Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Academic Proposals

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource introduces the genre of academic proposals and provides strategies for developing effective graduate-level proposals across multiple contexts.

Introduction

An important part of the work completed in academia is sharing our scholarship with others. Such communication takes place when we present at scholarly conferences, publish in peer-reviewed journals, and publish in books. This OWL resource addresses the steps in writing for a variety of academic proposals.

For samples of academic proposals, click here .

Important considerations for the writing process

First and foremost, you need to consider your future audience carefully in order to determine both how specific your topic can be and how much background information you need to provide in your proposal. While some conferences and journals may be subject-specific, most will require you to address an audience that does not conduct research on the same topics as you. Conference proposal reviewers are often drawn from professional organization members or other attendees, while journal proposals are typically reviewed by the editorial staff, so you need to ensure that your proposal is geared toward the knowledge base and expectations of whichever audience will read your work.

Along those lines, you might want to check whether you are basing your research on specific prior research and terminology that requires further explanation. As a rule, always phrase your proposal clearly and specifically, avoid over-the-top phrasing and jargon, but do not negate your own personal writing style in the process.

If you would like to add a quotation to your proposal, you are not required to provide a citation or footnote of the source, although it is generally preferred to mention the author’s name. Always put quotes in quotation marks and take care to limit yourself to at most one or two quotations in the entire proposal text. Furthermore, you should always proofread your proposal carefully and check whether you have integrated details, such as author’s name, the correct number of words, year of publication, etc. correctly.

Methodology is often a key factor in the evaluation of proposals for any academic genre — but most proposals have such a small word limit that writers find it difficult to adequately include methods while also discussing their argument, background for the study, results, and contributions to knowledge. It's important to make sure that you include some information about the methods used in your study, even if it's just a line or two; if your proposal isn't experimental in nature, this space should instead describe the theory, lens, or approach you are taking to arrive at your conclusions.

Reasons proposals fail/common pitfalls

There are common pitfalls that you might need to improve on for future proposals.

The proposal does not reflect your enthusiasm and persuasiveness, which usually goes hand in hand with hastily written, simply worded proposals. Generally, the better your research has been, the more familiar you are with the subject and the more smoothly your proposal will come together.

Similarly, proposing a topic that is too broad can harm your chances of being accepted to a conference. Be sure to have a clear focus in your proposal. Usually, this can be avoided by more advanced research to determine what has already been done, especially if the proposal is judged by an important scholar in the field. Check the names of keynote speakers and other attendees of note to avoid repeating known information or not focusing your proposal.

Your paper might simply have lacked the clear language that proposals should contain. On this linguistic level, your proposal might have sounded repetitious, have had boring wording, or simply displayed carelessness and a lack of proofreading, all of which can be remedied by more revisions. One key tactic for ensuring you have clear language in your proposal is signposting — you can pick up key phrases from the CFP, as well as use language that indicates different sections in academic work (as in IMRAD sections from the organization and structure page in this resource). This way, reviewers can easily follow your proposal and identify its relatedness to work in the field and the CFP.

Conference proposals

Conference proposals are a common genre in graduate school that invite several considerations for writing depending on the conference and requirements of the call for papers.

Beginning the process

Make sure you read the call for papers carefully to consider the deadline and orient your topic of presentation around the buzzwords and themes listed in the document. You should take special note of the deadline and submit prior to that date, as most conferences use online submission systems that will close on a deadline and will not accept further submissions.

If you have previously spoken on or submitted a proposal on the same topic, you should carefully adjust it specifically for this conference or even completely rewrite the proposal based on your changing and evolving research.

The topic you are proposing should be one that you can cover easily within a time frame of approximately fifteen to twenty minutes. You should stick to the required word limit of the conference call. The organizers have to read a large number of proposals, especially in the case of an international or interdisciplinary conference, and will appreciate your brevity.

Structure and components

Conference proposals differ widely across fields and even among individual conferences in a field. Some just request an abstract, which is written similarly to any other abstract you'd write for a journal article or other publication. Some may request abstracts or full papers that fit into pre-existing sessions created by conference organizers. Some request both an abstract and a further description or proposal, usually in cases where the abstract will be published in the conference program and the proposal helps organizers decide which papers they will accept.

If the conference you are submitting to requires a proposal or description, there are some common elements you'll usually need to include. These are a statement of the problem or topic, a discussion of your approach to the problem/topic, a discussion of findings or expected findings, and a discussion of key takeaways or relevance to audience members. These elements are typically given in this order and loosely follow the IMRAD structure discussed in the organization and structure page in this resource.

The proportional size of each of these elements in relation to one another tends to vary by the stage of your research and the relationship of your topic to the field of the conference. If your research is very early on, you may spend almost no time on findings, because you don't have them yet. Similarly, if your topic is a regular feature at conferences in your field, you may not need to spend as much time introducing it or explaining its relevance to the field; however, if you are working on a newer topic or bringing in a topic or problem from another discipline, you may need to spend slightly more space explaining it to reviewers. These decisions should usually be based on an analysis of your audience — what information can reviewers be reasonably expected to know, and what will you have to tell them?

Journal Proposals

Most of the time, when you submit an article to a journal for publication, you'll submit a finished manuscript which contains an abstract, the text of the article, the bibliography, any appendices, and author bios. These can be on any topic that relates to the journal's scope of interest, and they are accepted year-round.

Special issues , however, are planned issues of a journal that center around a specific theme, usually a "hot topic" in the field. The editor or guest editors for the special issue will often solicit proposals with a call for papers (CFP) first, accept a certain number of proposals for further development into article manuscripts, and then accept the final articles for the special issue from that smaller pool. Special issues are typically the only time when you will need to submit a proposal to write a journal article, rather than submitting a completed manuscript.

Journal proposals share many qualities with conference proposals: you need to write for your audience, convey the significance of your work, and condense the various sections of a full study into a small word or page limit. In general, the necessary components of a proposal include:

- Problem or topic statement that defines the subject of your work (often includes research questions)

- Background information (think literature review) that indicates the topic's importance in your field as well as indicates that your research adds something to the scholarship on this topic

- Methodology and methods used in the study (and an indication of why these methods are the correct ones for your research questions)

- Results or findings (which can be tentative or preliminary, if the study has not yet been completed)

- Significance and implications of the study (what will readers learn? why should they care?)

This order is a common one because it loosely follows the IMRAD (introduction, methods, results and discussion) structure often used in academic writing; however, it is not the only possible structure or even always the best structure. You may need to move these elements around depending on the expectations in your field, the word or page limit, or the instructions given in the CFP.

Some of the unique considerations of journal proposals are:

- The CFP may ask you for an abstract, a proposal, or both. If you need to write an abstract, look for more information on the abstract page. If you need to write both an abstract and a proposal, make sure to clarify for yourself what the difference is. Usually the proposal needs to include more information about the significance, methods, and/or background of the study than will fit in the abstract, but often the CFP itself will give you some instructions as to what information the editors are wanting in each piece of writing.

- Journal special issue CFPs, like conference CFPs, often include a list of topics or questions that describe the scope of the special issue. These questions or topics are a good starting place for generating a proposal or tying in your research; ensuring that your work is a good fit for the special issue and articulating why that is in the proposal increases your chances of being accepted.

- Special issues are not less valuable or important than regularly scheduled issues; therefore, your proposal needs to show that your work fits and could readily be accepted in any other issue of the journal. This means following some of the same practices you would if you were preparing to submit a manuscript to a journal: reading the journal's author submission guidelines; reading the last several years of the journal to understand the usual topics, organization, and methods; citing pieces from this journal and other closely related journals in your research.

Book Proposals

While the requirements are very similar to those of conference proposals, proposals for a book ought to address a few other issues.

General considerations

Since these proposals are of greater length, the publisher will require you to delve into greater detail as well—for instance, regarding the organization of the proposed book or article.

Publishers generally require a clear outline of the chapters you are proposing and an explication of their content, which can be several pages long in its entirety.

You will need to incorporate knowledge of relevant literature, use headings and sub-headings that you should not use in conference proposals. Be sure to know who wrote what about your topic and area of interest, even if you are proposing a less scholarly project.

Publishers prefer depth rather than width when it comes to your topic, so you should be as focused as possible and further outline your intended audience.

You should always include information regarding your proposed deadlines for the project and how you will execute this plan, especially in the sciences. Potential investors or publishers need to know that you have a clear and efficient plan to accomplish your proposed goals. Depending on the subject area, this information can also include a proposed budget, materials or machines required to execute this project, and information about its industrial application.

Pre-writing strategies

As John Boswell (cited in: Larsen, Michael. How to Write a Book Proposal. Writers Digest Books , 2004. p. 1) explains, “today fully 90 percent of all nonfiction books sold to trade publishers are acquired on the basis of a proposal alone.” Therefore, editors and agents generally do not accept completed manuscripts for publication, as these “cannot (be) put into the usual channels for making a sale”, since they “lack answers to questions of marketing, competition, and production.” (Lyon, Elizabeth. Nonfiction Book Proposals Anybody Can Write . Perigee Trade, 2002. pp. 6-7.)

In contrast to conference or, to a lesser degree, chapter proposals, a book proposal introduces your qualifications for writing it and compares your work to what others have done or failed to address in the past.

As a result, you should test the idea with your networks and, if possible, acquire other people’s proposals that discuss similar issues or have a similar format before submitting your proposal. Prior to your submission, it is recommended that you write at least part of the manuscript in addition to checking the competition and reading all about the topic.

The following is a list of questions to ask yourself before committing to a book project, but should in no way deter you from taking on a challenging project (adapted from Lyon 27). Depending on your field of study, some of these might be more relevant to you than others, but nonetheless useful to reiterate and pose to yourself.

- Do you have sufficient enthusiasm for a project that may span years?

- Will publication of your book satisfy your long-term career goals?

- Do you have enough material for such a long project and do you have the background knowledge and qualifications required for it?

- Is your book idea better than or different from other books on the subject? Does the idea spark enthusiasm not just in yourself but others in your field, friends, or prospective readers?

- Are you willing to acquire any lacking skills, such as, writing style, specific terminology and knowledge on that field for this project? Will it fit into your career and life at the time or will you not have the time to engage in such extensive research?

Essential elements of a book proposal

Your book proposal should include the following elements:

- Your proposal requires the consideration of the timing and potential for sale as well as its potential for subsidiary rights.

- It needs to include an outline of approximately one paragraph to one page of prose (Larsen 6) as well as one sample chapter to showcase the style and quality of your writing.

- You should also include the resources you need for the completion of the book and a biographical statement (“About the Author”).

- Your proposal must contain your credentials and expertise, preferably from previous publications on similar issues.

- A book proposal also provides you with the opportunity to include information such as a mission statement, a foreword by another authority, or special features—for instance, humor, anecdotes, illustrations, sidebars, etc.

- You must assess your ability to promote the book and know the market that you target in all its statistics.

The following proposal structure, as outlined by Peter E. Dunn for thesis and fellowship proposals, provides a useful guide to composing such a long proposal (Dunn, Peter E. “Proposal Writing.” Center for Instructional Excellence, Purdue University, 2007):

- Literature Review

- Identification of Problem

- Statement of Objectives

- Rationale and Significance

- Methods and Timeline

- Literature Cited

Most proposals for manuscripts range from thirty to fifty pages and, apart from the subject hook, book information (length, title, selling handle), markets for your book, and the section about the author, all the other sections are optional. Always anticipate and answer as many questions by editors as possible, however.

Finally, include the best chapter possible to represent your book's focus and style. Until an agent or editor advises you to do otherwise, follow your book proposal exactly without including something that you might not want to be part of the book or improvise on possible expected recommendations.

Publishers expect to acquire the book's primary rights, so that they can sell it in an adapted or condensed form as well. Mentioning any subsidiary rights, such as translation opportunities, performance and merchandising rights, or first-serial rights, will add to the editor's interest in buying your book. It is enticing to publishers to mention your manuscript's potential to turn into a series of books, although they might still hesitate to buy it right away—at least until the first one has been a successful endeavor.

The sample chapter

Since editors generally expect to see about one-tenth of a book, your sample chapter's length should reflect that in these building blocks of your book. The chapter should reflect your excitement and the freshness of the idea as well as surprise editors, but do not submit part of one or more chapters. Always send a chapter unless your credentials are impeccable due to prior publications on the subject. Do not repeat information in the sample chapter that will be covered by preceding or following ones, as the outline should be designed in such a way as to enable editors to understand the context already.

How to make your proposal stand out

Depending on the subject of your book, it is advisable to include illustrations that exemplify your vision of the book and can be included in the sample chapter. While these can make the book more expensive, it also increases the salability of the project. Further, you might consider including outstanding samples of your published work, such as clips from periodicals, if they are well-respected in the field. Thirdly, cover art can give your potential publisher a feel for your book and its marketability, especially if your topic is creative or related to the arts.

In addition, professionally formatting your materials will give you an edge over sloppy proposals. Proofread the materials carefully, use consistent and carefully organized fonts, spacing, etc., and submit your proposal without staples; rather, submit it in a neat portfolio that allows easy access and reassembling. However, check the submission guidelines first, as most proposals are submitted digitally. Finally, you should try to surprise editors and attract their attention. Your hook, however, should be imaginative but inexpensive (you do not want to bribe them, after all). Make sure your hook draws the editors to your book proposal immediately (Adapted from Larsen 154-60).

- Current Students

- Study with Us

- Work with Us

How to write a research proposal for a Master's dissertation

Unsure how to start your research proposal as part of your dissertation read below our top tips from banking and finance student, nelly, on how to structure your proposal and make sure it's a strong, formative foundation to build your dissertation..

It's understandable if the proposal part of your dissertation feels like a waste of time. Why not just get started on the dissertation itself? Isn't 'proposal' a just fancy word for a plan?

It's important to see your Master's research proposal not only as a requirement but as a way of formalising your ideas and mapping out the direction and purpose of your dissertation. A strong, carefully prepared proposal is instrumental in writing a good dissertation.

How to structure a research proposal for a Master's dissertation

First things first: what do you need to include in a research proposal? The recommended structure of your proposal is:

- Motivation: introduce your research question and give an overview of the topic, explain the importance of your research

- Theory: draw on existing pieces of research that are relevant to your topic of choice, leading up to your question and identifying how your dissertation will explore new territory

- Data and methodology: how do you plan to answer the research question? Explain your data sources and methodology

- Expected results: finally, what will the outcome be? What do you think your data and methodology will find?

Top Tips for Writing a Dissertation Research Proposal

Choose a dissertation topic well in advance of starting to write it

Allow existing research to guide you

Make your research questions as specific as possible

When you choose a topic, it will naturally be very broad and general. For example, Market Efficiency . Under this umbrella term, there are so many questions you could explore and challenge. But, it's so important that you hone in on one very specific question, such as ' How do presidential elections affect market efficiency?' When it comes to your Master's, the more specific and clear-cut the better.

Collate your bibliography as you go

Everyone knows it's best practice to update your bibliography as you go, but that doesn't just apply to the main bibliography document you submit with your dissertation. Get in the habit of writing down the title, author and date of the relevant article next to every note you make - you'll be grateful you did it later down the line!

Colour code your notes based on which part of the proposal they apply to

Use highlighters and sticky notes to keep track of why you thought a certain research piece was useful, and what you intended to use it for. For example, if you've underlined lots of sections of a research article when it comes to pulling your research proposal together it will take you longer to remember what piece of research applies to where.

Instead, you may want to highlight anything that could inform your methodology in blue, any quotations that will form your theory in yellow etc. This will save you time and stress later down the line.

Write your Motivation after your Theory

Your Motivation section will be that much more coherent and specific if you write it after you've done all your research. All the reading you have done for your Theory will better cement the importance of your research, as well as provide plenty of context for you to write in detail your motivation. Think about the difference between ' I'm doing this because I'm interested in it ' vs. ' I'm doing this because I'm passionate, and I've noticed a clear gap in this area of study which is detailed below in example A, B and C .'

Make sure your Data and Methodology section is to the point and succinct

Link your Expectations to existing research

Your expectations should be based on research and data, not conjecture and assumptions. It doesn't matter if the end results match up to what you expected, as long as both of these sections are informed by research and data.

Published By Nelly on 01/09/2020 | Last Updated 23/01/2024

Related Articles

Why is English important for international students?

If you want to study at a UK university, knowledge of English is essential. Your degree will be taught in English and it will be the common language you share with friends. Being confident in English...

How to revise: 5 top revision techniques

Wondering how to revise for exams? It’s easy to get stuck in a loop of highlighting, copying out, reading and re-reading the same notes. But does it really work? Not all revision techniques are...

How can international students open a bank account in the UK?

Opening a student bank account in the UK can be a great way to manage your spending and take advantage of financial offers for university students. Read on to find out how to open a bank account as...

You May Also Like

How to write a good research proposal (in 9 steps)

A good research proposal is one of the keys to academic success. For bachelor’s and master’s students, the quality of a research proposal often determines whether the master’s program= can be completed or not. For PhD students, a research proposal is often the first step to securing a university position. This step-by-step manual guides you through the main stages of proposal writing.

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase using the links below at no additional cost to you . I only recommend products or services that I truly believe can benefit my audience. As always, my opinions are my own.

1. Find a topic for your research proposal

2. develop your research idea, 3. conduct a literature review for your research proposal, 4. define a research gap and research question, 5. establish a theoretical framework for your research proposal, 6. specify an empirical focus for your research proposal, 7. emphasise the scientific and societal relevance of your research proposal, 8. develop a methodology in your research proposal, 9. illustrate your research timeline in your research proposal.

Finding a topic for your research is a crucial first step. This decision should not be treated lightly.

Writing a master’s thesis takes a minimum of several weeks. In the case of PhD dissertations, it takes years. That is a long time! You don’t want to be stuck with a topic that you don’t care about.

How to find a research topic? Start broadly: Which courses did you enjoy? What issues discussed during seminars or lectures did you like? What inspired you during your education? And which readings did you appreciate?

Take a blank piece of paper. Write down everything that comes to your mind. It will help you to reflect on your interests.

Then, think more strategically. Maybe you have a rough idea of where you would like to work after graduation. Maybe a specific sector. Or even a particular company. If so, you could strategically alight your thesis topic with an issue that matters to your dream employer. Or even ask for a thesis internship.

Once you pinpoint your general topic of interest, you need to develop your idea.

Your idea should be simultaneously original, make a scientific contribution, prepare you for the (academic) job market, and be academically sound.

Freaking out yet?! Take a deep breath.

First, keep in mind that your idea should be very focused. Master and PhD students are often too ambitious. Your time is limited. So you need to be pragmatic. It is better to make a valuable contribution to a very specific question than to aim high and fail to meet your objectives.

Second, writing a research proposal is not a linear process. Start slowly by reading literature about your topic of interest. You have an interest. You read. You rethink your idea. You look for a theoretical framework. You go back to your idea and refine it. It is a process.

Remember that a good research proposal is not written in a day.

And third, don’t forget: a good proposal aims to establish a convincing framework that will guide your future research. Not to provide all the answers already. You need to show that you have a feasible idea.

If you are looking to elevate your writing and editing skills, I highly recommend enrolling in the course “ Good with Words: Writing and Editing Specialization “, which is a 4 course series offered by the University of Michigan. This comprehensive program is conveniently available as an online course on Coursera, allowing you to learn at your own pace. Plus, upon successful completion, you’ll have the opportunity to earn a valuable certificate to showcase your newfound expertise!

Academic publications (journal articles and books) are the foundation of any research. Thus, academic literature is a good place to start. Especially when you still feel kind of lost regarding a focused research topic.

Type keywords reflecting your interests, or your preliminary research idea, into an academic search engine. It can be your university’s library, Google Scholar , Web of Science , or Scopus . etcetera.

Look at what has been published in the last 5 years, not before. You don’t want to be outdated.

Download interesting-sounding articles and read them. Repeat but be cautious: You will never be able to read EVERYTHING. So set yourself a limit, in hours, days or number of articles (20 articles, for instance).

Now, write down your findings. What is known about your topic of interest? What do scholars focus on? Start early by writing down your findings and impressions.

Once you read academic publications on your topic of interest, ask yourself questions such as:

- Is there one specific aspect of your topic of interest that is neglected in the existing literature?

- What do scholars write about the existing gaps on the topic? What are their suggestions for future research?

- Is there anything that YOU believe warrants more attention?

- Do scholars maybe analyze a phenomenon only in a specific type of setting?

Asking yourself these questions helps you to formulate your research question. In your research question, be as specific as possible.

And keep in mind that you need to research something that already exists. You cannot research how something develops 20 years into the future.

A theoretical framework is different from a literature review. You need to establish a framework of theories as a lens to look at your research topic, and answer your research question.

A theory is a general principle to explain certain phenomena. No need to reinvent the wheel here.

It is not only accepted but often encouraged to make use of existing theories. Or maybe you can combine two different theories to establish your framework.

It also helps to go back to the literature. Which theories did the authors of your favourite publications use?

There are only very few master’s and PhD theses that are entirely theoretical. Most theses, similar to most academic journal publications, have an empirical section.

You need to think about your empirical focus. Where can you find answers to your research question in real life? This could be, for instance, an experiment, a case study, or repeated observations of certain interactions.

Maybe your empirical investigation will have geographic boundaries (like focusing on one city, or one country). Or maybe it focuses on one group of people (such as the elderly, CEOs, doctors, you name it).

It is also possible to start the whole research proposal idea with empirical observation. Maybe you’ve come across something in your environment that you would like to investigate further.

Pinpoint what fascinates you about your observation. Write down keywords reflecting your interest. And then conduct a literature review to understand how others have approached this topic academically.

Both master’s and PhD students are expected to make a scientific contribution. A concrete gap or shortcoming in the existing literature on your topic is the easiest way to justify the scientific relevance of your proposed research.

Societal relevance is increasingly important in academia, too.

Do the grandparent test: Explain what you want to do to your grandparents (or any other person for that matter). Explain why it matters. Do your grandparents understand what you say? If so, well done. If not, try again.

Always remember. There is no need for fancy jargon. The best proposals are the ones that use clear, straightforward language.

The methodology is a system of methods that you will use to implement your research. A methodology explains how you plan to answer your research question.

A methodology involves for example methods of data collection. For example, interviews and questionnaires to gather ‘raw’ data.

Methods of data analysis are used to make sense of this data. This can be done, for instance, by coding, discourse analysis, mapping or statistical analysis.

Don’t underestimate the value of a good timeline. Inevitably throughout your thesis process, you will feel lost at some point. A good timeline will bring you back on track.

Make sure to include a timeline in your research proposal. If possible, not only describe your timeline but add a visual illustration, for instance in the form of a Gantt chart.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

PhD thesis types: Monograph and collection of articles

Ten reasons not to pursue an academic career, related articles.

How to address data privacy and confidentiality concerns of AI in research

How to properly use AI in academic research

The best online courses for PhD researchers in 2024

Why and how to conduct a systematic literature review

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal.

A research proposal should present your idea or question and expected outcomes with clarity and definition – the what.

It should also make a case for why your question is significant and what value it will bring to your discipline – the why.

What it shouldn't do is answer the question – that's what your research will do.

Why is it important?

Research proposals are significant because Another reason why it formally outlines your intended research. Which means you need to provide details on how you will go about your research, including:

- your approach and methodology

- timeline and feasibility

- all other considerations needed to progress your research, such as resources.

Think of it as a tool that will help you clarify your idea and make conducting your research easier.

How long should it be?

Usually no more than 2000 words, but check the requirements of your degree, and your supervisor or research coordinator.

Presenting your idea clearly and concisely demonstrates that you can write this way – an attribute of a potential research candidate that is valued by assessors.

What should it include?

Project title.

Your title should clearly indicate what your proposed research is about.

Research supervisor

State the name, department and faculty or school of the academic who has agreed to supervise you. Rest assured, your research supervisor will work with you to refine your research proposal ahead of submission to ensure it meets the needs of your discipline.

Proposed mode of research

Describe your proposed mode of research. Which may be closely linked to your discipline, and is where you will describe the style or format of your research, e.g. data, field research, composition, written work, social performance and mixed media etc.

This is not required for research in the sciences, but your research supervisor will be able to guide you on discipline-specific requirements.

Aims and objectives

What are you trying to achieve with your research? What is the purpose? This section should reference why you're applying for a research degree. Are you addressing a gap in the current research? Do you want to look at a theory more closely and test it out? Is there something you're trying to prove or disprove? To help you clarify this, think about the potential outcome of your research if you were successful – that is your aim. Make sure that this is a focused statement.

Your objectives will be your aim broken down – the steps to achieving the intended outcome. They are the smaller proof points that will underpin your research's purpose. Be logical in the order of how you present these so that each succeeds the previous, i.e. if you need to achieve 'a' before 'b' before 'c', then make sure you order your objectives a, b, c.

A concise summary of what your research is about. It outlines the key aspects of what you will investigate as well as the expected outcomes. It briefly covers the what, why and how of your research.

A good way to evaluate if you have written a strong synopsis, is to get somebody to read it without reading the rest of your research proposal. Would they know what your research is about?

Now that you have your question clarified, it is time to explain the why. Here, you need to demonstrate an understanding of the current research climate in your area of interest.

Providing context around your research topic through a literature review will show the assessor that you understand current dialogue around your research, and what is published.

Demonstrate you have a strong understanding of the key topics, significant studies and notable researchers in your area of research and how these have contributed to the current landscape.

Expected research contribution

In this section, you should consider the following:

- Why is your research question or hypothesis worth asking?

- How is the current research lacking or falling short?

- What impact will your research have on the discipline?

- Will you be extending an area of knowledge, applying it to new contexts, solving a problem, testing a theory, or challenging an existing one?

- Establish why your research is important by convincing your audience there is a gap.

- What will be the outcome of your research contribution?

- Demonstrate both your current level of knowledge and how the pursuit of your question or hypothesis will create a new understanding and generate new information.

- Show how your research is innovative and original.

Draw links between your research and the faculty or school you are applying at, and explain why you have chosen your supervisor, and what research have they or their school done to reinforce and support your own work. Cite these reasons to demonstrate how your research will benefit and contribute to the current body of knowledge.

Proposed methodology

Provide an overview of the methodology and techniques you will use to conduct your research. Cover what materials and equipment you will use, what theoretical frameworks will you draw on, and how will you collect data.

Highlight why you have chosen this particular methodology, but also why others may not have been as suitable. You need to demonstrate that you have put thought into your approach and why it's the most appropriate way to carry out your research.

It should also highlight potential limitations you anticipate, feasibility within time and other constraints, ethical considerations and how you will address these, as well as general resources.

A work plan is a critical component of your research proposal because it indicates the feasibility of completion within the timeframe and supports you in achieving your objectives throughout your degree.

Consider the milestones you aim to achieve at each stage of your research. A PhD or master's degree by research can take two to four years of full-time study to complete. It might be helpful to offer year one in detail and the following years in broader terms. Ultimately you have to show that your research is likely to be both original and finished – and that you understand the time involved.

Provide details of the resources you will need to carry out your research project. Consider equipment, fieldwork expenses, travel and a proposed budget, to indicate how realistic your research proposal is in terms of financial requirements and whether any adjustments are needed.

Bibliography

Provide a list of references that you've made throughout your research proposal.

Apply for postgraduate study

New hdr curriculum, find a supervisor.

Search by keyword, topic, location, or supervisor name

- 1800 SYD UNI ( 1800 793 864 )

- or +61 2 8627 1444

- Open 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday

- Student Centre Level 3 Jane Foss Russell Building Darlington Campus

Scholarships

Find the right scholarship for you

Research areas

Our research covers the spectrum – from linguistics to nanoscience

Our breadth of expertise across our faculties and schools is supported by deep disciplinary knowledge. We have significant capability in more than 20 major areas of research.

Research facilities

High-impact research through state-of-the-art infrastructure

- Postgraduate

Research degrees

- Examples of Research proposals

- Apply for 2024

- Find a course

- Accessibility

Examples of research proposals

How to write your research proposal, with examples of good proposals.

Research proposals

Your research proposal is a key part of your application. It tells us about the question you want to answer through your research. It is a chance for you to show your knowledge of the subject area and tell us about the methods you want to use.

We use your research proposal to match you with a supervisor or team of supervisors.

In your proposal, please tell us if you have an interest in the work of a specific academic at York St John. You can get in touch with this academic to discuss your proposal. You can also speak to one of our Research Leads. There is a list of our Research Leads on the Apply page.

When you write your proposal you need to:

- Highlight how it is original or significant

- Explain how it will develop or challenge current knowledge of your subject

- Identify the importance of your research

- Show why you are the right person to do this research

- Research Proposal Example 1 (DOC, 49kB)

- Research Proposal Example 2 (DOC, 0.9MB)

- Research Proposal Example 3 (DOC, 55.5kB)

- Research Proposal Example 4 (DOC, 49.5kB)

Subject specific guidance

- Writing a Humanities PhD Proposal (PDF, 0.1MB)

- Writing a Creative Writing PhD Proposal (PDF, 0.1MB)

- About the University

- Our culture and values

- Academic schools

- Academic dates

- Press office

Our wider work

- Business support

- Work in the community

- Donate or support

Connect with us

York St John University

Lord Mayor’s Walk

01904 624 624

York St John London Campus

6th Floor Export Building

1 Clove Crescent

01904 876 944

- Policies and documents

- Module documents

- Programme specifications

- Quality gateway

- Admissions documents

- Access and Participation Plan

- Freedom of information

- Accessibility statement

- Modern slavery and human trafficking statement

© York St John University 2024

Colour Picker

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Dui id ornare arcu odio.

Felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis ipsum. Et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Faucibus pulvinar elementum integer enim neque volutpat ac. Hac habitasse platea dictumst vestibulum rhoncus.

Nec ullamcorper sit amet risus nullam eget felis eget. Eget felis eget nunc lobortis mattis aliquam faucibus purus.

- Utility Menu

GA4 tracking code

- CARAT (Opportunities Database)

- URAF Application Instructions

- URAF Calendar

Writing Research Proposals

The research proposal is your opportunity to show that you—and only you!—are the perfect person to take on your specific project. After reading your research proposal, readers should be confident that…

- You have thoughtfully crafted and designed this project;

- You have the necessary background to complete this project;

- You have the proper support system in place;

- You know exactly what you need to complete this project and how to do so; and

- With this funding in hand, you can be on your way to a meaningful research experience and a significant contribution to your field.

Research proposals typically include the following components:

- Why is your project important? How does it contribute to the field or to society? What do you hope to prove?

- This section includes the project design, specific methodology, your specific role and responsibilities, steps you will take to execute the project, etc. Here you will show the committee the way that you think by explaining both how you have conceived the project and how you intend to carry it out.

- Please be specific in the project dates/how much time you need to carry out the proposed project. The scope of the project should clearly match the timeframe in which you propose to complete it!

- Funding agencies like to know how their funding will be used. Including this information will demonstrate that you have thoughtfully designed the project and know of all of the anticipated expenses required to see it through to completion.

- It is important that you have a support system on hand when conducting research, especially as an undergraduate. There are often surprises and challenges when working on a long-term research project and the selection committee wants to be sure that you have the support system you need to both be successful in your project and also have a meaningful research experience.

- Some questions to consider are: How often do you intend to meet with your advisor(s)? (This may vary from project to project based on the needs of the student and the nature of the research.) What will your mode of communication be? Will you be attending (or even presenting at) lab meetings?

Don’t be afraid to also include relevant information about your background and advocate for yourself! Do you have skills developed in a different research experience (or leadership position, job, coursework, etc.) that you could apply to the project in question? Have you already learned about and experimented with a specific method of analysis in class and are now ready to apply it to a different situation? If you already have experience with this professor/lab, please be sure to include those details in your proposal! That will show the selection committee that you are ready to hit the ground running!

Lastly, be sure to know who your readers are so that you can tailor the field-specific language of your proposal accordingly. If the selection committee are specialists in your field, you can feel free to use the jargon of that field; but if your proposal will be evaluated by an interdisciplinary committee (this is common), you might take a bit longer explaining the state of the field, specific concepts, and certainly spelling out any acronyms.

- Getting Started

- Application Components

- Interviews and Offers

- Building On Your Experiences

- Applying FAQs

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Advanced Research Methods

- Writing a Research Proposal

- What Is Research?

- Library Research

What Is a Research Proposal?

Reference books.

- Writing the Research Paper

- Presenting the Research Paper

When applying for a research grant or scholarship, or, just before you start a major research project, you may be asked to write a preliminary document that includes basic information about your future research. This is the information that is usually needed in your proposal:

- The topic and goal of the research project.

- The kind of result expected from the research.

- The theory or framework in which the research will be done and presented.

- What kind of methods will be used (statistical, empirical, etc.).

- Short reference on the preliminary scholarship and why your research project is needed; how will it continue/justify/disprove the previous scholarship.

- How much will the research project cost; how will it be budgeted (what for the money will be spent).

- Why is it you who can do this research and not somebody else.

Most agencies that offer scholarships or grants provide information about the required format of the proposal. It may include filling out templates, types of information they need, suggested/maximum length of the proposal, etc.

Research proposal formats vary depending on the size of the planned research, the number of participants, the discipline, the characteristics of the research, etc. The following outline assumes an individual researcher. This is just a SAMPLE; several other ways are equally good and can be successful. If possible, discuss your research proposal with an expert in writing, a professor, your colleague, another student who already wrote successful proposals, etc.

Author, author's affiliation

Introduction:

- Explain the topic and why you chose it. If possible explain your goal/outcome of the research . How much time you need to complete the research?

Previous scholarship:

- Give a brief summary of previous scholarship and explain why your topic and goals are important.

- Relate your planned research to previous scholarship. What will your research add to our knowledge of the topic.

Specific issues to be investigated:

- Break down the main topic into smaller research questions. List them one by one and explain why these questions need to be investigated. Relate them to previous scholarship.

- Include your hypothesis into the descriptions of the detailed research issues if you have one. Explain why it is important to justify your hypothesis.

Methodology:

- This part depends of the methods conducted in the research process. List the methods; explain how the results will be presented; how they will be assessed.

- Explain what kind of results will justify or disprove your hypothesis.

- Explain how much money you need.

- Explain the details of the budget (how much you want to spend for what).

Conclusion:

- Describe why your research is important.

References:

- List the sources you have used for writing the research proposal, including a few main citations of the preliminary scholarship.

- << Previous: Library Research

- Next: Writing the Research Paper >>

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 12:24 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/research-methods

- Graduate School

How to Write a Master's Thesis Proposal

How to write a master’s thesis proposal is one of the most-asked questions by graduate students. A master's thesis proposal involves a copious amount of data collection, particular presentation ethics, and most importantly, it will become the roadmap to your full thesis. Remember, you must convince your committee that your idea is strong and unique, and that you have done enough legwork to begin with the first few drafts of your final thesis. Your proposal should serve as a foundational blueprint on which you will later build your entire project. To have the perfect thesis proposal, you need to have original ideas, solid information, and proper presentation. While it is a good idea to take assistance from thesis writing services , you still need to personally understand the elements that contribute to a master’s thesis proposal worthy of approval. In this blog, we will discuss the process of writing your master’s thesis proposal and give you tips for making your proposal strong. Stay tuned!

>> Want us to help you get accepted? Schedule a free strategy call here . <<

Article Contents 8 min read

How to decide the goals for your master's thesis.

If you are pursuing a master’s or a PhD , you will be undertaking a major research paper or a thesis. Thus, writing a thesis proposal becomes inevitable. Your major objective for pursuing a master’s degree is to improve your knowledge in your field of study. When you start your degree, you delve deeper into different concepts in your discipline and try to search for answers to all kinds of questions. If you come across a question that no one can answer, you can select that question as your research thesis topic.

A master's thesis proposal will have multiple sections depending on your decided layout. These sections will continuously support your argument and try to convince the reader of your core argument. The structure will also help you arrange the various parts of the paper to have a greater impact on the readers. A paper should always begin with you giving a brief summary of the topic and how you have come across it. The introduction is particularly important because it will give the readers a brief idea about the topic of discussion and win their interest in the matter.

After the summary has been given, slowly you need to progress into the body of the thesis proposal which would explain your argument, research methodology, literary texts that have a relation to the topic, and the conclusion of your study. It would be similar to an essay or a literary review consisting of 3 or 4 parts. The bibliography will be placed at the end of the paper so that people can cross-check your sources.

Let's take a look at the sections most master's thesis proposals should cover. Please note that each university has its own guidelines for how to structure and what to include in a master’s thesis proposal. The outline we provide below is general, so please make sure to follow the exact guidelines provided by your school:

Restate your primary argument and give us a glimpse of what you will include in the main master\u2019s thesis. Leave the reader wanting more. Your research proposal should talk about what research chapters you are trying to undertake in your final thesis. You can also mention the proposed time in which you will complete these chapters. ","label":"Conclusion and proposed chapters","title":"Conclusion and proposed chapters"}]" code="tab1" template="BlogArticle">

A thesis proposal needs to be convincing enough to get approval. If the information is not enough to satisfy the evaluation committee, it would require revision. Hence, you need to select and follow the right methodology to make your argument convincing. When a research proposal is presented, the reader will determine the validity of your argument by judging the strength of your evidence and conclusions. Therefore, even writige:ng a proposal will require extensive research on your part. You should start writing your thesis proposal by working through the following steps.

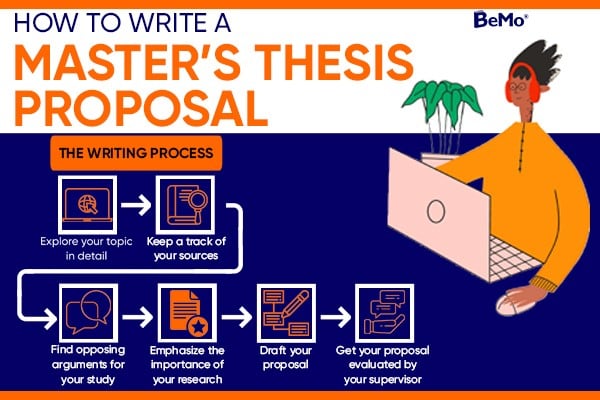

Interested in a summary of the points covered below? Check out this infographic:

Exploring your topic in detail

You need to delve deeper into your chosen topic to see if your idea is original. In the process of this exploration, you will find tons of materials that will be supportive of your argument. When choosing your research topic and the problem you want to explore, you should always consider your primary research interest (yes, the one which you had mentioned in your research interest statement during grad school applications) for a better master’s thesis. You have a high probability of performing better in an area that you have always liked as compared to any other research area or topic.

Reviewing the literature

You have to include all the sources from where you have formed your argument and mention them in the thesis proposal. If you neglect to mention important source texts, the reader may consider it to be plagiarism. Furthermore, you want to keep track of all your research because it will be easier to provide references if you know the exact source of each piece of information.

Finding opposing arguments for your study

You should also mention any texts that would counter your argument and try to disprove their claims in the thesis. Make sure to use evidence if you try to disprove the counterarguments you face.

Emphasizing the importance of your research

At the end of the thesis proposal, you need to convince the reader why your proposal is important to your chosen field of study, which would ultimately help you in getting your topic approved. Thus, it is essential to outline the importance of your research thoroughly.

Drafting your proposal

After doing proper research, you should go ahead and draft your proposal. Remember you will not get it right in just one draft, it will take at least 50 attempts to come up with a satisfactory proposal. You should proofread your draft several times and even have a fellow student review it for you before sending it further to your research supervisor.

Getting your proposal evaluated by your supervisor

After you have written sufficient drafts, you need to get your proposal evaluated by your research supervisor. This is necessary to meet the graduate research requirements. It will ensure the clarity and correctness of your proposal. For your supervisor to evaluate your proposal, you should complete the research methodology part along with sufficient proposed work.

Since your supervisor will play a crucial role in your master's research thesis, you must choose a supervisor who can be your ultimate guide in writing your master's thesis. They will be your partner and support system during your study and will help you in eliminating obstacles to achieving your goal.

Choosing the ideal supervisor is a pretty daunting task. Here’s how you can go about the process:

You should approach your professor with an open mind and discuss the potential goals of your research. You should hear what they think and then if you both mutually agree, you can choose them as your supervisor for your master\u2019s thesis. "}]">

Length of a Master’s Thesis Proposal

The length of a master’s thesis proposal differs from university to university and depends on the discipline of research as well. Usually, you have to include all the above-mentioned sections, and the length is around 8 pages and can go up to 12-15 pages for subjects such as the liberal arts. Universities might also define the number of words in the guidelines for your master’s thesis proposal and you have to adhere to that word limit.

Are you debating between pursuing a Masters or a PhD? This video has details that can help you decide which is best for you:

How to Format a Research Thesis Proposal Correctly?

Now that you know how to write a thesis proposal, you must make it presentable. Although your school might give your specific instructions, you can keep in mind some of the general advice:

- You can use some basic font like Times New Roman and keep the font size to 10 or 12 points.

- The left margin should be 1.5 inches and all other margins should be 1 inch each.

- You should follow double-spacing for your content.

- The first line of paragraphs should be indented 0.5 inches and the paragraphs should be left or center aligned.

Tips to Write a Strong Master's Thesis Proposal

When you are writing your master’s thesis proposal, you should keep these tips in mind to write an excellent master’s thesis proposal with all the correct elements to get approval from the evaluating committee:

Select your research objectives wisely

You should be clear on what you wish to learn from your research. Your learning objectives should stem from your research interests. If you are unsure, refer to your grad school career goals statement to review what you wanted out of grad school in the first place. Then, choose your objectives around it.

Write a clear title

The title of your research proposal should be concise and written in a language that can be understood easily by others. The title should be able to give the reader an idea of your intended research and should be interesting.

Jot down your thoughts, arguments, and evidence

You should always start with a rough outline of your arguments because you will not miss any point in this way. Brainstorm what you want to include in the proposal and then expand those points to complete your proposal. You can decide the major headings with the help of the guidelines provided to you.

Focus on the feasibility and importance

You should consider whether your research is feasible with the available resources. Additionally, your proposal should clearly convey the significance of your research in your field.

Use simple language

Since the evaluation committee can have researchers from different subject areas, it is best to write your proposal in a simple language that is understandable by all.

Stick to the guidelines

Your university will be providing the guidelines for writing your research proposal. You should adhere to those guidelines strictly since your proposal will be primarily evaluated on the basis of those.

Have an impactful opening section

It is a no-brainer that the opening statement of your proposal should be powerful enough to grasp the attention of the readers and get them interested in your research topic. You should be able to convey your interest and enthusiasm in the introductory section.

Peer review prior to submission

Apart from working with your research supervisor, it is essential that you ask some classmates and friends to review your proposal. The comments and suggestions that they give will be valuable in helping you to make the language of your proposal clearer.

You have worked hard to get into grad school and even harder on searching your research topic. Thus, you must be careful while building your thesis proposal so that you have maximum chances of acceptance.

If you're curious how your graduate school education will differ from your undergraduate education, take a look at this video so you know what to expect:

Writing the perfect research proposal might be challenging, but keeping to the basics might make your task easier. In a nutshell, you need to be thorough in your study question. You should conduct sufficient research to gather all relevant materials required to support your argument. After collecting all data, make sure to present it systematically to give a clearer understanding and convince the evaluators to approve your proposal. Lastly, remember to submit your proposal well within the deadline set by your university. Your performance at grad school is essential, especially if you need a graduate degree to gain admission to med school and your thesis contributes to that performance. Thus, start with a suitable research problem, draft a strong proposal, and then begin with your thesis after your proposal is approved.

In your master’s thesis proposal, you should include your research topic and the problem statement being addressed in your research, along with a proposed solution. The proposal should explain the importance and limitations of your research.

The length of a master’s thesis proposal is outlined by the university in the instructions for preparing your master’s thesis proposal.

The time taken to write a master’s thesis proposal depends upon the study which you are undertaking and your discipline of research. It will take a minimum time of three months. The ideal time can be around six months.

You should begin your master’s thesis proposal by writing an introduction to your research topic. You should state your topic clearly and provide some background. Keep notes and rough drafts of your proposal so you can always refer to them when you write the first real draft.

The basic sections that your master’s thesis proposal should cover are the problem statement, research methodology, proposed activities, importance, and the limitations of your research.

A master’s thesis proposal which clearly defines the problem in a straightforward and explains the research methodology in simple words is considered a good thesis proposal.

You can use any classic font for your master’s thesis proposal such as Times New Roman. If you are recommended a specific font in the proposal guidelines by your institution, it would be advisable to stick to that.

The ideal font size for your master’s thesis proposal will be 10 or 12 points.

Want more free tips? Subscribe to our channels for more free and useful content!

Apple Podcasts

Like our blog? Write for us ! >>

Have a question ask our admissions experts below and we'll answer your questions, get started now.

Talk to one of our admissions experts

Our site uses cookies. By using our website, you agree with our cookie policy .

FREE Training Webinar:

How to make your grad school application stand out, (and avoid the top 5 mistakes that get most rejected).

Time Sensitive. Limited Spots Available:

We guarantee you'll get into grad school or you don't pay.

Swipe up to see a great offer!

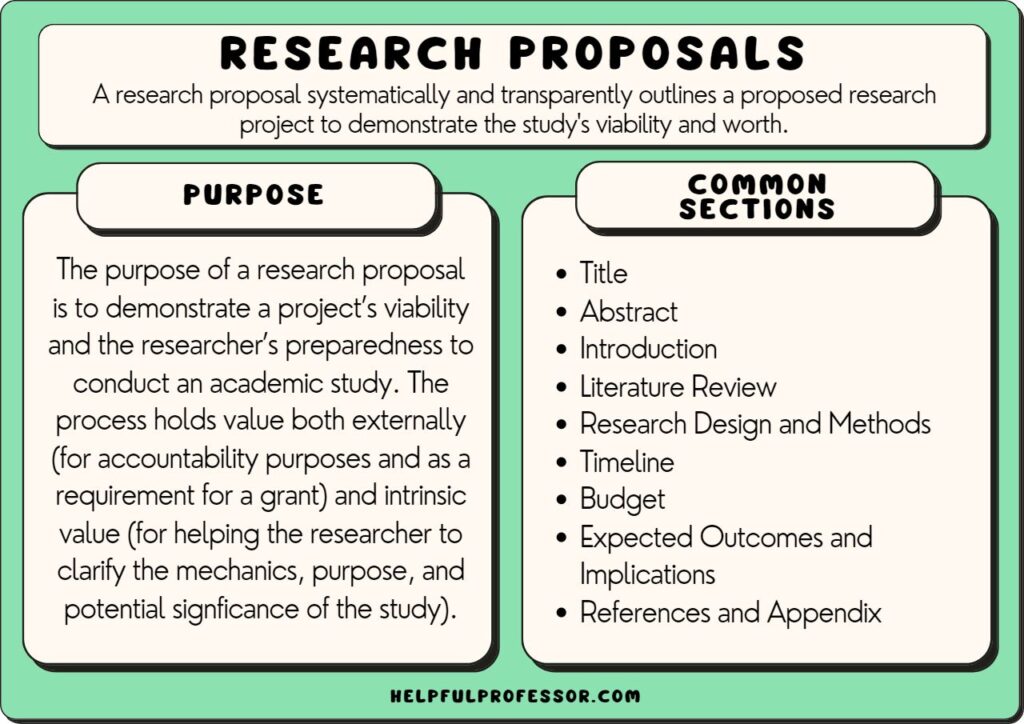

17 Research Proposal Examples

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.

Introduction: Introductions are all about contextualization. They often set the background information with a statement of the problem. At the end of the introduction, the reader should understand what the rationale for the study truly is. I like to see the research questions or hypotheses included in the introduction and I like to get a good understanding of what the significance of the research will be. It’s often easiest to write the introduction last

Literature Review: The literature review dives deep into the existing literature on the topic, demosntrating your thorough understanding of the existing literature including themes, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the literature. It serves both to demonstrate your knowledge of the field and, to demonstrate how the proposed study will fit alongside the literature on the topic. A good literature review concludes by clearly demonstrating how your research will contribute something new and innovative to the conversation in the literature.

Research Design and Methods: This section needs to clearly demonstrate how the data will be gathered and analyzed in a systematic and academically sound manner. Here, you need to demonstrate that the conclusions of your research will be both valid and reliable. Common points discussed in the research design and methods section include highlighting the research paradigm, methodologies, intended population or sample to be studied, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures . Toward the end of this section, you are encouraged to also address ethical considerations and limitations of the research process , but also to explain why you chose your research design and how you are mitigating the identified risks and limitations.

Timeline: Provide an outline of the anticipated timeline for the study. Break it down into its various stages (including data collection, data analysis, and report writing). The goal of this section is firstly to establish a reasonable breakdown of steps for you to follow and secondly to demonstrate to the assessors that your project is practicable and feasible.

Budget: Estimate the costs associated with the research project and include evidence for your estimations. Typical costs include staffing costs, equipment, travel, and data collection tools. When applying for a scholarship, the budget should demonstrate that you are being responsible with your expensive and that your funding application is reasonable.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: A discussion of the anticipated findings or results of the research, as well as the potential contributions to the existing knowledge, theory, or practice in the field. This section should also address the potential impact of the research on relevant stakeholders and any broader implications for policy or practice.

References: A complete list of all the sources cited in the research proposal, formatted according to the required citation style. This demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the relevant literature and ensures proper attribution of ideas and information.

Appendices (if applicable): Any additional materials, such as questionnaires, interview guides, or consent forms, that provide further information or support for the research proposal. These materials should be included as appendices at the end of the document.

Research Proposal Examples

Research proposals often extend anywhere between 2,000 and 15,000 words in length. The following snippets are samples designed to briefly demonstrate what might be discussed in each section.

1. Education Studies Research Proposals

See some real sample pieces:

- Assessment of the perceptions of teachers towards a new grading system

- Does ICT use in secondary classrooms help or hinder student learning?

- Digital technologies in focus project

- Urban Middle School Teachers’ Experiences of the Implementation of

- Restorative Justice Practices

- Experiences of students of color in service learning

Consider this hypothetical education research proposal:

The Impact of Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Middle School Mathematics

Abstract: The proposed study will explore multiplayer game-based learning techniques in middle school mathematics curricula and their effects on student engagement. The study aims to contribute to the current literature on game-based learning by examining the effects of multiplayer gaming in learning.

Introduction: Digital game-based learning has long been shunned within mathematics education for fears that it may distract students or lower the academic integrity of the classrooms. However, there is emerging evidence that digital games in math have emerging benefits not only for engagement but also academic skill development. Contributing to this discourse, this study seeks to explore the potential benefits of multiplayer digital game-based learning by examining its impact on middle school students’ engagement and academic performance in a mathematics class.

Literature Review: The literature review has identified gaps in the current knowledge, namely, while game-based learning has been extensively explored, the role of multiplayer games in supporting learning has not been studied.

Research Design and Methods: This study will employ a mixed-methods research design based upon action research in the classroom. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test control group design will first be used to compare the academic performance and engagement of middle school students exposed to game-based learning techniques with those in a control group receiving instruction without the aid of technology. Students will also be observed and interviewed in regard to the effect of communication and collaboration during gameplay on their learning.

Timeline: The study will take place across the second term of the school year with a pre-test taking place on the first day of the term and the post-test taking place on Wednesday in Week 10.

Budget: The key budgetary requirements will be the technologies required, including the subscription cost for the identified games and computers.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: It is expected that the findings will contribute to the current literature on game-based learning and inform educational practices, providing educators and policymakers with insights into how to better support student achievement in mathematics.

2. Psychology Research Proposals

See some real examples:

- A situational analysis of shared leadership in a self-managing team

- The effect of musical preference on running performance

- Relationship between self-esteem and disordered eating amongst adolescent females

Consider this hypothetical psychology research proposal:

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress Reduction in College Students

Abstract: This research proposal examines the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on stress reduction among college students, using a pre-test/post-test experimental design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods .

Introduction: College students face heightened stress levels during exam weeks. This can affect both mental health and test performance. This study explores the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation as a way to mediate stress levels in the weeks leading up to exam time.

Literature Review: Existing research on mindfulness-based meditation has shown the ability for mindfulness to increase metacognition, decrease anxiety levels, and decrease stress. Existing literature has looked at workplace, high school and general college-level applications. This study will contribute to the corpus of literature by exploring the effects of mindfulness directly in the context of exam weeks.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n= 234 ) will be randomly assigned to either an experimental group, receiving 5 days per week of 10-minute mindfulness-based interventions, or a control group, receiving no intervention. Data will be collected through self-report questionnaires, measuring stress levels, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ experiences, and students’ test scores.

Timeline: The study will begin three weeks before the students’ exam week and conclude after each student’s final exam. Data collection will occur at the beginning (pre-test of self-reported stress levels) and end (post-test) of the three weeks.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: The study aims to provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing stress among college students in the lead up to exams, with potential implications for mental health support and stress management programs on college campuses.

3. Sociology Research Proposals

- Understanding emerging social movements: A case study of ‘Jersey in Transition’

- The interaction of health, education and employment in Western China

- Can we preserve lower-income affordable neighbourhoods in the face of rising costs?

Consider this hypothetical sociology research proposal:

The Impact of Social Media Usage on Interpersonal Relationships among Young Adults

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effects of social media usage on interpersonal relationships among young adults, using a longitudinal mixed-methods approach with ongoing semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data.

Introduction: Social media platforms have become a key medium for the development of interpersonal relationships, particularly for young adults. This study examines the potential positive and negative effects of social media usage on young adults’ relationships and development over time.

Literature Review: A preliminary review of relevant literature has demonstrated that social media usage is central to development of a personal identity and relationships with others with similar subcultural interests. However, it has also been accompanied by data on mental health deline and deteriorating off-screen relationships. The literature is to-date lacking important longitudinal data on these topics.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n = 454 ) will be young adults aged 18-24. Ongoing self-report surveys will assess participants’ social media usage, relationship satisfaction, and communication patterns. A subset of participants will be selected for longitudinal in-depth interviews starting at age 18 and continuing for 5 years.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of five years, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between social media usage and interpersonal relationships among young adults, potentially informing social policies and mental health support related to social media use.

4. Nursing Research Proposals

- Does Orthopaedic Pre-assessment clinic prepare the patient for admission to hospital?

- Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of providing psychological care to burns patients

- Registered psychiatric nurse’s practice with mentally ill parents and their children

Consider this hypothetical nursing research proposal:

The Influence of Nurse-Patient Communication on Patient Satisfaction and Health Outcomes following Emergency Cesarians