Essay about Family: What It Is and How to Nail It

Humans naturally seek belonging within families, finding comfort in knowing someone always cares. Yet, families can also stir up insecurities and mental health struggles.

Family dynamics continue to intrigue researchers across different fields. Every year, new studies explore how these relationships shape our minds and emotions.

In this article, our dissertation service will guide you through writing a family essay. You can also dive into our list of topics for inspiration and explore some standout examples to spark your creativity.

What is Family Essay

A family essay takes a close look at the bonds and experiences within families. It's a common academic assignment, especially in subjects like sociology, psychology, and literature.

.webp)

So, what's involved exactly? Simply put, it's an exploration of what family signifies to you. You might reflect on cherished family memories or contemplate the portrayal of families in various media.

What sets a family essay apart is its personal touch. It allows you to express your own thoughts and experiences. Moreover, it's versatile – you can analyze family dynamics, reminisce about family customs, or explore other facets of familial life.

If you're feeling uncertain about how to write an essay about family, don't worry; you can explore different perspectives and select topics that resonate with various aspects of family life.

Tips For Writing An Essay On Family Topics

A family essay typically follows a free-form style, unless specified otherwise, and adheres to the classic 5-paragraph structure. As you jot down your thoughts, aim to infuse your essay with inspiration and the essence of creative writing, unless your family essay topics lean towards complexity or science.

.webp)

Here are some easy-to-follow tips from our essay service experts:

- Focus on a Specific Aspect: Instead of a broad overview, delve into a specific angle that piques your interest, such as exploring how birth order influences sibling dynamics or examining the evolving role of grandparents in modern families.

- Share Personal Anecdotes: Start your family essay introduction with a personal touch by sharing stories from your own experiences. Whether it's about a favorite tradition, a special trip, or a tough time, these stories make your writing more interesting.

- Use Real-life Examples: Illustrate your points with concrete examples or anecdotes. Draw from sources like movies, books, historical events, or personal interviews to bring your ideas to life.

- Explore Cultural Diversity: Consider the diverse array of family structures across different cultures. Compare traditional values, extended family systems, or the unique hurdles faced by multicultural families.

- Take a Stance: Engage with contentious topics such as homeschooling, reproductive technologies, or governmental policies impacting families. Ensure your arguments are supported by solid evidence.

- Delve into Psychology: Explore the psychological underpinnings of family dynamics, touching on concepts like attachment theory, childhood trauma, or patterns of dysfunction within families.

- Emphasize Positivity: Share uplifting stories of families overcoming adversity or discuss strategies for nurturing strong, supportive family bonds.

- Offer Practical Solutions: Wrap up your essay by proposing actionable solutions to common family challenges, such as fostering better communication, achieving work-life balance, or advocating for family-friendly policies.

Family Essay Topics

When it comes to writing, essay topics about family are often considered easier because we're intimately familiar with our own families. The more you understand about your family dynamics, traditions, and experiences, the clearer your ideas become.

If you're feeling uninspired or unsure of where to start, don't worry! Below, we have compiled a list of good family essay topics to help get your creative juices flowing. Whether you're assigned this type of essay or simply want to explore the topic, these suggestions from our history essay writer are tailored to spark your imagination and prompt meaningful reflection on different aspects of family life.

So, take a moment to peruse the list. Choose the essay topics about family that resonate most with you. Then, dive in and start exploring your family's stories, traditions, and connections through your writing.

- Supporting Family Through Tough Times

- Staying Connected with Relatives

- Empathy and Compassion in Family Life

- Strengthening Bonds Through Family Gatherings

- Quality Time with Family: How Vital Is It?

- Navigating Family Relationships Across Generations

- Learning Kindness and Generosity in a Large Family

- Communication in Healthy Family Dynamics

- Forgiveness in Family Conflict Resolution

- Building Trust Among Extended Family

- Defining Family in Today's World

- Understanding Nuclear Family: Various Views and Cultural Differences

- Understanding Family Dynamics: Relationships Within the Family Unit

- What Defines a Family Member?

- Modernizing the Nuclear Family Concept

- Exploring Shared Beliefs Among Family Members

- Evolution of the Concept of Family Love Over Time

- Examining Family Expectations

- Modern Standards and the Idea of an Ideal Family

- Life Experiences and Perceptions of Family Life

- Genetics and Extended Family Connections

- Utilizing Family Trees for Ancestral Links

- The Role of Younger Siblings in Family Dynamics

- Tracing Family History Through Oral Tradition and Genealogy

- Tracing Family Values Through Your Family Tree

- Exploring Your Elder Sister's Legacy in the Family Tree

- Connecting Daily Habits to Family History

- Documenting and Preserving Your Family's Legacy

- Navigating Online Records and DNA Testing for Family History

- Tradition as a Tool for Family Resilience

- Involving Family in Daily Life to Maintain Traditions

- Creating New Traditions for a Small Family

- The Role of Traditions in Family Happiness

- Family Recipes and Bonding at House Parties

- Quality Time: The Secret Tradition for Family Happiness

- The Joy of Cousins Visiting for Christmas

- Including Family in Birthday Celebrations

- Balancing Traditions and Unconditional Love

- Building Family Bonds Through Traditions

Looking for Speedy Assistance With Your College Essays?

Reach out to our skilled writers, and they'll provide you with a top-notch paper that's sure to earn an A+ grade in record time!

Family Essay Example

For a better grasp of the essay on family, our team of skilled writers has crafted a great example. It looks into the subject matter, allowing you to explore and understand the intricacies involved in creating compelling family essays. So, check out our meticulously crafted sample to discover how to craft essays that are not only well-written but also thought-provoking and impactful.

Final Outlook

In wrapping up, let's remember: a family essay gives students a chance to showcase their academic skills and creativity by sharing personal stories. However, it's important to stick to academic standards when writing about these topics. We hope our list of topics sparked your creativity and got you on your way to a reflective journey. And if you hit a rough patch, you can just ask us to ' do my essay for me ' for top-notch results!

Having Trouble with Your Essay on the Family?

Our expert writers are committed to providing you with the best service possible in no time!

FAQs on Writing an Essay about Family

Family essays seem like something school children could be assigned at elementary schools, but family is no less important than climate change for our society today, and therefore it is one of the most central research themes.

Below you will find a list of frequently asked questions on family-related topics. Before you conduct research, scroll through them and find out how to write an essay about your family.

How to Write an Essay About Your Family History?

How to write an essay about a family member, how to write an essay about family and roots, how to write an essay about the importance of family, related articles.

.webp)

Understanding how your family's cultural upbringing shaped your own

By Shamima Afroz

- X (formerly Twitter)

One weekend when I was 14, I anxiously sat on the couch with my parents watching TV, waiting for an ad break to ask a question I had been dreading.

But my nerves got the best of me, and my well-rehearsed plea to attend my friend's birthday sleepover turned into word vomit.

Before I could finish, my parents shut it down.

"Didn't you see Ashley last week? Will there be alcohol? Drugs? Why do I want to sleepover at someone else's house? Don't you have exams soon?"

They didn't say the word, but I knew their answer was no.

Growing up with traditional Bangladeshi parents, this was one of many parties, school discos, sleepovers, camps and weekend coast trips I had to miss — events I saw as rites of passage for my Aussie friends.

I should note that although my parents were strict, they were never short of giving us unconditional support, care and love growing up. My parents encouraged my brother and me to make the most of all the privileges we had access to growing up in Australia – however, within their boundaries.

For my parents, setting rules and keeping a tight rein on us was one way to preserve culture and tradition while they tried their best to balance two cultures: one they were so familiar with yet so far away from, with another that was foreign and unknown.

Understanding your family's cultural upbringing

Your parents' identity, shaped by their own culture, plays a vital role in their parenting practices.

"People learn how to be parents from the type of parenting they received," says counsellor Sandi Silva, who specialises in culturally sensitive therapy.

Both my parents grew up in Bangladesh, where it is common for parents to make decisions for their children without much input or consultation.

This power imbalance in the family often means children are expected to comply with their parents' decisions without much room for negotiation. Pushing back or questioning the decision is considered rude and an act of disobedience.

Additionally, some of my parents' decisions or expectations of their children were at times driven by a need to be seen or accepted by their Bangladeshi community. There's a common Bangla saying, "manush ki bolbe?", which translates to "what will people say?"

"One main driver for immigrant parents to be strict is fear — fear of the unknown, fear of losing cultural identity, or fear of losing face within their community," explains Ms Silva.

As I got older, pushing back against my parents' expectations became more difficult, but necessary.

In my early 20s, when most of my Bangladeshi friends were getting married, I decided to quit my secure and well-paying job to volunteer in a developing country for a year.

This life decision didn't make sense to my parents, and they were not on board. One of their main concerns was what the Bangladeshi community might think. Their unmarried, 25-year-old spinster daughter quit her job and left her parents behind to live on her own in another country. Manush ki bolbe?

By pushing back and following my own path, I embraced a culture that wasn't prescribed by my parents or the expectations of the community I grew up in.

In doing so, I became friends with people from different backgrounds with different perspective on life. I listened to their stories, learnt about their culture, and shared my own with them. In the process, I began to understand and appreciate my own culture and identity.

Striking out and making your own friends

Neela*, who moved to Australia from Bangladesh when she was 18 months old, found individuating from her conservative parents took time.

"They always told me that as a Muslim-Bangladeshi, I was different to my Australian peers, and therefore should act and think differently.

"I felt like I didn't belong in either culture and desperately wanted to fit in. This only emboldened my curiosity and secret rebellion."

From her early adult years, Neela has tried to distance her upbringing in her own friendships.

"My relationships now are based completely on my values and preferences, rather than the version my parents approve," she says.

The more emphasis a family has on passing down specific cultural and religious traditions, the higher the concern about losing face in front of family members or their community, explains psychologist Monique Toohey.

"In these circumstances, parents are less likely to encourage their children's development of friendships or intimate relationships with members of different outgroups."

For my parents, perhaps limiting my interactions with my Australian peers growing up was a way for them to protect me from the 'unknown' or from losing my Bangladeshi cultural identity.

'I always did what my parents wanted me to'

Samira*, another first-generation Bangladeshi-Australian woman, tells me of her experience growing up.

"I always did what my parents wanted me to do — from school, to work, to marriage. Mainly because I didn't want to disappoint anyone, but I also didn't know what I wanted."

Now as a wife and a mum, Samira says she struggles making decisions, and often turns to her parents or husband for advice.

"If you have always had decisions made for you and weren't given the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them growing up, then it can cause a real sense of dependence as an adult," explains Ms Silva.

It can also cause a difficulty connecting with your authentic self — and you can struggle distinguishing your own voice.

Trust your own voice and have compassion

"The process of unlearning who you were told to be and uncovering who you truly are can be a confusing yet empowering process. Taking the time to introspect is key," says Ms Silva.

She suggests asking yourself: "What old stories and messages am I still carrying from my upbringing? Is this serving me or limiting who I want to be?"

"A big advantage of looking inward and developing your own sense of self and values is that you develop more self-awareness and have more conscious and genuine interpersonal relationships," she says.

"Trust that you are capable of having a voice that matters. Have compassion for yourself and the experiences you found a way to live through, and if it helps your healing, have compassion for your parents' best attempts at raising you."

I embraced my Bangladeshi culture, but I also learned it was OK to form my own cultural identity that served me, even when it differed to my family's.

And my parents found ways to compromise.

Instead of letting me go to Ashley's sleepover that day when I was 14, they suggested I invite some friends to our place instead.

Our Saturday started with my dad dropping us off at the cinema to watch a 10am screening of Coyote Ugly, then ended in prank calls and choreographing dances to Destiny's Child. This was my parents' way of letting me embrace Aussie culture within their protected boundaries — and for that, I'm still grateful.

* Names have been changed for privacy.

ABC Everyday in your inbox

Get our newsletter for the best of ABC Everyday each week

Related Stories

'the world notices you're an interracial couple before you do'.

When you date within and outside your culture

How having a diverse range of people in your life changes you

Think online dating is hard? Try being a woman of colour

'She often sees things I can't': How reconciliation can start with friendship

Manimekalai married a man her parents approved. Here's what she thinks after her divorce

'Hot for an Asian': Dealing with racism in gay online dating

'Nerdy' stereotypes and cultural anxiety: Dating as an Asian-Australian male

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4: Influences of Family, Society, and Culture on Childhood

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 64519

- Susan Eliason

- Bridgewater State University

Learning Objectives

This week you will:

- Describe and analyze the influences of family, society, and culture influence the lives of children.

Introduction

How are childhoods influenced by nature and nurture? This week we will consider how family society and culture influence the lives of children. You will explore how the natural sciences (biology) and social sciences (anthropology, psychology, social work, and sociology) study these influences on children. We will use an interdisciplinary approach to learn more about the topic of sexuality. I like to use Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory to illustrate how the influences of nurture impact childhood. Watch Urie Bronfenbrenner Ecological Theory explained on You Tube on Blackboard to learn more about this model . How might Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological theory help you study your research question or childhood in general ?

Terms and Definitions

Important concepts to look for in this chapter:

- Socialization: the process where children learn to meet the expectations of and how to fit into a society.

- self-chosen and self-directed

- an activity in which means are more valued than end

- structure, or rules determined by the players

- imaginative, non-literal, mentally removed in some way from “real” or “serious” life

- involves an active, alert, but non-stressed frame of mind. (Gray, 2008)

- Competence: The ability, capacity, or qualification to perform a task, fulfill a function, or meet the requirements of a role to an acceptable standard.

- Cultural Relativism : a person’s beliefs and activities should be understood based on that person’s own culture.

- Developmentalism : The behavior of children is shaped by physical, psychological, and emotional development. Maturity is determined by age and stage of development.

- Diversity : There are many different types of childhood.

- Ethnicity : The culture of people in a given geographic region, including their language, heritage, religion and customs. To be a member of an ethnic group is to conform to some or all of those practices. Race is associated with biology, whereas ethnicity is associated with culture.

- Familialization : the caring of children in individual households and homes by family members rather than in state institutions.

- Gender : The condition of being male, female, or neuter. In a human context, the distinction between gender and SEX reflects the usage of these terms: Sex usually refers to the biological aspects of maleness or femaleness, whereas gender implies the psychological, behavioral, social, and cultural aspects of being male or female (i.e., masculinity or femininity.) [American Psychological Association, 2015]

- Friendship : Children’s affective social relations with their peers and others.

American Psychological Association. (2015). APA dictionary of psychology (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

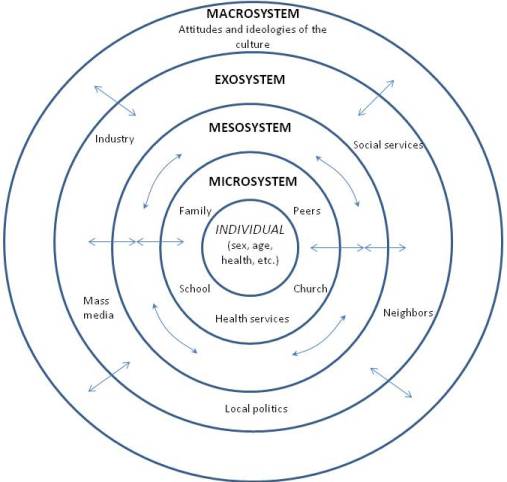

Ecological Systems Theory – used often in Social Work

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005) developed the ecological systems theory to explain how everything in a child and the child’s environment affects how a child grows and develops. The theory is illustrated in the figure below. This chapter will concentrate on the the Micro and Mesosystem levels. I find this model helpful in understanding the influences of nurture on childhood.

The microsystem is the small, immediate environment the child lives in. How these groups or organizations interact with the child will have an effect on how the child grows; the more encouraging and nurturing these relationships and places are, the better the child will be able to grow. Furthermore, how a child acts or reacts to these people in the microsystem will affect how they treat her in return. Each child’s special genetic and biologically influenced personality traits, what is known as temperament, end up affecting how others treat them.

The mesosystem , describes how the different parts of a child’s microsystem work together for the sake of the child. For example, if a child’s caregivers take an active role in a child’s school, such as going to parent-teacher conferences and watching their child’s soccer games, this will help ensure the child’s overall growth.

The exosystem includes the other people and places that the child herself may not interact with often herself but that still have a large effect on her, such as families workplaces, extended family members, the neighborhood,.

The macrosystem , which is the largest and most remote set of people and things to a child but which still has a great influence over the child. The macrosystem includes things such as the relative freedoms permitted by the national government, cultural values, the economy, wars, etc.

Chronosystem developmental processes vary according to the specific historical events that are occurring as the developing individuals are at one age or another. Moreover, cultures also are continually undergoing change.

As you read and explore the topics in the chapter, think about how the influences impact children.

Nature and Nurture Shape Childhood

Now, let’s use the concept of sexuality to see how nature and nurture are interconnected.

Nature and nurture, biology and culture, work together to shape human lives. Nature and nurture are intertwined, processes.

- Do you assume biology (nature) is destiny that may be minimally modified by culture (nurture, or environment) throughout childhood?

- Do you assume environment (nurture) is a more important factor in shaping individual psychology than biology (nature)?

- Specifically, what is the relationship between biology and culture with respect to sexuality ?

The biological features of sex and sexuality are determined by chromosomes and hormones such as testosterone, estrogen, and progesterone. Biologically, there are more than 2 sexes – chromosomes which can be XX, XY, XXX, XXY, XO, XYY. XX is female and XY is male; usually if the Y exists the person is generally seen as male. O produces ambiguous sexual features. Hormones and sex are apparent at seven weeks in utero.

The difference between sex and gender is: sex is male or female and is biological . Gender is meaning given to biological sex by culture . We develop a gender identity which is how an individual identifies as masculine or feminine. Gender is a spectrum. We learn gender roles during childhood, such as, appropriate behaviors and work or division of labor

- Can a male can be a female?

- Is it only one or the other?

- Are gender and sexuality fluid over a lifespan?

- Can they change? Is sex a spectrum like gender?

- nadleehi (born male functions in women roles)

- Dilbaa (born female functions in male role)

I challenge you to reflect on gender and sexual diversity. Imagine you have a child who is born with an intersex anatomy [XXX, XXY, XO, XYY] You read up on diagnostic testing and the recommendations of the Intersex Society of North America , that suggest you give your child a binary gender assignment (girl or boy). Do you follow the advice of the ISNA? Why/why not? If not, what do you name your child? How do you dress your child? As your child acquires language, what pronouns do you use for your child? Would you use he, she, ze, or they? You inform yourself and read about current possibilities at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Resource Center’s article on Gender Pronouns What is ‘competency’?

Families should help children mature and become competent. The concept of competency is related to the concept of agency discussed in Chapter 2. Listening to children and respecting their opinions can contribute to their personal development. A supportive environment can lead to children to making better decisions, prepare them to participate in society and strengthen their accountability. Children’s competency or abilities may be recognized, ignored, encouraged or inhibited. The supporting adults’ willingness to respect children’s decisions will determine whether the children’s choices are honored Figure 1, described by Alderson (1992) and illustrated by Orr (1999), illustrate the internal and external variants that may influence a child’s competency. (van Rooyen, Water, Rasmussen, & Diesfeld, 2015)

When we consider competence, we should also think about cultural relativism, are there universal standards we can apply to childhood? Is the UNCRC a set of universal standards? Implementation of the UNCRC can be difficult when violations of the rights of children are justified on the basis of cultural practice. Think about the practice of female circumcision.

In 1996, a 17-year-old girl named Fauziya Kassindja arrived at Newark International Airport and asked for asylum. She had fled her native country of Togo, a small west African nation, to escape what people there call excision.

Excision is a permanently disfiguring procedure that is sometimes called “female circumcision,” although it bears little resemblance to the Jewish ritual. More commonly, at least in Western newspapers, it is referred to as “genital mutilation.” According to the World Health Organization, the practice is widespread in 26 African nations, and two million girls each year are “excised.” In some instances, excision is part of an elaborate tribal ritual, performed in small traditional villages, and girls look forward to it because it signals their acceptance into the adult world. In other instances, the practice is carried out by families living in cities on young women who desperately resist. For more information read the World Health Organization Fact sheet (2017) Female genital mutilation

Cultural relativism would accept the practice. Does the UNCRC allow the practice?

Role of families

As discussed during Week 1, we see the world through our cultural lens, we are cultural conditioned. Conditioning happens at different levels

- Societal [Macrosystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory]

- Institutional [Exosystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory]

- Group [Microsystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory]

- Individual [The center of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory]

The group level or microsystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory includes families. One of the major influences on childhood is families. The family is the principal institution responsible for childbearing and childrearing so society assumes a more passive role in facing the commitments and costs connected to childhood. The UNCRC gives all children the right to a family. The right to a family allows children to be connected to their history, and it offers a protective perimeter against violation of their rights. Children separated from their families can become victims of violence, exploitation, trafficking, discrimination and all other types of abuse. However, sometimes the family which should be protecting the child is in fact inflicting the abuse.

Families are the first to have the power to act on behalf of the child and ensure their rights are respected. Hopefully, their objectives are to protect the child and to secure the child an education, development, security, health and morality. To achieve these objectives, a family should provide supervision by controlling the child’s comings and goings, relationships, and communications. For example, they may forbid the child from maintaining relationships with certain persons that they believe are not in his or her best interest. Families make educational decisions including religious and sex education and decide on the health care to give their child. Families are responsible for the needs of the child, such as food, clothing, shelter, educational costs, vacations (if possible), and health coverage. What happens to children when families find it difficult to provide basic needs? Families often struggle with finding time, money and resources to effectively parent. In the US, families may have difficulty earning a living wage, finding social supports, securing affordable housing, high-quality child care and paid family leave. It can be difficult to provide a nurturing environment all children need and may result in neglectful or abusive environment.

Did you know that in 2016 the relative poverty rate for children 0-5 in the U.S. was more than 25%; for ages 0-18 years the rate was about 22%. In other words about 1 out of 4 young children in the United States live in poverty. What changes in the US might lower the child poverty rate? How can we create environments that enrich the lives of all young children and their families, allowing them the opportunity to realize their full human potential?

A former student shared: So I definitely think that the Department of Children and Families (DCF) needs to be more pro-active in checking in on families, especially families living under the poverty line, to ensure they are receiving assistance if needed and that the child is living in a stable home where he/she is healthy and can thrive. I agree with the student that all children deserve a safe and healthy environment and our society should support them. I wonder why income often is the only resource considered when giving families assistance. To help you think about interacting with diverse families, please read the following scenario:

You are a teacher in the 4-year-old room at Kids Place child care center.Daequan and Mathew are two children in your class. Both were born at 30 weeks’ gestation and had hospital stays of about 6 weeks. Both are in generally good health and are monitored for respiratory illnesses. For the most part, the boys are reaching their developmental milestones, with slight delays in language/emotional development.

At the present time, Daequan and his mother, Shania, are living in a homeless shelter. Their home burned down 2 weeks ago and they had nowhere else to go. Matthew is part of an intact family. Ralph and Sue are his parents, and he has an older brother, Nick. The family lives in an affluent community a mile from Kids Place.

- Which child would appear to be experiencing a greater number of risk factors that can affect his development?

- With which family would it appear to be easier to develop a partnership? Why?

Then you learn:

Daequan and his mother have a number of extended family members available for support and will be moving into an apartment within a month’s time. Shania has contacted a number of local agencies for assistance to rebuild her and her son’s lives.

Matthew’s father travels 3 weeks out of the month. Sue is on medication for depression and has recently started drinking around the boys during the evenings and weekends. She turns down offers of help from her friends and family and tells them everything is fine with her marriage and her ability to raise her sons.

What questions might you or others ask to find out “the whole story”? Ruby Payne (2009) describes the nine resources by which one negotiates their environment. Poverty is when you need too many of these resources, not just financial.

- Language (ability to speak formally)

- Support systems

- Relationships/role models

- Knowledge of middle class rules

How do you and other discover what resources are available to children and families? How do you build on a families strengths. Everything that improves the economic security, safety and peace of mind of families improves parenting—and increases children’s chances for growing into healthy, compassionate and responsible adults. These include living wages and reliable hours, secure housing, high-quality childcare, paid family leave, safe neighborhoods, flex time, desegregation and social inclusion. Which disciplinary perspectives might help you understand family influences on childhood?

Friendships

Besides family and other adults in the culture, peers can be an influence on childhood. Recent research shows the importance of friendship, and its impact on mental and physical health. Preschool friendships are helpful in developing social and emotional skills, increasing a sense of belonging and decreasing stress. (Yu, Ostrosky, & Fowler, 2011). People who feel lonely or socially isolated tend to be more depressed, have more health issues and may have a shorter lifespan. (Lewis, 2016). Having a support system can help us handle hardships.

Selman and colleagues identified five successive stages in how children view friendships. The chart below illustrates the theory. Why might it be helpful to understand the stages of friendship? How would it inform your possible work with children and families?

Play in one way in which families and peers interact with the child. Play is essential to the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being of children and youth and is one of the rights in the UNCRC. Article 31 of the UNCRC states:

1. Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.

2. Parties shall respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activity.

It is through play that children engage and interact in the world around them at an early age. Play allows children to create and explore a world they can master, conquering their fears while practicing adult roles, developing new competencies that lead to enhanced confidence and the resiliency they will need to face future challenges.

Child-directed play allows children to practice decision-making skills, move at their own pace, discover their own areas of interest, and ultimately engage fully in the passions they wish to pursue. When play is controlled by adults, children follow adult rules and lose some of the benefits child-directed play offers them, such as developing creativity, leadership, and group skills. Play builds active, healthy bodies. Play is a simple joy that is a cherished part of childhood. However, play can be challenged by child labor and exploitation practices, war and neighborhood violence, living in poverty, over scheduling, and pressures on children to achieve. (Ginsburg, 2007)

A wonderful resource to learn more about play is available on the National Association for the Education of Young Children website . After reviewing the information on the website reflect on these questions:

How can we enhance the opportunities for balance in children’s lives that will create the optimal development to prepare them to be academically, socially, and emotionally equipped for future growth? How can we make sure we play enough?

Genes make us human, but our humanity is a result of the complex interplay of biological and cultural factors. This week you read about the of the influences of family, society, and culture as they bear on the lives of children. As you discuss, try to answer: How are interactions between children and adults shaped, modified and redefined by overlapping institutional and organizational forces such as the economy, family, education, politics, religion, and so on? What is the impact of experiences in childhood later in life?

After reading this chapter and completing the activities you should be able to

- Describe and analyze the influences of family, society, and culture influence the lives of children as seen the discussion and assumptions inventory

Reflection and Discussion

This week we explored the influences of family, society, and culture influence the lives of children. Reflect on your understanding of these ideas:

Now you are ready to type in Pages or in a Word document, a minimum of 3 paragraphs explaining your connections, extensions, and curiosities. Copy and paste your response in the Blackboard discussion or in class

Collaborative Research Project

So far during this course, you brainstormed a research question and should be using at least 2 disciplines to examine the question. Your work this week is to present your preliminary findings as a draft of the final project. Soon you will submit a video or some other oral report as well as written materials. You will likely use the same format as the Assumption Inventory. The report should

- Summarize your research question ( What ). Remember to relate the question to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

- Present the research from different disciplines that help to answer or explain the question. ( So What )

- Apply criteria listed in the grading rubrics to create a persuasive presentation

- Discuss possible solutions. (This is the start of the Now What of the project)

- Complete a peer feedback questionnaire.

Ginsburg, K. R. (2007) The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds. Pediatrics, 119, (1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2697 Available at http://pediatrics.aappublications.or...1/182.full.pdf

Lewis, T. (2016). This common characteristic may be as big a risk to your health as smoking. Business Insider Website available at: http://www.businessinsider.com/how-social-isolation-affects-your-health-2016-1

Selman, R. (1981). The child as a friendship philosopher. In S. A. Asher & J. M. Gottman (Eds.), Development of Children’s Friendships. (pp. 250-251). (Original work published 1978) Retrieved from http://books.google.com

van Rooyen, A., Water, T., Rasmussen, S., and Diesfeld, K. (2015). What makes a child a ‘competent’ child? The New Zealand Medical Journal, 128, (1426). Available at www.nzma.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/46110/van-Rooyen-1628FINAL1426.pdf

Yu, S. Y., Ostrosky, M. M. & Fowler, S. A. (2011). Children’s Friendship Development: A Comparative Study. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 13 , (1).

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Mind & Body Articles & More

How parents influence early moral development, a new study finds that the key to raising moral kids lies with the parents' sense of empathy and injustice..

Parents: Do you want to raise a child with a strong sense of right and wrong? You might want to start by cultivating your own morality—as well as your own empathy .

A new study from the University of Chicago suggests that parents’ sensitivity to both other people’s feelings and to injustice may influence early moral development in their children.

Developmental neuroscientist Jean Decety and his colleague, Jason Cowell, brought a group of one year olds into the lab to test them on their reactions to moral situations. The seventy-three toddlers watched animated videos in which characters engaged in helping and sharing (prosocial) behaviors or pushing, tripping, and shoving (antisocial) behaviors while the researchers monitored the toddlers’ eye movements and measured their brain wave patterns using an electroencephalogram, or EEG.

Afterwards, the researchers offered the children toy figures representing the two “good” and “bad” onscreen characters and noted which the toddlers preferred, based on their reaching behavior. The toddlers also played a sharing game, in which they were given two toys to play with and then an asked to share one.

Prior to the experiment, the children’s parents filled out questionnaires measuring their values regarding empathy, justice, and fairness. The parents also answered questions about their children’s observed temperaments, as well as giving general demographic information.

Results of the researchers’ analyses showed that all the toddlers experienced different brain-wave patterns when witnessing pro-social versus antisocial behavior, and they tracked pro-social characters with their eyes longer—a finding that replicates other studies suggesting that kids, even from a young age, seem to prefer moral characters.

Yet, those differences in brain wave patterns for good and bad characters didn’t translate into toddlers reaching for the pro-social toy figure—in fact, just as many reached for the antisocial toy.

Instead, the toddlers who preferred the “good” toy had a distinct brain wave pattern in their EEG—one that included larger spikes of activity at the 400-millisecond-mark post-witnessing the animated good and bad behavior. And, in later analyses, the researchers discovered that this distinct spike in activity was predicted by the parents’ sensitivity to justice—a finding that surprised Decety.

“All babies make a distinction between good and bad—this has been shown by many studies,” he says. “But, this second response in the brain, the one that’s sensitive to a parent’s views toward justice, we think it is connected with more complex types of reasoning.”

The spike in brain activity seems to indicate that the toddlers are appraising, rather than just paying attention to, the good and bad behavior they’ve seen, says Decety. Still, how a parent’s views could impact that process isn’t clear at all. Decety speculates that it may be because of genetics and biology, or perhaps a combination of influences from the baby’s social environment and the genes passed down to them.

“As we’ve learned over the last 50 years of research, it’s almost never just one or the other,” says Decety. “It’s almost always an interaction between the two.”

Parental dispositions also seemed to impact sharing in the toddlers. The researchers found that higher levels of parental cognitive empathy, or the ability to take someone else’s perspective, as well as higher levels of baby self-regulation—their ability to soothe themselves, for example—predicted increased sharing behavior in the sharing game. While it makes some sense that babies who can self-soothe would be better at sharing—after all, says Decety, sharing is hard for babies, so soothing themselves could mitigate the emotional upset—it’s less clear how parental empathy impacts this behavior. Again, it could be genetic, or socially-influenced, or both.

Either way, it appears that the building blocks of moral behavior—reaching out to good people and being willing to share with others—are somewhat idiosyncratic and not equal in all kids. This goes against some of the current thinking on moral development, says Decety.

“Usually when you read developmental studies, it seems as if all babies are alike,” he says. “But our study shows that how morality develops is a little more sophisticated, more nuanced than we thought. Even at this very early age, we see these individual differences.”

Perhaps surprisingly, parental emotional empathy—the ability to share the emotions of another person—did not seem to influence sharing behavior in their toddlers. However, this finding does mirror some of Decety’s other research with adults, which found cognitive rather than emotional empathy predicts their sense of morality, justice, and fairness.

Of course, this is only one study. But Decety will soon be analyzing results from another study measuring brain wave patterns in toddlers witnessing acts of fairness and unfairness. And he hopes to analyze DNA samples from parents to see if there may be a genetic component that accounts for differences in how babies react to moral situations.

His goal is to better understand the mechanisms involved in moral development so that, eventually, we might shape its trajectory in positive ways.

“If we want our kids to be sensitive to justice—which I believe we do, if we want to live together in peace—and it turns out that the way that we handle or care for our kids can affect their sense of justice from very early on, then we will want to pay attention to that,” he says. “That’s good for everybody, for the world.”

About the Author

Jill Suttie

Jill Suttie, Psy.D. , is Greater Good ’s former book review editor and now serves as a staff writer and contributing editor for the magazine. She received her doctorate of psychology from the University of San Francisco in 1998 and was a psychologist in private practice before coming to Greater Good .

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

How Today’s Parents Say Their Approach to Parenting Does – or Doesn’t – Match Their Own Upbringing

Illustrations by Hanna Melin

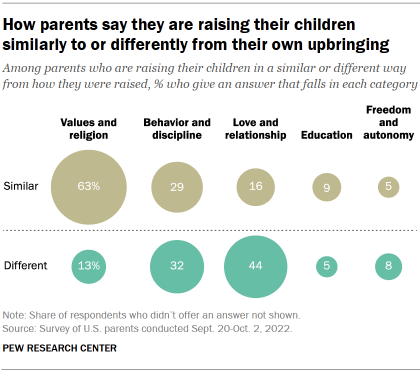

How are U.S. parents raising their children these days, and how does their approach compare with the way their own parents raised them? To answer this, Pew Research Center asked over 3,700 parents nationwide: Compared with how you were raised, are you trying to raise your children in a similar way or a different way?

Overall, roughly as many U.S. parents say they are raising their children similarly to how they were raised (43%) as say they are trying to take a different approach (44%). About one-in-ten parents (12%) say they’re neither trying to raise their children similarly to nor differently from how they were raised.

More from this survey: Parenting in America Today

When asked in an open-ended question to describe the specific ways in which they’re raising their children, parents’ responses touched on many different dimensions of family life, with some including details from their own upbringing. Five distinct themes emerged from the parents’ open-ended responses. Among parents who say they’re raising their children similarly to how they were raised, the dominant theme focused on values and beliefs that are important to their family. For those who are taking a different approach to parenting compared with their own upbringing, a focus on love and their relationship with their children was the most common theme.

For this analysis, we surveyed 3,757 U.S. parents with children younger than 18 from Sept. 20 to Oct. 2, 2022. Most parents who took part are members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This survey also included an oversample of Black, Hispanic and Asian parents from Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel, another probability-based online survey web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses. Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents were first asked if they are trying to raise their children similarly to or differently from how they were raised. Respondents were then asked an open-ended question based on their response to describe the ways in which they are raising their children similarly to or differently from the way they were raised. Overall, 87% of respondents provided an answer to the open-ended question they received. Center researchers developed a coding scheme categorizing the responses to both questions, coded all responses, then grouped them into the five themes explored in the data essay.

The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

Values and religion

Among parents who say they are raising their children similarly to how they were raised, 63% mentioned something having to do with values and religion when asked to elaborate. Parents who say they are raising their children in a different way than they were raised were less likely to focus on this theme (13% mentioned it).

Responses for parents who are raising their children similarly tended to center around instilling respect for others, good morals, and a strong work ethic. Some also described principles to stand by, like integrity and honesty, while others mentioned certain civic or ideological values, such as raising their kids to be good citizens or instilling conservative values.

“Instill morals, ethics, a sense of right and wrong, work ethic, respect for others, faith, and an understanding of correct principles that will help them succeed and to help others to succeed in life. I was raised the same way.”

Father, age 39

“I am not taking my kid to the church, and I am trying to teach my kid to be open and friendly to people ‘different’ than her.”

Mother, age 44

A significant share of these parents (17%) specifically mentioned religion, with many saying that they want to pass along the same religious beliefs and values their parents instilled in them. These parents pointed to faith and spirituality as a focus in raising their kids, just as it was when they were growing up.

Among parents raising their children differently from how they were raised, 7% mentioned that they want to instill different values in their children from the values they were raised with. These range from compassion to open-mindedness, which some parents feel were not among the values their own parents taught them as children.

The same share talked about religion when detailing how they are trying to raise their children differently. Some mentioned adding religion into their children’s lives (where it may have been absent in theirs), while others emphasized limiting or removing the amount of religious influence compared with what they experienced growing up.

Love and relationship

Among parents who say they are raising their children differently from how they were raised, 44% gave answers that focused on love and their relationship with their children. This theme was less common among parents who are raising their children similarly to their own upbringing (16% mentioned it).

For parents who say they’re taking a different approach in raising their children, many said they are giving them more love and affection than what they received as a child; they want their children to feel like they are growing up in a loving home where there is a lot of support and outward praise. Parents who are raising their children in a similar way to how they were raised tended to talk about providing their kids with a loving household or giving them unconditional love, either through verbal affirmation or other displays of affection.

“I always knew that if I needed my family that they would be there for me no matter the situation. I always had their love and support. I want them to know that it’s never a situation that they can’t come to me.”

Mother, age 37

“I was never shown affection or told that my parents loved me. I am trying to show more love in my caregiving.”

Being an involved parent was a sentiment expressed by both groups of parents. Among those who say they’re taking a different approach to parenting, some said they want to be more present in their kids’ day-to-day lives than their parents were. Both groups of parents talked about the importance of having family dinners, supporting their children in their extracurricular activities, and generally spending time with them on a regular basis.

Parents who are raising their children differently from how they were raised expressed some unique – and often poignant – things they are trying to do. This includes better lines of communication with their children – not yelling as much and listening more. Additionally, some parents directly referenced having open and honest conversations with their children, sometimes even surrounding current societal topics .

Other parents said they are focusing on cultivating an understanding relationship in raising their kids differently and underscored accepting their children for who they are. A handful of parents mentioned they want their children to grow up confident and comfortable with themselves, and others focused on providing their children with emotional support and being more in touch with their feelings than their parents were.

Behavior and discipline

Whether they’re trying to raise their kids similarly to or differently from how they were raised, comparable shares of parents pointed to expectations for their children’s behavior and discipline when asked to say more about their approach to parenting (29% and 32%, respectively).

Parents who say they’re raising their kids similarly often emphasized responsibility, manners, respecting rules and doing household chores. Some also pointed to setting boundaries, holding their children accountable, and not tolerating unacceptable behaviors such as lying.

Many parents who say they’re raising their children in a different way focused on their parenting style, approaches to disciplining their kids, and setting expectations for behavior. Some mentioned taking a gentler approach to parenting, while others said they are firmer with their children than their own parents were with them. About one-in-ten of these parents specifically mentioned that they would not use corporal punishment when discipling their children.

“I was raised in a traditional environment and my parents were principled and strict disciplinarians. I believe children benefit and turn out well in such environments.”

Father, age 45

“I was raised in a time where physical punishment was more common and much more socially accepted, but I almost immediately strayed away from that when raising children of my own.”

Mother, age 51

In reflecting on their parenting, 9% of parents who say they’re raising their children similarly to how they were raised mentioned education, as did 5% who say they’re raising their children differently. Both sets of parents discussed the importance of ensuring that their kids work hard and do well in school, along with the type of schooling they want their kids to have, such as homeschool or private school. Parents who are raising their children in a similar way emphasized the value and importance of education overall and expressed high academic expectations for their kids. Those raising their children differently spoke about education in the context of giving their kids a better education than they had, while a few mentioned giving their children a little more leeway on academics because they grew up with strict parents.

“My mother always talked to me about bullies, she encouraged my education and prepared me for school, she attended school functions/meetings, taught me about God, took out time to meet my friends, etc. I do all these things.”

Mother, age 41

“My parents were … unable to afford to put me in any classes or lessons. They valued academics above all else. While I think academics is very important, I would like my children to have a more well-rounded upbringing.”

Mother, age 40

Freedom and autonomy

Parents also commonly mentioned approaches to parenting that give their children the freedom to just be kids and the autonomy to make their own choices, regardless of whether they’re raising their children in a similar or different way from how they were raised. Parents in both categories described a variety of approaches related to autonomy: allowing their kids to learn and grow from their mistakes, giving them the freedom to make their own choices, and wanting them to think for themselves. In particular, some parents who are raising their children differently discussed how they want their children to have more independence.

“[I] encourage them to think independently, allow them to be creative and grow, give them opportunities to explore the world in a safe and supported way.”

Father, age 42

“I try to give my children more trust, let them make more of their own decisions. I actively try to help them reach their own conclusions rather than forcing my beliefs on them. I see myself as a partner with them rather than a boss.”

Mother, age 39

In their own words

Below, we have a selection of quotes that describe the many ways that parents are approaching raising their children today – both similarly to and differently from how they were raised.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

20 Engaging Essays About Family You Can Easily Write

Discover 20 essays about family for your next essay writing project.

From defining the family to exploring problems within modern families, this personal topic lends itself well to essay writing. If you are preparing a personal essay or were assigned to write one on this topic, good news. You can easily draw on a wealth of sub-topics and themes about the family, as you develop your piece. But if you have trouble getting started, here are 20 ideas for essays about the family.

For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .

1. Why Siblings Should Be Your Best Friends

2. what is a family, 3. how family culture is established by a nuclear family, 4. the importance of family in child rearing, 5. how my family made me a better person, 6. why i love my family, 7. why my mom/dad/grandparent is my role model, 8. the effect of dysfunctional families on teenagers, 9. a sociological approach to defining family, 10. the influence of extended family on a child’s life experiences, 11. how popular culture portrays the happy family, 12. how my dysfunctional family defined my character, 13. how family has changed in american society, 14. is family changing or facing a state of decline, 15. the role family holds in everyday life, 16. comparing the family dynamics between two different cultures, 17. how my multi-cultural family gave me the best of both worlds, 18. unique challenges faced in single-parent families, 19. my most vivid family memory, 20. the challenges of being the youngest or oldest in the family.

A loving family is a beautiful gift, and with it often comes the gift of siblings. You could develop an essay on why siblings should be an individual’s best friends. When the relationship between them is loving and supportive, siblings are always around and able to help individuals through challenging life experiences.

This stands in stark contrast to the friends made in high school and even college. While some people will walk away with lifelong friends, life’s circumstances often pull friends apart. Family is forever, and people should work to develop those relationships. Looking for more? See these essays about brothers .

The dictionary defines a family as “a social group made up of parents and their children” or “a group of people who come from the same ancestor.” Yet this is a very narrow definition of family. Could you define it in another way? Are there people who you consider “family” who are not actually related to you by blood?

This essay idea gives you quite a bit of room for interpretation. Decide how you will define family, and then use the essay to support your choice. Then, discuss different ways family can look in society.

If you need some inspiration, check out our guide to the best parenting books .

The nuclear family is the most basic family structure: parents and their children. This family system is critical to developing a family culture and passing it down to the next generation. Do you find that you highly value having a family night on Fridays? It is likely because that is something your parents showed you in your own family when you were growing up.

Your essay can define family culture and show how family life helps establish that and pass it down to children. This family essay can discuss the nuclear family’s role in teaching children about cultural and religious values. Finally, the essay can establish why family culture and passing it along to children is so important.

For more help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

Can children grow into reasonable and ethical grown-ups without a family? While it is possible, the reality is the most stable adults typically come from loving and supportive families. One of the primary roles of the family is the development and rearing of children.

The family is the child’s primary social group . Through the family, they develop socially, emotionally, physically, and intellectually. In some ways, the family is the first school that teaches them the most important principles of life for young children. In your essay, establish the fact that family is the foundation for strong adults because of its role in child-rearing and child development.

If you need to write a personal essay, you can look at your family’s role in making you who you are. Your family played a vital role in your upbringing, from teaching you your core values to supporting you as you developed into the adult you are today.

Remember that you don’t have to have a happy family to write this essay. Even if your family circumstances were challenging, you can find ways that your family of origin helped you improve yourself and become a better person.

This is another personal essay topic. On the surface, it seems easy, but if you are going to write a quality essay, you need to dig deep. What makes your family unique and special, and why do you love that?

Keep in mind that all families have quirks and even problems. Yet you love your family in spite of these and sometimes even because of them. Don’t be afraid to include these in your essay.

Think of your family and the leaders in it. Is there one that stands out for a particular reason? Have you modeled some of your own life on how that person lived theirs?

Whether you choose a parent or a grandparent or even an extended family member, look more closely at what makes that individual so important in your life. Then, in your essay, you can outline how you are trying to emulate what they did in their life to make you more successful in yours.

When families go through difficult times, the effect is not limited to those struggling the most. The whole family will suffer when parents are fighting or financial problems arise. Teenagers are particularly vulnerable to dysfunctional family dynamics. They may act out, experience depression, or feel pressured to lead the family when their parents are facing conflict.

This essay explores the effect of family problems on teenagers and their emotional or social development. Consider providing solutions that can help teens manage their challenging emotions even while dealing with the unique challenge of a dysfunctional family.

The definition of family is constantly evolving, but what does sociology say about it? This question could lead to an exciting and engaging essay as you dig into sociology to find your family definition. Based on most sociological definitions , a family is a group of related individuals connected by blood, marriage, or adoption. It may also mean people who live under the same roof.

Based on this definition, the word family has a distinct boundary. While close friends might be something you consider as family personally, sociologists will not define family in this way. Looking at the way sociologists, specifically, define family will give you quite a bit for your essay.

Much has been written about the nuclear family and its impact on the child’s development, but the whole family can have a role to play. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, and other extended family members can contribute to the life experiences of a child, and you can turn this into an interesting essay topic.

Use your essay to explore what happens when the extended family lives close by and what happens when they do not. You can look at how much of an influence the extended family has on a child’s development, and what increases or decreases that influence.

What does the happy nuclear family look like in television shows and movies? Is it usually a mother, father, and child, or are same-sex couples shown regularly? Do single-parent households get equal representation, or not?

This topic could be a fascinating one to explore in your essay. Once you establish the facts, you can discuss if this portrayal reflects real life or not. Finally, you can talk about whether or not the cultural portrayal of the family represents the type of family values the average family embraces.

Not everyone grows up in a happy, stable family, but sometimes bad times can improve someone’s character and give them the drive to be better. If you grew up in a dysfunctional family, you could show how that helped define your character.

In this essay, work to make a positive spin on your difficult situation. This topic can work well for a personal essay for college entrance or employment purposes.

Is the definition of family changing in American society? Some would argue that it is. While the mother, father, and children style family is still common, many other families exist now.

For example, we have an increasing number of grandparents who are raising their grandchildren . Single-parent families are also on the rise, as are families with a single parent who was never married to the other parent to begin with. Families with same-sex parents are becoming more common as well. Take your essay and define this change and how the nuclear family may look in the future.

Another take on the idea of the changing family dynamic s discussing whether or not families are changing, or if the state of the family is in decline. This essay topic will require some research, but you can explore whether families are breaking down or if they are simply changing.

If you decide that the family is breaking down, you can explore the reasons for this breakdown and its impact on society.

From bringing in the income that the family members need to live on to giving direction for the growth and development of children, the family holds a significant role in everyday life. You can explore this role in your essay and talk about the different components of life that the family controls.

For people who grow up in a stable environment, the family provides emotional support and improves overall well-being. It is also the source for moral development, cultural development, and work ethic development. It also provides for the physical safety and needs of the children. All of these lend themselves well to an essay topic.

While the main definition of family is nearly universal, the nuances of family dynamics change significantly from one culture to the next. For example, some cultures are highly patriarchal in nature, while others focus on maternal leadership. Pick a very different culture from your own, and then compare and contrast them in your essay.

For this essay, make sure that you look at differences as well as similarities. Do not disparage either culture, either, but rather focus on their differences positively. This essay works well if you have contact or knowledge of both cultures so that it can be a great choice for someone growing up in a multi-cultural family.

This essay topic is a twist on the previous one. In addition to comparing and contrasting the family dynamic of the two cultures, you can look at how that directly impacted you. What did you gain from each of the two cultures that merged in your home?

The personal nature of this essay topic makes it easier to write, but be willing to do some research, too. Learn why your parents acted the way they did and how it tied into their cultures. Consider ways the cultures clashed and how your family worked through those problems.

Single-parent families can be loving and supportive families, and children can grow well in them, but they face some challenges. Your essay can expound on these challenges and help you show how they are overcome within the family dynamic.

As you develop this family essay, remember to shed some positive light on the tenacity of single parents. There are challenges in this family structure, but most single parents meet them head-on and grow happy, well-balanced children. Remember to discuss both single fathers and single mothers, as single-parent families have both.

You can use this personal essay topic when writing essays about the family. Think back to your childhood and your most vivid family memory. Maybe it is something positive, like an epic family vacation, or maybe it is something negative, like the time when your parents split up.

Write about how that family memory changed you as a child and even in your adult years. Discuss what you remember about it and what you know about it now, after the fact. Show how that memory helped develop you into who you are today.

Are you the family’s baby or the oldest child? What challenges did you face in this role? Discuss those as you develop your family essay topic.

Even if you were the middle child, you can use your observations of your family to discuss the challenges of the bookend children. Do you feel that the baby or the eldest has the easier path? Develop this into a well-thought-out essay.

If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

Nicole Harms has been writing professionally since 2006. She specializes in education content and real estate writing but enjoys a wide gamut of topics. Her goal is to connect with the reader in an engaging, but informative way. Her work has been featured on USA Today, and she ghostwrites for many high-profile companies. As a former teacher, she is passionate about both research and grammar, giving her clients the quality they demand in today's online marketing world.

View all posts

- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7

- Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

Write an Essay about Family: From Introduction to Conclusion

Essay about the Family

Students have to write essays for a variety of goals. Often, students fail when asked to write about simple topics such as a friend, a hobby, or even their family.

It is due to a lack of understanding of the fundamentals of essay writing. Furthermore, few people anticipate that they may have to write such essays.

However, college is not all about research and analysis. Occasionally, students have to write easy essays to evaluate their mastery of the fundamentals. When it comes to style and arrangement, a family essay shares the same characteristics as other essays.

Why is Family a Good Topic for An Essay

Writing a family essay should be straightforward, but you must be well-prepared with the necessary material. Know what to put in your body.

Decide how much personal information about your family you are willing to share.

However, a family essay is both a personal and a narrative essay and can also be challenging.

On a personal level, you talk about your family, and on a narrative level, you briefly narrate your family to your audience.

When writing a family essay, it is important to determine what facts to include and what information to leave out. It keeps you from boring your audience by going into further detail. You should avoid revealing a lot of information about your family.

Think about your place in the family when writing a family essay. Are you the oldest, youngest, or somewhere in between? What this means to you and how it affects your family.

You have fun while explaining the family traditions that make you unique. Each family has a tradition that they enjoy observing and enhances their closeness.

Touch on the responsibilities or functions of each member of the family. You primarily discuss the kind of obligations that each family member has based on their age. Finally, explain how the responsibilities are handled and who is in charge of ensuring their fulfillment.

You can bring up family issues such as incompatible marriages and other disagreements that arise in any family.

Explain how your family handles such situations and how you restore communication within the family in a few words. This is a challenging topic to broach, but it is critical to your essay’s success. Do you have any family members of a different ethnicity or some who are not your blood relatives? Do you communicate with your relatives?

Explain your extended family’s relationship with you and what brings you together the most.

Consider your family bonding time. When do you spend time as a family bonding?

Describe how you and your family work together to make special occasions memorable. You can highlight family when writing about people who inspire you.

How to Write an Essay About Family

1. explain your topic about family.

Provide a brief background, context, or a narrative about your topic.

Describe where your subject is right now. Compare and contrast the past with the present. You can also tell a bad story or one that is based on gossip.

Retell the tale or the definition or explanation you provided with an uplifting end.

2. Craft your thesis about the family

Begin your paper with a compelling hook, such as a thought-provoking quotation. It serves to attract the audience’s attention and pique interest in your essay.

You should also come up with a thesis statement that is appropriate for your target audience. The thesis statement serves as a fast summary of your essay’s contents.

The introduction allows you to provide the reader with a formal presentation of your work. The section should stand out to grab the attention of your readers. Alternately, you may give a brief, straightforward explanation of the problem you have will discuss throughout your family essay.

This section also summarizes the approach you use to study the issue.

Moreover, it lays out the structure and organization of the body of the paper and the prospective outcomes. You never have a second chance to make a good first impression, so a well-written introduction is critical.

Your readers form their first perceptions of your logic and writing style in the first few paragraphs of your work.

This section helps in determining whether your conclusions and findings are accurate. A sloppy, chaotic, or mistake-filled introduction will give a poor first impression.

A concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will get the audience to respect your analytical talents, writing style, and research approach. Close with a paragraph that summarizes the paper’s structure.

3. Write your arguments about family

Expand the major themes into individual paragraphs to form the body of your essay. The thesis statement establishes the foundation of your argument. Begin each body paragraph with a topic sentence that includes a clear and concise explanation as well as details about your family.

This will allow your audience to learn more about you and your family.

Use transition sentences to let your readers know when you are introducing a new point in your argument. Cover each facet of your argument in a different paragraph or section, if your essay is lengthy. You should also logically discuss them, making connections where possible. Support your case by referencing previous studies.

Depending on your topic, you may use existing studies or experimental data, such as a questionnaire for evidence to support each claim. Without proof, all you have is an unsupported allegation.

4. Recognize counter-arguments

Consider the other side of the argument. It enables you to anticipate objections to your perspective, which bolsters your case. Your objective is to persuade the reader to accept the recommendations or claims made in your essay.

Knowing what you are suggesting and how your arguments support it will make it easier to express yourself appropriately.

Make a strong conclusion based on what you have learned so far. It is crucial to conclude your essay by explaining how the evidence you have presented backs up your claim. Also, illustrate how each point adds to the broader argument.

Everything in your paper must support your main point, from the literature review to the conclusion.

5. Cite and reference

Many academically approved citations forms exist, including MLA, APA, Chicago, and others.

You can choose from the popular styles or ask your institution which one they prefer. There is no need to quote information that is commonly known.

Facts and common knowledge have no copyright protection; thus, you can use them freely. Each citation in the text should correspond to the bibliography or reference list at the end of your essay.

What Do You Think About Family

What is your side.