- Recent Searches Clear

Welcome to the new home of Guidelines in Practice

Browse our expert articles to support best practice for UK healthcare professionals.

Improving Chronic Disease Management in Primary Care: Case Studies

Disclosures.

GP, Barry; Community Director for Quality Improvement and Clinical Innovation, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board

Dr Richard Baxter Examines Five Case Studies in Which a Structured Approach to Chronic Disease Management (CDM) Has Improved Care, and Presents a Framework for CDM Optimisation

In England, treatment and care for people with long-term conditions are thought to account for 70% of health and social care expenditure. 1 An effective approach to chronic disease management (CDM) is therefore vital if primary care is to accommodate the rising tide of CDM requirements without drowning—but how can primary care providers structure this management without losing patient, community, and workforce engagement or inadvertently increasing health inequalities?

This question is addressed in this article, in which I:

- briefly explore how disparate contractual arrangements in England, Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland encourage differing approaches to CDM

- discuss five case studies that show how introducing a structured approach can deliver efficiencies and transform care

- present a nascent framework that I am helping to develop with colleagues across Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (UHB), setting out some factors that are critical to an effective, comprehensive, engaging, and equitable CDM process.

Important Considerations in CDM

As leaders of healthcare systems have tried to implement some of the theoretical frameworks associated with CDM—including the Chronic Care Model (CCM), Minimally Disruptive Medicine, the Patient-Centred Medical Home, and the Ten Building Blocks of High-Performing Primary Care 2,3 —a number of important considerations have emerged. These critical success factors are examined below, and also reflected in the case studies discussed later in this article.

Patients' engagement with care and ownership of their conditions is now recognised as essential for improving CDM. 4 In studies using the CCM, improved outcomes have been seen with initiatives for managing long-term diseases that involve effective design of the care-delivery system and that support patients to engage in self-management. 2 In addition, a focus on multimorbidity (including frailty), rather than single diseases, is increasingly recognised as important to clinical outcomes, although evidence is sparse concerning the practical application of methods to balance treatment burden and CDM. 5–7

Effective use of the wider clinical team can help to maximise the use of limited resources, the idea being that CDM services are led, but do not always need to be delivered, by GPs. 8 Involving pharmacists in primary care, through comprehensive medication reviews alongside clinical condition reviews, is a measure that has been shown to improve a range of clinical outcomes. 9 However, this adaptation is associated with challenges regarding continuity of care, which is more difficult to deliver across a multiclinician team. 10

Any health-improvement initiative must also be structured in a way that ensures that inequalities are not inadvertently increased. The Deep End Project, involving GPs working in 100 practices serving the most socioeconomically deprived communities in Scotland, is a reminder of this: it was found that differential uptake of quality-improvement initiatives by different social groups only served to widen health inequalities. 11

Contracts, Frameworks, and Quality-Improvement Incentives across the UK

The way in which quality improvement and CDM are financially incentivised may have a significant impact on the way that CDM is organised now and in the future, as can be seen in the differences between the UK nations.

England and Northern Ireland

In England, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) is still in place—at least until the 2023–2024 GP Contract is completed, when the QOF is to be reviewed. 12 This framework does ensure universal incentives and target-specific funding, but it seems to do little to promote the more difficult work involved in CDM, such as chasing people who are hard to reach and persevering with those whose disease is hard to control. It also suffers from a rush to meet specific, and increasingly challenging, disease-control and health-promotion targets by 1 April each year. 13 The QOF is in place in Northern Ireland as well, but it is organised by the Northern Ireland Department of Health’s Strategic Planning and Performance Group instead of NHS England. 14

However, although the QOF may focus efforts on patients who are easier to reach or control at a practice level, the Primary Care Network (PCN) Directed Enhanced Service (DES) in England, with its associated Investment and Impact Fund, is an alternative source of funding that PCNs could use to deliver CDM more comprehensively and effectively, as it facilitates the introduction of shared staff—such as pharmacists, link workers, paramedics, and physician associates—across localities. 15,16

In Wales, the QOF was replaced by the Quality Assurance and Improvement Framework (QAIF) in 2019, with fewer specific targets and a greater emphasis on promoting practice improvements. 17 This year, funding for all clinical markers has been moved to the core General Medical Services contract, and assurance indicators have been removed 18,19 —therefore, practices retain the responsibility to deliver CDM but no longer have target-driven funding incentives. This change has the potential to free practices to concentrate their resources on higher-impact clinical activity; however, income is no longer reserved specifically for CDM, so it may be neglected.

The QOF was discontinued in Scotland in 2016 20 and, in 2018, a new contractual arrangement was phased in whereby GPs retain responsibility for their key roles—including undifferentiated presentations, complex care, local and whole-system quality improvement, and local clinical leadership—but other responsibilities pass to alternative healthcare professionals. 21,22 To this end, health boards and health and social care partnerships were originally supposed to reconfigure six key services over a 3-year period, including the provision of vaccinations, urgent care, and community link work. 21 However, reflecting the initiative’s slow progress during the pandemic, a revision in 2021 has focused the reforms on three priorities: the vaccination programme, pharmacotherapy, and community treatment and care services (including chronic disease monitoring). 23 The move from specific targets with dedicated funding to a broader promotion of healthcare improvements and changes in primary care infrastructure has the potential to help the NHS in Scotland to undertake a more radical overhaul of its CDM processes.

Case Studies on Improved CDM Processes

The following case studies are examples of initiatives across the UK through which developments in organisation and structure have improved CDM in primary care. They demonstrate the potential for primary care to make the CDM process much more efficient and effective. Key measures that have helped include:

- involvement of the multidisciplinary team (MDT)

- use of birth-month-aligned recall processes

- comprehensive planning.

Leeds: Improving Coordination Through Birth-Month-Aligned Reviews

As a result, both surgeries have increased their total numbers of reviews, achieved better patient monitoring, and found that, in general, the CDM process takes up less patient and clinician time because fewer services are being unnecessarily duplicated. 24 The change also helped the practice team to understand each other’s roles more clearly, and enabled greater visibility of where any individual patient is in their review process. 24

Bournemouth: Overhauling Medication Reviews with Pharmacist Support

In 2017–2018, Steve Williams took up the role of Senior Clinical Pharmacist at Westbourne Medical Centre (WMC) in Bournemouth as part of the NHS’s pilot scheme for practice-based clinical pharmacists. 25 He worked with Dr Lawrence Brad, the practice’s prescribing lead and one of its GP partners, to introduce a stratified structured medication review (SMR) system that enables patients with polypharmacy and multimorbidity to reliably receive appointments for comprehensive CDM review. 25 Through this process, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes, and who are on more than eight regular medicines, are invited for a CDM review that incorporates their multiple QOF reviews and SMR, after a blood test appointment. 26

This is one part of a whole package of improvements led by an effective MDT at the practice, with other measures including a major overhaul of the repeat prescription system and a drive to assess both process and patient outcomes. 27 Indeed, WMC estimates that the work of one full-time pharmacist has saved the practice 80 GP hours per month. 27

In general, the introduction of practice-based pharmacists into NHS primary care seems to have been an impactful and cost-effective intervention, reducing medicine-related problems, inappropriate prescribing, and unnecessary telephone consultations in general practice. 28,29 In my communications with Steve and Lawrence about this, Lawrence said: ‘A proactive, stratified SMR and CDM process provides an essential platform for the patient to engage in true shared decision making about their medications and, once undertaken, [the process] helps other clinicians to consult with [the patient with] much more efficiency and focus on any subsequent clinical presentation.’ 26 WMC is currently considering aligning its reviews with patients’ birth months in 2023–2024. 26

Supporting Pharmacists to Practise Safely

Although Steve and Lawrence are strong advocates for the involvement of clinical pharmacists in general practice, they are keen that these pharmacists are used and supported appropriately, and are leading initiatives in the Poole Bay and Bournemouth PCN to improve use of the MDT for CDM. 26,30 I have heard several anecdotes about pharmacists being used inappropriately or having a poor understanding of what they can, and should not, do. In my opinion, there is a pressing need for PCN clinical directors to understand and embrace this.

Staffordshire: Reducing Workload by Aligning Reviews to Birth Month

In 2019, after realising that repeat prescriptions and medication review processes were consuming a significant amount of GP time, a practice in Staffordshire serving 11,800 patients freed up the equivalent of 168 GP appointments per month by improving the structure of its medication review process. 31 The practice reduced repeat attendances by instituting more effective sequencing of investigations, creating a ‘one-stop shop’ in which patients receive clinical and pharmacist-led medication reviews in one visit. 31 It was found that aligning reviews loosely to a patient’s birthday and having a single point of organisation—the clinical pharmacist—maintained consistency in the process. 31 These improvements, which were made in collaboration with the whole team, are appreciated by patients considerably. 31

Subsequently, the practice discovered a downside to birth-month alignment: patient expectation (the other side of patient engagement) led to pressure on particular team members, who lacked the capacity to keep up. 32 The practice still offers a comprehensive review service of this kind, which streamlines blood tests, clinical review, and medication review, but the timing has been adjusted to match practice capacity. 32

Glamorgan: Reducing GP Involvement by Streamlining Processes

In 2019, Western Vale Family Practice (WVFP) employed a pharmacist, Rachel Brace, to help streamline their processes around CDM, SMRs, and QOF/QAIF achievement. 33 After much research and discussion, as well as audits, pilots, and attendance at a costing workshop, the practice developed and launched a comprehensive, birth-month-aligned annual review process in summer 2019. 33

The Streamlined Process

Prior to each patient’s birth month, review needs are collated and, for certain conditions, pre-appointment questionnaires are sent out. 33 Patients attend in person for blood tests and basic metrics, then undergo a clinical and medication review with an appropriate non-GP prescriber. 33 The choice of prescriber is based on individual prescribers’ scopes of practice, and patients can choose between telephone and face-to-face reviews. 33 Subsequently, when safe to do so and when a person’s conditions are well controlled, medications are authorised and issued through repeat dispensing for the appropriate maximum periods. 33

WVFP has concentrated on streamlining this process for patients with simpler, well-controlled conditions, through paper reviews where appropriate, so that time can be reserved for more complex or vulnerable patients. 33 When conditions need better control, these patients are passed to a named clinician to designate responsibility and ensure continuity of care. 33

Impact and Reception

It is generally accepted at the practice that this process makes the best use of the MDT’s full range of knowledge and skills, including those of nurse practitioners, healthcare assistants, pharmacists, and pharmacy technicians. 33 Through this service, over 90% of the practice’s CDM activity can be delivered safely and effectively without direct GP involvement, and the team has noticed many improvements as a result, including: 33

- improved diagnostic coding

- clinicians not having to worry about opportunistic delivery

- increased condition coverage.

Patients seem to approve of the approach, coining the phrase ‘birthday MOT’ to describe it, and no patient has yet said that they would rather see a GP. 33 GPs are also satisfied that they can concentrate on more complex cases, with one GP even describing the CDM team as ‘the elves of chronic disease’ because everything seems to happen seamlessly behind the scenes. 33 Furthermore, when this process was presented at a meeting of their patient interest group, the All Wales Therapeutics and Toxicology Centre expressed an interest. 33

WVFP continues to refine this process with ‘Plan, Do, Study, Act’ cycles, 34 and is currently working on inclusion of hormone-replacement therapy reviews, partly to adapt to the fragility of the supply chain. 33

Surrey: Performing Structured Medication Reviews at the PCN Level

In 2020, under the Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme, Nipa Patel was employed by a PCN in Surrey as a senior clinical pharmacist. 35 She introduced pharmacist-led SMRs to the practices in the PCN, with initial benefits identified including improvements in: 35

- inhaler prescribing

- patient self-awareness in diabetes management

- appropriate involvement of social prescribing

- communications between community, primary, and secondary care.

Implementing a Clear Recall Process with Follow-up Procedures

Annual recalls are arranged by a single text message, which includes a unique code that allows the patient to book a dedicated time slot online or over the phone. 37 After 7 days, nonresponders are chased directly to fill the remaining slots of this type. 37 When possible, if a patient does not attend, a designated care coordinator contacts them to ask why; however, most patients do attend their self-booked appointments. 37 The practices ensure consistency in their reviews and coding through appropriate training and use of third-party-designed templates. 37 When it is safe and measures are under control, repeat dispensing allows a community pharmacy to continue issuing a specific medication until the next annual review. 37 Those patients who require better control of disease markers are offered follow up by a single clinician to ensure continuity of care until control is achieved. 37

When I spoke to Nipa recently, she noted that the practices that have introduced this process are now significantly more effective at covering QOF, and report exceptions less often, than those that have not yet done so. 37 By structuring the review, the practices are also able to utilise many available allied health professionals’ roles more appropriately. 37 Clinicians at these two PCNs have commented that they prefer this method considerably to the 2-month rush to tick all the QOF boxes, and have noticed that the process allows for ‘more time for intricate clinical discussion and optimising treatment plans using shared decision making with patients’ . 37 Nipa has also noticed that there are downstream benefits on phlebotomy, hospital, and community services, as referrals are spread more evenly throughout the year. 37

The team is currently working on streamlining the physical checks to create more of a ‘one-stop shop' framework, as well as modelling future demand to workforce availability. 37

Cardiff and Vale UHB: Developing a Framework for Understanding CDM Processes

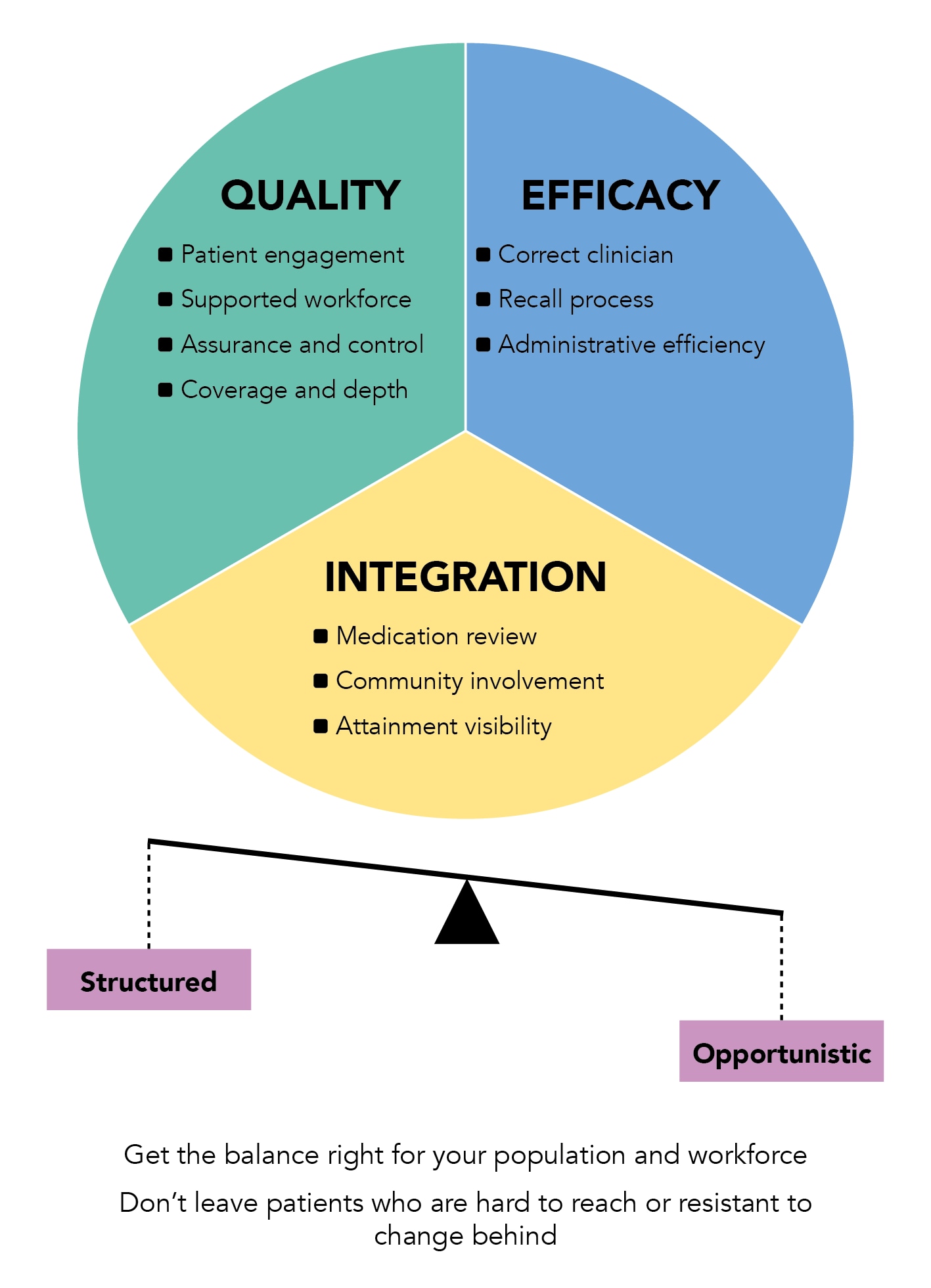

The five case studies presented above demonstrate that there are various ways to improve CDM services in the UK. In Cardiff and Vale UHB, we are currently developing a framework to help practices identify areas for improvement in their own CDM processes, outlined in Figure 1 and detailed below.

Areas for improvement fall broadly into 10 sections, which group into three domains—quality, efficacy, and integration—and are all affected by the balance of opportunistic versus structured CDM. In our experience, if clinicians are feeling the pressure to capture every opportunistic moment, this is evidence that their structured process lacks capacity or efficiency.

Figure 1: Areas to Consider When Optimising Chronic Disease Recall Processes

Quality Domain

An effective CDM process relies on providing a high-quality service that is flexible and consistent, with strong patient engagement, workforce support, and the ability to be measured, quality assured, and improved.

Patient Engagement

It is easy to see how the structure of any CDM process can strongly influence patient engagement, which is the key to any effective method of recalling patients. We have identified the following factors as particularly relevant:

- communication and clarity about what should occur and at what time

- choice of methods for contacting patients

- the optimum use of opportunistic moments (it is not inefficient to duplicate a message when it is timely)

- codesign with patient participation groups

- continuity of care (ideally continuity of care with a single contact, whether that is the choice of a patient or clinician)

- minimising the unnecessary burden of CDM, such as by reducing patient visits.

Supported Workforce

- supervision

- design of templates used in the CDM process

- everyone knowing how the system is meant to work, and having a route to bring forward improvements.

Coverage and Depth

In addressing its CDM coverage, a practice may wish to consider allocating greater seniority or more time to those patients with greater need or more challenging circumstances. If the same patients miss their review every year, this may also need to be addressed with a different approach.

Assurance and Control

If a CDM process is to be effective, the people delivering it will benefit immensely from the ability to measure and assess relevant metrics, allowing them to check whether they are delivering care as intended and work out how they can tackle abnormal results. Continuous quality improvement is a key aspect of assurance and control.

Efficacy Domain

A worthwhile CDM process must be effective in the ways it utilises clinicians, recalls patients, and is administered.

Correct Clinician

Failure to use clinicians to the full extent of their roles has possibly the greatest potential for waste, frustration, reduced quality, and excess cost. For a practice or PCN assessing whether it is using the correct clinician for any aspect of CDM, questions should include:

- do we have the right skill mix and number of clinicians to meet the chronic care needs of our patients, and are we able to calculate this?

- could we share workforce across our PCN or cluster?

- does our system reliably ensure that the right appointments occur at the right time?

- does everyone know what services each person can safely provide?

Recall Process

- with some systems, it is now possible for patients to receive a unique link that gives them access to a specified subset of appointments

- a receptionist ringing a list of patients may be more effective for improving attendance than a message asking those same patients to ring in

- pre-appointment questionnaires may be an effective way to save clinicians’ time

- use of an app may be cheaper than use of a text-messaging service

- some methods of recall may result in lower did-not-attend rates, so may be more useful

- certain metrics may be more useful for assessing the cost effectiveness of a particular recall process, such as ‘cost per actual attendance’.

Administrative Efficiency

Integration domain.

To maximise effectiveness, a CDM framework needs to involve the coordination of processes, wider primary care services, and individual staff members.

Medication Review

The alignment of clinical and medication reviews, with both being comprehensive and performed by the correct clinician, is now well understood to be a fundamental part of an optimal CDM process, particularly for patients with polypharmacy, multimorbidity, or frailty.

Community Involvement

An effective system would easily allow other organisations to complement the review and management process. Community pharmacies are the obvious example of this, but community nursing, social services, and the voluntary sector are other providers that could enhance patient experience and quality of review in a system that deliberately considers their involvement.

Attainment Visibility

Clarity on the purpose, goals, and achievements of a CDM process is essential for its success. When a clinician or receptionist is deciding whether to take an opportunity to discuss CDM with a patient, for example, it is useful for them to know how well the review process is going, both in general and for the individual patient. The benefits are enhanced if the staff member in question knows how and when reviews will occur—this is especially evident when reviews are aligned by birth month.

Ambitions at Cardiff and Vale UHB

Our next step with this framework is to identify critical questions, exercises, and measures that can be used to appraise primary care recall systems more objectively. We would welcome any comments on our proposed framework, including any other factors, objective measures, or exercises we should include.

I have presented here several case studies that illustrate the benefits, and potential challenges, of structuring CDM recall in a more systematic way, particularly by birth month. Although other methods of organisation—such as by multimorbidity, polypharmacy, disease severity, or level of engagement—have also been demonstrated to be effective, all of these can be combined within a primarily birth-month-aligned approach.

It is unclear how prevalent this birth-month-aligned approach to CDM is, and therefore what opportunities exist for any consequent improvements in health, patient experience, cost, and clinical work life. Within Cardiff and Vale UHB, about 20% of practices have adopted this model, and we are working to refine it and collect more evidence of its effects so that we can scale it effectively. Other practitioners I have spoken with have estimated that up to 50% of practices in their area have adopted the model. Personally, I think that this model is a potential key to the transformational improvements the NHS so desperately needs, and I welcome communication from anyone about it, particularly concerning any issues they have experienced with this approach and any information they have about its prevalence across the UK.

EDITOR'S RECOMMENDATIONS

Measles: Diagnosis, Assessment, and Management

NHS England | New 29 May 2024

Case Studies in CVRM and CKD: Dr Kevin Fernando, Dr Jim Moore, and Professor Raj Thakkar's Guidelines Live Session

Video | Professor Raj Thakkar, Dr Kevin Fernando, Dr Jim Moore | 28 May 2024

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Webmd network.

Diabetes as a case study of chronic disease management with a personalized approach: the role of a structured feedback loop

Affiliation.

- 1 Insititut d'Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS) and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (CIBERDEM), Hospital Clínic Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. [email protected]

- PMID: 22917639

- DOI: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.07.005

As non-communicable or chronic diseases are a growing threat to human health and economic growth, political stakeholders are aiming to identify options for improved response to the challenges of prevention and management of non-communicable diseases. This paper is intended to contribute ideas on personalized chronic disease management which are based on experience with one major chronic disease, namely diabetes mellitus. Diabetes provides a pertinent case of chronic disease management with a particular focus on patient self-management. Despite advances in diabetes therapy, many people with diabetes still fail to achieve treatment targets thus remaining at risk of complications. Personalizing the management of diabetes according to the patient's individual profile can help in improving therapy adherence and treatment outcomes. This paper suggests using a six-step cycle for personalized diabetes (self-)management and collaborative use of structured blood glucose data. E-health solutions can be used to improve process efficiencies and allow remote access. Decision support tools and algorithms can help doctors in making therapeutic decisions based on individual patient profiles. Available evidence about the effectiveness of the cycle's constituting elements justifies expectations that the diabetes management cycle as a whole can generate medical and economic benefit.

Copyright © 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Blood Glucose*

- Case Management / organization & administration*

- Chronic Disease / therapy*

- Decision Support Techniques

- Diabetes Mellitus / blood

- Diabetes Mellitus / therapy*

- Patient Compliance* / statistics & numerical data

- Patient-Centered Care / standards

- Quality of Health Care

- Quality of Life

- Blood Glucose

The Business Case for Diabetes Disease Management

What should business people in particular know about the pros and cons of attempts to treat and control diabetes—or indeed other chronic diseases?

That was the focus of a lively case-study discussion among some fifty participants led by HBS professor Nancy Beaulieu at the 2003 Alumni Healthcare Conference on November 7.

Beaulieu's research focuses on many aspects of healthcare—including contracting, quality competition in managed care, and human capital management and performance measurement. At the session, she prodded her alumni "students" in classic HBS case-study fashion to analyze the complexities of disease management and check all avenues for potential business opportunities. The participants, almost all of them health professionals, sorted through the risks and benefits of disease management for patients, employers, health plans, doctors and nurses, and society.

In the end, participants agreed that while disease management is a thorny concept involving all these many constituencies, it might in some instances leave room for business potential in the form of a carve-out. A carve-out, as defined in the paper "The Business Case for Diabetes Disease Management" that Beaulieu co-wrote to launch the discussion, works like this:

"In a carve-out arrangement, a private disease management vendor typically takes on full risk for the care of patients with specific diseases like diabetes. The health plan typically identifies its diabetic patients, and then the vendor is placed financially at risk for the costs of patient medical care and is responsible for coordinating all aspects of care for those patients. The vendor is often also involved with other chronically ill patients of the same health plan—for example, those with asthma or hypertension."

Why Diabetes Is A Good Case

But first, diabetes. Beaulieu chose diabetes as a context in which to spark discussion on organizational and financial systems for several reasons, she said. It is a very prevalent disease: as Beaulieu and co-authors David Cutler and Katherine Ho noted in their study, it is the seventh leading cause of death in the U.S. Its economic burden is also high, since it is linked to other afflictions such as heart and renal disease and blindness.

And, she added, one of the most important aspects of this disease is that the medical profession already knows how to treat it. "We have the medical knowledge to do it. And it's not being done. Just under one-half of identified diabetics in this country don't have their blood sugar under control," she said.

Diabetes manifests as Type I or Type II and, as one participant pointed out, the most appropriate care involves some tailoring. But in general, it is well recognized that diabetes can lead to long-term complications and short- and long-term costs. As Beaulieu and her co-authors learned, diabetics may make up between 3 and 10 percent of a typical health plan's membership. It typically costs about $1,000 a year to treat a newly diagnosed diabetic patient; obviously, the numbers go up if a diabetic suffers serious complications.

Healthcare providers have attempted a number of disease management strategies over the last ten years or so. The diabetes programs have varied, but all are linked by the idea that patients can and should become educated about their disease and be proactive in taking care of their health. According to Beaulieu and her co-authors, disease management is focused on prevention and control, not acute care. "The aim is to improve the coordination of care and to reduce the number of hospitalizations and severe complications among diabetic patients," they wrote.

Disease management, then, can take several approaches. The simplest is probably for the healthcare provider to offer a monitoring system for patients who have already been diagnosed as diabetics, sending out e-mail or making phone calls to remind patients of test and checkup dates. Another route is to offer a combined monitoring, tracking, and alert system. This method automatically lets the healthcare provider know if patients skip their tests or if a more intensive treatment seemed warranted by the latest test results. A third approach—less common—is to create a coordinated "virtual team" around the patient, by sharing lab data, insurance claims data, and pharmacy data in an attempt to enhance overall care.

Another part of diabetes disease management programs aims not at current diabetics but at identifying members of the health plan who seem at particularly high risk of developing the disease within the next couple of years. This kind of program is harder for health plans to implement, according to Beaulieu and her co-authors, because it requires data collection and analysis tools, since potential diabetics are identified on the basis of pharmacy and lab data as well as questionnaires and surveys. Not many organizations have ventured into this element of disease management.

In their case-study discussion, participants at the conference mulled over the strategies of HealthPartners, an independent nonprofit that is one of three health maintenance organizations (HMOs) in the Minneapolis market. HealthPartners has an enrollment of about 675,000 people, and its network consists of approximately 3,700 primary care physicians and 4,500 specialists, according to Beaulieu and her co-authors. In the 1990s, it began a program with two elements similar to those outlined above: one to focus on plan members who already had diabetes, and another to focus on members at risk of developing diabetes.

Analyzing HealthPartners, Beaulieu and her co-authors found that such programs could lose money in the first one to three years and so would not break even in a three-year time period. Allowing an eight- to twelve-year period, however, would be more realistic for a break even, they suggested.

Treating A Silent Killer

Participants in the case study said that as a "silent killer" diabetes requires behavioral and lifestyle changes that are difficult for many patients to commit to, even patients with the best intentions. Privacy was another concern: Would employees be "penalized" if they were recognized as patients? Or would sick people flock to employers who offered a too-generous plan? Since long-term effects of the disease are measured in decades, it is complicated to figure out a business case for diabetes, said one alumnus. Participants said that since many people with diabetes have multiple diseases, as business people they did not know whether it would be better economically to treat such a chronic disease on "one system" or just focus on the individual elements of diabetes.

Some participants suggested that Medicare and society might have more of a stake in diabetes disease management than employers. Medicare usually foots the bill for end-stage renal disease, one result of untreated diabetes. An economic case would be difficult to make to employers and health plans, some said: If employee turnover was high, then it would be difficult to economically justify such a time-dependent proposal as diabetes disease management. On the other hand, workplace productivity savings could be the key. According to another alumnus, any outlay "is petty change" to employers compared to the savings of keeping healthy people.

Though wide-ranging, the discussion was underscored by the fact that the growth in incidence of diabetes is a public health crisis that needs urgent attention. However flawed, early programs that attempt to manage the disease may at least get more people thinking about serious solutions for their businesses and communities.

- 28 May 2024

- In Practice

Job Search Advice for a Tough Market: Think Broadly and Stay Flexible

- 22 May 2024

Banned or Not, TikTok Is a Force Companies Can’t Afford to Ignore

- 22 Nov 2023

- Research & Ideas

Humans vs. Machines: Untangling the Tasks AI Can (and Can't) Handle

- 27 Jun 2016

These Management Practices, Like Certain Technologies, Boost Company Performance

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- Human Resources

- Innovation and Invention

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

- Login / Register

‘These three individuals will leave very big shoes to fill’

STEVE FORD, EDITOR

- You are here: COPD

Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study

04 May, 2020

This case study explains the symptoms, causes, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This article uses a case study to discuss the symptoms, causes and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, describing the patient’s associated pathophysiology. Diagnosis involves spirometry testing to measure the volume of air that can be exhaled; it is often performed after administering a short-acting beta-agonist. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease involves lifestyle interventions – vaccinations, smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation – pharmacological interventions and self-management.

Citation: Price D, Williams N (2020) Diagnosis and management of COPD: a case study. Nursing Times [online]; 116: 6, 36-38.

Authors: Debbie Price is lead practice nurse, Llandrindod Wells Medical Practice; Nikki Williams is associate professor of respiratory and sleep physiology, Swansea University.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

Introduction

The term chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is used to describe a number of conditions, including chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Although common, preventable and treatable, COPD was projected to become the third leading cause of death globally by 2020 (Lozano et al, 2012). In the UK in 2012, approximately 30,000 people died of COPD – 5.3% of the total number of deaths. By 2016, information published by the World Health Organization indicated that Lozano et al (2012)’s projection had already come true.

People with COPD experience persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that can be due to airway or alveolar abnormalities, caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases, commonly from tobacco smoking. The projected level of disease burden poses a major public-health challenge and primary care nurses can be pivotal in the early identification, assessment and management of COPD (Hooper et al, 2012).

Grace Parker (the patient’s name has been changed) attends a nurse-led COPD clinic for routine reviews. A widowed, 60-year-old, retired post office clerk, her main complaint is breathlessness after moderate exertion. She scored 3 on the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale (Fletcher et al, 1959), indicating she is unable to walk more than 100 yards without stopping due to breathlessness. Ms Parker also has a cough that produces yellow sputum (particularly in the mornings) and an intermittent wheeze. Her symptoms have worsened over the last six months. She feels anxious leaving the house alone because of her breathlessness and reduced exercise tolerance, and scored 26 on the COPD Assessment Test (CAT, catestonline.org), indicating a high level of impact.

Ms Parker smokes 10 cigarettes a day and has a pack-year score of 29. She has not experienced any haemoptysis (coughing up blood) or chest pain, and her weight is stable; a body mass index of 40kg/m 2 means she is classified as obese. She has had three exacerbations of COPD in the previous 12 months, each managed in the community with antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol.

Ms Parker was diagnosed with COPD five years ago. Using Epstein et al’s (2008) guidelines, a nurse took a history from her, which provided 80% of the information needed for a COPD diagnosis; it was then confirmed following spirometry testing as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) guidance.

The nurse used the Calgary-Cambridge consultation model, as it combines the pathological description of COPD with the patient’s subjective experience of the illness (Silverman et al, 2013). Effective communication skills are essential in building a trusting therapeutic relationship, as the quality of the relationship between Ms Parker and the nurse will have a direct impact on the effectiveness of clinical outcomes (Fawcett and Rhynas, 2012).

In a national clinical audit report, Baxter et al (2016) identified inaccurate history taking and inadequately performed spirometry as important factors in the inaccurate diagnosis of COPD on general practice COPD registers; only 52.1% of patients included in the report had received quality-assured spirometry.

Pathophysiology of COPD

Knowing the pathophysiology of COPD allowed the nurse to recognise and understand the physical symptoms and provide effective care (Mitchell, 2015). Continued exposure to tobacco smoke is the likely cause of the damage to Ms Parker’s small airways, causing her cough and increased sputum production. She could also have chronic inflammation, resulting in airway smooth-muscle contraction, sluggish ciliary movement, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of mucus-secreting goblet cells, as well as release of inflammatory mediators (Mitchell, 2015).

Ms Parker may also have emphysema, which leads to damaged parenchyma (alveoli and structures involved in gas exchange) and loss of alveolar attachments (elastic connective fibres). This causes gas trapping, dynamic hyperinflation, decreased expiratory flow rates and airway collapse, particularly during expiration (Kaufman, 2013). Ms Parker also displayed pursed-lip breathing; this is a technique used to lengthen the expiratory time and improve gaseous exchange, and is a sign of dynamic hyperinflation (Douglas et al, 2013).

In a healthy lung, the destruction and repair of alveolar tissue depends on proteases and antiproteases, mainly released by neutrophils and macrophages. Inhaling cigarette smoke disrupts the usually delicately balanced activity of these enzymes, resulting in the parenchymal damage and small airways (with a lumen of <2mm in diameter) airways disease that is characteristic of emphysema. The severity of parenchymal damage or small airways disease varies, with no pattern related to disease progression (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2018).

Ms Parker also had a wheeze, heard through a stethoscope as a continuous whistling sound, which arises from turbulent airflow through constricted airway smooth muscle, a process noted by Mitchell (2015). The wheeze, her 29 pack-year score, exertional breathlessness, cough, sputum production and tiredness, and the findings from her physical examination, were consistent with a diagnosis of COPD (GOLD, 2018; NICE, 2018).

Spirometry is a tool used to identify airflow obstruction but does not identify the cause. Commonly measured parameters are:

- Forced expiratory volume – the volume of air that can be exhaled – in one second (FEV1), starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres);

- Forced vital capacity (FVC) – the total volume of air that can be forcibly exhaled – at timed intervals, starting from a maximal inspiration (in litres).

Calculating the FEV1 as a percentage of the FVC gives the forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC). This provides an index of airflow obstruction; the lower the ratio, the greater the degree of obstruction. In the absence of respiratory disease, FEV1 should be ≥70% of FVC. An FEV1/FVC of <70% is commonly used to denote airflow obstruction (Moore, 2012).

As they are time dependent, FEV1 and FEV1/FVC are reduced in diseases that cause airways to narrow and expiration to slow. FVC, however, is not time dependent: with enough expiratory time, a person can usually exhale to their full FVC. Lung function parameters vary depending on age, height, gender and ethnicity, so the degree of FEV1 and FVC impairment is calculated by comparing a person’s recorded values with predicted values. A recorded value of >80% of the predicted value has been considered ‘normal’ for spirometry parameters but the lower limit of normal – equal to the fifth percentile of a healthy, non-smoking population – based on more robust statistical models is increasingly being used (Cooper et al, 2017).

A reversibility test involves performing spirometry before and after administering a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) such as salbutamol; the test is used to distinguish between reversible and fixed airflow obstruction. For symptomatic asthma, airflow obstruction due to airway smooth-muscle contraction is reversible: administering a SABA results in smooth-muscle relaxation and improved airflow (Lumb, 2016). However, COPD is associated with fixed airflow obstruction, resulting from neutrophil-driven inflammatory changes, excess mucus secretion and disrupted alveolar attachments, as opposed to airway smooth-muscle contraction.

Administering a SABA for COPD does not usually produce bronchodilation to the extent seen in someone with asthma: a person with asthma may demonstrate significant improvement in FEV1 (of >400ml) after having a SABA, but this may not change in someone with COPD (NICE, 2018). However, a negative response does not rule out therapeutic benefit from long-term SABA use (Marín et al, 2014).

NICE (2018) and GOLD (2018) guidelines advocate performing spirometry after administering a bronchodilator to diagnose COPD. Both suggest a FEV1/FVC of <70% in a person with respiratory symptoms supports a diagnosis of COPD, and both grade the severity of the condition using the predicted FEV1. Ms Parker’s spirometry results showed an FEV1/FVC of 56% and a predicted FEV1 of 57%, with no significant improvement in these values with a reversibility test.

GOLD (2018) guidance is widely accepted and used internationally. However, it was developed by medical practitioners with a medicalised approach, so there is potential for a bias towards pharmacological management of COPD. NICE (2018) guidance may be more useful for practice nurses, as it was developed by a multidisciplinary team using evidence from systematic reviews or meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials, providing a holistic approach. NICE guidance may be outdated on publication, but regular reviews are performed and published online.

NHS England (2016) holds a national register of all health professionals certified in spirometry. It was set up to raise spirometry standards across the country.

Assessment and management

The goals of assessing and managing Ms Parker’s COPD are to:

- Review and determine the level of airflow obstruction;

- Assess the disease’s impact on her life;

- Risk assess future disease progression and exacerbations;

- Recommend pharmacological and therapeutic management.

GOLD’s (2018) ABCD assessment tool (Fig 1) grades COPD severity using spirometry results, number of exacerbations, CAT score and mMRC score, and can be used to support evidence-based pharmacological management of COPD.

When Ms Parker was diagnosed, her predicted FEV1 of 57% categorised her as GOLD grade 2, and her mMRC score, CAT score and exacerbation history placed her in group D. The mMRC scale only measures breathlessness, but the CAT also assesses the impact COPD has on her life, meaning consecutive CAT scores can be compared, providing valuable information for follow-up and management (Zhao, et al, 2014).

After assessing the level of disease burden, Ms Parker was then provided with education for self-management and lifestyle interventions.

Lifestyle interventions

Smoking cessation.

Cessation of smoking alongside support and pharmacotherapy is the second-most cost-effective intervention for COPD, when compared with most other pharmacological interventions (BTS and PCRS UK, 2012). Smoking cessation:

- Slows the progression of COPD;

- Improves lung function;

- Improves survival rates;

- Reduces the risk of lung cancer;

- Reduces the risk of coronary heart disease risk (Qureshi et al, 2014).

Ms Parker accepted a referral to an All Wales Smoking Cessation Service adviser based at her GP surgery. The adviser used the internationally accepted ‘five As’ approach:

- Ask – record the number of cigarettes the individual smokes per day or week, and the year they started smoking;

- Advise – urge them to quit. Advice should be clear and personalised;

- Assess – determine their willingness and confidence to attempt to quit. Note the state of change;

- Assist – help them to quit. Provide behavioural support and recommend or prescribe pharmacological aids. If they are not ready to quit, promote motivation for a future attempt;

- Arrange – book a follow-up appointment within one week or, if appropriate, refer them to a specialist cessation service for intensive support. Document the intervention.

NICE (2013) guidance recommends that this be used at every opportunity. Stead et al (2016) suggested that a combination of counselling and pharmacotherapy have proven to be the most effective strategy.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Ms Parker’s positive response to smoking cessation provided an ideal opportunity to offer her pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) – as indicated by Johnson et al (2014), changing one behaviour significantly increases a person’s chance of changing another.

PR – a supervised programme including exercise training, health education and breathing techniques – is an evidence-based, comprehensive, multidisciplinary intervention that:

- Improves exercise tolerance;

- Reduces dyspnoea;

- Promotes weight loss (Bolton et al, 2013).

These improvements often lead to an improved quality of life (Sciriha et al, 2015).

Most relevant for Ms Parker, PR has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression, which are linked to an increased risk of exacerbations and poorer health status (Miller and Davenport, 2015). People most at risk of future exacerbations are those who already experience them (Agusti et al, 2010), as in Ms Parker’s case. Patients who have frequent exacerbations have a lower quality of life, quicker progression of disease, reduced mobility and more-rapid decline in lung function than those who do not (Donaldson et al, 2002).

“COPD is a major public-health challenge; nurses can be pivotal in early identification, assessment and management”

Pharmacological interventions

Ms Parker has been prescribed inhaled salbutamol as required; this is a SABA that mediates the increase of cyclic adenosine monophosphate in airway smooth-muscle cells, leading to muscle relaxation and bronchodilation. SABAs facilitate lung emptying by dilatating the small airways, reversing dynamic hyperinflation of the lungs (Thomas et al, 2013). Ms Parker also uses a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) inhaler, which works by blocking the bronchoconstrictor effects of acetylcholine on M3 muscarinic receptors in airway smooth muscle; release of acetylcholine by the parasympathetic nerves in the airways results in increased airway tone with reduced diameter.

At a routine review, Ms Parker admitted to only using the SABA and LAMA inhalers, despite also being prescribed a combined inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta 2 -agonist (ICS/LABA) inhaler. She was unaware that ICS/LABA inhalers are preferred over SABA inhalers, as they:

- Last for 12 hours;

- Improve the symptoms of breathlessness;

- Increase exercise tolerance;

- Can reduce the frequency of exacerbations (Agusti et al, 2010).

However, moderate-quality evidence shows that ICS/LABA combinations, particularly fluticasone, cause an increased risk of pneumonia (Suissa et al, 2013; Nannini et al, 2007). Inhaler choice should, therefore, be individualised, based on symptoms, delivery technique, patient education and compliance.

It is essential to teach and assess inhaler technique at every review (NICE, 2011). Ms Parker uses both a metered-dose inhaler and a dry-powder inhaler; an in-check device is used to assess her inspiratory effort, as different inhaler types require different inhalation speeds. Braido et al (2016) estimated that 50% of patients have poor inhaler technique, which may be due to health professionals lacking the confidence and capability to teach and assess their use.

Patients may also not have the dexterity, capacity to learn or vision required to use the inhaler. Online resources are available from, for example, RightBreathe (rightbreathe.com), British Lung Foundation (blf.org.uk). Ms Parker’s adherence could be improved through once-daily inhalers, as indicated by results from a study by Lipson et al (2017). Any change in her inhaler would be monitored as per local policy.

Vaccinations

Ms Parker keeps up to date with her seasonal influenza and pneumococcus vaccinations. This is in line with the low-cost, highest-benefit strategy identified by the British Thoracic Society and Primary Care Respiratory Society UK’s (2012) study, which was conducted to inform interventions for patients with COPD and their relative quality-adjusted life years. Influenza vaccinations have been shown to decrease the risk of lower respiratory tract infections and concurrent COPD exacerbations (Walters et al, 2017; Department of Health, 2011; Poole et al, 2006).

Self-management

Ms Parker was given a self-management plan that included:

- Information on how to monitor her symptoms;

- A rescue pack of antibiotics, steroids and salbutamol;

- A traffic-light system demonstrating when, and how, to commence treatment or seek medical help.

Self-management plans and rescue packs have been shown to reduce symptoms of an exacerbation (Baxter et al, 2016), allowing patients to be cared for in the community rather than in a hospital setting and increasing patient satisfaction (Fletcher and Dahl, 2013).

Improving Ms Parker’s adherence to once-daily inhalers and supporting her to self-manage and make the necessary lifestyle changes, should improve her symptoms and result in fewer exacerbations.

The earlier a diagnosis of COPD is made, the greater the chances of reducing lung damage through interventions such as smoking cessation, lifestyle modifications and treatment, if required (Price et al, 2011).

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a progressive respiratory condition, projected to become the third leading cause of death globally

- Diagnosis involves taking a patient history and performing spirometry testing

- Spirometry identifies airflow obstruction by measuring the volume of air that can be exhaled

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is managed with lifestyle and pharmacological interventions, as well as self-management

Related files

200506 diagnosis and management of copd – a case study.

- Add to Bookmarks

Related articles

Have your say.

Sign in or Register a new account to join the discussion.

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

A complex case study: coexistence of multi-drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis, HBV-related liver failure, and disseminated cryptococcal infection in an AIDS patient

- Wei Fu 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Zi Wei Deng 3 na1 ,

- Pei Wang 1 ,

- Zhen Wang Zhu 1 ,

- Zhi Bing Xie 1 ,

- Yong Zhong Li 1 &

- Hong Ying Yu 1

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 24 , Article number: 533 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

245 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can cause liver failure, while individuals with Acquired Immunodeficiency Virus Disease (AIDS) are highly susceptible to various opportunistic infections, which can occur concurrently. The treatment process is further complicated by the potential occurrence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), which presents significant challenges and contributes to elevated mortality rates.

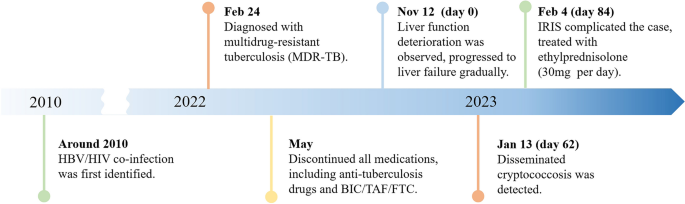

Case presentation

The 50-year-old male with a history of chronic hepatitis B and untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection presented to the hospital with a mild cough and expectoration, revealing multi-drug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis (MDR-PTB), which was confirmed by XpertMTB/RIF PCR testing and tuberculosis culture of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). The patient was treated with a regimen consisting of linezolid, moxifloxacin, cycloserine, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for tuberculosis, as well as a combination of bictegravir/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (BIC/TAF/FTC) for HBV and HIV viral suppression. After three months of treatment, the patient discontinued all medications, leading to hepatitis B virus reactivation and subsequent liver failure. During the subsequent treatment for AIDS, HBV, and drug-resistant tuberculosis, the patient developed disseminated cryptococcal disease. The patient’s condition worsened during treatment with liposomal amphotericin B and fluconazole, which was ultimately attributed to IRIS. Fortunately, the patient achieved successful recovery after appropriate management.

Enhancing medical compliance is crucial for AIDS patients, particularly those co-infected with HBV, to prevent HBV reactivation and subsequent liver failure. Furthermore, conducting a comprehensive assessment of potential infections in patients before resuming antiviral therapy is essential to prevent the occurrence of IRIS. Early intervention plays a pivotal role in improving survival rates.

Peer Review reports

HIV infection remains a significant global public health concern, with a cumulative death toll of 40 million individuals [ 1 ]. In 2021 alone, there were 650,000 deaths worldwide attributed to AIDS-related causes. As of the end of 2021, approximately 38 million individuals were living with HIV, and there were 1.5 million new HIV infections reported annually on a global scale [ 2 ]. Co-infection with HBV and HIV is prevalent due to their similar transmission routes, affecting around 8% of HIV-infected individuals worldwide who also have chronic HBV infection [ 3 ]. Compared to those with HBV infection alone, individuals co-infected with HIV/HBV exhibit higher HBV DNA levels and a greater risk of reactivation [ 4 ]. Opportunistic infections, such as Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, Toxoplasma encephalitis, cytomegalovirus retinitis, cryptococcal meningitis (CM), tuberculosis, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease, pneumococcal pneumonia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and central nervous system lymphoma, are commonly observed due to HIV-induced immunodeficiency [ 5 ]. Tuberculosis not only contributes to the overall mortality rate in HIV-infected individuals but also leads to a rise in the number of drug-resistant tuberculosis cases and transmission of drug-resistant strains. Disseminated cryptococcal infection is a severe opportunistic infection in AIDS patients [ 6 ], and compared to other opportunistic infections, there is a higher incidence of IRIS in patients with cryptococcal infection following antiviral and antifungal therapy [ 7 ]. This article presents a rare case of an HIV/HBV co-infected patient who presented with MDR-PTB and discontinued all medications during the initial treatment for HIV, HBV, and tuberculosis. During the subsequent re-anti-HBV/HIV treatment, the patient experienced two episodes of IRIS associated with cryptococcal infection. One episode was classified as “unmasking” IRIS, where previously subclinical cryptococcal infection became apparent with immune improvement. The other episode was categorized as “paradoxical” IRIS, characterized by the worsening of pre-existing cryptococcal infection despite immune restoration [ 8 ]. Fortunately, both episodes were effectively treated.

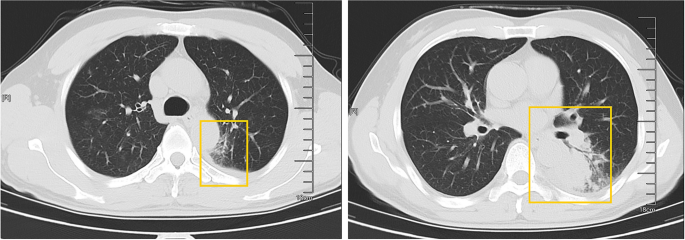

A 50-year-old male patient, who is self-employed, presented to our hospital in January 2022 with a chief complaint of a persistent cough for the past 2 months, without significant shortness of breath, palpitations, or fever. His medical history revealed a previous hepatitis B infection, which resulted in hepatic failure 10 years ago. Additionally, he was diagnosed with HIV infection. However, he ceased taking antiviral treatment with the medications provided free of charge by the Chinese government for a period of three years. During this hospital visit, his CD4 + T-cell count was found to be 26/μL (normal range: 500–1612/μL), HIV-1 RNA was 1.1 × 10 5 copies/ml, and HBV-DNA was negative. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed nodular and patchy lung lesions (Fig. 1 ). The BALF shows positive acid-fast staining. Further assessment of the BALF using XpertMTB/RIF PCR revealed resistance to rifampicin, and the tuberculosis drug susceptibility test of the BALF (liquid culture, medium MGIT 960) indicated resistance to rifampicin, isoniazid, and streptomycin. Considering the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for drug-resistant tuberculosis, the patient’s drug susceptibility results, and the co-infection of HIV and HBV, an individualized treatment plan was tailored for him. The treatment plan included BIC/TAF/FTC (50 mg/25 mg/200 mg per day) for HBV and HIV antiviral therapy, as well as linezolid (0.6 g/day), cycloserine (0.5 g/day), moxifloxacin (0.4 g/day), pyrazinamide (1.5 g/day), and ethambutol (0.75 g/day) for anti-tuberculosis treatment, along with supportive care.

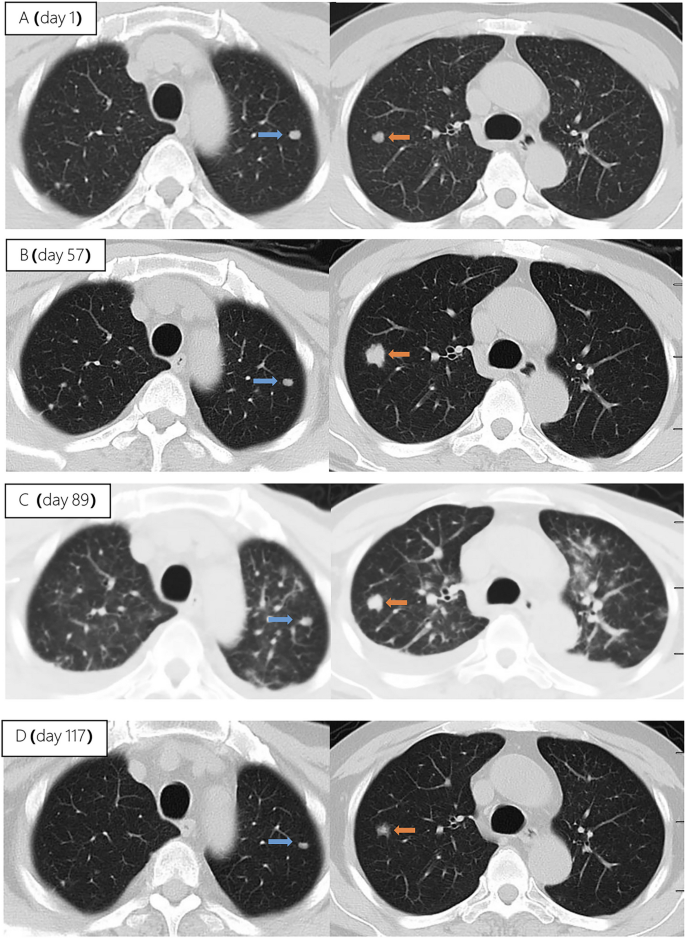

The patient’s pulmonary CT scan shows patchy and nodular lesions accompanied by a small amount of pleural effusion, later confirmed to be MDR-PTB

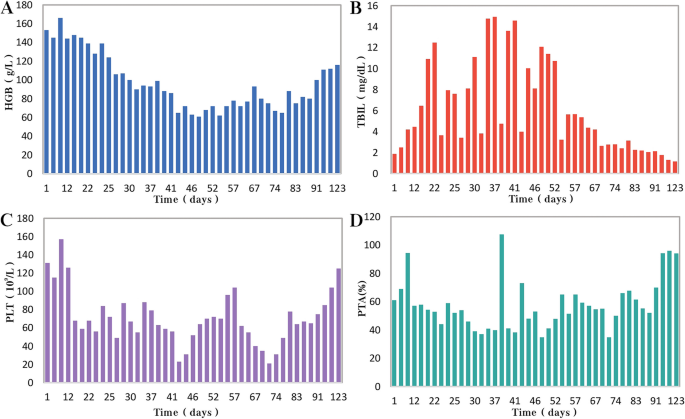

Unfortunately, after 3 months of follow-up, the patient discontinued all medications due to inaccessibility of the drugs. He returned to our hospital (Nov 12, 2022, day 0) after discontinuing medication for six months, with a complaint of poor appetite for the past 10 days. Elevated liver enzymes were observed, with an alanine aminotransferase level of 295 IU/L (normal range: 0–40 IU/L) and a total bilirubin(TBIL) level of 1.8 mg/dL (normal range: 0–1 mg/dL). His HBV viral load increased to 5.5 × 10 9 copies/ml. Considering the liver impairment, elevated HBV-DNA and the incomplete anti-tuberculosis treatment regimen (Fig. 2 A), we discontinued pyrazinamide and initiated treatment with linezolid, cycloserine, levofloxacin, and ethambutol for anti-tuberculosis therapy, along with BIC/TAF/FTC for HIV and HBV antiviral treatment. Additionally, enhanced liver protection and supportive management were provided, involving hepatoprotective effects of medications such as glutathione, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate, and bicyclol. However, the patient’s TBIL levels continued to rise progressively, reaching 4.4 mg/dL on day 10 (Fig. 3 B). Suspecting drug-related factors, we discontinued all anti-tuberculosis medications while maintaining BIC/TAF/FTC for antiviral therapy, the patient’s TBIL levels continued to rise persistently. We ruled out other viral hepatitis and found no significant evidence of obstructive lesions on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Starting from the day 19, due to the patient’s elevated TBIL levels of 12.5 mg/dL, a decrease in prothrombin activity (PTA) to 52% (Fig. 3 D), and the emergence of evident symptoms such as abdominal distension and poor appetite, we initiated aggressive treatment methods. Unfortunately, on day 38, his hemoglobin level dropped to 65 g/L (normal range: 120–170 g/L, Fig. 3 A), and his platelet count decreased to 23 × 10 9 /L (normal range: 125–300 × 10 9 /L, Fig. 3 C). Based on a score of 7 on the Naranjo Scale, it was highly suspected that “Linezolid” was the cause of these hematological abnormalities. Therefore, we had to discontinue Linezolid for the anti-tuberculosis treatment. Subsequently, on day 50, the patient developed recurrent fever, a follow-up chest CT scan revealed enlarged nodules in the lungs (Fig. 2 B). The patient also reported mild dizziness and a worsening cough. On day 61, the previous blood culture results reported the growth of Cryptococcus. A lumbar puncture was performed on the same day, and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure was measured at 130 mmH 2 O. India ink staining of the CSF showed typical encapsulated yeast cells suggestive of Cryptococcus. Other CSF results indicated mild leukocytosis and mildly elevated protein levels, while chloride and glucose levels were within normal limits. Subsequently, the patient received a fungal treatment regimen consisting of liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg·d −1 ) in combination with fluconazole(600 mg/d). After 5 days of antifungal therapy, the patient’s fever symptoms were well controlled. Despite experiencing bone marrow suppression, including thrombocytopenia and worsening anemia, during this period, proactive symptom management, such as the use of erythropoietin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and thrombopoietin, along with high-calorie dietary management, even reducing the dosage of liposomal amphotericin B to 2 mg/kg/day for 10 days at the peak of severity, successfully controlled the bone marrow suppression. However, within the following week, the patient experienced fever again, accompanied by a worsened cough, increased sputum production, and dyspnea. Nevertheless, the bilirubin levels did not show a significant increase. On day 78 the patient’s lung CT revealed patchy infiltrates and an increased amount of pleural effusion (Fig. 2 C). The CD4 + T-cell count was 89/μL (normal range: 500–700/μL), indicating a significant improvement in immune function compared to the previous stage, and C-reactive protein was significantly elevated, reflecting the inflammatory state, other inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and γ-IFN were also significantly elevated. On day 84, Considering the possibility of IRIS, the patient began taking methylprednisolone 30 mg once a day as part of an effort to control his excessive inflammation. Following the administration of methylprednisolone, the man experienced an immediate improvement in his fever. Additionally, symptoms such as cough, sputum production, dyspnea, and poor appetite gradually subsided over time. A follow-up lung CT showed significant improvement, indicating a positive response to the treatment. After 28 days of treatment with liposomal amphotericin B in combination with fluconazole, liposomal amphotericin B was discontinued, and the patient continued with fluconazole to consolidate the antifungal therapy for Cryptococcus. Considering the patient’s ongoing immunodeficiency, the dosage of methylprednisolone was gradually reduced by 4 mg every week. After improvement in liver function, the patient’s anti-tuberculosis treatment regimen was adjusted to include bedaquiline, contezolid, cycloserine, moxifloxacin, and ethambutol. The patient’s condition was well controlled, and a follow-up lung CT on day 117 indicated a significant improvement in lung lesions (Fig. 2 D).

Upon second hospitalization admission ( A ), nodular lesions were already present in the lungs, and their size gradually increased after the initiation of ART ( B , C ). Notably, the lung lesions became more pronounced following the commencement of anti-cryptococcal therapy, coinciding with the occurrence of pleural effusion ( C ). However, with the continuation of antifungal treatment and the addition of glucocorticoids, there was a significant absorption and reduction of both the pleural effusion and pulmonary nodules ( D )

During the patient's second hospitalization, as the anti-tuberculosis treatment progressed and liver failure developed, the patient’s HGB levels gradually decreased ( A ), while TBIL levels increased ( B ). Additionally, there was a gradual decrease in PLT count ( C ) and a reduction in prothrombin activity (PTA) ( D ), indicating impaired clotting function. Moreover, myelosuppression was observed during the anti-cryptococcal treatment ( C )

People living with HIV/AIDS are susceptible to various opportunistic infections, which pose the greatest threat to their survival [ 5 ]. Pulmonary tuberculosis and disseminated cryptococcosis remain opportunistic infections with high mortality rates among AIDS patients [ 9 , 10 ]. These infections occurring on the basis of liver failure not only increase diagnostic difficulty but also present challenges in treatment. Furthermore, as the patient’s immune function and liver function recover, the occurrence of IRIS seems inevitable.

HIV and HBV co-infected patients are at a higher risk of HBV reactivation following the discontinuation of antiviral drugs

In this case, the patient presented with both HIV and HBV infections. Although the HBV DNA test was negative upon admission. However, due to the patient’s self-discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HBV virologic and immunologic reactivation occurred six months later, leading to a rapid increase in viral load and subsequent hepatic failure. Charles Hannoun et al. also reported similar cases in 2001, where two HIV-infected patients with positive HBsAg experienced HBV reactivation and a rapid increase in HBV DNA levels after discontinuing antiretroviral and antiviral therapy, ultimately resulting in severe liver failure [ 11 ]. The European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) also emphasize that abrupt discontinuation of antiviral therapy in patients co-infected with HBV and HIV can trigger HBV reactivation, which, although rare, can potentially result in liver failure [ 12 ].

Diagnosing disseminated Cryptococcus becomes more challenging in AIDS patients with liver failure, and the selection of antifungal medications is significantly restricted

In HIV-infected individuals, cryptococcal disease typically manifests as subacute meningitis or meningoencephalitis, often accompanied by fever, headache, and neck stiffness. The onset of symptoms usually occurs approximately two weeks after infection, with typical signs and symptoms including meningeal signs such as neck stiffness and photophobia. Some patients may also experience encephalopathy symptoms like somnolence, mental changes, personality changes, and memory loss, which are often associated with increased intracranial pressure (ICP) [ 13 ]. The presentation of cryptococcal disease in this patient was atypical, as there were no prominent symptoms such as high fever or rigors, nor were there any signs of increased ICP such as somnolence, headache, or vomiting. The presence of pre-existing pulmonary tuberculosis further complicated the early diagnosis, potentially leading to the clinical oversight of recognizing the presence of cryptococcus. In addition to the diagnostic challenges, treating a patient with underlying liver disease, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and concurrent cryptococcal infection poses significant challenges. It requires considering both the hepatotoxicity of antifungal agents and potential drug interactions. EACS and global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis suggest that liposomal amphotericin B (3 mg/kg·d −1 ) in combination with flucytosine (100 mg/kg·d −1 ) or fluconazole (800 mg/d) is the preferred induction therapy for CM for 14 days [ 12 , 14 ]. Flucytosine has hepatotoxicity and myelosuppressive effects, and it is contraindicated in patients with severe liver dysfunction. The antiviral drug bictegravir is a substrate for hepatic metabolism by CYP3A and UGT1A1 enzymes [ 15 ], while fluconazole inhibits hepatic enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 [ 16 ]. Due to the patient's liver failure and bone marrow suppression, we reduced the dosage of liposomal amphotericin B and fluconazole during the induction period. Considering the hepatotoxicity of fluconazole and its interaction with bictegravir, we decreased the dosage of fluconazole to 600 mg/d, while extending the duration of induction therapy to 28 days.

During re-antiviral treatment, maintaining vigilance for the development of IRIS remains crucial

IRIS refers to a series of inflammatory diseases that occur in HIV-infected individuals after initiating ART. It is associated with the paradoxical worsening of pre-existing infections, which may have been previously diagnosed and treated or may have been subclinical but become apparent due to the host regaining the ability to mount an inflammatory response. Currently, there is no universally accepted definition of IRIS. However, the following conditions are generally considered necessary for diagnosing IRIS: worsening of a diagnosed or previously unrecognized pre-existing infection with immune improvement (referred to as “paradoxical” IRIS) or the unmasking of a previously subclinical infection (referred to as “unmasking” IRIS) [ 8 ]. It is estimated that 10% to 30% of HIV-infected individuals with CM will develop IRIS after initiating or restarting effective ART [ 7 , 17 ]. In the guidelines of the WHO and EACS, it is recommended to delay the initiation of antiviral treatment for patients with CM for a minimum of 4 weeks to reduce the incidence of IRIS. Since we accurately identified the presence of multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis in the patient during the early stage, we promptly initiated antiretroviral and anti-hepatitis B virus treatment during the second hospitalization. However, subsequent treatment revealed that the patient experienced at least two episodes of IRIS. The first episode was classified as “unmasking” IRIS, as supported by the enlargement of pulmonary nodules observed on the chest CT scan following the initiation of ART (Fig. 2 A). Considering the morphological changes of the nodules on the chest CT before antifungal therapy, the subsequent emergence of disseminated cryptococcal infection, and the subsequent reduction in the size of the lung nodules after antifungal treatment, although there is no definitive microbiological evidence, we believe that the initial enlargement of the lung nodules was caused by cryptococcal pneumonia. As ART treatment progressed, the patient experienced disseminated cryptococcosis involving the blood and central nervous system, representing the first episode. Following the initiation of antifungal therapy for cryptococcosis, the patient encountered a second episode characterized by fever and worsening pulmonary lesions. Given the upward trend in CD4 + T-cell count, we attributed this to the second episode of IRIS, the “paradoxical” type. The patient exhibited a prompt response to low-dose corticosteroids, further supporting our hypothesis. Additionally, the occurrence of cryptococcal IRIS in the lungs, rather than the central nervous system, is relatively uncommon among HIV patients [ 17 ].

Conclusions

From the initial case of AIDS combined with chronic hepatitis B, through the diagnosis and treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, the development of liver failure and disseminated cryptococcosis, and ultimately the concurrent occurrence of IRIS, the entire process was tortuous but ultimately resulted in a good outcome (Fig. 4 ). Treatment challenges arose due to drug interactions, myelosuppression, and the need to manage both infectious and inflammatory conditions. Despite these hurdles, a tailored treatment regimen involving antifungal and antiretroviral therapies, along with corticosteroids, led to significant clinical improvement. While CM is relatively common among immunocompromised individuals, especially those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [ 13 ], reports of disseminated cryptococcal infection on the background of AIDS complicated with liver failure are extremely rare, with a very high mortality rate.

A brief timeline of the patient's medical condition progression and evolution

Through managing this patient, we have also gained valuable insights. (1) Swift and accurate diagnosis, along with timely and effective treatment, can improve prognosis, reduce mortality, and lower disability rates. Whether it's the discovery and early intervention of liver failure, the identification and treatment of disseminated cryptococcosis, or the detection and management of IRIS, all these interventions are crucially timely. They are essential for the successful treatment of such complex and critically ill patients.

(2) Patients who exhibit significant drug reactions, reducing the dosage of relevant medications and prolonging the treatment duration can improve treatment success rates with fewer side effects. In this case, the dosages of liposomal amphotericin B and fluconazole are lower than the recommended dosages by the World Health Organization and EACS guidelines. Fortunately, after 28 days of induction therapy, repeat CSF cultures showed negative results for Cryptococcus, and the improvement of related symptoms also indicates that the patient has achieved satisfactory treatment outcomes. (3) When cryptococcal infection in the bloodstream or lungs is detected, prompt lumbar puncture should be performed to screen for central nervous system cryptococcal infection. Despite the absence of neurological symptoms, the presence of Cryptococcus neoformans in the cerebrospinal fluid detected through lumbar puncture suggests the possibility of subclinical or latent CM, especially in late-stage HIV-infected patients.

We also encountered several challenges and identified certain issues that deserve attention. Limitations: (1) The withdrawal of antiviral drugs is a critical factor in the occurrence and progression of subsequent diseases in patients. Improved medical education is needed to raise awareness and prevent catastrophic consequences. (2) Prior to re-initiating antiviral therapy, a thorough evaluation of possible infections in the patient is necessary. Caution should be exercised, particularly in the case of diseases prone to IRIS, such as cryptococcal infection. (3) There is limited evidence on the use of reduced fluconazole dosage (600 mg daily) during antifungal therapy, and the potential interactions between daily fluconazole (600 mg) and the antiviral drug bictegravir and other tuberculosis medications have not been extensively studied. (4) Further observation is needed to assess the impact of early-stage limitations in the selection of anti-tuberculosis drugs on the treatment outcome of tuberculosis in this patient, considering the presence of liver failure.

In conclusion, managing opportunistic infections in HIV patients remains a complex and challenging task, particularly when multiple opportunistic infections are compounded by underlying liver failure. Further research efforts are needed in this area.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Hepatitis B virus

Acquired immunodeficiency virus disease

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

Human immunodeficiency virus

Multi-drug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

Bictegravir/tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine

Cryptococcal meningitis

World Health Organization

Computed tomography

Total bilirubin

Cerebrospinal fluid

European AIDS Clinical Society

Intracranial pressure

Antiretroviral therapy

Prothrombin activity

Bekker L-G, Beyrer C, Mgodi N, Lewin SR, Delany-Moretlwe S, Taiwo B, et al. HIV infection. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2023;9:1–21.

Google Scholar

Data on the size of the HIV epidemic. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/data-on-the-size-of-the-hiv-aids-epidemic?lang=en . Accessed 3 May 2023.

Leumi S, Bigna JJ, Amougou MA, Ngouo A, Nyaga UF, Noubiap JJ. Global burden of hepatitis B infection in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020;71:2799–806.

Article Google Scholar