Research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use: A bibliometric analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Sasin School of Management, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

- 2 Business Administration Division, Mahidol University International College, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand.

- PMID: 36458122

- PMCID: PMC9707397

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1017506

Despite their increasing ubiquity in people's lives and incredible advantages in instantly interacting with others, social media's impact on subjective well-being is a source of concern worldwide and calls for up-to-date investigations of the role social media plays in mental health. Much research has discovered how habitual social media use may lead to addiction and negatively affect adolescents' school performance, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships. The present study was conducted to review the extant literature in the domain of social media and analyze global research productivity during 2013-2022. Bibliometric analysis was conducted on 501 articles that were extracted from the Scopus database using the keywords social media addiction and problematic social media use. The data were then uploaded to VOSviewer software to analyze citations, co-citations, and keyword co-occurrences. Volume, growth trajectory, geographic distribution of the literature, influential authors, intellectual structure of the literature, and the most prolific publishing sources were analyzed. The bibliometric analysis presented in this paper shows that the US, the UK, and Turkey accounted for 47% of the publications in this field. Most of the studies used quantitative methods in analyzing data and therefore aimed at testing relationships between variables. In addition, the findings in this study show that most analysis were cross-sectional. Studies were performed on undergraduate students between the ages of 19-25 on the use of two social media platforms: Facebook and Instagram. Limitations as well as research directions for future studies are also discussed.

Keywords: bibliometric analysis; problematic social media use; research trends; social media; social media addiction.

Copyright © 2022 Pellegrino, Stasi and Bhatiasevi.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

Advertisement

Exploring the Association Between Social Media Addiction and Relationship Satisfaction: Psychological Distress as a Mediator

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 05 October 2021

- Volume 21 , pages 2037–2051, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Begum Satici ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2161-782X 1 ,

- Ahmet Rifat Kayis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4642-7766 2 &

- Mark D. Griffiths ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8880-6524 3

21k Accesses

10 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Social media use has become part of daily life for many people. Earlier research showed that problematic social media use is associated with psychological distress and relationship satisfaction. The aim of the present study was to examine the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between social media addiction (SMA) and romantic relationship satisfaction (RS). Participants comprised 334 undergraduates from four mid-sized universities in Turkey who completed an offline survey. The survey included the Relationship Assessment Scale, the Social Media Disorder Scale, and the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale. According to the results, there were significant correlations between all variables. The results also indicated that depression, anxiety, and stress partially mediated the impact of SMA on RS. Moreover, utilizing the bootstrapping procedure the study found significant associations between SMA and RS via psychological distress. Consequently, reducing social media use may help couples deal with romantic relationship dissatisfaction, thereby mitigating their depression, anxiety, and stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Assessing the mediating effect of relationship dynamics between perceptions of problematic media use and relationship satisfaction.

Todd A. Spencer, Amberly Lambertsen, … Brandon K. Burr

A two-study validation of a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction: RAS-1

Flóra Fülöp, Beáta Bőthe, … Gábor Orosz

Effects of attachment styles, dark triad, rejection sensitivity, and relationship satisfaction on social media addiction: A mediated model

Zeynep Işıl Demircioğlu & Aslı Göncü Köse

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Establishing social relationships is one of the basic needs of human beings (Heaney & Israel, 2008 ). How this basic need is met can vary greatly. In particular, technological developments, such as computers, the Internet, and smartphones have created new ways for people to communicate with each other. One of the most successful new means of communication is through social media. Social media involves many different communication (i.e., social networking) platforms. Among the most popular are platforms in Western countries are Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. These sites, which are accessed via the Internet, provide many opportunities for communication, such as voice and video messaging, photograph and video sharing, and creating profiles, through which individuals can introduce themselves and make connections with others.

The communication opportunities brought about by social networking sites (SNSs) allow for the development of social relationships (Fuchs, 2017 ; Hazar, 2011 ; Valentini, 2015 ). In addition, social media is used for a wider variety of purposes, including obtaining information, communicating, entertainment, playing games, and sharing photos, videos, and music (Griffiths, 2012 ). However, excessive use of social media including SNSs can cause negative effects (Griffiths, 2013 ; van den Eijnden et al., 2016 ). This phenomenon, which is sometimes referred as “social media addiction,” is defined as the irrational and excessive use of social media at a level that negatively affects the daily life of the user (Griffiths, 2012 ). When social media use reaches the level of addiction, it can prevent the establishment of real, face-to-face social relationships (Glaser et al., 2018 ; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017 ; Young, 2019 ). When general characteristics of social media addiction have been examined, it has been found that individuals tend to have restless thoughts concerning the urges and craving to be on social media, lose their self-control over their use of social media, spend excessive amounts of time staying on (or thinking about) social media which in turn lead to negative impacts on their relationships with their families and friends, and compromise their occupation and/or education (Andreassen et al., 2012 ; Griffiths et al., 2014 ). Therefore, examining social media addiction in terms of its effect on human relationships and mental health is an important pursuit.

Theoretical Framework

Social media addiction and relationship satisfaction.

Research into the effects of social media addiction on romantic relationships has increased (Abbasi, 2019a ; Demircioğlu & Köse, 2018 ). The literature suggests that social media addiction negatively affects romantic relationships due to its tendency to create jealousy and suspicion and facilitate deception between married couples and committed partners (Abbasi, 2019b ). Additionally, problematic social media use can hinder the development of face-to-face relationships (Glaser et al., 2018 ; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017 ; Pollet et al., 2011 ; Young, 2019 ). Therefore, it is possible that some couples’ relationships may become disrupted and that dissatisfaction may be experienced. In some cases, not only has social media use decreased the amount of relationships that individuals have in person, but it has also markedly impaired the quality of the time spent together. Therefore, it can be concluded that some couples may experience relationship dissatisfaction.

Similarly, social media addiction can result in low relationship satisfaction due to the existence of online alternative centers of attraction and investments of time and emotion outside the bilateral relationship in individuals aged between 18 and 73 years (Abbasi, 2019a ). In addition, social media addiction has also been associated with physical and emotional infidelity, romantic separation, decline in the quality of romantic relationships, and relationship dissatisfaction (e.g., Abbasi, 2019a , b ; Demircioğlu & Köse, 2018 ; Valenzuela et al., 2014 ). Therefore, these aforementioned findings indicate that social media addiction negatively affects relationship satisfaction.

Social Media Addiction and Psychological Distress

One of the most important consequences of social media addiction is the mental health of individuals. When social media use reaches the level of addiction, it can create stress and negatively affect mental health rather than being a method of healthy coping. This occurs because social media addiction triggers social media fatigue and, as a result, individuals may experience anxiety and depression (Dhir et al., 2018 ). Social media users may use social media as a means of diversion in order to cope with stress (van den Eijnden et al., 2016 ). However, social media addicts give a lower priority to hobbies, daily routines, and close relationships (Tutgun-Ünal & Deniz, 2015 ) which in turn lead to problems with daily functioning, completion of tasks, and relationship maintenance. This puts such individuals at risk for experiencing negative physical and psychological health.

In fact, some research has claimed that social media addiction triggers psychological distress factors, such as depression, anxiety (Woods & Scott, 2016 ), and stress (Larcombe et al., 2016 ). In addition, a meta-analysis synthesizing the findings of 13 studies found that social media addiction may increase depression, anxiety, and stress levels (Keles et al., 2020 ). In both meta-analyses and cross-sectional studies, it has been found that social media addiction can increase psychological distress (e.g., Hou et al., 2019 ; Keles et al., 2020 ; Marino et al., 2018 ; Meena et al., 2015 ). In sum, these findings consistently associate social media addiction with psychological distress.

Psychological Distress and Relationship Satisfaction

Individuals experiencing psychological discomfort often have non-functional communication styles characterized by highly negative behaviors, such as criticism, complaining, hostility, defensiveness, and tendency to end relationships. They also experience problems actively listening to others (Fincham et al., 2018 ). In this respect, psychological distress prevents healthy communication in relationships, and a lack of healthy communication may cause conflicts that can embitter psychological distress between couples. Such a situation can continue in a cyclical manner that prevents relationship satisfaction. In romantic relationships, couples are supposed to fulfill their partners’ emotional needs (Willard, 2011 ). When individuals have psychological problems due to social media addiction, they will ignore their partner’s emotional needs because they would be trying to deal with their own problems, which, in turn, may lead to lower relationship satisfaction.

When psychological distress and romantic relationship satisfaction are examined, it can be seen that much psychological distress, such as major depression, panic disorder, social phobia, general anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and mood disorder, positively predict relationship dissatisfaction (Whisman, 1999 ). On the other hand, it can also be seen that individuals who are sensitive to negative affect in romantic relationships and who can successfully stop these emotions early on and cope with their feelings are satisfied with their relationships (Fincham et al., 2018 ).

Couples who have high levels of stress are reported to experience less satisfaction in their relationships (Bodenmann et al., 2007 ). In addition, it is known that depression negatively predicts relationship satisfaction (Cramer, 2004a , b ; Tolpin et al., 2006 ). Therefore, it appears that psychological distress negatively affects relationship satisfaction.

The Present Study

The prevalence of the use of the internet and Internet-related tools has consistently increased year on year (Roser et al., 2020 ). Even though the social media use is widespread and facilitates communication when it is used normally, it can negatively affect daily life when it is used excessively by some individuals. Literature reviews have shown that social media addiction has been mostly studied in East Asian countries like China, Japan, and South Korea (e.g., Bian & Leung, 2015 ; Kwon et al., 2013 ; Tateno et al., 2019 ). In this respect, when the prevalence of social media use among Turkish people and the different cultural context of the present study are considered, the findings would arguably make important contributions to the current literature. Furthermore, the present study appears to be the first to examine the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction.

Older aged adolescents and emerging adults are inextricably connected with technology in terms of their social media use and stand out as an important risk group in relation to problematic social media use (Griffiths et al., 2014 ). Many young adults closely follow technological developments and often adopt every innovation that arises into their lives without wasting time (Kuyucu, 2017 ). When such use becomes problematic, some individuals experience serious difficulty in maintaining their mental health. For example, cross-sectional studies among adolescents (Woods & Scott, 2016 ) and young adults (Larcombe et al., 2016 ) have found that social media addiction can lead to stress, anxiety, and depression. Moreover, the establishment of close relationships as a young adult is an important stage of emotional and social development (Cashen & Grotevant, 2019 ; Orenstein, & Lewis, 2020 ). Romantic relationship satisfaction may be seen as an important indicator of young people’s ability to engage in intimacy in a healthy manner (Orenstein & Lewis, 2020 ). Therefore, the findings obtained as a result of examining the relationships between social media addiction, psychological distress, and romantic relationship satisfaction among young people will contribute to an understanding of the associations between the psychological and social variables regarding maintenance of their mental health and their success in establishing close relationships.

In previous studies of the variables examined in the present study, even though studies examining the three variables dichotomously have been conducted (e.g., Abbasi, 2019a , b ; Bodenmann et al., 2007 ; Keles et al., 2020 ; Larcombe et al., 2016 ; Whisman, 1999 ), no research examining social media addiction, psychological distress (depression, anxiety and stress), and romantic relationship satisfaction together has been published. In particular, there is no study examining the role of psychological distress mediating between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction. In this respect, the results of the present study may also allow the findings of previous studies (which have been conducted with the aim of identifying the relationship between these variables) to be evaluated from a wider perspective.

Consequently, given the aforementioned theoretical explanations and the research findings, it has been demonstrated that social media addiction appears to induce both psychological distress and a low level of romantic relationship satisfaction (e.g., Demircioğlu & Köse, 2018 ; Woods & Scott, 2016 ). This is due to the deterioration of individuals’ mental health that can arise as a result of social media addiction (Baker & Algorta, 2016 ; Dhir et al., 2018 ), and in contrast to the advantages of developing relationships, it can lead to romantic relationship dissatisfaction (Abbasi, 2019b ; Muise et al., 2009 ). Therefore, when the relationships between social media addiction, psychological distress, and romantic relationship satisfaction are evaluated simultaneously, psychological distress may represent a mediating variable between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction. Consequently, it was hypothesized that psychological distress would mediate the association between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction.

Participants and Procedure

The present cross-sectional study was carried out on a convenience sample of university students from three universities that are located in the west, middle, and east part of Turkey. A total of 350 surveys were originally distributed. Of these, 16 participants were removed because of incomplete data, yielding a final sample of 334 participants aged between 18 and 29 years ( M = 20.71 years, SD = 2.18). The participants comprised 214 females (64%) and 120 males (36%), of which 90 were freshmen, 87 were sophomores, 84 were junior students, and 73 were senior students. Participants reported that they were currently in a romantic relationship and reported having an average of 3.21 romantic relationships to date ( SD = 2.21). Table 1 shows the detailed demographic characteristics of the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from the volunteer participants prior to participation in the study. Research participants were assured of the confidentiality of the collected data. Data collection was carried out through a “paper-and-pencil” survey in the classroom environment. The surveys took less than 15 min to complete.

Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS)

The RAS was designed to assess general relationship satisfaction (Hendrick, 1988 ). Items (e.g., “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?”) utilize a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ( low ) to 7 ( high ). The total score ranges from 7 to 49. The higher the score, the higher the relationship satisfaction. Hendrick ( 1988 ) reported very good reliability. The RAS was adapted into Turkish by Curun ( 2001 ) with very good internal consistency. In the present study, the internal consistency of this scale was also good ( α = 0.80).

Social Media Disorder Scale (SMD)

The SMD was designed to assess overall social media addiction, and the items were developed by adapting the DSM-5 criteria for Internet gaming disorder (van den Eijnden et al., 2016 ). This scale includes nine items (e.g., “… regularly found that you can't think of anything else but the moment that you will be able to use social media again?”) to which participants indicate their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 ( never ) to 4 ( always ). The total score ranges from 0 to 36. The higher the score, the higher the risk of social media addiction. The SMD was adapted to Turkish by Savci et al. ( 2018 ) and has very good internal consistency. In the present study, the internal consistency of this scale was also very good ( α = 0.88).

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21)

The DASS was designed to assess the level of psychological distress (Henry & Crawford, 2005 ). The scale consists of 21 items that are rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 ( did not apply to me at all ) to 3 ( applied to me very much or most of the time ) and comprises three sub-scales: depression (seven items; e.g., “I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things”), anxiety (seven items; e.g., “I felt I was close to panic”), and stress (seven items; “I found myself getting agitated”). The scores range from 0 to 21 for each sub-scale. The DASS-21 subscales’ scores were multiplied by two based on Lovibund and Lovibond’s ( 1995 ) suggestion to the cut-offs (see Appendix 1 ). The DASS-21 was adapted to Turkish by Yilmaz et al. ( 2017 ) with good to very good internal consistencies. In the present study, the internal consistency of the sub-scales were all very good ( α = 0.89, 0.82, 0.85, respectively).

Statistical Analyses

Pearson correlations, means, and standard deviations were examined as preliminary analyses for all study variables. To examine whether the association between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction was mediated by psychological distress, the mediation model was calculated using the PROCESS macro (model 4), developed by Hayes ( 2018 ). As recommended by Hayes ( 2018 ), all regression/path coefficients are in unstandardized form. A total of 10,000 bootstrap samples were generated and bias corrected 95% confidence intervals calculated.

Written informed consent was obtained from the volunteer participants prior to participation in the study. This research was approved by Artvin Coruh University Scientific Research and Ethical Review Board (REF: E.5375).

Descriptive Statistics

Bivariate Pearson correlations among study variables were investigated (see Table 2 ). As expected, social media addiction was significantly and positively correlated with depression, anxiety, and stress. There was a significant negative correlation between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction.

Results indicated that 156 participants had no depressive symptoms (46.7%), 54 participants had mild depressive symptoms (16.2%), and the remainder had depressive symptoms (16.5% moderate, 9.9% severe, and 10.8% extremely severe). Moreover, 101 participants had no anxiety symptoms (30.2%), 30 participants had mild anxiety symptoms (9.0%), and the remainder had anxiety symptoms (20.4% moderate, 15.6% severe, and 24.9% extremely severe). Finally, 163 participants had no stress symptoms (48.8%), 47 participants had mild depressive symptoms (14.1%), and the remainder had stress symptoms (17.7% moderate, 12.6% severe, and 6.9% extremely severe) (see Appendix 1 ).

Statistical Assumption Tests

Prior to mediation analysis, statistical assumptions were evaluated. Skewness and kurtosis values (> ± 2; George & Mallery, 2003 ) were checked for normality, and there were no violations (see Table 3 ). All reliability coefficients were above Nunnally and Bernstein’s ( 1994 ) 0.70 criterion. Multicollinearity was checked with variance inflated factor (VIF), tolerance, and Durbin-Watson (DW) value. The results showed that VIF ranged from 1.47 to 2.09 and tolerance ranged from 0.48 to 0.87. These findings also showed that there was no multiple linearity problem according to Field’s ( 2013 ) recommendation. Also, the DW value was 1.82 indicating no significant correlations between the residuals.

Mediation Analyses

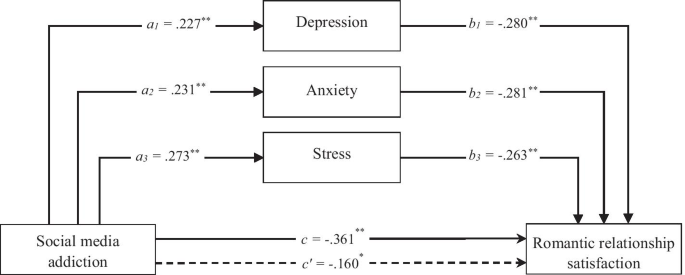

Applying PROCESS model 4, the analysis assessed whether psychological distress mediated the relationship between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction (see Table 4 ; Fig. 1 ). The results showed a significant total direct effect ( path c ; without mediator) of social media addiction on relationship satisfaction (B = − 0.36, t (334) = − 4.74, p = 0.001, 95% CI = − 0.51, − 0.21), significant direct effect ( path c ; with mediator) (B = − 0.16, t (334) = − 2.11, p = 0.03, 95% CI = − 0.04, − 0.01), and a significant indirect effect via psychological distress (total B = − 0.20, 95% CI = − 0.29, − 0.12).

The mediation model. * p < .05. ** p < .001

The results also showed that the social media addiction was associated with higher depression scores (path a 1 ; B = 0.23, p = 0.001), anxiety scores (path a 2 ; B = 0.23, p = 0.001), and stress scores (path a 3 ; B = 0.27, p = 0.001), and these, in turn, were negatively associated with relationship satisfaction (path b 1, b 2, b 3 ; B = − 0.28, B = − 0.28, B = − 0.26, all p values < 0.05, respectively).

In contemporary society, rapidly developing technology has entered human life, but some individuals may have difficulty in adapting to the innovations brought by such technology. Consequently, some individuals may experience psychological and social problems. Social media use, which has markedly increased in the past decade, can cause psychological distress (e.g., Keles et al., 2020 ; Marino et al., 2018 ) and the deterioration of interpersonal relationships (e.g., Glaser et al., 2018 ; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017 ; Young, 2019 ) among a minority of individuals. In this context, the main purpose of the present study was to evaluate the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction.

According to the findings, a high level of social media addiction leads to a decrease in relationship satisfaction. Consequently, the first hypothesis was confirmed. A recent study conducted by Abbasi ( 2019b ) found that social media addiction was negatively associated with romantic relationship commitment. In another recent study, it was emphasized that social media addiction results in deception between couples through social media and may lead to the deterioration of relationships as a consequence (Abbasi, 2019a ). In addition, social media addiction not only leads to physical and emotional deception but also appears to negatively impact on the quality of romantic relationships (Demircioğlu & Köse 2018 ; Valenzuela et al., 2014 ). Therefore, the findings obtained in the present study are in line with the findings of previous research.

In the study here, the findings showed that a high level of social media addiction appears to result in psychological distress. Dhir et al. ( 2018 ) argued that social media addiction triggers social media fatigue, leading to anxiety and depression. Similarly, social media addiction has been found to be associated with depression, anxiety (Woods & Scott, 2016 ) and stress (Larcombe et al., 2016 ). In addition, a recent meta-analysis also concluded that social media addiction is closely and positively associated depression, anxiety and stress (Marino et al., 2018 ). Therefore, the findings of the present study are consistent with previous research.

Thirdly, the findings indicate that individuals who experience psychological distress have a low level of satisfaction in their romantic relationships. Whisman ( 1999 ) found that psychological distress positively predicted relationship dissatisfaction. It has also been suggested that couples with high levels of stress experience dissatisfaction in their romantic relationships (Bodenmann et al., 2007 ). In addition, there have also been a number of studies which indicate that the relationship satisfaction of individuals with high levels of depression is low (Cramer, 2004a , b ; Tolpin et al., 2006 ). In this respect, the findings obtained from the present study are similar to the findings of the previous studies.

Within the scope of this study, it was hypothesized that psychological distress would mediate between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction. In this sense, the study showed that social media addiction predicted romantic relationship satisfaction, partially mediated by psychological distress. Consequently, the fourth hypothesis of the research was also confirmed. No previous studies have examined the effect of psychological distress in the relationship between social media addiction and relationship satisfaction. However, there are research findings which provide evidence that social media addiction predicts both psychological distress (e.g., Larcombe et al., 2016 ; Woods & Scott, 2016 ) and relationship dissatisfaction (e.g., Demircioğlu & Köse, 2018 ; Valenzuela et al., 2014 ) and that psychological distress predicts relationship dissatisfaction (e.g., Bodenmann et al., 2007 ; Whisman, 1999 ). Due to the consideration of a variable’s mediating conditions (Barron & Kenny, 1986 ), it may be asserted that the findings of the previous studies in the literature and the findings of this research are consistent. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that technological addiction, such as Internet addiction and smartphone addiction, is associated with psychological distress (McNicol & Thorsteinsson, 2017 ; Samaha & Hawi, 2016 ; Young & Rogers, 1998 ). Psychological distress may also predict variables such as closeness in relationships (Manne et al., 2010 ), dating violence (Cascardi, 2016 ), and social support (Robitaille et al., 2012 ) which are based on interpersonal relationships. It is therefore suggested that there is similarity between these findings and the findings of the present study. Consequently, it may be that the results of the studies conducted previously support the findings of this the present research indirectly, if not directly.

In the study here, the mediating role of psychological distress in the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction was investigated. However, there could be some other variables that can mediate the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction. For instance, romantic relationships are considered interpersonal (Knap et al., 2002 ); therefore, it can be assumed that interpersonal relationships and communication skills can be seen as potential mediators of the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction. Additionally, given that psychological problems are the indicators of poor mental health (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ), it can be assumed that variables (i.e., other indicators of poor mental health such as burnout, somatization, and hostility) would mediate the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction. Therefore, future studies should investigate such relationships more closely.

When the role of social media addiction in the development of psychological distress is considered, it is necessary for social media addiction to be included in the process of forming the content of the intervention programs that aim to treat psychological distress. As such, it is interesting that an intervention program aimed at decreasing the level of social media addiction was also found to have a beneficial impact on individuals’ mental health (Hou et al., 2019 ). Likewise, the treatment of couples’ social media usage habits in family and couple therapies may be effective in terms of the efficacy of the therapy, since social media addiction decreases satisfaction in romantic relationships. Moreover, given the mediation relationships in the present research, the results may provide a more holistic viewpoint for mental health professionals which consider all of the three variables (social media addiction, psychological distress, and romantic relationship satisfaction) rather than a focus on only one. In this context, the following suggestions are made: to prevent social media addiction, effective Internet use skills can be taught to couples. In addition, awareness-raising skills such as yoga and meditation could be provided to individuals to protect them from social media addiction and psychological distress.

In terms of the study’s participatory group, it is significant that social media addiction (Kittinger et al., 2012 ; Koc & Gulyagci, 2013 ), psychological distress (Canby et al., 2015 ; Larcombe et al., 2016 ), and relationship satisfaction problems (Bruner et al., 2015 ; Roberts & David, 2016 ) are frequently experienced by university students. Consequently, the findings of the present study may be of particular help to specialists who work in the psychological counseling centers of universities. Within this framework, meetings, conferences, and psycho-educational group activities could be carried out to improve relationship building skills, as well as activities preventing social media addiction and psychological distress.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, the data comprised self-report scales, which may decrease internal reliability, a limitation which may be prevented through the use of different methods of data collection. Secondly, the generalizability of the findings is limited since the sample was based on convenience sampling. Thirdly, the research design was cross-sectional. This may make it difficult to explain the cause-effect relationship of variables in the study, and therefore, experimental and longitudinal studies are recommended in future research which should examine the relationship between these variables. Finally, only the mediating role of psychological distress was examined in the research. Other possible mediating variables were not examined.

In the present research, the mediation of psychological distress in the relationship between social media addiction and romantic relationship satisfaction was empirically tested. Results showed that social media addiction predicted the partial mediation of depression, anxiety, and stress on romantic relationship satisfaction. In other words, social media addiction apparently increased individuals’ depression, anxiety, and stress levels, and this situation decreased the level of satisfaction in individual’s romantic relationships. In the present study, psychological and social variables were examined simultaneously. Overall, this study suggests that social media addiction may have a meaningful but negative impact on romantic relationship satisfaction via depression, anxiety, and stress.

Abbasi, I. S. (2019a). Social media addiction in romantic relationships: Does user’s age influence vulnerability to social media infidelity? Personality and Individual Differences, 139 , 277–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.038

Article Google Scholar

Abbasi, I. S. (2019b). Social media and committed relationships: What factors make our romantic relationship vulnerable? Social Science Computer Review, 37 (3), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318770609

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Book Google Scholar

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110 (2), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Baker, D. A., & Algorta, G. P. (2016). The relationship between online social networking and depression: A systematic review of quantitative studies. CyberPsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19 (11), 638–648. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0206

Barron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bian, M., & Leung, L. (2015). Linking loneliness, shyness, smartphone addiction symptoms, and patterns of smartphone use to social capital. Social Science Computer Review, 33 (1), 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314528779

Bodenmann, G., Ledermann, T., & Bradbury, T. N. (2007). Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships, 14 (4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x

Bruner, M. R., Kuryluk, A. D., & Whitton, S. W. (2015). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom levels and romantic relationship quality in college students. Journal of American College Health, 63 (2), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2014.975717

Canby, N. K., Cameron, I. M., Calhoun, A. T., & Buchanan, G. M. (2015). A brief mindfulness intervention for healthy college students and its effects on psychological distress, self-control, meta-mood, and subjective vitality. Mindfulness, 6 (5), 1071–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0356-5

Cascardi, M. (2016). From violence in the home to physical dating violence victimization: The mediating role of psychological distress in a prospective study of female adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45 (4), 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0434-1

Cashen, K. K., & Grotevant, H. D. (2019). Relational competence in emerging adult adoptees: Conceptualizing competence in close relationships. Journal of Adult Development . Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-019-09328-x

Cramer, D. (2004a). Emotional support, conflict, depression, and relationship satisfaction in a romantic partner. Journal of Psychology, 138 (6), 532–542. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.138.6.532-542

Cramer, D. (2004b). Satisfaction with a romantic relationship, depression, support and conflict. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 77 (4), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1348/1476083042555389

Curun, F. (2001). The effects of sexism and sex role orientation on relationship satisfaction . [Unpublished Master's thesis, Middle East Technical University], Ankara, Turkey.

Demircioğlu, Z. I., & Köse, A. G. (2018). Effects of attachment styles, dark triad, rejection sensitivity, and relationship satisfaction on social media addiction: A mediated model. Current Psychology . Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9956-x

Dhir, A., Yossatorn, Y., Kaur, P., & Chen, S. (2018). Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing – A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management, 40 , 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.012

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage.

Google Scholar

Fincham, F. D., Rogge, R., & Beach, S. R. H. (2018). Relationship satisfaction. In A. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 579–594). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.032

Chapter Google Scholar

Fuchs, C. (2017). Social media: A critical introduction . Sage.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference . Allyn and Bacon.

Glaser, P., Liu, J. H., Hakim, M. A., Vilar, R., & Zhang, R. (2018). Is social media use for networking positive or negative? Offline social capital and internet addiction as mediators for the relationship between social media use and mental health. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 47 (3), 12–18.

Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Facebook addiction: Concerns, criticism, and recommendations: A response to Andreassen and colleagues. Psychological Reports, 110 , 518–520. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.07.18.PR0.110.2.518-520

Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Social networking addiction: Emerging themes and issues. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 4 (5), e118. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6105.1000e118

Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In K. Rosenberg & L. Feder (Eds.), Behavioral Addictions: Criteria, Evidence and Treatment (pp. 119–141). Elsevier.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach . Guilford Publications.

Hazar, M. (2011). Sosyal medya bağımlılığı: Bir alan çalışması. İletişim, Kuram Ve Araştırma Dergisi, 32 , 151–175.

Heaney, C. A., & Israel, B. A. (2008). Social networks and social support. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 189–210). Wiley.

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50 , 93–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/352430

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44 (2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

Hou, Y., Xiong, D., Jiang, T., Song, L., & Wang, Q. (2019). Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 13 (1), 4. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-1-4

Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25 (1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Kittinger, R., Correia, C. J., & Irons, J. G. (2012). Relationship between Facebook use and problematic internet use among college students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15 (6), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0410

Knap, M. L., Daly, J. A., Albada, K. F., & Miller, G. R. (2002). Handbook of interpersonal communication . Sage.

Koc, M., & Gulyagci, S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16 (4), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0249

Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14 (3), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kuyucu, M. (2017). Y kuşağı ve teknoloji: Y kuşağının iletişim teknolojilerini kullanım alışkanlıkları. Gümüşhane Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Elektronik Dergisi, 5 (2), 845–872. https://doi.org/10.19145/e-gifder.285714

Kwon, M., Kim, D. J., Cho, H., & Yang, S. (2013). The smartphone addiction scale: Development and validation of a short version for adolescents. PLoS ONE, 8 (12), e83558. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083558

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Larcombe, W., Finch, S., Sore, R., Murray, C. M., Kentish, S., Mulder, R. A., … & Williams, D. A. (2016). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological distress among students at an Australian university. Studies in Higher Education , 41 (6), 1074-1091. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.966072

Lovibund, S., & Lovibund, P. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales . Psychology Foundation.

Maier, C., Laumer, S., Weinert, C., & Weitzel, T. (2015). The effects of technostress and switching stress on discontinued use of social networking services: A study of Facebook use. Information Systems Journal, 25 (3), 275–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12068

Manne, S., Badr, H., Zaider, T., Nelson, C., & Kissane, D. (2010). Cancer-related communication, relationship intimacy, and psychological distress among couples coping with localized prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 4 (1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-009-0109-y

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226 , 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007

McNicol, M. L., & Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2017). Internet addiction, psychological distress, and coping responses among adolescents and adults. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20 (5), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0669

Meena, P. S., Soni, R., Jain, M., & Paliwal, S. (2015). Social networking sites addiction and associated psychological problems among young adults: A study from North India. Sri Lanka Journal of Psychiatry, 6 (1), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljpsyc.v6i1.8055

Muise, A., Christofides, E., & Desmarais, S. (2009). More information than you ever wanted: Does Facebook bring out the green-eyed monster of jealousy? CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12 (4), 441–444. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0263

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2020). Eriksons stages of psychosocial development. In StatPearls [Internet] . StatPearls Publishing. Retrived May 12, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556096/

Pollet, T. V., Roberts, S. G., & Dunbar, R. I. (2011). Use of social network sites and instant messaging does not lead to increased offline social network size, or to emotionally closer relationships with offline network members. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14 (4), 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0161

Roberts, J. A., & David, M. E. (2016). My life has become a major distraction from my cell phone: Partner phubbing and relationship satisfaction among romantic partners. Computers in Human Behavior, 54 , 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.058

Robitaille, A., Orpana, H., & McIntosh, C. N. (2012). Reciprocal relationship between social support and psychological distress among a national sample of older adults: An autoregressive cross-lagged model. Canadian Journal on Aging/la Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 31 (1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000560

Roser, M., Ritchie, H., & Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2020). Internet. Retrieved May 12, 2020, from https://ourworldindata.org/internet

Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior, 57 , 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.045

Savci, M., Ercengiz, M., & Aysan, F. (2018). Turkish adaptation of the social media disorder scale in adolescents. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 55 (3), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.29399/npa.19285

Tateno, M., Kim, D. J., Teo, A. R., Skokauskas, N., Guerrero, A. P., & Kato, T. A. (2019). Smartphone addiction in Japanese college students: usefulness of the Japanese version of the smartphone addiction scale as a screening tool for a new form of internet addiction. Psychiatry Investigation, 16 (2), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2018.12.25.2

Tolpin, L. H., Cohen, L. H., Gunthert, K. C., & Farrehi, A. (2006). Unique effects of depressive symptoms and relationship satisfaction on exposure and reactivity to daily romantic relationship stress. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25 (5), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.5.565

Tutgun-Ünal, A., & Deniz, L. (2015). Development of the social media addiction scale. Online Academic Journal of Information Technology, 6 (21), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.5824/1309-1581.2015.4.004.x

Valentini, C. (2015). Is using social media “good” for the public relations profession? A Critical Reflection. Public Relations Review, 41 (2), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.11.009

Valenzuela, S., Halpern, D., & Katz, J. E. (2014). Social network sites, marriage well-being and divorce: Survey and state-level evidence from the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.034

van den Eijnden, R. J., Lemmens, J. S., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The social media disorder scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 61 , 478–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038

Whisman, M. A. (1999). Marital dissatisfaction and psychiatric disorders: Results from the national comorbidity survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108 (4), 701–706. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.108.4.701

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Willard, F. H., Jr. (2011). His needs, her needs: Building an affair-proof marriage . Revell.

Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). # Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51 , 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008

Yen, J. Y., Ko, C. H., Yen, C. F., Chen, S. H., Chung, W. L., & Chen, C. C. (2008). Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with Internet addiction: Comparison with substance use. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62 (1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01770.x

Yılmaz, Ö., Boz, H., & Arslan, A. (2017). Depresyon anksiyete stres ölçeğinin (DASS 21) Türkçe kısa formunun geçerlilik-güvenilirlik çalışması. Finans Ekonomi Ve Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, 2 (2), 78–91.

Young, K. S., & Rogers, R. C. (1998). The relationship between depression and Internet addiction. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1 (1), 25–28. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.25

Young, G. K. (2019). Examination of communication and social media usage among socially anxious individuals . [Doctoral dissertation, University of Mississippi]. USA.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychological Counselling, Artvin Coruh University, Artvin, Turkey

Begum Satici

Department of Psychological Counselling, Kastamonu University, Kastamonu, Turkey

Ahmet Rifat Kayis

International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Department, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

Mark D. Griffiths

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark D. Griffiths .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University’s Research Ethics Board and with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale: Cut-Off Criteria and Distribution of Participants

- Scores on the DASS-21 are multiplied by 2 to calculate the final score

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Satici, B., Kayis, A.R. & Griffiths, M.D. Exploring the Association Between Social Media Addiction and Relationship Satisfaction: Psychological Distress as a Mediator. Int J Ment Health Addiction 21 , 2037–2051 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00658-0

Download citation

Accepted : 13 September 2021

Published : 05 October 2021

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00658-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media addiction

- Problematic social media use

- Online addiction

- Psychological distress

- Relationship satisfaction

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Teens and social media: Key findings from Pew Research Center surveys

For the latest survey data on social media and tech use among teens, see “ Teens, Social Media, and Technology 2023 .”

Today’s teens are navigating a digital landscape unlike the one experienced by their predecessors, particularly when it comes to the pervasive presence of social media. In 2022, Pew Research Center fielded an in-depth survey asking American teens – and their parents – about their experiences with and views toward social media . Here are key findings from the survey:

Pew Research Center conducted this study to better understand American teens’ experiences with social media and their parents’ perception of these experiences. For this analysis, we surveyed 1,316 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17, along with one parent from each teen’s household. The survey was conducted online by Ipsos from April 14 to May 4, 2022.

This research was reviewed and approved by an external institutional review board (IRB), Advarra, which is an independent committee of experts that specializes in helping to protect the rights of research participants.

Ipsos invited panelists who were a parent of at least one teen ages 13 to 17 from its KnowledgePanel , a probability-based web panel recruited primarily through national, random sampling of residential addresses, to take this survey. For some of these questions, parents were asked to think about one teen in their household. (If they had multiple teenage children ages 13 to 17 in the household, one was randomly chosen.) This teen was then asked to answer questions as well. The parent portion of the survey is weighted to be representative of U.S. parents of teens ages 13 to 17 by age, gender, race, ethnicity, household income and other categories. The teen portion of the survey is weighted to be representative of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 who live with parents by age, gender, race, ethnicity, household income and other categories.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

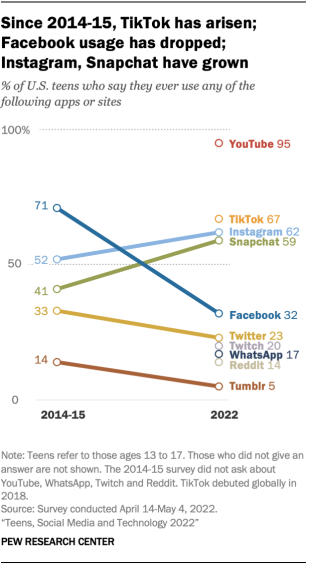

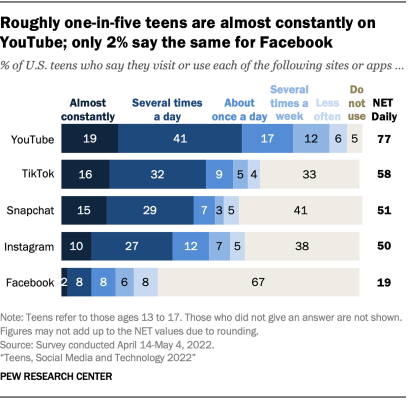

Majorities of teens report ever using YouTube, TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat. YouTube is the platform most commonly used by teens, with 95% of those ages 13 to 17 saying they have ever used it, according to a Center survey conducted April 14-May 4, 2022, that asked about 10 online platforms. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, followed by roughly six-in-ten who say they use Instagram (62%) and Snapchat (59%). Much smaller shares of teens say they have ever used Twitter (23%), Twitch (20%), WhatsApp (17%), Reddit (14%) and Tumblr (5%).

Facebook use among teens dropped from 71% in 2014-15 to 32% in 2022. Twitter and Tumblr also experienced declines in teen users during that span, but Instagram and Snapchat saw notable increases.

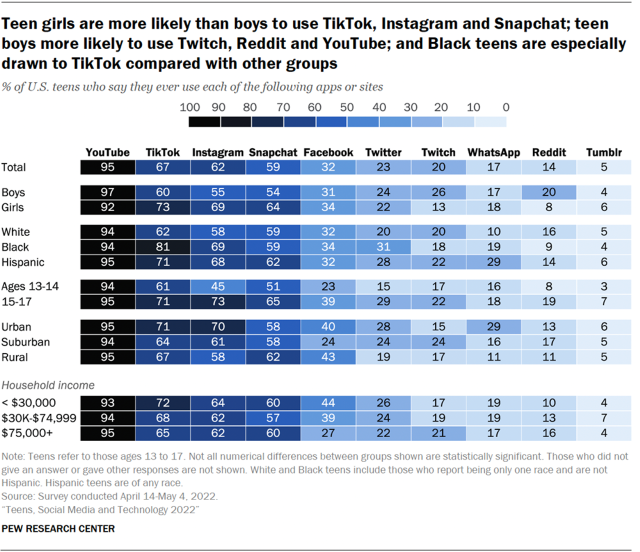

TikTok use is more common among Black teens and among teen girls. For example, roughly eight-in-ten Black teens (81%) say they use TikTok, compared with 71% of Hispanic teens and 62% of White teens. And Hispanic teens (29%) are more likely than Black (19%) or White teens (10%) to report using WhatsApp. (There were not enough Asian teens in the sample to analyze separately.)

Teens’ use of certain social media platforms also varies by gender. Teen girls are more likely than teen boys to report using TikTok (73% vs. 60%), Instagram (69% vs. 55%) and Snapchat (64% vs. 54%). Boys are more likely than girls to report using YouTube (97% vs. 92%), Twitch (26% vs. 13%) and Reddit (20% vs. 8%).

Majorities of teens use YouTube and TikTok every day, and some report using these sites almost constantly. About three-quarters of teens (77%) say they use YouTube daily, while a smaller majority of teens (58%) say the same about TikTok. About half of teens use Instagram (50%) or Snapchat (51%) at least once a day, while 19% report daily use of Facebook.

Some teens report using these platforms almost constantly. For example, 19% say they use YouTube almost constantly, while 16% and 15% say the same about TikTok and Snapchat, respectively.

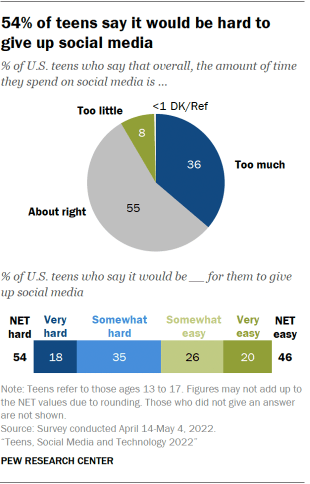

More than half of teens say it would be difficult for them to give up social media. About a third of teens (36%) say they spend too much time on social media, while 55% say they spend about the right amount of time there and just 8% say they spend too little time. Girls are more likely than boys to say they spend too much time on social media (41% vs. 31%).

Teens are relatively divided over whether it would be hard or easy for them to give up social media. Some 54% say it would be very or somewhat hard, while 46% say it would be very or somewhat easy.

Girls are more likely than boys to say it would be difficult for them to give up social media (58% vs. 49%). Older teens are also more likely than younger teens to say this: 58% of those ages 15 to 17 say it would be very or somewhat hard to give up social media, compared with 48% of those ages 13 to 14.

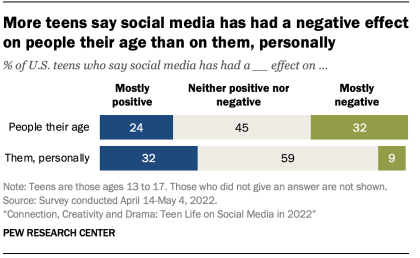

Teens are more likely to say social media has had a negative effect on others than on themselves. Some 32% say social media has had a mostly negative effect on people their age, while 9% say this about social media’s effect on themselves.

Conversely, teens are more likely to say these platforms have had a mostly positive impact on their own life than on those of their peers. About a third of teens (32%) say social media has had a mostly positive effect on them personally, while roughly a quarter (24%) say it has been positive for other people their age.

Still, the largest shares of teens say social media has had neither a positive nor negative effect on themselves (59%) or on other teens (45%). These patterns are consistent across demographic groups.

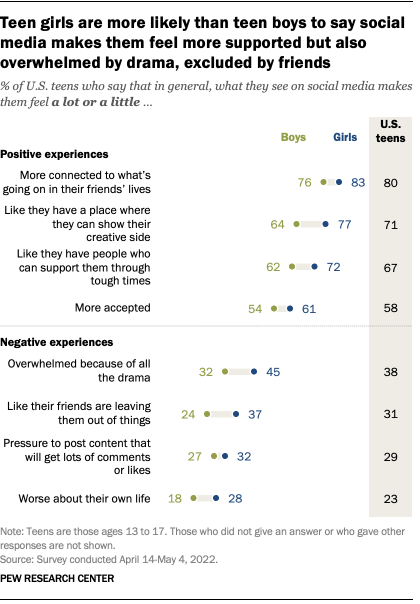

Teens are more likely to report positive than negative experiences in their social media use. Majorities of teens report experiencing each of the four positive experiences asked about: feeling more connected to what is going on in their friends’ lives (80%), like they have a place where they can show their creative side (71%), like they have people who can support them through tough times (67%), and that they are more accepted (58%).

When it comes to negative experiences, 38% of teens say that what they see on social media makes them feel overwhelmed because of all the drama. Roughly three-in-ten say it makes them feel like their friends are leaving them out of things (31%) or feel pressure to post content that will get lots of comments or likes (29%). And 23% say that what they see on social media makes them feel worse about their own life.

There are several gender differences in the experiences teens report having while on social media. Teen girls are more likely than teen boys to say that what they see on social media makes them feel a lot like they have a place to express their creativity or like they have people who can support them. However, girls also report encountering some of the pressures at higher rates than boys. Some 45% of girls say they feel overwhelmed because of all the drama on social media, compared with 32% of boys. Girls are also more likely than boys to say social media has made them feel like their friends are leaving them out of things (37% vs. 24%) or feel worse about their own life (28% vs. 18%).

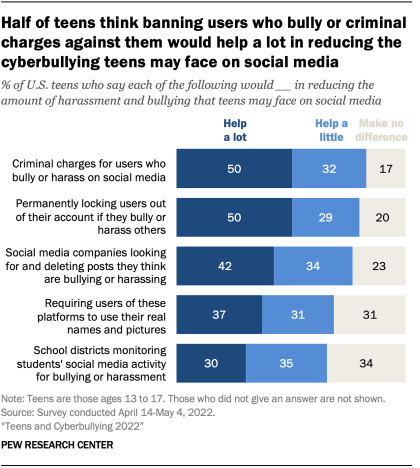

When it comes to abuse on social media platforms, many teens think criminal charges or permanent bans would help a lot. Half of teens think criminal charges or permanent bans for users who bully or harass others on social media would help a lot to reduce harassment and bullying on these platforms.

About four-in-ten teens say it would help a lot if social media companies proactively deleted abusive posts or required social media users to use their real names and pictures. Three-in-ten teens say it would help a lot if school districts monitored students’ social media activity for bullying or harassment.

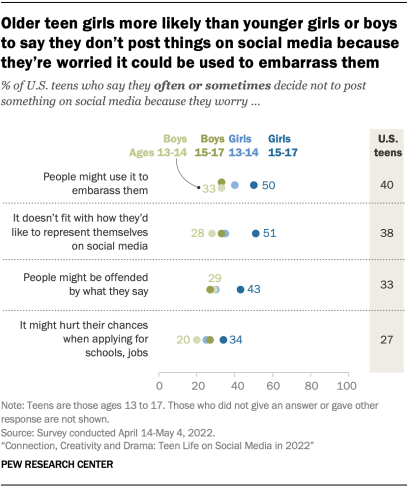

Some teens – especially older girls – avoid posting certain things on social media because of fear of embarrassment or other reasons. Roughly four-in-ten teens say they often or sometimes decide not to post something on social media because they worry people might use it to embarrass them (40%) or because it does not align with how they like to represent themselves on these platforms (38%). A third of teens say they avoid posting certain things out of concern for offending others by what they say, while 27% say they avoid posting things because it could hurt their chances when applying for schools or jobs.

These concerns are more prevalent among older teen girls. For example, roughly half of girls ages 15 to 17 say they often or sometimes decide not to post something on social media because they worry people might use it to embarrass them (50%) or because it doesn’t fit with how they’d like to represent themselves on these sites (51%), compared with smaller shares among younger girls and among boys overall.

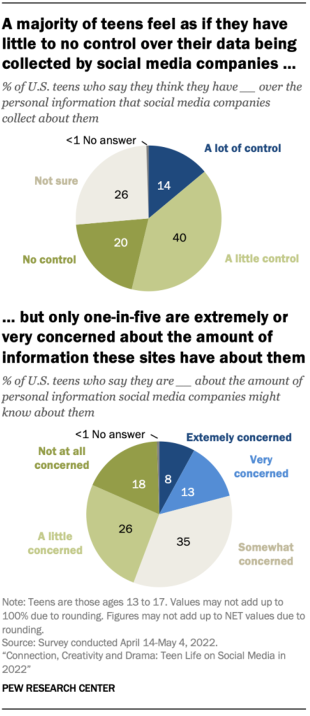

Many teens do not feel like they are in the driver’s seat when it comes to controlling what information social media companies collect about them. Six-in-ten teens say they think they have little (40%) or no control (20%) over the personal information that social media companies collect about them. Another 26% aren’t sure how much control they have. Just 14% of teens think they have a lot of control.

Despite many feeling a lack of control, teens are largely unconcerned about companies collecting their information. Only 8% are extremely concerned about the amount of personal information that social media companies might have and 13% are very concerned. Still, 44% of teens say they have little or no concern about how much these companies might know about them.

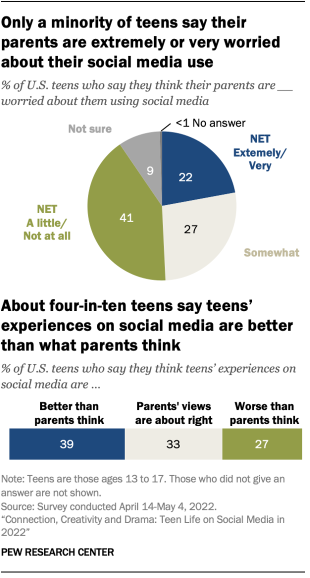

Only around one-in-five teens think their parents are highly worried about their use of social media. Some 22% of teens think their parents are extremely or very worried about them using social media. But a larger share of teens (41%) think their parents are either not at all (16%) or a little worried (25%) about them using social media. About a quarter of teens (27%) fall more in the middle, saying they think their parents are somewhat worried.

Many teens also believe there is a disconnect between parental perceptions of social media and teens’ lived realities. Some 39% of teens say their experiences on social media are better than parents think, and 27% say their experiences are worse. A third of teens say parents’ views are about right.

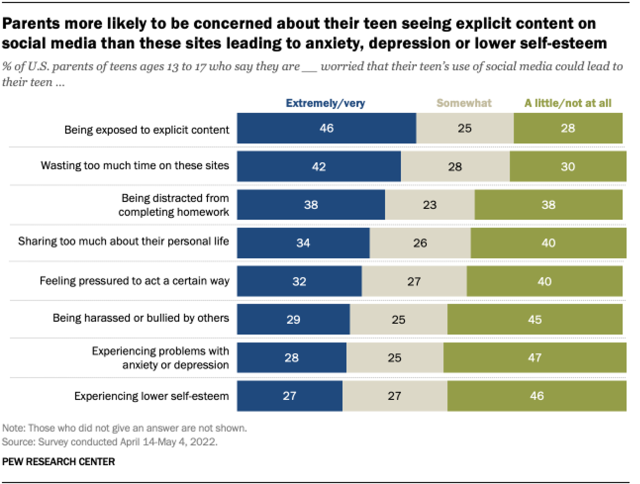

Nearly half of parents with teens (46%) are highly worried that their child could be exposed to explicit content on social media. Parents of teens are more likely to be extremely or very concerned about this than about social media causing mental health issues like anxiety, depression or lower self-esteem. Some parents also fret about time management problems for their teen stemming from social media use, such as wasting time on these sites (42%) and being distracted from completing homework (38%).

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

CORRECTION (May 17, 2023): In a previous version of this post, the percentages of teens using Instagram and Snapchat daily were transposed in the text. The original chart was correct. This change does not substantively affect the analysis.

- Age & Generations

- Age, Generations & Tech

- Internet & Technology

- Platforms & Services

- Social Media

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

How Teens and Parents Approach Screen Time

Who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, older workers are growing in number and earning higher wages, teens, social media and technology 2023, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Quantitative Research on the Level of Social Media Addiction Among Young People in Turkey

Internet technology today shows a quick progress, and social networks increase their number of users on each day. Social networking, which is one of the main indicators of the technology era, attracts people of all ages while the virtual world goes beyond the real life via the applications it offers. Especially young people show an intense interest in social media which is an extension of the Internet technology. Social media addiction is increasing both in Turkey and all around the world. This study aims to determine the level of social media addiction in young people in Turkey, and to make suggestions on the prevention of the addiction while stating the current work carried out on the subject in Turkey. Survey type research model is used in the study, and social media addiction is examined in depth to determine causes of the addiction among young people. In this study, the addiction factor of the Social Networking Status Scale is used as a data collection tool to measure social media addiction among young people. The scale has three factors including addiction, ethics and convergence, and it is a reliable and valid scale, as the reliability and validity of the scale had been tested. The study is conducted on 271 students between the ages of 13-19. It has been found that gender (t=0.406; P>0.05) makes no significant difference in social media addiction while the factors of age (F=6.256; P<0.05), daily time spent on the Internet (F=44.036; P<0.05) and daily frequency of visiting social media profiles (F=53.56; P<0.05) make significant differences in addiction level. The results have showed that low addiction level of 14-year group increases with age up to 17 years, and the level decreases in 18-year group. Social media addiction level shows a dramatic increase also in the case of daily time spent on the Internet increases. More frequent daily visits to social media profiles increase the addiction as well. The study also provides suggestions on possible actions to prevent addiction.

Related Papers

Taner Kizilhan

Considering that social media addiction is probably the most recent type of technology addiction, the present study was designed based on the six components suggested by Griffiths (2013). Toward the main purpose of the study, the "Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale" was adapted to social media addiction and translated into Turkish. After the validation process, it was administered to a total of 700 students; of them 397 were high school students and 303 were university students. The data collection instrument included 18 five-point Likert-type items in six categories, along with 5 structured items regarding demographics of the respondents. In addition to the original findings of the present study, similar research on social media addiction in some other countries were examined for comparisons. The results showed that both university students and high school students have a moderate level of addiction to social media. Being a university or high school student does not make any difference on the level of social media addiction. However, significant differences were found regarding gender, duration of use, department at the university, and type of high school. Finally, the results of the study show certain similarities and a few differences with the results of the studies conducted in other countries.

European Journal of Educational Sciences

European Journal of Educational Science

This study aimed to investigate the level of social media addiction among university students. The sample group comprised a total of 238 participants, 56.7% of whom are female and 43.3% of whom are male, enrolled at Istanbul University-Cerrahpasa Faculty of Sports Sciences. The data were collected using a personal information form and the 5-point Likert type "Social Media Addiction Scale" developed by Tutgun-Ünal and Deniz (2015), including 41 items and four sub-dimensions. Descriptive statistical methods, including percentage and frequency, were employed in the data analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was carried out to check whether the data were normally distributed, suggesting a normal distribution. Independent sample t-test for bivariate data and one-way ANOVA test for more than two variables were also performed. The research findings indicated a significant difference between the "Occupation" sub-dimension based on the age of the participants, while no significant difference was observed between gender, grade level, and the level of daily social media use. In this context, social media addiction in young individuals varies according to the sociodemographic characteristics of the individual. As a result, social media addiction can be reduced by determining the demographic characteristics of young individuals.

International Review of Management and Marketing

MURAT AKIN AKIN

The aim of this study is to determine whether or not internet addiction levels of young people lead to differences in social media use intentions. The study consists of two main parts. In the literature review section where the conceptual framework is tried to be formed, internet addiction and social media concepts are defined, and information on social media use is given. Following the conceptual framework, the hypothesis to test whether or not the addiction has led to differences in the intended use is analyzed with a sample of 756 participants. The results of the research study suggest that 96.8% of the young people use the Internet on a daily basis, 91.2% use mobile phones for the Internet access, 0.61 of the young people are addicted to it, and 0.391 of them spend 5 - 6 hours online every day. Facebook is seen as the most preferred social media tool. Young people use the social media mostly to establish communication and to make various kinds of sharing. It is worried that the ...

Remarking An Analisation

Dr. D I V Y A TYAGI

The purpose of the present investigation was to find out the social media addiction among College students. Social media addiction is one of the most burning problems among young adults, especially among college students. The sample of the present research work consisted of 140 college students from which we randomly selected only (35 boys, 35 girls). For this purpose social media addiction scale students form (smas-sf) developed by Cengiz Sahin was used. The sample of the investigation was randomly selected from Meerut College, Meerut. t-test was used for finding out a significant difference between concerning groups. Other descriptive techniques were also used, which showed that college boys have more social media addiction as compared to their female counterparts. Based on our findings we can also highlight the high, average, and low percentage of social media addiction among college students.1.42% high, 98.5% moderate, 0% low media addiction. Thus, we can explain our findings according to the changeable environment. The paper also suggested some intervention strategies to control the addiction to social media. In this respect, the paper has applied application in emerging adults.

AJIT-e: Online Academic Journal of Information Technology

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Abdulkadir Karacı

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

juweria shaikh

International Journal of Educational Methodology

Ozlem Afacan

The aim of this study was to investigate the social media addiction of high school students in terms of some variables such as age, class, type of school, gender and daily average internet usage period. Survey method was used in the study. "Social Media Addiction Scale" (SMAS) developed by Tutgun-Unal and "Personal Information Form" prepared by the researcher were used as data collection tools. The data were obtained from a total of 596 students studying in three high schools with different academic achievement level in Kirsehir in Turkey. No significant difference was found in terms of gender variable. When the total scores of high school students on Social Media Addiction Scale are examined, it is determined that the students have "low level of addiction". In addition, it was found that there was a significant relationship between high school students' daily average internet usage time and social media addiction.

Duygu Dumanlı Kürkçü

The primary aim of this study is to have information about the frequency of use of the Internet and social media among university students and to determine the relationships between the Internet addiction and social media addiction. Additionally, the other aim of this study is to determine to the relationships between varieties of the Internet and social media; such as sexuality, age and usage time. The sample group consists of 326 students in Istanbul, Turkey: 134 male students and 192 female students. The research data is obtained from a survey based on closed-ended questionnaire and a five-point Likert scale using the Internet addiction scale and social media addiction scale. Collected data has been entered to SPSS programme and this study involves a lot of statistical analysis of data based on cause and effect relation. The classification of the addiction levels are determined by using k-means clustering algorithm. According to the research results, all participants use the Internet and 99.1% of all participants use social media. The more time spending on the Internet by participants, they are getting more addicted to the Internet. This situation is also the same for social media. The 20.2 percent of the sample group can be defined as the Internet addicted, while the 21.2 percent of the sample group can be defined as social media addicted.

International Journal of Social Sciences and Education Research

mehmet ali Gazi

Journal of Education Technology in Health Sciences

Innovative Publication

Abstract Utilizing the technology made our life very easier and brought the globe in our hand which has got both pros and cons. Young generation is more of techno oriented than the values that makes them to be depending on the social medias easily that affects the domains of health. A study was conducted to assess the Social media addiction among the paramedical students. Quantitative research approach with non experimental, descriptive research design was used. Non probability convenient sampling technique was used to select 140 para medical students who fulfills the inclusion criteria. Self administered structured questionnaire was used. Modified social media addiction likert scale was used with 20 items. Findings of the study shows that vast majority (103(74%)) of the students were addicted to the social media. To conclude, it is the high time for the policy-makers to restrict on this and make provision to improve the interaction skills. Keywords: Social media addiction, Social interactions.

RELATED PAPERS

Tahsin Chow

IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology

Dante Chavarría Barrientos

Berkeley J. Middle E. & Islamic L.

Haider Hamoudi

karina guerrero

2018 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE)

Aletta Nylen

Edson de Faria Francisco

Eric Chabert

American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

Asrat Mekuria

Revista Geográfica Acadêmica

Miguel Vassallo

Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology

Fulya Çakalağaoğlu

NAKANO Toshiya

ida ayu trisnawati

Revista da Faculdade de Odontologia - UPF

Luiz Carlos Gonçalves

Felix Joachimski

Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers

Barbara Tabachnick

ETUDE: Journal of Educational Research

Amalia Febriyani

Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing

Taras Maksymyuk

Análisis Real Instituto Elcano

Carlos Malamud

2012 IEEE Fourth International Conference on Technology for Education

Andrew Chiarella

Michael Berridge

Materials Science and Engineering A-structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing

Anders Jarfors

World Journal of Emergency Surgery

Zsolt Balogh

call girls in goa

Call girls In Goa 9319373153 Call girls real metting

Atmospheric Pollution Research

Susumu Tohno

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery

anurag singh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Local news, paywall-free.

MinnPost’s timely reporting is available for free, all year round. But our work isn’t free to produce. Help sustain our nonprofit newsroom with a monthly donation today.

Nonprofit, independent journalism. Supported by readers.

Studies highlight impact of social media use on college student mental health

Share this:.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

MinnPost’s Daily Newsletter

The latest on the politics and policy shaping Minnesota.

Delivered straight to your inbox.

Stay in the know.

MinnPost’s top stories delivered straight to your inbox Monday through Saturday.

When Kyle Palmberg set out to design a research study as the capstone project for his psychology major at St. Mary’s University of M i nnesota in Winona, he knew he wanted his focus to be topical and relevant to college students.

His initial brainstorming centered around the mental health impact of poor sleep quality.