Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

How to evaluate the effectiveness of performance management systems an overview of the literature and a proposed integrative model.

1. Introduction

2. theoretical concepts, 2.1. strategic human resource management (shrm) and performance management (pm), 2.2. effectiveness of performance management system (pms), 3. research method, 4. results and discussion, 4.1. dimensions, criteria, and measures to evaluate the effectiveness of performance management systems (pmss), 4.1.1. reaction, 4.1.2. learning, 4.1.3. transfer, 4.1.4. operational results, 4.1.5. financial results, 4.1.6. societal impact, 4.1.7. methods and procedures for measuring the dimensions of performance management system (pms) effectiveness, 4.2. integrative model of evaluating performance management system (pms) effectiveness, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Abbad, Gardênia da Silva, Luciana Mourão, Pedro P. Murce Meneses, Thais Zerbini, Jairo Eduardo Borges-Andrade, and Raquel Vilas-Boas. 2019. Medidas de avaliação em treinamento, desenvolvimento e educação: Ferramentas para gestão de pessoas . Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abdullah, Haslinda, and Karen G. Abraham. 2012. Perception on the performance appraisal system among Malaysian diplomatic officers. Social Sciences 7: 486–95. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Aguinis, Herman. 2013. Performance Management . Upper Saddle River: Pearson. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ahmed, Shamina. 1999. The emerging measure of effectiveness for human resource management: An exploratory study with performance appraisal. Journal of Management Development 18: 543–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Armstrong, Michel. 2015. Armstrong’s Handbook of Performance Management: An Evidence-Based Guide to Delivering High Performance , 2nd ed. London: Kogan Page Publishers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Awan, Sajid H., Nazia Habib, Chaudhry S. Akhtar, and Shaheryar Naveed. 2020. Effectiveness of Performance Management System for Employee Performance through Engagement. SAGE Open 10: 1–15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baird, Kevin. 2017. The effectiveness of strategic performance measurement systems. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 66: 3–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baird, Kevin, Sophia X. Su, and Nuraddeen Nuhu. 2022. The mediating role of fairness on the effectiveness of strategic performance measurement systems. Personnel Review 51: 1491–517. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Becker, Brian E., and Mark A. Huselid. 1998. High Performance Work Systems and Firm Performance: A Synthesis of Research and Managerial Implications. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 16: 53–101. [ Google Scholar ]

- Biulchi, Adão F., and Jadir Pauli. 2012. Avaliação de Desempenho no Serviço Público: A Experiência do Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social na Implantação da Gratificação de Avaliação de Desempenho do Seguro Social—GDASS. Revista de Administração IMED 2: 129–37. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boxall, Peter, and John Purcell. 2000. Strategic human resource management: Where have we come from and where should we be going? International Journal of Management Reviews 2: 183–203. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brown, Taylor C., Paula O’Kane, Bishakha Mazumdar, and Martin McCracken. 2019. Performance Management: A Scoping Review of the Literature and an Agenda for Future Research. Human Resource Development Review 18: 47–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Budd, John W. 2020. The psychologisation of employment relations, alternative models of the employment relationship, and the OB turn. Human Resource Management Journal 30: 73–83. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cappelli, Peter, and Martin J. Conyon. 2017. What do performance appraisals do? ILR Review 71: 88–116. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Colakoglu, Saba, David P. Lepak, and Yang Hong. 2006. Measuring HRM effectiveness: Considering multiple stakeholders in a global context. Human Resource Management Review 16: 209–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Culbertson, Satoris S., Jaime B. Henning, and Stephanie C. Payne. 2013. Performance appraisal satisfaction. Journal of Personnel Psychology 12: 89–195. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Den Hartog, Deanne N., Paul Boselie, and Jaap Paauwe. 2004. Performance management: A model and research agenda. Applied Psychology 53: 556–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- DeNisi, Angelo S., and Kevin R. Murphy. 2017. Performance Appraisal and Performance Management: 100 Years of Progress? Journal of Applied Psychology 102: 421–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeNisi, Angelo S., and Robert D. Pritchard. 2006. Performance Appraisal, Performance Management and Improving Individual Performance: A Motivational Framework. Management and Organization Review 2: 253–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dyer, Lee, and Todd Reeves. 1995. Human resource strategies and firm performance: What do we know and where do we need to go? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 6: 656–70. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Espejo, Márcia M. dos S. B., William S. Araújo, Natália Fernandes, and Fábio Domingues. 2021. A influência da avaliação de desempenho na rotatividade de pessoal de uma empresa concessionária de energia elétrica no centro-oeste. RMC-Revista Mineira de Contabilidade 22: 51–64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Garengo, Patrizia, Albert Sardi, and Sai S. Nudurupati. 2022. Human resource management (HRM) in the performance measurement and management (PMM) domain: A bibliometric review. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 71: 3056–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Godard, John. 2014. The psychologisation of employment relations? Human Resource Management Journal 24: 1–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Guest, David. E. 1987. Human Resource Management and Industrial Relations. Journal of Management Studies 24: 503–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Haines, Victor Y., III, and Sylvie St-Onge. 2012. Performance management effectiveness: Practices or context? The International Journal of Human Resource Management 23: 1158–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huselid, Mark A. 1995. The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance. Academy of Management Journal 38: 635–72. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ikramullah, Malik, Jan-Willem Van Prooijen, Mahmamad Z. Iqbal, and Faqir S. Ul-Hassan. 2016. Effectiveness of performance appraisal: Developing a conceptual framework using competing values approach. Personnel Review 45: 334–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Iqbal, Muhammad Z., Saeed Akbar, and Pawan Budhwar. 2015. Effectiveness of Performance Appraisal: An Integrated Framework. International Journal of Management Reviews 17: 510–33. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Iqbal, Muhammad Z., Saeed Akbar, Pawan Budhwar, and Syed Z. A. Shah. 2019. Effectiveness of performance appraisal: Evidence on the utilization criteria. Journal of Business Research 101: 285–99. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jackson, Susan E., and Randell S. Schuler. 1995. Understanding Human Resource Management in the Context of Organizations and their Environments. Annual Review of Psychology 46: 237–64. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Jackson, Susan E., Randell S. Schuler, and Kaifeng Jiang. 2014. An Aspirational Framework for Strategic Human Resource Management. The Academy of Management Annals 8: 1–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jiang, Kaifeng, and Pingshu Li. 2019. Models of strategic human resource management. In SAGE Handbook of Human Resource Management . Edited by Adrian Wilkinson, Nicolas Bacon, David Lepak and Scott Snell. London: Sage, pp. 23–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiang, Kaifeng, David P. Lepak, Jia Hu, and Judith C. Baer. 2012. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanism. Academy of Management Journal 55: 1264–94. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jiang, Kaifeng, Riki Takeuchi, and David P. Lepak. 2013. Where do we go from here? New perspectives on the black box in strategic human resource management research. Journal of Management Studies 50: 1448–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kakkar, Shiva, Ssanket Dash, Neharika Vohra, and Surajit Saha. 2020. Engaging employees through effective performance management: An empirical examination. Benchmarking: An International Journal 27: 1843–60. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kaufman, Bruce E. 2020. The real problem: The deadly combination of psychologisation, scientism, and normative promotionalism takes strategic human resource management down a 30-year dead end. Human Resource Management Journal 30: 49–72. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kaufman, Roger, and John M. Keller. 1994. Levels of evaluation: Beyond Kirkpatrick. Human Resource Development Quarterly 5: 371–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Keeping, Lisa M., and Paul E. Levy. 2000. Performance appraisal reactions: Measurement, modeling, and method bias. Journal of Applied Psychology 85: 708–23. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kraiger, Kurt, and Kevin J. Ford. 2021. The Science of Workplace Instruction: Learning and Development Applied to Work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 8: 45–72. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Kraiger, Kurt, Kevin J. Ford, and Eduardo Salas. 1993. Application of Cognitive, Skill-Based, and Affective Theories of Learning Outcomes to New Methods of Training Evaluation. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 311–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology . New Delhi: SAGE Publications Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lawler, Edward E. 2003. Reward Practices and Performance Management System Effectiveness. Organizational Dynamics 32: 396–404. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Levy, Paul E., and Jane R. Williams. 2004. The social context of performance appraisal: A review and framework for the future. Journal of Management 30: 881–905. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Levy, Paul E., Steven T. Tseng, Cristopher C. Rosen, and Sarah B. Lueke. 2017. Performance management: A marriage between practice and science—Just say ‘i do’. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 35: 155–213. [ Google Scholar ]

- Longenecker, Clinton O., Patrick R. Liverpool, and Kathelyn Y. Wilson. 1988. An assessment of manager/subordinate perceptions of performance appraisal effectiveness. Journal of Business and Psychology 2: 311–20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- McKenzie, Joanne E., Sue E. Brennan, Rebecca E. Ryan, Hilary J. Thomson, Renea V. Johnston, and James Thomas. 2023. Capítulo 3: Definindo os critérios para inclusão dos estudos e como eles serão agrupados para a síntese. In Manual Cochrane para Revisões Sistemáticas de Intervenções versão 6.4 (atualizado em agosto de 2023) . Edited by Julian P. T. Higgins, James Thomas, Jacqueline Chandler, Miranda Cumpston, Tianjing Li, Matthew J. Page and Vivian A. Welch. Annan: Cochrane. [ Google Scholar ]

- Modipane, Pheagane I., Petrus A. Botha, and Thonja Blom. 2019. Employees’ perceived effectiveness of the performance management system at a north-west provincial government department. Journal of Human Resource Management 17: 1–12. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mok, Mandy K. M., and Yeen Y. Leong. 2021. Factors affecting the effectiveness of employees’ performance appraisal in private hospitals in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Society 22: 257–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy, Kevin R. 2020. Performance evaluation will not die, but it should. Human Resource Management Journal 30: 13–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Murphy, Kevin R., and Jeanette N. Cleveland. 1995. Understanding Performance Appraisal: Social, Organizational, and Goal-Based Perspectives . Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nankervis, Alan R., Pauline Stanton, and Pat Foley. 2012. Exploring the rhetoric and reality of performance management systems and organisational effectiveness—Evidence from Australia. Research and Practice in Human Resource Management 20: 40–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paauwe, Jaap, and Paul Boselie. 2005. HRM and Performance: What’s Next? CAHRS Working Paper 5: 1–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Research Methods and Reporting 372: 71. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts, Gary E. 1992. Linkages Between Performance Appraisal System Effectiveness and Rater and Ratee Acceptance. Review of Public Personnel Administration 12: 19–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Roberts, Gary E. 1995. Municipal Government Performance Appraisal System Practices: Is the Whole Less than the Sum of its Parts? Public Personnel Management 24: 197–221. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schleicher, Deidra J., Heidi M. Baumann, David W. Sullivan, and Junhyok Yim. 2019. Evaluating the effectiveness of performance management: A 30-year integrative conceptual review. Journal of Applied Psychology 104: 851–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Schleicher, Deidra J., Heidi M. Baumann, David W. Sullivan, Paul E. Levy, Darel C. Hargrove, and Brenda A. Barros-Rivera. 2018. Putting the System into Performance Management Systems: A Review and Agenda for Performance Management Research. Journal of Management 44: 2209–45. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sharma, Neha P., Tanuja Sharma, and Madhushree N. Agarwal. 2021. Relationship between perceived performance management system (PMS) effectiveness, work engagement and turnover intention: Mediation by psychological contract fulfillment. Benchmarking: An International Journal 29: 2985–3007. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Soltani, Ebrahim, Robert Van Der Meer, John Gennard, and Terry Williams. 2003. A TQM approach to HR performance evaluation criteria. European Management Journal 21: 323–37. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Stanton, Pauline, and Alan Nankervis. 2011. Linking strategic HRM, performance management and organizational effectiveness: Perceptions of managers in Singapore. Asia Pacific Business Review 17: 67–84. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Upadhyay, Rajesh K., Kaliqur R. Ansari, and Pankaj Bijalwan. 2020. Performance Appraisal and Team Effectiveness: A Moderated Mediation Model of Employee Retention and Employee Satisfaction. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective 24: 395–405. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Van Waeyenberg, Thomas, and Adelian Decramer. 2018. Line managers’ AMO to manage employees’ performance: The route to effective and satisfying performance management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 29: 3093–114. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wall, Toby D., Jonathan Michie, Malcolm Patterson, Stephen J. Wood, Maura Sheehan, Chris W. Clegg, and Michael West. 2004. On the validity of subjective measures of company performance. Personnel Psychology 57: 95–118. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wright, Patrick M., and Gary C. McMahan. 1992. Theoretical Perspectives for Strategic Human Resource Management. Journal of Management 18: 295–320. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wright, Patrick M., and Michael D. Ulrich. 2017. A road well traveled: The past, present, and future journey of strategic human resource management. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 4: 45–65. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Phenomenon Level | Dimension | Frequency | Criteria | Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Individual/Employee | Reaction | 41 | 72 | Fairness | 24 | 42 |

| Accuracy | 20 | 35 | ||||

| Satisfaction | 14 | 25 | ||||

| Usefulness | 13 | 23 | ||||

| Affectivity | 8 | 14 | ||||

| Learning | 31 | 54 | Attitude | 18 | 32 | |

| Skill | 17 | 30 | ||||

| Knowledge | 13 | 23 | ||||

| Transfer | 39 | 68 | Job Performance | 20 | 35 | |

| Motivation | 18 | 32 | ||||

| Job Attitudes | 16 | 28 | ||||

| Interpersonal Relationship | 11 | 19 | ||||

| Well-being | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Unit/Organizational | Operational Results | 16 | 28 | Productivity | 10 | 18 |

| Turnover | 7 | 12 | ||||

| Innovation | 6 | 11 | ||||

| Workforce | 4 | 7 | ||||

| Financial Results | 3 | 5 | Profitability | 3 | 5 | |

| Financial Return | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Market Share | 3 | 5 | ||||

| External Environment | Societal Impact | 4 | 7 | Customer Satisfaction | 4 | 7 |

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

de Araújo, M.L.; Caldas, L.S.; Barreto, B.S.; Menezes, P.P.M.; Silvério, J.C.d.S.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Serrano, A.L.M.; Neumann, C.; Mendes, N. How to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Performance Management Systems? An Overview of the Literature and a Proposed Integrative Model. Adm. Sci. 2024 , 14 , 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060117

de Araújo ML, Caldas LS, Barreto BS, Menezes PPM, Silvério JCdS, Rodrigues LC, Serrano ALM, Neumann C, Mendes N. How to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Performance Management Systems? An Overview of the Literature and a Proposed Integrative Model. Administrative Sciences . 2024; 14(6):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060117

de Araújo, Mariana Lopes, Lucas Soares Caldas, Bruna Stamm Barreto, Pedro Paulo Murce Menezes, Júlia Cássia dos Santos Silvério, Laís Campos Rodrigues, André Luiz Marques Serrano, Clóvis Neumann, and Nara Mendes. 2024. "How to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Performance Management Systems? An Overview of the Literature and a Proposed Integrative Model" Administrative Sciences 14, no. 6: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14060117

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Performance Management Revolution

- Peter Cappelli

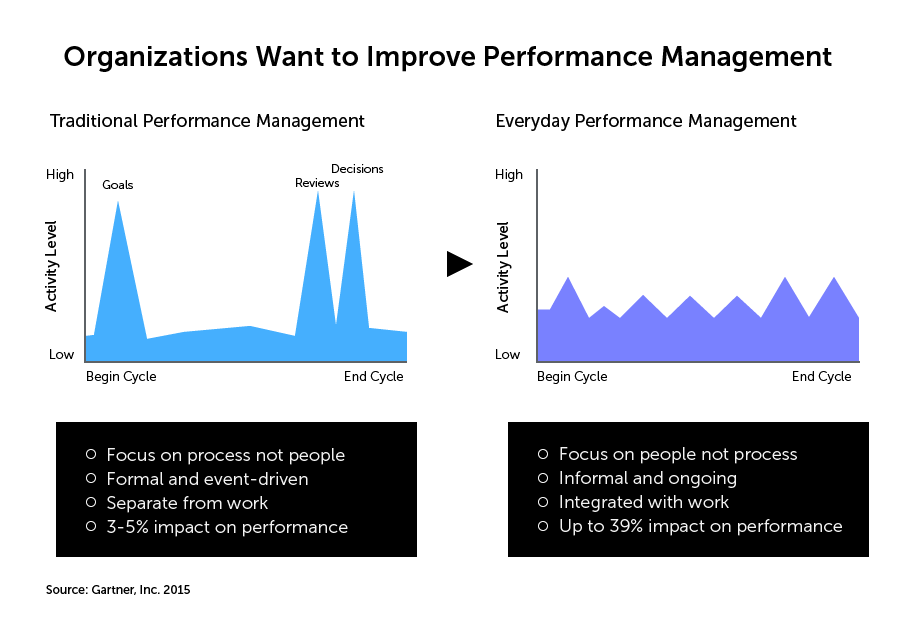

Hated by bosses and subordinates alike, traditional performance appraisals have been abandoned by more than a third of U.S. companies. The annual review’s biggest limitation, the authors argue, is its emphasis on holding employees accountable for what they did last year, at the expense of improving performance now and in the future. That’s why many organizations are moving to more-frequent, development-focused conversations between managers and employees.

The authors explain how performance management has evolved over the decades and why current thinking has shifted: (1) Today’s tight labor market creates pressure to keep employees happy and groom them for advancement. (2) The rapidly changing business environment requires agility, which argues for regular check-ins with employees. (3) Prioritizing improvement over accountability promotes teamwork.

Some companies worry that going numberless may make it harder to align individual and organizational goals, award merit raises, identify poor performers, and counter claims of discrimination—though traditional appraisals haven’t solved those problems, either. Other firms are trying hybrid approaches—for example, giving employees performance ratings on multiple dimensions, coupled with regular development feedback.

The focus is shifting from accountability to learning.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

By emphasizing individual accountability for past results, traditional appraisals give short shrift to improving current performance and developing talent for the future. That can hinder long-term competitiveness.

The Solution

To better support employee development, many organizations are dropping or radically changing their annual review systems in favor of giving people less formal, more frequent feedback that follows the natural cycle of work.

The Outlook

This shift isn’t just a fad—real business needs are driving it. Support at the top is critical, though. Some firms that have struggled to go entirely without ratings are trying a “third way”: assigning multiple ratings several times a year to encourage employees’ growth.

When Brian Jensen told his audience of HR executives that Colorcon wasn’t bothering with annual reviews anymore, they were appalled. This was in 2002, during his tenure as the drugmaker’s head of global human resources. In his presentation at the Wharton School, Jensen explained that Colorcon had found a more effective way of reinforcing desired behaviors and managing performance: Supervisors were giving people instant feedback, tying it to individuals’ own goals, and handing out small weekly bonuses to employees they saw doing good things.

- Peter Cappelli is the George W. Taylor Professor of Management at the Wharton School and the director of its Center for Human Resources. He is the author of several books, including Our Least Important Asset: Why the Relentless Focus on Finance and Accounting Is Bad for Business and Employees (Oxford University Press, 2023).

- AT Anna Tavis is a clinical associate professor of human capital management at New York University and the Perspectives editor at People + Strategy, a journal for HR executives.

Partner Center

Performance management systems: Trade-off between implementation and strategy development

- Open access

- Published: 02 August 2022

- Volume 16 , pages 280–295, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Roman A. Lewandowski Ph.D. ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9589-0629 1 &

- Giuseppe T. Cirella Ph.D., D.Sc. ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0810-0589 2

5860 Accesses

34 Citations

Explore all metrics

The aim of this study is to understand how performance management systems (PMS) affect the strategy development process. The research examines PMS implementation and evaluates how the implementation of PMS links measures with rewards, i.e., financial and non-financial, to influence strategy formation. This qualitative study is based on 74 semi-structured face-to-face in-depth interviews with board members, mid-level managers, and other employees in nine organizations. Theory-building is comprised of the transcribed and analyzed interviews using MAXQDA 12 software. Theory-testing, i.e., a verificatory stage, consisted of analyzing previously identified phenomena. Results suggest that PMS affects strategy development processes by influencing both employee relational and calculative trust in their superiors. It also indicates a direct behavioral effect on employee knowledge sharing and manager trust in their subordinates. As a result, this may determine the extent to which managers exploit shared knowledge while formulating a strategy. The research demonstrates there is a trade-off between PMS implementation and strategy development. A gap in the literature is filled by integrating relational and calculative trust with PMS implementation and showing how such changes in trust mediate knowledge sharing behavior and strategy development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations

Reactions towards organizational change: a systematic literature review

How Virtual are We? Introducing the Team Perceived Virtuality Scale

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Performance management systems (PMS) have achieved immense popularity in academic and business communities. PMS generally can be defined as a set of management control mechanisms with the overall purpose of facilitating the delivery of organizational goals by influencing people’s behavior and performance (Broadbent and Laughlin 2009 ; Ferreira and Otley 2009 ) by embracing five fundamental elements: (1) a planning phase which includes the goals that reflect organizational expectation and delineate performance; (2) a measurement comprising of the metrics used to operationalize performance; (3) a review referring to the evaluation and feedback of performance information; (4) a performance-related reward system, and (5) a “refreshing” phase (Franco-Santos and Otley 2018 ). “Refreshing” of PMS is a crucial element since the environment and the organization itself changes over time and, thus, a constant re-evaluation of the existing performance measures as well as PMS as a whole must be rendered (Schleicher et al. 2018 ). PMS is an important tool in operations and strategic management since it allows for the integration of sets of metrics, namely, quantitative and qualitative data. Such data is used to quantify strategic objectives both on the operational and business level, so as to make it possible for decision making to better formulate (and adapt) a business model of efficiency and effectiveness of an organization’s actions (Glas et al. 2018 ). Additionally, it must be flexible to adapt to strategic changes that otherwise may affect performance and overall success.

From the literature, the most prominent PMS appears to be the balanced scorecard (BSC) (Bryant et al. 2004 ; de Waal and Kourtit 2013 ) which became a standard for other PMS dating to the early 2000s (e.g., Rampersad ( 2003 )). Speckbacher et al. ( 2003 ) announced that 44% of companies worldwide claim to be using BSC, and more recent studies prove this popularity (Tapinos et al. 2011 ). A detailed analysis of PMS implementation indicated, however, that many organizations started its implementation but only a few of them implemented it fully, i.e., linking strategic and operations objectives with financial and nonfinancial measures as well as combining these measures with rewards (Albertsen and Lueg 2014 ; Speckbacher et al. 2003 ). This linkage seems to be a central aspect of every PMS’ full development (Glas et al. 2018 ; Lee and Yang 2011 ) as a strategic management system, capable of translating strategy into action (Kaplan and Norton 2006 ; Malmi and Brown 2008 ). Decades of research has shown that there is no agreement among researchers of whether PMS improves or deteriorates organizational performance (Bonner and Sprinkle 2002 ; Bourne et al. 2007 ; Laitinen 2003 ; Liedtka et al. 2008 ; Nørreklit 2000 , 2003 ; Nørreklit et al. 2012 ; de Waal and Kourtit 2013 ). Extant studies have indicated a number of PMS weaknesses (Butler et al. 1997 ; Laitinen 2003 ; Levy et al. 2017 ; Liedtka et al. 2008 ; Nørreklit 2000 , 2003 ; Nørreklit et al. 2012 ) and negative unintended consequences such as information manipulation (Kalgin 2014 ; Li 2015 ), selective attention (Kerpershoek et al. 2014 ), myopia, gaming, illusion of control (Franco-Santos and Otley 2018 ), as well as increased tendency towards being in a rigid state, constraining responsiveness, and resisting change (Mannion and Braithwaite 2012 ). However, they have not pointed out that its primary purpose of supporting strategy implementation may negatively affect strategy formation. Thus, confirmation of PMS influence on strategy formation and explanation of mechanism changes would be an essential contribution to the existing theory on operations strategy process.

There is a significant number of publications concerning PMS, but only a few of them investigated its full implementation, e.g., where measures were linked with rewards (Albertsen and Lueg 2014 ) and those regarding strategy development in a processual model (Tapinos et al. 2011 ) work is an exceptional example that examines the impact of BSC on six elements of the strategy process—quantitatively and internationally. Their research confirmed BSC is an effective tool for strategy implementation and rejected the idea of its influence on strategy development. However, their lack of statistically significant evidence may have originated from a number of research limitations, i.e., by not considering different levels of BSC implementation (Lee and Yang 2011 ; Speckbacher et al. 2003 ) such as the link between measures and rewards. These limitations can considerably alter results since only a small portion of organizations link measures and rewards in their BSC (Albertsen and Lueg 2014 ; Speckbacher et al. 2003 ). Even assuming that Tapinos et al.’s ( 2011 ) quantitative investigation was suitable for examining the statistical correlation between users and non-users of BSC—i.e., regarding their overall view of BSC impact on the strategy process—it was unable to reveal sophisticated mechanisms underpinning strategy formation. At length, there is an important scientific gap in the literature on how the implementation of PMS links measures with rewards to influence strategy formation. Similarly, from the literature concerning operations or other types of functional strategy formation, there are no studies referring to the influence of PMS on strategy formation. Moreover, evidence that PMS may affect strategy development is perceptible, since strategy implementation is not a one-direction process but an ongoing flow in which development and implementation are intertwined. This engagement is central to how it affects trust and the trade-off relationship between strategy development and strategy implementation. Several studies investigated this relationship (Deluga 1995 ; Earley 1986 ; Mayer and Davis 1999 ; Mayer and Gavin 2005 ; Podsakoff et al. 1990 ; Rich 1997 ; Zaheer et al. 1998 ), but very few investigated the interplay between trust and PMS—and the few that did, did not sufficiently explained the relationship (Chenhall and Langfield-Smith 2003 ; Yang and Holzer 2006 ). There are no studies which investigate in what way the implementation of PMS affects trust, what types of trust, and how the changes of trust mediate knowledge sharing behavior and, hence, strategy development. This paper addresses these questions as complementary issues to the examination on PMS linkages.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 framework and definitions, 2.1.1 strategy process and strategy formation.

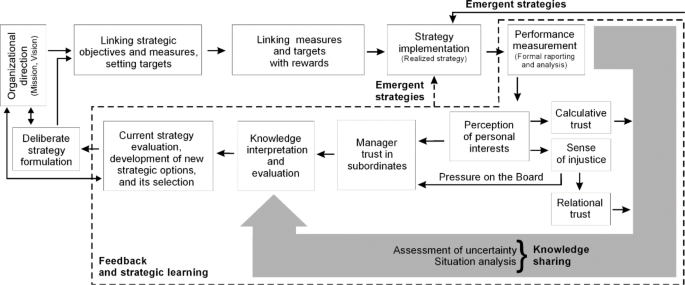

The strategy process can be defined “as a more or less formalized, periodic process that provides a structured approach to strategy formulation, strategy implementation, and control” (Wolf and Floyd 2013 ). This definition, when applied to strategy formulation supporting organizations, specifies three primary stages, including: (1) principal problems, (2) set objectives (i.e., by analyzing and evaluating alternatives), and (3) selection of the strategy for implementation (Mintzberg et al. 1998 ). The first stage requires information from the organization and their environment to detect strategic opportunities needed to narrow down any suitable alternative. The second stage focuses on the implementation of the chosen alternative by translating strategy into action (Johnson et al. 2008 ; Kaplan and Norton 1996 ). The last stage is the control to what extent the chosen strategy is achieved. Figure 1 depicts a model of strategy process adapted from Dyson ( 2000 ), Tapinos et al. ( 2011 ), and Kaplan and Norton ( 1996 , 2006 ). It illustrates not only the business level strategy but also the functional strategies such as operations, supply chain, and marketing strategy. As such, an organization is capable of developing effective strategies when any of the elements in the model are in place and working effectively (Dyson 2000 ) as well as when the functional strategies are aligned with the business level strategy (Adamides 2015 ).

Strategy process after the implementation of a performance management system, adapted Dyson ( 2000 ), Tapinos et al. ( 2011 ), and Kaplan and Norton ( 1996 , 2006 )

Deliberate strategy formulation, both business level and functional, refers to the rational, formal, and centralized top-down process performed by top managers. It is driven by a situation analysis comprised of identifying an organization’s (or function’s) principal problems as well as monitoring and anticipating its internal and external environment. It is important, that the functional strategies are developed within the guidelines of the overall business strategy (Kim et al. 2014 ; Kremer 2019 ). The effectiveness of a situation analysis depends on the source of information and transfer of knowledge to back the monitoring of broad market trends—inclusive of technologies and policies—as well as internal capabilities. Thus, the central element of the model is feedback and strategic learning, which can be regarded as both feedback and feedforward control. Feedback control is focused on monitoring whether determined plans and objectives are achieved. The feedforward approach is future-oriented. It utilizes accessible information from performance measurement and employees observing and experiencing internal and external uncertainties that may affect previous assumptions based on the selected strategy. Through feedback and strategic learning, knowledge is interpreted and evaluated by employees and forwarded up the organizational hierarchy (Bol 2011 ; Ittner et al. 2003 ). Based on this structure, managers evaluate the current strategy, develop new strategic options, and select, according to their knowledge, the most effective. In the process of strategy development, the most critical factor is the quality of knowledge managers acquire from their subordinates and other sources (Mintzberg 1994 ).

The next element of the adopted model links the strategic objectives with measures by formulating performance targets. This is the fundamental element that improves strategy understanding and allows for its realization (i.e., the activities supporting its implementation) (Kaplan and Norton 1996 ; Kim et al. 2014 ; Kremer 2019 ). Linking measures and targets with rewards strengthen employee willingness to achieve these targets by involving them at a personal level. Objectives, measures, targets, and rewards are fundamental parameters of every PMS. The actual set of decisions are not only the results of purposeful planning (i.e., a deliberate strategy) but also are affected by any emergent strategies (Mintzberg and Waters 1985 ). Emergent strategies are autonomous strategic decisions or actions taken by employees located deep inside the organization as a response to immediate changes in their task environment or as a reaction to perceived opportunity (Burgelman 1996 ; Mintzberg 1978 ; Mintzberg and Waters 1985 ). Employee autonomous strategic actions can also be linked to the feedback and learning process since they acquire knowledge from their day-to-day activities specific to the organization’s ecosystem as well as on certain specificities on how performance (i.e., optimization) can be rendered (Kremer 2019 ). Through the immersion of the feedback and strategic learning process employees are not only sharing but also gaining knowledge which could drive individual actions “off the management radar” and be entirely different than those recommended by top managers. In relation to Fig. 1 , deliberate strategies are the result of managers interpreting the knowledge from the feedback and strategic learning process. Emergent strategies are initiatives taken by employees, partially based on the same feedback and strategic learning process, however entirely different and independent from those of top managers, i.e., marked by a dotted arrow. Strategies emerging without connection with the organizational feedback and strategic learning process are marked by a solid arrow.

Both types of strategy development processes indicate the critical role of middle managers and other low-level employees (Andersen and Hallin 2017 ; Burgelman 1983 ; Jarzabkowski and Balogun 2009 ; Kremer 2019 ; Spee and Jarzabkowski 2011 ). Recent strategic research emphasizes “compromises, interactions, and negotiations that take place over the planning process [and] social and political interactions over strategy making” (Jarzabkowski and Balogun 2009 ). Thus, the important issue is how the roles and responsibilities of middle- and low-level actors emanate in organizations and how this influences knowledge sharing and strategy development? Wooldridge et al. ( 2008 ) underline that “what makes middle managers unique is their access to top management coupled with their knowledge of operations.” Hence, they are an essential nexus of delivering knowledge about markets, competitors, and new technologies—gathered by themselves or acquired from their subordinates. Other research has demonstrated that middle managers involved in strategy development activities also improve organizational performance (Wooldridge and Floyd 1990 ) and strategic planning (Schaefer and Guenther 2016 ), two factors that compliment strategy formation experimentation.

2.1.2 Knowledge and trust

Knowledge can be defined as information integrated with personal experience, i.e., a subjective vision of reality located in a particular field of activity; in other words, a subjective interpretation of reality dependent on individual actors’ values, interests, experience, and view of the truth. Foucault ( 2019 ) claimed that there are several truths but different ways one can express the same truth (White and Jacques 1995 ; Willcocks 2004 ). This means that each person can possess their own version of the truth, and that version of the truth may depend on individual interests. As there is no “one truth” and knowledge is “a subjective vision,” organizational actors may perceive and interpret reality in a divergent manner possibly more congruent with their interests. Further, they may exploit knowledge and subjectivity of the truth to influence others by sharing knowledge in such a way that supports their interests (Westley and Mintzberg 1989 ) and thus affect strategic learning. In this environment, trust in organizational members appears to be a vital factor. Ko et al. (2005) claim that trust facilitates knowledge transfer, i.e., defined as an exchange of knowledge between a source and a recipient, in a way that knowledge can be applied. Trust makes people more willing to share genuine information (Holste and Fields 2010 ; McKnight and Chervany 2006 ; Sankowska 2013 ), even sensitive information, which can be used against them (Dirks 2006 ; Gargiulo and Ertug 2006 ; Szulanski 1996 ). The willingness to share genuine information results from trust properties, as trust leads to the optimistic acceptance of vulnerable situations in which the trustor (i.e., trusting party) believes the trustee (i.e., to-be-trusted party) will care for the trustor’s best interests, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control the trustee (Hall et al. 2001 ). The above conceptualization of trust draws attention to the trustor’s willingness to engage in risk-taking behavior. For example, employees may share knowledge which is vital for an organization but affects their interests mostly in situations when they trust that managers will ensure their interests in the future. The extent to which the trustor will be willing to accept vulnerability to other people depends on the perception of a particular person’s trustworthiness. Overall, the decision of whether to adopt or share knowledge is based on trust (Renzl 2008 ).

Rousseau et al. ( 1998 ) claim that managers can promote two types of trust: calculative and relational. When subordinates develop calculative trust in their managers, they believe that their actions complying with manager requirements will benefit them in calculable ways (Williamson 1993 ) and every fulfilled obligation concerning reward for performance strengthens this type of trust. Subordinates who maintain relational trust believe that their managers will consider their interests irrespective of their ability to control these managers (Rousseau et al. 1998 ; Sitkin and Roth 1993 ). In order to have trust in managers, employees need to believe not only that superiors will hold their words (i.e., are persons of integrity), but also have the ability and willingness to take care of their interests.

In organizations, it is not only important to have employee trust in managers but also manager trust in their subordinates, since it may determine the extent to which managers use the knowledge shared by their employees. However, how can managers recognize who transfers genuine knowledge and who is providing a distorted view based on their own interests? Dirks and Ferrin ( 2002 ) claim that beyond the previous experience with employees, managers might evaluate their level of trust in subordinates based on the source and degree of conflict with them. They may also judge the misalignment of task preferences or goals, or incompatibility of values between themselves and their subordinates as well as evaluate the risk of employee opportunism (Williamson 1993 ). Trustworthiness may also be assessed by the estimation of the level of motivation to lie, i.e., if subordinates have something to gain by lying (Hovland et al. 1953 in Mayer et al. ( 1995 )). When measures are linked to rewards, there are always some underlying interests. Thus, it is essential to investigate how patterns of trust relations and knowledge sharing behavior affected by PMS implementation influence strategy development.

2.2 Research methods

While it is understood how PMS influence strategy implementation, it is not understood how the linkage of strategic objectives with financial and non-financial measures and measures with rewards affect strategy development. To deepen the understanding of strategy development process under PMS, the research was designed as a type of “naturalistic inquiry” in which inductive reasoning was used to obtain insights (Lincoln and Guba 1985 ). During the field study, interview data were gathered from top managers and some key employees, including middle managers, directly involved with the organizational PMS as well as from relevant archival documents accessible in each organization. Hence, part of the dataset is perceptual in nature and may reflect informant and author bias (i.e., something not easily observable). The study, however, is designed in a way which should diminish the effects of this bias via the division of a two-stage process: (1) theory-building and theory-testing and (2) multiple-case study design in each stage. According to a number of studies, multiple cases typically leads to a more robust, generalizable, and testable theory than single-case research. It, among others, allows comparisons between cases to clarify whether an emergent phenomenon is unique for one case or is present in all of them (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ; Tsang 2014 ; Yin 2014 ). In this replication, logic cases are treated as a series of experiments, each serving to confirm or disconfirm inferences (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ). Multiple cases also deliver more empirical evidence supporting emergent findings.

The clear division between theory-building and theory-testing stages could be perceived as artificial, and one might consider that just analyzing more cases together would be more appropriate for congruency with the analytic cycle of moving from an inductive to more deductive attitude as the interpretations crystallized (Miles et al. 2014 ). In this research, however, the split is justified by the construction of distinct research samples and different manners of data analysis. For the theorybuilding stage, the selected organizations utilized were ones that fully implemented PMS and then abandoned it after a few years. It was assumed that organizations which abandoned the PMS must have noticed some critical problems with the concept. In such cases, “hard” evidence was sought—reasons which convinced organizations to abandon further exploitation of PMS. While in the theory-testing stage, the selected entities were organizations that currently use PMS, with the assumption that strategy development issues should also exist but were not visible. Thus, studying such cases, small signs of phenomena revealed in the first stage were sought. Combining organizations that abandoned the PMS and those which were actively using them at the time of the research brought together retrospective and real-time data. Retrospective accounts allowed the research to delve into organizations that experienced time after PMS abandonment and were able to see from a distance some changes in phenomena, while real-time data improved in-depth understanding of how events evolve over time. This, according to Eisenhardt and Graebner ( 2007 ), should mitigate bias concerning retrospective sensemaking. If retrospective bias were an issue, significant differences in accounts in these two groups of cases should appear, however, it did not.

2.2.1 Sampling

The research sample in the theory-building stage consists of three organizations that abandoned BSC and one that discontinued another PMS. In this study, BSC and the other PMS are considered the same (Kaplan and Norton 2006 ; Malmi and Brown 2008 ), i.e., regardless of how an organization named it, since linked objectives with financial and non-financial measures are associated with rewards. The research started from one case (i.e., “Konsta”) that was accidentally discovered by the first author during other similar research which sparked the idea of connecting PMS utilization and strategy development. Through consulting companies, seven additional organizations were found in Poland from different sectors which abandoned their PMS, five of them (i.e., “Konsta”, “Office”, “Hospital”, “Construction”, and “Center”) agreed to participate in the research. For the theory-testing stage, two organizations were selected that actively use BSC (i.e., “Bureau” and “Furniture 1”) and two firms that exploit the other PMS (i.e., “Furniture 2” and “Center” ) (Table 1 ). During the research it appeared that organizations hesitate to reveal information about their internal problems with PMS. To motivate informants to provide accurate data, confidentiality and anonymity for all organizations in both stages were agreed on and promised (Miller et al. 1997 ).

2.2.2 Data collection

In the theory-building stage, 41 semi-structured face-to-face in-depth interviews were conducted from September 2015 to November 2016 and from February 2022 to March 2022, while in the theory-testing stage 33 informants were interviewed from June 2016 to January 2017 and from February 2022 to March 2022. All 74 interviews were recorded and later transcribed, and analyzed using MAXQDA 12 software—i.e., software that is specifically designed for qualitative analysis. Apart from the chief executive officers (CEOs) or board members, typical case studies regarding BSC also include mid-level managers and some key employees since, according to the literature (Albertsen and Lueg 2014 ), they may play an important role in strategy formation processes. Additionally, multiple informants mitigate subject bias (Miller et al. 1997 ) and lead to a thicker, more elaborated model (Schwenk 1985 ). In every case, the first interview was conducted with the CEO, who was also asked to indicate the most experienced staff with PMS. In two cases, the CEO, chief financial officer, and some key informants who had implemented BSC changed their place of work, but they were interviewed anyway. Taking informants from different levels (i.e., superiors and subordinates) allowed for comparative interviews and some ancillary questions relating to the same events. This was important since informants had to recall facts from the past.

The duration of each interview ranged from 30 to 115 min and began with open-ended questions about the reasons for PMS implementation, possible resignation or its continuation, as well as the time before the PMS implementation and after the eventual abandonment. To avoid responses that could lead informants to specific answers, direct questions regarding strategy development were not asked. It was preferred to gather data more freely to allow the informants’ natural, undirected narration.

2.2.3 Theory-building stage

In the theory-building stage, cases were used as a base to inductively recognize phenomena and patterns of relationships—firstly within one case and then across all five cases (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007 ). Interviews and relevant sections from archive materials were transcribed as well as grouped around repeated statements and related subjects, creating qualitative unit types (Graneheim and Lundman 2004 ). Then, to facilitate the understanding of the unit types and relationships contained in the dataset, they were condensed to a certain degree, i.e., the reduction of the text while still maintaining the same meaning. This consisted mainly of removing redundant statements. Table 2 presents an example of how the process was performed. Next, the condensed unit types were carefully reviewed with frequent reference to the original transcripts. At this point, the analysis was, to some extent, latent. Condensed unit types were interpreted using what already was known about the subject and the context within which the data was gathered to create themes (Downe-Wamboldt 1992 ). While developing themes, it was obvious that there was no single correct meaning but only the most probable from a particular perspective. Once all themes were established, their meaning were triangulated with archival materials (Yin 2014 ). The themes are defined as an expression of the observed and latent (i.e., subjective) content of the dataset.

When the procedure to develop themes was initiated, similar unit types were collated and new meanings appended in subsequent cases. This cyclical procedure codified all the cases to create the condensed unit types. In a few instances, some informants were also called back to clarify meanings. All coherent unit types were condensed and summed up into themes and justificatory narratives. Only the unit types which were replicated, in some way, in all cases remained. When all themes were identified, the research became more systematical and iterative between the themes and relevant literature to develop appropriate codes and phenomena. Next, the research concentrated on searching through literature without any preconceptions or established theory using keywords from condensed unit types and themes. When some threads were found (i.e., areas of research), the literature was further refined to those more relevant to knowledge sharing, communication, strategy process, and trust. In this procedure, nine phenomena were identified which were coded as follows: the subjectivity of PMS parameters, perception of personal interests, sense of injustice, trust in managers, enhancement of calculative trust, unfulfilled expectations, psychological contract, pressure on the board, and manager trust in subordinates.

2.2.4 Theory-testing stage

Data analysis in the theory-testing stage was different. While during the theory-building stage, the search concentrated on objective evidence, here the focus went to less apparent signs of previously identified phenomena. Replication logic also determined how informants were interviewed in this verificatory stage. After asking similar questions as in the first stage, the research openly referred to the phenomena from the emergent theory. In this stage, two phenomena identified in the previous stage were not confirmed: unfulfilled expectations and psychological contract. The other seven phenomena were present in all four cases, although with a few informants it was confirmed only after direct questions. Since the interpretation of the dataset always involved multiple meanings and the researchers’ interpretation and personal history, a draft report (i.e., before translation) was consulted with the CEO of each organization. In the draft report, the words “manager”, “superior”, “executive”, and “CEO” were assigned to top managers and board members including city mayor, while “employee” and “subordinate” were assigned to lower rank managers.

3 Results and discussion

Seven categories were identified as possibly being associated with strategy development processes in organizations using PMS: (1) subjectivity of PMS parameters, (2) perception of personal interests, (3) sense of injustice, (4) trust in managers, (5) enhancement of calculative trust, (6) pressure on the board, and (7) manager trust in subordinates.

3.1 Subjectivity of PMS parameters: Identification of the cause-and-effect relationships, selection of measures of intangible assets, and determination of their optimal value

The study revealed that at the beginning of BSC implementation organizations were able to reach a consensus concerning measures of tangible assets quite quickly. However, to establish measures of intangible assets linked to valued organizational outcomes, their reference values and cause-and-effect relationships were much more challenging. According to the interviewees, non-financial measures proposed by the consultants, and also mentioned in the literature (Ivanov and Avasilcăi 2014 ), were problematic to quantify and difficult to interlink correlatively with the organizational outcome. Respondents also indicated a lack of objectivity concerning both reasons for the selection of measures and the assessment of their optimal value. These obstacles weakened the effectiveness of the boards’ social accounts. For example, the CEO of “Konsta” noted:

There is no problem with the development of measures relating to production processes, quality, or sales, but that we have done it without BSC. [...] I was convinced to use BSC with the promise that it would allow the measurement of our intangible assets and protect our growth in the future. [...] But when it came to its implementation, it turned out that the consultants did not have much to offer.

Malina and Selto ( 2001 ) suggest critical conditions that measure optimal value should be “accurate, objective, and verifiable. Otherwise, measures will not reflect performance and may be manipulated, or managers could in good faith achieve good measured performance but cause the organization harm.” In practice these conditions are rarely met. The chief financial officer of “Office” described it in this way:

In our network we tried a lot of non-financial indicators and most of them created problems. When we adopted sales growth, [...] they [employees] questioned it as unfair. They argued that offices which were effective earlier, already had a large share of their market, and had smaller growth opportunities than those which were initially lazier. [...] The absolute market share—as a measure—was also criticized because in large cities where there were lots of competing agencies, our share was only a few percent, but in smaller towns we were sometimes the only ones.

Hence, even in an organization that has a homogeneous network of offices, the choice of measures may favor some locations over another. Management can establish different levels of indicators for individual offices, but the problem of optimal value for each office remains. Managers also indicated, that rarely they were able to identify cause-and-effect relationships before the implementation of new objectives and measures, thus they had to test them in practice, which led to their frequent changes. Other researchers also raised similar problems, claiming comparable results lead to an imperfect BSC structure (Chenhall and Langfield-Smith 2007 ; Laitinen 2003 ; Nørreklit 2000 , 2003 ; Nørreklit et al. 2012 ).

3.2 Perception of personal interests, sense of injustice, and trust in managers

In all of the surveyed organizations, the same pattern was repeated to a greater or lesser extent. All changes to BSC parameters, especially those related to rewards affected the interest structure in the organization. For some employees this was also perceived as displeasing or as an incumbrance to their position. As such, managers tried to explain the reason for their decisions, but as was mentioned earlier, many goals and measures were determined arbitrarily and they encountered difficulties in terms of their rational justification to make them. People who felt that they might lose would develop a sense of injustice and consequently suspect others, who in their opinion gained. This led to conflicts within the board. An employee from “Office” complained, “when superiors do not clearly explain reasons for new goals or measures, and we see that others gain […] For us this means that they [the board] give in under the pressure from the stronger [stakeholders] […] How can we trust them then?” When employees had problems in achieving desired results and boards had not reacted upon their claims they often felt unfairly treated and were losing relational trust in their executives (Dirks 2006 ; Robinson and Rousseau 1994 ). Managers also felt that subordinates lose trust in them; for instance, the CEO of “Konsta” said, “one change in the reward system is not a problem. After sometime people got used to new conditions, even if they were not convinced at the beginning, but frequent not well justified changes eventually undermine trust.” Before BSC implementation, board members were prepared for BSC reviews and changes. However, most of them admitted they did not envision that changes would be so frequent and in practice produced a number of negative consequences.

Executives emphasized that in many cases subordinates had complained that the changes of BSC were breaking their agreement with the company, although the modifications concerning rewards were within the legal framework of their formal employment agreements. The CEO of “Furniture 1” said:

After the implementation [of BSC] it turned out that certain measures in general cannot be achieved [...] and that staff did not question their changes. [...] The problem has been with measures in which employees successfully achieved. Change of these measures, mostly induced resistance and resentment, even though employees were informed that it was necessary—since in practice it appeared that they [these measures] did not support an [organizational] outcome. [...] I have to say that each change, especially when related to items associated with the rewards, the concept often undermined trust in us.

For each new objective, measure, or related reward adopted by employees, i.e., a kind of two-sided commitment can be said that it is not solely about remuneration. Additional notes included respect and the feeling that people are taken seriously. When employees devoted themselves to the realization of a goal, they expected that it would be important for the organization and that their contribution was to be appreciated. Frequent changes of objectives undermined this belief.

The team leader from “Konsta” stated, “when the board had set a goal, they expected us to engage in it wholeheartedly, […] people often devoted their private time. […] We expected that our work would be respected. […] When it occurred that the goal was changed after a short time we felt disrespected.” The research demonstrated that in organizations where the changes of BSC parameters were frequent (e.g., “Konsta”) and strategic goals ambiguous (e.g., “Hospital”), levels of conflicts with employees and their feeling of injustice were more intensive. In situations where goals were imposed by law or other forces independent from the organizations (e.g., regional government), or they were easy to explain (e.g., via effective social accounts), interviewees less intensively reported their feeling of injustice. A clerk from a local government mentioned, “sometimes the changes are incomprehensible to us, […] but what to do […] its politics! […] Our boss must somehow be involved in this.” This comment paralleled a number of individuals who were also working in regional and local government positions.

3.3 Enhancement of calculative trust and pressure on the board

Experienced managers learnt that frequent changes of BSC parameters connected with incentives may harm employee trust in them. They noted, however, especially at the beginning of BSC implementation, that effective performance measurement and related rewards schemes would substitute the loss of relational trust. A manager from “Office” said:

At the beginning of the implementation [BSC], I believed that employees do not need to have trust in us. It will be sufficient that they will efficiently carry out their tasks, achieve measures, and this should allow us to accomplish our objectives. [...] And, indeed at the beginning, staff are heavily involved in achieving agreed targets. [...] However, after a few changes of measures, I had the impression that they began to use different tactics, for example, they were approaching near optimum level, but did not cross it, although I think, they could.

In a broader sense, managers using BSC have built calculative trust which supports or substitutes relational trust. This is similarly noted by Fadlallah et al. ( 2018 ) and Spreitzer and Mishra ( 1999 ).

Trust based on financial incentives, invoked employee engagement mainly in these activities which brought them tangible benefits. Employees had known that measures were more or less arbitrarily determined by the board therefore they were trying to influence this process. They could do it by manipulating information they delivered to their superiors or by directly exerting pressure on them. Consequently, employees often were more focused on building pressure on the board to change BSC parameters, than overcoming external obstacles and stepping up efforts to achieve targets. The CEO of “Furniture 1” said, “I had the impression that sometimes employees were putting more energy in convincing us that a measure or goal is unachievable, than it would cost them to achieve it.” Rewards, as such, produced employee engagement mainly in these activities, which brought them benefits.

3.4 Manager trust in subordinates

Manager conflicts with employees in terms of objectives, measures, and rewards made executives suspicious of subordinates’ actions. Superiors realized that the interpretation of reality, communicated by the staff, might be misshaped by their interests. A few interviewed managers suggested that before BSC implementation, i.e., when the incentive schemes were based either on the aggregated financial indicators or on overall company performance, there was greater congruence between the organization and employee objectives—even though this relationship was much less intensive. However, after the assignment of specific measures, employee interests were more closely aligned to the measures than to organizational outcomes no matter how the market situation changed. This awareness (i.e., sometimes only faint suspicion) made the managers become more mistrustful to knowledge provided by employees, especially the one that could have an impact on the selection of BSC parameters. Generally, interviewees indicated that BSC may change the flow of information. The CEO of “Office” stated:

After linking measures to bonuses [...] in conversations [with the staff], I always had at the back of my head questions like: “what can they lose or gain by giving me this information?” and “what is being marginalized, or even ignored, and what is being overexposed?” [...] After the implementation [of BSC] we have become more distrustful of each other.

In the same tone, the hospital director admitted, “employees not only openly questioned some measures, but I am convinced that they also manipulate shared information to gain better rewards.” Hence, managers reaffirmed a potential awareness of mistrustful of employee knowledge and understood that the implementation of a BSC changes the flow of knowledge in an organization.

3.5 Strategy formation process after PMS implementation

The study indicates that the strategy development process is affected by PMS implementation, mostly through its influence on knowledge sharing behavior in an organization (Fig. 2 ). Each change within a set of PMS parameters may lead to a situation in which some people perceive that they are losing more or gaining less than others and develop a sense of injustice (i.e., moving closer towards victimhood). Frequent changes to some PMS parameters may lead to ongoing alteration of the organization’s structure (i.e., in terms of employee interest) and increase likelihood some employees may feel that their position worsens. In this situation, “victims” may struggle to assert their rights and may try to press the board to produce another modification of PMS to favor them. The influence can be explicit or implicit or both.

Strategy process after PMS implementation comprising of the identified phenomena

Explicit influence may be exerted by the open questioning of PMS parameters. Managers may reject victimhood claims or accept them and make appropriate modifications to the parameters. When they reject these claims, the “victims” might have a proof that the board has violated their interests, which may reduce employee relational trust in managers (Rousseau et al. 1998 ; Sitkin and Roth 1993 ). However, when superiors manage to convince employees that the changes were justified, the trust may be saved or even increased (Lines et al. 2005 ; Tucker et al. 2013 ). Acceptance of such claims in conjunction with amendments to PMS parameters does not automatically save trust, especially if repealing any previous decision caused a certain level of harm. According to interviewees, retreat may also reduce trust in managers since it proves that adopted parameters of PMS were arbitrary and showed that exerting pressure on managers is effective. Annulment of the decision might confirm managers susceptibility to backstage forces from interest groups or individuals competing within the organization. Moreover, another change of PMS may also lead to a violation of interests in the organization’s structure and claims via subsequent groups. Employees, however, may exert an implicit impact on management decisions by manipulating knowledge they share by way of the feedback and strategic learning process. As a result, they do not necessarily need to lie, they need only selectively share knowledge.

Decreased level of relational trust in managers has been shown to mean that employees do not strive to achieve assigned objectives. As long as rewards exceed incurred efforts, however, employee trust within the organization has been shown to fulfil its obligations and achieve its goals (Long and Sitkin 2006 ). Long and Sitkin’s ( 2006 ) research is analogous with this study and confirms that a strategy formation process after PMS implementation can encourage open questioning of superiors’ decisions—revealing: interest incongruence, lead to the emergence of conflicts, and raise manager suspicion (i.e., rejecting employee claims by which subordinates may undertake opportunistic action). At length, this consciousness contributes to the decline of manager trust in their subordinates. Hence, from the above analysis, it could be inferred that the implementation of PMS may affect knowledge sharing behavior as well as the whole feedback and strategic learning process (Fig. 2 ), which influence strategy formation.

3.6 Knowledge sharing

To gain a competitive advantage, the strategy development process (i.e., including functional strategies such as operations strategy) must be based on recent knowledge, encompassing the broadest group of stakeholders (Jarzabkowski and Balogun 2009 ; Mintzberg 1994 ; Schaefer and Guenther 2016 ; Spee and Jarzabkowski 2011 ), and functional strategies that should be developed within the guidelines of the overall business strategy (Kremer 2019 ). People are willing to share their knowledge, even unfavorable to their interests, when they trust each other (Dirks 2006 ; McKnight and Chervany 2006 ). Thus, the level of trust determines the knowledge sharing behavior. For this study, two types of trust in managers have been identified: relational and calculative. The level of relational trust may determine the genuineness of the knowledge (i.e., the tendency to share knowledge, including unfavorable knowledge against one’s actual interest) (Krishnan et al. 2016 ; Lado et al. 2008 ). Calculative trust may also motivate people to share knowledge, but mainly if it is favorable (Claro and Claro 2008 ; Poppo et al. 2016 ; Williamson 1993 ). To affect knowledge, it is sufficient that organizational actors, sometimes even unconsciously, interpret their environment (i.e., surrounding reality) in the context of their interests. They do not have to lie, as stated by Foucault ( 2019 ), since an understanding and interpretation of the same truth by different people, and even by the same people in a different situation, can be different (Willcocks 2004 ). In addition, knowledge transfer, which stands in contrast with manager assumptions, may affect the assessment of such an employee by inhibiting the realization of organizational strategy. Therefore, the transfer of knowledge maybe incompatible with current parameters of PMS and requires a high level of relational trust in superiors that have nonconformist behavior so not to adversely affect the subordinate.

Taking into account different levels of relational and calculative trust in managers, distortions of knowledge might be predicted (Fig. 3 ). There may be four possibilities. In the case of the low-level relational trust, employees are not willing to share genuine knowledge because they might be afraid that this may lead to organizational change violating the status quo. It may also bring the risk of deterioration of their situation by way of employees not trusting superiors to take care of them. Low-level calculative trust would imply employees do not believe that managers will reward their effort. Acquisition of valuable knowledge about an organization and its environment as well as sharing knowledge requires intentional exertion. Thus, in a situation where there are low-levels of both relational and calculative trust employees might not share their knowledge. In the case of a low-level relational trust and high-level calculative trust, knowledge might be distorted by a structure of interest in the organization. Employees would have the motivation to exhibit this knowledge which would be beneficial to them and, due to the weak relational trust, there would be a diminishing level of trust, i.e., even though it would be genuine. In a situation of a high-level of relational trust and low-level of calculative trust in managers, knowledge might be the most “genuine” due to employees not being afraid of imposing their particular narrative. They would be neither lured by incentive nor discouraged by fear of losing their interests.

Impact of relational and calculative trust on knowledge sharing behavior

An ambiguous situation occurs when there are simultaneously high-levels of relational and calculative trust. Both types of trust motivate people to share knowledge, but it is problematic to predict the extent to which transferred knowledge may be affected by personal interests. In this environment, employees may take two types of actions concerning knowledge sharing. Having a high-level of relational trust, they can openly share their knowledge, believing that the possible change would not worsen their situation, i.e., because managers would look after their interests. But, having a high level of calculative trust they may also succumb to “short-term temptations to grab the golden opportunity or cut corners” (Six and Sorge 2008 ) and try to gain more by sharing knowledge in a way favorable to their actual interests. It is likely, however, that different people could behave differently and, consequently, knowledge could be mixed. In this situation, however, a discussion between employees could arise that would reveal several arguments which would help managers recognize which knowledge is genuine. It is essential to notice that in none of the four instances, knowledge is purely genuine or distorted, it is always a matter of probability and proportions.

3.7 Use of shared knowledge

Employees who possess unique knowledge might gain considerable power in an organization. In the case of data or information, manipulation may be verified and forgery discovered. However, knowledge defined as a personal interpretation of reality, in the light of individual experience, by its very nature cannot be easily verified. Thus, even if shared knowledge is firmly focused on securing employee interests, the discovery of the distortion is challenging. For instance, suppose the board performed an action based on employee knowledge. After some time, it might be known that this action has not brought expected results, however, to prove employee intentional manipulation is highly unlikely. Undoubtedly, if in the next few situations poor outcomes repeat, managers may lose trust in their employee capability, but they would not be certain whether the failure was due to intentional manipulation or lack of competence. In a turbulent environment, it is likely there would be even no possibility to verify whether taking different actions would be more effective. This means that managers having virtually no objective grounds, enabling them to verify received knowledge and only relying on trust in employees, may determine the extent to which they would benefit from acquired knowledge (Long and Sitkin 2006 ; Spreitzer and Mishra 1999 ). Taking into account the four configurations of relational and calculative trust in managers and the level of manager trust in employees benefits from shared knowledge can be predicted.

Organizations may achieve the greatest benefits from shared knowledge when two conditions are met simultaneously, i.e., when the knowledge is genuine and superiors trust their employees. This may encourage managers to apply, in practice, the acquired knowledge and exploit opportunities by making quick and bold strategic decisions based on actual and comprehensive knowledge. From Table 3 it appears that this would happen in two cases—when there is a high-level of relational trust and low-level of calculative trust and when there are high-levels of both types of trust. However, the second situation is ambiguous since it is more complicated to predict to what extent the knowledge is distorted. Moreover, managers might not be inclined to formulate a strategy based on subordinate knowledge if they do not trust in their employees’ willingness to reveal knowledge impartially and honestly. In this case, they would wait for a confirmation of the genuineness of the knowledge through their observations or other sources, or they would select strategic options inconsistently—pending actual trends—even though shared knowledge was available and genuine. Irrespective, the decision would force delay or error, which could significantly reduce the chance of formulating an effective strategy and opportunities may be lost.