- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Process Steps: What they are + How To Follow

There are various approaches to conducting basic and applied research. This article explains the research process steps you should know. Whether you are doing basic research or applied research, there are many ways of doing it. In some ways, each research study is unique since it is conducted at a different time and place.

Conducting research might be difficult, but there are clear processes to follow. The research process starts with a broad idea for a topic. This article will assist you through the research process steps, helping you focus and develop your topic.

Research Process Steps

The research process consists of a series of systematic procedures that a researcher must go through in order to generate knowledge that will be considered valuable by the project and focus on the relevant topic.

To conduct effective research, you must understand the research process steps and follow them. Here are a few steps in the research process to make it easier for you:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

Finding an issue or formulating a research question is the first step. A well-defined research problem will guide the researcher through all stages of the research process, from setting objectives to choosing a technique. There are a number of approaches to get insight into a topic and gain a better understanding of it. Such as:

- A preliminary survey

- Case studies

- Interviews with a small group of people

- Observational survey

Step 2: Evaluate the Literature

A thorough examination of the relevant studies is essential to the research process . It enables the researcher to identify the precise aspects of the problem. Once a problem has been found, the investigator or researcher needs to find out more about it.

This stage gives problem-zone background. It teaches the investigator about previous research, how they were conducted, and its conclusions. The researcher can build consistency between his work and others through a literature review. Such a review exposes the researcher to a more significant body of knowledge and helps him follow the research process efficiently.

Step 3: Create Hypotheses

Formulating an original hypothesis is the next logical step after narrowing down the research topic and defining it. A belief solves logical relationships between variables. In order to establish a hypothesis, a researcher must have a certain amount of expertise in the field.

It is important for researchers to keep in mind while formulating a hypothesis that it must be based on the research topic. Researchers are able to concentrate their efforts and stay committed to their objectives when they develop theories to guide their work.

Step 4: The Research Design

Research design is the plan for achieving objectives and answering research questions. It outlines how to get the relevant information. Its goal is to design research to test hypotheses, address the research questions, and provide decision-making insights.

The research design aims to minimize the time, money, and effort required to acquire meaningful evidence. This plan fits into four categories:

- Exploration and Surveys

- Data Analysis

- Observation

Step 5: Describe Population

Research projects usually look at a specific group of people, facilities, or how technology is used in the business. In research, the term population refers to this study group. The research topic and purpose help determine the study group.

Suppose a researcher wishes to investigate a certain group of people in the community. In that case, the research could target a specific age group, males or females, a geographic location, or an ethnic group. A final step in a study’s design is to specify its sample or population so that the results may be generalized.

Step 6: Data Collection

Data collection is important in obtaining the knowledge or information required to answer the research issue. Every research collected data, either from the literature or the people being studied. Data must be collected from the two categories of researchers. These sources may provide primary data.

- Questionnaire

Secondary data categories are:

- Literature survey

- Official, unofficial reports

- An approach based on library resources

Step 7: Data Analysis

During research design, the researcher plans data analysis. After collecting data, the researcher analyzes it. The data is examined based on the approach in this step. The research findings are reviewed and reported.

Data analysis involves a number of closely related stages, such as setting up categories, applying these categories to raw data through coding and tabulation, and then drawing statistical conclusions. The researcher can examine the acquired data using a variety of statistical methods.

Step 8: The Report-writing

After completing these steps, the researcher must prepare a report detailing his findings. The report must be carefully composed with the following in mind:

- The Layout: On the first page, the title, date, acknowledgments, and preface should be on the report. A table of contents should be followed by a list of tables, graphs, and charts if any.

- Introduction: It should state the research’s purpose and methods. This section should include the study’s scope and limits.

- Summary of Findings: A non-technical summary of findings and recommendations will follow the introduction. The findings should be summarized if they’re lengthy.

- Principal Report: The main body of the report should make sense and be broken up into sections that are easy to understand.

- Conclusion: The researcher should restate his findings at the end of the main text. It’s the final result.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

The research process involves several steps that make it easy to complete the research successfully. The steps in the research process described above depend on each other, and the order must be kept. So, if we want to do a research project, we should follow the research process steps.

QuestionPro’s enterprise-grade research platform can collect survey and qualitative observation data. The tool’s nature allows for data processing and essential decisions. The platform lets you store and process data. Start immediately!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Top 12 Interactive Presentation Software to Engage Your User

May 29, 2024

Trend Report: Guide for Market Dynamics & Strategic Analysis

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Research Process: 8 Steps in Research Process

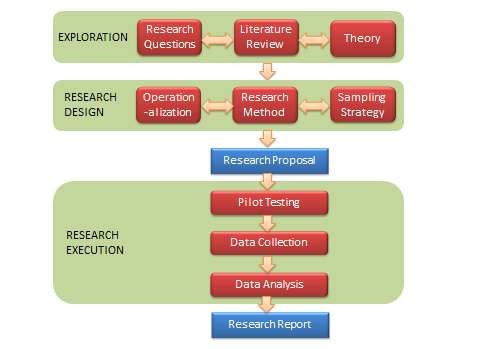

The research process starts with identifying a research problem and conducting a literature review to understand the context. The researcher sets research questions, objectives, and hypotheses based on the research problem.

A research study design is formed to select a sample size and collect data after processing and analyzing the collected data and the research findings presented in a research report.

What is the Research Process?

There are a variety of approaches to research in any field of investigation, irrespective of whether it is applied research or basic research. Each research study will be unique in some ways because of the particular time, setting, environment, and place it is being undertaken.

Nevertheless, all research endeavors share a common goal of furthering our understanding of the problem, and thus, all traverse through certain primary stages, forming a process called the research process.

Understanding the research process is necessary to effectively carry out research and sequence the stages inherent in the process.

How Research Process Work?

Eight steps research process is, in essence, part and parcel of a research proposal. It is an outline of the commitment that you intend to follow in executing a research study.

A close examination of the above stages reveals that each of these stages, by and large, is dependent upon the others.

One cannot analyze data (step 7) unless he has collected data (step 6). One cannot write a report (step 8) unless he has collected and analyzed data (step 7).

Research then is a system of interdependent related stages. Violation of this sequence can cause irreparable harm to the study.

It is also true that several alternatives are available to the researcher during each stage stated above. A research process can be compared with a route map.

The map analogy is useful for the researcher because several alternatives exist at each stage of the research process.

Choosing the best alternative in terms of time constraints, money, and human resources in our research decision is our primary goal.

Before explaining the stages of the research process, we explain the term ‘iterative’ appearing within the oval-shaped diagram at the center of the schematic diagram.

The key to a successful research project ultimately lies in iteration: the process of returning again and again to the identification of the research problems, methodology, data collection, etc., which leads to new ideas, revisions, and improvements.

By discussing the research project with advisers and peers, one will often find that new research questions need to be added, variables to be omitted, added or redefined, and other changes to be made. As a proposed study is examined and reexamined from different perspectives, it may begin to transform and take a different shape.

This is expected and is an essential component of a good research study.

Besides, examining study methods and data collected from different viewpoints is important to ensure a comprehensive approach to the research question.

In conclusion, there is seldom any single strategy or formula for developing a successful research study, but it is essential to realize that the research process is cyclical and iterative.

What is the primary purpose of the research process?

The research process aims to identify a research problem, understand its context through a literature review, set research questions and objectives, design a research study, select a sample, collect data, analyze the data, and present the findings in a research report.

Why is the research design important in the research process?

The research design is the blueprint for fulfilling objectives and answering research questions. It specifies the methods and procedures for collecting, processing, and analyzing data, ensuring the study is structured and systematic.

8 Steps of Research Process

Identifying the research problem.

The first and foremost task in the entire process of scientific research is to identify a research problem .

A well-identified problem will lead the researcher to accomplish all-important phases of the research process, from setting objectives to selecting the research methodology .

But the core question is: whether all problems require research.

We have countless problems around us, but all we encounter do not qualify as research problems; thus, these do not need to be researched.

Keeping this point in mind, we must draw a line between research and non-research problems.

Intuitively, researchable problems are those that have a possibility of thorough verification investigation, which can be effected through the analysis and collection of data. In contrast, the non-research problems do not need to go through these processes.

Researchers need to identify both;

Non-Research Problems

Statement of the problem, justifying the problem, analyzing the problem.

A non-research problem does not require any research to arrive at a solution. Intuitively, a non-researchable problem consists of vague details and cannot be resolved through research.

It is a managerial or built-in problem that may be solved at the administrative or management level. The answer to any question raised in a non-research setting is almost always obvious.

The cholera outbreak, for example, following a severe flood, is a common phenomenon in many communities. The reason for this is known. It is thus not a research problem.

Similarly, the reasons for the sudden rise in prices of many essential commodities following the announcement of the budget by the Finance Minister need no investigation. Hence it is not a problem that needs research.

How is a research problem different from a non-research problem?

A research problem is a perceived difficulty that requires thorough verification and investigation through data analysis and collection. In contrast, a non-research problem does not require research for a solution, as the answer is often obvious or already known.

Non-Research Problems Examples

A recent survey in town- A found that 1000 women were continuous users of contraceptive pills.

But last month’s service statistics indicate that none of these women were using contraceptive pills (Fisher et al. 1991:4).

The discrepancy is that ‘all 1000 women should have been using a pill, but none is doing so. The question is: why the discrepancy exists?

Well, the fact is, a monsoon flood has prevented all new supplies of pills from reaching town- A, and all old supplies have been exhausted. Thus, although the problem situation exists, the reason for the problem is already known.

Therefore, assuming all the facts are correct, there is no reason to research the factors associated with pill discontinuation among women. This is, thus, a non-research problem.

A pilot survey by University students revealed that in Rural Town-A, the goiter prevalence among school children is as high as 80%, while in the neighboring Rural Town-A, it is only 30%. Why is a discrepancy?

Upon inquiry, it was seen that some three years back, UNICEF launched a lipiodol injection program in the neighboring Rural Town-A.

This attempt acted as a preventive measure against the goiter. The reason for the discrepancy is known; hence, we do not consider the problem a research problem.

A hospital treated a large number of cholera cases with penicillin, but the treatment with penicillin was not found to be effective. Do we need research to know the reason?

Here again, there is one single reason that Vibrio cholera is not sensitive to penicillin; therefore, this is not the drug of choice for this disease.

In this case, too, as the reasons are known, it is unwise to undertake any study to find out why penicillin does not improve the condition of cholera patients. This is also a non-research problem.

In the tea marketing system, buying and selling tea starts with bidders. Blenders purchase open tea from the bidders. Over the years, marketing cost has been the highest for bidders and the lowest for blenders. What makes this difference?

The bidders pay exorbitantly higher transport costs, which constitute about 30% of their total cost.

Blenders have significantly fewer marketing functions involving transportation, so their marketing cost remains minimal.

Hence no research is needed to identify the factors that make this difference.

Here are some of the problems we frequently encounter, which may well be considered non-research problems:

- Rises in the price of warm clothes during winter;

- Preferring admission to public universities over private universities;

- Crisis of accommodations in sea resorts during summer

- Traffic jams in the city street after office hours;

- High sales in department stores after an offer of a discount.

Research Problem

In contrast to a non-research problem, a research problem is of primary concern to a researcher.

A research problem is a perceived difficulty, a feeling of discomfort, or a discrepancy between a common belief and reality.

As noted by Fisher et al. (1993), a problem will qualify as a potential research problem when the following three conditions exist:

- There should be a perceived discrepancy between “what it is” and “what it should have been.” This implies that there should be a difference between “what exists” and the “ideal or planned situation”;

- A question about “why” the discrepancy exists. This implies that the reason(s) for this discrepancy is unclear to the researcher (so that it makes sense to develop a research question); and

- There should be at least two possible answers or solutions to the questions or problems.

The third point is important. If there is only one possible and plausible answer to the question about the discrepancy, then a research situation does not exist.

It is a non-research problem that can be tackled at the managerial or administrative level.

Research Problem Examples

Research problem – example #1.

While visiting a rural area, the UNICEF team observed that some villages have female school attendance rates as high as 75%, while some have as low as 10%, although all villages should have a nearly equal attendance rate. What factors are associated with this discrepancy?

We may enumerate several reasons for this:

- Villages differ in their socio-economic background.

- In some villages, the Muslim population constitutes a large proportion of the total population. Religion might play a vital role.

- Schools are far away from some villages. The distance thus may make this difference.

Because there is more than one answer to the problem, it is considered a research problem, and a study can be undertaken to find a solution.

Research Problem – Example #2

The Government has been making all-out efforts to ensure a regular flow of credit in rural areas at a concession rate through liberal lending policy and establishing many bank branches in rural areas.

Knowledgeable sources indicate that expected development in rural areas has not yet been achieved, mainly because of improper credit utilization.

More than one reason is suspected for such misuse or misdirection.

These include, among others:

- Diversion of credit money to some unproductive sectors

- Transfer of credit money to other people like money lenders, who exploit the rural people with this money

- Lack of knowledge of proper utilization of the credit.

Here too, reasons for misuse of loans are more than one. We thus consider this problem as a researchable problem.

Research Problem – Example #3

Let’s look at a new headline: Stock Exchange observes the steepest ever fall in stock prices: several injured as retail investors clash with police, vehicles ransacked .

Investors’ demonstration, protest and clash with police pause a problem. Still, it is certainly not a research problem since there is only one known reason for the problem: Stock Exchange experiences the steepest fall in stock prices. But what causes this unprecedented fall in the share market?

Experts felt that no single reason could be attributed to the problem. It is a mix of several factors and is a research problem. The following were assumed to be some of the possible reasons:

- The merchant banking system;

- Liquidity shortage because of the hike in the rate of cash reserve requirement (CRR);

- IMF’s warnings and prescriptions on the commercial banks’ exposure to the stock market;

- Increase in supply of new shares;

- Manipulation of share prices;

- Lack of knowledge of the investors on the company’s fundamentals.

The choice of a research problem is not as easy as it appears. The researchers generally guide it;

- own intellectual orientation,

- level of training,

- experience,

- knowledge on the subject matter, and

- intellectual curiosity.

Theoretical and practical considerations also play a vital role in choosing a research problem. Societal needs also guide in choosing a research problem.

Once we have chosen a research problem, a few more related steps must be followed before a decision is taken to undertake a research study.

These include, among others, the following:

- Statement of the problem.

- Justifying the problem.

- Analyzing the problem.

A detailed exposition of these issues is undertaken in chapter ten while discussing the proposal development.

A clear and well-defined problem statement is considered the foundation for developing the research proposal.

It enables the researcher to systematically point out why the proposed research on the problem should be undertaken and what he hopes to achieve with the study’s findings.

A well-defined statement of the problem will lead the researcher to formulate the research objectives, understand the background of the study, and choose a proper research methodology.

Once the problem situation has been identified and clearly stated, it is important to justify the importance of the problem.

In justifying the problems, we ask such questions as why the problem of the study is important, how large and widespread the problem is, and whether others can be convinced about the importance of the problem and the like.

Answers to the above questions should be reviewed and presented in one or two paragraphs that justify the importance of the problem.

As a first step in analyzing the problem, critical attention should be given to accommodate the viewpoints of the managers, users, and researchers to the problem through threadbare discussions.

The next step is identifying the factors that may have contributed to the perceived problems.

Issues of Research Problem Identification

There are several ways to identify, define, and analyze a problem, obtain insights, and get a clearer idea about these issues. Exploratory research is one of the ways of accomplishing this.

The purpose of the exploratory research process is to progressively narrow the scope of the topic and transform the undefined problems into defined ones, incorporating specific research objectives.

The exploratory study entails a few basic strategies for gaining insights into the problem. It is accomplished through such efforts as:

Pilot Survey

A pilot survey collects proxy data from the ultimate subjects of the study to serve as a guide for the large study. A pilot study generates primary data, usually for qualitative analysis.

This characteristic distinguishes a pilot survey from secondary data analysis, which gathers background information.

Case Studies

Case studies are quite helpful in diagnosing a problem and paving the way to defining the problem. It investigates one or a few situations identical to the researcher’s problem.

Focus Group Interviews

Focus group interviews, an unstructured free-flowing interview with a small group of people, may also be conducted to understand and define a research problem .

Experience Survey

Experience survey is another strategy to deal with the problem of identifying and defining the research problem.

It is an exploratory research endeavor in which individuals knowledgeable and experienced in a particular research problem are intimately consulted to understand the problem.

These persons are sometimes known as key informants, and an interview with them is popularly known as the Key Informant Interview (KII).

Reviewing of Literature

A review of relevant literature is an integral part of the research process. It enables the researcher to formulate his problem in terms of the specific aspects of the general area of his interest that has not been researched so far.

Such a review provides exposure to a larger body of knowledge and equips him with enhanced knowledge to efficiently follow the research process.

Through a proper review of the literature, the researcher may develop the coherence between the results of his study and those of the others.

A review of previous documents on similar or related phenomena is essential even for beginning researchers.

Ignoring the existing literature may lead to wasted effort on the part of the researchers.

Why spend time merely repeating what other investigators have already done?

Suppose the researcher is aware of earlier studies of his topic or related topics . In that case, he will be in a much better position to assess his work’s significance and convince others that it is important.

A confident and expert researcher is more crucial in questioning the others’ methodology, the choice of the data, and the quality of the inferences drawn from the study results.

In sum, we enumerate the following arguments in favor of reviewing the literature:

- It avoids duplication of the work that has been done in the recent past.

- It helps the researcher discover what others have learned and reported on the problem.

- It enables the researcher to become familiar with the methodology followed by others.

- It allows the researcher to understand what concepts and theories are relevant to his area of investigation.

- It helps the researcher to understand if there are any significant controversies, contradictions, and inconsistencies in the findings.

- It allows the researcher to understand if there are any unanswered research questions.

- It might help the researcher to develop an analytical framework.

- It will help the researcher consider including variables in his research that he might not have thought about.

Why is reviewing literature crucial in the research process?

Reviewing literature helps avoid duplicating previous work, discovers what others have learned about the problem, familiarizes the researcher with relevant concepts and theories, and ensures a comprehensive approach to the research question.

What is the significance of reviewing literature in the research process?

Reviewing relevant literature helps formulate the problem, understand the background of the study, choose a proper research methodology, and develop coherence between the study’s results and previous findings.

Setting Research Questions, Objectives, and Hypotheses

After discovering and defining the research problem, researchers should make a formal statement of the problem leading to research objectives .

An objective will precisely say what should be researched, delineate the type of information that should be collected, and provide a framework for the scope of the study. A well-formulated, testable research hypothesis is the best expression of a research objective.

A hypothesis is an unproven statement or proposition that can be refuted or supported by empirical data. Hypothetical statements assert a possible answer to a research question.

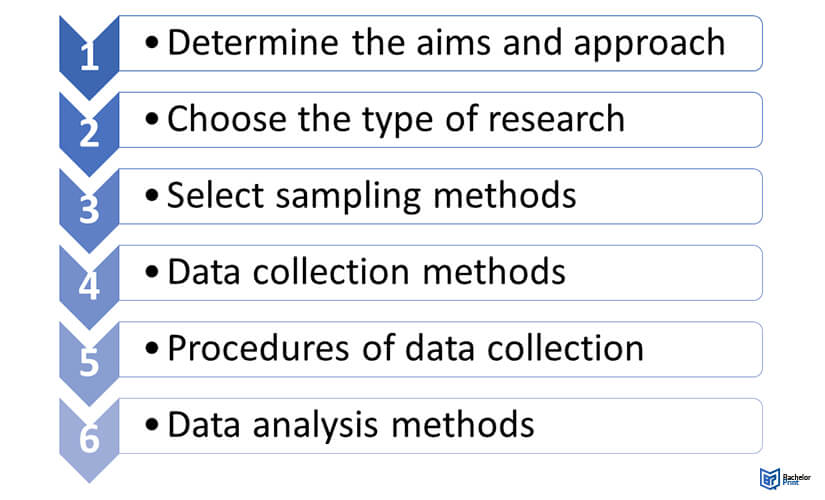

Step #4: Choosing the Study Design

The research design is the blueprint or framework for fulfilling objectives and answering research questions .

It is a master plan specifying the methods and procedures for collecting, processing, and analyzing the collected data. There are four basic research designs that a researcher can use to conduct their study;

- experiment,

- secondary data study, and

- observational study.

The type of research design to be chosen from among the above four methods depends primarily on four factors:

- The type of problem

- The objectives of the study,

- The existing state of knowledge about the problem that is being studied, and

- The resources are available for the study.

Deciding on the Sample Design

Sampling is an important and separate step in the research process. The basic idea of sampling is that it involves any procedure that uses a relatively small number of items or portions (called a sample) of a universe (called population) to conclude the whole population.

It contrasts with the process of complete enumeration, in which every member of the population is included.

Such a complete enumeration is referred to as a census.

A population is the total collection of elements we wish to make some inference or generalization.

A sample is a part of the population, carefully selected to represent that population. If certain statistical procedures are followed in selecting the sample, it should have the same characteristics as the population. These procedures are embedded in the sample design.

Sample design refers to the methods followed in selecting a sample from the population and the estimating technique vis-a-vis the formula for computing the sample statistics.

The fundamental question is, then, how to select a sample.

To answer this question, we must have acquaintance with the sampling methods.

These methods are basically of two types;

- probability sampling , and

- non-probability sampling .

Probability sampling ensures every unit has a known nonzero probability of selection within the target population.

If there is no feasible alternative, a non-probability sampling method may be employed.

The basis of such selection is entirely dependent on the researcher’s discretion. This approach is called judgment sampling, convenience sampling, accidental sampling, and purposive sampling.

The most widely used probability sampling methods are simple random sampling , stratified random sampling , cluster sampling , and systematic sampling . They have been classified by their representation basis and unit selection techniques.

Two other variations of the sampling methods that are in great use are multistage sampling and probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling .

Multistage sampling is most commonly used in drawing samples from very large and diverse populations.

The PPS sampling is a variation of multistage sampling in which the probability of selecting a cluster is proportional to its size, and an equal number of elements are sampled within each cluster.

Collecting Data From The Research Sample

Data gathering may range from simple observation to a large-scale survey in any defined population. There are many ways to collect data. The approach selected depends on the objectives of the study, the research design, and the availability of time, money, and personnel.

With the variation in the type of data (qualitative or quantitative) to be collected, the method of data collection also varies .

The most common means for collecting quantitative data is the structured interview .

Studies that obtain data by interviewing respondents are called surveys. Data can also be collected by using self-administered questionnaires . Telephone interviewing is another way in which data may be collected .

Other means of data collection include secondary sources, such as the census, vital registration records, official documents, previous surveys, etc.

Qualitative data are collected mainly through in-depth interviews, focus group discussions , Key Informant Interview ( KII), and observational studies.

Process and Analyze the Collected Research Data

Data processing generally begins with the editing and coding of data . Data are edited to ensure consistency across respondents and to locate omissions if any.

In survey data, editing reduces errors in the recording, improves legibility, and clarifies unclear and inappropriate responses. In addition to editing, the data also need coding.

Because it is impractical to place raw data into a report, alphanumeric codes are used to reduce the responses to a more manageable form for storage and future processing.

This coding process facilitates the processing of the data. The personal computer offers an excellent opportunity for data editing and coding processes.

Data analysis usually involves reducing accumulated data to a manageable size, developing summaries, searching for patterns, and applying statistical techniques for understanding and interpreting the findings in light of the research questions.

Further, based on his analysis, the researcher determines if his findings are consistent with the formulated hypotheses and theories.

The techniques used in analyzing data may range from simple graphical techniques to very complex multivariate analyses depending on the study’s objectives, the research design employed, and the nature of the data collected.

As in the case of data collection methods, an analytical technique appropriate in one situation may not be suitable for another.

Writing Research Report – Developing Research Proposal, Writing Report, Disseminating and Utilizing Results

The entire task of a research study is accumulated in a document called a proposal or research proposal.

A research proposal is a work plan, prospectus, outline, offer, and a statement of intent or commitment from an individual researcher or an organization to produce a product or render a service to a potential client or sponsor .

The proposal will be prepared to keep the sequence presented in the research process. The proposal tells us what, how, where, and to whom it will be done.

It must also show the benefit of doing it. It always includes an explanation of the purpose of the study (the research objectives) or a definition of the problem.

It systematically outlines the particular research methodology and details the procedures utilized at each stage of the research process.

The end goal of a scientific study is to interpret the results and draw conclusions.

To this end, it is necessary to prepare a report and transmit the findings and recommendations to administrators, policymakers, and program managers to make a decision.

There are various research reports: term papers, dissertations, journal articles , papers for presentation at professional conferences and seminars, books, thesis, and so on. The results of a research investigation prepared in any form are of little utility if they are not communicated to others.

The primary purpose of a dissemination strategy is to identify the most effective media channels to reach different audience groups with study findings most relevant to their needs.

The dissemination may be made through a conference, a seminar, a report, or an oral or poster presentation.

The style and organization of the report will differ according to the target audience, the occasion, and the purpose of the research. Reports should be developed from the client’s perspective.

A report is an excellent means that helps to establish the researcher’s credibility. At a bare minimum, a research report should contain sections on:

- An executive summary;

- Background of the problem;

- Literature review;

- Methodology;

- Discussion;

- Conclusions and

- Recommendations.

The study results can also be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals published by academic institutions and reputed publishers both at home and abroad. The report should be properly evaluated .

These journals have their format and editorial policies. The contributors can submit their manuscripts adhering to the policies and format for possible publication of their papers.

There are now ample opportunities for researchers to publish their work online.

The researchers have conducted many interesting studies without affecting actual settings. Ideally, the concluding step of a scientific study is to plan for its utilization in the real world.

Although researchers are often not in a position to implement a plan for utilizing research findings, they can contribute by including in their research reports a few recommendations regarding how the study results could be utilized for policy formulation and program intervention.

Why is the dissemination of research findings important?

Dissemination of research findings is crucial because the results of a research investigation have little utility if not communicated to others. Dissemination ensures that the findings reach relevant stakeholders, policymakers, and program managers to inform decisions.

How should a research report be structured?

A research report should contain sections on an executive summary, background of the problem, literature review, methodology, findings, discussion, conclusions, and recommendations.

Why is it essential to consider the target audience when preparing a research report?

The style and organization of a research report should differ based on the target audience, occasion, and research purpose. Tailoring the report to the audience ensures that the findings are communicated effectively and are relevant to their needs.

Key Steps in the Research Process - A Comprehensive Guide

Embarking on a research journey can be both thrilling and challenging. Whether you're a student, journalist, or simply inquisitive about a subject, grasping the research process steps is vital for conducting thorough and efficient research. In this all-encompassing guide, we'll navigate you through the pivotal stages of what is the research process, from pinpointing your topic to showcasing your discoveries.

We'll delve into how to formulate a robust research question, undertake preliminary research, and devise a structured research plan. You'll acquire strategies for gathering and scrutinizing data, along with advice for effectively disseminating your findings. By adhering to these steps in the research process, you'll be fully prepared to confront any research endeavor that presents itself.

Step 1: Identify and Develop Your Topic

Identifying and cultivating a research topic is the foundational first step in the research process. Kick off by brainstorming potential subjects that captivate your interest, as this will fuel your enthusiasm throughout the endeavor.

Employ the following tactics to spark ideas and understand what is the first step in the research process:

- Review course materials, lecture notes, and assigned readings for inspiration

- Engage in discussions with peers, professors, or experts in the field

- Investigate current events, news pieces, or social media trends pertinent to your field of study to uncover valuable market research insights.

- Reflect on personal experiences or observations that have sparked your curiosity

Once you've compiled a roster of possible topics, engage in preliminary research to evaluate the viability and breadth of each concept. This initial probe may encompass various research steps and procedures to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topics at hand.

- Scanning Wikipedia articles or other general reference sources for an overview

- Searching for scholarly articles, books, or media related to your topic

- Identifying key concepts, theories, or debates within the field

- Considering the availability of primary sources or data for analysis

While amassing background knowledge, begin to concentrate your focus and hone your topic. Target a subject that is specific enough to be feasible within your project's limits, yet expansive enough to permit substantial analysis. Mull over the following inquiries to steer your topic refinement and address the research problem effectively:

- What aspect of the topic am I most interested in exploring?

- What questions or problems related to this topic remain unanswered or unresolved?

- How can I contribute new insights or perspectives to the existing body of knowledge?

- What resources and methods will I need to investigate this topic effectively?

Step 2: Conduct Preliminary Research

Having pinpointed a promising research topic, it's time to plunge into preliminary research. This essential phase enables you to deepen your grasp of the subject and evaluate the practicality of your project. Here are some pivotal tactics for executing effective preliminary research using various library resources:

- Literature Review

To effectively embark on your scholarly journey, it's essential to consult a broad spectrum of sources, thereby enriching your understanding with the breadth of academic research available on your topic. This exploration may encompass a variety of materials.

- Online catalogs of libraries (local, regional, national, and special)

- Meta-catalogs and subject-specific online article databases

- Digital institutional repositories and open access resources

- Works cited in scholarly books and articles

- Print bibliographies and internet sources

- Websites of major nonprofit organizations, research institutes, museums, universities, and government agencies

- Trade and scholarly publishers

- Discussions with fellow scholars and peers

- Identify Key Debates

Engaging with the wealth of recently published materials and seminal works in your field is a pivotal part of the research process definition. Focus on discerning the core ideas, debates, and arguments that define your topic, which will in turn sharpen your research focus and guide you toward formulating pertinent research questions.

- Narrow Your Focus

Hone your topic by leveraging your initial findings to tackle a specific issue or facet within the larger subject, a fundamental step in the research process steps. Consider various factors that could influence the direction and scope of your inquiry.

- Subtopics and specific issues

- Key debates and controversies

- Timeframes and geographical locations

- Organizations or groups of people involved

A thorough evaluation of existing literature and a comprehensive assessment of the information at hand will pinpoint the exact dimensions of the issue you aim to explore. This methodology ensures alignment with prior research, optimizes resources, and can bolster your case when seeking research funding by demonstrating a well-founded approach.

Step 3: Establish Your Research Question

Having completed your preliminary research and topic refinement, the next vital phase involves formulating a precise and focused research question. This question, a cornerstone among research process steps, will steer your investigation, keeping it aligned with relevant data and insights. When devising your research question, take into account these critical factors:

Initiate your inquiry by defining the requirements and goals of your study, a key step in the research process steps. Whether you're testing a hypothesis, analyzing data, or constructing and supporting an argument, grasping the intent of your research is crucial for framing your question effectively.

Ensure that your research question is feasible, given your constraints in time and word count, an important consideration in the research process steps. Steer clear of questions that are either too expansive or too constricted, as they may impede your capacity to conduct a comprehensive analysis.

Your research question should transcend a mere 'yes' or 'no' response, prompting a thorough engagement with the research process steps. It should foster a comprehensive exploration of the topic, facilitating the analysis of issues or problems beyond just a basic description.

- Researchability

Ensure that your research question opens the door to quality research materials, including academic books and refereed journal articles. It's essential to weigh the accessibility of primary data and secondary data that will bolster your investigative efforts.

When establishing your research question, take the following steps:

- Identify the specific aspect of your general topic that you want to explore

- Hypothesize the path your answer might take, developing a hypothesis after formulating the question

- Steer clear of certain types of questions in your research process steps, such as those that are deceptively simple, fictional, stacked, semantic, impossible-to-answer, opinion or ethical, and anachronistic, to maintain the integrity of your inquiry.

- Conduct a self-test on your research question to confirm it adheres to the research process steps, ensuring it is flexible, testable, clear, precise, and underscores a distinct reason for its importance.

By meticulously formulating your research question, you're establishing a solid groundwork for the subsequent research process steps, guaranteeing that your efforts are directed, efficient, and yield productive outcomes.

Step 4: Develop a Research Plan

Having formulated a precise research question, the ensuing phase involves developing a detailed research plan. This plan, integral to the research process steps, acts as a navigational guide for your project, keeping you organized, concentrated, and on a clear path to accomplishing your research objectives. When devising your research plan, consider these pivotal components:

- Project Goals and Objectives

Articulate the specific aims and objectives of your research project with clarity. These should be in harmony with your research question and provide a structured framework for your investigation, ultimately aligning with your overarching business goals.

- Research Methods

Select the most appropriate research tools and statistical methods to address your question effectively. This may include a variety of qualitative and quantitative approaches to ensure comprehensive analysis.

- Quantitative methods (e.g., surveys, experiments)

- Qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, focus groups)

- Mixed methods (combining quantitative and qualitative approaches)

- Access to databases, archives, or special collections

- Specialized equipment or software

- Funding for travel, materials, or participant compensation

- Assistance from research assistants, librarians, or subject matter experts

- Participant Recruitment

If your research involves human subjects, develop a strategic plan for recruiting participants. Consider factors such as the inclusion of diverse ethnic groups and the use of user interviews to gather rich, qualitative data.

- Target population and sample size

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Recruitment strategies (e.g., flyers, social media, snowball sampling)

- Informed consent procedures

- Instruments or tools for gathering data (e.g., questionnaires, interview guides)

- Data storage and management protocols

- Statistical or qualitative analysis techniques

- Software or tools for data analysis (e.g., SPSS, NVivo)

Create a realistic project strategy for your research project, breaking it down into manageable stages or milestones. Consider factors such as resource availability and potential bottlenecks.

- Literature review and background research

- IRB approval (if applicable)

- Participant recruitment and data collection

- Data analysis and interpretation

- Writing and revising your findings

- Dissemination of results (e.g., presentations, publications)

By developing a comprehensive research plan, incorporating key research process steps, you'll be better equipped to anticipate challenges, allocate resources effectively, and ensure the integrity and rigor of your research process. Remember to remain flexible and adaptable to navigate unexpected obstacles or opportunities that may arise.

Step 5: Conduct the Research

With your research plan in place, it's time to dive into the data collection phase. As you conduct your research, adhere to the established research process steps to ensure the integrity and quality of your findings.

Conduct your research in accordance with federal regulations, state laws, institutional SOPs, and policies. Familiarize yourself with the IRB-approved protocol and follow it diligently, as part of the essential research process steps.

- Roles and Responsibilities

Understand and adhere to the roles and responsibilities of the principal investigator and other research team members. Maintain open communication lines with all stakeholders, including the sponsor and IRB, to foster cross-functional collaboration.

- Data Management

Develop and maintain an effective system for data collection and storage, utilizing advanced research tools. Ensure that each member of the research team has seamless access to the most up-to-date documents, including the informed consent document, protocol, and case report forms.

- Quality Assurance

Implement comprehensive quality assurance measures to verify that the study adheres strictly to the IRB-approved protocol, institutional policy, and all required regulations. Confirm that all study activities are executed as planned and that any deviations are addressed with precision and appropriateness.

- Participant Eligibility

As part of the essential research process steps, verify that potential study subjects meet all eligibility criteria and none of the ineligibility criteria before advancing with the research.

To maintain the highest standards of academic integrity and ethical conduct:

- Conduct research with unwavering honesty in all facets, including experimental design, data generation, and analysis, as well as the publication of results, as these are critical research process steps.

- Maintain a climate conducive to conducting research in strict accordance with good research practices, ensuring each step of the research process is meticulously observed.

- Provide appropriate supervision and training for researchers.

- Encourage open discussion of ideas and the widest dissemination of results possible.

- Keep clear and accurate records of research methods and results.

- Exercise a duty of care to all those involved in the research.

When collecting and assimilating data:

- Use professional online data analysis tools to streamline the process.

- Use metadata for context

- Assign codes or labels to facilitate grouping or comparison

- Convert data into different formats or scales for compatibility

- Organize documents in both the study participant and investigator's study regulatory files, creating a central repository for easy access and reference, as this organization is a pivotal step in the research process.

By adhering to these guidelines and upholding a commitment to ethical and rigorous research practices, you'll be well-equipped to conduct your research effectively and contribute meaningful insights to your field of study, thereby enhancing the integrity of the research process steps.

Step 6: Analyze and Interpret Data

Embarking on the research process steps, once you have gathered your research data, the subsequent critical phase is to delve into analysis and interpretation. This stage demands a meticulous examination of the data, spotting trends, and forging insightful conclusions that directly respond to your research question. Reflect on these tactics for a robust approach to data analysis and interpretation:

- Organize and Clean Your Data

A pivotal aspect of the research process steps is to start by structuring your data in an orderly and coherent fashion. This organizational task may encompass:

- Creating a spreadsheet or database to store your data

- Assigning codes or labels to facilitate grouping or comparison

- Cleaning the data by removing any errors, inconsistencies, or missing values

- Converting data into different formats or scales for compatibility

- Calculating measures of central tendency (mean, median, mode)

- Determining measures of variability (range, standard deviation)

- Creating frequency tables or histograms to visualize the distribution of your data

- Identifying any outliers or unusual patterns in your data

- Perform Inferential Analysis

Integral to the research process steps, you might engage in inferential analysis to evaluate hypotheses or extrapolate findings to a broader demographic, contingent on your research design and query. This analytical step may include:

- Selecting appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis)

- As part of the research process steps, establishing a significance threshold (e.g., p < 0.05) is essential to gauge the likelihood of your results being a random occurrence rather than a significant finding.

- Interpreting the results of your statistical tests in the context of your research question

- Considering the practical significance of your findings, in addition to statistical significance

When interpreting your data, it's essential to:

- Look for relationships, patterns, and trends in your data

- Consider alternative explanations for your findings

- Acknowledge any limitations or potential biases in your research design or data collection

- Leverage data visualization techniques such as graphs, charts, and infographics to articulate your research findings with clarity and impact, thereby enhancing the communicative value of your data.

- Seek feedback from peers, mentors, or subject matter experts to validate your interpretations

It's important to recognize that data interpretation is a cyclical process that hinges on critical thinking, inventiveness, and the readiness to refine your conclusions with emerging insights. By tackling data analysis and interpretation with diligence and openness, you're setting the stage to derive meaningful and justifiable inferences from your research, in line with the research process steps.

Step 7: Present the Findings

After meticulous analysis and interpretation of your research findings, as dictated by the research process steps, the moment arrives to disseminate your insights. Effectively presenting your research is key to captivating your audience and conveying the importance of your findings. Employ these strategies to create an engaging and persuasive presentation:

- Organize Your Findings :

Use the PEEL method to structure your presentation:

- Point: Clearly state your main argument or finding

- Evidence: Present the data and analysis that support your point

- Explanation: Provide context and interpret the significance of your evidence

- Link: Connect your findings to the broader research question or field

- Tailor Your Message

Understanding your audience is crucial to effective communication. When presenting your research, it's important to tailor your message to their background, interests, and level of expertise, effectively employing user personas to guide your approach.

- Use clear, concise language and explain technical terms

- Highlight what makes your research unique and impactful

- Craft a compelling narrative with a clear structure and hook

- Share the big picture, emphasizing the significance of your findings

- Engage Your Audience : Make your presentation enjoyable and memorable by incorporating creative elements:

- Use visual aids, such as tables, charts, and graphs, to communicate your findings effectively

- To vividly convey your research journey, consider employing storytelling techniques, such as UX comics or storyboards, which can make complex information more accessible and engaging.

- Injecting humor and personality into your presentation can be a powerful tool for communication. Utilize funny messages or GIFs to lighten the mood, breaking up tension and refocusing attention, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of humor in communication.

By adhering to these strategies, you'll be well-prepared to present your research findings in a manner that's both clear and captivating. Ensure you follow research process steps such as citing your sources accurately and discussing the broader implications of your work, providing actionable recommendations, and delineating the subsequent phases for integrating your findings into broader practice or policy frameworks.

The research process is an intricate journey that demands meticulous planning, steadfast execution, and incisive analysis. By adhering to the fundamental research process steps outlined in this guide, from pinpointing your topic to showcasing your findings, you're setting yourself up for conducting research that's both effective and influential. Keep in mind that the research journey is iterative, often necessitating revisits to certain stages as fresh insights surface or unforeseen challenges emerge.

As you commence your research journey, seize the chance to contribute novel insights to your field and forge a positive global impact. By tackling your research with curiosity, integrity, and a dedication to excellence, you're paving the way towards attaining your research aspirations and making a substantial difference with your work, all while following the critical research process steps.

Sign up for more like this.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Table of Contents

Research Process

Definition:

Research Process is a systematic and structured approach that involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or information to answer a specific research question or solve a particular problem.

Research Process Steps

Research Process Steps are as follows:

Identify the Research Question or Problem

This is the first step in the research process. It involves identifying a problem or question that needs to be addressed. The research question should be specific, relevant, and focused on a particular area of interest.

Conduct a Literature Review

Once the research question has been identified, the next step is to conduct a literature review. This involves reviewing existing research and literature on the topic to identify any gaps in knowledge or areas where further research is needed. A literature review helps to provide a theoretical framework for the research and also ensures that the research is not duplicating previous work.

Formulate a Hypothesis or Research Objectives

Based on the research question and literature review, the researcher can formulate a hypothesis or research objectives. A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested to determine its validity, while research objectives are specific goals that the researcher aims to achieve through the research.

Design a Research Plan and Methodology

This step involves designing a research plan and methodology that will enable the researcher to collect and analyze data to test the hypothesis or achieve the research objectives. The research plan should include details on the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used.

Collect and Analyze Data

This step involves collecting and analyzing data according to the research plan and methodology. Data can be collected through various methods, including surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The data analysis process involves cleaning and organizing the data, applying statistical and analytical techniques to the data, and interpreting the results.

Interpret the Findings and Draw Conclusions

After analyzing the data, the researcher must interpret the findings and draw conclusions. This involves assessing the validity and reliability of the results and determining whether the hypothesis was supported or not. The researcher must also consider any limitations of the research and discuss the implications of the findings.

Communicate the Results

Finally, the researcher must communicate the results of the research through a research report, presentation, or publication. The research report should provide a detailed account of the research process, including the research question, literature review, research methodology, data analysis, findings, and conclusions. The report should also include recommendations for further research in the area.

Review and Revise

The research process is an iterative one, and it is important to review and revise the research plan and methodology as necessary. Researchers should assess the quality of their data and methods, reflect on their findings, and consider areas for improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Throughout the research process, ethical considerations must be taken into account. This includes ensuring that the research design protects the welfare of research participants, obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality and privacy, and avoiding any potential harm to participants or their communities.

Dissemination and Application

The final step in the research process is to disseminate the findings and apply the research to real-world settings. Researchers can share their findings through academic publications, presentations at conferences, or media coverage. The research can be used to inform policy decisions, develop interventions, or improve practice in the relevant field.

Research Process Example

Following is a Research Process Example:

Research Question : What are the effects of a plant-based diet on athletic performance in high school athletes?

Step 1: Background Research Conduct a literature review to gain a better understanding of the existing research on the topic. Read academic articles and research studies related to plant-based diets, athletic performance, and high school athletes.

Step 2: Develop a Hypothesis Based on the literature review, develop a hypothesis that a plant-based diet positively affects athletic performance in high school athletes.

Step 3: Design the Study Design a study to test the hypothesis. Decide on the study population, sample size, and research methods. For this study, you could use a survey to collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance from a sample of high school athletes who follow a plant-based diet and a sample of high school athletes who do not follow a plant-based diet.

Step 4: Collect Data Distribute the survey to the selected sample and collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance.

Step 5: Analyze Data Use statistical analysis to compare the data from the two samples and determine if there is a significant difference in athletic performance between those who follow a plant-based diet and those who do not.

Step 6 : Interpret Results Interpret the results of the analysis in the context of the research question and hypothesis. Discuss any limitations or potential biases in the study design.

Step 7: Draw Conclusions Based on the results, draw conclusions about whether a plant-based diet has a significant effect on athletic performance in high school athletes. If the hypothesis is supported by the data, discuss potential implications and future research directions.

Step 8: Communicate Findings Communicate the findings of the study in a clear and concise manner. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that the findings are understood and valued.

Applications of Research Process

The research process has numerous applications across a wide range of fields and industries. Some examples of applications of the research process include:

- Scientific research: The research process is widely used in scientific research to investigate phenomena in the natural world and develop new theories or technologies. This includes fields such as biology, chemistry, physics, and environmental science.

- Social sciences : The research process is commonly used in social sciences to study human behavior, social structures, and institutions. This includes fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, and economics.

- Education: The research process is used in education to study learning processes, curriculum design, and teaching methodologies. This includes research on student achievement, teacher effectiveness, and educational policy.

- Healthcare: The research process is used in healthcare to investigate medical conditions, develop new treatments, and evaluate healthcare interventions. This includes fields such as medicine, nursing, and public health.

- Business and industry : The research process is used in business and industry to study consumer behavior, market trends, and develop new products or services. This includes market research, product development, and customer satisfaction research.

- Government and policy : The research process is used in government and policy to evaluate the effectiveness of policies and programs, and to inform policy decisions. This includes research on social welfare, crime prevention, and environmental policy.

Purpose of Research Process

The purpose of the research process is to systematically and scientifically investigate a problem or question in order to generate new knowledge or solve a problem. The research process enables researchers to:

- Identify gaps in existing knowledge: By conducting a thorough literature review, researchers can identify gaps in existing knowledge and develop research questions that address these gaps.

- Collect and analyze data : The research process provides a structured approach to collecting and analyzing data. Researchers can use a variety of research methods, including surveys, experiments, and interviews, to collect data that is valid and reliable.

- Test hypotheses : The research process allows researchers to test hypotheses and make evidence-based conclusions. Through the systematic analysis of data, researchers can draw conclusions about the relationships between variables and develop new theories or models.

- Solve problems: The research process can be used to solve practical problems and improve real-world outcomes. For example, researchers can develop interventions to address health or social problems, evaluate the effectiveness of policies or programs, and improve organizational processes.

- Generate new knowledge : The research process is a key way to generate new knowledge and advance understanding in a given field. By conducting rigorous and well-designed research, researchers can make significant contributions to their field and help to shape future research.

Tips for Research Process

Here are some tips for the research process:

- Start with a clear research question : A well-defined research question is the foundation of a successful research project. It should be specific, relevant, and achievable within the given time frame and resources.

- Conduct a thorough literature review: A comprehensive literature review will help you to identify gaps in existing knowledge, build on previous research, and avoid duplication. It will also provide a theoretical framework for your research.

- Choose appropriate research methods: Select research methods that are appropriate for your research question, objectives, and sample size. Ensure that your methods are valid, reliable, and ethical.

- Be organized and systematic: Keep detailed notes throughout the research process, including your research plan, methodology, data collection, and analysis. This will help you to stay organized and ensure that you don’t miss any important details.

- Analyze data rigorously: Use appropriate statistical and analytical techniques to analyze your data. Ensure that your analysis is valid, reliable, and transparent.

- I nterpret results carefully : Interpret your results in the context of your research question and objectives. Consider any limitations or potential biases in your research design, and be cautious in drawing conclusions.

- Communicate effectively: Communicate your research findings clearly and effectively to your target audience. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that your findings are understood and valued.

- Collaborate and seek feedback : Collaborate with other researchers, experts, or stakeholders in your field. Seek feedback on your research design, methods, and findings to ensure that they are relevant, meaningful, and impactful.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

- Research Guides

6 Stages of Research

- 1: Task Definition

- 2: Information Seeking

- 3: Location & Access

- 4: Use of Information

- 5: Synthesis

- 6: Evaluation

Ask a Librarian

Browse our FAQ, Chat Live with a Librarian, Call, Text, Email, or Make an Appointment.

We are here to help!

Ask the Right Questions

The scope of an investigation determines how large or small your investigation will be. Determining the scope of an investigation is the critical first step in the research process because you will know how far and how deep to look for answers. This lesson will teach you how to develop a research question as a way to determine the scope of an investigation.

Click the image to open the tutorial in a new window.

Keyword(s): 5W Criteria, Ask the Right Questions, Guided Inquiry, Information Literacy, Library, New Literacies Alliance, Research as Inquiry, Research Question

Purpose of this guide

The purpose of this guide is to walk you through the 6 stages of writing an effective research paper. By breaking the process down into these 6 stages, your paper will be better and you will get more out of the research experience.

The 6 stages are:

- Task Definition (developing a topic)

- Information Seeking (coming up with a research plan)

- Location & Access (finding good sources)

- Use of Information (Reading, taking notes, and generally making the writing process easier)

- Synthesis (coming up with your own ideas and presenting them well)

- Evaluation (reflection)

This research guide is based on the Big6 Information Literacy model from https://thebig6.org/

Task Definition

The purpose of task definition is to help you develop an effective topic for your paper. .

Developing a topic is often one of the hardest and most important steps in writing a paper or doing a research project. But here are some tips:

- A research topic is a question, not a statement. You shouldn't already know the answer when you start researching.

- Research something you actually care about or find interesting. It turns the research process from a chore into something enjoyable and whoever reads your work can tell the difference.

- Read the assignment before and after you think you have come up with your topic to make sure you are answering the prompt.

Steps to Developing a Topic

- Assignment Requirements

- General Idea

- Background Research

- Ask Questions

- Topic Question

Read your assignment and note any requirements.

- Is there a required page length?

- How many sources do you need?

- Does the paper have to be in a specific format like APA?

- Are there any listed goals for the topic, such as synthesizing different opinions, or applying a theory to a real-life example?

Formulate a general idea.

- Look at your syllabus or course schedule for broad topic ideas.

- Think about reading assignments or class lectures that you found interesting.

- Talk with your professor or a librarian.

- Check out social media and see what has been trending that is related to your course.

- Think about ideas from popular videos, TV shows, and movies.

- Read The New York Times (FHSU students have free access through the Library)

- Watch NBC Learn (FHSU students have free access through the Library)

- Search your library for relevant journals and publications related to your course and browse them for ideas

- Browse online discussion forums, news, and blogs for professional organizations for hot topics

Do some background research on your general idea.

- You have access to reference materials through the Library for background research.

- See what your course notes and textbook say about the subject.

- Google it.

Reference e-books on a wide range of topics. Sources include dictionaries, encyclopedias, key concepts, key thinkers, handbooks, atlases, and more. Search by keyword or browse titles by topic.

Over 1200 cross-searchable reference e-books on a wide variety of subjects.

Mind map it.

A mind map is an effective way of organizing your thoughts and generating new questions as you learn about your topic.

- Video on how to do a mind map.

- Coggle Free mind mapping software that is great for beginners and easy to use.

- MindMup Mindmup is a free, easy to use online software that allows you to publish and share your mind maps with others.

Ask Questions to focus on what interests you.

Who? What? When? Where? Why?

We can focus our ideas by brainstorming what interests us when asking who, what, when where, and why:

Research Question: Does flexible seating in an elementary classroom improve student focus?

Write out your topic question & reread the assignment criteria.

- Can you answer your question well in the number of pages required?

- Does your topic still meet the requirements of the paper? Ex: is the question still about the sociology of gender studies and women?

- Is the topic too narrow to find research?

Developing a Topic Tutorial

The following tutorial from Forsyth Library will walk you through the process of defining your topic.

- Next: 2: Information Seeking >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 2:43 PM

- URL: https://fhsuguides.fhsu.edu/6stages

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3 The research process

In Chapter 1, we saw that scientific research is the process of acquiring scientific knowledge using the scientific method. But how is such research conducted? This chapter delves into the process of scientific research, and the assumptions and outcomes of the research process.

Paradigms of social research

Our design and conduct of research is shaped by our mental models, or frames of reference that we use to organise our reasoning and observations. These mental models or frames (belief systems) are called paradigms . The word ‘paradigm’ was popularised by Thomas Kuhn (1962) [1] in his book The structure of scientific r evolutions , where he examined the history of the natural sciences to identify patterns of activities that shape the progress of science. Similar ideas are applicable to social sciences as well, where a social reality can be viewed by different people in different ways, which may constrain their thinking and reasoning about the observed phenomenon. For instance, conservatives and liberals tend to have very different perceptions of the role of government in people’s lives, and hence, have different opinions on how to solve social problems. Conservatives may believe that lowering taxes is the best way to stimulate a stagnant economy because it increases people’s disposable income and spending, which in turn expands business output and employment. In contrast, liberals may believe that governments should invest more directly in job creation programs such as public works and infrastructure projects, which will increase employment and people’s ability to consume and drive the economy. Likewise, Western societies place greater emphasis on individual rights, such as one’s right to privacy, right of free speech, and right to bear arms. In contrast, Asian societies tend to balance the rights of individuals against the rights of families, organisations, and the government, and therefore tend to be more communal and less individualistic in their policies. Such differences in perspective often lead Westerners to criticise Asian governments for being autocratic, while Asians criticise Western societies for being greedy, having high crime rates, and creating a ‘cult of the individual’. Our personal paradigms are like ‘coloured glasses’ that govern how we view the world and how we structure our thoughts about what we see in the world.