If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Art of Asia

Course: art of asia > unit 4, introduction to japan.

- Buddhism in Japan

- Zen Buddhism

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

- A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

- Japanese art: the formats of two-dimensional works

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

A beginner’s guide to the art of Japan

Gain an birds-eye view of the arts of Japan.

prehistory - present

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

By Dr. Sonia Coman

Learn about Japan's famous haniwa, tales from behind palace walls, and enormous wooden buddhas.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

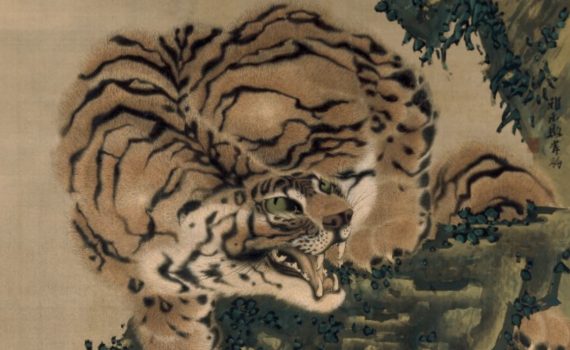

Learn about tea-ceremonies, opulent palaces, and splashed-ink paintings from Japan's Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

Learn about floating worlds and the art of the literati from Japan's Edo period.

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

Learn about Japan's modern cityscapes, art in a time of peace, and the dawn of a new era.

Japanese art: the formats of two-dimensional works

By The British Museum

From printed books and fan paintings to screens and sliding doors, two-dimensional art took many forms in Japan.

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Early Modern Japanese Art History-An Overview of the State of the Field

2002, Early Modern Japan: An Interdisciplinary …

Related Papers

patricia graham

This is an alternate version of the bibliography published in the journal EARLY MODERN JAPAN (fall 2002), arranged chronologically within categories.

John G . Henley

This is a continuation of my paper on the influence/influencing of Japanese arts associated with Japanism, Arts and Crafts and most importantly Art Nouveau

JOURNAL OF ASIAN HUMANITIES AT KYUSHU UNIVERSITY volume 7

Cynthea Bogel

DOI numbers may be found for individual articles and items on the Kyushu University Library here: https://www.lib.kyushu-u.ac.jp/publications_kyushu/jahq USE NOTICE OF CORRECTIONS (Errata sheet) for final item (report) by Mertz, et. al. and one correction for first article by Imazato. TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 7, SPRING 2022 SATOSHI IMAZATO Inter-Changeable Religions: A Style of Japanese Religious Pluralism in Hirado Island Villages, Northwestern Kyushu . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 AKIKO WALLEY The Power of Concealment: Tōdaiji Objects and the Effects of Their Burial in an Early Japanese Devotional Context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23 AKIKO HIRAI Structural Analysis of the Dance Within the Odaidai Ceremony of Kawaguchi Asama Shrine: Choreography, Music, and Meaning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47 MEW LINGJUN JIANG A Short Visual History of Abstraction in Early Modern Japanese Karuta: Simplification, Reinterpretation, and Localization . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61 Report Kyushu, Asia, and Beyond YOSHINORI IWASAKI TRANSLATED BY KAZUHIRO MURAYAMA Book Collecting by a Literati Daimyo in Early Modern Japan, and the Exchange of Information: An Investigation into Catalogues of the Rakusaidō Collection in Hirado Domain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85 Reviews Kyushu and the World, on the Fiftieth Anniversary of International Awareness of Minamata Disease MULTIPLE BOOK REVIEW BY TIMOTHY S. GEORGE W. Eugene Smith and Aileen Mioko Smith. Minamata (in Japanese). Trans. Nakao Hajime 中尾ハジメ. With contributions by Ishikawa Takeshi 石川武志, Yamagami Tetsujirō 山上徹二郎, Saitō Yasushi 斉藤靖史, and Yorifuji Takashi 頼藤貴志. Crevis, 2021. Seán Michael Wilson (text) and Akiko Shimojima (illustrations). The Minamata Story: An EcoTragedy. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2021. . . . . . . . . . . 95 BOOK REVIEW BY MARILYN ROBERT Reiko Sudo. NUNO: Visionary Japanese Textiles. Edited by Naomi Pollock. London: Thames & Hudson, 2021. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103 BOOK REVIEW BY MARIA CĂRBUNE Eduard Klopfenstein, ed. Sprachlich-literarische ‘Aggregatzustände’ im Japanischen: Europäische Japan- Diskurse 1998–2018. Berlin: BeBra Wissenschaft Verlag, 2020. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107 BOOK REVIEW BY MALLY STELMASZYK Laurel Kendall. Mediums and Magical Things: Statues, Paintings, and Masks in Asian Places. University of California Press, 2021. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119 BOOK REVIEW BY SUSAN NAQUIN Alain Arrault. A History of Cultic Images in China: The Domestic Statuary of Hunan. Translated by Lina Verchery. The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2020. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123 Research Report MECHTILD MERTZ, SUYAKO TAZURU, SHIRŌ ITŌ, AND CYNTHEA J. BOGEL A Group of Twelfth-Century Japanese Kami Statues and Considerations of Material Intentionality: Collaborative Research Among Wood Scientists and Art Historians . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127 Notice of Corrections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

Mutual Images Research Association

The Legacy of Japanese Artistic Influence on Art Nouveau - The Tides of Change

In order to appreciate the continental, cultural and stylistic interrelationships between Japanese, European and North American, I would that I had to go back in history to fully understand how porcelains and related artworks, especially Chinese, Japanese and then British and continental European, influenced each other. It was much more difficult to fully comprehend the transition of Japanese artworks in the western style through Art Nouveau and into Art Deco than I would have imagined.

The Heinz Kaempfer Fund and the International Institute for Asian Studies are proud to present the first seminar of a biennial series of seminars on Japanese art. With the New Perspectives series we aim to demonstrate that the study of Japanese art is very much alive and part of a global discussion. We especially invite students and (young) scholars to participate in this event!

The Art Bulletin

Matthew McKelway

The Journal of Asian Studies

Joan Stanley-Baker

Asian Theatre Journal

Julie Iezzi

RELATED PAPERS

Ekspetasi Genius

Jasa buat Jendela aluminium

Jesús Ramírez Ortega

Qubahan Academic Journal

Subhi R M Zeebaree

Phytotherapy Research

Jadwiga Renata Ochocka

Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics

Piotr Nowak-Przygodzki

International Journal of Dairy Technology

Luciana Vera Candioti

Russian Journal of Genetics

Alexander Gnutikov

arXiv: Materials Science

Sasan Nouranian

Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy

Helio Sader

Toshiro Tanimoto

Journal of Infection and Public Health

Ebrahim Mahmoud

Caterina Pentericci

Munibe Monographs

nagore zaldua-mendizabal

Sakinah putri Azria Azis

PERCEPTIONS: Journal of International Affairs

Sujata Ashwarya

Journal of the Neurological Sciences

Marina Zafranskaya

El ms. Holkham misc. 46 de la Bodleian, testimonio del Fuero Juzgo: notas para su estudio y propuesta de edición parcial

Ángeles Romero Cambrón

hjhfggf hjgfdf

Brain Stimulation

Eman M Khedr

Technical Innovations & Patient Support in Radiation Oncology

Maarten Dirkx

International relations and diplomacy

Dibyajit Mukherjee

The EMBO Journal

bernard Mouillac

Acta Crystallographica Section E-structure Reports Online

Vinutha V Salian

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Upheaval and Experimental Change:

Japanese art from 1945 to the end of the 1970s, by hajime nariai curator, tokyo station gallery and adjunct professor at joshibi university of art and design, tokyo.

In the summer of 2015, the phrase “the 70th year of the postwar era” appeared in all the Japanese newspapers. I wonder if there are any other nations that have been burdened with the term “postwar” for such a long time, in our case continuously since the end of World War II. According to Eiji Oguma, one of Japan’s most noted sociologists, “postwar” is not a term of periodization rather its meaning, in Japan, is equivalent to “nation-building.” Indeed, the summer of 1945 saw the national structure of our country redesigned from the ground up.

It could be said that the first thirty years of “the history of Japanese postwar art,” which I will quickly survey in this essay, is a trajectory of very fresh artistic activities in a newly born (or re-born) country. During this period, Japan raced along at a high speed, beginning from a jump-start to a fast acceleration and then proceeding at a steady rate. The 1950s witnessed a new society arise from vast areas of scorched ground, the 1960s an era when Japan become an economic power through its incredible growth, and, in the 1970s, a maturation period, with the arrival of a fully developed consumer and information-based society.

Along with this, Japan’s art underwent drastic changes and shifts. Emerging from the deeply engraved mark of 1945 as the beginning of the “contemporary”, artworks made during this period possess an enduring rawness and vitality, making them feel contemporary even today, decades after their creation.

In the first half of the “postwar” period, Japanese artistic practice grew with drastic changes, winding through new styles and bold gestures of experimentation. As a body undergoing intense growth spurts in a short period of time, these initial decades were characterized by unexpected twists and strains, aimed at destabilizing many previous and established conventions of art making and Japanese aesthetics. Japanese society, and its artists, grappled with the conflicting experiences of liberation from the Imperial and intensely nationalistic governance and, at the same time, intense reactions towards Americanization and the occupation that characterized these initial decades after the war ended. What is surprising is that the identity of Japanese contemporary art remains elusive and shaky, despite these seminal forerunners’ pursuits. At present, we in Japan are still formalizing a fully authorized Japanese postwar art history and confronting our own contemporary art.

1945 to the 1950s: Wound or Reset

Sur-documentalism and avant-garde.

After the Allied occupation from 1945, Japan finally recovered its sovereignty through the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1952. Two main types of artists pioneered new directions in this highly-charged period: those who viewed Japan s defeat as a wound and those who approached it as a reset.

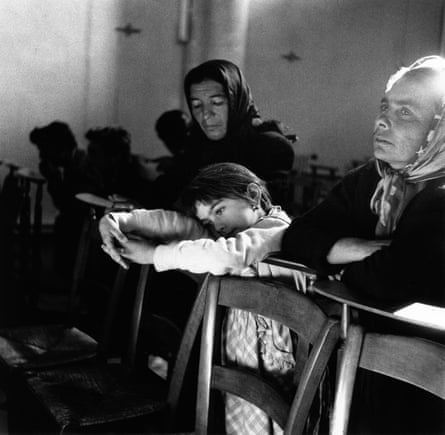

Sur-documentalism, advocated by the writer and critic Kiyoteru Hanada as a new type of realism, applied aesthetics associated with Surrealism to paintings, shedding light on social injustices and revealing deeper layers of reality. Also known as its alias, “Reportage Paintings”, works by artists of this movement (Tatsuo Ikeda, Kikuji Yamashita, etc.) portrayed oppressed people and controversial incidents as caricature, based on their first-hand investigation of the dark sides of society.

In contrast, the avant-garde artists initiated artistic innovation through their unconventional methodologies. As inheritors of the pre-war generation of avant-garde painters, such as Yoshishige Saito and Takeo Yamaguchi who established the group Kyushitsukai (Ninth Room Association), these artists would form the mainstream of the early postwar Japanese art history; the groups Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) in Tokyo and Gutai in Osaka. Formed around the critic Shuzo Takiguchi in 1951, Jikken Kobo was composed of members who were as curious as laboratory workers about experimentation, engaging in cutting-edge, all-encompassing, works of art, by incorporating industrial technologies, music, theater and different media. Gutai, formed in 1954, was different.

Responding to the proposition, “Do what no one has ever done before,” the favored dictum of its leader and chief proponent, Jiro Yoshihara, Gutai s members invented radical ways of art making, such as painting with feet (Kazuo Shiraga) or calling an electric circuit a painting (Atsuko Tanaka). Yoshihara himself had been a member of Kyushitsukai (Ninth Room Association) and also made Surrealistic paintings and calligraphically-based abstractions. Inviting the formless such as bodily actions and fluid materials to the notion of painting, Gutai works were described by Allan Kaprow as a precursor of Happenings, and positioned by Michel Tapi as a representative of Art Informel. It is possible to view Gutai paintings as works emancipated from all restraints associated with modern art, and with a kinship to their contemporaries such as Jackson Pollock and Robert Rauschenberg.

I wonder if there are any other nations that have been burdened with the term “postwar” for such a long time.

1960s: Art Informel Sensation and Revelry

The escalation of anti-art.

Art Informel, a French term describing various styles of abstract painting that were gestural during the 1940s and 1950s, was associated with Gutai and possessed strong ties with Japan. Prior to the founding of Gutai, Japanese painters including Toshimitsu Ima , Hisao Domoto and Kumi Sugai, were already associated with this movement in France and its creative resonance, as well as its break from tradition in modernism, was distinctively felt in Japan.

Introduced into Japan in the late 1950s, Art Informel advocated the materiality of paints and the act of painting itself and instigated the production of anarchistic works oozing intense emotions amongst the younger artists. The Yomiuri Independent, an annual, unjuried and non-competitive exhibition, became their platform, filled with odd, almost garbage-like works combined with movement and sound, often made of discarded everyday items and obsolete materials. Continuing until 1963, this annual exhibition produced many young stars, such as Ushio Shinohara, Tetsumi Kudo and Hi-Red Center, and ended when the self-destructive craze by radical artists, so-called “Anti-Art,” reached its peak in the early 1960s.

Anti-Art emerged as part of the globally erupting counterculture. Not only art, but also culture in general in Japan, saw an explosion of often brutal, savage or wild body performances as well as archaic and more traditional visuals. It was resistance against modernity, propelled by the complication of people’s mixed feelings: they loved and hated the postwar modernization, because what it actually meant to them was nothing short of full scale Americanization. Cultural icons of this period include Tatsumi Hijikata’s Butoh dance focusing on the Japanese body, Juro Kara’s and Shuji Terayama’s Angura (Underground) Theatre and the signature blurry photographs (are, bure, boke) by Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahara, as well as kitsch posters by Tadanori Yokoo. Even as the basic attitude of the artists was “anti-establishment,” this radical and festive mood was also intrinsically bound up with Japan’s elation, buoyed up by two enormous national events: the 1964 Summer Olympics (Tokyo) and Expo ’70 (Osaka).

1970s: The Calm after the Storm

The triumph of mono-ha.

After the revelry comes repose. The hot resistance, which characterized the 1960s, gradually shifted to cool-headed questionings. After each and every existing institution and value related to art was challenged, the next target set upon was the artist s intention. From this came a style of not making, later called Mono-ha. Artists who emerged in the late 1960s, such as Lee Ufan, who placed rocks on broken glass, and Kishio Suga, who, in a matter-of-fact way, leaned square pieces of timber against architecture, employed minimal materials and actions to explore primordial relationships with the world.

With Lee Ufan, well informed by both Eastern and Western philosophies, as its theoretical pillar, Mono-ha was not a group but a tendency of loosely interconnected artists, unintentionally coinciding with the contemporary ascetic practices such as Minimalism and Arte Povera. The ambiguity of the Japanese term mono, which covers various concepts such as objects, materials, things, and even situations, indicates their specific orientation. Staying away from articulate symbolization and objectification of the world, namely anthropocentrism, the Mono-Ha artists attempted to touch the intrinsic mystery of the world with no distinctions between objects and situations. Moreover, their practice of not making was interrelated with a new stream of conceptualism, in which works made solely of words emerged one after another, from artists like Jiro Takamatsu and Yutaka Matsuzawa. In stark contrast to the 1960s, art in the 1970s was nourished by such a style of rational contemplation.

At the same time, works using reproducible media blossomed, not only in the field of visual art but also in other genres such as anime, manga, illustration and graphic design, fueled by the growth of accessible technology such as video and in popular culture with the widespread availability of the TV and magazines. Such cultural activities, centered around consumer industries, functioned as an incubator for the genealogy of art after the 80s, in which glamour and flamboyance would be regained.

52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best japanese art topic ideas & essay examples, 🎓 good research topics about japanese art, 🥇 interesting topics to write about japanese art.

- The Complexity of Traditional Chinese and Japanese Theater Arts Comedic plays gained popularity since the start of the theater in 1603, but public outrage over the vulgarity and excess eroticism of kabuki led to the government prohibiting women from acting in the plays.

- Japanese Kimono: A Part of Cultural Heritage The other reason behind the waning popularity of the kimono is the intricate design used in its knitting. In the beginning of the 18th century, the name of this garment was changed to kimono. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Japanese Shrines Architecture Uniqueness They also concentrated much on the visual elegance and the actual balance of the building compared to the level of the environment.

- Effects of Globalization in the Contemporary Japanese Art They have in turn influenced the art of painting in Japan to develop it and push it to a global level.

- The Influence of Japanese Art Upon Mary Cassatt Critics admit that Japanese motifs are evident in her works especially in her entire work, devoted to the representation of woman and the child, which is a kind of revenge for repressed maternity: unmarried, she […]

- V. Horta’s Tassel Hotel and the Pavilion for Japanese Art by B. Goff The Art Nouveau works of art are characterized by the use of the new materials and technologies from one side and the motives of the ancient myths and spiritual world on the other.

- Mono-Ha. Japanese Art Style. Concepts and Impact on Cultural Trends These movements and styles developed as a result of a special vision of the world common for Japanese people who are known for their devotion and tender affection to nature and its beauty, and the […]

- Japanese Painters: Asai Chu and Hashimoto Hashimoto Sadhide a renowned Japanese painter born in 1807 and he died in 1878; the painter lived in the city of Yokohama which was known to be a western settlement.

- Traditional Japanese Architecture One of the major causes of the abovementioned twists has been the commencement of Buddhism in the country, which was greatly influenced by the socialism from China.”Beasley believes that “by the eleventh century the Chinese […]

- Women in Art: Yayoi Kusama, Maya Lin, Zaha Hadid In her autobiography, Kusama says that “deep in the mountains of Nagano,” where she was born in 1929, she had discovered her style of expression: “ink paintings featuring accumulations of tiny dots and pen drawings […]

- Yayoi Kusama’s Art and Oriental Way of Life Such a point of view is, of course, is fully legitimate – especially given the unconventional aesthetic subtleties of Kusama’s artistic installations, the long history of psychosis, on the author’s part, and the fact that […]

- Kimono Art in Traditional Japanese Clothing The Kimonos were introduced in the Japanese culture during the Heian period. The government of the time agitated for westernization, where the Japanese people were to adopt western culture including the western attire.

- Ancient Egyptian and Japanese Art: Comparative Analysis

- Art Criticism Using the Frames – Chinese and Japanese Art

- Ancient Japanese Art Artists Hiding Place

- Comparative Analysis of Chinese and Japanese Art

- Exploring the Unique Japanese Art

- Impressionist Artists and the Influence of Japanese Art

- Overview and Analysis of Japanese Art and Culture

- Japanese Art During the Asuka Period

- Kabuki, the Japanese Art vs. Puccini’s Madame Butterfly: Comparison

- Japanese Art Infused Into the Temple of Todaiji

- Overview and Analysis of Modern Japanese Art

- Japanese Art: Shinto vs. Buddhism

- Origami: The Japanese Art of Paper Folding

- Japanese Art: World War II and American Occupation

- The Great 19th Century Impressionists Influenced by Japanese Art

- Urawaza: The Japanese Art of Lifehacking

- The Effect of Culture and Mythology on Japanese Art

- Japanese Manga as an Art Form

- A Study of the Origin of Judo and Jujutsu, a Japanese Art

- An Overview of the Beauty Principle in Japanese Art

- The Most Collected and Popular Kind of Art, the Japanese Art

- The History of Japanese Art Before 1333

- Japanese Art: The Edo Period of the Japanese Culture

- Analysis of Western Influence on Japanese Art

- How Japanese Art Influenced Their Works of Art

- Effects of Japanese Art on French Art in the Late 19th Century

- The Link Between Japanese Art and Shintoism

- How Japanese Art Influenced Van Gogh’s Paintings

- Comparison of Non-western Art vs. Japanese Art

- Overview of the Japanese Art of Ukiyo-e

- Literature, Art, Sport, and Cuisine of Japanese Culture

- Contemporary Japanese Art: Between Globalization and Localization

- The Impact of the First World War on Japanese Art

- Japanese Art: The History of Pottery

- John la Farge’s Discovery of Japanese Art

- Japanese Art: History, Characteristics, and Facts

- Looking at the Most Famous Japanese Artists and Artworks

- From Japonisme to Japanese Art History: Promoting Japanese Art in Europe

- Overview of Major Themes in Japanese Art

- The Chinese Influence on Japanese Art

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, September 4). 52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/

"52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 4 Sept. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2022) '52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 4 September.

IvyPanda . 2022. "52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 4, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 4, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "52 Japanese Art Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 4, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/japanese-art-essay-topics/.

- Anime Questions

- Buddhism Topics

- Ceramics Titles

- Fashion Essay Titles

- Impressionism Research Ideas

- Artists Research Ideas

- Confucianism Titles

- Vincent van Gogh Research Ideas

- Contemporary Art Questions

- Fashion Design Topics

- Mayan Research Ideas

- Tea Research Topics

- Baroque Essay Topics

- Yoga Questions

- Invasive Species Titles

A Century of Japanese Photography : Historical Reckoning and the Birth of a New Movement

By kelly midori mccormick.

In the late 1960s, as demonstrators marched the streets of Tokyo in mass protest of the renewal of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty, two generations of photographers called for a public reckoning with the medium’s wartime responsibility. Collectively they invoked their colleague Yoshio Watanabe’s question, “What should a photographer be?” [1]

The resulting exhibition, Shashin 100 nen—Nihonjin ni yoru shashin hyogen no rekishiten (A Century of Japanese Photography), held in 1968 at the Seibu department store in Ikebukuro, Tokyo, was one of the most important photography shows of the twentieth century. [2] Analyzing one hundred years of work by Japanese photographers, it was the first presentation to reflect on their contributions to Japanese fascism during World War II. The accompanying book, when published in English in 1980, became the first major volume to introduce an international audience to Japanese contributions to the medium. The exhibition itself can be credited with bringing forward a new type of aesthetic: after looking through tens of thousands of pictures in their roles as curators of the exhibition, Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki founded the photography collective Provoke, whose are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) style continues to influence photographers around the world. [3]

The First Centralized Collection of Japanese Photographs

A Century of Japanese Photography displayed the results of the first archiving project to gather photographs and negatives from regional libraries, prominent families, and collectors located from the northern tip of Japan to its southernmost islands. The curators estimated that they collected more than one hundred thousand original prints and around thirty-five thousand reproductions in this unprecedented effort to evaluate existing public and private holdings of historic Japanese photographs. [4] The sheer volume of pictures gathered spurred the movement to build Japan’s first central photography museum and permanent archive of photographic materials, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. [5]

The exhibition was planned, curated, and executed by photographers hailing from a wide range of specializations, establishing them as archivists and theorists of work by their predecessors and contemporaries. The curatorial team was led by Shomei Tomatsu and included Nakahira, Taki, Hisae Imai, Masatoshi Naito, and Seiryu Inoue, among others, many of whom were affiliated with the Japan Professional Photographers Society (JPS). [6] The exhibition positioned the younger artists against their teachers in the first instance of public criticism of the work of the Japanese wartime generation, including photographers such as Ken Domon, Ihei Kimura, and Hiroshi Hamaya. [7]

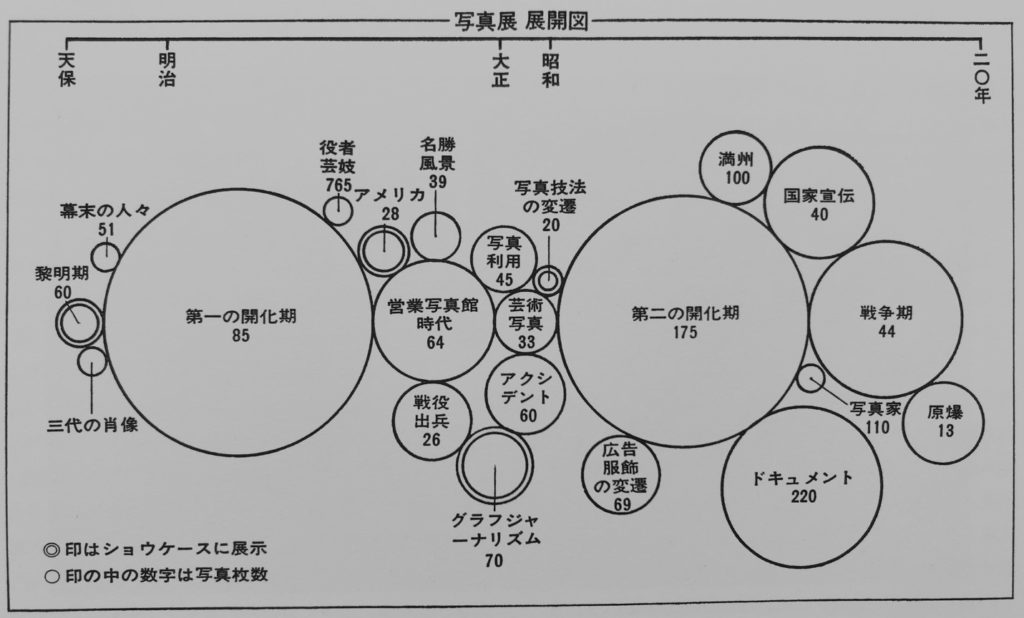

Preparation for the exhibition unfolded in two stages. [8] First, in the autumn of 1967, the curators gathered prints and negatives from local libraries and historical associations throughout Japan. These materials were sent back to the curatorial team’s office in Ginza, Tokyo, where they also stored thousands of books borrowed from the FujiFilm and Iwanami Shoten photography libraries for reference. Second, under Tomatsu’s direction, the team selected 1,640 pictures from the larger set, grouping the images into sections by their shashin hyogen (photographic style) (see figure 1). They met over a two-day period in April 1968 at an inn in Tsukiji, Tokyo, to organize the groupings, which included “Period of the First Enlightenment,” highlighting photography of the 1860s and 1880s; “Commercial Photography Studios,” focused on studios that were active from the 1870s to the 1920s; “Art Photography”; “Accidents”; “Changes in Fashion Advertising”; “National Propaganda”; “Manchuria,” featuring photographs of Japanese colonization of Manchuria; “Period of War”; and others. Each section established its own common visual vocabulary that centered on what Taki described as “the social consciousness [of the photographer] from the Meiji period to World War II.” [9]

Wartime Responsibility and Photographs as Reflections of the Real

The largest section, “The Document,” comprised anonymous pictures selected from magazine and newspaper archives, suggesting a new way of thinking about the connections between photographers and the scenes they sought to capture (see figure 2). [10] By filling the gallery with works by unknown authors that depicted specific historical events and places, the curators emphasized the importance of the content of the image. In contrast, the national propaganda works by well-known photographers such as Domon exemplified the use of the medium to create fictions in support of the war effort. Thus, the “National Propaganda” section with pictures pulled from mass-produced photography magazines such as Asahi Graph and Nippon demonstrated ways Japanese photographers had stopped trying to portray the real circumstances of life, instead presenting idealized fantasies to advertise the wartime Japanese imperial project (see figure 3). In the critic Tomomi Ito’s words, these were “photographs . . . taken from a position of great indifference to history.” [11]

Reflecting on the exhibition later, Tomatsu and many of the other curators concluded that the pictures on display were evidence of the collective failure of Japanese photographers to make images that analyzed historical events critically. Immediately following Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II, Japanese photographers—unlike Japanese painters and writers—did not engage in public self-criticism for colluding with the state and supporting the war effort. [12] In fact, those who had been the most active in producing propagandistic imagery, such as Domon and the photographer-editor Yonosuke Natori, continued in the postwar period to act as the gatekeepers for the photography world. [13] It was against these antecedents that Tomatsu, Nakahira, and Taki pushed back: in their view, these figures had used the visual techniques of the documentary photograph to present state lies to the Japanese public, calling the entire premise of the “document” into question.

For this reason, Taki and Nakahira became deeply invested in the meaning of the “document” and believed that challenging the very idea that photography could represent reality might set their work apart from that of the wartime generation. In their view, images of the colonial development of Japan’s northernmost island in the 1870s and 1880s by Kenzo Tamoto as well as pictures of the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki by the military photographer Yosuke Yamahata were the only true examples of photographic documentation in the exhibition. [14] Taki and Nakahira argued that in their historical contexts, both photographers had found ways to be so fully present in the making of their pictures that they connected directly with their subjects. [15] In the months following the exhibition, Nakahira and Taki were joined by Yutaka Takanashi, Takahiko Okada, and later Daido Moriyama in an effort to come up with a completely new system of representation, one that was theoretically informed and positioned to be a catalyst for social change. Though the collective, Provoke, was short-lived, the are-bure-boke style that characterized their work left its mark on the Japanese photography world, offering new techniques that prioritized accidental, mechanical qualities driven by the camera and the desire to obliterate the photographer.

Building on the slim catalogue that had accompanied A Century of Japanese Photography , Tomatsu, Taki, and Naito worked with the JPS to write A History of Japanese Photography 1840–1945 . At the time of its publication, in 1971, it was the most comprehensive history of Japanese photography written to date. Alongside 696 photographs that had been gathered for the exhibition, the book’s essays elaborate upon the original presentation’s critical premise. In 1980, Random House published an English translation of the volume with texts by historian John W. Dower, who would later be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for his research on postwar Japan in Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (1999). Dower has noted that in his introduction to the book he “wanted to make the point that it wasn’t just superb ‘photography’ that we encountered here, but beyond this a brilliant window on the incredibly diversified and complex social and cultural dynamics of modern Japan.” [16]

Thus what began as a movement to preserve the legacy of Japanese photographers turned into a public reckoning with their role during World War II and its aftermath. Precisely because they were looking at this history from a nationwide perspective, comparing the work across time and space as never before, photographers of the postwar generation developed a critique of the function of the photographer and established a theoretically informed method that challenged the boundaries of photographic representation itself. These negotiations both inspired a new movement within the medium and created the framework through which Japanese photography was first introduced to a global audience.

- Yoshio Watanabe, “‘Shashin 100 nen’ Nihonjin ni yoru shashin hyogen no rekishiten ni tsuite” (On “A Century of Japanese Photography”: A Historical Exhibition on Photographic Expression by the Japanese), Tokushugo shashin no hi koenkai (Special Edition Photography Day Lecture), Photographic Society of Japan Bulletin 7/8 (1968): 8. For more on the Japanese protests of the 1960s, see William Marotti, “Japan 1968: The Performance of Violence and the Theater of Protest,” American Historical Review 114, no. 1 (February 2009): 97–135.

- Though the Japanese title’s translation is closer to A Century of Photography: A Historical Exhibition of Photographic Expression by the Japanese , scholars have frequently simplified it to A Century of Japanese Photography , which I retain here.

- Tomomi Ito, Ichiro Murakami, Hiroshi Hamaya, Shomei Tomatsu, Koji Taki, Masatoshi Naito, Keiichi Kimura, Keisuke Kumakiri, and Norihiko Matsumoto, “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete” (The End of the “A Century of Japanese Photography” Exhibition), Nihon shashinka kyokai kaiho (Japan Professional Photographers Society Newsletter), no. 19 (1968): 10.

- Accounts of the number of photographs gathered vary. Watanabe, then president of the Japan Professional Photographers Society, claimed it was one hundred thousand, though Shomei Tomatsu later cited five hundred thousand. Watanabe, “‘Shashin 100 nen,’” 8; Shomei Tomatsu, Masatoshi Naito, Koji Taki, Hisae Imai, and Hirano Hisashi, “Shashin hyogen no rekishi wo kataru: Nihon shashinka kyokai shashin 100 nen ten ni tsuite” (Narrating a History of Photographic Expression: On the Japan Professional Photographers Society “A Century of Japanese Photography” Exhibition), Asahi Camera (June 1968): 222–28. See also Ito, Murakami, Hamaya, et al., “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete,” 24.

- The museum opened in 1990. Its English name was changed to the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (TOP Museum) in 2016.

- The Japan Professional Photographers Society (JPS) was established in 1950 to support the legal rights of commercial photographers and photojournalists. The Photographic Society of Japan (PSJ) was established in 1952 to promote Japanese photography and the use of photography as a means of connection between Japan and other countries. Most postwar photography exhibitions in Japan were produced by photography organizations such as the JPS and PSJ, camera clubs, and camera corporations at galleries and department stores. Though the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, held six photography exhibitions between 1953 and 1974, it held none between 1974 and 1994. See Julia Thomas, “Raw Photographs and Cooked History: Photography’s Ambiguous Place in the Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo,” East Asian History: The Continuation of “Papers on Far Eastern History ,” no. 12 (December 1996): 125–26.

- Imai was the sole woman involved. The exhibition was sponsored by the Nihon Shashinki Kogyokai (the Japan Camera Industry Association, JCIA) and the Shashin Kanko Zairyo Kogyokai (the Photo-Sensitized Materials Manufacturer’s Association). See Watanabe, “‘Shashin 100 nen,’” 8.

- For a detailed description of the exhibition’s planning, see Seiichi Tsuchiya, “Shashinshi 68 nen—‘shashin 100 nen’ saiko” (The History of Japanese Photography in 1968—Reconsidering “A Century of Japanese Photography”), Photographers’ Gallery Press , no. 8 (April 2009): 242–52. For an English translation of the abridged version, see Seiichi Tsuchiya, “The Whereabouts of the ‘Record’ Discovered—Reflections on A Century of Photography ,” in Nihon shashin no 1968: 1966–1974 futtosuru shashin no mure (1968—Japanese Photography: Photographs That Stirred Up Debate, 1966–1974), ed. Ryuichi Kaneko and Hiroko Tasaka (Tokyo: Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 2013), xiii–xxii.

- Ito, Murakami, Hamaya, et. al., “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete,” 24.

- The argument could be made that Nakahira drew on the “The Document” section display strategies for his photographic installation Circulation: Date, Place, Events at the 1971 Paris Biennale. See Franz Prichard, “On For a Language to Come, Circulation and Overflow : Takuma Nakahira and the Horizons of Radical Media Criticism in the Early 1970s,” in For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979 , ed. Yasufumi Nakamori and Allison Pappas, exh. cat. (Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2015), 84–89.

- Ito, Murakami, Hamaya, et al., “‘Shashin 100 nen’ ten wo oete,” 22.

- On debates over war responsibility in postwar literary circles, see J. Victor Koschmann, “The Debate on Subjectivity in Postwar Japan: Foundations of Modernism as a Political Critique,” Pacific Affairs 54, no. 4 (Winter 1981–82): 609–31. On postwar photography, see Justin Jesty, “The Realism Debate and the Politics of Modern Art in Early Postwar Japan,” Japan Forum 26, no. 4 (September 2014): 508–29.

- In the 1950s Domon made a name for himself as the father of Japanese realism, though he had been using a similar photojournalistic style to shoot propaganda photographs for Nippon and Shashin Shuho , state-sponsored periodicals that glorified Japanese imperialism. For more on Domon’s postwar articulations of his photographic theory, see Julia Adeney Thomas, “Power Made Visible: Photography and Postwar Japan’s Elusive Reality,” Journal of Asian Studies 67, no. 2 (May 2008): 365–94.

- For an insightful critique of Nakahira and Taki’s decontextualized adoration of Kenzo Tamoto, see Gyewon Kim, “Reframing ‘Hokkaido Photography’: Style, Politics, and Documentary Photography in 1960s Japan,” History of Photography 39, no. 4 (December 2015): 348–65.

- See Philip Charrier, “Taki Koji, Provoke, and the Structuralist Turn in Japanese Image Theory, 1967–70,” History of Photography 41, no. 1 (April 2017): 25–43.

- Interview with the author, November 20, 2018.

cite as: Kelly Midori McCormick , “ A Century of Japanese Photography : Historical Reckoning and the Birth of a New Movement,” Focus on Japanese Photography , February 2022. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, https://www.sfmoma.org/essay/a-century-of-japanese-photography-historical-reckoning-and-the-birth-of-a-new-movement/

For an enhanced viewing experience, it is recommended you use a desktop.

Kelly Midori McCormick

Essays and artist talks, introduction, november 2017, sandra s. phillips, distant relations: japanese photography in american exhibitions in the 1970s, february 2022, exhibiting “the end of modern photography”: ten artists of contemporary japanese photography and fifteen photographers today, artist talk: personal landscapes, naoya hatakeyama, japan theater, october 2017, artist talk: about fukei, september 2017, artist talk: about my work, primary sources, selected primary source materials on photography in japan, 1950s–1980s.

As Japan shifted to a consumer economy after World War II, its large newspaper companies began producing mass-market photography magazines. Such publications were important vehicles for circulating and supporting the new kind of photography that was emerging at the time—work that evinced a unique, indigenous, and highly expressive style, an often-unacknowledged art form unto itself. Principal among these magazines were the monthly Camera Mainichi , supported by Mainichi Shimbun (Daily News), and Asahi Camera , supported by the Asahi company (now Asahi Shimbun Shuppan). Camera Mainichi and Asahi Camera printed not only new and distinctive work by the generation of Japanese photographers then coming to maturity, notably Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, and Eikoh Hosoe, but also pictures and critiques of pictures from Europe and the United States. Many pages were devoted to amateur work in the medium, with tips for taking better family photographs joining genuine criticism and discussions of major exhibitions and catalogues from overseas. There were also smaller, more personal magazines in circulation such as Miyako Ishiuchi and Asako Narahashi’s Main , which featured their work and experiences as experimental women photographers in Japan. This selection of articles and catalogue essays from the late 1950s through the 1980s exemplifies contemporary discourse about Japanese photography and its ties to the international photography community.

Miyako Ishiuchi

“dialogue: in search of another hand”, miyako ishiuchi and asako narahashi, “ways of seeing, ways of remembering: the photography of prewar japan”, a century of japanese photography, john w. dower, “i am a photographer of attack”, camera mainichi, shoji yamagishi.

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Art History — The History Of Japanese Art Before 1333

The History of Japanese Art before 1333

- Categories: Art History Japanese Art Japanese Culture

About this sample

Words: 993 |

Published: Feb 8, 2022

Words: 993 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 527 words

7 pages / 3208 words

5 pages / 2445 words

2 pages / 1118 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Art History

Mama's dream of owning a house represents her desire for stability, security, and a better future for her family. As an African American woman living in a segregated society, Mama has faced discrimination, poverty, and limited [...]

The Pact by Drs. Sampson Davis, George Jenkins, and Rameck Hunt is a powerful memoir that highlights the challenges faced by three young African American men growing up in a disadvantaged neighborhood in New Jersey. The book [...]

The Foundation of Knowledge Model is a framework that helps individuals understand how knowledge is acquired and how it can be used to inform decision-making and problem-solving. This essay will explore the history and debates [...]

The invention of the printing press in the Renaissance period was a pivotal moment in the history of communication and knowledge dissemination. Johannes Gutenberg's creation revolutionized the way information was shared, making [...]

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon evoke a romantic picture of lush greenery and colorful flowers cascading from the sky. The grandeur of their sight must have been awe-inspiring, the magnificence, what a sight to behold. Oh! If [...]

What is music? When looking for the definition of music you’ll stumble across a lot of different definitions, everyone has their own definition of what music is to them. A better question to ask probably would’ve been what is [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The origin of all things: Kyotographie 2024 – a photo essay

The 12 th annual Kyotographie photography festival features 13 exhibitions staged in striking locations across the Japanese city of Kyoto. Photographers from around the world submitted pictures on the theme of ‘source’

- The Kyotographie international photography festival runs until 12 May

S pring in Kyoto ushers in cherry blossom season, but it also marks the return of one of the biggest photo festivals in Asia. Kyotographie, now in its 12th year, fuses the past and present with its striking images and unique locations. The 13 exhibitions are staged in temples, galleries and traditional private homes across the Japanese city, showcasing the work of national and international photographers.

The festival is loosely centred on a theme – and this year the directors, Lucille Reyboz and Yusuke Nakanishi, asked participants to focus on the word “source” by delving into the essence of beginnings and the nexus of creation and discovery.

The Yamomami struggle. Photograph by Claudia Andujar

The source is the initiator, the origin of all things. It is the creation of life, a place where conflict arises or freedom is obtained; it is the space in which something is found, born or created. It is a struggle Claudia Andujar and the Yanomami shaman and leader Davi Kopenawa know too well. The Yanomami Struggle is the first retrospective exhibition in Japan by the Brazilian artist and activist Andujar with the Yanomami people of Brazil.

It is more than 50 years since she began photographing the Yanomami, the people of the Amazon rainforest near Brazil’s border with Venezuela, an initial encounter that changed their lives. Andujar’s work is not just a showcase of her photographic talent but, with Kopenawa accompanying the exhibition to Japan for the first time, it is a platform to bring the Yanomami’s message to a wider Asian audience.

The Yanomami Struggle. Photograph by Claudia Andujar

The first part of the exhibition features photographs taken by Andjuar in the 1970s, alongside artwork by the Yanomami people and words by Kopenawa. The second part narrates the continuing violence inflicted by non-Indigenous society on the Yanomami. The project is a platform for the Yamomani people to be seen and protected from ongoing threats. The exhibition, curated by Thyago Nogueira from São Paulo’s Instituto Moreira Salles, is a smaller version of one that has been touring the world since 2018.

The Yanomami Struggle, by Claudia Andujar, and artwork by the Yanomami people.

The Moroccan artist Yassine Alaoui Ismaili (Yoriyas) is showing new work made during his Kyotographie artist-in-residence programme for young Africans. The images from the Japanese city feature alongside his project Casablanca Not the Movie.

Children Transform the Sheep for Eid al-Adha into a Playground in Casablanca. Photograph by Yassine Alaoui Ismaili (Yoriyas)

Yoriyas gave up his career as a breakdancer and took up photography as a means of self-expression. His project Casablanca Not the Movie documents the streets of the city where he lives with candid shots and complex compositions. His work, which combines performance and photography, encourages us to focus on how we inhabit urban spaces. The exhibition’s clever use of display and Yoriyas’s experience with choreography force the viewer to see the work at unconventional angles. He says: “The camera frame is like a theatre stage. The people in the frame are my dancers. By moving the camera, I am choreographing my subjects without even knowing it. When an interesting movement catches my eye, I press the shutter. My training has taught me to immediately understand space, movement, connection and story. I photograph in the same way that I choreograph.”

The contrasts in Casablanca take many forms, including social, political, religious and chromatic. Photograph by Yoriyas

From Our Windows is a collaboration bringing together two important Japanese female photographers, both of whom shares aspects of their lives through photography, in a dialogue about different generations. The exhibition is supported by Women in Motion, which throws a spotlight on the talent of women in the arts in an attempt to reach gender equality in the field. Rinko Kawauchi, an internationally acclaimed photographer, chose to exhibit with Tokuko Ushioda who, at 83, continues to create vibrant new works. Kawauchi says of Ushioda: “I respect the fact that she has been active as a photographer since a time when it was difficult for women to advance in society, and that she is sincerely committed to engaging with the life that unfolds in front of her.” This exhibition features photographs taken by each of them of their families.

Photograph by Rinko Kawauchi.

Kawauchi’s two bodies of work, Cui Cui and As It Is, focus on family life. The first series is a family album relating to the death of her grandfather and the second showcases the three years after the birth of her child. Family, birth, death and daily life are threads through both bodies of work that help to create an emotional experience that transcends the generations.

Rinko Kawauchi and Tokuko Ushioda at the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art

Kawauchi says: “My works will be exhibited alongside Ushioda. Each of the works from the two series are in a space that is the same size, located side by side. The works show the accumulation of time that we have spent. They are a record of the days we spent with our families, and they are also the result of facing ourselves. We hope to share with visitors what we have seen through the act of photography, which we have continued to do even though our generations are different, and to enjoy the fact that we are now living in the same era.”

Ushioda’s first solo exhibition features two series: the intimate My Husband and also Ice Box, a fixed-point observation of her own and friends’ refrigerators. Ushioda says: “I worked on that series [Ice Box] for around 20 years or so. Like collecting insects, I took photographs of refrigerators in houses here and there and in my own home, which eventually culminated in this body of work.”

Entries from Tokuko Ushida’s series Ice Box.

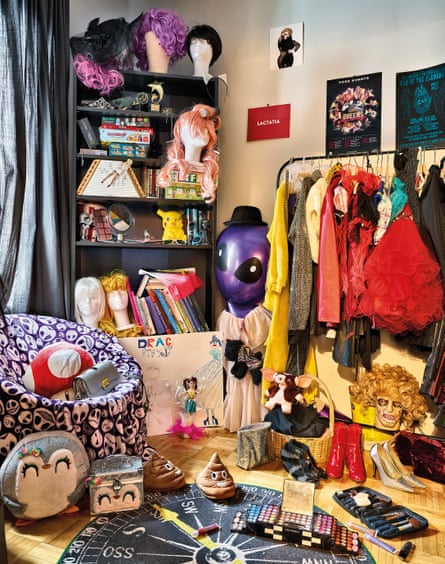

James Mollison’s ongoing project Where Children Sleep is on display at the Kyoto Art Centre with a clever display that turns each photograph into its own bedroom.

A child portrayed in Where Children Sleep, Nemis, Canada.

Featuring 35 children from 28 countries, the project encourages viewers to think about poverty, wealth, the climate emergency, gun violence, education, gender issues and refugee crises. Mollison says: “From the start, I didn’t want to think about needy children in the developing world, but rather something more inclusive, about children from all types of situations.” Featuring everything from a trailer in Kentucky during an opioid crisis and a football fan’s bedroom in Yokohama, Japan, to a tipi in Mongolia, the project offers an engrossing look at disparate lives.

From Where Children Sleep, Nirto, Somalia

Joshim, India. Photographs by James Mollison

Phosphor, Art & Fashion (1990-2023) is the first big retrospective exhibition devoted to the Dutch artist Viviane Sassen . It covers 30 years of works, including previously unseen photographs, and combines them with video installations, paintings and collages that showcase her taste for ambiguity and drama in a distinctive language of her own.

Eudocimus Ruber, from the series Of Mud and Lotus, 2017. Photograph by Viviane Sassen and Stevenson

The exhibition opens with self-portraits taken during Sassen’s time as a model. “I wanted to regain power over my own body. With a man behind the camera, a sort of tension always develops, which is often about eroticism, but usually about power,” she says. Sassen lived in Kenya as a child, and the series produced there and in South Africa are dreamlike, bold and enigmatic. She describes this period as her “years of magical thinking”. The staging of the exhibition in an old newspaper printing press contrasts with the light, shadows and bold, clashing colours of her work. The lack of natural light intensifies the flamboyant tones of the elaborately composed fashion work.

Dior Magazine (2021), and Milk, from the series Lexicon, 2006. Photographs by Viviane Sassen and Stevenson

Viviane Sassen’s immersive video installation at the Kyoto Shimbun B1F print plant. Photograph by Joanna Ruck

The source of and inspiration for Kyotographie can be traced to Lucien Clergue, the founder of Les Rencontres d’Arles, the first international photography festival, which took place in 1969. Arles, where Clergue grew up and lived all his life, was a canvas for his photography work in the 1950s. Shortly after the second world war, many Roma were freed from internment camps and came to Arles, where Clergue forged a close relationship with the community. Gypsy Tempo reveals the daily life of these families – their nomadic lifestyle, the role of religion and how music and dance are used to tell stories.

Draga in Polka-Dot Dress, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1957. Photographs by Lucien Clergue

Little Gypsy Girl in the Chapel, Cannet 1958

During this time, Clergue discovered, and then helped propel to fame, the Gypsy guitarist Manitas de Plata and his friend José Reyes. Manitas went on to become a famous musician in the 1960s who, together with Clergue, toured the world, including Japan.

Kyotographie 2024 was launched alongside its sister festival, Kyotophonie , an international music event, with performances by Los Graciosos, a band from Catalonia who play contemporary Gypsy music. Meanwhile, the sounds of De Plata can be heard by viewers of Clergue’s exhibition.

The Magic Circle, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1958, by Lucien Clergue.

Kyotographie 2024 runs until 12 May at venues across Kyoto, Japan.

- The Guardian picture essay

- Photography

- Exhibitions

- Asia Pacific

Most viewed

Japanese Culture

This essay about the economic transformation of Japan during the Meiji Restoration explores how significant reforms transitioned Japan from a feudal society to a modern industrial power. It examines the initial isolation under the Tokugawa shogunate, the strategic shifts following the 1868 Restoration, and the adoption of Western technologies and systems. These changes spurred industrial growth, modernized the economy, and integrated Japan into the global market, culminating in its rise as an economic powerhouse by the early 20th century.

How it works

Throughout the pages of history, the transformative influence of Japan’s Meiji Restoration on its economic framework is notably profound. This era is often encapsulated by a significant statement: “The Meiji Restoration catalyzed Japan’s transformation from a stagnant feudal society to a thriving industrial powerhouse, elevating it to prominence on the global economic stage.” This phrase aptly summarizes Japan’s remarkable journey during the Meiji period, highlighting the dramatic shifts towards industrialization, modernization, and international integration that defined Japan’s economic trajectory.

To fully appreciate the depth of this transformation, one must examine the economic conditions in Japan prior to the Restoration. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan was a predominantly agrarian society with entrenched feudal systems, epitomizing a strict isolationist stance through its sakoku policy, which shielded it from foreign influence. This policy of seclusion hindered economic advancement and technological progress, relegating Japan to the sidelines of global development.

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 marked a pivotal turning point, introducing a period of sweeping reforms and revitalization. The emerging Meiji government, recognizing the necessity to strengthen Japan against Western powers, initiated a bold economic overhaul aimed at rejuvenating the nation and securing its place in the global arena. Central to these reforms was the elimination of the feudal system, which liberated vast amounts of labor and capital previously confined to agricultural activities.

The leadership of the Meiji era adopted the principle of “civilization and enlightenment” (bunmei kaika), propelling the nation into an age of modernity and progress. Japan sought Western expertise and technology, sending scholars and emissaries overseas to absorb and bring back knowledge from the industrialized West. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States in 1858 signaled a significant shift from isolation to openness, facilitating the entry of foreign capital and expertise essential for industrial growth.

The blend of Western technological prowess, domestic entrepreneurial spirit, and governmental backing spurred an industrial boom across Japan. Key sectors such as textiles, shipbuilding, mining, and steel production expanded rapidly, shifting the economic landscape from its agrarian roots to an industrial base. The development of modern infrastructure like railways, telegraphs, and ports enhanced connectivity and trade, driving economic growth both domestically and internationally.

Alongside industrialization, the Meiji period saw substantial institutional reforms that supported ongoing economic growth. The creation of a modern banking system, the introduction of a national currency, and the establishment of commercial laws created a favorable climate for investment and business. Simultaneously, investments in education and the promotion of literacy developed a capable workforce, which was crucial for technological innovation and improving productivity.

Japan’s active participation in the global economy during the Meiji era significantly boosted its economic standing. Diplomatic initiatives and trade agreements with Western countries enhanced Japan’s reputation as a powerful economic entity. By the early 20th century, Japan had emerged as a leading exporter of industrial products, diversifying its economy away from reliance on agricultural exports.

In conclusion, the statement that “The Meiji Restoration catalyzed Japan’s transformation from feudal stagnation to modern industrialization, propelling it onto the global economic stage” stands as a powerful testament to the era. The Meiji period exemplifies the impact of strategic reform and visionary leadership on a nation’s destiny, moving Japan from isolation to a position of economic prominence. Its legacy continues to serve as a source of motivation, demonstrating the profound effect of determined leadership and comprehensive reform in national development.

Cite this page

Japanese Culture. (2024, Apr 22). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/japanese-culture/

"Japanese Culture." PapersOwl.com , 22 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/japanese-culture/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Japanese Culture . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/japanese-culture/ [Accessed: 22 Apr. 2024]

"Japanese Culture." PapersOwl.com, Apr 22, 2024. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/japanese-culture/

"Japanese Culture," PapersOwl.com , 22-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/japanese-culture/. [Accessed: 22-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Japanese Culture . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/japanese-culture/ [Accessed: 22-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Japanese writing boxes.

Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Tenjin Shrine (Kitano Tenjin engi emaki)

Illustrated Biography of Hōnen (Shūikotokūden-e)

Portable Writing Cabinet with Tokugawa Family Crests, Chrysanthemums, and Foliage Scrolls

- Kōami School

Plate from the Erotic Book Mounds of Dyed Colors: A Pattern Book for the Boudoir (Someiro no yama neya no hinagata), First Month

- Okumura Masanobu

Writing Box with Portrait of Fujiwara no Ietaka and His Poem about the Tatsuta River

Writing Box with Warbler in Plum Tree

Writing Box (suzuribako) with Waterfall and Auspicious Characters

Box for Square Calligraphy Paper (shikishi-bako) with an Auspicious Landscape of Young Pines and Nandina Shrubs

Set of Five Writing Boxes with Japanese Globeflowers, Plum Blossoms, and Interlaced Roundels

Table and Writing Set

- Kubo Shunman

Letter Box with Pine, Bamboo, Plum Blossom, and Family Crests

Document Box with a Scene from the “Butterflies” Chapter of The Tale of Genji

Monika Bincsik Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

January 2014

The high esteem accorded calligraphy in premodern Japanese culture is demonstrated not only by the admiration for scrolls of religious texts and poetry as works of art, but also by the way the accoutrements of brush writing were often created using the finest materials and craftsmanship.

While writing boxes ( suzuri bako , “inkstone box”) are designed for the practical function of housing writing implements such as the inkstone ( suzuri ), they are also often consummate examples of lacquer art. Inkstones were made of earthenware, porcelain, or stone that has a slightly abrasive surface to facilitate the grinding of solid inksticks ( sumi ) with water while preparing liquid ink. These solid inksticks are fashioned from soot (usually that of pine trees) and animal glue, and often scented with cloves or sandalwood. The dissolved ink accumulates in the well of the inkstone, and the calligrapher can control the density of the ink by adjusting the amount of water used and how long the inkstick is ground.

The inkstone is the most precious and permanent object of the writing set, since brushes ( fude ) wear out and inksticks eventually are ground down. The writing box also typically contains a water-dropper ( suiteki ), a small knife ( kogatana or tōsu ), and an inkstick holder ( sumi-basami ). Partially ground inksticks are placed into the holder, so even the smallest piece can be easily gripped. Many writing boxes are constructed of lacquered wood and often lavishly decorated with maki-e (“sprinkled picture”) and mother-of-pearl inlay. In many instances, the handles of the implements are also embellished with maki-e , and the decoration of the whole set is carefully coordinated. Writing boxes were developed and perfected in Japan, whereas in China the “Four Treasures of the Study” (brush, inkstick, inkstone, and paper) were usually kept on the writing desk, without a box. Writing boxes in Japan had a decorative function as well, and examples of special beauty or distinguished provenance could be displayed as prized possessions.

For both calligraphers and painters, the inkstone’s quality is as important as that of the inkstick, as it affects the texture of the ink prepared with it. In China, earthenware inkstones were produced from the Tang dynasty (618–907) onward. Natural stones such as volcanic tuff and a variety of slate were also used and these can be categorized by the locales of the quarries from which the raw stone was excavated. Rare and precious stones, crystal, or jade were also sometimes used to prepare exquisite inkstones. During the Song period , numerous famous, “named” inkstones were prepared and a refined connoisseurship developed. In Japan, the use of earthenware inkstones started during the seventh century and stone ones from around the tenth or eleventh century. The inkstones can be divided into two groups: imported from China and domestic Japanese-style stones that can be further grouped according to material or production technique. Inkstones were made in various shapes, most commonly rectangular, but round, oval, figurative, or richly decorated carved variations were also favored. Sometimes the shape of the writing box was adjusted to that of the inkstone. In Japan, during the Festival of the Weaver Maiden, on the seventh day of the seventh month a ritual is performed: “washing the inkstone” ( suzuri arai ), as the cleaning of the inkstone is said to encourage scholarly diligence.

Wooden writing boxes were prepared in Japan at least as early as the ninth or tenth century, and some of them were lacquered red, perhaps as an indication of an official position or rank. Paintings of the Heian period (794–1185) occasionally feature images of lacquer writing boxes. One of the earliest surviving examples is a Heian-period portrait of the Buddhist monk Jion Daishi (Kuiji; 632–682) in the Yakushiji in Nara, where we can see various writing implements on a small lacquer stand next to his chair. Various types of writing boxes were used in palace settings, including two-tiered boxes, shallow writing boxes, and small-size writing boxes that were part of cosmetic boxes ( tebako ). Some of these early writing boxes were quite large and also contained paper, but later the paper or documents were kept in separate boxes ( ryōshibako ) ( 1981.243.1a–f ).

A surviving Kamakura-period (1185–1333) maki-e and mother-of-pearl writing box has two little trays placed on the two sides of the inkstone (a larger one on the right and a smaller one on the left) for the brushes, handle, and other contents. This arrangement or the combination of one tray with the inkstone compartment became the most common writing box configurations ( 25.224a–e ; 1980.221 ). In the Muromachi period (1392–1573), several famous maki-e writing boxes were made, but interestingly enough, the written and visual sources of the period mostly record writing utensils imported from China. The prominent feature of the decoration of the Muromachi writing boxes is the literary reference to Japanese classics, mainly to anthologies, such as the Kokin wakashū (A Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern, ca. 920) ( 29.100.695a–e ). The poems were represented visually, but the composition often contained hidden cursive characters that should be read together with the pictorial elements ( 81.1.173 ). The decoration is composed to continue on the inside of the lid, inside of the box as well as on the sides. We can see a variety of inner configurations: some of the boxes contain two asymmetrical trays, a few have only one large tray next to the inkstone, and others have supporting panels on both sides of the inkstone compartment to support the implements. During the Higashiyama period (later fifteenth century), the shōin -style interior decoration designated two areas for writing utensils: formal locations featured Chinese implements , informal spaces Japanese domestic utensils, including writing boxes. Many of the Muromachi-period writing boxes became famous collectibles, and now most of them are highly regarded Important Cultural Properties. From the mid-sixteenth century, writing boxes and writing tables ( bundai ) were prepared in sets. Momoyama-period (1573–1615) writing boxes are recognized for their bold designs. A new style, characterized by asymmetrical compositions, often depicting autumn grasses executed in flat maki-e ( hiramaki-e ) is associated with the Kōdaiji Temple in Kyoto (Kōdaiji maki-e ).

During the Edo period (1615–1868), several new box shapes and structures were created with a wide variety of decorative designs, including references to classical literature ( 29.100.688 ; 29.100.695a–e ) and motifs inspired by everyday life or patterns shared with other decorative art genres ( 81.1.136a–z ) and kimono. Elaborate, luxurious maki-e decorated writing boxes were prepared by the two well-known maki-e master families: the Kōami in Edo (formerly in Kyoto) ( 81.1.133a–h ) and the Igarashi in Kaga Province (present-day Ishikawa Prefecture). New, distinctive styles were developed by Hon’ami Kōetsu (1558–1637) and Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) characterized by bold, graphic decoration and pewter inlays in addition to the maki-e and mother-of-pearl embellishment. These Rinpa-style lacquer writing boxes remained popular through the nineteenth century. Ogawa Haritsu (1663–1747), the eccentric lacquer master, created writing boxes with unconventional decorations and techniques such as the inclusion and imitation of ceramic, metal, or carved red lacquer inlays.

Various complex structures developed from the Heian-period “writing box prototypes,” including tiered writing boxes for poetry contests or incense games ( 81.1.136a–z ) and combinations of cosmetic sets with writing boxes such as the portable “comb-box” ( tabikushi-bako ) that includes a special drawer for the writing implements. From the early Edo period , writing boxes, document boxes, writing tables, and letter boxes ( fubako ) became part of wedding sets (dowry) and were prepared in standard sizes, often decorated with auspicious motifs such as cranes or pine, bamboo, and plum patterns ( 10.7.22 ). The appreciation of calligraphy and painting was also reflected in the preparation of specialized maki-e stationery, such as boxes for elongated poem slips ( tanzaku ) or square-shaped poem cards ( shikishi ) ( 81.1.152a,b ).

During the Meiji period (1868–1912), along with the emergence of innovative writing box shapes and decorations reflecting modernist sensibilities, works drawing on historical styles and decorative schemes were revived and copies of famous boxes were prepared. Elaborately crafted sets of writing boxes, document boxes, and writing tables were often featured in world expositions, as they represented indigenous Japanese calligraphy traditions ( 1981.243.1a–f ). Westerners began collecting Japanese writing boxes in earnest from the early Meiji period onward.

Bincsik, Monika. “Japanese Writing Boxes.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jabo/hd_jabo.htm (January 2014)

Further Reading

Bincsik, Monika. "Plum Flowers and Cherry Blossoms: Auspicious Symbols of a Political Alliance: A Maki-e Daimyo Wedding Set," in Orientations 40, no. 6 (September 2009) pp. 73–79.

Pekarik, Andrew W. Japanese Lacquer, 1600–1900: Selections from the Charles A. Greenfield Collection . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980. See on MetPublications

Watt, James C. Y., and Barbara Brennan Ford. East Asian Lacquer: The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991. See on MetPublications

Additional Essays by Monika Bincsik

- Bincsik, Monika. “ Japanese Incense .” (March 2009)

- Bincsik, Monika. “ Japanese Weddings in the Edo Period (1615–1868) .” (March 2009)

Related Essays

- Japanese Illustrated Handscrolls

- Japanese Incense

- The Japanese Tea Ceremony

- Japanese Weddings in the Edo Period (1615–1868)

- Muromachi Period (1392–1573)

- Yangban : The Cultural Life of the Joseon Literati

- Buddhism and Buddhist Art

- Calligraphy in Islamic Art

- Edo-Period Japanese Porcelain

- French Furniture in the Eighteenth Century: Case Furniture

- Heian Period (794–1185)

- Kamakura and Nanbokucho Periods (1185–1392)

- The Kano School of Painting

- Lacquerware of East Asia

- Netsuke: From Fashion Fobs to Coveted Collectibles

- Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127)

- The Origins of Writing

- Rinpa Painting Style

- Seasonal Imagery in Japanese Art

- Tang Dynasty (618–907)

- Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Japan

- China, 500–1000 A.D.

- Japan, 1000–1400 A.D.

- Japan, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Japan, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Japan, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Japan, 500–1000 A.D.

- Aquatic Animal

- Calligraphy

- Chinese Literature / Poetry

- Floral Motif

- Heian Period

- Japanese Literature / Poetry

- Kamakura Period

- Literature / Poetry

- Meiji Period

- Muromachi Period

- Northern Song Dynasty

- Printmaking

- Southern Song Dynasty

- Tang Dynasty

- Writing Implement

- Yamato-e Style

Artist or Maker

- Hon'ami Kōetsu

- Ogata Kōrin

- Tawaraya Sōtatsu

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In summary, the range of Japanese visual art is extensive, and some elements seem truly antithetical.An illuminated sutra manuscript of the 12th century and a macabre scene of seppuku (ritual disembowelment) rendered by the 19th-century print artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi can be forced into a common aesthetic only in the most artificial way. The viewer is thus advised to expect a startling range ...

The Kano school was the longest lived and most influential school of painting in Japanese history; its more than 300-year prominence is unique in world art history. Jump to content tickets Member | Make a donation. Search. ... Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1988. Additional Essays by Department of Asian Art.

James Tissot and his friend Edgar Degas ( 29.100.127) were among the earliest collectors of Japanese art in France, but their own art was affected by exotic things in very different ways. Unlike Tissot, and others who came under the spell of Japan, Degas avoided staging japoneries that featured models dressed in kimonos and the conspicuous ...

The Jōmon period is Japan's Neolithic period. People obtained food by gathering, fishing, and hunting and often migrated to cooler or warmer areas as a result of shifts in climate. In Japanese, jōmon means "cord pattern," which refers to the technique of decorating Jōmon-period pottery.

History of Japanese Art. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. Murase, Miyeko. Bridge of Dreams: The Mary Griggs Burke Collection of Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. See on MetPublications. Murase, Miyeko. Masterpieces of Japanese Screen Painting: The American Collections. New York: G. Braziller, 1990 ...

Legitimizing genealogies are a hallmark of Japanese art history. The advancement of ink painting under the influence of Sesshū is part and parcel of the second Ashikaga-patronized sociocultural sub-period—the so-called Higashiyama culture, named after an area east of Kyoto, where the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa had a silver pavilion ...

Introduction to Japan. Map of Japan. Courtesy of the Asian Art Museum. Japan is an island country consisting of four major and numerous smaller islands. The islands lie in an arc across the Pacific coast of northeastern Asia, forming a part of the volcanic "Rim of Fire.". From north to south this chain of islands measures more than 1,500 ...

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods. By Dr. Sonia Coman. Learn about tea-ceremonies, opulent palaces, and splashed-ink paintings from Japan's Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods. Learn more.

RESOURCES BOOK REVIEW ESSAY The History of Art in Japan By Nobuo Tsuji and (trans.) Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere New York: Columbia University Press, 2019 664 pages, ISBN: 978-0231193412, Paperback Reviewed by Brenda G. Jordan N obuo Tsuji's History of Art in Japan was originally published by the University of Tokyo Press in 2005 and is now available in English translation.

It was much more difficult to fully comprehend the transition of Japanese artworks in the western style through Art Nouveau and into Art Deco than I would have imagined. Download Free PDF View PDF (Paper presentation) On vision and display: Arts and culture in Meiji Japan (@ International IIAS/HKS Seminar: New Perspectives on (the Presentation ...