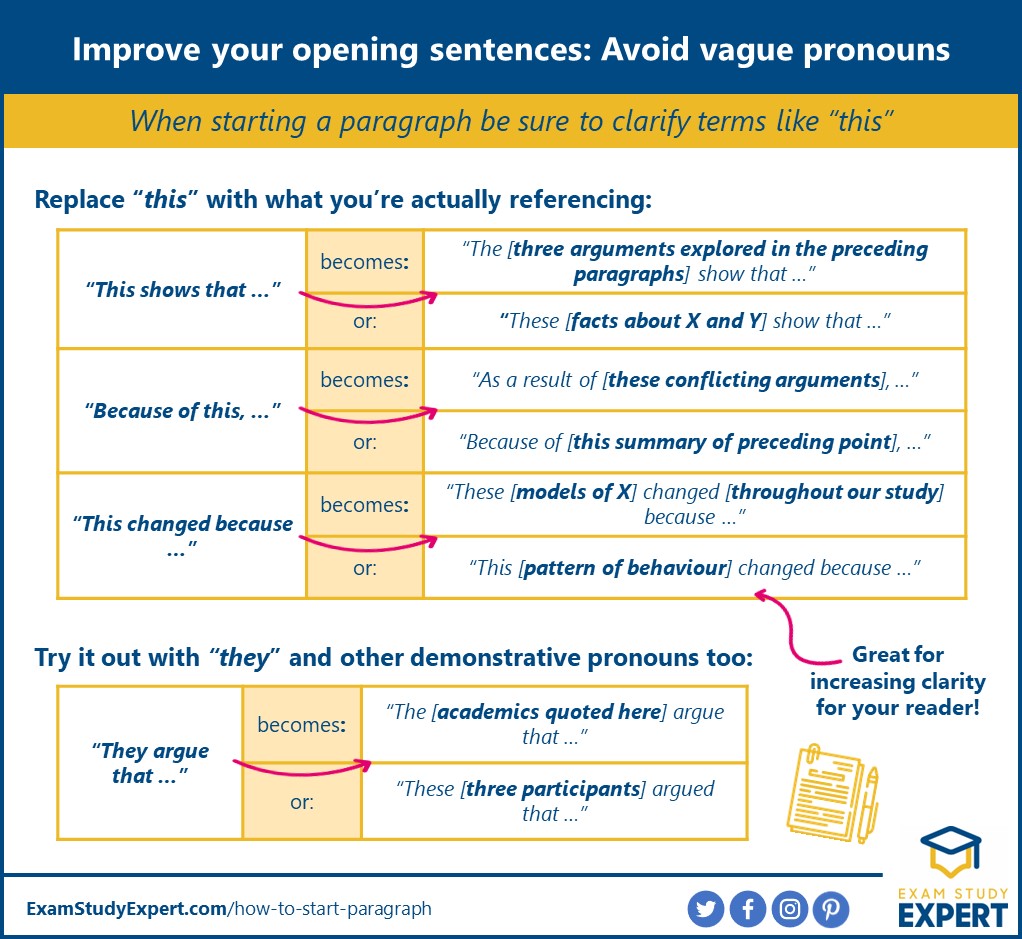

Home ➔ How to Write an Essay ➔ Words to Use in an Essay ➔ Sentence Starters

Sentence Starters for Essays

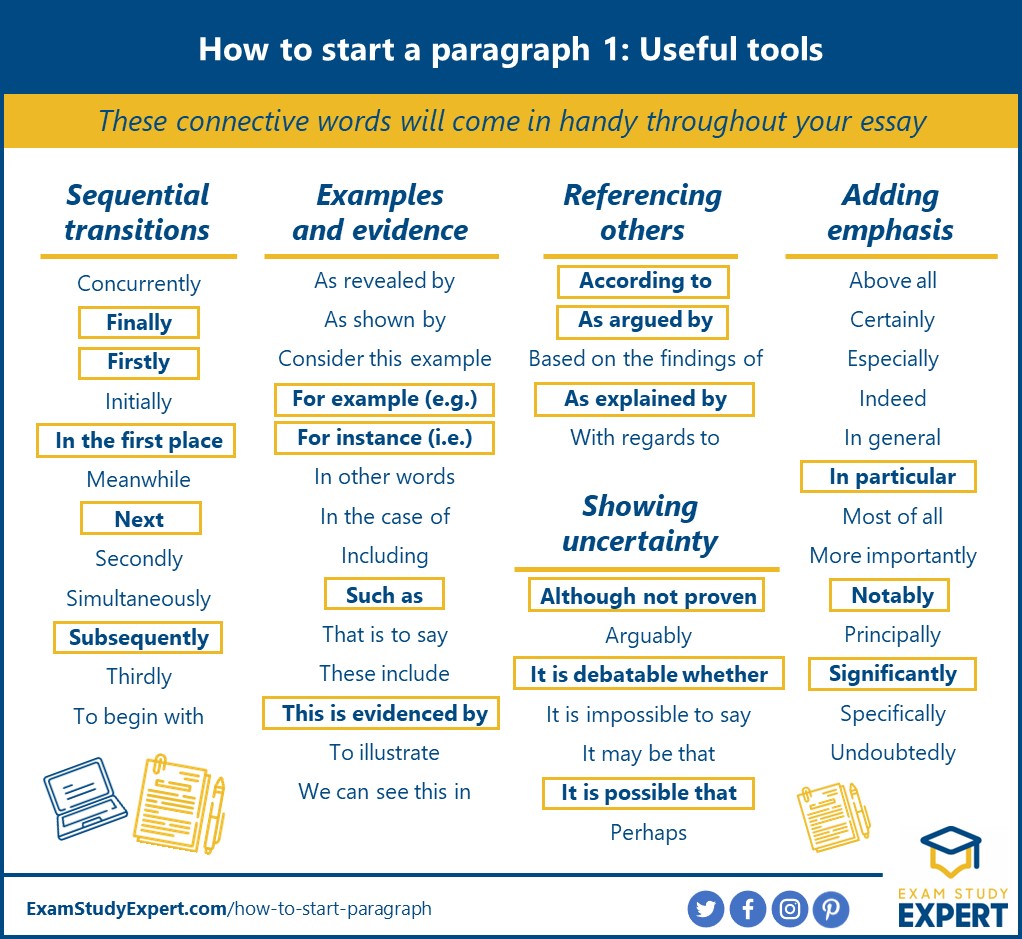

A sentence starter is simply a word or a phrase that will help you to get your sentence going when you feel stuck, and it can be helpful in many different situations. A good sentence starter can help you better transition from one paragraph to another or connect two ideas. If not started correctly, your sentence will likely sound choppy, and your reader might not be able to follow your thoughts.

Below, we will explain when sentence starters for essays are used and what types of them exist. We will then give you plenty of examples of sentence-starter words and phrases that you can use in your writing.

Note: To learn more about word choice in academic writing, you can read our guide: Words to Use in an Essay

Why you need good sentence starters

In academic writing, sentence starters are usually used to connect one idea to another. Sentence starters make your essay coherent as they are often used to transition from one paragraph to another. In other words, they glue your writing together so that it makes sense and is easy to read.

You can also use sentence starters inside paragraphs. This will help you to better transition from one idea to another. It can make your writing flow better and sound more unified if done correctly.

When sentence starters are used

You don’t have to use them in every sentence, but they can be helpful if you feel like your ideas are choppy or you want to connect two thoughts. If overused, sentence starters can make your writing sound repetitive and distracting to the reader.

Here’s a list of cases where you should consider using sentence starters:

- To transition from one paragraph or section of your writing to another

- To introduce a new idea at the start of your essay or paragraph

- To start the final paragraph and conclude the entire essay

- To emphasize something important

- To create a hook and grab your reader’s attention

- To clarify something or give brief background information

These are just some common situations for using sentence starters, and this list is not definitive. If you can’t decide whether or not to use a sentence starter, it’s usually best to err on the side of not using one. If your paragraph flows nicely, don’t overthink it and move on with your essay writing .

What are the different types of sentence starters?

Sentence starters vary based on what you want to achieve in the sentence you’re starting. Here are some of the most common purposes that define what sentence starter you need to apply, along with some examples.

Starters for hooks

If you want to grab your reader’s attention in the first paragraph and make them want to read your essay, you need to use introduction sentence starters that are attention-grabbing and interesting. Some common sentence starters for essay hooks are:

- Did you know that… (for a fact)

- When I was… (for an anecdote)

- Just as… (for an analogy)

- According to… (for a statistic)

Starters to start a thesis statement

The thesis statement is the main idea of your essay. It’s what you want to prove or argue in your essay. You will need to use sentence starters that introduce your essay topic in a clear and concise way. For example:

- This essay will discuss…

- The purpose of this essay is to…

- In this essay, I will argue that…

- In my opinion…

- I think that…

Starters for topic sentences

A topic sentence is the first sentence at the beginning of each body paragraph that introduces the main idea of the paragraph. You will want to use body paragraph starters that state the main idea of the paragraph in a clear and concise way. Some specific examples:

- One reason why…

- The most important thing to remember is that…

- Another important factor to consider is…

- The first thing to note is that…

- It’s important to remember that…

- Besides the previous point,…

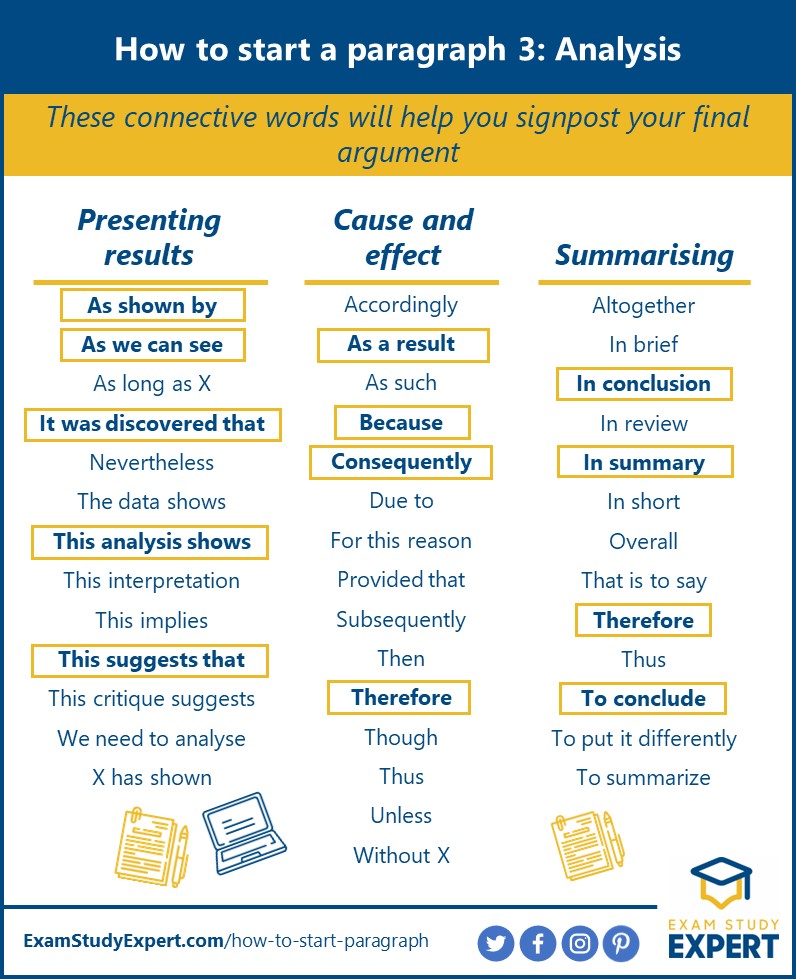

Starters for concluding

When you’re concluding your essay , you need to use conclusion sentence starters that emphasize the main points of your argument and leave your reader with a strong impression. Here are some examples:

- In conclusion,…

- To sum up,…

- Overall,…

- To conclude,…

- Finally,…

- In the final analysis,…

Starters for lists

If you’re listing ideas or items, you will want to use sentence starters that introduce each item clearly. Some common list starters are:

- The first…

- The second…

- Thirdly,…

- Next,…

- Lastly,…

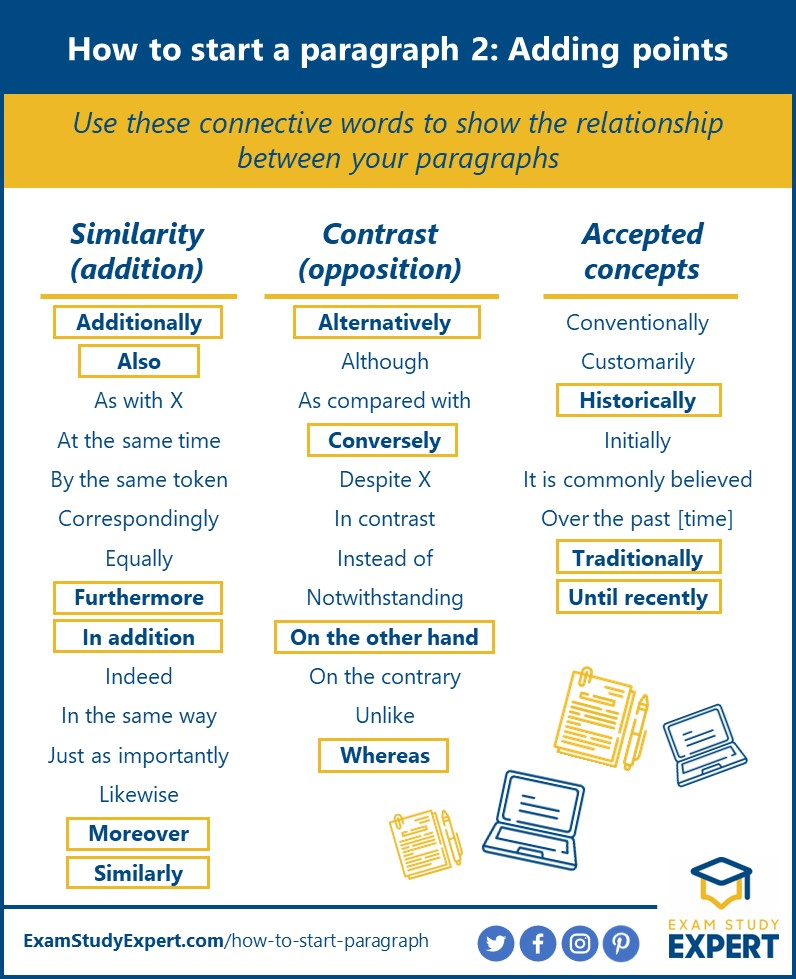

Starters for comparing and contrasting

If you’re writing an essay that compares and contrasts two or more things, you will need to use sentence starters that introduce each item you’re discussing and emphasize the similarities and/or differences. For example:

- Similarly,…

- However,…

- In contrast to…

- On the other hand,…

- Compared to…

- Despite the fact that…

Starters for elaborating

If you want to elaborate on an idea, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the detail you’re going to include and how it relates to the main idea. Some common starters for elaborating are:

- For example,…

- In other words,…

- That is to say,…

- To elaborate,…

- Another way to put it would be…

- To put it more simply,…

Starters for giving background information

If you want to give some brief background information in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the information and explain why it’s relevant. For example:

- As previously mentioned,…

- As everyone knows,…

- In today’s society,…

Starters for giving an example

If you want to give an example in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the example and explain how it supports your argument. For example:

- For instance,…

- To illustrate,…

- Thus,…

- In this case,…

Starters for introducing a quotation

If you want to include a quotation in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the quotation and explain its relevance. Some examples:

- As John Doe said,…

- According to Jane Doe,…

- As the old saying goes,…

- In Jane Doe’s words,…

- To put it another way,…

Starters for introducing evidence

If you want to include evidence in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the evidence and explain its relevance. For example:

- The data shows that…

- This proves that…

- This suggests that…

- The evidence indicates that…

Starters for bridging

If you want to create a bridge sentence between two paragraphs, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the second paragraph and explain how it relates to the first. For example:

- This leads to the question,…

- This raises the issue,…

- Another important point to consider is…

- This brings us to the question of…

Starters to show causation

If you want to show causation in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that introduce the cause and explain its relationship to the effect. For example:

- Because of this,…

- As a result,…

- Consequently,…

- Due to the fact that…

- Therefore,…

Starters to emphasize a point

If you want to emphasize a point in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that draw attention to the point and make it clear why it’s important. Examples of sentence starters to add emphasis:

- Importantly,…

- Significantly,…

Starters to express doubt

If you want to express doubt about an idea in your essay, you need to use sentence starters that make it clear you’re not certain and explain why you have doubts. For example:

- It’s possible that…

- It’s uncertain whether…

- Some people might argue that…

- There is evidence to suggest that…

- Although it is debatable,…

- It might be the case that…

Key takeaways

- Sentence starters are especially important in academic writing because they can help you make complex arguments and express yourself clearly.

- There are many different types of sentence starters, each with its own purpose.

- You need to choose the right sentence starter for the specific task you’re writing about.

- When in doubt, err on the side of caution and choose a simpler sentence starter.

Now that you know the different types of sentence starters and how to use them effectively, you’ll be able to write clear, concise, and well-organized essays.

Was this article helpful?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

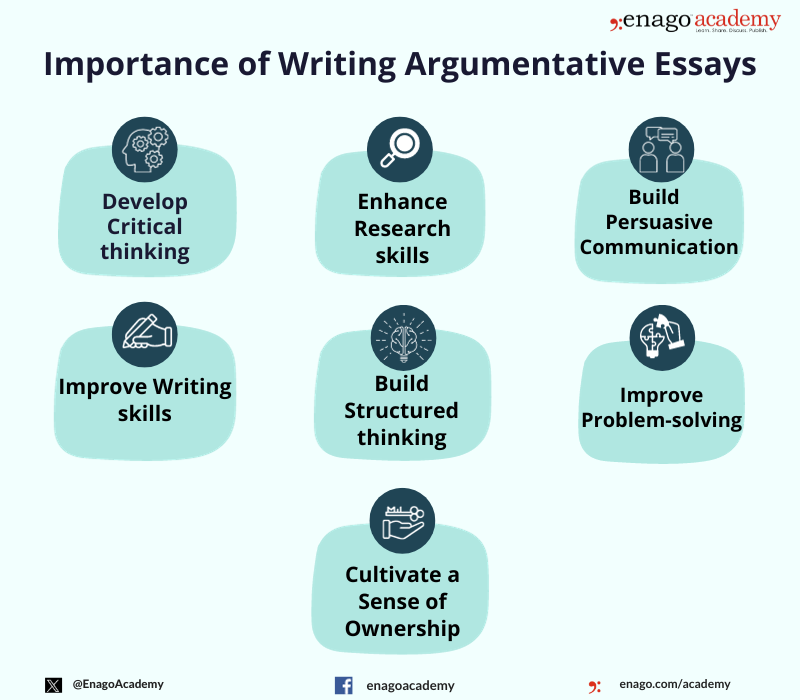

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

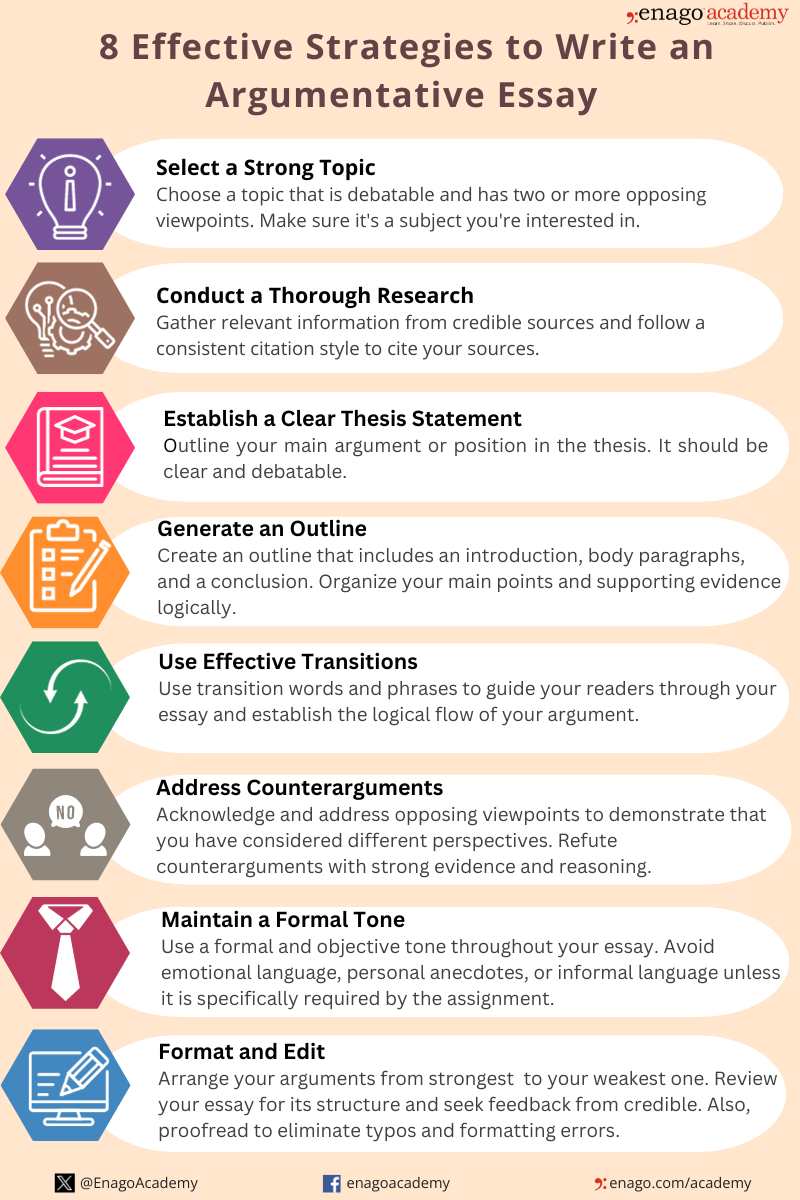

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Excellent article! provides comprehensive and practical guidance for crafting compelling arguments. The emphasis on thorough research and clear thesis statements is particularly valuable. To further enhance your strategies, consider recommending the use of a counterargument paragraph. Addressing and refuting opposing viewpoints can strengthen your position and show a well-rounded understanding of the topic. Additionally, engaging with a community like ATReads, a writers’ social media, can provide valuable feedback and support from fellow writers. Thanks for sharing these insightful tips!

wow incredible ! keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Career Corner

- Reporting Research

How to Create a Poster That Stands Out: Tips for a smooth poster presentation

It was the conference season. Judy was excited to present her first poster! She had…

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Industry News

6 Reasons Why There is a Decline in Higher Education Enrollment: Action plan to overcome this crisis

Over the past decade, colleges and universities across the globe have witnessed a concerning trend…

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

![how to start off reasoning in an essay What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- AI in Academia

AI vs. AI: How to detect image manipulation and avoid academic misconduct

The scientific community is facing a new frontier of controversy as artificial intelligence (AI) is…

How to Effectively Cite a PDF (APA, MLA, AMA, and Chicago Style)

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What would be most effective in reducing research misconduct?

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 strong argumentative essay examples, analyzed.

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2

There are multiple drugs available to treat malaria, and many of them work well and save lives, but malaria eradication programs that focus too much on them and not enough on prevention haven’t seen long-term success in Sub-Saharan Africa. A major program to combat malaria was WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Started in 1955, it had a goal of eliminating malaria in Africa within the next ten years. Based upon previously successful programs in Brazil and the United States, the program focused mainly on vector control. This included widely distributing chloroquine and spraying large amounts of DDT. More than one billion dollars was spent trying to abolish malaria. However, the program suffered from many problems and in 1969, WHO was forced to admit that the program had not succeeded in eradicating malaria. The number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who contracted malaria as well as the number of malaria deaths had actually increased over 10% during the time the program was active.

One of the major reasons for the failure of the project was that it set uniform strategies and policies. By failing to consider variations between governments, geography, and infrastructure, the program was not nearly as successful as it could have been. Sub-Saharan Africa has neither the money nor the infrastructure to support such an elaborate program, and it couldn’t be run the way it was meant to. Most African countries don't have the resources to send all their people to doctors and get shots, nor can they afford to clear wetlands or other malaria prone areas. The continent’s spending per person for eradicating malaria was just a quarter of what Brazil spent. Sub-Saharan Africa simply can’t rely on a plan that requires more money, infrastructure, and expertise than they have to spare.

Additionally, the widespread use of chloroquine has created drug resistant parasites which are now plaguing Sub-Saharan Africa. Because chloroquine was used widely but inconsistently, mosquitoes developed resistance, and chloroquine is now nearly completely ineffective in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 95% of mosquitoes resistant to it. As a result, newer, more expensive drugs need to be used to prevent and treat malaria, which further drives up the cost of malaria treatment for a region that can ill afford it.

Instead of developing plans to treat malaria after the infection has incurred, programs should focus on preventing infection from occurring in the first place. Not only is this plan cheaper and more effective, reducing the number of people who contract malaria also reduces loss of work/school days which can further bring down the productivity of the region.

One of the cheapest and most effective ways of preventing malaria is to implement insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). These nets provide a protective barrier around the person or people using them. While untreated bed nets are still helpful, those treated with insecticides are much more useful because they stop mosquitoes from biting people through the nets, and they help reduce mosquito populations in a community, thus helping people who don’t even own bed nets. Bed nets are also very effective because most mosquito bites occur while the person is sleeping, so bed nets would be able to drastically reduce the number of transmissions during the night. In fact, transmission of malaria can be reduced by as much as 90% in areas where the use of ITNs is widespread. Because money is so scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, the low cost is a great benefit and a major reason why the program is so successful. Bed nets cost roughly 2 USD to make, last several years, and can protect two adults. Studies have shown that, for every 100-1000 more nets are being used, one less child dies of malaria. With an estimated 300 million people in Africa not being protected by mosquito nets, there’s the potential to save three million lives by spending just a few dollars per person.

Reducing the number of people who contract malaria would also reduce poverty levels in Africa significantly, thus improving other aspects of society like education levels and the economy. Vector control is more effective than treatment strategies because it means fewer people are getting sick. When fewer people get sick, the working population is stronger as a whole because people are not put out of work from malaria, nor are they caring for sick relatives. Malaria-afflicted families can typically only harvest 40% of the crops that healthy families can harvest. Additionally, a family with members who have malaria spends roughly a quarter of its income treatment, not including the loss of work they also must deal with due to the illness. It’s estimated that malaria costs Africa 12 billion USD in lost income every year. A strong working population creates a stronger economy, which Sub-Saharan Africa is in desperate need of.

This essay begins with an introduction, which ends with the thesis (that malaria eradication plans in Sub-Saharan Africa should focus on prevention rather than treatment). The first part of the essay lays out why the counter argument (treatment rather than prevention) is not as effective, and the second part of the essay focuses on why prevention of malaria is the better path to take.

- The thesis appears early, is stated clearly, and is supported throughout the rest of the essay. This makes the argument clear for readers to understand and follow throughout the essay.

- There’s lots of solid research in this essay, including specific programs that were conducted and how successful they were, as well as specific data mentioned throughout. This evidence helps strengthen the author’s argument.

- The author makes a case for using expanding bed net use over waiting until malaria occurs and beginning treatment, but not much of a plan is given for how the bed nets would be distributed or how to ensure they’re being used properly. By going more into detail of what she believes should be done, the author would be making a stronger argument.

- The introduction of the essay does a good job of laying out the seriousness of the problem, but the conclusion is short and abrupt. Expanding it into its own paragraph would give the author a final way to convince readers of her side of the argument.

Argumentative Essay Example 3

There are many ways payments could work. They could be in the form of a free-market approach, where athletes are able to earn whatever the market is willing to pay them, it could be a set amount of money per athlete, or student athletes could earn income from endorsements, autographs, and control of their likeness, similar to the way top Olympians earn money.

Proponents of the idea believe that, because college athletes are the ones who are training, participating in games, and bringing in audiences, they should receive some sort of compensation for their work. If there were no college athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist, college coaches wouldn’t receive there (sometimes very high) salaries, and brands like Nike couldn’t profit from college sports. In fact, the NCAA brings in roughly $1 billion in revenue a year, but college athletes don’t receive any of that money in the form of a paycheck. Additionally, people who believe college athletes should be paid state that paying college athletes will actually encourage them to remain in college longer and not turn pro as quickly, either by giving them a way to begin earning money in college or requiring them to sign a contract stating they’ll stay at the university for a certain number of years while making an agreed-upon salary.

Supporters of this idea point to Zion Williamson, the Duke basketball superstar, who, during his freshman year, sustained a serious knee injury. Many argued that, even if he enjoyed playing for Duke, it wasn’t worth risking another injury and ending his professional career before it even began for a program that wasn’t paying him. Williamson seems to have agreed with them and declared his eligibility for the NCAA draft later that year. If he was being paid, he may have stayed at Duke longer. In fact, roughly a third of student athletes surveyed stated that receiving a salary while in college would make them “strongly consider” remaining collegiate athletes longer before turning pro.

Paying athletes could also stop the recruitment scandals that have plagued the NCAA. In 2018, the NCAA stripped the University of Louisville's men's basketball team of its 2013 national championship title because it was discovered coaches were using sex workers to entice recruits to join the team. There have been dozens of other recruitment scandals where college athletes and recruits have been bribed with anything from having their grades changed, to getting free cars, to being straight out bribed. By paying college athletes and putting their salaries out in the open, the NCAA could end the illegal and underhanded ways some schools and coaches try to entice athletes to join.

People who argue against the idea of paying college athletes believe the practice could be disastrous for college sports. By paying athletes, they argue, they’d turn college sports into a bidding war, where only the richest schools could afford top athletes, and the majority of schools would be shut out from developing a talented team (though some argue this already happens because the best players often go to the most established college sports programs, who typically pay their coaches millions of dollars per year). It could also ruin the tight camaraderie of many college teams if players become jealous that certain teammates are making more money than they are.

They also argue that paying college athletes actually means only a small fraction would make significant money. Out of the 350 Division I athletic departments, fewer than a dozen earn any money. Nearly all the money the NCAA makes comes from men’s football and basketball, so paying college athletes would make a small group of men--who likely will be signed to pro teams and begin making millions immediately out of college--rich at the expense of other players.

Those against paying college athletes also believe that the athletes are receiving enough benefits already. The top athletes already receive scholarships that are worth tens of thousands per year, they receive free food/housing/textbooks, have access to top medical care if they are injured, receive top coaching, get travel perks and free gear, and can use their time in college as a way to capture the attention of professional recruiters. No other college students receive anywhere near as much from their schools.

People on this side also point out that, while the NCAA brings in a massive amount of money each year, it is still a non-profit organization. How? Because over 95% of those profits are redistributed to its members’ institutions in the form of scholarships, grants, conferences, support for Division II and Division III teams, and educational programs. Taking away a significant part of that revenue would hurt smaller programs that rely on that money to keep running.

While both sides have good points, it’s clear that the negatives of paying college athletes far outweigh the positives. College athletes spend a significant amount of time and energy playing for their school, but they are compensated for it by the scholarships and perks they receive. Adding a salary to that would result in a college athletic system where only a small handful of athletes (those likely to become millionaires in the professional leagues) are paid by a handful of schools who enter bidding wars to recruit them, while the majority of student athletics and college athletic programs suffer or even shut down for lack of money. Continuing to offer the current level of benefits to student athletes makes it possible for as many people to benefit from and enjoy college sports as possible.

This argumentative essay follows the Rogerian model. It discusses each side, first laying out multiple reasons people believe student athletes should be paid, then discussing reasons why the athletes shouldn’t be paid. It ends by stating that college athletes shouldn’t be paid by arguing that paying them would destroy college athletics programs and cause them to have many of the issues professional sports leagues have.

- Both sides of the argument are well developed, with multiple reasons why people agree with each side. It allows readers to get a full view of the argument and its nuances.

- Certain statements on both sides are directly rebuffed in order to show where the strengths and weaknesses of each side lie and give a more complete and sophisticated look at the argument.

- Using the Rogerian model can be tricky because oftentimes you don’t explicitly state your argument until the end of the paper. Here, the thesis doesn’t appear until the first sentence of the final paragraph. That doesn’t give readers a lot of time to be convinced that your argument is the right one, compared to a paper where the thesis is stated in the beginning and then supported throughout the paper. This paper could be strengthened if the final paragraph was expanded to more fully explain why the author supports the view, or if the paper had made it clearer that paying athletes was the weaker argument throughout.

3 Tips for Writing a Good Argumentative Essay

Now that you’ve seen examples of what good argumentative essay samples look like, follow these three tips when crafting your own essay.

#1: Make Your Thesis Crystal Clear

The thesis is the key to your argumentative essay; if it isn’t clear or readers can’t find it easily, your entire essay will be weak as a result. Always make sure that your thesis statement is easy to find. The typical spot for it is the final sentence of the introduction paragraph, but if it doesn’t fit in that spot for your essay, try to at least put it as the first or last sentence of a different paragraph so it stands out more.

Also make sure that your thesis makes clear what side of the argument you’re on. After you’ve written it, it’s a great idea to show your thesis to a couple different people--classmates are great for this. Just by reading your thesis they should be able to understand what point you’ll be trying to make with the rest of your essay.

#2: Show Why the Other Side Is Weak

When writing your essay, you may be tempted to ignore the other side of the argument and just focus on your side, but don’t do this. The best argumentative essays really tear apart the other side to show why readers shouldn’t believe it. Before you begin writing your essay, research what the other side believes, and what their strongest points are. Then, in your essay, be sure to mention each of these and use evidence to explain why they’re incorrect/weak arguments. That’ll make your essay much more effective than if you only focused on your side of the argument.

#3: Use Evidence to Support Your Side

Remember, an essay can’t be an argumentative essay if it doesn’t support its argument with evidence. For every point you make, make sure you have facts to back it up. Some examples are previous studies done on the topic, surveys of large groups of people, data points, etc. There should be lots of numbers in your argumentative essay that support your side of the argument. This will make your essay much stronger compared to only relying on your own opinions to support your argument.

Summary: Argumentative Essay Sample

Argumentative essays are persuasive essays that use facts and evidence to support their side of the argument. Most argumentative essays follow either the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model. By reading good argumentative essay examples, you can learn how to develop your essay and provide enough support to make readers agree with your opinion. When writing your essay, remember to always make your thesis clear, show where the other side is weak, and back up your opinion with data and evidence.

What's Next?

Do you need to write an argumentative essay as well? Check out our guide on the best argumentative essay topics for ideas!

You'll probably also need to write research papers for school. We've got you covered with 113 potential topics for research papers.

Your college admissions essay may end up being one of the most important essays you write. Follow our step-by-step guide on writing a personal statement to have an essay that'll impress colleges.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

105 Best Words To Start A Paragraph

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

The first words of a paragraph are crucial as they set the tone and inform the reader about the content that follows.

Known as the ‘topic’ sentence, the first sentence of the paragraph should clearly convey the paragraph’s main idea.

This article presents a comprehensive list of the best words to start a paragraph, be it the first, second, third, or concluding paragraph.

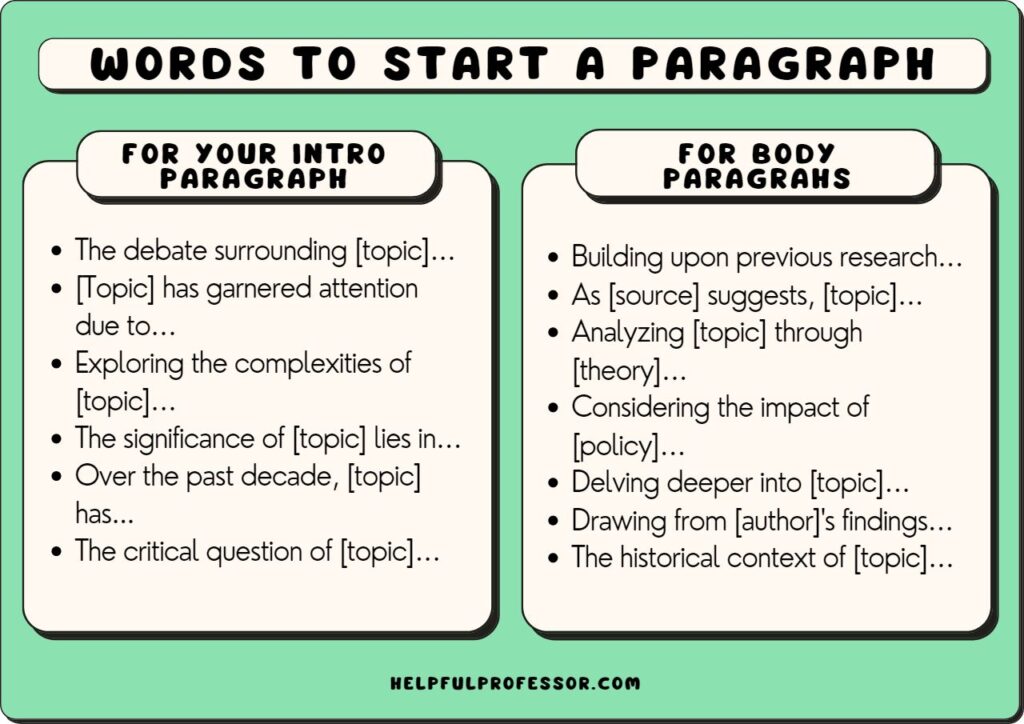

Words to Start an Introduction Paragraph

The words you choose for starting an essay should establish the context, importance, or conflict of your topic.

The purpose of an introduction is to provide the reader with a clear understanding of the topic, its significance, and the structure of the ensuing discussion or argument.

Students often struggle to think of ways to start introductions because they may feel overwhelmed by the need to effectively summarize and contextualize their topic, capture the reader’s interest, and provide a roadmap for the rest of the paper, all while trying to create a strong first impression.

Choose one of these example words to start an introduction to get yourself started:

- The debate surrounding [topic]…

- [Topic] has garnered attention due to…

- Exploring the complexities of [topic]…

- The significance of [topic] lies in…

- Over the past decade, [topic] has…

- The critical question of [topic]…

- As society grapples with [topic]…

- The rapidly evolving landscape of [topic]…

- A closer examination of [topic] reveals…

- The ongoing conversation around [topic]…

Don’t Miss my Article: 33 Words to Avoid in an Essay

Words to Start a Body Paragraph

The purpose of a body paragraph in an essay is to develop and support the main argument, presenting evidence, examples, and analysis that contribute to the overall thesis.

Students may struggle to think of ways to start body paragraphs because they need to find appropriate transition words or phrases that seamlessly connect the paragraphs, while also introducing a new idea or evidence that builds on the previous points.

This can be challenging, as students must carefully balance the need for continuity and logical flow with the introduction of fresh perspectives.

Try some of these paragraph starters if you’re stuck:

- Building upon previous research…

- As [source] suggests, [topic]…

- Analyzing [topic] through [theory]…

- Considering the impact of [policy]…

- Delving deeper into [topic]…

- Drawing from [author]’s findings…

- [Topic] intersects with [related topic]…

- Contrary to popular belief, [topic]…

- The historical context of [topic]…

- Addressing the challenges of [topic]…

Words to Start a Conclusion Paragraph

The conclusion paragraph wraps up your essay and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

It should convincingly summarize your thesis and main points. For more tips on writing a compelling conclusion, consider the following examples of ways to say “in conclusion”:

- In summary, [topic] demonstrates…

- The evidence overwhelmingly suggests…

- Taking all factors into account…

- In light of the analysis, [topic]…

- Ultimately, [topic] plays a crucial role…

- In light of these findings…

- Weighing the pros and cons of [topic]…

- By synthesizing the key points…

- The interplay of factors in [topic]…

- [Topic] leaves us with important implications…

Complete List of Transition Words

Above, I’ve provided 30 different examples of phrases you can copy and paste to get started on your paragraphs.

Let’s finish strong with a comprehensive list of transition words you can mix and match to start any paragraph you want:

- Secondly, …

- In addition, …

- Furthermore, …

- Moreover, …

- On the other hand, …

- In contrast, …

- Conversely, …

- Despite this, …

- Nevertheless, …

- Although, …

- As a result, …

- Consequently, …

- Therefore, …

- Additionally, …

- Simultaneously, …

- Meanwhile, …

- In comparison, …

- Comparatively, …

- As previously mentioned, …

- For instance, …

- For example, …

- Specifically, …

- In particular, …

- Significantly, …

- Interestingly, …

- Surprisingly, …

- Importantly, …

- According to [source], …

- As [source] states, …

- As [source] suggests, …

- In the context of, …

- In light of, …

- Taking into consideration, …

- Given that, …

- Considering the fact that, …

- Bearing in mind, …

- To illustrate, …

- To demonstrate, …

- To clarify, …

- To put it simply, …

- In other words, …

- To reiterate, …

- As a matter of fact, …

- Undoubtedly, …

- Unquestionably, …

- Without a doubt, …

- It is worth noting that, …

- One could argue that, …

- It is essential to highlight, …

- It is important to emphasize, …

- It is crucial to mention, …

- When examining, …

- In terms of, …

- With regards to, …

- In relation to, …

- As a consequence, …

- As an illustration, …

- As evidence, …

- Based on [source], …

- Building upon, …

- By the same token, …

- In the same vein, …

- In support of this, …

- In line with, …

- To further support, …

- To substantiate, …

- To provide context, …

- To put this into perspective, …

Tip: Use Right-Branching Sentences to Start your Paragraphs

Sentences should have the key information front-loaded. This makes them easier to read. So, start your sentence with the key information!

To understand this, you need to understand two contrasting types of sentences:

- Left-branching sentences , also known as front-loaded sentences, begin with the main subject and verb, followed by modifiers, additional information, or clauses.

- Right-branching sentences , or back-loaded sentences, start with modifiers, introductory phrases, or clauses, leading to the main subject and verb later in the sentence.

In academic writing, left-branching or front-loaded sentences are generally considered easier to read and more authoritative.

This is because they present the core information—the subject and the verb—at the beginning, making it easier for readers to understand the main point of the sentence.

Front-loading also creates a clear and straightforward sentence structure, which is preferred in academic writing for its clarity and conciseness.

Right-branching or back-loaded sentences, with their more complex and sometimes convoluted structure, can be more challenging for readers to follow and may lead to confusion or misinterpretation.

Take these examples where I’ve highlighted the subject of the sentence in bold. Note that in the right-branching sentences, the topic is front-loaded.

- Right Branching: Researchers found a strong correlation between sleep and cognitive function after analyzing the data from various studies.

- Left-Branching: After analyzing the data from various studies, a strong correlation between sleep and cognitive function was found by researchers.

- The novel was filled with vivid imagery and thought-provoking themes , which captivated the audience from the very first chapter.

- Captivating the audience from the very first chapter, the novel was filled with vivid imagery and thought-provoking themes.

The words you choose to start a paragraph are crucial for setting the tone, establishing context, and ensuring a smooth flow throughout your essay.

By carefully selecting the best words for each type of paragraph, you can create a coherent, engaging, and persuasive piece of writing.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 101 Class Group Name Ideas (for School Students)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Using Logical Reasoning in Academic Writing

The model we were taught in school for writing an effective essay has some good bones: Create a thesis. Present several claims and argue for those statements. Tie those arguments back to the thesis with supporting evidence to show your reader that what you're saying is true. If any of your arguments fall apart, your entire work will unravel faster than the scarf I made during my first attempt at learning to crochet. If you're creating a work of academic writing, you will need to follow a pattern of clearly defined logic to reinforce and support your argument.

Logic refers to the process of making a conclusion under valid laws of inference. Through this process, a writer makes arguments using statements to explain why these arguments are true. Logical reasoning is the act of settling on a viewpoint and then expressing to others why you selected that opinion over all other available conclusions.

Apply logical reasoning in your academic writing, and you'll be on your way to creating a strong conclusion with supporting evidence. Here are some tips on constructing a perfectly logical argument in your work.

Define your thoughts

Before you even start composing your text, clarify your own thoughts on the subject. You already have a solid idea that you want to illustrate for your readers. It makes perfect sense to you, because you have access to all the good arguments, supporting evidence, and gut feelings you've accumulated during your research at the forefront of your brain. Unfortunately, you can't open your brain and instantly share your certainty of an idea with others. This problem is especially apparent every time you have a misunderstanding with another person. You might feel passionate about an idea, but when you try to communicate your point, your mannerisms might portray petulance and impatience, which can cloud the perception of the other person. Maybe you feel frustrated that your significant other leaves the door open, and you are worried that your dog will run away forever. Your approach to the situation can be clouded by your delivery, which is heavy with the emotion connected to the issue, and your significant other can miss your message entirely if it is framed in a way that makes him/her defensive. If we could see a situation from the complete point of view as our friends and neighbors, the world might be a much more peaceful place!

Of course, sadly, the only way to express your thoughts and feelings is through the use of language and expression. While there is no perfect way to bring others into your world to share your thoughts, you can create the best-case scenario by mapping out your idea and why you feel it is true before you begin writing. Write out your idea and the supporting arguments. How do you know they are true? Seeing your points laid out on paper can help you remove your own perspective in a small way and view them as others might. Do your points represent logical connections between ideas, or are you depending on leaps in logic that will be too wide for your readers to navigate?

Gather irrefutable evidence to support your claim

When using logical reasoning, you draw conclusions whose evidence to support the claim creates a guarantee of a specific result. Look for concrete facts backed by studies and expert inquiries. If you are publishing a paper on your own research, aim to represent your work clearly and thoroughly by outlining the steps you took to create a conclusion. Ask yourself these questions:

- At the beginning of your research, what did you think would happen?

- How did you set out to prove/disprove this assertion?

- What result did you observe, and was it in line with your previous expectations?

As most researchers will attest, the greater the scope of your study, the more irrefutable your evidence will be, and you can be more confident that your conclusions can be considered facts.

Avoid logical fallacies

A logical fallacy is false reasoning that leads your argument to become unreliable or untrue. When your readers encounter a logical fallacy, you lose their trust in your argument. Be aware of these fallacies and take measures to avoid them within your argument.

- The bandwagon fallacy: Under this fallacy, you might claim that an idea is true simply because the majority of the people believe it. The common advertising claim , "4 out of 5 dentists prefer this toothpaste" draws on the bandwagon fallacy with the hope that its audience will believe that this toothpaste brand is the best on the market, whereas it is not necessarily true.

- The correlation/causation fallacy: Just because two elements seem to be connected doesn't mean one directly leads to another. For example, if you changed the font on your company website last month, and then website hits were down during that same month, you might apply the correlation/causation fallacy and state that the font was detrimental to business without any other evidence supporting this claim.

- Ignoratio elenchi (Latin for "ignoring refutation"): If your argument has an opposing side (and most do, of course), you will need to address that opposition with convincing logic. This fallacy arises when you respond to a counterargument without properly addressing the point of the argument. Let's say I am presenting the benefits of building a new bike trail in my city. My opponents assert that the city just doesn't have the budget to fund this project, while I claim that the advantages of a bike trail far outweigh any cost incurred. My claim is that cost is irrelevant to the project. In doing so, I fail to present a solution to the lack of money needed to build the path.

- The straw man fallacy: This fallacy arises when you oversimplify your opposing argument and thus misrepresent it, thereby presenting your argument as the more obvious choice in the matter. In the debate on whether schools should implement school uniforms, an opponent of the school uniform might claim, "Schools that enforce dress codes discourage students' individuality." Such an argument dismisses any benefits of the opposing argument and boils down the claim to a simplified form that might not be fully true.

- The anecdotal evidence fallacy: Under this fallacy, instead of applying logical evidence to your argument, you cite a story of one instance in which something happened, seeming to support a claim. Maybe your aunt tried a certain type of dryer sheet and the next day her dryer went up in flames. Does this mean that type of dryer sheet causes people's clothes dryers to ignite? This fallacy is also related to the correlation/causation fallacy.

Consider the opposition