25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Meet top uk universities from the comfort of your home, here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- School Education /

Essay on My First Day in School: Sample in 100, 200, 350 Words

- Updated on

- Jan 23, 2024

Essay on My First Day in School: The first day of school is often considered an important day in every child’s life. It is a time of a mix of emotions, like nervousness, excitement, homesickness, feelings of shyness, and likewise. But did you know these feelings are responsible for making our day memorable?

As children, we all are like a blank canvas, easily dyed into any colour. Our first day in school is like a new world to us. As a child, we all have experienced those feelings. So, to make you feel nostalgic and refresh those special feelings, we have brought some samples of essay on my first day in school.

Master the art of essay writing with our blog on How to Write an Essay in English .

Table of Contents

- 1 Essay on My First Day in School in 100 words

- 2 Essay on My First Day in School Sample in 200 Words

- 3 Essay on My First Day in Day in School in 350 Words

- 4 FAQs

Essay on My First Day in School in 100 words

It was a cloudy day when I took my first step into the compound of my school. I was carrying a new backpack that was filled with notebooks. Though the backpack was a bit heavy, instead of focusing on the weight, I was excited about the beginning of my journey on my first day in school.

My classroom was at the end of the corridor. As I entered my classroom, my class teacher introduced me to the class and made me feel welcome. Activities like reading, solving problems in groups, and sharing our lunch boxes slowly and steadily transformed the new student with a sense of belonging.

The whole day progressed with mixed excitement as well as emotions. As the bell rang, declaring the end of the school day, the school felt like a world of possibilities where the journey was more than textbooks.

To improve your essay writing skills, here are the top 200+ English Essay Topics for school students.

Also Read: Speech on Republic Day for Class 12th

Essay on My First Day in School Sample in 200 Words

It was a sunny day and the sun was shining brightly. With my new and attractive backpack, I was moving through the school gate. It was my first day in school and I was filled with nervousness and excitement. From the tower of the building to the playground everything was bigger than life. As a school student, I was about to enter a new world.

The corridor was filled with the echo of students. As I entered the classroom, wearing a mix of curiosity and excitement, my classmates and class teacher welcomed me with a warm smile. After a round of introductions and some warm-up activities, strangers gradually started tuning into potential friends. At lunchtime, the cafeteria was filled with the smell of delicious food. However, I hesitated before joining the group of students but soon enough, I was laughing with my new friends and sharing stories. The unfamiliar were now my friends and transformed my mixed emotions into delightfulness.

The bell rang for the next class and I stepped out for new learning in my new academic home. My first day of school had many memorable stories, with old subjects and new introductions of knowledge. The day was spent learning, sharing and making new memories.

Also Read: Essay on Joint Family in 500+ words in English

Essay on My First Day in Day in School in 350 Words

My first day in school started by stepping onto the school bus with a bag full of books and a heart full of curiosity. It was like I was starting a new chapter in my life. After traveling a long way back, I stepped at the gate of my school. The school gate welcomed me with open arms and greeted me with a sense of excitement as well as nervousness.

As I entered the classroom, I found many new faces. Arranging my stuff on the seat, I sat next to an unknown, who later on turned into the best friend of my life. I entered my class with a welcoming smile, and later on, I turned everything in with ease. During our lunchtime, the cafeteria was filled with the energy of students.

At first, I hesitated to interact with the children, but later on, I was a part of a group that invited me to join the table. At lunchtime, I made many new friends and was no longer a stranger. After having delicious food and chit-chatting with friends, we get back to our respective classrooms. Different subjects such as mathematics, science, and English never left the same impact as they did on the first day of school.

The teacher taught the lessons so interestingly that we learned the chapter with a mix of laughter and learning. At the end of the day, we all went straight to the playground and enjoyed the swings. Moreover, in the playground, I also met many faces who were new to the school and had their first day in school, like me.

While returning home, I realised that my first day was not just about learning new subjects; it was about making new friends, sailing into new vibrant classrooms, and settling myself as a new student. The morning, which was full of uncertainty at the end of the day, came to an end with exciting adventures and endless possibilities. With new experiences, I look forward to new academic and personal growth in the wonderful world of education.

Also Read: Leave Letter for Stomach Pain: Format and Samples

My first day of school was filled with mixed feelings. I was nervous, homesick, and excited on the first day at my school.

While writing about the first day of school, I share my experience of beginning my journey from home. What were my feelings, emotions, and excitement related to the first day of school, and how did I deal with a whole day among the unknown faces, these were some of the things I wrote in my first day of school experience essay.

The first day of school is important because, as a new student, we manage everything new. The practice of managing everything is the first step towards self-responsibility.

Along with studying my favourite subjects, I share fun moments and delicious foods with my friends in school.

Parents are filled with emotions on the first day of their child. As school is the place to gain knowledge, skills, and experience, parents try their best to give their children the best academics they can.

Related Blogs

For more information on such interesting topics, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu.

Deepika Joshi

Deepika Joshi is an experienced content writer with expertise in creating educational and informative content. She has a year of experience writing content for speeches, essays, NCERT, study abroad and EdTech SaaS. Her strengths lie in conducting thorough research and ananlysis to provide accurate and up-to-date information to readers. She enjoys staying updated on new skills and knowledge, particulary in education domain. In her free time, she loves to read articles, and blogs with related to her field to further expand her expertise. In personal life, she loves creative writing and aspire to connect with innovative people who have fresh ideas to offer.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today.

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

January 2024

September 2024

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Have something on your mind?

Make your study abroad dream a reality in January 2022 with

India's Biggest Virtual University Fair

Essex Direct Admission Day

Why attend .

Don't Miss Out

9 Students Share How They Really Feel About Going Back to School

These students, plus one parent, open up about the wave of emotions that comes with starting a school year unlike any other we've experienced before..

Madeleine Burry

Jessica Fregni

Writer-Editor, One Day

Laura Zingg

Editorial Project Manager, One Day Studio

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to sweep across the country, students, families, and teachers are navigating the new normal of going back to school—while much of the country still shelters in place.

Some students are preparing for a return to remote learning. Others are still unsure of how exactly they will be attending school this year.

We spoke with a few students and their family members from different schools around the country to learn what school will look like for them this fall. They shared their personal experiences with remote learning and how they feel about going back to school in the middle of a pandemic.

Missing Everything About School

‘i just carry on about my day with no specific emotion’.

Syedah Asghar, College Sophomore, Washington, D.C.

Syedah Asghar will begin her second year of college at American University in Washington, D.C., where she studies public relations and strategic communications. After receiving some mixed messages over the summer about the status of her school reopening, Syedah recently learned that her school’s campus will remain closed for the fall semester. She plans to attend remote classes in a few weeks. And like many college students, she is grappling with staying motivated and missing out on the college experience.

College has been a safe space where I’m the most “me.” I would wake up much happier. I had confidence in my routine, and I was surrounded by friends who made me feel excited to start the day. With online learning, I just carry on about my day with no specific emotion.

The hardest part about attending college remotely is maintaining a routine and motivation. For in-person classes, I would get dressed and have to physically be present which put a start to my day. Now, I sometimes turn on my computer as soon as I wake up and not give myself the mental space ahead of time to start my day. On the plus side, with online learning, there is a lot more flexibility in my schedule since I’m able to complete an assignment on my own timeframe. Most of my professors are honoring mental health, and are more understanding of external factors that impact the quality of education now that we're learning remotely.

Being part of the Enduring Ideas Fellowship has kept me busy working 20 hours a week. I’m also trying to get creative by learning how to cook and attempting new recipes. With my friends, we’ve all been checking-in and making sure we’re able to support one another through these mentally-draining times. Only two of my professors have reached out and asked how we’re doing, so there isn’t much support on that end.

While it can be mentally challenging and exhausting, I’m very fortunate to have access to technology and internet connection so I can complete my coursework. And I’m able to stay at home and quarantine if need be.

Get more articles like this delivered to your inbox.

The monthly ‘One Day Today’ newsletter features our top stories, delivered straight to your in-box.

Content is loading...

‘I'm Hoping That Jose Goes Back, Even Though I Know It's Scary’

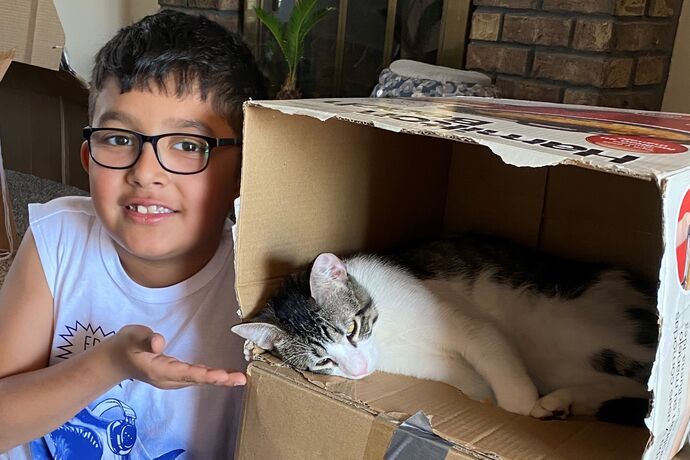

Marisol Escobedo & Jose Manrrique, 4th grade, Kansas City, Missouri

Fourth-grade student Jose Manrrique is returning to school at Carver Dual Language in Kansas City, Missouri, in September—virtually, for now. Schools in the Kansas City Public School System will not reopen for in-person instruction until the community’s COVID-19 cases decrease for at least 14 days. While Jose eagerly awaits the day when he can return to the classroom and see his teachers and friends again, his mother, Marisol Escobedo, feels much more conflicted.

Marisol: They're going to be starting online school first, on September 8th. They will do that for a couple of months while the cases keep decreasing, then they will start putting some of the kids back in school. I'm hoping that Jose goes back, even though I know it's scary at the same time for him to go. I'm really worried that he will get sick. I don't want to go through that, it scares me. But I really would like Jose to be able to develop his learning so that he can learn what he's supposed to in school.

I don't really think that Jose learned much from online classes. Even though I know that the teachers do their best to teach them as much as they can, I don't think it's the same for the kids.

Especially the younger ages, I think that it's hard for them to be able to teach them everything on a computer—especially because you have multiple children at the same time in the class. For an older student, like my sister, I know that she did really good because she's older. She's 16 and she already knows what she's doing. But for Jose, it was hard.

I'm hoping that they will make the school safe for students, to try to keep them as healthy as they can. I don't know what that process will be, but I'm hoping that everything that they do, they will plan it well.

Jose: I want to go back in the school building. I'm hoping that I can still play with my friends and also be in the same class with my friends.

Adapting to a New Normal

‘i have to push myself to get things done’.

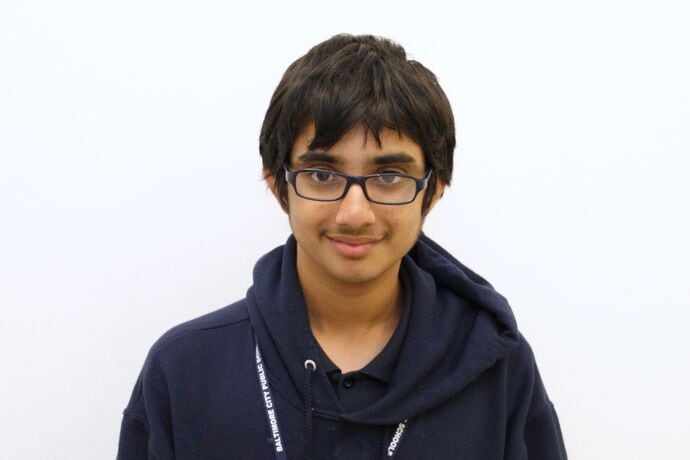

Haanya Ijaz, 12th Grade, Dublin, Ohio

Haanya Ijaz is a rising senior at Hilliard Davidson, in Dublin, Ohio where she will be attending remote classes in the fall. She’s also taking classes at Ohio State University, which will be solely online. While she finds in-person classes more interesting and also values the face-to-face time with friends, she knows online learning is safer, and also allows her to independently create a schedule that works for her.

Online classes are definitely a lot more organized this fall than before.

I also think I've gained skills with handling procrastination and sticking to a schedule, so I should be more organized this fall. [The hardest part about online learning is] staying interested and motivated. Without sticking to a schedule, I easily fall into a cycle of procrastination and feeling down, so I have to push myself to get things done and stay on top of my responsibilities.

Most of my classes should be done before 4 p.m., leaving me room to work on college apps and extracurriculars in the afternoon along with homework.

I also think I'll have more time for my personal hobbies and interests which have always been something that give me a break outside of academics and keep my mental health in check. I read a lot! I also sketch landscapes, my friends, and characters from my favorite shows. Recently I've gotten back into skateboarding after a one-year-long hiatus, which has been great.

[I feel worried about] college applications and the situation with the state-administered SAT. It's still very gray. [I’m hopeful about my] self-growth and exploration with this extra time at home! I am also looking forward to the remote internship opportunities I will be participating in this fall.

I would obviously love it if COVID-19 did not exist, but within the current parameters of the situation I'm excited for the courses I am taking and the extracurriculars I am involved in. I also have a huge list of books I need to get through, so staying at home is going to be great for that!

{ #card.dateline #}

Nothing Feels Normal Anymore

‘I Walked Out of My High School for the Last Time Without Knowing It’

Becoming a Teacher During the Pandemic

‘I’m Feeling Hopeful About My Ability to Sit in on More Online Classes’

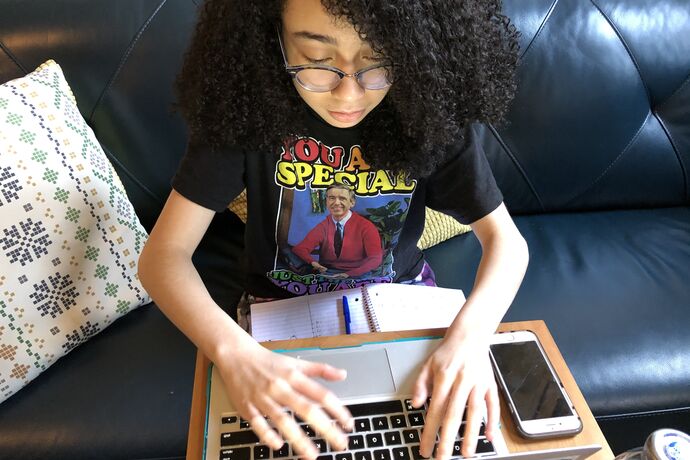

Annabel Morley, 12th Grade, Baltimore, Maryland

Annabel Morley is a rising senior at the Baltimore School of Arts. At least the beginning of Annabel’s final year of high school will be spent at home, where she will be learning remotely. Although Annabel worries about how engaging and supportive online learning will be this year, she’s found a silver lining: More time at home means that she has more time for her artistic pursuits which include writing for CHARM , an online literary magazine that amplifies voices of Baltimore youth and spending time with her family.

I’m not really sure yet what my school day will look like, but I know it will be entirely online. I definitely don’t think I would feel very safe going back to school in person unless CDC guidelines were followed really well. Both my parents are at risk and I wouldn’t want to put them, or my friends’ families, at risk.

The hardest part of attending school remotely is definitely not seeing any of my school friends in person and having some difficulty understanding the content. We have a lot less academic support. I’m most worried about understanding what's going on in my classes—especially in math. I hope that we can find a way for online schooling to be more engaging because it was very difficult to understand or stay focused on a class last spring.

Now that school is online, I definitely have more time to work on personal projects and interests. For example, I’ve started crocheting and oil painting, and have made a bunch of clothes. During quarantine, I've mainly been doing lots of crafts and baking, Facetiming, and having safe outdoor hangouts with my friends.

My mom and I are really close so it's been nice to be able to spend more time with her, and with all the Facetiming with my friends, I feel like I’ve been really loved and supported during this time. I’m feeling hopeful about my ability to sit in on more online classes and teach myself artistic and personal skills.

‘Honestly, I Would Prefer Learning in a Virtual Setting’

Amia Roach-Valandra, 12th Grade, Rosebud, South Dakota

Amia Roach-Valandra will begin her senior year of high school this fall on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. She is also an Enduring Ideas fellow, a student-led leadership initiative to reimagine the future of education. Amia's school will be online during the first quarter, with plans to reevaluate whether to open for in-person classes. Like many students and families, Amia is feeling anxious not knowing what lies ahead.

In this new school year, we are faced with challenges that we never had to face before. My high school reached a decision to go online for the first quarter and have a revaluation in nine weeks. As a student I feel in the dark about the decision that is being made, and anxious about it. If the school isn’t prepared yet, how do they expect students to be prepared?

Not having a normal school setting may not allow me to be the best student I can be. I’ll have the safety of my health top of mind instead of learning the curriculum. Honestly, I would prefer learning in a virtual setting, and being able to learn from the comfort of my own home. I know I would be able to stay on top of assignments, although I know some students may not feel the same.

I am also a student-athlete, and I am worried about my school's plan regarding sports. It is definitely a piece of my life that I would want to go back to normal, yet I want to be considerate of my health as well as others. A lot of students depend on sports as a place to escape for a while, and others depend on sports scholarships for college. I am also thinking about those students and how much that will impact them this school year.

‘My Overall Mental and Physical Health Improved Significantly’

Tehle Ross, 10th Grade, Baltimore, Maryland

Tehle Ross is a rising sophomore attending Baltimore City College and a contributor for CHARM , a digital magazine featuring voices of Baltimore youth. She loves studying history and plans to study abroad this year in Italy, a country that has made a remarkable recovery through the pandemic. Her Italian school will be a hybrid of online and in-person at the beginning of the year and Tehle is optimistic about transitioning to all in-person classes.

Attending school remotely has several benefits and shortcomings alike. Each family's living and working situation is different; however, in my personal experience, I noticed that my overall mental and physical health improved significantly when doing school online. I was less stressed because I was able to space out my work as I desired, and I also was able to complete every assignment from the comfort of my own home. Attending school remotely stunted my academic progress, though, I believe, for I am a more focused student when instruction takes place in the classroom with my peers.

The hardest part of attending school remotely was the social isolation from my classmates and teachers. At school, you always feel like you have a community around you, and it is tough to not feel that same sense of community when learning online at home. Additionally, it takes an innate sense of motivation to get assignments done in a timely manner when you are doing work online.

Quarantine has been tough for us all, but I cope and stay busy by doing what makes me happy. I have developed a passion for baking, and I have also been an avid reader and writer. Having game nights with my family and watching movies together lifts my spirits.

My community has been supporting me during this time by checking up on me and staying in touch virtually. Supporting others during this time means prioritizing their safety.

Interested in Joining Teach For America?

SEE IF YOU QUALIFY

Worries and Hopes About the Next Chapter

‘this pandemic is serious, but people have stopped taking it seriously’.

Shubhan Bhat, 11th Grade, Baltimore, Maryland

Shubhan Bhat will also begin 11th grade this fall at The Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. He enjoys poetry, writing for CHARM magazine, and studying American government. His school will hold online classes this fall and possibly offer a hybrid option later on. Shubhan prefers remote learning because it’s less stressful and safer for students. But being at home while trying to learn has also been very difficult for Shubhan and his family.

With remote learning, I gained more time to finish my work, had less stress, and more free time. What is lost is the social aspect of the classes, which is fine with me. I’m hopeful that online classes will be safer than an in-person school and there will be less work.

The hardest part about attending school remotely is being in the house when events happen. I was in my English class when the paramedics came to my house to try and revive my grandfather. I watched my grandfather die right in the middle of class. At that point, because my maternal grandfather also died a month ago, I lost all my motivation to be in class or do work. I left class, and haven’t come back since.

I’ve been getting support through classes and therapy. My family tries to work together on activities so I won’t be depressed during quarantine. My teachers also made my classes optional last spring so that decreased my stress. I don’t really have a lot of friends or go on social media as much as I used to. It used to entertain me, but it’s starting to get boring.

I wish schools in Texas and Florida wouldn't be in-person. I find that in-person classes during the pandemic aren't safe because students are going out in public and have a greater risk of spreading COVID. This pandemic is serious, but people have stopped taking it seriously. And now there is an increase in cases.

‘I Fear All of My College Plans Will Go Out the Window’

Me’Shiah Bell, 11th Grade, Baltimore Maryland

Me’Shiah Bell is a rising 11th grader at Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, where students will continue to receive remote instruction this fall. While Me’Shiah believes that remote learning is the best and safest option for now, she worries about what remote learning will mean for her college plans—especially since she’s entering her junior year, a critical time for college admissions. In her free time, Me’Shiah also writes for CHARM online magazine.

I think remote learning is the best option, as it is the safest. However, I think there are quite a few downsides.

I miss the social interactions, but I realize that it’s unimportant in the long run. The main downside for me is the lack of clarity and communication between the students and teachers. For example, last spring I had a grading error that would have been fixed immediately if I was physically at school. However, since I wasn’t there, there was no sense of urgency, and my concern was disregarded by multiple adults. This caused the situation to be pushed over for much longer than it should’ve been.

Hopefully, this fall we’ll have a better system to avoid issues like this. I also hope classes will be scheduled like a typical school day, with multiple sessions in a row, and independent work to do between classes. Last spring, teachers could decide if and when classes sessions were held, and everything was very unorganized. Sometimes, the sessions would overlap with other responsibilities I had.

The hardest part of remote learning has been keeping myself motivated and holding myself accountable. I’m going into my junior year, which is probably the most important year for college admissions, and I don’t feel like I’m able to put my best foot forward. I’ve worked hard to get to the point I’m at now, and I fear that all of my college plans will go out of the window due to circumstances out of my control.

Overall, I’m worried about how prepared I am mentally to adjust to such a huge change, while still continuing to perform well academically. I’m hopeful that my school will be more prepared to accommodate all of our needs so that everyone can have the best possible experience.

‘I Think COVID Gave Me a New Story to Tell the Next Generation’

Rosalie Bobbett, 12th Grade, Brooklyn, New York

This August, Rosalie Bobbett will begin her senior year at Brooklyn Emerging Leaders Academy (BELA). The first three weeks of school will be held online, after which she will alternate one week of in-person classes and one week of remote learning. Rosalie lives with her parents, siblings, grandmother, and uncle so she’s been extra cautious about quarantining. Going back to in-person classes will be a big adjustment. But she’s ready.

My school is really on top of safety. They're going to make us wear masks. And we have to get a COVID test before we enter the school building. For in-person classes, we're going to stay in one room with 12 other people. The teachers have to rotate to us instead of us traveling in a big group.

I think with online learning, it gives me an opportunity to move at my own pace and take accountability for my learning. The disadvantages are the lack of talking to people and being in the classroom. I'm very fortunate to be in a school where I have a computer. I know how to work Zoom. I know how to work from Microsoft. Most of my peers don’t even have a computer. And so I'm wondering—how are those students navigating this world right now?

I feel like a lot of students are going to be left behind because of resources or their parents—there might be other children in the home and it's going to be difficult for them to take care of their siblings. The teachers and principals and people who are responsible for their education—I don't want them to lose sight of that child who is behind the screen.

I’m excited about school. It's my senior year. This is the last chapter before entering my adulthood. I think COVID gave me a new story to tell the next generation. It's going to be a lot of mixed emotions, but I know my teachers are going to make my senior year the best that they can.

More Community Voices

“ COVID-19: Community Voices ” offers a glimpse of life and learning during the coronavirus school closures, in the words of students and parents in the communities we serve.

If you'd like to tell your story or would like to suggest a story for us to cover, please email us .

Sign up to receive articles like this in your inbox!

Thanks for signing up!

- Student Voices

- School Life

Related Stories

How Proposition 308 Could Open Higher Education to Thousands of Students in Arizona

Voters in Arizona have the chance to offer thousands of immigrant students access to in-state tuition this November. In this video, one student explains how the proposition could change lives.

Aggie Ebrahimi Bazaz

Managing Director, Film + Video Projects

Joel Serin-Christ

Director of Studio Production & Impact

Faviola Leyva

Video Producer

The Young Activists Guide to Making Change

After three years of hard work led by youth activists and local organizations, Hawai'i students will have access to something new to meet their essential needs: free period products in school.

Leah Nichols

‘It Really Stings’: Students Fighting Book Bans Talk About the Harm They Cause

Students leading the charge against book bans say that these challenges are causing a strain on their mental health and learning environment.

Georgia Davis

Associate Editor

The first day of school: how COVID-19 has changed our schools and how we can be public supporters of public education

Assistant professor of social studies education william toledo looks at the changes coming this back-to-school season.

In just a few days, public schools in Reno and across Northern Nevada will reopen their doors to K-12 students. The first day of school is often met with some anxiousness and excitement from teachers, parents, and students, as they consider the challenges and successes they will encounter over the course of the school year.

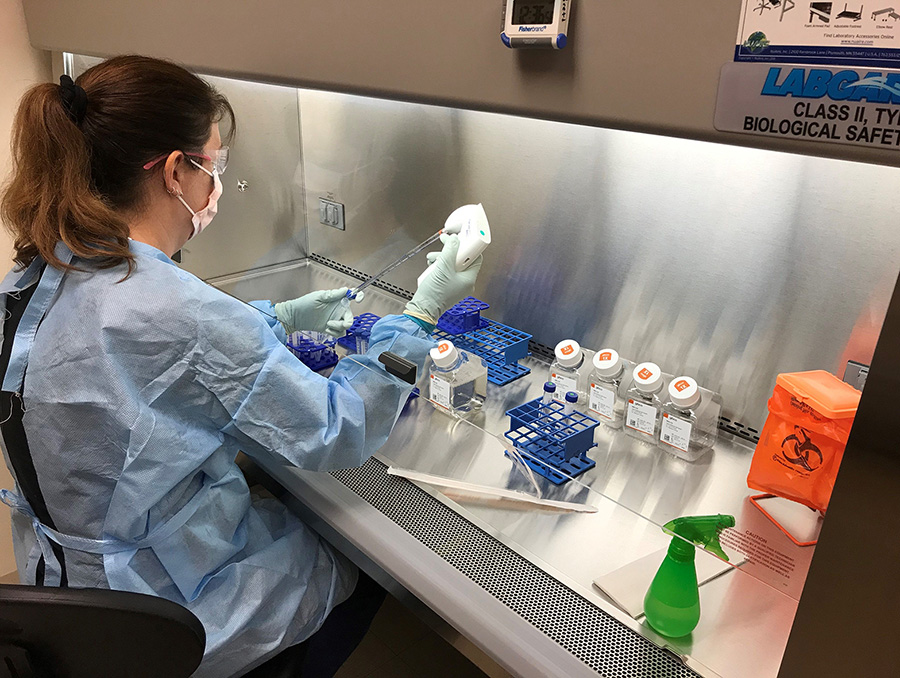

However, this year brings with it a whole new set of challenges. Since March 2020, the world has struggled to adapt to and deal with COVID-19, a dangerous novel virus still with many unknowns [1] . As researchers continue to study COVID-19, we are finding answers to some of our questions, including an important one as schools open: yes, young people can carry, transmit, and catch COVID-19 [2] . Which leads to an important new question: how does COVID-19 change the profession of teaching?

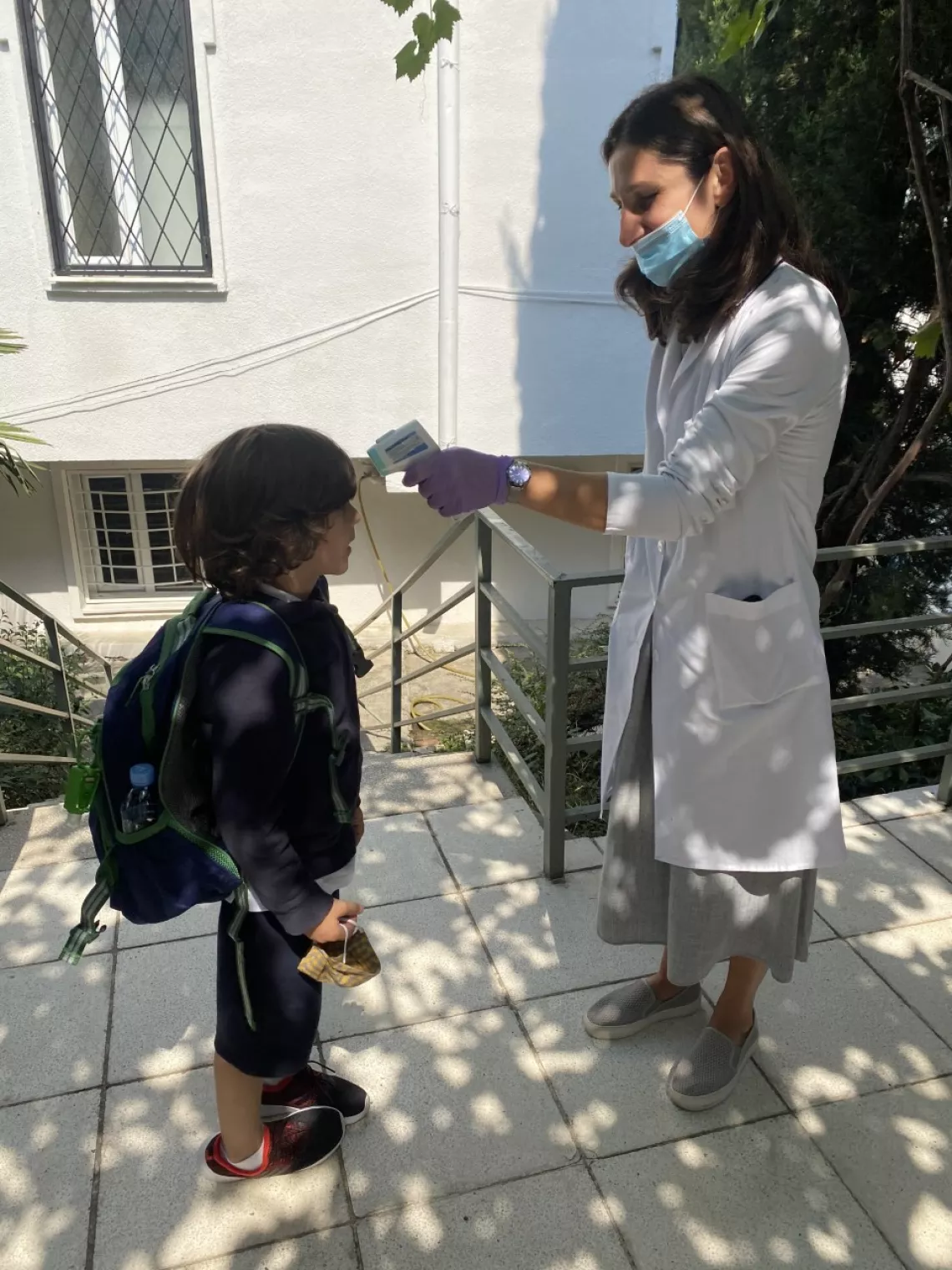

The first change is the most important one: schools must be physically safe for students’ and educators’ return . Safety in the era of COVID-19 encompasses many factors, an important one being the percentage of positive COVID-19 tests within a county or city. The American Federation of Teachers states that in-person school is safe only when fewer than 5% of coronavirus tests in an area are positive [3] . Beyond this important statistic, NPR reports that there are a variety of factors that should be in place as public schools open: 6-feet of physical distance between desks, small class sizes, consistent, mandatory mask policies for adults and children, frequent replacement of HEPA filters in air ventilation systems, and more. It is key that teachers, parents, and community members examine their district’s reopening plan to determine if a district is ready to open safely. If not, encourage the district to implement strict safety protocols and to only open when COVID-19 numbers are sufficiently low in a community.

Second, teachers face an enormous pedagogical change: educators must meet the needs of in-person and remote (online) learners, sometimes simultaneously . This is a big undertaking for our teachers and educational support staff as districts try to iron out specific plans for what the physical structure of schools will look like. For teachers, there are different steps to take to help with a smooth transition to new blended class formats: using similar or the same curricular materials and sequencing for in-person and remote learners [4] , facilitating student engagement with one another from safe social distances and online [5] , and relying on one another for support and guidance. In a world of “physical distancing,” it is important for teachers to not “socially distance” from one another. Educators should stay connected, and rely on one another for support and collaboration as they adapt to new modes of instruction.

Third, and closely related to each of the first two points: we must all be generous with ourselves and one another as we enter uncharted waters . The fall 2020 return back to school is not going to be “business as usual,” and we must all be flexible. It is quite likely that some schools will open, and close, possibly even more than once. It is also quite likely that mistakes will be made, and that safety protocols need to be amended or adjusted. A key to the success of our public schools during COVID-19 is public support. It is important that parents and community members be flexible and understanding of this shift as educators begin teaching in the midst of what is currently uncharted territory. Additionally, it is key for teachers to be generous with themselves; we are currently asking a great deal of our educators, working in already underfunded public schools. They are now being asked to return to the classroom as frontline workers, and they deserve and have earned public support. We must listen to teachers, and what they tell us about what is or isn’t working as schools reopen, and adjust accordingly.

There is no doubt about it: COVID-19 presents a significant challenge for public education. However, as we have seen time and time again throughout history, our teachers are resilient; they are qualified; and they are doing one of the most crucial jobs in the world: preparing future generations of citizens to engage in an everchanging and evolving society. If you are a teacher, please know this: your community supports you. If you aren’t a teacher yourself, make sure a teacher gets the message: we have your backs, and we are in this together.

- What We Know and Still Don’t Know About COVID-19 by Carla Cantor and Caroline Harting (July 22, 2020).

- Nearly 100k children tested positive for COVID-19 in last two weeks of July by Ben Kesslen (August 10, 2020)

- How Safe Is Your School's Reopening Plan? Here's What To Look For by Anya Kamenetz, Patti Neighmond, Jane Greenhalgh, Allison Aubrey, & Carmel Wroth. (August 6, 2020)

- How to Make Lessons Cohesive When Teaching Both Remote and In-Person Classes by Sarah Schwart (August 5, 2020)

- How to Make Lessons Cohesive When Teaching Both Remote and In-Person Classes by Sarah Schwartz (August 5, 2020)

William Toledo is an Assistant Professor of Social Studies Education in the College of Education at the University of Nevada, Reno. Dr. Toledo's research focuses on (a) social studies education in pre-K-12 classrooms and (b) the experiences of LGBTQ+-identifying teachers in public schools.

By: William Toledo, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Social Studies Education

Libraries IDEA Committee to celebrate PRIDE through student art

Libraries IDEA Committee to celebrate “What does PRIDE mean to you” through student art contest

Finding and catching endangered frogs in Panama

A University team of women scientists traveled to El Valle de Antón for ongoing research on a pathogen killing different amphibian populations

Living The Wolf Pack Way: Outstanding Letter of Appointment winner Jocelyn Mata’s journey

Jocelyn Mata describes how family, hard work and opportunity led her to become an oncology social worker with Renown Health and teach in the School of Social Work at the University of Nevada, Reno

Biomedical Research Awareness Day BRAD 2024

Bradley Ferguson encourages you to stop by the info table and come to a lunch-and-learn session April 18 to celebrate #BRADGlobal

Editor's Picks

Anthropology doctoral candidate places second in regional Three-Minute Thesis Competition

A look at careers of substance and impact

NASA astronaut Eileen Collins shares stories at Women in Space event

University of Nevada, Reno and Arizona State University awarded grant to study future of biosecurity

Nevada Today

A brilliant light of leadership shines at the University of Nevada, Reno | Una brillante luz de liderazgo brilla en la Universidad

Karla Hernández, Ph.D., awarded the 2024 Inclusion, Equity, and Diversity Leadership Award

College of Education and Human Development prepares secondary school educators to teach collegiate courses

College expands to offer a new online Master of Education with an emphasis in Continuing Educator Improvement program

Manager of food systems programs brings global experience and perspectives to Desert Farming Initiative

Hosmer-Henner aims to use his unique blend of experience to help strengthen state’s food systems

Sagebrushers season 3 ep. 2: Executive Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Melanie Duckworth

President Sandoval welcomes new leader who will guide university efforts to enable inclusive excellence for students, faculty and staff

Making their MARC: Yajahira Dircio

Dircio is one of four students in the second MARC cohort

Researchers develop innovative method of teaching self-help skills to preschoolers who are deafblind

Study demonstrate the effectiveness of System of Least Prompts (SLP) as part of an intervention

Researchers and students gain new insights and make new connections in Panama

Student participants join researchers to support international conservation efforts

The University of Nevada, Reno Orvis School of Nursing ranks as top nursing program in the country

2023 National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX®) nursing graduate passing rates place the University at the top of the charts in the state and country

- LATEST INFORMATION

- High contrast

- Our Mandate

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child

- UNICEF Newsletter

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Multiple Cluster Survey (MICS)

- Partnerships and Ambassadors

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Going back to school during the covid-19. - voices of children, children tell about their feelings and challenges they face.

- Available in:

Starting a new school year is always full of emotions and especially during a pandemic.

Part of the schools in Georgia started teaching at classrooms, other part continues the distance learning. But children in every city or village are looking forward to meet their friends and teachers in person.

We asked children to tell what they feel, how their lives have changed and how they handle these challenges.

Natia Samnashvili, 10 years old.

"I am happy to return to school. Distance learning was hard, working with computer caused pain for eyes and fingers. I could understand the online lessons, but it was easier when we had face-to-face meetings with the teacher. One more thing I am happy about is to see my friends, meet new teachers. If the lessons were distance again, we won't have a chance to get introduced with teachers. We have new teachers this year."

Andria Khocholava, 9 years old.

"Don’t remind me about online lessons. Going to school is cool. There are many changes though: you can’t hug the teachers, they always wear masks, hugging friends is not allowed either, but we violate this rule sometimes. Breaks are shortened and we have to wash our hands many times. Also, you are not allowed to lend something to others. I am carrying water in the bottle as the water dispensers are turned off. Still, it’s good to go to school. We are repeating the materials from the previous year and I understand everything better in class than on the online lesson. We have a new game called “Coronobana” – it’s like a game of catch."

Teona Jghiradze, 13 years old.

"I didn’t have a personal computer and was attending online lessons from a mobile phone. We had to either write the homework in the workbook and then send the photo of it or type it on the keyboard. Sometimes there were technical problems with the internet or electricity and we were missing the lessons, now we will cover those materials too. I am happy to return to school, it was boring at home and also I missed my friends and I am happy to see them."

Lasha Devlarishvili, 11 years old.

"Yes, I am happy to return to school. It was boring at home. I was playing or reading books. In school, there will be more positivity and better learning process".

Elene Melikadze, 12 years old.

"Online classes were interesting at the beginning, but now I think going to school is better. We could only see the face of the teacher at online lessons, eyes were getting tired and you miss the human interaction. But it was good that the exams were cancelled.

Now I am back to school. My friends got taller in this period. I am happy to return to school because I can see the people and talk to them. I am having fun on breaks, but we all remember that we must be careful. We have to avoid getting the virus or transfer it. Yes, we have lots of homework, but I don't complain. I like school and I am happy. If the online lessons are back, I don't know what will I do. I think I will start drawing instead of studying."

Data Sulaberidze, 10 years old.

"I am happy to return to school because I really missed my friends and teachers. I love school and I think that interaction with my peers is part of the education process."

Nino Khvichia, 10 years old.

"I am very happy to go back to school. I was very nervous on the first day about the mandatory distance, and I was looking forward to hug everyone, I missed everyone so much. I am getting up early in the mornings not to be late and get to school early. Sometimes I was forgetting about the lessons when we were on distance learning and could not join the classes, could not interact with children normally and sometimes I was shy to ask questions. I love the lessons held in school, they are more interesting and joyful."

Giorgi Alavidze, 6 years old.

"School is good. Very good. It is fun there. There are many friends of mine from kindergarten. We have two new students too and I made friends with one of them. From lessons, I like Georgian more than math, teachers read books and it is like a literature club. I like drawing club too. I want the breaks to be longer to have more time for playing with friends. I want to go to school by school-bus and make friends with more people. Teachers were masks and gloves at school. I know if anyone catches the virus in school, it will be closed again."

Aleksandre Alasania, 7 years old.

"I was happy to return to school. It was different though, our class was split into half. We wore masks and maintain the distance, and we could not play and "go crazy".

When we turned back to distance learning, I was very upset. I am not able to communicate with friends and miss them. The software is always laggy during the lessons, I can't hear the voice well. When everyone starts to talk together, I am getting tired and turning off the software. We again have to sit at home to avoid getting infected by "Conora" (he calls Coronavirus like that)."

Related topics

More to explore.

On International Day of Education, UNICEF calls for increased focus on equal access to quality education in Georgia

Partnership initiative highlights the support provided for strengthening inclusive education in Georgia

How to prepare your child for preschool

Playful ways to ease the transition.

Beyond the Classroom

How interactive catch-up classes are changing academic performance for children in Georgia

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Back to School amidst the New Normal: Ongoing Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Children’s Health and Well-Being

Elizabeth Williams Published: Aug 13, 2021

- Issue Brief

As millions of children across the nation prepare to go back to school this fall, many will face challenges due to ongoing health, economic, and social consequences of the pandemic. Children may be uniquely impacted by the pandemic, having experienced this crisis during important periods of physical, social, and emotional development, and some have experienced the loss of loved ones. Further, households with children have been particularly hard hit by loss of income, food and housing insecurity, and disruptions in health care coverage, which all affect health and well-being . Public health measures to reduce the spread of the disease also led to disruptions or changes in service utilization, difficulty accessing care, and increased mental health challenges for children. Young children are still not eligible for vaccination, and though children are likely to be asymptomatic or experience only mild symptoms, they can contract COVID-19. Children may face new risks due to the rapid spread of the Delta variant, and some children who contract COVID-19 experience long-term effects from the disease. Many of these effects have disproportionately affected low-income children and children of color, who faced increased health and economic challenges even prior to the pandemic. This brief examines how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the health and well-being of children, explores recent policy responses, and considers what the findings means for the back-to-school season amidst new challenges due to the recent increase in cases and deaths. Key findings include:

- During the pandemic, some children experienced disruptions in routine vaccinations or preventive care appointments and difficultly accessing care, particularly dental and specialized care. Use of telemedicine has increased but not enough to offset declines in service utilization overall.

- Children’s mental health service utilization declined amid elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological stress for children and parents.

- Households with children have experienced significantly higher rates of economic hardships throughout the pandemic compared to households without children, leading to increased barriers to adequately addressing social determinants of health. Black, Hispanic, and other people of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic’s economic effects.

- Though the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 is lower for children than adults, over 43,000 children are estimated to have lost a parent due to COVID-19, with Black children being disproportionately impacted by parent death.

- Most children are likely to be back in the classroom this fall, but many still face health risks due to their or their teachers’ vaccination status. Some states and school districts are beginning to announce mask or vaccine requirements while others are banning vaccine or mask mandates for schools.

Recent policy developments, most notably the American Rescue Plan Act and the American Families Plan, attempt to alleviate some of the existing and pandemic-induced issues impacting children’s health and well-being. However, there is still uncertainty around what back to school will look like this fall, and the transition to “the new normal” may be more difficult for some. Schools, parents, and policymakers may face additional pressure to address the ongoing effects of the pandemic on children.

Children’s Health Care Disruptions and Mental Health Challenges

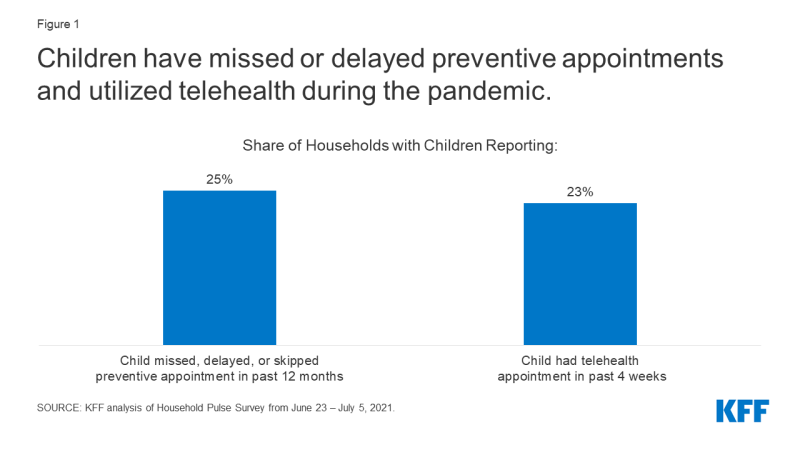

The pandemic has led to delays in child vaccinations and preventive care. KFF analysis of the Household Pulse Survey from June 23 – July 5, 2021 estimates 25% of households with children have a child who has missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months due to the pandemic (Figure 1). Preliminary Medicaid administrative data confirms this pattern, showing that when comparing March 2020 – October 2020 to the same months before the pandemic in 2019, there were approximately 9% fewer vaccinations for children under 2 and 21% fewer child screening services. Rates for primary and preventative care among Medicaid beneficiaries show signs of rebounding in more recent months with service use reflecting pent-up demand, but it is unclear whether this trend will continue and make up for the millions of services missed early in the pandemic. Another recent study similarly reports vaccinations for all children declined sharply after March 2020. The study also finds vaccinations have completely recovered for children under 2 but have only partially recovered for older children.

Figure 1: Children have missed or delayed preventive appointments and utilized telehealth during the pandemic

Children also experienced difficulty accessing and disruptions in specialty and dental care. Parents have reported delaying dental care or difficulty accessing dental care for their child, and there were 39% fewer dental services for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under 19 when comparing the pandemic months March 2020 – October 2020 to the same months in 2019. Children with special health care needs experienced difficulties accessing specialized services , especially services that could not be conducted via telehealth.

Children’s utilization of telemedicine services has increased since the pandemic, but the increase has not offset the decreases in service utilization overall. Preliminary data suggest that telehealth utilization for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under 19 increased rapidly in April 2020 and remains higher than before the pandemic. 23% of households with children surveyed by the Household Pulse Survey from June 23 – July 5, 2021 reported a child having a telehealth appointment in the past 4 weeks (Figure 1). Throughout the pandemic, the federal government and states have taken action to expand access to telehealth services. While telehealth utilization has increased, the increase has not offset the decreases in service utilization overall, and barriers to accessing health care via telehealth may remain, especially for low-income patients or patients in rural areas.

Children’s mental health and mental health service utilization has worsened since the start of the pandemic. The pandemic caused disruptions in routines and social isolation for children, which can be associated with anxiety and depression and can have implications for mental health later in life. Also, research has shown that as economic conditions worsen, children’s mental health is negatively impacted. Parents with young children reported in October and November of 2020 that their children showed elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological stress and 22% experienced overall worsened mental or emotional health. Recent studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) find children’s emergency department visits increased during the pandemic for mental health-related emergencies and suspected suicide attempts by children ages 12 to 17. At the same time, mental health service utilization has declined, with preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries suggesting there have been approximately 34% fewer mental health services when comparing the pandemic months March 2020 – October 2020 to the same months in 2019. Private mental health care claims also decreased from 2019 to 2020. There has been an increase in access to mental health care through telehealth, but there remain technological and privacy barriers to accessing mental health services via telehealth for some children.

Parental stress and poor mental health due to the pandemic can negatively affect children’s health. A previous KFF analysis finds economic uncertainty has led to increased mental health challenges, especially for adults in households with children and specifically mothers in those households. Further, 46% of mothers who reported a negative mental health impact due to the pandemic were not able to access needed mental health. Parental stress can negatively affect children’s emotional and mental health, harm the parent-child bond , and have long-term behavioral implications . Maternal depression can worsen child health status and lead to less preventative care. Additionally, parental stress and financial hardship can lead to an increased risk of child abuse and neglect. Early evidence shows declines in child abuse during the pandemic, though it is unclear if that is due to decreased reporting or due to social policy interventions during the pandemic. Children’s existing and pandemic-induced mental health challenges may have implications for the transition back to school and indicate children may need additional mental health support when they return to school.

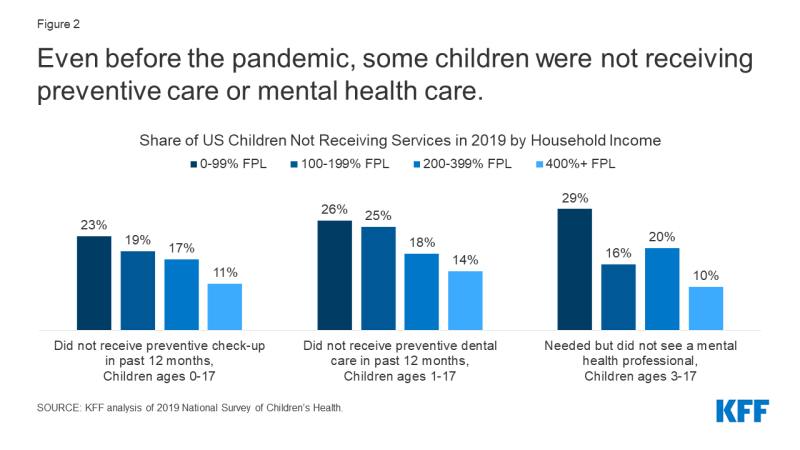

Pandemic-related challenges in children’s access to health care built on a system that was sometimes not meeting needs even before the pandemic, especially for low-income children . In 2019, 23% of children living in households with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) were estimated to have not received a preventative check-up in the past 12 months and 26% did not see a dentist for a preventive visit during the past 12 months (Figure 2). Some children with mental health needs were not receiving care, with an estimated 29% of the lowest income children who needed mental health services not able to access care (Figure 2). The pandemic may have made it even more challenging for children already experiencing difficulties accessing care and likely worsened existing disparities in access to needed care for children of color, children with special health care needs, children in low-income households, and children living in rural areas.

Figure 2: Even before the pandemic, some children were not receiving preventive care or mental health care

The Economic Downturn and Children’s Well Being

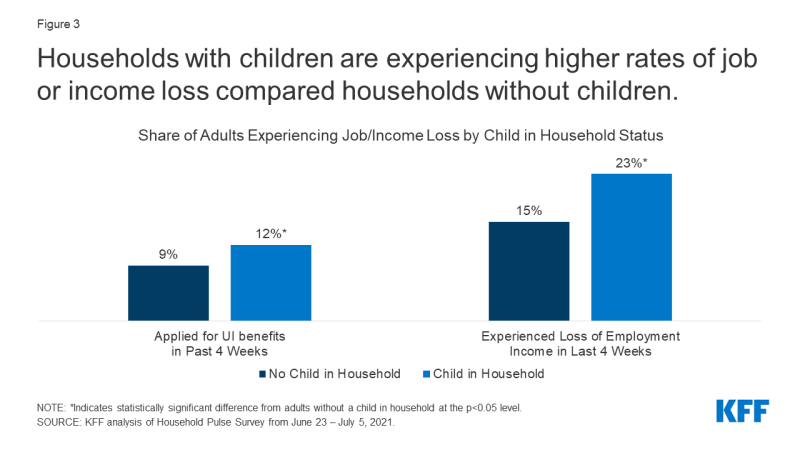

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many families with children were faced with unemployment and income loss and continue to face economic hardship. Throughout the pandemic, households with children were consistently more likely to report job or income loss, with more than half of households with children reporting losing income between March 2020 and March 2021. 1 While national indicators signaling job and income loss have moderated in recent months, they are still not at pre-pandemic levels. KFF analysis of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey from June 23 – July 5, 2021 found 12% of adults with children in the household applied for Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits and 23% experienced loss of income in the past 4 weeks (Figure 3). These rates were significantly higher compared to adults without children in the household.

Figure 3: Households with children are experiencing higher rates of job or income loss compared households without children

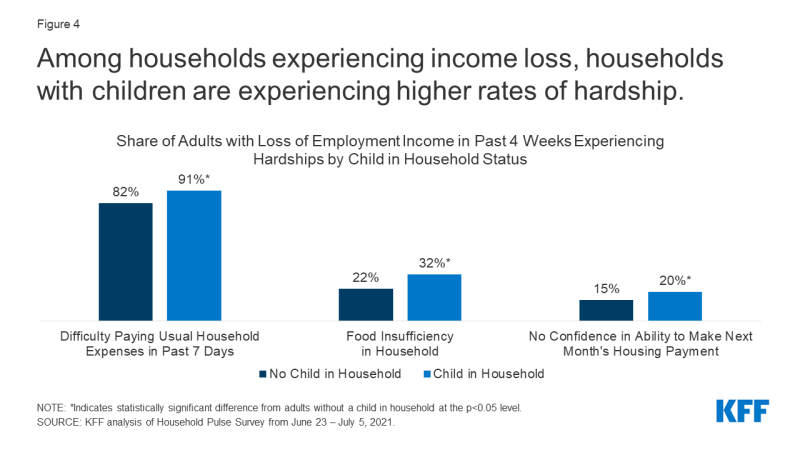

Loss of family income affects parents’ ability to provide for children’s basic needs. KFF analysis of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey also found that among adults reporting income loss in the past 4 weeks, 91% of adults with children in the household reported difficultly paying for expenses in the past week, 20% reported not having confidence in their ability to make their next month’s housing payment, and 32% reported food insufficiency (Figure 4). All of these rates are significantly higher for adults living in households with children than adults living in households without children. A large body of research shows that economic instability is a social determinant of health outcomes for children.

Figure 4: Among households experiencing income loss, households with children are experiencing higher rates of hardship

Further, Black, Hispanic , 2 and other households of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and its economic effects. In 2019, Black and Hispanic children were nearly three times more likely to be living in poverty than Asian and White children, and food insufficiency rates before the pandemic were three times higher for Black households and two time higher for Hispanic households when compared to White households. A recent report found Hispanic and Black households with children have experienced almost double the rate of economic or health-related hardships during the pandemic compared to White and Asian households with children. Overall, child poverty rates children have increased during the pandemic, especially among Hispanic and Black children.

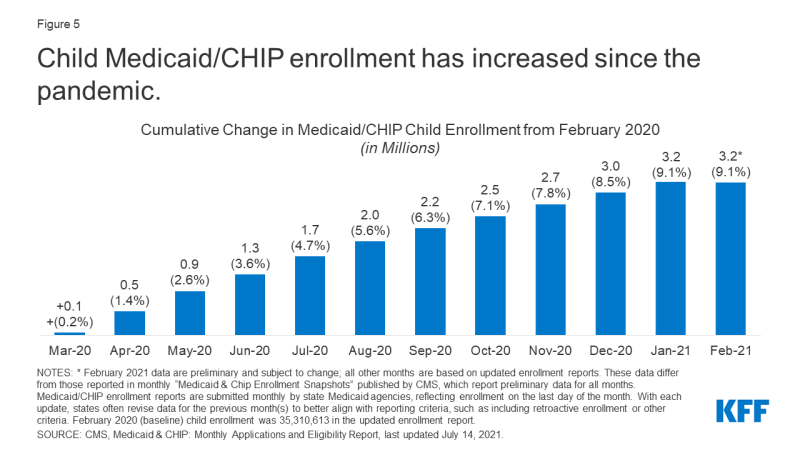

Job and income loss may lead to disruptions in children’s health coverage, though increased coverage through Medicaid and CHIP is likely offsetting much of that decline. Roughly 2 to 3 million people between March and September 2020 have lost employer health benefits, a trend that built on years of coverage losses among children. From 2016 and 2019, the rate of uninsured children in the US started to increase despite reaching the lowest rate in history (4.7%) in 2016, with the rate of uninsured Hispanic children increasing more than twice as fast as the rate for non-Hispanic youth. Loss of coverage or coverage interruptions can negatively impact children’s ability to access needed care. 3 , 4 , 5 During the pandemic, Medicaid and CHIP provided a safety net for many children. Administrative data for Medicaid show that children’s enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP has increased between February 2020 and February 2021, a total increase of 3.2 million enrollees, or 9.1%, from child enrollment in February 2020 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Child Medicaid/CHIP enrollment has increased since the pandemic

Children’s Health and COVID-19

While likely to be asymptomatic or experience only mild symptoms, children can contract COVID-19. Preliminary data through July 29, 2021 show there have been over 4 million child COVID-19 cases, and children with underlying health conditions may be at an increased risk of developing severe illness. Though a small percentage, some children who tested positive for the virus are now facing long haul symptoms , with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) the most-common complication that has impacted 4,000 children as of June 2, 2021 . It is unclear how long symptoms will last and what impact they will have on children’s long-term health. Cases have risen in recent weeks due to the Delta variant, and children are making up an increasing share of new cases, with children making up 19.0% of cases for the week ending in July 29 compared to 14.3% since the pandemic began. Hospitalizations of children with COVID-19 have also been rising since early July, reaching 216 children, on average, being admitted to the hospital every day for the week of July 31 – August 6, 2021.

Eligible children have lower vaccination rates than the adult population, and some children remain ineligible for a vaccine. Children 12 and up are now able to be vaccinated against COVID-19, which reduces the risk of adolescents contracting, spreading, or experiencing severe symptoms from COVID-19. Approximately 37% of children ages 12-15 and 48% of children ages 16-17 have received at least one vaccine dose as of July 26, 2021. These rates are lower than the adult population, which reached 70% as of August 2, 2021. There is currently no COVID vaccine for children under the age of 12, so some risk remains for that population to contract and spread the virus. Vaccine clinical trials are currently underway for children under 12, with authorization expected by the end of 2021. The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor recently reported that almost half of parents of children ages 12-17 say their child has received a COVID-19 vaccine or they intend to get them vaccinated right away. The report also found that parents’ vaccination intentions for their children are largely correlated with their own vaccination status and those who say their child’s school provided information on or encouraged COVID-19 vaccines are more likely to report their child has received a vaccine. The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor also found that parents are more cautious when it comes to vaccinating their child under 12, with about a quarter saying they would get their child between the ages of 5 and 11 vaccinated right away once the vaccine is authorized and four in ten saying they would wait and see.

Some children have experienced COVID-19 through the loss of one or more family members due to the virus. A study estimates that, as of Feb. 2021, 43,000 children in US have lost at least one parent to COVID-19. The study also finds Black children represent only 14% of children in the US but 20% of children who have lost a parent, and low-income communities and communities of color overall experienced higher COVID-19 case rates and deaths . Losing a parent can have long term impacts on a child’s health, increasing their risk of substance abuse, mental health challenges, poor educational outcomes , and early death . Further, the death of a loved one from COVID-19 may have occurred amid increased social isolation and economic hardship due to the pandemic. Estimates indicate a 17.5% to 20% increase in bereaved children due to COVID-19, indicating an increased number of grieving children who may need additional supports as they head back to school in the fall.

Policy Responses

Several policies passed during the pandemic provided financial relief for families with children. To address the economic fallout of the pandemic, the federal government passed relief bills that included direct financial relief for families, and evidence suggests material hardships that affect health, such as food insufficiency and financial instability, declined following stimulus payments. In addition, the March 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) included targeted aid to families with children through the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The ARPA is projected to decrease the number of children living in poverty by over 40%, with the expanded CTC now reaching children previously too poor to qualify and giving families in the lowest quintile an average income boost of $4,470. Alleviating child poverty is associated with improved child health outcomes such as healthier birthweights, lower maternal stress, better nutrition, and lower use of drugs and alcohol.

Other recent policies directly target children’s health coverage or access to health care. To address health care coverage, the ARPA extended eligibility to ACA health insurance subsides for people with incomes over 400% of poverty and increased the amount of assistance for people with lower incomes. The ARPA also included incentives for states to expand Medicaid for low-income adults under the ACA and extend Medicaid postpartum coverage for up to 12 months, both of which could benefit the health and well-being of families. 6 , 7 The Child Tax Credit, expanded by the ARPA, is not taxable income, so expanding the tax credit will not count toward Medicaid eligibility . To address access to health care challenges, the federal government and many states are making policy changes to permanently expand access to telehealth services. In their most recent report to congress , the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) recommended more coordinated efforts by agencies to address the design and implementation of benefits and improve access to home and community-based behavioral health services for Medicaid/CHIP children with significant mental health needs. In addition, the Biden Administration created a program to provide relief for COVID-19 related funeral costs, but targeted services for bereaved children were not included.

Back to School

Most children are likely to be back in the classroom this fall, but many still face health risks due to their or their teachers’ vaccination status and increasing transmission due to the Delta variant. The vast majority of schools, 88% of schools with 4 th grade and 89% of schools with 8 th grade, in the U.S. offered hybrid or full-time, in-person learning in Spring 2021, according to a federal survey . Most of these schools, as well as others, are likely to be in-person in fall 2021. While many states allow for in-person learning decision to be made at the local level, nine states have mandated schools return to in-person learning for the 2021-22 school year as of June 2021. No states are requiring the COVID-19 vaccine for school attendance at this time, and some states have enacted legislation to ban vaccine mandates for school attendance. However, due to concerns over the Delta variant and rising cases, some local districts are beginning to require the COVID-19 vaccine for teachers and staff. There have been legal challenges to vaccine mandates, with a federal District Court in Texas recently upholding a Hospital’s mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy for employees. The CDC recently updated their guidance for COVID-19 in schools, recommending masks for all staff and students regardless of vaccination status for in-person learning in the fall. While some states and school districts will require students and staff to wear masks at school, at least nine states have passed legislation to ban mask mandates for schools as of late July 2021. Recent KFF polling shows that about half the public overall supports K-12 schools requiring COVID-19 vaccination, but most parents are opposed, with divisions along partisan lines.

While returning to in-person learning can support children’s development and well-being, the transition back to school in the fall may be challenging for some children. Experts notes that in-person learning is beneficial for children’s social, emotional, and physical health and can provide access to important health services and address racial and social inequities. However, this school year will look different for many children due to COVID-19 prevention strategies and transitioning back to “the new normal” may be difficult for some, especially those who have adapted to new routines and virtual learning in the past year . Children’s mental health has worsened during the pandemic , which could make the transition back to school more challenging. Additionally, young children who have been home with parents during the pandemic may experience separation anxiety as they transition back to school or day care.

Schools and proposed policies may provide additional supports for children and families as they transition back to school. The increased Child Tax Credits began July 15 th and will continue monthly, but the enhanced CTC was only adopted for 2021. The American Families Plan put forth by the White House proposes to extend the CTC expansion through 2025 and make the credit permanently available to families with no earnings. The American Families Plan also proposes expanding school meals and access to healthy foods, making the summer EBT program permanent, and expanding SNAP eligibility for formerly incarcerated individuals. The American Families Plan also proposes a national paid family and medical leave program and universal pre-kindergarten, both of which research has shown have benefits for children’s health outcomes. 8 , 9 President Biden and congressional Democrats also recently released a reconciliation budget resolution that includes expanded child tax credits and investments in universal pre-k, child care, paid leave, and education. Other policy actions at the local level can also address children’s well-being. For example, schools and school districts can support students as they transition back to school by creating a safe in-person learning environment , providing staff and resources to support students having difficulty transitioning, ensuring staff and teachers have access to mental health resources, and developing a trauma-informed plan to respond to COVID-19 related trauma.

COVID-19 and the health care disruptions, mental health challenges, and economic hardships stemming from COVID-19 all have implications for children’s health and their transition back to school in the fall. While returning to in-person learning can support children’s development and well-being, uncertainty remains around what in-person learning will look like as cases rise due to the Delta variant and the transition to “the new normal” may be difficult for some children and their families. Recent policy developments attempt to address the ongoing effects of the pandemic on children, and schools, parents, and policymakers may face additional pressure to support children during this time.

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Coronavirus

news release

- Children Head Back to School Amid an Ongoing Pandemic That Has Had Significant Effects on Their Health and Well-Being

Also of Interest

- Mental Health and Substance Use Considerations Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The Next Stage of COVID-19 Vaccine Roll-Out in United States: Children Under 12

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Parents and the Pandemic

Going Back to School During COVID: 5 Students Share Their First Day

By Brittney McNamara

As schools reopen amid the COVID-19 pandemic, students are facing challenges they've never imagined. Teen Vogue' s Fear and Learning in America series is exploring what back to school means for students this year, and what they think about learning during the coronavirus crisis.

The first day of school is usually one filled with familiar faces, welcome-back hugs, and healthy doses of either ambition or apathy. But this year, going back to school is fraught. With the coronavirus pandemic persisting, many students are finding their first day isn't exactly what they'd imagined.

Teen Vogue asked five students to chronicle their first day in a diary entry. Two students went back to school in person, while the others attended via Zoom. Either way, the first day carried some of the typical excitement, but mostly it was a strange experience.

Anusha Gupta, 17, Michigan

August 24, 2020

I got up with the sun and birds. “Senior year, here I come,” I thought to myself. I got ready, grabbed a quick breakfast, and headed out the door. I was on my way to my first class of the day when I heard the bell. Students rushed past me to get to class but I seemed to be stuck in place. No matter how hard I tried, I just couldn’t — or wouldn’t — take another step. The bell rang louder and louder until I just couldn’t take it anymore. My eyes snapped wide open. Turns out that bell was actually my alarm clock, and I was still in bed, not school. My dream had only really gotten one thing right: It was indeed my last first day of school.

Never did I think that I wouldn’t even have to leave my house to kick off my senior year, but here we are! It was weird, to say the least. I half expected to wake up from yet another dream where everything could go back to how it used to be, but I soon found myself in front of my computer logging into class. Usually, my first day isn’t my teachers’ first day too, but that’s kind of the beauty of it all. In the wise words of Troy Bolton , we’re all in this together: Together through the technical difficulties, awkward silences, and Zoom fatigue (which is very real, by the way). Normally, I would see all the people I had missed over the summer and get to hug them and say hi. Instead, I found myself private chatting them on Zoom , “I like your haircut!,” “How’ve you been?” “I can’t believe everything that's happened since we last saw each other.” My friends and I would have eaten lunch together in the courtyard. Instead, we FaceTimed while all our computers charged.

I never realized how draining remote learning would be. Sitting at a computer all day feels more tiring than actually going to school. I wake up exhausted, despite eight hours of sleep. I get headaches every couple of days from all the screen time. My eating schedule is beyond irregular. But I also get to sleep in two more hours than usual. I can sit outside during class. I can grab a snack whenever I want. I can turn off my camera if I’m not feeling it. Everything is different, and we have to embrace the good and bad that comes along with it.

Despite all the challenges and mixed emotions, I actually feel really lucky. I’m able to learn without having to risk my family’s health and safety. My home is a place I love, and there is always food in the pantry. I’m old enough to handle my own schoolwork. My school provides technology for every student. My teachers are the most caring, passionate, and enthusiastic, with Bitmoji classrooms instead of real ones and breaks from our computers instead of walks around the school. It hurts me to think about the students who aren’t as lucky, students who don’t have access to the internet, who rely on school for their meals, whose parents need school for childcare. As we navigate this new world of learning, I hope we’ll be able to recognize the shortcomings of our current education system. I can’t wait to participate in the fight. Until then, I’ll be waking up tomorrow, ready for my second day of senior year.

Hannah Darcey, 17, Louisiana

August 20, 2020

The first day of my senior year. The day I had been looking forward to for the last four years. Usually, it is a day of anticipation, excitement and enthusiasm because of the many traditions, experiences and friendships that come with being a senior. But due to the pandemic, the last first day was nothing like anything I imagined at all.

We usually have an assembly, similar to a pep rally, in which all the grades gather together in the gym. Our big senior tradition at this assembly is getting our senior sweaters. The seniors anxiously sit in the bleachers, clutching their sweaters, waiting for the principal to say “seniors present yourselves.” The whole class erupts into hugging, cheering, and overall joy knowing that they have finally earned their spot as the next leaders of the school. They proudly represent the tan brown sweaters against the dark brown sweaters worn by the underclassmen. This bond of sisterhood and connection you feel with the other girls in your class is indescribable, and it is a moment you cherish. As underclassmen, you watch the next year's seniors have their special moment year after year until finally, it's your turn. And this year, it was finally our turn.

I was very excited to be going back to school, but also a little nervous. I was eager to be back in the place I called my second home, to be able to see my friends and teachers, and to walk the familiar halls that I had missed so much these past few months. I was looking forward to going back to a somewhat normal school day with a regular schedule again. But I was also a little hesitant to be going back, because I didn’t really know how school was going to work during this crazy time. However, I quickly learned that the faculty and staff put many procedures in place and were doing everything they could to keep us safe.

When walking into the school, we were greeted by both familiar and new faculty members at new temperature check stations staggered at the entrances. Walking back on campus felt just as it always had, with the addition of every student and faculty member required to wear a mask with our usual uniform. It possessed the same welcoming atmosphere of love and joy and excitement. But instead of gathering as an entire school for assembly, all five grades went to homeroom and walked into a class full of desks separated as far as they could from one another. Usually our classrooms are set up in “pods” — desks of three or four, in a circle facing each other — in order to better engage with classmates. It was definitely a strange look to our usually close-knit desks.

We watched our usual assembly from our classrooms thanks to a livestream that allowed us to still engage with what our administration needed to tell us in real time. We heard many speeches and reminders about the school year, but one important theme was that as long as we all do our part to keep each other safe, we will all be okay. I pray that everyone remains healthy, but with all the uncertainty it’s hard to tell. The administration reminded us we were all in this together and, although this is a new challenge, we were going to come out of it stronger.

Another safety precaution implemented were one-way hallways. Walking through the school using specific pathways is something everyone is trying to get used to, but we are slowly getting the hang of it. When it came time to present ourselves with our sweaters, we did it a little different than usual. We were called from our homerooms to the parking lot in which we all spread out 6 feet apart. Although we were not able to hug each other like usual, we were still able to stand with our classmates and present ourselves in front of the rest of the school watching over the live stream. We were very lucky to know that although getting our sweaters looked a little different, our administration made sure we were still able to have that special moment we had been waiting for. After receiving our sweaters, we were able to do our senior class cheer for the first time, another very special tradition. Overall, it was a really great first day full of new experiences and challenges that we were prepared to face.

Even though this first day back did not look at all what I had been dreaming of, it was still a special and unique and a memory that I will cherish forever. I don’t know what the future with look like for the rest of the school year, especially for memorable events like prom and graduation. But by that point in time, I just hope we are able to attend them in person without fear of the pandemic.

Taylor Pittman, 17, Louisiana

August 7th, 2020