Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

15.7 Definition Essay

Learning objective.

- Read an example of the definition rhetorical mode.

Defining Good Students Means More Than Just Grades

Many people define good students as those who receive the best grades. While it is true that good students often earn high grades, I contend that grades are just one aspect of how we define a good student. In fact, even poor students can earn high grades sometimes, so grades are not the best indicator of a student’s quality. Rather, a good student pursues scholarship, actively participates in class, and maintains a positive, professional relationship with instructors and peers.

Good students have a passion for learning that drives them to fully understand class material rather than just worry about what grades they receive in the course. Good students are actively engaged in scholarship, which means they enjoy reading and learning about their subject matter not just because readings and assignments are required. Of course, good students will complete their homework and all assignments, and they may even continue to perform research and learn more on the subject after the course ends. In some cases, good students will pursue a subject that interests them but might not be one of their strongest academic areas, so they will not earn the highest grades. Pushing oneself to learn and try new things can be difficult, but good students will challenge themselves rather than remain at their educational comfort level for the sake of a high grade. The pursuit of scholarship and education rather than concern over grades is the hallmark of a good student.

Class participation and behavior are another aspect of the definition of a good student. Simply attending class is not enough; good students arrive punctually because they understand that tardiness disrupts the class and disrespects the professors. They might occasionally arrive a few minutes early to ask the professor questions about class materials or mentally prepare for the day’s work. Good students consistently pay attention during class discussions and take notes in lectures rather than engage in off-task behaviors, such as checking their cell phones or daydreaming. Excellent class participation requires a balance between speaking and listening, so good students will share their views when appropriate but also respect their classmates’ views when they differ from their own. It is easy to mistake quantity of class discussion comments with quality, but good students know the difference and do not try to dominate the conversation. Sometimes class participation is counted toward a student’s grade, but even without such clear rewards, good students understand how to perform and excel among their peers in the classroom.

Finally, good students maintain a positive and professional relationship with their professors. They respect their instructor’s authority in the classroom as well as the instructor’s privacy outside of the classroom. Prying into a professor’s personal life is inappropriate, but attending office hours to discuss course material is an appropriate, effective way for students to demonstrate their dedication and interest in learning. Good students go to their professor’s office during posted office hours or make an appointment if necessary. While instructors can be very busy, they are usually happy to offer guidance to students during office hours; after all, availability outside the classroom is a part of their job. Attending office hours can also help good students become memorable and stand out from the rest, particularly in lectures with hundreds enrolled. Maintaining positive, professional relationships with professors is especially important for those students who hope to attend graduate school and will need letters of recommendation in the future.

Although good grades often accompany good students, grades are not the only way to indicate what it means to be a good student. The definition of a good student means demonstrating such traits as engaging with course material, participating in class, and creating a professional relationship with professors. While every professor will have different criteria for earning an A in their course, most would agree on these characteristics for defining good students.

Online Definition Essay Alternatives

Judy Brady provides a humorous look at responsibilities and relationships in I Want a Wife :

- http://www.columbia.edu/~sss31/rainbow/wife.html

Gayle Rosenwald Smith shares her dislike of the name for a sleeveless T-shirt, The Wife-Beater :

- http://faculty.gordonstate.edu/cperkowski/1101/WifeBeater.pdf

Philip Levine defines What Work Is :

- http://www.ibiblio.org/ipa/poems/levine/what_work_is.php

- http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/what-work-is

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

A community blog focused on educational excellence and equity

About the topic

Explore classroom guidance, techniques, and activities to help you meet the needs of ALL students.

most recent articles

Shaking Up High School Math

Executive Functions and Literacy Skills in the Classroom

Connecting and Communicating With Families to Help Break Down Barriers to Learning

Discover new tools and materials to integrate into you instruction.

Culture, Community, and Collaboration

Vertical Progression of Math Strategies – Building Teacher Understanding

“Can I have this? Can I have that?”

Find instructions and recommendations on how to adapt your existing materials to better align to college- and career-ready standards.

To Teach the Truth

Helping Our Students See Themselves and the World Through the Books They Read in Our Classrooms

Textbooks: Who Needs Them?

Learn what it means for instructional materials and assessment to be aligned to college- and career-ready standards.

Let’s Not Make Power ELA/Literacy Standards and Talk About Why We Didn’t

What to Consider if You’re Adopting a New ELA/Literacy Curriculum

Not Your Mom’s Professional Development

Delve into new research and perspectives on instructional materials and practice.

Summer Reading Club 2023

Synergy between College and Career Readiness Standards-Aligned Instruction and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy

Children Should be Seen AND Heard

- Submissions Guidelines

- About the Blog

What Is Academic Success (Student Learning)?

Reimagining how to foster academic success in the classroom and document students' growth

“Teachers genuinely believe in the intellectual potential of these students [of color] and accept, unequivocally, their responsibility to facilitate its realization without ignoring, demeaning, or neglecting their ethnic and cultural identities. They build toward academic success from a basis of cultural validation and strength” (Geneva Gay, 2001).

Within the field of education, “academic success” is a widely used construct that is equated to “student achievement” and often linked to students’ performance on standardized test scores. This narrowed definition of academic success justifies the school failure of Black students and students learning English and shifts the blame to students, their families, and communities.

In her seminal article, “But That’s Just Good Teaching! The Case for Culturally Relevant Pedagogy,” Dr. Ladson-Billings stated that “despite the current social inequities and hostile classroom environment, students must develop their academic skill” (p. 160). In 2014, she clarified that her stance on “academic success” must center “the intellectual growth that students experience as a result of classroom instruction and learning experience” (p. 75).

The measure of academic success should not be solely based on test scores from standardized tests and other traditional definitions of success. Educators and researchers have recognized that White middle-class standards are often set as the benchmarks of success. Schools typically expect all students, regardless of their background or culture, to assimilate to these standards. While Dr. Ladson-Billings and other scholars have affirmed that it is important for all students to have exposure to and know how to navigate the dominant culture, all educators must strive for equity within the traditional definitions of academic success, thus expanding the definition in broader and richer terms to center student learning and academic growth over time.

To move toward equitable educational outcomes for Black students and students learning English, we must reimagine how to foster academic success in the classroom and document students’ growth. To do this, we must shift toward measuring “academic success” through a range of different means, including but not limited to project-based learning, portfolios, and student reflection. Building academic success requires that teachers take responsibility for their students’ learning, create and sustain learning partnerships with students and families, and build students’ agency in their learning while consistently calling out and mitigating the structural racism and injustices that limit historically resilient students’ academic growth.

What are we learning?

Through our work with educators, we have noted several practices that speak to how they foster academic success with their historically resilient students. It is important to note that these educators highlighted the interwoven nature of high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) and teacher practices in fostering student learning and academic growth and success. Below, we provide some examples of how educators have engaged standards-aligned instructional materials in service of culturally relevant instruction and an expanded definition of academic success.

Teachers who embrace cultural relevance believe that historically resilient students have what it takes to succeed, hold high expectations for them, reaffirm their humanity, and create opportunities to experience learning growth. For example, in a conversation with one of the educators, she noted that:

“We need to make sure that our actions as educators are never putting barriers in front of students, and in fact, we are pushing them to shatter glass ceilings, regardless of any label that society may put on them. I think my purpose [as an educator] is to make sure that all of our students succeed beyond our expectations, but especially our students of color who usually are counted out of advanced classes and advanced opportunities.”

Teachers we spoke to know where their students’ strengths and areas of weakness are and use them as a starting point when teaching. This deep knowledge of students is based on a genuine commitment to students’ academic success and requires an investment in every student in the classroom. For example, one teacher described her interactions with students during a math lesson. She noted that:

“I’m able to identify which students really understood the task at hand, and which students really need to be extended a challenge because they kind of had a firm grasp on the content. Then I ask myself, “What students do I need to revisit some previous learning because they may be missing some of those foundational pieces that I need to build on so that they can access the materials on the grade level that I’m presenting?”

Another teacher stressed the importance of checking for students’ understanding of the content before moving on to new materials. This teacher noted that:

“I need that time to come back with them and go over the assignment and talk about those mistakes and help them fix it, and talk about error analysis, things like that.”

Here, we see the teacher taking ownership of and demonstrating a commitment to student learning and academic growth when students do not fully understand the content and dedicating time to reteach and provide scaffolds until the content is understood. This kind of messaging can signal to students that their teacher is invested in them.

As we’ve learned more about the practical applications of Dr. Ladson-Billings’ work, we’ve come to understand how academic success, particularly viewed through the lens of student growth, can’t be defined by a test score or even by successful completion of an assignment. Teachers who embody this understanding move past these limited definitions of academic success to see how their academic learning and growth have evolved over time. This means they scaffold tasks based on what their students bring to the classroom and use assessment as a tool to understand what their students know and can do, not as a way to identify gaps to fill.

Significant time is spent understanding students’ prior knowledge and the grade-level learning targets to craft instruction that is meaningful for all students. Standards-aligned instructional materials have the potential to play an essential role by clearly defining grade-level targets and offering carefully designed activities that may be adapted to meet the needs of all learners. When standard-aligned instructional materials are used in conjunction with culturally responsive pedagogy, we are learning that both student engagement and learning experiences expand across the students’ range of growth and potential. We hope you continue on this journey with us as we explore how teachers work with standards-aligned materials in service of the other aspects of culturally relevant pedagogy.

Ladson‐Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into practice , 34 (3), 159-165.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: aka the remix. HarvardEducational Review , 84 (1), 74-84.

- Equity in Education

2 thoughts on “ What Is Academic Success (Student Learning)? ”

Equity is a magical place many never see as often as I to intervene and create equity, the reality of what students live and face daily is so politically enforced that I want to scream. The hope that I am challenged with then comes from every individual that is committed to do the work of educating. I find hope in people who are really charged to educate and lift others. My personal dilemma is am I involved in meaningful work. I was at LSU ( Louisiana State University) while I taught in the public schools of Baton Rouge. A woman walked up to me one day on campus and said, ” Why are you teaching with them those people don’t care.” I just looked at her because I was truly one of those people. What do you do when you know the best effort has gone out and Harvard intellectuals say pasting test scores are fleeting. I really believe we must trust that what are engaging in is worth the effort no matter what others think. The saying, “One does better when they know better,” only works when there is a value to do better. Money isn’t the best elevator in education it only helps our commitments and values to challenge the status quo is the best. I want to be the best educator I can be today. Jo Dawkins

Some thoughts on academic success: 1) There is a disconnect between what invested educators consider “academic success” and what others consider this to be. For example, I find that the majority of students and their parents want good grades, but the grades (letter or number) matter more than WHETHER THE STUDENT HAS ACTUALLY LEARNED ANYTHING. This is seen when teachers that give out easy A’s and B’s are lauded as “wonderful” while teachers that “take ownership” and have high expectations for all students (which involves MUCH MORE WORK for the teachers as they must actually read and mark up student work, conference with students and provide extra help, and then grade final versions) are criticized as too demanding when after all that effort, some students get the poor grades they deserve. Another example of this is evident when more than ever before, students are off on VACATION throughout the school year. These incidents were becoming more frequent before the pandemic, and now they have further multiplied. Parents just take their children out of school whenever they want. Well, their message is loud and clear — they must feel that being in school is not connected to academic success and/or school is just not that important. There is a disconnect between academic success and what that means and entails. 2) Academic success needs to be based on more than grades. Not only because of the above-mentioned situations where a letter or number becomes the end-all-be-all rather than the knowledge it represents but because success based solely on a grade is very limiting to students that have different learning styles and abilities. I like to conference with students and have them tell me about the content — I find that this reveals very quickly whether they understand or are having difficulty. Another way to check understanding is by having students demonstrate it in some tangible way — teach another student, teach the class, etc. When a student can do this, he or she has achieved success.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

About the Author: Abigail Amoako Kayser, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor at the College of Education at California State University, Fullerton in the Department of Elementary and Bilingual Education. She is a Fulbright Scholar and a former elementary teacher. Through her research and teaching, she aims to advance our understanding of how teachers ensure equitable, just, and anti-racist educational experiences and outcomes for historically resilient students in the U.S. and Ghana.

What Is Culturally Relevant Pedagogy?

What Is Critical Consciousness?

Stay in touch.

Like what you’re reading? Sign up to receive emails about new posts, free resources, and advice from educators.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Defining and Measuring Academic Success

2015, Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation

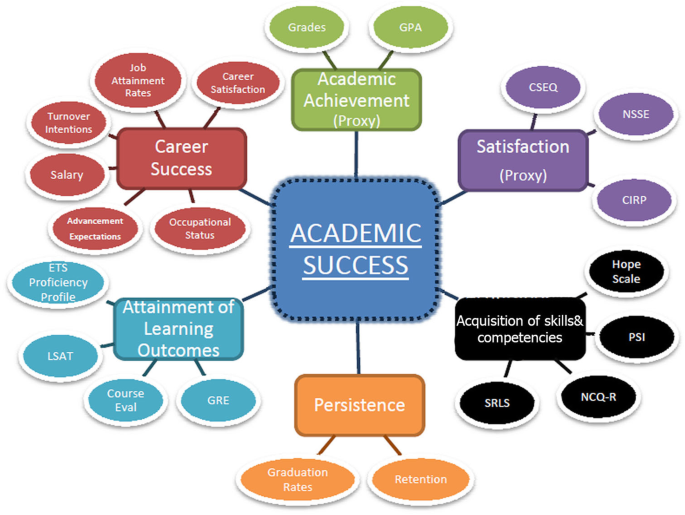

Despite, and perhaps because of its amorphous nature, the term ‘academic success’ is one of the most widely used constructs in educational research and assessment within higher education. This paper conducts an analytic literature review to examine the use and operationalization of the term in multiple academic fields. Dominant definitions of the term are conceptually evaluated using Astin’s I-E-O model resulting in the proposition of a revised definition and new conceptual model of academic success. Measurements of academic success found throughout the literature are presented in accordance with the presented model of academic success. These measurements are provided with details in a user-friendly table (Appendix B). Results also indicate that grades and GPA are the most commonly used measure of academic success. Finally, recommendations are given for future research and practice to increase effective assessment of academic success.

Related Papers

Zin Eddine Dadach

The final goals of this study is to investigate the impact of using a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) as a research based learning tool on the performance and motivation of each student in an industrial automation course. For this purpose, ten PLC’s lab experiments are used to visualize the theories covered in the learning outcomes (CLO’S) of the course and investigate their applications in industrial automation. The success of the PLC as research-based tool are demonstrated by the fact the performance of 40 students (73%) is higher in this course than their corresponding average performance in the college. Moreover, using the Dadach Motivation Factor (DMF) as tool to measure motivation of students, our results also indicate that thirty-five students (63.63%) were motivated during the course. In overall, this investigation shows that the utilization of ten PLC lab experiments for the visualization of the opaque theory of industrial automation is successful.

Knowledge and Performance Management

Mercy Ogbeta

Academic resilience and emotional intelligence are considered important personal resources for furthering students’ academic performance. However, many educational organizations seem to trivialize the performance implications of these constructs in teachings and curriculum. Consequently, it can decrease not just their academic performance but also their employability, as they lack the generic competencies to adapt and survive in a stressful context. Even so, empirical evidence on integrating academic resilience, emotional intelligence, and academic performance remains unexplored in the Nigerian university context. Therefore, the study aimed to investigate the linkages between academic resilience, emotional intelligence, and academic performance in Nigeria. The partial least square (PLS) modeling method was utilized for testing the stated hypotheses with data collected from 179 final year undergraduate students in the regular B.Sc. Business Administration and B.Sc. Marketing program ...

International Journal of Higher Education

margie roma

Higher educational institutions (HEIs) play a substantial role in the development of knowledge and skills that can cope with the demands of industries in the fourth industrial revolution (4IR). This study examined the alignment between the current assessment practices used by HEIs and the competencies demanded by the hospitality and tourism industry. It also aimed to develop an assessment strategy typology that could specifically target the competencies required by the industry. In addition, the study was able to determine the three most and the three least preferred assessment methods as perceived by the hotel and restaurant management students in a private university in Mandaluyong City, Philippines. The findings revealed the common assessment methods employed by teachers in Hospitality and Tourism Managemnt (HTM) major courses. The study argues that the use of these identified assessment methods likewise contribute in developing the emerging skills in the 4IR such as sense-maki...

College & Research Libraries

Angela Rockwell

Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation

Donna H Ziegenfuss

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education

Saumya Kumar

The significance accorded to the amorphous concept of Academic Performance of students is immense, owing to the mere reason that better performances academically set the prospect for the better future of any nation. Likewise, understanding the integrities of the concept holds a great connotation. The current paper aims to present a review of the various definitions of "academic performance" along with the factors perceived to have an effect on the academic performance of students belonging to Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Additionally, an effort has also been made to gain an insight into the reliability of "Grade Point Average" (GPA) as a method for measuring academic performance.

Wanda Robinson

Educating a sufficient nursing workforce to provide high quality, compassionate, and ethical care to an increasingly diverse population is an ongoing challenge and opportunity for nurse educators. Current literature highlights the importance of engaging students in learning to strengthen student achievements. Fostering student engagement within nursing courses is particularly important. Grit (consistency of interest and perseverance of effort) is a factor that may be associated with student course engagement. Demographic characteristics of age, gender, race/ethnicity, prior education, degree program, and self-reported grade point average (GPA) also may be factors associated with student course engagement. Guided by a conceptual model derived from the literature, the purpose of this study was to determine whether grit and demographic characteristics were associated with student course engagement (skills, emotion, participation/interaction, and performance) within a nursing course. Us...

Health and Academic Achievement

Marcela Verešová

Marilee Bresciani Ludvik

The clash of whether higher education should serve the public good or economic stimulation seems more alive than ever to some, and to others, it has come to an end. Not agreeing on the purpose of American higher education certainly makes it difficult to know whether educators are being responsible for delivering what is expected of them. Rather than reviewing the important debate that has already taken place, this chapter seeks to merge the two seemingly juxtaposed disagreements and discuss how bringing the two purposes together may influence how we examine accountability. As such, an inquiry model, including ways to gather and interpret institutional performance indicators for accountability is posited. Practical suggestions for implementation of this methodology are provided.

RELATED PAPERS

Community College Journal of Research and Practice

Juliann McBrayer

Lee O Farrell

Higher education's response to exponential societal shifts

Jillian Kinzie

Higher Education Studies

karma El Hassan

Matthew Gaertner

Monica Burnette

Ann Popkess

The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning

Lynette Bryan

Liz Chinlund

Journal of College Student Development

Fred Newton

WHY SUPERVISORS MATTER FOR COLLEGE STUDENTS: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TYPE OF EMPLOYMENT AND STUDENT OUTCOMES

Dr. Justin Hultman

Heather Friesen

Meltem Ozmutlu

ANIMA Indonesian Psychological Journal

titik kristiyani

Shafeeka Dockrat

mohamed deen

International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research

Nahla Moussa

Richard Okundia

The Journal of Campus Activities, Practice, and Scholarship

Christy Moran Craft

MIRDEC-10th, International Academic Conference Global and Contemporary Trends in Social Science (Global Meeting of Social Science Community) 06-08 November 2018, Barcelona, Spain. ISBN: 978-605-81247-2-1. https://www.mirdec.com/barca2018proceedings.

Nazmi Xhomara

Journal of Hispanic Higher Education

Glai Martinez

The problem of college readiness, edited by William G. Tierney and Julia C. Duncheon

Julia Duncheon

Mohamed Tejan Tarawally Deen

Kristopher A Oliveira

David Edens

The Professional Counselor

Jeffrey Warren

Jefferson Chavez

International Journal of Knowledge and learning

David Cheng

Oscar Cervantes

Journal of Multidisciplinary Research

Cristina Lopez Vergara

Azucena Montoya

Journal for the Advancement of Educational Research

Dr. Justin Hultman , Dr. Daniel Eadens

Proceedings of the 2010 …

Hala Bayoumy

putri hazarianti

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- NEP 2020 Curriculum

- Centre of Wellbeing

- LRPAX Model

- Balanced Schooling

- Safety Certification

- Co-Curricular Learning

- Digital Learning

- Chimney Hills CBSE

- Electronic City CBSE

- Yelahanka CBSE

- Bannerghatta CBSE

- Whitefield CBSE

- Airoli ICSE

- Balkum Thane CBSE

- Ghodbunder Thane ICSE

- Dombivli CBSE

- Upper Thane CBSE

- Kharadi CBSE

- Wakad (CBSE)

- Wakad (ICSE)

- Metro Campus CBSE

- Hitec City CBSE

- Hitech City CBSE

The Meaning, Necessity, and Significance of Academic Success

In today’s ever-evolving globalised world, academic success is a term that resonates with students, educators, parents, and policymakers alike. But what exactly does it mean, and why is it so highly sought after? This essay delves into the concept of academic success, presenting illustrative examples and pinpointing essential skills that contribute to achieving it.

Academic Success Meaning

Academic success, a phrase deeply embedded in educational institutions across the globe, refers to the fulfilment of educational goals set within an academic environment. However, it goes beyond just acquiring high marks in examinations; it encompasses a deep understanding of subjects, acquiring pertinent skills, and personal and intellectual growth facilitated through learning. It is pivotal to delineate that the benchmarks for academic success can vary substantially, influenced by individual personal goals, institutional policies, societal norms, and cultural nuances.

Academic success is a nuanced concept, marrying both tangible and intangible aspects of learning and development. It harbours a dual focus on performance and understanding, cultivating not just a repository of knowledge but a mind that is honed to think, analyze, and innovate. It remains rooted in the fostering of a lifelong passion for learning, encouraging individuals to persistently strive for intellectual and personal growth through educational pursuits.

Examples of Academic Success

Here are some examples of academic success:

- Achieving Top Grades:

The most traditional and widely recognised marker of academic success is the attainment of high grades or marks in exams and assessments. For instance, earning A*s in A-Levels or achieving a First-Class Honours degree at a UK university.

- Research and Publications :

For postgraduate students and researchers, academic success can also be gauged by their contribution to their field. This can be in the form of publishing papers in reputed journals or presenting findings at significant conferences.

- Skills Acquisition :

Successfully learning a new language or gaining proficiency in a laboratory technique can also be viewed as academic success, especially if it significantly augments one’s academic or professional arsenal.

- Participation in Academic Competitions:

Representing one’s school or university in academic contests, such as debates, math olympiads, or science fairs, and achieving commendable positions can be a tangible marker of success.

- Graduation and Further Studies:

Completing a course of study, be it at secondary school or university level, is in itself a monumental marker of academic success. Furthermore, securing admission for further studies in reputed institutions can also be seen as an extension of one’s academic accomplishments.

- Skills Vital for Academic Success:

Achieving academic success is not a result of mere luck or inherent genius. More often than not, it’s a culmination of various skills, both inherent and acquired, that a student harnesses over time. Some of the pivotal skills include:

- Time Management:

With multiple assignments, readings, and other commitments, the ability to manage one’s time effectively is paramount. This doesn’t just involve creating schedules, but also prioritising tasks and setting realistic goals.

- Effective Study Techniques:

Successful students often employ a range of study techniques that enhance their understanding and retention. This might include strategies like the Feynman Technique, active recall, or spaced repetition.

- Critical Thinking:

This skill extends beyond rote learning. It involves analysing information, discerning patterns, questioning assumptions, and arriving at informed conclusions. In the British education system, with its emphasis on essay writing and argumentation, critical thinking is especially valued.

- Communication Skills:

Effective communication is two-fold. Firstly, it’s about understanding information (listening or reading comprehension). Secondly, it’s about articulating ideas clearly, whether through essays, presentations, or discussions.

- Self-motivation and Discipline:

Internal motivation often trumps external pressures. A student who is genuinely passionate about a subject or is intrinsically motivated to excel will find the discipline to study consistently, even when external pressures are absent.

- Adaptability:

The academic landscape is not static. New methodologies, technologies, and theories continually emerge. The ability to adapt, evolve, and remain open to new ideas is a crucial asset in the pursuit of academic excellence.

- Seeking Help When Needed :

Academic success is not synonymous with working in isolation. Recognising when one needs assistance, whether in understanding a topic or dealing with stress, and seeking out resources or support, is a sign of a proactive and successful student.

Skills required for Academic Success

Here are some skills that students might need for academic success:

Proficiency in managing one’s time efficiently allows students to handle a multifaceted array of tasks with composure and efficacy. This skill extends beyond mere scheduling, encompassing the aptitude to prioritise tasks, set realistic goals, and avoid procrastination.

- Research Skills:

At various stages of the academic journey, students are required to undertake research, be it for a simple school project or a university dissertation. Developing the ability to find, analyse, and synthesize information from credible sources is pivotal.

Critical thinking underpins a student’s ability to evaluate information deeply and from multiple angles, enabling them to develop well-informed arguments and solutions. It encourages curiosity, investigation, and reflective judgment.

Being able to express one’s ideas lucidly and effectively, both in written and verbal form, is indispensable. It also includes active listening and reading comprehension, understanding and absorbing the information conveyed through various mediums.

- Note-taking and Summarisation :

Learning the art of jotting down pertinent points and summarising large swathes of information into concise notes can aid in better retention and understanding.

- Study Techniques :

Employing effective study techniques, such as the Feynman Technique, active recall, or spaced repetition, can enhance a student’s learning process, making study sessions more productive.

- Digital Literacy :

In a digitally interconnected world, the ability to navigate and utilise digital tools and platforms efficiently has become increasingly important. It includes a basic understanding of digital safety and etiquette.

Academic success, while often quantified by grades and accolades, is a multi-faceted concept that transcends mere numerical achievements. It’s about the journey of learning, the skills honed, and the knowledge acquired. As the world continues to evolve, the skills and attributes that define academic success might shift. However, the core principle remains unchanged: it’s about striving for excellence, pushing one’s boundaries, and cultivating a lifelong passion for learning.

EuroSchool is committed to helping students achieve academic achievement. The school offers a welcoming learning atmosphere, knowledgeable faculty, and a thorough curriculum with a focus on the student. We give kids the tools they need for academic performance by encouraging critical thinking, effective communication, and discipline. Because of the school’s dedication to individualised instruction and holistic development, children succeed academically and develop into well-rounded persons who are prepared to succeed in their academic endeavors and future endeavours.

Recent Post

- Behaviour & Discipline

- Child Development

- Important Days

- Parent's Zone

- Play & Activities

WHY EUROSCHOOL

- Testimonials

OUR SCHOOLS

- Undri (ICSE)

To Know More, Email or Call us at :

Digital Marketing Services

© Copyright EuroSchool 2024. All Rights Reserved.

Admission Enquiry

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.20(1); Spring 2021

Success for All? A Call to Re-examine How Student Success Is Defined in Higher Education

Maryrose weatherton.

† Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996

Elisabeth E. Schussler

Associated data.

A central focus in science education is to foster the success of students who identify as Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). However, representation and achievement gaps relative to the majority still exist for minoritized students at all levels of science education and beyond. We suggest that majority groups defining the definitions and measures of success may exert “soft power” over minoritized student success. Using a hegemonic and critical race theory lens, we examined five years of research articles in CBE—Life Sciences Education to explore how success was defined and measured and what frameworks guided the definitions of student success. The majority of articles did not explicitly define success, inherently suggesting “everyone knows” its definition. The articles that did define success often used quantitative, academic outcomes like grade point average and exam scores, despite commonly cited frameworks with other metrics. When students defined success, they focused on different aspects, such as gaining leadership skills and building career networks, suggesting a need to integrate student voice into current success definitions. Using these results, we provide suggestions for research, policy, and practice regarding student success. We urge self-reflection and institutional change in our definitions of success, via consideration of a diversity of student voices.

INTRODUCTION

Within the United States, there has been a substantial increase in minority populations over the last 10 years, with the United States projected to be “majority minority” by 2045 ( Vespa et al. , 2018 ). However, this demographic shift has not been mirrored within the scientific disciplines in higher education; while more than 30% of the U.S. population identifies as Black, Indigenous, or other person of color (BIPOC), those groups represent only 21% of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) bachelor’s recipients. Furthermore, BIPOC only represent 13% of STEM doctoral recipients, 11% of the STEM workforce, and 4% of R1 faculty ( National Science Foundation [NSF], 2018 ). The trend is similar within the domain of biological sciences, where BIPOC students represent 12% of earned doctorates and 11% of postdoctoral fellows ( Meyers et al. , 2018 ). These differentials in degree acquisition and faculty representation can cascade down to undergraduate and secondary education students. For example, universities lacking diversity in their faculty ranks may see increased stereotype threat to BIPOC students ( Nouwen and Clycq, 2018 ; Park et al. , 2020 ). This can inhibit students’ development of a sense of belonging ( Good et al. , 2012 ; Hurtado et al. , 2015 ), and negatively affect students’ persistence, well-being, and academic achievement.

Differentials in student success have been discussed for at least a quarter century within education research ( Panos and Astin, 1968 ; Boland et al. , 1978 ; Leman, 1999 ), with countless interventions, theoretical models, and diversity initiatives proposed to increase the success of BIPOC students at all levels STEM education. However, the state of BIPOC representation and persistence would suggest that these initiatives have not succeeded within STEM domains broadly or the field of biological sciences specifically. We argue in this Essay that the assumed definition of “success” and its associated metrics may be one factor hindering the very success of the populations we seek to advance.

What Is Success?

To study and facilitate student success, we must first understand what we mean when we say “success.” As with other broad terms like “interest” ( Rowland et al. , 2019 ), the term “success” has a variety of meanings both within and outside the domain of biology education. Student success can be seen in terms of outcomes , like persistence, increase in self-efficacy, and publication rate. However, these concepts can just as easily be seen as components that facilitate success if it is defined as achieving a particular goal. Furthermore, there can be a stark difference in how faculty and students define success ( Dean, 1998 ; Thompson and Jensen-Ryan, 2018 ), as well as how minoritized students (which we use here to include BIPOC, first-generation, low-socioeconomic status, or other underrepresented groups of students) and their majority counterparts define the term ( Tierney, 1992 ; Goyette and Xie, 1999 ; Oh and Kim, 2016 ; O’Shea and Delahunty, 2018 ). For example, in a study at a public California university, Oh and Kim (2016) found that Korean-American undergraduate students most often defined success as reaching the highest levels of academic achievement, while Mexican-American students most often defined success as going to a 4-year university, surpassing the success of their parents, and helping future students find success ( Oh and Kim, 2016 ). These definitions were further aligned with different support needs and levels of student satisfaction. Thus, the meaning of student success depends on the context as well as who you ask, making a singular, unifying definition largely impossible.

Within biology education, we believe that our current definitions of success may lack the requisite diversity to fully capture the contexts of all students. These definitions inform the metrics used in, and conclusions drawn from, empirical research in the field. These, in turn, inform the policies and practices we advocate for, which ultimately affect student outcomes ( Figure 1 ). These definitions are most often created and maintained by those who hold power in the field (e.g., researchers, faculty members, deans, and other university staff), and rarely include meaningful student input, especially from minoritized populations. If these definitions are not created by and for a diverse population, then there will be cascading impacts on outcomes for those left out of the conversation.

How success is defined impacts almost every facet of the research process, as well as policies and practices, and ultimately affects student outcomes. Researchers’ definitions of success will impact how they choose to measure the construct, which in turn will impact how data are interpreted and thus what recommendations are proposed. These recommendations often have real-world impacts on student outcomes in higher education in the form of changes in policy or practices such as pedagogies or departmental requirements.

We argue that our current limited discourse around the meaning of student success is maintained, in part, by social hierarchies that can be examined through the lens of hegemony and critical race theory, which are described in the next section. These forces unwittingly reinforce and reproduce social hierarchies within our education system that may hinder the success of certain student populations who may not define success in the same way the majority does. Thus, we argue that a critical evaluation of success within higher education is imperative. In this Essay , we hope to start a conversation surrounding what success means, who should define it, and how an expansion of our definitions may help to facilitate the success of all students.

Why Social Hierarchies Are Relevant to the Definition of Success

The ideas presented in this Essay assume an institutional reproduction of social hierarchies and are framed by cultural hegemony and critical race theory. Gramscian hegemony is used to explain the power relations between dominant and minority groups. Specifically, it explains the ways in which dominant groups exert “soft power” over nondominant groups to secure and maintain control within society ( Gramsci, 2000 ; Borg et al. , 2002 ). This is accomplished via manipulation of cultural beliefs, language, values, and norms to establish the dominant group’s worldviews as universal, natural, or common sense. These understood rules of society are often invisible, yet powerful. Alternative perspectives, norms, and values are actively discredited by making them seem counterintuitive or unnecessary ( Grimm, 2015 ). However, these counterhegemonic ideas are often the values and perspectives held by nondominant members of society. Hegemony is thus maintained, because one cannot hold dissenting ideologies and also achieve social mobility, reinforcing existing social hierarches and forcing minority groups to conform to these dominant structures ( Dawson, 1982 ; Gramsci, 2000 ).

We can examine the hegemonic forces underlying student success using ideas from critical race theory (CRT). CRT challenges dominant narratives around race and racism in education and identifies how these narratives are often used to subordinate minoritized groups and maintain white supremacy in the United States ( Solorzano 1997 ; Yosso, 2005 ; Ladson-Billings and Tate, 2006 ). Solorzano and Yosso (2001) point out that racial stereotypes form the basis for the dominant “deficit notions” of BIPOC. For example, a common narrative in the United States is the idea of meritocracy, or “pulling yourself up by the bootstraps,” whereby minoritized groups can find success if they work hard enough ( Collins, 2018 ; McGee, 2020 ). This narrative shifts blame for unequal outcomes (e.g., wage gaps, lowered academic persistence and achievement) to minoritized groups who “don’t work hard enough” or are deficit in some other way, instead of recognizing the structures and institutions that center power with the majority. Within academia, these stereotypes establish a cultural norm that is upheld through differences in expectations, school funding, and punishment between BIPOC and white students (i.e., the school-to-prison pipeline; Solorzano, 1997 ; Barnes and Motz, 2018 ). While seemingly inert, these dominant frameworks translate into policies and structures that harm minoritized students ( Solorzano and Yosso, 2001 ). For example, school tracking systems ( Rosenbaum, 1976 ; Southworth and Mickelson, 2007 ), intelligence testing ( Rose, 1976 ; Solorzano and Yosso, 2001 ), and disparate resource availability ( Tate, 2008 ; Green et al. , 2017 ) have historically been used to maintain social hierarchies by advancing the education of white students while justifying modern-day segregation and deficit notions of BIPOC students ( Solorzano and Yosso, 2001 ; Yosso, 2005 ; McGee, 2020 ). Using a CRT lens allows us to explore how our current definitions and metrics of success do not come from neutral, unbiased, or meritocratic ideals, as is often assumed; instead they have been founded on racist principles. We believe that acknowledging this is an important first step to counter these hegemonic forces and begin to redress the harm that they have done to our students.

Linking hegemony and CRT to the concept of student success, we see that majority power can be maintained in higher education by normalizing a restrictive view of student success (e.g., success as having a high grade point average [GPA]). By focusing on outcomes like productivity and employability, these dominant definitions of success ignore large parts of students’ well-being (e.g., social, cultural, or personal outcomes). This can be harmful to students who hold “alternative” definitions of success by making them feel as if they do not belong within academia ( Hurtado and Carter, 1997 ; Hurtado et al. , 2015 ; Goyette and Xie, 1999 ; Tibbetts et al. , 2016 ). For example, in a study of Latinx undergraduates, Hurtado and Carter (1997) found that students’ GPAs were not significantly associated with their sense of belonging. For these students, participation in nonacademic activities like membership in religious or community organizations was significantly related to students’ sense of belonging ( Hurtado and Carter, 1997 ). This example suggests that a focus on academic metrics versus other measures, such as social participation, may impede the retention of some minoritized students. Many CRT scholars have noted that within the United States education system, BIPOC students are forced to “assimilate” into dominant, Eurocentric paradigms, including those surrounding work ethic, educational values, and definitions of achievement ( Carter and Segura, 1979 ; Solorzano and Yosso, 2001 ; McGee, 2020 ). Minoritized students in academia are thus faced with two choices: integrate into an environment that is misaligned with their identities and actively discredits their beliefs or leave the system ( McGee, 2020 ). When they choose to leave, this attrition of minoritized students from academia not only prevents the field of biology from achieving diversity and equity goals, but it also limits minoritized students’ social mobility and therefore reinforces existing social hierarchies.

Certainly, we do not think that institutions or educators who promote individual, quantitative definitions of success do so as an active choice to suppress minoritized students. Because hegemonic power flourishes when cultural norms are taken for granted, ideas of what makes a student successful are often built into our academic systems and assumed to be universally true. Even when educators and researchers may wish to reimagine how success is defined and evaluated, institutional structures like yearly evaluations based on pass/fail rates or GPA requirements for degree progression may leave little room for them to introduce “alternative” definitions of success, such as positive mental health, internal development, or community-based outcomes. Education researchers, as intellectual leaders in the field, have an opportunity to examine and resist dominant social hierarchies by refusing to support hegemonic structures while voicing counter-hegemonic structures and narratives. Foucault (1997) suggests that the “reproductive power” of cultural hegemony can be resisted and fought against through critical discourse and inviting new voices into the conversation. It is indisputable that academic definitions of success are both relevant and useful within higher education; however, we argue that alternative views of success must be normalized to advance institutional and societal goals. Thus, by listening to new voices (e.g., amplifying minoritized students’ views of success) and considering new definitions of student success, education researchers can take the first step toward changing the system that is preventing students from achieving success equally.

How Biology Education Researchers Define Success

One window into the discourse around student success can be found in the empirical literature investigating student success in higher education. We believe that current definitions of student success are limited, and that this is true across STEM domains. However, we have chosen to support our argument by sampling the literature within the domain in which the authors have the most knowledge—biology education. To sample how success is discussed and defined in the literature specific to this domain, we explored education research articles that discussed student success in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) over the past 5 years. We examined 1) whether and how success was explicitly defined within research articles and 2) how success was measured. We also noted what theoretical frameworks seemed to be shaping research on student success. This literature examination was restricted to biology education and not intended to be comprehensive. Instead, this examination is used as an example of how probing the term “success” can reveal a need for researchers to re-examine their assumptions as well as consider how different metrics and a diversity of student voices may lead to a more complete definition of what it means for students to be successful.

We used a standard literature review methodology to collect these data ( Creswell and Creswell, 2017 ). We searched the online database of LSE on June 14, 2020, using the term “success,” and limited our search to articles published within the last 5 years (2015–2020). This primary search returned 311 articles, which we further narrowed by selecting only research articles (i.e., not reviews, meeting reports, or editorials). After applying this filter, we were left with 248 results.

As we were specifically interested in how success was defined in higher education, we excluded articles that examined student success in K–12 educational settings. Furthermore, we excluded articles that evaluated the success of specific curricular programs (e.g., research examining the success of an intervention aimed at reducing gender bias) as opposed to research on student success, as well as research papers about instructors and faculty, as they did not explicitly study student success. We did not have any exclusion criteria related to subject domain (e.g., math success, physics success, etc.) though most articles published in LSE are related to life sciences education. We also did not exclude any articles on the basis of study time frame or analysis approaches. This left 52 articles related specifically to research on student success in higher education over the last 5 years (see the Supplemental Material for the list of these articles).

The Majority of Articles Discussing Student Success Did Not Explicitly Define the Term

Of the 52 articles, 21 (40%) gave explicit definitions of student success. The other 31 defined student success implicitly through the variables they measured, often equating student success with quantitative student outcomes, such as exam scores and GPA. Of the papers that explicitly defined success, there were four broad categories for how the concept was defined: academic, persistence, career, and social (see definitions in Table 1 ). Academic definitions (e.g., grades, GPA) were the most prevalent in the literature (80%), followed by persistence (e.g., remaining in major) definitions (47%). Career definitions included obtaining a job in STEM (15%). The least common category was social definitions (4%), with only one paper explicitly defining success as it was related to students becoming leaders in their communities. Each article with an explicit definition could be placed in one or more of these four categories.

Categories of explicit definitions of student success represented in the literature sample ( N = 21 articles that defined success explicitly out of 52 total articles)

There Were Many Different Ways to Measure Success, and Most Were Quantitative

Overall, there were 30 distinct measurements of student success in the articles, 13 of which were mentioned more than once. The majority of papers (88%) measured at least one quantitative outcome related to student success; only six papers captured solely qualitative metrics. Of the papers that measured quantitative outcomes, the most common measure of student success was a suite of persistence measurements, followed by exam scores and course grades ( Table 2 ).

Measurements of student success (outcome variables) represented more than once in the literature sample ( N = 52)

Persistence as a measure of student success came up often and in many different variations in the articles. In total, 20 articles (38%) measured student success as some aspect of persistence, attrition, or retention ( Table 2 ). We separated these into five subcategories based on the authors’ description of the outcome variable. Articles that reported “retention” and “persistence” generally were sorted into the first subcategory: “persistence/retention general.” Most often, papers in this subcategory measured persistence or retention in a degree program. Further, “persistence/retention in major” and “persistence/retention in a STEM field” were two different subcategories, with the former being explicitly about changes in students’ declared major, while the latter included postgraduation outcomes, like attaining a career in a STEM field or continuation to a STEM graduate degree. The outcome “intention to persist/remain” was based on student expectations versus actual retention or persistence from a major or course. Finally, there was only one article within the subcategory of “attrition” ( Wilson et al. , 2018 ); this article measured the percent of graduate students that left their programs without an MS or PhD degree over a period of 8 years.

Theories of Student Success Have Changed over Time

As part of the framing for their student success studies, many of the articles cited one or more theories or theoretical frameworks that guided their work. Across the articles we examined, 23 theories were cited, and five were mentioned within multiple papers: self-efficacy, identity, sense of belonging, social cognitive career theory, and social interdependence theory. Theoretical frameworks can influence almost every aspect of a study, from how the research questions are framed, to how concepts are understood and defined, what data are collected, and how the results are interpreted and situated within the broader field ( Anfara and Metz, 2014 ; Creswell and Creswell, 2017 ; Rowland et al. , 2019 ). In studies of student success, the theoretical frameworks that researchers chose likely influenced how they defined success or the success outcomes they hoped to measure. These theoretical frameworks, then, can be vehicles of hegemonic influence that set the standard for how student success is measured and discussed and are thus integral to consider. We will discuss the evolution of the discourse around student success in order to add context to these frameworks and inform our discussion about how to expand our definitions of success.

Although the term “student success” has been discussed in the education literature for more than a century ( Carmichael, 1913 ; Alexander and Woodruff, 1940 ; Brogden and Taylor, 1950 ), most of the theories or frameworks mentioned in the articles we examined were more recent in origin. The five most commonly cited theories in the articles originated within the biology education literature over the past 30 years. However, this empirical research was built on work done in the past, meaning that even these newer conceptions can have old ideas embedded in them that perpetuate racist stereotypes and ideals.

Popularized in the 1950s and 1960s, universal quantitative measures (e.g., ACT, Scholastic Aptitude Test, Graduate Record Examination scores) were some of the first measures of student success ( Capps and Decosta, 1957 ; Kunhart and Olsen, 1959 ). Early theories of student success proposed success as an outcome based on inherent qualities, like personality ( Robertson and Hall, 1964 ). In the 1970s and 1980s, work on student socialization and integration popularized one of the most commonly used metrics of success, persistence ( Table 2 ). Theories during this time built upon previous work by examining how students’ personal characteristics impacted their interactions with their environments, like Tinto’s (1975) theory of student attrition. As the “positive psychology” movement gained traction in the 1990s and 2000s, more modern theories layered “internal development” factors, like motivation and self-regulation, on top of the interactions among personal characteristics and proximal environmental influences to explain student success. For example, social cognitive career theory claims that increasing students’ feelings of self-efficacy and providing them with relevant learning experiences can mediate background and proximal environmental influences on their career decisions and goal attainment ( Lent et al. , 2002 ). This layering introduces new ideas but retains core older ideas about student success.

While new ideas of success push the field forward, much of the discussion is still framed by antiquated, racist notions that undermine these theories’ ability to reflect the experiences of BIPOC students. For example, Binet’s IQ test has been used to justify “genetic determinism” models of minority education equality ( Rose, 1976 ; Solorzano and Yosso, 2001 ). And although the field’s most influential theories are assumed to be broadly applicable, many of them were developed solely on the basis of majority students. For example, Tinto’s influential institutional departure model ( 1975 ) has been critiqued for its exclusive study of “traditional” students (i.e., white, upper-class students) at “traditional” universities (i.e., primarily white, residential, 4-year institutions; Astin, 1985 ; Attinasi, 1989 ; Tierney, 1992 ; Tinto, 1993 ). These limited populations bounded the results drawn from the theory. This has led, for example, to the problematic conclusion that students must detach from their previous communities in order to find success in higher education. Indeed, the opposite has been found for minority and first-generation students, many of whom draw strengths from their connection to their home communities and cultures ( Muñoz and Maldonado, 2012 ; Yao, 2015 ; Burt et al. , 2019 ).

The use of majority students as the foundation for the theories central to the ideas underlying student success is not only problematic, but harmful to minoritized students. When historically underrepresented students do not meet the standards of success established by the theories (e.g., higher attrition rates, lower course grades, etc.) it is assumed that the deficiencies are on the part of the students, and not the theory. As previously mentioned, this “deficit notion” of BIPOC students prevents equitable outcomes between BIPOC and white students. It also forces minoritized students to choose whether to conform to the majority standards of success or live within a system that does not value what they consider to be successful.

Despite the expansion of our theoretical understanding of student success over the past century, many of our definitions and metrics of success have been stubbornly unchanging. We acknowledge that the practicality and ease of quantitative metrics may be one reason why they are so prominent when measuring student success. It takes much less time to gather the course grades of each student in an introductory biology class than it does to collect interview data about their perspectives on success in the course, for example. Furthermore, latent constructs like student well-being or identity are more difficult to measure compared with academic metrics like GPA, as the former are made up of multiple, diverging indicators, and alternative ways to measure these constructs may not yet have been developed and validated for wider usage. Of course, quantitative metrics can have predictive value and can be excellent tools to answer many research questions. However, we argue that measuring quantitative outcomes is not a panacea for understanding how students achieve success in academia. Thus, we argue that, without addressing the ideas that underlie our notions of success, the field will continue to struggle to address the needs and facilitate the success of all of our students.

Who Gets to Define Student Success?

Of the 52 articles in LSE that discussed student success over the past five years, only one article captured students’ own definitions of success, suggesting a paucity of research in this area. This presents an issue if students have different definitions of success than those who determine the field’s definitions, like researchers and institutional decision makers. Indeed, Thompson and Jensen-Ryan (2018) found that undergraduate students expressed definitions of success that included academic outcomes like graduation as well as emotional outcomes, such as not getting discouraged and increasing their self-efficacy and self-confidence. Many students from historically underrepresented backgrounds (e.g., BIPOC, low-socioeconomic status, first-generation students) reject traditional definitions of success. For example, O’Shea and Delahunty (2018) found three themes of success that emerged from interviews with first-generation undergraduates: success as a form of validation, success as defying the odds, and success as positive feelings about one’s trajectory. Interestingly, many of the students interviewed had very clear ideas of what success was not , including obtaining high grades or passing exams ( O’Shea and Delahunty, 2018 ).

Considering these examples of how students’ and researchers’ perspectives on success can differ, we ask why student voices are so rare in the literature on student success. One explanation goes back to the idea of hegemonic power, wherein members of the majority impose their worldview as cultural “common sense” ( Boggs, 1976 , p. 39). Within academia, hegemonically imposed worldviews can present themselves via the belief that definitions of certain terms are homogeneous and that explicitly defining terms like “success,” “persistence,” and “interest” is not necessary. Indeed, our examination of the literature on student success found that success was only explicitly defined in 40% of the articles we examined. Even when success is defined, researchers and other institutional stakeholders may experience difficulty thinking beyond traditional definitions, as they often realized their positions via traditional success measures (e.g., academic success). Thus, the problem becomes apparent—if most researchers define success in similar ways, and these definitions are validated by achieving intended career outcomes, then these definitions are taken for granted and seen as common sense. Therefore, researchers may not see the need to gather student perceptions of any concept whose definition seem so inherent.

In this way, hegemonic influence is hidden within everyday facets of academia, like the language we use to describe and define concepts. However, a critical examination of the discourse surrounding these concepts can reveal a startling lack of ideological diversity. We argue that the hegemonic framing of embedded discourse prevents the field from moving forward toward more inclusive definitions and metrics. To resist this framing, we must collectively examine and make concrete changes to many of the aspects we have discussed here: how success is defined and measured and whose success we are concerned with. As a community of researchers, we have the collective power to expand our own and our institutions’ discourse in order to validate and facilitate all students’ definitions of success. To that end, we present recommendations in the realms of research, policy, and practice that aim to amplify minoritized student voices, encourage deep self-reflection, and bring about equitable institutional change.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The purpose of this Essay was to examine success through a hegemonic and CRT lens to inform a collective discussion about how our current perspectives on student success may be contributing to unequal attainment of success. Despite a concentrated effort over the past 25 years to increase BIPOC “success” in STEM domains, gaps between BIPOC students and their majority counterparts still exist at all levels of STEM education and beyond ( NSF, 2018 ; Meyers et al. , 2018 ). Although the field’s ideas and theories of student success have evolved and gained more nuance over the past 70 years, our definitions and measures still fall short of being fully inclusive. Our limited examination suggests that current definitions and metrics of student success are mostly academic and quantitative and are most often defined by institutional-level stakeholders, such as researchers. Although these theories were developed via research directed at students, there is a paucity of literature that directly asks students their views on success in higher education. Here, we propose recommendations for individual researchers to more explicitly consider success and center student voice in their empirical work. We then provide recommendations for the community as a whole within the areas of research, policy, and practice.

Recommendations for Individual Researchers

To encourage researchers to more critically examine their potential role in the reproduction of social hierarchies in academia, we recommend that they consider their own definitions of student success and how these definitions influence their empirical work. Furthermore, we encourage researchers to consider what definitions of success are highlighted within their research and how they can amplify diverse perspectives and voices within that research. Explicitly considering what perspectives of success they intend to use before beginning their projects will allow researchers to clearly ground their work and accurately describe what they intend to study, which in turn will lead to clarity in definitions, proposed metrics, and interpretation of results.

To foster these reflections, we model from Rowland et al. (2019) the presentation of guidelines and associated guiding questions for researchers to use as they begin projects investigating student success in higher education:

- Before beginning their research, researchers must self-reflect on the biases, hegemonic frames, and societal norms that they have internalized simply as members of society. Much like the qualitative practice of bracketing, this process will not rid researchers of any biases, but makes them visible, so researchers can reflect on how these biases may shape their interpretations ( Creswell and Miller, 2000 ). For resources to guide self-reflection and examination of internal biases, see Gullo et al. (2018) , Killpack and Melón (2016) , Project Implicit (2011) , and Racial Equity Tools (2020) .

- i. Does my funding source require institutionally relevant data, like student retention or GPA? If so, does my definition align with these metrics? Do I need to add a second definition if I am collecting other metrics?

- ii. How diverse is my intended study population? Are there definitions of success that may more closely align with the views of my intended population?*

- iii. How might my study accurately capture the perspectives of minoritized students, as opposed to invoking “safe multiculturalism” (i.e., an unchallenging, stereotypical, or tokenized view of a culture)? For more information on safe multiculturalism, see May and Sleeter (2010) and Yancy (2016) .

- iv. Do my intended research questions and theoretical frameworks align with the definition(s) of student success I am considering?

- i. Based on my definition, how many measures of success do I need to use?

- ii. Should the definition of success be captured using quantitative or qualitative metrics? If I can use both, is one more appropriate given my intended population,* study context, and time constraints?

- iii. Am I sure that students define success in the way I am intending to measure it?*

- i. Have I chosen this definition of success over others simply because its associated metrics are easy to measure?

- ii. Have I explicitly defined success in any communications about my project?

- iii. Have I sufficiently articulated a rationale for my definition and measures?

- iv. How might the definition of success used in my project be a potential limitation of the study? Have I acknowledged that as part of the study?

*If the answers to some of these questions are unknown, researchers may want to consider a pilot study or a qualitative inquiry into these students’ definitions of success.

We hope the use of these guidelines and associated questions will help researchers appropriately conceptualize success in each study they undertake and encourage researchers to consider how to capture diverse voices and perspectives within their research.

Recommendations for Research, Policy, and Practice

The following section focuses on actions the community can take to disrupt the current thinking about student success in order to reframe it for all students. To reflect the full diversity within STEM, and in consideration of the lack of student voice in the current literature, we suggest a need to truly listen to student perspectives on success at all levels. Lack of student voice is widespread across many domains; indeed, this issue has garnered the attention of the United Nations, which in 2009 proposed “General Comment No. 12—The Right of the Child to be Heard” ( UN, 2009 ). In 2002, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) documented its concern that “in education, schoolchildren are not systematically consulted in matters that affect them” ( UN, 2002 ). We suggest that similar issues are present in higher education, even though the majority of our students are considered adults.

In 2007, Lundy proposed a model to conceptualize article 12 of the UNCRC, and we are adapting it here to guide discussions about how to highlight student voice in research on student success and bring meaningful change within the realms of policy and practice ( Figure 2 ). Article 12 delineates two key rights: 1) the right to be heard and 2) the right to have one’s views given due weight ( Lundy, 2007 ). To successfully implement article 12, Lundy proposed that four elements must be considered: space, voice, audience, and influence. The first two elements, space and voice, relate to students’ rights to be heard. The next two elements, audience and influence, relate to students’ rights to have their views given due weight. We propose that the first two elements of Lundy’s model can be used to inform recommendations for research, and the latter two elements can be used to inform recommendations for research, policy, and practice.

This figure highlights four key elements from Lundy’s model, two relating to one’s right to express a view—space and voice—and two relating to one’s right to have their views given due weight—audience and influence. These rights are highly interrelated, and when examined in an academic context, lead to an iterative process for working with students to bring equity to the domains of policy, practice, and research.

Students’ Rights to Be Heard—Recommendations for Research.

A prerequisite for meaningful engagement with students requires the recognition that their opinions are necessary and valid. In regard to discussions of student success, this means we must create space in our discourse where alternative definitions of success are not only allowed but are honored as equally valuable. We believe that the process of making this space can start with this Essay and subsequent conversations. This space will allow the field to begin the process of examining the current hegemonic structures that dominate academia and work to dismantle them.

Student voice is critical to this process. This can be accomplished either informally, through conversations between students and mentors; or formally, through qualitative research regarding how students define success. Involving students in the research process is an empowering way to amplify student voice in our discussion of student success. When applicable, we suggest that researchers employ a community-based participatory research approach, a research strategy that equitably involves community members and researchers in a way that seeks to validate community members’ expertise and empowers non-researchers by sharing the decision-making process (see Minkler and Wallerstein, 2011 ). We also point out that the need to listen to students includes both undergraduate and graduate students. Research on graduate student success is even more limited than for undergraduates, and given the high attrition of graduate students from STEM degree programs ( Chen, 2013 ; Sowell et al. , 2015 ), it is important to also capture their unique perspectives. These conversations can add critical, new perspectives needed by researchers and institutional stakeholders to steer the field in a new direction.

Students’ Rights to Have Their Views Given Due Weight—Recommendations for Research and Policy.

Lundy (2007) recognized that making space and gathering student voice do not necessarily mean that student perspectives will be appropriately heard or acted upon. Indeed, ensuring students maintain their rights is often difficult, especially when their views challenge the dominant thinking, are expensive to enact, or cause controversy ( Lundy, 2007 ). It is important that we are attentive to the latter two elements in Lundy’s model—audience and influence—as merely gathering student perspectives without enacting change (i.e., tokenizing student voice) will not combat systemic issues and may, in fact, be counterproductive ( Alderson, 2000 ).

Students’ perspectives must be presented to the appropriate audiences in order for them to have any influence over research, policy, or practice. Thus, stakeholders at all levels of academic institutions must be exposed to these voices. This can be accomplished broadly through publication and presentation of work that foregrounds student voice and locally through initiatives that present students’ opinions to provosts, deans, department heads, faculty, and other university leadership staff to inform new policies. The UNCRC has warned that “appearing to ‘listen’ to children is relatively unchallenging; giving due weight to their views requires real change” ( UN, 2003 , para. 12).