reasonably argue that they are the only ones who express themselves the way one should. But here you have two choices: either you do not write a thesis, and you manifest your desire to break with tradition by refusing to earn your degree, perhaps learning to play the guitar instead; or you write your thesis, but then you must explain to everyone why the language of the mentally ill is not a “crazy” language, and to do it you must use a metalanguage intelligible to all. The pseudo-poet who writes his thesis in poetry is a pitiful writer (and probably a bad poet). From Dante to Eliot and from Eliot to Sanguineti, when avant-garde poets wanted to talk about their poetry, they wrote in clear prose. And when Marx wanted to talk about workers, he did not write as a worker of his time, but as a philosopher. Then, when he wrote The Communist Manifesto with Engels in 1848, he used a fragmented journalistic style that was provocative and quite effective. Yet again, The Communist Manifesto is not written in the style of Capital, a text addressed to economists and politicians. Do not pretend to be Dante by saying that the poetic fury “dictates deep within,” and that you cannot surrender to the flat and pedestrian metalanguage of literary criticism. Are you a poet? Then do not pursue a university degree. Twentieth-century Italian poet Eugenio Montale does not have a degree, and he is a great poet nonetheless. His contemporary Carlo Emilio Gadda (who held a degree in engineering) wrote fiction in a unique style, full of dialects and stylistic idiosyncrasies; but when he wrote a manual for radio news writers, he wrote a clever, sharp, and lucid “recipe book” full of clear and accessible prose. And when Montale writes a critical article, he writes so that all can understand him, including those who do not understand his poems.

Begin new paragraphs often. Do so when logically necessary, and when the pace of the text requires it, but the more you do it, the better.

Write everything that comes into your head , but only in the first draft. You may notice that you get carried away with your inspiration, and you lose track of the center of your topic. In this case, you can remove the parenthetical sentences and the digressions, or you can put each in a note or an appendix. Your thesis exists to prove the hypothesis that you devised at the outset, not to show the breadth of your knowledge.

Use the advisor as a guinea pig. You must ensure that the advisor reads the first chapters (and eventually, all the chapters) far in advance of the deadline. His reactions may be useful to you. If the advisor is busy (or lazy), ask a friend. Ask if he understands what you are writing. Do not play the solitary genius.

Do not insist on beginning with the first chapter . Perhaps you have more documentation on chapter 4. Start there, with the nonchalance of someone who has already worked out the previous chapters. You will gain confidence. Naturally your working table of contents will anchor you, and will serve as a hypothesis that guides you.

Do not use ellipsis and exclamation points, and do not explain ironies . It is possible to use language that is referential or language that is figurative . By referential language, I mean a language that is recognized by all, in which all things are called by their most common name, and that does not lend itself to misunderstandings. “The Venice-Milan train” indicates in a referential way the same object that “The Arrow of the Lagoon” indicates figuratively. This example illustrates that “everyday” communication is possible with partially figurative language. Ideally, a critical essay or a scholarly text should be written referentially (with all terms well defined and univocal), but it can also be useful to use metaphor, irony, or litotes. Here is a referential text, followed by its transcription in figurative terms that are at least tolerable:

[ Referential version :] Krasnapolsky is not a very sharp critic of Danieli’s work. His interpretation draws meaning from the author’s text that the author probably did not intend. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky sees a symbolic expression that alludes to poetic activity. One should not trust Ritz’s critical acumen, and one should also distrust Krasnapolsky. Hilton observes that, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he adds, “Truly, two perfect critics.”

[ Figurative version :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the sharpest critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is putting words into Danieli’s mouth. Consider the line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets it as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky plays the symbolism card and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight, but Krasnapolsky should also be handled with care. As Hilton observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a tourist brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon. Truly, two perfect critics.”

You can see that the figurative version uses various rhetorical devices. First of all, the litotes: saying that you are not convinced that someone is a sharp critic means that you are convinced that he is not a sharp critic. Also, the statement “Ritz is not a prodigy of critical insight” means that he is a modest critic. Then there are the metaphors : putting words into someone’s mouth, and playing the symbolism card. The tourist brochure and the Lenten sermon are two similes , while the observation that the two authors are perfect critics is an example of irony : saying one thing to signify its opposite.

Now, we either use rhetorical figures effectively, or we do not use them at all. If we use them it is because we presume our reader is capable of catching them, and because we believe that we will appear more incisive and convincing. In this case, we should not be ashamed of them, and we should not explain them . If we think that our reader is an idiot, we should not use rhetorical figures, but if we use them and feel the need to explain them, we are essentially calling the reader an idiot. In turn, he will take revenge by calling the author an idiot. Here is how a timid writer might intervene to neutralize and excuse the rhetorical figures he uses:

[ Figurative version with reservations :] We are not convinced that Krasnapolsky is the “sharpest” critic of Danieli’s work. In reading his author, Krasnapolsky gives the impression that he is “putting words into Danieli’s mouth.” Consider Danieli’s line, “in the evening gazing at the clouds.” Ritz interprets this as a normal geographical annotation, whereas Krasnapolsky “plays the symbolism card” and sees an allusion to poetic activity. Ritz is not a “prodigy of critical insight,” but Krasnapolsky should also be “handled with care”! As Hilton ironically observes, “if Ritz’s writing seems like a vacation brochure, Krasnapolsky’s criticism reads like a Lenten sermon.” And he defines them (again with irony!) as two models of critical perfection. But all joking aside …

I am convinced that nobody could be so intellectually petit bourgeois as to conceive a passage so studded with shyness and apologetic little smiles. Of course I exaggerated in this example, and here I say that I exaggerated because it is didactically important that the parody be understood as such. In fact, many bad habits of the amateur writer are condensed into this third example. First of all, the use of quotation marks to warn the reader, “Pay attention because I am about to say something big!” Puerile. Quotation marks are generally only used to designate a direct quotation or the title of an essay or short work; to indicate that a term is jargon or slang; or that a term is being discussed in the text as a word, rather than used functionally within the sentence. Secondly, the use of the exclamation point to emphasize a statement. This is not appropriate in a critical essay. If you check the book you are reading, you will notice that I have used the exclamation mark only once or twice. It is allowed once or twice, if the purpose is to make the reader jump in his seat and call his attention to a vehement statement like, “Pay attention, never make this mistake!” But it is a good rule to speak softly. The effect will be stronger if you simply say important things. Finally, the author of the third passage draws attention to the ironies, and apologizes for using them (even if they are someone else’s). Surely, if you think that Hilton’s irony is too subtle, you can write, “Hilton states with subtle irony that we are in the presence of two perfect critics.” But the irony must be really subtle to merit such a statement. In the quoted text, after Hilton has mentioned the vacation brochure and the Lenten sermon, the irony was already evident and needed no further explanation. The same applies to the statement, “But all joking aside.” Sometimes a statement like this can be useful to abruptly change the tone of the argument, but only if you were really joking before. In this case, the author was not joking. He was attempting to use irony and metaphor, but these are serious rhetorical devices and not jokes.

You may observe that, more than once in this book, I have expressed a paradox and then warned that it was a paradox. For example, in section 2.6.1, I proposed the existence of the mythical centaur for the purpose of explaining the concept of scientific research. But I warned you of this paradox not because I thought you would have believed this proposition. On the contrary, I warned you because I was afraid that you would have doubted too much, and hence dismissed the paradox. Therefore I insisted that, despite its paradoxical form, my statement contained an important truth: that research must clearly define its object so that others can identify it, even if this object is mythical. And I made this absolutely clear because this is a didactic book in which I care more that everyone understands what I want to say than about a beautiful literary style. Had I been writing an essay, I would have pronounced the paradox without denouncing it later.

Always define a term when you introduce it for the first time . If you do not know the definition of a term, avoid using it. If it is one of the principal terms of your thesis and you are not able to define it, call it quits. You have chosen the wrong thesis (or, if you were planning to pursue further research, the wrong career).

Umberto Eco was an Italian novelist, literary critic, philosopher, semiotician, and university professor. This article is excerpted from his book “ How to Write a Thesis .”

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

How To Write a Thesis : A Witty, Irreverent & Highly Practical Guide Now Out in English">Umberto Eco’s How To Write a Thesis : A Witty, Irreverent & Highly Practical Guide Now Out in English

in Books , Education , Writing | March 23rd, 2015 5 Comments

Image by Università Reggio Calabria, released under a C BY-SA 3.0 license.

In general, the how-to book—whether on beekeeping, piano-playing, or wilderness survival—is a dubious object, always running the risk of boring readers into despairing apathy or hopelessly perplexing them with complexity. Instructional books abound, but few succeed in their mission of imparting theoretical wisdom or keen, practical skill. The best few I’ve encountered in my various roles have mostly done the former. In my days as an educator, I found abstract, discursive books like Robert Scholes’ Textual Power or poet and teacher Marie Ponsot’s lyrical Beat Not the Poor Desk infinitely more salutary than more down-to-earth books on the art of teaching. As a sometime writer of fiction, I’ve found Milan Kundera’s idiosyncratic The Art of the Novel —a book that might have been titled The Art of Kundera —a great deal more inspiring than any number of other well-meaning MFA-lite publications. And as a self-taught audio engineer, I’ve found a book called Zen and the Art of Mixing —a classic of the genre, even shorter on technical specifications than its namesake is on motorcycle maintenance—better than any other dense, diagram-filled manual.

How I wish, then, that as a onetime (longtime) grad student, I had had access to the English translation, just published this month, of Umberto Eco’s How to Write a Thesis , a guide to the production of scholarly work worth the name by the highly celebrated Italian novelist and intellectual. Written originally in Italian in 1977, before Eco’s name was well-known for such works of fiction as The Name of the Rose and Foucault’s Pendulum , How to Write Thesis is appropriately described by MIT Press as reading: “like a novel”: “opinionated… frequently irreverent, sometimes polemical, and often hilarious.”

For example, in the second part of his introduction, after a rather dry definition of the academic “thesis,” Eco dissuades a certain type of possible reader from his book, those students “who are forced to write a thesis so that they may graduate quickly and obtain the career advancement that originally motivated their university enrollment.” These students, he writes, some of whom “may be as old as 40” (gasp), “will ask for instructions on how to write a thesis in a month .” To them, he recommends two pieces of advice, in full knowledge that both are clearly “ illegal ”:

(a) Invest a reasonable amount of money in having a thesis written by a second party. (b) Copy a thesis that was written a few years prior for another institution. (It is better not to copy a book currently in print, even if it was written in a foreign language. If the professor is even minimally informed on the topic, he will be aware of the book’s existence.

Eco goes on to say that “even plagiarizing a thesis requires an intelligent research effort,” a caveat, I suppose, for those too thoughtless or lazy even to put the required effort into academic dishonesty.

Instead, he writes for “students who want to do rigorous work” and “want to write a thesis that will provide a certain intellectual satisfaction.” Eco doesn’t allow for the fact that these groups may not be mutually exclusive, but no matter. His style is loose and conversational, and the unseriousness of his dogmatic assertions belies the liberating tenor of his advice. For all of the fun Eco has discussing the whys and wherefores of academic writing, he also dispenses a wealth of practical hows, making his book a rarity among the small pool of readable How-tos. For example, Eco offers us “Four Obvious Rules for Choosing a Thesis Topic,” the very bedrock of a doctoral (or masters) project, on which said project truly stands or falls:

1. The topic should reflect your previous studies and experience. It should be related to your completed courses; your other research; and your political, cultural, or religious experience. 2. The necessary sources should be materially accessible. You should be near enough to the sources for convenient access, and you should have the permission you need to access them. 3. The necessary sources should be manageable. In other words, you should have the ability, experience, and background knowledge needed to understand the sources. 4. You should have some experience with the methodological framework that you will use in the thesis. For example, if your thesis topic requires you to analyze a Bach violin sonata, you should be versed in music theory and analysis.

Having suffered the throes of proposing, then actually writing, an academic thesis, I can say without reservation that, unlike Eco’s encouragement to plagiarism, these four rules are not only helpful, but necessary, and not nearly as obvious as they appear. Eco goes on in the following chapter, “Choosing the Topic,” to present many examples, general and specific, of how this is so.

Much of the remainder of Eco’s book—though written in as lively a style and shot through with witticisms and profundity—is gravely outdated in its minute descriptions of research methods and formatting and style guides. This is pre-internet, and technology has—sadly in many cases—made redundant much of the footwork he discusses. That said, his startling takes on such topics as “Must You Read Books?,” “Academic Humility,” “The Audience,” and “How to Write” again offer indispensable ways of thinking about scholarly work that one generally arrives at only, if at all, at the completion of a long, painful, and mostly bewildering course of writing and research.

FYI: You can download Eco’s book, How to Write a Thesis, as a free audiobook if you want to try out Audible.com’s no-risk, 30-day free trial program. Find details here .

Related Content:

The Books You Think Every Intelligent Person Should Read: Crime and Punishment, Moby-Dick & Beyond (Many Free Online)

“Lol My Thesis” Showcases Painfully Hilarious Attempts to Sum up Years of Academic Work in One Sentence

Steven Pinker Uses Theories from Evolutionary Biology to Explain Why Academic Writing is So Bad

Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School: Apply & Learn the Art of Guerilla Filmmaking & Lock-Picking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (5) |

Related posts:

Comments (5), 5 comments so far.

Wish I’d had this when I was writing my dissertation.

Wow, it took 38 years… Second-hand paperback copies were available when I wrote my MA dissertation…

One remark: the “thesis” Eco is writing about in this book wasn’t the actual PhD thesis. In Italy in the late seventies you only had four-years all inclusive “Bachelor’s/Master’s/Phd’s” programs, ending with a thesis (“Tesi di laurea”). This presupposed that the final research work (product of about a year of labor) was potentially publishable… and in fact Eco published his thesis on Thomas’ aesthetics. This didn’t necessarily mean less quality, quite the opposite: try to think at the sentence “If the professor is even minimally informed on the topic, he will be aware of the book’s existence.” today!

So, the burning question — is the book available online, in English?

Patently a priori knowledge. That Eco invested time and effort in producing is a statement of his dire thoughts about the future of the human intellect in the digital/ nascent AI age.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Summary: "How to write a thesis" by Umberto Eco

This post is part of my "research" series.

Eco, Umberto. How to Write a Thesis . MIT Press, 2015. Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina. Original publication: Come si fa una tesi di laurea: le materie umanistiche . Bompiani, 1977.

In one paragraph

Table of contents, an alternative outline, rigor and scope, an experiment in the library of alessandria, academic pride, why you have to annotate, structure of the bibliography, general commentary.

Mainly, because it was there. I read it years ago, and it stuck with me. I also respect Eco. I've enjoyed several of his novels, and I know he is well regarded as an academic.

Eco's advices how to write a rigorous (read "exhaustive") piece of original research in 6 months to 3 years, depending on ambition. Main skills taught: selecting a topic, using a library, organizing material, producing an italian-university-standard thesis manuscript. Note that Eco does not explain how to actually come up with or prove the thesis, he just focuses on support skills.

Broadly, how this book reads from my perspective.

The good, the bad, and the extremely revealing. Direct quotations in no particular order. Some of these ideas may not be discussed at length, but it still seemed worthwile to put them here.

[…] the rigor of a thesis is more important than it's scope […] it is better to build a serious trading card collection from 1960 to the present than to create a cursory art collection. The thesis shares this same criterion.

At the very least, writing a thesis is like training the memory. […] If a student works rigorously, no topic is truly foolish, and the student can draw useful conclusions even from a remote or peripheral topic.

[…] realistically I would not choose a topic unless I already knew: (a) where I could find the sources, (b) whether they were easily accessible, and (c) whether I was capable of fully understanding them.

(s3.1, p47)

This is my main beef with this work. As Natalie Wynn (of ContraPoints fame) puts it "[…] you end up having to narrow in on a research topic that’s really specialized. So specialized, in fact, that it strains the human ability to give a shit."

Now that we have imagined this hypothetical picture, I will try to put myself in this student’s shoes. In fact, I am writing these very lines in a small town in southern Monferrato, 14.5 miles away from Alessandria, a city with 90,000 inhabitants, a public library, an art gallery, and a museum. The closest university is one hour away in Genoa, and in an hour and a half I can travel to Turin or Pavia, and in three to Bologna. This location already puts me in a privileged situation, but for this experiment I will not take advantage of the university libraries. I will work only in Alessandria.

(s3.2.4, p80)

This entire section is a gem. Eco grabs you by the arm and shows you how he does it, step by step.

On your specific topic, you are humanity’s functionary who speaks in the collective voice. Be humble and prudent before opening your mouth, but once you open it, be dignified and proud. […] on the topic you have chosen […] you must be the utmost living authority.

(s5.6, p184)

[How long does it take to write a thesis?] Let us state from the outset: no longer than three years and no less than six months. This period includes not just the time necessary to write the final draft, which may take only a month or two weeks, depending on the student’s work habits. Instead, this period begins at the genesis of the first idea and ends at the delivery of the final work.

(s2.4, p17)

A good researcher can enter a library without having the faintest idea about scholarship on a particular topic, and exit knowing more about it, if only a little more.

(s3.2.1, p54)

Readings index cards are useful for organizing critical literature. I would not use index cards, or at least not the same kind of index cards, to organize primary sources.

(s4.2.2, p123)

[Filing references to primary sources] would require a huge effort, because you would have to practically catalog the texts page by page.

(s4.2.2, p125)

As you can see, the format [of the final bibliography] will change according to the thesis type, and the goal is to organize your bibliography so that it allows readers to identify and distinguish between primary and secondary sources, rigorous critical studies and less reliable secondary sources, etc.

(s6.2, 209-210)

This fits into a more general theme of academic transparency and fair play. You write your Table of Contents to help your reader navigate. You write your bibliography to give your reader access to all your sources; to either reinterpret them, or criticize your choice of material.

Advice on topic selection is entirely irrelevant to me. Sometimes, you face a problem and just have to give it your best.

The index-card files that Eco describes in this book are very similar to the Zettelkasten system 1 2 . Eco is a bit abstract about how to apply his system applies to stuff that isn't books, but he shows a few example cards from his own research. Worth looking over.

s3.2.4 "An Experiment in the Library of Alessandria" is Eco picking a topic and showing you how he puts together a bibliography . Very instructive and very welcome. Abstract advice is all well and good, but I'll take commentated examples over them any day.

Eco never defines rigor, and I don't quite understand what he means by it. He claims that thesis work must be rigorous, and he claims that thesis work must be honest, transparent, exhaustive, and original. But he doesn't explain which attributes are parts of rigor, and which are other things a thesis must have. The only exception is exhaustiveness 3 .

"Zettelkasten" or "Slip-box" is a system of note-taking in which index cards are inserted at arbitrary positions in a collection through the use of a system of branching codes (if you want to add a note between 1 and 2 , you can always mark it 1a ). This is mean to allow related ideas to cluster with minimal friction. ↩

Ahrens, Sönke. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking: For Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers . North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace, 2017. ↩

"[…] the rigor of a thesis is more important than it's scope […] it is better to build a serious trading card collection from 1960 to the present than to create a cursory art collection. The thesis shares this same criterion." s1.3, p5 ↩

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

How to write a thesis

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,113 Previews

55 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station14.cebu on December 20, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco review – offering hope to harried slackers

Who better to help with essay neurosis than a venerable public intellectual and author?

A s a young scholar, Umberto Eco trained himself to complete everyday and academic tasks at speed; he quickened his pace between appointments, devoured pages at a glance, treated each tiny interstice of the working day as a chance to judge, reflect or compose. One imagines even his beard was a timesaving outgrowth of impatient ambition. Such deliberate habits in a writer suggest a sort of performance, and Eco has enjoyed showing interviewers around the three studies where he works: one each devoted to reading, typing and writing by hand. Such is his finicky pleasure in his own process that belated Anglophone readers should not be surprised that Eco once published a guide to researching and writing a dissertation. How to Write a Thesis has been in print in Italy, almost unchanged, since 1977. Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina, it is at once an eminently wise and useful manual, and a museum of dying or obsolete skills. Not to mention ancient office products.

How to Write a Thesis appeared when Eco was already established as semiotician, pop-culture analyst and author of books about the aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas and the medievalism of James Joyce . Three years later The Name of the Rose turned the public intellectual into a purveyor of ingenious if turgid fiction. Eco’s first novel and his student-writing guide have this in common: they imagine a hasty unlearned youth being led around the library by a middle-aged scholar-sleuth who may himself be on the wrong track. Eco sets out to instruct a student on the edge of panic, and he is more than a little sarcastic about how the tyro scholar may have arrived at this state of emergency: “Let us try to imagine the extreme situation of a working Italian student who has attended the university very little during his first three years of study.”

Many readers may recognise themselves – and teachers their students – in the harried slacker to whom How to Write a Thesis offers practical advice. Eco was writing in the context of an old and anomalous academic culture, faced in the 1970s with conflicting bureaucratic demands and potentially crippling (for students, for knowledge) economic circumstances. The laurea was then the terminal degree – how that phrase haunts the young researcher – at Italian universities, and involved a thesis which took the student several months, at worst years, of extra labour. Many candidates had written little or nothing as undergraduates, so balked at extended prose composition, let alone the rigours of a dissertation. Some simply could not afford the time, books or travel required to complete an ambitious piece of research. Others, distracted by the student militancy of the decade, found out too late that the radical’s skills of debate, polemic or protest were not exactly those required for dogged scholarship, or by a state system. To all these students, Eco’s little book offered some hope.

One of the admirable impulses behind How to Write a Thesis is this sense that Eco fully understands the many reasons for academic failure: from student poverty, through institutional obtuseness to the crushing “thesis neurosis” that afflicts the type – mea maxima culpa , as it happens – who “uses his thesis as an alibi to avoid other challenges in his life”. Eco is a generous and genial teacher, but he demands some strict choices at the outset. The student must commit to six months at least of sustained work, must give up the egotism that lights on madly ambitious thesis topics and arrogantly “creative” methods, and must practise instead a form of “academic humility”. Any subject, no matter how modest, may yield real knowledge; any writer (Eco is mostly discussing humanities research), however unfashionable or obscure, could turn out to hold the key. Much of How to Write a Thesis is consequently concerned with lowering expectations and limiting the amount of material the student will have to wrangle: “It is better to build a serious trading card collection from 1960 to the present day than to create a cursory art collection.”

That might sound a less than enthralling invitation to the vaulting Borgesian precincts of research and writing. But Eco is working on the principle, which almost every writer must learn, that the best intellectual fun is to be had getting lost with a map in your pocket. In 1977 that map was made of paper, and the editors of this new English edition have not disguised the complex analogue methods Eco recommends for marshalling notes and bibliographic entries. (This does happen to venerable writing manuals, with awkward results: I’ve seen an incompletely updated edition of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style , from the 1990s, that has the novice writer moving oddly between typewriter and computer.) At the heart of Eco’s process is the humble index card, on which the student is enjoined to record all the details of books and articles read, but also quotations, summaries and even initial forays into writing proper. Multiple stacks of index cards – Eco imagines the student hefting them around between libraries – form the substrate on which thought and composition are built. In what is surely a vastly optimistic aside, Eco remarks: “You will have an organised system to hand to someone who is working on a similar topic.”

Who knows how effective such advice can ever really be. As I write this, I can still put my hand to a pack of large white index cards I bought 20 years ago, in a fit of nearly fatal PhD anxiety, and never once used. Although the texture of the lost world Eco captures is almost moving now – the scribbled cards, the photocopies, the endless retyping of drafts – it is the state of mind he prescribes that matters, not the moraine of vintage technology that supports it. “The pattern of the thing precedes the thing,” Nabokov said about his own Bristol index cards and Blackwing pencils. You could subtract the last two words from the title of Eco’s book, because at its best it’s a primer in the architectural pleasures of any writing that aspires “to build an object that in principle will serve others”. If Eco is a less inspiring guide to the shape and finish of actual sentences – there are huffy passages about scholars who aspire to prose experiment – that is to be expected in a critic whose style is forever outshone by the likes of Barthes and Calvino . But all three are in love with plans and schemes, which are half of writing, and How to Write a Thesis is a schemer’s dream.

- Umberto Eco

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Latest Posts

- LSE Authors

- Choose a Book for Review

- Submit a Book for Review

- Bookshop Guides

Dr Vanessa Longden

March 31st, 2015, book review: how to write a thesis by umberto eco.

7 comments | 4 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Now in its twenty-third edition in Italy and translated into seventeen languages, How to Write a Thesis has become a classic. This is its first, long overdue publication in English. Vanessa Longden thinks that in addition to its witty one-liners, Eco’s book contains the bare bones on which to build research.

How to Write a Thesis . Umberto Eco (trans. by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina). MIT Press. March 2015.

This book will not tell you what to write and Eco is more than frank about this: if you are after a ‘quick fix’ then you should not undertake a PhD, as you would be pursuing it for the wrong motivations. What Eco provides, in addition to witty one-liners – “You are not Proust. Do not write long sentences”; and “You are not e.e. cummings…you are not an avant garde poet” – are the bare bones on which to build research. Eco highlights different avenues of investigation and presents the demands and commitments – ranging from financial motivations to more personal attributes like the candidate’s age and maturity – which may affect students and their research as they embark on their academic careers.

Undertaking independent research should be an adventure: “If you write your thesis with gusto, you will be inspired to continue,” says Eco. Your thesis will not be an easy journey, nor should it be. The publication acts as a methodical guide which clarifies ‘The Definition and Purpose of a Thesis’; choosing a respective topic (be it a Monograph or Survey, Historical or Theoretical, Ancient or Contemporary); and through to conducting research and writing the final piece. Your thesis should ultimately “activate your intellectual metabolism” and leave you hungry for more.

Eco does not disappoint, he wrote this book for a hypothetical student without any experience and this is important to remember. It is all too easy to be swept along by Eco’s dynamic thought process. For instance, he demonstrates in An Experiment in the Library of Alessandria that students are still able to construct a preliminary bibliography using limited library resources and within a narrow timeframe (nine hours to be exact). Here, reading the rapidity of Eco’s thinking can at times be a little intimidating and students must remember that research should be taken in its stride. Reading another’s thoughts in linear progression is different to actual contemplation which can often be erratic and unexpected; but no less valuable. To put it a different way, early researchers must not be discouraged if their revelations do not appear as prompt as Eco’s. Their approach to inquiry will develop over time with critical reflection and would be partially dependent “on the researcher’s psychological structure”.

Despite developments in technology, digital word processing, and online archival and cataloguing systems, Chapter 4 appears somewhat novel in that it features reproductions of Eco’s index cards supported by his handwritten annotations, colour coding and cross-references. What he presents is a comprehensive and systematic mode of organisation, the index cards are compiled into numerous categories: bibliographic information, summary of books or articles, ideas files, and quotations to which you wish to return. This method remains beneficial as it enables students to reacquaint themselves with the tactility of their source material. Instead of becoming distanced digitally through computer screens, students’ physical interaction with their source-base plays an intrinsic relationship in the formulation of new ideas.

The best ideas may not come from major authors

This is just one of Eco’s poignant and important acknowledgements, that inspiration can be found in the most unlikely of places and may even arise from those whose ideologies and thoughts are very different from our own. Eco says, “Even the sternest opponent can suggest some ideas to us. It may depend on the weather, the season, and the hour of the day”. Such inspiration and interpretations are largely subjective; recognising this and learning to listen to others is a valuable skill to possess and should be developed as one embarks on their research. Similarly, Eco writes about ‘Academic Pride’ at the end of Chapter 5. This section concerns confidence in writing and feeling accomplished in one’s efforts and diligence.

When you speak, you are the expert…you are humanity’s functionary who speaks in the collective voice. Be humble and prudent before opening your mouth, but once you open it, be dignified and proud.

For Eco, intellectual satisfaction and stimulation, in addition to genuine interest, should be the motivators of academic research. This book is accessible enough to benefit students at various stages of their academic careers, whether at undergraduate, masters or doctoral level. It will also serve as a valuable teaching resource as Eco makes readers aware of the skills that are required in order to perform thorough and quality research. In most cases, How to Write a Thesis serves as a reminder and a token of reassurance; proposing that many readers will already possess the techniques which Eco describes. Thus this book bestows more than guidance, it makes the reader aware of their own capabilities.

Research is and remains, in Eco’s words, “a mysterious adventure that inspires passion and holds many surprises”. I could not agree more. Research can be elusive and it can bestow extraordinary clarity. People are united and divided by research. Writing is just as much a “social act” as an individual endeavour. We continue to collaborate with the texts of the past, shaping and elaborating others’ perspectives in order to expand the borders of a collective culture. Ideas coordinate, they “travel freely, migrate, disappear and reappear”. If for a time researchers are “lost in the woods” they can take solace in the fact that their surroundings will no longer appear as daunting.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

About the author

Vanessa Longden completed her doctorate in Visual Culture, funded by The Leverhulme Trust, at Durham University in 2019. Her thesis, ‘Sensual Sites, Dust and Displacement: The Photographic Spaces of Francesca Woodman’, examines Woodman's self-representational photography to expose the complex relationship between body and place. She is currently a Board Member for the Doctoral and Early Career Research Network (DECR) with the Association for Art History.

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – Book Review: How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco

- Pingback: Book Review: How to Write a Thesis

- Pingback: کتابخوان » اوبرتو اکو، معنی پول، و چرا نرخ سود بانکی پایین است

- Pingback: Book Review: A Survival Kit for Doctoral Students and Their Supervisors: Traveling the Landscape of Research by Lene Tanggaard and Charlotte Wegener | LSE Review of Books

- Pingback: Author Interview: ‘Not Just Peanuts’ with Dr Paolo Dini and Mario Barile | LSE Review of Books

- Pingback: Impact of Social Sciences – Book Review: A Survival Kit for Doctoral Students and Their Supervisors: Traveling the Landscape of Research by Lene Tanggaard and Charlotte Wegener

- Pingback: Reading List: 10 Recommended Academic Books Published in Translation | LSE Review of Books

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

Book Review: Crumpled Paper Boat: Experiments in Ethnographic Writing edited by Anand Pandian and Stuart McLean

September 27th, 2017.

Book Review: Getting the Most out of Your Doctorate: The Importance of Supervision, Networking and Becoming a Global Academic edited by Mollie Dollinger

August 7th, 2019.

Book Review: The Good University: What Universities Actually Do and Why It’s Time for Radical Change by Raewyn Connell

August 22nd, 2019.

Book Review: Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters by Les Back

May 20th, 2016, subscribe via email.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

How to Write a Thesis, by Umberto Eco

This guide gets right to the heart of the virtues that make a scholar, robert eaglestone discovers.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

These seem to be very bad times for graduate research students in the arts and humanities, the intended audience for this book. The job market is not great; funding is scarce; casualisation, which might appear to serve grad students but actually exploits them, proceeds apace; the smooth, high walls of the ivory tower seem ever more exclusive and imposing; the groves of academe (odd, I’ve always thought, to have groves inside a tower) ever more remote. Even from the pages of Times Higher Education , our little world’s local paper, opinion pieces declare that, to prevent them getting “exalted notions of themselves” (forfend!), researchers in the arts and humanities should realise that they are simply “trainspotters in their field” about whom no one cares (wait: trainspotters in a…field?). Instead of doing research, it’s argued, they should simply teach, concentrating, as Jorge of Burgos demands, in Umberto Eco’s bestselling 1980 novel The Name of the Rose , on “the preservation of knowledge” or at best “a continuous and sublime recapitulation” of what is known.

Into this bleak picture comes the first English translation of Eco’s How to Write a Thesis , continuously in print in Italy since 1977. That was a long time ago in academia, and, at first sight, lots of this book looks just useless, rooted in its historic and specific Italian context. Who uses index cards any more? (I mean, I used to, but I wrote my PhD on a computer with no hard drive, using 5¼-inch diskettes, when the internet was still for swapping equations at Cern or firing nukes at Russia.) Who has typists copy up their thesis? The sections on using libraries and research sources sound like an account of a lost, antediluvian culture.

Just before we throw this book away, or donate it to some dusty museum of intellectual life along with the doctoral theses and career hopes of our graduate students, let’s do what it is that we humanists are trained by our research to do: not just recapitulate what “we all know”, but – you remember – go a little slower, read a bit closer, look deeper, think more. It’s then that we can see the reasons for the publication of this book, in this clear and easily read translation by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina. Indeed, once some of the dust has been gently blown from the pages (and this itself is a useful research exercise), we realise that How to Write a Thesis is full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it, illustrated with lucid examples and – significantly – explanations of why , by one of the great researchers and writers in the post-war humanities.

Most of the advice is gloriously practical: how to organise your primary resources; lists of common academic abbreviations (of course, some are easily fig. ed. out: others are harder; cf., passim , etc); how to and why to narrow down a topic (because “the rigour of a thesis is more important than its scope”); why it’s not only normal but productive to keep revising the contents and structure of your thesis; how to avoid being exploited by your advisers; how to reference; why you should check the sources of other people’s quotations. More, too, in this dense book. Eco explores common traps: for example, the “alibi of photocopies” (and, we can add, scans, PDFs and so on) (“there are many things I do not know because I photocopied a text and then relaxed as if I had read it”). He stresses how “the capacity to identify problems, confront them methodically, and articulate them systematically in expository detail” in a thesis is vital for employment outside universities (“transparency about transferable skills”, ugh, we might say). And while index cards themselves may be antiquated, the idea behind having files for bibliography, quotations, what to read and ideas that strike you is not. Best of all, the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own. Do not photocopy or scan this section (it’s pp. 145-184, by the way).

While lots of the advice is hands-on (“begin new paragraphs often”), some is more metaphysical. Writing a thesis involves learning academic humility, the “knowledge that anyone can teach us something”. Eco illustrates this with a beautiful story of how a chance remark in a century-old book, badly written and full of preconceived ideas, by Vallet, an abbot, gave him a vital insight for his own thesis. And then, demonstrating the complex ways that work and intellectual inspiration are related, he tells of discovering years later, on returning to the book, that while the insight was not there on the page at all, somehow, as a student, he had himself taken it from the book: “is this not also what we ask from a teacher, to provoke us to invent ideas?” Conversely, Eco suggests that in writing, one should have a degree of pride: on “your specific topic, you are humanity’s functionary who speaks in the collective voice. Be humble and prudent before opening your mouth, but once you open it, be dignified and proud” (or, if this is too much, at least “do not whine and be complex-ridden, because it is annoying”). Most of all, undertake a thesis, he says, with gusto, with enjoyment: it is not a “meaningless ritual” but something more.

The “something more”, without Eco ever declaring it, is the true subject of the book: learning, through the concrete practicalities of writing a thesis, the virtues that research teaches us. The philosopher Bernard Williams argued that the “authority of academics” must be rooted in the virtues of accuracy and sincerity: academics “take care, and they do not lie”. It’s true that understanding how these virtues apply in the arts and humanities is more complicated than in some areas of university research, in part because, in our constant dialogue about humanity’s ever-changing self-understanding, terms such as “truth”, “sincerity” and “virtue” are part of the dialogue and not fixed points. But the virtues are there, and one way – one very good way – to learn them is by writing a thesis. So, How to Write a Thesis is really: how to be an academic.

This is part of the answer to those who think that focusing on research makes us bad teachers: at their very deepest roots, both research and teaching in universities rely not only on subject knowledge but on the virtues of sincerity and accuracy, taught through research. But there’s more: the paradox – brought into sharp focus by How to Write a Thesis – that even with a PhD, you never properly qualify. Even eminent professors remain, in a way, students for ever, with more to research, more to explore just over there . And the surprising fact is that the people who remember daily the experience of doing research, who know that despite their degrees, titles and fancy hats, they, too, are really only students: these are the best people to teach other students. Whisper it – it’s not politic to say it aloud – but that’s what makes universities special places. Our graduate students intuit this, so help them scale the tower’s walls (so as to toil in the incongruously situated groves) by giving them this book.

Robert Eaglestone is professor of contemporary literature and thought, Royal Holloway, University of London . In 2014 he won a National Teaching Fellowship Award.

How to Write a Thesis

By Umberto Eco Translated by Caterina Mongiat Farina and Geoff Farina MIT Press, 256pp, £13.95 ISBN 9780262527132 Published 24 April 2015

First published in 1977, linguist and philosopher Umberto Eco’s Come si fa una tesi di laurea: le materie umanistiche is now in its 23rd edition in the original Italian. It has been translated into 17 languages, including Farsi, Russian and Chinese, and now finally into English as How to Write a Thesis .

Eco, who is president of the Scuola Superiore di Studi Umanistici at the University of Bologna , was born in 1932 in Alessandria in Piedmont, northern Italy. He studied medieval philosophy and literature at the University of Turin , where he would later lecture. His first book, Il problema estetico in San Tommaso (1956), drew on his own doctoral thesis.

In addition to the acclaim that has greeted his scholarly work, Eco’s fiction has brought him widespread popular recognition, most notably with The Name of the Rose (1980) and Foucault’s Pendulum (1988). His latest novel, Numero Zero , will be published in English in November.

He observed to the Harvard Crimson that he “started by considering myself a scholar who worked six days a week and wrote novels on Sundays. And I thought at the beginning that there was no relationship between my novels and my academic work. Then, reading critics, [I saw that] they found connections.”

Asked in a recent New York Times interview about his legacy, Eco said: “Every writer, every artist, every musician, scientist is profoundly interested in the survival of his or her work after their death. Otherwise they would be idiots.

“Do you believe that Raphael was not interested in what happened to his paintings after his death? It’s another side of the normal human desire to survive personally in some way…[it] is essential if you work on something creative to have this hope. Otherwise you are only a person doing something to make money, to have women and champagne.”

Eco’s dry wit has supplied countless well-loved quips. A number of them, in a variety of languages, have been obligingly assembled on the author’s own website .

Karen Shook

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Reader's comments (3)

You might also like.

How to win the citation game without becoming a cynic

Boosting your publication metrics need not come at the expense of your integrity if you bear in mind these 10 tips, says Adrian Furnham

The OfS’ free speech guidance for English universities goes too far

The regulator’s example scenarios fail to acknowledge the harm that even lawful speech can cause on campus, say Naomi Waltham-Smith and James Murray

Evaristo fears Goldsmiths cuts imperil black literature master’s

Booker Prize-winning author is latest arts leader to speak out against job shedding at celebrated university

Narrow thinking ignores fallout from REF open access book mandate

Proposed changes to how scholars publish show little awareness of how they will profoundly reshape academic life, says David Lund

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $13.99 $13.99 FREE delivery: Monday, April 29 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $12.99

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

How to Write a Thesis (Mit Press) Paperback – March 6, 2015

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 256 pages

- Language English

- Publisher The MIT Press

- Publication date March 6, 2015

- Dimensions 5.5 x 0.55 x 8 inches

- ISBN-10 0262527138

- ISBN-13 978-0262527132

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

How to Write a Thesis is full of friendly, no-bullshit, entry-level advice on what to do and how to do it, illustrated with lucid examples and—significantly—explanations of why, by one of the great researchers and writers in the post-war humanities … Best of all, the absolutely superb chapter on how to write is worth triple the price of admission on its own.

How to Write a Thesis remains valuable after all this time largely thanks to the spirit of Eco's advice. It is witty but sober, genial but demanding—and remarkably uncynical about the rewards of the thesis, both for the person writing it and for the enterprise of scholarship itself.... Some of Eco's advice is, if anything, even more valuable now, given the ubiquity and seeming omniscience of our digital tools.... Eco's humor never detracts from his serious intent. And anyway, even the sardonic pointers on cheating are instructive in their way.

Eco is a first-rate storyteller and unpretentious instructor who thrives on describing the twists and turns of research projects as well as how to avoid accusations of plagiarism.

The book's enduring appeal—the reason it might interest someone whose life no longer demands the writing of anything longer than an e-mail—has little to do with the rigors of undergraduate honors requirements. Instead, it's about what, in Eco's rhapsodic and often funny book, the thesis represents: a magical process of self-realization, a kind of careful, curious engagement with the world that need not end in one's early twenties. 'Your thesis,' Eco foretells, 'is like your first love: it will be difficult to forget.' By mastering the demands and protocols of the fusty old thesis, Eco passionately demonstrates, we become equipped for a world outside ourselves—a world of ideas, philosophies, and debates.

Well beyond the completion of the thesis, Eco's manual makes for pleasant reading and is deserving of a place on the desks of scholars and professional writers. Even sections such as that recommending the combinatory system of handwritten index cards, while outdated in the digital age, can propose a helpful exercise in critical thinking, and add a certain vintage appeal to the book.

How to Write a Thesis has become a classic.

About the Author

Product details.

- Publisher : The MIT Press; Translation edition (March 6, 2015)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 256 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0262527138

- ISBN-13 : 978-0262527132

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 0.55 x 8 inches

- #31 in Education Research (Books)

- #103 in Words, Language & Grammar Reference

- #1,792 in Motivational Self-Help (Books)

About the author

Umberto eco.

Umberto Eco (born 5 January 1932) is an Italian novelist, medievalist, semiotician, philosopher, and literary critic.

He is the author of several bestselling novels, The Name of The Rose, Foucault's Pendulum, The Island of The Day Before, and Baudolino. His collections of essays include Five Moral Pieces, Kant and the Platypus, Serendipities, Travels In Hyperreality, and How To Travel With a Salmon and Other Essays.

He has also written academic texts and children's books.

Photography (c) Università Reggio Calabria

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Book Notes, Summary and Review: How to Write a Thesis by Umberto Eco

Summary notes.

I've been playing around with the idea of publishing long-form articles, or essays, onto this website. Mainly because I felt that one of my greatest struggles in writing was organizing and structuring what I've written.

My ideas are often scattered. Writing longer articles, in my view, will help me train this muscle of writing more coherently. I was researching on books that may help me with this problem, and came across Umberto Eco's How to Write a Thesis .

While this book wasn't what I was exactly looking for, it did offer me new insights on academic writing, as well as made me consider how I might approach my Honors Project in University.

What Is a Thesis?

According to Eco, a thesis is a "typewritten manuscript, usually 100 to 400 pages in length, in which the student addresses a particular problem in his chosen field". A student ideally will spend a minimum of 6 months to a maximum of 3 years on his thesis.

There are generally two directions a student can take his or her thesis towards:

- A paper that offers new insights through unique research on a particular topic. He or she may discuss relevant literature on their thesis topic, but the overall emphasis of the paper is still on the results of their individual research.

- A paper that consolidates the majority of the existing critical literature on a particular topic. He or she will explain the literature, link various perspectives together, and offer an intelligent review.

The purpose of theses is not to show that the student did his or her homework. That's not it. Instead students write a thesis to demonstrate that they can create something out of their education.

The Usefulness of a Thesis

Writing a thesis develops valuable research skills that will stay with you forever. For example:

- Collect documents on a topic.

- Define a precise topic to write on.