Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 6: Progressivism

Dr. Della Perez

This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of Progressivism. This philosophy of education is rooted in the philosophy of pragmatism. Unlike Perennialism, which emphasizes a universal truth, progressivism favors “human experience as the basis for knowledge rather than authority” (Johnson et. al., 2011, p. 114). By focusing on human experience as the basis for knowledge, this philosophy of education shifts the focus of educational theory from school to student.

In order to understand the implications of this shift, an overview of the key characteristics of Progressivism will be provided in section one of this chapter. Information related to the curriculum, instructional methods, the role of the teacher, and the role of the learner will be presented in section two and three. Finally, key educators within progressivism and their contributions are presented in section four.

Characteristics of Progressivim

6.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following Essential Questions will be answered:

- In which school of thought is Perennialism rooted?

- What is the educational focus of Perennialism?

- What do Perrenialists believe are the primary goals of schooling?

Progressivism is a very student-centered philosophy of education. Rooted in pragmatism, the educational focus of progressivism is on engaging students in real-world problem- solving activities in a democratic and cooperative learning environment (Webb et. al., 2010). In order to solve these problems, students apply the scientific method. This ensures that they are actively engaged in the learning process as well as taking a practical approach to finding answers to real-world problems.

Progressivism was established in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential philosophies of education through the mid-1950s. One of the primary reasons for this is that a main tenet of progressivism is for the school to improve society. This was sup posed to be achieved by engaging students in tasks related to real-world problem-solving. As a result, progressivism was deemed to be a working model of democracy (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.2 A Closer Look

Please read the following article for more information on progressivism: Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find. As you read the article, think about the following Questions to Consider:

- How does the author define progressive education?

- What does the author say progressive education is not?

- What elements of progressivism make sense, according to the author?

Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find

6.3 Essential Questions

- How is a progressivist curriculum best described?

- What subjects are included in a progressivist curriculum?

- Do you think the focus of this curriculum is beneficial for students? Why or why not?

As previously stated, progressivism focuses on real-world problem-solving activities. Consequently, the progressivist curriculum is focused on providing students with real-world experiences that are meaningful and relevant to them rather than rigid subject-matter content.

Dewey (1963), who is often referred to as the “father of progressive education,” believed that all aspects of study (i.e., arithmetic, history, geography, etc.) need to be linked to materials based on students every- day life-experiences.

However, Dewey (1938) cautioned that not all experiences are equal:

The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely or equally educative. Experience and education cannot be directly equated to each other. For some experiences are mis-educative. Any experience is mis-education that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth or further experience (p. 25).

An example of miseducation would be that of a bank robber. He or she many learn from the experience of robbing a bank, but this experience can not be equated with that of a student learning to apply a history concept to his or her real-world experiences.

Features of a Progressive Curriculum

There are several key features that distinguish a progressive curriculum. According to Lerner (1962), some of the key features of a progressive curriculum include:

- A focus on the student

- A focus on peers

- An emphasis on growth

- Action centered

- Process and change centered

- Equality centered

- Community centered

To successfully apply these features, a progressive curriculum would feature an open classroom environment. In this type of environment, students would “spend considerable time in direct contact with the community or cultural surroundings beyond the confines of the classroom or school” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 74). For example, if students in Kansas were studying Brown v. Board of Education in their history class, they might visit the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka. By visiting the National Historic Site, students are no longer just studying something from the past, they are learning about history in a way that is meaningful and relevant to them today, which is essential in a progressive curriculum.

- In what ways have you experienced elements of a progressivist curriculum as a student?

- How might you implement a progressivist curriculum as a future teacher?

- What challenges do you see in implementing a progressivist curriculum and how might you overcome them?

Instruction in the Classroom

6.4 Essential Questions

- What are the main methods of instruction in a progressivist classroom?

- What is the teachers role in the classroom?

- What is the students role in the classroom?

- What strategies do students use in a progressivist classrooms?

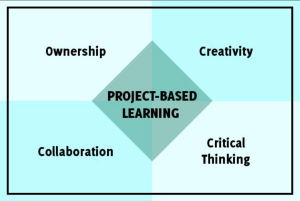

Within a progressivist classroom, key instructional methods include: group work and the project method. Group work promotes the experienced-centered focus of the progressive philosophy. By giving students opportunities to work together, they not only learn critical skills related to cooperation, they are also able to engage in and develop projects that are meaningful and have relevance to their everyday lives.

Promoting the use of project work, centered around the scientific method, also helps students engage in critical thinking, problem solving, and deci- sion making (Webb et. al., 2010). More importantly, the application of the scientific method allows progressivists to verify experi ence through investigation. Unlike Perennialists and essentialists, who view the scientific method as a means of verifying the truth (Webb et. al., 2010).

Teachers Role

Progressivists view teachers as a facilitator in the classroom. As the facilitator, the teacher directs the students learning, but the students voice is just as important as that of the teacher. For this reason, progressive education is often equated with student-centered instruction.

To support students in finding their own voice, the teacher takes on the role of a guide. Since the student has such an important role in the learning, the teacher needs to guide the students in “learning how to learn” (Labaree, 2005, p. 277). In other words, they need to help students construct the skills they need to understand and process the content.

In order to do this successfully, the teacher needs to act as a collaborative partner. As a collaborative partner, the teachers works with the student to make group decisions about what will be learned, keeping in mind the ultimate out- comes that need to be obtained. The primary aim as a collaborative partner, according to progressivists, is to help students “acquire the values of the democratic system” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 75).

Some of the key instructional methods used by progressivist teachers include:

- Promoting discovery and self-directly learning.

- Integrating socially relevant themes.

- Promoting values of community, cooperation, tolerance, justice, and democratic equality.

- Encouraging the use of group activities.

- Promoting the application of projects to enhance learning.

- Engaging students in critical thinking.

- Challenging students to work on their problem solving skills.

- Developing decision making techniques.

- Utilizing cooperative learning strategies. (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.5 An Example in Practice

Watch the following video and see how many of the bulleted instructional methods you can identify! In addition, while watching the video, think about the following questions:

- Do you think you have the skills to be a constructivist teacher? Why or why not?

- What qualities do you have that would make you good at applying a progressivist approach in the classroom? What would you need to improve upon?

Based on the instructional methods demonstrated in the video, it is clear to see that progressivist teachers, as facilitators of students learning, are encouraged to help their stu dents construct their own understanding by taking an active role in the learning process. Therefore, one of the most com- mon labels used to define this entire approach to education to- day is: constructivism .

Students Role

Students in a progressivist classroom are empowered to take a more active role in the learning process. In fact, they are encourage to actively construct their knowledge and understanding by:

- Interacting with their environment.

- Setting objectives for their own learning.

- Working together to solve problems.

- Learning by doing.

- Engaging in cooperative problem solving.

- Establishing classroom rules.

- Evaluating ideas.

- Testing ideas.

The examples provided above clearly demonstrate that in the progressive classroom, the students role is that of an active learner.

6.6 An Example in Practice

Mrs. Espenoza is an 6th grade teacher at Franklin Elementary. She has 24 students in her class. Half of her students are from diverse cultural- backgrounds and are receiving free and reduced lunch. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, Mrs. Espenoza does not use traditional textbooks in her classroom. Instead, she uses more real-world resources and technology that goes beyond the four walls of the classroom. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, she seeks out members of the community to be guest presenters in her classroom as she believes this provides her students with an way to interact with/learn about their community. Mrs. Espenoza also believes it is important for students to construct their own learning, so she emphasizes: cooperative problem solving, project-based learning, and critical thinking.

6.7 A Closer Look

For more information about progressivism, please watch the following videos. As you watch the videos, please use the “Questions to Consider” as a way to reflect on and monitor your own learnings.

• What additional insights did you gain about the progressivist philosophy?

• Can you relate elements of this philosophy to your own educational experiences? If so, how? If not, can you think of an example?

Key Educators

6.8 Essential Questions

- Who were the key educators of Progressivism?

- What impact did each of the key educators of Progressivism have on this philosophy of education?

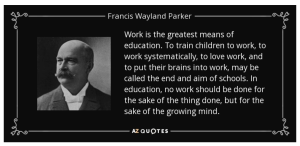

The father of progressive education is considered to be Francis W. Parker. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts, and later became the head of the Cook County Normal School in Chicago (Webb et. al., 2010). John Dewey is the American educator most commonly associated with progressivism. William H. Kilpatrick also played an important role in advancing progressivism. Each of these key educators, and their contributions, will be further explored in this section.

Francis W. Parker (1837 – 1902)

Francis W. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts (Webb, 2010). Between 1875 – 1879, Parker developed the Quincy plan and implemented an experimental program based on “meaningful learning and active understanding of concepts” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 1). When test results showed that students in Quincy schools outperformed the rest of the school children in Massachusetts, the progressive movement began.

Based on the popularity of his approach, Parker founded the Parker School in 1901. The Parker School

“promoted a more holistic and social approach, following Francis W. Parker’s beliefs that education should include the complete development of an individual (mental, physical, and moral) and that education could develop students into active, democratic citizens and lifelong learners” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 2).

Parker’s student-centered approach was a dramatic change from the prescribed curricula that focused on rote memorization and rigid student disciple. However, the success of the Parker School could not be disregarded. Alumni of the school were applying what they learned to improve their community and promote a more democratic society.

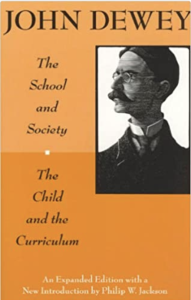

John Dewey (1859 – 1952)

John Dewey’s approach to progressivism is best articulated in his book: The School and Society

(1915). In this book, he argued that America needed new educational systems based on “the larger whole of social life” (Dewey, 1915, p. 66). In order to achieve this, Dewey proposed actively engaging students in inquiry-based learning and experimentation to promote active learning and growth among students.

As a result of his work, Dewey set the foundation for approaching teaching and learning from a student-driven perspective. Meaningful activities and projects that actively engaging the students’ interests and backgrounds as the “means” to learning were key (Tremmel, 2010, p. 126). In this way, the students could more fully develop as learning would be more meaningful to them.

6.9 A Closer Look

For more information about Dewey and his views on education, please read the following article titled: My Pedagogic Creed. This article is considered Dewey’s famous declaration concerning education as presented in five key articles that summarize his beliefs.

My Pedagogic Creed

William H. Kilpatrick (1871-1965)

Kilpatrick is best known for advancing progressive education as a result of his focus on experience-centered curriculum. Kilpatrick summarized his approach in a 1918 essay titled “The Project Method.” In this essay, Kilpatrick (1918) advocated for an educational approach that involves

“whole-hearted, purposeful activity proceeding in a social environment” (p. 320).

As identified within The Project Method, Kilpatrick (1918) emphasized the importance of looking at students’ interests as the basis for identifying curriculum and developing pedagogy. This student-centered approach was very significant at the time, as it moved away from the traditional approach of a more mandated curriculum and prescribed pedagogy.

Although many aspects of his student-centered approach were highly regarded, Kilpatrick was also criticized given the diminished importance of teachers in his approach in favor of the students interests and his “extreme ideas about student- centered action” (Tremmel, 2010, p. 131). Even Dewey felt that Kilpatrick did not place enough emphasis on the importance of the teacher and his or her collaborative role within the classroom.

Reflect on your learnings about Progressivism! Create a T-chart and bullet the pros and cons of Progressivism. Based on your T-chart, do you think you could successfully apply this philosophy in your future classroom? Why or why not?

Chapter 6: Progressivism Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Della Perez. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

29 Progressive Education

William J. Reese is the Carl F. Kaestle W.A.R.F. and Vilas Research Professor of educational policy studies and history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Published: 13 June 2019

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Progressive education emerged from a variety of reform movements, especially romanticism, in the early nineteenth century. Reflecting the idealism of contemporary political revolutions, it emphasized freedom for the child and curricular innovation. The Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi established popular model schools in the early 1800s that emphasized teaching young children through familiar objects, such as pebbles and shells, and not from textbooks. A German romantic, Friedrich Froebel, studied with Pestalozzi and invented the kindergarten, which spread worldwide. Progressive education mostly influenced pedagogy in the early elementary school grades. Over the course of the twentieth century, however, progressive ideals survived at other levels of schooling. Innovative teaching and curricular programs appeared in different times and places in model school systems, laboratory schools on college campuses, open classrooms, and alternative high schools. The greatest barriers to student-centered instruction included the widespread use of standardized testing and the prevalence of didactic teaching methods.

“ Progressive education ” remains a familiar phrase in the lexicon of educational historians but commonly eludes a precise definition or agreement about its origins, nature, or impact upon schools. By the first half of the nineteenth century, however, a variety of educators and writers in Europe and America claimed that a “new education” would inevitably replace outmoded instructional methods and curricula. Offering a new way of thinking about the nature of children and how to teach them, men and women on both sides of the Atlantic drew inspiration from a range of sources, promising a revolution in the history of childhood. By the early twentieth century, the phrase “new education” was gradually replaced by “progressive education.” Often reduced to slogans such as “learning by doing” or “experiential learning,” progressive education found expression in many schools worldwide through curriculum reforms and new teaching practices. It often found a home in teacher training programs. Yet the cluster of ideas embraced by many progressives usually failed to transform schools as they anticipated. By the early twenty-first century, standardized testing, didactic instructional methods, and classroom competition remained common in many nations.

In a speech at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1959, the historian Lawrence A. Cremin claimed that “the early progressives knew better what they were against than what they were for.” 1 He was referring to twentieth-century American educational reformers who more easily criticized conventional schools than agreed about how to implement “natural” pedagogical methods or to meet the needs of the “whole child.” Cremin’s insights can also be applied to many European and American activists in the early nineteenth century who complained about schools and called for a “new education.” They found existing pedagogical practices and the overall treatment of children in the larger society abhorrent, much like reformers today who still dream of greater well-being for all and more child-friendly schools where freedom for teacher and pupil takes precedence.

Throughout the Western world in the early 1800s, critics of schools and traditional childrearing practices could easily find grounds for optimism and despair. The American and French revolutions had toppled kings and promised greater equality and opportunity for more citizens. But child labor, abysmal poverty, slavery, the suppression of women’s rights, and other ancient evils endured despite growing movements for abolition, rising literacy rates and investment in schools, and an appreciation for women’s roles as mothers and teachers, part of the humanitarianism of the age. Advocates of the “new education” attacked time-honored school practices, including pupil memorization of textbooks, Bibles, and other reading materials, enforced when necessary by the rod. Influenced by political revolution, the Enlightenment, and romanticism, these reformers never formed a coherent movement, but they nevertheless shared fundamental beliefs, including a radical critique of conventional educational theories and practices. 2

Historical Roots and Nineteenth-Century Developments

In Europe and America, reformers were influenced by an array of thinkers who came before them. This ensured that advocates of the “new education” held eclectic views while calling for school improvements and greater attention to children’s welfare. While often deeply spiritual and Christian, they rejected the well-established religious claim that children were born in sin and thus evil by nature; traditionally, stubborn wills had to be broken, like horses, through physical restraint and harsh discipline. Some reformers drew upon the ideas of John Amos Comenius, a Moravian minister who wrote that young children especially learned best from familiar, age-appropriate materials, including visual sources. Even more influential, the English writer John Locke changed pedagogical theory forever by insisting that education above all—not inheritance—decisively shaped children’s development; this elevated human agency, highlighted the uniqueness of every individual, and encouraged additional speculation on effective childrearing.

More controversial but equally revolutionary were the various works of Jean Jacques Rousseau, whose political radicalism and religious views horrified the established leaders of church and state. Rousseau also fueled the growth of romanticism, which emphasized the innocence of children and the failures of adult institutions. Like Locke’s writings, Rousseau’s Emile (1762) was translated into many languages and challenged tradition; it became famous for its depiction of a pedagogically rich, imaginary world in which a male tutor raised a child through “natural” means. Advocating experiences over books, Rousseau urged adults to see the world through the eyes of a child, a revolutionary concept if taken literally, since schools had long been teacher- and textbook-, not child-centered. Rousseau’s insight—to treat children as children—seems commonsensical today but was revelatory at the time.

Criticisms of schools abounded in the nineteenth century, and the champions of the “new education” aimed to establish education and schooling on a more rational, humanitarian, child-sensitive foundation. Guidance came not only from luminaries such as Comenius, Locke, and Rousseau but also from the immediate romantic stirring of the period. In the late eighteenth century in England, the religious poet William Blake penned his Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), which contrasted the purity and innocence of youth with their destruction by the baleful influence of church and state, including schools. Blake wrote sympathetically about the plight of chimney sweeps and the urban poor and condemned the use of corporal punishment. Like many romantics, William Wordsworth lamented the soul-destroying effects of formal education. “Heaven lies about us in our infancy!” he claimed in 1804; soon enough the “Shades of the prison-house begin to close / Upon the Growing Boy.” In the United States, transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, a Unitarian minister, similarly linked childhood and innocence, and he applauded European educators and theorists who demanded more humane treatment of children, whether within families, at the workplace, or at school. The child, he wrote in Nature (1836), was a “perpetual Messiah,” calling adults back to an innocent state. 3

On both sides of the Atlantic, numerous citizens echoed the views of poets, philosophers, liberal clerics, and other advocates of the “new education.” Schools force-fed students arcane knowledge from textbooks; pupils memorized and recited lessons like parrots; teachers threatened pupils with physical punishment instead of making learning more appealing. While schools, according to many romantics, were often undesirable places, leading figures of the Enlightenment had also concluded that people could behave rationally and, contrary to orthodox Christian belief, promote progress. Individuals were not predestined to heaven or hell, and some reformers dreamed of establishing a heaven on earth. At the least they hoped to improve the lives of the most helpless individuals in society, including the young.

By the late eighteenth century, the publication of encyclopedias, dictionaries, and other means to advance learning beyond the elite classes seemed to portend an age of educational advance. “After bread, education is the first need of the people,” said the French revolutionary George Jacques Danton in 1792, and less revolutionary figures also spoke of a coming millennium of peace and prosperity. Thanks to technological innovations that reduced publishing costs by the 1820s, newspapers and magazines reached a wider readership; they often reported on the latest educational ideas. The desirability of education and school improvements thus drew sustenance from a variety of sources, including rising literacy rates in many Western nations.

It was one thing to condemn schools, another thing entirely to improve them. Some romantics, such as Blake, doubted that schools could ever play a positive role in society, but the nineteenth century became an age of institution building, including asylums, prisons, workhouses, and schools. Many of them did not advance the cause of humanity, and historians have long criticized their failings. But two European visionaries, Johann Pestalozzi and Friedrich Froebel, contributed to the hopefulness of the times and offered innovative ways to undermine hide-bound schools. Pestalozzi would forever be associated with “object teaching,” while Froebel became synonymous with his invention, the kindergarten. They became central to what contemporaries called the “new education,” a romantic, “natural” approach to teaching and learning. Reformers who called themselves progressives in the twentieth century stood upon their shoulders.

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was born in Switzerland and was initially swept up in the fervor of the French Revolution. His life transformed after reading Emile , he established model schools that taught many orphans, the victims of the continental wars. Pestalozzi became a sainted figure, his image sketched and painted, his writings widely quoted, his schools visited by many educational pilgrims. Children, he argued, learned naturally by handling familiar objects. Pebbles could be used to teach arithmetic, and the close study of nature revealed the mysteries of science, geography, and history. As Rousseau had written, educators should see the world through children’s eyes and introduce lessons to them in a natural way, drawing upon their immediate environment. Young children learned from things, not words, as Pestalozzi’s followers often said. Books, especially textbooks, represented adult-centered understandings of the world, far removed from children’s experiences. Children, so active outside of school, were expected to sit still in classrooms and often whipped when they failed to conform to the unrealistic expectations of teachers. Pestalozzi imagined a different approach. He idealized peasant mothers, deemed superior in teaching the young compared with schoolmasters wed to textbooks and corporal punishment. Children needed a harmonious education, one where adults in all settings treated them humanely, educating the hand, the heart, and the mind through pleasant means. 4

Pestalozzi came of age in an era without extensive systems of state-financed schools. Like many famous teachers, he apparently had a charismatic personality, attracting pupils and followers alike, while few teachers anywhere enjoyed such allure. Turning ideas conceived by a charismatic individual into everyday practices in systems of education raised a serious question: Was it possible? Pestalozzians quarreled over how to interpret his writings, which they often read in translation in newspapers and magazines or heard about in lectures. This produced obvious problems in describing a genuinely Pestalozzian school, though most utilized a method called “object teaching,” which was packaged in Europe and America in training manuals and textbooks with step-by-step lesson plans in the basic subjects. In the United States they were often written by urban school superintendents far removed from the rural worlds that had shaped the great master’s schools and teaching with things, not words.

Prominent educational leaders helped popularize Pestalozzian ideals beyond Europe. For example, Horace Mann, America’s leading reformer in the late 1830s and 1840s, praised them in his writings and lectures. He and like-minded educators drew attention to the Swiss master in editorials and articles in leading periodicals, including the Common School Journal , which Mann edited. Saying schools should adopt more “natural” pedagogical methods was nevertheless easier than changing time-tested practices. While object teaching certainly became part of teacher training in the United States, historians have discovered that many pupils at the newly established normal schools had to concentrate on mastering the common school subjects before they might learn about alternative pedagogical methods. And most teachers seemed to teach as they had been taught, which meant mastering textbooks, not exploring sylvan fields.

Facing growing numbers of pupils in New York, Boston, and other cities, mainstream educators tried to bring order out of chaos, so they implemented not a flexible but a more uniform curriculum, set by administrators and approved by the local school board. Cities also built larger, better age-graded schools after midcentury. They increasingly hired women as elementary teachers, whose salaries were lower than males’ and often had classrooms with fifty to sixty pupils. Paying attention to each individual was very difficult, if not impossible, and teachers often could not model instruction on the scripted lessons in instructional manuals. More schools purchased globes and blackboards, and teachers sometimes taught subject matter with the aid of “objects” such as watches, coins, and rock collections; many schools, which were often overcrowded, nevertheless lacked the resources to buy expensive teaching aids. Reports thus circulated in Europe and America that schools remained textbook-based and teacher-, not child-centered. Traditional practices were difficult to dislodge.

Occasionally a charismatic individual carried the banner of the “new education” forward and demonstrated its practical character. Probably the best example in the United States was Colonel Francis W. Parker. Parker was a popular lecturer, writer, and administrator, the living embodiment of the “new education.” Having himself traveled to Europe to study education, he criticized rote methods of instruction, corporal punishment, and competitive written tests, the last becoming more common in urban schools after the 1850s. Between 1875 and 1880, Parker, a Civil War veteran, became nationally renowned for his achievements as school superintendent in Quincy, Massachusetts. He helped create a model public school system, where teachers apparently eschewed excessive memorization and recitation. The Quincy school board appointed teachers who shared his views on child-centered pedagogy. Forward-thinking educators and aspiring teachers flocked to Quincy, seeking guidance. But Parker’s tenure was short. Called the “father of progressive education” by none other than John Dewey, a close friend, Parker later headed a well-known teacher training college in Chicago. 5

The great question from the time of Pestalozzi and Parker to the present was whether teachers would embrace “natural” and child-centered methods when they themselves had often succeeded in old-fashioned schools and found jobs in similar types of institutions. Of course, the “new education” should not be judged only by whether it changed schools wholesale in any particular community or nation; at times, some of what Pestalozzi’s followers and other innovators had in mind made a visible dent in the system.

Indeed many urban schools lacking charismatic leadership or full support for the “new education” adopted some aspects of object teaching after the 1860s. On the edges of the curriculum, for example, “learning by doing” found expression in a range of manual training classes in many towns and cities. Nature study also became popular, supplementing textbook-based science instruction. A remarkable collection of photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston at the turn of the twentieth century demonstrates that many white and black schools in Washington, D.C., offered classes in dancing, cooking, and manual training, sponsored field trips, and initiated laboratory courses to enliven instruction. But detailed studies of the curriculum in the post–Civil War era show that urban and rural schools nationwide mostly focused on the basic subjects of reading, writing, and arithmetic in the elementary grades, wherein most pupils were enrolled, and on core academic subjects taught in traditional ways to the smaller numbers of pupils enrolled in high school. Many books and magazine articles in the 1890s noted that, even when districts adopted object teaching or manual training, they occupied only a small part of the school day. Most classes resembled the past. Textbooks reigned supreme, and memorization, recitation, and increasingly written examinations were common. Visitors to manual training classes sometimes found teachers lecturing, testifying to the firm grip of tradition. 6

In 1900 the U.S. Commissioner of Education, William T. Harris, a staunch supporter of an academic curriculum who frequently disparaged the “new education,” said that teachers were basically conservative. Most had succeeded as students in traditional classrooms. Writing in the journal Education , Harris explained that children were typically “full of caprice and wayward impulses,” and teachers endeavored to socialize them to adult norms. Teaching, he concluded, “is the most conservative of all occupations, excepting always the ministry. For the teacher has to deal with the unformed, undeveloped human being, and educate it into the manners and customs of civilized life, and above all open it for the storehouse of the wisdom of the human race.” Such statements rattled every progressive. Harris recognized that textbooks might be boring, but he regarded them as tools of democracy; an informed citizenry, as the Founders of the nation believed, needed access to the same basic knowledge. Textbooks were even more important to the many pupils who had dull, uninspiring teachers.

Harris was no stranger to debates about what knowledge or teaching methods merited a place at school. A Connecticut Yankee, Harris had dropped out of Yale and moved west, rising up the ranks to become the much-heralded superintendent of the St. Louis public schools between 1868 and 1880. As advocates of the “new education” there as elsewhere urged schools to become more child-friendly, Harris, a Hegelian philosopher and admirer of German culture, rejected romantic claims about the value of object teaching. But he notably embraced a key innovation that had originated in Europe: kindergartens.

Kindergartens were first established in the United States in the 1850s and were often found in urban areas populated with German immigrants, who were well represented on the St. Louis school board. While Harris doubted that kindergarten methods would transform the elementary grades as many reformers desired, he built a model system that attracted visitors from around the nation. A local training school prepared hundreds of women teachers, who ultimately spread the kindergarten gospel to many communities. The “child’s garden,” Harris believed, would not usher in a paradise of learning, but it could help adjust children from the informality of the home to the stricter demands of elementary school.

Kindergartens, like manual training, engaged children in numerous activities. They provided living proof that the “new education” could enter school systems otherwise committed to teacher authority and student mastery of textbooks. Children in kindergartens sat in a circle, not in fixed rows, and in moveable chairs, not bolted-down seats. Kindergartens promoted cooperative learning, stressed the educational value of structured play, and provided a sequenced set of lessons employing objects (balls, string, and so forth) and not books as the central means of instruction. Photographs of kindergartens reveal their home-like, middle-class atmosphere, with pleasant pictures adorning the walls and plants and flowers brightening the room. Women dominated in kindergarten teaching and supervision and helped popularize the reform in articles, books, and speeches. Women’s reputation for gentle treatment of little children—especially compared with men’s treatment—made them central to this aspect of the “new education.” 7

Friedrich Froebel, the German inventor of the kindergarten, had apprenticed in one of Pestalozzi’s schools, and the “child’s garden” became one of the most popular, long-lasting innovations associated with the “new education.” Initially banned in Prussia because of its links to political radicalism, the kindergarten spread to all corners of the world, though the followers of Froebel, like those of Pestalozzi, often disagreed about specific aspects of his educational philosophy and “gifts and occupations,” his richly symbolic curricular exercises. Rival professional associations in many nations debated how to organize kindergartens. By the late nineteenth century, only a small percentage of America’s school systems had funded them, but kindergartens were also found in settlement houses, orphan asylums, and private schools. City systems faced the challenge of paying teachers and constructing new buildings for a burgeoning population. In many large cities such as New York and Chicago, thousands of children in the 1890s could not find a seat in public elementary schools, which remained overcrowded. Providing universal access to new programs in early childhood education was prohibitively expensive in many school districts and inconceivable in some. But kindergartens were here to stay, as the “new education” traveled from Europe to America and other nations.

Emphasizing activities over books led critics then and in later generations to call the movement anti-intellectual. Pestalozzi and Froebel would have found the charge puzzling, since they expressly desired a harmonious education that cultivated the head, heart, and hand. But some champions of object teaching believed it was a basis for vocational education, particularly for outcast groups such as Native Americans, African Americans, and poor whites. Native American boarding schools that formed after the Civil War as well as public schools for African Americans in different parts of the country tried to downplay academics in favor of trade training. Males at boarding schools and other institutions attended by these groups were often taught obsolete handcraft skills; women received instruction in housekeeping skills deemed suitable for future domestics. Most schools still taught academic subjects, and neither Pestalozzi nor Froebel imagined that hand-training sufficed in a well-rounded education. 8

By 1900, then, some key developments emerged related to the “new education,” which increasingly became known as “progressive education.” Theorists focused on young children, not older ones, since they were seen as more malleable. Children over the age of twelve or so were usually working or attended school sporadically in Western nations, so the focus on the very young seemed sensible. Charismatic individuals associated with the “new education” established model schools, which attracted legions of the curious, who struggled to re-create what they saw in established systems. The “new education” was also expensive, requiring teaching aids, shop and kitchen tools, and more and better trained teachers, straining school budgets. This ensured that even when reformers promoted vocational education programs, such innovations never replaced the basics, which usually continued to be taught in familiar ways.

Obstacles to adopting reform on a grand scale were many. Schools faced the wrath of taxpayers who attacked “fads and frills” during economic recessions and depressions, which happened frequently in the second half of the nineteenth century. And the notion that children—not teachers and textbooks—should occupy the center of the educational universe struck many parents, taxpayers, and teachers as utopian. Supporting an innovation, including the kindergarten, did not mean one had romantic views of children or hoped that its methods would permeate the entire system. Object teaching, kindergartens, and manual training were nevertheless clear signs that the “new education” left a discernable mark on many schools around the world.

Twentieth-Century Developments

John Dewey, America’s preeminent philosopher in the first half of the twentieth century, wrote critically about the romantics, including Rousseau, Pestalozzi, and Froebel, and in a series of articles and books consistently criticized the excesses of “child-centered” education. In the late 1890s and early decades of the new century, he frequently contrasted the “old education”—seats in a row, children reciting subject matter they did not understand, schools that emphasized order instead of the joy of learning—with a “new education” that tried to recognize children’s interests and needs and to reconstruct pedagogy and curricula accordingly. Dewey recognized, however, that otherwise intriguing proposals for reform could themselves become ossified or counterproductive, as when object teaching was reduced to formulaic prescriptions in guides to teaching and critics sneered at traditional education, which emphasized pupil mastery of academic subjects. Dewey reminded child-oriented educators that learning (as most teachers and parents believed) required considerable effort by students and that teachers erred in trying to sugarcoat the educational process. The historian Herbert M. Kliebard succinctly explains, “Dewey’s position in curriculum matters is sometimes crudely described as ‘child-centered,’ though he was actually trying to achieve a creative synthesis of the child’s spontaneous interests and tendencies on the one hand and the refined intellectual resources of the culture on the other.”

Examples of “new” or “progressive” educational practices surfaced in a variety of schools over the course of the twentieth century. Sometimes the new generation of reformers lacked much knowledge about the activists and visionaries who preceded them, which might have led to more prudence as they denounced existing schools and proclaimed the dawn of a new age. As Dewey and other observers discovered, progressive schools had diverse characteristics, though they generally stressed the importance of children’s interests and needs, more creative, pupil-friendly pedagogy, and learning activities that eschewed or downplayed textbooks, memorization, and competitive examinations. The aim was to make students active participants in their own education. Like their predecessors, early twentieth-century champions of progressivism labored to make learning inviting by tapping the curiosity of pupils, whose intellectual growth and personal development were reportedly crushed by the old-fashioned methods and curricula still found in most schools.

Over the course of the twentieth century, educational experimentation drew upon familiar sources: dissatisfaction with the status quo, a sense that the vast social changes of the day made educational change inevitable, and the assumption that progress and educational reform were inextricably linked. By the 1890s reformers often drew upon the new discipline of psychology, particularly research on child and adolescent development. As education and psychology became university-based disciplines, child study became fashionable. G. Stanley Hall, one of John Dewey’s teachers in graduate school at Johns Hopkins University, studied the “contents of children’s minds” in the 1880s through surveys, providing early inventories of knowledge. Obstetrics and the study of childhood diseases gained more attention from the medical community, and measuring pupil achievement through the latest quantitative methods became common by the early twentieth century. Research at universities expanded and some cities established their own research bureaus. Despite disagreements about what it meant to study children scientifically, researchers increasingly questioned whether schools should focus on academic subjects alone, to the exclusion of a student’s physical or psychological needs. 9

Educational experimentation flourished in the early decades of the twentieth century. Between 1896 and 1904, for example, Dewey and his wife, Alice, epitomized the trend, having established the world-renowned Laboratory School at the University of Chicago. The school had a selective student body, mostly the children of faculty members. They studied standard academic subjects but also clay modeling, raised and sheared sheep and spun wool, and constructed buildings, an echo of the “object teaching” popularized by Pestalozzi’s disciples. The lessons emphasized the connections between subject matter and everyday life, showing how occupations evolved over time. The aim was not vocational: teachers were not training future carpenters or shepherds. Teachers guided children and encouraged them to seek knowledge through their own initiative. For example, they could learn to boil an egg by consulting a cookbook, but it was far better if they experimented on their own, learning through trial and error. As Dewey explained in School and Society (1899) and other writings, textbooks were filled with abstractions, based on adult understanding of subject matter. Teachers should breathe life into the abstractions and tie them to everyday experience.

Other educational experiments were under way elsewhere. Like the Laboratory School, they became meccas for educators and interested citizens who lamented the still powerful grip of traditional theories and practices in most schools. People interested in reform read about or tried to visit Maria Montessori’s Casa dei Bambini in Italy; the platoon system of schools in many American cities, folk schools in Scandinavia, model progressive ones in the Soviet Union and elsewhere in the 1920s; private child-centered schools and public suburban systems such as in Winnetka, Illinois, that incorporated some of Dewey’s ideas, in the 1930s and 1940s; Dalton schools and Waldorf schools; infant schools established in England; and “open classrooms,” “schools without walls,” and alternative high schools in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

As in the nineteenth century, progressives learned about innovative practices by visiting schools at home and abroad, by reading extensively, and increasingly by attending college, often earning credentials in education or in the social sciences. Upon finishing their degrees, graduate students who became professors of education often helped establish laboratory schools at their home institutions, whether they had studied at the University of Iowa or at Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City. Some reformers such as Dewey traveled extensively, gaining insights into how educational ideas developed and expressed themselves in diverse cultural settings. Ideas traveled across national borders and were reshaped to fit into new contexts. American progressives, in turn, visited schools in Mexico and other nations to gain insights on the wide range of educational subjects, from the use and abuse of intelligence tests to how to improve teaching. 10

Generalizing about such a range of schools, why they were established, and their ultimate importance in different times and places is very difficult. As Dewey and his daughter Evelyn explained in Schools of Tomorrow (1915), many aspects of innovative schools varied. Some appeared in rural settings, others in cities. Some were more libertarian than others. School founders and teachers debated how much freedom to grant to pupils and what children should study and why. Activists usually stereotyped the existing institutions most children attended as backward, too rooted in the past and disconnected from the present. Progressive schools, in contrast, usually promised greater freedom for the child, enriched curricula, and disdain for anything conventional.

Women continued to play a crucial role as progressive teachers and as the founders of prominent experimental schools. In Fairhope, Alabama, in the early twentieth century, Marietta Johnson established the Organic School, which, as the historian Joseph W. Newman explains, attracted teachers who shared her views on child-centered instruction. Caroline Pratt’s City and Country School in New York City offered an alternative to the conventional teaching methods entrenched in the public system. Over the course of the twentieth century, some progressive schools (e.g., the Dalton School in New York City) had high academic standards and evolved into selective institutions for a college-bound elite; others, such as some alternative high schools in American cities in the 1960s and 1970s, taught pupils unsuited for conventional classrooms. Some progressive leaders and their staff and students wanted a refuge from society, others to radically transform it. In the romantic language of the 1960s, many idealists, sounding like the original romantics, dreamed of allowing a thousand (or more) flowers to bloom. That seemed impossible in regular schools then and even more so in the coming decades, when many national systems joined a frantic race to raise test scores and race to the top of league tables. 11

A few examples of what many contemporaries called “progressive education” in America’s urban public schools illuminate their diversity. One fascinating experiment emerged in Gary, Indiana. Established in 1906, the city was home to U.S. Steel, the largest steel plant in the world. The local school board comprised a small elite of businessmen and professionals who generally supported the innovative ideas of the local school superintendent, William A. Wirt, who served from 1907 until his death in 1938. As Ronald D. Cohen demonstrates in his exemplary history of the Gary schools, Wirt, who became acquainted with Dewey’s ideas while studying at the University of Chicago, drew upon diverse theories. Like many contemporary reformers, he believed that schools should meet the needs and interests of the child; they did not exist simply for the adults who paid for or worked in the system. Wirt and like-minded educational leaders elsewhere thus challenged the belief that schools should focus on academics alone; modern schools should address a widened horizon of concerns of childhood, adolescence, and the local community. “Schools did not just offer curricular and extracurricular choices to pupils,” Cohen writes, “but also provided medical care, baby sitting, social welfare services, recreation for the entire family, adult programs … facilities for the handicapped, and employment opportunities, and served as an anchor for the community.” This became central to the modern vision, Cohen concludes, of “progressive education.” 12

Superintendent Wirt devised the “work-play-study” approach to schooling, popularly known as the “platoon” system, and promoted student engagement, a hallmark of progressivism. Students spent part of the day in academic study of an enriched curriculum that included the arts and music, then moved to shop and manual training classes, with time reserved for sports and physical education. Visitors described the schools as active sites for learning; some had swimming pools, extensive playing fields, and evening classes for adults. According to Wirt, work, play, and study were ideally mutually reinforcing. As children and increasingly adolescents were removed from the full-time labor force, schools also provided more social services, including meals and medical and dental inspection. Above all, Wirt wanted children to stay busy, to find something they enjoyed and in which to excel. Left-wing radicals and conservatives alike praised the system, which promised the efficiency of industrial plants as well as a more cohesive and culturally enriched community.

Dozens of urban districts in America adopted a version of the platoon system, one of the most widely discussed and debated innovations of the early twentieth century. After the stock market crash of 1929, the economic depression that followed caused business leaders to reduce financial support for the platoon system, which unraveled after Wirt’s death. But progressive practices entered many public schools in the first half of the twentieth century, irrespective of the fate of Wirt’s system. Educators often embraced the language and some of the practices of the new, or progressive education. Since the romantic era of the nineteenth century, more educators claimed that children’s needs (always difficult to define) were paramount, that traditional curricula and pedagogical methods repelled many children, and that schools should better appeal to them. While the platoon system disappeared, a full range of social services, including the expansion of programs for special needs pupils, became common in Gary and other school districts after World War II. The academic mission of schools hardly disappeared, but schools performed many social and vocational functions, as advocates of the “new education” earlier anticipated.

While a number of elite private schools in the 1920s and 1930s became famous exemplars of child-centered education, Gary’s schools demonstrated that progressivism formulated in a unique way could thrive in a largely working-class city and in a public system. Another example of how progressive ideas flourished for a time in public schools arose in Winnetka, Illinois, a Chicago suburb. According to Cohen, many of Wirt’s associates regarded him as aloof. Not so with his contemporary Carleton Washburne, Winnetka’s superintendent between 1919 and 1943. Like many leaders associated with the “new education” in the nineteenth century, Washburne was charismatic. Like Wirt, he had an unusually long tenure and until nearly the end of his career enjoyed strong support from parents and the school board.