A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law

- Political Culture

- Religion in America

- Rights and Liberties

No study questions

“Ignorance and inconsideration are the two great causes of the ruin of mankind.” This is an observation of Dr. Tillotson, with relation to the interest of his fellow men in a future and immortal state. But it is of equal truth and importance if applied to the happiness of men in society, on this side the grave. In the earliest ages of the world, absolute monarchy seems to have been the universal form of government. Kings, and a few of their great counselors and captains, exercised a cruel tyranny over the people, who held a rank in the scale of intelligence, in those days, but little higher than the camels and elephants that carried them and their engines to war.

By what causes it was brought to pass, that the people in the middle ages became more intelligent in general, would not, perhaps, be possible in these days to discover. But the fact is certain; and wherever a general knowledge and sensibility have prevailed among the people, arbitrary government and every kind of oppression have lessened and disappeared in proportion. Man has certainly an exalted soul; and the same principle in human nature, — that aspiring, noble principle founded in benevolence, and cherished by knowledge; I mean the love of power, which has been so often the cause of slavery, — has, whenever freedom has existed, been the cause of freedom. If it is this principle that has always prompted the princes and nobles of the earth, by every species of fraud and violence to shake off all the limitations of their power, it is the same that has always stimulated the common people to aspire at independency, and to endeavor at confining the power of the great within the limits of equity and reason.

The poor people, it is true, have been much less successful than the great. They have seldom found either leisure or opportunity to form a union and exert their strength; ignorant as they were of arts and letters, they have seldom been able to frame and support a regular opposition. This, however, has been known by the great to be the temper of mankind; and they have accordingly labored, in all ages, to wrest from the populace, as they are contemptuously called, the knowledge of their rights and wrongs, and the power to assert the former or redress the latter. I say RIGHTS, for such they have, undoubtedly, antecedent to all earthly government, — Rights, that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws — Rights, derived from the great Legislator of the universe.

Since the promulgation of Christianity, the two greatest systems of tyranny that have sprung from this original, are the canon and the feudal law. The desire of dominion, that great principle by which we have attempted to account for so much good and so much evil, is, when properly restrained, a very useful and noble movement in the human mind. But when such restraints are taken off, it becomes an encroaching, grasping, restless, and ungovernable power. Numberless have been the systems of iniquity contrived by the great for the gratification of this passion in themselves; but in none of them were they ever more successful than in the invention and establishment of the canon and the feudal law.

By the former of these, the most refined, sublime, extensive, and astonishing constitution of policy that ever was conceived by the mind of man was framed by the Romish clergy for the aggrandizement of their own order. All the epithets I have here given to the Romish policy are just, and will be allowed to be so when it is considered, that they even persuaded mankind to believe, faithfully and undoubtingly, that God Almighty had entrusted them with the keys of heaven, whose gates they might open and close at pleasure; with a power of dispensation over all the rules and obligations of morality; with authority to license all sorts of sins and crimes; with a power of deposing princes and absolving subjects from allegiance; with a power of procuring or withholding the rain of heaven and the beams of the sun; with the management of earthquakes, pestilence, and famine; nay, with the mysterious, awful, incomprehensible power of creating out of bread and wine the flesh and blood of God himself. All these opinions they were enabled to spread and rivet among the people by reducing their minds to a state of sordid ignorance and staring timidity, and by infusing into them a religious horror of letters and knowledge. Thus was human nature chained fast for ages in a cruel, shameful, and deplorable servitude to him, and his subordinate tyrants, who, it was foretold, would exalt himself above all that was called God, and that was worshipped.

In the latter we find another system, similar in many respects to the former; 1 which, although it was originally formed, perhaps, for the necessary defense of a barbarous people against the inroads and invasions of her neighboring nations, yet for the same purposes of tyranny, cruelty, and lust, which had dictated the canon law, it was soon adopted by almost all the princes of Europe, and wrought into the constitutions of their government. It was originally a code of laws for a vast army in a perpetual encampment. The general was invested with the sovereign propriety of all the lands within the territory. Of him, as his servants and vassals, the first rank of his great officers held the lands; and in the same manner the other subordinate officers held of them; and all ranks and degrees held their lands by a variety of duties and services, all tending to bind the chains the faster on every order of mankind. In this manner the common people were held together in herds and clans in a state of servile dependence on their lords, bound, even by the tenure of their lands, to follow them, whenever they commanded, to their wars, and in a state of total ignorance of every thing divine and human, excepting the use of arms and the culture of their lands.

But another event still more calamitous to human liberty, was a wicked confederacy between the two systems of tyranny above described. It seems to have been even stipulated between them, that the temporal grandees should contribute every thing in their power to maintain the ascendancy of the priesthood, and that the spiritual grandees in their turn, should employ their ascendancy over the consciences of the people, in impressing on their minds a blind, implicit obedience to civil magistracy.

Thus, as long as this confederacy lasted, and the people were held in ignorance, liberty, and with her, knowledge and virtue too, seem to have deserted the earth, and one age of darkness succeeded another, till God in his benign providence raised up the champions who began and conducted the Reformation. From the time of the Reformation to the first settlement of America, knowledge gradually spread in Europe, but especially in England; and in proportion as that increased and spread among the people, ecclesiastical and civil tyranny, which I use as synonymous expressions for the canon and feudal laws, seem to have lost their strength and weight. The people grew more and more sensible of the wrong that was done them by these systems, more and more impatient under it, and determined at all hazards to rid themselves of it; till at last, under the execrable race of the Stuarts, the struggle between the people and the confederacy aforesaid of temporal and spiritual tyranny, became formidable, violent, and bloody.

It was this great struggle that peopled America. It was not religion alone, as is commonly supposed; but it was a love of universal liberty, and a hatred, a dread, a horror, of the infernal confederacy before described, that projected, conducted, and accomplished the settlement of America.

It was a resolution formed by a sensible people, — I mean the Puritans, — almost in despair. They had become intelligent in general, and many of them learned. For this fact, I have the testimony of Archbishop King himself, who observed of that people, that they were more intelligent and better read than even the members of the church, whom he censures warmly for that reason. This people had been so vexed and tortured by the powers of those days, for no other crime than their knowledge and their freedom of inquiry and examination, and they had so much reason to despair of deliverance from those miseries on that side the ocean, that they at last resolved to fly to the wilderness for refuge from the temporal and spiritual principalities and powers, and plagues and scourges of their native country.

After their arrival here, they began their settlement, and formed their plan, both of ecclesiastical and civil government, in direct opposition to the canon and the feudal systems. The leading men among them, both of the clergy and the laity, were men of sense and learning. To many of them the historians, orators, poets, and philosophers of Greece and Rome were quite familiar; and some of them have left libraries that are still in being, consisting chiefly of volumes in which the wisdom of the most enlightened ages and nations is deposited, — written, however, in languages which their great-grandsons, though educated in European universities, can scarcely read. 2

Thus accomplished were many of the first planters in these colonies. It may be thought polite and fashionable by many modern fine gentlemen, perhaps, to deride the characters of these persons, as enthusiastical, superstitious, and republican. But such ridicule is founded in nothing but foppery and affectation, and is grossly injurious and false. Religious to some degree of enthusiasm it may be admitted they were; but this can be no peculiar derogation from their character; because it was at that time almost the universal character not only of England, but of Christendom. Had this, however, been otherwise, their enthusiasm, considering the principles on which it was founded and the ends to which it was directed, far from being a reproach to them, was greatly to their honor; for I believe it will be found universally true, that no great enterprise for the honor or happiness of mankind was ever achieved without a large mixture of that noble infirmity. Whatever imperfections may be justly ascribed to them, which, however, are as few as any mortals have discovered, their judgment in framing their policy was founded in wise, humane, and benevolent principles. It was founded in revelation and in reason too. It was consistent with the principles of the best and greatest and wisest legislators of antiquity. Tyranny in every form, shape, and appearance was their disdain and abhorrence; no fear of punishment, nor even of death itself in exquisite tortures, had been sufficient to conquer that steady, manly, pertinacious spirit with which they had opposed the tyrants of those days in church and state. They were very far from being enemies to monarchy; and they knew as well as any men, the just regard and honor that is due to the character of a dispenser of the mysteries of the gospel of grace. But they saw clearly, that popular powers must be placed as a guard, a control, a balance, to the powers of the monarch and the priest, in every government, or else it would soon become the man of sin, the whore of Babylon, the mystery of iniquity, a great and detestable system of fraud, violence, and usurpation. Their greatest concern seems to have been to establish a government of the church more consistent with the Scriptures, and a government of the state more agreeable to the dignity of human nature, than any they had seen in Europe, and to transmit such a government down to their posterity, with the means of securing and preserving it forever. To render the popular power in their new government as great and wise as their principles of theory, that is, as human nature and the Christian religion require it should be, they endeavored to remove from it as many of the feudal inequalities and dependencies as could be spared, consistently with the preservation of a mild limited monarchy. And in this they discovered the depth of their wisdom and the warmth of their friendship to human nature. But the first place is due to religion. They saw clearly, that of all the nonsense and delusion which had ever passed through the mind of man, none had ever been more extravagant than the notions of absolutions, indelible characters, uninterrupted successions, and the rest of those fantastical ideas, derived from the canon law, which had thrown such a glare of mystery, sanctity, reverence, and right reverend eminence and holiness, around the idea of a priest, as no mortal could deserve, and as always must, from the constitution of human nature, be dangerous in society. For this reason, they demolished the whole system of diocesan episcopacy; and, deriding, as all reasonable and impartial men must do, the ridiculous fancies of sanctified effluvia from Episcopal fingers, they established sacerdotal ordination on the foundation of the Bible and common sense. This conduct at once imposed an obligation on the whole body of the clergy to industry, virtue, piety, and learning, and rendered that whole body infinitely more independent on the civil powers, in all respects, than they could be where they were formed into a scale of subordination, from a pope down to priests and friars and confessors, — necessarily and essentially a sordid, stupid, and wretched herd, — or than they could be in any other country, where an archbishop held the place of a universal bishop, and the vicars and curates that of the ignorant, dependent, miserable rabble aforesaid, — and infinitely more sensible and learned than they could be in either. This subject has been seen in the same light by many illustrious patriots, who have lived in America since the days of our forefathers, and who have adored their memory for the same reason. And methinks there has not appeared in New England a stronger veneration for their memory, a more penetrating insight into the grounds and principles and spirit of their policy, nor a more earnest desire of perpetuating the blessings of it to posterity, than that fine institution of the late Chief Justice Dudley, of a lecture against popery, and on the validity of Presbyterian ordination. This was certainly intended by that wise and excellent man, as an eternal memento of the wisdom and goodness of the very principles that settled America. But I must again return to the feudal law. The adventurers so often mentioned, had an utter contempt of all that dark ribaldry of hereditary, indefeasible right, — the Lord’s anointed, — and the divine, miraculous original of government, with which the priesthood had enveloped the feudal monarch in clouds and mysteries, and from whence they had deduced the most mischievous of all doctrines, that of passive obedience and non-resistance. They knew that government was a plain, simple, intelligible thing, founded in nature and reason, and quite comprehensible by common sense. They detested all the base services and servile dependencies of the feudal system. They knew that no such unworthy dependencies took place in the ancient seats of liberty, the republics of Greece and Rome; and they thought all such slavish subordinations were equally inconsistent with the constitution of human nature and that religious liberty with which Jesus had made them free. This was certainly the opinion they had formed; and they were far from being singular or extravagant in thinking so. Many celebrated modern writers in Europe have espoused the same sentiments. Lord Kames, a Scottish writer of great reputation, whose authority in this case ought to have the more weight as his countrymen have not the most worthy ideas of liberty, speaking of the feudal law, says, –“A constitution so contradictory to all the principles which govern mankind can never be brought about, one should imagine, but by foreign conquest or native usurpations.” Rousseau, speaking of the same system, calls it, — “That most iniquitous and absurd form of government by which human nature was so shamefully degraded.” It would be easy to multiply authorities, but it must be needless; because, as the original of this form of government was among savages, as the spirit, of it is military and despotic, every writer who would allow the people to have any right to life or property or freedom more than the beasts of the field, and who was not hired or enlisted under arbitrary, lawless power, has been always willing to admit the feudal system to be inconsistent with liberty and the rights of mankind.

To have holden their lands allodially, or for every man to have been the sovereign lord and proprietor of the ground he occupied, would have constituted a government too nearly like a commonwealth. They were contented, therefore, to hold their lands of their king, as their sovereign lord; and to him they were willing to render homage, but to no mesne or subordinate lords; nor were they willing to submit to any of the baser services. In all this they were so strenuous, that they have even transmitted to their posterity a very general contempt and detestation of holdings by quitrents, as they have also a hereditary ardor for liberty and thirst for knowledge.

They were convinced, by their knowledge of human nature, derived from history and their own experience, that nothing could preserve their posterity from the encroachments of the two systems of tyranny, in opposition to which, as has been observed already, they erected their government in church and state, but knowledge diffused generally through the whole body of the people. Their civil and religious principles, therefore, conspired to prompt them to use every measure and take every precaution in their power to propagate and perpetuate knowledge. For this purpose they laid very early the foundations of colleges, and invested them with ample privileges and emoluments; and it is remarkable that they have left among their posterity so universal an affection and veneration for those seminaries, and for liberal education, that the meanest of the people contribute cheerfully to the support and maintenance of them every year, and that nothing is more generally popular than projections for the honor, reputation, and advantage of those seats of learning. But the wisdom and benevolence of our fathers rested not here. They made an early provision by law, that every town consisting of so many families, should be always furnished with a grammar school. They made it a crime for such a town to be destitute of a grammar schoolmaster for a few months, and subjected it to a heavy penalty. So that the education of all ranks of people was made the care and expense of the public, in a manner that I believe has been unknown to any other people ancient or modern.

The consequences of these establishments we see and feel every day. A native of America who cannot read and write is as rare an appearance as a Jacobite or a Roman Catholic, that is, as rare as a comet or an earthquake. It has been observed, that we are all of us lawyers, divines, politicians, and philosophers. And I have good authorities to say, that all candid foreigners who have passed through this country, and conversed freely with all sorts of people here, will allow, that they have never seen so much knowledge and civility among the common people in any part of the world. It is true, there has been among us a party for some years, consisting chiefly not of the descendants of the first settlers of this country, but of high churchmen and high statesmen imported since, who affect to censure this provision for the education of our youth as a needless expense, and an imposition upon the rich in favor of the poor, and as an institution productive of idleness and vain speculation among the people, whose time and attention, it is said, ought to be devoted to labor, and not to public affairs, or to examination into the conduct of their superiors. And certain officers of the crown, and certain other missionaries of ignorance, foppery, servility, and slavery, have been most inclined to countenance and increase the same party. Be it remembered, however, that liberty must at all hazards be supported. We have a right to it, derived from our Maker. But if we had not, our fathers have earned and bought it for us, at the expense of their ease, their estates, their pleasure, and their blood. And liberty cannot be preserved without a general knowledge among the people, who have a right, from the frame of their nature, to knowledge, as their great Creator, who does nothing in vain, has given them understandings, and a desire to know; but besides this, they have a right, an indisputable, unalienable, indefeasible, divine right to that most dreaded and envied kind of knowledge, I mean, of the characters and conduct of their rulers. Rulers are no more than attorneys, agents, and trustees for the people; and if the cause, the interest and trust, is insidiously betrayed, or wantonly trifled away, the people have a right to revoke the authority that they themselves have deputed, and to constitute abler and better agents, attorneys, and trustees. And the preservation of the means of knowledge among the lowest ranks, is of more importance to the public than all the property of all the rich men in the country. It is even of more consequence to the rich themselves, and to their posterity. The only question is, whether it is a public emolument; and if it is, the rich ought undoubtedly to contribute, in the same proportion as to all other public burdens, — that is, in proportion to their wealth, which is secured by public expenses. But none of the means of information are more sacred, or have been cherished with more tenderness and care by the settlers of America, than the press. Care has been taken that the art of printing should be encouraged, and that it should be easy and cheap and safe for any person to communicate his thoughts to the public. And you, Messieurs printers, 3 whatever the tyrants of the earth may say of your paper, have done important service to your country by your readiness and freedom in publishing the speculations of the curious. The stale, impudent insinuations of slander and sedition, with which the gormandizers of power have endeavored to discredit your paper, are so much the more to your honor; for the jaws of power are always opened to devour, and her arm is always stretched out, if possible, to destroy the freedom of thinking, speaking, and writing. And if the public interest, liberty, and happiness have been in danger from the ambition or avarice of any great man, whatever may be his politeness, address, learning, ingenuity, and, in other respects, integrity and humanity, you have done yourselves honor and your country service by publishing and pointing out that avarice and ambition. These vices are so much the more dangerous and pernicious for the virtues with which they may be accompanied in the same character, and with so much the more watchful jealousy to be guarded against.

“Curse on such virtues, they’ve undone their country.”

Be not intimidated, therefore, by any terrors, from publishing with the utmost freedom, whatever can be warranted by the laws of your country; nor suffer yourselves to be wheedled out of your liberty by any pretences of politeness, delicacy, or decency. These, as they are often used, are but three different names for hypocrisy, chicanery, and cowardice. Much less, I presume, will you be discouraged by any pretences that malignants on this side the water will represent your paper as factious and seditious, or that the great on the other side the water will take offence at them. This dread of representation has had for a long time, in this province, effects very similar to what the physicians call a hydrophobia, or dread of water. It has made us delirious; and we have rushed headlong into the water, till we are almost drowned, out of simple or phrensical fear of it. Believe me, the character of this country has suffered more in Britain by the pusillanimity with which we have borne many insults and indignities from the creatures of power at home and the creatures of those creatures here, than it ever did or ever will by the freedom and spirit that has been or will be discovered in writing or action. Believe me, my countrymen, they have imbibed an opinion on the other side the water, that we are an ignorant, a timid, and a stupid people; nay, their tools on this side have often the impudence to dispute your bravery. But I hope in God the time is near at hand when they will be fully convinced of your understanding, integrity and courage. But can any thing be more ridiculous, were it not too provoking to be laughed at, than to pretend that offence should be taken at home for writings here? Pray, let them look at home. Is not the human understanding exhausted there? Are not reason, imagination, wit, passion, senses, and all, tortured to find out satire and invective against the characters of the vile and futile fellows who sometimes get into place and power? The most exceptionable paper that ever I saw here is perfect prudence and modesty in comparison of multitudes of their applauded writings. Yet the high regard they have for the freedom of the press, indulges all. I must and will repeat it, your paper deserves the patronage of every friend to his country. And whether the defamers of it are arrayed in robes of scarlet or sable, whether they lurk and skulk in an insurance office, whether they assume the venerable character of a priest, the sly one of a scrivener, or the dirty, infamous, abandoned one of an informer, they are all the creatures and tools of the lust of domination.

The true source of our sufferings has been our timidity.

We have been afraid to think. We have felt a reluctance to examining into the grounds of our privileges, and the extent in which we have an indisputable right to demand them, against all the power and authority on earth. And many who have not scrupled to examine for themselves, have yet for certain prudent reasons been cautious and diffident of declaring the result of their inquiries.

The cause of this timidity is perhaps hereditary, and to be traced back in history as far as the cruel treatment the first settlers of this country received, before their embarkation for America, from the government at home. Everybody knows how dangerous it was to speak or write in favor of any thing, in those days, but the triumphant system of religion and politics. And our fathers were particularly the objects of the persecutions and proscriptions of the times. It is not unlikely, therefore, that although they were inflexibly steady in refusing their positive assent to any thing against their principles, they might have contracted habits of reserve, and a cautious diffidence of asserting their opinions publicly. These habits they probably brought with them to America, and have transmitted down to us. Or we may possibly account for this appearance by the great affection and veneration Americans have always entertained for the country from whence they sprang; or by the quiet temper for which they have been remarkable, no country having been less disposed to discontent than this; or by a sense they have that it is their duty to acquiesce under the administration of government, even when in many smaller matters grievous to them, and until the essentials of the great compact are destroyed or invaded. These peculiar causes might operate upon them; but without these, we all know that human nature itself, from indolence, modesty, humanity, or fear, has always too much reluctance to a manly assertion of its rights. Hence, perhaps, it has happened, that nine tenths of the species are groaning and gasping in misery and servitude.

But whatever the cause has been, the fact is certain, we have been excessively cautious of giving offence by complaining of grievances. And it is as certain, that American governors, and their friends, and all the crown officers, have availed themselves of this disposition in the people. They have prevailed on us to consent to many things which were grossly injurious to us, and to surrender many others, with voluntary tameness, to which we had the clearest right. Have we not been treated, formerly, with abominable insolence, by officers of the navy? I mean no insinuation against any gentleman now onthis station, having heard no complaint of any one of them to his dishonor. Have not some generals from England treated us like servants, nay, more like slaves than like Britons? Have we not been under the most ignominious contribution, the most abject submission, the most supercilious insults, of some custom-house officers? Have we not been trifled with, brow-beaten, and trampled on, by former governors, in a manner which no king of England since James the Second has dared to indulge towards his subjects? Have we not raised up one family, in them placed an unlimited confidence, and been soothed and flattered and intimidated by their influence, into a great part of this infamous tameness and submission? “These are serious and alarming questions, and deserve a dispassionate consideration.”

This disposition has been the great wheel and the mainspring in the American machine of court politics. We have been told that “the word rights is an offensive expression;” “that the king, his ministry, and parliament, will not endure to hear Americans talk of their rights;” “that Britain is the mother and we the children, that a filial duty and submission is due from us to her,” and that “we ought to doubt our own judgment, and presume that she is right, even when she seems to us to shake the foundations of government;” that “Britain is immensely rich and great and powerful, has fleets and armies at her command which have been the dread and terror of the universe, and that she will force her own judgment into execution, right or wrong.” But let me entreat you, sir, to pause. Do you consider yourself as a missionary of loyalty or of rebellion? Are you not representing your king, his ministry, and parliament, as tyrants, — imperious, unrelenting tyrants, — by such reasoning as this? Is not this representing your most gracious sovereign as endeavoring to destroy the foundations of his own throne? Are you not representing every member of parliament as renouncing the transactions at Running Mede, (the meadow, near Windsor, where Magna Charta was signed;) and as repealing in effect the bill of rights, when the Lords and Commons asserted and vindicated the rights of the people and their own rights, and insisted on the king’s assent to that assertion and vindication? Do you not represent them as forgetting that the prince of Orange was created King William, by the people, on purpose that their rights might be eternal and inviolable? Is there not something extremely fallacious in the common-place images of mother country and children colonies? Are we the children of Great Britain any more than the cities of London, Exeter, and Bath? Are we not brethren and fellow subjects with those in Britain, only under a somewhat different method of legislation, and a totally different method of taxation? But admitting we are children, have not children a right to complain when their parents are attempting to break their limbs, to administer poison, or to sell them to enemies for slaves? Let me entreat you to consider, will the mother be pleased when you represent her as deaf to the cries of her children, — when you compare her to the infamous miscreant who lately stood on the gallows for starving her child, — when you resemble her to Lady Macbeth in Shakespeare, (I cannot think of it without horror,) who

“Had given suck, and knew How tender ’t was to love the babe that milked her,”

but yet, who could “Even while ’t was smiling in her face, Have plucked her nipple from the boneless gums, And dashed the brains out.”

Let us banish for ever from our minds, my countrymen, all such unworthy ideas of the king, his ministry, and parliament. Let us not suppose that all are become luxurious, effeminate, and unreasonable, on the other side the water, as many designing persons would insinuate. Let us presume, what is in fact true, that the spirit of liberty is as ardent as ever among the body of the nation, though a few individuals may be corrupted. Let us take it for granted, that the same great spirit which once gave Cesar so warm a reception, which denounced hostilities against John till Magna Charta was signed, which severed the head of Charles the First from his body, and drove James the Second from his kingdom, the same great spirit (may heaven preserve it till the earth shall be no more) which first seated the great grandfather of his present most gracious majesty on the throne of Britain, — is still alive and active and warm in England; and that the same spirit in America, instead of provoking the inhabitants of that country, will endear us to them for ever, and secure their good-will.

This spirit, however, without knowledge, would be little better than a brutal rage. Let us tenderly and kindly cherish, therefore, the means of knowledge. Let us dare to read, think, speak, and write. Let every order and degree among the people rouse their attention and animate their resolution. Let them all become attentive to the grounds and principles of government, ecclesiastical and civil. Let us study the law of nature; search into the spirit of the British constitution; read the histories of ancient ages; contemplate the great examples of Greece and Rome; set before us the conduct of our own British ancestors, who have defended for us the inherent rights of mankind against foreign and domestic tyrants and usurpers, against arbitrary kings and cruel priests, in short, against the gates of earth and hell. Let us read and recollect and impress upon our souls the views and ends of our own more immediate forefathers, in exchanging their native country for a dreary, inhospitable wilderness. Let us examine into the nature of that power, and the cruelty of that oppression, which drove them from their homes. Recollect their amazing fortitude, their bitter sufferings, — the hunger, the nakedness, the cold, which they patiently endured, — the severe labors of clearing their grounds, building their houses, raising their provisions, amidst dangers from wild beasts and savage men, before they had time or money or materials for commerce. Recollect the civil and religious principles and hopes and expectations which constantly supported and carried them through all hardships with patience and resignation. Let us recollect it was liberty, the hope of liberty for themselves and us and ours, which conquered all discouragements, dangers, and trials. In such researches as these, let us all in our several departments cheerfully engage, — but especially the proper patrons and supporters of law, learning, and religion!

Let the pulpit resound with the doctrines and sentiments of religious liberty. Let us hear the danger of thralldom to our consciences from ignorance, extreme poverty, and dependence, in short, from civil and political slavery. Let us see delineated before us the true map of man. Let us hear the dignity of his nature, and the noble rank he holds among the works of God, — that consenting to slavery is a sacrilegious breach of trust, as offensive in the sight of God as it is derogatory from our own honor or interest or happiness, — and that God Almighty has promulgated from heaven, liberty, peace, and good-will to man!

Let the bar proclaim, “the laws, the rights, the generous plan of power” delivered down from remote antiquity, — inform the world of the mighty struggles and numberless sacrifices made by our ancestors in defense of freedom. Let it be known, that British liberties are not the grants of princes or parliaments, but original rights, conditions of original contracts, coequal with prerogative, and coeval with government; that many of our rights are inherent and essential, agreed on as maxims, and established as preliminaries, even before a parliament existed. Let them search for the foundations of British laws and government in the frame of human nature, in the constitution of the intellectual and moral world. There let us see that truth, liberty, justice, and benevolence, are its everlasting basis; and if these could be removed, the superstructure is overthrown of course.

Let the colleges join their harmony in the same delightful concert. Let every declamation turn upon the beauty of liberty and virtue, and the deformity, turpitude, and malignity, of slavery and vice. Let the public disputations become researches into the grounds and nature and ends of government, and the means of preserving the good and demolishing the evil. Let the dialogues, and all the exercises, become the instruments of impressing on the tender mind, and of spreading and distributing far and wide, the ideas of right and the sensations of freedom.

In a word, let every sluice of knowledge be opened and set a-flowing. The encroachments upon liberty in the reigns of the first James and the first Charles, by turning the general attention of learned men to government, are said to have produced the greatest number of consummate statesmen which has ever been seen in any age or nation. The Brookes, Hampdens, Vanes, Seldens, Miltons, Nedhams, Harringtons, Nevilles, Sidneys, Lockes, are all said to have owed their eminence in political knowledge to the tyrannies of those reigns. The prospect now before us in America, ought in the same manner to engage the attention of every man of learning, to matters of power and of right, that we may be neither led nor driven blindfolded to irretrievable destruction. Nothing less than this seems to have been meditated for us, by somebody or other in Great Britain. There seems to be a direct and formal design on foot, to enslave all America. This, however, must be done by degrees. The first step that is intended, seems to be an entire subversion of the whole system of our fathers, by the introduction of the canon and feudal law into America. The canon and feudal systems, though greatly mutilated in England, are not yet destroyed. Like the temples and palaces in which the great contrivers of them once worshipped and inhabited, they exist in ruins; and much of the domineering spirit of them still remains. The designs and labors of a certain society, to introduce the former of them into America, have been well exposed to the public by a writer of great abilities; and the further attempts to the same purpose, that may be made by that society, or by the ministry or parliament, I leave to the conjectures of the thoughtful. But it seems very manifest from the Stamp Act itself, that a design is formed to strip us in a great measure of the means of knowledge, by loading the press, the colleges, and even an almanac and a newspaper, with restraints and duties; and to introduce the inequalities and dependencies of the feudal system, by taking from the poorer sort of people all their little subsistence, and conferring it on a set of stamp officers, distributors, and their deputies. But I must proceed no further at present. The sequel, whenever I shall find health and leisure to pursue it, will be a “disquisition of the policy of the stamp act.” In the mean time, however, let me add, — These are not the vapors of a melancholy mind, nor the effusions of envy, disappointed ambition, nor of a spirit of opposition to government, but the emanations of a heart that burns for its country’s welfare. No one of any feeling, born and educated in this once happy country, can consider the numerous distresses, the gross indignities, the barbarous ignorance, the haughty usurpations, that we have reason to fear are meditating for ourselves, our children, our neighbors, in short, for all our countrymen and all their posterity, without the utmost agonies of heart and many tears.

1 Rob. Hist. ch. v. pp. 178-9, &c.

2 “I always consider the settlement of America with reverence and wonder, as the opening of a grand scene and design in Providence for the illumination of the ignorant, and the emancipation of the slavish part of mankind all over the earth.”

3 Edes and Gill, printers of the Boston Gazette.

Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress

The regulations lately made, see our list of programs.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

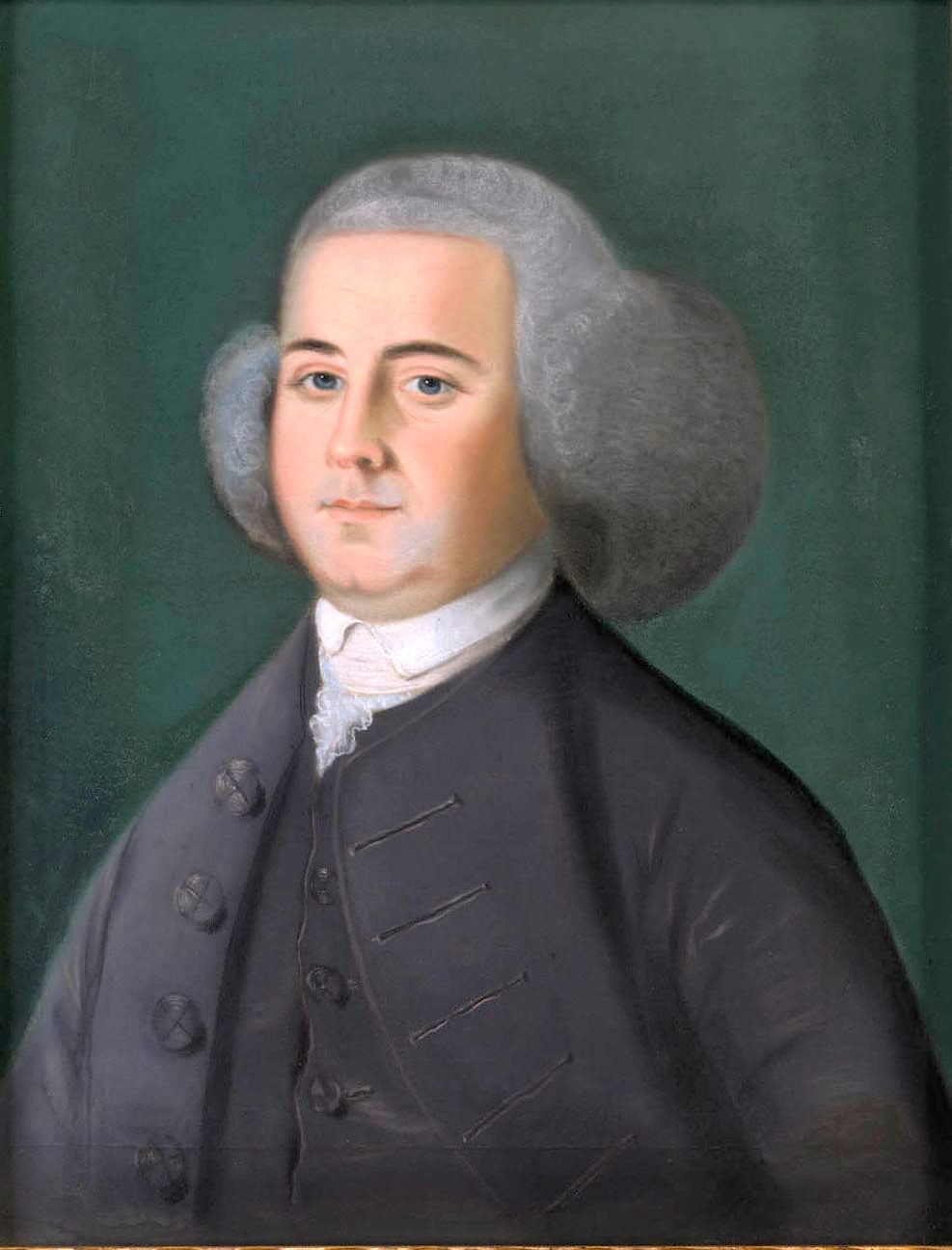

Declamation 01: John Adamsʼ Dissertation on the Canon and the Feudal Law

Audio with external links item preview.

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

This declamation features a reading by Carl Malamud of A Dissertation on the Canon and the Feudal Law. The dissertation was written by John Adams when he was 30 years old. In this selection, Carl Malamud reads Part 4 of the Dissertation, a stirring plea for an informed citizenry and access to knowledge. This section was published on October 21, 1765, when Adams was just 30 years old.

This classic text is available with footnotes on the National Archives selections of Founders Online: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-01-02-0052-0007

Public Resource waives all intellectual property rights on this video. No rights reserved.

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Download options, in collections.

Uploaded by Public Resource on November 1, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

[fragmentary draft of a dissertation on canon and feudal law, february 1765.] [from the diary of john adams], [ fragmentary draft of a dissertation on canon and feudal law, february 1765. ].

This Sodality has given rise to the following Speculation of my own, which I commit to writing, as Hints for future Enquiries rather than as a satisfactory Theory. 1

The Desire of < Power >< Power > Dominion, that encroaching, grasping, restless, and ungovernable Principle in human Nature, that Principle which has made so much Havock and Desolation, among the Works of God, in all the Variety of systems, that have been invented, for its Gratification, was never so successfull, as in the Invention and Establishment of the Cannon and the Feudal Law.—By the former the most refined, sublime, extensive, and astonishing Constitution of Policy, that was ever conceived by the Human Mind, was framed, by the Romish Clergy, for the Aggrandisement of their own order. This Constitution will be allowed to deserve all the Epithets I have given it, when it is considered, that they found Ways to make the World believe that God had entrusted them with Keys of Heaven whose Gates they might open and shut at Pleasure, with the Power of Dispensation over all the Rules and Types of Morality, the Power of licensing all sorts both of sins and Crimes, with the Power of Deposing Princes, and absolving all their subjects from their Allegiance, with the Power of Procuring or withholding the Rain of Heaven, and the Beams of the Sun, with the Power of Earthquakes, < Plagues, > Pestilence, Famine; nay with the Power of creating Blood Nay the Blood of God out of Wine, and Flesh the Flesh of God out of Bread. Thus was human Nature held for Ages, fast Bound in servitude, in a cruel, shameful, deplorable Bondage to him and his subordinate Tyrants who it was fortold in the Apocalypse, would exalt himself above all that is called God and that is worshiped.

By the latter another system was formed similar to the former in some Respects, and altho it was originally contrived perhaps for the necessary Defence of a barbarous < Nation > People against the Inroads and Invasions of her neighbouring Nations; yet it was soon adopted by almost all the Princes in Europe, and wrought into the Constitution of their Governments for the same Purposes of Tyranny, Cruelty and Lust. This Constitution was originally a Code of Laws for a vast Army, in a perpetual Encampment. The General was invested with the Property of all the Land within [ sentence unfinished ] 2

It 3 was a Resolution formed by a sensible People almost in despair. They had become intelligent in general, and some of them learned but they had been galled, and fretted, and whipped and cropped, and hanged and burned. In short they had been so worried by Plagues and Tortures in every Shape, and they utterly despaired of Deliverance from these Miseries in their own Country, that they at last resolved to fly to the Wilderness, for Refuge from the temporal and spiritual Principalities and Powers, and Plagues and scourges of their Native Country.

After their Arrival here, they began their settlements and pursued their Plan both of Ecclesiastical and Civil Government in direct Opposition to the Cannon And the feudal systems.

Their first Concern was to preserve and propagate Knowledge. The leading Men among the first Settlers of America, were Men of sense and Learning. And the Clergymen, who came over first, were familiar with the Historians, Orators, Poets and Phylosophers of Greece and Rome, and many of them have left behind them Libraries which are still in Being consisting chiefly of Books, whose Character their great Grand sons can scarcely read. 4

I always consider the settlement of America with Reverence and Wonder—as the Opening of a grand scene and Design in Providence, for the Illumination of the Ignorant and the Emancipation of the slavish Part of Mankind all over the Earth.

their great grand sons, tho educated at European Universities, can scarcely read. Archbishop King him self, (I think it was, for I say this upon Memory) observed of the Puritans in General, that they were much more intelligent, and better read than the Members of the Church whom he reproaches, and censures very warmly for that Reason.

Provision was early made by Law, that every Town should be accommodated with a grammar school—under a severe Penalty—so that even Negligence of Learning was made a Crime, a Stretch of Wisdom in Policy that was never equalled before nor since unless by the ancient Egyptians who made the Want of Generosity and Humanity a Capital Crime.

But besides the Obligation laid on every Town to provide the means of Learning, a Colledge nay a Number of Colledges were formed very early, and a very early Attention to them from the Legislature, exempted from Military Duties—exemptions from Taxes, and many other Encouragements have taken Place. And in fine We their Posterity, have seen the Fruits and Consequences of the Wisdom and Goodness of our Forefathers. All Ranks and orders of our People, are intelligent, are accomplished—a Native of America, especially of New England, who cannot read and wright is as rare a Phenomenon as a Comet.

Remainder of the Piece begun in our last.—

Thus accomplished were the first Settlers of these Colonies—and as has been said, Tyranny in every shape, was their Disdain and Abhorrence. No < Kind of > Fear of Punishment not even of Death itself, in exquisite Torture had been sufficient to conquer that steady, manly, pertinacious Spirit, with which they opposed the Tyrants of those Days in Church and state. And their greatest Concern seems to have been to establish a Government of the Church, more consistent with the scriptures, and a Government of the state more agreable to the Dignity of human Nature, than they had ever seen in Europe. They knew that beautiful were the feet &c. But They saw clearly, that of all the < ridiculous > Nonsense, Delusion, and Frenzy that had ever passed thro the Mind of Man, none had ever been more glaring and extravagant than the Notions of the Cannon Law, of the indellible Character, the perpetual succession, the virtuous and sanctified Effluvia from Episcopal Fingers, and all the rest of that dark Ribaldry which had thrown such a Glare of Mistery, Sanctity, Reverence and Right Reverence, Eminence and Holiness around the Idea of a Priest [ sentence unfinished ]

1 . The paragraphs that follow comprise JA ’s first thoughts for the important and eloquent essay to which he gave no name but which later became known as “A Dissertation on Canon and Feudal Law.” (In his Autobiography JA observed that “It might as well have been called an Essay upon Forefathers Rock”— i.e. what is now known as Plymouth Rock.) The date here assigned to this very rough draft is conjectural, but since it immediately follows the Diary entry of 21 Feb. 1765, being separated from it only by a line across the page, we can say with some confidence that JA began putting down these detached thoughts late in February. He may, of course, have continued them in the following weeks or even months.

Much revised and expanded from the early draft, JA ’s essay was published in the Boston Gazette , without a signature of any kind, in four parts, 12 and 19 Aug., 30 Sept., and 21 Oct. 1765, whence it was reprinted in the London Chronicle in corresponding installments, 23 and 28 Nov., 3 and 26 Dec. 1765, under a title furnished by Thomas Hollis: “A Dissertation on the Feudal and the Canon Law.” For its subsequent bibliographical history, see CFA ’s valuable but not completely reliable introductory note to his reprint in JA’s Works description begins The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: with a Life of the Author, ed. Charles Francis Adams, Boston, 1850–1856; 10 vols. description ends , 3:447–448. No attempt is made in the present text of the draft to show the variations between it and the published version, but readers who wish to see how JA used and revised his first thoughts will find nearly all of them embedded in the final version as reprinted in his Works description begins The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States: with a Life of the Author, ed. Charles Francis Adams, Boston, 1850–1856; 10 vols. description ends , in the following order: p. 449–450, 451–452, 455–456, 452–453. It should be noted that the draft contains rudiments of only the first three parts of the essay as printed in the newspapers; the last installment, with its references to the Stamp Act (passed 22 March 1765), was doubtless composed later.

2 . An interval of space follows at this point in the MS , denoting a gap in the draft.

3 . That is, the Puritans’ decision to leave England and settle in America. (In the next sentence JA wrote the word “Puritans” above the initial “They.”)

4 . Last four words interlined. Evidently the next paragraph (which is the only substantial passage in the draft not in the text as printed in the Boston Gazette ) was an afterthought, and the passage after that originally continued the present paragraph.

Index Entries

You are looking at, ancestor groups.

- Human Resource

- Business Strategy

- Operations Management

- Project Management

- Business Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Scholarship Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Buy Essay Online

- College Essay Help

- Help To Write Essay Online

Well-planned online essay writing assistance by PenMyPaper

Writing my essays has long been a part and parcel of our lives but as we grow older, we enter the stage of drawing critical analysis of the subjects in the writings. This requires a lot of hard work, which includes extensive research to be done before you start drafting. But most of the students, nowadays, are already overburdened with academics and some of them also work part-time jobs. In such a scenario, it becomes impossible to write all the drafts on your own. The writing service by the experts of PenMyPaper can be your rescuer amidst such a situation. We will write my essay for me with ease. You need not face the trouble to write alone, rather leave it to the experts and they will do all that is required to write your essays. You will just have to sit back and relax. We are offering you unmatched service for drafting various kinds for my essays, everything on an online basis to write with. You will not even have to visit anywhere to order. Just a click and you can get the best writing service from us.

Definitely! It's not a matter of "yes you can", but a matter of "yes, you should". Chatting with professional paper writers through a one-on-one encrypted chat allows them to express their views on how the assignment should turn out and share their feedback. Be on the same page with your writer!

Finished Papers

Standard essay helper

Deadlines can be scary while writing assignments, but with us, you are sure to feel more confident about both the quality of the draft as well as that of meeting the deadline while we write for you.

1035 Natoma Street, San Francisco

This exquisite Edwardian single-family house has a 1344 Sqft main…

What if I’m unsatisfied with an essay your paper service delivers?

- Member Login

Perfect Essay

Adams Papers Digital Edition

Papers of john adams, volume 1.

“IGNORANCE and inconsideration are the two great causes of the ruin of mankind.” This is an observation of Dr. Tillotson , 1 with relation to the interest of his fellow-men, in a future and immortal state: But it is of equal truth and importance, if applied to the happiness of men in society, on this side the grave. In the earliest ages of the world, absolute monarchy seems to have been the universal form of government. Kings, and a few of their great counsellors and captains, exercised a cruel tyranny over the people who held a rank in the scale of intelligence, in those days, but little higher than the camels and elephants, that carried them and their engines to war.

BY what causes it was bro't to pass, that the people in the middle ages, became more intelligent in general, would not perhaps be possible in these days to discover: But the fact is certain; and wherever a general knowledge and sensibility have prevail'd among the people , arbitrary government, and every kind of oppression, have lessened and disappeared in proportion. Man has certainly an exalted soul! and the same principle in humane nature, that aspiring noble principle, founded in benevolence, and cherished by knowledge, I mean the love of power, which has been so often the cause of slavery , has, whenever freedom has existed, been the cause of freedom. If it is this principle, that has always prompted the princes and nobles of the earth, by every species of fraud and violence, to shake off, all the limitations of their power; it is the same that has always stimulated the common people to aspire at independency, and to endeavor at confining the power of the great within the limits of equity and reason.

THE poor people, it is true, have been much less successful than the great. They have seldom found either leisure or opportunity to form an union and exert their strength—ignorant as they were of arts and letters, they have seldom been able to frame and support a regular opposition. This, however, has been known, by the great, to be the temper of mankind, and they have accordingly laboured, in all ages, to wrest from the populace, as they are contemptuously called, the 112 knowledge of their rights and wrongs, and the power to assert the former or redress the latter. I say RIGHTS, for such they have, undoubtedly, antecedent to all earthly government— Rights that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws— Rights derived from the great legislator of the universe.

SINCE the promulgation of Christianity, the two greatest systems of tyranny, that have sprung from this original, are the cannon and the feudal law. The desire of dominion, that great principle by which we have attempted to account for so much good, and so much evil, is, when properly restrained , a very useful and noble movement in the human mind: But when such restraints are taken off, it becomes an incroaching, grasping, restless and ungovernable power. Numberless have been the systems of iniquity, contrived by the great, for the gratification of this passion in themselves: but in none of them were they ever more successful, than in the invention and establishment of the cannon and the feudal law.

BY the former of these, the most refined, sublime, extensive, and astonishing constitution of policy, that ever was conceived by the mind of man, was framed by the Romish clergy for the aggrandisement of their own order. 2 All the epithets I have here given to the Romish policy are just: and will be allowed to be so, when it is considered, that they even persuaded mankind to believe, faithfully and undoubtingly, that GOD almighty had intrusted them with the keys of heaven; whose gates they might open and close at pleasure—with a power of dispensation over all the rules and obligations of morality—with authority to licence all sorts of sins and crimes—with a power of deposing princes, and absolving subjects from allegiance—with a power of procuring or withholding the rain of heaven and the beams of the sun—with the management of earthquakes, pestilence and famine. Nay with the mysterious, awful, incomprehensible power of creating out of bread and wine, the flesh and blood of God himself. All these opinions, they were enabled to spread and rivet among the people, by reducing their minds to a state of sordid ignorance and staring timidity; and by infusing into them a religious horror of letters and knowledge. Thus was human nature chained fast for ages, in a cruel, shameful and deplorable servitude, to him and his subordinate tyrants, who, it was foretold, would exalt himself above all that was called God, and that was worshipped.

IN the latter, we find another system similar in many respects, to the former: 3 which, altho' it was originally formed perhaps, for the necessary defence of a barbarous people, against the inroads and in- 113 vasions of her neighbouring nations; yet, for the same purposes of tyranny, cruelty and lust, which had dictated the cannon law, it was soon adopted by almost all the princes of Europe, and wrought into the constitutions of their government. It was originally, a code of laws, for a vast army, in a perpetual encampment. The general was invested with the sovereign propriety of all the lands within the territory. Of him , as his servants and vassals, the first rank of his great officers held the lands: and in the same manner, the other subordinate officers held of them ; and all ranks and degrees held their lands, by a variety of duties and services , all tending to bind the chains the faster, on every order of mankind. In this manner, the common people were held together, in herds and clans, in a state of servile dependance on their lords; bound, even by the tenure of their lands to follow them, whenever they commanded, to their wars; and in a state of total ignorance of every thing divine and human, excepting the use of arms, and the culture of their lands.

BUT, another event still more calamitous to human liberty, was a wicked confederacy, between the two systems of tyranny above described. It seems to have been even stipulated between them, that the temporal grandees should contribute every thing in their power to maintain the ascendency of the priesthood ; and that the spiritual grandees, in their turn, should employ that 4 ascendency over the consciences of the people , in impressing on their minds, a blind, implicit obedience to civil magistracy.

THUS, as long as this confederacy lasted, and the people were held in ignorance; Liberty, and with her, Knowledge, and Virtue too, seem to have deserted the earth; and one age of darkness, succeeded another, till GOD, in his benign providence, raised up the champions, who began and conducted the reformation. From the time of the reformation, to the first settlement of America , knowledge gradually spread in Europe, but especially in England ; and in proportion as that increased and spread among the people, ecclesiastical and civil tyranny, which I use as synonimous expressions, for the cannon and feudal laws, seem to have lost their strength and weight. The people grew more and more sensible of the wrong that was done them, by these systems; more and more impatient under it; and determined at all hazards to rid themselves of it; till, at last, under the execrable race of the Steuarts , 5 the struggle between the people and the confederacy aforesaid of temporal and spiritual tyranny, became formidable, violent and bloody.

IT was this great struggle, that peopled America. It was not religion 114 alone , as is commonly supposed; but it was a love of universal Liberty , and an hatred, a dread, an horror of the infernal confederacy, before described, that projected, conducted, and accomplished the settlement of America.

IT was a resolution formed, by a sensible people, I mean the Puritans , almost in despair. They had become intelligent in general, and many of them learned. For this fact I have the testimony of archbishop King 6 himself, who observed of that people, that they were more intelligent, and better read than even the members of the church whom he censures warmly for that reason. This people had been so vexed, and tortured by the powers of those days, for no other crime than their knowledge, and their freedom of enquiry and examination, and they had so much reason to despair of deliverance from those miseries, on that side the ocean; that they at last resolved to fly to the wilderness for refuge, from the temporal and spiritual principalities and powers, and plagues, and scourges, of their native country.

AFTER their arrival here, they began their settlements, and formed their plan both of ecclesiastical and civil government, in direct opposition to the cannon and the feudal systems. The leading men among them, both of the clergy and the laity, were men of sense and learning: To many of them, the historians, orators, poets and philosophers of Greece and Rome were quite familiar: and some of them have left libraries that are still in being, consisting chiefly of volumes, in which the wisdom of the most enlightned ages and nations is deposited, written however in languages, which their great grandsons, tho' educated in European Universities , can scarcely read.

Reprinted from the Boston Gazette , 12 Aug. 1765. For partial Dft , see No. II , above, and descriptive note.

John Tillotson (1630–1694) , Archbishop of Canterbury, popular preacher, and warm advocate of religious comprehension among English Protestants. JA owned an incomplete set of Tillotson's Works and admired the high moral tone of the Archbishop's sermons ( DNB ; Catalogue of JA 's Library ; JA, Diary and Autobiography , 1:224 ).

In his copy of True Sentiments . . . , containing the “Dissertation,” JA wrote the following marginal note at this point: “Rob. Hist. C. 5, page 54, and 141, 315.” The reference is to William Robertson, The History of the Reign of Charles the Fifth, Emperor of Germany; and of All the Kingdoms and States in Europe during His Age , 3 vols. [Phila.], 1770. Catalogue of JA 's Library lists only a London edition of 1777 in 4 vols., but the pages listed here and below match the 1770 edition.

JA 's marginal note here reads, “Rob. Hist. C. 5, 178, 9 &c.”

JA corrected the word that to read their.

JA underlined the whole phrase “the execrable race of the Steuarts.”

Since there was no Archbishop King in England during the reigns of James I and Charles I, the period presumably under discussion, the reference here is uncertain. In one of his drafts JA attributed this comment on Puritan su- 115 periority to “Archbishop King him self, (I think it was, for I say this upon Memory)” ( JA, Diary and Autobiography , 1:257 ). There were two bishops named King in the period: John (1559?–1621), Bishop of London, 1611–1621, and Henry (1592–1669), Bishop of Chichester, 1642–1669 ( DNB ).

THUS accomplished were many of the first Planters of these Colonies. It may be thought polite and fashionable, by many modern fine Gentlemen perhaps, to deride the Characters of these Persons, as enthusiastical, superstitious and republican: But such ridicule is founded in nothing but foppery and affectation, and is grosly injurious and false. Religious to some degree of enthusiasm it may be admitted they were; but this can be no peculiar derogation from their character, because it was at that time almost the universal character, not only of England, but of Christendom. Had this however, been otherwise, their enthusiasm, considering the principles in which it was founded, and the ends to which it was directed, far from being a reproach to them, was greatly to their honour: for I believe it will be found universally true, that no great enterprize, for the honour or happiness of mankind, was ever achieved, without a large mixture of that noble infirmity. Whatever imperfections may be justly ascribed to them, which however are as few, as any mortals have discovered their judgment in framing their policy, was founded in wise, humane and benevolent principles; It was founded in revelation, and in reason too; It was consistent with the principles, of the best, and greatest, and wisest legislators of antiquity. Tyranny in every form, shape, and appearance was their disdain, and abhorrence; no fear of punishment, not even of Death itself, in exquisite tortures, had been sufficient to conquer, that steady, manly, pertenacious spirit, with which they had opposed the tyrants of those days, in church and state. They were very far from being enemies to monarchy; and they knew as well as any men, the just regard and honour that is due to the character of a dispenser of the misteries of the gospel of Grace: But they saw clearly, that popular powers must be placed, as a guard, a countroul, a ballance, to the powers of the monarch, and the priest, in every government, or else it would soon become the man of sin, the whore of Babylon, the mystery of iniquity, a great and detestable system of fraud, violence, and usurpation. Their greatest concern seems to have been to establish a government of the church more consistent with 116 the scriptures, and a government of the state more agreable to the dignity of humane nature, than any they had seen in Europe: and to transmit such a government down to their posterity, with the means of securing and preserving it, for ever. To render the popular power in their new government, as great and wise, as their principles and theory, i. e. as human nature and the christian religion require it should be, they endeavored to remove from it, as many of the feudal inequalities and dependencies, as could be spared, consistently with the preservation of a mild limited monarchy. And in this they discovered the depth of their wisdom, and the warmth of their friendship to human nature. But the first place is due to religion. They saw clearly, that of all the nonsense and delusion which had ever passed thro' the mind of man, none had ever been more extravagant than the notions of absolutions, indelible characters, uninterrupted successions, and the rest of those phantastical ideas, derived from the common law, 1 which had thrown such a glare of mystery, sanctity, reverence and right reverence, eminence and holiness, around the idea of a priest, as no mortal could deserve, and as always must from the constitution of human nature, be dangerous in society. 2 For this reason, they demolished the whole system of Diocesan episcopacy and deriding, as all reasonable and impartial men must do, the ridiculous fancies of sanctified effluvia from episcopal fingers, they established sacerdotal ordination, on the foundation of the bible and common sense. This conduct at once imposed an obligation on the whole body of the clergy, to industry, virtue, piety and learning, and rendered that whole body infinitely more independent on the civil powers, in all respects than they could be where they were formed into a scale of subordination, from a pope down to priests and fryars and confessors, necessarily and essentially a sordid, stupid, wretched herd; or than they could be in any other country, where an archbishop held the place of an universal bishop, and the vicars and curates that of the ignorant, dependent, miserable rabble aforesaid; and infinitely more sensible and learned than they could be in either. This subject has been seen in the same light, by many illustrious patriots, who have lived in America, since the days of our fore fathers, and who have adored their memory for the same reason. And methinks there has not appeared in New England a stronger veneration for their memory, a more penetrating insight into the grounds and principles and spirit of their policy, nor a more earnest desire of perpetuating the blessings of it to posterity, than that fine institution of the late chief justice Dudley, of a lecture against popery, and on the validity of presbyterian 117 ordination. 3 This was certainly intended by that wise and excellent man, as an eternal memento of the wisdom and goodness of the very principles that settled America. But I must again return to the feudal law.

The adventurers so often mentioned, had an utter contempt of all that dark ribaldry of hereditary indefeasible right—the Lord's anointed—and the divine miraculous original of government, with which the priesthood had inveloped the feudal monarch in clouds and mysteries, and from whence they had deduced the most mischievous of all doctrines, that of passive obedience and non resistance. They knew that government was a plain, simple, intelligible thing founded in nature and reason and quite comprehensible by common sense. They detested all the base services, and servile dependencies of the feudal system. They knew that no such unworthy dependences took place in the ancient seats of liberty, the republic of Greece and Rome: and they tho't all such slavish subordinations were equally inconsistent with the constitution of human nature and that religious liberty, with which Jesus had made them free. This was certainly the opinion they had formed, and they were far from being singular or extravagant in thinking so. Many celebrated modern writers, in Europe, have espoused the same sentiments. Lord Kaim's, 4 a Scottish writer of great reputation, whose authority in this case ought to have the more weight, as his countrymen have not the most worthy ideas of liberty, speaking of the feudal law, says, “A constitution so contradictory to all the principles which govern mankind, can never be brought about, one should imagine, but by foreign conquest or native usurpations.” Brit. Ant. P. 2. Rousseau speaking of the same system, calls it “That most iniquitous and absurd form of government by which human nature was so shamefully degraded.” Social Compact, Page 164. 5 It would be easy to multiply authorities, but it must be needless, because as the original of this form of government was among savages, as the spirit of it is military and despotic, every writer, who would allow the people to have any right to life or property, or freedom, more than the beasts of the field, and who was not hired or inlisted under arbitrary lawless power, has been always willing to admit the feudal system to be inconsistent with liberty and the rights of mankind.

MS not found. Reprinted from the ( Boston Gazette , 19 Aug. 1765).

A printer's error for canon law , corrected in reprintings.

In JA 's copy of True Sentiments . . . , containing the “Dissertation,” penciled in the margin opposite the beginning of this sentence are the words “omit No Papist” and a shaky line is drawn down the passage to include the whole sentence.

JA 's praise of Dudley's gift to Har- 118 vard may have been prompted by Jonathan Mayhew's Dudleian Lecture of May 1765, in which he not only denounced Catholic doctrine but warned that the Church was a threat to civil liberty as well. In a manner strikingly parallel to the argument of JA 's “Dissertation,” Mayhew declared that “Our controversy with her [Rome] is not merely a religious one. . . . But a defence of our laws, liberties and civil rights as men, in opposition to the proud claims of ecclesiastical persons, who under the pretext of religion and saving mens souls, would engross all power and property to themselves, and reduce us to the most abject slavery. . . . Popery and liberty are incompatible; at irreconcileable enmity with each other” ( Popish Idolatry . . . , cited in Charles W. Akers, Called Unto Liberty: A Life of Jonathan Mayhew, 1720–1766 , Cambridge, 1964, p. 195–196).

Henry Home, Lord Kames (1692–1782) , Scottish judge and philosopher, wrote Essays upon Several Subjects concerning British Antiquities . . . , Edinburgh, 1747, one section of which dealt with the “Introduction of the Feudal Law into Scotland” ( DNB ). The third edition of this work (Edinburgh, 1763) is listed in Catalogue of JA 's Library ; JA was thoroughly familiar with Kames before he began to write the “Dissertation” ( Diary and Autobiography , 1:254 ).

Jean Jacques Rousseau, A Treatise on the Social Compact; or the Principles of Politic Law , London, 1764 ( Catalogue of JA 's Library ). The sentence begins, “The notion of representatives is modern, descending to us from the feudal system, that most iniquitous.”

How Our Paper Writing Service Is Used

We stand for academic honesty and obey all institutional laws. Therefore EssayService strongly advises its clients to use the provided work as a study aid, as a source of ideas and information, or for citations. Work provided by us is NOT supposed to be submitted OR forwarded as a final work. It is meant to be used for research purposes, drafts, or as extra study materials.

- Words to pages

- Pages to words

Margurite J. Perez

Niamh Chamberlain

receive 15% off

Customer Reviews

Perfect Essay

Finished Papers

Customer Reviews

Orders of are accepted for higher levels only (University, Master's, PHD). Please pay attention that your current order level was automatically changed from High School/College to University.

Niamh Chamberlain

A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law

"Ignorance and inconsideration are the two great causes of the ruin of mankind." This is an observation of Dr. Tillotson, with relation to the interest of his fellow men in a future and immortal state. But it is of equal truth and importance if applied to the happiness of men in society, on this side the grave. In the earliest ages of the world, absolute monarchy seems to have been the universal form of government. Kings, and a few of their great counsellors and captains, exercised a cruel tyranny over the people, who held a rank in the scale of intelligence, in those days, but little higher than the camels and elephants that carried them and their engines to war.

By what causes it was brought to pass, that the people in the middle ages became more intelligent in general, would not, perhaps, be possible in these days to discover. But the fact is certain; and wherever a general knowledge and sensibility have prevailed among the people, arbitrary government and every kind of oppression have lessened and disappeared in proportion. Man has certainly an exalted soul; and the same principle in human nature,—-that aspiring, noble principle founded in benevolence, and cherished by knowledge; I mean the love of power, which has been so often the cause of slavery,—-has, whenever freedom has existed, been the cause of freedom. If it is this principle that has always prompted the princes and nobles of the earth, by every species of fraud and violence to shake off all the limitations of their power, it is the same that has always stimulated the common people to aspire at independency, and to endeavor at confining the power of the great within the limits of equity and reason.

The poor people, it is true, have been much less successful than the great. They have seldom found either leisure or opportunity to form a union and exert their strength; ignorant as they were of arts and letters, they have seldom been able to frame and support a regular opposition. This, however, has been known by the great to be the temper of mankind; and they have accordingly labored, in all ages, to wrest from the populace, as they are contemptuously called, the knowledge of their rights and wrongs, and the power to assert the former or redress the latter. I say rights, for such they have, undoubtedly, antecedent to all earthly government,—- Rights , that cannot be repealed or restrained by human laws—- Rights , derived from the great Legislator of the universe.