Childhood Obesity - Free Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

Childhood Obesity is a serious medical condition where excess body fat negatively affects a child’s health or well-being. Essays might discuss the causes, consequences, prevention and management of childhood obesity, as well as the role of parents, schools, and healthcare providers in addressing this issue. A vast selection of complimentary essay illustrations pertaining to Childhood Obesity you can find in Papersowl database. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

Problem: Childhood Obesity in America

As you've probably heard, more children are becoming overweight today in America than ever before. Experts are calling this an "obesity epidemic." To first understand childhood obesity we must ask ourselves what is obesity? Obesity is a diet-related chronic disease involving excessive body fat that increases the risk of health problems. Many doctors have expressed obesity has an increasing problem in today's youth as obesity can lead to many health issues such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart […]

Childhood Obesity Parents are the Blame

In current years, children becoming more obese in their entire childhood development has become common. Obesity in children could be due to various reasons such as family structure, busy family life experienced in the modern days, and insufficient knowledge of foods containing high calories. Parents ought to be accountable for what they do or fail to do that amounts to a negative influence on their children's weight and cause them to be overweight or obese during their childhood period. When […]

Childhood and Adolescents Obesity Prevention

Obesity in children and adolescents is a serious and growing problem in America. Overweight children are becoming overweight adults and that is causing life-threatening, chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. There are multiple reasons for childhood obesity. The most common reasons are genetic factors, lack of physical activity, unhealthy eating patterns, or a combination of all three factors (“Obesity in Children,” 2018). Today, there are many children that spend a lot of time being inactive and eating junk […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

Childhood Obesity – Causes and Potential Long-Term Effects

Abstract There is growing concern about the state of children’s health. Every year there is an increase in the number of overweight and obese children. What causes this and what does it mean for them long-term? There are many contributing factors to children’s weight issues. Some of these factors are limited access to healthy food, more time spent in front of a screen, and less physical activity. Long-term health affects include a rising risk of Type 2 diabetes, coronary heart […]

How are Fast Food Advertising and Childhood Obesity Related

By 1950s, fast food industry boom was in full swing. It was secured in 1951. In the 1950s, McDonald has become a staple of the American diet. Fast food restaurants have been grown more and more and by now, there are over one hundred and sixty thousands fast food restaurants in the United States, becoming a one hundred and ten billion dollar industry. One can’t deny that fast food has become really important in American life nowadays. Whether Americans are […]

Obesity in Childhood

There are numerous issues that society faces on a daily basis. One of the issues that society faces is obesity. It is one of the leading risks of death and has been ongoing since the 1960s and 1970s. Obesity is an issue that continues to grow not only in the United States but also in developing countries as well. Not only does obesity affect adults but it has become a serious issue for children. According to an article, "approximately 12.7 […]

Childhood Obesity a Serious Problem in the USA

Childhood obesity is a serious problem in the United States. Obesity is condition in which a child is significantly overweight for his or her age and height. It is a very common condition and is estimated to have around 3 million cases in the United States each year. Every day more children are getting diagnosed with obesity, and some as young as 4 years old. When a child gets diagnosed with obesity at a young age, it can be very […]

Childhood Obesity is an Epidemic in the USA

Introduction Childhood obesity has become an epidemic in the United States and other western industrialized societies. "Childhood obesity affects more than 18 percent of children in the United States, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood" (Obesity Action Coalition). According to the OAC, the percentage of children suffering from childhood obesity has tripled since 1980. A child is considered obese if their body mass index for their age is greater than 95 percent. Childhood obesity is both an […]

Obese Kids and Low Self-esteem

Those who are in poverty are predominately people of color and as you can see from the chart above there is a high percentage of children of color who were diagnosed with childhood obesity. According to Centers of Disease Control, "Overall, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic adults and youth had a higher prevalence of obesity compared with other race and Hispanic-origin groups. Obesity prevalence was lower among non-Hispanic Asian men and women compared with other race and Hispanic-origin groups. Among men, […]

Childhood Obesity Today

In America, childhood obesity is on a rise today. Children can gain obsessive weight because of environmental factors. Vending machines, low cost on snacks, and a increase in the fast food chain are contributing factors towards obesity. Genetics can also play a part in childhood obesity. Many children come from a generation of overweight families. Most parents don't see the harm in letting their children gain tons of weight. Obesity can cause many health problems. Childhood obesity affects the health […]

Childhood Obesity in the American Nation

Childhood obesity is still rising in this nation. One out of three Americans is obese. The outlook for children is not much better, as adolescent obesity has quadrupled over the last thirty years. "As of 2012, almost 18 percent of children aged 6-11 years were obese" (Newman, 1). Despite the considerable public awareness of the negative impacts of obesity, this challenge persists. The situation for youngsters is hardly brighter; over the last few decades, the rate of youth obesity has […]

Child and Adolescent Obesity in the United States

Child and adolescent obesity in the United States has nearly tripled sincethe 70s. About 1 out of every 5 children suffer from childhood obesity. It is the duty ofmothers and fathers to prevent and find solutions to child and adolescent obesity. Thispaper will seek to explain the many causes and current results which parents can execute.Child and adolescent obesity comprises of several likely causes such as poor diet and lowphysical activity including numerous adverse effects. Therefore, changes in familyhousehold structures […]

The Causes and Preventions of Childhood Obesity

When trying to find out if a child is considered for obesity, they need to have a body mass index that is between the ranges of the 85th percentile and the 95th percentile. When speaking about childhood obesity it is for children between the ages of infancy and early adulthood which is eighteen years of age. Obesity is one of the most preventable diseases especially if caught early enough. There are many different reasons for the cause of childhood obesity, […]

The Effects of the Epidemic Childhood Obesity

Childhood obesity has become a growing epidemic in more than just the U.S. However, over the past three decades, childhood obesity rates have tripled in the U.S. and today, the country has some of the highest obesity rates in the world: One out of six children is obese, and one out of three children is overweight. Chubby children were once thought of as cute, it was there baby fat and they would soon emerge into healthy adults, however this isn't […]

Tackling Childhood Obesity in Rural Mississippi

Childhood obesity is a growing health issue in the United States. Children with higher Body Mass Indexes than the recommended by the National Institutes of Health are more prone to adverse health effects later in life. Obesity in early age can translate into adulthood and increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (Franks 2010). The highest rates of childhood obesity can be observed in the southeastern corner of the United States, Mississippi, in particular, with the highest prevalence […]

Childhood Obesity, a Crisis that could be Cure

Obesity is a crisis that is affecting many countries, their most vulnerable citizens being children. Bad eating habits, high calorie intake, genetics, and lack of activity or exercise are some of the elements that, either combined or individually, are the cause for childhood obesity in America, Latin America, and many other nations. In the United States, rural areas have higher rates of childhood obesity, as do Hispanics and Blacks (Davis 2011). Keywords: Obesity, Childhood. Childhood Obesity, a Crisis that could […]

Childhood Obesity: Global Epidemic and Ethical Concerns

Abstract Numbers continue to climb for those who have childhood obesity. This serious issue has been brought to the attention of the public who have been taking preventative measures and action in hopes to reduce the number of cases. In a number of countries, public policies have been implemented to prevent obesity. However, in the U.S. efforts made are not enough or have not been effective to stop the obesity rate from increasing. Proposals for solutions to this health problem […]

Childhood Obesity and Unhealthy Diets

Over the years childhood obesity has become an epidemic. Working as a medical assistant in family practice for the past ten years, I have witnessed a lot of children struggling with being overweight and obese. Many children now in days lack whole foods that contain proper macronutrients for their bodies to use as energy adequately. Processed foods and sugary beverages can cause more complications over time when overconsumed. Along with lack of proper nutrition, a lot of children seem to […]

The Social Environment and Childhood Obesity

I, Marisol Nuñez, reside in South Gate the reason for this letter is that I am very concerned about the prevention of childhood obesity. Residents in our city lack the resources of acquiring healthy nutritious foods for their families, the resources in our city are very limited. The city has a farmer’s market once a week, and the likelihood of working families purchasing healthier foods is very limited. We need more resources for our families can eat highly nutritious foods. […]

Childhood Obesity and Physical Activity

Most children and teens have access to a tablet, smartphone, television, laptop or a video console. They are sitting around on-screen time more and more as the days go by. Research from the CDC states obesity has nearly doubled since the 1970s in the United States. It is estimated now that 20 percent of children and adolescents are affected by obesity. Too much screen time, the accessibility to the internet and not enough physical activity are the biggest reasons the […]

Childhood Obesity and Adolesence

Childhood obesity can be prevented in many ways. Parents are the main ones with a say so on obesity. They allow their children to digest all kinds of bad foods. Parents should introduce on a daily basis different kinds of healthy foods. They should also promote is by showing children how healthy food are good for the body. You have some children that won’t eat healthy things because of the color and the way it looks. Obesity is one of […]

Several Factors in Childhood Obesity

Childhood obesity is widely described as excess in body fat in children and teenagers. There is, however, no agreement about exactly how much body fat is excessive in relation to the group. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention on its part defined overweight as at or above the 95th percentile of body mass index (BMI) for age and "at risk for overweight" as between 85th to 95th percentile of BMI for age (Krushnapriya Sahoo). In general clinic environments, the […]

Factors that Influence Childhood Obesity

The cause of pediatric obesity is multifactorial (1). There is not a single cause, nor solution, found that leads to all cases of pediatric obesity. Parental discipline in regard to the child is not proven to lead to less adiposity or obesity in children. Parental feeding strategy may actually be a cause of obesity with restrictive approach to food by the parent shown to increase the proclivity for the restricted foods (2). Likewise, when parents allowed their children to have […]

Childhood Obesity, Disease Control and Prevention

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, identifying effective intervention strategies that can target both improvements in physical activity and providing a nutritious diet to reduce childhood obesity are important" (Karnik, 21). There has been a rising concern on whether or not the government needs to be involved in this childhood obesity epidemic. Sameera, Karnik, and Amar Kanekar give an amazing detailed article on how important it is to get involved with children through the government and through […]

The Impact of Childhood Obesity on Health

Childhood Obesity has become an ongoing problem across the United States. Obesity kills about 34 children every hour in the world, making it a serious issue. Many leaders and people have come together to attempt to prevent the issue, but some strategies have failed. Most people disregard the fact that what they feed their children can affect them in many ways, specifically become obese. Childhood obesity can lead to becoming obese in the future, being susceptible to different diseases and […]

What is Childhood Obesity?

Introduction Childhood obesity has become a widespread epidemic, especially in the United States. Twenty five percent of children in the United States are overweight and eleven percent are obese (Dehghan, et al, 2005). On top of that, about seventy percent of those children will grow up to be obese adults (Dehgan, et al, 2005). There are many different causes that can be attributed to the childhood obesity. Environmental factors, lifestyle preferences, and cultural environment play pivotal roles in the rising […]

Problem of Childhood Obesity in the United States

Among the many issues that the United States is facing, there is no doubt that Childhood Obesity is a timely and relevant debatable topic that has brought many consequences and health issues among our nation’s children. Many debates in regard to childhood obesity have formed. Because the prevalence of childhood obesity is on the rise, there have been varying opinions about what leading factors contribute to this issue. Although some health professionals and parents believe that childhood obesity stems from […]

A Big Problem – Bad Healthcare is Aiding Childhood Obesity

A study done in 2002 found that, almost 14 million children are obese, that is 24 percent of the U.S. population from ages 2 to 17. This number just keeps rising as the years go by. Some people would argue that the increasing numbers are due to sugary dinks and foods sold in vending machines at schools, or not enough healthy food options. Other parties can argue that this number keeps increasing because of bad healthcare and not enough opportunities […]

Childhood Obesity Rate Can be Decreased

Child obesity has become a major concern as it continues to increase every year in the US. Many parents are uneducated about the risks of childhood obesity. Parental awareness and increasing physical activity are steps towards making a change in the rates of childhood obesity. There are many side effects of childhood obesity that can obstruct a child’s future. However, positive changes to children’s health can be achieved through the influence of adults. Child obesity has become a more critical […]

Additional Example Essays

- The Mental Health Stigma

- Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner

- Substance Abuse and Mental Illnesses

- Homeschooling vs Public School

- Socioautobiography Choices and Experiences Growing up

- A Research Paper on Alzheimer's Disease

- The Effect of Alcohol on College Students

- Is Sexual Orientation Determined At Birth?

- Nursing Shortage: solutions of the problem

- End Of Life Ethical Issues

- Beauty Pageants for Children Should Be Banned: Protecting Child Well-being

- Live Free and Starve, by Chitra Divakaruni

How To Write an Essay About Childhood Obesity

Understanding childhood obesity.

Writing an essay about childhood obesity requires a comprehensive understanding of the topic. Childhood obesity is a serious public health issue that has grown significantly in recent years. It's characterized by children having a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile for children of the same age and sex. Start by exploring the causes of childhood obesity, which can include genetic factors, poor dietary habits, lack of physical activity, and environmental influences. Also, consider the short and long-term health implications, such as an increased risk of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for a deeper analysis in your essay.

Developing a Focused Thesis Statement

Your essay should be guided by a clear, focused thesis statement. This statement should present a specific angle or argument about childhood obesity. For instance, you might argue the importance of early intervention programs, the role of schools in promoting healthy lifestyles, or the impact of advertising and media on children’s eating habits. Your thesis will determine the direction of your essay, guiding your analysis and ensuring a structured approach to the topic.

Gathering and Analyzing Data

An effective essay on childhood obesity should be supported by relevant data and research. This includes statistics on the prevalence of obesity, studies on its causes and effects, and evaluations of intervention programs. Use this information to support your thesis, incorporating both national and global perspectives. Analyze the data critically, acknowledging any limitations and considering different viewpoints. This approach adds depth to your essay and strengthens your arguments.

Discussing Solutions and Interventions

A significant portion of your essay should be dedicated to discussing potential solutions and interventions for childhood obesity. This can include public health policies, educational programs, changes in food industry practices, or community-based initiatives. Evaluate the effectiveness of these solutions, drawing on case studies or research findings. Discussing both the successes and challenges in tackling childhood obesity will provide a balanced view and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Concluding the Essay

Conclude your essay by summarizing the main points of your discussion and restating your thesis in light of the evidence presented. Your conclusion should tie together your analysis and emphasize the significance of addressing childhood obesity. This is also an opportunity to reflect on potential future developments in the field or to suggest areas for further research.

Reviewing and Refining the Essay

After completing your essay, it's important to review and refine it. Check for coherence in your arguments and clarity in your writing. Ensure that your essay is well-organized and free from grammatical errors. Consider seeking feedback from peers, teachers, or health professionals to further improve your work. A well-crafted essay on childhood obesity should not only inform but also engage readers in considering the complexities of this public health issue and the collective efforts required to address it.

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Childhood Obesity — Child Obesity Essay Outline

Child Obesity Essay Outline

- Categories: Childhood Obesity

About this sample

Words: 681 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 681 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1163 words

5 pages / 2053 words

5 pages / 2799 words

13 pages / 5869 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Childhood Obesity

Buzzell, L. (2019, August 13). Benefits of a Healthy Lifestyle. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-eating-on-a-budget#1.-Plan-meals-and-shop-for-groceries-in-advance

Obesity in children in the US and Canada is on the rise, and never ending because new parents or parents with experience, either way tend to ignore what is happening with their child. A study at UCSF tells us that “A child with [...]

In conclusion, while Zinczenko's analysis in "Don't Blame the Eater" offers valuable insights into the rise of childhood obesity and the role of the fast-food industry, it is necessary to critically examine his claims. While [...]

With obesity rates on the rise, and student MVPA time at an all time low, it is important, now more than ever, to provide students with tools and creative opportunities for a healthy and active lifestyle. A school following a [...]

In today's fast-paced world, where stress levels are high and unhealthy habits run rampant, the importance of good health cannot be overstated. From physical well-being to mental resilience, good health impacts every aspect of [...]

It is well known today that the obesity epidemic is claiming more and more victims each day. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention writes “that nearly 1 in 5 school age children and young people (6 to 19 years) in the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Leave Fat Kids Alone

The “war on childhood obesity” has only caused shame.

By Aubrey Gordon

Ms. Gordon is the author of the forthcoming book “What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat.”

I was in the fourth grade, sitting in a doctor’s office, the first time my face flushed with shame. I was, I had just learned, overweight.

I will remember the pediatrician’s words forever: It’s probably from eating all that pizza and ice cream. It tastes good, doesn’t it? But it makes your body big and fat.

I felt my face sear with shame.

There was more: Just imagine that your body is made out of clay. If you can just stay the same weight, as you grow, you’ll stretch out. And once you grow up, you’ll be thin and beautiful. Won’t that be great?

I learned so much in that one moment: You’re not beautiful. You’re indulging too much. Your body is wrong. You must have done it. I’d failed a test I didn’t even know I’d taken, and the sense of failure and self-loathing it inspired planted the seeds of a depression I would live with for many years.

As the holiday season approaches, with its celebratory family meals and seasonal treats, I worry about the children across the country who will endure similar remarks, the kind that shatter their confidence, reject their bodies and usher them into a harsh new world of judgment.

For the rest of my childhood, I weathered the storm of conversations like the one I had at the doctor’s office. Well-meaning, supportive adults eagerly pointed out my perceived failings at every turn. As the years went on, more and more foods, I was told, were off limits.

It wasn’t just that I shouldn’t eat them; it was that they were sinful, bad, tempting . Many of those foods — eggs, nuts, avocados — would later fall back into the good graces of healthy eating. At the time, though, they were collateral damage in a crusade to cut calories at all costs. Fiber, vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, protein — they were all sacrificed at the altar of calories in, calories out. The focus was never on enjoying nutritious foods, just on deprivation, will and lack.

My life was filled with self-flagellation, forced performances to display my commitment to changing an unacceptable body. Adults asked openly about what I had eaten, when I had exercised and whether I knew how to do either correctly. After all, if I was still fat, it must be my fault.

My body wasn’t just a body, the way a thinner one might have been. It was perceived as a burden, an inconvenience, a bothersome problem to solve. Only thinness would allow me to forget my body, but despite my best efforts, thinness never came.

The more I and others tried to change my size, the deeper my depression became. Even at such a young age, I had been declared an enemy combatant in the nation’s war on childhood obesity, and I felt that fact deeply. Bodies like mine now represented an epidemic, and we were its virus, personified.

The war on obesity seemed to emerge, fully formed, near the turn of the millennium, but its roots run deeper than that. C. Everett Koop, surgeon general under President Ronald Reagan, made fatness a priority for his office in the 1980s. In 2004, nearly three years after the Sept. 11 attacks, Surgeon General Richard Carmona compared the war on obesity to the war on terror. Suddenly, fat people weren’t just neighbors, friends or family members — we were enemies to be feared.

The war on childhood obesity reached its zenith with the 2010 introduction of the national “Let’s Move!” campaign, “dedicated to solving the problem of obesity within a generation.” It was a campaign against “childhood obesity” — not specific health conditions or the behaviors that may contribute to those health conditions. It wasn’t a campaign against foods with little nutritional value, or against the unchecked poverty that called for such low-cost, shelf-stable foods. It was a campaign against a body type — specifically, children’s body types.

In 2012, Georgia began its Strong4Life campaign aimed at reducing children’s weight and lowering the state’s national ranking: second in childhood obesity. Run by the pediatric hospital Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, it was inspired in part by a previous anti-meth campaign. Now, instead of targeting addiction in adults, the billboards targeted fatness in children. Somber black-and-white photographs of fat children stared at viewers, emblazoned with bold text. “WARNING: My fat may be funny to you but it’s killing me. Stop childhood obesity.” “WARNING: Fat prevention begins at home. And the buffet line.” “WARNING: Big bones didn’t make me this way. Big meals did.”

The billboards purported to warn parents of the danger of childhood fatness, but to many they appeared to be public ridicule of fat kids. Strong4Life became one of the nation’s highest-profile fat-shaming campaigns — and its targets were children.

These declarations of an obesity epidemic and a war on childhood obesity all doggedly pursued one question, and one question only: How do we make fat kids thin? In other words, how do we get rid of fat kids?

Overwhelmingly, childhood anti-obesity programs hinged on shame and fear, a scared-straight approach for fat children. As of 2017, fully half of the states required that schools track students’ body mass index. Many require “B.M.I. report cards” to be sent home to parents, despite the fact that 53 percent of parents don’t actually believe that the reports accurately categorize their child’s weight status. And observational studies in Arkansas and California have shown that the practice of parental notification doesn’t appear to lead to individual weight loss or an overall reduction in students’ B.M.I.s. One eating disorder treatment center called the report cards a “pathway to weight stigma” that would most likely contribute to the development of eating disorders in predisposed students.

Experiencing weight stigma has significant long-term effects, too. A 2012 study in the journal Obesity asked fat adults to indicate how often they had experienced various weight-stigmatizing events. Seventy-four percent of women and 70 percent of men of similar B.M.I. and age reported others’ making negative assumptions. Twenty-eight percent of women and 23 percent of men reported job discrimination. The effects of stigma were especially dire for young people, very fat people and those who started dieting early in life. To cope, 79 percent of all respondents reported eating, 74 percent isolated themselves, and 41 percent left the situation or avoided it in the future. Rather than motivating fat people to lose weight, weight stigma had led to more isolation, more avoidance and less support.

Despite ample federal and state funding, multiple national public health campaigns and a slew of television shows, the war on obesity does not appear to be lowering Americans’ B.M.I.s. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, since 1999 there has been a 39 percent increase in adult obesity and a 33.1 percent increase in obesity among children.

Weight stigma kick-starts what for many will become lifelong cycles of shame. And it sends a clear, heartbreaking message to fat children: The world would be a better place without you in it.

Yet, despite its demonstrated ineffectiveness, the so-called war on childhood obesity rages on. This holiday season, for the sake of children who are told You’re not beautiful. You’re indulging too much. Your body is wrong. You must have done it, I hope some parents will declare a cease-fire.

Aubrey Gordon, who has written under the pseudonym “Your Fat Friend,” is a columnist for Self magazine, a co-host of the podcast “Maintenance Phase” and the author of the forthcoming book “ What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat .”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

- IELTS Scores

- Life Skills Test

- Find a Test Centre

- Alternatives to IELTS

- General Training

- Academic Word List

- Topic Vocabulary

- Collocation

- Phrasal Verbs

- Writing eBooks

- Reading eBook

- All eBooks & Courses

IELTS Sample Task 2 Essay: Child Obesity

by Patel (Bolton)

“There is no doubt that overweight children’s percentages rose by twenty percent in western world.”

“overweight children’s percentages rose”

“Secondly, some advertisements that encourage children to eat unhealthy diet.”

Overweight children are prone to many problems.

Such as + noun For example + Subject Verb

to be concerned about

Click here to add your own comments

Return to Writing Submissions - Task 2.

Before you go...

Check out the ielts buddy band 7+ ebooks & courses.

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

Band 7+ eBooks

"I think these eBooks are FANTASTIC!!! I know that's not academic language, but it's the truth!"

Linda, from Italy, Scored Band 7.5

IELTS Modules:

Other resources:.

- All Lessons

- Band Score Calculator

- Writing Feedback

- Speaking Feedback

- Teacher Resources

- Free Downloads

- Recent Essay Exam Questions

- Books for IELTS Prep

- Useful Links

Recent Articles

Key Phrases for IELTS Speaking: Fluency and Coherence

May 26, 24 06:52 AM

Useful Language for IELTS Graphs

May 16, 24 04:44 AM

Taking a Gap Year

May 14, 24 03:00 PM

Important pages

IELTS Writing IELTS Speaking IELTS Listening IELTS Reading All Lessons Vocabulary Academic Task 1 Academic Task 2 Practice Tests

Connect with us

Copyright © 2022- IELTSbuddy All Rights Reserved

IELTS is a registered trademark of University of Cambridge, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia. This site and its owners are not affiliated, approved or endorsed by the University of Cambridge ESOL, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management

Hiba jebeile.

a Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

b Institute of Endocrinology and Diabetes, The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW, Australia

Aaron S Kelly

d Department of Pediatrics and Center for Pediatric Obesity Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Grace O'Malley

e School of Physiotherapy, RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin, Ireland

f Child and Adolescent Obesity Service, Children's Health Ireland at Temple Street, Dublin, Ireland

Louise A Baur

c Weight Management Services, The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, NSW, Australia

This Review describes current knowledge on the epidemiology and causes of child and adolescent obesity, considerations for assessment, and current management approaches. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, obesity prevalence in children and adolescents had plateaued in many high-income countries despite levels of severe obesity having increased. However, in low-income and middle-income countries, obesity prevalence had risen. During the pandemic, weight gain among children and adolescents has increased in several jurisdictions. Obesity is associated with cardiometabolic and psychosocial comorbidity as well as premature adult mortality. The development and perpetuation of obesity is largely explained by a bio-socioecological framework, whereby biological predisposition, socioeconomic, and environmental factors interact together to promote deposition and proliferation of adipose tissue. First-line treatment approaches include family-based behavioural obesity interventions addressing diet, physical activity, sedentary behaviours, and sleep quality, underpinned by behaviour change strategies. Evidence for intensive dietary approaches, pharmacotherapy, and metabolic and bariatric surgery as supplemental therapies are emerging; however, access to these therapies is scarce in most jurisdictions. Research is still needed to inform the personalisation of treatment approaches of obesity in children and adolescents and their translation to clinical practice.

Introduction

Obesity in children and adolescents is a global health issue with increasing prevalence in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) as well as a high prevalence in many high-income countries. 1 Obesity during childhood is likely to continue into adulthood and is associated with cardiometabolic and psychosocial comorbidity as well as premature mortality. 2 , 3 , 4 The provision of effective and compassionate care, tailored to the child and family, is vital. In this Review, we describe current knowledge on the epidemiology and causes of child and adolescent obesity, considerations for assessment, and current management approaches.

Epidemiology

Definitions of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents.

WHO defines overweight and obesity as an abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health. For epidemiological purposes and routine clinical practice, simple anthropometric measures are generally used as screening tools. BMI (weight/height 2 ; kg/m 2 ) is used as an indirect measure of body fatness in children and adolescents 5 and should be compared with population growth references adjusted for sex and age. The WHO 2006 Growth Standard is recommended in many countries for children aged 0–5 years, and for children aged 0–2 years in the USA. 6 For older children and adolescents, other growth references are used, including the WHO 2007 Growth Reference, recommended for those aged 5–19 years (overweight defined as BMI ≥1SD and obesity as BMI ≥2SD of the median for age and sex), and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Growth Reference for those aged 2 to 20 years (overweight is >85th to <95th percentile and obesity is ≥95th percentile based on CDC growth charts). 6 , 7 The International Obesity Task Force tables for children aged 2 to 18 years are used for epidemiological studies. 8

Abdominal or central obesity is associated with increased cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents. 9 For waist circumference there are regional and international growth references allowing adjustment for age and sex. 10 , 11 , 12 A waist-to-height ratio of more than 0·5 is increasingly used as an indicator of abdominal adiposity in clinical and research studies, with no need for a comparison reference. 13

Various definitions have been suggested to identify more extreme values of BMI in children and adolescents. The International Obesity Task Force defined morbid obesity as equivalent to age-adjusted and sex-adjusted BMI of 35kg/m 2 or more at age 18 years, a definition specifically for epidemiological use. 14 The American Heart Association characterises severe obesity as a BMI of 120% or more of the 95th percentile of BMI for age and sex (based on CDC2000 growth charts), a definition that can be used in both clinical practice and research. 15 There are marked limitations in transforming very high BMI values to z-scores, particularly when using CDC2000 growth charts because reductions in BMI can be underestimated. 15

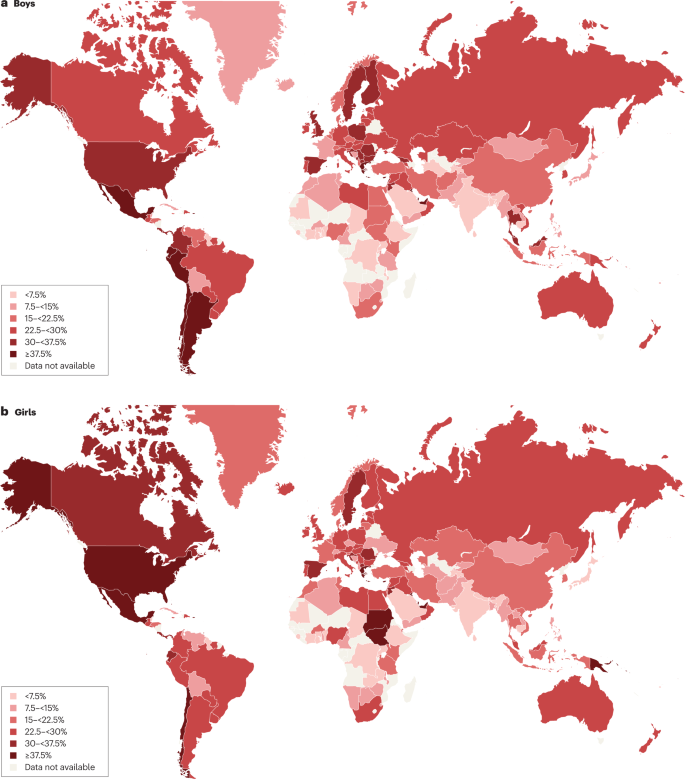

The prevalence of paediatric obesity 16 has increased worldwide over the past five decades. From 1975 to 2016, the global age-standardised prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents aged 5–19 years increased from 0·7% (95% credible interval [CrI] 0·4–1·2) to 5·6% (4·8–6·5) for girls and from 0·9% (0·5–1·3) to 7·8% (6·7–9·1) for boys. 17 Since 2000, the mean BMI has plateaued, usually at high levels, in many high-income countries but has continued to rise in LMICs. In 2016, obesity prevalence in this age group was highest (>30%) in many Pacific Island nations and was high (>20%) in several countries in the Middle East, north Africa, Micronesia (region of the western Pacific), Polynesia (subregion of Oceania), the Caribbean, as well as in the USA. 17

In 2019, the World Obesity Federation estimated there would be 206 million children and adolescents aged 5–19 years living with obesity in 2025, and 254 million in 2030. 1 Of the 42 countries each estimated to have more than 1 million children with obesity in 2030, the top ranked are China, followed by India, the USA, Indonesia, and Brazil, with only seven of the top 42 countries being high-income countries.

The prevalence of severe obesity in the paediatric population has grown in many high-income countries, even though overall prevalence of obesity has been stable. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 In a survey of European countries, approximately a quarter of children with obesity were classified with severe obesity, a finding that has implications for delivery of obesity clinical services, because such children will need more specialised and intensive therapy. 19

There are socioeconomic disparities in paediatric obesity prevalence within countries. In lower-income to middle-income countries, children of higher socioeconomic status are at greater risk of being affected by overweight or obesity than children of a lower socioeconomic status, whereas in high-income countries, it is children living in socioeconomic disadvantage who are at higher risk. 22 , 23 , 24

Reports from China, Europe, and the USA have documented increased weight gain among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the rate before the pandemic, 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 an apparent consequence of decreases in physical activity, increased screen time, changes in dietary intake, food insecurity, and increased family and individual stress. 30

Development and perpetuation of obesity: a bio-socioecological framework

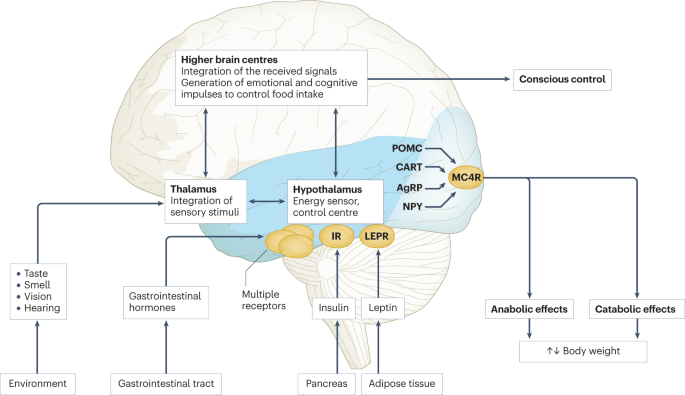

The development and perpetuation of obesity in modern society can largely be explained by a bio-socioecological framework that has created the conditions for a scenario in which biological predisposition, socioeconomic forces, and environmental factors together promote deposition and proliferation of adipose tissue and resistance to efforts of obesity management. A high degree of biological heterogeneity exists in bodyweight regulation and energy dynamics such that some individuals can maintain healthy levels of adipose tissue with little effort while others face a lifelong struggle with regulating levels. Further, adipose tissue is heterogeneous such that white, brown, and beige forms exist with a variety of physiological functions. 31 The anatomical sites where adipose tissue is stored can translate into varying health risks (eg, central accumulation of adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic disease compared to peripheral stores). 32 At a fundamental level, the relative function of the energy regulatory system (the complex interplay of central and peripheral pathways driving appetite, satiety, pleasure-seeking behaviours, and metabolic efficiency) strongly influences body composition. More specifically, the bodyweight set point theory posits the existence of a tightly regulated and complex biological control system, which drives a dynamic feedback loop aimed at defending a predetermined relative or absolute amount of adiposity. 33 Support for this theory comes from evidence in adults demonstrating immediate and sustained alterations in levels of hormones driving appetite and satiety, perceptions of food palatability, and resting energy expenditure following attempts at weight loss. 34 , 35 Other biobehavioural factors such as poor sleep quality, adversity, stress, and medications (causing iatrogenic weight gain) can also serve to exacerbate dysfunction of the energy regulatory system favouring weight gain.

Environmental and behavioural associations of obesity

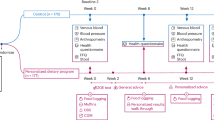

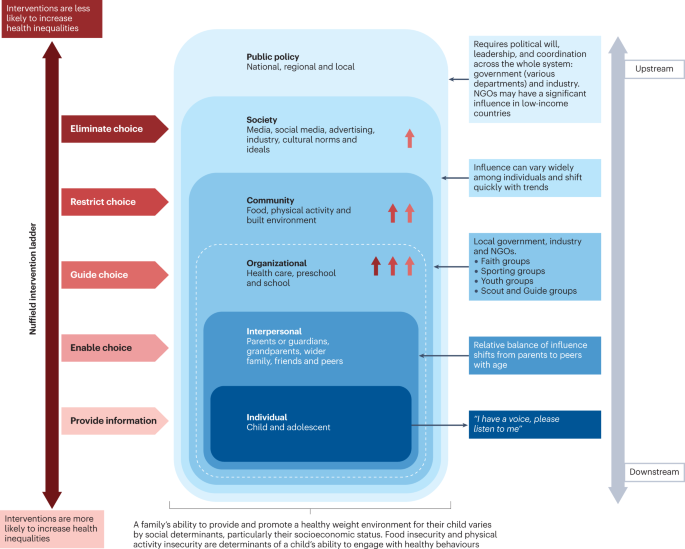

Over the past few decades the rise in obesity prevalence has been profoundly influenced by changes in the broader obesogenic environment. 36 These changes operate at the level of the family (eg, family modelling of physical activity, food habits, sleep, screen use), local community (eg, child care and schools, parks, green space, public transport and food outlets), or the broader sociopolitical environment (eg, government policies, food industry, food marketing, transport systems, agricultural policies and subsidies). Such influences have been described as having the ability to exploit people's biological, psychological, social, and economic vulnerabilities. 37 Figure 1 depicts a socioecological model incorporating some of the personal and environmental factors influencing paediatric obesity. 38

A socioecological model for understanding the dynamic interrelationships between various personal and environmental factors influencing child and adolescent obesity.

Adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention social-ecological model framework for prevention. 38 *Defined as being traversable on foot, compact, physically enticing, and safe.

Dietary factors contributing to obesity risk in children and adolescents include excessive consumption of energy-dense, micronutrient-poor foods; a high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages; and the ubiquitous marketing of these and fast foods. 39 , 40 The relative effect of other factors such as specific eating patterns (eg, frequent snacking, skipping breakfast, not eating together as a family, the window of time from first to last daily meal), portion sizes, the speed of eating, macronutrient intake, and glycaemic load on obesity development remain unclear, although all might be important. 41 , 42

The link between screen time and obesity in childhood and adolescence was initially documented through cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of television viewing. 43 , 44 The past two decades have seen the increase of mobile and gaming devices. Screen exposure influences risk of obesity in children and adolescents via increased exposure to food marketing, increased mindless eating while watching screens, displacement of time spent in more physical activities, reinforcement of sedentary behaviours, and reduced sleep time. 44 , 45

Children's physical activity levels decline around the age of 6 years and again at age 13 years, with girls usually exhibiting more marked declines than boys. Overall, children with obesity tend to engage in lower levels of moderate-vigorous activity than leaner peers. 46 , 47 , 48 Sedentary time increases from the age of 6 years in general, although accelerometery studies report no differences between children with obesity compared with leaner peers. 48 Lower levels of physical activity and increasing sedentary behaviours throughout childhood in all children contribute to obesity development. 49 In most countries, children and adolescents are not sufficiently active due to the loss of public recreation space, the increase in motorised transport and decrease in active transport (eg, cycling, walking, public transport), perceptions of lack of safety in local neighbourhoods leading to less active behaviour, as well as an increase in passive entertainment. 39 , 49

There is growing evidence that short sleep duration, poor sleep quality and a late bedtime are associated with a higher obesity risk, sedentary behaviours, poor dietary patterns, and insulin resistance. In addition, there is a possible link with increased screen time, decreased physical activity, and changes in ghrelin and leptin levels. 50 Many of these obesity-conducive behaviours co-occur. For example, increased screen time is associated with delayed sleep onset and shortened sleep duration, and insufficient sleep is associated with increased food intake and lower levels of physical activity. 50

Early life factors

Several factors in early life put children at increased risk of developing obesity. These factors include maternal obesity before pregnancy, excessive gestational weight gain, and gestational diabetes, all associated with increased birth weight. 51 , 52 Infant and young child feeding practices have variable influences on childhood obesity. Meta-analyses from systematic reviews suggest that breastfeeding has a modest but protective effect against later child obesity. 53 , 54 There is some evidence suggesting that the very early introduction of complementary foods and beverages, before the age of 4 months, especially in formula-fed babies, is associated with higher odds of overweight and obesity. 55 Parental approaches to feeding, especially in the preschool age group (aged 1–4 years), might influence obesity risk, with a systematic review showing a small but significant association between controlling child feed practices (eg, restriction of specific foods or the overall amount of food) and higher child weight. 56 Studies of the role of responsive feeding, whereby the caregiver attends to the baby's cues of hunger and satiety, show that non-responsive feeding is associated with increased child BMI or overweight or obesity. 57 , 58 By contrast, a responsive feeding style that recognises the child's cues of hunger and satiety appears to support healthy weight gain trajectories. 58 , 59 However, in all such studies of infant and young child feeding, the effect of residual confounding on child weight status cannot be discounted.

Other environmental exposures in early life that influence child obesity risk include maternal smoking during pregnancy, 60 second-hand exposure to smoke, and air pollution. 61 Antibiotic exposure in infancy is associated with a slight increase in childhood overweight and obesity, especially if there are repeated treatments, an association that might be mediated by alterations in the gut microbiome. 62 Importantly, there is increased recognition that adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse, family dysfunction and neglect are associated with the development of childhood obesity. This association appears to be especially the case for sexual abuse and for co-occurrence of multiple adverse experiences. 63

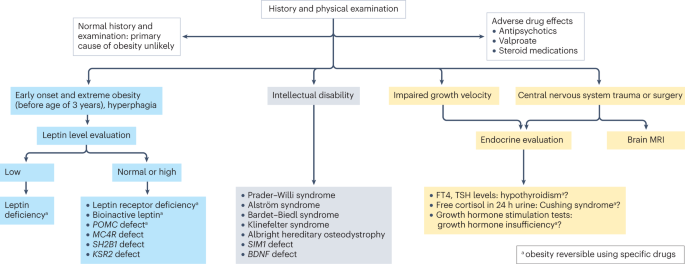

Medical conditions associated with obesity

Obesity might occur secondary to a range of medical conditions including several endocrine disorders (eg, hypothyroidism, hypercortisolism, growth hormone deficiency), central nervous system damage (ie, hypothalamic-pituitary damage because of surgery or trauma) and post-malignancy (eg, acute leukaemia). Several pharmacological agents are associated with excess weight gain, including glucocorticoids, some anti-epileptics (eg, sodium valproate), insulin, and several atypical antipsychotics (eg, risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine). 64 The rapid and large weight gain associated with the latter class of drugs suggests that anticipatory weight management strategies should be formally used when commencing such therapy, although evidence is largely from adult studies. 65

Weight stigma

Weight stigma refers to the societal devaluation of a person because they have overweight or obesity, and includes negative stereotypes that individuals are lazy and lack motivation and willpower to improve health. 66 , 67 Higher body mass is associated with a greater degree of weight stigma, although longitudinal studies have shown associations between weight stigma and BMI to be bidirectional. 68 Stereotypes manifest in different ways, leading to discrimination and social rejection, often expressed as teasing, bullying and weight-based victimisation in children and adolescents. 66 , 67 Bodyweight is consistently reported to be the most frequent reason for teasing and bullying in children and adolescents, with a quarter to half of youth reporting being bullied based on their bodyweight. 69 Parents and health-care providers can also be sources of weight stigma. 69 , 70 Weight stigma is associated with poor mental health, impaired social development and education, and engagement in disordered eating behaviours including binge eating. 69 Of concern, youth who have experienced weight related teasing or bullying have higher rates of self-harm behaviours and suicidality compared with peers of the same weight who have not felt stigmatised. 67

Experience of weight stigma is a barrier to accessing health care. 67 Health professionals have a responsibility to help reduce weight stigma experienced by children, adolescents, and families through the use of supportive, compassionate, and non-stigmatising language while providing care. 69 In 2020, an international consensus statement was endorsed by more than 100 organisations pledging to reduce weight stigma. 66 Additionally, the American Academy of Paediatrics recommends paediatricians help mitigate weight stigma within clinical practice by role-modelling professional behaviours, using non-stigmatising language, using patient-centred behaviour change counselling, creating a safe and welcoming clinical environment accommodating of all body sizes, and conducting behavioural health screening for signs of weight-based bullying including emotional comorbidities. 67

Health complications

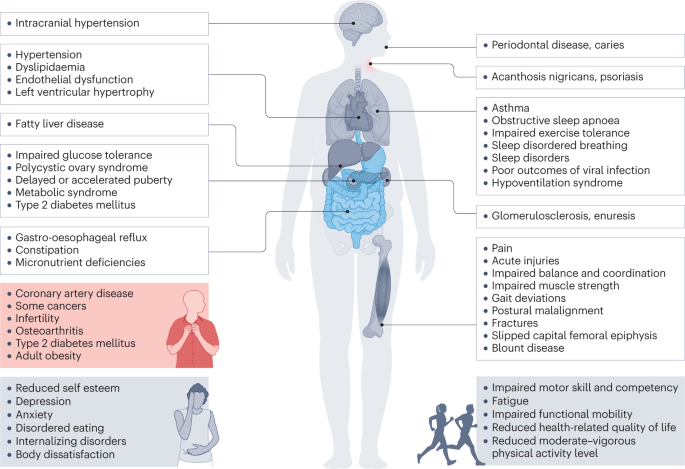

All body systems can be affected by obesity in the short, medium, or longer term, depending upon age and obesity severity. Figure 2 depicts the possible complications of obesity that can occur anywhere from childhood and adolescence to adulthood. It is important that complications are assessed in childhood and treated alongside obesity to prevent progression of both. Recent reviews provide additional detail regarding complications. 2 , 3 , 4 , 48 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 91 , 92 , 94 , 95

Short-term and long-term health complications and comorbidities associated with child and adolescent obesity

Health complications and comorbidities include neurological, 71 dental, 72 cardiovascular, 2 , 73 , 74 , 75 psychosocial, 2 , 4 , 76 , 77 , 78 respiratory, 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 endocrine, 73 , 84 , 85 musculoskeletal, 80 , 86 , 87 , 88 renal, 89 , 90 gastrointestinal, 90 , 91 skin, 92 function, and participation. 48 , 93

Clinical assessment

A detailed clinical examination screens for underlying causes of obesity, and assesses for possible obesity-related complications, risk of future disease, and whether potentially modifiable behavioural factors exist. Adapted from various national or regional level clinical practice guidelines, 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 summaries of the main aspects to be explored in history taking and physical examination are included in the panel and table . Laboratory tests can complement clinical assessment, looking for cardio-metabolic complications and some underlying causes of obesity. These tests are appropriate in most adolescents with obesity, and in all patients with severe obesity, with clinical signs or history suggestive of complications (eg, acanthosis nigricans), or with a family history of cardio-metabolic disease. Investigations would generally include liver function tests, lipid profile, fasting glucose, and glycated haemoglobin, and might include an oral glucose tolerance test and additional endocrine or genetic studies. 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102

Elements of history taking

General history

- • Prenatal and birth history, including gestational obesity, gestational diabetes, maternal smoking, gestational age, birth weight, and neonatal concerns

- • General medical history, including psychiatric or behavioural diagnoses and previous malignancy

- • Developmental history, including any delays in motor, speech, or cognitive developmental, and therapy received

- • Infant feeding, including breastfeeding and duration and timing of introduction of complementary foods

- • Current medications, including glucocorticoids, anti-epileptics (eg, sodium valproate), and antipsychotics (eg, clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine)

Growth history

- • Height and weight growth trajectories

- • Onset of obesity and timing of weight concerns of child or adolescent and family

- • Previous obesity management, whether supervised or self-initiated

- • Previous and current dieting and exercise behaviours or use of supplements

Complications history

- • Psychological impacts of obesity, including bullying, poor self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and disordered eating

- • Sleep routines, presence of snoring or possible sleep apnoea (eg, poor refreshment after sleep, daytime somnolence, and witnessed apnoea)

- • Exercise tolerance, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, dyspnoea, hypertension, and fatigue levels

- • Specific symptoms including acne and hirsutism (girls), morning headache and visual disturbance, nocturnal enuresis, daytime dribbling, constipation, hip and knee joint pain, and gastrointestinal complaints (vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and gastrointestinal reflux)

- • Menstrual history (girls)

Family history

- • Ethnicity (high risk groups for cardiometabolic complications include First Nations peoples, Latin American, south Asian, east Asian, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern)

- • Family members with a history of obesity; type 2 diabetes and gestational diabetes; hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and cardiovascular disease; obstructive sleep apnoea; polycystic ovary disease; bariatric surgery; eating disorders; and mental health disorders

- • Home environment including household members, parental relationship, parental employment, hours, and home supervision

Social history, including welfare, and safety

- • Housing or accommodation situation (stable or homeless) and residential care

- • Family income (or proxy) and food insecurity

- • Previous social services involvement

- • School attendance, additional educational assistance, learning difficulties, and behavioural difficulties

- • Hobbies and interests

- • Friends in school or neighbourhood

- • Use of tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drugs

- • Parenting style and child–parent interactions

Behavioural risk factors

- • Nutrition and eating behaviours: breakfast consumption; eating patterns including snacking, grazing, sneaking or hiding food, fast-food intake, binge-eating; beverage consumption (sodas, juices, other sugary drinks); family routines around food and eating; and active dieting

- • Physical activity: transport to and from school; participation in physical education class; participation in organised sport, dance, or martial arts; gym membership; after-school and weekend recreation; and family activities

- • Sedentary behaviours: time spent sitting each day; screen-time per day (television, video game, mobile phone, tablet, computer use); number of devices in the household and bedrooms; patterns of screen viewing (eg, during meals, at night); and use of social media

- • Sleep behaviours: bedtime routines; sleep and wake times on weekdays and weekends; and daytime napping

Clinical findings on examination by organ system

Obesity treatment in children and adolescents aims to reduce adiposity, improve related physical and psychosocial complications, and prevent the development of chronic diseases. The degree of BMI reduction needed to improve obesity related complications is currently unknown. However, some evidence suggests that BMI z-score reductions greater than 0·25 and 0·5 might represent clinically important thresholds. 104 Several high-quality clinical practice guidelines are in use internationally. 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 Treatment type and intensity depends upon obesity severity, the age and developmental stage of the child, needs and preferences of the patient and family, clinical competency and training of the clinician(s), and the health-care system in which treatment is offered. 105 Treatment integrates multiple components including nutrition, exercise and psychological therapy, pharmacotherapy, and surgical procedures. It should be delivered by suitably qualified paediatric health professionals who incorporate behavioural support and non-stigmatising child-focused and youth-focused communication into their practice. 69

Multicomponent behavioural interventions

Behavioural support strategies in obesity management include a combination of addressing dietary intake, physical activity, sedentary behaviours, sleep hygiene, and behavioural components within the context of a family-based and developmentally appropriate approach aiming for long-term behaviour modification. 106 , 107 , 108 Tailoring of interventions to various subgroups based on age, gender, and culture might be needed. For example, with young children the therapy might be largely parent-focussed 109 and for adolescents a greater degree of autonomy might be required. 107

Dietary intervention

Dietary interventions might include dietary education alone or combined with a moderate energy restriction, 110 with structured dietary plans or advice preferred over broad dietary principles, particularly for adolescents. 111 Principles of dietary education focus on adoption of dietary intake patterns consistent with local dietary guidelines—eg, increased intake of vegetables and fruit, reductions in energy-dense nutrient-poor foods and sugar sweetened beverages, and improvement in dietary behaviours such as encouraging mealtime routines and family meals. 110 , 112 One common approach, the traffic light diet, categorises foods by energy density, with green low-energy foods that can be eaten freely, yellow foods eaten moderately, and red foods eaten occasionally due to a higher energy-density. 107 Dietary approaches aim to be nutritionally complete and to address and prevent nutritional deficiencies. 113 , 114 However, children and adolescents might present for obesity treatment with relatively poor diet quality; 115 therefore, an initial goal of improving the baseline diet might be appropriate. Selection of dietary strategies should be informed by individual preference and circumstances, family environment, and available support.

Physical activity

Physical activity components might include provision of education or a structured exercise programme, or both, in line with local guidelines. The goals of exercise interventions should be to offer a safe, supportive, fun, and non-judgemental environment for children with obesity to engage in active play. It can also enable socialisation with peers and facilitate motor competence, confidence, and optimisation of fundamental motor skills. The aims of exercise itself are to increase physical fitness, reduce or attenuate obesity-related complications, improve quality of life, and support the child to reach age-appropriate physical activity levels. 116 , 117 Studies have found that the most effective exercise interventions consist of sessions lasting 60 min or more on at least 3 days per week for at least 12 weeks duration. 118 Training programmes should be tailored to the child's physical abilities and fitness level evaluated at baseline using standardised and age-appropriate outcome measures. Intervention should be fun, leverage the preferences of the child while following frequency, intensity, duration, type, volume, and progression principles. 119

Children with obesity often experience personal barriers to movement and exercise. Therefore tailoring and adapting paediatric exercise interventions will often be necessary, particularly for those that report musculoskeletal pain, high rates of fatigue, urinary incontinence, skin chafing, or have impaired motor skills. Additionally, the presence of intellectual or physical disabilities should be considered. As such, the type of exercise intervention offered will vary according to the child's clinical presentation and the desired outcome (eg, improvements in aerobic fitness, increased enjoyment, or reduction of fat-mass). The health professional might need to consider whether the intervention incorporates weight-bearing or non-weight bearing games, aerobic, proprioceptive and resistance exercises, individual or group-based work, or whether specific physiotherapy approaches might also need to be integrated to address underlying impairments. Appropriate monitoring and evaluation of the exercise intervention is recommended and should include the perspective of the child in addition to psychometrically robust outcome measurement. Additional guidance is available elsewhere. 120 , 121 , 122

Screen time and sedentary behaviours

Sedentary behaviours, including screen time, are distinct from physical activity and need to be addressed as part of a comprehensive behavioural change programme. Interventions that are successful in decreasing screen time in the short term include strong parental engagement, structural changes in the home environment (eg, removing or replacing home or bedroom electronic games access), and e-monitoring of time on digital devices. 123 These interventions tend to be more effective in young children.

There are few trials targeting sleep in the treatment of paediatric obesity, especially in older children and adolescents. Sleep interventions in preschool-aged children are associated with reduced weight gain. 124 Improvements in sleep hygiene, such as a consistent bedtime routine, regular sleep-wake times, and reduced screen times in the evening, are likely to have many co-benefits and positive effects on other weight-related behaviours.

Behavioural support strategies

Changes in dietary intake, physical activity, sedentary behaviours, and sleep are underpinned by strategies supporting behaviour change with the vast majority of interventions using a form of behavioural therapy. Common behaviour change techniques include goal setting, stimulus control (modifying the environment), and self-monitoring. 107 , 125 Motivational interviewing techniques such as reflective listening and shared decision making might also be used by healthcare workers to improve motivation for behaviour change. 126 , 127

The effectiveness of behaviour change interventions are well described, with modest reductions in weight-related outcomes 128 , 129 and improvements in cardiometabolic health. 130 The 2017 Cochrane reviews 128 , 129 found that behaviour changing interventions were more successful than no treatment or usual care comparators in reducing BMI (–0·53 kg/m 2 [95% CI –0·82 to –0·24], low-quality evidence in children; –1·18 kg/m 2 [–1·67 to –0·69], low-quality evidence in adolescents), and BMI z score (–0·06 units [–0·10 to –0·02], low-quality evidence in children; –0·13 [–0·21 to –0·05], low quality evidence in adolescents). 128 , 129 Effects were maintained at 18 to 24 months' follow-up for both BMI and BMI z-score in adolescents. 128 In children and adolescents aged 5–18 years, behavioural interventions are also associated with reductions in total cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting insulin, and HOMA-insulin resistance 130 as well as increased sleep duration and a reduced prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea. 131

A systematic review of 109 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) found that dietary interventions achieve a modest reduction in energy intake, reduced intake of sugar sweetened beverages, and increased intake of fruit and vegetables in children and adolescents aged 2–20 years. 132 The beneficial effects of supervised exercise in children and adolescents with obesity on measures of anthropometry and adiposity include reductions in BMI, bodyweight, waist circumference, and percent body fat. 133 Improvements in obesity-related complications are also observed, independent of changes in anthropometry including increased cardiorespiratory fitness, 134 improved muscle performance 80 and fundamental motor skills, 135 reductions in insulin resistance, reductions in fasting glucose and insulin levels, 136 improved lipid profile, 137 and reductions in blood pressure. 138 , 139 Exercise might also yield additional benefits related to appetite and response to food cues.

Behavioural obesity treatment is also associated with improved psychosocial health, including improved quality of life, 128 , 140 and body image 141 compared with no treatment or usual care comparators post-intervention and improvements in self-esteem at latest follow-up in those aged 4–19 years at baseline. 141 In assessing mental health, no difference between intervention and no-treatment comparator groups have been seen for the changes in symptoms of depression, 142 anxiety, 142 and eating disorders, 143 during the intervention period. However, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating disorders are reduced post-intervention or at follow-up in intervention arms, with no worsening of symptoms within groups. 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 Adverse effects of lifestyle interventions are poorly reported. 128 , 129 Where reported, no significant differences in adverse events between intervention and control groups are seen. 146

Psychological interventions

Psychological interventions, incorporated alongside traditional behavioural obesity treatment strategies, or as stand-alone interventions, target psychological factors that might contribute to eating behaviours and obesity, including distorted body image, negative mood, and stimulus control. 125 , 147 A core objective of psychological interventions is to reduce barriers for behaviour change. 147 Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the most frequently used approach, and addresses the relationship between cognitions, feelings, and behaviours using behavioural therapy techniques to modify behaviours and cognitive techniques to modify dysfunctional cognitions. 125 CBT-based interventions have been shown to result in healthier food habits, improved psychosocial health, quality of life, self-esteem, and anthropometric variables including BMI and waist circumference in children and adolescents. 125 Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which encourage acceptance rather than avoidance of internal experiences (eg, food cravings), have shown to be effective in the management of obesity in adults and are an emerging area of research in adolescence. Pilot studies have found ACT-based interventions to be feasible and acceptable in adolescents with obesity, 148 , 149 with further research underway. Weight-neutral interventions, aiming to promote healthy behaviours and improve physical and psychosocial health without promoting weight loss, are an emerging area of practice in adults. There is currently insufficient evidence to guide the use of weight-neutral approaches in paediatrics.

Mode of intervention delivery

Evidence for behavioural change programmes encompass a variety of modes of delivery including group programmes, one-on-one therapist sessions, and various forms of e-health support. 128 , 129 , 150 , 151 No one form is necessarily superior to another, although a combination of such approaches might be used in a comprehensive integrated programme. Availability of resources; time constraints for health professionals, patients, and families; and appropriate health professional training will influence treatment provided alongside the child's developmental stage and patient or parent preferences. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for effective interventions that can be delivered remotely without exacerbating existing social and technological disparities. 152 A 2021 review describes the considerations for successful implementation for such telemedicine approaches. 153

Eating disorders risk management

Children and adolescents with obesity are vulnerable to the development of eating disorders because obesity and eating disorders have several shared risk factors. 76 , 154 Disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, as precursors to eating disorders, are also elevated in children and adolescents with obesity. 155 Although obesity treatment helps improve eating disorder symptoms, including binge eating and loss of control in most youth with obesity, 143 , 144 a small number undergoing obesity treatment might develop an eating disorder during or after an intervention. 143 Although whether this low risk of developing eating disorders differs in youth who do not present for clinical treatment remains unclear, it is an important consideration for clinicians providing obesity care. For over a decade, it has been recommended that there be screening of disordered eating attitudes and behaviours before obesity treatment, 76 , 154 particularly with the use of dietary interventions, 112 to identify undiagnosed eating disorders. However, guidance on how this should occur in practice is scarce. Screening tools that assess for binge eating disorder specifically in children 156 and adolescents 157 with obesity are available but a self-report screening tool to assess for the broad spectrum of eating disorders for those with obesity and with adequate diagnostic accuracy is lacking. Eating disorder symptoms should not prevent the provision of obesity care; 158 rather, a combination of self-report questionnaires and clinical assessment might be needed to assess and monitor eating disorder risk in practice. 76

Intensive dietary interventions

Use of intensive dietary interventions is an emerging area of research and practice, particularly in post-pubertal adolescents with obesity related comorbidity or severe obesity. 110 , 159 Prescriptive dietary approaches may be delivered within the context of a multicomponent behavioural intervention, by experienced paediatric dietitians with medical supervision. 159 Very Low Energy Diets (VLEDs), consisting of an energy prescription of approximately 800 kcal/day or less than 50% of estimated energy requirements, often involving the use of nutritionally complete meal replacement products, are one such option. A meta-analysis of 20 studies found VLEDs to be effective at inducing rapid short term weight loss in children and adolescents with obesity (–10·1kg [95% CI 8·7 to 11·4] over 3 to 20 weeks), though follow-up beyond 12-months is scarce. 160 Data on VLEDs in the treatment of youth with early onset type 2 diabetes are limited to a small pilot study 161 and a medical chart review, 162 however, they have shown early short-term success and the possibility of reducing the requirement for medication, including insulin, and inducing remission of diabetes. 163 However, there is need for further research. 163 Variations in macronutrient distribution have been widely studied due to hypothesised effects on satiety, particularly higher protein (20–30% of energy intake from protein) approaches and very low carbohydrate diets (<50g per day or <10% energy from carbohydrate) aiming to induce ketosis. Although lower carbohydrate approaches show a significantly greater reduction in weight-related outcomes in the short-term (<6 months), dietary patterns with varied macronutrient distribution do not show superior effects in the longer term in children and adolescents. 164 Pilot studies on the use of various regimens of intermittent energy restriction in adolescents with obesity have shown these to be feasible and acceptable. 165 , 166 Larger trials are underway.

Anti-obesity medications

Anti-obesity medications are an important part of comprehensive obesity treatment. Pharmacotherapy, when combined with behavioural change interventions, can be particularly useful in patients for whom behavioural approaches alone have proven suboptimal or unsuccessful in reducing BMI and improving obesity-related complications. Although regulatory approval and availability varies by country and region, there is one anti-obesity medication that is approved by most regulatory agencies (including the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency) for chronic obesity treatment in adolescents aged 12–18 years, which is liraglutide at 3 mg daily. Liraglutide, delivered via subcutaneous injection, belongs to the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist class, which acts on its receptors in the hypothalamus to reduce appetite, slow gastric motility, and act centrally on the hind brain to enhance satiety. 167 In the largest RCT of liraglutide 3 mg among adolescents (12 to <18 years old) with obesity, whereby all participants also received lifestyle therapy, the mean placebo-subtracted BMI reduction was approximately 5% with one year of treatment. 168 More participants in the liraglutide versus placebo group had a decline in BMI by 5% (43·3% liraglutide vs 18·7% placebo) and 10% (26·1% liraglutide vs 8·1% placebo). Importantly, no new safety signals were observed in the adolescent trial in relation to previous adult trials. The most reported adverse events were gastrointestinal and were more frequent in the liraglutide group (64·8% liraglutide vs 36·5% placebo). No statistically significant improvements in cardiometabolic risks factors or quality of life were observed between groups.