Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

What federal education data shows about students with disabilities in the u.s..

Public K-12 schools in the United States educate about 7.3 million students with disabilities – a number that has grown over the last few decades. Disabled students ages 3 to 21 are served under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) , which guarantees them the right to free public education and appropriate special education services.

For Disability Pride Month , here are some key facts about public school students with disabilities, based on the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) .

July is both Disability Pride Month and the anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act. To mark these occasions, Pew Research Center used federal education data from the National Center for Education Statistics to learn more about students who receive special education services in U.S. public schools.

In this analysis, students with disabilities include those ages 3 to 21 who are served under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) . Through IDEA, children with disabilities are guaranteed a “free appropriate public education,” including special education and related services.

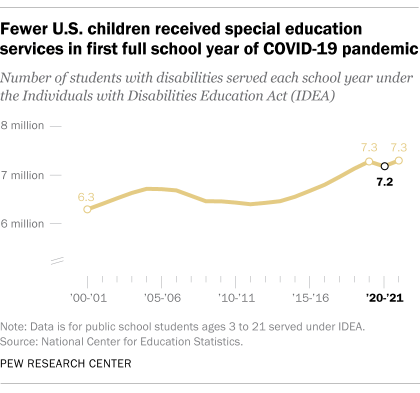

The 7.3 million disabled students in the U.S. made up 15% of national public school enrollment during the 2021-22 school year. The population of students in prekindergarten through 12th grade who are served under IDEA has grown in both number and share over the last few decades. During the 2010-11 school year, for instance, there were 6.4 million students with disabilities in U.S. public schools, accounting for 13% of enrollment.

The number of students receiving special education services temporarily dropped during the coronavirus pandemic – the first decline in a decade. Between the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years, the number of students receiving special education services decreased by 1%, from 7.3 million to 7.2 million. This was the first year-over-year drop in special education enrollment since 2011-12.

The decline in students receiving special education services was part of a 3% decline in the overall number of students enrolled in public schools between 2019-20 and 2020-21. While special education enrollment bounced back to pre-pandemic levels in the 2021-22 school year, overall public school enrollment remained flat.

These enrollment trends may reflect some of the learning difficulties and health concerns students with disabilities and their families faced during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic , which limited or paused special education services in many school districts.

Many school districts struggle to hire special education professionals. During the 2020-21 school year, 40% of public schools that had a special education teaching vacancy reported that they either found it very difficult to fill the position or were not able to do so.

Foreign languages (43%) and physical sciences (37%) were the only subjects with similarly large shares of hard-to-fill teaching vacancies at public schools that were looking to hire in those fields.

While the COVID-19 pandemic called attention to a nationwide teacher shortage , special education positions have long been among the most difficult for school districts to fill .

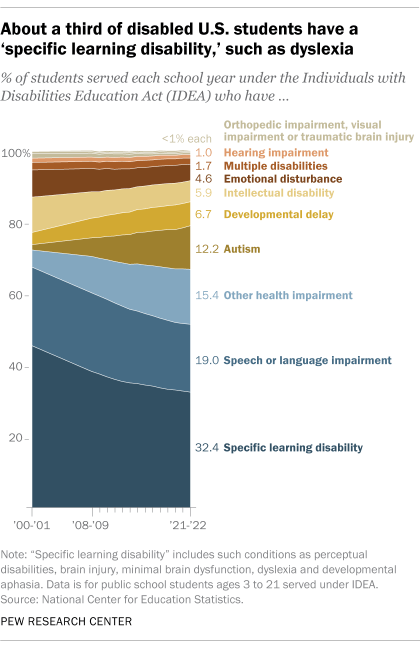

The most common type of disability for students in prekindergarten through 12th grade involves “specific learning disabilities,” such as dyslexia. In 2021-22, about a third of students (32%) receiving services under IDEA had a specific learning disability. Some 19% had a speech or language impairment, while 15% had a chronic or acute health problem that adversely affected their educational performance. Chronic or acute health problems include ailments such as heart conditions, asthma, sickle cell anemia, epilepsy, leukemia and diabetes.

Students with autism made up 12% of the nation’s schoolchildren with disabilities in 2021-22, compared with 1.5% in 2000-01. During those two decades, the share of disabled students with a specific learning disability, such as dyslexia, declined from 45% to 32%.

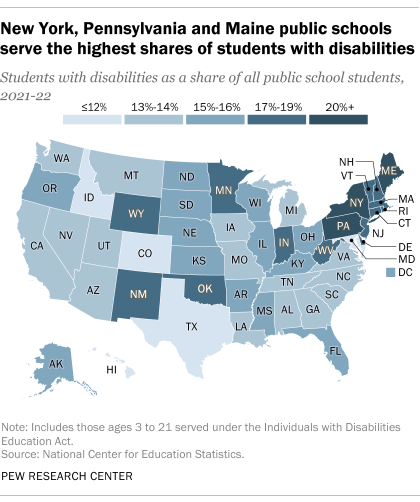

The percentage of students receiving special education services varies widely across states. New York serves the largest share of disabled students in the country at 20.5% of its overall public school enrollment. Pennsylvania (20.2%), Maine (20.1%) and Massachusetts (19.3%) serve the next-largest shares. The states serving the lowest shares of disabled students include Texas and Idaho (both 11.7%) and Hawaii (11.3%).

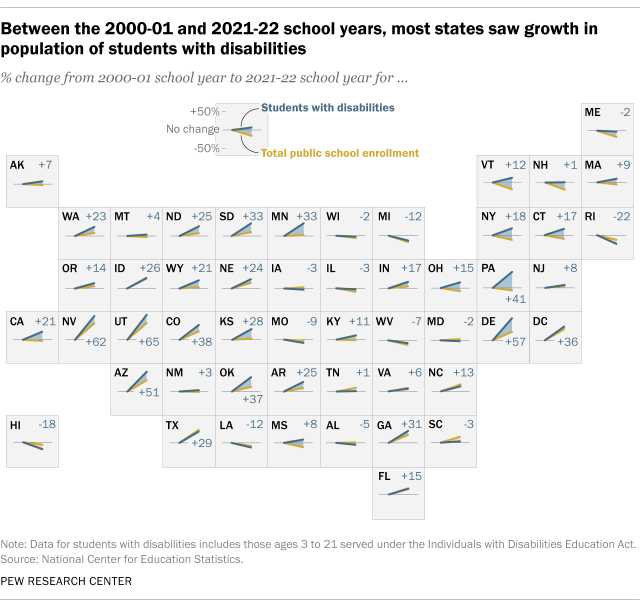

Between the 2000-01 and 2021-22 school years, all but 12 states experienced growth in their disabled student populations. The biggest increase occurred in Utah, where the disabled student population rose by 65%. Rhode Island saw the largest decline of 22%.

These differences by state are likely the result of inconsistencies in how states determine which students are eligible for special education services and challenges in identifying disabled children.

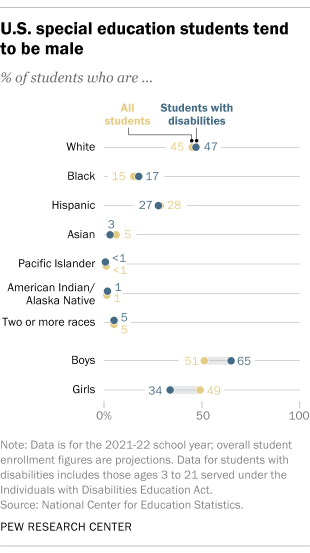

The racial and ethnic makeup of the nation’s special education students is similar to public school students overall, but there are differences by sex. About two-thirds of disabled students (65%) are male, while 34% are female, according to data from the 2021-22 school year. Overall student enrollment is about evenly split between boys and girls.

Research has shown that decisions about whether to recommend a student for special education may be influenced by their school’s socioeconomic makeup, as well as by the school’s test scores and other academic markers.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published April 23, 2020.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Race and LGBTQ Issues in K-12 Schools

From businesses and banks to colleges and churches: americans’ views of u.s. institutions, fewer young men are in college, especially at 4-year schools, 9 facts about bullying in the u.s., about 1 in 5 u.s. teens who’ve heard of chatgpt have used it for schoolwork, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Special Education: Definition, Statistics, and Trends

- Share article

Corrected : An earlier version of this story misnamed the federal law governing special education. The correct name is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

Definition of special education

Special education encompasses the programs which serve students with mental, physical, emotional, and behavioral disabilities. The major law governing special education is the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which guarantees a “free appropriate public education” to children with disabilities and mandates that, to the “maximum extent appropriate,” they be educated with their nondisabled peers in the “least restrictive environment.” Read more .

What is an IEP?

An Individualized Education Program, or IEP, is a program tailored to meet the individual needs of students with disabilities. The program is written in collaboration with a child’s school district, their parent or guardian, and sometimes, the student. The document outlines the special educational needs based on the student’s identified disability. Read more .

How many students are in special education?

In the U.S. overall, 14.7 percent of all students were special education students (ages 3-21) in 2021-22. The percentage varied by state from 11.3 percent in Hawaii to 20.5 percent in New York.

Share of special education students by state

See the percent of special education students by state in the map below:

Has the number of students served in special education increased?

Yes. In the past decade , the number of students with disabilities has grown from 6.4 million, or 12.9 percent of all students in 2011-12, to almost 7.3 million, or 14.7 percent in 2021-22.

Special education statistics by race

While overall, 14.7 percent of public school students were served by IDEA in 2020-21 , that number varies by race and ethnicity.

Are schools overidentifying minority students with disabilities?

Federal law requires that states monitor their districts for overidentifying students with disabilities. Several studies have found that minority students are actually being under identified for disabilities .

But some new studies are uncovering more nuanced findings, suggesting that minority students are overidentified in some contexts and underidentified in others. Read more .

What are the demographics of special education teachers?

Although research has shown that students often do better in school when they have a teacher of the same race, just over 81.8 percent of special education high school teachers in public schools are white, higher than the teaching population as a whole, according to the most recent data available . But under half of all students receiving special education services are white, according to 2021 -2 2 data .

Read more about efforts to prepare, recruit, and retain special education teachers of color.

Inclusion statistics

A majority of special education students—66.5 percent of those ages 6-21 and 5-year-olds in kindergarten—spend 80 percent or more of their time in regular education classes, according to 2021 data . That number has more than doubled in recent decades. In 1989, only 31.7 percent of students ages 6-21 spent 80 percent or more of their time in regular classes.

Getting students with disabilities into general education classrooms is not a silver bullet, researchers say. Read more to learn what else needs to happen to raise academic outcomes for students with disabilities.

Learning disabilities statistics

The specific learning disabilities category is the most common one covered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act—in 2021-22 , 32.4 percent of students with disabilities had specific learning disabilities.

Autism statistics

12.2 percent of all students with disabilities have been diagnosed with autism alone, according to 2021-22 data.

Which disability categories have grown the most?

In the past decade, the number of students with disabilities as a percentage of total enrollment has increased a small amount, from 12.9 percent in 2011-12 to 14.7 percent in 2021-22 . The mix of disabilities those students have, however, has changed dramatically.

The percent of students with disabilities who had a specific learning disability, like dyslexia, decreased from 36 percent in 2011-12 to 32.4 percent in 2021-22. And the percent of students with disabilities with autism grew from 7.1 percent to 12.2 percent over the same period.

How much money is spent on special education by the federal government?

In fiscal year 2018, the federal government earmarked $12.3 billion for the education of children ages 3-12 with disabilities. That’s only about 15 percent of the excess cost of educating students with disabilities, compared with the cost of educating a general education student. The federal government under the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act set a goal to pay states up to 40 percent of the excess cost. It never reached that goal.

For more on special education funding, read this explainer .

What is the student-teacher ratio for special education students?

In 2016, there were 17.1 special education students for each special education teacher in the United States. That’s higher than the overall student-teacher ratio of 16.2 students per teacher.

From 2006 to 2016, the number of special education teachers decreased by 17 percent, while the number of special education students only dropped by 1 percent. Read more about how that plays out on the school level.

For more information on special education, check out our Special Education topics page .

How to Cite This Article Riser-Kositsky, M. (2019, December 17). Special Education: Definition, Statistics, and Trends. Education Week. Retrieved Month Day, Year from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/special-education-definition-statistics-and-trends/2019/12

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

How included are students with disabilities in your local schools?

Advocates want all children to feel included in their communities. In a school setting, this usually means having students with disabilities spend as much time as possible in regular classrooms (with, importantly, any needed supports). Research shows that, in general, disabled students make much more progress when surrounded by their typically developing peers. Typical peers also benefit from the inclusive environment, as accommodations like universal design end up benefitting many, as well as giving them confidence that, in a supportive community, their own unique needs will be met. Additionally, inclusive environments can help reduce stigma and discrimination.

This tool allows you to explore the most recent data on inclusion and outcomes for children with IEPs from school districts around your state. To begin, enter the name of a district below, or select one or more on the map.

Find a school district

The inclusion score is calculated based on reported rates of how much time students with disabilities spend in regular classrooms, compared to the other districts in the state.

Small districts have less than 500 students with IEPs. Large districts have 500 or more.

Data is from the 2021-22 school year (unless otherwise noted) and comes from the Oregon Department of Education . Geography data comes from the US Census .

California college savings accounts aren’t getting to all the kids who need them

How improv theater class can help kids heal from trauma

50 years later: How Lau v. Nichols changed education for English learners

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

School choice advocate, CTA opponent Lance Christensen would be a very different state superintendent

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

March 21, 2024

Raising the curtain on Prop 28: Can arts education help transform California schools?

February 27, 2024

Keeping options open: Why most students aren’t eligible to apply to California’s public universities

Teacher Voices

Now is the time for schools to invest in special-education inclusion models that benefit all students

Kimberly Berry

November 10, 2021.

Ivan was a fourth grader with big brown eyes, a wide smile and a quiet demeanor who refused to enter my classroom. “Everyone thinks I’m stupid,” he’d say. I’ve changed his name to protect his privacy.

At the time, my school employed a pull-out model for students with disabilities, meaning they were removed from their assigned classrooms to receive specialized services and supports. This left Ivan feeling embarrassed, ostracized and resistant to putting forth academic effort.

One in 8 students in U.S. public schools have an individualized education plan, or IEP, making them eligible for special education services. About 750,000 students with disabilities attend California public schools. Many, like Ivan, do not respond well to being substantially separated from their peers. Research suggests that inclusion models designed to integrate students with and without disabilities into a single learning environment can lead to stronger academic and social outcomes.

At Caliber ChangeMakers Academy — where I have been a program specialist for five of the 10 years I have worked with students with disabilities — we knew an inclusion model was best for Ivan and many others. Yet, we didn’t think we had the tools or resources to make it possible.

We were wrong.

Schools can support students like Ivan — and those of all abilities — to learn from and alongside one another in an inclusive setting without exorbitant costs if they rethink how they allocate resources and develop educators’ confidence and competence in teaching all students in a general education setting.

In 2019, we began intentionally organizing staff, time and money toward inclusion, and we did so without spending more than similar public schools do that don’t focus on inclusion.

Now, with the infusion of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding, schools have additional resources to invest in this approach now, in service to longer-term, sustainable change.

The nonprofit Education Resource Strategies studied our school and three others in California that are doing this work without larger investments of resources. Their analysis examines the resource shifts that inclusion-focused schools employ and can be tapped by other schools considering this work, taking a “do now, build toward” approach that addresses student needs and sustains these changes even after the emergency federal funding expires. Many of their recommendations mirror the steps we took to pursue an inclusion model.

It didn’t happen overnight, but three steps were important to our efforts to adopt a more inclusive model for teaching and learning:

- Shift special education staff into general education classrooms to support targeted group sizes. At Caliber ChangeMakers Academy, special education teachers are departmentalized, each serving as a co-teacher to two general education teachers, leveraging their content expertise to share responsibility for classroom instruction. That means some special education teachers now teach students who are not part of their caseload. That means they are tracking the goals of more students, which also means that young people have more specialty educators working together to support their individual needs.

- Prioritize connected professional learning around inclusion for all teachers . We adjusted teachers’ schedules to incorporate collaborative time for general education and special education teachers to meet before, during and after lessons to plan engaging, differentiated instruction for all. On the surface, the reduction in individual planning time might be a challenge. However, our teachers have found that they now feel more prepared, effective and connected because they have a partner to turn to for feedback, suggestions and encouragement.

- Invest in social-emotional and mental health staff to narrow the scope of special education teachers. These staff members work to reduce unnecessary special education referrals and mitigate troubles facing students regardless of their disability status. They also can help address unexpected challenges, meaning special education teachers can spend more time in general education classrooms. A tradeoff we made is to slightly increase class sizes with fewer general administrative and support staff to prioritize hiring experienced social-emotional learning and mental health professionals.

For schools eager to adopt a more inclusive instructional model, now is the time. The emergency federal funding creates unprecedented opportunities for school and system leaders to build research-backed, sustainable inclusion models that can better meet the needs of all students, including students with disabilities.

I’ve seen firsthand that inclusive, diverse classrooms can provide powerful learning opportunities for all students.

As for Ivan, he’s now in eighth grade and thriving in an inclusive, co-teaching classroom. He went from completing almost no academic work independently to completing science lab reports on his own, working in collaborative groups in his English class and declaring that he loves math. Because our school invested in and normalized differentiated supports in an inclusive setting, now Ivan and many other students are getting what they need to be successful academically, socially and emotionally.

Kimberly Berry is a special education program specialist at Caliber ChangeMakers Academy in Vallejo.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Share Article

Comments (3)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Karina Villalona 2 years ago 2 years ago

I speak as a mom of two kids in co-teaching collaborative classes for their 4 main academic subjects, as well as a former teacher, and a school psychologist for 19 years. I agree with much of what Ms. Berry states. Co-teaching programs can be very successful for both general and special education students if all of the appropriate supports are in place (as listed by Ms. Berry). However, it is important to clarify that this … Read More

I speak as a mom of two kids in co-teaching collaborative classes for their 4 main academic subjects, as well as a former teacher, and a school psychologist for 19 years. I agree with much of what Ms. Berry states. Co-teaching programs can be very successful for both general and special education students if all of the appropriate supports are in place (as listed by Ms. Berry).

However, it is important to clarify that this model is not a panacea. Students with cognitive skills that are far below the average range have also shared how incredibly frustrating being in co-teaching classes can be for them. Even with support from the special education teacher, the pacing for some students is way too fast. In addition, depending on what the student’s specific classification is, co-teaching on its own does not allow an opportunity for remedial instruction.

My daughters are dyslexic. They participate in co-teaching with a lot of support from the special education teacher. They have one period of direct instruction in reading via an Orton-Gillingham based program and one period of Resource Room daily which allows them to work on content from the general education classes that they might need to review, break down or preview.

So, yes, co-teaching can be great for some students when the program is well managed and staffed; however, we cannot ignore the need for small group supports and remedial instruction when necessary.

Craig 2 years ago 2 years ago

Studies cited showing benefits of inclusion model typically suffer from selection bias, and there are no significant data on the effects of inclusion models on neurotypical peers. Does the author of this piece have data showing results that support her claims? Also, what do the teachers in this program have to say about it, in the first person? If this is truly working as presented it will be a game changer.

Monica Saraiya 2 years ago 2 years ago

The inclusion model is not a one size fits all one. Students with significant learning differences do not receive the services that best meet their needs in this model. As with all practices in education, inclusion must be one, but not the only way to service students who need specialized help with their learning.

EdSource Special Reports

Bias, extra work and feelings of isolation: 5 Black teachers tell their stories

Five Black teachers talk about what they face each day in California classrooms, and what needs to change to recruit and retain more Black teachers.

Bills address sexual harassment in California public colleges

Proposals follow a report detailing deficiencies in how the UC, CSU and California community college systems handle complaints.

Research shows having a Black teacher in the classroom has a positive impact on students, but the number of Black teachers is declining.

Disrespect, low pay, lack of support keep Black teachers out of the profession

The cost of earning a credential and the disrespect they face while teaching are keeping Black teachers out of the classroom.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

PROOF POINTS: New research review questions the evidence for special education inclusion

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

For the past 25 years, U.S. policy has urged schools to keep students with disabilities in the same classrooms with their general education peers unless severe disabilities prevent it. It seems a humane policy not to wall off those with disabilities and keep them apart from society. Who would argue against it?

Schools have embraced inclusion. According to the most recent data from 2020-21 school year, two thirds of the 7 million students with disabilities who receive special education services spent 80 percent or more of their time in traditional classrooms. Separation is less common today; only one out of every eight students with disabilities was taught separately in a special-needs only environment most of the time.

But a recent international analysis of all the available research on special education inclusion found inconsistent results. Some children thrived while others did very badly in regular classrooms. Overall, students didn’t benefit academically, psychologically or socially from the practice. Math and reading scores, along with psychosocial measures, were no higher for children with disabilities who learned in general education classrooms, on average, compared to children who learned in separate special education classrooms.

“I was surprised,”said Nina Dalgaard, lead author of the inclusion study for the Campbell Collaboration , a nonprofit organization that reviews research evidence for public policy purposes. “Despite a rather large evidence base, it doesn’t appear that inclusion automatically has positive effects. To the contrary, for some children, it appears that being taught in a segregated setting is actually beneficial.”

Many disability advocates balked at the findings, published in December 2022, on social media. An influential lobbying organization, the National Center for Learning Disabilities, said it continues to believe that inclusion is beneficial for students and that this study will “not change” how the disability community advocates for students.

“Students with disabilities have a right to learn alongside their peers, and studies have shown that this is beneficial not only for students with disabilities but also for other students in the classroom,” said Lindsay Kubatzky, the organization’s director of policy and advocacy. “Every student is different, and ‘inclusion’ for one student may look different from others. For some, it could be a classroom separate from their peers, but that is rarely the case.”

The Campbell Collaboration study is a meta-analysis, which means it is supposed to sweep up all the best research on a topic and use statistics to tell us where the preponderance of the evidence lies. Dalgaard, a senior researcher at VIVE—The Danish Centre for Social Science Research, initially found over 2,000 studies on special education inclusion. But she threw out 99 percent of them, many of which were quite favorable to inclusion. Most were qualitative studies that described students’ experiences in an inclusion classroom but didn’t rigorously track academic progress. Among those that did monitor math or reading, many simply noted how much students improved in an inclusive setting, but didn’t compare those gains with how students might have otherwise fared in a separate special-needs-only setting.

Fewer than 100 studies had comparison groups, but still most of those didn’t make the cut because the students in inclusive settings were vastly different from those in separate settings. Special education is a particularly difficult area to study because researchers cannot randomly assign students with disabilities to different treatments. Schools tend to keep children with milder disabilities in a regular classroom and teach only those with the most severe disabilities separately. In comparing how both groups fare, it should be no surprise that students with milder disabilities outperform those with more severe disabilities. But that’s not good evidence that inclusion is better. “It’s a serious, confounding bias,” Dalgaard said.

In the end, Dalgaard was left with only 15 studies where the severity of the disability was somehow noted so that she could compare apples to apples. These 15 studies covered more than 7,000 students, ages six through 16, across nine countries. Four of the studies were conducted in the United States with the others in Europe.

The disabilities in the studies ranged widely, from the most common ones, such as dyslexia, ADHD, speech impairments and autism, to rarer ones, such as Down syndrome and cerebral palsy. Some students had mild versions; others had more severe forms. I asked Dalgaard if she found clues in the results as to which disabilities were more conducive to inclusion. I was curious if children with severe dyslexia, for example, might benefit from separate instruction with specially trained reading teachers for the first couple of years after diagnosis.

Dalgaard said there wasn’t enough statistical evidence to untangle when inclusion is most beneficial. But she did notice in the underlying studies that students with autism seem to be better off in a separate setting. For example, their psychosocial scores were higher. But more studies would be needed to confirm this.

She also noticed that how a school goes about including students with disabilities mattered. In schools that used a co-teaching model, one regular teacher and one trained in special education, students fared better in inclusion classrooms. Again, more research is needed to confirm this statistically. And, even if co-teaching proves to be effective over multiple studies, not every school can afford to hire two teachers for every classroom. It’s particularly cost-prohibitive in middle and high school as teachers specialize in subjects.

Instead, Dalgaard noted that inclusion is often a cost-cutting practice because schools save money when they no longer run separate classrooms or schools for children with disabilities. “In some cases, children with disabilities no longer had access to the same resources. It’s not supposed to happen this way, but it does in some places,” said Dalgaard. “That is probably why the results of the meta-analysis show that some children actually learn more in segregated settings.”

I was surprised to learn from Dalgaard that no sound meta-analysis has found “clear” benefits for special education inclusion. Indeed, previous meta-analyses have found exactly the same inconsistent or very small positive results, she said. This latest Campbell Collaboration study was commissioned to see if newer research, published from 2000 to September 2021, would move the dial. It did not.

As a nation, we spend an estimated $90 billion a year in federal, state and local taxpayer funds on educating children with disabilities. We ought to know more about how to best help them learn.

This story about special education inclusion was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Jill Barshay SENIOR REPORTER

(212)... More by Jill Barshay

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

re: https://hechingerreport.org/proof-ponts-new-research-review-questions-the-evidence-for-special-education-inclusion/ Ref: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cl2.1291 The effects of inclusion on academic achievement, socioemotional development and wellbeing of children with special educational needs

Jill Barshay, Hechinger Reports cc Dr. Nina Dalgaard

It is important to conduct periodic meta-analysis of topics related to public policy, funding and other aspects of education.

I disagree with the reporting by Jill Bashay regarding special education learner inclusion/exclusion.

The reason for my disagreement is that the referenced study authors report contains the authors’ data collection and meta-analysis conclusions (see below) that valid information for meta-analysis is inadequate. My read of the Dalgaard met-analysis report suggests that the two extremes – full inclusion or full exclusion – of SEN students in the ‘normal’ population may be harmful but is really unknown. Therefore, until more and better research is achieved, some logical blend of inclusion/exclusion can be designed and implemented to achieve learning and social integration objectives. My opinion comes from leading manufacturing ventures that have intentionally accommodated “SEN” adults successfully in ways that give them personal work settings along with collaborative opportunities. The emotional intelligence for diversity, equity and inclusion is, I believe, better achieved by starting in the K-12 system.

Larry Gebhardt Ph.D., Captain US Navy (Retired) Pocatello, Idaho

Data Collection and Analysis The total number of potentially relevant studies constituted 20,183 hits. A total of 94 studies met the inclusion criteria, all were non-randomised studies. The 94 studies analysed data from 19 different countries. Only 15 studies could be used in the data synthesis. Seventy-nine studies could not be used in the data synthesis as they were judged to be of critical risk of bias and, in accordance with the protocol, were excluded from the meta-analysis on the basis that they would be more likely to mislead than inform. The 15 studies came from nine different countries. Separate meta-analyses were conducted on conceptually distinct outcomes. All analyses were inverse variance weighted using random effects statistical models. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of pooled effect sizes across components of risk of bias.

Authors’ Conclusions The overall methodological quality of the included studies was low, and no experimental studies in which children were randomly assigned to intervention and control conditions were found. The 15 studies, which could be used in the data synthesis, were all, except for one, judged to be in serious risk of bias. Results of the meta-analyses do not suggest on average any sizeable positive or negative effects of inclusion on children’s academic achievement as measured by language, literacy, and math outcomes or on the overall psychosocial adjustment of children. The average point estimates favoured inclusion, though small and not statistically significant, heterogeneity was present in all analyses, and there was inconsistency in direction and magnitude of the effect sizes. This finding is similar to the results of previous meta-analyses, which include studies published before 2000, and thus although the number of studies in the current meta-analyses is limited, it can be concluded that it is very unlikely that inclusion in general increases or decreases learning and psychosocial adjustment in children with special needs. Future research should explore the effects of different kinds of inclusive education for children with different kinds of special needs, to expand the knowledge base on what works for whom.

Of course inclusion, just in general, doesn’t increase outcomes. Just like exclusion, just in general, doesn’t help anyone. So many other things have to be true. What the kids and adults are actually doing when they are being ‘included,’ matters the most. Is there one general education teacher with 25 kids and kids with disabilities are just in class receiving whole group instruction without any targeted supports? Is there a strong co-teaching model led by two content experts with most time spent in small groups? Is the special educator a content expert? If you think about what is true about a self-contained classroom that would, arguably, be better for a student, those things can be replicated within a general education setting. As a school leader, professor, former self-contained, and inclusion teacher, there is no arguing with the notion that a non-verbal student with autism is NOT categorically better off in an autism classroom than in an inclusion classroom with strong language models. The structure of the classroom and the roles of adults have to be strategically designed so that kids benefit from any classroom structure, inclusion or otherwise. I have trained hundreds of school leaders all across the country and have learned that most schools don’t know how to do inclusion well. Let’s talk about that.

I am in total agreement with Tony Barton’s comment. Jill Barshay’s article reinforced what we know: that the right set-up plays a critical role in the outcome. Therefore, since there are so few properly conducted studies, we must focus our attention to ensure that our students with disabilities are all in settings that are conducive to progress in all domains- academically, psychologically and socially. Ensuring all our educators are properly trained is the first step. I have also found that I will create the learning environment for each struggling student based on the current conditions – and include each student’s personality traits as part of the assessment done to determine where the student will truly feel best and progress most. This is similar to a general statement regarding pain. One can never compare his pain to another since pain is physiological and cannot be measured via comparison. Since the personality and individual abilities of the student, teacher, assistant and special educator all will impact the student’s outcome- it is hard to measure and determine where success is most feasible without being aware of all variables. I agree that most schools don’t know how to do inclusion well- or don’t have the staff to properly support it. This article is great in raising our collective awareness of why the Campbell Study couldn’t be more targeted and concise with its results and what we can do to support our students best.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Submit a letter

For some students with disabilities, full inclusion may not be the answer

Media inquiries.

- 615-322-6397 Email

Latest Stories

- Israeli ambassador to U.S., former Palestinian Authority prime minister visit Vanderbilt classroom

- Campus Dining celebrates Earth Month

- Faculty Senate Meeting is Thursday, April 4

Sep 16, 2022, 12:48 PM

By Jane Sevier

Proponents of full inclusion—placing students with disabilities in general classrooms for most of the school day—maintain that the more time those students spend in such classes, the better they do academically. A new paper by Vanderbilt Peabody College of education and human development researchers challenges that assumption.

Research Professor of Special Education Douglas Fuchs and his team reviewed two kinds of evidence used to support fully including students with disabilities. They examined research on programs developed for students in mainstream settings. When properly applied, they found these programs benefitted many—but not all—special-needs children. Specifically, these programs strengthened expressive language, improved peer interactions, increased task engagement and encouraged more normative school behavior for many students with disabilities. However, the researchers also found that students with more serious learning and behavior problems required an intensity of intervention not offered in many class-wide programs. The authors also described studies by others that explored the importance of general class placement regardless of the use of evidence-based interventions—a dosage (in this case, more-time-is-better) hypothesis.

Reporting their findings in “Exploring the Truth of Michael Yudin’s Claim: The More Time Students with Disabilities Spend in General Classrooms, the Better They Do Academically” ( Journal of Disability Policy Studies , 2022), the researchers found that as the number of students with disabilities placed in general classrooms increased, the gap between their reading proficiency and their grade level increased, as well.

Michael Yudin, a former assistant secretary for special education and rehabilitative services in the U.S. Department of Education, was widely known during the Obama administration as a champion of full inclusion. Students with disabilities will prosper in mainstream settings, he argued, because general educators are more likely to hold them to higher standards and to ensure that they access the same curriculum as their peers. There will, therefore, be less need for special education placements.

Fuchs and his team tracked U.S. Office of Special Education Program placement data and National Center for Education Statistics reading data for the years 1998 through 2015. The goal was to describe trends across time for these data. The students’ reading performance on the National Assessment of Educational Progress did not track with the increasing amount of time they were spending in regular classrooms. (The congressionally mandated NAEP provides important information about student achievement and learning experiences in various subjects.) The researchers found little evidence that placing students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms strengthens their academic achievement.

For perspective on their findings, the authors also considered a randomized trial that examined intensive instruction in math fractions from a trained tutor outside the general classroom compared to instruction within it. That trial found that students with disabilities who received the intensive instruction outperformed those taught in the mainstream group.

While Fuchs and his colleagues note that there is no single solution to educating all students with disabilities, they argue that intensive instruction benefits many students with disabilities in ways not supported in general classrooms.

Keep Reading

‘U.S. News’ graduate school rankings: Here is how Vanderbilt graduate and professional programs placed

Peabody College researcher awarded more than $9.9 million to support students with disabilities, visual impairments

New Faculty: Meghan Burke, family advocacy and disabilities policy researcher, joins Vanderbilt Peabody College

Explore story topics.

- myvu monday

- Douglas Fuchs

- Ideas Featured

- Ideas In Action

- Michael Yudin

- National Center for Education Statistics

- Peabody College

- Peabody Reflector Fall 2023

- peabody-home

- special education

- U.S. Office of Special Education

- Vanderbilt Peabody College of education and human development

- Current Issue

- Journal Archive

- Current Call

Search form

Inclusion Census: How Do Inclusion Rates in American Public Schools Measure Up?

Maria Silva, Doctoral Candidate, Florida International University Martha Lorena Hernández Flores, Doctoral Candidate, Florida International University Dr. Elizabeth Cramer, Professor, Florida International University

This study examines trends and variations of inclusion placement for students with disabilities (SWDs) in the United States using Florida as a state-level case study. The study investigates three main areas: placement trends in inclusion settings that exist based on disability category and race, inclusion rates in the largest counties in the state compared to the mean of inclusion in the state, and inclusion variations across all public school levels in the fourth largest, urban school district in the US. Findings suggest that although the rate of inclusion is increasing, there is a lack of equity in inclusion placement practices.

Keywords: special education, inclusion, students with disabilities, educational placement

Educational researchers have long discussed the education of students with disabilities (SWDs) in inclusive settings and related equity gaps (Artiles et al., 2006; Cole et al., 2021; McLeskey et al., 2012; Pak & Parsons, 2020; Williamson et al., 2020). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requirements have created pressure to address historical inequities in educational outcomes, achievement, and opportunities for SWDs. For example, the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA and the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 further amplify the right for SWDs to receive a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE). Disability rights advocates argue that the LRE is always the general education setting, as the law calls for SWDs to receive special education services alongside their nondisabled peers to the most extent possible (Choi et al., 2020; Kirby, 2017). These policy reforms in special education have driven school districts to provide special education services in more inclusive settings (Author, 2014; Goodman et al., 2011; van Seen & Wilson, 2020).

However, racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse (RELD) students in urban areas are disproportionately referred, identified, and placed in special education and are more frequently segregated and excluded from general education once placed (Blanchett et al., 2009). While inclusion percentages have increased, questions remain about the equity of inclusion placements and practices for RELD SWDs (Giangreco, 2020). Blanchett et al. (2009) argue that the issues of disproportionality in the identification and placement of SWDs at the intersection of race, culture, language, and disability and the continued segregation of these students are perpetuating educational inequities while simultaneously perpetuating White dominance. Skrtic et al. (2021) note that the role of race in disability classification has shaped disability labeling for RELD students, ultimately leading to more students from minoritized backgrounds being represented in “low-status” disability categories that are less frequently considered for inclusion.

In this article, we draw attention to factors affecting inclusion placement and discuss equity issues in urban schools that impact the placement of RELD SWDs in inclusive settings. We then use a state-level case study in Florida using descriptive statistics t- tests, General Linear Modeling (GLM), and multilevel analyses to draw attention to the inequities in inclusion placement in US public schools. We illustrate placement trends in inclusion settings that exist based on disability category and race, inclusion rates in the top 20 populated counties of a large southeastern state compared to the mean of inclusion in the state, and inclusion variations across all school levels in the fourth largest school district in the country. Although inclusion rates are increasing overall, inequities persist in inclusive practices. In our discussion, we present suggestions for future research to shift placement practices for RELD SWDs.

Background on Special Education Settings

The term “inclusion” refers to SWDs in a general education classroom for 80% or more of the school day and therefore is considered the starting point of the LRE (Grindal et al., 2019; McLeskey et al., 2012; National Council on Disability [NCD], 2018; Williamson et al., 2020). Modern-day inclusion models have branched out from the more traditional co-teaching frameworks and now include support facilitation and consultation services (Broward County Public Schools [BCPS], 2017; Friend, 2015), which may lead to the successful outcomes of SWD. Efficacious inclusion programs constitute an integrative setting where SWDs receive the same curriculum and standards-based instruction alongside students without disabilities in a general education classroom for 80% or more of the school day with support services and accommodations given by a highly-qualified special education teacher (Choi et al., 2020; Gilmour, 2018; McLeskey et al., 2012).

The reform in federal legislation and mandates have been the impetus behind states and school districts pressing for the placement of more SWDs in inclusion settings (Cole et al., 2021; Giangreco, 2020; Kirby, 2017; Williamson et al., 2020) to meet compliance requirements (Voulgarides, 2022). Giangreco (2020) confirms that in the United States, the percentage of SWDs placement in inclusion settings has increased over the past 30 years; however, Giangreco questions the equity of the placement trends. In 2019, the US Department of Education (USDOE, 2022) reported that SWDs across the country, ages 5–21, who received special education services in inclusive classrooms was 64.8%, a substantial increase from 19 years prior, in 2000, when the percentage was 46.5% (Cole et al., 2021; National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2019). In 2019, the percentage of SWDs serviced within an inclusive setting (ages 6–21) in Florida was 77% (Florida Department of Education [FLDOE], 2020), which was higher than the national percentage. Yet, disproportionality remains for inclusion placement among disability categories, race, and school levels.

Factors Affecting Inclusion Placement

The federal mandates that have been the catalyst for restructuring the decision-making in placement and service delivery for SWDs in LRE are not without flaws (Cole et al., 2021). Voulgarides (2022) argues that the compliance-based approach used to implement federal mandates has failed to meet the needs of SWDs. Various factors can affect inclusion placement, including historical systemic biases, proper interpretation of LRE, and teacher factors.

Historical Systemic Biases

Systemic biases have long existed, perpetuating segregation for SWDs, particularly those from RELD groups. Students from minoritized groups are more likely to be identified as having a disability and to receive services in a “substantially separate setting” (Grindal et al., 2019, p. 542). This is due to systemic biases that are perpetuated in placement processes. For example, Skrtic et al. (2021) analyzed a large federal longitudinal dataset. They found that minoritized students are overrepresented in what he deems as “low status” disability categories (i.e., intellectual disabilities [ID] and emotional and behavioral disorders [EBD]). This is in line with what Sullivan and Artiles (2011) termed the racial stratification of disabilities. This bears significance on the inclusion conversation, as historically, students with EBD have been the least included, with low rates of inclusion for students with ID as well (NCES, 2022).

Conversely, White students tend to be overrepresented in “higher status” disabilities such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or specific learning disabilities (SLD), categories that are most often linked to inclusive placements (NCES, 2022). This racial stratification serves as a legal justification for segregation (Sullivan & Artiles, 2011). Grindal et al.’s recent study (2019) found that regardless of income level, racial disparities persist in special education identification and placement decisions. These disparities lead to increased segregation and decreased opportunities to access high-quality instruction.

Interpreting Least Restrictive Environment

Giangreco (2020) suggests that ableism, school districts misapplying the provisions of LRE, and teachers having difficulty utilizing inclusive practices account for why schools do not place SWDs in general education classrooms. Giangreco further clarified significant misinterpretations of how to determine LRE placement, such as (a) students’ disability categories do not dictate their educational placement, (b) SWDs are not required to be functioning at or close to grade-level expectations to be placed in an inclusive setting, and (c) SWDs do not need to change or conform to predetermined standards to be placed in inclusion. Decisions about educational placement for RELD SWDs are often based on these misinterpretations.

Teacher Factors

Another factor impacting the rate of inclusion placement is the surge in inclusive education (IE) for SWDs, which requires more diversification of teacher roles (van Steen & Wilson, 2020). IE was initially defined simply as placing SWDs in mainstream programs with their nondisabled peers (Artiles et al., 2006). Through the evolution of IE, there has been a shift to change the historical segregation of SWDs by transforming school culture, implementing equity-based practices, and enhancing the achievement of all students (Artiles et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2020). Depending on teachers’ knowledge of evidence-based practices and their willingness to apply creative problem-solving skills needed to support their students, teachers may serve to hinder or expand opportunities for success for SWDs (Giangreco, 2020). For IE to have the desired effect, teachers must be willing to acclimate their pedagogy and be capable of diversifying their lesson plans, making adaptations to their classroom settings, implementing accommodations, and managing disruptive behaviors (Dev & Haynes, 2015; van Steen & Wilson, 2020). Teachers, who are key members of the Individualized Education Program team, are at the forefront of IE and are the first level of support SWDs will receive; their attitudes toward this movement can serve as an advantage or a disadvantage for students.

Relatedly, Grindal et al. (2019) argue that a teacher’s interpersonal racism, or explicit and implicit beliefs regarding the capacity of students from diverse backgrounds (e.g., RELD, SWDs, low social class) impacts student educational placement. Biased teacher perceptions at the intersection of race and disability may result in reduced teacher advocacy for inclusion placement and further exclusion of students of color and/or SWDs (Fish, 2019). Studies examining teacher attitudes toward inclusion have shown mixed findings. Using a meta-analysis, van Steen and Wilson (2020) reviewed 64 studies from all over the world regarding teacher attitudes toward inclusion. Results revealed that, in general, teachers have a positive attitude toward including SWDs within general education classrooms and showed a willingness to support inclusion. van Mieghem et al. (2020) contradicted the results from the previous study in a systematic review and meta-analysis. In their review of 26 studies, van Mieghem et al. noted that teachers generally had negative attitudes toward IE and suggested that they felt unprepared to support SWDs aptly and needed more targeted and effective professional development.

Equity in Public Education

Schools do not place all SWDs in inclusive settings at the same rate. Fish (2019) contends that schools continue to sort SWDs in ways that perpetuate racial inequities. In a comprehensive study by Grindal et al. (2019), the authors analyzed data sets for three US states to investigate differences in placement for SWDs enrolled in K–12 schools. Their findings concluded that SWDs who are Black or Hispanic were more likely to be placed in segregated classroom settings compared to SWDs who are White (Grindal et al., 2019). Proponents of IE, Gatlin and Wilson (2016) believe the overrepresentation of minority groups in special education and their placement in more restrictive settings limits their opportunities for success instead of increasing them. Author (2014) reported a shift of students identified with SLD from primarily White students to students of color. Additionally, the authors stated that urban students with an SLD are less likely to be in inclusive settings than suburban SLD students. Overall, RELD students in special education are more likely to be serviced in separate settings (Author, 2014).

Another equity gap in urban education is the aforementioned disability hierarchy, the belief that some disability categories (i.e., higher-status disabilities) are preferred over others (i.e., lower-status disabilities). This stratified status is reaffirmed by Fish (2019), whose research revealed that White students are more likely to be identified with a higher-status disability. In contrast, students of color are more often identified with a lower-status disability. Gilmour (2018) suggests that students selected for inclusion may have higher academic abilities and fewer behavioral challenges than those placed in less inclusive settings. Goodman et al. (2011) found that schools place students with mild disabilities, those working toward a standard diploma, and those assessed using statewide assessments in inclusive settings more often. These discrepancies and variations in inclusion placement based on disability category and race motivated analyzing inclusion placement in public schools.

Equity gaps and disproportionality also exist among school levels. A study conducted by McLeskey et al. (2012) analyzed the cumulative placement rates for SWDs in 1990–1991 and 2007–2008 across the United States, taking into account the 13% increase in students identified with disabilities during this period. Their analysis looked at inclusion rates at the elementary (ages 6–11) and secondary (ages 12–17) levels. Results showed that placement of elementary level SWDs in inclusive general education settings increased by approximately 59% from 1990–1991 to 2007–2008, and placement of secondary level SWDs soared by 191% (McLeskey et al., 2012). More recently, Williamson et al. (2020) studied placement trends from 1990 to 2015 and reported that inclusion placement at the elementary level increased by 66% and 235% at the secondary level. Thus, the rate at which schools place students in an inclusion setting is rising at the elementary and secondary levels; however, the secondary level has increased significantly.

Additionally, in their examination of national trends in the educational placement of SWDs from 1990 to 2015, Williamson et al. (2020) acknowledged the rapid growth of inclusion placement at the secondary level but pointed out that students in secondary schools continued to be placed in resource pullout settings more often than elementary students. Their report also found that students with SLD, other health impaired (OHI), and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) accounted for the increase in general education placement. Coincidently, students with ID and EBD accounted for decreased pullout placements and an increase in inclusion placement (McLeskey et al., 2012; Williamson et al., 2020). Multiple studies have indicated that students with SLD have garnered the highest increase in inclusion placement in public schools across the United States among all the disability groups (McLeskey et al., 2012; NCD, 2018; Williamson et al., 2020).

Our literature review indicates that inclusion rates have increased; however, the rates vary by disability category, race, and school level. Students with ID or EBD, RELD students, and those in urban settings continue to be separated and segregated from the general student population. The research questions in this article aim to break down the inclusion rates in American public schools by exploring Florida public schools’ datasets with a closer focus on Miami-Dade County Public Schools (MDCPS). In 2010, the United States Census Bureau (2021) rated the city of Miami as the fourth most populous urbanized area, and MDCPS is the fourth largest urban school district in the country, with RELD students making up 93.5% of the total population of students (MDCPS, 2020). This study aimed to examine trends and variations of inclusion placement for SWDs in urban educational settings. Using a Florida data set, we applied an inverted pyramid approach to narrow our examination of inclusion placement by initially looking at the overall state’s placement trends based on disability and race, followed by the overall mean data for inclusion placement in the largest populated counties in the state. We concluded with an analysis of placement trends in all school settings within the largest urban county in the state. We investigated the following three questions: (1) What inclusion placement trends exist for SWDs at the intersection of disability category and race? (2) How does the percentage of SWDs serviced in inclusion settings in the largest counties compare to overall state percentages? (3) What inclusion placement trends exist for SWDs at the school level (e.g., elementary, middle, high) within a large urban district?

Methodology

Data Sources

The data for this study were secondary public data obtained electronically from the FLDOE website. In 2020, Florida reported servicing 2,858,949 students in grades PK–12, with 14% being SWDs (FLDOE). As per federal and state mandates, school districts must provide accurate information regarding SWDs yearly (Gilmour, 2018). Florida’s State Education Agency (SEA) creates a yearly profile that targets 16 indicators relating to the educational environment, educational benefit, prevalence, parental involvement, and federal requirements for planning improvements in special education programs (FLDOE, 2020). Likewise, each county’s Local Education Agency (LEA) creates a profile and submits it to the state. The state then furnishes this information to the USDOE to be included in the annual report to congress that relays information on the national progress in providing IDEA services (USDOE, 2020; Williamson et al., 2020). This public information includes, but is not limited to, state assessment scores, graduation rates, environmental placement, disability categories, race/ethnic background information, and teacher qualification information.

Among the data reported by the state are child counts for the educational environments of SWDs (ages 6–21) who were provided services in Florida schools. The data was reported under IDEA Part B during the 2019–20 school year (SY; n = 377,535) by eligibility category and race. We used these data for our initial research question, investigating overall inclusion placement trends for SWDs (ages 6–21) based on disability category and race. Concerning our second research question, the Florida SEA and LEA Profiles for the 20 largest counties were examined in the following years and correspond to particular SYs as follows: 2010 Profile for the 2008–2009 SY, 2015 Profile for the 2013–2014 SY, and 2020 Profile for the 2018–2019 SY. The top 20 populated counties in Florida in descending order are Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach, Hillsborough, Orange, Pinellas, Duval, Lee, Polk, Brevard, Pasco, Volusia, Seminole, Sarasota, Manatee, Collier, Osceola, Lake, Marion, and St. Lucie (The Florida Legislature, 2019). The top 20 populated counties were targeted for this investigation as 91.2% of Florida’s population live in urban areas (The Florida Legislature, 2019) and therefore have a higher concentration of students.

For our third research question, we narrowed our search to investigating the largest urban school district in Florida, MDCPS (The Florida Legislature, 2019). In particular, we analyzed the educational placement setting records for all schools within MDCPS over three SYs. Urban school districts generally fall behind in inclusion rates compared to the national average (Author, 2015), as is the case for MDCPS, which reported an inclusion rate of 62% in 2019, compared to the state of Florida, which was 77% and the national average of 64.8% (FLDOE, 2020; USDOE, 2022). During the 2019–2020 SY, MDCPS reported servicing 480 traditional and charter schools with a total student enrollment of 347,069 students in grades PK – 12, 11% of whom are SWDs (FLDOE, 2020; MDCPS, 2020). The demographic breakdown of this district is as follows: White Non-Hispanic 6.5%, Black Non-Hispanic 19.5%, Hispanic 72.2%, Other 1.8%, and students on free/reduced lunch 67.8% (MDCPS, 2020). We made a public records request to the commissioner of the FLDOE in December 2020 to access information regarding the educational placement records for all public schools within this school district for the previous three SYs.

The study variables were composed of three levels: Florida state, the top 20 populated counties, and one large urban county. We manually imported data into SPSS software at the state level to calculate and provide descriptive analysis, trends, and variations in inclusion placement for SWDs in Florida. The main outcome variable in the investigation into the placement trends in inclusion settings was the SWDs (ages 6–21) serviced in the state during the 2019–2020 SY (n = 377,535). Independent variables included eligibility category and race. We extracted data from the FLDOE (2020) child count report. We disaggregated it to determine the percentages of SWDs in the state of Florida (n = 377,535) versus the percentages of students placed in inclusion settings in Florida based on eligibility category and race.

At the county level, we first looked at the total population of K–12 grade students for each of the 20 counties for each of the three years to investigate inclusion trends. We then computed the number of SWDs from the total population and the corresponding percentage of SWDs from the total population. From the number of SWDs, we calculated the percent placed in inclusion for each of the three years. To further examine trends in inclusion, we grouped the counties into counties with a relatively high population of disabilities and counties with a relatively low number of disabilities for the 2020 SY. We calculated the mean disability proportion (.1475) and used .15 as a cutting-off point for high and low disability. The nine low disability counties included: Miami-Dade, Broward, Orange, Pinellas, Lee, Polk, Collier, Osceola, and St. Lucie. The 11 high disability counties included: Palm Beach, Hillsborough, Duval, Brevard, Pasco, Volusia, Seminole, Sarasota, Manatee, Lake, and Marion.

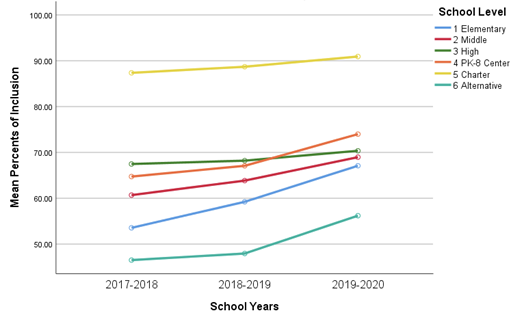

Regarding our third research question, we analyzed data for educational placement of all SWDs in MDCPS by school level for the previous three SYs, 2017–2018, 2018–2019, and 2019–2020. The school levels were elementary (PK–5), middle (6–8), high (9–12), PK–8 centers, charter schools, and alternative settings. PK through 8 schools are institutions that educate students from pre-kindergarten up until 8th grade. Public charter schools are publicly funded schools that can serve students in grades PK–12 and typically operate under a legislative performance contract that affords them more autonomy than traditional public schools (Blazer, 2010; Hussar et al., 2020). Given that charter schools are not required to follow a specific instructional approach and have the flexibility to make their own decisions regarding budgets, class sizes, and staffing (Blazer, 2010), we decided to identify them as a separate school level. Alternative settings refer to school locations that were either juvenile detention centers, alternative education centers, specialized centers (i.e., hospital homebound), or residential centers as the student population for these more restrictive settings fluctuates throughout the SY and usually provides extensive educational services that would not correlate with IE Thus, their data may skew the results of this study.

Data Analysis

This study employed descriptive statistics t- tests as preliminary analyses and General Linear Modeling (GLM) and multilevel analyses as the primary analyses. With preliminary analyses, we examined relationships between the percentage of SWDs in inclusive settings by county with the state’s mean for each year in the study. We used t -tests and GLM to determine if there was any significant difference between the means of various groups (Howell, 2013).

Utilizing education placement data provided by FLDOE (2020) for MDCPS to investigate three SYs, 2017–2018, 2018–2019, and 2019–2020, the study conducted GLM and multilevel analysis to analyze the changes of SWDs varied by school levels. We tallied placement data within five categories: regular class, resource room, special classroom, other separate environments, and the total number of SWDs. As per FLDOE (2020), a regular class consists of SWDs being included within the general education classroom with peers without disabilities for 80% or more of the school week, resource room is inclusion for 40 – 80% of the school week, special classroom is inclusion less than 40% of the school week, and other separate environments are specialized centers, residential placements, or hospital/homebound placements. For this study, data listed within “regular class” were analyzed as full inclusion data.

First, we coded data for the educational placement of all SWDs in MDCPS by school level. For GLM, coding entailed the following 6 categories: 1 = elementary school, 2 = middle school, 3 = high school, 4 = PK–8 school, 5 = charter school, and 6 = alternative school. The study used the graphical presentations of GLM and compared the SWDs changes over three academic years. We created five dummy coded variables for multilevel analysis, and the charter school served as a reference group school. Taking advantage of the flexibility of multilevel analysis concerning statistical assumptions and applications, we interpreted multilevel outcomes for the initial gaps and growth rates (changes over three years) among different schools. A small number of schools (n < 5) serviced grades 6–12, and they were coded as middle school because that was the starting grade level for that school. We coded the small number of schools (n < 5) that serviced only grades 11–12 as high school.

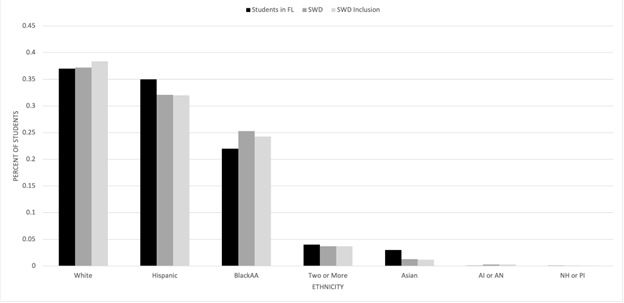

Overall, inclusion rates in the state increased over the ten years reviewed (FLDOE, 2020). The overall inclusion percentage was 64% in 2010, 71% in 2015, and 76% in 2020. To examine the placement trends in inclusion settings at the intersection of disability and race, we disaggregated the data by race to compare the percentages of students enrolled in PK–12 public schools (n = 2,858,949), the percentages of SWDs, ages 6–21 (n = 377,535), and SWDs placed in inclusion settings (n = 285,955; FLDOE, 2020). Florida reported child counts for the 2019–20 SY for SWDs, ages 6–21, under the following seven racial categories: American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic/Latino, Two or More Races, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White. The racial demographics showed that most SWDs in Florida and most students in inclusion were White, Hispanic, or Black/African American. In all seven racial categories, the percentages of overall SWDs and the percentages of students in inclusion were significantly similar. Of those three racial and ethnic categories, a visual analysis of the data (Figure 1) shows that White students appear to be identified with a disability at a rate comparable to their overall population but are more likely to be placed in inclusion. Hispanic students are less likely to be identified with a disability, but their placement in inclusion seems comparable to those identified with a disability. Meanwhile, Black students are more likely to be identified with a disability and are less likely to be placed in inclusion.

Comparison by Race for 2019-2020 School Year in Florida Schools

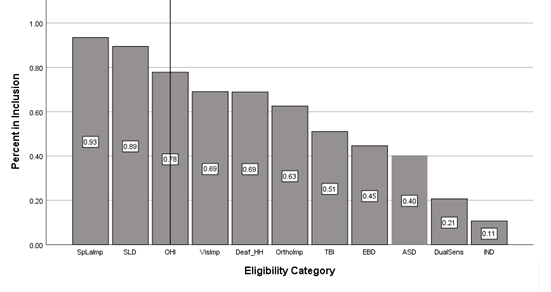

As delineated in Figure 2, during the 2019 – 20 SY, Florida reported child counts for SWDs, ages 6 – 21, grouped into 11 eligibility categories. Data indicated that the three main eligibility categories placed in inclusion settings were speech and language impairment (SLI; 93%), SLD (89%), and other health impairments (OHI; 78%). The three eligibility categories with the lowest inclusion rates were autism spectrum disorder (ASD; 40%), dual sensory impairment (21%), and ID (11%).

We also compared the percentage of SWDs (n = 377,535) to the percentage of students placed in inclusion (n = 285,955) by eligibility category, as depicted in Figure 2. The eligibility category with the highest rate of inclusion was SLI. Data showed that a large percentage of SWDs in Florida were identified as having SLD (42%). Of the 42% of students with SLD, 89% were placed in an inclusion setting. The state reported a small population of students in the eligibility category of deaf or hard of hearing (1%), traumatic brain injury (.1%), and visual impairments (.3%). Of these three categories, most students were serviced in inclusion settings. The lowest population category was students with dual sensory impairment (.02%); however, most were serviced in a self-contained setting, meaning inside the regular classroom for less than 40% of the school day.

Students with Disabilities in Inclusion by Eligibility Category 2019-2020 School Year

Note. The data for this figure were retrieved from the FLDOE (2020) child count by eligibility category and educational environments in Florida. Key for eligibility category: SpLaImp = Speech and/or Language Impairment, SLD = Specific Learning Disability, OHI = Other Health Impairment, VisImp = Visual Impairment, Deaf_HH = Deaf or Hard of Hearing, OrthoImp = Orthopedic Impairment, TBI = Traumatic Brain Injury, EBD = Emotional/Behavioral Disorder, ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder, DualSens = Dual Sensory Impairment, IND = Intellectual Disability.

Next, we compared the mean percent of inclusion for Florida's 20 largest counties between 2010, 2015, and 2020 by conducting GLM. The results of the GLM show a significant linear growth pattern ( B = .149, F = 29.25, p =.00), indicating that more students were placed in inclusion settings in the 20 largest counties over the ten years. Specifically, these results demonstrate that the state's inclusion rate is increasing.

We conducted an independent-samples t-test to compare the inclusion rate for counties with a low disability rate and counties with a high disability rate for 2020 (Table 2). The nine counties identified as having low rates of disability ( M = 0.76, SD = 0.08) compared to the 11 counties identified as having high rates of disability ( M = 0.78, SD = 0.06) demonstrated no significant difference in the percent of inclusion for the test year, t (20) = -0.676, p = .51. These results suggest that the average rate of inclusion of high disability counties is not significantly different from that of low disability counties. Specifically, the results suggest that the rate at which schools placed SWDs in inclusive settings was no different in counties with a high number or low number of SWDs.

Results of Independent t-tests and Descriptive Statistics for the Year 2020, by High Disability and Low Disability Counties

We conducted three separate Pearson correlation analyses to confirm the relationship between the percentage of students in inclusion settings and the overall SWDs percentage. 2010, 2015, and 2020 showed no correlation between the percentage of students in inclusion settings and the percentage of SWDs for the years evaluated. Thus, a change in percent of SWDs had no effect on the percent of students in inclusion settings ( r = .289, p = .216 in 2010; r = .128, p = .590 in 2015; and r = .162, p = .495 in 2020).

Finally, we compiled educational placement information for SWDs from every public school within MDCPS over three SYs. We tallied placement data within five categories: regular class, resource room, special classroom, other separate environments, and the total number of SWDs. Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics for the percent of SWDs placed in inclusion settings in MDCPS for the three SYs investigated. The table shows that MDCPS's mean inclusion rate rose from 64% in 2010 to 76% in 2020.

Results of One-sample t-test and Descriptive Statistics for MDCPS Mean Percent of Inclusion and Florida’s Mean Percent of Inclusion for 2010, 2015, and 2020

Note: * indicates significant at 0.05 and ** indicates significant at 0.01