- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Prewriting Strategies

Five useful strategies.

Pre-writing strategies use writing to generate and clarify ideas. While many writers have traditionally created outlines before beginning writing, there are several other effective prewriting activities. We often call these prewriting strategies “brainstorming techniques.” Five useful strategies are listing, clustering, freewriting, looping, and asking the six journalists' questions. These strategies help you with both your invention and organization of ideas, and they can aid you in developing topics for your writing.

Listing is a process of producing a lot of information within a short time by generating some broad ideas and then building on those associations for more detail with a bullet point list. Listing is particularly useful if your starting topic is very broad, and you need to narrow it down.

- Jot down all the possible terms that emerge from the general topic you are working on. This procedure works especially well if you work in a team. All team members can generate ideas, with one member acting as scribe. Do not worry about editing or throwing out what might not be a good idea. Simply write down as many possibilities as you can.

- Group the items that you have listed according to arrangements that make sense to you. Are things thematically related?

- Give each group a label. Now you have a narrower topic with possible points of development.

- Write a sentence about the label you have given the group of ideas. Now you have a topic sentence or possibly a thesis statement .

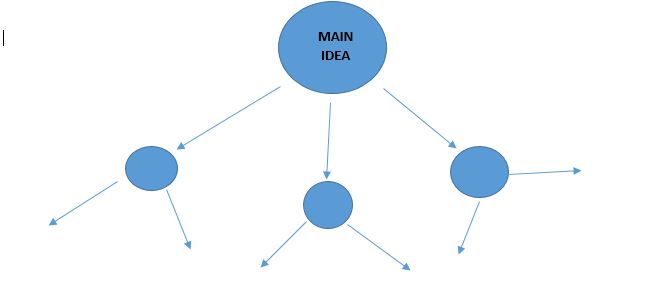

Clustering, also called mind mapping or idea mapping, is a strategy that allows you to explore the relationships between ideas.

- Put the subject in the center of a page. Circle or underline it.

- As you think of other ideas, write them on the page surrounding the central idea. Link the new ideas to the central circle with lines.

- As you think of ideas that relate to the new ideas, add to those in the same way.

The result will look like a web on your page. Locate clusters of interest to you, and use the terms you attached to the key ideas as departure points for your paper.

Clustering is especially useful in determining the relationship between ideas. You will be able to distinguish how the ideas fit together, especially where there is an abundance of ideas. Clustering your ideas lets you see them visually in a different way, so that you can more readily understand possible directions your paper may take.

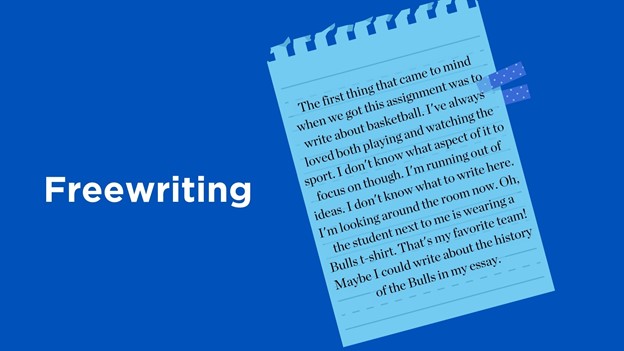

Freewriting

Freewriting is a process of generating a lot of information by writing non-stop in full sentences for a predetermined amount of time. It allows you to focus on a specific topic but forces you to write so quickly that you are unable to edit any of your ideas.

- Freewrite on the assignment or general topic for five to ten minutes non-stop. Force yourself to continue writing even if nothing specific comes to mind (so you could end up writing “I don’t know what to write about” over and over until an idea pops into your head. This is okay; the important thing is that you do not stop writing). This freewriting will include many ideas; at this point, generating ideas is what is important, not the grammar or the spelling.

- After you have finished freewriting, look back over what you have written and highlight the most prominent and interesting ideas; then you can begin all over again, with a tighter focus (see looping). You will narrow your topic and, in the process, you will generate several relevant points about the topic.

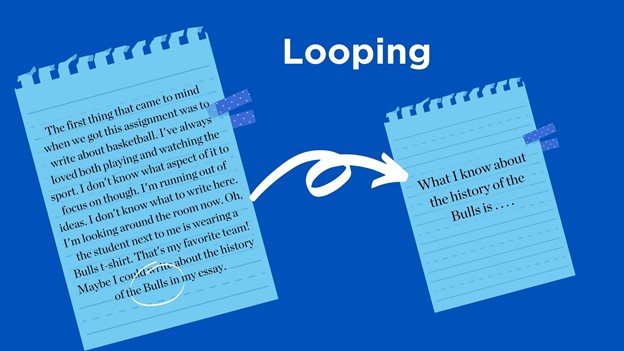

Looping is a freewriting technique that allows you to focus your ideas continually while trying to discover a writing topic. After you freewrite for the first time, identify a key thought or idea in your writing, and begin to freewrite again, with that idea as your starting point. You will loop one 5-10 minute freewriting after another, so you have a sequence of freewritings, each more specific than the last. The same rules that apply to freewriting apply to looping: write quickly, do not edit, and do not stop.

Loop your freewriting as many times as necessary, circling another interesting topic, idea, phrase, or sentence each time. When you have finished four or five rounds of looping, you will begin to have specific information that indicates what you are thinking about a particular topic. You may even have the basis for a tentative thesis or an improved idea for an approach to your assignment when you have finished.

The Journalists' Questions

Journalists traditionally ask six questions when they are writing assignments that are broken down into five W's and one H: Who? , What? , Where? , When? , Why? , and How? You can use these questions to explore the topic you are writing about for an assignment. A key to using the journalists' questions is to make them flexible enough to account for the specific details of your topic. For instance, if your topic is the rise and fall of the Puget Sound tides and its effect on salmon spawning, you may have very little to say about Who if your focus does not account for human involvement. On the other hand, some topics may be heavy on the Who , especially if human involvement is a crucial part of the topic.

The journalists' questions are a powerful way to develop a great deal of information about a topic very quickly. Learning to ask the appropriate questions about a topic takes practice, however. At times during writing an assignment, you may wish to go back and ask the journalists' questions again to clarify important points that may be getting lost in your planning and drafting.

Possible generic questions you can ask using the six journalists' questions follow:

- Who? Who are the participants? Who is affected? Who are the primary actors? Who are the secondary actors?

- What? What is the topic? What is the significance of the topic? What is the basic problem? What are the issues related to that problem?

- Where? Where does the activity take place? Where does the problem or issue have its source? At what place is the cause or effect of the problem most visible?

- When? When is the issue most apparent? (in the past? present? future?) When did the issue or problem develop? What historical forces helped shape the problem or issue and at what point in time will the problem or issue culminate in a crisis? When is action needed to address the issue or problem?

- Why? Why did the issue or problem arise? Why is it (your topic) an issue or problem at all? Why did the issue or problem develop in the way that it did?

- How? How is the issue or problem significant? How can it be addressed? How does it affect the participants? How can the issue or problem be resolved?

The Prewriting Stage of the Writing Process

- Tips & Strategies

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Teaching Resources

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

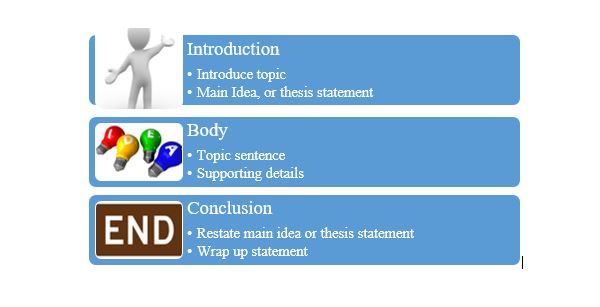

The writing process consists of different stages: prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. Prewriting is the most important of these steps. Prewriting is the "generating ideas" part of the writing process when the student works to determine the topic and the position or point-of-view for a target audience. Pre-writing should be offered with the time necessary for a student to create a plan or develop an outline to organize materials for the final product.

Why Prewrite?

The pre-writing stage could also be dubbed the "talking stage" of writing. Researchers have determined that talking plays an important role in literacy. Andrew Wilkinson (1965) coined the phrase oracy, defining it as "the ability to express oneself coherently and to communicate freely with others by word of mouth." Wilkinson explained how oracy leads to increased skill in reading and writing. In other words, talking about a topic will improve the writing. This connection between talk and writing is best expressed by the author James Britton (1970) who stated: "talk is the sea upon which all else floats.”

Prewriting Methods

There are a number of ways that students can tackle the prewriting stage of the writing process. Following are a few of the most common methods and strategies that students can use.

- Brainstorming - Brainstorming is the process of coming up with as many ideas as possible about a topic without being worried about the feasibility or whether an idea is realistic or not. A list format is often the easiest to organize. This can be done individually and then shared with the class or done as a group. Access to this list during the writing process can help students make connections they may want to use later in their writing.

- Freewriting - The free write strategy is when your students write whatever comes into their mind about the topic at hand for a specific amount of time, like 10 or 15 minutes. In a free write, students should not worry about grammar, punctuation, or spelling. Instead, they should try and come up with as many ideas as they possibly can to help them when they get to the writing process.

- Mind Maps - Concept maps or mind-mapping are great strategies to use during the pre-writing stage. Both are visual ways to outline information. There are many varieties of mind maps that can be quite useful as students work in the prewriting stage. Webbing is a great tool that has students write a word in the middle of a sheet of paper. Related words or phrases are then connected by lines to this original word in the center. They build on the idea so that, in the end, the student has a wealth of ideas that are connected to this central idea. For example, if the topic for a paper were the role of the US President , the student would write this in the center of the paper. Then as they thought of each role that the president fulfills, they could write this down in a circle connected by a line to this original idea. From these terms, the student could then add supporting details. In the end, they would have a nice roadmap for an essay on this topic.

- Drawing/Doodling - Some students respond well to the idea of being able to combine words with drawings as they think about what they want to write in the prewriting stage. This can open up creative lines of thought.

- Asking Questions - Students often come up with more creative ideas through the use of questioning. For example, if the student has to write about Heathcliff's role in Wuthering Heights , they might begin by asking themselves some questions about him and the causes of his hatred. They might ask how a 'normal' person might react to better understand the depths of Heathcliff's malevolence. The point is that these questions can help the student uncover a deeper understanding of the topic before they begin writing the essay.

- Outlining - Students can employ traditional outlines to help them organize their thoughts in a logical manner. The student would start with the overall topic and then list out their ideas with supporting details. It is helpful to point out to students that the more detailed their outline is from the beginning, the easier it will be for them write their paper.

Teachers should recognize that prewriting that begins in a "sea of talk" will engage students. Many students will find that combining a couple of these strategies may work well to provide them with a great basis for their final product. They may find that if they ask questions as they brainstorm, free write, mind-map, or doodle, they will organize their ideas for the topic. In short, the time put in up front in the pre-writing stage will make the writing stage much easier.

- Prewriting for Composition

- Create a Site Map Before You Build Your Site

- How to Explore Ideas Through Clustering

- The Whys and How-tos for Group Writing in All Content Areas

- The Use of Listing in Composition

- Focusing in Composition

- Explore and Evaluate Your Writing Process

- Discover Ideas Through Brainstorming

- Brainstorming Techniques for Students

- 60 Writing Topics for Extended Definitions

- How to Take Better Notes During Lectures, Discussions, and Interviews

- Discovery Strategy for Freewriting

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- Classification Paragraph, Essay, Speech, or Character Study: 50 Topics

- 6 Traits of Writing

- Writing Cause and Effect Essays for English Learners

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, prewriting – laying the foundation for successful writing.

Prewriting refers to all of the work you do before beginning to write. This article explores the dispositions and prewriting strategies writers employ to write more efficiently and with greater clarity and impact. Case studies, interviews, and observations of writers at work have found that prewriting involves balancing both intuitive, creative activities with critical, analytical strategies. For instance, during prewriting you are wise to listen your 'felt sense' - your embodied awareness of what you want to say. And, during prewriting, you are also wise to engage in more straightforward, cognitive processes such as engaging in outlining, drafting a document planner, or engaging in rhetorical analysis.

What is Prewriting?

Prewriting refers to

- a ll of the work a writer engages in BEFORE BEGINNING TO WRITE

- the first stage of the writing process

- a liminal space — the space between thinking about working on a project and actually beginning to write.

Writers have many ways of engaging in prewriting , based on their individual preferences and the discourse conventions of their audience . Interviews and case studies of writers @ work have found that during prewriting writers engage in a variety of dispositions and strategies :

Dispositions

- During prewriting, writers embrace intellectual openness . They interview stakeholders, consider counterarguments , and review the peer-reviewed literature on the topic

- During prewriting, writers adopt a growth mindset . They privilege the believing game over the doubting game .

- Some writers believe the subconscious is a source of ideas, creativity and inspiration. Some believe dreams are a window into the subconscious.

- “When writers are given a topic , the topic itself evokes a felt sense in them. This topic calls forth images, words, ideas, and vague fuzzy feelings that are anchored in the writer’s body. What is elicited, then, is not solely the product of a mind but of a mind alive in a living, sensing body…..When writers pause, when they go back and repeat key words, what they seem to be doing is waiting, paying attention to what is still vague and unclear. They are looking to their felt experience, and waiting for an image, a word, a phrase to emerge that captures the sense they embody….Usually, when they make the decision to write, it is after they have a dawning awareness that something has clicked, that they have enough of a sense that if they begin with a few words heading in a certain direction, words will continue to come which will allow them to flesh out the sense they have” (Perl 1980, p. 365).

- Writers like to talk over an exigency , a problem , a call to write with trusted friends, peers, and mentors. In college, students like to brainstorm with one another to better understand a writing assignment or the needs of the audience, such as a manager or a client, before deciding to take it on as a writing project

- In interviews and memoirs, writers and artists report insatiable inquiry. They engage in informal research . They engage in strategic research in order to learn what is known about the topic creative play.

- Writers may engage in meditation to help slow down. They may need to turn off their phones and computers to reach the state of calmness and focus necessary to begin thinking about a writing project.

- Writers like to procrastinate. Sometimes writers need to set a call to write aside. They need to let an idea simmer on the back burner. They may sleep on it.

- Some creative people track and interpret their dreams. They say this helps them interpret their dreams for insights, reoccurring narratives, and solutions to problems they face during waking hours.

- Writers may engage in extensive strategic searching in order to identify the status “ conversation ” on a particular topic . Writers may freewrite to see where their thoughts lead them.

The terms planning , prewriting , and invention are sometimes used interchangeably, yet they each carry distinct meanings:

- Prewriting is a subset of planning, focusing more on the initial stages of idea generation, brainstorming, and exploration of thoughts before formal writing begins

- Planning typically refers to the overall process of organizing ideas and structuring a writing piece, encompassing the selection of topics, determination of purpose, and arrangement of content

- Invention is often associated specifically with the creative aspect of prewriting , where writers devise innovative ideas, concepts, and arguments.

Related Concepts: Document Planner ; Intellectual Openness ; Mindset ; Resilience ; Rhetorical Analysis ; Self-Regulation & Metacognition

Why Does Prewriting Matter?

- Prewriting helps clarify and refine the central theme or argument of the piece.

- During prewriting, writers have the freedom to explore different angles and perspectives . This creative exploration can lead to more original and engaging content.

- By outlining the main ideas during prewriting, writers can determine what additional research or information is needed, making their research efforts more focused and efficient.

- Engaging in prewriting activities like brainstorming or free writing can help overcome writer’s block by getting ideas flowing and reducing the pressure of creating perfect content from the start .

- Prewriting helps in structuring thoughts and ideas, leading to a more organized and coherent draft. This organization is crucial for the logical flow of the final piece.

- During prewriting, writers can consider their audience’s needs and expectations , tailoring the content to be more relevant and engaging for the intended readers.

- Prewriting sets a solid foundation for the first draft, ensuring that the writing process starts with a clear direction and purpose.

- With a clear outline or plan from the prewriting stage, the actual writing process becomes more efficient, as the writer has a clear roadmap to follow.

- Prewriting gives writers a chance to reflect on their topic, assess their knowledge and opinions , and evaluate the potential impact of their writing.

Is Prewriting Always Necessary?

No. Writers differ in how frequently or deeply they engage in prewriting. Some people prefer to jump immediately into composing . They don’t pause to reflect on the rhetorical situation . They don’t want to conduct a literature review. Instead, they want to immediately dive in and spark the creative process by freewriting , visual brainstorming , and other creative heuristics .

In contrast, other writers prefer to engage significant prewriting: they question

- What’s known about a topic ? what’s novel? what knowledge claims are currently being disputed?

- What does peer-reviewed literature say about the topic?

- Do I need to engage in empirical research? What methods are expected by the discourse community?

- What informal, background research needs to be done in order to prepare to write?

- What’s the best way to organize the document? What common organizational patterns should I use to help the readers interpret the message?

What Is the Difference Between Planning, Prewriting & Invention?

The terms planning , prewriting , and invention may be used used interchangeably because they are such intertwined processes, yet they each carry distinct meanings:

- Planning typically refers to the overall process of organizing ideas and structuring a writing piece , encompassing the selection of topics , determination of purpose , and arrangement of content. It typically encompasses tools such as Team Charters and usage of project management software . While prewriting and invention may involve more creative and exploratory activities, planning is focused on setting a clear direction and framework for the writing.

- Prewriting is a subset of planning , focusing more on the initial stages of idea generation, brainstorming, and exploration of thoughts before formal writing begins. Prewriting is more expansive and free-form than planning, allowing for a broader exploration of thoughts and concepts. In comparison to invention, prewriting is less about generating new ideas and more about exploring and organizing existing ideas in preparation for writing.

- Invention in writing refers to the process of generating new ideas, concepts, or perspectives. Invention is distinct from planning and prewriting in that it is focused primarily on creating something new, rather than organizing or setting objectives for existing ideas.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

II. Getting Started

2.4 Prewriting

Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; and Terri Pantuso

Loosely defined, prewriting includes all the writing strategies employed before writing your first draft. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, the following section covers using experience and observations, reading, freewriting, asking questions, listing, and clustering/idea mapping. Using the strategies in the following section can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

Choosing a Topic

In addition to understanding that writing is a process , writers also understand that choosing a good general topic for an assignment is an essential first step. Sometimes your instructor will give you an idea to begin an assignment, and other times your instructor will ask you to come up with a topic on your own. A good topic not only covers what an assignment will be about, but it also fits the assignment’s purpose and its audience .

In the next few sections, you will follow a writer named Mariah as she explores and develops her essay’s topic and focus. You will also be planning one of your own. The first important step is for you to tell yourself why you are writing (to inform, to explain, or some other purpose) and for whom you are writing. Write your purpose and your audience on your own sheet of paper, and keep the paper close by as you read and write the first draft.

Experience and Observations

When selecting a topic, you may want to consider something that interests you or something based on your own life and personal experiences. Even everyday observations can lead to interesting topics. After writers think about their experiences and observations, they often take notes on paper to better develop their thoughts. These notes help writers discover what they have to say about their topic.

Reading plays a vital role in all the stages of the writing process, but it first figures in the development of ideas and topics. Different kinds of documents can help you choose and develop a topic. For example, a magazine cover advertising the latest research on the threat of global warming may catch your eye in the supermarket. This subject may interest you, and you may consider global warming as a topic. Or maybe a novel’s courtroom drama sparks your curiosity of a particular lawsuit or legal controversy.

After you choose a topic, critical reading is essential to the development of a topic. While reading almost any document, you evaluate the author’s point of view by thinking about his main idea and his support. When you judge the author’s argument, you discover more about not only the author’s opinion but also your own. If this step already seems daunting , remember that even the best writers need to use prewriting strategies to generate ideas.

Prewriting strategies depend on your critical reading skills. Reading, prewriting and brainstorming exercises (and outlines and drafts later in the writing process) will further develop your topic and ideas. As you continue to follow the writing process, you will see how Mariah uses critical reading skills to assess her own prewriting exercises.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming refers to writing techniques used to:

- Generate topic ideas

- Transfer your abstract thoughts on a topic into more concrete ideas on paper (or digitally on a computer screen)

- Organize the ideas you have generated to discover a focus and develop a working thesis

Although brainstorming techniques can be helpful in all stages of the writing process, you will have to find the techniques that are most effective for your writing needs. The following general strategies can be used when initially deciding on a topic, or for narrowing the focus for a topic: freewriting , a sking questions , listing , and clustering/idea mapping .

In the initial stage of the writing process, it is fine if you choose a general topic. Later you can use brainstorming strategies to narrow the focus of the topic.

Freewriting

Freewriting is an exercise in which you write freely about any topic for a set amount of time (usually five to seven minutes). During the time limit, you may jot down any thoughts that come to your mind. Try not to worry about grammar, spelling, or punctuation. Instead, write as quickly as you can without stopping. If you get stuck, just copy the same word or phrase over and over again until you come up with a new thought.

Writing often comes easier when you have a personal connection with the topic you have chosen. Remember, to generate ideas in your freewriting, you may also think about readings that you have enjoyed or that have challenged your thinking. Doing this may lead your thoughts in interesting directions.

Quickly recording your thoughts on paper will help you discover what you have to say about a topic. When writing quickly, try not to doubt or question your ideas. Allow yourself to write freely and unselfconsciously. Once you start writing with few limitations, you may find you have more to say than you first realized. Your flow of thoughts can lead you to discover even more ideas about the topic. Freewriting may even lead you to discover another topic that excites you even more.

Look at Mariah’s example below. The instructor allowed the members of the class to choose their own topics, and Mariah thought about her experiences as a communications major. She used this freewriting exercise to help her generate more concrete ideas from her own experience.

Freewriting Example

Last semester my favorite class was about mass media. We got to study radio and television. People say we watch too much television, and even though I try not to, I end up watching a few reality shows just to relax. Everyone has to relax! It’s too hard to relax when something like the news (my husband watches all the time) is on because it’s too scary now. Too much bad news, not enough good news. News. Newspapers I don’t read as much anymore. I can get the headlines on my homepage when I check my email. Email could be considered mass media too these days. I used to go to the video store a few times a week before I started school, but now the only way I know what movies are current is to listen for the Oscar nominations. We have cable but we can’t afford movie channels, so I sometimes look at older movies late at night. UGH. A few of them get played again and again until you’re sick of them. My husband thinks I’m crazy, but sometimes there are old black-and-whites on from the 1930s and ‘40s. I could never live my life in black-and-white. I like the home decorating shows and love how people use color on their walls. Makes rooms look so bright. When we buy a home, if we ever can, I’ll use lots of color. Some of those shows even show you how to do major renovations by yourself. Knock down walls and everything. Not for me–or my husband. I’m handier than he is. I wonder if they could make a reality show about us?

Asking Questions

Who? What? Where? When? Why? How?

In everyday situations, you pose these kinds of questions to get more information. Who will be my partner for the project? When is the next meeting? Why is my car making that odd noise? When faced with a writing assignment, you might ask yourself, “How do I begin?”

You seek the answers to these questions to gain knowledge, to better understand your daily experiences, and to plan for the future. Asking these types of questions will also help you with the writing process. As you choose your topic, answering these questions can help you revisit the ideas you already have and generate new ways to think about your topic. You may also discover aspects of the topic that are unfamiliar to you and that you would like to learn more about. All these idea-gathering techniques will help you plan for future work on your assignment.

When Mariah reread her freewriting notes, she found she had rambled and her thoughts were disjointed. She realized that the topic that interested her most was the one she started with, the media. She then decided to explore that topic by asking herself questions about it. Her purpose was to refine media into a topic she felt comfortable writing about. To see how asking questions can help you choose a topic, take a look at the following chart that Mariah completed to record her questions and answers. She asked herself the questions that reporters and journalists use to gather information for their stories. The questions are often called the 5WH questions, after their initial letters.

Asking Questions Example

Narrowing the Focus

After rereading her essay assignment, Mariah realized her general topic, mass media, is too broad for her class’s short paper requirement. Three pages are not enough to cover all the concerns in mass media today. Mariah also realized that although her readers are other communications majors who are interested in the topic, they might want to read a paper about a particular issue in mass media.

The prewriting techniques of brainstorming by freewriting and asking questions helped Mariah think more about her topic, but the following prewriting strategies can help her (and you) narrow the focus of the topic:

- Clustering/Idea Mapping

Narrowing the focus means breaking up the topic into subtopics, or more specific points. Generating lots of subtopics will help you eventually select the ones that fit the assignment and appeal to you and your audience.

Listing is a term often applied to describe any prewriting technique writers use to generate ideas on a topic, including freewriting and asking questions. You can make a list on your own or in a group with your classmates. Start with a blank sheet of paper (or a blank computer screen) and write your general topic across the top. Underneath your topic, make a list of more specific ideas. Think of your general topic as a broad category and the list items as things that fit in that category. Often you will find that one item can lead to the next, creating a flow of ideas that can help you narrow your focus to a more specific paper topic. The following is Mariah’s brainstorming list.

Mariah’s Brainstorming List

- Broadcasting

- Radio Television

- Gaming/Video Games

- Internet Cell Phones

- Smart Phones

- Text Messages

- Tiny Cameras

From this list, Mariah could narrow her focus to a particular technology under the broad category of “mass media.”

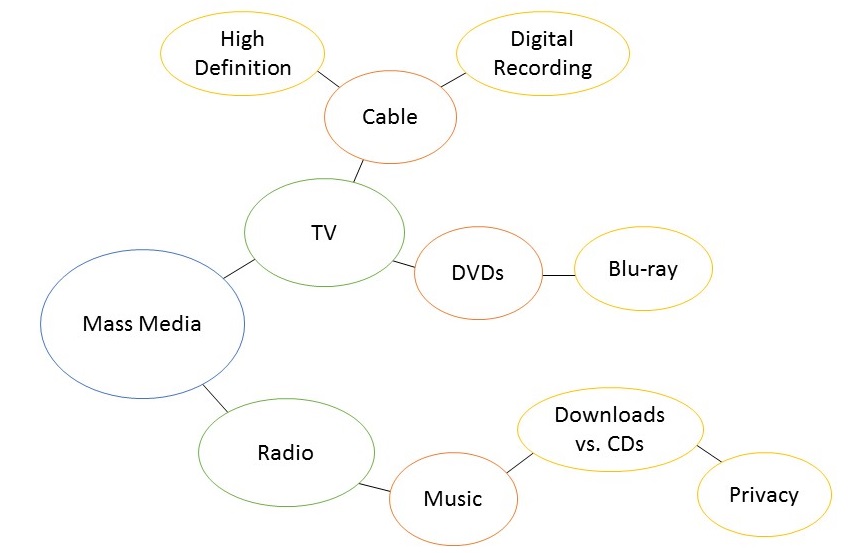

Idea Mapping

Idea mapping, sometimes called clustering or webbing, allows you to visualize your ideas on paper using circles, lines, and arrows. This technique is also known as clustering because ideas are broken down and clustered, or grouped, together. Many writers like this method because the shapes show how the ideas relate or connect, and writers can find a focused topic from the connections mapped. Using idea mapping, you might discover interesting connections between topics that you had not thought of before.

To create an idea map:

- Start by writing your general topic in a circle in the center of a blank sheet of paper. Moving out from the main circle, write down as many concepts and terms ideas you can think of related to your general topic in blank areas of the page. Jot down your ideas quickly–do not overthink your responses. Try to fill the page.

- Once you’ve filled the page, circle the concepts and terms that are relevant to your topic. Use lines or arrows to categorize and connect closely related ideas. Add and cluster as many ideas as you can think of.

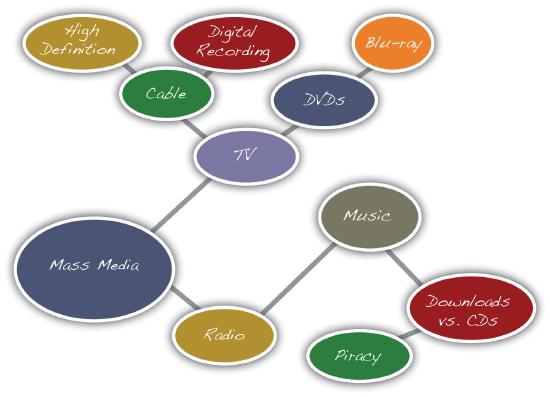

To continue brainstorming, Mariah tried idea mapping. Review Mariah’s idea map in Figure 2.4.1. [1]

Mariah’s Idea Map

Notice Mariah’s largest circle contains her general topic, mass media. Then, the general topic branches into two subtopics written in two smaller circles: television and radio. The subtopic television branches into even more specific topics: cable and DVDs. From there, Mariah drew more circles and wrote more specific ideas: high definition and digital recording from cable and Blu-ray from DVDs. The radio topic led Mariah to draw connections between music, downloads versus CDs, and, finally, piracy. From this idea map, Mariah saw she could consider narrowing the focus of her mass media topic to the more specific topic of music piracy.

Topic Checklist: Developing a Good Topic

- Am I interested in this topic?

- Would my audience be interested?

- Do I have prior knowledge or experience with this topic? If so, would I be comfortable exploring this topic and sharing my experience?

- Do I want to learn more about this topic?

- Is this topic specific?

- Does it fit the length of the assignment?

Prewriting strategies are a vital first step in the writing process. First, they help you choose a broad topic, and then they help you narrow the focus of the topic to a more specific idea. An effective topic ensures that you are ready for the next step: Developing a working thesis and planning the organization of your essay by creating an outline.

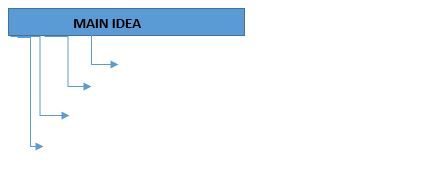

Purpose of an Outline

Once your topic has been chosen, your ideas have been generated through brainstorming techniques, and you’ve developed a working thesis, the next step in the prewriting stage might be to create an outline. Sometimes called a “blueprint,” or “plan” for your paper, an outline helps writers organize their thoughts and categorize the main points they wish to make in an order that makes sense.

The purpose of an outline is to help you organize your paper by checking to see if and how your ideas connect to each other, or whether you need to flesh out a point or two. No matter the length of the paper, from a three-page weekly assignment to a 50-page senior thesis , outlines can help you see the overall picture. Having an outline also helps prevent writers from “getting stuck” when writing the first draft of an essay.

A well-developed outline will show the essential elements of an essay:

- thesis of essay

- main idea of each body paragraph

- evidence/support offered in each paragraph to substantiate the main points

A well-developed outline breaks down the parts of your thesis in a clear, hierarchical manner. Writing an outline before beginning an essay helps the writer organize ideas generated through brainstorming and/or research. In short, a well-developed outline makes your paper easier to write.

The formatting of any outline is not arbitrary ; the system of formatting and number/letter designations creates a visual hierarchy of the ideas, or points, being made in the essay. Major points, in other words, should not be buried in subtopic levels.

Outlines can also be used for revision , oftentimes referred to as backwards, or reverse, outlines. When using an outline for revision purposes, you can identify issues with organization or even find new directions in which to take your essay.

Creating an Outline

- Identify your topic. Put the topic in your own words with a single sentence or phrase to help you stay on topic.

- Determine your main points. What are the main points you want to make to convince your audience? Refer back to the prewriting/brainstorming exercise of answering 5WH questions: “why or how is the main topic important?” Using your brainstorming notes, you should be able to create a working thesis .

- List your main points/ideas in a logical order. You can always change the order later as you evaluate your outline.

- Create sub-points for each major idea. Typically, each time you have a new number or letter, there needs to be at least two points (i.e. if you have an A, you need a B; if you have a 1, you need a 2; etc.). Though perhaps frustrating at first, it is indeed useful because it forces you to think hard about each point. If you can’t create two points, then reconsider including the first in your paper, as it may be extraneous information that may detract from your argument.

- Evaluate. Review your organizational plan, your blueprint for your paper. Does each paragraph have a controlling idea/topic sentence? Is each point adequately supported? Look over what you have written. Does it make logical sense? Is each point suitably fleshed out? Is there anything included that is unnecessary?

Sample Outline

Thesis: Moving college courses to an asynchronous online environment is an effective way of preventing the spread of COVID-19 and offers more students the opportunity to participate.

- Students don’t have to be on-campus, avoiding high-contact living situations

- Students don’t have to travel, avoiding buses and other high-contact travel environments

- Students don’t have to sit in lecture halls, avoiding extended indoor exposure

- Students complete group work via chat rooms or online platforms.

- Students don’t have to touch shared seating, doors, etc.

- Students don’t have to share lab equipment or other materials

- This affords students the ability to complete coursework around a job schedule.

- This format is often family-friendly for those who have children or other familial responsibilities.

- Students may be at high risk or have family members who are high risk

- The reduced exposure of an online environment allows these students to participate without increasing their risk

This section contains material from:

Crowther, Kathryn, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Successful College Composition . 2nd edition. Book 8. Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8 . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- “Mariah’s Idea Map” was derived by Brandi Gomez from an image in: Kathryn Crowther et al, Successful College Composition, 2nd ed. Book 8. (Georgia: English Open Textbooks, 2016), http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/english-textbooks/8 . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . ↵

The method or operation by which something is done or accomplished; a series of continuous actions that result in the achievement of a goal. The writing process refers to the sequence of steps that result in an essay, research paper, or other piece of writing.

The person or group of people who view and analyze the work of a writer, researcher, or other content creator.

Necessary or critical for existence; indispensable or integral.

Intimidating, threatening, or fear-inducing.

To present or put forward an idea.

A statement, usually one sentence, that summarizes an argument that will later be explained, expanded upon, and developed in a longer essay or research paper. In undergraduate writing, a thesis statement is often found in the introductory paragraph of an essay. The plural of thesis is theses .

A lengthy research paper written as part of a graduation requirement for someone who is close to completing their undergraduate requirements for their major and is in their final year of undergraduate study. Like a master’s thesis or a doctoral dissertation, a senior thesis is written to demonstrate mastery over specific subject matter.

The essence of something; those things that compose the foundational elements of a thing; the basics.

Justify, affirm, or corroborate; to show evidence of; to back up a statement, idea, or argument.

A system involving rank. Hierarchical refers to a system that involves a hierarchy. For example, the military is a hierarchical system in which some people outrank others.

To be subject to the judgment of a whim, chance, or personal preference; the opposite of a standardized law, regulation, or rule.

An altered version of a written work. Revising means to rewrite in order to improve and make corrections. Unlike editing, which involves minor changes, revisions include major and noticeable changes to a written work.

Irrelevant, unneeded, or unnecessary.

Occurring at a different time; not occurring at the same time; asynchronous learning refers to work that can be done by a student independently without real-time interaction or guidance from an instructor.

2.4 Prewriting Copyright © 2022 by Kathryn Crowther; Lauren Curtright; Nancy Gilbert; Barbara Hall; Tracienne Ravita; Kirk Swenson; and Terri Pantuso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

An Overview of Academic Writing, Planning, and Prewriting

It can be tempting to dive into an essay immediately without taking the time to really think through what you are writing about and why you might be doing so. This can lead to essays that lack coherence and veer off topic, and not having an organized prewriting process can also create quite a bit of stress for the writer. The quality of writing without prewriting is often inconsistent, as the writer becomes trapped in simply writing and hoping that their initial instincts have set them on the correct course. As you move into your professional life, you will need to adopt a writing process that is consistent, creates effective papers, and, perhaps most importantly, minimizes the stress and anxiety that can come along with any writing endeavor.

Prewriting activities might be intimidating, especially if you have never spent much time on them in the past. However, an effective prewriting process, while perhaps requiring some additional time at the outset, will save you quite a bit of time and stress in the long run. The ideas covered in this chapter will help you map out your paper and consider how your intended audience might affect its structure, tone, and content. In doing so, it will help you escape the “writing and hoping” trap.

We Will Begin Our Journey By Exploring Basic Prewriting Concepts

Read through the following content on effective prewriting strategies, which has been adapted from Ann Inoshita, et al ‘s English Composition: Connect, Collaborate, Communicate. As you do so, try employing some of the strategies to plan out your papers for this course and beyond!

Prewriting is an essential activity for most writers. Through robust prewriting, writers generate ideas, explore directions, and find their way into their writing. When students attempt to write an essay without developing their ideas, strategizing their desired structure, and focusing on precision with words and phrases, they can end up with a “premature draft”—one that is more writer-based than reader-based and, thus, might not be received by readers in the way the writer intended.

In addition, a lack of prewriting can cause students to experience writer’s block. Writer’s block is the feeling of being stuck when faced with a writing task. It is often caused by fear, anxiety, or a tendency toward perfectionism, but it can be overcome through prewriting activities that allow writers to relax, catch their breath, gather ideas, and gain momentum.

The following exist as the goals of prewriting:

- Contemplating the many possible ideas worth writing about.

- Developing ideas through brainstorming, freewriting, and focused writing.

- Planning the structure of the essay overall so as to have a solid introduction, meaningful body paragraphs, and a purposeful conclusion.

Discovering and Developing Ideas

Quick prewriting activities.

Quick strategies for developing ideas include brainstorming, freewriting, and focused writing. These activities are done quickly, with a sense of freedom, while writers silence their inner critic. In her book Wild Mind , teacher and writer Natalie Goldberg describes this freedom as the “creator hand” freely allowing thoughts to flow onto the page while the “editor hand” remains silent. Sometimes, these techniques are done in a timed situation (usually two to ten minutes), which allows writers to get through the shallow thoughts and dive deeper to access the depths of the mind.

Brainstorming begins with writing down or typing a few words and then filling the page with words and ideas that are related or that seem important without allowing the inner critic to tell the writer if these ideas are acceptable or not. Writers do this quickly and without too much contemplation. Students will know when they are succeeding because the lists are made without stopping.

Freewriting is the “most effective way” to improve one’s writing, according to Peter Elbow, the educator and writer who first coined the term “freewriting” in pivotal book Writing Without Teachers , published in 1973. Freewriting is a great technique for loosening up the writing muscle. To freewrite, writers must silence the inner critic and the “editor hand” and allow the “creator hand” a specified amount of time (usually from 10 to 20 minutes) to write nonstop about whatever comes to mind. The goal is to keep the hand moving, the mind contemplating, and the individual writing. If writers feel stuck, they just keep writing “I don’t know what to write” until new ideas form and develop in the mind and flow onto the page.

Focused freewriting entails writing freely—and without stopping, during a limited time—about a specific topic. Once writers are relaxed and exploring freely, they may be surprised about the ideas that emerge.

Operation Beat Writer’s Block: Brainstorming

Let’s start with a basic brainstorming activity.

- Watch the following video from Wisconsin Technical College System (WTCS) and think about what makes brainstorming an essential prewriting activity. What are some of the potential costs of not brainstorming?

- Don’t have a topic yet or need to think through things more before you attempt the mind map? Try the brainstorming exercise embedded in the video itself (at the 1:50 mark).

Next Step: Create a Mind Map to Visualize Your Essay

Mind mapping is an early stage prewriting strategy that you can use to help generate ideas for an essay. It lets you visually map out an essay and then organize and expand these loose ideas into an increasingly coherent and nuanced project. As the following video will demonstrate, mind maps can take a variety of forms, but regardless of what your map looks like, mind maps offer an invaluable way to move past writer’s block and let your ideas flow.

- Watch the following video from Wisconsin Technical College System (WTCS) on mind mapping and free writing.

- When you’ve finished, use the template that follows to map out your essay! Don’t have a topic yet? Try the exercise embedded in the video itself.

Use This Mind Mapping Template to Map Out Your Paper!

Click Here to Download the PDF

Template Created by Scott Ortolano

Researching

Unlike quick prewriting activities, researching is best done slowly and methodically and, depending on the project, can take a considerable amount of time. Researching is exciting, as students activate their curiosity and learn about the topic, developing ideas about the direction of their writing. The goal of researching is to gain background understanding on a topic and to check one’s original ideas against those of experts. However, it is important for the writer to be aware that the process of conducting research can become a trap for procrastinators. Students often feel like researching a topic is the same as doing the assignment, but it’s not.

The two aspects of researching that are often misunderstood are as follows:

- Writers start the research process too late so the information they find never really becomes their own setting themselves up for way more quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing the words of others than is appropriate for the 70% one’s own words and 30% the words of others ratio necessary for college-level research-based writing.

- Writers become so involved in the research process that they don’t start the actual writing process soon enough so as to meet a due date with a well written, edited, and revised finished composition.

Being thoughtful about limiting one’s research time—and using a planner of some sort to organize one’s schedule—is a way to keep oneself from starting the research process too late to

See Part V of this book for more information about researching.

Audience and Purpose

It’s important that writers identify the audience and the purpose of a piece of writing. To whom is the writer communicating? Why is the writer writing? Students often say they are writing for whomever is grading their work at the end. However, most students will be sharing their writing with peers and reviewers (e.g., writing tutors, peer mentors). The audience of any piece of college writing is, at the very minimum, the class as a whole. As such, it’s important for the writer to consider the expertise of the readers, which includes their peers and professors). There are even broader applications. For example, students could even send their college writing to a newspaper or a legislator, or share it online for the purpose of informing or persuading decision-makers to make changes to improve the community. Good writers know their audience and maintain a purpose to mindfully help and intentionally shape their essays for meaning and impact. Students should think beyond their classroom and about how their writing could have an impact on their campus community, their neighborhood, and the wider world.

Planning the Structure of an Essay

Planning based on audience and purpose.

Identifying the target audience and purpose of an essay is a critical part of planning the structure and techniques that are best to use. It’s important to consider the following:

- Is the the purpose of the essay to educate, announce, entertain, or persuade?

- Who might be interested in the topic of the essay?

- Who would be impacted by the essay or the information within it?

- What does the reader know about this topic?

- What does the reader need to know in order to understand the essay’s points?

- What kind of hook is necessary to engage the readers and their interest?

- What level of language is required? Words that are too subject-specific may make the writing difficult to grasp for readers unfamiliar with the topic.

- What is an appropriate tone for the topic? A humorous tone that is suitable for an autobiographical, narrative essay may not work for a more serious, persuasive essay.

Hint: Answers to these questions help the writer to make clear decisions about diction (i.e., the choice of words and phrases), form and organization, and the content of the essay.

Use Audience and Purpose to Plan Language

In many classrooms, students may encounter the concept of language in terms of correct versus incorrect. However, this text approaches language from the perspective of appropriateness. Writers should consider that there are different types of communities, each of which may have different perspectives about what is “appropriate language” and each of which may follow different rules, as John Swales discussed in “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Essentially, Swales defines discourse communities as “groups that have goals or purposes, and use communication to achieve these goals.”

Writers (and readers) may be more familiar with a home community that uses a different language than the language valued by the academic community. For example, many people in Hawai‘i speak Hawai‘i Creole English (HCE colloquially regarded as “Pidgin”), which is different from academic English. This does not mean that one language is better than another or that one community is homogeneous in terms of language use; most people “code-switch” from one “code” (i.e., language or way of speaking) to another. It helps writers to be aware and to use an intersectional lens to understand that while a community may value certain language practices, there are several types of language practices within our community.

What language practices does the academic discourse community value? The goal of first-year-writing courses is to prepare students to write according to the conventions of academia and Standard American English (SAE). Understanding and adhering to the rules of a different discourse community does not mean that students need to replace or drop their own discourse. They may add to their language repertoire as education continues to transform their experiences with language, both spoken and written. In addition to the linguistic abilities they already possess, they should enhance their academic writing skills for personal growth in order to meet the demands of the working world and to enrich the various communities they belong to.

Use Techniques to Plan Structure

Before writing a first draft, writers find it helpful to begin organizing their ideas into chunks so that they (and readers) can efficiently follow the points as organized in an essay.

First, it’s important to decide whether to organize an essay (or even just a paragraph) according to one of the following:

- Chronological order (organized by time)

- Spatial order (organized by physical space from one end to the other)

- Prioritized order (organized by order of importance)

There are many ways to plan an essay’s overall structure, including mapping and outlining.

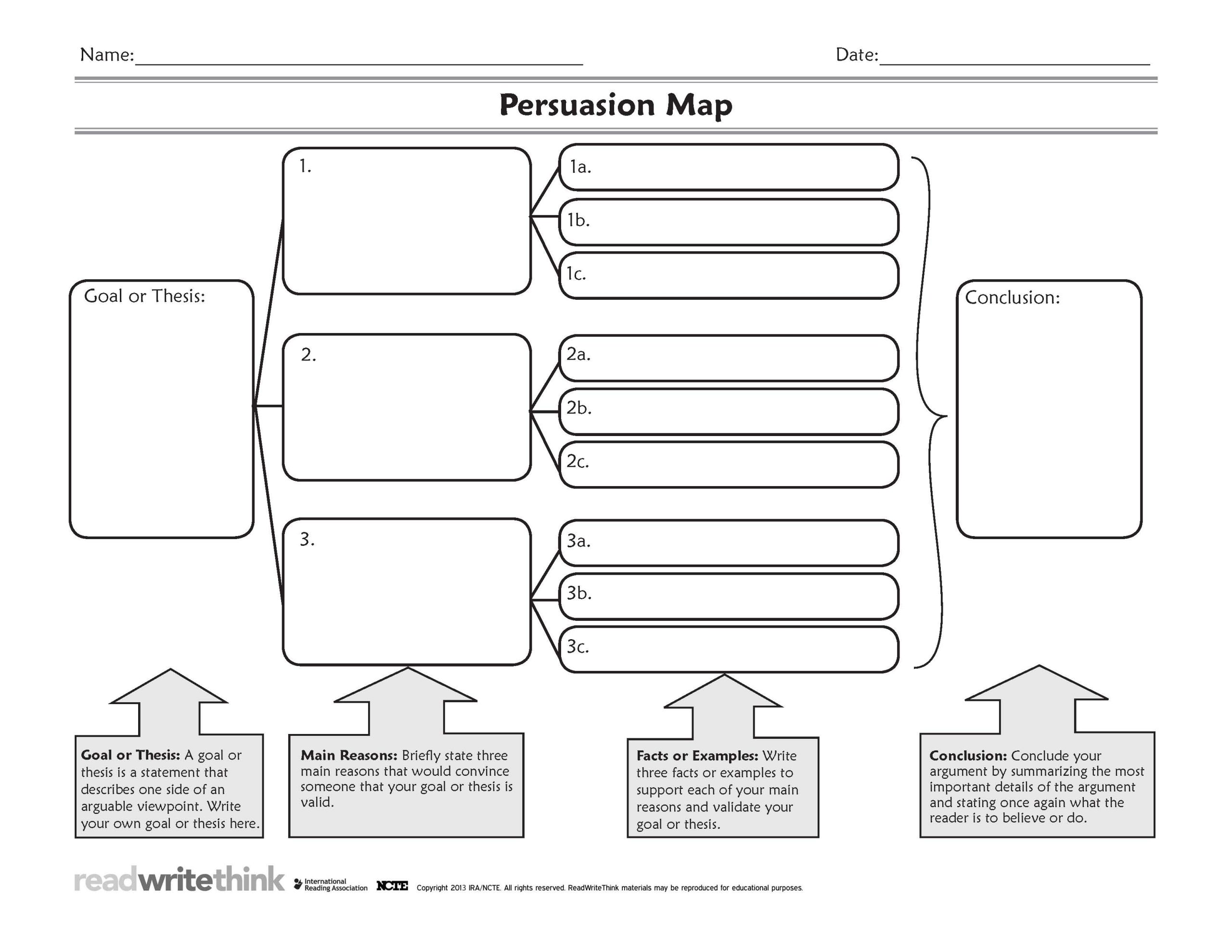

Mapping (which sometimes includes using a graphic organizer) involves organizing the relationships between the topic and other ideas. The following is example (from ReadWriteThink.org, 2013) of a graphic organizer that could be used to write a basic, persuasive essay:

Outlining is also an excellent way to plan how to organize an essay. Formal outlines use levels of notes, with Roman numerals for the top level, followed by capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters. Here’s an example:

- Hook/Lead/Opener: According to the Leilani was shocked when a letter from Chicago said her “Aloha Poke” restaurant was infringing on a non-Hawaiian Midwest restaurant that had trademarked the words “aloha” (the Hawaiian word for love, compassion, mercy, and other things besides serving as a greeting) and “poke” (a Hawaiian dish of raw fish and seasonings).

- Background information about trademarks, the idea of language as property, the idea of cultural identity, and the question about who owns language and whether it can be owned.

- Thesis Statement (with the main point and previewing key or supporting points that become the topic sentences of the body paragraphs): While some business people use language and trademarks to turn a profit, the nation should consider that language cannot be owned by any one group or individual and that former (or current) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups, and legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good of internal peace of the country.

- Legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good and internal peace of the country.

- Conclusion ( Revisit the Hook/Lead/Opener, Restate the Thesis, End with a Twist— a strong more globalized statement about why this topic was important to write about)

Note about outlines: Informal outlines can be created using lists with or without bullets. What is important is that main and subpoint ideas are linked and identified.

- Use 10 minutes to freewrite with the goal to “empty your cup”—writing about whatever is on your mind or blocking your attention on your classes, job, or family. This can be a great way to help you become centered, calm, or focused, especially when dealing with emotional challenges in your life.

- For each writing assignment in class, spend three 10-minute sessions either listing (brainstorming) or focused-writing about the topic before starting to organize and outline key ideas.

- Before each draft or revision of assignments, spend 10 minutes focused-writing an introduction and a thesis statement that lists all the key points that supports the thesis statement.

- Have a discussion in your class about the various language communities that you and your classmates experience in your town or on your island.

- Create a graphic organizer that will help you write various types of essays.

- Create a metacognitive, self-reflective journal: Freewrite continuously (e.g., 5 times a week, for at least 10 minutes, at least half a page) about what you learned in class or during study time. Document how your used your study hours this week, how it felt to write in class and out of class, what you learned about writing and about yourself as a writer, how you saw yourself learning and evolving as a writer, what you learned about specific topics. What goals do you have for the next week?

During the second half of the semester, as you begin to tackle deeper and lengthier assignments, the journal should grow to at least one page per day, at least 20 minutes per day, as you use journal writing to reflect on writing strategies (e.g., structure, organization, rhetorical modes, research, incorporating different sources without plagiarizing, giving and receiving feedback, planning and securing time in your schedule for each task involved in a writing assignment) and your ideas about topics, answering research questions, and reflecting on what you found during research and during discussions with peers, mentors, tutors, and instructors. The journal then becomes a record of your journey as a writer, as well as a source of freewriting on content that you can shape into paragraphs for your various assignments.

Works Cited

Elbow, Peter. Writing Without Teachers . 2nd edition, 1973, Oxford UP, 1998.

Goldberg, Natalie. Wild Mind : Living the Writer’s Life. Bantam Books, 1990.

Swales, John. “The Concept of Discourse Community.” Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings , 1990, pp. 21-32.

For more about discourse communities, see the online class by Robert Mohrenne “ What is a Discourse Community? ” ENC 1102 13 Fall 0027. University of Central Florida, 2013.

Sources Used to Create This Chapter

The majority of the content for this section has been adapted from OER Material from “Prewriting, ” in Ann Inoshita, et al’s English Composition: Connect, Collaborate, Communicate (2019). This work was published under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States (CC BY 3.0 US) License.

Media Resources

Remixed and Compiled by Scott Ortolano

An Overview of Academic Writing, Planning, and Prewriting Copyright © by Leonard Owens III; Tim Bishop; and Scott Ortolano is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

GKT103: General Knowledge for Teachers – Essays

Pre-Writing

Sitting down for an exam and reading an essay prompt can be intimidating. One way to ease your nerves and help you focus on the task is to pre-write. Pre-writing is a way to think through the essay question, gather your thoughts, and keep yourself from becoming overwhelmed. This resource explains pre-writing and shows strategies you can practice now and use on exam day to help ensure that you start your essay writing off on the right foot!

Planning the Structure of an Essay

Planning based on audience and purpose.

Identifying the target audience and purpose of an essay is a critical part of planning the structure and techniques that are best to use. It's important to consider the following:

- Is the the purpose of the essay to educate, announce, entertain, or persuade?

- Who might be interested in the topic of the essay?

- Who would be impacted by the essay or the information within it?

- What does the reader know about this topic?

- What does the reader need to know in order to understand the essay's points?

- What kind of hook is necessary to engage the readers and their interest?

- What level of language is required? Words that are too subject-specific may make the writing difficult to grasp for readers unfamiliar with the topic.

- What is an appropriate tone for the topic? A humorous tone that is suitable for an autobiographical, narrative essay may not work for a more serious, persuasive essay.

Hint: Answers to these questions help the writer to make clear decisions about diction (i.e., the choice of words and phrases), form and organization, and the content of the essay.

Use Audience and Purpose to Plan Language

In many classrooms, students may encounter the concept of language in terms of correct versus incorrect. However, this text approaches language from the perspective of appropriateness. Writers should consider that there are different types of communities, each of which may have different perspectives about what is "appropriate language" and each of which may follow different rules, as John Swales discussed in "The Concept of Discourse Community". Essentially, Swales defines discourse communities as "groups that have goals or purposes, and use communication to achieve these goals".

Writers (and readers) may be more familiar with a home community that uses a different language than the language valued by the academic community. For example, many people in Hawai‘i speak Hawai‘i Creole English (HCE colloquially regarded as "Pidgin"), which is different from academic English. This does not mean that one language is better than another or that one community is homogeneous in terms of language use; most people "code-switch" from one "code" (i.e., language or way of speaking) to another. It helps writers to be aware and to use an intersectional lens to understand that while a community may value certain language practices, there are several types of language practices within our community.

What language practices does the academic discourse community value? The goal of first-year-writing courses is to prepare students to write according to the conventions of academia and Standard American English (SAE). Understanding and adhering to the rules of a different discourse community does not mean that students need to replace or drop their own discourse. They may add to their language repertoire as education continues to transform their experiences with language, both spoken and written. In addition to the linguistic abilities they already possess, they should enhance their academic writing skills for personal growth in order to meet the demands of the working world and to enrich the various communities they belong to.

Use Techniques to Plan Structure

Before writing a first draft, writers find it helpful to begin organizing their ideas into chunks so that they (and readers) can efficiently follow the points as organized in an essay.

First, it's important to decide whether to organize an essay (or even just a paragraph) according to one of the following:

- Chronological order (organized by time)

- Spatial order (organized by physical space from one end to the other)

- Prioritized order (organized by order of importance)

There are many ways to plan an essay's overall structure, including mapping and outlining.

Mapping (which sometimes includes using a graphic organizer) involves organizing the relationships between the topic and other ideas. The following is example (from ReadWriteThink.org, 2013) of a graphic organizer that could be used to write a basic, persuasive essay:

Outlining is also an excellent way to plan how to organize an essay. Formal outlines use levels of notes, with Roman numerals for the top level, followed by capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters. Here's an example:

- Hook/Lead/Opener: According to the Leilani was shocked when a letter from Chicago said her "Aloha Poke" restaurant was infringing on a non-Hawaiian Midwest restaurant that had trademarked the words "aloha" (the Hawaiian word for love, compassion, mercy, and other things besides serving as a greeting) and "poke" (a Hawaiian dish of raw fish and seasonings).

- Background information about trademarks, the idea of language as property, the idea of cultural identity, and the question about who owns language and whether it can be owned.

- Thesis Statement (with the main point and previewing key or supporting points that become the topic sentences of the body paragraphs): While some business people use language and trademarks to turn a profit, the nation should consider that language cannot be owned by any one group or individual and that former (or current) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups, and legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good of internal peace of the country.

- Legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good and internal peace of the country.

- Conclusion (Revisit the Hook/Lead/Opener, Restate the Thesis, End with a Twist - a strong more globalized statement about why this topic was important to write about)

Note about outlines: Informal outlines can be created using lists with or without bullets. What is important is that main and subpoint ideas are linked and identified.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Introduction to Prewriting (Invention)

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you sit down to write...

- Does your mind turn blank?

- Are you sure you have nothing to say?

If so, you're not alone. Many writers experience this at some time or another, but some people have strategies or techniques to get them started. When you are planning to write something, try some of the following suggestions.

You can try the textbook formula:

- State your thesis.

- Write an outline.

- Write the first draft.

- Revise and polish.

. . . but that often doesn't work.

Instead, you can try one or more of these strategies:

Ask yourself what your purpose is for writing about the subject.

There are many "correct" things to write about for any subject, but you need to narrow down your choices. For example, your topic might be "dorm food." At this point, you and your potential reader are asking the same question, "So what?" Why should you write about this, and why should anyone read it?

Do you want the reader to pity you because of the intolerable food you have to eat there?

Do you want to analyze large-scale institutional cooking?

Do you want to compare Purdue's dorm food to that served at Indiana University?

Ask yourself how you are going to achieve this purpose.

How, for example, would you achieve your purpose if you wanted to describe some movie as the best you've ever seen? Would you define for yourself a specific means of doing so? Would your comments on the movie go beyond merely telling the reader that you really liked it?

Start the ideas flowing

Brainstorm. Gather as many good and bad ideas, suggestions, examples, sentences, false starts, etc. as you can. Perhaps some friends can join in. Jot down everything that comes to mind, including material you are sure you will throw out. Be ready to keep adding to the list at odd moments as ideas continue to come to mind.

Talk to your audience, or pretend that you are being interviewed by someone — or by several people, if possible (to give yourself the opportunity of considering a subject from several different points of view). What questions would the other person ask? You might also try to teach the subject to a group or class.

See if you can find a fresh analogy that opens up a new set of ideas. Build your analogy by using the word like. For example, if you are writing about violence on television, is that violence like clowns fighting in a carnival act (that is, we know that no one is really getting hurt)?

Take a rest and let it all percolate.

Summarize your whole idea.

Tell it to someone in three or four sentences.

Diagram your major points somehow.

Make a tree, outline, or whatever helps you to see a schematic representation of what you have. You may discover the need for more material in some places. Write a first draft.

Then, if possible, put it away. Later, read it aloud or to yourself as if you were someone else. Watch especially for the need to clarify or add more information.

You may find yourself jumping back and forth among these various strategies.

You may find that one works better than another. You may find yourself trying several strategies at once. If so, then you are probably doing something right.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.6: Prewriting Strategies

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 20696

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

If you think that a blank sheet of paper or a blinking cursor on the computer screen is a scary sight, you are not alone. Many writers, students, and employees find that beginning to write can be intimidating. When faced with a blank page, however, experienced writers remind themselves that writing, like other everyday activities, is a process. Every process, from writing to cooking, bike riding, and learning to use a new cell phone, will get significantly easier with practice.

Just as you need a recipe, ingredients, and proper tools to cook a delicious meal, you also need a plan, resources, and adequate time to create a good written composition. In other words, writing is a process that requires following steps and using strategies to accomplish your goals.

These are the five steps in the writing process:

- Outlining the structure of ideas

- Writing a rough draft

Effective writing can be simply described as good ideas that are expressed well and arranged in the proper order. This chapter will give you the chance to work on all these important aspects of writing. Although many more prewriting strategies exist, this chapter covers six: using experience and observations, free writing, asking questions, brainstorming, mapping, and searching the Internet. Using the strategies in this chapter can help you overcome the fear of the blank page and confidently begin the writing process.

Prewriting means just what it says—it’s the writing that occurs before you actually write a draft. Richard Nordquist writes that:

“In composition, the term prewriting refers to any activity that helps a writer think about a topic, determine a purpose, analyze an audience, and prepare to write. Prewriting is closely related to the art of invention in classical rhetoric."

‘The objective of prewriting,’ according to Roger Caswell and Brenda Mahler, ‘is to prepare students for writing by allowing them to discover what they know and what else they need to know. Prewriting invites exploration and promotes the motivation to write’ ( Strategies for Teaching Writing , 2004).” [1]

In order to explore and identify what might be fruitful ideas for writing, I tend to jot concepts, phrases, and notes to myself. Sometimes I draw linkages to connect related ideas. Other writers tend to just write in order to explore and identify patterns of thought. Still other writers list out all of the concepts and information they can think of around a certain topic, and then narrow and refine their lists. Visual thinkers may draw a mind map or other pictures. Others start writing a really “drafty draft” of an essay, and then circle back into prewriting strategies to develop ideas. Any prewriting strategy is fine, depending on “how your mind thinks” and how you like to discover and explore ideas.

Prewriting is the stage of the writing process during which you transfer your abstract thoughts into more concrete ideas in ink on paper (or in type on a computer screen). Although prewriting techniques can be helpful in all stages of the writing process, the following four strategies are best used when initially deciding on a topic:

- Using experience and observations

Free writing

- Asking questions

At this stage in the writing process, it is okay if you choose a general topic. Later you will learn more prewriting strategies that will narrow the focus of the topic.

Choosing a Topic