How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

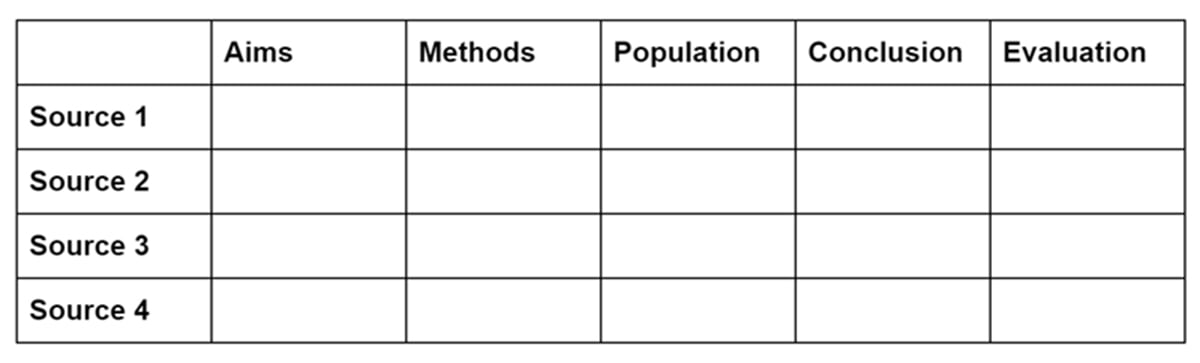

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

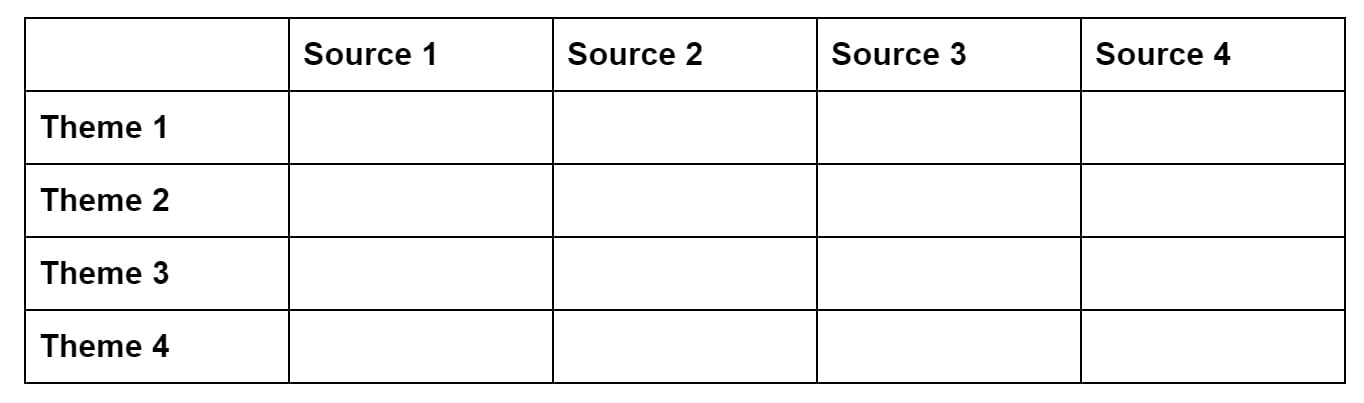

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

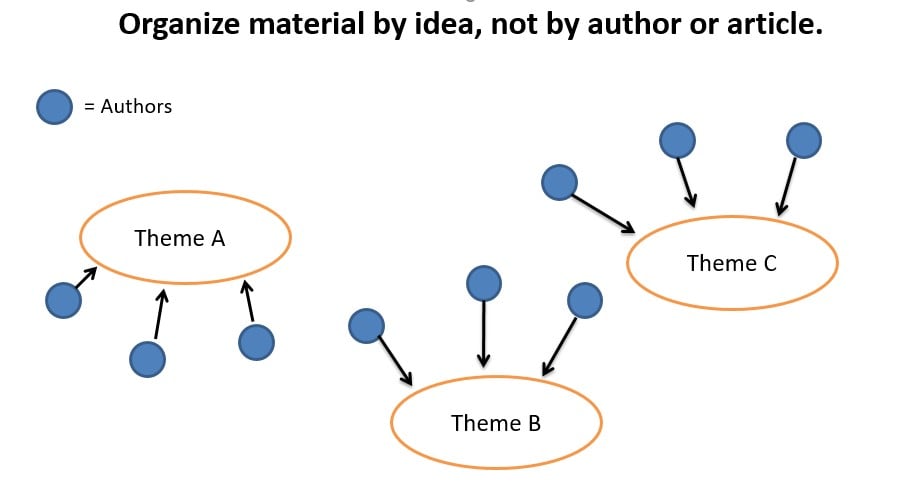

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

Synthesis Visualization

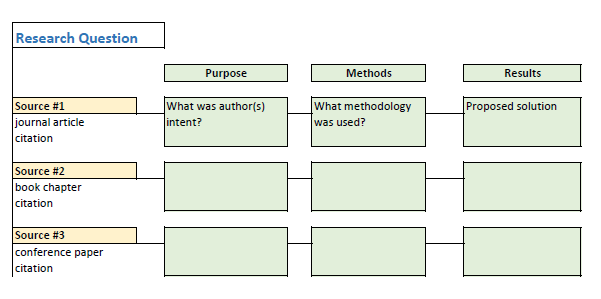

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

excellent , thank you

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Literature Review How To

- Things To Consider

- Synthesizing Sources

- Video Tutorials

- Books On Literature Reviews

What is Synthesis

What is Synthesis? Synthesis writing is a form of analysis related to comparison and contrast, classification and division. On a basic level, synthesis requires the writer to pull together two or more summaries, looking for themes in each text. In synthesis, you search for the links between various materials in order to make your point. Most advanced academic writing, including literature reviews, relies heavily on synthesis. (Temple University Writing Center)

How To Synthesize Sources in a Literature Review

Literature reviews synthesize large amounts of information and present it in a coherent, organized fashion. In a literature review you will be combining material from several texts to create a new text – your literature review.

You will use common points among the sources you have gathered to help you synthesize the material. This will help ensure that your literature review is organized by subtopic, not by source. This means various authors' names can appear and reappear throughout the literature review, and each paragraph will mention several different authors.

When you shift from writing summaries of the content of a source to synthesizing content from sources, there is a number things you must keep in mind:

- Look for specific connections and or links between your sources and how those relate to your thesis or question.

- When writing and organizing your literature review be aware that your readers need to understand how and why the information from the different sources overlap.

- Organize your literature review by the themes you find within your sources or themes you have identified.

- << Previous: Things To Consider

- Next: Video Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Nov 30, 2018 4:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/literature-review

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

Write a Literature Review

- Find This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other. After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix to help you see how they relate to each other, and apply to each of your themes or variables. By arranging your sources in a matrix by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Oct 11, 2023 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.goucher.edu/literature-review

Literature Reviews

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- Getting started

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

How to synthesize

Approaches to synthesis.

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

In the synthesis step of a literature review, researchers analyze and integrate information from selected sources to identify patterns and themes. This involves critically evaluating findings, recognizing commonalities, and constructing a cohesive narrative that contributes to the understanding of the research topic.

Here are some examples of how to approach synthesizing the literature:

💡 By themes or concepts

🕘 Historically or chronologically

📊 By methodology

These organizational approaches can also be used when writing your review. It can be beneficial to begin organizing your references by these approaches in your citation manager by using folders, groups, or collections.

Create a synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix allows you to visually organize your literature.

Topic: ______________________________________________

Topic: Chemical exposure to workers in nail salons

- << Previous: 4. Organize your results

- Next: 6. Write the review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 12:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/lit-reviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Library Guides

Literature reviews: synthesis.

- Criticality

Synthesise Information

So, how can you create paragraphs within your literature review that demonstrates your knowledge of the scholarship that has been done in your field of study?

You will need to present a synthesis of the texts you read.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains synthesis for us in the following video:

Synthesising Texts

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is an important element of academic writing, demonstrating comprehension, analysis, evaluation and original creation.

With synthesis you extract content from different sources to create an original text. While paraphrase and summary maintain the structure of the given source(s), with synthesis you create a new structure.

The sources will provide different perspectives and evidence on a topic. They will be put together when agreeing, contrasted when disagreeing. The sources must be referenced.

Perfect your synthesis by showing the flow of your reasoning, expressing critical evaluation of the sources and drawing conclusions.

When you synthesise think of "using strategic thinking to resolve a problem requiring the integration of diverse pieces of information around a structuring theme" (Mateos and Sole 2009, p448).

Synthesis is a complex activity, which requires a high degree of comprehension and active engagement with the subject. As you progress in higher education, so increase the expectations on your abilities to synthesise.

How to synthesise in a literature review:

Identify themes/issues you'd like to discuss in the literature review. Think of an outline.

Read the literature and identify these themes/issues.

Critically analyse the texts asking: how does the text I'm reading relate to the other texts I've read on the same topic? Is it in agreement? Does it differ in its perspective? Is it stronger or weaker? How does it differ (could be scope, methods, year of publication etc.). Draw your conclusions on the state of the literature on the topic.

Start writing your literature review, structuring it according to the outline you planned.

Put together sources stating the same point; contrast sources presenting counter-arguments or different points.

Present your critical analysis.

Always provide the references.

The best synthesis requires a "recursive process" whereby you read the source texts, identify relevant parts, take notes, produce drafts, re-read the source texts, revise your text, re-write... (Mateos and Sole, 2009).

What is good synthesis?

The quality of your synthesis can be assessed considering the following (Mateos and Sole, 2009, p439):

Integration and connection of the information from the source texts around a structuring theme.

Selection of ideas necessary for producing the synthesis.

Appropriateness of the interpretation.

Elaboration of the content.

Example of Synthesis

Original texts (fictitious):

Synthesis:

Animal experimentation is a subject of heated debate. Some argue that painful experiments should be banned. Indeed it has been demonstrated that such experiments make animals suffer physically and psychologically (Chowdhury 2012; Panatta and Hudson 2016). On the other hand, it has been argued that animal experimentation can save human lives and reduce harm on humans (Smith 2008). This argument is only valid for toxicological testing, not for tests that, for example, merely improve the efficacy of a cosmetic (Turner 2015). It can be suggested that animal experimentation should be regulated to only allow toxicological risk assessment, and the suffering to the animals should be minimised.

Bibliography

Mateos, M. and Sole, I. (2009). Synthesising Information from various texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24 (4), 435-451. Available from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03178760 [Accessed 29 June 2021].

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Criticality >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2023 10:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/literature-reviews

CONNECT WITH US

Literature Review Basics

- What is a Literature Review?

- Synthesizing Research

- Using Research & Synthesis Tables

- Additional Resources

About the Research and Synthesis Tables

Research Tables and Synthesis Tables are useful tools for organizing and analyzing your research as you assemble your literature review. They represent two different parts of the review process: assembling relevant information and synthesizing it. Use a Research table to compile the main info you need about the items you find in your research -- it's a great thing to have on hand as you take notes on what you read! Then, once you've assembled your research, use the Synthesis table to start charting the similarities/differences and major themes among your collected items.

We've included an Excel file with templates for you to use below; the examples pictured on this page are snapshots from that file.

- Research and Synthesis Table Templates This Excel workbook includes simple templates for creating research tables and synthesis tables. Feel free to download and use!

Using the Research Table

This is an example of a research table, in which you provide a basic description of the most important features of the studies, articles, and other items you discover in your research. The table identifies each item according to its author/date of publication, its purpose or thesis, what type of work it is (systematic review, clinical trial, etc.), the level of evidence it represents (which tells you a lot about its impact on the field of study), and its major findings. Your job, when you assemble this information, is to develop a snapshot of what the research shows about the topic of your research question and assess its value (both for the purpose of your work and for general knowledge in the field).

Think of your work on the research table as the foundational step for your analysis of the literature, in which you assemble the information you'll be analyzing and lay the groundwork for thinking about what it means and how it can be used.

Using the Synthesis Table

This is an example of a synthesis table or synthesis matrix , in which you organize and analyze your research by listing each source and indicating whether a given finding or result occurred in a particular study or article ( each row lists an individual source, and each finding has its own column, in which X = yes, blank = no). You can also add or alter the columns to look for shared study populations, sort by level of evidence or source type, etc. The key here is to use the table to provide a simple representation of what the research has found (or not found, as the case may be). Think of a synthesis table as a tool for making comparisons, identifying trends, and locating gaps in the literature.

How do I know which findings to use, or how many to include? Your research question tells you which findings are of interest in your research, so work from your research question to decide what needs to go in each Finding header, and how many findings are necessary. The number is up to you; again, you can alter this table by adding or deleting columns to match what you're actually looking for in your analysis. You should also, of course, be guided by what's actually present in the material your research turns up!

- << Previous: Synthesizing Research

- Next: Additional Resources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 12:06 PM

- URL: https://usi.libguides.com/literature-review-basics

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Synthesizing Sources

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- synthesize key sources connecting them with the research question and topic area.

7.1 Overview of synthesizing

7.1.1 putting the pieces together.

Combining separate elements into a whole is the dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections among and between numerous and varied source materials. A literature review is not an annotated bibliography, organized by title, author, or date of publication. Rather, it is grouped by topic to create a whole view of the literature relevant to your research question.

Your synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers you collected as well as your ability to integrate the results of your analysis into your own literature review. Each paper collected should be critically evaluated and weighed for “adequacy, appropriateness, and thoroughness” ( Garrard, 2017 ) before inclusion in your own review. Papers that do not meet this criteria likely should not be included in your literature review.

Begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline where you will summarize, using common themes you have identified and the sources you have found. The summary grid or outline will help you compare and contrast the themes so you can see the relationships among them as well as areas where you may need to do more searching. Whichever method you choose, this type of organization will help you to both understand the information you find and structure the writing of your review. Remember, although “the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question” ( Bennard et al., 2014 ).

As you read through the material you gather, look for common themes as they may provide the structure for your literature review. And, remember, research is an iterative process: it is not unusual to go back and search information sources for more material.

At one extreme, if you are claiming, ‘There are no prior publications on this topic,’ it is more likely that you have not found them yet and may need to broaden your search. At another extreme, writing a complete literature review can be difficult with a well-trod topic. Do not cite it all; instead cite what is most relevant. If that still leaves too much to include, be sure to reference influential sources…as well as high-quality work that clearly connects to the points you make. ( Klingner, Scanlon, & Pressley, 2005 ).

7.2 Creating a summary table

Literature reviews can be organized sequentially or by topic, theme, method, results, theory, or argument. It’s important to develop categories that are meaningful and relevant to your research question. Take detailed notes on each article and use a consistent format for capturing all the information each article provides. These notes and the summary table can be done manually, using note cards. However, given the amount of information you will be recording, an electronic file created in a word processing or spreadsheet is more manageable. Examples of fields you may want to capture in your notes include:

- Authors’ names

- Article title

- Publication year

- Main purpose of the article

- Methodology or research design

- Participants

- Measurement

- Conclusions

Other fields that will be useful when you begin to synthesize the sum total of your research:

- Specific details of the article or research that are especially relevant to your study

- Key terms and definitions

- Strengths or weaknesses in research design

- Relationships to other studies

- Possible gaps in the research or literature (for example, many research articles conclude with the statement “more research is needed in this area”)

- Finally, note how closely each article relates to your topic. You may want to rank these as high, medium, or low relevance. For papers that you decide not to include, you may want to note your reasoning for exclusion, such as ‘small sample size’, ‘local case study,’ or ‘lacks evidence to support assertion.’

This short video demonstrates how a nursing researcher might create a summary table.

7.2.1 Creating a Summary Table

Summary tables can be organized by author or by theme, for example:

For a summary table template, see http://blogs.monm.edu/writingatmc/files/2013/04/Synthesis-Matrix-Template.pdf

7.3 Creating a summary outline

An alternate way to organize your articles for synthesis it to create an outline. After you have collected the articles you intend to use (and have put aside the ones you won’t be using), it’s time to identify the conclusions that can be drawn from the articles as a group.

Based on your review of the collected articles, group them by categories. You may wish to further organize them by topic and then chronologically or alphabetically by author. For each topic or subtopic you identified during your critical analysis of the paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which ones in the group differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for the contradiction (for example, differences in population demographics). Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic as the entire group of studies relate to it. For example, you may have several studies that agree on outcome, such as ‘hands on learning is best for science in elementary school’ or that ‘continuing education is the best method for updating nursing certification.’ In that case, you may want to organize by methodology used in the studies rather than by outcome.

Organize your outline in a logical order and prepare to write the first draft of your literature review. That order might be from broad to more specific, or it may be sequential or chronological, going from foundational literature to more current. Remember, “an effective literature review need not denote the entire historical record, but rather establish the raison d’etre for the current study and in doing so cite that literature distinctly pertinent for theoretical, methodological, or empirical reasons.” ( Milardo, 2015, p. 22 ).

As you organize the summarized documents into a logical structure, you are also appraising and synthesizing complex information from multiple sources. Your literature review is the result of your research that synthesizes new and old information and creates new knowledge.

7.4 Additional resources:

Literature Reviews: Using a Matrix to Organize Research / Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources / Indiana University

Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix / Florida International University

Sample Literature Reviews Grid / Complied by Lindsay Roberts

Select three or four articles on a single topic of interest to you. Then enter them into an outline or table in the categories you feel are important to a research question. Try both the grid and the outline if you can to see which suits you better. The attached grid contains the fields suggested in the video .

Literature Review Table

Test yourself.

- Select two articles from your own summary table or outline and write a paragraph explaining how and why the sources relate to each other and your review of the literature.

- In your literature review, under what topic or subtopic will you place the paragraph you just wrote?

Image attribution

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students Copyright © by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Introduction to Social Work Research

Writing a literature review.

- Background Information

- Peer Review & Evaluation

- Article Comparison

- Creating an Outline

It is important to critically think about all of the sources you've read, both background information and scholarly journal articles, and synthesize that information into new conclusions that are unique to you. A synthesis requires critical thinking about the articles, determining where themes align, what they're saying that lines up, and what they're saying that might conflict with each other. What conclusions do these conflicts cause you to draw?

This page discusses how to synthesize information from your sources.

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources from IUPUI's University Writing Center Walks through the process of creating a synthesis matrix.

Summarizing vs. Synthesizing

While a summary is a way of concisely relating important themes and elements from a larger work or works in a condensed form, a synthesis takes the information from a variety of works and combines them together to create something new.

Synthesis :

"Synthesis is similar to putting a puzzle together—piecing together information to create a whole. The outcome of this synthesis might be numeric, such as in an overall rating perhaps best typified in a quantitative weight and sum strategy, or through the use of meta-analysis, or the synthesis might be textual, such as in an analytic conclusion."

Synthesis. (2005). In Mathison, S. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of evaluation . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412950558

- Approaches to Reviewing Research in Education from Sage Knowledge

How to Synthesize

Basic steps for synthesizing information:

- Highlight the main themes/ideas of each article

- Note which themes and ideas appear across multiple articles

- Discuss how each article deals similarly or differently with each theme

- Discuss how combining the information from all three articles can better address your research question than a single article alone

- Write your deductions from combining this information in your own words using all three articles

Summary of 1 article:

By analyzing monthly cost data of 9 drugs that were approved by the FDA for Multiple Sclerosis from 1993 to 2013, Hartung, et al. determined that the cost of MS drugs is increasing far beyond inflation rates, which has a negative effect on MS patients (2015).

Summary of 2 articles:

The cost of MS drugs is increasing far beyond inflation rates, which has a negative effect on MS patients (Hartung, et al., 2015). For low income MS patients, like Shereese Hickson, this cost has proven to be more than they can pay (Hancock, 2018).

Synthesis of 2 articles:

The cost of MS drugs is increasing far beyond inflation rates, which has a negative effect on MS patients (Hartung, et al., 2015). The personal experience of Shereese Hickson shows what that negative impact looks like (Hancock, 2018). This illustrates how vulnerable populations, like low-income MS patients, can be at greater risk of experiencing the negative impacts of rising drug costs.

Hartung, D. M., Bourdette, D. N., Ahmed, S. M., & Whitham, R. H. (2015). The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: Too big to fail? Neurology, 84 (21), 2185-2192. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001608

Hancock, J. (2018). Chronically Ill, Traumatically Billed: $123,019 For 2 Multiple Sclerosis Treatments. Kaiser Health News . Retrieved from https://khn.org/news/chronically-ill-traumatically-billed-the-123k-medicine-for-ms/

Ask a Librarian

Chat With Us

EID login required

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2023 2:28 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/sw310

How to Write a Literature Review - A Self-Guided Tutorial

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the question

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Searching article databases - video

- Finding the article full-text

- Citation trails

- When to stop searching

- Citation Managers

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write literature review

- Additional Resources

You can meet with a librarian to talk about your literature review, or other library-related topics.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

Synthesis Vizualization

Four examples of student writing.

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Synthesis Matrix Example

From Jennifer Lim

Synthesis Templates

Synthesis grids are organizational tools used to record the main concepts of your sources and can help you make connections about how your sources relate to one another.

- Source Template Basic Literature Review Source Template from Walden University Writing Center to help record the main findings and concepts from different articles.

- Sample Literature Review Grids This spreadsheet contains multiple tabs with different grid templates. Download or create your own copy to begin recording notes.

- << Previous: 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- Next: 7. Write literature review >>

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 2:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/literature-review

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

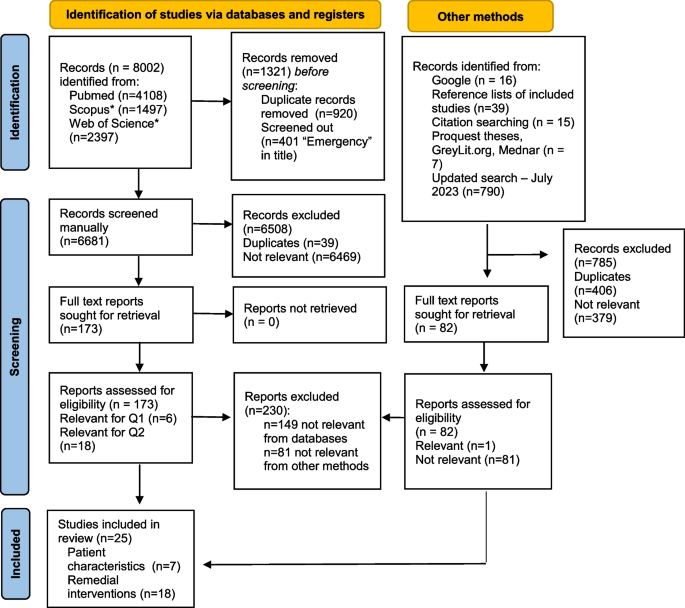

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.