Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

How to Write the Scope of the Study

- By DiscoverPhDs

- August 26, 2020

What is the Scope of the Study?

The scope of the study refers to the boundaries within which your research project will be performed; this is sometimes also called the scope of research. To define the scope of the study is to define all aspects that will be considered in your research project. It is also just as important to make clear what aspects will not be covered; i.e. what is outside of the scope of the study.

Why is the Scope of the Study Important?

The scope of the study is always considered and agreed upon in the early stages of the project, before any data collection or experimental work has started. This is important because it focuses the work of the proposed study down to what is practically achievable within a given timeframe.

A well-defined research or study scope enables a researcher to give clarity to the study outcomes that are to be investigated. It makes clear why specific data points have been collected whilst others have been excluded.

Without this, it is difficult to define an end point for a research project since no limits have been defined on the work that could take place. Similarly, it can also make the approach to answering a research question too open ended.

How do you Write the Scope of the Study?

In order to write the scope of the study that you plan to perform, you must be clear on the research parameters that you will and won’t consider. These parameters usually consist of the sample size, the duration, inclusion and exclusion criteria, the methodology and any geographical or monetary constraints.

Each of these parameters will have limits placed on them so that the study can practically be performed, and the results interpreted relative to the limitations that have been defined. These parameters will also help to shape the direction of each research question you consider.

The term limitations’ is often used together with the scope of the study to describe the constraints of any parameters that are considered and also to clarify which parameters have not been considered at all. Make sure you get the balance right here between not making the scope too broad and unachievable, and it not being too restrictive, resulting in a lack of useful data.

The sample size is a commonly used parameter in the definition of the research scope. For example, a research project involving human participants may define at the start of the study that 100 participants will be recruited. This number will be determined based on an understanding of the difficulty in recruiting participants to studies and an agreement of an acceptable period of time in which to recruit this number.

Any results that are obtained by the research group can then be interpreted by others with the knowledge that the study was capped to 100 participants and an acceptance of this as a limitation of the study. In other words, it is acknowledged that recruiting 100 rather than 1,000 participants has limited the amount of data that could be collected, however this is an acceptable limitation due to the known difficulties in recruiting so many participants (e.g. the significant period of time it would take and the costs associated with this).

Example of a Scope of the Study

The follow is a (hypothetical) example of the definition of the scope of the study, with the research question investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health.

Whilst the immediate negative health problems related to the COVID-19 pandemic have been well documented, the impact of the virus on the mental health (MH) of young adults (age 18-24 years) is poorly understood. The aim of this study is to report on MH changes in population group due to the pandemic.

The scope of the study is limited to recruiting 100 volunteers between the ages of 18 and 24 who will be contacted using their university email accounts. This recruitment period will last for a maximum of 2 months and will end when either 100 volunteers have been recruited or 2 months have passed. Each volunteer to the study will be asked to complete a short questionnaire in order to evaluate any changes in their MH.

From this example we can immediately see that the scope of the study has placed a constraint on the sample size to be used and/or the time frame for recruitment of volunteers. It has also introduced a limitation by only opening recruitment to people that have university emails; i.e. anyone that does not attend university will be excluded from this study.

This may be an important factor when interpreting the results of this study; the comparison of MH during the pandemic between those that do and do not attend university, is therefore outside the scope of the study here. We are also told that the methodology used to assess any changes in MH are via a questionnaire. This is a clear definition of how the outcome measure will be investigated and any other methods are not within the scope of research and their exclusion may be a limitation of the study.

The scope of the study is important to define as it enables a researcher to focus their research to within achievable parameters.

Find out the different dissertation and thesis binding options, which is best, advantages and disadvantages, typical costs, popular services and more.

A thesis and dissertation appendix contains additional information which supports your main arguments. Find out what they should include and how to format them.

Statistical treatment of data is essential for all researchers, regardless of whether you’re a biologist, computer scientist or psychologist, but what exactly is it?

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

There’s no doubt about it – writing can be difficult. Whether you’re writing the first sentence of a paper or a grant proposal, it’s easy

Stay up to date with current information being provided by the UK Government and Universities about the impact of the global pandemic on PhD research studies.

Dr Anwar gained her PhD in Biochemistry from the University of Helsinki in 2019. She is now pursuing a career within industry and becoming more active in science outreach.

Hannah is a 1st year PhD student at Cardiff Metropolitan University. The aim of her research is to clarify what strategies are the most effective in supporting young people with dyslexia.

Join Thousands of Students

Scope and Delimitations in Research

Delimitations are the boundaries that the researcher sets in a research study, deciding what to include and what to exclude. They help to narrow down the study and make it more manageable and relevant to the research goal.

Updated on October 19, 2022

All scientific research has boundaries, whether or not the authors clearly explain them. Your study's scope and delimitations are the sections where you define the broader parameters and boundaries of your research.

The scope details what your study will explore, such as the target population, extent, or study duration. Delimitations are factors and variables not included in the study.

Scope and delimitations are not methodological shortcomings; they're always under your control. Discussing these is essential because doing so shows that your project is manageable and scientifically sound.

This article covers:

- What's meant by “scope” and “delimitations”

- Why these are integral components of every study

- How and where to actually write about scope and delimitations in your manuscript

- Examples of scope and delimitations from published studies

What is the scope in a research paper?

Simply put, the scope is the domain of your research. It describes the extent to which the research question will be explored in your study.

Articulating your study's scope early on helps you make your research question focused and realistic.

It also helps decide what data you need to collect (and, therefore, what data collection tools you need to design). Getting this right is vital for both academic articles and funding applications.

What are delimitations in a research paper?

Delimitations are those factors or aspects of the research area that you'll exclude from your research. The scope and delimitations of the study are intimately linked.

Essentially, delimitations form a more detailed and narrowed-down formulation of the scope in terms of exclusion. The delimitations explain what was (intentionally) not considered within the given piece of research.

Scope and delimitations examples

Use the following examples provided by our expert PhD editors as a reference when coming up with your own scope and delimitations.

Scope example

Your research question is, “What is the impact of bullying on the mental health of adolescents?” This topic, on its own, doesn't say much about what's being investigated.

The scope, for example, could encompass:

- Variables: “bullying” (dependent variable), “mental health” (independent variable), and ways of defining or measuring them

- Bullying type: Both face-to-face and cyberbullying

- Target population: Adolescents aged 12–17

- Geographical coverage: France or only one specific town in France

Delimitations example

Look back at the previous example.

Exploring the adverse effects of bullying on adolescents' mental health is a preliminary delimitation. This one was chosen from among many possible research questions (e.g., the impact of bullying on suicide rates, or children or adults).

Delimiting factors could include:

- Research design : Mixed-methods research, including thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and statistical analysis of a survey

- Timeframe : Data collection to run for 3 months

- Population size : 100 survey participants; 15 interviewees

- Recruitment of participants : Quota sampling (aiming for specific portions of men, women, ethnic minority students etc.)

We can see that every choice you make in planning and conducting your research inevitably excludes other possible options.

What's the difference between limitations and delimitations?

Delimitations and limitations are entirely different, although they often get mixed up. These are the main differences:

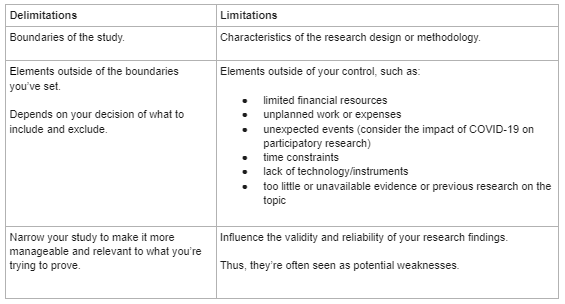

This chart explains the difference between delimitations and limitations. Delimitations are the boundaries of the study while the limitations are the characteristics of the research design or methodology.

Delimitations encompass the elements outside of the boundaries you've set and depends on your decision of what yo include and exclude. On the flip side, limitations are the elements outside of your control, such as:

- limited financial resources

- unplanned work or expenses

- unexpected events (for example, the COVID-19 pandemic)

- time constraints

- lack of technology/instruments

- unavailable evidence or previous research on the topic

Delimitations involve narrowing your study to make it more manageable and relevant to what you're trying to prove. Limitations influence the validity and reliability of your research findings. Limitations are seen as potential weaknesses in your research.

Example of the differences

To clarify these differences, go back to the limitations of the earlier example.

Limitations could comprise:

- Sample size : Not large enough to provide generalizable conclusions.

- Sampling approach : Non-probability sampling has increased bias risk. For instance, the researchers might not manage to capture the experiences of ethnic minority students.

- Methodological pitfalls : Research participants from an urban area (Paris) are likely to be more advantaged than students in rural areas. A study exploring the latter's experiences will probably yield very different findings.

Where do you write the scope and delimitations, and why?

It can be surprisingly empowering to realize you're restricted when conducting scholarly research. But this realization also makes writing up your research easier to grasp and makes it easier to see its limits and the expectations placed on it. Properly revealing this information serves your field and the greater scientific community.

Openly (but briefly) acknowledge the scope and delimitations of your study early on. The Abstract and Introduction sections are good places to set the parameters of your paper.

Next, discuss the scope and delimitations in greater detail in the Methods section. You'll need to do this to justify your methodological approach and data collection instruments, as well as analyses

At this point, spell out why these delimitations were set. What alternative options did you consider? Why did you reject alternatives? What could your study not address?

Let's say you're gathering data that can be derived from different but related experiments. You must convince the reader that the one you selected best suits your research question.

Finally, a solid paper will return to the scope and delimitations in the Findings or Discussion section. Doing so helps readers contextualize and interpret findings because the study's scope and methods influence the results.

For instance, agricultural field experiments carried out under irrigated conditions yield different results from experiments carried out without irrigation.

Being transparent about the scope and any outstanding issues increases your research's credibility and objectivity. It helps other researchers replicate your study and advance scientific understanding of the same topic (e.g., by adopting a different approach).

How do you write the scope and delimitations?

Define the scope and delimitations of your study before collecting data. This is critical. This step should be part of your research project planning.

Answering the following questions will help you address your scope and delimitations clearly and convincingly.

- What are your study's aims and objectives?

- Why did you carry out the study?

- What was the exact topic under investigation?

- Which factors and variables were included? And state why specific variables were omitted from the research scope.

- Who or what did the study explore? What was the target population?

- What was the study's location (geographical area) or setting (e.g., laboratory)?

- What was the timeframe within which you collected your data ?

- Consider a study exploring the differences between identical twins who were raised together versus identical twins who weren't. The data collection might span 5, 10, or more years.

- A study exploring a new immigration policy will cover the period since the policy came into effect and the present moment.

- How was the research conducted (research design)?

- Experimental research, qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods research, literature review, etc.

- What data collection tools and analysis techniques were used? e.g., If you chose quantitative methods, which statistical analysis techniques and software did you use?

- What did you find?

- What did you conclude?

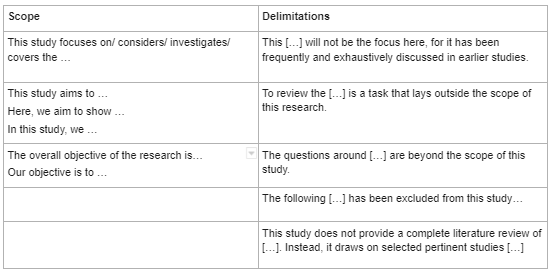

Useful vocabulary for scope and delimitations

When explaining both the scope and delimitations, it's important to use the proper language to clearly state each.

For the scope , use the following language:

- This study focuses on/considers/investigates/covers the following:

- This study aims to . . . / Here, we aim to show . . . / In this study, we . . .

- The overall objective of the research is . . . / Our objective is to . . .

When stating the delimitations, use the following language:

- This [ . . . ] will not be the focus, for it has been frequently and exhaustively discusses in earlier studies.

- To review the [ . . . ] is a task that lies outside the scope of this study.

- The following [ . . . ] has been excluded from this study . . .

- This study does not provide a complete literature review of [ . . . ]. Instead, it draws on selected pertinent studies [ . . . ]

Analysis of a published scope

In one example, Simione and Gnagnarella (2020) compared the psychological and behavioral impact of COVID-19 on Italy's health workers and general population.

Here's a breakdown of the study's scope into smaller chunks and discussion of what works and why.

Also notable is that this study's delimitations include references to:

- Recruitment of participants: Convenience sampling

- Demographic characteristics of study participants: Age, sex, etc.

- Measurements methods: E.g., the death anxiety scale of the Existential Concerns Questionnaire (ECQ; van Bruggen et al., 2017) etc.

- Data analysis tool: The statistical software R

Analysis of published scope and delimitations

Scope of the study : Johnsson et al. (2019) explored the effect of in-hospital physiotherapy on postoperative physical capacity, physical activity, and lung function in patients who underwent lung cancer surgery.

The delimitations narrowed down the scope as follows:

Refine your scope, delimitations, and scientific English

English ability shouldn't limit how clear and impactful your research can be. Expert AJE editors are available to assess your science and polish your academic writing. See AJE services here .

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Setting Limits and Focusing Your Study: Exploring scope and delimitation

As a researcher, it can be easy to get lost in the vast expanse of information and data available. Thus, when starting a research project, one of the most important things to consider is the scope and delimitation of the study. Setting limits and focusing your study is essential to ensure that the research project is manageable, relevant, and able to produce useful results. In this article, we will explore the importance of setting limits and focusing your study through an in-depth analysis of scope and delimitation.

Company Name 123

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, cu usu cibo vituperata, id ius probo maiestatis inciderint, sit eu vide volutpat.

Sign Up for More Insights

Table of Contents

Scope and Delimitation – Definition and difference

Scope refers to the range of the research project and the study limitations set in place to define the boundaries of the project and delimitation refers to the specific aspects of the research project that the study will focus on.

In simpler words, scope is the breadth of your study, while delimitation is the depth of your study.

Scope and delimitation are both essential components of a research project, and they are often confused with one another. The scope defines the parameters of the study, while delimitation sets the boundaries within those parameters. The scope and delimitation of a study are usually established early on in the research process and guide the rest of the project.

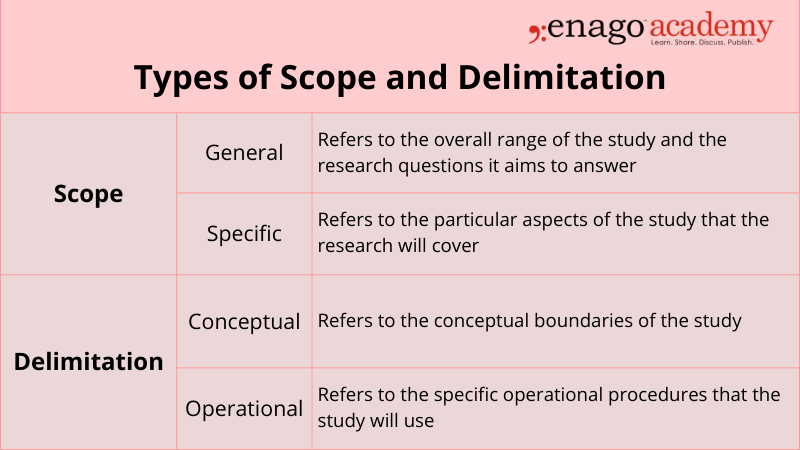

Types of Scope and Delimitation

Significance of Scope and Delimitation

Setting limits and focusing your study through scope and delimitation is crucial for the following reasons:

- It allows researchers to define the research project’s boundaries, enabling them to focus on specific aspects of the project. This focus makes it easier to gather relevant data and avoid unnecessary information that might complicate the study’s results.

- Setting limits and focusing your study through scope and delimitation enables the researcher to stay within the parameters of the project’s resources.

- A well-defined scope and delimitation ensure that the research project can be completed within the available resources, such as time and budget, while still achieving the project’s objectives.

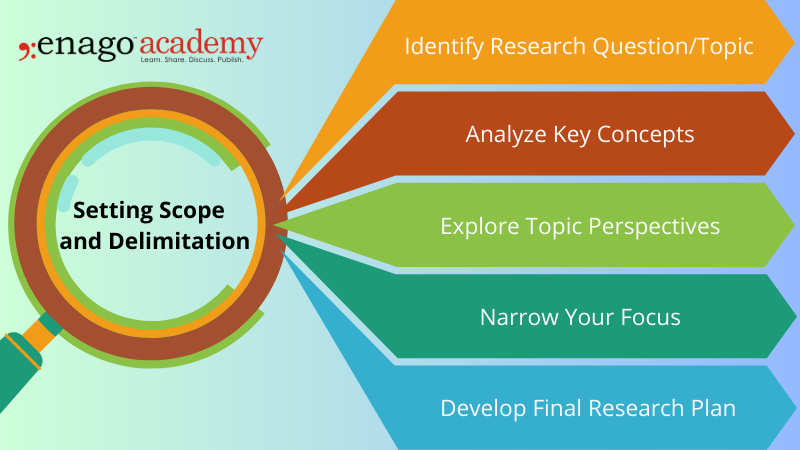

5 Steps to Setting Limits and Defining the Scope and Delimitation of Your Study

There are a few steps that you can take to set limits and focus your study.

1. Identify your research question or topic

The first step is to identify what you are interested in learning about. The research question should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Once you have a research question or topic, you can start to narrow your focus.

2. Consider the key terms or concepts related to your topic

What are the important terms or concepts that you need to understand in order to answer your research question? Consider all available resources, such as time, budget, and data availability, when setting scope and delimitation.

The scope and delimitation should be established within the parameters of the available resources. Once you have identified the key terms or concepts, you can start to develop a glossary or list of definitions.

3. Consider the different perspectives on your topic

There are often different perspectives on any given topic. Get feedback on the proposed scope and delimitation. Advisors can provide guidance on the feasibility of the study and offer suggestions for improvement.

It is important to consider all of the different perspectives in order to get a well-rounded understanding of your topic.

4. Narrow your focus

Be specific and concise when setting scope and delimitation. The parameters of the study should be clearly defined to avoid ambiguity and ensure that the study is focused on relevant aspects of the research question.

This means deciding which aspects of your topic you will focus on and which aspects you will eliminate.

5. Develop the final research plan

Revisit and revise the scope and delimitation as needed. As the research project progresses, the scope and delimitation may need to be adjusted to ensure that the study remains focused on the research question and can produce useful results. This plan should include your research goals, methods, and timeline.

Examples of Scope and Delimitation

To better understand scope and delimitation, let us consider two examples of research questions and how scope and delimitation would apply to them.

Research question: What are the effects of social media on mental health?

Scope: The scope of the study will focus on the impact of social media on the mental health of young adults aged 18-24 in the United States.

Delimitation: The study will specifically examine the following aspects of social media: frequency of use, types of social media platforms used, and the impact of social media on self-esteem and body image.

Research question: What are the factors that influence employee job satisfaction in the healthcare industry?

Scope: The scope of the study will focus on employee job satisfaction in the healthcare industry in the United States.

Delimitation: The study will specifically examine the following factors that influence employee job satisfaction: salary, work-life balance, job security, and opportunities for career growth.

Setting limits and defining the scope and delimitation of a research study is essential to conducting effective research. By doing so, researchers can ensure that their study is focused, manageable, and feasible within the given time frame and resources. It can also help to identify areas that require further study, providing a foundation for future research.

So, the next time you embark on a research project, don’t forget to set clear limits and define the scope and delimitation of your study. It may seem like a tedious task, but it can ultimately lead to more meaningful and impactful research. And if you still can’t find a solution, reach out to Enago Academy using #AskEnago and tag @EnagoAcademy on Twitter , Facebook , and Quora .

Frequently Asked Questions

The scope in research refers to the boundaries and extent of a study, defining its specific objectives, target population, variables, methods, and limitations, which helps researchers focus and provide a clear understanding of what will be investigated.

Delimitation in research defines the specific boundaries and limitations of a study, such as geographical, temporal, or conceptual constraints, outlining what will be excluded or not within the scope of investigation, providing clarity and ensuring the study remains focused and manageable.

To write a scope; 1. Clearly define research objectives. 2. Identify specific research questions. 3. Determine the target population for the study. 4. Outline the variables to be investigated. 5. Establish limitations and constraints. 6. Set boundaries and extent of the investigation. 7. Ensure focus, clarity, and manageability. 8. Provide context for the research project.

To write delimitations; 1. Identify geographical boundaries or constraints. 2. Define the specific time period or timeframe of the study. 3. Specify the sample size or selection criteria. 4. Clarify any demographic limitations (e.g., age, gender, occupation). 5. Address any limitations related to data collection methods. 6. Consider limitations regarding the availability of resources or data. 7. Exclude specific variables or factors from the scope of the study. 8. Clearly state any conceptual boundaries or theoretical frameworks. 9. Acknowledge any potential biases or constraints in the research design. 10. Ensure that the delimitations provide a clear focus and scope for the study.

What is an example of delimitation of the study?

Thank you 💕

Thank You very simplified🩷

Thanks, I find this article very helpful

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![scope of the study in research methodology What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Research Manuscripts Using AI-Powered Insights: Enago reports for effective research communication

Language Quality Importance in Academia AI in Evaluating Language Quality Enago Language Reports Live Demo…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What would be most effective in reducing research misconduct?

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Decoding the Scope and Delimitations of the Study in Research

Scope and delimitations of the study are two essential elements of a research paper or thesis that help to contextualize and convey the focus and boundaries of a research study. This allows readers to understand the research focus and the kind of information to expect. For researchers, especially students and early career researchers, understanding the meaning and purpose of the scope and delimitation of a study is crucial to craft a well-defined and impactful research project. In this article, we delve into the core concepts of scope and delimitation in a study, providing insightful examples, and practical tips on how to effectively incorporate them into your research endeavors.

Table of Contents

What is scope and delimitation in research

The scope of a research paper explains the context and framework for the study, outlines the extent, variables, or dimensions that will be investigated, and provides details of the parameters within which the study is conducted. Delimitations in research , on the other hand, refer to the limitations imposed on the study. It identifies aspects of the topic that will not be covered in the research, conveys why these choices were made, and how this will affect the outcome of the research. By narrowing down the scope and defining delimitations, researchers can ensure focused research and avoid pitfalls, which ensures the study remains feasible and attainable.

Example of scope and delimitation of a study

A researcher might want to study the effects of regular physical exercise on the health of senior citizens. This would be the broad scope of the study, after which the researcher would refine the scope by excluding specific groups of senior citizens, perhaps based on their age, gender, geographical location, cultural influences, and sample sizes. These then, would form the delimitations of the study; in other words, elements that describe the boundaries of the research.

The purpose of scope and delimitation in a study

The purpose of scope and delimitation in a study is to establish clear boundaries and focus for the research. This allows researchers to avoid ambiguity, set achievable objectives, and manage their project efficiently, ultimately leading to more credible and meaningful findings in their study. The scope and delimitation of a study serve several important purposes, including:

- Establishing clarity: Clearly defining the scope and delimitation of a study helps researchers and readers alike understand the boundaries of the investigation and what to expect from it.

- Focus and relevance: By setting the scope, researchers can concentrate on specific research questions, preventing the study from becoming too broad or irrelevant.

- Feasibility: Delimitations of the study prevent researchers from taking on too unrealistic or unmanageable tasks, making the research more achievable.

- Avoiding ambiguity: A well-defined scope and delimitation of the study minimizes any confusion or misinterpretation regarding the research objectives and methods.

Given the importance of both the scope and delimitations of a study, it is imperative to ensure that they are mentioned early on in the research manuscript. Most experts agree that the scope of research should be mentioned as part of the introduction and the delimitations must be mentioned as part of the methods section. Now that we’ve covered the scope and delimitation meaning and purpose, we look at how to write each of these sections.

How to write the scope of the study in research

When writing the scope of the study, remain focused on what you hope to achieve. Broadening the scope too much might make it too generic while narrowing it down too much may affect the way it would be interpreted. Ensure the scope of the study is clear, concise and accurate. Conduct a thorough literature review to understand existing literature, which will help identify gaps and refine the scope of your study.

It is helpful if you structure the scope in a way that answers the Six Ws – questions whose answers are considered basic in information-gathering.

Why: State the purpose of the research by articulating the research objectives and questions you aim to address in your study.

What: Outline the specific topic to be studied, while mentioning the variables, concepts, or aspects central to your research; these will define the extent of your study.

Where: Provide the setting or geographical location where the research study will be conducted.

When : Mention the specific timeframe within which the research data will be collected.

Who : Specify the sample size for the study and the profile of the population they will be drawn from.

How : Explain the research methodology, research design, and tools and analysis techniques.

How to write the delimitations of a study in research

When writing the delimitations of the study, researchers must provide all the details clearly and precisely. Writing the delimitations of the study requires a systematic approach to narrow down the research’s focus and establish boundaries. Follow these steps to craft delimitations effectively:

- Clearly understand the research objectives and questions you intend to address in your study.

- Conduct a comprehensive literature review to identify gaps and areas that have already been extensively covered. This helps to avoid redundancies and home in on a unique issue.

- Clearly state what aspects, variables, or factors you will be excluding in your research; mention available alternatives, if any, and why these alternatives were rejected.

- Explain how you the delimitations were set, and they contribute to the feasibility and relevance of your study, and how they align with the research objectives.

- Be sure to acknowledge limitations in your research, such as constraints related to time, resources, or data availability.

Being transparent ensures credibility, while explaining why the delimitations of your study could not be overcome with standard research methods backed up by scientific evidence can help readers understand the context better.

Differentiating between delimitations and limitations

Most early career researchers get confused and often use these two terms interchangeably which is wrong. Delimitations of a study refer to the set boundaries and specific parameters within which the research is carried out. They help narrow down your focus and makes it more relevant to what you are trying to prove.

Meanwhile, limitations in a study refer to the validity and reliability of the research being conducted. They are those elements of your study that are usually out of your immediate control but are still able to affect your findings in some way. In other words, limitation are potential weaknesses of your research.

In conclusion, scope and delimitation of a study are vital elements that shape the trajectory of your research study. The above explanations will have hopefully helped you better understand the scope and delimitations meaning, purpose, and importance in crafting focused, feasible, and impactful research studies. Be sure to follow the simple techniques to write the scope and delimitations of the study to embark on your research journey with clarity and confidence. Happy researching!

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Researcher.Life All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 21+ years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $17 a month !

Related Posts

Thesis Defense: How to Ace this Crucial Step

What is Independent Publishing in Academia?

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Here's What You Need to Understand About Research Methodology

Table of Contents

Research methodology involves a systematic and well-structured approach to conducting scholarly or scientific inquiries. Knowing the significance of research methodology and its different components is crucial as it serves as the basis for any study.

Typically, your research topic will start as a broad idea you want to investigate more thoroughly. Once you’ve identified a research problem and created research questions , you must choose the appropriate methodology and frameworks to address those questions effectively.

What is the definition of a research methodology?

Research methodology is the process or the way you intend to execute your study. The methodology section of a research paper outlines how you plan to conduct your study. It covers various steps such as collecting data, statistical analysis, observing participants, and other procedures involved in the research process

The methods section should give a description of the process that will convert your idea into a study. Additionally, the outcomes of your process must provide valid and reliable results resonant with the aims and objectives of your research. This thumb rule holds complete validity, no matter whether your paper has inclinations for qualitative or quantitative usage.

Studying research methods used in related studies can provide helpful insights and direction for your own research. Now easily discover papers related to your topic on SciSpace and utilize our AI research assistant, Copilot , to quickly review the methodologies applied in different papers.

The need for a good research methodology

While deciding on your approach towards your research, the reason or factors you weighed in choosing a particular problem and formulating a research topic need to be validated and explained. A research methodology helps you do exactly that. Moreover, a good research methodology lets you build your argument to validate your research work performed through various data collection methods, analytical methods, and other essential points.

Just imagine it as a strategy documented to provide an overview of what you intend to do.

While undertaking any research writing or performing the research itself, you may get drifted in not something of much importance. In such a case, a research methodology helps you to get back to your outlined work methodology.

A research methodology helps in keeping you accountable for your work. Additionally, it can help you evaluate whether your work is in sync with your original aims and objectives or not. Besides, a good research methodology enables you to navigate your research process smoothly and swiftly while providing effective planning to achieve your desired results.

What is the basic structure of a research methodology?

Usually, you must ensure to include the following stated aspects while deciding over the basic structure of your research methodology:

1. Your research procedure

Explain what research methods you’re going to use. Whether you intend to proceed with quantitative or qualitative, or a composite of both approaches, you need to state that explicitly. The option among the three depends on your research’s aim, objectives, and scope.

2. Provide the rationality behind your chosen approach

Based on logic and reason, let your readers know why you have chosen said research methodologies. Additionally, you have to build strong arguments supporting why your chosen research method is the best way to achieve the desired outcome.

3. Explain your mechanism

The mechanism encompasses the research methods or instruments you will use to develop your research methodology. It usually refers to your data collection methods. You can use interviews, surveys, physical questionnaires, etc., of the many available mechanisms as research methodology instruments. The data collection method is determined by the type of research and whether the data is quantitative data(includes numerical data) or qualitative data (perception, morale, etc.) Moreover, you need to put logical reasoning behind choosing a particular instrument.

4. Significance of outcomes

The results will be available once you have finished experimenting. However, you should also explain how you plan to use the data to interpret the findings. This section also aids in understanding the problem from within, breaking it down into pieces, and viewing the research problem from various perspectives.

5. Reader’s advice

Anything that you feel must be explained to spread more awareness among readers and focus groups must be included and described in detail. You should not just specify your research methodology on the assumption that a reader is aware of the topic.

All the relevant information that explains and simplifies your research paper must be included in the methodology section. If you are conducting your research in a non-traditional manner, give a logical justification and list its benefits.

6. Explain your sample space

Include information about the sample and sample space in the methodology section. The term "sample" refers to a smaller set of data that a researcher selects or chooses from a larger group of people or focus groups using a predetermined selection method. Let your readers know how you are going to distinguish between relevant and non-relevant samples. How you figured out those exact numbers to back your research methodology, i.e. the sample spacing of instruments, must be discussed thoroughly.

For example, if you are going to conduct a survey or interview, then by what procedure will you select the interviewees (or sample size in case of surveys), and how exactly will the interview or survey be conducted.

7. Challenges and limitations

This part, which is frequently assumed to be unnecessary, is actually very important. The challenges and limitations that your chosen strategy inherently possesses must be specified while you are conducting different types of research.

The importance of a good research methodology

You must have observed that all research papers, dissertations, or theses carry a chapter entirely dedicated to research methodology. This section helps maintain your credibility as a better interpreter of results rather than a manipulator.

A good research methodology always explains the procedure, data collection methods and techniques, aim, and scope of the research. In a research study, it leads to a well-organized, rationality-based approach, while the paper lacking it is often observed as messy or disorganized.

You should pay special attention to validating your chosen way towards the research methodology. This becomes extremely important in case you select an unconventional or a distinct method of execution.

Curating and developing a strong, effective research methodology can assist you in addressing a variety of situations, such as:

- When someone tries to duplicate or expand upon your research after few years.

- If a contradiction or conflict of facts occurs at a later time. This gives you the security you need to deal with these contradictions while still being able to defend your approach.

- Gaining a tactical approach in getting your research completed in time. Just ensure you are using the right approach while drafting your research methodology, and it can help you achieve your desired outcomes. Additionally, it provides a better explanation and understanding of the research question itself.

- Documenting the results so that the final outcome of the research stays as you intended it to be while starting.

Instruments you could use while writing a good research methodology

As a researcher, you must choose which tools or data collection methods that fit best in terms of the relevance of your research. This decision has to be wise.

There exists many research equipments or tools that you can use to carry out your research process. These are classified as:

a. Interviews (One-on-One or a Group)

An interview aimed to get your desired research outcomes can be undertaken in many different ways. For example, you can design your interview as structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. What sets them apart is the degree of formality in the questions. On the other hand, in a group interview, your aim should be to collect more opinions and group perceptions from the focus groups on a certain topic rather than looking out for some formal answers.

In surveys, you are in better control if you specifically draft the questions you seek the response for. For example, you may choose to include free-style questions that can be answered descriptively, or you may provide a multiple-choice type response for questions. Besides, you can also opt to choose both ways, deciding what suits your research process and purpose better.

c. Sample Groups

Similar to the group interviews, here, you can select a group of individuals and assign them a topic to discuss or freely express their opinions over that. You can simultaneously note down the answers and later draft them appropriately, deciding on the relevance of every response.

d. Observations

If your research domain is humanities or sociology, observations are the best-proven method to draw your research methodology. Of course, you can always include studying the spontaneous response of the participants towards a situation or conducting the same but in a more structured manner. A structured observation means putting the participants in a situation at a previously decided time and then studying their responses.

Of all the tools described above, it is you who should wisely choose the instruments and decide what’s the best fit for your research. You must not restrict yourself from multiple methods or a combination of a few instruments if appropriate in drafting a good research methodology.

Types of research methodology

A research methodology exists in various forms. Depending upon their approach, whether centered around words, numbers, or both, methodologies are distinguished as qualitative, quantitative, or an amalgamation of both.

1. Qualitative research methodology

When a research methodology primarily focuses on words and textual data, then it is generally referred to as qualitative research methodology. This type is usually preferred among researchers when the aim and scope of the research are mainly theoretical and explanatory.

The instruments used are observations, interviews, and sample groups. You can use this methodology if you are trying to study human behavior or response in some situations. Generally, qualitative research methodology is widely used in sociology, psychology, and other related domains.

2. Quantitative research methodology

If your research is majorly centered on data, figures, and stats, then analyzing these numerical data is often referred to as quantitative research methodology. You can use quantitative research methodology if your research requires you to validate or justify the obtained results.

In quantitative methods, surveys, tests, experiments, and evaluations of current databases can be advantageously used as instruments If your research involves testing some hypothesis, then use this methodology.

3. Amalgam methodology

As the name suggests, the amalgam methodology uses both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This methodology is used when a part of the research requires you to verify the facts and figures, whereas the other part demands you to discover the theoretical and explanatory nature of the research question.

The instruments for the amalgam methodology require you to conduct interviews and surveys, including tests and experiments. The outcome of this methodology can be insightful and valuable as it provides precise test results in line with theoretical explanations and reasoning.

The amalgam method, makes your work both factual and rational at the same time.

Final words: How to decide which is the best research methodology?

If you have kept your sincerity and awareness intact with the aims and scope of research well enough, you must have got an idea of which research methodology suits your work best.

Before deciding which research methodology answers your research question, you must invest significant time in reading and doing your homework for that. Taking references that yield relevant results should be your first approach to establishing a research methodology.

Moreover, you should never refrain from exploring other options. Before setting your work in stone, you must try all the available options as it explains why the choice of research methodology that you finally make is more appropriate than the other available options.

You should always go for a quantitative research methodology if your research requires gathering large amounts of data, figures, and statistics. This research methodology will provide you with results if your research paper involves the validation of some hypothesis.

Whereas, if you are looking for more explanations, reasons, opinions, and public perceptions around a theory, you must use qualitative research methodology.The choice of an appropriate research methodology ultimately depends on what you want to achieve through your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Research Methodology

1. how to write a research methodology.

You can always provide a separate section for research methodology where you should specify details about the methods and instruments used during the research, discussions on result analysis, including insights into the background information, and conveying the research limitations.

2. What are the types of research methodology?

There generally exists four types of research methodology i.e.

- Observation

- Experimental

- Derivational

3. What is the true meaning of research methodology?

The set of techniques or procedures followed to discover and analyze the information gathered to validate or justify a research outcome is generally called Research Methodology.

4. Where lies the importance of research methodology?

Your research methodology directly reflects the validity of your research outcomes and how well-informed your research work is. Moreover, it can help future researchers cite or refer to your research if they plan to use a similar research methodology.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Using AI for research: A beginner’s guide

Academic Research in Education

- How to Find Books, Articles and eBooks

- Books, eBooks, & Multimedia

- Evaluating Information

- Deciding on a Topic

- Creating a Thesis Statement

- The Literature Review

- Scope of Research

Defining the Scope of your Project

What is scope.

- Choosing a Design

- Citing Sources & Avoiding Plagiarism

- Contact Library

Post-Grad Collective [PGC]. (2017, February 13). Thesis Writing-Narrow the Scope [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IlCO5yRB9No&feature=youtu.be

Learn to cite a YouTube Video!

The scope of your project sets clear parameters for your research.

A scope statement will give basic information about the depth and breadth of the project. It tells your reader exactly what you want to find out , how you will conduct your study, the reports and deliverables that will be part of the outcome of the study, and the responsibilities of the researchers involved in the study. The extent of the scope will be a part of acknowledging any biases in the research project.

Defining the scope of a project:

- focuses your research goals

- clarifies the expectations for your research project

- helps you determine potential biases in your research methodology by acknowledging the limits of your research study

- identifies the limitations of your research

- << Previous: The Literature Review

- Next: Choosing a Design >>

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 9:06 AM

- URL: https://moc.libguides.com/aca_res_edu

Faculty & Staff Directory

Event Calendar

News Archives

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

Public Relations

634 Henderson St.

Mount Olive, NC 28365

1-800-653-0854

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2020

A tutorial on methodological studies: the what, when, how and why

- Lawrence Mbuagbaw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5855-5461 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Daeria O. Lawson 1 ,

- Livia Puljak 4 ,

- David B. Allison 5 &

- Lehana Thabane 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 20 , Article number: 226 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

54 Citations

60 Altmetric

Metrics details

Methodological studies – studies that evaluate the design, analysis or reporting of other research-related reports – play an important role in health research. They help to highlight issues in the conduct of research with the aim of improving health research methodology, and ultimately reducing research waste.

We provide an overview of some of the key aspects of methodological studies such as what they are, and when, how and why they are done. We adopt a “frequently asked questions” format to facilitate reading this paper and provide multiple examples to help guide researchers interested in conducting methodological studies. Some of the topics addressed include: is it necessary to publish a study protocol? How to select relevant research reports and databases for a methodological study? What approaches to data extraction and statistical analysis should be considered when conducting a methodological study? What are potential threats to validity and is there a way to appraise the quality of methodological studies?

Appropriate reflection and application of basic principles of epidemiology and biostatistics are required in the design and analysis of methodological studies. This paper provides an introduction for further discussion about the conduct of methodological studies.

Peer Review reports

The field of meta-research (or research-on-research) has proliferated in recent years in response to issues with research quality and conduct [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. As the name suggests, this field targets issues with research design, conduct, analysis and reporting. Various types of research reports are often examined as the unit of analysis in these studies (e.g. abstracts, full manuscripts, trial registry entries). Like many other novel fields of research, meta-research has seen a proliferation of use before the development of reporting guidance. For example, this was the case with randomized trials for which risk of bias tools and reporting guidelines were only developed much later – after many trials had been published and noted to have limitations [ 4 , 5 ]; and for systematic reviews as well [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. However, in the absence of formal guidance, studies that report on research differ substantially in how they are named, conducted and reported [ 9 , 10 ]. This creates challenges in identifying, summarizing and comparing them. In this tutorial paper, we will use the term methodological study to refer to any study that reports on the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of primary or secondary research-related reports (such as trial registry entries and conference abstracts).

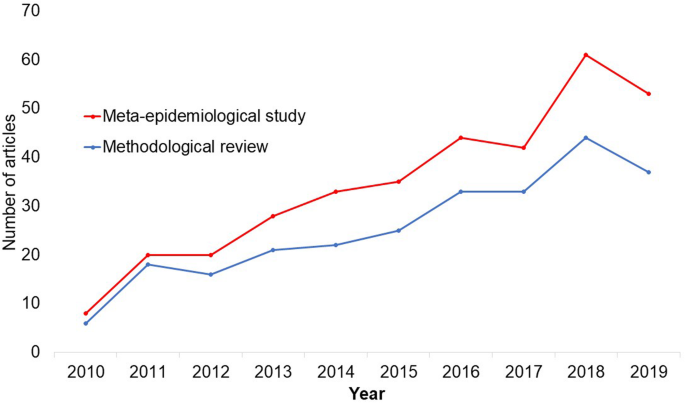

In the past 10 years, there has been an increase in the use of terms related to methodological studies (based on records retrieved with a keyword search [in the title and abstract] for “methodological review” and “meta-epidemiological study” in PubMed up to December 2019), suggesting that these studies may be appearing more frequently in the literature. See Fig. 1 .

Trends in the number studies that mention “methodological review” or “meta-

epidemiological study” in PubMed.

The methods used in many methodological studies have been borrowed from systematic and scoping reviews. This practice has influenced the direction of the field, with many methodological studies including searches of electronic databases, screening of records, duplicate data extraction and assessments of risk of bias in the included studies. However, the research questions posed in methodological studies do not always require the approaches listed above, and guidance is needed on when and how to apply these methods to a methodological study. Even though methodological studies can be conducted on qualitative or mixed methods research, this paper focuses on and draws examples exclusively from quantitative research.

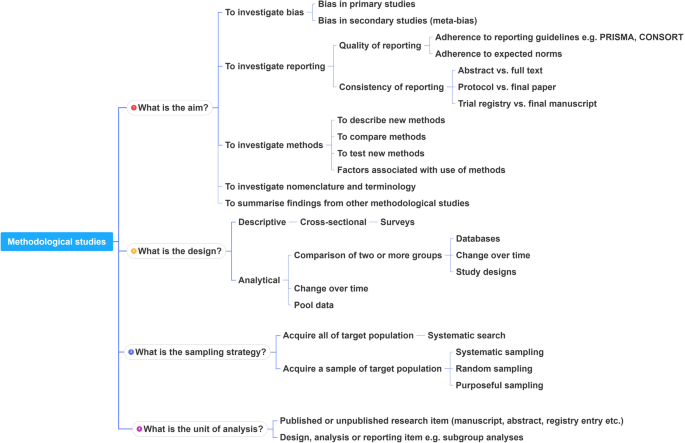

The objectives of this paper are to provide some insights on how to conduct methodological studies so that there is greater consistency between the research questions posed, and the design, analysis and reporting of findings. We provide multiple examples to illustrate concepts and a proposed framework for categorizing methodological studies in quantitative research.

What is a methodological study?

Any study that describes or analyzes methods (design, conduct, analysis or reporting) in published (or unpublished) literature is a methodological study. Consequently, the scope of methodological studies is quite extensive and includes, but is not limited to, topics as diverse as: research question formulation [ 11 ]; adherence to reporting guidelines [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] and consistency in reporting [ 15 ]; approaches to study analysis [ 16 ]; investigating the credibility of analyses [ 17 ]; and studies that synthesize these methodological studies [ 18 ]. While the nomenclature of methodological studies is not uniform, the intents and purposes of these studies remain fairly consistent – to describe or analyze methods in primary or secondary studies. As such, methodological studies may also be classified as a subtype of observational studies.

Parallel to this are experimental studies that compare different methods. Even though they play an important role in informing optimal research methods, experimental methodological studies are beyond the scope of this paper. Examples of such studies include the randomized trials by Buscemi et al., comparing single data extraction to double data extraction [ 19 ], and Carrasco-Labra et al., comparing approaches to presenting findings in Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) summary of findings tables [ 20 ]. In these studies, the unit of analysis is the person or groups of individuals applying the methods. We also direct readers to the Studies Within a Trial (SWAT) and Studies Within a Review (SWAR) programme operated through the Hub for Trials Methodology Research, for further reading as a potential useful resource for these types of experimental studies [ 21 ]. Lastly, this paper is not meant to inform the conduct of research using computational simulation and mathematical modeling for which some guidance already exists [ 22 ], or studies on the development of methods using consensus-based approaches.

When should we conduct a methodological study?

Methodological studies occupy a unique niche in health research that allows them to inform methodological advances. Methodological studies should also be conducted as pre-cursors to reporting guideline development, as they provide an opportunity to understand current practices, and help to identify the need for guidance and gaps in methodological or reporting quality. For example, the development of the popular Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were preceded by methodological studies identifying poor reporting practices [ 23 , 24 ]. In these instances, after the reporting guidelines are published, methodological studies can also be used to monitor uptake of the guidelines.

These studies can also be conducted to inform the state of the art for design, analysis and reporting practices across different types of health research fields, with the aim of improving research practices, and preventing or reducing research waste. For example, Samaan et al. conducted a scoping review of adherence to different reporting guidelines in health care literature [ 18 ]. Methodological studies can also be used to determine the factors associated with reporting practices. For example, Abbade et al. investigated journal characteristics associated with the use of the Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timeframe (PICOT) format in framing research questions in trials of venous ulcer disease [ 11 ].

How often are methodological studies conducted?

There is no clear answer to this question. Based on a search of PubMed, the use of related terms (“methodological review” and “meta-epidemiological study”) – and therefore, the number of methodological studies – is on the rise. However, many other terms are used to describe methodological studies. There are also many studies that explore design, conduct, analysis or reporting of research reports, but that do not use any specific terms to describe or label their study design in terms of “methodology”. This diversity in nomenclature makes a census of methodological studies elusive. Appropriate terminology and key words for methodological studies are needed to facilitate improved accessibility for end-users.

Why do we conduct methodological studies?

Methodological studies provide information on the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of primary and secondary research and can be used to appraise quality, quantity, completeness, accuracy and consistency of health research. These issues can be explored in specific fields, journals, databases, geographical regions and time periods. For example, Areia et al. explored the quality of reporting of endoscopic diagnostic studies in gastroenterology [ 25 ]; Knol et al. investigated the reporting of p -values in baseline tables in randomized trial published in high impact journals [ 26 ]; Chen et al. describe adherence to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement in Chinese Journals [ 27 ]; and Hopewell et al. describe the effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on reporting of abstracts over time [ 28 ]. Methodological studies provide useful information to researchers, clinicians, editors, publishers and users of health literature. As a result, these studies have been at the cornerstone of important methodological developments in the past two decades and have informed the development of many health research guidelines including the highly cited CONSORT statement [ 5 ].

Where can we find methodological studies?

Methodological studies can be found in most common biomedical bibliographic databases (e.g. Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, Web of Science). However, the biggest caveat is that methodological studies are hard to identify in the literature due to the wide variety of names used and the lack of comprehensive databases dedicated to them. A handful can be found in the Cochrane Library as “Cochrane Methodology Reviews”, but these studies only cover methodological issues related to systematic reviews. Previous attempts to catalogue all empirical studies of methods used in reviews were abandoned 10 years ago [ 29 ]. In other databases, a variety of search terms may be applied with different levels of sensitivity and specificity.

Some frequently asked questions about methodological studies

In this section, we have outlined responses to questions that might help inform the conduct of methodological studies.

Q: How should I select research reports for my methodological study?

A: Selection of research reports for a methodological study depends on the research question and eligibility criteria. Once a clear research question is set and the nature of literature one desires to review is known, one can then begin the selection process. Selection may begin with a broad search, especially if the eligibility criteria are not apparent. For example, a methodological study of Cochrane Reviews of HIV would not require a complex search as all eligible studies can easily be retrieved from the Cochrane Library after checking a few boxes [ 30 ]. On the other hand, a methodological study of subgroup analyses in trials of gastrointestinal oncology would require a search to find such trials, and further screening to identify trials that conducted a subgroup analysis [ 31 ].

The strategies used for identifying participants in observational studies can apply here. One may use a systematic search to identify all eligible studies. If the number of eligible studies is unmanageable, a random sample of articles can be expected to provide comparable results if it is sufficiently large [ 32 ]. For example, Wilson et al. used a random sample of trials from the Cochrane Stroke Group’s Trial Register to investigate completeness of reporting [ 33 ]. It is possible that a simple random sample would lead to underrepresentation of units (i.e. research reports) that are smaller in number. This is relevant if the investigators wish to compare multiple groups but have too few units in one group. In this case a stratified sample would help to create equal groups. For example, in a methodological study comparing Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews, Kahale et al. drew random samples from both groups [ 34 ]. Alternatively, systematic or purposeful sampling strategies can be used and we encourage researchers to justify their selected approaches based on the study objective.

Q: How many databases should I search?

A: The number of databases one should search would depend on the approach to sampling, which can include targeting the entire “population” of interest or a sample of that population. If you are interested in including the entire target population for your research question, or drawing a random or systematic sample from it, then a comprehensive and exhaustive search for relevant articles is required. In this case, we recommend using systematic approaches for searching electronic databases (i.e. at least 2 databases with a replicable and time stamped search strategy). The results of your search will constitute a sampling frame from which eligible studies can be drawn.

Alternatively, if your approach to sampling is purposeful, then we recommend targeting the database(s) or data sources (e.g. journals, registries) that include the information you need. For example, if you are conducting a methodological study of high impact journals in plastic surgery and they are all indexed in PubMed, you likely do not need to search any other databases. You may also have a comprehensive list of all journals of interest and can approach your search using the journal names in your database search (or by accessing the journal archives directly from the journal’s website). Even though one could also search journals’ web pages directly, using a database such as PubMed has multiple advantages, such as the use of filters, so the search can be narrowed down to a certain period, or study types of interest. Furthermore, individual journals’ web sites may have different search functionalities, which do not necessarily yield a consistent output.

Q: Should I publish a protocol for my methodological study?

A: A protocol is a description of intended research methods. Currently, only protocols for clinical trials require registration [ 35 ]. Protocols for systematic reviews are encouraged but no formal recommendation exists. The scientific community welcomes the publication of protocols because they help protect against selective outcome reporting, the use of post hoc methodologies to embellish results, and to help avoid duplication of efforts [ 36 ]. While the latter two risks exist in methodological research, the negative consequences may be substantially less than for clinical outcomes. In a sample of 31 methodological studies, 7 (22.6%) referenced a published protocol [ 9 ]. In the Cochrane Library, there are 15 protocols for methodological reviews (21 July 2020). This suggests that publishing protocols for methodological studies is not uncommon.

Authors can consider publishing their study protocol in a scholarly journal as a manuscript. Advantages of such publication include obtaining peer-review feedback about the planned study, and easy retrieval by searching databases such as PubMed. The disadvantages in trying to publish protocols includes delays associated with manuscript handling and peer review, as well as costs, as few journals publish study protocols, and those journals mostly charge article-processing fees [ 37 ]. Authors who would like to make their protocol publicly available without publishing it in scholarly journals, could deposit their study protocols in publicly available repositories, such as the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/ ).

Q: How to appraise the quality of a methodological study?

A: To date, there is no published tool for appraising the risk of bias in a methodological study, but in principle, a methodological study could be considered as a type of observational study. Therefore, during conduct or appraisal, care should be taken to avoid the biases common in observational studies [ 38 ]. These biases include selection bias, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of exposure or outcome. In other words, to generate a representative sample, a comprehensive reproducible search may be necessary to build a sampling frame. Additionally, random sampling may be necessary to ensure that all the included research reports have the same probability of being selected, and the screening and selection processes should be transparent and reproducible. To ensure that the groups compared are similar in all characteristics, matching, random sampling or stratified sampling can be used. Statistical adjustments for between-group differences can also be applied at the analysis stage. Finally, duplicate data extraction can reduce errors in assessment of exposures or outcomes.

Q: Should I justify a sample size?

A: In all instances where one is not using the target population (i.e. the group to which inferences from the research report are directed) [ 39 ], a sample size justification is good practice. The sample size justification may take the form of a description of what is expected to be achieved with the number of articles selected, or a formal sample size estimation that outlines the number of articles required to answer the research question with a certain precision and power. Sample size justifications in methodological studies are reasonable in the following instances:

Comparing two groups

Determining a proportion, mean or another quantifier

Determining factors associated with an outcome using regression-based analyses

For example, El Dib et al. computed a sample size requirement for a methodological study of diagnostic strategies in randomized trials, based on a confidence interval approach [ 40 ].

Q: What should I call my study?

A: Other terms which have been used to describe/label methodological studies include “ methodological review ”, “methodological survey” , “meta-epidemiological study” , “systematic review” , “systematic survey”, “meta-research”, “research-on-research” and many others. We recommend that the study nomenclature be clear, unambiguous, informative and allow for appropriate indexing. Methodological study nomenclature that should be avoided includes “ systematic review” – as this will likely be confused with a systematic review of a clinical question. “ Systematic survey” may also lead to confusion about whether the survey was systematic (i.e. using a preplanned methodology) or a survey using “ systematic” sampling (i.e. a sampling approach using specific intervals to determine who is selected) [ 32 ]. Any of the above meanings of the words “ systematic” may be true for methodological studies and could be potentially misleading. “ Meta-epidemiological study” is ideal for indexing, but not very informative as it describes an entire field. The term “ review ” may point towards an appraisal or “review” of the design, conduct, analysis or reporting (or methodological components) of the targeted research reports, yet it has also been used to describe narrative reviews [ 41 , 42 ]. The term “ survey ” is also in line with the approaches used in many methodological studies [ 9 ], and would be indicative of the sampling procedures of this study design. However, in the absence of guidelines on nomenclature, the term “ methodological study ” is broad enough to capture most of the scenarios of such studies.

Q: Should I account for clustering in my methodological study?

A: Data from methodological studies are often clustered. For example, articles coming from a specific source may have different reporting standards (e.g. the Cochrane Library). Articles within the same journal may be similar due to editorial practices and policies, reporting requirements and endorsement of guidelines. There is emerging evidence that these are real concerns that should be accounted for in analyses [ 43 ]. Some cluster variables are described in the section: “ What variables are relevant to methodological studies?”

A variety of modelling approaches can be used to account for correlated data, including the use of marginal, fixed or mixed effects regression models with appropriate computation of standard errors [ 44 ]. For example, Kosa et al. used generalized estimation equations to account for correlation of articles within journals [ 15 ]. Not accounting for clustering could lead to incorrect p -values, unduly narrow confidence intervals, and biased estimates [ 45 ].

Q: Should I extract data in duplicate?

A: Yes. Duplicate data extraction takes more time but results in less errors [ 19 ]. Data extraction errors in turn affect the effect estimate [ 46 ], and therefore should be mitigated. Duplicate data extraction should be considered in the absence of other approaches to minimize extraction errors. However, much like systematic reviews, this area will likely see rapid new advances with machine learning and natural language processing technologies to support researchers with screening and data extraction [ 47 , 48 ]. However, experience plays an important role in the quality of extracted data and inexperienced extractors should be paired with experienced extractors [ 46 , 49 ].

Q: Should I assess the risk of bias of research reports included in my methodological study?

A : Risk of bias is most useful in determining the certainty that can be placed in the effect measure from a study. In methodological studies, risk of bias may not serve the purpose of determining the trustworthiness of results, as effect measures are often not the primary goal of methodological studies. Determining risk of bias in methodological studies is likely a practice borrowed from systematic review methodology, but whose intrinsic value is not obvious in methodological studies. When it is part of the research question, investigators often focus on one aspect of risk of bias. For example, Speich investigated how blinding was reported in surgical trials [ 50 ], and Abraha et al., investigated the application of intention-to-treat analyses in systematic reviews and trials [ 51 ].

Q: What variables are relevant to methodological studies?

A: There is empirical evidence that certain variables may inform the findings in a methodological study. We outline some of these and provide a brief overview below:

Country: Countries and regions differ in their research cultures, and the resources available to conduct research. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that there may be differences in methodological features across countries. Methodological studies have reported loco-regional differences in reporting quality [ 52 , 53 ]. This may also be related to challenges non-English speakers face in publishing papers in English.

Authors’ expertise: The inclusion of authors with expertise in research methodology, biostatistics, and scientific writing is likely to influence the end-product. Oltean et al. found that among randomized trials in orthopaedic surgery, the use of analyses that accounted for clustering was more likely when specialists (e.g. statistician, epidemiologist or clinical trials methodologist) were included on the study team [ 54 ]. Fleming et al. found that including methodologists in the review team was associated with appropriate use of reporting guidelines [ 55 ].

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Some studies have found that funded studies report better [ 56 , 57 ], while others do not [ 53 , 58 ]. The presence of funding would indicate the availability of resources deployed to ensure optimal design, conduct, analysis and reporting. However, the source of funding may introduce conflicts of interest and warrant assessment. For example, Kaiser et al. investigated the effect of industry funding on obesity or nutrition randomized trials and found that reporting quality was similar [ 59 ]. Thomas et al. looked at reporting quality of long-term weight loss trials and found that industry funded studies were better [ 60 ]. Kan et al. examined the association between industry funding and “positive trials” (trials reporting a significant intervention effect) and found that industry funding was highly predictive of a positive trial [ 61 ]. This finding is similar to that of a recent Cochrane Methodology Review by Hansen et al. [ 62 ]

Journal characteristics: Certain journals’ characteristics may influence the study design, analysis or reporting. Characteristics such as journal endorsement of guidelines [ 63 , 64 ], and Journal Impact Factor (JIF) have been shown to be associated with reporting [ 63 , 65 , 66 , 67 ].

Study size (sample size/number of sites): Some studies have shown that reporting is better in larger studies [ 53 , 56 , 58 ].