- Utility Menu

Jeffrey R. Wilson

Essays on hamlet.

Written as the author taught Hamlet every semester for a decade, these lightning essays ask big conceptual questions about the play with the urgency of a Shakespeare lover, and answer them with the rigor of a Shakespeare scholar. In doing so, Hamlet becomes a lens for life today, generating insights on everything from xenophobia, American fraternities, and religious fundamentalism to structural misogyny, suicide contagion, and toxic love.

Prioritizing close reading over historical context, these explorations are highly textual and highly theoretical, often philosophical, ethical, social, and political. Readers see King Hamlet as a pre-modern villain, King Claudius as a modern villain, and Prince Hamlet as a post-modern villain. Hamlet’s feigned madness becomes a window into failed insanity defenses in legal trials. He knows he’s being watched in “To be or not to be”: the soliloquy is a satire of philosophy. Horatio emerges as Shakespeare’s authorial avatar for meta-theatrical commentary, Fortinbras as the hero of the play. Fate becomes a viable concept for modern life, and honor a source of tragedy. The metaphor of music in the play makes Ophelia Hamlet’s instrument. Shakespeare, like the modern corporation, stands against sexism, yet perpetuates it unknowingly. We hear his thoughts on single parenting, sending children off to college, and the working class, plus his advice on acting and writing, and his claims to be the next Homer or Virgil. In the context of four centuries of Hamlet hate, we hear how the text draws audiences in, how it became so famous, and why it continues to captivate audiences.

At a time when the humanities are said to be in crisis, these essays are concrete examples of the mind-altering power of literature and literary studies, unravelling the ongoing implications of the English language’s most significant artistic object of the past millennium.

Publications

Why is Hamlet the most famous English artwork of the past millennium? Is it a sexist text? Why does Hamlet speak in prose? Why must he die? Does Hamlet depict revenge, or justice? How did the death of Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, transform into a story about a son dealing with the death of a father? Did Shakespeare know Aristotle’s theory of tragedy? How did our literary icon, Shakespeare, see his literary icons, Homer and Virgil? Why is there so much comedy in Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy? Why is love a force of evil in the play? Did Shakespeare believe there’s a divinity that shapes our ends? How did he define virtue? What did he think about psychology? politics? philosophy? What was Shakespeare’s image of himself as an author? What can he, arguably the greatest writer of all time, teach us about our own writing? What was his theory of literature? Why do people like Hamlet ? How do the Hamlet haters of today compare to those of yesteryears? Is it dangerous for our children to read a play that’s all about suicide?

These are some of the questions asked in this book, a collection of essays on Shakespeare’s Hamlet stemming from my time teaching the play every semester in my Why Shakespeare? course at Harvard University. During this time, I saw a series of bright young minds from wildly diverse backgrounds find their footing in Hamlet, and it taught me a lot about how Shakespeare’s tragedy works, and why it remains with us in the modern world. Beyond ghosts, revenge, and tragedy, Hamlet is a play about being in college, being in love, gender, misogyny, friendship, theater, philosophy, theology, injustice, loss, comedy, depression, death, self-doubt, mental illness, white privilege, overbearing parents, existential angst, international politics, the classics, the afterlife, and the meaning of it all.

These essays grow from the central paradox of the play: it helps us understand the world we live in, yet we don't really understand the text itself very well. For all the attention given to Hamlet , there’s no consensus on the big questions—how it works, why it grips people so fiercely, what it’s about. These essays pose first-order questions about what happens in Hamlet and why, mobilizing answers for reflections on life, making the essays both highly textual and highly theoretical.

Each semester that I taught the play, I would write a new essay about Hamlet . They were meant to be models for students, the sort of essay that undergrads read and write – more rigorous than the puff pieces in the popular press, but riskier than the scholarship in most academic journals. While I later added scholarly outerwear, these pieces all began just like the essays I was assigning to students – as short close readings with a reader and a text and a desire to determine meaning when faced with a puzzling question or problem.

The turn from text to context in recent scholarly books about Hamlet is quizzical since we still don’t have a strong sense of, to quote the title of John Dover Wilson’s 1935 book, What Happens in Hamlet. Is the ghost real? Is Hamlet mad, or just faking? Why does he delay? These are the kinds of questions students love to ask, but they haven’t been – can’t be – answered by reading the play in the context of its sources (recently addressed in Laurie Johnson’s The Tain of Hamlet [2013]), its multiple texts (analyzed by Paul Menzer in The Hamlets [2008] and Zachary Lesser in Hamlet after Q1 [2015]), the Protestant reformation (the focus of Stephen Greenblatt’s Hamlet in Purgatory [2001] and John E. Curran, Jr.’s Hamlet, Protestantism, and the Mourning of Contingency [2006]), Renaissance humanism (see Rhodri Lewis, Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness [2017]), Elizabethan political theory (see Margreta de Grazia, Hamlet without Hamlet [2007]), the play’s reception history (see David Bevington, Murder Most Foul: Hamlet through the Ages [2011]), its appropriation by modern philosophers (covered in Simon Critchley and Jamieson Webster’s The Hamlet Doctrine [2013] and Andrew Cutrofello’s All for Nothing: Hamlet’s Negativity [2014]), or its recent global travels (addressed, for example, in Margaret Latvian’s Hamlet’s Arab Journey [2011] and Dominic Dromgoole’s Hamlet Globe to Globe [2017]).

Considering the context and afterlives of Hamlet is a worthy pursuit. I certainly consulted the above books for my essays, yet the confidence that comes from introducing context obscures the sharp panic we feel when confronting Shakespeare’s text itself. Even as the excellent recent book from Sonya Freeman Loftis, Allison Kellar, and Lisa Ulevich announces Hamlet has entered “an age of textual exhaustion,” there’s an odd tendency to avoid the text of Hamlet —to grasp for something more firm—when writing about it. There is a need to return to the text in a more immediate way to understand how Hamlet operates as a literary work, and how it can help us understand the world in which we live.

That latter goal, yes, clings nostalgically to the notion that literature can help us understand life. Questions about life send us to literature in search of answers. Those of us who love literature learn to ask and answer questions about it as we become professional literary scholars. But often our answers to the questions scholars ask of literature do not connect back up with the questions about life that sent us to literature in the first place—which are often philosophical, ethical, social, and political. Those first-order questions are diluted and avoided in the minutia of much scholarship, left unanswered. Thus, my goal was to pose questions about Hamlet with the urgency of a Shakespeare lover and to answer them with the rigor of a Shakespeare scholar.

In doing so, these essays challenge the conventional relationship between literature and theory. They pursue a kind of criticism where literature is not merely the recipient of philosophical ideas in the service of exegesis. Instead, the creative risks of literature provide exemplars to be theorized outward to help us understand on-going issues in life today. Beyond an occasion for the demonstration of existing theory, literature is a source for the creation of new theory.

Chapter One How Hamlet Works

Whether you love or hate Hamlet , you can acknowledge its massive popularity. So how does Hamlet work? How does it create audience enjoyment? Why is it so appealing, and to whom? Of all the available options, why Hamlet ? This chapter entertains three possible explanations for why the play is so popular in the modern world: the literary answer (as the English language’s best artwork about death—one of the very few universal human experiences in a modern world increasingly marked by cultural differences— Hamlet is timeless); the theatrical answer (with its mixture of tragedy and comedy, the role of Hamlet requires the best actor of each age, and the play’s popularity derives from the celebrity of its stars); and the philosophical answer (the play invites, encourages, facilitates, and sustains philosophical introspection and conversation from people who do not usually do such things, who find themselves doing those things with Hamlet , who sometimes feel embarrassed about doing those things, but who ultimately find the experience of having done them rewarding).

Chapter Two “It Started Like a Guilty Thing”: The Beginning of Hamlet and the Beginning of Modern Politics

King Hamlet is a tyrant and King Claudius a traitor but, because Shakespeare asked us to experience the events in Hamlet from the perspective of the young Prince Hamlet, we are much more inclined to detect and detest King Claudius’s political failings than King Hamlet’s. If so, then Shakespeare’s play Hamlet , so often seen as the birth of modern psychology, might also tell us a little bit about the beginnings of modern politics as well.

Chapter Three Horatio as Author: Storytelling and Stoic Tragedy

This chapter addresses Horatio’s emotionlessness in light of his role as a narrator, using this discussion to think about Shakespeare’s motives for writing tragedy in the wake of his son’s death. By rationalizing pain and suffering as tragedy, both Horatio and Shakespeare were able to avoid the self-destruction entailed in Hamlet’s emotional response to life’s hardships and injustices. Thus, the stoic Horatio, rather than the passionate Hamlet who repeatedly interrupts ‘The Mousetrap’, is the best authorial avatar for a Shakespeare who strategically wrote himself and his own voice out of his works. This argument then expands into a theory of ‘authorial catharsis’ and the suggestion that we can conceive of Shakespeare as a ‘poet of reason’ in contrast to a ‘poet of emotion’.

Chapter Four “To thine own self be true”: What Shakespeare Says about Sending Our Children Off to College

What does “To thine own self be true” actually mean? Be yourself? Don’t change who you are? Follow your own convictions? Don’t lie to yourself? This chapter argues that, if we understand meaning as intent, then “To thine own self be true” means, paradoxically, that “the self” does not exist. Or, more accurately, Shakespeare’s Hamlet implies that “the self” exists only as a rhetorical, philosophical, and psychological construct that we use to make sense of our experiences and actions in the world, not as anything real. If this is so, then this passage may offer us a way of thinking about Shakespeare as not just a playwright but also a moral philosopher, one who did his ethics in drama.

Chapter Five In Defense of Polonius

Your wife dies. You raise two children by yourself. You build a great career to provide for your family. You send your son off to college in another country, though you know he’s not ready. Now the prince wants to marry your daughter—that’s not easy to navigate. Then—get this—while you’re trying to save the queen’s life, the prince murders you. Your death destroys your kids. They die tragically. And what do you get for your efforts? Centuries of Shakespeare scholars dumping on you. If we see Polonius not through the eyes of his enemy, Prince Hamlet—the point of view Shakespeare’s play asks audiences to adopt—but in analogy to the common challenges of twenty-first-century parenting, Polonius is a single father struggling with work-life balance who sadly choses his career over his daughter’s well-being.

Chapter Six Sigma Alpha Elsinore: The Culture of Drunkenness in Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Claudius likes to party—a bit too much. He frequently binge drinks, is arguably an alcoholic, but not an aberration. Hamlet says Denmark is internationally known for heavy drinking. That’s what Shakespeare would have heard in the sixteenth century. By the seventeenth, English writers feared Denmark had taught their nation its drinking habits. Synthesizing criticism on alcoholism as an individual problem in Shakespeare’s texts and times with scholarship on national drinking habits in the early-modern age, this essay asks what the tragedy of alcoholism looks like when located not on the level of the individual, but on the level of a culture, as Shakespeare depicted in Hamlet. One window into these early-modern cultures of drunkenness is sociological studies of American college fraternities, especially the social-learning theories that explain how one person—one culture—teaches another its habits. For Claudius’s alcoholism is both culturally learned and culturally significant. And, as in fraternities, alcoholism in Hamlet is bound up with wealth, privilege, toxic masculinity, and tragedy. Thus, alcohol imagistically reappears in the vial of “cursed hebona,” Ophelia’s liquid death, and the poisoned cup in the final scene—moments that stand out in recent performances and adaptations with alcoholic Claudiuses and Gertrudes.

Chapter Seven Tragic Foundationalism

This chapter puts the modern philosopher Alain Badiou’s theory of foundationalism into dialogue with the early-modern playwright William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet . Doing so allows us to identify a new candidate for Hamlet’s traditionally hard-to-define hamartia – i.e., his “tragic mistake” – but it also allows us to consider the possibility of foundationalism as hamartia. Tragic foundationalism is the notion that fidelity to a single and substantive truth at the expense of an openness to evidence, reason, and change is an acute mistake which can lead to miscalculations of fact and virtue that create conflict and can end up in catastrophic destruction and the downfall of otherwise strong and noble people.

Chapter Eight “As a stranger give it welcome”: Shakespeare’s Advice for First-Year College Students

Encountering a new idea can be like meeting a strange person for the first time. Similarly, we dismiss new ideas before we get to know them. There is an answer to the problem of the human antipathy to strangeness in a somewhat strange place: a single line usually overlooked in William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet . If the ghost is “wondrous strange,” Hamlet says, invoking the ancient ethics of hospitality, “Therefore as a stranger give it welcome.” In this word, strange, and the social conventions attached to it, is both the instinctual, animalistic fear and aggression toward what is new and different (the problem) and a cultivated, humane response in hospitality and curiosity (the solution). Intellectual xenia is the answer to intellectual xenophobia.

Chapter Nine Parallels in Hamlet

Hamlet is more parallely than other texts. Fortinbras, Hamlet, and Laertes have their fathers murdered, then seek revenge. Brothers King Hamlet and King Claudius mirror brothers Old Norway and Old Fortinbras. Hamlet and Ophelia both lose their fathers, go mad, but there’s a method in their madness, and become suicidal. King Hamlet and Polonius are both domineering fathers. Hamlet and Polonius are both scholars, actors, verbose, pedantic, detectives using indirection, spying upon others, “by indirections find directions out." King Hamlet and King Claudius are both kings who are killed. Claudius using Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to spy on Hamlet mirrors Polonius using Reynaldo to spy on Laertes. Reynaldo and Hamlet both pretend to be something other than what they are in order to spy on and detect foes. Young Fortinbras and Prince Hamlet both have their forward momentum “arrest[ed].” Pyrrhus and Hamlet are son seeking revenge but paused a “neutral to his will.” The main plot of Hamlet reappears in the play-within-the-play. The Act I duel between King Hamlet and Old Fortinbras echoes in the Act V duel between Hamlet and Laertes. Claudius and Hamlet are both king killers. Sheesh—why are there so many dang parallels in Hamlet ? Is there some detectable reason why the story of Hamlet would call for the literary device of parallelism?

Chapter Ten Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: Why Hamlet Has Two Childhood Friends, Not Just One

Why have two of Hamlet’s childhood friends rather than just one? Do Rosencrantz and Guildenstern have individuated personalities? First of all, by increasing the number of friends who visit Hamlet, Shakespeare creates an atmosphere of being outnumbered, of multiple enemies encroaching upon Hamlet, of Hamlet feeling that the world is against him. Second, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are not interchangeable, as commonly thought. Shakespeare gave each an individuated personality. Guildenstern is friendlier with Hamlet, and their friendship collapses, while Rosencrantz is more distant and devious—a frenemy.

Chapter Eleven Shakespeare on the Classics, Shakespeare as a Classic: A Reading of Aeneas’s Tale to Dido

Of all the stories Shakespeare might have chosen, why have Hamlet ask the players to recite Aeneas’ tale to Dido of Pyrrhus’s slaughter of Priam? In this story, which comes not from Homer’s Iliad but from Virgil’s Aeneid and had already been adapted for the Elizabethan stage in Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragedy of Dido, Pyrrhus – more commonly known as Neoptolemus, the son of the famous Greek warrior Achilles – savagely slays Priam, the king of the Trojans and the father of Paris, who killed Pyrrhus’s father, Achilles, who killed Paris’s brother, Hector, who killed Achilles’s comrade, Patroclus. Clearly, the theme of revenge at work in this story would have appealed to Shakespeare as he was writing what would become the greatest revenge tragedy of all time. Moreover, Aeneas’s tale to Dido supplied Shakespeare with all of the connections he sought to make at this crucial point in his play and his career – connections between himself and Marlowe, between the start of Hamlet and the end, between Prince Hamlet and King Claudius, between epic poetry and tragic drama, and between the classical literature Shakespeare was still reading hundreds of years later and his own potential as a classic who might (and would) be read hundreds of years into the future.

Chapter Twelve How Theater Works, according to Hamlet

According to Hamlet, people who are guilty of a crime will, when seeing that crime represented on stage, “proclaim [their] malefactions”—but that simply isn’t how theater works. Guilty people sit though shows that depict their crimes all the time without being prompted to public confession. Why did Shakespeare—a remarkably observant student of theater—write this demonstrably false theory of drama into his protagonist? And why did Shakespeare then write the plot of the play to affirm that obviously inaccurate vision of theater? For Claudius is indeed stirred to confession by the play-within-the-play. Perhaps Hamlet’s theory of people proclaiming malefactions upon seeing their crimes represented onstage is not as outlandish as it first appears. Perhaps four centuries of obsession with Hamlet is the English-speaking world proclaiming its malefactions upon seeing them represented dramatically.

Chapter Thirteen “To be, or not to be”: Shakespeare Against Philosophy

This chapter hazards a new reading of the most famous passage in Western literature: “To be, or not to be” from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet . With this line, Hamlet poses his personal struggle, a question of life and death, as a metaphysical problem, as a question of existence and nothingness. However, “To be, or not to be” is not what it seems to be. It seems to be a representation of tragic angst, yet a consideration of the context of the speech reveals that “To be, or not to be” is actually a satire of philosophy and Shakespeare’s representation of the theatricality of everyday life. In this chapter, a close reading of the context and meaning of this passage leads into an attempt to formulate a Shakespearean image of philosophy.

Chapter Fourteen Contagious Suicide in and Around Hamlet

As in society today, suicide is contagious in Hamlet , at least in the example of Ophelia, the only death by suicide in the play, because she only becomes suicidal after hearing Hamlet talk about his own suicidal thoughts in “To be, or not to be.” Just as there are media guidelines for reporting on suicide, there are better and worse ways of handling Hamlet . Careful suicide coverage can change public misperceptions and reduce suicide contagion. Is the same true for careful literary criticism and classroom discussion of suicide texts? How can teachers and literary critics reduce suicide contagion and increase help-seeking behavior?

Chapter Fifteen Is Hamlet a Sexist Text? Overt Misogyny vs. Unconscious Bias

Students and fans of Shakespeare’s Hamlet persistently ask a question scholars and critics of the play have not yet definitively answered: is it a sexist text? The author of this text has been described as everything from a male chauvinist pig to a trailblazing proto-feminist, but recent work on the science behind discrimination and prejudice offers a new, better vocabulary in the notion of unconscious bias. More pervasive and slippery than explicit bigotry, unconscious bias involves the subtle, often unintentional words and actions which indicate the presence of biases we may not be aware of, ones we may even fight against. The Shakespeare who wrote Hamlet exhibited an unconscious bias against women, I argue, even as he sought to critique the mistreatment of women in a patriarchal society. The evidence for this unconscious bias is not to be found in the misogynistic statements made by the characters in the play. It exists, instead, in the demonstrable preference Shakespeare showed for men over women when deciding where to deploy his literary talents. Thus, Shakespeare's Hamlet is a powerful literary example – one which speaks to, say, the modern corporation – showing that deliberate efforts for egalitarianism do not insulate one from the effects of structural inequalities that both stem from and create unconscious bias.

Chapter Sixteen Style and Purpose in Acting and Writing

Purpose and style are connected in academic writing. To answer the question of style ( How should we write academic papers? ) we must first answer the question of purpose ( Why do we write academic papers? ). We can answer these questions, I suggest, by turning to an unexpected style guide that’s more than 400 years old: the famous passage on “the purpose of playing” in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet . In both acting and writing, a high style often accompanies an expressive purpose attempting to impress an elite audience yet actually alienating intellectual people, while a low style and mimetic purpose effectively engage an intellectual audience.

Chapter Seventeen 13 Ways of Looking at a Ghost

Why doesn’t Gertrude see the Ghost of King Hamlet in Act III, even though Horatio, Bernardo, Francisco, Marcellus, and Prince Hamlet all saw it in Act I? It’s a bit embarrassing that Shakespeare scholars don’t have a widely agreed-upon consensus that explains this really basic question that puzzles a lot of people who read or see Hamlet .

Chapter Eighteen The Tragedy of Love in Hamlet

The word “love” appears 84 times in Shakespeare’s Hamlet . “Father” only appears 73 times, “play” 60, “think” 55, “mother” 46, “mad” 44, “soul” 40, “God" 39, “death” 38, “life” 34, “nothing” 28, “son” 26, “honor” 21, “spirit” 19, “kill” 18, “revenge” 14, and “action” 12. Love isn’t the first theme that comes to mind when we think of Hamlet , but is surprisingly prominent. But love is tragic in Hamlet . The bloody catastrophe at the end of that play is principally driven not by hatred or a longing for revenge, but by love.

Chapter Nineteen Ophelia’s Songs: Moral Agency, Manipulation, and the Metaphor of Music in Hamlet

This chapter reads Ophelia’s songs in Act IV of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in the context of the meaning of music established elsewhere in the play. While the songs are usually seen as a marker of Ophelia’s madness (as a result of the death of her father) or freedom (from the constraints of patriarchy), they come – when read in light of the metaphor of music as manipulation – to symbolize her role as a pawn in Hamlet’s efforts to deceive his family. Thus, music was Shakespeare’s platform for connecting Ophelia’s story to one of the central questions in Hamlet : Do we have control over our own actions (like the musician), or are we controlled by others (like the instrument)?

Chapter Twenty A Quantitative Study of Prose and Verse in Hamlet

Why does Hamlet have so much prose? Did Shakespeare deliberately shift from verse to prose to signal something to his audiences? How would actors have handled the shifts from verse to prose? Would audiences have detected shifts from verse to prose? Is there an overarching principle that governs Shakespeare’s decision to use prose—a coherent principle that says, “If X, then use prose?”

Chapter Twenty-One The Fortunes of Fate in Hamlet : Divine Providence and Social Determinism

In Hamlet , fate is attacked from both sides: “fortune” presents a world of random happenstance, “will” a theory of efficacious human action. On this backdrop, this essay considers—irrespective of what the characters say and believe—what the structure and imagery Shakespeare wrote into Hamlet say about the possibility that some version of fate is at work in the play. I contend the world of Hamlet is governed by neither fate nor fortune, nor even the Christianized version of fate called “providence.” Yet there is a modern, secular, disenchanted form of fate at work in Hamlet—what is sometimes called “social determinism”—which calls into question the freedom of the individual will. As such, Shakespeare’s Hamlet both commented on the transformation of pagan fate into Christian providence that happened in the centuries leading up to the play, and anticipated the further transformation of fate from a theological to a sociological idea, which occurred in the centuries following Hamlet .

Chapter Twenty-Two The Working Class in Hamlet

There’s a lot for working-class folks to hate about Hamlet —not just because it’s old, dusty, difficult to understand, crammed down our throats in school, and filled with frills, tights, and those weird lace neck thingies that are just socially awkward to think about. Peak Renaissance weirdness. Claustrophobicly cloistered inside the castle of Elsinore, quaintly angsty over royal family problems, Hamlet feels like the literary epitome of elitism. “Lawless resolutes” is how the Wittenberg scholar Horatio describes the soldiers who join Fortinbras’s army in exchange “for food.” The Prince Hamlet who has never worked a day in his life denigrates Polonius as a “fishmonger”: quite the insult for a royal advisor to be called a working man. And King Claudius complains of the simplicity of "the distracted multitude.” But, in Hamlet , Shakespeare juxtaposed the nobles’ denigrations of the working class as readily available metaphors for all-things-awful with the rather valuable behavior of working-class characters themselves. When allowed to represent themselves, the working class in Hamlet are characterized as makers of things—of material goods and services like ships, graves, and plays, but also of ethical and political virtues like security, education, justice, and democracy. Meanwhile, Elsinore has a bad case of affluenza, the make-believe disease invented by an American lawyer who argued that his client's social privilege was so great that it created an obliviousness to law. While social elites rot society through the twin corrosives of political corruption and scholarly detachment, the working class keeps the machine running. They build the ships, plays, and graves society needs to function, and monitor the nuts-and-bolts of the ideals—like education and justice—that we aspire to uphold.

Chapter Twenty-Three The Honor Code at Harvard and in Hamlet

Students at Harvard College are asked, when they first join the school and several times during their years there, to affirm their awareness of and commitment to the school’s honor code. But instead of “the foundation of our community” that it is at Harvard, honor is tragic in Hamlet —a source of anxiety, blunder, and catastrophe. As this chapter shows, looking at Hamlet from our place at Harvard can bring us to see what a tangled knot honor can be, and we can start to theorize the difference between heroic and tragic honor.

Chapter Twenty-Four The Meaning of Death in Shakespeare’s Hamlet

By connecting the ways characters live their lives in Hamlet to the ways they die – on-stage or off, poisoned or stabbed, etc. – Shakespeare symbolized hamartia in catastrophe. In advancing this argument, this chapter develops two supporting ideas. First, the dissemination of tragic necessity: Shakespeare distributed the Aristotelian notion of tragic necessity – a causal relationship between a character’s hamartia (fault or error) and the catastrophe at the end of the play – from the protagonist to the other characters, such that, in Hamlet , those who are guilty must die, and those who die are guilty. Second, the spectacularity of death: there exists in Hamlet a positive correlation between the severity of a character’s hamartia (error or flaw) and the “spectacularity” of his or her death – that is, the extent to which it is presented as a visible and visceral spectacle on-stage.

Chapter Twenty-Five Tragic Excess in Hamlet

In Hamlet , Shakespeare paralleled the situations of Hamlet, Laertes, and Fortinbras (the father of each is killed, and each then seeks revenge) to promote the virtue of moderation: Hamlet moves too slowly, Laertes too swiftly – and they both die at the end of the play – but Fortinbras represents a golden mean which marries the slowness of Hamlet with the swiftness of Laertes. As argued in this essay, Shakespeare endorsed the virtue of balance by allowing Fortinbras to be one of the very few survivors of the play. In other words, excess is tragic in Hamlet .

Bibliography

Anand, Manpreet Kaur. An Overview of Hamlet Studies . Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2019.

Anglin, Emily. “‘Something in me dangerous’: Hamlet, Melancholy, and the Early Modern Scholar.” Shakespeare 13.1 (2017): 15-29.

Baker, Christopher. “Hamlet and the Kairos.” Ben Jonson Journal 26.1 (2019): 62-77.

Baker, Naomi. “‘Sore Distraction’: Hamlet, Augustine and Time.” Literature and Theology 32.4 (2018): 381-96.

Belsey, Catherine. “The Question of Hamlet.” The Oxford Handbook of Shakespearean Tragedy, ed. Michael Neill and David Schalkwyk (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016:

Bevington, David, ed. Twentieth Century Interpretations of Hamlet: A Collection of Critical Essays . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1968.

Bevington, David. Murder Most Foul: Hamlet through the Ages . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Bloom, Harold, ed. Modern Critical Interpretations: Hamlet . New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986.

Booth, Stephen. “On the Value of Hamlet.” Reinterpretations of Elizabethan Drama. Ed. By Norman Rabkin. New York: Columbia University Press, 1969. 137-76.

Bowers, Fredson. Hamlet as Minister and Scourge and Other Studies in Shakespeare and Milton. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1989.

Brancher, Dominique. “Universals in the Bush: The Case of Hamlet.” Shakespeare and Space: Theatrical Explorations of the Spatial Paradigm , ed. Ina Habermann and Michelle Witen (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016): 143-62.

Bourus, Terri. Young Shakespeare’s Young Hamlet: Print, Piracy, and Performance . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Bourus, Terri. Canonizing Q1 Hamlet . Special issue of Critical Survey 31.1-2 (2019).

Burnett, Mark Thornton. ‘Hamlet' and World Cinema . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Calderwood, James L. To Be and Not to Be: Negation and Metadrama in Hamlet . New York: Columbia, 1983.

Carlson, Marvin. Shattering Hamlet's Mirror: Theatre and Reality . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

Cavell, Stanley. “Hamlet’s Burden of Proof.” Disowning Knowledge in Seven Plays of Shakespeare . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. 179–91.

Chamberlain, Richard. “What's Happiness in Hamlet?” The Renaissance of Emotion: Understanding Affect in Shakespeare and his Contemporaries , ed. Richard Meek and Erin Sullivan (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017): 153-74.

Cormack, Bradin. “Paper Justice, Parchment Justice: Shakespeare, Hamlet, and the Life of Legal Documents.” Taking Exception to the Law: Materializing Injustice in Early Modern English Literature , ed. Donald Beecher, Travis Decook, and Andrew Wallace (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015): 44-70.

Craig, Leon Harold. Philosophy and the Puzzles of Hamlet: A Study of Shakespeare's Method . London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Critchley, Simon; Webster, Jamieson. Stay, Illusion!: The Hamlet Doctrine . New York: Pantheon Books, 2013.

Curran, John E., Jr. Hamlet, Protestantism, and the Mourning of Contingency: Not to Be . Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2006.

Cutrofello, Andrew. All for Nothing: Hamlet's Negativity . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2014.

Dawson, Anthony B. Hamlet: Shakespeare in Performance . Manchester and New York: Manchester UP, 1995.

Desmet, Christy. “Text, Style, and Author in Hamlet Q1.” Journal of Early Modern Studies 5 (2016): 135-156

Dodsworth, Martin. Hamlet Closely Observed . London: Athlone, 1985.

De Grazia, Margreta. Hamlet without Hamlet . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Dromgoole, Dominic. Hamlet: Globe to Globe : 193,000 Miles, 197 Countries, One Play . Edinburgh: Canongate, 2018.

Dunne, Derek. “Decentring the Law in Hamlet .” Law and Humanities 9.1 (2015): 55-77.

Eliot, T. S. “Hamlet and His Problems.” The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism . London: Methuen, 1920. 87–94.

Evans, Robert C., ed. Critical Insights: Hamlet . Amenia: Grey House Publishing, 2019.

Farley-Hills, David, ed. Critical Responses to Hamlet, 1600-1900 . 5 vols. New York: AMS Press, 1996.

Foakes, R.A. Hamlet Versus Lear: Cultural Politics and Shakespeare's Art . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Frank, Arthur W. “‘Who’s There?’: A Vulnerable Reading of Hamlet,” Literaature and Medicine 37.2 (2019): 396-419.

Frye, Roland Mushat. The Renaissance Hamlet: Issues and Responses in 1600 . Princeton: Princeton UP, 1984.

Josipovici, Gabriel. Hamlet: Fold on Fold . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Kastan, David Scott, ed. Critical Essays on Shakespeare’s Hamlet . New York: G. K. Hall, 1995.

Khan, Amir. “My Kingdom for a Ghost: Counterfactual Thinking and Hamlet.” Shakespeare Quarerly 66.1 (2015): 29-46.

Keener, Joe. “Evolving Hamlet: Brains, Behavior, and the Bard.” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 14.2 (2012): 150-163

Kott, Jan. “Hamlet of the Mid-Century.” Shakespeare, Our Contemporary . Trans. Boleslaw Taborski. Garden City: Doubleday, 1964.

Lake, Peter. Hamlet’s Choice: Religion and Resistance in Shakespeare's Revenge Tragedies . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020.

Lerer, Seth. “Hamlet’s Boyhood.” Childhood, Education and the Stage in Early Modern England , ed. Richard Preiss and Deanne Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017):17-36.

Levy, Eric P. Hamlet and the Rethinking of Man . Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2008.

Lewis, C.S. “Hamlet: The Prince or the Poem?” (1942). Studies in Shakespeare , ed. Peter Alexander (1964): 201-18.

Loftis, Sonya Freeman; Allison Kellar; and Lisa Ulevich, ed. Shakespeare's Hamlet in an Era of Textual Exhaustion . New York, NY: Routledge, 2018.

Luke, Jillian. “What If the Play Were Called Ophelia ? Gender and Genre in Hamlet .” Cambridge Quarterly 49.1 (2020): 1-18.

Gates, Sarah. “Assembling the Ophelia Fragments: Gender, Genre, and Revenge in Hamlet.” Explorations in Renaissance Culture 34.2 (2008): 229-47.

Gottschalk, Paul. The Meanings of Hamlet: Modes of Literary Interpretation Since Bradley . Albequerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1972.

Greenblatt, Stephen. Hamlet in Purgatory . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001.

Hunt, Marvin W. Looking for Hamlet . New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

Iyengar, Sujata. "Gertrude/Ophelia: Feminist Intermediality, Ekphrasis, and Tenderness in Hamlet," in Loomba, Rethinking Feminism In Early Modern Studies: Race, Gender, and Sexuality (2016), 165-84.

Iyengar, Sujata; Feracho, Lesley. “Hamlet (RSC, 2016) and Representations of Diasporic Blackness,” Cahiers Élisabéthains 99, no. 1 (2019): 147-60.

Johnson, Laurie. The Tain of Hamlet . Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2013.

Jolly, Margrethe. The First Two Quartos of Hamlet: A New View of the Origins and Relationship of the Texts . Jefferson: McFarland, 2014.

Jones, Ernest. Hamlet and Oedipus . Garden City: Doubleday, 1949.

Keegan, Daniel L. “Indigested in the Scenes: Hamlet's Dramatic Theory and Ours.” PMLA 133.1 (2018): 71-87.

Kinney, Arthur F., ed. Hamlet: Critical Essays . New York: Routledge, 2002.

Kiséry, András. Hamlet's Moment: Drama and Political Knowledge in Early Modern England . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Kottman, Paul A. “Why Think About Shakespearean Tragedy Today?” The Cambridge Companion to Shakespearean Tragedy , ed. Claire McEachern (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013): 240-61.

Langis, Unhae. “Virtue, Justice and Moral Action in Shakespeare’s Hamlet .” Literature and Ethics: From the Green Knight to the Dark Knight , ed. Steve Brie and William T. Rossiter (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010): 53-74.

Lawrence, Sean. "'As a stranger, bid it welcome': Alterity and Ethics in Hamlet and the New Historicism," European Journal of English Studies 4 (2000): 155-69.

Lesser, Zachary. Hamlet after Q1: An Uncanny History of the Shakespearean Text . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Levin, Harry. The Question of Hamlet . New York: Oxford UP, 1959.

Lewis, Rhodri. Hamlet and the Vision of Darkness . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Litvin, Margaret. Hamlet's Arab Journey: Shakespeare's Prince and Nasser's Ghost . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Loftis, Sonya Freeman, and Lisa Ulevich. “Obsession/Rationality/Agency: Autistic Shakespeare.” Disability, Health, and Happiness in the Shakespearean Body , edited by Sujata Iyengar. Routledge, 2015, pp. 58-75.

Marino, James J. “Ophelia’s Desire.” ELH 84.4 (2017): 817-39.

Massai, Sonia, and Lucy Munro. Hamlet: The State of Play . London: Bloomsbury, 2021.

McGee, Arthur. The Elizabethan Hamlet . New Haven: Yale UP, 1987.

Megna, Paul, Bríd Phillips, and R.S. White, ed. Hamlet and Emotion . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Menzer, Paul. The Hamlets: Cues, Qs, and Remembered Texts . Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008.

Mercer, Peter. Hamlet and the Acting of Revenge . Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1987.

Oldham, Thomas A. “Unhouseled, Disappointed, Unaneled”: Catholicism, Transubstantiation, and Hamlet .” Ecumenica 8.1 (Spring 2015): 39-51.

Owen, Ruth J. The Hamlet Zone: Reworking Hamlet for European Cultures . Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2012.

Price, Joeseph G., ed. Hamlet: Critical Essays . New York: Routledge, 1986.

Prosser, Eleanor. Hamlet and Revenge . 2nd ed. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1971.

Rosenberg, Marvin. The Masks of Hamlet . Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1992.

Row-Heyveld, Lindsey. “Antic Dispositions: Mental and Intellectual Disabilities in Early Modern Revenge Tragedy.” Recovering Disability in Early Modern England , ed. Allison P. Hobgood and David Houston Wood. Ohio State University Press, 2013, pp. 73-87.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet . Ed. Neil Taylor and Ann Thompson. Revised Ed. London: Arden Third Series, 2006.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet . Ed. Robert S. Miola. New York: Norton, 2010.

Stritmatter, Roger. "Two More Censored Passages from Q2 Hamlet." Cahiers Élisabéthains 91.1 (2016): 88-95.

Thompson, Ann. “Hamlet 3.1: 'To be or not to be’.” The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare: The World's Shakespeare, 1660-Present, ed. Bruce R. Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016): 1144-50.

Seibers, Tobin. “Shakespeare Differently Disabled.” The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare and Embodiement: Gender, Sexuality, and Race , ed. Valerie Traub (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016): 435-54.

Skinner, Quentin. “Confirmation: The Conjectural Issue.” Forensic Shakespeare (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014): 226-68.

Slater, Michael. “The Ghost in the Machine: Emotion and Mind–Body Union in Hamlet and Descartes," Criticism 58 (2016).

Thompson, Ann, and Neil Taylor, eds. Hamlet: A Critical Reader . London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Weiss, Larry. “The Branches of an Act: Shakespeare's Hamlet Explains his Inaction.” Shakespeare 16.2 (2020): 117-27.

Wells, Stanley, ed. Hamlet and Its Afterlife . Special edition of Shakespeare Survey 45 (1992).

Williams, Deanne. “Enter Ofelia playing on a Lute.” Shakespeare and the Performance of Girlhood (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014): 73-91

Williamson, Claude C.H., ed. Readings on the Character of Hamlet: Compiled from Over Three Hundred Sources .

White, R.S. Avant-Garde Hamlet: Text, Stage, Screen . Lanham: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2015.

Wiles, David. “Hamlet’s Advice to the Players.” The Players’ Advice to Hamlet: The Rhetorical Acting Method from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020): 10-38

Wilson, J. Dover. What Happens in Hamlet . 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1951.

Zamir, Tzachi, ed. Shakespeare's Hamlet: Philosophical Perspectives . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

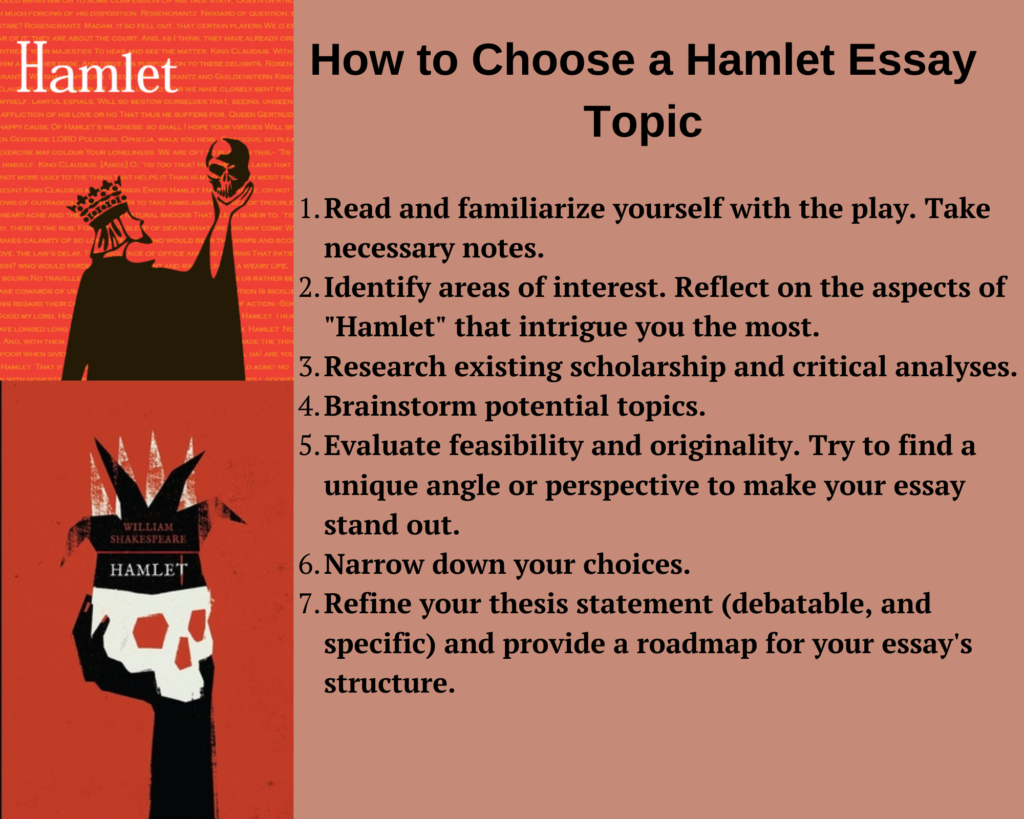

Guidelines for Writing A Great Hamlet Analysis Essay

To enhance the independent work of students and the development of public speaking skills, many teachers resort to such a form of knowledge control as an essay. This type of activity can be attributed to small written works. The essay in its volume is significantly inferior to the thesis since it is usually related to a specific subject under study and includes an analysis of a limited number of concepts considered during training.

Writing a literary essay is usually based on an analysis of a literary text. Sometimes it’s difficult for students to complete this assignment, but at any time they can contact professionals, such as WriteMyPaper4Me , and get a stellar paper! However, it is very important to learn to overcome such difficulties and to complete an essay without any help. Below we will give you recommendations for writing a great Hamlet analysis essay.

5 Key Writing Tips

As it is known, Hamlet has long been recognized by society as the great eternal image of world literature. The play “Hamlet” became not only the closest story for the reader, literary and theatrical critics, actors and directors, but acquired the significance of a text-generating work of art. The eternal image of the doubting Hamlet inspired a whole string of writers who, one way or another, used his character traits in their literary works.

In order to conduct a good literary analysis of the protagonist and the novel as a whole, and as a result, write an excellent essay, the author should take into account the following recommendations:

- Define the structure of your paper. As a rule, an essay consists of three main structural elements: introduction, main part, and conclusion;

- In the introduction a narrator should point the topic, highlight the main issues that need to be considered;

- In the main part, it is advisable to represent a system of argumentation based on a deep study of the play. You should put forward new different ideas in a logical sequence, which will enable the reader to trace the direction of your answer. For the convenience of presentation and clarity of the logic of each argument, evidence, and statement, the main content is divided into paragraphs or sections that may have independent subheadings;

- The conclusion is the last basic element of an essay. The writer usually represents here a summary of basic ideas;

- When checking the work, it is necessary first of all to pay attention to whether the ideas are arranged in a logical order. Usually, each paragraph of the main text should contain no more than one idea in question. In addition, it is important to check each sentence of the work for errors, as a good knowledge of the language should be demonstrated in the essay.

We hope our tips will help you to write a Hamlet analysis essay at the highest level!

Combine all five tips to write the perfect Hamlet analysis essay.

- Pinterest 0

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Drama Criticism › Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 25, 2020 • ( 2 )

With Shakespeare the dramatic resolution conveys us, beyond the man-made sphere of poetic justice, toward the ever-receding horizons of cosmic irony. This is peculiarly the case with Hamlet , for the same reasons that it excites such intensive empathy from actors and readers, critics and writers alike. There may be other Shakespearean characters who are just as memorable, and other plots which are no less impressive; but nowhere else has the outlook of the individual in a dilemma been so profoundly realized; and a dilemma, by definition, is an all but unresolvable choice between evils. Rather than with calculation or casuistry, it should be met with virtue or readiness; sooner or later it will have to be grasped by one or the other of its horns. These, in their broadest terms, have been—for Hamlet, as we interpret him—the problem of what to believe and the problem of how to act.

—Harry Levin, The Question of Hamlet

Hamlet is almost certainly the world’s most famous play, featuring drama’s and literature’s most fascinating and complex character. The many-sided Hamlet—son, lover, intellectual, prince, warrior, and avenger—is the consummate test for each generation’s leading actors, and to be an era’s defining Hamlet is perhaps the greatest accolade one can earn in the theater. The play is no less a proving ground for the critic and scholar, as successive generations have refashioned Hamlet in their own image, while finding in it new resonances and entry points to plumb its depths, perplexities, and possibilities. No other play has been analyzed so extensively, nor has any play had a comparable impact on our culture. The brooding young man in black, skull in hand, has moved out of the theater and into our collective consciousness and cultural myths, joining only a handful of comparable literary archetypes—Oedipus, Faust, and Don Quixote—who embody core aspects of human nature and experience. “It is we ,” the romantic critic William Hazlitt observed, “who are Hamlet.”

Hamlet also commands a crucial, central place in William Shakespeare’s dramatic career. First performed around 1600, the play stands near the midpoint of the playwright’s two-decade career as a culmination and new departure. As the first of his great tragedies, Hamlet signals a decisive shift from the comedies and history plays that launched Shakespeare’s career to the tragedies of his maturity. Although unquestionably linked both to the plays that came before and followed, Hamlet is also markedly exceptional. At nearly 4,000 lines, almost twice the length of Macbeth , Hamlet is Shakespeare’s longest and, arguably, his most ambitious play with an enormous range of characters—from royals to gravediggers—and incidents, including court, bedroom, and graveyard scenes and a play within a play. Hamlet also bristles with a seemingly inexhaustible array of ideas and themes, as well as a radically new strategy for presenting them, most notably, in transforming soliloquies from expositional and motivational asides to the audience into the verbalization of consciousness itself. As Shakespearean scholar Stephen Greenblatt has asserted, “In its moral complexity, psychological depth, and philosophical power, Hamlet seems to mark an epochal shift not only in Shakespeare’s own career but in Western drama; it is as if the play were giving birth to a whole new kind of literary subjectivity.” Hamlet, more than any other play that preceded it, turns its action inward to dramatize an isolated, conflicted psyche struggling to cope with a world that has lost all certainty and consolation. Struggling to reconcile two contradictory identities—the heroic man of action and duty and the Christian man of conscience—Prince Hamlet becomes the modern archetype of the self-divided, alienated individual, desperately searching for self-understanding and meaning. Hamlet must contend with crushing doubt without the support of traditional beliefs that dictate and justify his actions. In describing the arrival of the fragmentation and chaos of the modern world, Victorian poet and critic Matthew Arnold declared that “the calm, cheerfulness, the disinterested objectivity have disappeared, the dialogue of the mind with itself has commenced.” Hamlet anticipates that dialogue by more than two centuries.

Like all of Shakespeare’s plays, Hamlet makes strikingly original uses of borrowed material. The Scandinavian folk tale of Amleth, a prince called upon to avenge his father’s murder by his uncle, was first given literary form by the Danish writer Saxo the Grammarian in his late 12th century Danish History and later adapted in French in François de Belleforest’s Histoires tragiques (1570). This early version of the Hamlet story provided Shakespeare with the basic characters and relationships but without the ghost or the revenger’s uncertainty. In the story of Amleth there is neither doubt about the usurper’s guilt nor any moral qualms in the fulfillment of the avenger’s mission. In preChristian Denmark blood vengeance was a sanctioned filial obligation, not a potentially damnable moral or religious violation, and Amleth successfully accomplishes his duty by setting fire to the royal hall, killing his uncle, and proclaiming himself king of Denmark. Shakespeare’s more immediate source may have been a nowlost English play (c. 1589) that scholars call the Ur – Hamlet. All that has survived concerning this play are a printed reference to a ghost who cried “Hamlet, revenge!” and criticism of the play’s stale bombast. Scholars have attributed the Ur-Hamle t to playwright Thomas Kyd, whose greatest success was The Spanish Tragedy (1592), one of the earliest extant English tragedies. The Spanish Tragedy popularized the genre of the revenge tragedy, derived from Aeschylus’s Oresteia and the Latin plays of Seneca, to which Hamlet belongs. Kyd’s play also features elements that Shakespeare echoes in Hamlet, including a secret crime, an impatient ghost demanding revenge, a protagonist tormented by uncertainty who feigns madness, a woman who actually goes mad, a play within a play, and a final bloodbath that includes the death of the avenger himself. An even more immediate possible source for Hamlet is John Marston’s Antonio’s Revenge (1599), another story of vengeance on a usurper by a sensitive protagonist.

Whether comparing Hamlet to its earliest source or the handling of the revenge plot by Kyd, Marston, or other Elizabethan or Jacobean playwrights, what stands out is the originality and complexity of Shakespeare’s treatment, in his making radically new and profound uses of established stage conventions. Hamlet converts its sensational material—a vengeful ghost, a murder mystery, madness, a heartbroken maiden, a fistfight at her burial, and a climactic duel that results in four deaths—into a daring exploration of mortality, morality, perception, and core existential truths. Shakespeare put mystery, intrigue, and sensation to the service of a complex, profound epistemological drama. The critic Maynard Mack in an influential essay, “The World of Hamlet ,” has usefully identified the play’s “interrogative mode.” From the play’s opening words—“Who’s there?”—to “What is this quintessence of dust?” through drama’s most famous soliloquy—“To be, or not to be, that is the question.”— Hamlet “reverberates with questions, anguished, meditative, alarmed.” The problematic nature of reality and the gap between truth and appearance stand behind the play’s conflicts, complicating Hamlet’s search for answers and his fulfillment of his role as avenger.

Hamlet opens with startling evidence that “something is rotten in the state of Denmark.” The ghost of Hamlet’s father, King Hamlet, has been seen in Elsinore, now ruled by his brother, Claudius, who has quickly married his widowed queen, Gertrude. When first seen, Hamlet is aloof and skeptical of Claudius’s justifications for his actions on behalf of restoring order in the state. Hamlet is morbidly and suicidally disillusioned by the realization of mortality and the baseness of human nature prompted by the sudden death of his father and his mother’s hasty, and in Hamlet’s view, incestuous remarriage to her brother-in-law:

O that this too too solid flesh would melt, Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew! Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d His canon ’gainst self-slaughter! O God! God! How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable Seem to me all the uses of this world! Fie on’t! ah, fie! ’Tis an unweeded garden That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature Possess it merely. That it should come to this!

A recent student at the University of Wittenberg, whose alumni included Martin Luther and the fictional Doctor Faustus, Hamlet is an intellectual of the Protestant Reformation, who, like Luther and Faustus, tests orthodoxy while struggling to formulate a core philosophy. Brought to encounter the apparent ghost of his father, Hamlet alone hears the ghost’s words that he was murdered by Claudius and is compelled out of his suicidal despair by his pledge of revenge. However, despite the riveting presence of the ghost, Hamlet is tormented by doubts. Is the ghost truly his father’s spirit or a devilish apparition tempting Hamlet to his damnation? Is Claudius truly his father’s murderer? By taking revenge does Hamlet do right or wrong? Despite swearing vengeance, Hamlet delays for two months before taking any action, feigning madness better to learn for himself the truth about Claudius’s guilt. Hamlet’s strange behavior causes Claudius’s counter-investigation to assess Hamlet’s mental state. School friends—Rosencrantz and Guildenstern—are summoned to learn what they can; Polonius, convinced that Hamlet’s is a madness of love for his daughter Ophelia, stages an encounter between the lovers that can be observed by Claudius. The court world at Elsinore, is, therefore, ruled by trickery, deception, role playing, and disguise, and the so-called problem of Hamlet, of his delay in acting, is directly related to his uncertainty in knowing the truth. Moreover, the suspicion of his father’s murder and his mother’s sexual betrayal shatter Hamlet’s conception of the world and his responsibility in it. Pushed back to the suicidal despair of the play’s opening, Hamlet is paralyzed by indecision and ambiguity in which even death is problematic, as he explains in the famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy in the third act:

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would these fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death— The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn No traveller returns—puzzles the will, And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry And lose the name of action.

The arrival of a traveling theatrical group provides Hamlet with the empirical means to resolve his doubts about the authenticity of the ghost and Claudius’s guilt. By having the troupe perform the Mousetrap play that duplicates Claudius’s crime, Hamlet hopes “to catch the conscience of the King” by observing Claudius’s reaction. The king’s breakdown during the performance seems to confirm the ghost’s accusation, but again Hamlet delays taking action when he accidentally comes upon the guilt-ridden Claudius alone at his prayers. Rationalizing that killing the apparently penitent Claudius will send him to heaven and not to hell, Hamlet decides to await an opportunity “That has no relish of salvation in’t.” He goes instead to his mother’s room where Polonius is hidden in another attempt to learn Hamlet’s mind and intentions. This scene between mother and son, one of the most powerful and intense in all of Shakespeare, has supported the Freudian interpretation of Hamlet’s dilemma in which he is stricken not by moral qualms but by Oedipal guilt. Gertrude’s cries of protest over her son’s accusations cause Polonius to stir, and Hamlet finally, instinctively strikes the figure he assumes is Claudius. In killing the wrong man Hamlet sets in motion the play’s catastrophes, including the madness and suicide of Ophelia, overwhelmed by the realization that her lover has killed her father, and the fatal encounter with Laertes who is now similarly driven to avenge a murdered father. Convinced of her son’s madness, Gertrude informs Claudius of Polonius’s murder, prompting Claudius to alter his order for Hamlet’s exile to England to his execution there.

Hamlet’s mental shift from reluctant to willing avenger takes place offstage during his voyage to England in which he accidentally discovers the execution order and then after a pirate attack on his ship makes his way back to Denmark. He returns to confront the inescapable human condition of mortality in the graveyard scene of act 5 in which he realizes that even Alexander the Great must return to earth that might be used to “stop a beer-barrel” and Julius Caesar’s clay to “stop a hole to keep the wind away.” This sobering realization that levels all earthly distinctions of nobility and acclaim is compounded by the shock of Ophelia’s funeral procession. Hamlet sustains his balance and purpose by confessing to Horatio his acceptance of a providential will revealed to him in the series of accidents on his voyage to England: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, / Roughhew them how we will.” Finally accepting his inability to control his life, Hamlet resigns himself to accept whatever comes. Agreeing to a duel with Laertes that Claudius has devised to eliminate his nephew, Hamlet asserts that “There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all.”

In the carnage of the play’s final scene, Hamlet ironically manages to achieve his revenge while still preserving his nobility and moral stature. It is the murderer Claudius who is directly or indirectly responsible for all the deaths. Armed with a poisonedtip sword, Laertes strikes Hamlet who in turn manages to slay Laertes with the lethal weapon. Meanwhile, Gertrude drinks from the poisoned cup Claudius intended to insure Hamlet’s death, and, after the remorseful Laertes blames Claudius for the plot, Hamlet, hesitating no longer, fatally stabs the king. Dying in the arms of Horatio, Hamlet orders his friend to “report me and my cause aright / To the unsatisfied” and transfers the reign of Denmark to the last royal left standing, the Norwegian prince Fortinbras. King Hamlet’s death has been avenged but at a cost of eight lives: Polonius, Ophelia, Rosencranz, Guildenstern, Laertes, Gertrude, Claudius, and Prince Hamlet. Order is reestablished but only by Denmark’s sworn enemy. Shakespeare’s point seems unmistakable: Honor and duty that command revenge consume the guilty and the innocent alike. Heroism must face the reality of the graveyard.

Fortinbras closes the play by ordering that Hamlet be carried off “like a soldier” to be given a military funeral underscoring the point that Hamlet has fallen as a warrior on a battlefield of both the duplicitous court at Elsinore and his own mind. The greatness of Hamlet rests in the extraordinary perplexities Shakespeare has discovered both in his title character and in the events of the play. Few other dramas have posed so many or such knotty problems of human existence. Is there a special providence in the fall of a sparrow? What is this quintessence of dust? To be or not to be?

Hamlet Oxford Lecture by Emma Smith

Analysis of William Shakespeare’s Plays

Share this:

Categories: Drama Criticism , Literature

Tags: Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Bibliography Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Character Study Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Criticism Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , ELIZABEHAN POETRY AND PROSE , Essays Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Hamlet , Hamlet Analysis , Hamlet Criticism , Hamlet Guide , Hamlet Notes , Hamlet Summary , Literary Criticism , Notes Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Plot Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Shakespeare's Hamlet , Shakespeare's Hamlet Guide , Shakespeare's Hamlet Lecture , Simple Analysis Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Study Guides Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Summary Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Synopsis Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , Themes Of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet , William Shakespeare

Related Articles

- Analysis of William Shakespeare's The Tempest | Literary Theory and Criticism

- Analysis of William Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra | Literary Theory and Criticism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Essays About Hamlet: Top 5 Examples and 10 Prompts

To write or not to write? To discover interesting topic ideas for your next essay, see below our round-up of helpful essays about Hamlet and writing topic prompts.

The tragedy of Hamlet , Prince of Denmark, is arguably the most famous work of William Shakespeare – or perhaps in the world of literature. A play revolving around love, betrayal, madness, and revenge, Hamlet is a masterpiece that opens with the murder of the King of Denmark. The ghost of the king will go on to appear before his son Hamlet throughout the play, seeking his help for vengeance by killing the new king, Hamlet’s uncle.

Written from 1600 to 1601 with five acts and published in a quarto edition, Hamlet has since been a beloved on the theatrical stages and modern film adaptations, becoming Shakespeare’s longest play and one of the most quoted in many art forms with its “To be or not to be” soliloquy.

Read on to see our essays and prompts about Hamlet.

Top 5 Essay Examples

1. ”review: in a powerful ‘hamlet,’ a fragile prince faces his foes” by maya phillips, 2. “the concept of madness in hamlet by shakespeare” by cansu yağsız, 3. “analyzing the theme of religion in william shakespeare’s ‘hamlet’” by journey holm, 4. “ophelia, gender and madness” by ellaine showalter, 5. “the hamlet effect” by holly crocker, 1. the beginnings of hamlet, 2. was hamlet mad or not, 3. physicians’ diagnosis of hamlet, 4. feminism in the eyes of ophelia, 5. religion in hamlet, 6. oedipal complex in hamlet, 7. imageries in hamlet, 8. shakespeare’s language in hamlet, 9. an analysis of “to be or not to be” , 10. hamlet as a philosophical work.

“Hamlet” is one of the Shakespeare plays that most suffers from diminishing returns — adaptations that try too hard to innovate, to render a classic modern and hip.”

With the many theatrical adaptations of Hamlet, it may be a tall order for production companies to add new flairs to the play while being faithful to Shakespeare’s masterpiece. But Robert Icke, a theater director, stuns an audience with his production’s creative and technical genius, while Alex Lawther, his actor, offers a refreshing, charismatic portrayal of Hamlet.

“The cause of these three characters’ madness are trauma and unrequited love. They also have a spot in common: a devastating loss of someone significant in their lives… In my view, Shakespeare wrote about these characters’ madness almost like a professional about psychology, making the causes and consequences of their madness reasonable.”

Madness is the most apparent theme in Hamlet, affecting the main character, Hamlet, his love interest, Ophelia, and her brother, Laertes. The novel is most reflective of Shakespeare’s attraction to the concept of madness, as he was said to have personally studied its causes, including unrequited love, trauma from losses, and burnout.

“…I will argue that Hamlet’s hesitance to avenge his father’s death comes from something deeper than a meditation on another man’s life, a sort of faith. I will use three scenes in Shakespeare’s Hamlet to establish that the reason for Hamlet’s hesitance is religion and the fear of his own eternal damnation in hellfire.”

The essay builds on a pool of evidence to prove the religiousness of Hamlet. But, mainly, the author underscores that it is Hamlet’s religious reflections, not his alleged mental incapacity, that stifle him from performing his duty to his father and killing his murderer.

“Shakespeare gives us very little information from which to imagine a past for Ophelia… Yet Ophelia is the most represented of Shakespeare’s heroines in painting, literature and popular culture.”

The essay walks readers through the depictions of Ophelia in various stages and periods, particularly her sexuality. But the fascination for this heroine goes beyond the stage. Ophelia’s madness in the play has paved the way for constructive concepts on insanity among young women. She has also inspired many artists of the Pre-Rapahelite period and feminists to reimagine Hamlet through the lens of feminism.

“… [A]s the shame-and-troll cycle of Internet culture spins out of control, lives are ruined. Some of these lives are lesser, we might think, because they are racist, sexist, or just unbelievably stupid. Shakespeare’s Hamlet cautions us against espousing this attitude: it is not that we shouldn’t call out inane or wrong ideas… He errs, however, when he acts as if Polonius’s very life doesn’t matter.”

An English professor rethinks our present moral compass through the so-called “Hamlet Effect,” which pertains to how one loses moral standards when doing something righteous. Indeed, Hamlet’s desire for retribution for his father is justifiable. However, given his focus on his bigger, more heroic goal of revenge, he treats the lives of other characters as having no significance.

10 Writing Prompts For Essays About Hamlet

It is said that Shakespeare’s primary inspiration for Hamlet lies in the pages of François de Belleforest’s Histories Tragique, published in 1570 when Shakespeare was six years old. For your historical essay, determine the similarities between Belleforest’s book and Hamlet. Research other stories that have helped Shakespeare create this masterpiece.

Hamlet is the most fascinating of Shakespeare’s heroes for the complexity of his character, desire, and existential struggle. But is Hamlet sane or insane? That question has been at the center of debates in the literary world. To answer this, pore over Hamlet’s seven soliloquies and find lines that most reveal Hamlet’s conflicting thoughts and feelings.

Physicians have long mused over Hamlet’s characters like real people. They have even turned the cast into subjects of their psychiatric work but have come up with different diagnoses. For this prompt, dig deep into the ever-growing pool of psychoanalysis commentaries on Hamlet. Then, find out how these works affect future adaptations in theaters.

Throughout the play, Ophelia is depicted as submissive, bending to the whims of male characters in the play. In your essay, explain how Ophelia’s character reflects the perception and autonomy of women in the Elizabethan era when the play was created. You can go further by analyzing whether Shakespeare was a misogynist trapping his heroine into such a helpless character or a feminist exposing these realities.

Hamlet was written at a time London was actively practicing Protestantism, so it would be interesting to explore the religious theme in Hamlet to know how Shakespeare perceives the dominant religion in England in his time and Catholicism before the Reformation. First, identify the religions of the characters. Then, describe how their religious beliefs affected their decisions in the scenes.

Father of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud proposes that Hamlet is hesitant to kill Claudius due to his Oedipus Complex, which grows with him in his adult years. An Oedipus Complex pertains to a male infant’s repressed desire to take possession of his mother from his father, who is viewed as a rival. First, write your analysis on whether you agree with Freud’s view. Then, gather evidence from passages of the play to agree or argue otherwise.

Hamlet in an “inky cloak” to signify his grief, a Denmark under Claudius linked to corruption and disease — these are just some imageries used in Hamlet. Find other imageries and explain how they achieved their dramatic effect on highlighting the moods of characters and scenes.

During Shakespeare’s time, playwrights are expected to follow the so-called Doctrine of Decorum which recognizes the hierarchy in society. So the gravediggers in Hamlet spoke in prose, as Hamlet does in his mad soliloquies. However, Shakespeare breaks this rule in Hamlet. Find dialogues where Shakespeare allowed Hamlet’s characters to be more distinct and flexible in language.

In the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, Hamlet contemplates suicide. Why do you think these lines continue to be relevant to this day even after centuries since Shakespeare? Answer this in your essay by elaborating on how Hamlet, through these lines, shares the suffering of the “whips and scorns of time” and our innate nature to endure.

In your essay, evaluate the famous philosophies that resound in Hamlet. For example, with the theme of suicide, Hamlet may echo the teachings of Seneca and the movement of Stoicism , who view suicide as freedom from life’s chains. One may also find traces of Albert Camus’s lessons from the Myth of Sisyphus, which tells of a human’s ability to endure.

Interested in learning more? Check out our essay writing tips . If you’re still stuck, check out our general resource of essay writing topics .

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

100+ Hamlet Essay Topics

Table of Contents

What is a Hamlet Essay?

A Hamlet essay is an analytical piece that delves into the themes, characters, plot, motifs, or historical context of William Shakespeare’s iconic tragedy, “Hamlet”. This play, often touted as one of the greatest pieces of literature ever written, is rife with profound topics and subtle nuances. When writing an essay on “Hamlet”, students explore these intricacies, shedding light on the play’s enduring relevance and its multifaceted layers.

Choosing the Right Topic for Your Hamlet Essay: A Quick Guide

In choosing a Hamlet essay topic, consider what aspect of the play intrigues you the most. Is it the psychological torment of Hamlet, the play’s exploration of existentialism, or perhaps its political undertones? Reflect on the themes that resonate with you. Review the play and take notes on pivotal scenes or dialogues. Your passion will come through in your writing, making your essay more engaging. Moreover, ensure your topic is not too broad; narrowing it down will allow for a deeper analysis.

Hamlet Essay Topics to Spark Your Imagination

Character analysis.

- Hamlet : A Study in Paralysis and Procrastination

- Ophelia’s Descent into Madness

- The Dual Nature of King Claudius

- Gertrude: Victim or Villain?

- Horatio: Hamlet’s Constant in a Chaotic World

Thematic Concerns

- The Play Within the Play: Exploring Metatheatre in Hamlet

- Madness vs. Sanity: A Thin Line in Elsinore

- Revenge and Its Consuming Nature

- Death and Decay: Imagery and Symbolism

- Betrayal and Loyalty: Conflicting Values

Symbolism and Motifs

- The Significance of Yorick’s Skull

- The Poisoned Sword and Cup: Instruments of Fate

- The Role of the Ghost in Driving the Plot

- Flowers in Ophelia’s Hands: More Than Just Bloom

- The Omnipresent Notion of Eavesdropping

Historical and Contextual Analysis

- Elizabethan Beliefs About Madness as Reflected in Hamlet

- Hamlet and the Renaissance Man

- The Influence of Greek Tragedy on “Hamlet”

- Political Strife and Its Reflection in Elsinore

- “Hamlet” in the Lens of Protestant Reformation

Comparative Studies

- “Hamlet” and “Oedipus Rex”: Tragedies of Fate

- The Role of Women in “Hamlet” vs. “Macbeth”

- How Film Adaptations Have Interpreted Hamlet’s Soliloquies

- Modern Interpretations of “Hamlet” in Popular Culture

- “Hamlet” and “Lion King”: From Denmark to Pride Rock

Character Exploration

- Hamlet : The Complexity of His Avenging Mission

- Ophelia: Between Love and Loyalty

- The True Intentions of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern

- Laertes: The Counterpart to Hamlet’s Revenge Quest

- Polonius: The Manipulative Councilor

Themes and Philosophical Inquiries

- The Ubiquity of Death in “Hamlet”

- Exploring Existentialism in Hamlet’s Soliloquies

- The Consequences of Deception and Secrets

- The Tragedy of Miscommunication in Elsinore

- Corruption and Moral Degradation in the Danish Court

Symbolism and Literary Devices

- The Role of Ghosts in Elizabethan Drama and “Hamlet”

- The Significance of the Play-within-a-Play Scene

- The Use of Mirrors and Reflections in Character Dynamics

- Gardens as Symbols of Decay and Corruption

- The Sea and its Symbolic Representations

Structural Analysis

- The Role and Impact of Soliloquies in “Hamlet”

- The Use of Foreshadowing in the Tragedy’s Climax

- The Dramatic Ironies that Pervade the Play

- The Significance of Off-Stage Actions in “Hamlet”

- The Role of Acts and Scenes in Pacing the Drama

Comparative Analyses

- Contrasting “Hamlet” with Other Shakespearean Tragedies

- “Hamlet” and “Othello”: Exploring Jealousy and Betrayal

- A Comparative Study of “Hamlet” and its Sources

- The Transformation of the “Hamlet” Story Through Time

- “Hamlet” vs. “Romeo and Juliet”: Love in the Midst of Tragedy

Modern Interpretations and Adaptations

- “Hamlet” in Today’s Pop Culture References

- Cinematic Interpretations of “Hamlet”: From Olivier to Branagh

- “Hamlet” in Non-English Theater: A Global Perspective

- Updating “Hamlet”: The Challenges and Rewards

- The Influence of “Hamlet” on Modern Dramatic Writing

Feminist Perspectives

- The Role and Representation of Women in “Hamlet”

- Gertrude: Passive Queen or Calculative Player?

- Ophelia’s Voice and Silence: A Feminist Reading

- The Paternal Controls Over Ophelia and Gertrude

- Women’s Agency in “Hamlet”: A Critical Exploration

Historical and Contextual Insights

- The Influence of Shakespeare’s Life Events on “Hamlet”

- “Hamlet” and the Elizabethan Worldview on Ghosts and the Supernatural

- Political Undertones in “Hamlet”: The State of Denmark

- Elizabethan Theater and its Reflection in “Hamlet”

- “Hamlet” and the Reflection of Renaissance Humanism

Psychological Angles

- Hamlet’s Oedipal Complex Explored

- The Mental State of Characters: Who’s Truly Mad?

- The Psychological Effects of Grief and Loss in “Hamlet”

- Fear, Paranoia, and Suspicion: A Psychological Dive into Elsinore’s Inhabitants

- Analyzing “Hamlet” Through the Lens of Freudian Psychoanalysis

Miscellaneous Topics

- The Role of Fate vs. Free Will in “Hamlet”

- The Ethical Implications of Revenge in “Hamlet”

- Exploring Religion and Morality in “Hamlet”

- The Concept of Honor in “Hamlet”

- The Nature of True Friendship in the Play

Narrative Techniques and Structure

- The Role of the Chorus in “Hamlet”: Absence and Implication

- Non-linear Storytelling in “Hamlet”: Flashbacks and Memories

- The Significance of Interludes and Their Impact on the Main Plot

- Parallel Plots in “Hamlet”: Subplots and Their Relation to the Central Narrative

Cultural Perspectives

- “Hamlet” from an Eastern Philosophical Perspective

- “Hamlet” in the Context of African Oral Traditions

- Exploring “Hamlet” from a Postcolonial Point of View

- The Play’s Universality: Why “Hamlet” Resonates Globally

Philosophical and Ethical Discussions

- “To Be or Not To Be”: Hamlet’s Exploration of Nihilism

- The Dichotomy of Action vs. Inaction in “Hamlet”

- Ethical Ambiguities: Is Hamlet Justified in His Actions?

- Determinism and Free Will in “Hamlet”

Performance and Stagecraft