Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research

- Norman K. Denzin - University of Illinois, Urbana - Champaign, USA

- Yvonna S. Lincoln - Texas A&M University, USA

- Description

| ISBN: 9781483349800 | Hardcover | Suggested Retail Price: $160.00 | Bookstore Price: $128.00 |

| ISBN: 9781506365442 | Electronic Version | Suggested Retail Price: $128.00 | Bookstore Price: $102.40 |

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

- New contributors offer 19 completely new chapter topics , including indigenous methodologies, methodologies in an age of new technologies, queer/quare theory, ethnodrama, data and its problematics, triangulation, collaborative inquiry, digital ethnography, the global audit culture, and much more.

- Substantial revisions from returning authors provide reinvigorated content resulting in very different chapters.

- Content on a wide range of key topics, diverse perspectives, and current controversies derived from members of an international and interdisciplinary editorial board ensure the timeliest revision.

- Six classic chapters cover topics from paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, to performance ethnography, writing as a method of inquiry, strategies for composition, and creating narratives and research reports.

- Contributions from well-known international scholars allow readers to study the differences in approach among European, Australian, and American practitioners and theoreticians, as well as to hear the voices of non-Western authors.

- Coverage of state-of-the-art t opics include critical social science, critical pedagogy, mixed methods, narrative inquiry, qualitative research and technology, online ethnography, oral history, human rights, disability communities, queer theory, and performance ethnography.

- Discussions on a wide range of methods expand the reader's repertoire of methodologies, enlarging the range of data that can be brought to bear on social and educational issues.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Select a purchasing option.

Shipped Options:

BUNDLE: Denzin: The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research 5E + Plano Clark: Mixed Methods Research

Related Products

Qualitative Research: An Overview

- First Online: 24 April 2019

Cite this chapter

- Yanto Chandra 3 &

- Liang Shang 4

4019 Accesses

5 Citations

Qualitative research is one of the most commonly used types of research and methodology in the social sciences. Unfortunately, qualitative research is commonly misunderstood. In this chapter, we describe and explain the misconceptions surrounding qualitative research enterprise, why researchers need to care about when using qualitative research, the characteristics of qualitative research, and review the paradigms in qualitative research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Qualitative research is defined as the practice used to study things –– individuals and organizations and their reasons, opinions, and motivations, beliefs in their natural settings. It involves an observer (a researcher) who is located in the field , who transforms the world into a series of representations such as fieldnotes, interviews, conversations, photographs, recordings and memos (Denzin and Lincoln 2011 ). Many researchers employ qualitative research for exploratory purpose while others use it for ‘quasi’ theory testing approach. Qualitative research is a broad umbrella of research methodologies that encompasses grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 2017 ; Strauss and Corbin 1990 ), case study (Flyvbjerg 2006 ; Yin 2003 ), phenomenology (Sanders 1982 ), discourse analysis (Fairclough 2003 ; Wodak and Meyer 2009 ), ethnography (Geertz 1973 ; Garfinkel 1967 ), and netnography (Kozinets 2002 ), among others. Qualitative research is often synonymous with ‘case study research’ because ‘case study’ primarily uses (but not always) qualitative data.

The quality standards or evaluation criteria of qualitative research comprises: (1) credibility (that a researcher can provide confidence in his/her findings), (2) transferability (that results are more plausible when transported to a highly similar contexts), (3) dependability (that errors have been minimized, proper documentation is provided), and (4) confirmability (that conclusions are internally consistent and supported by data) (see Lincoln and Guba 1985 ).

We classify research into a continuum of theory building — > theory elaboration — > theory testing . Theory building is also known as theory exploration. Theory elaboration refers to the use of qualitative data and a method to seek “confirmation” of the relationships among variables or processes or mechanisms of a social reality (Bartunek and Rynes 2015 ).

In the context of qualitative research, theory/ies usually refer(s) to conceptual model(s) or framework(s) that explain the relationships among a set of variables or processes that explain a social phenomenon. Theory or theories could also refer to general ideas or frameworks (e.g., institutional theory, emancipation theory, or identity theory) that are reviewed as background knowledge prior to the commencement of a qualitative research project.

For example, a qualitative research can ask the following question: “How can institutional change succeed in social contexts that are dominated by organized crime?” (Vaccaro and Palazzo 2015 ).

We have witnessed numerous cases in which committed positivist methodologists were asked to review qualitative papers, and they used a survey approach to assess the quality of an interpretivist work. This reviewers’ fallacy is dangerous and hampers the progress of a field of research. Editors must be cognizant of such fallacy and avoid it.

A social enterprises (SE) is an organization that combines social welfare and commercial logics (Doherty et al. 2014 ), or that uses business principles to address social problems (Mair and Marti 2006 ); thus, qualitative research that reports that ‘social impact’ is important for SEs is too descriptive and, arguably, tautological. It is not uncommon to see authors submitting purely descriptive papers to scholarly journals.

Some qualitative researchers have conducted qualitative work using primarily a checklist (ticking the boxes) to show the presence or absence of variables, as if it were a survey-based study. This is utterly inappropriate for a qualitative work. A qualitative work needs to show the richness and depth of qualitative findings. Nevertheless, it is acceptable to use such checklists as supplementary data if a study involves too many informants or variables of interest, or the data is too complex due to its longitudinal nature (e.g., a study that involves 15 cases observed and involving 59 interviews with 33 informants within a 7-year fieldwork used an excel sheet to tabulate the number of events that occurred as supplementary data to the main analysis; see Chandra 2017a , b ).

As mentioned earlier, there are different types of qualitative research. Thus, a qualitative researcher will customize the data collection process to fit the type of research being conducted. For example, for researchers using ethnography, the primary data will be in the form of photos and/or videos and interviews; for those using netnography, the primary data will be internet-based textual data. Interview data is perhaps the most common type of data used across all types of qualitative research designs and is often synonymous with qualitative research.

The purpose of qualitative research is to provide an explanation , not merely a description and certainly not a prediction (which is the realm of quantitative research). However, description is needed to illustrate qualitative data collected, and usually researchers describe their qualitative data by inserting a number of important “informant quotes” in the body of a qualitative research report.

We advise qualitative researchers to adhere to one approach to avoid any epistemological and ontological mismatch that may arise among different camps in qualitative research. For instance, mixing a positivist with a constructivist approach in qualitative research frequently leads to unnecessary criticism and even rejection from journal editors and reviewers; it shows a lack of methodological competence or awareness of one’s epistemological position.

Analytical generalization is not generalization to some defined population that has been sampled, but to a “theory” of the phenomenon being studied, a theory that may have much wider applicability than the particular case studied (Yin 2003 ).

There are different types of contributions. Typically, a researcher is expected to clearly articulate the theoretical contributions for a qualitative work submitted to a scholarly journal. Other types of contributions are practical (or managerial ), common for business/management journals, and policy , common for policy related journals.

There is ongoing debate on whether a template for qualitative research is desirable or necessary, with one camp of scholars (the pluralistic critical realists) that advocates a pluralistic approaches to qualitative research (“qualitative research should not follow a particular template or be prescriptive in its process”) and the other camps are advocating for some form of consensus via the use of particular approaches (e.g., the Eisenhardt or Gioia Approach, etc.). However, as shown in Table 1.1 , even the pluralistic critical realism in itself is a template and advocates an alternative form of consensus through the use of diverse and pluralistic approaches in doing qualitative research.

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Constructing mystery: Empirical matters in theory development. Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1265–1281.

Article Google Scholar

Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. L. (2015). Qualitative research: It just keeps getting more interesting! In Handbook of qualitative organizational research (pp. 41–55). New York: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Brinkmann, S. (2018). Philosophies of qualitative research . New York: Oxford University Press.

Bucher, S., & Langley, A. (2016). The interplay of reflective and experimental spaces in interrupting and reorienting routine dynamics. Organization Science, 27 (3), 594–613.

Chandra, Y. (2017a). A time-based process model of international entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Journal of International Business Studies, 48 (4), 423–451.

Chandra, Y. (2017b). Social entrepreneurship as emancipatory work. Journal of Business Venturing, 32 (6), 657–673.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49 (2), 173–208.

Cornelissen, J. P. (2017). Preserving theoretical divergence in management research: Why the explanatory potential of qualitative research should be harnessed rather than suppressed. Journal of Management Studies, 54 (3), 368–383.

Denis, J. L., Lamothe, L., & Langley, A. (2001). The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 44 (4), 809–837.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). Introduction. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16 (4), 417–436.

Dubé, L., & Paré, G. (2003). Rigor in information systems positivist case research: Current practices, trends, and recommendations. MIS Quarterly, 27 (4), 597–636.

Easton, G. (2010). Critical realism in case study research. Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (1), 118–128.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989a). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 532–550.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989b). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32 (3), 543–576.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research . Abingdon: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

Friese, S. (2011). Using ATLAS.ti for analyzing the financial crisis data [67 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 12 (1), Art. 39. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1101397

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology . Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Geertz, C. (1973). Interpretation of cultures . New York: Basic Books.

Gehman, J., Glaser, V. L., Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D., Langley, A., & Corley, K. G. (2017). Finding theory–method fit: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27 , 284–300. in press.

Gioia, D. A. (1992). Pinto fires and personal ethics: A script analysis of missed opportunities. Journal of Business Ethics, 11 (5–6), 379–389.

Gioia, D. A. (2007). Individual epistemology – Interpretive wisdom. In E. H. Kessler & J. R. Bailey (Eds.), The handbook of organizational and managerial wisdom (pp. 277–294). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Gioia, D. (2019). If I had a magic wand: Reflections on developing a systematic approach to qualitative research. In B. Boyd, R. Crook, J. Le, & A. Smith (Eds.), Research methodology in strategy and management . https://books.emeraldinsight.com/page/detail/Standing-on-the-Shoulders-of-Giants/?k=9781787563360

Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12 (6), 433–448.

Gioia, D. A., Price, K. N., Hamilton, A. L., & Thomas, J. B. (2010). Forging an identity: An insider-outsider study of processes involved in the formation of organizational identity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 55 (1), 1–46.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16 (1), 15–31.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . New York: Routledge.

Graebner, M. E., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2004). The seller’s side of the story: Acquisition as courtship and governance as syndicate in entrepreneurial firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49 (3), 366–403.

Grayson, K., & Shulman, D. (2000). Indexicality and the verification function of irreplaceable possessions: A semiotic analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (1), 17–30.

Hunt, S. D. (1991). Positivism and paradigm dominance in consumer research: Toward critical pluralism and rapprochement. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (1), 32–44.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research, 39 (1), 61–72.

Langley, A. (1988). The roles of formal strategic planning. Long Range Planning, 21 (3), 40–50.

Langley, A., & Abdallah, C. (2011). Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. In Building methodological bridges (pp. 201–235). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Langley, A., Golden-Biddle, K., Reay, T., Denis, J. L., Hébert, Y., Lamothe, L., & Gervais, J. (2012). Identity struggles in merging organizations: Renegotiating the sameness–difference dialectic. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 48 (2), 135–167.

Langley, A. N. N., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & Van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56 (1), 1–13.

Lin, A. C. (1998). Bridging positivist and interpretivist approaches to qualitative methods. Policy Studies Journal, 26 (1), 162–180.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . Beverly Hills: Sage.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41 (1), 36–44.

Nag, R., Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2007). The intersection of organizational identity, knowledge, and practice: Attempting strategic change via knowledge grafting. Academy of Management Journal, 50 (4), 821–847.

Ozcan, P., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2009). Origin of alliance portfolios: Entrepreneurs, network strategies, and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (2), 246–279.

Prasad, P. (2018). Crafting qualitative research: Beyond positivist traditions . New York: Taylor & Francis.

Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (5), 856–862.

Ramoglou, S., & Tsang, E. W. (2016). A realist perspective of entrepreneurship: Opportunities as propensities. Academy of Management Review, 41 (3), 410–434.

Sanders, P. (1982). Phenomenology: A new way of viewing organizational research. Academy of Management Review, 7 (3), 353–360.

Sobh, R., & Perry, C. (2006). Research design and data analysis in realism research. European Journal of Marketing, 40 (11/12), 1194–1209.

Stake, R. E. (2010). Qualitative research: Studying how things work . New York: Guilford Press.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Vaccaro, A., & Palazzo, G. (2015). Values against violence: Institutional change in societies dominated by organized crime. Academy of Management Journal, 58 (4), 1075–1101.

Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 516–531.

Welch, C. L., Welch, D. E., & Hewerdine, L. (2008). Gender and export behaviour: Evidence from women-owned enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 83 (1), 113–126.

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42 (5), 740–762.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (Eds.). (2009). Methods for critical discourse analysis . London: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (1981). Life histories of innovations: How new practices become routinized. Public Administration Review, 41 , 21–28.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Young, R. A., & Collin, A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in the career field. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64 (3), 373–388.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Yanto Chandra

City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Liang Shang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Chandra, Y., Shang, L. (2019). Qualitative Research: An Overview. In: Qualitative Research Using R: A Systematic Approach. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3170-1_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3170-1_1

Published : 24 April 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-3169-5

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-3170-1

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Getting Started

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: May 23, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

745k Accesses

312 Citations

84 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

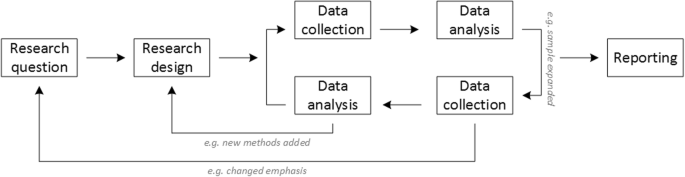

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

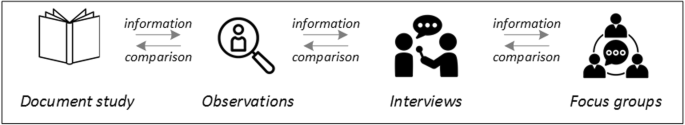

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

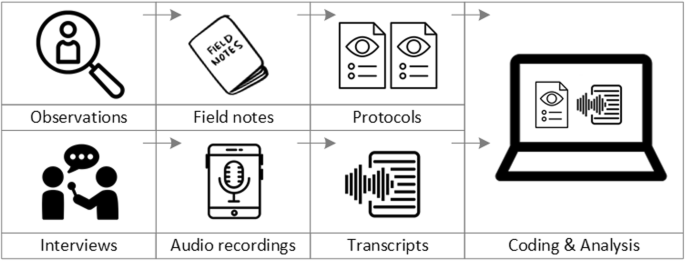

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

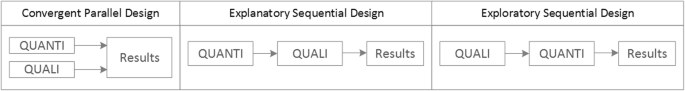

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions