What does the unemployment rate measure?

Subscribe to the hutchins roundup and newsletter, stephanie aaronson stephanie aaronson senior associate director, division of research and statistics - federal reserve board.

February 18, 2021

- 13 min read

This explainer builds off of a May 2020 post, “ Making Sense of the Monthly Jobs Report During the COVID-19 Pandemic .”

The unemployment rate soared from a 50-year low of 3.5 percent to 14.8 percent in April 2020 at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and then fell faster than many forecasters anticipated, to 6.3 percent in January 2021. But the labor market is far from healthy: for instance, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) counted 4.5 million more people as unemployed in January than were unemployed before the pandemic—and many more people weren’t counted as unemployed because they’d stopped looking for work. Here’s a guide to various measures of the health of the labor market.

What does the unemployment rate measure?

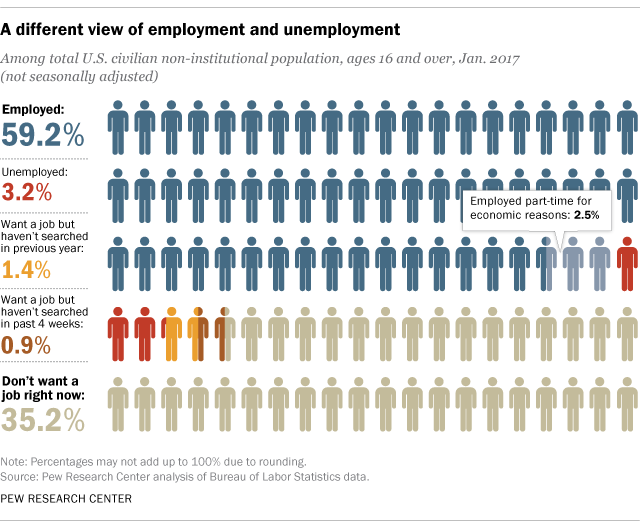

The headline unemployment rate (known as U-3) measures the percentage of people over the age of 16 who aren’t working but are available and actively looking for work.

Where do the data on unemployment come from?

Data on unemployment are collected every month in the Current Population Survey (CPS), a survey of about 60,000 households , conducted by the Census and the BLS every month, which includes roughly 105,000 people ages 16 and older . The questions about unemployment refer to what people were doing during the week that includes the 12th of the month, known as the “reference week”—so the survey to be released on Friday, March 4, 2021 will cover the week of February 8, 2021. The CPS is referred to as the household survey, to distinguish it from the establishment survey, which counts the number of people on employer payrolls. (The latest tally of payrolls showed that as of January 2021, we have recovered 9.9 million of the 22.4 million jobs lost since the beginning of 2020.)

How are individuals in the monthly survey identified as being unemployed ?

Respondents to the survey are first asked whether they worked during the week that includes the 12th of the month. Individuals are counted as employed if they did any work at all as a paid employee, if they worked in their own business, or worked without pay for at least 15 hours in a family business. People are also counted as employed if they were temporarily absent from work as a result of sickness, bad weather, vacation, a strike, or personal reasons. Such workers are classified as employed but absent from work.

Respondents who are not employed then are asked if they have looked for work in the previous four weeks and are available to work. If so, they are counted as unemployed. Respondents who did not work but are on temporary layoff from a job with the expectation that they will be recalled—as many furloughed employees are today—are counted as unemployed whether they looked for a job or not.

What’s the difference between being unemployed and being out of the labor force?

People who are not working and who don’t meet the criteria to be counted as unemployed are said to be out of the labor force. This category includes students, retirees, and those who stay at home to take care of family members. In addition, people who report wanting a job but who have not looked for work in the most recent four weeks are also considered out of the labor force. Between February 2020 and January 2021, 5.5 million people dropped out of the labor force, on net. At the same time, the number of people out of the labor force who said they wanted a job rose by 1.9 million.

Why is it hard to determine if people are unemployed in the COVID-19 pandemic?

While the survey questions are the same as always, the nature of the COVID-19 economy means that people’s behavior, and hence the data, may not follow the same pattern that we usually see when the economy is turning down. For instance, early in the pandemic, the share of workers reporting themselves employed but not at work skyrocketed. While some of this increase was due to a rise in illness or childcare responsibilities, the number of people reporting themselves “not at work for other reasons” rose from around 600,000 prior to the pandemic to over 8 million. In conducting the survey, the BLS has attempted to categorize those employed but absent from work due to “pandemic-related business closures or cutbacks” as unemployed. Despite this effort, an unusually large number of workers in this situation have still been counted as “not being at work for other reasons,” which the BLS views as misclassification . Following its typical procedure, the BLS has categorized individuals reported as “not being at work for other reasons” as employed rather than unemployed. While this classification is in keeping with their standard practice, it has the effect of depressing the unemployment rate relative to a case where these workers are categorized as unemployed. That said, this misclassification is certainly less severe now than it was early in the recession: in January 2021, the number was 1.7 million. In addition, the BLS has publicly stated its estimate of the size of this mismeasurement. In January, the BLS reported that if misclassified workers had been counted as unemployed, the unemployment rate would have been 0.6 percentage points higher, or 6.9 percent. It also noted that this was an upper-bound estimate.

Among those who have lost jobs, the typical behavior would be to transition from employment into unemployment rather than to transition out of the labor force. However, early in the pandemic, with stay-at-home orders in place and nonessential businesses closed in many communities, people who left employment were much less likely to seek work than would typically be the case. In addition, schools closed in many places, which meant that many people who lost their jobs had child-care responsibilities that prevented them from seeking or accepting a new job. Even now, nearly a year into the pandemic, many of these same dynamics are in place. As a result, relative to a typical downturn, we expect the headline unemployment rate to be relatively lower than in a typical recession and the percent of those out of the labor force to be relatively higher, especially the percent of those who say they want a job but aren’t looking.

Indeed, we saw evidence of this in March 2020 , when, relative to the prior trend, an additional 1.2 million people moved from employment to out of the labor force, and the number of people categorized as out of the labor force but wanting a job rose by 500,000. The resulting decline in the labor force participation rate was much larger than would be expected given the rise in the unemployment rate, and it remains unusually low.

Given the limitations of the unemployment rate as a measure of labor market slack, what are some alternatives?

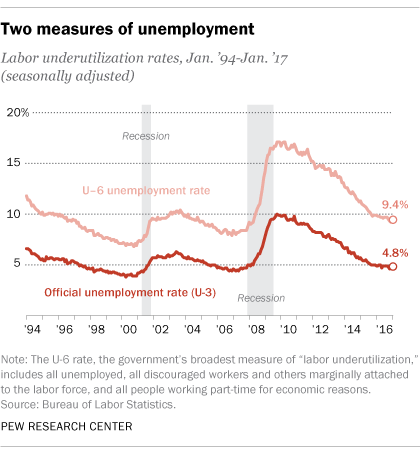

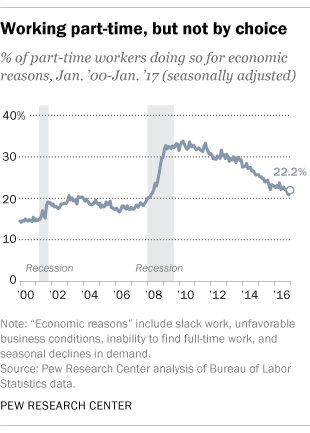

The BLS releases six measures of labor market slack in the monthly jobs report. These include the official unemployment rate (U-3), discussed above, as well as more narrow definitions, called U-1 and U-2, which respectively include only those unemployed at least 15 weeks (the long-term unemployed) or for less than a month (the short-term unemployed). The BLS also publishes broader definitions of slack. The U-6 rate, for instance, counts all those who are technically unemployed plus those are who are working part-time but would prefer full time work, and those “marginally attached to the labor force,” that is, people who say they want either a full-time or part-time job, have not looked for work in the most recent four weeks, but have looked for a job sometime in the past 12 months. When adults classified as “marginally attached” report that they did not recently seek work because they do not believe jobs are available for them, they are classified as “discouraged workers.” The U-4 counts the unemployed and discouraged workers, while U-5 adds in other marginally attached workers. In January, the broadest of these measures, U-6, stood at 11.1 percent, 4.8 percentage points higher than the official unemployment rate.

Given the measurement problems during the pandemic, are there alternatives to the BLS indicators of slack to gauge the health of the labor market?

Some economists have offered their own estimates of labor market slack trying to account for the misclassification and unusual movements in labor force participation during the pandemic. For example, Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III at the Peterson Institute for International Economics calculate what they call the “ realistic unemployment rate .” Their realistic unemployment rate was 8.3 percent in January , two percentage points higher than the official unemployment rate. Furman and Powell’s realistic unemployment rate differs from the official in two ways. First, they estimate the number of workers misclassified as being “not at work for other reasons” and count them as unemployed. Second, they try to estimate the excess decline in labor force participation beyond what would be expected given the rise in unemployment, and add those people to the unemployment rate as well. While this estimate is dependent on the specific modeling assumptions, it is nonetheless a useful attempt to reveal the extent to which we underestimate the true disruption to people’s livelihoods if we fail to account for the unusually large drop in labor force participation.

In a recent speech , Fed Chair Jerome Powell outlined his own method for adjusting the unemployment rate to capture the unusual features of the pandemic labor market. First, like Furman and Powell, he adds to the count of the unemployed an estimate of the misclassified workers. In addition, he adds in the number of people who have left the labor force since last February. This measure does not attempt to account for the fact that more people dropped out of the labor force than usual, and it does not account for structural reasons that individuals may have dropped out of the labor force, such as retirement. At the same time, it also isn’t sensitive to the specific modeling assumptions regarding the behavior of the participation rate. His calculations boost the unemployment rate to close to 10 percent in January .

One shortcoming of both these approaches is that they implicitly or explicitly make an assumption about what share of the individuals who are out of the labor force would be unemployed in a more normal recession. In addition, by counting individuals who are out of the labor force as unemployed, these measures would seem to assume that such individuals will act like the unemployed once the economy recovers. But typically, people who are out of the labor force are less likely to become employed than are those who are unemployed. One measure of the unemployment rate that includes individuals out of the labor force but also accounts for this variation in the propensity to return to work is the Hornstein-Kudlyak-Lange non-employment index , which was 9.3 percent in January.

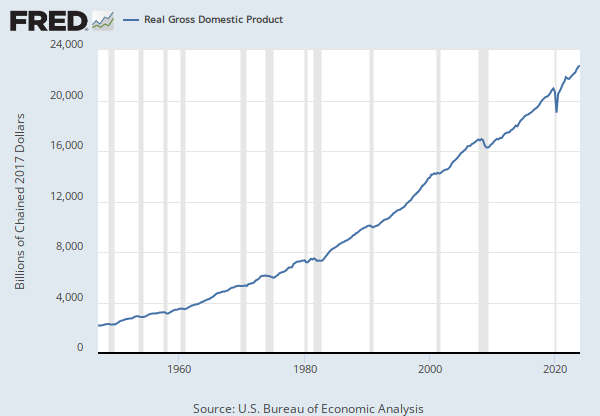

A simpler measure is the employment-to-population-ratio (EPOP), a ratio of the number of people employed to the number of people in the population. The EPOP , which stood at 61.1 percent on the eve of the pandemic, declined by 9.8 percentage points between February and April—the largest decline since the series began in January 1948. Although the EPOP has recovered somewhat, to 57.5 percent, it still stands at its lowest level since the early 1980s, a time when far fewer women were in the labor force. This large drop is direct evidence of the unprecedented toll that the pandemic has taken on the labor market and people’s livelihoods.

What are “initial claims” for unemployment insurance?

When people first file for unemployment insurance (UI), they are counted as an “initial claim.” So when unemployment increases, initial claims tend to rise. Because initial claims are reported weekly , they are often used as an early indicator of the overall unemployment rate.

What is the relationship between initial claims and the unemployment rate — and why might it be different now?

The number of people receiving UI and the number counted as unemployed do tend to move in the same direction, but there is no formal link between the two. The only criteria for being counted as unemployed (and hence included in the unemployment rate) are that you are without a job and that you have actively searched for work or are on temporary layoff. You don’t need to be collecting unemployment insurance to be counted as unemployed. And some people are eligible to collect partial unemployment insurance benefits if they are working but have been assigned a schedule that is far below their usual weekly hours.

Many people who become unemployed do not apply for UI benefits, either because they are not eligible or because they choose not to apply. So initial claims typically understate the number of people becoming unemployed in a given week. That said, there are people who file an initial claim and are not counted as unemployed in the CPS. This could happen if a person doesn’t meet the CPS criteria for being unemployed—for instance, if they file for UI because their work schedule was reduced, or if the person has a very short spell of unemployment which is not captured in the CPS (for example, a person who becomes unemployed and finds a job in between survey reference weeks).

Furthermore, many people who are unemployed and do file an initial claim do not end up receiving unemployment insurance benefits, either because they are not covered by the program, because they have not accumulated enough working hours to be eligible for benefits, or because they don’t satisfy the job search requirements. In February 2020, before the pandemic, the number of people unemployed was about 5.8 million while the number of people receiving UI benefits averaged only about 1.7 million.

What is the payroll survey? And why is it likely to be less useful than usual?

The payroll (or establishment) survey is a survey of 145,000 businesses—employing about one third of all workers on nonfarm payrolls. The payroll survey tends to have difficulty when the economy is at a turning point, as is the case now. To create the sample to be surveyed, the BLS picks firms from the universe of firms that have unemployment insurance tax accounts. However, new firms do not enter the BLS sample universe right away, and the BLS can have difficulty distinguishing non-response from a firm closure in real time. Since the net contribution of jobs created at new firms and jobs destroyed at closing firms is typically small, the BLS assumes that nonresponding firms have the same change in employment as occurred at firms that responded. It then uses a model, called the net birth-death model, to forecast the residual between that imputation and the actual data. This model tends to overestimate employment growth when the economy is weakening and underestimate it when the economy is improving. And while the model error is typically small, it can, on occasion, be large.

We know about these forecast errors because the BLS revises the data based on more complete information. In most years the benchmark is small, with the level of employment revising up or down by less than 0.2 percentage points. However, strikingly, when the establishment survey data for March 2009—the depths of the Great Recession—were benchmarked, the level of payroll employment was revised down by over 900,000 jobs, or 0.7 percentage points—meaning that employers had shed 75,000 more jobs each month between April 2008 and March 2009 than previously estimated.

If, as a result of the pandemic, an unusually large number of firms are closing and few are opening, it seems possible that even the dramatic decline in employment that we are likely to see will underestimate the true extent of job loss.

Why might the historical link between unemployment and poverty be a misleading way to look at today’s numbers?

When people become unemployed, they lose an important (and sometimes their only) source of income and are at risk of falling into poverty. Of course, the more generous unemployment insurance is, the less likely it is for someone who loses a job to become poor. But unemployment insurance has typically replaced only about 40 percent of lost wages, on average, over the past 20 years, with a lot of variation in generosity across the states.

The federal response to the pandemic changed that. The CARES Act, for instance, added $600 a week to weekly unemployment insurance benefits through the end of July 2020, preventing many families from falling into poverty, and the December extension provided for an additional $300. And, of course, Congress provided two rounds of one-time payments for most families—$1,200 per adult and $500 per dependent child in the spring of 2020 and another $600 per individual in December, with payments phasing out for higher earners. Estimates suggest that about 13 million people were prevented from falling into poverty by these efforts.

The author thanks Francisca Alba for research assistance and Becca Portman for graphic design.

Labor & Unemployment

Economic Studies

The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy

Wendy Edelberg, Tara Watson

August 13, 2024

Anthony F. Pipa, Zoe Swarzenski

August 5, 2024

Wendy Edelberg, Noadia Steinmetz-Silber

July 31, 2024

- Main navigation

- Main content

Recessions and the Trend in the US Unemployment Rate

- Kurt G. Lunsford

The unemployment rate in the United States falls slowly in expansions, and it may not reach its previous low point before the next recession begins. Based on this feature, I document that the frequent recessions prior to 1983 are associated with an upward trend in the unemployment rate. In contrast, the long expansions beginning in 1983 are associated with a downward trend. I then estimate a two-variable vector autoregression (VAR) that includes the unemployment rate and a recession indicator. Long-horizon forecasts from this VAR conditioned on no future recessions project that the unemployment rate will go to 3.6 percent after a long period with no recessions.

The views authors express in Economic Commentary are theirs and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The series editor is Tasia Hane. This paper and its data are subject to revision; please visit clevelandfed.org for updates.

When it comes to analyzing economic indicators to predict where the US economy is headed, the unemployment rate is arguably the variable familiar to most people. It receives attention from academics, policymakers, business economists, and politicians, but also the public at large. An appealing feature of the unemployment rate is its perceived ease of interpretation. A high or rising unemployment rate is a signal of macroeconomic slack or contraction, and a low or falling unemployment rate is a signal of macroeconomic health or expansion.

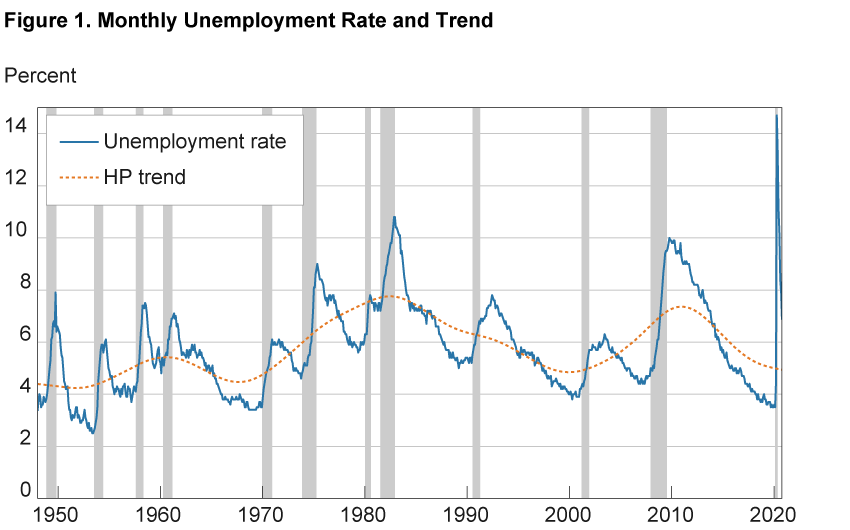

One issue that can confound this simple interpretation is that the unemployment rate may have a slow-moving trend that changes over time. If the trend is not static, then it is hard to know how far the current or forecasted unemployment rates are from the underlying trend. Figure 1 highlights this issue. It shows the monthly unemployment rate from January 1948 to October 2020 along with a line intended to estimate the unemployment rate trend. I compute this line with the statistical technique in Hodrick and Prescott (1997) (HP). 1 The trend line shows substantial variation, falling below 5 percent in the 1960s and 1990s and rising above 7 percent in the 1980s and 2010s. Because of this changing trend, an unemployment rate of 6 percent may be viewed as indicating macroeconomic slack in some periods but macroeconomic health in other periods, making it difficult for economists, policymakers, and the public at large to know where the economy stands. 2

Notes: Trend computed using a Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter. Gray bars indicate recession periods. Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ), and author’s calculations.

Researchers and policymakers often acknowledge the trend in the unemployment rate. Researchers typically remove a time-varying trend from the unemployment rate before studying its business cycle properties. 3 Policymakers on the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) note in their Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy that the maximum level of employment “changes over time.” 4 In fact, the longer-run projections of the unemployment rate in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections have drifted down since 2012. 5

Research has attributed much of the trend in the unemployment rate to demographic changes. 6 In this Commentary , I suggest an additional, previously unrecognized source of the trend: the frequency of recessions. Because the unemployment rate rises quickly in recessions but falls slowly in expansions, it may not fall to its previous low point if a recession cuts an expansion short. 7 Hence, frequent recessions can cause the unemployment rate to trend up over time. Figure 1 shows that this happened in the 1950s and the 1970s. Since 1983, recessions have been less frequent and expansions have been longer, causing the unemployment rate to regularly fall below its previous low point and generating a downward trend in the unemployment rate. 8 In February 2020, the unemployment rate fell to 3.5 percent, its lowest level since 1969.

I also estimate the relationship between recessions and the unemployment rate with a statistical model called a vector autoregression (VAR). I use the VAR to make forecasts of the unemployment rate under the hypothetical scenario that there will be no recessions in the future. I intend for this hypothetical scenario to match the spirit of the FOMC’s longer-run projections of the unemployment rate, which are made “in the absence of further shocks to the economy.” 9 My forecasts project that the unemployment rate will go to 3.6 percent after a long period with no recessions.

Recessions and Unemployment Rate Trends

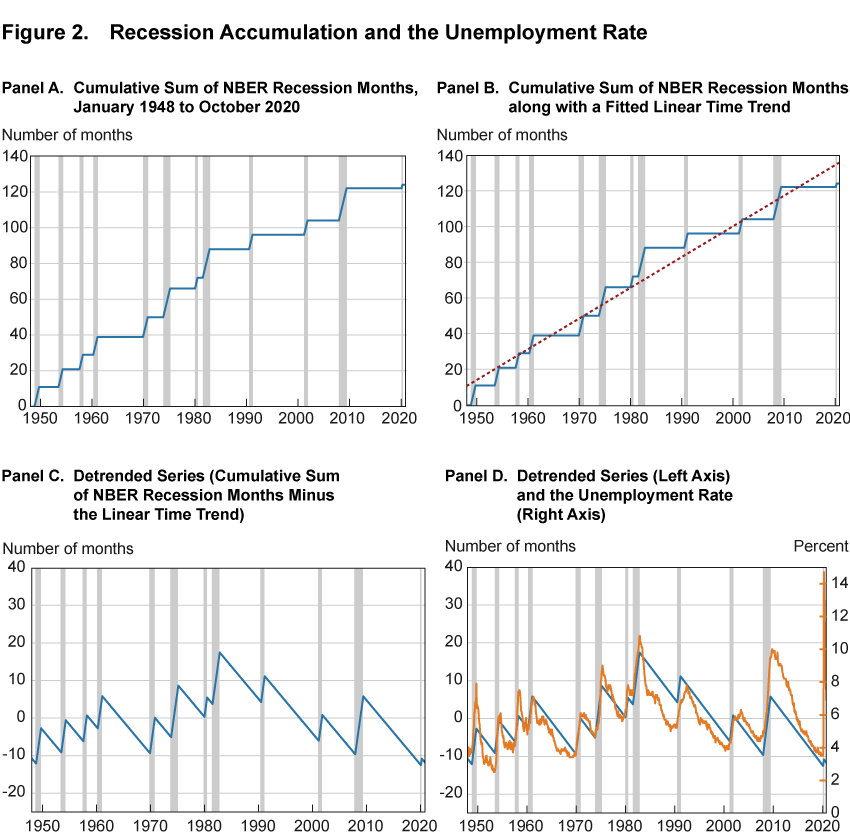

Figure 2 depicts a series of computations that result in a view of the alignment between recessions and the unemployment rate. This view of the alignment (panel D) highlights the intuition that frequent recessions, separated by short expansions, are associated with upward drift in the unemployment rate, while infrequent recessions, separated by long expansions, are associated with downward drift.

Note: Gray bars indicate recession periods. Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ), NBER-based Recession Indicators for the United States from the Period following the Peak through the Trough [USREC], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USREC ), and author’s calculations.

Panel A of figure 2 shows the cumulative sum of the National Bureau of Economic Research’s (NBER’s) recession months from January 1948 to October 2020. I define a recession as starting in the month following the NBER peak and ending in the month of an NBER trough. For the current period, the NBER announced a business cycle peak in February 2020 but has not announced a subsequent trough. In figure 2, I treat March and April 2020 as recession months. 10

In panel B of figure 2, I fit a linear time trend to the cumulative sum of the NBER recession months with ordinary least squares. This time trend gives an estimate of how quickly recessions accumulate on average. Then in panel C, I remove the linear time trend from the cumulative sum and show a detrended cumulative sum of NBER recession months. This detrended cumulative sum shows when recessions have accumulated more quickly and less quickly than average.

The detrended cumulative sum in panel C rises at a constant rate in every recessionary month and falls at a constant but slower rate in every expansionary month. This structure implies that this variable may not fall to its previous low point if a recession cuts an expansion short. As a result, frequent recessions, separated by short expansions, can cause this detrended cumulative sum to drift up over time. This upward drift occurs with the four recessions that begin in 1948, 1953, 1957, and 1960 and again with the four recessions that begin in 1970, 1973, 1980, and 1981. In other words, both 1948 to 1960 and 1970 to 1982 are 13-year periods where recessions accumulated more quickly than average. In contrast, recessions accumulated less quickly than average during the long expansions that occur mostly since 1983 and also in the 1960s. During these periods, the detrended cumulative sum falls below its low point from previous expansions, creating downward drifts in the series.

The periods of rapid recession accumulation, 1948 to 1960 and 1970 to 1982, are also periods when the unemployment rate trend rises in figure 1. In contrast, periods when recessions accumulate less quickly than average, the 1960s, 1983 to 2000, and the 2010s, are all periods when the unemployment rate trend falls in figure 1. To make this comparison between the accumulation of recessionary months and the unemployment rate more explicit, panel D shows the detrended cumulative sum of NBER recession months (left axis) along with the unemployment rate (right axis). The two series move closely together and have a correlation of about 0.7, even including the unusually large spike in the unemployment rate in April 2020.

A positive correlation between the frequency of recessionary months and the unemployment rate is not surprising. The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee uses labor market variables when assigning business cycle peaks and troughs. 11 However, what is surprising about panel D is how closely the unemployment rate follows the detrended cumulative sum of recessionary months for such a long time—from 1948 to 2020. 12 This is surprising because the US labor market has been driven by a variety of economic shocks along with changing government policies, labor market regulations, and demographics; yet, the unemployment rate closely tracks the stable and linear structure of the detrended cumulative sum of recessionary months. As with the detrended cumulative sum of recessionary months, the unemployment rate rises quickly in recessions but falls slowly in expansions, and these features cause the unemployment rate to trend up with frequent recessions and trend down with infrequent recessions.

Longer-Run Unemployment Rate Projections

The results in the previous section show that the unemployment rate trend is aligned closely with how quickly recessionary months accumulate. Consequently, the unemployment rate trend may not be easily separated from the business cycle with statistical techniques that estimate slow-moving trends, such as in Hodrick and Prescott (1997), to offer just one example. This is because the unemployment rate’s trend is itself related to business cycles. 13 Instead, I model the unemployment rate and the NBER recession indicator, which has a value of zero in expansion months and a value of one in recession months, together with a statistical tool known as a VAR.

Using this VAR, I can produce longer-run projections of the unemployment rate in the spirit of the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, which assumes that there will be no shocks to the economy in the future. I do this by producing forecasts of the unemployment rate while imposing that the recession indicator has a value of zero in all future periods. 14

There are two important steps for computing the forecasts. First, I use data from January 1948 to February 2020 to estimate the parameters of the VAR. These parameters establish the statistical relationship between the unemployment rate and the recession indicator, allowing me to predict how the unemployment rate will move in the future under the hypothetical scenario of no future recessions. Second, I choose the initial conditions as a starting point for my forecasts. 15 For example, I need to decide if I want to start my forecasts from a high unemployment rate or a low unemployment rate. Forecasters often use the most recent data as their starting points. However, they may also choose older data to check how accurate their projections would have been in the past.

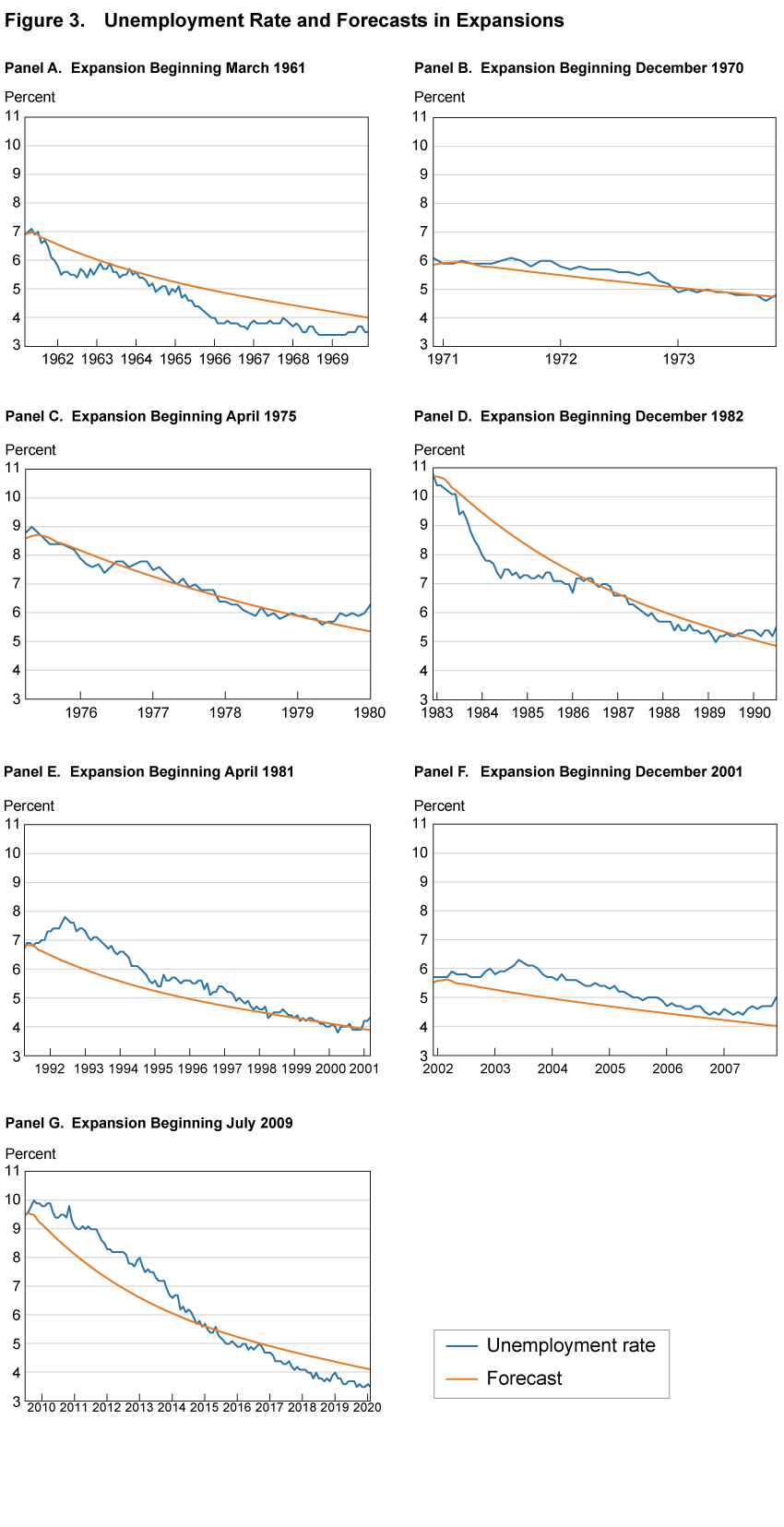

Figure 3 uses this latter approach. Each panel shows the unemployment rate for the 7 most recent NBER expansions. 16 In addition, it shows the forecasts from the VAR under the hypothetical scenario of no recessions. I use the months before each expansion started as the starting point for the forecasts.

Note: Forecasts are computed under the hypothetical scenario of no future recessions. Sources: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ( https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE ), and author’s calculations.

While these forecasts do not perfectly track the unemployment rate over the course of an expansion, they generally match the downward trend of the unemployment rate in expansions. These forecasts also demonstrate relative accuracy in predicting where the unemployment rate will fall at the end of expansions. For the long expansion from 1991 to early 2001, the forecast predicts almost perfectly where the unemployment rate fell. For the other two longest expansions—1961 through 1969 and 2009 to early 2020—the forecast overpredicts where the unemployment rate fell to by about 0.6 percentage points.

The longest expansion shown in figure 3 (panel G)—July 2009 to February 2020—lasted 10 years and 8 months. In order to compute unemployment rate forecasts in the spirit of the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, which assumes that there will be no shocks to the economy in the future, I next consider how low the unemployment rate could fall in expansions that last much longer than 10 years and 8 months. Specifically, I produce forecasts by imposing no recessions for 20 years. 17 In addition, I study the importance of the starting points for the forecasts by considering three different starting points. The first two are November 1982 and June 2009. These are the same starting points that I used in panels D and G of figure 3 and they coincide with the ends of the deepest recessions since 1948. The third starting point is February 2020, which is the last month in my estimation sample.

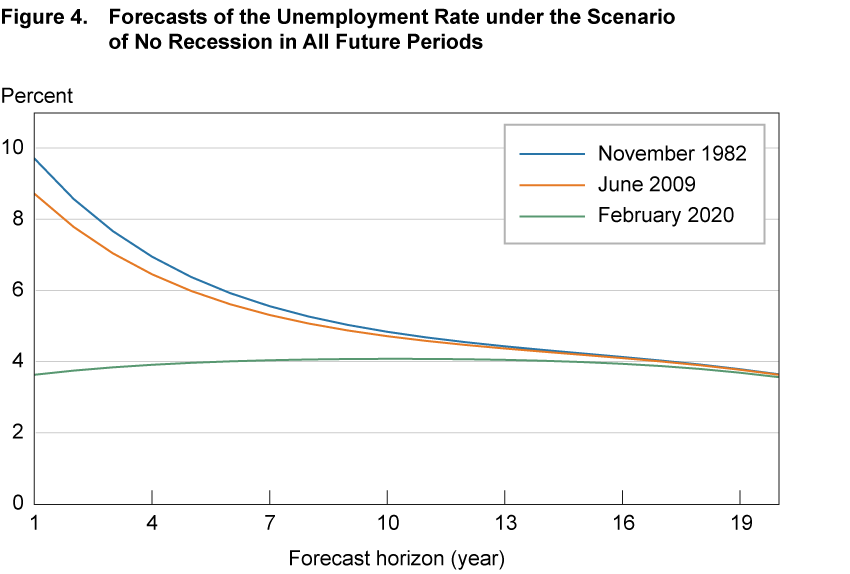

Figure 4 shows the 20-year forecasts. When using the November 1982 and June 2009 starting points, the forecasts start with the unemployment rate at high levels. This is natural as both of these starting points coincide with the end of recessions. In contrast, the forecasts generated with the February 2020 starting point start with a low level of the unemployment rate, a measure which is consistent with the healthy labor market at the start of 2020.

Note: The three lines correspond to three starting points: November 1982, June 2009, and December 2019. Source: Author’s calculations.

The forecasts generated with the November 1982 and June 2009 starting points move down over time. The forecasts generated from the February 2020 starting point rise very slightly before falling again. The forecasts with all three initial conditions become very similar at about 20 years, showing that the starting point does not affect how low the VAR projects the unemployment rate will fall as long as expansions are sufficiently long. For each of the three starting points, the VAR projects that the unemployment rate will be about 3.6 percent after 20 years without a recession. 18 That is, if one were to use this VAR to make a longer-run projection of the unemployment rate in the absence of further shocks to the economy as done in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, then one would project 3.6 percent. 19

The value of the projections in figure 4 is that they provide an answer to where the unemployment rate could fall in a hypothetical world in which recessions do not occur, which I approximate with 20-year forecasts with no recessions. Of course, other choices of forecast length are possible. With shorter forecasts, the starting point of the forecast still matters. As shown in figure 4, the forecasts generated with the November 1982 and June 2009 starting points are not all the way down to 3.6 percent until about 20 years. I have also considered longer forecasts; however, I do not show these forecasts here because they also yield unemployment rates at 3.6 percent.

To check the robustness of my results, I drop early portions of my estimation sample and recompute the long-run forecasts under the assumption of no future recessions. Using samples of January 1958 to February 2020, January 1968 to February 2020, and January 1978 to February 2020, I compute the long-run forecasts of the unemployment rate to be 3.6 percent, 3.8 percent, and 3.6 percent, respectively. These values indicate that the early portions of my sample do not have a big impact on the results. Alternatively, if I use January 1948 to June 2009 as my sample, the long-run forecast is 3.9 percent. This sample choice shows that the 2010s, which were part of the longest expansion in US history, have only a small impact on the results. Overall, the findings suggest that how low the unemployment rate can fall in an expansion appears to be quite stable over a variety of sample periods.

Finally, to highlight how the assumption of no future recessions affects the forecast of the unemployment rate, I also compute the 20-year forecast of the unemployment rate without this assumption. This unconditional forecast of the unemployment rate is 5.7 percent, more than 2 percentage points above the forecast that assumes no future recessions. Clearly, when making longer-run projections of the unemployment rate, such as those in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections, conditioning upon future recessions can make large changes in the projection.

Conclusions

The unemployment rate in the United States falls slowly in expansions, and it may not reach its previous low point before the next recession begins. This feature suggests that the unemployment rate trends up with frequent recessions and trends down when recessions are infrequent. In this Commentary , I show that the US unemployment rate indeed trended up with the rapid accumulation of recessions prior to 1983 and then trended down again with the slow accumulation of recessions after 1983. In addition, I estimate the relationship between recessions and the unemployment rate with a VAR. Long-run forecasts from this VAR under the scenario of no future recessions can be used to produce longer-run projections of the unemployment rate in the spirit of the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections. I find that the unemployment rate moves to 3.6 percent in the absence of future recessions.

- I use a tuning parameter of 106 for the Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter. This parameter is higher than what academic researchers often use for monthly data. I choose this higher value to highlight the lower frequency variation in the data. Using the filter from Müller and Watson (2015) with frequencies of 12 years or longer produces a similar picture. Return to 1

- For example, Weiner (1993) argues that the natural rate of unemployment was about 6.25 percent in 1993 but about 6.7 percent in 1980. An important point is that Weiner (1993) accounts for inflation in his estimate of the natural rate of unemployment. However, the HP filter in figure 1 does not account for inflation, nor do I throughout this Commentary . Return to 2

- For example, see the handbook chapter of Rogerson and Shimer (2011), which like many other studies, uses the Hodrick and Prescott (1997) filter to separate the trend and cycle components of the unemployment rate. Return to 3

- See https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC_LongerRunGoals.pdf . Return to 4

- For the April 2012 FOMC meeting, the range of longer-run unemployment rate projections was 4.9 percent to 6.0 percent. For the September 2020 FOMC meeting, this longer-run unemployment rate range had fallen to 3.5 percent to 4.7 percent. Return to 5

- Weiner (1993), also discussed in footnote 2, emphasizes demographic change. See Crump, Eusepi, Giannoni, and Șahin (2019) for more recent analysis and discussion of demographics and the unemployment rate. Return to 6

- Neftçi (1984) and Sichel (1993) have previously documented that the unemployment rate changes asymmetrically over the business cycle, rising quickly in recessions and falling slowly in expansions. This Commentary draws out the implication that this asymmetry can affect the longer-run trend in the unemployment rate. Return to 7

- Consistent with the slower accumulation of recession months, 1983 roughly corresponds to beginning of the “Great Moderation,” a period in US history in which many economic variables became less volatile (Kim and Nelson, 1999; McConnell and Perez-Quirós, 2000; Stock and Watson, 2002). The results in this Commentary link the Great Moderation to theoretical models of unemployment rate asymmetry, such as Dupraz, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2019) and Lepetit (2020), who find that more stable economic environments imply lower average unemployment rates. That is, the general downward trend in the unemployment rate after 1983 is consistent with theoretical models that show that the average unemployment rate can fall with a reduction in economic volatility. Return to 8

- See the notes to table 1 of https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcprojtabl20200916.pdf . Return to 9

- See https://www.nber.org/research/data/us-business-cycle-expansions-and-contractions for a list NBER peaks and troughs. Return to 10

- The NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee also uses gross domestic product, gross domestic income, personal consumption expenditures, and personal income less transfers when assigning business cycle peaks and troughs. For an example of the Business Cycle Dating Committee’s reasoning, see https://www.nber.org/news/business-cycle-dating-committee-announcement-june-8-2020 . Return to 11

- Consistent with this finding, Hall and Kudlyak (2020) document that the pace of reduction of the unemployment rate in expansions has been roughly stable for 70 years. Additionally, figure 2 implies that the pace of unemployment rate increases in recessions has also been roughly stable for 70 years. Return to 12

- Separating trends and business cycles is challenging for a wide variety of economic indicators. For example, Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Ulate (2018) show that the Congressional Budget Office has historically made large changes to its measure of potential output around recessions. Return to 13

- I use the conditional forecasting approach in Doan, Litterman, and Sims (1983). I provide details of the VAR and the conditional forecasting exercise in a supplemental appendix. Return to 14

- Mathematically, these initial conditions are the values of the right-hand side variables in the VAR that are needed to produce the forecasts. See the supplemental appendix for additional details. Return to 15

- I exclude the expansion that began in August 1980 because this expansion lasted only one year. Return to 16

- I choose 20 years because that is the horizon at which forecasts appear to converge for all of the initial conditions in figure 4. If I only use a 15-year forecast horizon, the November 1982 and June 2009 initial conditions yield forecasts of the unemployment that fall to 3.8 percent, but it does not fall all the way to 3.6 percent as shown in figure 4. If I use horizons of 25 or 30 years, then the unemployment rate falls to 3.6 percent for all the initial conditions shown in figure 4, but it does not fall further. Return to 17

- This finding uses a VAR with 6 lags and is sensitive to the number of lags included in the VAR. I have checked lag lengths from 1 to 13 and found that the 20-year unemployment rate projection varies from a low of about 2.9 percent (with 13 lags) to a high of about 3.7 percent (with 1 lag). Hence, the results that I provide are conservative in the sense that different lag choices may yield materially lower unemployment rate projections, but none yields materially higher unemployment rate projections. Return to 18

- This long-run projection of 3.6 percent is very similar to Hall and Kudlyak’s (2020) steady-state unemployment rate of 3.5 percent. Hence, my results provide empirical support for Hall and Kudlyak’s choice of a steady state. In contrast, my long-run projection is materially above the steady-state of Dupraz, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2019), which is 4.6 percent. In addition, the conditional forecasts that I produce can provide data moments that may help researchers estimate labor market congestion functions as in Section 5.3 of Hall and Kudlyak (2020). Return to 19

- Coibion, Olivier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Mauricio Ulate. 2018. “The Cyclical Sensitivity in Estimates of Potential Output.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Fall: 343–411. https://www.doi.org/10.1353/eca.2018.0020 .

- Crump, Richard K., Stefano Eusepi, Marc Giannoni, and Ayşegül Șahin. 2019. “A Unified Approach to Measuring u*.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity , Spring: 143–214. https://www.doi.org/10.1353/eca.2019.0002 .

- Doan, Thomas, Robert Litterman, and Christopher A. Sims. 1983. “Forecasting and Conditional Projection Using Realistic Prior Distributions.” NBER Working Paper, No. 1202. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w1202 .

- Dupraz, Stéphane, Emi Nakamura, and Jón Steinsson. 2019. “A Plucking Model of Business Cycles.” NBER Working Paper, No. 26351. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w26351 .

- Hall, Robert E., and Marianna Kudlyak. 2020. “Why Has the US Economy Recovered So Consistently from Every Recession in the Past 70 Years?” NBER Working Paper No. 27234. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w27234 .

- Hodrick, Robert J., and Edward C. Prescott. 1997. “Postwar US Business Cycles: An Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking , 29(1): 1–16. https://www.doi.org/10.2307/2953682 .

- Kim, Chang-Jin, and Charles R. Nelson. 1999. “Has the US Economy Become More Stable? A Bayesian Approach Based on a Markov

- Switching Model of the Business Cycle.” Review of Economics and Statistics , 81(4): 608–616. https://www.doi.org/10.1162/003465399558472 .

- Lepetit, Antoine, 2020. “Asymmetric Unemployment Fluctuations and Monetary Policy Trade-Offs.” Review of Economic Dynamic s, 36: 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2019.07.005 .

- McConnell, Margaret M., and Gabriel Perez-Quirós. 2000. “Output Fluctuations in the United States: What Has Changed since the Early 1980s?” American Economic Review , 90(5): 1464–1476. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.5.1464 .

- Müller, Ulrich K. and Mark W. Watson, 2015. “Low-Frequency Econometrics.” NBER Working Paper, No. 21564. https://www.doi.org/10.3386/w21564 .

- Neftçi, Salih N. 1984. “Are Economic Time Series Asymmetric over the Business Cycle?” Journal of Political Economy , 92(2): 307–328. https://www.doi.org/10.1086/261226 .

- Rogerson, Richard, and Robert Shimer. 2011. “Search in Macroeconomic Models of the Labor Market.” Handbook of Labor Economics , Volume 4a, Chapter 7, 619-700. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7218(11)00413-8 .

- Sichel, Daniel E. 1993. “Business Cycle Asymmetry: A Deeper Look.” Economic Inquiry , 31(2): 224–236. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1993.tb00879.x .

- Stock, James H., and Mark W. Watson. 2002. “Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?” NBER Macroeconomics Annual , 17: 159–218. https://www.doi.org/10.1086/ma.17.3585284 .

- Weiner, Stuart E. 1993. “New Estimates of the Natural Rate of Unemployment.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review , Fourth Quarter: 53–63. https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedker/y1993iqivp53-69nv.78no.4.html .

Suggested Citation

Lunsford, Kurt G. 2021. “Recessions and the Trend in the US Unemployment Rate.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary 2021-01. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202101

The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends

Following early 2020 responses to the pandemic, labor force participation declined dramatically and has remained below its 2019 level, whereas the unemployment rate recovered briskly. We estimate the trend of labor force participation and unemployment and find a substantial impact of the pandemic on estimates of trend. It turns out that levels of labor force participation and unemployment in 2021 were approaching their estimated trends. A return to 2019 levels would then represent a tight labor market, especially relative to long-run demographic trends that suggest further declines in the participation rate.

At the end of 2019, the labor market was hotter than it had been in years. Unemployment was at a historic low, and participation in the labor market was finally increasing after a prolonged decline. That tight labor market came to an abrupt halt with the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020.

Now, two years later, the labor market has mostly recovered from the depths of the pandemic recession. The unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic lows, and job openings are at record highs. Yet, participation and employment rates have remained persistently below pre-pandemic levels. This suggests the possibility that the pandemic has permanently reduced participation in the economy and that current participation rates reflect a new normal. In this article, we explore how the pandemic has affected labor markets and whether a new normal is emerging.

What Is "Normal"?

One way to define the normal level of a variable is to estimate its trend and compare the observed data with the estimated trend values. Constructing a trend essentially means drawing a smooth line through the variations in the actual data.

But this means that constructing the trend for a point in time typically involves considering what happened both before and after that point in time. Thus, constructing the trend at the end of a sample is especially hard, since we do not yet know how the data will evolve.

We construct trends for three aggregate labor market ratios — the labor force participation (LFP) rate, the unemployment rate and the employment-population ratio (EPOP) — using methods described in our 2019 article " Projecting Unemployment and Demographic Trends ."

First, we estimate statistical models for LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups defined by age, gender and education. For each gender and education, we decompose its unemployment and LFP into cyclical components common to all age groups and smooth local trends for age and cohort effects.

Second, we aggregate trends from the estimates of the group-specific trends. Specifically, we construct the trend for the aggregate LFP rate as the population-share-weighted sum of the corresponding estimated trends for demographic groups. We construct the aggregate unemployment rate and EPOP trends from the group-specific LFP and unemployment trends and the groups' population shares.

In our previous work, we estimated the trends for the unemployment rate and LFP rate of a gender-education group separately using maximum likelihood methods. The estimates reported in this article are based on the joint estimation of LFP and unemployment rate trends using Bayesian methods.

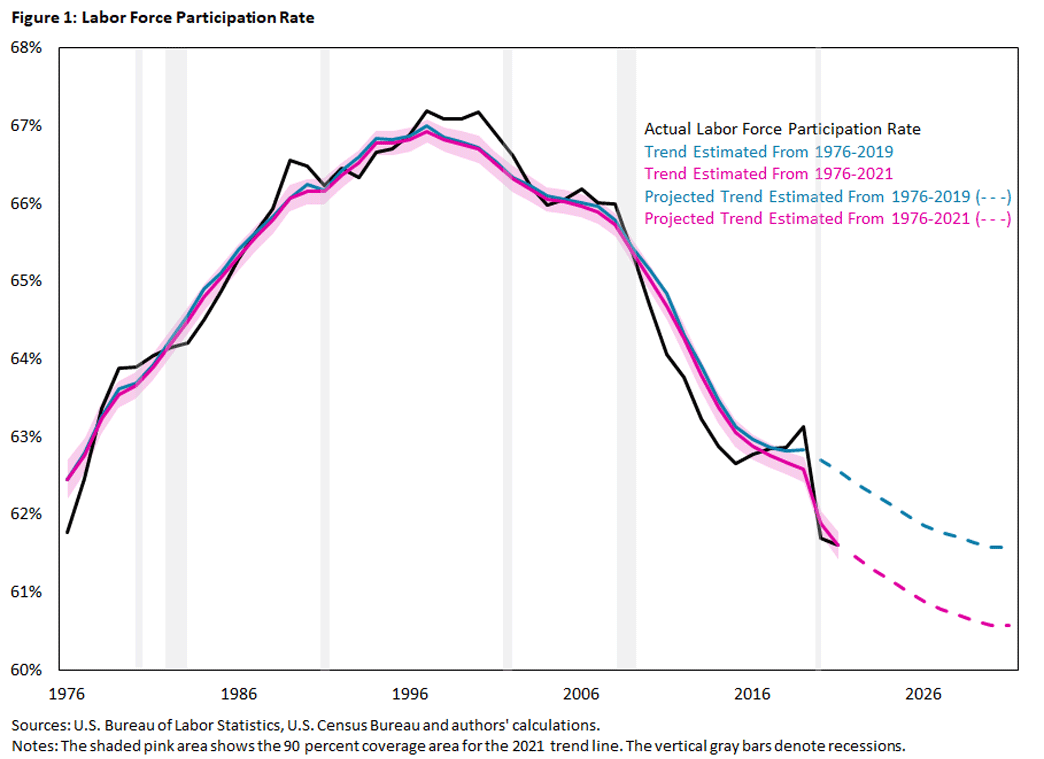

We separately estimate the trends using data from 1976 to 2019 (pre-pandemic) and from 1976 to 2021 (including the pandemic period). Figures 1, 2 and 3 display annual averages for the three aggregate labor market ratios — the LFP rate, the unemployment rate and EPOP, respectively — from 1976 to 2021.

In each figure, the solid black line denotes the observed values, and the blue and pink lines denote the estimated trend using data from 1976 up to and including 2019 and 2021, respectively. The estimated trends are subject to uncertainty, and the plotted trends represent the median estimate of the trend.

For the estimates based on data up to 2021, we also include the 90 percent coverage area shown as the shaded pink area. According to the statistical model, there is a 90 percent probability that the trend is contained in the coverage area. The blue and pink dotted lines represent our projections on how the labor market ratios will evolve until 2031, again based on the estimated trend up to and including 2019 and 2021. The shaded gray vertical areas highlight recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Pre-Pandemic Trends: 1976-2019

We start with the pre-pandemic trends for the LFP rate and unemployment rate estimated for data from 1976 through 2019. After a long recovery from the 2007-09 recession, the LFP rate was 63.1 percent in 2019 (slightly above the estimated trend value of 62.8 percent), and the unemployment rate was 3.7 percent (noticeably below its estimated trend value of 4.7 percent).

The LFP rate being above trend and the unemployment rate being below trend reflects the characterization of the 2019 labor market as "hot." But note that even though the LFP rate exceeded its trend value in 2019, it was still lower than during the 2007-09 period. This difference is accounted for by the declining trend in the LFP rate.

As noted in our 2019 article , LFP rates and unemployment rates differ systematically across demographic groups. Participation rates tend to be higher for younger, more-educated workers and for men. Unemployment rates tend to be lower for men and for the older and more-educated population.

Thus, changes in the population composition over time — that is, the relative size of demographic groups — will affect the aggregate LFP and unemployment rates, in addition to changes in the LFP and unemployment rate trends of the demographic groups.

As also noted in our 2019 article, the hump-shaped trend of the aggregate LFP rate reflects a variety of forces:

- Prior to 1990, the aggregate LFP rate was boosted by an upward trend in the LFP rate of women. But after 1990, the LFP rate of women began declining. Combining this with declining trend LFP rates for other demographic groups has reduced the aggregate LFP rate.

- Changes in the age distribution had a limited impact prior to 2005, but the aging population since then has lowered the aggregate LFP rate substantially.

- Increasing educational attainment has contributed positively to aggregate LFP throughout the period.

The steady decline of the unemployment rate trend reflects mostly the contributions from an older and more-educated population and, to some extent, a decline in the trend unemployment rates of demographic groups.

Pre-Pandemic Expectations of Future LFP and Unemployment Trends

Our statistical model of smooth local trends for the LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups has the property that the best forecast for future trend values of demographic groups is their last estimated trend value. Thus, the model will only predict a change in the trend of aggregate ratios if the population shares of its constituent groups are changing.

We combine the U.S. Census Bureau population forecasts for the gender-age groups with an estimated statistical model of education shares for gender-age groups to forecast population shares of our demographic groups from 2020 to 2031 (the dotted blue lines in Figures 1 and 2).

As we can see, the changing demographics alone imply further reductions of 1 percentage point and 0.2 percentage points in the trend LFP rate and unemployment rate, respectively. This projection is driven by the forecasted aging of the population, which is only partially offset by the forecasted higher educational attainment.

Based on data up to 2019, the same aggregate LFP rates in 2021 as in 2019 would have represented a substantial cyclical deviation upward from the pre-pandemic trends.

It is notable that the unemployment rate is much more volatile relative to its trend than the LFP rate is. In other words, cyclical deviations from trend are much more pronounced for the unemployment rate than for the LFP rate.

In fact, in our estimation, the behavior of the unemployment rate determines the common cyclical component of both the unemployment rate and the LFP rate. Whereas the unemployment rate spikes in recessions, the LFP rate response is more muted and tends to lag recessions. This feature will be important for interpreting how the estimated trend LFP rate changed with the pandemic.

Finally, Figure 3 combines the information from the LFP rate and unemployment rate and plots actual and trend rates for EPOP. On the one hand, given the relatively small trend decline of the unemployment rate, the trend for EPOP mainly reflects the trend for the LFP rate and inherits its hump-shaped path and the projected decline over the next 10 years. On the other hand, EPOP inherits the volatility from the unemployment rate. In 2019, EPOP is notably above trend, by about 1 percentage point.

Unemployment and Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic

The behavior of unemployment resulting from the pandemic-induced recession was different from past recessions:

- The entire increase in unemployment between February and April 2020 was accounted for by the increase in unemployment from temporary layoffs. This differed from previous recessions, when a spike in permanent layoffs led the bulge of unemployment in the trough.

- The recovery started in May 2020, and the speed of recovery was also much faster than in previous recessions. After only seven months, unemployment declined by 8 percentage points.

- The behavior of the unemployment rate is reflected in the 2020 recession being the shortest NBER recession on record: It lasted for two months (March to April 2020).

To summarize, the runup and decline of the unemployment rate during the pandemic were unusually rapid, but the qualitative features were not that different from previous recessions after properly accounting for temporary layoffs, as noted in the 2020 working paper " The Unemployed With Jobs and Without Jobs . "

The decline in the LFP rate was sharp and persistent. The LFP rate dropped from 63.4 percent in February 2020 to 60.2 percent in April 2020, an unprecedented drop during such a short period of time. After a rebound to 61.7 percent in August 2020, the LFP rate essentially moved sideways and remained below 62 percent until the end of 2021.

The large drop in the aggregate LFP rate has been attributed to, among others:

- More people — especially women — leaving the labor force to care for children because of school closings or to care for relatives at increased health risk, as noted in the 2021 work " Assessing Five Statements About the Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women (PDF) " and the 2021 article " Caregiving for Children and Parental Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic "

- An increase in retirement due to health concerns, as noted in the 2021 working paper " How Has COVID-19 Affected the Labor Force Participation of Older Workers? "

- Generous pandemic income transfers and unemployment insurance programs, as noted in the 2021 article " COVID Transfers Dampening Employment Growth, but Not Necessarily a Bad Thing "

All of these factors might impact the participation trend, but by how much?

The Pandemic's Effect on Trend Estimates for LFP and Unemployment

The aggregate trend assessment for the LFP and unemployment rates has changed considerably as a result of 2020 and 2021. Repeating the estimation of trend and cycle for our demographic groups using data from 1976 up to 2021 yields the pink trend lines in Figures 1 and 2.

The updated trend estimates now put the positive cyclical gap in 2019 for LFP at 0.5 percentage points (rather than 0.3 percentage points) and the negative cyclical gap for the unemployment rate at 1.4 percentage points (rather than 1 percentage point). That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market in 2019 was even hotter than by the estimates from the 1976-2019 period.

In 2021, the actual LFP rate is essentially at trend, and the unemployment rate is only slightly above trend. That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market is relatively tight.

Notice that even though the new 2021 trend estimates for both the LFP and the unemployment rates differ noticeably from the trend values predicted for 2021 based on data up to 2019, the trend revisions for the LFP rate are limited to more recent years, whereas the trend revisions for the unemployment rate apply to the whole sample.

The difference in revisions is related to how confident we can be about the estimated trends. The 90 percent coverage area is quite narrow for the LFP rate for the entire sample up to the last four years. Thus, there is no need to drastically revise the estimated trend prior to 2017.

On the other hand, the 90 percent coverage area for the trend unemployment rate is quite broad throughout the sample. That is, a wide range of values for trend unemployment is potentially consistent with observed unemployment values. Consequently, the last two observations lead to a wholesale reassessment of the level of the trend unemployment rate.

Another way to frame the 2020-21 trend revisions is as follows. The unemployment rate is very cyclical, deviations from trend are large, and though the sharp increase and decline of the unemployment rate in 2020-21 is unusual, an upward level shift of the trend unemployment rate best reflects the additional pandemic data.

The LFP rate, however, is usually not very cyclical, and it is only weakly related to the unemployment rate. Since the model assumes that the cyclical response does not change over the sample, it then attributes the large 2020-21 drop of the LFP rate to a decline in its trend and ultimately to a decline of the trend LFP rates of most demographic groups.

Finally, the EPOP trend is again mainly determined by the LFP trend, seen in Figure 3. Including the pandemic years noticeably lowers the estimated trend for the years from 2017 onwards. The cyclical gap in 2019 is now estimated to be 1.4 percentage points, and 2021 EPOP is close to its estimated trend.

What Does the Future Hold?

In our framework, current estimates of trend LFP and the unemployment rate for demographic groups are the best forecasts of future rates. Combined with projected demographic changes, this implies a continued noticeable downward trend for the LFP rate and a slight downward trend for the unemployment rate.

The trend unemployment rate is low, independent of how we estimate the trend. But given the highly unusual circumstances of the pandemic, the model may well overstate the decline in the trend LFP rate. Therefore, it is likely that the "true" trend lies somewhere between the trends estimated using data up to 2019 and data up to 2021.

That being a possibility, it remains that labor markets as of now have been unusually tight by most other measures, such as nominal wage growth and posted job openings relative to hires. This suggests that the true trend is closer to the revised 2021 trend than to the 2019 trend. In other words, the LFP rate and unemployment rate at the end of 2021 relative to the 2021 estimate of trend LFP and unemployment rate are consistent with a tight labor market.

Andreas Hornstein is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Marianna Kudlyak is a research advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Hornstein, Andreas; and Kudlyak, Marianna. (April 2022) "The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief , No. 22-12.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

V iews expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Subscribe to Economic Brief

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.

Thank you for signing up!

As a new subscriber, you will need to confirm your request to receive email notifications from the Richmond Fed. Please click the confirm subscription link in the email to activate your request.

If you do not receive a confirmation email, check your junk or spam folder as the email may have been diverted.

Phone Icon Contact Us

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 08 March 2018

Unemployment among younger and older individuals: does conventional data about unemployment tell us the whole story?

- Hila Axelrad 1 , 2 ,

- Miki Malul 3 &

- Israel Luski 4

Journal for Labour Market Research volume 52 , Article number: 3 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

71k Accesses

31 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

In this research we show that workers aged 30–44 were significantly more likely than those aged 45–59 to find a job a year after being unemployed. The main contribution is demonstrating empirically that since older workers’ difficulties are related to their age, while for younger individuals the difficulties are more related to the business cycle, policy makers must devise different programs to address unemployment among young and older individuals. The solution to youth unemployment is the creation of more jobs, and combining differential minimum wage levels and earned income tax credits might improve the rate of employment for older individuals.

1 Introduction

Literature about unemployment references both the unemployment of older workers (ages 45 or 50 and over) and youth unemployment (15–24). These two phenomena differ from one another in their characteristics, scope and solutions.

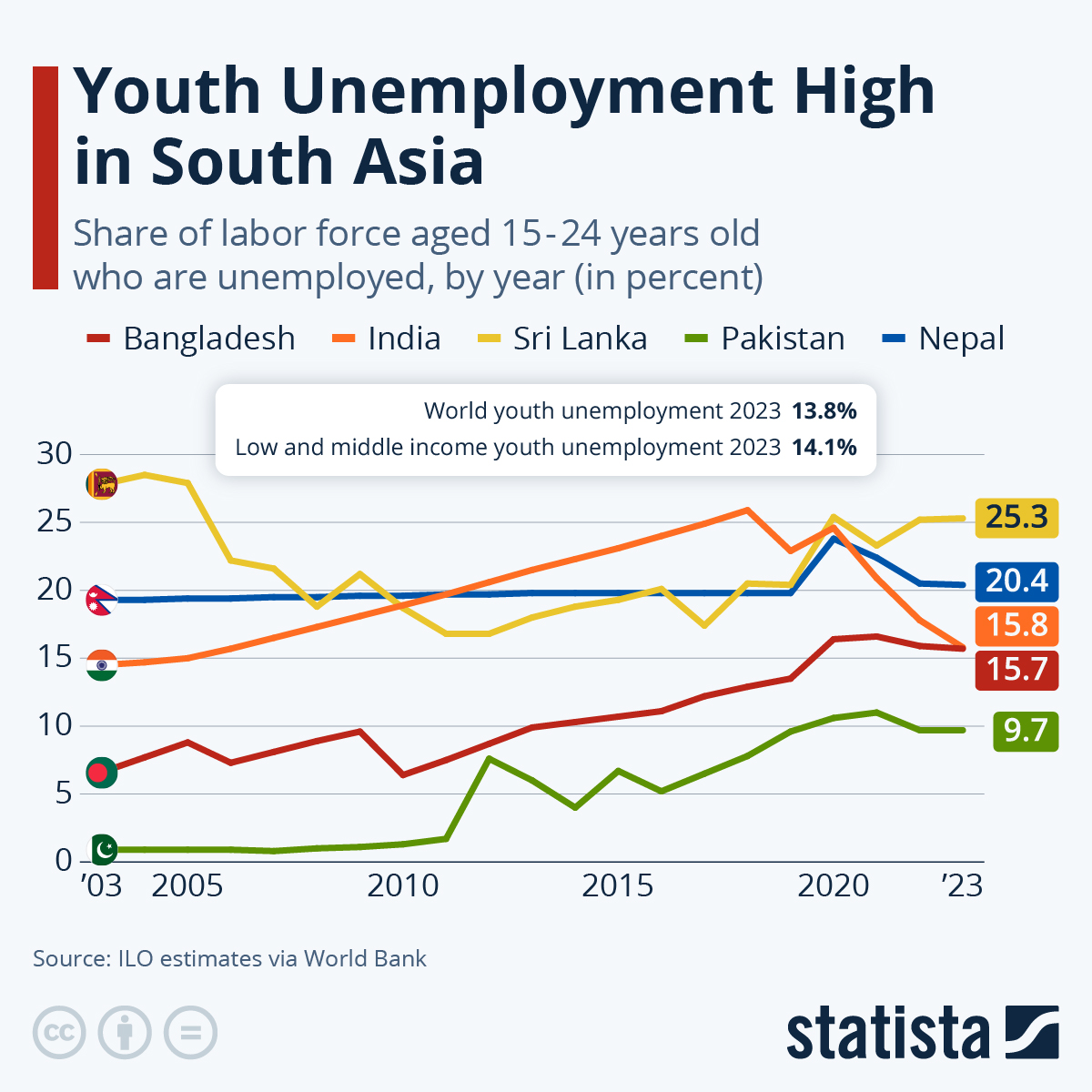

Unemployment among young people begins when they are eligible to work. According to the International Labor Office (ILO), young people are increasingly having trouble when looking for their first job (ILO 2011 ). The sharp increase in youth unemployment and underemployment is rooted in long-standing structural obstacles that prevent many youngsters in both OECD countries and emerging economies from making a successful transition from school to work. Not all young people face the same difficulties in gaining access to productive and rewarding jobs, and the extent of these difficulties varies across countries. Nevertheless, in all countries, there is a core group of young people facing various combinations of high and persistent unemployment, poor quality jobs when they do find work and a high risk of social exclusion (Keese et al. 2013 ). The rate of youth unemployment is much higher than that of adults in most countries of the world (ILO 2011 ; Keese et al. 2013 ; O’Higgins 1997 ; Morsy 2012 ). Official youth unemployment rates in the early decade of the 2010s ranged from under 10% in Germany to around 50% in Spain ( http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?v=2229 ; Pasquali 2012 ). The youngest employees, typically the newest, are more likely to be let go compared to older employees who have been in their jobs for a long time and have more job experience and job security (Furlong et al. 2012 ). However, although unemployment rates among young workers are relatively higher than those of older people, the period of time they spend unemployed is generally shorter than that of older adults (O’Higgins 2001 ).

We would like to argue that one of the most important determinants of youth unemployment is the economy’s rate of growth. When the aggregate level of economic activity and the level of adult employment are high, youth employment is also high. Footnote 1 Quantitatively, the employment of young people appears to be one of the most sensitive variables in the labor market, rising substantially during boom periods and falling substantially during less active periods (Freeman and Wise 1982 ; Bell and Blanchflower 2011 ; Dietrich and Möller 2016 ). Several explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. First, youth unemployment might be caused by insufficient skills of young workers. Another reason is a fall in aggregate demand, which leads to a decline in the demand for labor in general. Young workers are affected more strongly than older workers by such changes in aggregate demand (O’Higgins 2001 ). Thus, our first research question is whether young adults are more vulnerable to economic shocks compared to their older counterparts.

Older workers’ unemployment is mainly characterized by difficulties in finding a new job for those who have lost their jobs (Axelrad et al. et al. 2013 ). This fact seems counter-intuitive because older workers have the experience and accumulated knowledge that the younger working population lacks. The losses to society and the individuals are substantial because life expectancy is increasing, the retirement age is rising in many countries, and people are generally in good health (Axelrad et al. 2013 ; Vodopivec and Dolenc 2008 ).

The difficulty that adults have in reintegrating into the labor market after losing their jobs is more severe than that of the younger unemployed. Studies show that as workers get older, the duration of their unemployment lengthens and the chances of finding a job decline (Böheim et al. 2011 ; De Coen et al. 2010 ). Therefore, our second research question is whether older workers’ unemployment stems from their age.

In this paper, we argue that the unemployment rates of young people and older workers are often misinterpreted. Even if the data show that unemployment rates are higher among young people, such statistics do not necessarily imply that it is harder for them to find a job compared to older individuals. We maintain that youth unemployment stems mainly from the characteristics of the labor market, not from specific attributes of young people. In contrast, the unemployment of older individuals is more related to their specific characteristics, such as higher salary expectations, higher labor costs and stereotypes about being less productive (Henkens and Schippers 2008 ; Keese et al. 2006 ). To test these hypotheses, we conduct an empirical analysis using statistics from the Israeli labor market and data published by the OECD. We also discuss some policy implications stemming from our results, specifically, a differential policy of minimum wages and earned income tax credits depending on the worker’s age.

Following the introduction and literary review, the next part of our paper presents the existing data about the unemployment rates of young people and adults in the OECD countries in general and Israel in particular. Than we present the research hypotheses and theoretical model, we describe the data, variables and methods used to test our hypotheses. The regression results are presented in Sect. 4 , the model of Business Cycle is presented in Sect. 5 , and the paper concludes with some policy implications, a summary and conclusions in Sect. 6 .

2 Literature review

Over the past 30 years, unemployment in general and youth unemployment in particular has been a major problem in many industrial societies (Isengard 2003 ). The transition from school to work is a rather complex and turbulent period. The risk of unemployment is greater for young people than for adults, and first jobs are often unstable and rather short-lived (Jacob 2008 ). Many young people have short spells of unemployment during their transition from school to work; however, some often get trapped in unemployment and risk becoming unemployed in the long term (Kelly et al. 2012 ).

Youth unemployment leads to social problems such as a lack of orientation and hostility towards foreigners, which in turn lead to increased social expenditures. At the societal level, high youth unemployment endangers the functioning of social security systems, which depend on a sufficient number of compulsory payments from workers in order to operate (Isengard 2003 ).

Workers 45 and older who have lost their jobs often encounter difficulties in finding a new job (Axelrad et al. 2013 ; Marmora and Ritter 2015 ) although today they are more able to work longer than in years past (Johnson 2004 ). In addition to the monetary rewards, work also offers mental and psychological benefits (Axelrad et al. 2016 ; Jahoda 1982 ; Winkelmann and Winkelmann 1998 ). Working at an older age may contribute to an individual’s mental acuity and provide a sense of usefulness.

On average, throughout the OECD, the hiring rate of workers aged 50 and over is less than half the rate for workers aged 25–49. The low re-employment rates among older job seekers reflect, among other things, the reluctance of employers to hire older workers. Lahey ( 2005 ) found evidence of age discrimination against older workers in labor markets. Older job applicants (aged 50 or older), are treated differently than younger applicants. A younger worker is more than 40% more likely to be called back for an interview compared to an older worker. Age discrimination is also reflected in the time it takes for older adults to find a job. Many workers aged 45 or 50 and older who have lost their jobs often encounter difficulties in finding a new job, even if they are physically and intellectually fit (Hendels 2008 ; Malul 2009 ). Despite the fact that older workers are considered to be more reliable (McGregor and Gray 2002 ) and to have better business ethics, they are perceived as less flexible or adaptable, less productive and having higher salary expectations (Henkens and Schippers 2008 ). Employers who hesitated in hiring older workers also mentioned factors such as wages and non-wage labor costs that rise more steeply with age and the difficulties firms may face in adjusting working conditions to meet the requirements of employment protection rules (Keese et al. 2006 ).

Thus, we have a paradox. On one hand, people live longer, the retirement age is rising, and older people in good health want or need to keep working. At the same time, employers seek more and more young workers all the time. This phenomenon might marginalize skilled and experience workers, and take away their ability to make a living and accrue pension rights. Thus, employers’ reluctance to hire older workers creates a cycle of poverty and distress, burdening the already overcrowded social institutions and negatively affecting the economy’s productivity and GDP (Axelrad et al. 2013 ).

2.1 OECD countries during the post 2008 crisis

The recent global economic crisis took an outsized toll on young workers across the globe, especially in advanced economies, which were hit harder and recovered more slowly than emerging markets and developing economies. Does this fact imply that the labor market in Spain and Portugal (with relatively high youth unemployment rates) is less “friendly” toward younger individuals than the labor market in Israel and Germany (with a relatively low youth unemployment rate)? Has the market in Spain and Portugal become less “friendly” toward young people during the last 4 years? We argue that the main factor causing the increasing youth unemployment rates in Spain and Portugal is the poor state of the economy in the last 4 years in these countries rather than a change in attitudes toward hiring young people.

OECD data indicate that adult unemployment is significantly lower than youth unemployment. The global economic crisis has hit young people very hard. In 2010, there were nearly 15 million unemployed youngsters in the OECD area, about four million more than at the end of 2007 (Scarpetta et al. 2010 ).

From an international perspective, and unlike other developed countries, Israel has a young age structure, with a high birthrate and a small fraction of elderly population. Israel has a mandatory retirement age, which differs for men (67) and women (62), and the labor force participation of older workers is relatively high (Stier and Endeweld 2015 ), therefore, we believe that Israel is an interesting case for studying.

The Israeli labor market is extremely flexible (e.g. hiring and firing are relatively easy), and mobile (workers can easily move between jobs) (Peretz 2016 ). Focusing on Israel’s labor market, we want to check whether this is true for older Israeli workers as well, and whether there is a difference between young and older workers.

The problem of unemployment among young people in Israel is less severe than in most other developed countries. This low unemployment rate is a result of long-term processes that have enabled the labor market to respond relatively quickly to changes in the economic environment and have reduced structural unemployment. Footnote 2 Furthermore, responsible fiscal and monetary policies, and strong integration into the global market have also promoted employment at all ages. With regard to the differences between younger and older workers in Israel, Stier and Endeweld ( 2015 ) determined that older workers, men and women alike, are indeed less likely to leave their jobs. This finding is similar to other studies showing that older workers are less likely to move from one employer to another. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median employee tenure is generally higher among older workers than younger ones (BLS 2014 ). Movement in and out of the labor market is highest among the youngest workers. However, these young people are re-employed quickly, while older workers have the hardest time finding jobs once they become unemployed. The Bank of Israel calculated the chances of unemployed people finding work between two consecutive quarters using a panel of the Labor Force Survey for the years 1996–2011. Their calculations show that since the middle of the last decade the chances of unemployed people finding a job between two consecutive quarters increased. Footnote 3 However, as noted earlier, as workers age, the duration of their unemployment lengthens. Prolonged unemployment erodes the human capital of the unemployed (Addison et al. 2004 ), which has a particularly deleterious effect on older workers. Thus, the longer the period of unemployment of older workers, the less likely they will find a job (Axelrad and Luski 2017 ). Nevertheless, as Fig. 1 shows, the rates of youth unemployment in Israel are higher than those of older workers.

(Source: Calculated by the authors by using data from the Labor Force survey of the Israeli CBS, 2011)

Unemployed persons and discouraged workers as percentages of the civilian labor force, by age group (Bank of Israel 2011 ). We excluded those living outside settled communities or in institutions. The percentages of discouraged workers are calculated from the civilian labor force after including them in it

We argue that the main reason for this situation is the status quo in the labor market, which is general and not specific to Israel. It applies both to older workers and young workers who have a job. The status quo is evident in the situation in which adults (and young people) already in the labor market manage to keep their jobs, making the entrance of new young people into the labor market more difficult. What we are witnessing is not evidence of a preference for the old over the young, but the maintaining of the status quo.

The rate of employed Israelis covered by collective bargaining agreements increases with age: up to age 35, the rate is less than one-quarter, and between 50 and 64 the rate reaches about one-half. In effect, in each age group between 25 and 60, there are about 100,000 covered employees, and the lower coverage rate among the younger ages derives from the natural growth in the cohorts over time (Bank of Israel 2013 ). The wave of unionization in recent years is likely to change only the age profile of the unionization rate and the decline in the share of covered people over the years, to the extent that it strengthens and includes tens of thousands more employees from the younger age groups. Footnote 4

The fact that the percentage of employees covered by collective agreement increases with age implies that there is a status quo effect. Older workers are protected by collective agreements, and it is hard to dismiss them (Culpepper 2002 ; Palier and Thelen 2010 ). However, young workers enter the workforce with individual contracts and are not protected, making it is easier to change their working conditions and dismiss them.

To complete the picture, Fig. 2 shows that the number of layoffs among adults is lower, possibly due to their protection under collective bargaining agreements.

(Source: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2008, data processed by the authors)

Dismissal of employees in Israel, by age. Percentage of total employed persons ages 20–75 and over including those dismissed

In order to determine the real difference between the difficulties of older versus younger individuals in finding work, we have to eliminate the effect of the status quo in the labor market. For example, if we removed all of the workers from the labor market, what would be the difference between the difficulties of older people versus younger individuals in finding work? In the next section we will analyze the probability of younger and older individuals moving from unemployment to employment when we control for the status quo. We will do so by considering only individuals who have not been employed at least part of the previous year.

3 Estimating the chances of finding a job and research hypotheses

Based on the literature and the classic premise that young workers are more vulnerable to economic shocks (ILO 2011 ), we posit that:

H 1 : The unemployment rate of young people stems mainly from the characteristics of the labor market and less from their personal attributes.

Based on the low hiring rate of older workers (OECD 2006 ) and the literature about age discrimination against older workers in labor markets (Axelrad et al. 2013 ; Lahey 2005 ), we hypothesis that:

H 2 : The difficulty face by unemployed older workers searching for a job stems mainly from their age and less from the characteristics of the labor market.