- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

Drug Abuse, Addiction, Substance Use Disorder

- Research Drug Abuse

Start Learning About Your Topic

Create research questions to focus your topic, find books in the library catalog, find articles in library databases, find web resources, cite your sources, key search words.

Use the words below to search for useful information in books and articles .

- substance use disorder

- substance abuse

- drug addiction

- substance addiction

- chemical dependency

- war on drugs

- names of specific drugs such as methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin

- opioid crisis

Background Reading:

It's important to begin your research learning something about your subject; in fact, you won't be able to create a focused, manageable thesis unless you already know something about your topic.

This step is important so that you will:

- Begin building your core knowledge about your topic

- Be able to put your topic in context

- Create research questions that drive your search for information

- Create a list of search terms that will help you find relevant information

- Know if the information you’re finding is relevant and useful

If you're working from off campus , you'll be prompted to log in just like you do for your MJC email or Canvas courses.

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- Gale eBooks This link opens in a new window Use this database for preliminary reading as you start your research. Try searching these terms: addiction, substance abuse

Other eBooks from the MJC Library collection:

Use some of the questions below to help you narrow this broad topic. See "substance abuse" in our Developing Research Questions guide for an example of research questions on a focused study of drug abuse.

- In what ways is drug abuse a serious problem?

- What drugs are abused?

- Who abuses drugs?

- What causes people to abuse drugs?

- How do drug abusers' actions affect themselves, their families, and their communities?

- What resources and treatment are available to drug abusers?

- What are the laws pertaining to drug use?

- What are the arguments for legalizing drugs?

- What are the arguments against legalizing drugs?

- Is drug abuse best handled on a personal, local, state or federal level?

- Based on what I have learned from my research what do I think about the issue of drug abuse?

Why Use Books:

Use books to read broad overviews and detailed discussions of your topic. You can also use books to find primary sources , which are often published together in collections.

Where Do I Find Books?

You'll use the library catalog to search for books, ebooks, articles, and more.

What if MJC Doesn't Have What I Need?

If you need materials (books, articles, recordings, videos, etc.) that you cannot find in the library catalog , use our interlibrary loan service .

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- EBSCOhost Databases This link opens in a new window Search 22 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. EBSCO databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Gale Databases This link opens in a new window Search over 35 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. Gale databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection This link opens in a new window Contains articles from nearly 560 scholarly journals, some dating as far back as 1965

- Access World News This link opens in a new window Search the full-text of editions of record for local, regional, and national U.S. newspapers as well as full-text content of key international sources. This is your source for The Modesto Bee from January 1989 to the present. Also includes in-depth special reports and hot topics from around the country. To access The Modesto Bee , limit your search to that publication. more... less... Watch this short video to learn how to find The Modesto Bee .

Use Google Scholar to find scholarly literature on the Web:

Browse Featured Web Sites:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse NIDA's mission is to lead the nation in bringing the power of science to bear on drug abuse and addiction. This charge has two critical components. The first is the strategic support and conduct of research across a broad range of disciplines. The second is ensuring the rapid and effective dissemination and use of the results of that research to significantly improve prevention and treatment and to inform policy as it relates to drug abuse and addiction.

- Drug Free America Foundation Drug Free America Foundation, Inc. is a drug prevention and policy organization committed to developing, promoting and sustaining national and international policies and laws that will reduce illegal drug use and drug addiction.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy A component of the Executive Office of the President, ONDCP was created by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988. ONDCP advises the President on drug-control issues, coordinates drug-control activities and related funding across the Federal government, and produces the annual National Drug Control Strategy, which outlines Administration efforts to reduce illicit drug use, manufacturing and trafficking, drug-related crime and violence, and drug-related health consequences.

- Drug Policy Alliance The Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) is the nation's leading organization promoting alternatives to current drug policy that are grounded in science, compassion, health and human rights.

Your instructor should tell you which citation style they want you to use. Click on the appropriate link below to learn how to format your paper and cite your sources according to a particular style.

- Chicago Style

- ASA & Other Citation Styles

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2024 2:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/drugabuse

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, insights into mechanisms related to cocaine addiction using a novel imaging method for dopamine neurons, treatment implications of understanding brain function during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder, relatively low amounts of alcohol intake during pregnancy are associated with subtle neurodevelopmental effects in preadolescent offspring, increased comorbidity between substance use and psychiatric disorders in sexual identity minorities, trends in nicotine use and dependence from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013, conclusions, information, published in.

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

Competing Interests

Export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

NEXT ARTICLE

Request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

RANKING EVIDENCE IN SUBSTANCE USE AND ADDICTION

Hudson reddon.

1. British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 1045 Howe Street, Vancouver, BC V6Z 2A9, Canada

2. CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network, 588-1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, BC V6B 3E6, Canada

Thomas Kerr

3. Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, St. Paul’s Hospital, 1081 Burrard St, Vancouver, BC V6Z 1Y6, Canada

Hudson Reddon: Writing-Original draft, Writing-Review and Editing Thomas Kerr: Writing-Review and Editing M-J Milloy: Writing-Review and Editing

Evidence-based medicine has consistently prized the epistemological value of randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) owing to their methodological advantages over alternative designs such as observational studies. However, there are limitations to RCTs that hinder their ability to study chronic and dynamic conditions such as substance use and addiction. For these conditions, observational studies may provide superior evidence based on methodological and practical strengths. Assuming epistemic superiority of RCTs has led to an inappropriate devaluation of other study designs and the findings they support, including support for harm reduction services, especially needle exchange programs and supervised injection facilities. The value offered by observational studies should be reflected in evidence-based medicine by allowing more flexibility in evidence hierarchies that presume methodological superiority of RCTs. Despite the popularity of evidence ranking systems and hierarchies, nothing should replace critical appraisal of study methodology and examining the suitability of applying a given study design to a specific research question.

Long-regarded the gold standard of medical evidence, randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) have been given the paramount role in evaluating the safety and efficacy of new interventions to improve human health and wellbeing. Several ranking systems, including evidence hierarchies and the GRADE framework, consistently bestow superiority to the RCT and place limitations on the value that can be assigned to observational studies ( Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, et al., 2008 ; Rawlins, 2008 ; Schunemann, Fretheim, & Oxman, 2006 ). However, the limitations of RCTs are seldom acknowledged, nor is the fact that observational designs are often better suited to characterize certain health conditions, in particular, chronic diseases. Assuming epistemic superiority of RCTs has led to an inappropriate devaluation of other study designs and the findings they support. This trend is particularly important for fields that are less ethically or scientifically well-suited to RCTs, such as substance use and addiction.

Critique of current evidence ranking

The methodological strength from which RCTs draw their scientific credibility is the random allocation of the intervention among trial participants. Other primary strengths include, but are not limited to, blinding, the use of a control group and applying an intervention. Randomization is presumed to remove any between-group differences in prognostic factors associated with the development of the study outcome ( Sackett, 1996 ; Sackett, Strauss, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000 ). Observational studies are able to control for known confounders, yet RCTs are the only design to address the distribution of unknown confounders through randomization. However, randomization is not a guarantee that known or unknown confounders will be balanced between groups at the outset of a given study. The distribution of covariates between the intervention and control group after randomization is typically assessed by the trialists, and if uneven distributions are observed the randomization is deemed to have failed and is repeated until balanced groups are produced. Most importantly, it is also possible that imbalances in unknown confounders exist post-randomization, which cannot be detected or corrected by study investigators. Therefore, the extent to which RCTs can remove baseline imbalances between study arms is limited, to some degree, by the existing knowledge of the disease under study (i.e., the number of known confounders that can be assessed by the study investigators post-randomization). Imbalances in confounders are also an issue for observational studies. While randomization is a more effective strategy to balance these factors than approaches used in observational studies (e.g., propensity scores), randomization does not guarantee that prognostic balance is achieved ( Austin, 2011 ; Han, Enas, & McEntegart, 2009 ; Worrall, 2010 ).

The ability to establish external validity and extrapolate a trial’s findings beyond the study protocol is a second issue—one particularly germane to RCTs in substance use and addiction. With the objective of restricting any change in study outcome to the treatment intervention, RCTs typically seek to recruit a select and specific group of participants undergoing a highly structured intervention for a brief period with limited follow-up ( Rawlins, 2008 ; Worrall, 2010 ). Patients living with comorbidities or receiving multiple medications tend to be excluded in order to minimize the heterogeneity among study participants and minimize the risk of randomizing an intervention to vulnerable patients. Among people who use illicit drugs and are living with substance use disorders, minimizing heterogeneity in the study sample is challenging due to the high prevalence of comorbid health conditions and engagement with diverse health and social services. For example, current estimates among people who inject drugs report that upwards of 50% have a lifetime diagnosis of depression, 50% are living with hepatitis C virus infection, 13% are living with HIV and the medications/treatments prescribed to these patients are highly personalized ( Conner, Pinquart, & Duberstein, 2008 ; Kessler et al., 1994 ; Lengauer, Pfeifer, & Kaiser, 2014 ; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2017 ). Notwithstanding the ethical challenges of placing restrictions on inclusion and exclusion criteria, identifying a homogeneous group of participants based on these complex comorbidities and co-interventions is often practically untenable. Administering a structured intervention to this population is further complicated by high rates of marginalization (e.g., homelessness, social instability, stigmatization) and criminalization ( Marshall et al., 2016 ; Stone et al., 2018 ). In consequence, the average treatment effect calculated from an RCT is only as valuable as the sample from which it was estimated ( Dahabreh, 2018 ; Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ; Ioannidis, 2018 ). The superior internal validity of an RCT does not translate to invariance in the treatment effect across contexts if the sample is not representative of all the patients to which the study could be applied ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018a , 2018b ). Nevertheless, the results of RCTs are often extrapolated generously despite the limitations imposed by selection criteria and artificial environments that do not reflect real-world applications of the target intervention ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018a , 2018b ). As an alternative, some authors advocate for strategies such as propensity scores, instrumental variables and matching to strengthen the methodology of observational studies ( Concato & Horwitz, 2018 ; Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ). Empirical comparisons between RCTs and well-designed observational studies have found similar summary measures of effect size with neither design producing a consistently greater effect ( Anglemyer, Horvath, & Bero, 2014 ; Benson & Hartz, 2000 ; Concato, Shah, & Horwitz, 2000 ; Sterne et al., 2002 ). Moreover, many treatments that continue to be used in clinical and non-clinical settings have been evaluated through observational methods have been found to be both safe and effective ( Concato & Horwitz, 2018 ; Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ; Tsimberidou, Braiteh, Stewart, & Kurzrock, 2009 ). In these cases, conducting an RCT on the basis that the existing evidence is observational is unnecessary based on the long-term record of safety and effectiveness and RCTs may expose patients to unnecessary risk if patients are denied treatment shown to be beneficial ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ; Vandenbroucke, 2008 ).

Some authors have also questioned the value of RCTs and evidence hierarchies for identifying unintended or adverse effects of new treatment interventions ( Osimani, 2013 ; Vandenbroucke, 2008 ). As the unintended or possibly adverse effects of novel treatments are typically unknown, the treatment allocation is masked with respect to the unintended effects even if the investigator is aware of who is receiving the treatment ( Vandenbroucke, 2004 ). These authors argue that this achieves the same separation between intervention allocation and prognosis that is accomplished through blinding ( Osimani, 2013 ). As a result, observational studies examining adverse events will not be as vulnerable to confounding and selection bias as observational studies evaluating intervention efficacy ( Vandenbroucke, 2004 , 2006 , 2008 ; Vandenbroucke & Psaty, 2008 ). This view is supported by empirical evidence that shows no systematic difference in risk estimation for adverse events between RCTs and observational studies ( Benson & Hartz, 2000 ; Concato et al., 2000 ; Papanikolaou, Christidi, & Ioannidis, 2006 ). A second critique is that the strict inclusion criteria of RCTs may exclude vulnerable participants with complex comorbidities at an increased risk of experiencing adverse events, which applies to many people who use drugs ( Conner et al., 2008 ; Rawlins, 2008 ). In these circumstances case reports or case series may be the most sensitive or only tool available to identify side effects ( Glasziou, Chalmers, Rawlins, & McCulloch, 2007 ; Stricker & Psaty, 2004 ). Based on these arguments, it has been suggested that the evidence hierarchy should be inverted when the objective is to identify unknown adverse events ( Vandenbroucke, 2008 ).

Although RCTs excel at investigating the safety and efficacy of novel pharmacological formulations, issues arise in testing harm reduction-based interventions to benefit people who inject drugs. The risk environments in which needle exchange programs (NEP) and supervised injection facilities (SIF) are implemented are highly variable between settings. For example, the criminalization of illicit drug use in North America has adjusted as policies legalizing and regulating non-medical cannabis continue to expand in the context of an opioid overdose crisis sparked by the contamination of the illicit drug supply. In these circumstances, long-term observational studies in real world or natural settings may be better suited to evaluate the evolving impacts of changes in substance use policy and criminalization than RCTs. While RCTs are not feasible or ethical in this situation, observational studies are advantageous in that they can often include more follow-up time than RCTs, which is needed to better evaluate the long-term effects of structural factors such as policy change and criminalization on the chronic and dynamic nature of substance use and addiction ( Kelly, Greene, & Bergman, 2018 ; Worrall, 2010 ). The utility of real world data has sparked calls for the integration of alternative data sources such as electronic health records and patient registries to study patient groups who may have been excluded from RCTs (e.g., elderly people living with comorbidities) ( Nabhan, Klink, & Prasad, 2019 ). Other alternatives that have been applied to evaluating substance use include pragmatic trials that blend the traits of observational studies with traditional RCTs ( Coulton et al., 2017 ; Henderson et al., 2017 ). Alternative trial designs including stepped wedge and crossover trials have been effectively applied to study diseases requiring extended follow-up evaluation ( Chotard et al., 1992 ; Hemming, Haines, Chilton, Girling, & Lilford, 2015 ). These designs have been used in diverse areas, including HIV and social policy, although they are challenging when the intervention is believed to be effective and receipt should not be denied or delayed, or there are complex contextual and patient factors that moderate the impact of the intervention on the study outcome ( Bonell et al., 2011 ; Brown & Lilford, 2006 ). Unfortunately, these challenges are common among interventions for people who use drugs. Blinding and providing a placebo are often not possible for these interventions and extrapolating the effects of the intervention beyond the study protocol must be done with caution given that substance use and addiction are chronic and relapsing conditions ( Kelly et al., 2018 ; Kelly, Greene, Bergman, White, & Hoeppner, 2019 ).

Perhaps the most significant unacknowledged weakness of RCTs is their typically limited periods for the intervention and follow-up. Due to their substantial expense, funding for post-study follow-up is typically limited to six to 24 months, which is often insufficient for chronic diseases ( Bluhm, 2010 ; Vlieland, 2002 ) such as substance use disorders, characterized as chronically relapsing conditions with recurring transitions between substance use, abstinence, treatment engagement and incarceration ( Dennis & Scott, 2007 ; Kelly et al., 2019 ). For example, the median time from first to final instance of substance use was estimated at 27 years among people admitted to publicly-funded treatment who were able to abstain for at least one year, and the average time between the first episode of substance use treatment and last instance of substance use was nine years ( Dennis, Scott, Funk, & Foss, 2005 ). A recent analyses from a national study of adults in recovery in the United States (N=39,809) found that an average of two to five attempts were required to resolve an alcohol or drug problem and the number of attempts varied by demographic characteristics, type of treatment and clinical history ( Kelly et al., 2019 ). African American ethnicity, previous use of treatment and mutual-help groups and psychiatric comorbidity were associated with a greater number of recovery attempts ( Kelly et al., 2019 ). Moreover, many patient-important outcomes including quality of life, happiness and self-esteem do not increase monotonically during recovery. These measures were found to decrease significantly in the first year following resolution of an alcohol or drug problem and then increase over subsequent years ( Kelly et al., 2018 ). As a result, the methodological strengths of RCTs are, to some extent, mitigated by the limitations of administering brief structured interventions to a heterogeneous population living with chronic and dynamic disorders. For conditions such as substance use and addiction, RCTs are often limited to providing a snapshot of the effectiveness of interventions in the short term and may fail to identify long-term effects among heterogeneous groups of participants living with chronic and dynamic disorders. In these circumstances, observational studies are often better suited to study interventions designed for a more representative sample of individuals who are often excluded from studies requiring randomization, and who require long-term follow to evaluate enduring changes in study outcomes ( Bluhm, 2010 ; Worrall, 2010 ). Rather than viewing observational designs as a next best option in situations where RCTs are perceived as practically or ethically unfeasible, it should be recognized that the methodological strengths of observational studies may provide the best available evidence to evaluate the course of chronic conditions and the effect of interventions to address them ( Bluhm, 2010 ; Worrall, 2010 ).

In contrast to the approach of evidence-based medicine that strives to identify the most accurate estimate of an average treatment effect, other researchers have proposed a framework that conceptualizes health interventions as “evidence-making” ( Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). Rather than assuming a singular and universal effect of an intervention, the evidence-making framework posits that the variability of practice and patients produces multiple realities of the effects of an intervention and treats evidence, interventions and their effects as emergent, contingent and multiple ( Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). By recognizing that the diversity of practices creates multiple realities of an intervention, evidence-making frameworks foster dialogue across diverse forms of knowledge and knowledge actors to recognize how the politics of intervention knowledge and the realities they create influence their effects across settings ( Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed analysis of this framework, similar approaches have been raised by authors who advocate for a process of cumulative scientific understanding that is often challenged by the assumptions of evidence-based medicine and evidence hierarchies ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ). The production of new scientific evidence should build upon and be integrated with existing knowledge to enhance collective scientific knowledge. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for the findings from observational studies to be dismissed if more recent evidence from a randomized study contradicts the original results ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018a , 2018b ). Some experts argue that new findings must be able to explain or be integrated with previous results as knowledge advances, even if previous results are believed to be invalid ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ). Failure to integrate results from randomized and non-randomized studies undermines the responsibility of science to advance the cumulative understanding of health interventions and acknowledge the legitimate variability of intervention effects created by the diversity of practice and patients ( Concato et al., 2000 ; Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ).

The inappropriate devaluation of observational studies has slowed the implementation and scale-up of several harm reduction interventions for PWUD. The observational evidence supporting SIF and NEP includes many large-scale prospective cohort studies with several years of follow-up from multiple countries ( Aspinall et al., 2014 ; Potier, Laprevote, Dubois-Arber, Cottencin, & Rolland, 2014 ; Wood, Tyndall, Montaner, & Kerr, 2006 ). The advantages of being able to prospectively evaluate the health impacts of these interventions among heterogeneous samples of people who use drugs in real-world settings are unique methodological strengths that provide evidence into the long-term trajectories of this population. Existing evaluations of NEP and SIF have provided strong evidence for reducing HIV risk behaviours, overdose mortality and increasing engagement with addiction treatment services without adverse effects on broader public health and safety ( Aspinall et al., 2014 ; Marshall, Milloy, Wood, Montaner, & Kerr, 2011 ; Potier et al., 2014 ). In spite of this evidence, these services remain limited in many countries contending with the challenges of substance use harms ( Degenhardt et al., 2014 ).

Although ideological opposition to harm reduction-based interventions like NEP and SIF remains the primary barrier limiting their availability in many settings worldwide ( Nadelmann & LaSalle, 2017 ), their establishment and expansion has also been hindered by an ironic epistemic predicament regarding their scientific evaluation. As these services provide self-evident health and safety benefits to profoundly marginalized and vulnerable individuals, regulators and trialists have determined it would be unethical to evaluate them through RCTs as randomization would restrict the control group from accessing potentially life-saving interventions ( Bastos & Strathdee, 2000 ; Bluthenthal & Kral, 2010 ; Lurie, 1998 ). Yet, when observational evidence accumulates demonstrating the benefit of these interventions, the lack of RCTs is critiqued as a methodological weakness ( Bluthenthal & Kral, 2010 ). In effect, the anticipated benefit of these services limits the credibility of subsequent empirical evidence supporting these services ( Bluthenthal & Kral, 2010 ). Throughout the implementation of NEP and SIF, the use of observational methodologies to evaluate these services has often been referenced as a precaution against their expansion or a methodological limitation ( Palmateer et al., 2010 ; Wood et al., 2006 ).

In addition, the effectiveness of SIFs has been challenged based on uncertainty regarding the effect size of these services, despite the large evidence base that is nearly unanimous in support of SIF, with no SIF overdose deaths reported to date and no reported adverse effects ( Caulkins, Pardo, & Kilmer, 2019 ; May, Holloway, & Bennett, 2019 ). Criticism about effect heterogeneity relates to the EBM objective of estimating a singular treatment effect, whereas it is entirely possible, and we would argue likely, that the effect size of these interventions may vary across patient populations and contexts ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ; Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). Rather than this heterogeneity being perceived as a weakness of study methodology, we would argue that this variability is consistent with the evidence-making intervention framework whereby the diversity of practice and patients creates multiple realities of an intervention’s effects ( Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). In fact, this variability should be expected based on the specific crisis situations in which these services are often implemented ( Caulkins et al., 2019 ). SIFs have been established in diverse countries experiencing different types of illicit substance use, patient populations, service models, local contexts, adjunct services and drug policy ( Caulkins et al., 2019 ). These situations are not well-suited to the evidence-based medicine perspective that attempts to minimize patient and intervention heterogeneity to estimate a precise and singular treatment effect ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ; Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). Instead, the existence of multiple contingent effects of an intervention that are adaptive is in keeping with the ontology of the evidence-making intervention framework ( Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). While we acknowledge that randomizing participants to SIF participation (e.g., through community-randomized trials or wait-list studies) would be theoretically valuable, we contend that this is has become unethical and unnecessary given the evidence of benefit and absence of harm associated with these services ( Caulkins et al., 2019 ; Kennedy, Hayashi, Milloy, Wood, & Kerr, 2019 ). As previously mentioned, RCTs do not have the same benefits for assessing adverse outcomes and the risks associated with denying or delaying SIF use among vulnerable populations of PWUD through RCTs is difficult to justify ( May et al., 2019 ; Osimani, 2013 ; Vandenbroucke, 2006 ). Although RCTs are held as the gold-standard for identifying causal associations, observational and qualitative studies are able to provide valuable evidence about the causal mechanisms underlying these associations and contribute to advancing the cumulative understanding of an intervention without the need for experimental closure ( Deaton & Cartwright, 2018b ; Rhodes & Lancaster, 2019 ). The study design that provides the best evidence may therefore vary depending on the theory or research question being evaluated; this should be reflected in evidence ranking systems such as the GRADE framework and the Maryland Scientific Methods Scale that place limits on the value that can be assigned to non-randomized studies ( Alonso-Coello et al., 2016 ; Worrall, 2010 ).

There are examples where observational studies have been sufficient to demonstrate effectiveness and continue to be used clinically without the need for verification through RCTs. An analysis of oncology drugs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration found that 31 of 68 drugs were approved without an RCT and 30 of these drugs remain fully approved ( Concato & Horwitz, 2018 ; Tsimberidou et al., 2009 ). Studies using objective endpoints were the most common among those approved and these drugs demonstrated a long-term record of efficacy and safety based on observational evidence ( Tsimberidou et al., 2009 ). There are also cases where the belief that RCTs are needed to confirm observational evidence has caused harm. The controversy surrounding the RCTs of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) therapy in newborns has been well described ( Bluhm, 2010 ; Truog, 1992 ). Both ECMO and the standard treatment were evolving rapidly and observational studies had already supported the benefit of ECMO ( Bartlett, 1984 ; Wung, James, Kilchevsky, & James, 1985 ). Yet, variability in the success rate of ECMO across centres prompted many researchers to call for RCTs before ECMO became an accepted therapy ( Bluhm, 2010 ). In the first trial, the one infant who received conventional therapy did not survive while all 11 who received ECMO survived ( Bartlett et al., 1985 ). In phase one of the second trial, four of the ten newborns receiving conventional therapy did not survive while all nine who received ECMO survived ( O’Rourke et al., 1989 ). In phase two, 20 patients received ECMO and 19 survived ( O’Rourke et al., 1989 ). These examples have led some experts to suggest that RCTs should not be used in cases where interventions are rapidly evolving and are potentially life saving ( Truog, 1992 ). In these cases, the interventions or their implementation may be out-dated by the time the RCT has concluded and observational studies of clinical practice (e.g., outcomes research) may provide better evidence of intervention effectiveness while avoiding some of the ethical challenges of withholding or delaying novel treatments in RCTs ( Truog, 1992 ; Worrall, 2010 ). This is particularly relevant to the situation of SIFs, which are often implemented in situations of crisis that are rapidly evolving as new challenges arise, such as the multiple waves of the opioid overdose crisis. Under these circumstances, variability in the effect should not detract from the fact the evidence is, even in the opinion of critics, “almost unanimous in its support” and is potentially life saving ( Caulkins et al., 2019 ; Kennedy et al., 2019 ; May et al., 2019 ). Performing RCTs of SIFs to ascertain a singular measure of effect should be viewed as unnecessary and unethical given the existing evidence and that observational studies may provide better information to evaluate these interventions based on the evolving context of their implementation and the potential for them to be life saving.

Future directions for addiction science and evidence ranking

An alternative observational design that has gained considerable attention, particularly for studying chronic diseases, is Mendelian randomization ( Lawlor, Harbord, Sterne, Timpson, & Davey Smith, 2008 ; Smith, 2006 ). These studies integrate genetic variants into observational epidemiology to enhance the causal inferences that can be drawn about modifiable risk factors and health outcomes ( Smith & Ebrahim, 2003 ; Youngman, Keavney, & Palmer, 2000 ). Rather than randomize participants to receive the exposure being studied, Mendelian randomization studies take advantage of the random assignment of an individual’s genotype from their parents to conduct a ‘natural’ RCT ( Davey Smith & Ebrahim, 2005 ; Hingorani & Humphries, 2005 ). If germline genetic variants for an environmental exposure (e.g., substance use) have been identified, these variants can be used as a proxy measure of the exposure in observational studies and be treated as randomly distributed ( Lawlor et al., 2008 ; Pasman et al., 2018 ). Mendelian randomization studies can also be performed in representative population samples without the need for exclusion criteria or randomizing participants as is necessary in traditional RCTs ( Lawlor et al., 2008 ; Smith & Ebrahim, 2003 ). In addition, the associations between these gene variants and health outcomes are not susceptible to reverse causality as germline genotypes are not affected by disease progression, and, if the gene variant is not pleiotropic, the risk of confounding is mitigated ( Smith & Ebrahim, 2004 ). Finally, genetic variants that predict an environmental exposure typically do so throughout the life span, a fact which minimizes regression dilution bias ( Smith & Ebrahim, 2004 ). As the cost of genome sequencing continues to decrease and more large-scale consortia are forming, integrating genetic data into observational designs is becoming increasingly feasible for studies of substance use and addiction ( Pasman et al., 2018 ; Phillips, Deverka, Hooker, & Douglas, 2018 ; Vaucher et al., 2018 ). For example, Mendelian randomization studies have been applied to investigate the longstanding debate surrounding the association between schizophrenia and cannabis use ( Gage et al., 2017 ; Pasman et al., 2018 ; Vaucher et al., 2018 ). The limitations of Mendelian randomization studies include population stratification, identifying a reliable genetic variant for the exposure of interest that does not have pleiotropic effects on the outcome and is not in linkage disequilibrium with other gene variants associated with the outcome ( Cardon & Palmer, 2003 ; Lawlor et al., 2008 ; Smith & Ebrahim, 2004 ). Additional challenges include developmental compensation, contextual influences on the exposures predicted by gene variants and non-linear associations ( Gibson & Wagner, 2000 ). Despite these limitations, Mendelian randomization studies retain the ability of traditional observational studies to study the development of chronic conditions over time with the advantage of studying gene variants for exposures that are randomly distributed ( Lawlor et al., 2008 ; Smith & Ebrahim, 2003 ). The ability to combine the strengths of observational studies while adding a component of randomization should challenge the assumed superiority of RCTs among policymakers and healthcare professionals. The evidence from these studies may also prevent the need to conduct RCTs to address certain research questions. For example, a Mendelian randomization study evaluating the effects of selenium supplementation on prostate cancer risk provided evidence of no effect, which was consistent with the largest ever prostate cancer prevention trial ( Yarmolinsky et al., 2018 ). This trial was stopped before completion based on a lack of efficacy and adverse events, at a cost of $114 million ( Yarmolinsky et al., 2018 ). As the efficacy and adverse events were predicted by this Mendelian randomization study, these designs may be an efficient and affordable means to study interventions traditionally assessed RCTs as big data resources for genetic information continue to expand ( Yarmolinsky et al., 2018 ).

A second area for improvement in substance use and addiction research is the further integration of patient-important outcomes. The underrepresentation of patient-reported outcomes has been highlighted in several study designs yet is more pronounced in RCTs ( Pardo-Hernandez & Alonso-Coello, 2017 ; Saldanha et al., 2017 ). Previous field-specific systematic reviews of RCTs have found that less than 25% include a patient-important outcome as a primary outcome ( Gaudry et al., 2017 ; Rahimi, Malhotra, Banning, & Jenkinson, 2010 ). The lack of patient-important outcomes is highly germane to substance use research and a systematic review is currently ongoing to identify patient-important outcomes to assess the effectiveness of opioid use disorder in the context of the overdose epidemic ( Dennis et al., 2015 ; Sanger et al., 2018 ). Increased recognition of the value of patient-important data is reflected in the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system, which recommends their inclusion at two different stages (the outset of study design and when ranking the importance of study outcomes) ( Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, et al., 2008 ). Other frameworks designed to help stakeholders translate scientific evidence to healthcare decisions prioritize the inclusion of patient-important outcomes and considers the degree to which patients value each outcome ( Alonso-Coello et al., 2016 ). The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative extends this view by promoting the selection of a standardized set of outcomes for each health condition to compare effectiveness across studies (“ The COMET Initiative,” 2010 ; Gorst et al., 2016 ; Williamson et al., 2012 ). The lack of patient-important outcomes in addiction literature, and the fact that these measures vary significantly in different stages of addiction, calls for further integration of these outcomes in future research ( Kelly et al., 2018 ; Sanger et al., 2018 ). Given the value of patient-important outcomes—and that they are prioritized in stakeholder frameworks including GRADE and COMET—further evaluation of these outcomes will be important to promote the uptake of observational evidence on substance use and addiction among policymakers and healthcare officials ( Gorst et al., 2016 ; Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, et al., 2008 ; Pardo-Hernandez & Alonso-Coello, 2017 ; Williamson et al., 2012 ).

There are, without question, important limitations to studies with non-randomized designs. However, the value offered by observational studies should be reflected in evidence-based medicine by allowing more flexibility in evidence hierarchies that presume methodological superiority of RCTs. Observational designs may provide the best evidence to evaluate interventions to address chronic conditions such as substance use and addiction. Unfortunately, assuming epistemic superiority of RCTs has unnecessarily slowed the uptake of substance use research and harm reduction services for people who use drugs. Despite the popularity of evidence ranking systems and hierarchies, nothing should replace critical appraisal of study methodology and examining the suitability of applying a given study design to a specific clinical question.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN 222). Dr. Hudson Reddon is supported by a Sponsor/CTN Postdoctoral Fellowship Award and a Michael Smith Research Trainee Award. Dr. M-J Milloy is supported in part by the United States National Institutes of Health (U01-DA021525), a New Investigator Award from CIHR and a Scholar Award from MSFHR. His institution has received an unstructured gift to support him from NG Biomed, Ltd., a private firm applying for a government license to produce cannabis. The Canopy Growth professorship in cannabis science was established through unstructured gifts to the University of British Columbia from Canopy Growth, a licensed producer of cannabis, and the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions of the Government of British Columbia.

Competing Interests: None to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, … Group, G. W. (2016). GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction . BMJ , 353 , i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anglemyer A, Horvath HT, & Bero L. (2014). Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials . Cochrane Database Syst Rev ( 4 ), MR000034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000034.pub2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aspinall EJ, Nambiar D, Goldberg DJ, Hickman M, Weir A, Van Velzen E, … Hutchinson SJ (2014). Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Int J Epidemiol , 43 ( 1 ), 235–248. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt243 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Austin PC (2011). An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies . Multivariate Behav Res , 46 ( 3 ), 399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartlett RH (1984). Extracorporeal oxygenation in neonates . Hosp Pract (Off Ed) , 19 ( 4 ), 139–143, 146, 151. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1984.11702803 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartlett RH, Roloff DW, Cornell RG, Andrews AF, Dillon PW, & Zwischenberger JB (1985). Extracorporeal circulation in neonatal respiratory failure: a prospective randomized study . Pediatrics , 76 ( 4 ), 479–487. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bastos FI, & Strathdee SA (2000). Evaluating effectiveness of syringe exchange programmes: current issues and future prospects . Soc Sci Med , 51 , 1771–1782. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Benson K, & Hartz AJ (2000). A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials . Am J Ophthalmol , 130 ( 5 ), 688. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00754-6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bluhm R. (2010). The epistemology and ethics of chronic disease research: Further lessons from ECMO . Theory of Medical Bioethics , 31 , 107–122. doi: 10.1007/s11017-010-9139-8 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bluthenthal R, & Kral A. (2010). Commentary on Palmateer et al. (2010): next steps in the global research agenda on syringe access for injection drug users . Addiction , 105 ( 5 ), 860–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02942.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bonell CP, Hargreaves J, Cousens S, Ross D, Hayes R, Petticrew M, & Kirkwood BR (2011). Alternatives to randomisation in the evaluation of public health interventions: design challenges and solutions . J Epidemiol Community Health , 65 ( 7 ), 582–587. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082602 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown CA, & Lilford RJ (2006). The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review . BMC Med Res Methodol , 6 , 54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-54 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cardon LR, & Palmer LJ (2003). Population stratification and spurious allelic association . Lancet , 361 ( 9357 ), 598–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12520-2 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caulkins JP, Pardo B, & Kilmer B. (2019). Supervised consumption sites: a nuanced assessment of the causal evidence . Addiction , 114 ( 12 ), 2109–2115. doi: 10.1111/add.14747 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chotard J, Inskip HM, Hall AJ, Loik F, Mendy M, Whittle H, … Lowe Y. (1992). The Gambia Hepatitis Intervention Study: follow-up of a cohort of children vaccinated against hepatitis B . J Infect Dis , 166 ( 4 ), 764–768. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.764 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The COMET Initiative . (2010). [ Google Scholar ]

- Concato J, & Horwitz RI (2018). Randomized trials and evidence in medicine: A commentary on Deaton and Cartwright . Soc Sci Med , 210 , 32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.010 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Concato J, Shah N, & Horwitz RI (2000). Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs . N Engl J Med , 342 ( 25 ), 1887–1892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Conner KR, Pinquart M, & Duberstein PR (2008). Meta-analysis of depression and substance use and impairment among intravenous drug users (IDUs) . Addiction , 103 ( 4 ), 524–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02118.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coulton S, Stockdale K, Marchand C, Hendrie N, Billings J, Boniface S, … Wilson E. (2017). Pragmatic randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a multi-component intervention to reduce substance use and risk-taking behaviour in adolescents involved in the criminal justice system: A trial protocol (RISKIT-CJS) . BMC Public Health , 17 ( 1 ), 246. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4170-6 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dahabreh IJ (2018). Randomization, randomized trials, and analyses using observational data: A commentary on Deaton and Cartwright . Soc Sci Med , 210 , 41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davey Smith G, & Ebrahim S. (2005). What can mendelian randomisation tell us about modifiable behavioural and environmental exposures? BMJ , 330 ( 7499 ), 1076–1079. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7499.1076 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deaton A, & Cartwright N. (2018a). Reflections on Randomized Control Trials . Soc Sci Med , 210 , 86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.046 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Deaton A, & Cartwright N. (2018b). Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials . Soc Sci Med , 210 , 2–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.005 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Degenhardt L, Mathers BM, Wirtz AL, Wolfe D, Kamarulzaman A, Carrieri MP, … Beyrer C. (2014). What has been achieved in HIV prevention, treatment and care for people who inject drugs, 2010–2012? A review of the six highest burden countries . International Journal of Drug Policy , 25 ( 1 ), 53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dennis BB, Roshanov PS, Naji L, Bawor M, Paul J, Plater C, … Thabane L. (2015). Opioid substitution and antagonist therapy trials exclude the common addiction patient: a systematic review and analysis of eligibility criteria . Trials , 16 , 475. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0942-4 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dennis M, Scott C, Funk R, & Foss M. (2005). The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers . J Subst Abuse Treat , 28 ( 1 ), S61–S62. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dennis M, & Scott CK (2007). Managing addiction as a chronic condition . Addict Sci Clin Pract , 4 ( 1 ), 45–55. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gage SH, Jones HJ, Burgess S, Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Zammit S, & Munafo MR (2017). Assessing causality in associations between cannabis use and schizophrenia risk: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study . Psychol Med , 47 ( 5 ), 971–980. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003172 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaudry S, Messika J, Ricard JD, Guillo S, Pasquet B, Dubief E, … Tubach F. (2017). Patient-important outcomes in randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients: a systematic review . Ann Intensive Care , 7 ( 1 ), 28. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0243-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibson G, & Wagner G. (2000). Canalization in evolutionary genetics: a stabilizing theory? Bioessays , 22 ( 4 ), 372–380. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200004)22:4<372::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-J [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, & McCulloch P. (2007). When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise . BMJ , 334 ( 7589 ), 349–351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39070.527986.68 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gorst SL, Gargon E, Clarke M, Blazeby JM, Altman DG, & Williamson PR (2016). Choosing Important Health Outcomes for Comparative Effectiveness Research: An Updated Review and User Survey . PLoS One , 11 ( 1 ), e0146444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146444 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ, & Group GW (2008). What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ , 336 ( 7651 ), 995–998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, … Group, G. W. (2008). GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations . BMJ , 336 ( 7650 ), 924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Han B, Enas NH, & McEntegart D. (2009). Randomization by minimization for unbalanced treatment allocation . Stat Med , 28 ( 27 ), 3329–3346. doi: 10.1002/sim.3710 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, Girling AJ, & Lilford RJ (2015). The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting . BMJ , 350 , h391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h391 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Henderson JL, Cheung A, Cleverley K, Chaim G, Moretti ME, de Oliveira C, … Szatmari P. (2017). Integrated collaborative care teams to enhance service delivery to youth with mental health and substance use challenges: protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial . BMJ Open , 7 ( 2 ), e014080. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014080 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hingorani A, & Humphries S. (2005). Nature’s randomised trials . Lancet , 366 ( 9501 ), 1906–1908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67767-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ioannidis JPA (2018). Randomized controlled trials: Often flawed, mostly useless, clearly indispensable: A commentary on Deaton and Cartwright . Soc Sci Med , 210 , 53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.029 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly J, Greene C, & Bergman B. (2018). Beyond abstinence: Changes in indices of quality of lifewith time in recovery in a nationally-representative sample of US adults . Alcohol Clin Exp Res , 42 ( 4 ), 770–780. doi: 10.1111/acer.13604 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly JF, Greene MC, Bergman BG, White WL, & Hoeppner BB (2019). How Many Recovery Attempts Does it Take to Successfully Resolve an Alcohol or Drug Problem? Estimates and Correlates From a National Study of Recovering U.S. Adults . Alcohol Clin Exp Res , 43 ( 7 ), 1533–1544. doi: 10.1111/acer.14067 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kennedy MC, Hayashi K, Milloy MJ, Wood E, & Kerr T. (2019). Supervised injection facility use and all-cause mortality among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada: A cohort study . PLoS Med , 16 ( 11 ), e1002964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002964 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, … Kendler KS (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey . Arch Gen Psychiatry , 51 ( 1 ), 8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, & Davey Smith G. (2008). Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology . Stat Med , 27 ( 8 ), 1133–1163. doi: 10.1002/sim.3034 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lengauer T, Pfeifer N, & Kaiser R. (2014). Personalized HIV therapy to control drug resistance . Drug Discov Today Technol , 11 , 57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2014.02.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lurie P. (1998). Re: ‘Invited commentary: le mystere de Montreal’ . Am J Epidemiol , 148 , 715–716. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshall BD, Elston B, Dobrer S, Parashar S, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, … Milloy MJ (2016). The population impact of eliminating homelessness on HIV viral suppression among people who use drugs . AIDS , 30 ( 6 ), 933–942. doi: 10.1097/qad.0000000000000990 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marshall BD, Milloy MJ, Wood E, Montaner JS, & Kerr T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study . Lancet , 377 ( 9775 ), 1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62353-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- May T, Bennett T, & Holloway K. (2018). RETRACTED: The impact of medically supervised injection centres on drug-related harms: a meta-analysis . Int J Drug Policy , 59 , 98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.06.018 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- May T, Holloway K, & Bennett T. (2019). The need to broaden and strengthen the evidence base for supervised consumption sites . Addiction , 114 ( 12 ), 2117–2118. doi: 10.1111/add.14789 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nabhan C, Klink A, & Prasad V. (2019). Real-world Evidence-What Does It Really Mean? JAMA Oncol , 5 ( 6 ), 781–783. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0450 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nadelmann E, & LaSalle L. (2017). Two steps forward, one step back: current harm reduction policy and politics in the United States . Harm Reduct J , 14 ( 1 ), 37. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0157-y [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Rourke PP, Crone RK, Vacanti JP, Ware JH, Lillehei CW, Parad RB, & Epstein MF (1989). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and conventional medical therapy in neonates with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: a prospective randomized study . Pediatrics , 84 ( 6 ), 957–963. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Osimani B. (2013). Until RCT proven? On the asymmetry of evidence requirements for risk assessment . J Eval Clin Pract , 19 ( 3 ), 454–462. doi: 10.1111/jep.12039 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Palmateer N, Kimber J, Hickman M, Hutchinson S, Rhodes T, & Goldberg D. (2010). Evidence for the effectiveness of sterile injecting equipment provision in preventing hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus transmission among injecting drug users: a review of reviews . Addiction , 105 ( 5 ), 844–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02888.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Papanikolaou PN, Christidi GD, & Ioannidis JP (2006). Comparison of evidence on harms of medical interventions in randomized and nonrandomized studies . CMAJ , 174 ( 5 ), 635–641. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050873 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pardo-Hernandez H, & Alonso-Coello P. (2017). Patient-important outcomes in decision-making: a point of no return . J Clin Epidemiol , 88 , 4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.014 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pasman JA, Verweij KJH, Gerring Z, Stringer S, Sanchez-Roige S, Treur JL, … Vink JM (2018). GWAS of lifetime cannabis use reveals new risk loci, genetic overlap with psychiatric traits, and a causal influence of schizophrenia . Nat Neurosci , 21 ( 9 ), 1161–1170. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0206-1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Phillips KA, Deverka PA, Hooker GW, & Douglas MP (2018). Genetic Test Availability And Spending: Where Are We Now? Where Are We Going? Health Aff (Millwood) , 37 ( 5 ), 710–716. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1427 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Potier C, Laprevote V, Dubois-Arber F, Cottencin O, & Rolland B. (2014). Supervised injection services: what has been demonstrated? A systematic literature review . Drug Alcohol Depend , 145 , 48–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rahimi K, Malhotra A, Banning AP, & Jenkinson C. (2010). Outcome selection and role of patient reported outcomes in contemporary cardiovascular trials: systematic review . BMJ , 341 , c5707. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5707 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rawlins MD (2008). De Testimonio: On the Evidence for Decisions about the use of Therapeutic Interventions The Harveian Oration . London: Royal College of Physicians. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhodes T, & Lancaster K. (2019). Evidence-making interventions in health: A conceptual framing . Soc Sci Med , 238 , 112488. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112488 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- ackett DL (1996). Evidence based medicine. What it is and what it isn’t . British Medical Journal , 312 , 71–72. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sackett DL, Strauss SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, & Haynes RB (2000). Evidence Based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM (2 ed.). Edinburgh and London: Churchill Livingston. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saldanha IJ, Li T, Yang C, Owczarzak J, Williamson PR, & Dickersin K. (2017). Clinical trials and systematic reviews addressing similar interventions for the same condition do not consider similar outcomes to be important: a case study in HIV/AIDS . J Clin Epidemiol , 84 , 85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.005 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanger N, Shahid H, Dennis BB, Hudson J, Marsh D, Sanger S, … Samaan Z. (2018). Identifying patient-important outcomes in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder patients: a systematic review protocol . BMJ Open , 8 ( 12 ), e025059. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025059 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schunemann HJ, Fretheim A, & Oxman AD (2006). Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 9. Grading evidence and recommendations . Health Res Policy Syst , 4 ( 21 ). [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith GD (2006). Capitalising on Mendelian randomisation to assess the effects of treatment . James Lind Library . [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith GD, & Ebrahim S. (2003). ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol , 32 ( 1 ), 1–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg070 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith GD, & Ebrahim S. (2004). Mendelian randomization: prospects, potentials, and limitations . Int J Epidemiol , 33 ( 1 ), 30–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh132 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sterne JA, Juni P, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Bartlett C, & Egger M. (2002). Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in ‘meta-epidemiological’ research . Stat Med , 21 ( 11 ), 1513–1524. doi: 10.1002/sim.1184 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stone J, Fraser H, Lim AG, Walker JG, Ward Z, MacGregor L, … Vickerman P. (2018). Incarceration history and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Lancet Infect Dis , 18 ( 12 ), 1397–1409. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30469-9 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stricker BH, & Psaty BM (2004). Detection, verification, and quantification of adverse drug reactions . BMJ , 329 ( 7456 ), 44–47. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.44 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Truog RD (1992). Randomized controlled trials: lessons from ECMO . Clin Res , 40 ( 3 ), 519–527. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsimberidou AM, Braiteh F, Stewart DJ, & Kurzrock R. (2009). Ultimate fate of oncology drugs approved by the us food and drug administration without a randomized Trial . J Clin Oncol , 27 ( 36 ), 6243–6250. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6018 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2017). World Drug Report, United Nations publication (ISBN: 978–92-1–148291-1, eISBN:978–92-1–060623-3, Sales No. E.17.XI.6 ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandenbroucke JP (2004). When are observational studies as credible as randomised trials? Lancet , 363 ( 9422 ), 1728–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16261-2 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandenbroucke JP (2006). What is the best evidence for determining harms of medical treatment? CMAJ , 174 ( 5 ), 645–646. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051484 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandenbroucke JP (2008). Observational research, randomised trials, and two views of medical science . PLoS Med , 5 ( 3 ), e67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050067 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandenbroucke JP, & Psaty BM (2008). Benefits and risks of drug treatments: how to combine the best evidence on benefits with the best data about adverse effects . JAMA , 300 ( 20 ), 2417–2419. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.723 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaucher J, Keating BJ, Lasserre AM, Gan W, Lyall DM, Ward J, … Holmes MV (2018). Cannabis use and risk of schizophrenia: a Mendelian randomization study . Mol Psychiatry , 23 ( 5 ), 1287–1292. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.252 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vlieland T. (2002). Managing chronic disease: Evidence-based medicine or patient centred medicine? Health Care Analysis , 10 ( 3 ), 289–298. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E, & Tugwell P. (2012). Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider . Trials , 13 , 132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS, & Kerr T. (2006). Summary of findings from the evaluation of a pilot medically supervised safer injecting facility . CMAJ , 175 ( 11 ), 1399–1404. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060863 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Worrall J. (2010). Evidence: philosophy of science meets medicine . J Eval Clin Pract , 16 ( 2 ), 356–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01400.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wung JT, James LS, Kilchevsky E, & James E. (1985). Management of infants with severe respiratory failure and persistence of the fetal circulation, without hyperventilation . Pediatrics , 76 ( 4 ), 488–494. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yarmolinsky J, Bonilla C, Haycock PC, Langdon RJQ, Lotta LA, Langenberg C, … Martin RM (2018). Circulating Selenium and Prostate Cancer Risk: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis . J Natl Cancer Inst , 110 ( 9 ), 1035–1038. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy081 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Youngman LD, Keavney BD, & Palmer A. (2000). Plasma fibrinogen and fibrinogen genotypes in 4685 cases of myocardial infarction and in 6002 controls: test of causality by ‘Mendelian randomization’ . Circulation , 102 ( Suppl. II ), 31–32. [ Google Scholar ]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Addiction articles from across Nature Portfolio

Addiction involves loss of control over use of a substance, often in the presence of physiological and psychological dependence on a substance and compulsion to continue seeking and using the substance despite possible negative consequences.

Latest Research and Reviews

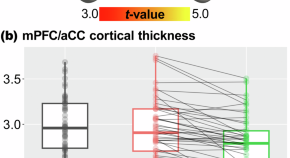

Medial prefrontal neuroplasticity during extended-release naltrexone treatment of opioid use disorder – a longitudinal structural magnetic resonance imaging study

- Zhenhao Shi

- Corinde E. Wiers

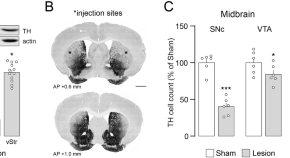

Rewarding properties of L-Dopa in experimental parkinsonism are mediated by sensitized dopamine D1 receptors in the dorsal striatum

- Carina Plewnia

- Débora Masini

- Gilberto Fisone

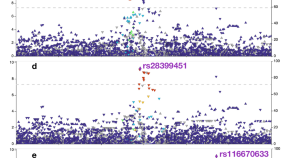

Fine-mapping the CYP2A6 regional association with nicotine metabolism among African American smokers

- Jennie G. Pouget

- Haidy Giratallah

- Rachel F. Tyndale

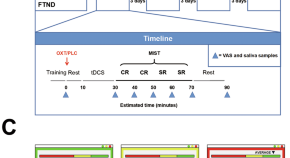

The interaction of oxytocin and nicotine addiction on psychosocial stress: an fMRI study

- Jiecheng Ren

- Yuting Zhang

- Zhengde Wei

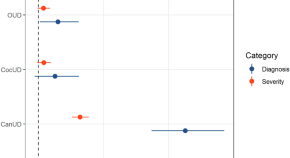

Association patterns of antisocial personality disorder across substance use disorders

- Aislinn Low

- Brendan Stiltner

- Renato Polimanti

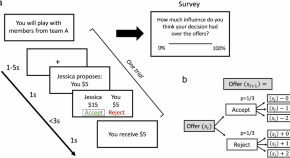

Aberrant neural computation of social controllability in nicotine-dependent humans

A neurocomputational model of social forward thinking shows that smokers under-estimate the influence of their actions on future interactions, a cognitive deficit associated with aberrant prefrontal and midbrain activities.

- Caroline McLaughlin

News and Comment

Morphine maladaptively modulates myelination.

- Leonie Welberg

Wrapping up reward

The maladaptive reward learning associated with morphine administration is shown here to be mediated by changes in dopamine-release dynamics in reward circuitry resulting from increased myelination specifically in the ventral tegmental area.

Cracking the chicken and egg problem of schizophrenia and substance use: Genetic interplay between schizophrenia, cannabis use disorder, and tobacco smoking

- Meghan J. Chenoweth

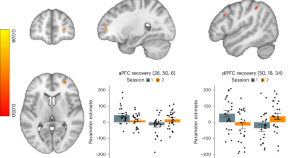

Prefrontal cortex activity increases after inpatient treatment for heroin addiction

Using task-based functional MRI, we examined inpatients with heroin use disorder. We found that 15 weeks of medication-assisted treatment (including supplemental group therapy) improved impaired anterior and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex function during an inhibitory control task. Inhibitory control, a core deficit in drug addiction, may be amenable to targeted prefrontal cortex interventions.

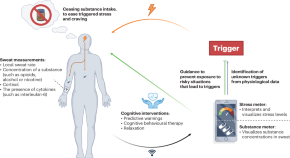

Towards on-skin analysis of sweat for managing disorders of substance abuse

A patient-centred system that leverages the analysis of sweat via wearable sensors may better support the management of patients with substance-use disorders.

- Noe Brasier

- Juliane R. Sempionatto

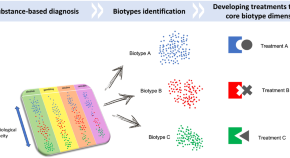

Addiction biotypes: a paradigm shift for future treatment strategies?

- Mauro Pettorruso

- Giorgio Di Lorenzo

- Giovanni Martinotti

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

- A Research Guide

- Research Paper Topics

- 40 Drug Abuse & Addiction Research Paper Topics

40 Drug Abuse & Addiction Research Paper Topics

Drug Abuse and Sociology

Drug abuse and medicine, drug abuse and psychology.

- Drug abuse and the degradation of neuron cells

- The social aspects of the drug abuse. The most vulnerable categories of people

- Drugs and religion. Drug abuse as the part of the sacred rituals

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Drug abuse as the part of human trafficking and as psychological defence of victims

- Reversible and irreversible consequences of drug abuse

- Drug abuse and minors

- Ethnic and cultural traditions that may lead to drug abuse

- Medical marijuana. Can legalizing it lead to drug abuse?

- The ethical questions of abusing painkiller drugs or other drugs that ease the state of a person

- The “club culture”. May it enhance the danger of drug abuse?

- Preventing drug abuse. Mandatory examination or voluntary learning: what will help most?

- The abstinence after the drug abuse. Rehabilitation and resocialization of the victims of it

- The harm done by drug abuse to the family and social relations

- The types of drugs and the impact of their abuse to the human body

- The positive effects of drugs. May they be reached without drawbacks of drug abuse?

- Alcoholics Anonymous, similar organisations and their role in overcoming the dependency

- Is constant smoking a drug abuse? Quitting smoking: government and social decisions

- Exotic addictions: game addiction, porn addiction etc. Do they have the effects similar to drug abuse?

- Substance abuse during pregnancy and before conceiving. What additional harm it causes?

- The correlation between drugs and spreading of HIV/AIDS

- Drug abuse and crime rates

- History of drug abuse. Opium houses, heroin cough syrup and others

- Drunk driving and drunk violence. The indirect victims of alcohol abuse

- The social rejection of the former drug abusers and the way to overcome it

- The main causes of drug abuse in the different social groups

- Drug abuse and mental health

- LGBTQ+ and drug abuse

- The development of drug testing. The governmental implementation of it

- Geniuses and drug abuse. Did drugs really helped them to create their masterpieces?

- Shall the laws about drug abuse be changed?

- Health Care Information Technology

- Drug abuse and global health throughout the 20-21 centuries

- Personal freedom or the safety of society: can drugs be allowed for personal use?

- Legal drinking age in different countries and its connection to the cultural diversity

- The different attitude to drugs and drug abuse in the different countries. Why it differs so much?

- Teenage and college culture. Why substance abuse is considered to be cool?

- Drugs, rape and robbery. Drugging people intentionally as the way to prevent them defending themselves

- 12-Step Programs and their impact on healing the drug addiction

- Alcohol, tobacco and sleeping pills advertising. Can it lead to more drug abuse?

By clicking "Log In", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

Sign Up for your FREE account

Substance use, abuse, and addiction

Substance use disorder is a cluster of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms associated with the continued use of substances despite substance-related problems, distress, and/or impairment, such as impaired control and risky use.

Addiction is a state of psychological and/or physical dependence on the use of drugs or other substances, such as alcohol, or on activities or behaviors, such as sex, exercise, and gambling.

Adapted from the APA Dictionary of Psychology

Resources from APA

Science-backed interventions for problematic gaming

Evidence-based psychological interventions can help people with an excessive drive to play

Reclassification of cannabis is a win for researchers

Now deemed a less dangerous drug, scientists are optimistic that more studies on the benefits and risks of cannabis will be possible.

Substance use disorders in people with serious mental illness

Psychologists help these patients kick nicotine and other addictions

The emergence of psychedelics as medicine

Research confirms the potential of these drugs to help people with treatment-resistant mental health conditions

What APA is doing

Substance use disorders

APA Services advocates for policies, programs, and funding to improve the prevention and treatment of opioid and other substance use disorders, including nonpharmacological interventions for pain management.

Society for Psychopharmacology and Substance Use

APA’s Division 28 promotes teaching, research, and dissemination of information regarding the effects of drugs on behavior.

Society of Addiction Psychology

APA’s Division 50 promotes advances in research, professional training, and clinical practice within the broad range of addictive behaviors including problematic use of alcohol, nicotine, and other drugs and disorders involving gambling, eating, sexual behavior, or spending.

Addictive Behaviors

Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use in the Workforce and Workplace

Designing Interventions to Promote Community Health

Methamphetamine Addiction

Trauma and Substance Abuse, 2nd Edition

Magination Press children’s books

All the Pieces

Journal special issues

Combined Use of Alcohol and Cannabis

Brief Alcohol Interventions for Young Adults

Neuroimaging Mechanisms of Change in Psychotherapy for Addictive Behaviors

Sex Differences in Drug Abuse

Substance Use Disorders and Addictions

APA journals

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology