Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Published on October 14, 2022 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Tegan George.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work.

Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research, showing that your paper or dissertation topic is relevant and grounded in established ideas.

In other words, your theoretical framework justifies and contextualizes your later research, and it’s a crucial first step for your research paper , thesis , or dissertation . A well-rounded theoretical framework sets you up for success later on in your research and writing process.

Table of contents

Why do you need a theoretical framework, how to write a theoretical framework, structuring your theoretical framework, example of a theoretical framework, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theoretical frameworks.

Before you start your own research, it’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the theories and models that other researchers have already developed. Your theoretical framework is your opportunity to present and explain what you’ve learned, situated within your future research topic.

There’s a good chance that many different theories about your topic already exist, especially if the topic is broad. In your theoretical framework, you will evaluate, compare, and select the most relevant ones.

By “framing” your research within a clearly defined field, you make the reader aware of the assumptions that inform your approach, showing the rationale behind your choices for later sections, like methodology and discussion . This part of your dissertation lays the foundations that will support your analysis, helping you interpret your results and make broader generalizations .

- In literature , a scholar using postmodernist literary theory would analyze The Great Gatsby differently than a scholar using Marxist literary theory.

- In psychology , a behaviorist approach to depression would involve different research methods and assumptions than a psychoanalytic approach.

- In economics , wealth inequality would be explained and interpreted differently based on a classical economics approach than based on a Keynesian economics one.

To create your own theoretical framework, you can follow these three steps:

- Identifying your key concepts

- Evaluating and explaining relevant theories

- Showing how your research fits into existing research

1. Identify your key concepts

The first step is to pick out the key terms from your problem statement and research questions . Concepts often have multiple definitions, so your theoretical framework should also clearly define what you mean by each term.

To investigate this problem, you have identified and plan to focus on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

Research question : How can the satisfaction of company X’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

2. Evaluate and explain relevant theories

By conducting a thorough literature review , you can determine how other researchers have defined these key concepts and drawn connections between them. As you write your theoretical framework, your aim is to compare and critically evaluate the approaches that different authors have taken.

After discussing different models and theories, you can establish the definitions that best fit your research and justify why. You can even combine theories from different fields to build your own unique framework if this better suits your topic.

Make sure to at least briefly mention each of the most important theories related to your key concepts. If there is a well-established theory that you don’t want to apply to your own research, explain why it isn’t suitable for your purposes.

3. Show how your research fits into existing research

Apart from summarizing and discussing existing theories, your theoretical framework should show how your project will make use of these ideas and take them a step further.

You might aim to do one or more of the following:

- Test whether a theory holds in a specific, previously unexamined context

- Use an existing theory as a basis for interpreting your results

- Critique or challenge a theory

- Combine different theories in a new or unique way

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation. As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

There are no fixed rules for structuring your theoretical framework, but it’s best to double-check with your department or institution to make sure they don’t have any formatting guidelines. The most important thing is to create a clear, logical structure. There are a few ways to do this:

- Draw on your research questions, structuring each section around a question or key concept

- Organize by theory cluster

- Organize by date

It’s important that the information in your theoretical framework is clear for your reader. Make sure to ask a friend to read this section for you, or use a professional proofreading service .

As in all other parts of your research paper , thesis , or dissertation , make sure to properly cite your sources to avoid plagiarism .

To get a sense of what this part of your thesis or dissertation might look like, take a look at our full example .

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Survivorship bias

- Self-serving bias

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

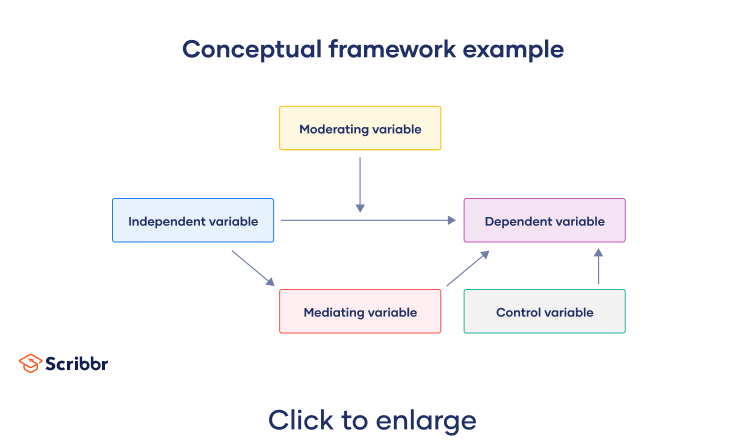

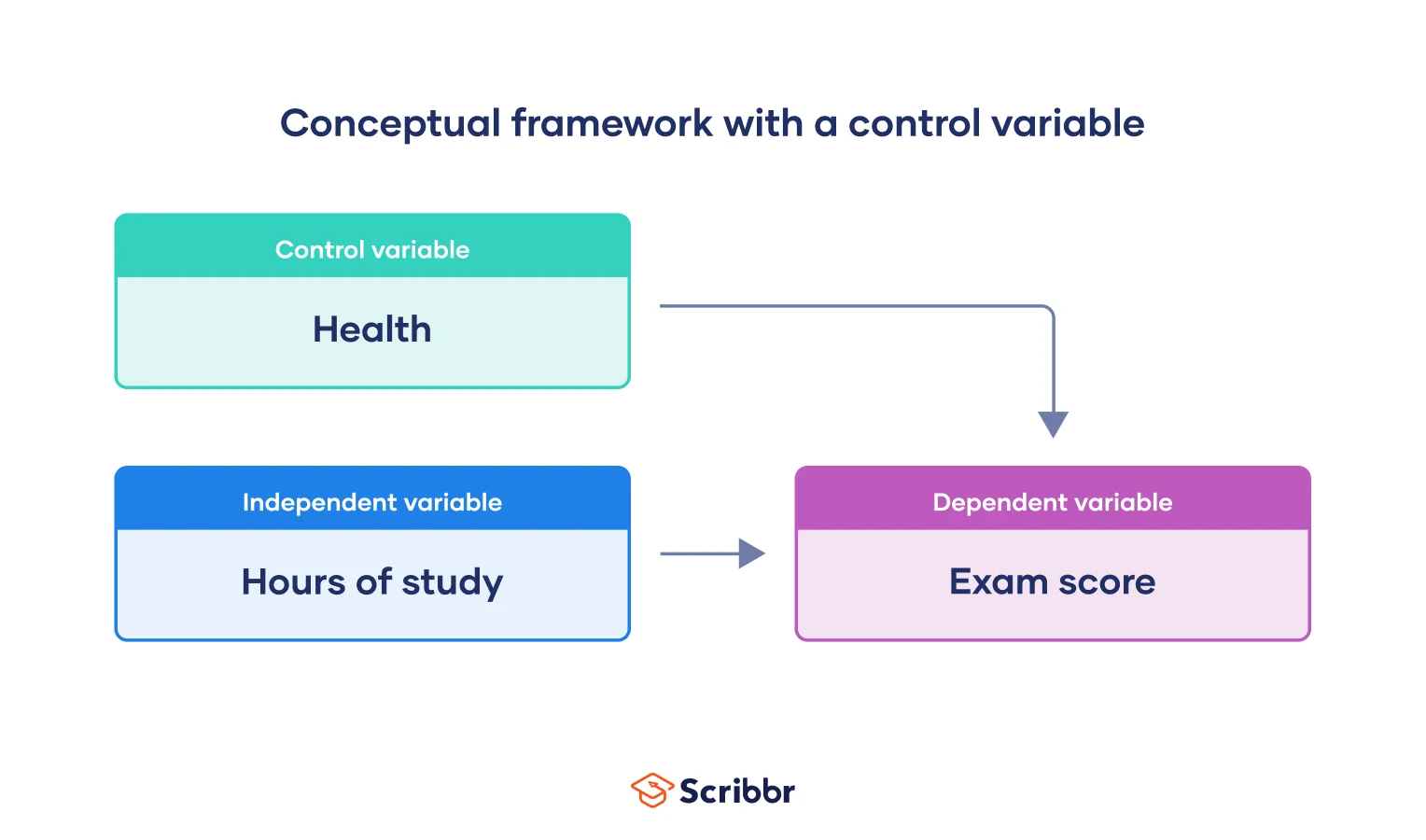

While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work based on existing research, a conceptual framework allows you to draw your own conclusions, mapping out the variables you may use in your study and the interplay between them.

A literature review and a theoretical framework are not the same thing and cannot be used interchangeably. While a theoretical framework describes the theoretical underpinnings of your work, a literature review critically evaluates existing research relating to your topic. You’ll likely need both in your dissertation .

A theoretical framework can sometimes be integrated into a literature review chapter , but it can also be included as its own chapter or section in your dissertation . As a rule of thumb, if your research involves dealing with a lot of complex theories, it’s a good idea to include a separate theoretical framework chapter.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Make a Conceptual Framework

- 6-minute read

- 2nd January 2022

What is a conceptual framework? And why is it important?

A conceptual framework illustrates the relationship between the variables of a research question. It’s an outline of what you’d expect to find in a research project.

Conceptual frameworks should be constructed before data collection and are vital because they map out the actions needed in the study. This should be the first step of an undergraduate or graduate research project.

What Is In a Conceptual Framework?

In a conceptual framework, you’ll find a visual representation of the key concepts and relationships that are central to a research study or project . This can be in form of a diagram, flow chart, or any other visual representation. Overall, a conceptual framework serves as a guide for understanding the problem being studied and the methods being used to investigate it.

Steps to Developing the Perfect Conceptual Framework

- Pick a question

- Conduct a literature review

- Identify your variables

- Create your conceptual framework

1. Pick a Question

You should already have some idea of the broad area of your research project. Try to narrow down your research field to a manageable topic in terms of time and resources. From there, you need to formulate your research question. A research question answers the researcher’s query: “What do I want to know about my topic?” Research questions should be focused, concise, arguable and, ideally, should address a topic of importance within your field of research.

An example of a simple research question is: “What is the relationship between sunny days and ice cream sales?”

2. Conduct a Literature Review

A literature review is an analysis of the scholarly publications on a chosen topic. To undertake a literature review, search for articles with the same theme as your research question. Choose updated and relevant articles to analyze and use peer-reviewed and well-respected journals whenever possible.

For the above example, the literature review would investigate publications that discuss how ice cream sales are affected by the weather. The literature review should reveal the variables involved and any current hypotheses about this relationship.

3. Identify Your Variables

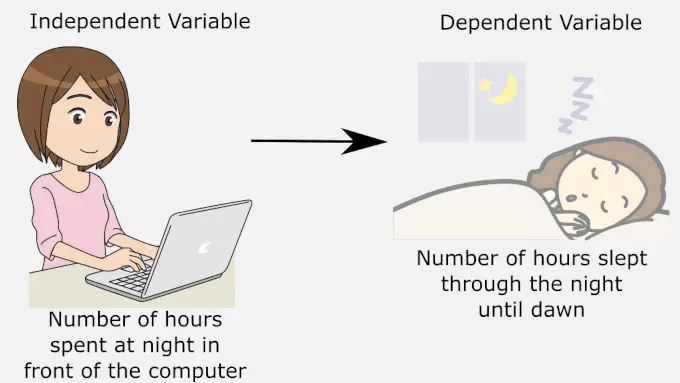

There are two key variables in every experiment: independent and dependent variables.

Independent Variables

The independent variable (otherwise known as the predictor or explanatory variable) is the expected cause of the experiment: what the scientist changes or changes on its own. In our example, the independent variable would be “the number of sunny days.”

Dependent Variables

The dependent variable (otherwise known as the response or outcome variable) is the expected effect of the experiment: what is being studied or measured. In our example, the dependent variable would be “the quantity of ice cream sold.”

Next, there are control variables.

Control Variables

A control variable is a variable that may impact the dependent variable but whose effects are not going to be measured in the research project. In our example, a control variable could be “the socioeconomic status of participants.” Control variables should be kept constant to isolate the effects of the other variables in the experiment.

Finally, there are intervening and extraneous variables.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Intervening Variables

Intervening variables link the independent and dependent variables and clarify their connection. In our example, an intervening variable could be “temperature.”

Extraneous Variables

Extraneous variables are any variables that are not being investigated but could impact the outcomes of the study. Some instances of extraneous variables for our example would be “the average price of ice cream” or “the number of varieties of ice cream available.” If you control an extraneous variable, it becomes a control variable.

4. Create Your Conceptual Framework

Having picked your research question, undertaken a literature review, and identified the relevant variables, it’s now time to construct your conceptual framework. Conceptual frameworks are clear and often visual representations of the relationships between variables.

We’ll start with the basics: the independent and dependent variables.

Our hypothesis is that the quantity of ice cream sold directly depends on the number of sunny days; hence, there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the independent variable (the number of sunny days) and the dependent and independent variable (the quantity of ice cream sold).

Next, introduce a control variable. Remember, this is anything that might directly affect the dependent variable but is not being measured in the experiment:

Finally, introduce the intervening and extraneous variables.

The intervening variable (temperature) clarifies the relationship between the independent variable (the number of sunny days) and the dependent variable (the quantity of ice cream sold). Extraneous variables, such as the average price of ice cream, are variables that are not controlled and can potentially impact the dependent variable.

Are Conceptual Frameworks and Research Paradigms the Same?

In simple terms, the research paradigm is what informs your conceptual framework. In defining our research paradigm we ask the big questions—Is there an objective truth and how can we understand it? If we decide the answer is yes, we may be working with a positivist research paradigm and will choose to build a conceptual framework that displays the relationship between fixed variables. If not, we may be working with a constructivist research paradigm, and thus our conceptual framework will be more of a loose amalgamation of ideas, theories, and themes (a qualitative study). If this is confusing–don’t worry! We have an excellent blog post explaining research paradigms in more detail.

Where is the Conceptual Framework Located in a Thesis?

This will depend on your discipline, research type, and school’s guidelines, but most papers will include a section presenting the conceptual framework in the introduction, literature review, or opening chapter. It’s best to present your conceptual framework after presenting your research question, but before outlining your methodology.

Can a Conceptual Framework be Used in a Qualitative Study?

Yes. Despite being less clear-cut than a quantitative study, all studies should present some form of a conceptual framework. Let’s say you were doing a study on care home practices and happiness, and you came across a “happiness model” constructed by a relevant theorist in your literature review. Your conceptual framework could be an outline or a visual depiction of how you will use this model to collect and interpret qualitative data for your own study (such as interview responses). Check out this useful resource showing other examples of conceptual frameworks for qualitative studies .

Expert Proofreading for Researchers

Whether you’re a seasoned academic or not, you will want your research paper to be error-free and fluently written. That’s where proofreading comes in. Our editors are on hand 24 hours a day to ensure your writing is concise, clear, and precise. Submit a free sample of your writing today to try our services.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

3-minute read

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Conceptual Framework: A Step-by-Step Guide on How to Make One

What is a conceptual framework? How do you prepare one? This article defines the conceptual framework and lists the steps on how to prepare it. A simplified example is added to strengthen the reader’s understanding.

In preparing your research paper as one requirement for your course as an undergraduate or graduate student, you will need to write the conceptual framework of your study. The conceptual framework steers the whole research activity. The conceptual framework serves as a “map” or “rudder” that will guide you towards realizing your study’s objectives or intent.

What, then, is a conceptual framework in empirical research? The next section defines and explains the term.

Table of Contents

Definition of conceptual framework.

A conceptual framework represents the researcher’s synthesis of the literature on how to explain a phenomenon. It maps out the actions required in the study’s course, given the researcher’s previous knowledge of other researchers’ point of view and his or her observations about the phenomenon studied.

The conceptual framework is the researcher’s understanding of how the particular variables in the study connect. Thus, it identifies the variables required in the research investigation. It is the researcher’s “map” in pursuing the investigation.

As McGaghie et al . (2001) put it: The conceptual framework “sets the stage” to present the particular research question that drives the investigation being reported based on the problem statement. The problem statement of a thesis gives the context and the issues that caused the researcher to conduct the study.

The conceptual framework lies within a much broader framework called a theoretical framework . The latter draws support from time-tested theories that embody many researchers’ findings on why and how a particular phenomenon occurs.

I expounded on this definition, including its purpose, in my recent post titled “ What is a Conceptual Framework? Expounded Definition and Five Purposes .”

4 Steps on How to Make the Conceptual Framework

Before you prepare your conceptual framework, you need to do the following things:

Choose your topic

Decide on what will be your research topic. The topic should be within your field of specialization. (Generate your research topic using brainstorming tips ).

Do a literature review

Review relevant and updated research on the theme that you decide to work on after scrutiny of the issue at hand. Preferably use peer-reviewed , and well-known scientific journals as these are reliable sources of information.

Isolate the important variables

Identify the specific variables described in the literature and figure out how these are related. Some research abstracts contain the variables, and the salient findings thus may serve the purpose. If these are not available, find the research paper’s summary.

If the variables are not explicit in summary, get back to the methodology or the results and discussion section and quickly identify the study variables and the significant findings. Read the TSPU Technique to skim articles efficiently and get to the essential points with little fuss.

Generate the conceptual framework

Build your conceptual framework using your mix of the variables from the scientific articles you have read. Your problem statement or research objective serves as a reference for constructing it. In effect, your study will attempt to answer the question that other researchers have not explained yet. Your research should address a knowledge gap .

Example of a Conceptual Framework

Research topic.

Statement number 5 introduced in an earlier post titled How to Write a Thesis Statement will serve as the basis of the illustrated conceptual framework in the following examples.

The youth, particularly students who need to devote a lot of time using their mobile phones to access their course modules, laptops, or desktops, are most affected. Also, they spend time interacting with their mobile phones as they communicate with their friends on social media channels like Facebook, Messenger, and the like.

When free from schoolwork, many students spend their time viewing films on Netflix, YouTube, or similar sites. These activities can affect their sleeping patterns and cause health problems in the long run because light-emitting diode (LED) exposure reduces the number of hours spent sleeping.

Thesis Statement

Related to the students’ activity, we can write the thesis statement thus:

Thesis statement : Chronic exposure to blue light from LED screens (of computer monitors , mobile phones, tablets, and television) deplete melatonin levels, thus reducing the number of sleeping hours among the youth, particularly students who need to work on their academic requirements.

Review of Literature

The literature review supports the thesis statement as among those that catch one’s attention is a paper that warns against the use of LED devices at night. Although we can save a lot of electrical energy by using the efficient LED where the inventors Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura received a Nobel prize in physics in 2014, there is growing evidence that it can cause human health problems, particularly cancer.

Haim & Zubidat (2015) of the Israeli Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Chronobiology synthesized the literature about LEDs. They found out that blue light from the light-emitting diodes (LED) inhibits melatonin production, particularly during active secretion at night. Melatonin is a neuro-hormone that regulates sleep and wake cycles. Also, it can slow down aging and prevent cancer (Srinivasan et al., 2011).

Thus, looking directly at your laptop, mobile phone, or television at night not only can severely damage your eyes but also prevent the achievement of sound sleeping patterns. As a countermeasure, sleep experts recommend limiting the use of digital devices until 8 o’clock in the evening.

Those affected experience insomnia (see 10 Creative Ways on How to Get Rid of Insomnia ); they sleep less than required (usually less than six hours), and this happens when they spend too much time working on their laptops doing some machine learning stuff, monitoring conversations or posts on social media sites using their mobile phones, or viewing the television at night.

Variables Isolated from the Literature

Using the background information backed by evidence in the literature review, we can now develop the study’s paradigm on the effect of LED exposure to sleep. We will not include all the variables mentioned and select or isolate only those factors that we are interested in.

Figure 1 presents a visual representation, the paradigm, of what we want to correlate in this study. It shows measurable variables that can produce data we can analyze using a statistical test such as either the parametric test Pearson’s Product-Moment Correlation or the nonparametric test Spearman Rho (please refresh if you cannot see the figure).

Notice that the variables of the study are explicit in the paradigm presented in Figure 1. In the illustration, the two variables are:

1) the number of hours devoted in front of the computer, and 2) the number of hours slept through the night until dawn.

The former is the independent variable, while the latter is the dependent variable. Both variables are easy to measure. It is just counting the number of hours spent in front of the computer and the number of hours slept through the night in the study subjects.

Assuming that other things are constant during the study’s performance, it will be possible to relate these two variables and confirm that, indeed, blue light emanated from computer screens can affect one’s sleeping patterns. (Please read the article titled “ Do you know that the computer can disturb your sleeping patterns ?” to find out more about this phenomenon). A correlation analysis will show if the relationship is significant.

Related Reading :

- How the conceptual framework guides marketing research

Evolution of a Social Theory as Basis of Conceptual Framework Development

Related to the development of the conceptual framework, I wrote a comprehensive article on how a social theory develops by incisively looking at current events that the world is facing now — the COVID-19 pandemic. It shows how society responds to a threat to its very survival.

Specifically, this article focuses on the COVID-19 vaccine, how it develops and gets integrated into the complex fabric of human society. It shows how the development of the vaccine is only part of the story. A major consideration in its development resides in the supporters of the vaccine’s development, the government, and the recipients’ trust, thus the final acceptance of the vaccine.

Social theory serves as the backdrop or theoretical framework of the more focused or variable level conceptual framework. Hence, the paradigm that I develop at the end of that article can serve as a lens to examine how the three players of vaccine development interact more closely at the variable level. It shows the dynamics of power and social structure and how it unfolds in response to a pandemic that affects everyone.

Check out the article titled “ Pfizer COVID-19 Vaccine: More Than 90% Effective Against the Coronavirus .” This article shall enrich your knowledge of how an abstract concept narrows down into blocks of researchable topics.

Haim, A., & Zubidat, A. E. (2015). LED light between Nobel Prize and cancer risk factor. Chronobiology International , 32 (5), 725-727.

McGaghie, W. C.; Bordage, G.; and J. A. Shea (2001). Problem Statement, Conceptual Framework, and Research Question. Retrieved on January 5, 2015 from http://goo.gl/qLIUFg

Srinivasan, V., R Pandi-Perumal, S., Brzezinski, A., P Bhatnagar, K., & P Cardinali, D. (2011). Melatonin, immune function and cancer. Recent patents on endocrine, metabolic & immune drug discovery , 5 (2), 109-123.

©2015 January 5 P. A. Regoniel

Cite as: Regoniel, P. A. (2015, January 5). Conceptual framework: a step-by-step guide on how to make one. Research-based Articles. https://simplyeducate.me/wordpress_Y/2015/01/05/conceptual-framework-guide/

Related Posts

Statistical sampling: how to determine sample size, the role of internet technology in enhancing research skills.

Outlining a Research Paper: 3 Parts and 7 Easy Steps

About the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel, a faculty member of the graduate school, served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

104 Comments

hallo! I would like to study “the socio-economic and environmental Impact of urban forests on livelihood: The perception of urban residents” how can my conceptual framework be like?

Hello Jesse, there are many free alternatives online if you are diligent enough in finding them. The reason I wrote this article is that in 2015, when I originally wrote it, I could not find an easy-to-understand explanation of the conceptual framework which will help my students. I also have a vague knowledge of the concept at that time, even with the available literature. Hence, I painstakingly gathered all materials I could from online and offline literature, synthesized them, and wrote about the concept in the simplest way I could without losing the essence. Now, I have seen many articles and even videos using the ideas I have rigorously prepared. If you find the tedious work I did irrelevant, then perhaps the ebook is expensive notwithstanding the many expenses on hosting, domain name, time and effort in maintaining the site that I incur in keeping this website online and make this ebook available to everyone.

I read the article how still struggling to come up with a conceptual framework, may you please assist, how should I go about as a new researcher my topic; INVESTIGATE THE DECISION TO TRANSFER NINE (9) FUNCTIONS OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH TO LOCAL GOVERNMENT . Purpose: The purpose of this research is to review the delivery of EHS at the local government with a view to understanding the variation in performance and their causes. questions are: 1.2.1 What factors explain the performance variation in the delivery of EHS across municipalities? 1.2.2 How has devolution of the EH function aided or harmed the delivery of EHS?

Hello Mr. Siyabonga. I think what you want to find out is how environmental health services (EHS) performed at the local government level. In doing so, you need to have a set of indicators of successful transition. How is performance assessed? Once you already have a measure of success, then you need to define which variables in the local government have significantly influenced performance. After you have done so, then you can try to correlate local government characteristics and their performance.

I hope that helps.

My name is Jobson, my research topic is: The scope of Ugandan nurses and midwives in using the nursing process in the care of patients

our topic is Neutrophil and Lymphocyte Ratio as a Diagnostic Biomarker for Kidney Stones (experimental) How do I come up with a conceptual framework? What would be the variables?

My topic: E-commerce Platform for Agricultural and Construction Supplies with e-KYC Identification, Feed Page, and Products Bidding Will you please help me to make Conceptual Framework written with visual representation. thank you so much in advance.

Good day Jomar, I am not so clear about what you want to do. Can you write the objectives of your study? You can read about framing the research objectives here: https://simplyeducate.me/wordpress_Y/2020/03/15/research-objective/

My topic is; Mitigating against Childmaltreatment in earlychildhood through positive parenting: Chronicles of first time parents in XYZ City”

How do I come up with a conceptual framework? What would be variables?

Hello Phathi, Apparently, you are trying to relate parenting and child behavior?

Assessing the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) as a storage information tool in estate management:

How do i come up with a conceptual framework. What would be variables??

Dear Mbuso, Why will you assess the GIS use in estate management? What is it for?

What is a framework? Understanding their purpose, value, development and use

- Articles with Attitude

- Open access

- Published: 14 April 2023

- Volume 13 , pages 510–519, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Stefan Partelow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7751-4005 1 , 2

13k Accesses

4 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Many frameworks exist across the sciences and science-policy interface, but it is not always clear how they are developed or can be applied. It is also often vague how new or existing frameworks are positioned in a theory of science to advance a specific theory or paradigm. This article examines these questions and positions the role of frameworks as integral but often vague scientific tools, highlighting benefits and critiques. While frameworks can be useful for synthesizing and communicating core concepts in a field, they often lack transparency in how they were developed and how they can be applied. Positioning frameworks within a theory of science can aid in knowing the purpose and value of framework use. This article provides a meta-framework for visualizing and engaging the four mediating processes for framework development and application: (1) empirical generalization, (2) theoretical fitting, (3) application, and (4) hypothesizing. Guiding points for scholars and policymakers using or developing frameworks in their research are provided in closing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reflections on Methodological Issues

Looking Back

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The development of ‘frameworks’ is at present probably the most common strategy in the field of natural resources management to achieve integration and interdisciplinarity. Mollinga , 2008

…it is not clear what the role of a scientific framework should be, and relatedly, what makes for a successful scientific framework. Ban and Cox, 2017

Frameworks are important research tools across nearly all fields of science. They are critically important for structuring empirical inquiry and theoretical development in the environmental social sciences, governance research and practice, the sustainability sciences and fields of social-ecological systems research in tangent with the associated disciplines of those fields (Binder et al. 2013 ; Pulver et al. 2018 ; Colding and Barthel 2019 ). Many well-established frameworks are regularly applied to collect new data or to structure entire research programs such as the Ecosystem Services (ES) framework (Potschin-Young et al. 2018 ), the Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF) (McGinnis and Ostrom 2014a ), Earth Systems Governance (ESG) (Biermann et al. 2010 ), the Driver-Impact-Pressure-State-Response (DIPSR) framework, and the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework. Frameworks are also put forth by major scientific organizing bodies to steer scientific and policy agendas at regional and global levels such as the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (Díaz et al. 2015 ) and the Global Sustainable Development Report’s transformational levers and fields (UN 2019 ).

Despite the countless frameworks, it is not always clear how a framework can be developed or applied (Ban and Cox 2017 ; Partelow 2018 ; Nagel and Partelow 2022 ). Development may occur through empirically backed synthesis or by scholars based on their own knowledge, values, or interests. These diverse development pathways do, however, result in common trends. The structure of most frameworks is the identification of a set of concepts and their general relationships — often in the form box-and-arrow diagrams — that are loosely defined or unspecified. This hallmark has both benefits and challenges. On one hand, this is arguably the purpose of frameworks, to structure the basic ideas of theory or conceptual thinking, and if they were more detailed they would be models. On the other hand, there is often a “black box” nature to frameworks. It is often unclear why some sets of concepts and relationships are chosen for integration into frameworks, and others not. As argued below, these choices are often the result of the positionality of the framework’s creators. Publications of frameworks, furthermore, often lack descriptions of their value and potential uses compared to other frameworks or analytical tools that exist in the field.

Now shifting focus to how frameworks are applied. Some frameworks provide measureable indicators as the key variables in the framework, but many only suggest general concepts. This creates the need to link concepts and their relationships to data through other more tangible indicators. Methods to measure such indicators will also be needed in new empirical studies. These methodological and study design steps necessary to associate data to framework concepts is often referred to as “operationalizing” a framework. However, without guidance on how to do this, scholars are often left with developing their own strategies, which can lead to heterogeneous and idiosyncratic methods and data. These challenges can be referred to as methodological gaps (Partelow 2018 ), where the details of how to move from concept to indicator to measurement to data transformation, are not always detailed in a way that welcomes replicability or learning. This is not necessarily a problem if the purpose of a framework is to only guide the analysis of individual cases or synthesis activities in isolation, for example to inform local management, but it hinders meta-analyses, cross-case learning and data interpretability for others.

In this article, a brief overview of framework definitions and current synthesis literature are reviewed in the “ What is a framework? ” section. This is coupled with the argument that frameworks often lack clarity in their development and application because their positioning within a theory of science is unclear. In the “ Mechanisms of framework development and use: a meta-framework ” section, a meta-framework is proposed to assist in clarifying the four major levers with which frameworks are developed and applied: (1) empirical generalization, (2) theoretical fitting, (3) hypothesizing, and (4) application. The meta-framework aims to position individual frameworks into a theory of science, which can enable scholars to take a conceptual “step back” in order to view how their engagement with a framework contributes to their broader scientific goal and field. Two case studies of different frameworks are provided to explore how the meta-framework can aid in comparing them. This is followed by a discussion of what makes a good framework, along with explicit guiding points for the use of frameworks in research and policy practice.

What is a framework?

The definition and purpose of a framework is likely to vary across disciplines and thematic fields (Cox et al. 2016 ). There is no universal definition of a framework, but it is useful to provide a brief overview of different definitions for orientation. The Cambridge Dictionary states that frameworks are “a supporting structure around which something can be built; a system of rules, ideas, or beliefs that is used to plan or decide something.” Schlager ( 2007 , 293) states that “frameworks provide a foundation for inquiry,” and Cumming ( 2014 , 5) adds that this “does not necessarily depend on deductive logic to connect different ideas.” Importantly, Binder et al., ( 2013 , 2) note that “a framework provides a set of assumptions, concepts, values and practices,” emphasizing the normative or inherently subjective logic to framework development. A core theme being plurality and connectivity. Similarly, McGinnis and Ostrom ( 2014a , 1) define frameworks as “the basic vocabulary of concepts and terms that may be used to construct the kinds of causal explanations expected of a theory. Frameworks organize diagnostic, descriptive, and prescriptive inquiry.” In a review comparing ten commonly used frameworks in social-ecological systems (SES) research, Binder et al., ( 2013 , 1) state that frameworks are useful for developing “a common language, to structure research on SES, and to provide guidance toward a more sustainable development of SES.” In a similar review, Pulver et al., ( 2018 , 1) suggest that frameworks “assist scholars and practitioners to analyze the complex, nonlinear interdependencies that characterize interactions between biophysical and social arenas and to navigate the new epistemological, ontological, analytical, and practical horizons of integrating knowledge for sustainability solutions.” It is important to recognize that the above claims often suggest the dualistic or bridging positions held by frameworks, in both theory building and for guiding empirical observations. However, there is relatively little discussion in the above literature on how frameworks act as bridging tools within a theory of science or how frameworks add value as positioning tools in a field.

Every framework has a position, meaning it is located within a specific context of a scientific field. As positioning tools, frameworks seem to “populate the scientist’s world with a set of conceptual objects and (non-causal) relationships among them,” shaping (and sometimes limiting) the way we think about problems and potential solutions (Cox et al. 2016 , 47). Thus, using a specific framework helps in part to position the work of a researcher in a field and its related concepts, theories and paradigms.

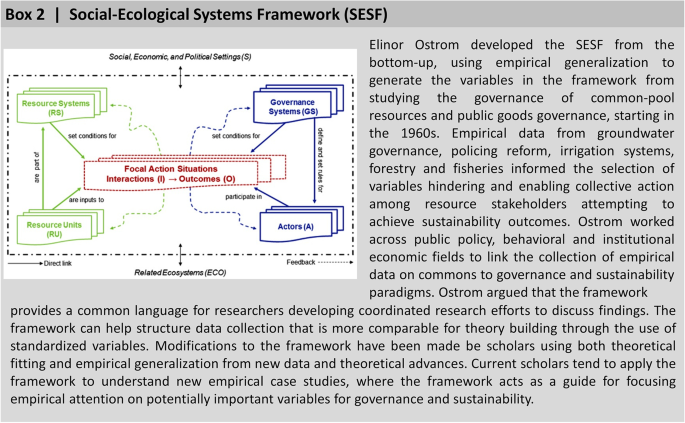

Four factors can be considered to evaluate the positioning of a framework: (a) who developed it, (b) the values being put forth by those researchers, (c) the research questions engaged with, and (d) the field in which it is embedded. For example, the Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF) (Ostrom 2009 ) was developed by (a) Elinor Ostrom who developed the framework studying common-pool resource and public goods governance from the 1960s until the 2000s. Ostrom’s overall goal was (b) to examine the hindering and enabling conditions for governance to guide the use and provision common goods towards sustainability outcomes. Her primary research questions (c) related to collective action theory, unpacking how and why people cooperate with each other or not. The field her work is embedded in (d) is an interdisciplinary mix between public policy, behavioral and institutional economics. Scholars who use Ostrom’s SESF today, carry this history with them and therefore position themselves, whether implicitly or explicitly, as part of this research landscape as systems thinkers and interdisciplinarians, even if they have other scholarly positions.

Frameworks are positioned within a theory of science. Understanding this positioning can guide scholars in comprehending how their engagement with frameworks contributes to the overall advancement of their field. To do this, taking a conceptual “step back” is necessary, to distinguish between different levels of theory in science. From the conceptually broadest to the most empirically specific, we can identify the following levels of theory: paradigms, frameworks, specific theories, models/archetypes and cases (Table 1 ). Knowledge production processes flow up and down these levels of theory. For example, as argued by Kuhn ( 1962 ), the purpose of a scientific field is to advance its paradigm. Thus, the study of empirical observations (e.g., case studies) — and the development of models or theories resulting from those data — are aimed at advancing the overarching paradigm. Such paradigms could be conservation, democracy, sustainable development or social-ecological systems.

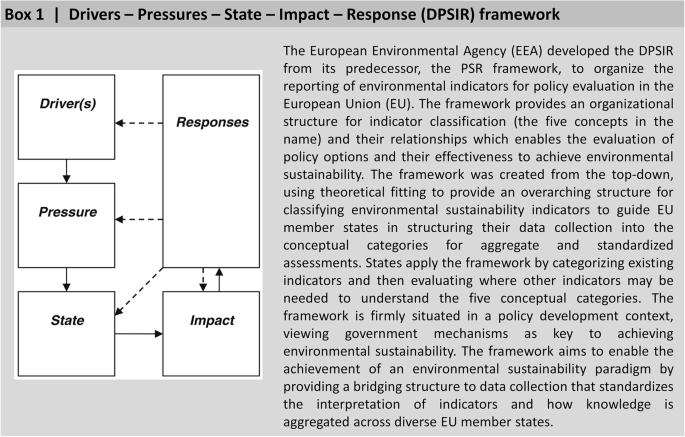

There is a need to connect cases, models and specific theory up to the overall paradigms of a field to make aggregate knowledge gains. Here, the role of frameworks becomes more clear, as bridging tools that enable connections between levels of knowledge. From the top down, frameworks can specify paradigms with more tangible conceptual features and relationships, which can then guide empirical inquiry. For example, the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework (Smeets and Weterings 1999 ; Ness, Anderberg, and Olsson 2010 ) specifies how to evaluate policy options and their effects by focusing on the five embedded concepts in a relational order. Scholars can then generate more specific indicators and methods to measure the five specified features of the framework, and their relationships, to generate empirical insights that now have a direct link to the paradigm of sustainable policy development via the framework.

Furthermore, frameworks can also emerge from the bottom up, by distilling empirical data across cases and thus creating a knowledge bridge of more specified conceptual features and relationships that connect to a paradigm. In both top-down and bottom-up mechanism, frameworks can play a vital role in synthesizing and communicating ideas among scholars in a field — from empirical data to a paradigm. A challenge may be, however, that multiple frameworks have emerged attempting to specify the core conceptual features and relationships in a paradigm. A mature scientific field is likely to have many frameworks to guide research and debate. There is, however, a lack of research and tools available to compare frameworks and their added value.

Beyond their use as positioning tools, frameworks make day-to-day science easier. They can guide researchers in designing new empirical research by indicating which core concepts and relationships are of interest to be measured and compared. Scientific fields also need common fires to huddle around, meaning that we need reference points to initiate scholarly debates, coordinate disparate empirical efforts and to communicate findings and novel advancements through a common language (McGinnis and Ostrom 2014a ; Ban and Cox 2017 ). As such, frameworks are useful for synthesis research, focusing the attention of reviews and meta-analyses around core sets of concepts and relationships.

There is, however, a tension between frameworks that aim to capture complexity and those that aim to simplify core principles. Complexity oriented frameworks often advance systems thinking at the risk of including too many variables. They often have long lists of variables which makes empirical orientation and synthesis difficult. On the other hand, simplification frameworks face the challenge of leaving important things out, with the benefit of clarifying what may be important and giving clear direction.

From a more critical perspective, the “criteria for comparing frameworks are not well developed,” (Schlager, 2007 , 312), and the positionality of frameworks has not been rigorously explored outside of smaller studies. Nonetheless, numerous classifications or typologies of frameworks within specific fields have been suggested (Table 2 ), although not with reference to positionality (Spangenberg 2011 ; Binder et al. 2013 ; Cumming 2014 ; Schlager 2007 ; Ness et al. 2007 ; Potschin-Young et al. 2018 ; Cox et al. 2021 ; Louder et al. 2021 ; Chofreh and Goni 2017 ; Alaoui et al. 2022 ; Tapio and Willamo 2008 ). These studies point to the question of: what makes a good framework? Are there certain quality criteria that make some frameworks more useful than others? There has undoubtedly been a rise in the number of frameworks, but as expressed by Ban and Cox ( 2017 , 2), “it is not clear what the role of a scientific framework should be, and relatedly, what makes for a successful scientific framework. Although there are many frameworks […] there is little discussion on what their scientific role ought to be, other than providing a common scientific language.” The meta-framework presented below serves as a tool for answering these questions and provides guidance for developing and implementing frameworks in a range of settings.

Mechanisms of framework development and use: a meta-framework

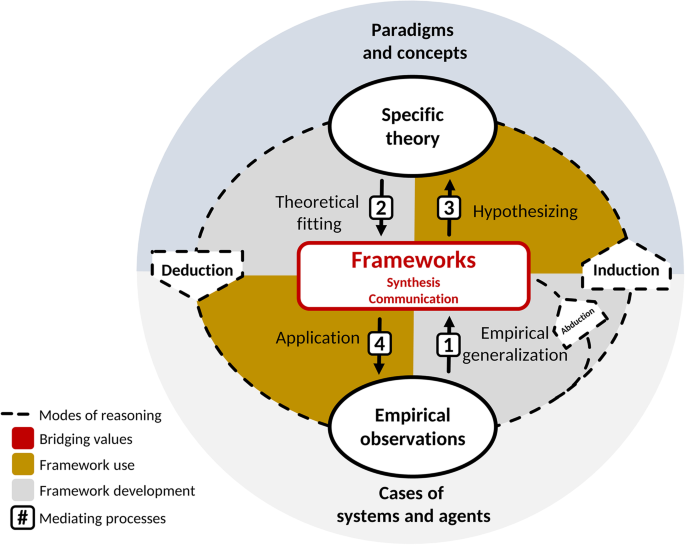

This section presents a meta-framework detailing the mechanisms of framework development and use (Fig. 1 ). The meta-framework illustrates the role of frameworks as bridging tools for knowledge synthesis and communication. Therefore, the purpose of the meta-framework is to demonstrate how the mechanisms of framework development and use act as levers of knowledge flow across levels within a theory of science, doing so by enabling the communication and synthesis of knowledge. Introducing the meta-framework has two parts, outlined below.

A meta-framework outlining the central role frameworks play in scientific advancement through their development and use. In the center, frameworks provide two core bridging values: knowledge synthesis and knowledge communication. Three modes of logical reasoning contribute to framework development: induction, deduction and abduction. Frameworks are used and developed through four mediating processes: (1) empirical generalization, (2) theoretical fitting, (3) application, and (4) hypothesizing

First, the meta-framework visualizes the levels along the scale of scientific theory including paradigms, frameworks, specific theory and empirical observations, introduced above. Along this scale, three mechanisms of logical reasoning are typical: induction, deduction, and abduction. Induction is a mode of logical reasoning based on sets of empirical observations, which, when patterns within those observations emerge, can inform more generalized theory formation. Induction, in its pure form, is reasoning without prior assumptions about what we think is happening. In contrast, deduction is a mode of logical reasoning based on testing a claim or hypothesis, often based on a body of theory, against an observation to infer whether or not a claim is true. In contrast to induction, which always leads to probable or fuzzy conclusions, deductive logic provides true or false conclusions. A third mode of logical reasoning is abduction. Abduction starts with a single or limited set of observations, and assumes the most likely cause as a conclusion. Abduction can only provide probable conclusions. Knowledge claims from all three modes of logical reasoning are part of the nexus of potential framework creation or modification.

Second, the meta-framework has four iterative mediating processes that directly enable the development and/or application of frameworks (Fig. 1 ). Two of the four mediating processes relate to framework development: (1) empirical generalization and (2) theoretical fitting. The other two relate to framework application: (3) hypothesizing, and (4) application (Fig. 1 , Table 3 ). The details of the specific mediating pathways are outlined in Table 3 , including the processes involved in each. There are numerous potential benefits and challenges associated with each (Table 3 ).

The value of a meta-framework

The presented meta-framework (Fig. 1 ) allows us to assess the values different frameworks can provide. If a framework provides a novel synthesis of key ideas or new developments in a field, and communicates those insights well in its composition, it likely adds notable value. If a framework coordinates scientific inquiry across the 1 or more of the four mediating processes, it likely acts as an important gatekeeper and boundary object for what may otherwise be disparate or tangential research. If it contributes substantial advances in 3 or 4 of the mediating processes, the value of the framework is likely higher.

The meta-framework can further help identify the positioning of framework such as the type of logical reasoning processes used to create it, as well as help clarify the role of a framework along the scale of knowledge production (i.e., from data to paradigm). It might be clear, for example, what paradigm or specific theory a framework contributes to. The meta-framework can add value by guiding the assessment of how frameworks fit into the bigger picture of knowledge contribution in their field. Furthermore, many scholars and practitioners are interested in developing new frameworks. The meta-framework outlines the mechanisms that can be considered in creating the framework as well as help developers of new frameworks communicate how their frameworks add value. For example, to link empirical data collection to theoretical work in their field.

The meta-framework can help compare frameworks, to assess strengths and weaknesses in terms of their positioning and knowledge production mechanisms. It can also help elucidate the need for, or value of, new frameworks. This challenge is noted by Cumming ( 2014 , 18) in the field of social-ecological systems, reflecting that “the tendency of researchers to develop “new” frameworks without fully explaining how they relate to other existing frameworks and what new elements they bring to the problem is another obvious reason for the lack of a single dominant, unifying framework.” To showcase such as comparison, two brief examples are provided. The first example features the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response (DPSIR) framework developed by the European Environmental Agency (EEA) (Box 1 ) (Smeets and Weterings 1999 ; Ness, Anderberg, and Olsson 2010 ). The DPSIR framework exemplifies a framework developed from the top-down (theoretical fitting) approach, to better organize the policy goal and paradigm of environmental sustainability to the indicators collected by EU member states. The second example highlights the Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF) developed by Elinor Ostrom (Box 2 ) (Ostrom 2009 ; McGinnis and Ostrom 2014a ). The SESF exemplifies a framework developed from the bottom up (empirical generalization) to aggregate data into common variables to enable data standardization and comparison towards theory building to improve environmental governance. In the case examples (Box 1 ; Box 2 ), we can see the value of both frameworks from different perspectives. The examples briefly illustrate how the positionality of each framework dictates how others use them to produce knowledge towards a paradigm. In the case of the DPSIR framework, from the top-down towards a policy goal, and with the SESF, from the bottom-up towards a theoretical goal.

Drivers – Pressures – State – Impact - Response (DPSIR) framework

Social-Ecological Systems Framework (SESF)

Discussion and directions forward

Frameworks are commons objects to huddle around in academic and practitioner communities, providing identity and guiding our effort. They focus scholarly attention on important issues, stimulate cognitive energy and provide fodder for discussion. However, reflection on the role and purpose of the frameworks we use needs to be a more common practice in science. The proposed meta-framework aims to showcase the role of frameworks as boundary objects that connect ideas and concepts to data in constructive and actionable ways, enabling knowledge to be built up and aggregated within scientific fields through using common languages and concepts (Mollinga 2008 ; Klein 1996 ).

Boundary objects such as frameworks can be especially important for inter- and transdisciplinary collaboration, where there may be few prior shared points of conceptual understanding or terminology beyond a problem context. Mollinga ( 2008 , 33) reflects that “frameworks are typical examples of boundary objects, building connections between the worlds of science and that of policy, and between different knowledge domains,” and that “the development of frameworks is at present probably the most common strategy in the field of natural resources management to achieve integration and interdisciplinarity,” (Mollinga, 2008 , 31). They are, however, critically important for both disciplinary specific fundamental research, as well as for bridging science-society gaps through translating often esoteric academic concepts and findings into digestible and often visual objects. For example, the DPSIR framework (Box 1 ) attempts to better organize the analysis of environmental indicators for policy evaluation processes in the EU. Furthermore, Partelow et al., ( 2019 ) and Gurney et al., ( 2019 ) both use Ostrom’s SESF (Box 2 ) as a boundary object at the science-society interface to visually communicate systems thinking and social-ecological interactions to fishers and coastal stakeholders involved in local management decision-making.

An important feature of frameworks is that the very contestation over their nature is perhaps their main value. A framework can only be an effective boundary object if it catalyzes deliberation and scholarly debate — thus contestation over what it is and its value is seeded into the toolbox and identity of a scholarly field. Although most frameworks are likely to have shortcomings, flaws or controversial features, the fact that they motivate engagement around common problems and stimulate scholarly engagement is a value of its own. In doing so, frameworks often become symbols of individual and community identity in contested spaces. This is evidenced in how frameworks are often used to stamp our research as valid, relevant and important to the field, even if done passively. Citing a framework both communicates the general purpose of what a scholar is attempting to achieve to others, and orients science towards a common synthetic object for future knowledge synthesis and debate. These positioning actions are essential for science and practitioner communities to understand a research or policy project, its aims and assumptions. Historically, disciplines have provided this value – signaling the problems, methods and theories one is likely to engage with. Frameworks can act as tools for bridging disciplines, helping to catalyze interdisciplinary engagement (Mollinga 2008 ; Klein 1996 ). As many scientific communities shift focus towards solving real-world problems (e.g., climate change, gender equality), tools that can help scientists’ cooperate and communicate, such as a framework, will continue to play a vital role in achieving knowledge co-production goals.

Guiding points for framework engagement

An aim of this article is not only to reflect on the purpose, value and positioning of frameworks, but to provide some take-away advice for engaging with frameworks in current or future work. Over the course of this article, the question of “What makes a good framework?” has been explored. The meta-framework outlines mechanisms of useful frameworks and can help understand the positioning of frameworks. Nonetheless, more detailed guiding points can be specified for both the use and development of frameworks going forward. A series of guiding points are outlined in Table 4 , generated from the literature cited throughout this article, feedback from colleagues and personal experiences applying and developing numerous frameworks. The guiding points focus on the two types of mediating processes, framework development and use (Table 4 ).

In conclusion, we need to know our academic tools in order make the best use of them in our own research, practice and knowledge communities. Frameworks have gained substantial popularity for the communication and synthesis of academic ideas, and as tools we all have the ability to create and perhaps the responsibility to steward. However, frameworks have struggled to find roots in a theory of science which grounds their contributions in relation to other scientific tools such as models, specific theories and empirical data. There is also a lack of discussion about what makes a good framework and how to apply frameworks in a way to makes those applications of integrative value to an overall community of scholars positioned around it. The meta-framework provided in this article offers insights into how to understand the purpose and positionality of frameworks, as well as the mechanisms for understanding the creation and application of frameworks. The meta-framework further allows for the comparison of frameworks to assess their value.

Alaoui A, Barão L, Ferreira CSS, Hessel R (2022) An Overview of sustainability assessment frameworks in agriculture. Land 11(4):1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040537

Article Google Scholar

Ban NC, Cox M (2017) Advancing social-ecological research through teaching: summary, observations, and challenges. Ecol Soc 22(1):1–3

Biermann F, Betsill MM, Gupta J, Kanie N, Lebel L, Liverman D, Schroeder H, Siebenhüner B, Zondervan R (2010) Earth system governance: a research framework. Int Environ Agreem Polit 10(4):277–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9137-3

Binder CR, Hinkel J, Bots PWG, Pahl-Wostl C (2013) Comparison of Frameworks for analyzing social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc 18(4):26. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05551-180426

Chofreh AG, Goni FA (2017) Review of frameworks for sustainability implementation. Sustain Dev 25(3):180–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1658

Colding J, Barthel S (2019) Exploring the social-ecological systems discourse 20 years later. Ecol Soc 24(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/es-10598-240102

Cox M, Gurney GG, Anderies JM, Coleman E, Darling E, Epstein G, Frey UJ (2021) Lessons learned from synthetic research projects based on the ostrom workshop frameworks. Ecol Soc 26(1)

Cox M, Villamayor-tomas S, Epstein G, Evans L, Ban NC, Fleischman F, Nenadovic M, Garcia-lopez G (2016) Synthesizing theories of natural resource management and governance. Glob Environ Chang 39(January):45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.011

Cumming GS (2014) Theoretical Frameworks for the analysis of social-ecological systems. In: Sakai S, Umetsu C (eds) Social-Ecological Systems in Transition . Springer, Japan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54910-9

Chapter Google Scholar

Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A et al (2015) The IPBES conceptual framework - connecting nature and people. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 14:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002

Gurney GG, Darling ES, Jupiter SD, Mangubhai S, McClanahan TR, Lestari P, Pardede S et al (2019) Implementing a social-ecological systems framework for conservation monitoring: lessons from a multi-country coral reef program. Biol Conserv 240(August). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108298

Kuhn T (1962) The structure of scientific revolutions (University of Chicago Press)

Klein JT (1996) Crossing boundaries: knowledge, disciplinarities, and interdisciplinarities . University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville and London

Google Scholar

Louder E, Wyborn C, Cvitanovic C, Bednarek AT (2021) A Synthesis of the frameworks available to guide evaluations at the interface of environmental science on policy and practice. Environ Sci Policy 116(July 2020):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.12.006

McGinnis MD, Ostrom E (2014a) Social-Ecological system framework: initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol Soc 19(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06387-190230

Mollinga PP (2008) In: Evers H-D, Gerke S, Mollinga P, Schetter C (eds) The rational organisation of dissent: boundary concepts, boundary objects and boundary settings in the interdisciplinary Study of Natural Resources Management. University of Bonn, Bonn

Nagel B, Partelow S (2022) A methodological guide for applying the ses framework: a review of quantitative approaches. Ecol Soc

Ness B, Anderberg S, Olsson L (2010) Structuring problems in sustainability science: the multi-Level DPSIR framework. Geoforum 41(3):479–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.12.005

Ness B, Urbel-Piirsalu E, Anderberg S, Olsson L (2007) Categorising tools for sustainability assessment. Ecol Econ 60(3):498–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.07.023

Ostrom E (2009) A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325(5939):419–422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133

Article CAS Google Scholar

Partelow S (2018) A review of the social-ecological systems framework: applications, methods, modifications and challenges. Ecol Soc

Partelow S, Fujitani M, Soundararajan V, Schlüter A (2019) Transforming the social-ecological systems framework into a knowledge exchange and deliberation tool for comanagement. Ecol Soc 24(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10724-240115

Potschin-Young M, Haines-Young R, Görg C, Heink U, Jax K, Schleyer C (2018) Understanding the role of conceptual frameworks: reading the ecosystem service cascade. Ecosyst Serv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.05.015

Pulver S, Ulibarri N, Sobocinski KL, Alexander SM, Johnson ML, Mccord PF (2018) Frontiers in socio-environmental research: components, connections, scale, and context. Ecol Soc 23(3)

Schlager E (2007) A Comparison of frameworks, theories, and models of policy processes. In: Sabatier PA (ed) Theories of the Policy Process , 1st edn. Routledge, pp 293–319

Smeets E, Weterings R (1999) Environmental indicators: typology and overview. In: Bosch P, Büchele M, Gee D (eds) European Environment Agency (EEA) , vol 50. European Environment Agency, Copenhagan

Spangenberg JH (2011) Sustainability Science: a review, an analysis and some empirical lessons. Environ Conserv 38(3):275–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892911000270

Tapio P, Willamo R (2008) Developing Interdisciplinary environmental frameworks. Ambio 37(2):125–133. https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[125:DIEF]2.0.CO;2

UN (2019) Independent Group of Scientists appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. United Nations, New York

Download references

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michael Cox and Achim Schlüter for their helpful feedback on previous versions of the manuscript and the ideas within it. I am grateful to the Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT) in Bremen, and the Center for Life Ethics at the University of Bonn for support.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (ZMT), Bremen, Germany

Stefan Partelow

Center for Life Ethics, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stefan Partelow .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declares that he has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Partelow, S. What is a framework? Understanding their purpose, value, development and use. J Environ Stud Sci 13 , 510–519 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-023-00833-w

Download citation

Accepted : 29 March 2023

Published : 14 April 2023

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-023-00833-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Theory of science

- Methodology

- Social science

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on 18 March 2024.

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualise your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

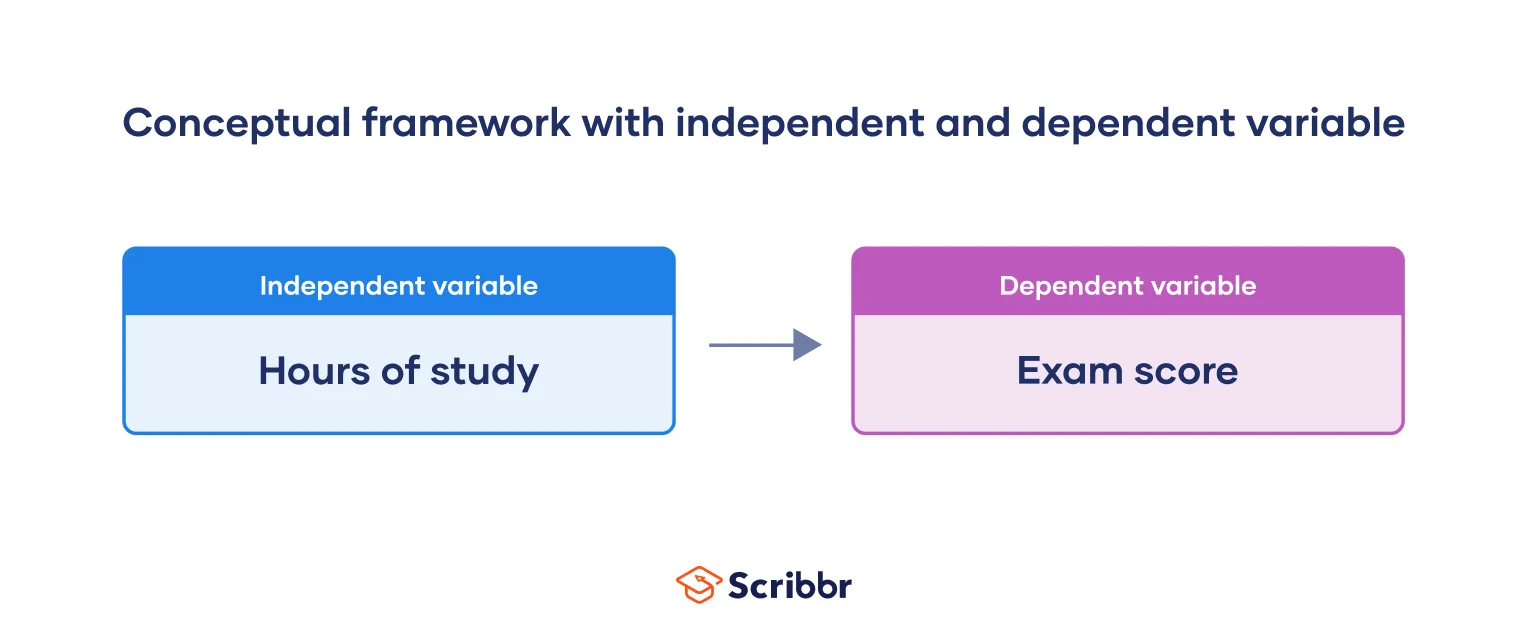

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, ‘hours of study’, is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, ‘exam score’, is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (‘hours of study’).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualising your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

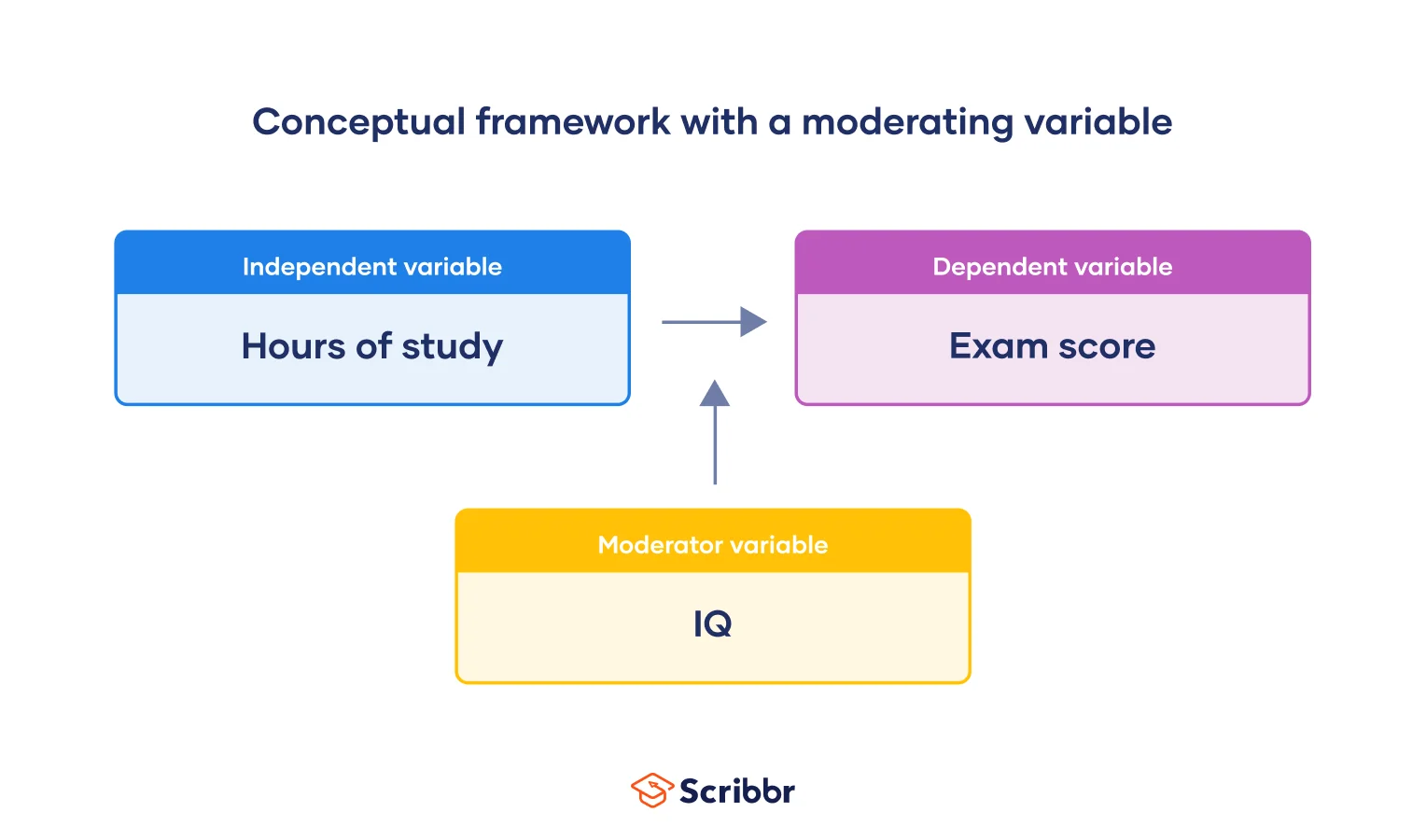

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the ‘effect’ component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator ‘IQ’. Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable ‘hours of study’ has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

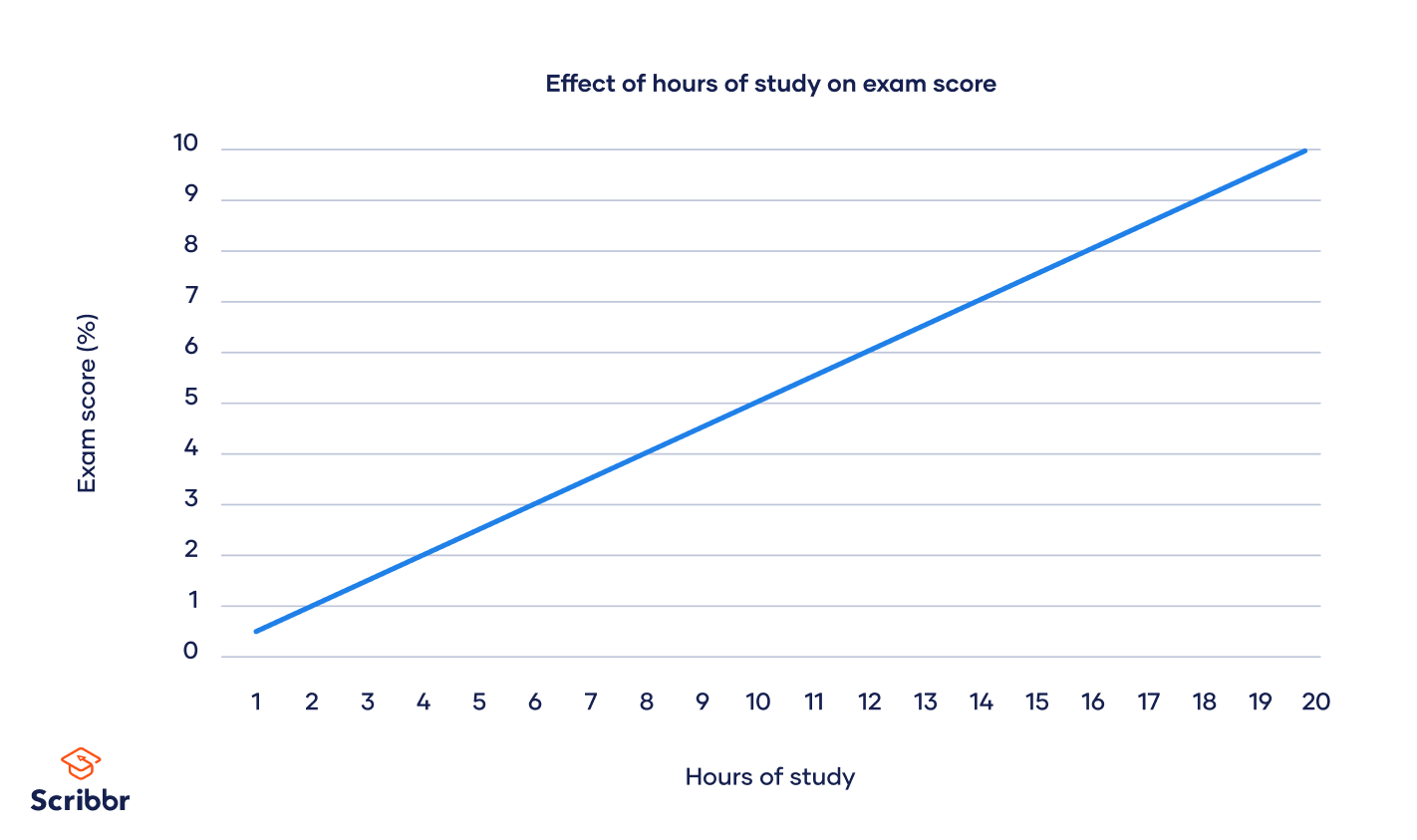

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

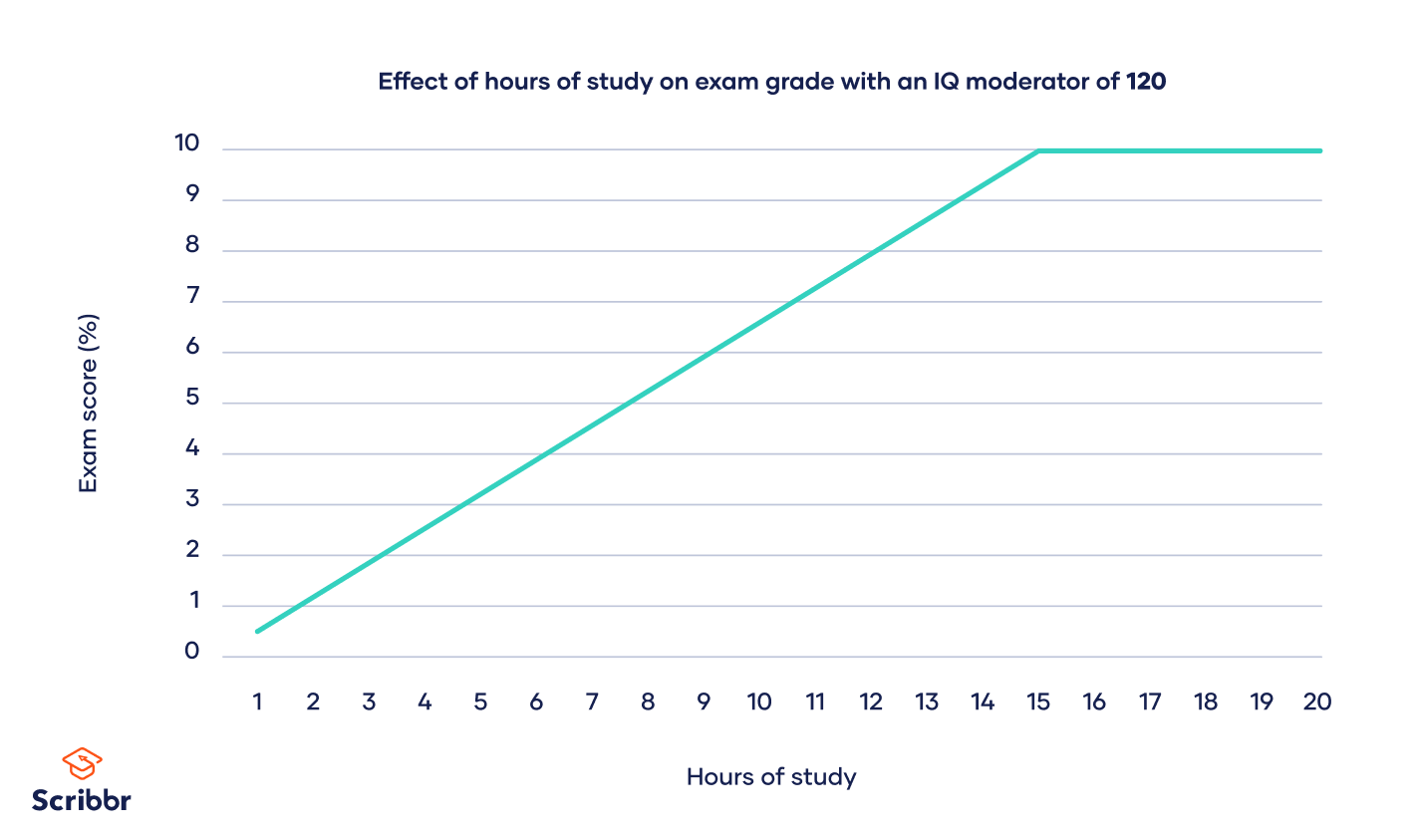

But the graph looks different when we add our ‘IQ’ moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

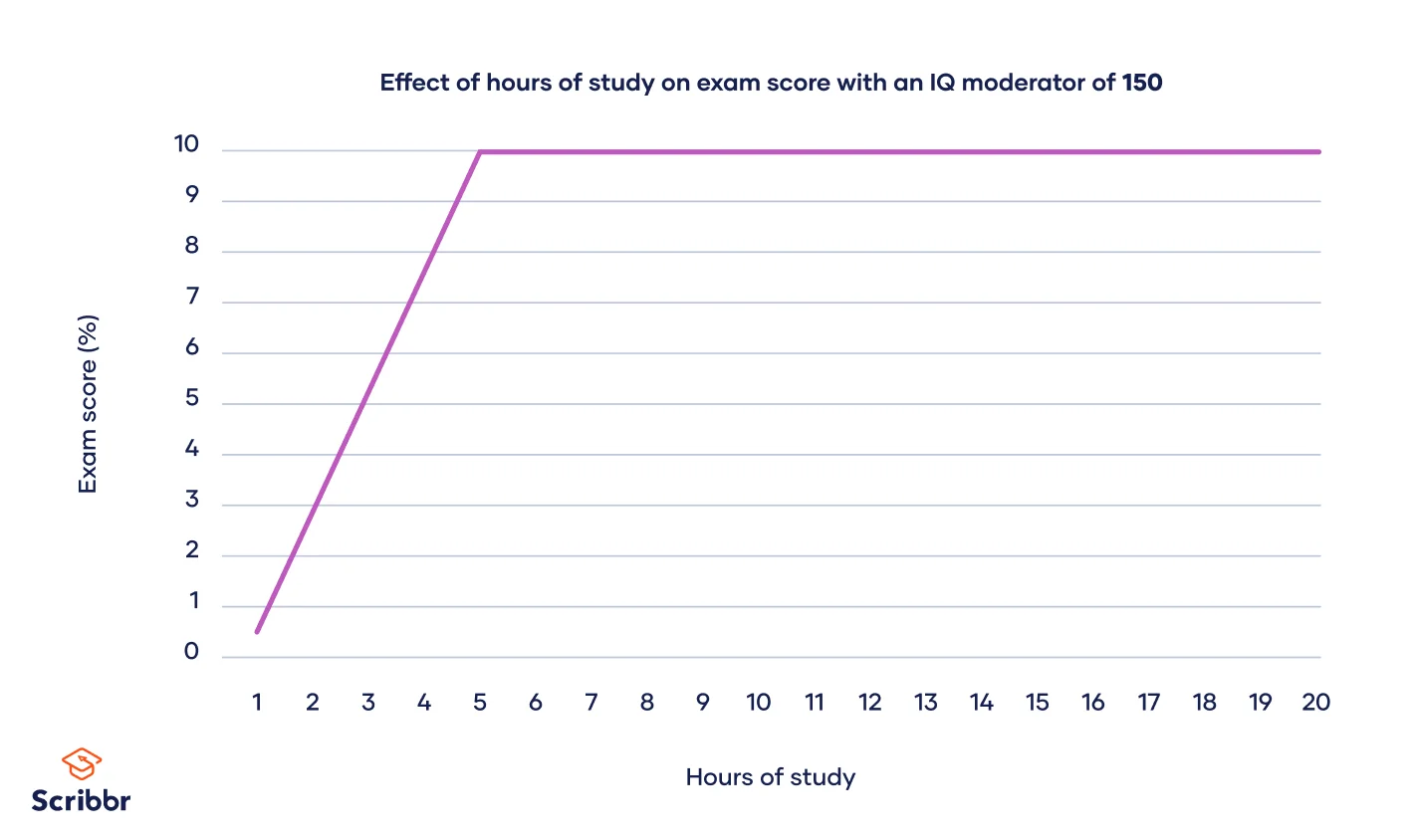

Below, the value of the ‘IQ’ moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

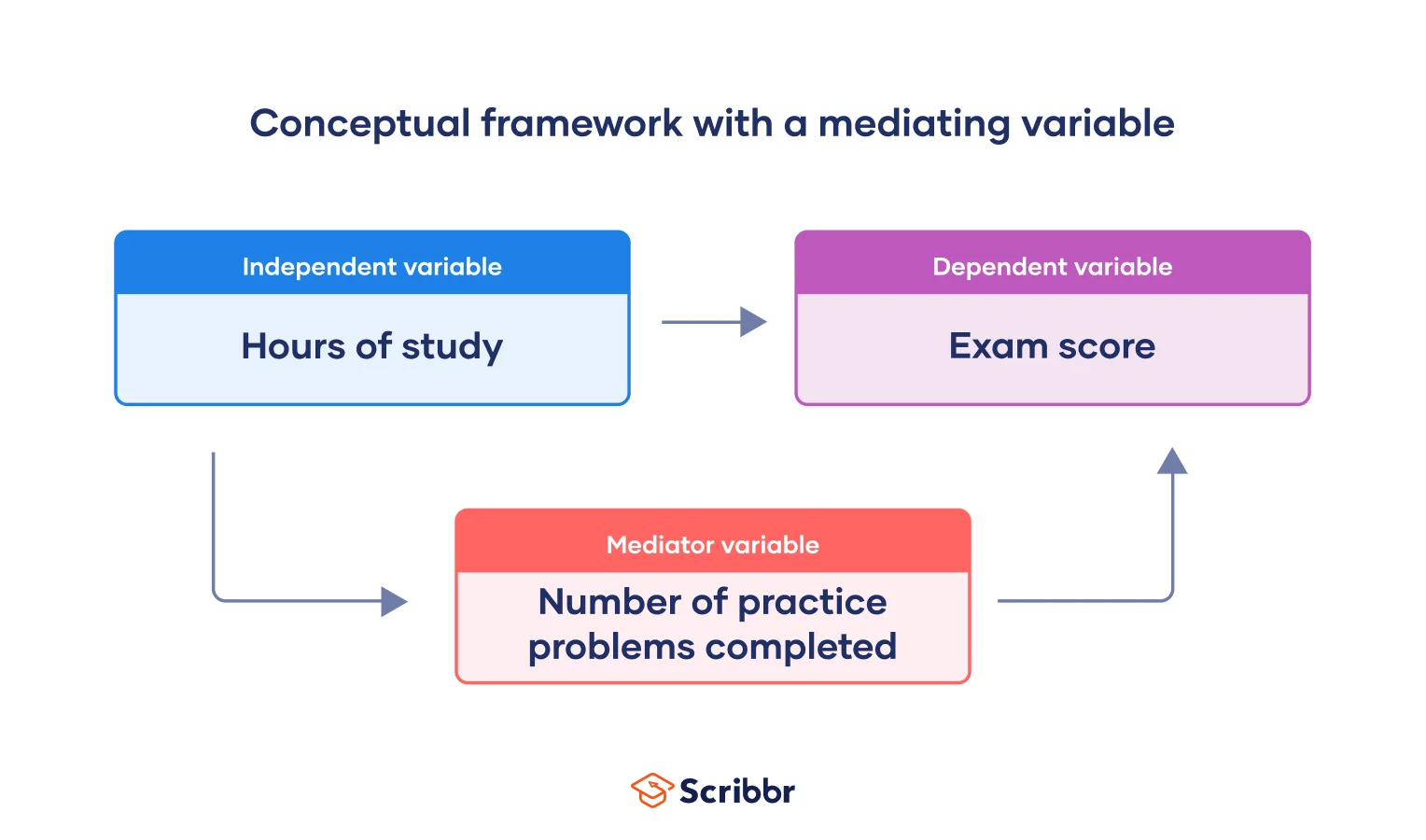

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

No. The value of a dependent variable depends on an independent variable, so a variable cannot be both independent and dependent at the same time. It must be either the cause or the effect, not both.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/conceptual-frameworks/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Mediator vs moderator variables | differences & examples, independent vs dependent variables | definition & examples, what are control variables | definition & examples.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A theoretical framework guides the research process like a roadmap for the research study and helps researchers clearly interpret their findings by providing a structure for organizing data and developing conclusions. A theoretical framework in research is an important part of a manuscript and should be presented in the first section. It shows ...

Developing a conceptual framework in research. Step 1: Choose your research question. Step 2: Select your independent and dependent variables. Step 3: Visualize your cause-and-effect relationship. Step 4: Identify other influencing variables. Frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A theoretical framework is a foundational review of existing theories that serves as a roadmap for developing the arguments you will use in your own work. Theories are developed by researchers to explain phenomena, draw connections, and make predictions. In a theoretical framework, you explain the existing theories that support your research ...

Steps to Developing the Perfect Conceptual Framework. Pick a question. Conduct a literature review. Identify your variables. Create your conceptual framework. 1. Pick a Question. You should already have some idea of the broad area of your research project. Try to narrow down your research field to a manageable topic in terms of time and resources.

4 Steps on How to Make the Conceptual Framework. Choose your topic. Do a literature review. Isolate the important variables. Generate the conceptual framework. Example of a Conceptual Framework. Research Topic. Thesis Statement. Review of Literature.

the conceptual framework, as well as the process of developing one, since a conceptual framework is a generative source of thinking, planning, conscious action, and reflection throughout the research process. A conceptual framework makes the case for why a study is significant and relevant

Frameworks are important research tools across nearly all fields of science. They are critically important for structuring empirical inquiry and theoretical development in the environmental social sciences, governance research and practice, the sustainability sciences and fields of social-ecological systems research in tangent with the associated disciplines of those fields (Binder et al. 2013 ...