Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

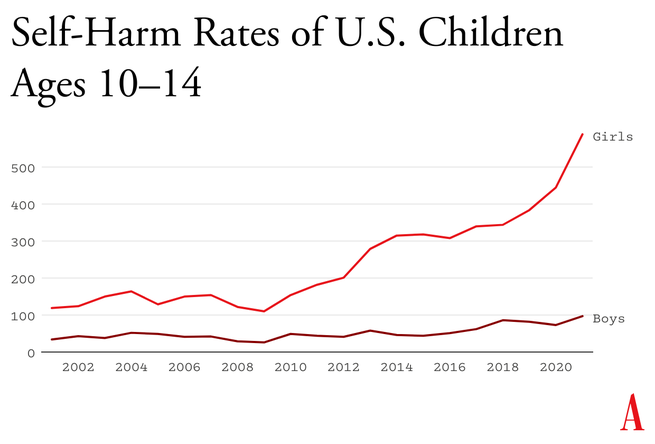

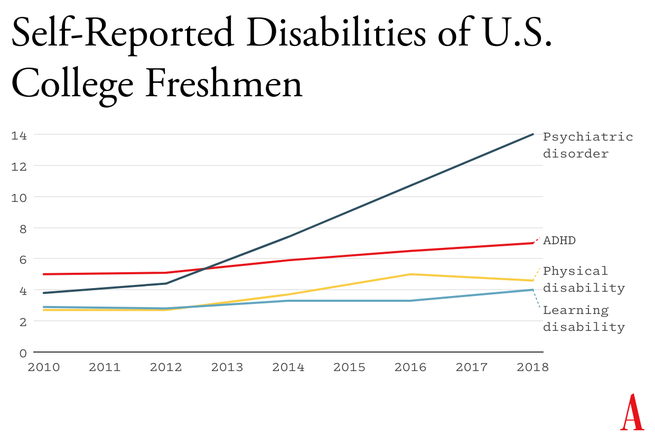

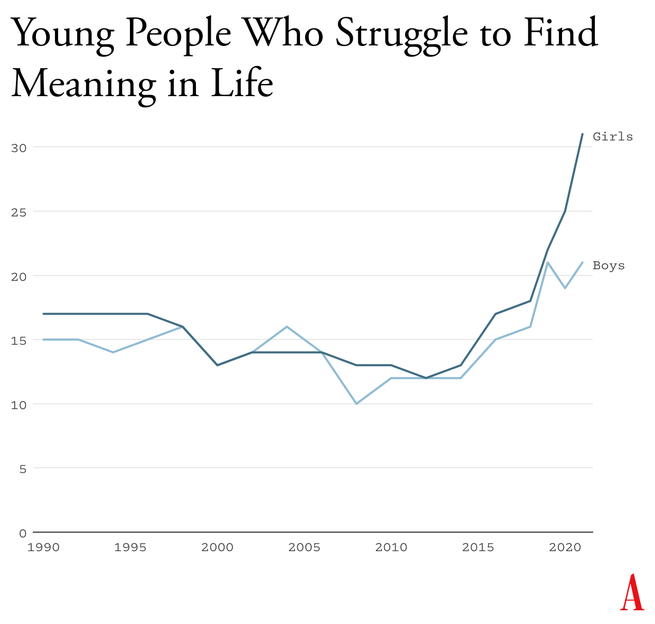

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Timbre can affect what harmony is music to our ears

Not all cultures value happiness over other aspects of well-being

‘Space: The Longest Goodbye’ explores astronauts’ mental health

‘Countdown’ takes stock of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile

Why large language models aren’t headed toward humanlike understanding

Physicist Sekazi Mtingwa considers himself an apostle of science

A new book explores the transformative power of bird-watching

U.S. opioid deaths are out of control. Can safe injection sites help?

From the nature index.

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

- Open access

- Published: 06 July 2023

Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health

- Ágnes Zsila 1 , 2 &

- Marc Eric S. Reyes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5280-1315 3

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 201 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

356k Accesses

13 Citations

89 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of social media significantly impacts mental health. It can enhance connection, increase self-esteem, and improve a sense of belonging. But it can also lead to tremendous stress, pressure to compare oneself to others, and increased sadness and isolation. Mindful use is essential to social media consumption.

Social media has become integral to our daily routines: we interact with family members and friends, accept invitations to public events, and join online communities to meet people who share similar preferences using these platforms. Social media has opened a new avenue for social experiences since the early 2000s, extending the possibilities for communication. According to recent research [ 1 ], people spend 2.3 h daily on social media. YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat have become increasingly popular among youth in 2022, and one-third think they spend too much time on these platforms [ 2 ]. The considerable time people spend on social media worldwide has directed researchers’ attention toward the potential benefits and risks. Research shows excessive use is mainly associated with lower psychological well-being [ 3 ]. However, findings also suggest that the quality rather than the quantity of social media use can determine whether the experience will enhance or deteriorate the user’s mental health [ 4 ]. In this collection, we will explore the impact of social media use on mental health by providing comprehensive research perspectives on positive and negative effects.

Social media can provide opportunities to enhance the mental health of users by facilitating social connections and peer support [ 5 ]. Indeed, online communities can provide a space for discussions regarding health conditions, adverse life events, or everyday challenges, which may decrease the sense of stigmatization and increase belongingness and perceived emotional support. Mutual friendships, rewarding social interactions, and humor on social media also reduced stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 4 ].

On the other hand, several studies have pointed out the potentially detrimental effects of social media use on mental health. Concerns have been raised that social media may lead to body image dissatisfaction [ 6 ], increase the risk of addiction and cyberbullying involvement [ 5 ], contribute to phubbing behaviors [ 7 ], and negatively affects mood [ 8 ]. Excessive use has increased loneliness, fear of missing out, and decreased subjective well-being and life satisfaction [ 8 ]. Users at risk of social media addiction often report depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem [ 9 ].

Overall, findings regarding the impact of social media on mental health pointed out some essential resources for psychological well-being through rewarding online social interactions. However, there is a need to raise awareness about the possible risks associated with excessive use, which can negatively affect mental health and everyday functioning [ 9 ]. There is neither a negative nor positive consensus regarding the effects of social media on people. However, by teaching people social media literacy, we can maximize their chances of having balanced, safe, and meaningful experiences on these platforms [ 10 ].

We encourage researchers to submit their research articles and contribute to a more differentiated overview of the impact of social media on mental health. BMC Psychology welcomes submissions to its new collection, which promises to present the latest findings in the emerging field of social media research. We seek research papers using qualitative and quantitative methods, focusing on social media users’ positive and negative aspects. We believe this collection will provide a more comprehensive picture of social media’s positive and negative effects on users’ mental health.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Statista. (2022). Time spent on social media [Chart]. Accessed June 14, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/chart/18983/time-spent-on-social-media/ .

Pew Research Center. (2023). Teens and social media: Key findings from Pew Research Center surveys. Retrieved June 14, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/04/24/teens-and-social-media-key-findings-from-pew-research-center-surveys/ .

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S. L., Inchley, J. C.,Badura, P.,… Stevens, G. W. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health , 66(6), S89-S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.011.

Marciano L, Ostroumova M, Schulz PJ, Camerini AL. Digital media use and adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;9:2208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641831 .

Article Google Scholar

Naslund JA, Bondre A, Torous J, Aschbrenner KA. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J Technol Behav Sci. 2020;5:245–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00094-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harriger JA, Thompson JK, Tiggemann M. TikTok, TikTok, the time is now: future directions in social media and body image. Body Image. 2023;44:222–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.005 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chi LC, Tang TC, Tang E. The phubbing phenomenon: a cross-sectional study on the relationships among social media addiction, fear of missing out, personality traits, and phubbing behavior. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(2):1112–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-0135-4 .

Valkenburg PM. Social media use and well-being: what we know and what we need to know. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;45:101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.101294 .

Bányai F, Zsila Á, Király O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Farkas J, Rigó P Jr, Demetrovics Z. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 .

American Psychological Association. (2023). APA panel issues recommendations for adolescent social media use. Retrieved from https://apa-panel-issues-recommendations-for-adolescent-social-media-use-774560.html .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Ágnes Zsila was supported by the ÚNKP-22-4 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Budapest, Hungary

Ágnes Zsila

Institute of Psychology, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Department of Psychology, College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, 1008, Philippines

Marc Eric S. Reyes

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AZ conceived and drafted the Editorial. MESR wrote the abstract and revised the Editorial. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marc Eric S. Reyes .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zsila, Á., Reyes, M.E.S. Pros & cons: impacts of social media on mental health. BMC Psychol 11 , 201 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2023

Accepted : 03 July 2023

Published : 06 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01243-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social media

- Mental health

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

EDITORIAL article

Editorial: understanding the impact of social media on public mental health and crisis management during the covid-19 pandemic.

- 1 School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China

- 2 School of Public Administration, Hunan University, Changsha, China

- 3 Public Management and Policy Analysis Program, Graduate School of International Relations, International University of Japan, Minamiuonuma, Japan

Editorial on the Research Topic Understanding the impact of social media on public mental health and crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic

The advent of the digital age has led to changes in the manner and nature of information generation, circulation, and reception. For example, social media connects people through text, pictures, and videos to build a vast social network ( De Paor and Heravi, 2020 ) and significantly influence people's mindset and behaviors ( Liu et al., 2018 ). At the same time, the efficiency of instant information exchange makes social media essential for risk management and responses to hazards, emergencies, and crises ( Brengarth and Mujkic, 2016 ). During the time of crisis, information about the crisis could spread quickly beyond traditional media (e.g., newspapers and television) to social media platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp, WeChat, and Weibo, at an even more alarming speed ( Martínez-Rojas et al., 2018 ). However, convenient information sharing and fast spreading are usually accompanied by misinformation. The lack of online regulation and the anonymity of users also provide a breeding ground for misinformation, disinformation, social bots, fake news, and rumors. The prevalence of misinformation/disinformation has significantly undermined the full benefits of social media use and brought many challenges to cyberspace security and social order. This could create a hostile internet environment where toxic public opinions, fear, anger, and hate spread quickly ( Zhang et al., 2022 ), which would bring significant obstacles for governments in managing emergencies. Therefore, to understand the public responses and attitudinal dynamics and to promote more effective emergency management during emergencies, this Research Topic examines how social media use impacts people's mental health and government responses to crisis using several studies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has damaged the world economy badly and taken millions of lives in the past 3 years. Studies in this Research Topic are committed to providing fresh evidence and theoretical insights for understanding human mental health and promoting effective crisis management.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, social media has become the essential communication method for isolated people at home, given the concern that the virus could be transmitted quickly in meetings and social gatherings. Information related to COVID-19, medicines, vaccines, and government response measures became the central topic in cyberspace. For example, governments disseminated policy suggestions for people to stay safe and promoted implementing some stringent measures using social media platforms. Besides, social media has been the main channel for isolated individual to seek social support, which is essential for mental and physical health ( Straughan and Xu, 2023 ). The public relied on social media to keep in touch with their friends and relatives, learn how to protect themselves, share views and attitudes, and support one another. The diffusion of all kinds of information (scientific and lay knowledge) on social media highly influences recipients' attitudes, emotions and health practices ( Straughan and Xu, 2022 ). Different knowledge, attitudes, and practices were shared and discussed online, which provides an effective channel for researchers and policymakers to understand the status quo of public mental health and public opinions ( Liu et al., 2020 ). At the same time, during the pandemic, how to use the private data collected and stored on social media for the public's good is a critical issue. Researchers suggest that the big data collected on social media is helpful in allocating resources and providing support to fight against the pandemic and save lives ( Cai et al., 2022 ). Studies of the present Research Topic draw together empirical studies that explore how social media use affects public mental health and emergency management in crisis. Papers on this Research Topic contribute to understanding people's responses, coping with negative emotions, and network conflicts. Beyond the knowledge contribution, researchers also discussed policy implications.

There are five articles in this Research Topic. The topics covered in the present Research Topic include network distribution, social media, sentiment analysis, and public crisis management. More specifically, the papers investigated public reactions and emotional dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic, people's mental health under lockdown conditions, and the impact of social media on social support and public trust. Moreover, the present Research Topic also focused on comparing the impact of social media and traditional media on users' knowledge, attitudes, and health practices and the impact of social media on vaccine acceptance. The five articles examined the main theme of this Research Topic from different perspectives and evidence. We briefly introduce the articles in the next section. The articles are discussed according to the order in which they were published.

Article 1 ( Ma et al. ) collected users' interaction data from the Weibo platform. It examined the multidimensional attributes and characteristics of public sentiment during the outbreak of COVID-19 to meet the increasing demand for public opinion management on social media. The authors combined deep learning, topic clustering, and correlation analysis, and based on large-scale posts and comments, quantitatively analyzed the evolution law of public opinion in time series during the epidemic period and explored the content-based characteristics and audience response characteristics. Specifically, through the analysis of public opinion in the time series, the authors found that the trend of negative public opinion was divided internally, and there were specific window periods. The analysis of the content characteristics of public opinion showed that negative public opinion was more likely to cause public discussion with a larger scale and deep participation. Their analysis of the characteristics of audience response during the period of public opinion demonstrated that the generation of public opinion was independent of posts and users, and the guiding role of opinion leaders was limited. Finding in this paper provides insights for elevating the capacity of public opinion management, effective intervention, and improving the public opinion management system.

Article 2 ( Sun et al. ) focused on the mental health of individuals during the global pandemic. It analyzed how the stressors related to COVID-19 and the use of social media promoted the psychological adjustment of individuals' coping strategies based on the transactional model of stress and coping. The authors collected survey data from 641 quarantined residents during the COVID-19 pandemic to analyze the relationships between perceived COVID-19 stress, social media use, and personal coping strategies. Research results revealed the critical role of social media use in coping with stress and psychological adjustment, which could help readers to understand how social media use affected the mental health of individuals under public health crises as well as the impact of different ways of social media use on individual psychological adjustment.

Article 3 ( Steinberger and Kim ) investigated unhealthy user behaviors represented by social network addiction and looked into the relationship between subjective wellbeing and social network addiction through a cross-sectional survey. In this article, the authors examined two possible mediating factors between subjective wellbeing and social network addiction: social comparison and the fear of missing out. Social comparison was divided into two aspects: social comparison of ability and social comparison of opinion. The former related to the social outcomes described in social network posts (such as material wealth, health status, and personal achievements), and the latter referred to the beliefs and values expressed in the posts. Results showed that social comparison and the fear of missing out jointly mediated the relationship between subjective wellbeing and social network addiction, and social comparison of ability played a more important role in social network addiction than social comparison of opinion. In addition, the fear of missing out in social networks also relies more on the process of ability than opinion comparisons. The findings of this study offered support for understanding social network addiction and promoting the formation of healthy behavior habits for social media users.

Article 4 ( Mensah et al. ) focused on government information transparency and information adoption by analyzing how perceived government information transparency affected the adoption of information related to COVID-19 on social media based on the information adoption model. In this article, the authors examined the survey data collected from 516 participants. It was found that information quality, credibility, and usefulness effectively affected the adoption of COVID-19 pandemic information on social media. Meanwhile, the perceived government information transparency positively moderated the impact of information quality, credibility, and usefulness on adopting COVID-19 pandemic information on social media. This study shed light on combating the wave of false information, improving social media's ability to respond to public health events, and establishing a sound public health emergency response system.

Article 5 ( Alon-Tirosh and Meir ) used a qualitative approach and examined how a group of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and difficulties in communication used social network sites to communicate. In this article, based on semi-structured interviews with ten adolescents diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, the authors analyzed the reasons for using social networks, the specific situations of social network use, and the characteristics of autism reflected through social networking. The results provided insightful evidence about how social networks could play a role in the lives of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, confirming that social media's social interaction function is even more essential for adolescents with autism.

Author contributions

MC: Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. PL: Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. CX: Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. HL: Writing—original draft.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by grants from the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22BSH109), the Shaanxi Province Innovation Capacity Support Program (Grant No. 2023-CX-RKX-005), the Chunhui Program of Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (Grant No. 202200829), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. SK2022005), the Xi'an Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 23RKYJ0037), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 531118010405), and the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (Grant No. 2021JJ40131).

Acknowledgments

We thank all authors' contributions to this Research Topic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Brengarth, L. B., and Mujkic, E. (2016). WEB 2.0: How social media applications leverage nonprofit responses during a wildfire crisis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 54, 589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.010

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cai, M., Luo, H., Meng, X., Cui, Y., and Wang, W. (2022). Influence of information attributes on information dissemination in public health emergencies. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 1–22. doi: 10.1057/s41599-022-01278-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

De Paor, S., and Heravi, B. (2020). Information literacy and fake news: How the field of librarianship can help combat the epidemic of fake news. J. Acad. Librar. 46, 102218. doi: 10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102218

Liu, D., Zhang, H., Yu, H., Zhao, X., Wang, W., Liu, X., et al. (2020). “Research on network public opinion analysis and monitor method based on big data technology,” in 2020 IEEE 10th International Conference on Electronics Information and Emergency Communication (ICEIEC) , 195–199. doi: 10.1109/ICEIEC49280.2020.9152232

Liu, P., Chan, D., Qiu, L., Tov, W., and Tong, V. J. C. (2018). Effects of cultural tightness–looseness and social network density on expression of positive and negative emotions: A large-scale study of impression management by Facebook users. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 1567–1581. doi: 10.1177/0146167218770999

Martínez-Rojas, M., Pardo-Ferreira, M., del, C., and Rubio-Romero, J. C. (2018). Twitter as a tool for the management and analysis of emergency situations: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 43, 196–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.07.008

Straughan, P. T., and Xu, C. (2022). Parents' knowledge, attitudes, and practices of childhood obesity in Singapore. SAGE Open 12, 21582440221144436. doi: 10.1177/21582440221144436

Straughan, P. T., and Xu, C. (2023). How does parents' social support impact children's health practice? Examining a mediating role of health knowledge. Global Health Res. Policy 8, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s41256-023-00291-5

Zhang, Y., Guo, B., Ding, Y., Liu, J., Qiu, C., Liu, S., et al. (2022). Investigation of the determinants for misinformation correction effectiveness on social media during COVID-19 pandemic. Inf. Proc. Manage. 59, 102935. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2022.102935

Keywords: network dissemination, social media, sentiment analysis, public crisis management, public mental health

Citation: Cai M, Liu P, Xu C and Luo H (2023) Editorial: Understanding the impact of social media on public mental health and crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 14:1304586. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1304586

Received: 29 September 2023; Accepted: 04 October 2023; Published: 16 October 2023.

Edited and reviewed by: Rosanna E. Guadagno , University of Oulu, Finland

Copyright © 2023 Cai, Liu, Xu and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meng Cai, mengcai@mail.xjtu.edu.cn ; Pan Liu, liupan@hnu.edu.cn ; Chengwei Xu, xuchengwei1985@gmail.com

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Social Media and Mental Health Connection

Sherri Gordon, CLC is a published author, certified professional life coach, and bullying prevention expert. She's also the former editor of Columbus Parent and has countless years of experience writing and researching health and social issues.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sherri-Gordon-1000-9b857b46047148108c1f2fb50bee6e51.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

Verywell / Catherine Song

Why Social Media Is Growing in Popularity

Social media and mental health concerns, signs social media is impacting your mental health.

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in social media use. According to the Pew Research Center, 72% of Americans in the U.S. use social media.

People use social networking tools to stay in touch with family and friends, get their news, and share their political views . This has some researchers wondering about the long-term effects of social media use.

Because social media use is still relatively new, there are no long-term studies documenting its effects. But several studies indicate that social media impacts mental health in a number of ways. The increasing reliance on and use of social media puts a large number of Americans at an increased risk for feeling anxious, depressed, lonely, envious, and even ill over social media use.

Aside from the fact that social media allows people to reconnect with family and friends that live far away or that they have lost touch with, it became a vital communication tool during the pandemic.

Social Media Supports Connections

People used social media to share information and connect with others when stay-at-home orders kept them from meeting in person. It became a vehicle for social support and connectedness that they would not otherwise have had.

Social Media Makes People Feel Good

Social media has a tendency to reinforce use. People quickly become hooked on checking their statuses for comments and likes, as well as perusing other people's posts.

Using social media sometimes activates the brain's reward center by releasing dopamine , also known as the feel-good chemical. This dopamine release, in turn, keeps people coming back because they want to repeat those feel-good experiences.

Social Media Boosts Self-Esteem

Social media also can boost self-esteem , especially if a person is viewed favorably online or gets a number of likes or interactions on their content. And social media allows some people to share parts of their identity that may be challenging to communicate in person.

Social media can be particularly helpful for people with social anxiety who struggle to interact with people in person.

Despite the above benefits, researchers are discovering that there are some downsides to social media, particularly with regard to mental health.

Social Media Use May Contribute to Depression

For a technology that's supposed to bring people closer together, it can have the opposite effect—especially when disagreements erupt online. Social media has been linked to depression , anxiety, and loneliness. It can make people feel isolated and alone.

One 2017 study found that young people who use social media more than two hours per day are much more likely to categorize their mental health as fair or poor compared to occasional social media users.

A large-scale study of young adults in the U.S. found that occasional users of social media are three times less likely to experience symptoms of depression than heavy users.

Social Media May Hurt Your Self-Esteem

While social media can sometimes be a self-esteem booster, it can also cause you to experience feelings of inadequacy about your life and your appearance. Even if you know that the images you see online are manipulated or represent someone else's highlight reel, they can still cause feelings of insecurity, envy, and dissatisfaction.

Fear of Missing Out

Another mental health phenomenon associated with social media is what is known as FOMO , or the "fear of missing out." Social media sites like Facebook and Instagram exacerbate the fear that you're missing something or that other people are living a better life than you are.

In extreme cases, FOMO can cause you to become tethered to your phone where you are constantly checking for updates or responding to every single alert.

Social Media Can Lead to Self-Absorption

Sharing endless selfies as well as your innermost thoughts on social media can create an unhealthy self-centeredness that causes you to focus on crafting your online image rather than making memories with your friends and family members in real life.

In fact, strenuous efforts to engage in impression management or get external validation can have psychological costs, especially if the approval you're seeking is never received. Ultimately, the lack of positive feedback online can lead to self-doubt and self-hatred .

Impulse Control Issues

Excessive social media use can lead to impulse control issues , especially if you access your social networks using a smartphone. This means that you have round-the-clock access to your accounts, which not only makes it easy for you always to be connected, but can affect your concentration and focus. It can even disturb your sleep and compromise your in-person relationships.

Social Media May Be Used As an Unhealthy Coping Mechanism

Social media can become an unhealthy way of coping with uncomfortable feelings or emotions . For instance, if you turn to social media when you're feeling down, lonely, or bored, you're potentially using it as a way to distract you from unpleasant feelings.

Ultimately, social media is a poor way to self-soothe, especially because perusing social media can often make you feel worse instead of better.

Press Play For Advice on Reducing Screen Time

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares effective ways to reduce screen time. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

Because everyone is different, there is no set amount of time spent on social media that is recommended. Instead, you need to evaluate how your social media use is impacting your life, including how you feel when you don't use social media as well as how you feel after using it.

A 2018 University of Pennsylvania study suggests that self-monitoring can change one's perception of social media. According to the lead researcher, psychologist Melissa G. Hunt, PhD, using social media less than you normally do, can lead to significant decreases in loneliness and depression. By using self-monitoring and making adjustments, people can significantly improve their overall well-being.

Social Media Distracts You

If you find that your social media use is impacting your relationships or is distracting you from work or school, it may be problematic. Additionally, if scrolling through social media leaves you feeling envious, depressed, anxious, or angry, then you need to re-evaluate your use.

It could be that you need to detox from social media and spend some time offline in order to safeguard your mental health.

You Use Social Media to Avoid Negative Emotions

Social media also could be an issue if you tend to use it to fight boredom or to deal with loneliness. Although these feelings are uncomfortable and it's only natural to want to alleviate them, turning to social media for comfort or as a distraction is not a healthy way to cope with difficult feelings and emotions.

As a result, it may be time for you to reassess your social media habits. Here are some additional signs that social media may be having a negative impact on your life and your mental health:

- Your symptoms of anxiety, depression, and loneliness are increasing.

- You are spending more time on social media than with your real-world friends and family members.

- You tend to compare yourself unfavorably with others on social media or you find that are your frequently jealous of others.

- You are being trolled or cyberbullied by others online.

- You are engaging in risky behaviors or taking outrageous photos in order to gain likes.

- Your work obligations, family life, or school work is suffering because of the time you spend on social media.

- You have little time for self-care activities like mindfulness , self-reflection, exercise, and sleep.

If you're spending a significant amount of time on social media and you're beginning to notice feelings of sadness, dissatisfaction, frustration, and loneliness that are impacting your life and your relationships, it may be time to re-evaluate your online habits.

If you find that even after adjusting your social media use, you're still experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety, it's important to talk with your healthcare provider so that you can be evaluated. With proper treatment, you will soon be feeling better.

If you or a loved one are struggling with [condition name], contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Pew Research Center. Social media fact sheet .

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Social media use and mental health among students in Ontario . CAMH Population Studies eBulletin . 2018;19(2).

Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, et al. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults . Depress Anxiety . 2016;33(4):323-31. doi:10.1002/da.22466.

Chou H-TG, Edge N. “They are happier and having better lives than i am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives . Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw . 2012;15(2):117-121. doi:10.1089/cyber.2011.0324

Hunt MG, Marx R, Lipson C, Young J. No more FOMO: limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression . J Soc Clin Psychol . 2018;37(10):751-768. doi:10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

Karim F, Oyewande AA, Abdalla LF, Chaudhry Ehsanullah R, Khan S. Social media use and its connection to mental health: a systematic review . Cureus . 2020;12(6):e8627. doi:10.7759/cureus.8627

Pantic I. Online social networking and mental health . Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw . 2014;17(10):652-657. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0070

By Sherri Gordon Sherri Gordon, CLC is a published author, certified professional life coach, and bullying prevention expert. She's also the former editor of Columbus Parent and has countless years of experience writing and researching health and social issues.

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Asthma & Allergies

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Breast Cancer

- Cardiovascular Health

- Environment & Sustainability

- Exercise & Fitness

- Headache & Migraine

- Health Equity

- HIV & AIDS

- Human Biology

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Parkinson's Disease

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Sexual Health

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Women's Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Vitamins & Supplements

- At-Home Testing

- Men’s Health

- Women’s Health

- Latest News

- Medical Myths

- Honest Nutrition

- Through My Eyes

- New Normal Health

- 2023 in medicine

- Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

- What do we know about the gut microbiome in IBD?

- My podcast changed me

- Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

- Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut

- Health Hubs

- Find a Doctor

- BMI Calculators and Charts

- Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide

- Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide

- Sleep Calculator

- RA Myths vs Facts

- Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar

- Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction

- Our Editorial Process

- Content Integrity

- Conscious Language

- Health Conditions

- Health Products

What to know about social media and mental health

Social media use can lead to low quality sleep and harm mental health. It has associations with depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem.

Many people in today’s world live with their smartphones as virtual companions. These devices use electronic social media networks that alert users to updates on friends, favorite celebrities, and global events. Social media has become firmly integrated into a lot of people’s daily lives. According to the Pew Research Center, 72% of people in the United States now use social media.

At its core, social media is a powerful communication tool that has changed how individuals interact with one another. It speeds up how people exchange and share information, thoughts, and ideas across virtual networks. However, social media does have downsides. Some evidence suggests that its use — in particular, its overuse — can negatively affect mental health in numerous ways.

Keep reading to learn more about the links between social media and mental health, including the positive and negative effects that this tool can have on individuals.

Why social media affects mental health

Social media has associations with depression , anxiety, and feelings of isolation, particularly among heavy users.

A 2015 Common Sense survey found that teenagers may spend as much as 9 hours of each day online. Many of these individuals are themselves concerned that they spend too much time browsing social networks. This wave of concern suggests that social media could affect the mental health of its users.

The researchers behind a 2017 Canadian study confirmed this finding. They noted that students who use social media for more than 2 hours daily are considerably more likely to rate their mental health as fair or poor than occasional users.

A 2019 study tied social media use to disrupted and delayed sleep. Regular, high quality sleep is essential for well-being, and evidence shows that sleeping problems contribute to adverse mental health effects, such as depression and memory loss.

Aside from the adverse effects on sleep, social media may trigger mental health struggles by exposing individuals to cyberbullying. In a 2020 survey of more than 6,000 individuals aged 10–18 years, researchers found that about half of them had experienced cyberbullying.

One of the downsides of social media platforms is that they give individuals the opportunity to start or spread harmful rumors and use abusive words that can leave people with lasting emotional scars.

Social media has come under a lot of criticism, with many reports connecting its use with severe consequences.

National surveys and population-based studies show that the world of social media can have devastating effects on users’ mental health. In the U.S. alone, survey findings show a 25% increase in suicide attempts among teenagers between 2009 and 2017.

Although social media may not play a role in each of these incidences, the time frame correlates with the growing use of these platforms. A 2021 study confirms this effect. The researchers reported that while social media use had a minimal impact on boys’ risk of suicide , girls who used social media for at least 2 hours each day from the age of 13 years had a higher clinical risk of suicide as adults.

Furthermore, findings from a population-based study show a decline in mental health in the U.S., with a 37% increase in the likelihood of major depressive episodes among adolescents.

A 2019 study suggested that teenagers who use social media for more than 3 hours daily are more likely to experience mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, aggression, and antisocial behavior.

Suicide prevention

If you know someone at immediate risk of self-harm, suicide, or hurting another person:

- Ask the tough question: “Are you considering suicide?”

- Listen to the person without judgment.

- Call 911 or the local emergency number, or text TALK to 741741 to communicate with a trained crisis counselor.

- Stay with the person until professional help arrives.

- Try to remove any weapons, medications, or other potentially harmful objects.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, a prevention hotline can help. The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is available 24 hours a day at 988. During a crisis, people who are hard of hearing can use their preferred relay service or dial 711 then 988.

Find more links and local resources.

Negative effects on health

Social media may trigger feelings of inadequacy. People may feel as though their life or appearance does not compare favorably with that of others on social media, leading to feelings of envy and dissatisfaction.

A 2018 study found that high social media usage increases rather than decreases feelings of loneliness. It also reported that reducing social media use helps people feel less lonely and isolated and improves their well-being.

Additionally, social media can facilitate cyberbullying and create unhealthy self-centeredness and distance from friends and family.

Positive effects

Despite its drawbacks, social media remains an efficient means of connecting communities and individuals across the world.

Social media-based networking among small groups of people is beneficial for many. Through social media, youngsters who struggle with social skills and anxiety can express themselves and socialize. It can be particularly advantageous for marginalized groups, such as LGBTQIA+ communities, as it enables people to meet and interact with other like-minded individuals.

Social media also serves as a platform that gives a voice to the voiceless. For example, people who have been subject to violence and abuse can use communities such as the #MeToo community to air their views, talk about what they are facing, and find support.

Social media can also educate and inform and provide an outlet for creativity and self-expression.

Linked conditions

Unregulated social media leads to a constant fear of missing out, which many refer to as FOMO. People may feel as though others are having more fun than them, which can affect self-esteem and cause mental health issues.

Individuals may compulsively check their phones at the cost of missing sleep or choose social media over in-person relationships or meetups.

Additionally, prioritizing social media networking over physical and social interactions increases the chances of mood disorders such as anxiety and depression.

Managing the effects

An individual can make their use of social media positive by:

- turning off a smartphone’s data connectivity at certain times of the day, such as while driving, at work, or in meetings

- turning off data connectivity while spending time with friends and family

- leaving the smartphone out of reach while sleeping

- turning off notifications to make it easier to resist the distracting beeps or vibrations

- limiting social media use to a computer rather than a smartphone

Preventing negative effects

People can help themselves avoid some of the adverse effects of social media by limiting use to 30 minutes a day , in turn reducing FOMO and the associated negative consequences.

By being more conscious of the amount of time they spend on social media, a person may notice improvements in their general mood, focus, and overall mental health.

Social media provides users with a rapid means of electronic communication and content sharing.

Although it has various positive effects, it can negatively affect users’ mental health.

Limiting the use of social media to 30 minutes a day can reduce FOMO and, in turn, relieve the loneliness, anxiety, depression, and sleep problems associated with excessive social media use.

Last medically reviewed on September 15, 2021

- Anxiety / Stress

- Psychology / Psychiatry

How we reviewed this article:

- Coyne, S. M., et al. (2021). Suicide risk in emerging adulthood: Associations with screen time over 10 years. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10964-020-01389-6

- Hunt, M. G., et al. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression [Abstract]. https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

- Jiang, J. (2018). How teens and parents navigate screen time and device distractions. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/08/22/how-teens-and-parents-navigate-screen-time-and-device-distractions/

- Lobe, B., et al. (2020). How children (10–18) experienced online risks during the COVID-19 lockdown — Spring 2020. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC124034

- Mojtabai, R., et al. (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/6/e20161878.short

- Pane, N. E. (2018). The rate of high school-aged youth considering and committing suicide continues to rise, particularly among female students. https://www.childtrends.org/high-school-aged-youth-considering-and-committing-suicide-among-female-students

- Riehm, K. E., et al. (2019). Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2749480

- Scott, H., et al. (2019). Social media use and adolescent sleep patterns: Cross-sectional findings from the UK millennium cohort study. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6830469/

- Sleep disorders. (n.d.). https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Common-with-Mental-Illness/Sleep-Disorders

- Social media fact sheet. (2021). https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

- Social media use and mental health among students in Ontario. (2018). https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs---ebulletin/ebulletin-19-n2-socialmedia-mentalhealth-2017osduhs-pdf.pdf

- The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. (2015). https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/census_researchreport.pdf

Share this article

Latest news

Related coverage.

Social communication disorder causes difficulties with social communication, language, and understanding social norms. Learn more.

What do we really know about the links between social media use and mental health? We spoke with seven experts to find out.

Social anxiety disorder refers to excessive emotional discomfort, anxiety, fear, or worry about social situations. Learn more here.

A person with depression may experience persistent feelings of sadness or emptiness. Different therapies may help a person to manage their depression.

Fear of rejection is an irrational and persistent fear of social exclusion. Learn more about the signs, causes, and how to overcome it here.

Social media use can be positive for mental health and well-being

January 6, 2020— Mesfin Awoke Bekalu , research scientist in the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, discusses a new study he co-authored on associations between social media use and mental health and well-being.

What is healthy vs. potentially problematic social media use?

Our study has brought preliminary evidence to answer this question. Using a nationally representative sample, we assessed the association of two dimensions of social media use—how much it’s routinely used and how emotionally connected users are to the platforms—with three health-related outcomes: social well-being, positive mental health, and self-rated health.

We found that routine social media use—for example, using social media as part of everyday routine and responding to content that others share—is positively associated with all three health outcomes. Emotional connection to social media—for example, checking apps excessively out of fear of missing out, being disappointed about or feeling disconnected from friends when not logged into social media—is negatively associated with all three outcomes.

In more general terms, these findings suggest that as long as we are mindful users, routine use may not in itself be a problem. Indeed, it could be beneficial.

For those with unhealthy social media use, behavioral interventions may help. For example, programs that develop “effortful control” skills—the ability to self-regulate behavior—have been widely shown to be useful in dealing with problematic Internet and social media use.

We’re used to hearing that social media use is harmful to mental health and well-being, particularly for young people. Did it surprise you to find that it can have positive effects?

The findings go against what some might expect, which is intriguing. We know that having a strong social network is associated with positive mental health and well-being. Routine social media use may compensate for diminishing face-to-face social interactions in people’s busy lives. Social media may provide individuals with a platform that overcomes barriers of distance and time, allowing them to connect and reconnect with others and thereby expand and strengthen their in-person networks and interactions. Indeed, there is some empirical evidence supporting this.

On the other hand, a growing body of research has demonstrated that social media use is negatively associated with mental health and well-being, particularly among young people—for example, it may contribute to increased risk of depression and anxiety symptoms.

Our findings suggest that the ways that people are using social media may have more of an impact on their mental health and well-being than just the frequency and duration of their use.

What disparities did you find in the ways that social media use benefits and harms certain populations? What concerns does this raise?

My co-authors Rachel McCloud , Vish Viswanath , and I found that the benefits and harms associated with social media use varied across demographic, socioeconomic, and racial population sub-groups. Specifically, while the benefits were generally associated with younger age, better education, and being white, the harms were associated with older age, less education, and being a racial minority. Indeed, these findings are consistent with the body of work on communication inequalities and health disparities that our lab, the Viswanath lab , has documented over the past 15 or so years. We know that education, income, race, and ethnicity influence people’s access to, and ability to act on, health information from media, including the Internet. The concern is that social media may perpetuate those differences.

— Amy Roeder

Social Media and Mental Health Essay

The role of social media in people’s lives has increased exponentially over the past decade. The online personas that people create matter to them nearly just as much as their real-life image due to the constant communication and the opportunity to track down their responses to specific posts at any time. As a result, the impact of social media on the mental well-being of its users is worth considering. Sumner et al. point to the positive effects of social media, clarifying that the specified technological innovation can be used as the tool for improving mental health of its users. Namely, the research states that social media allows spreading useful and positive information about health-related issues much faster than traditional media. As a result, the opportunities for increasing the levels of public health and addressing some of the most common public health issues emerge.

The connection between the positivity of a message and its reception in social media is a crucial piece of information that needs to be incorporated into the current approach toward increasing the levels of public health, citizens’ health literacy, and the accessibility of health services. Namely, the conclusions that Sumner et al. make concerning the direct correlation between the positivity of a message and the likelihood of it being transmitted to a greater number of people should be used as the tool fro encouraging better health management: “Sheer volume of supportive content provided by produced by organizations or individuals may be less important than creating higher-quality messages” (p. 143). Thus, the conclusion that the authors provide should be used to enhance the efficacy and accessibility of the current health services.

One could argue that the general research outcomes should be seen as quite upsetting given the implications that they provide. Namely, the fact that the work of health professionals, who perform meticulous studies and arrange the data as carefully as possible to provide accurate and concise guidelines may be less important than an upbeat yet empty message is a rather sad idea. The specified conclusions may lead to a drop in the extent of health practitioners’ and nurse educators’ enthusiasm in providing the services of the highest quality.

However, the message that Sumner et al. convey could also be seen as an opportunity for enhancing health education and raising health literacy within the community by building a better rapport with its members. Namely, the data about the significance of the use of positivity in social networks as the tool for attracting the attention of patients and target audiences should be utilized to shape the current approach toward promoting health literacy. Specifically, healthcare practitioners and registered nurses, especially those that address the issues of patient education directly, need to create the strategy for the online conversation with patients through social media. The specified dialogue could be based on a combination of positive messages and clear visuals that inform patients about key issues in health management and provide them with an opportunity to improve their health literacy.

Additionally, the authors have provided an important tool for the development of a campaign aimed at public health management and improvement. Namely, based on the outcomes of the research carried out by Sumner et al. have informed the strategies for improving communication between patients and nurse educators. The specified change in how people perceive health management is especially important in the context of the present-day epidemic of coronavirus. Given the rapid spread of the epidemic and its recent transformation into the pandemic, reinforcing the instructions for people to remain safe is an essential task for APRNs and healthcare experts worldwide. In turn, the application of social media suits perfectly for the described purpose since it allows sharing information instantly and providing people with clear and concise guidelines for them to follow. Although social media mostly do not allow for detailed descriptions of specific health concerns and profound analysis of these issues, they serve their purpose of bulletin boards with clear and distinct guidelines that the members of the global community can apply to their daily routine.

Specifically, the use of positive messages in social media will reinforce the importance of guidelines and ensuring that people will follow them properly. For instance, Sumner et al. mention that the use of social networks has helped to promote social sharing. As the authors explain, “In topic areas such as cancer support, investigators found that the degree of positive sentiment in a message is associated with increased message spread” (Summer et al, p. 143). Therefore, the inclusion of positive thinking and positive emotions into the process of knowledge sharing enhances the extent to which people are willing to engage in the discussion. Moreover, the rise in the inclination to share a message that is positive will allow fighting some of the most severe health concerns that the global community is facing presently, primarily, the coronavirus.

Furthermore, the discussion sparked by the authors raises the question of inaccurate health-related information in social media and the means of filtering data. Indeed, for an uninitiated user of social media, discerning between accurate health-related information and the posts that reinforce health-associated myths is virtually impossible. Although some indicators such as the identity of the user posting the information could provide hints regarding the veracity of data, social media users have to rely on their intuition for the most part. Therefore, it is also critical for nurses to develop strategies for shielding social media users from the data that provides a distorted picture of health management.

Finally, the issue of addressing serious health concerns in social media should be discussed as a contentious subject. Given the outcomes of the research performed by Summer et al., it is critical to focus on delivering positive messages to target audiences to increase compliance with the established health management strategies. However, when tackling a serious health concern that has led or may potentially lead to a rapid rise in lethal outcomes, remaining positive becomes quite challenging. Not only will a message sound false in the specified circumstances, but it is also likely to be perceived in a negative light due to the dissonance between the subject matter and the tone of its delivery. Therefore, the outcomes of the study pose a difficult dilemma for educators and healthcare providers to resolve when addressing their target audiences via social media. Namely, retaining positivity while talking about serious issues is likely to become a major stumbling block for most healthcare service members.

The outcomes of the study performed by Summer et al. have offered a range of important insights, the significance of positivity in modern media as the means of encouraging citizens to accept healthy behaviors being one of the key conclusions. However, to apply the specified results to the management of current public health concerns, one will have to shape the existing framework for communicating with patients significantly. Therefore, the research should be seen as the basis for redesigning the present health education strategy, as well as the approach toward conversing with patients.

Sumner, Steven A., et al. “Factors Associated with Increased Dissemination of Positive Mental Health Messaging on Social Media.” Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention , vol. 41, no. 2, 2019, pp. 141-145. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000598.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, February 17). Social Media and Mental Health. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-media-and-mental-health/

"Social Media and Mental Health." IvyPanda , 17 Feb. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/social-media-and-mental-health/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Social Media and Mental Health'. 17 February.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Social Media and Mental Health." February 17, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-media-and-mental-health/.

1. IvyPanda . "Social Media and Mental Health." February 17, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-media-and-mental-health/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Social Media and Mental Health." February 17, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-media-and-mental-health/.

- Sumner, Wilson, Reagan, and Obama

- American History: Native Americans

- Triangle Shirtwaist Company Fire and Labor Reforms

- Body Positivity in Terms of Psychology

- Drilling Activities and Earthquakes in Kansas

- Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness

- The Way the Federal Government Treated Native Americans

- Social Darwinism Through the History

- The Importance of Positivity at Work and in Life

- How Do Social Media Influencers Convey the Message of Body Positivity?

- Technological Determinism Perspective Discussion

- Cyberbullying as a Major Problem in Contemporary Society

- Self-Disclosure and Social Media

- Social Media Satirical Cartoon by M. Wuerker

- “Westside Today” and “Gazette Newspapers”: Comparative Characteristics

Social Media

Can social media cause mental health conditions, what is the real relationship between using social media and poor mental health.

Posted March 28, 2024 | Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

- Understanding any link requires an understanding of what diagnosis of a mental health condition involves.

- Talk of causation can be misleading as to the nature of the needed exploration.

- It may be better to examine the relationships between the social media use behavior and behaviors that emerge.

Legitimate questions have been asked for a long period concerning whether social media use causes particular mental health conditions. Mental health conditions such as depression , anxiety , autism spectrum disorder, attention -deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder have been linked with overuse of social media. If the development of such conditions is demonstrated to be correlated with the usage of social media, then whether a causal relationship exists appears to be an important and sensible question. However, understanding any link between social media use and mental health conditions is far from straightforward and requires a subtle understanding of what the diagnosis of a mental health condition involves.

4 Possible Reasons

There are several plausible answers to the question of what underlies the correlations often seen in the literature. Firstly, it could be that social media use leads to the development of mental health conditions. This answer implies a causal relationship and suggests that something about social media use is damaging to mental health. Secondly, it could be that mental health conditions lead to social media use. This answer suggests that the presence of mental health conditions somehow makes a person use social media more often, perhaps as a coping mechanism or management strategy. Thirdly, it may be that some third variable leads to the development of mental health conditions and overuse of social media; for instance, an attachment problem may provoke mental health issues as well as using social media to gain attachment that cannot otherwise be found. Finally, it could be argued that social media use produces behaviours similar to those seen in mental health conditions but that are not really the same as a mental health condition. For example, heavy selfie-posting on social media may lead to behaviours similar to those seen with narcissism, but that are not really narcissism.

All these solutions to why a correlation exists between social media overuse and mental health problems are legitimate, in the sense that all have been posited and all fall within the realm of sensible scientific discourse. However, there is an issue that all such attempts to address this relationship must grapple with, which concerns the nature of a mental health problem. All the above solutions, although different in their particulars, share one thing in common—namely, they all assume that there is such a thing as a mental health condition that can be caused. They all assume some kind of relatively straightforward "billiard ball" model of cause and effect—that is, one thing (e.g., social media use) impacts upon another (e.g., mental health) and sets the second thing in motion.

It may be that this sort of causal model does not capture the relationship between a particular behaviour (overuse of social media) and a set of subsequently co-occurring behaviours (the mental health condition). The first can be regarded as a single sort of thing—the use of a digital device—and this sort of thing could easily be fitted into a billiard-ball model of causation. However, the latter (the mental health condition) is not a thing in the sense that there is an "it," but rather, this is a concept, and it is far from clear that a concept is a type of thing that can be caused in a billiard ball sort of way.