- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Tress Academic

#80: Do I have to include my supervisor as a co-author?

February 9, 2021 by Tress Academic

The co-authorship of supervisors on papers of their PhD students is a hot topic in academia. Should they be included or not? All sorts of rules, conventions, and rumours seem to exist. Let’s clarify a few of them here!

1. Why worry about co-authorship of supervisors?

Oh dear, when we started to look into the question of whether PhD supervisors should be included as co-authors on a paper, we had no idea what kind of discussion we’d end up in. Of course, we always had our own opinion on it, but let us explain the situation: The question regarding whether PhD students should or must include their supervisors as co-authors/main author on the paper is a question that we get asked in almost every other course. Last time this question came up was only last week in one of our writing courses. So it must be a question of great interest to early-career researchers and PhD students! But it must also be a question that displays a lot of insecurity and perplexity.

The answer to this question seems to be so easy because there are clear rules about what makes somebody an author on a paper and what does not. Ethical bodies dealing with publication ethics, like the COPE, CSE or ICMJE (see below) provide great guidance about authorship, and most journal publishers have adopted their suggestions. So it should be clear who is expected to be credited as an author and who is not. But having discussed it so many times in courses with students, we know a simple YES or a NO on the question above is not enough. So, we’re not providing a simple answer here either.

2. The case of Rebecca and her supervisor

Rebecca is a 3rd year student in a biology programme and she told us her story: She is doing exciting research in a field that she loves. She’s highly motivated and brings a lot of energy and effort to her PhD work. The regulations of her university, where she will hopefully get awarded a PhD soon, require that she has to write and publish three papers in international peer-reviewed journals. Rebecca’s research is going fine, she is progressing well, and is just about one and a half months behind her original schedule for her PhD. She’s in a good mood and optimistic to bring the research work to an end, to get the papers published, and complete the degree. But she still has one big problem: She has no idea if she should include her supervisor as co-author on the paper.

She spoke to many fellow PhD students and Postdocs and asked for their advice. The stories she heard were so diverse that she still has no idea how to do it right. Some suggested the supervisor has to be on every paper, while others said they wrote their papers totally without them, got no input and, consequently, did not include them as co-author. Another suggestion was to include the supervisor as the main author, even if they contributed very little because it might be helpful to have a “big name” as a first author on the paper. A former PhD student told Rebecca that in his lab, it was a “must” to include the supervisor as the last author on all the papers, regardless of whether they were written by Master students, PhD students or Postdocs. One friend directed Rebecca to another friend who did a PhD and included the supervisor on all his papers because he was afraid that if he didn’t do it, it would affect the successful completion of his doctorate.

3. Is Rebecca a solitary case?

No! We spoke to many people like Rebecca and it was surprising how diverse the advice was that students like her had received. But as diverse as the single stories are, they have one common thread: Co-authorship of supervisors on the papers of their PhD students seems to be dominated by confusion, fears, and a lack of communication.

You can browse the web and you will find many references and cases that deal with all sorts of problems, opinions, conventions, and misconduct in the PhD student-supervisor relationship with regard to co-authorship on publications (see e.g. Find a PhD 2014 , Thompson 2017, Academia Stackexchange 2018 ). Cases are even reported where supervisors either neglect to co-author with their students, or where they publish work from their PhD students without even considering the student as co-author (e.g. COPE 2010 , Hayter & Watson 2017 ). So, it is definitely a tense field in which we’re operating when trying to answer this question.

4. Who is an author on a paper?

Luckily, you can find clear instructions in publication ethics guidelines. According to them, an author on a paper is somebody who has contributed to the research, written parts of the paper, reviewed successive manuscript versions, and taken part in the revision process. Sole provision of research funding or carrying out routine based activities that are linked to the research presented in a paper does not qualify for authorship ( COPE 2000 , CSE 2012 , ICMJE 2019 ).

So let’s go back to our question: Do you have to include your supervisor as co-author on your papers? The answer is YES and NO!

5. No! Supervisors should not be included as co-authors!

There is no rule that says PhD supervisors have to be a co-author on a paper of their PhD students. So, you don’t have to include your supervisor due to one of the cases described below:

- Just because they happen to be your supervisor.

- They are in a hierarchically higher academic position than you.

- They are well-known and respected in the field.

- You think you have to be grateful and pay back your supervisor.

- You’ve been told that it is always done like that in your field.

- You’ll feel guilty if you don’t include them as co-author.

- You fear a negative impact on your PhD if you don’t do it.

- You have applied for a PhD position at your supervisor’s lab/institute and think you’re obliged to include them.

- They provide funding for your project.

6. YES! Supervisors should be included as co-authors!

We do not suggest that your supervisors have to be excluded in all circumstances from your paper. No! There are very valid and compelling reasons that make your supervisor a co-author on your paper, e.g. if …

- they contributed to your work

- they contributed to your writing

- they were advising you on the steps of the writing process

- if they provided substantial intellectual support for the work you publish

- if they provided substantial input to help you with the revision of the paper

In the cases reported above, your supervisor is a natural co-author, and withdrawing their right to become a co-author would be a violation of publishing ethics.

7. How to avoid a co-authorship dispute

Rebecca’s problem in the case reported above is obvious: She was never involved in any discussion with her supervisor about co-authorship on any of the three papers she has to do. She kept silent, and the supervisor didn’t initiate a talk about it. Both are operating on the assumption that things will work out in their interest.

Another question deals with how far supervisors involve themselves in the research of their PhD students, and how much support they offer, but this is a different question which we’re not going to discuss at this time. Regardless of whether the supervisor has contributed a lot or only very little, it would have been wise for both PhD student and supervisor to sit together and get the co-authorship question out of the way.

For Rebecca, it would have been helpful to get familiar with the rules that apply to her institute or faculty. She could speak to somebody at the university who can advise her independently.

A good way to avoid the hassle and frustration from unsettled authorship-disputes would be to take the PhD student-supervisor relationship seriously, and let both sides do what they’re supposed to do: The supervisor is providing a supportive framework and involves themself in the student’s work only insofar as they allow the student to grow and reach their goal. Get your supervisor involved in your work, and then co-authorship will never be questioned.This would be mutually beneficial, and would provide benefits to both parties.

We hope that this article has helped you get a clearer idea of YOUR answer regarding the question of whether to include YOUR supervisor on your papers or not. Make a good decision, and then move on with your good work!

Relevant resources:

- Academia Stackexchange 2018. Telling PhD supervisor I published a paper about my thesis without telling them or listing them as authors?

- COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics), 2000. The COPE Report 1999. Guidelines on good publication practice. Family Practice 17, 218-221.

- COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) 2010: Supervisor published PhD students work.

- CSE (Scott-Lichter, D., the Editorial Policy Committee, Council of Science Editors) 2012. CSE’s White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2012 Update. 3rd Revised Edition. Wheat Ridge, CO.

- Find a PhD, 2014. Co-authorship with the supervisor.

- Haytor, M., Watson, R. 2017. Supervisors are morally obliged to publish with their PhD students.

- ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors), 2019. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: Writing and editing for biomedical publication. Updated version April 2019.

- Thompson, P. 2017: Co–writing with your supervisor – the authorship question .

More information:

Do you want to successfully write and publish a journal paper? If so, please sign up to receive our free guides.

© 2021 Tress Academic

#authorship, #WritingPapers, #PaperWriting, #publishing #journals, #supervision, #coauthor #PhD

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for choosing a PhD supervisor

Contributed equally to this work with: Loay Jabre, Catherine Bannon, J. Scott P. McCain, Yana Eglit

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Loay Jabre,

- Catherine Bannon,

- J. Scott P. McCain,

Published: September 30, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009330

- Reader Comments

Citation: Jabre L, Bannon C, McCain JSP, Eglit Y (2021) Ten simple rules for choosing a PhD supervisor. PLoS Comput Biol 17(9): e1009330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009330

Editor: Scott Markel, Dassault Systemes BIOVIA, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2021 Jabre et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The PhD beckons. You thought long and hard about why you want to do it, you understand the sacrifices and commitments it entails, and you have decided that it is the right thing for you. Congratulations! Undertaking a doctoral degree can be an extremely rewarding experience, greatly enhancing your personal, intellectual, and professional development. If you are still on the fence about whether or not you want to pursue a PhD, see [ 1 , 2 ] and others to help you decide.

As a PhD student in the making, you will have many important decisions to consider. Several of them will depend on your chosen discipline and research topic, the institution you want to attend, and even the country where you will undertake your degree. However, one of the earliest and most critical decisions you will need to make transcends most other decisions: choosing your PhD thesis supervisor. Your PhD supervisor will strongly influence the success and quality of your degree as well as your general well-being throughout the program. It is therefore vital to choose the right supervisor for you. A wrong choice or poor fit can be disastrous on both a personal and professional levels—something you obviously want to avoid. Unfortunately, however, most PhD students go through the process of choosing a supervisor only once and thus do not get the opportunity to learn from previous experiences. Additionally, many prospective PhD students do not have access to resources and proper guidance to rely on when making important academic decisions such as those involved in choosing a PhD supervisor.

In this short guide, we—a group of PhD students with varied backgrounds, research disciplines, and academic journeys—share our collective experiences with choosing our own PhD supervisors. We provide tips and advice to help prospective students in various disciplines, including computational biology, in their quest to find a suitable PhD supervisor. Despite procedural differences across countries, institutions, and programs, the following rules and discussions should remain helpful for guiding one’s approach to selecting their future PhD supervisor. These guidelines mostly address how to evaluate a potential PhD supervisor and do not include details on how you might find a supervisor. In brief, you can find a supervisor anywhere: seminars, a class you were taught, internet search of interesting research topics, departmental pages, etc. After reading about a group’s research and convincing yourself it seems interesting, get in touch! Make sure to craft an e-mail carefully, demonstrating you have thought about their research and what you might do in their group. After finding one or several supervisors of interest, we hope that the rules bellow will help you choose the right supervisor for you.

Rule 1: Align research interests

You need to make sure that a prospective supervisor studies, or at the very least, has an interest in what you want to study. A good starting point would be to browse their personal and research group websites (though those are often outdated), their publication profile, and their students’ theses, if possible. Keep in mind that the publication process can be slow, so recent publications may not necessarily reflect current research in that group. Pay special attention to publications where the supervisor is senior author—in life sciences, their name would typically be last. This would help you construct a mental map of where the group interests are going, in addition to where they have been.

Be proactive about pursuing your research interests, but also flexible: Your dream research topic might not currently be conducted in a particular group, but perhaps the supervisor is open to exploring new ideas and research avenues with you. Check that the group or institution of interest has the facilities and resources appropriate for your research, and/or be prepared to establish collaborations to access those resources elsewhere. Make sure you like not only the research topic, but also the “grunt work” it requires, as a topic you find interesting may not be suitable for you in terms of day-to-day work. You can look at the “Methods” sections of published papers to get a sense for what this is like—for example, if you do not like resolving cryptic error messages, programming is probably not for you, and you might want to consider a wet lab–based project. Lastly, any research can be made interesting, and interests change. Perhaps your favorite topic today is difficult to work with now, and you might cut your teeth on a different project.

Rule 2: Seek trusted sources

Discussing your plans with experienced and trustworthy people is a great way to learn more about the reputation of potential supervisors, their research group dynamics, and exciting projects in your field of interest. Your current supervisor, if you have one, could be aware of position openings that are compatible with your interests and time frame and is likely to know talented supervisors with good reputations in their fields. Professors you admire, reliable student advisors, and colleagues might also know your prospective supervisor on various professional or personal levels and could have additional insight about working with them. Listen carefully to what these trusted sources have to say, as they can provide a wealth of insider information (e.g., personality, reputation, interpersonal relationships, and supervisory styles) that might not be readily accessible to you.

Rule 3: Expectations, expectations, expectations

A considerable portion of PhD students feel that their program does not meet original expectations [ 3 ]. To avoid being part of this group, we stress the importance of aligning your expectations with the supervisor’s expectations before joining a research group or PhD program. Also, remember that one person’s dream supervisor can be another’s worst nightmare and vice versa—it is about a good fit for you. Identifying what a “good fit” looks like requires a serious self-appraisal of your goals (see Rule 1 ), working style (see Rule 5 ), and what you expect in a mentor (see Rule 4 ). One way to conduct this self-appraisal is to work in a research lab to get experiences similar to a PhD student (if this is possible).

Money!—Many people have been conditioned to avoid the subject of finances at all costs, but setting financial expectations early is crucial for maintaining your well-being inside and outside the lab. Inside the lab, funding will provide chemicals and equipment required for you to do cool research. It is also important to know if there will be sufficient funding for your potential projects to be completed. Outside the lab, you deserve to get paid a reasonable, livable stipend. What is the minimum required take-home stipend, or does that even exist at the institution you are interested in? Are there hard cutoffs for funding once your time runs out, or does the institution have support for students who take longer than anticipated? If the supervisor supplies the funding, do they end up cutting off students when funds run low, or do they have contingency plans? ( Fig 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009330.g001

Professional development opportunities—A key aspect of graduate school training is professional development. In some research groups, it is normal for PhD students to mentor undergraduate students or take a semester to work in industry to get more diverse experiences. Other research groups have clear links with government entities, which is helpful for going into policy or government-based research. These opportunities (and others) are critical for your career and next steps. What are the career development opportunities and expectations of a potential supervisor? Is a potential supervisor happy to send students to workshops to learn new skills? Are they supportive of public outreach activities? If you are looking at joining a newer group, these sorts of questions will have to be part of the larger set of conversations about expectations. Ask: “What sort of professional development opportunities are there at the institution?”

Publications—Some PhD programs have minimum requirements for finishing a thesis (i.e., you must publish a certain number of papers prior to defending), while other programs leave it up to the student and supervisor to decide on this. A simple and important topic to discuss is: How many publications are expected from your PhD and when will you publish them? If you are keen to publish in high-impact journals, does your prospective supervisor share that aim? (Although question why you are so keen to do so, see the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment ( www.sfdora.org ) to learn about the pitfalls of journal impact factor.)

Rule 4: It takes two to tango

Sooner or later, you will get to meet and interview with a prospective PhD supervisor. This should go both ways: Interview them just as much as they are interviewing you. Prepare questions and pay close attention to how they respond. For example, ask them about their “lab culture,” research interests (especially for the future/long term), and what they are looking for in a graduate student. Do you feel like you need to “put on an act” to go along with the supervisor (beyond just the standard interview mode)? Represent yourself, and not the person you think they are looking for. All of us will have some interviews go badly. Remember that discovering a poor fit during the interview has way fewer consequences than the incompatibility that could arise once you have committed to a position.

To come up with good questions for the prospective supervisor, first ask yourself questions. What are you looking for in a mentor? People differ in their optimal levels of supervision, and there is nothing wrong with wanting more or less than your peers. How much career guidance do you expect and does the potential supervisor respect your interests, particularly if your long-term goals do not include academia? What kind of student might not thrive in this research group?

Treat the PhD position like a partnership: What do you seek to get out of it? Keep in mind that a large portion of research is conducted by PhD students [ 4 ], so you are also an asset. Your supervisor will provide guidance, but the PhD is your work. Make sure you and your mentor are on the same page before committing to what is fundamentally a professional contract akin to an apprenticeship (see “ Rule 3 ”).

Rule 5: Workstyle compatibility

Sharing interests with a supervisor does not necessarily guarantee you would work well together, and just because you enjoyed a course by a certain professor does not mean they are the right PhD supervisor for you. Make sure your expectations for work and work–life approaches are compatible. Do you thrive on structure, or do you need freedom to proceed at your own pace? Do they expect you to be in the lab from 6:00 AM to midnight on a regular basis (red flag!)? Are they comfortable with you working from home when you can? Are they around the lab enough for it to work for you? Are they supportive of alternative work hours if you have other obligations (e.g., childcare, other employment, extracurriculars)? How is the group itself organized? Is there a lab manager or are the logistics shared (fairly?) between the group members? Discuss this before you commit!

Two key attributes of a research group are the supervisor’s career stage and number of people in the group. A supervisor in a later career stage may have more established research connections and protocols. An earlier career stage supervisor comes with more opportunities to shape the research direction of the lab, but less access to academic political power and less certainty in what their supervision style will be (even to themselves). Joining new research groups provides a great opportunity to learn how to build a lab if you are considering that career path but may take away time and energy from your thesis project. Similarly, be aware of pros and cons of different lab sizes. While big labs provide more opportunity for collaborations and learning from fellow lab members, their supervisors generally have less time available for each trainee. Smaller labs tend to have better access to the supervisor but may be more isolating [ 5 , 6 ]. Also note that large research groups tend to be better for developing extant research topics further, while small groups can conduct more disruptive research [ 7 ].

Rule 6: Be sure to meet current students

Meeting with current students is one of the most important steps prior to joining a lab. Current students will give you the most direct and complete sense of what working with a certain supervisor is actually like. They can also give you a valuable sense of departmental culture and nonacademic life. You could also ask to meet with other students in the department to get a broader sense of the latter. However, if current students are not happy with their current supervisor, they are unlikely to tell you directly. Try to ask specific questions: “How often do you meet with your supervisor?”, “What are the typical turnaround times for a paper draft?”, “How would you describe the lab culture?”, “How does your supervisor react to mistakes or unexpected results?”, “How does your supervisor react to interruptions to research from, e.g., personal life?”, and yes, even “What would you say is the biggest weakness of your supervisor?”

Rule 7: But also try to meet past students

While not always possible, meeting with past students can be very informative. Past students give you information on career outcomes (i.e., what are they doing now?) and can provide insight into what the lab was like when they were in it. Previous students will provide a unique perspective because they have gone through the entire process, from start to finish—and, in some cases, no longer feel obligated to speak well of their now former supervisor. It can also be helpful to look at previous students’ experiences by reading the acknowledgement section in their theses.

Rule 8: Consider the entire experience

Your PhD supervisor is only one—albeit large—piece of your PhD puzzle. It is therefore essential to consider your PhD experience as whole when deciding on a supervisor. One important aspect to contemplate is your mental health. Graduate students have disproportionately higher rates of depression and anxiety compared to the general population [ 8 ], so your mental health will be tested greatly throughout your PhD experience. We suggest taking the time to reflect on what factors would enable you to do your best work while maintaining a healthy work–life balance. Does your happiness depend on surfing regularly? Check out coastal areas. Do you despise being cold? Consider being closer to the equator. Do you have a deep-rooted phobia of koalas? Maybe avoid Australia. Consider these potentially even more important questions like: Do you want to be close to your friends and family? Will there be adequate childcare support? Are you comfortable with studying abroad? How does the potential university treat international or underrepresented students? When thinking about your next steps, keep in mind that although obtaining your PhD will come with many challenges, you will be at your most productive when you are well rested, financially stable, nourished, and enjoying your experience.

Rule 9: Trust your gut

You have made it to our most “hand-wavy” rule! As academics, we understand the desire for quantifiable data and some sort of statistic to make logical decisions. If this is more your style, consider every interaction with a prospective supervisor, from the first e-mail onwards, as a piece of data.

However, there is considerable value in trusting gut instincts. One way to trust your gut is to listen to your internal dialogue while making your decision on a PhD supervisor. For example, if your internal dialogue includes such phrases as “it will be different for me,” “I’ll just put my head down and work hard,” or “maybe their students were exaggerating,” you might want to proceed with caution. If you are saying “Wow! How are they so kind and intelligent?” or “I cannot wait to start!”, then you might have found a winner ( Fig 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009330.g002

Rule 10: Wash, rinse, repeat

The last piece of advice we give you is to do this lengthy process all over again. Comparing your options is a key step during the search for a PhD supervisor. By screening multiple different groups, you ultimately learn more about what red flags to look for, compatible work styles, your personal expectations, and group atmospheres. Repeat this entire process with another supervisor, another university, or even another country. We suggest you reject the notion that you would be “wasting someone’s time.” You deserve to take your time and inform yourself to choose a PhD supervisor wisely. The time and energy invested in a “failed” supervisor search would still be far less than what is consumed by a bad PhD experience ( Fig 3 ).

The more supervisors your interview and the more advice you get from peers, the more apparent these red flags will become.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009330.g003

Conclusions

Pursuing a PhD can be an extremely rewarding endeavor and a time of immense personal growth. The relationship you have with your PhD supervisor can make or break an entire experience, so make this choice carefully. Above, we have outlined some key points to think about while making this decision. Clarifying your own expectations is a particularly important step, as conflicts can arise when there are expectation mismatches. In outlining these topics, we hope to share pieces of advice that sometimes require “insider” knowledge and experience.

After thoroughly evaluating your options, go ahead and tackle the PhD! In our own experiences, carefully choosing a supervisor has led to relationships that morph from mentor to mentee into a collaborative partnership where we can pose new questions and construct novel approaches to answer them. Science is hard enough by itself. If you choose your supervisor well and end up developing a positive relationship with them and their group, you will be better suited for sound and enjoyable science.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 5. Smith D. The big benefits of working in a small lab. University Affairs. 2013. Available from: https://www.universityaffairs.ca/career-advice/career-advice-article/the-big-benefits-of-working-in-a-small-lab/

Supervisor as coauthor in writing for publication: Evidence from a cohort of non-native English-speaking Master of Education students

- Original Paper

- Published: 20 January 2021

- Volume 1 , article number 44 , ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Weipeng Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8057-2863 1 ,

- Yongyan Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8130-7041 2 &

- Hui Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9355-1116 3

958 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Existing studies on writing for publication have focused on doctoral students and junior scholars, leaving those non-native English-speaking (NNES) Master’s students understudied. This article presents a case study of the challenges and coping strategies shared by the six purposively selected NNES Master’s students, who have each successfully published in an international academic journal with their supervisor. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with the students and their supervisor, and their research proposals, manuscripts and publications were collected and analysed. The results indicated that: (1) the topics co-constructed by the students and their supervisor laid a solid foundation for their success in journal publication; (2) all the case students demonstrated a long-term commitment to academia and proactively coped with numerous challenges during their writing-for-publication processes; and (3) ‘supervisor as coauthor’ was found to be a successful strategy, with co-revision at its core.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Writing in doctoral programs: examining supervisors’ perspectives

Ethical and Practical Considerations for Completing and Supervising a Prospective PhD by Publication

Mentoring Junior Scientists for Research Publication

Data availability.

The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

This Chinese saying originates in Difan [帝範], a collection of advice provided by the first emperor of the Tang Dynasty, Li Shimin (known as Tang Taizong) (598–649), to his children.

After receiving their Master’s degree, five of the six participants went on to pursue a doctoral degree (except Jia who was working in a kindergarten at the time when the interviews were conducted).

Anderson C, Day K, McLaughlin P (2006) Mastering the dissertation: lecturers’ representations of the purposes and processes of Master’s level dissertation supervision. Stud High Educ 31(2):149–168

Article Google Scholar

Anderson C, Day K, McLaughlin P (2008) Student perspectives on the dissertation process in a masters degree concerned with professional practice. Stud ContinuEduca 30(1):33–49

Belcher D (1994) The apprenticeship approach to advanced academic literacy: Graduate students and their mentors. EnglSpecifPurp 13(1):23–34

Google Scholar

Casanave CP (2019) Performing expertise in doctoral dissertations: thoughts on a fundamental dilemma facing doctoral students and their supervisors. J Second Lang Writ 43:57–62

Creswell JW (2014) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Cuthbert D, Spark C, Burke E (2009) Disciplining writing: the case for multi-disciplinary writing groups to support writing for publication by higher degree by research candidates in the humanities, arts and social sciences. High Educ Res Dev 28(2):137–149

Dowd JE, Connolly MP, Thompson RJ Jr, Reynolds JA (2015) Improved reasoning in undergraduate writing through structured workshops. J Econ Educ 46(1):14–27

Drennan J, Clarke M (2009) Coursework master’s programmes: the student’s experience of research and research supervision. Stud High Educ 34(5):483–500

Flowerdew J (1999) Problems in writing for scholarly publication in English: the case of Hong Kong. J Second Lang Writ 8(3):243–264

Florence MK, Yore LD (2004) Learning to write like a scientist: coauthoring as an enculturation task. J Res Sci Teach 41(6):637–668

Greaney AM, Sheehy A, Heffernan C, Murphy J, Mhaolrúnaigh SN, Heffernan E, Brown G (2012) Research ethics application: a guide for the novice researcher. Br J Nurs 21(1):38–43

Ho MC (2017) Navigating scholarly writing and international publishing: individual agency of Taiwanese EAL doctoral students. J EnglAcadPurp 27:1–13

Huang JC (2010) Publishing and learning writing for publication in English: perspectives of NNES PhD students in science. J EnglAcadPurp 9(1):33–44

Hyland K (2012) Welcome to the machine: thoughts on writing for scholarly publication. J Second Lang Teach Res 1(1):58–68

Kamler B (2008) Rethinking doctoral publication practices: writing from and beyond the thesis. Stud High Educ 33(3):283–294

Kramer B, Libhaber E (2016) Writing for publication: institutional support provides an enabling environment. BMC Med Educ 16(1):115

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Lee A, Boud D (2003) Writing groups, change and academic identity: research development as local practice. Stud High Educ 28(2):187–200

Lee A, Kamler B (2008) Bringing pedagogy to doctoral publishing. Teach High Educ 13(5):511–523

Lei J, Hu G (2015) Apprenticeship in scholarly publishing: a student perspective on doctoral supervisors’ roles. Publications 3(1):27–42

Li Y (2006) A doctoral student of physics writing for publication: a sociopolitically-oriented case study. EnglSpecifPurp 25(4):456–478

Li Y (2016) Chinese postgraduate medical students researching for publication. Publications 4(3):25

Li Y, Li D, Yang W, Li H (2020) Negotiating the teaching-research nexus: a case of classroom teaching in an MEd program. N Zeal J Educ Stud 55(1):181–196

Luo N (2015) Two Chinese medical master’s students aspiring to publish internationally: a longitudinal study of legitimate peripheral participation in their communities of practice. Publications 3(2):89–103

Martín P, Rey-Rocha J, Burgess S, Moreno AI (2014) Publishing research in English-language journals: attitudes, strategies and difficulties of multilingual scholars of medicine. J EnglAcadPurp 16:57–67

Martinez R, Graf K (2016) Thesis supervisors as literacy brokers in Brazil. Publications 4(3):26

McGrail MR, Rickard CM, Jones R (2006) Publish or perish: a systematic review of interventions to increase academic publication rates. High Educ Res Dev 25(1):19–35

Page-Adams D, Cheng LC, Gogineni A, Shen CY (1995) Establishing a group to encourage writing for publication among doctoral students. J Soc Work Educ 31(3):402–407

Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Simpson S (2013) Systems of writing response: a Brazilian student’s experiences writing for publication in an environmental sciences doctoral program. Res Teach Engl 48(2):228–249

Thorpe A, Snell M, Davey-Evans S, Talman R (2017) Improving the academic performance of non-native English-speaking students: the contribution of pre-sessional English language programmes. High Educ Q 71(1):5–32

Wenger E (1998) Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Yang W, Li Y, Zhou W, Li H (2020) Learning to design research: students’ agency and experiences in a Master of Education program in Hong Kong. ECNU Rev Educ 3(2):291–309

Yin RK (2014) Case study research: design and methods, 5th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Download references

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the students who took part in the study, for their time and cooperation.

This work was supported by the General Research Fund (Research Grants Council) under Grant No. 17607517.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

S R Nathan School of Human Development, Singapore University of Social Sciences, Singapore, Singapore

Weipeng Yang

Faculty of Education, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Macquarie School of Education, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

WY carried out the research and drafted the manuscript. YL and HL provided important ideas for the research and helped to draft the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Weipeng Yang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interest.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yang, W., Li, Y. & Li, H. Supervisor as coauthor in writing for publication: Evidence from a cohort of non-native English-speaking Master of Education students. SN Soc Sci 1 , 44 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-020-00044-y

Download citation

Received : 20 July 2020

Accepted : 25 November 2020

Published : 20 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-020-00044-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Academic supervision

- Master of Education

- Non-native English-speaking students

- Supervisor as coauthor

- Writing for publication

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Enrichment Programs

Individualized & Interdisciplinary Studies Program

Guide for thesis supervisors.

Thank you for supervising an individualized major senior thesis project. Your expertise is critical in guiding the student’s project and setting the criteria for its evaluation. The guidelines below outline some considerations particular to individualized major students. They are most appropriate for traditional research projects but may also be relevant to less traditional final projects.

All individualized majors complete a capstone, which provides them an opportunity to integrate knowledge they have acquired during the course of their majors. About 40-45 percent of individualized majors do so by completing a thesis. (The rest complete our capstone course or an approved alternative.)

Thesis projects usually take the form of a traditional research study, but other formats, such as a photo essay, film, website, or piece of creative writing are also possible. Thesis projects, whatever their form, should contribute to the development of knowledge or practice in new ways, involve significant background research, and require sustained attention in the implementation of the project. If the final product takes a less traditional form, it should include a piece of writing that describes the student’s learning process.

Thesis Courses

Some thesis projects will comprise six credits completed over the course of two semesters. This is mandatory for students completing Honors Scholar requirements in their individualized major. Non-honors students may complete a one-semester, three-credit thesis project. Students intending to complete a thesis project must submit a thesis proposal which they have discussed with their thesis supervisor no later than the last day of classes of the semester before they begin their thesis.

In the social sciences and humanities : In the Fall semester of the senior year, students will typically begin their research by enrolling in a thesis-related research seminar, graduate course, or independent study in their thesis supervisor’s department. During the Spring semester, students will enroll in UNIV 4697W Senior Thesis (for which the thesis supervisor serves as instructor) in which they will complete the research and write the thesis. During this process, the student meets regularly with the thesis supervisor for feedback on data collection, evidence gathering, analysis, and writing.

In the sciences , students may follow a more extended sequence, perhaps two to three semesters of data collection and laboratory work (independent studies or research courses) followed by thesis writing (UNIV 4697W) in the final semester.

Learning Outcomes

Individual faculty will differ in expectations regarding research methodology, theoretical approaches, and presentation of findings. Nonetheless, there are some general criteria and intended learning outcomes for all individualized major thesis projects.

- The student’s research, analysis, and writing on the thesis project should be relevant to their individualized major and represent an opportunity for them to integrate and deepen at least several aspects of study in the major.

- A thesis should do more than summarize the existing literature on a particular topic. It should make an original contribution to the field of study, present new findings in the form of new data, or new, critical interpretations of existing material. It should reflect a good command of the research methodologies in the relevant discipline(s).

Upon completion of the thesis project the student should be able to:

- Define a research question and design a substantial research project.

- Select a methodological approach to address the research question.

- Identify appropriate sources and collect relevant and reliable data that addresses the research question.

- Analyze the strengths and limitations of different scholarly approaches to the question, and recognize the resulting interpretative conflicts.

- Develop an argument that is sustained by the available evidence

- Present that argument in a clear, well-organized manner.

Requirements for Honors Students

As noted above, all Honors students are expected to complete at least six credits of thesis-relevant coursework. In addition, all Honors students are expected to have a second reader and make a public presentation of their thesis project.

Second Reader

We ask Honors students to identify a second reader for their thesis from a relevant discipline, which may be the same as, or different from, the supervisor’s discipline. The second reader will provide the student with a different perspective and may provide additional insights on how to achieve the intended learning outcomes of the thesis. The thesis supervisor, in consultation with the student, determines when to bring the second reader on board. It is the supervisor’s prerogative to define how the grade for the thesis will be determined.

Public Presentation

Honors students are required to make a public presentation of their thesis research in a format negotiated with the thesis supervisor. Where possible, the audience should include the thesis supervisor, the second reader, and an IISP staff member. Other faculty members and the student’s peers may be invited to join the audience, as well.

Existing departmental exhibitions or “Frontiers in Undergraduate Research” make excellent venues for student presentations. If a student cannot find a venue for his or her presentation, please consult with IISP and we will coordinate one.

Note: Although non-Honors students who are completing a thesis are not required to have a second reader or make a public presentation, we would certainly welcome them to do so.

Honors Advising

An IISP staff member serves as Honors Advisor to each individualized major following an Honors Scholar plan of study. The staff member’s role as an Honors advisor is to coordinate and facilitate students’ plans for completing Honors Scholar requirements, including the thesis, and to monitor progress toward completion.

Thesis Course Registration

Specific instructions for registering for UNIV 4697W are available on the Capstone page .

We very much appreciate your willingness to supervise an individualized major’s senior thesis. If you have any questions about the Individualized Major Program or about supervising an individualized major thesis, please contact IISP staff .

Duties of a thesis supervisor and the supervision plan

The instruction belongs to the following themes.

- Supervising theses

Search for degree programme

Open university programmes.

- Open university Flag this item

Bachelor's Programmes

- Bachelor's Programme for Teachers of Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Agricultural Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Applied Psychology Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Art Studies Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Biology Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Chemistry Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Computer Science (TKT) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Cultural Studies Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Economics Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Class Teacher (KLU, in Swedish) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Class Teacher, Education (LO-KT) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Class Teacher, Educational Psychology (LO-KP) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Craft Teacher Education (KÄ) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Early Education Teacher (SBP) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Early Education Teacher (VO) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: General and Adult Education (PED, in Swedish) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: General and Adult Education (YL and AKT) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Home Economics Teacher (KO) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Education: Special Education (EP) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Environmental and Food Economics Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Environmental Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Food Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Forest Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Geography Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Geosciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in History Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Languages Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Law Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Logopedics Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Mathematical Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Molecular Biosciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Pharmacy Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Philosophy Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Physical Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Politics, Media and Communication Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Psychology Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Science (BSC) Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Social Research Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Social Sciences Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Society and Change Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in the Languages and Literatures of Finland Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Theology and Religious Studies Flag this item

- Bachelor's Programme in Veterinary Medicine Flag this item

Master's and Licentiate's Programmes

- Degree Programme in Dentistry Flag this item

- Degree Programme in Medicine Flag this item

- Degree Programme in Veterinary Medicine Flag this item

- International Masters in Economy, State & Society Flag this item

- Master ́s Programme in Development of health care services Flag this item

- Master's Programme for Teachers of Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Agricultural Sciences Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Agricultural, Environmental and Resource Economics Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Area and Cultural Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Art Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Atmospheric Sciences (ATM) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Changing Education Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Chemistry and Molecular Sciences Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Computer Science (CSM) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Contemporary Societies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Cultural Heritage Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Culture and Communication (in Swedish) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Data Science Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Economics Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Class Teacher (KLU, in Swedish) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Class Teacher, Education (LO-KT) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Class Teacher, Educational Psychology (LO-KP) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Craft Teacher Education (KÄ) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Early Education (VAKA) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: General and Adult Education (PED, in Swedish) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: General and Adult Education (YL and AKT) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Home Economics Teacher (KO) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Education: Special Education (EP) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in English Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Environmental Change and Global Sustainability Flag this item

- Master's Programme in European and Nordic Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Finnish and Finno-Ugrian Languages and Cultures Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Food Economy and Consumption Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Food Sciences Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Forest Sciences Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Gender Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Genetics and Molecular Biosciences Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Geography Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Geology and Geophysics Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Global Politics and Communication Flag this item

- Master's Programme in History Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Human Nutrition and Food-Related Behaviour Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Integrative Plant Sciences Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Intercultural Encounters Flag this item

- Master's Programme in International Business Law Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Languages Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Law Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Life Science Informatics (LSI) Flag this item

- Master's programme in Linguistic Diversity and Digital Humanities Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Literary Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Logopedics Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Materials Research (MATRES) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Mathematics and Statistics (MAST) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Neuroscience Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Particle Physics and Astrophysical Sciences (PARAS) Flag this item

- Master's programme in Pharmaceutical Research, Development and Safety Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Pharmacy Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Philosophy Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Politics, Media and Communication Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Psychology Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Russian, Eurasian and Eastern European Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Scandinavian Languages and Literature Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Social and Health Research and Management Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Social Research Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Social Sciences (in Swedish) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Society and Change Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Theology and Religious Studies Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Theoretical and Computational Methods (TCM) Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Translation and Interpreting Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Translational Medicine Flag this item

- Master's Programme in Urban Studies and Planning (USP) Flag this item

- Master’s Programme in Global Governance Law Flag this item

- Nordic Master Programme in Environmental Changes at Higher Latitudes (ENCHIL) Flag this item

Doctoral Programmes

- Doctoral Programme Brain and Mind Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Atmospheric Sciences (ATM-DP) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Biomedicine (DPBM) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Chemistry and Molecular Sciences (CHEMS) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Clinical Research (KLTO) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Clinical Veterinary Medicine (CVM) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Cognition, Learning, Instruction and Communication (CLIC) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Computer Science (DoCS) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Drug Research (DPDR) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Economics Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Food Chain and Health Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Gender, Culture and Society (SKY) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Geosciences (GeoDoc) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in History and Cultural Heritage Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Human Behaviour (DPHuB) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Integrative Life Science (ILS) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Interdisciplinary Environmental Sciences (DENVI) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Language Studies (HELSLANG) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Law Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Materials Research and Nanoscience (MATRENA) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Mathematics and Statistics (Domast) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Microbiology and Biotechnology Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Oral Sciences (FINDOS) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Particle Physics and Universe Sciences (PAPU) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Philosophy, Arts and Society Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Plant Sciences (DPPS) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Political, Societal and Regional Changes (PYAM) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Population Health (DOCPOP) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in School, Education, Society and Culture Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Social Sciences Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Sustainable Use of Renewable Natural Resources (AGFOREE) Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Theology and Religious Studies Flag this item

- Doctoral Programme in Wildlife Biology (LUOVA) Flag this item

Specialist training programmes

- Multidisciplinary studies for class teachers (teaching in Finnish) Flag this item

- Multidisciplinary studies for class teachers (teaching in Swedish) Flag this item

- Non-degree studies for special education teachers (ELO) Flag this item

- Non-degree studies for special education teachers (LEO) Flag this item

- Non-degree studies for special education teachers (VEO) Flag this item

- Non-degree studies in subject teacher education Flag this item

- Specific Training in General Medical Practice Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Clinical Mental Health Psychology Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Neuropsychology Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Environmental Health and Food Control (old) Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Equine Medicine (old) Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Food Production Hygiene Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Infectious Animal Diseases (new) Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Production Animal Medicine (old) Flag this item

- Specialisation Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Small Animal Medicine (old) Flag this item

- Specialisation Studies in Community and Hospital Pharmacy (for B.Sc.Pharm.) Flag this item

- Specialisation Studies in Community and Hospital Pharmacy (for M.Sc.Pharm.) Flag this item

- Specialisation Studies in Industrial Pharmacy (for B.Sc.Pharm.) Flag this item

- Specialisation Studies in Industrial Pharmacy (for M.Sc.Pharm.) Flag this item

- Specialist Training in Dentistry Flag this item

- Specialist Training in Hospital Chemistry Flag this item

- Specialist Training in Hospital Microbiology Flag this item

- Specialist Training in Medicine, 5-year training Flag this item

- Specialist Training in Medicine, 6-year training Flag this item

- Specialist's Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Environmental Health and Food Control Flag this item

- Specialist's Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Equine Medicine (new) Flag this item

- Specialist's Programme in Veterinary Medicine, general veterinary medicine Flag this item

- Specialist's Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Infectious Animal Diseases (new) Flag this item

- Specialist's Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Production Animal Medicine (new) Flag this item

- Specialist's Programme in Veterinary Medicine, Small Animal Medicine (new) Flag this item

- Trainer Training Programme in Integrative Psychotherapy Flag this item

- Training Programme for Psychotherapists Flag this item

- Language Centre

- Open University

Supervision work is closely linked to the intended learning outcomes of the degree and thesis as well as the related grading criteria. In accordance with the Regulations on Degrees and the Protection of Students’ Rights at the University of Helsinki, the student must receive instruction both during their studies and while writing their thesis. See here for instructions on ensuring that your supervision is aligned with the learning outcomes.

On this page

Supervision principles.

The Rector decides on the principles of supervision, including the rights and obligations of the student and the supervisor. The degree programme’s curriculum must contain instructions on how to prepare a personal study plan, along with the practices for approving and updating the plan. Please review the curriculum of your faculty and the thesis grading criteria in order to ensure that your supervision is aligned with the learning outcomes.

In the Rector’s decision, supervision refers to the support provided for the student’s or doctoral candidate’s learning process as they change, gain experience and grow as an expert. As a whole, supervision consists of communication, advice, instruction and special guidance. Supervision and counselling can be organised in a group led by the supervisor, at a seminar, in a peer group of students or doctoral candidates organised by the supervisor or in a personal meeting separately agreed between the supervisor and the student/doctoral candidate. Supervision and counselling can also be provided electronically through, for example, Moodle or other teaching tools available.

Members of the teaching and research staff provide counselling that is related to teaching and research and requires knowledge of the content of different studies and disciplines. This counselling may concern, for example, personal study plans or thesis supervision.

Guidance and counselling are provided in the Finnish and Swedish-language and multilingual degree programmes in Finnish or Swedish depending on the student’s native language or in English or another language as agreed with the student. If the student’s native language is a language other than Finnish or Swedish, guidance and counselling are provided in English or, if agreed with the student, in another language. In English-language master’s programmes and doctoral programmes, guidance can also be provided solely in English.

The degree programme steering group is responsible for ensuring that each student is appointed with a primary supervisor who is responsible for the supervision of their thesis. Additional supervisors may also be appointed. Your supervision plan can be used to agree on the responsibilities related to the supervision.

Supervision as interaction and the supervision plan

Supervision is about interaction with responsibilities that are divided between the different parties of the supervision relationship. Ambiguities related to supervision are often due to the parties’ different expectations regarding the content and responsibilities of the supervision and the fact that the parties are often unaware of the others’ expectations. Below, you can find a table that serves as a great tool for considering the different rights and obligations related to supervision

The policies and practices of supervision should be discussed in the early stages of the thesis process. The supervisor and the student may also prepare a written supervision plan that clarifies the schedule for the supervision and the thesis work as well as the content of the supervision. The plan can also be utilised if any problems arise or you fall behind schedule.

Topics the supervisor should incorporate in the supervision

When supervising a student’s thesis work, remember to pay attention to the following topics:

- the responsible conduct of research and avoiding cheating

- guiding the student in matters related to data protection

- matters related to open access publications and the public availability of theses

- inform the student of the general process of thesis examination and approval and the related schedule

Different faculties may have their own decisions and instructions on thesis supervision. Please read the instructions provided by your faculty.

See also the Instructions for Students

You will find related content for students in the Studies Service.

Bachelor’s theses and maturity tests

Thesis and maturity test in master's and licentiate's programmes.

- Instructions for students

- Notifications for students

School of Graduate Studies

Supervisor guidelines for the doctoral thesis, doctoral thesis.

The doctoral thesis is the culmination of advanced studies and rigorous research in a field of study. It is the pinnacle of the student’s doctoral program. Although the thesis is indisputably significant, it is also important to remember that the doctoral thesis is just one of many steps along the student’s career path and should therefore be well-defined and manageable.

At the University of Toronto, the term ‘thesis’ is generally used to refer to the culminating project for either a Master’s or a doctoral degree. At other institutions and in other countries, the term ‘dissertation’ is more commonly used at the doctoral level. This document uses the term ‘thesis’ to refer to a doctoral thesis, but supervisors or departments may prefer the term ‘dissertation’.

Doctoral thesis writers have often written a Master’s thesis (or a Major Research Paper) earlier in their careers. A doctoral thesis will have elements in common with those projects while also needing to offer a higher degree of originality and a broader scope.

The doctoral thesis has been historically written as a unified work, similar in form to a scholarly monograph; this traditional format remains the norm in some disciplines. In other disciplines, the traditional thesis has been replaced by a publication-based thesis in which a series of scholarly publications on the same research problem are combined into a coherent whole. Today, there is a growing acceptance of more flexible formats and structures that aim to enhance professional practice or that include creative scholarly artefacts such as film, audio, visual, and graphic representations. There is also growing recognition of the need to welcome Indigenous forms of knowledge building and dissemination. Regardless of format or structure, all doctoral theses must meet the fundamental requirements of demonstrating academic rigour and making a distinct contribution to the knowledge in the field.

The decision about the structure and format of the student’s doctoral thesis should be made by the supervisor and the supervisory committee members and be informed by the practices in the specific discipline and the student’s academic and professional goals. In some fields, the decision about structure and format is relatively easy to make while in others the decision requires careful consideration from all involved parties.

The following guidelines have been designed to help students, supervisors, and supervisory committee members by identifying the required academic criteria of the doctoral thesis and by describing the various available formats and structures. Supervising faculty members are encouraged to clearly communicate the required academic criteria and expected format of the doctoral thesis early in the student’s doctoral program to facilitate the student’s writing process.

Key Criteria of the Doctoral Thesis

Regardless of the format of the doctoral thesis, certain criteria must be met. For the thesis to be acceptable, the student must do the following:

- Demonstrate how the research makes an original contribution by advancing knowledge in the field

- Show a thorough familiarity with the field and an ability to critically analyze the relevant literature

- Display a mastery of research methods and their application

- Offer a complete and systematic account of their scholarly work

- Present the results and analysis of their original research

- Document sources and support claims

- Locate their work within the broader field or discipline

- Write in a style that respects the norms of academic and scholarly communication

Most doctoral writers understand that their thesis will need to meet these criteria without necessarily understanding how they will do so. A central element of writing a thesis is coming to understand how to write an extended text that meets these criteria. With guidance—from the supervisor, the supervisory committee, from peers, and from institutional writing support—these criteria will ultimately help the student to understand when they have met their thesis writing goals.

Formats of the Doctoral Thesis

Traditional thesis.

The traditional, or monograph-style, thesis format reflects the original conception of a thesis as a “book” presenting the candidate’s research project. The traditional format is organized as a single narrative describing the research problem, the context of the research, the methods used, the findings, and the conclusions. The organization of a traditional thesis is generally organic. If the thesis deals with experimental research, it may be structured with an introductory chapter, a literature review chapter, a method chapter, some number of findings chapters, and a discussion/ concluding chapter. If the thesis is based on non-experimental research, the form is likely to be determined by the exigencies of the particular topic. After doctoral studies are complete, a traditional thesis will often be revised into a scholarly monograph or a number of research articles, but the form in which it is presented for the final oral exam is not itself intended for publication. This style of thesis remains the norm in the Humanities and in many Social Science disciplines.

Publication-Based Thesis

The publication-based thesis (PBT), also referred to as the manuscript or article-based thesis, is a coherent work consisting of a number of scholarly publications focusing on the same research problem. The PBT, which takes many forms, generally includes an introductory section, the publishable manuscripts, and a cumulative discussion or conclusion chapter. To promote coherence, the introduction and cumulative concluding chapters clearly explain how these separate manuscripts fit together into a unified body of research. The opening and closing chapters—which act as bookends to the publishable articles—are integral to the purpose of these theses. In these sections, the writer will set out the broad contours of the problem and its significance, review the relevant literature and contextualizing material, and draw the ultimate conclusions about the implications of the whole research project. As the PBT is a relatively new type of thesis structure designed to meet different professional demands, its form is necessarily different in different contexts. For instance, in some fields, the articles may appear in the thesis in their precise published form; in others, the articles may need to be adapted to better serve the needs of the full thesis. The student and supervisor/supervisory committee will need to establish a clear understanding from the outset about the internal structuring of the PBT.

Although departmental requirements and norms may vary, below are some general guidelines that may be helpful for those writing PBT.

- The number of articles required for inclusion is usually three, although the number depends on the articles’ scope, scientific quality and significance, and publishing forum, as well as the author’s independent contribution to any co-authored articles included in the thesis.

- Publication of manuscripts, or acceptance for publication by a peer-reviewed journal, does not guarantee that the thesis will be found acceptable for the degree sought.

- Published-based theses may include published, in press or in review manuscripts or articles that have not yet been submitted for publication. Normally, the thesis and examination committees must deem the articles as publishable if the articles are not published at the time of defence.

- In some departments, the publication-based thesis includes each individual manuscript in a form that is identical to the published/submitted version, including the reference list. In other departments, students are permitted or required to adapt the articles into a form more suitable for inclusion in the thesis.

- Publication-based theses can include co-authored publications and, in such cases, a detailed statement on individual student contributions to each article must be clearly articulated. Students are strongly recommended (and, in some units, required) to have their contributions approved by the authors of the articles in question.

- No two student theses will be allowed to be identical.

- In the case of multiple-authored articles, the expectation is that the thesis writer will be the first or co-first author. In rare cases, a supervisor may decide that a paper can be included when the thesis writer is not a first author, provided that their contribution to the paper is substantial. In all cases, the parts of the PBT that are not written for publication (the Introduction, Discussion, Conclusions and Future Recommendations chapters) must be entirely the work of the thesis writer.

Multimodal Thesis

All doctoral theses must contain a written component; however, other elements may be included in addition to the written text. Some examples of other elements that may be included with the written text are films or videos, electronically interactive word/image-based texts, poems, novels or sections of a novel, play scripts, short stories, documentation of performances, or pieces of art. In multimodal theses, the creative element should be integrated into the theoretical context in order to show explicitly how the thesis, as a whole, leads to new insights and contributions. In all other respects, the thesis must conform to the same standards required for all doctoral theses. It should make an original contribution to knowledge, demonstrate appropriate research methods and training, and be worthy of publication in whole or in part.

Portfolio Thesis

The portfolio thesis is a form of thesis in which a certain amount of publishing will “equal” a thesis, without requiring a separate text to be written. This type of thesis is also known as a stapler thesis or a Ph.D. by publication, a name that highlights the absence of an actual thesis. This form of thesis is currently rare at the University of Toronto.

Professional Doctoral Thesis in Practice

At the University of Toronto, the professional doctoral thesis in practice includes the identification and investigation of a problem in practice, the application of theory, research and policy analysis to the problem of practice, translating research into practice, and a proposed plan for action to address the problem of practice. The professional doctoral thesis in practice is expected to have meaningful generative impact on practice and policy.

Ontario Council of Academic Vice-Presidents’ (OCAV) Doctoral Degree Expectations for Doctoral Students in Ontario

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 August 2019

The journey of thesis supervisors from novice to expert: a grounded theory study

- Leila Bazrafkan 1 ,

- Alireza Yousefy 2 ,

- Mitra Amini 1 &

- Nikoo Yamani 2

BMC Medical Education volume 19 , Article number: 320 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

9694 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

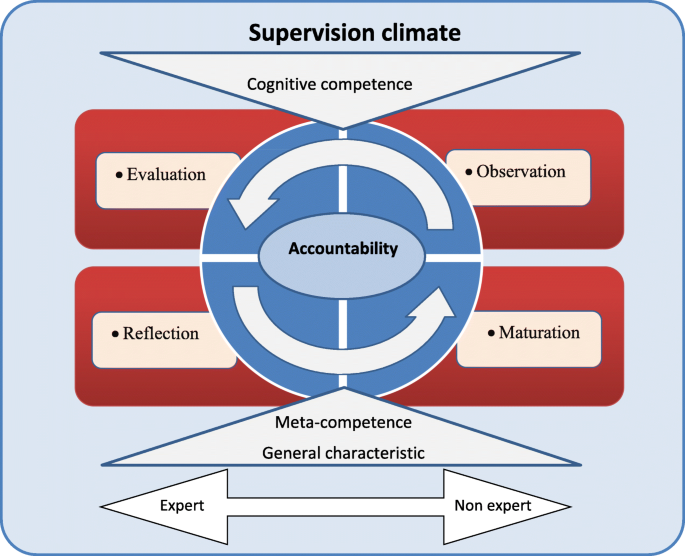

Supervision is a well-defined interpersonal relationship between the thesis supervisors and their students. The purpose of this study was to identify the patterns which can explain the process of expertise attainment by thesis supervisors. We aimed at developing a conceptual framework/model to explain this development based on the experience of both students and supervisors.

We have conducted a qualitative grounded theory study in 20 universities of medical sciences in Iran since 2017 by using purposive, snowball sampling, and theoretical sampling and enrolled 84 participants. The data were gathered through semi-structured interviews. Based on the encoding approach of Strauss and Corbin (1998), the data underwent open, axial, and selective coding by constant comparative analysis. Then, the core variables were selected, and a model was developed.

We could obtain three themes and seven related subthemes, the central variable, which explains the process of expertise as the phenomenon of concentration and makes an association among the subthemes, was interactive accountability. The key dimensions during expertise process which generated the supervisors’ competence development in research supervision consisted maturation; also, seven subthemes as curious observation, evaluation of the reality, poorly structured rules, lack of time, reflection in action, reflection on action, and interactive accountability emerged which explain the process of expertise attainment by thesis supervisors.

Conclusions

As the core variable in the expertise process, accountability must be considered in expertise development program planning and decision- making. In other words, efforts must be made to improve responsibility and responsiveness.

Peer Review reports