- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Editorial article, editorial: gender equality and women’s empowerment in education.

- 1 Department of Specific Didactics, Faculty of Education, University of Burgos, Burgos, Spain

- 2 Department of Educational Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Editorial on the Research Topic Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Education

Current scholarly literature shows that gender inequalities are still present in the process of curricular decision making and teacher practices. These inequalities are expressed through the selection of educational content, the application of methodological strategies, the selection of teaching resources, interpersonal relationships, specific task assignments, or even seating choices within the classroom. These ongoing gender-related issues drive the need for teachers to receive specific and transversal training in this area. Such trainings should be aimed at revealing gender relations as a type of power relationship for the promotion of social change.

The literature in the field of teacher training indicates that the maintenance of gender stereotypes and biases in teacher discourses and practices reinforces the sex-gender system and, consequently, inequalities. Further research is therefore still needed to study the discourses that emerged from the teaching practices around gender. Moreover, research in this field should encourage critical reflection on teacher training plans and the teaching curriculum itself.

The adoption of coeducational approaches and the promotion of education in and for gender equality entails transforming the traditional teaching curriculum to overcome the androcentric constructive bases of historical, social, and literary knowledge. Such transformation would also motivate the incorporation of “polysemic views” in the understanding and interpretation of social reality. Even today, it is common to recognize in mainstream social communication discourses, such as advertising or audio-visual artistic expressions, clear imagery of unquestionable, allegedly identarian gender cultural patterns. The overcoming or relativization of these patterns should necessarily go through the reexamination of curricular content.

The eradication of gender inequalities requires not only the integration of all the voices that have built social knowledge but also the overcoming of gender stereotypes within the education system. It is thus essential to identify the shortcomings of teachers’ training and encourage gender studies as a requisite for their curricula in order to achieve inclusive, plural, and diverse models for teaching practices.

This Research Topic includes 15 manuscripts, from nine prestigious international academic institutions (Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Finland, Germany, Spain, and Sweden) on important topics related to the inclusion of gender inequalities in teacher training, and the analysis of this concept in the official school curriculum, materials, and teacher practices.

The experiences and socio-cultural constructions of the concept of gender constitute the explanatory core of the research problem addressed in “ The Challenge of Women’s Inclusion for Novel Teachers. Case Study in a Teacher Educator Public University ”. This research analyzes the representations of novice teachers of History and Social Sciences on the presence and absence of women’s historical experience in their teaching practices. The research demonstrates the permanence of positivist and androcentric epistemological approaches in the teaching of History, and highlights the urgency of addressing gender inequalities as one of the most pressing social problems of our contemporaneity. In this vein, “ Classical Sociology Through the Lens of Gendered Experiences ” seeks to promote discussion on the mediating role of gendered experiences in classical sociology’s theories of the move towards modern society. This study evidences the constructive relativity of social knowledge and its consequences for sociological teaching and learning.

From the conception of a socio-constructive nature of sexism, the research “ Intersections Around Ambivalent Sexism: Internalized Homonegativity, Resistance to Heteronormativity and Other Correlates ” explores the levels of internalized sexism and homonegativity, and the resistance to heteronormativity of Spanish psychology students. Its results are consistent with those obtained in the study “ Evaluation of Sexist and Prejudiced Attitudes Toward Homosexuality in Spanish Future Teachers: Analysis of Related Variables ”, focused on the analysis of sexist and prejudiced attitudes toward homosexuality of future Spanish teachers. Both studies show the influence of factors such as political ideology, gender identity and sexual orientation on students’ beliefs and perceptions. They also point out the need to advance in the eradication of discrimination based on sex and sexual diversity in the training of future professionals, and the implementation of intersectional approaches to understand the sexist construct.

The consequences of the invisibility of female referents in education and, therefore, of models on which to build plural and empowered identities, derives from the limitations inherent in traditional gender expectations and attributions. The educational hegemony of these attributions, the basis of the study “ Nine Contradictory Observations About Girls’ and Boys’ Upbringing and Education—The Strength-Based Approach as the Way to Eliminate the Gender Gap ”, continue to limit the potential expectations and talents of girls. Through “nine contradictory observations”, this article directs its proposal towards a “strength-based approach” as a way to eradicate the gender gap. Along these lines, “ Mindfulness and Empathy: Mediating Factors and Gender Differences in a Spanish Sample ” highlights the lack of studies aimed at analyzing the potential moderating role of gender in the development of empathic skills.

The research production around the gender gap and gender-segregated differentiation seems not to have received the desired impact in educational social spaces. From this perspective, on the one hand, the article “ Differentiations in Visibility-Male Advantages and Female Disadvantages in Gender-Segregated Programmes ” starts from the differential articulation of inter- and intra-group visibility, by gender, in students, underrepresented in their programmes. On the other hand, the works “ Distributing Feedback Wisely to Empower Girls in STEM ” and “ Girls in STEM: Is It a Female Role-Model Thing? ” highlight the still distant presence of women in the development of STEM professions, a circumstance originating in the educational context and influenced, therefore, by traditional gender models and by social factors that have an impact on the construction of personal identities, as also evidenced by the work “ What Dominates the Female Class Identification? Evidence From China ”.

These constructed identities are revealed in the underestimation of the self-efficacy of secondary school students regarding their competences in STEM subjects, as shown in the work “ Parent and Teacher Depictions of Gender Gaps in Secondary Student Appraisals of Their Academic Competences ”. Consequently, the analysis of self-efficacy, expectations of results, interest in STEM areas and the intervention in the classrooms of plural female role models are proposed as necessary working spaces to redirect this trend. These results are completed with the analysis of the potential influence of gender stereotypes in biased student evaluations of teaching in “ Gender Stereotypes in Student Evaluations of Teaching ”.

From the area of Brazilian physical education, “ Gender Participation and Preference: A Multiple-Case Study on Teaching Circus at PE in Brazilians Schools ” reports on the elective influence of Primary Education teachers in the assignment of circus physical activities according to gender, extensible to the sports activities of traditional teaching. In order to advance in critical and emancipatory training proposals in gender equality in this area, “ Breaking Cultural ‘Taboos’ About the Body and Gender: Brazilian Students’ Emancipation From a Thematic Perspective of School Physical Education ” stresses the importance of teaching programs oriented to the cultural construction of the differential concept of the body. From this perspective, the work “ REFLECT—A Teacher Training Program to Promote Gender Equality in Schools ” emphasizes the hegemonic role of socializing agents in maintaining the status quo of gender stereotypes in education and in the future professional development of men and women. As a response to the permanence of the sex-gender system, and to the evidence of the influence of teachers’ attitudes and practices in the promotion of truly coeducational educational environments, this program, aimed at future teachers of Secondary Education, aims to contribute, in a sustainable way, to gender equality from the educational spaces of subjective action (such as self-efficacy), and objective action (teaching methods and knowledge).

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This Research Topic was completed with the main support of the Research Group Recognized in Didactics of History and Social Sciences (DHISO) (cod. 137), directed by Prof. Dr. Delfín Ortega-Sánchez (University of Burgos, Spain). Likewise, it has also been carried out within the framework of the projects Teach and learn to interpret contemporary problems and conflicts. What do social sciences contribute to the formation of a critical global citizenship? (EDU2016-80145-P), financed by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spanish Government), and Future Education and Democratic Hope. Rethinking Social Studies Education in changing times (PID2019-107383RB-I00), financed by the Ministry of Science, and Innovation (Spanish Government).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Keywords: gender equality, teacher training, gender representation, gender stereotypes, higher education, primary and secondary education, early childhood education

Citation: Ortega-Sánchez D, Sanz de la Cal E, Ibáñez Quintana J and Borghi B (2022) Editorial: Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Education. Front. Educ. 7:833977. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.833977

Received: 12 December 2021; Accepted: 10 January 2022; Published: 26 January 2022.

Edited and reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Ortega-Sánchez, Sanz de la Cal, Ibáñez Quintana and Borghi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, [email protected]

This article is part of the Research Topic

Gender Equality and Women's Empowerment in Education

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Twenty years of gender equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator

Paola belingheri.

1 Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Energia, dei Sistemi, del Territorio e delle Costruzioni, Università degli Studi di Pisa, Largo L. Lazzarino, Pisa, Italy

Filippo Chiarello

Andrea fronzetti colladon.

2 Department of Engineering, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy

3 Department of Management, Kozminski University, Warsaw, Poland

Paola Rovelli

4 Faculty of Economics and Management, Centre for Family Business Management, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Bozen-Bolzano, Italy

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files. The only exception is the text of the abstracts (over 15,000) that we have downloaded from Scopus. These abstracts can be retrieved from Scopus, but we do not have permission to redistribute them.

Gender equality is a major problem that places women at a disadvantage thereby stymieing economic growth and societal advancement. In the last two decades, extensive research has been conducted on gender related issues, studying both their antecedents and consequences. However, existing literature reviews fail to provide a comprehensive and clear picture of what has been studied so far, which could guide scholars in their future research. Our paper offers a scoping review of a large portion of the research that has been published over the last 22 years, on gender equality and related issues, with a specific focus on business and economics studies. Combining innovative methods drawn from both network analysis and text mining, we provide a synthesis of 15,465 scientific articles. We identify 27 main research topics, we measure their relevance from a semantic point of view and the relationships among them, highlighting the importance of each topic in the overall gender discourse. We find that prominent research topics mostly relate to women in the workforce–e.g., concerning compensation, role, education, decision-making and career progression. However, some of them are losing momentum, and some other research trends–for example related to female entrepreneurship, leadership and participation in the board of directors–are on the rise. Besides introducing a novel methodology to review broad literature streams, our paper offers a map of the main gender-research trends and presents the most popular and the emerging themes, as well as their intersections, outlining important avenues for future research.

Introduction

The persistent gender inequalities that currently exist across the developed and developing world are receiving increasing attention from economists, policymakers, and the general public [e.g., 1 – 3 ]. Economic studies have indicated that women’s education and entry into the workforce contributes to social and economic well-being [e.g., 4 , 5 ], while their exclusion from the labor market and from managerial positions has an impact on overall labor productivity and income per capita [ 6 , 7 ]. The United Nations selected gender equality, with an emphasis on female education, as part of the Millennium Development Goals [ 8 ], and gender equality at-large as one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be achieved by 2030 [ 9 ]. These latter objectives involve not only developing nations, but rather all countries, to achieve economic, social and environmental well-being.

As is the case with many SDGs, gender equality is still far from being achieved and persists across education, access to opportunities, or presence in decision-making positions [ 7 , 10 , 11 ]. As we enter the last decade for the SDGs’ implementation, and while we are battling a global health pandemic, effective and efficient action becomes paramount to reach this ambitious goal.

Scholars have dedicated a massive effort towards understanding gender equality, its determinants, its consequences for women and society, and the appropriate actions and policies to advance women’s equality. Many topics have been covered, ranging from women’s education and human capital [ 12 , 13 ] and their role in society [e.g., 14 , 15 ], to their appointment in firms’ top ranked positions [e.g., 16 , 17 ] and performance implications [e.g., 18 , 19 ]. Despite some attempts, extant literature reviews provide a narrow view on these issues, restricted to specific topics–e.g., female students’ presence in STEM fields [ 20 ], educational gender inequality [ 5 ], the gender pay gap [ 21 ], the glass ceiling effect [ 22 ], leadership [ 23 ], entrepreneurship [ 24 ], women’s presence on the board of directors [ 25 , 26 ], diversity management [ 27 ], gender stereotypes in advertisement [ 28 ], or specific professions [ 29 ]. A comprehensive view on gender-related research, taking stock of key findings and under-studied topics is thus lacking.

Extant literature has also highlighted that gender issues, and their economic and social ramifications, are complex topics that involve a large number of possible antecedents and outcomes [ 7 ]. Indeed, gender equality actions are most effective when implemented in unison with other SDGs (e.g., with SDG 8, see [ 30 ]) in a synergetic perspective [ 10 ]. Many bodies of literature (e.g., business, economics, development studies, sociology and psychology) approach the problem of achieving gender equality from different perspectives–often addressing specific and narrow aspects. This sometimes leads to a lack of clarity about how different issues, circumstances, and solutions may be related in precipitating or mitigating gender inequality or its effects. As the number of papers grows at an increasing pace, this issue is exacerbated and there is a need to step back and survey the body of gender equality literature as a whole. There is also a need to examine synergies between different topics and approaches, as well as gaps in our understanding of how different problems and solutions work together. Considering the important topic of women’s economic and social empowerment, this paper aims to fill this gap by answering the following research question: what are the most relevant findings in the literature on gender equality and how do they relate to each other ?

To do so, we conduct a scoping review [ 31 ], providing a synthesis of 15,465 articles dealing with gender equity related issues published in the last twenty-two years, covering both the periods of the MDGs and the SDGs (i.e., 2000 to mid 2021) in all the journals indexed in the Academic Journal Guide’s 2018 ranking of business and economics journals. Given the huge amount of research conducted on the topic, we adopt an innovative methodology, which relies on social network analysis and text mining. These techniques are increasingly adopted when surveying large bodies of text. Recently, they were applied to perform analysis of online gender communication differences [ 32 ] and gender behaviors in online technology communities [ 33 ], to identify and classify sexual harassment instances in academia [ 34 ], and to evaluate the gender inclusivity of disaster management policies [ 35 ].

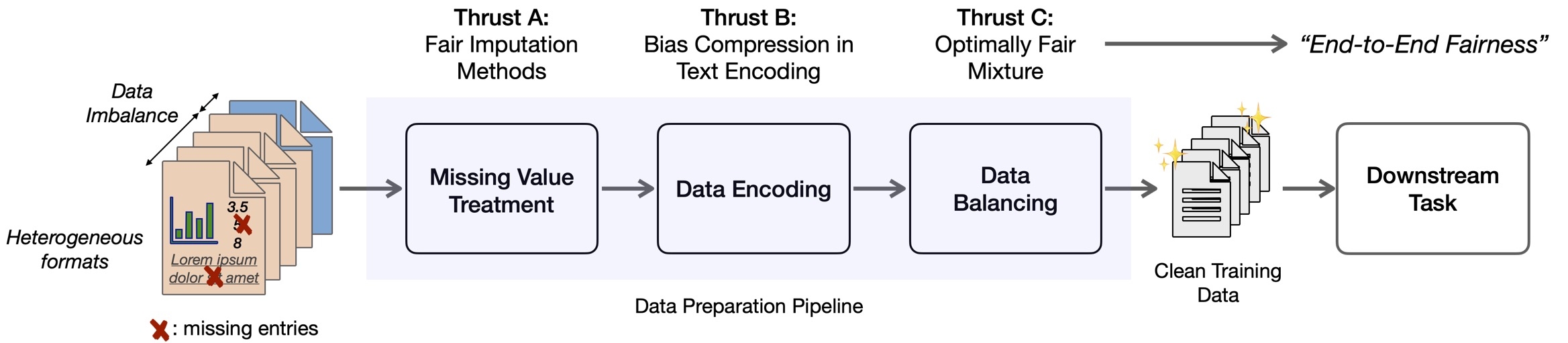

Applied to the title, abstracts and keywords of the articles in our sample, this methodology allows us to identify a set of 27 recurrent topics within which we automatically classify the papers. Introducing additional novelty, by means of the Semantic Brand Score (SBS) indicator [ 36 ] and the SBS BI app [ 37 ], we assess the importance of each topic in the overall gender equality discourse and its relationships with the other topics, as well as trends over time, with a more accurate description than that offered by traditional literature reviews relying solely on the number of papers presented in each topic.

This methodology, applied to gender equality research spanning the past twenty-two years, enables two key contributions. First, we extract the main message that each document is conveying and how this is connected to other themes in literature, providing a rich picture of the topics that are at the center of the discourse, as well as of the emerging topics. Second, by examining the semantic relationship between topics and how tightly their discourses are linked, we can identify the key relationships and connections between different topics. This semi-automatic methodology is also highly reproducible with minimum effort.

This literature review is organized as follows. In the next section, we present how we selected relevant papers and how we analyzed them through text mining and social network analysis. We then illustrate the importance of 27 selected research topics, measured by means of the SBS indicator. In the results section, we present an overview of the literature based on the SBS results–followed by an in-depth narrative analysis of the top 10 topics (i.e., those with the highest SBS) and their connections. Subsequently, we highlight a series of under-studied connections between the topics where there is potential for future research. Through this analysis, we build a map of the main gender-research trends in the last twenty-two years–presenting the most popular themes. We conclude by highlighting key areas on which research should focused in the future.

Our aim is to map a broad topic, gender equality research, that has been approached through a host of different angles and through different disciplines. Scoping reviews are the most appropriate as they provide the freedom to map different themes and identify literature gaps, thereby guiding the recommendation of new research agendas [ 38 ].

Several practical approaches have been proposed to identify and assess the underlying topics of a specific field using big data [ 39 – 41 ], but many of them fail without proper paper retrieval and text preprocessing. This is specifically true for a research field such as the gender-related one, which comprises the work of scholars from different backgrounds. In this section, we illustrate a novel approach for the analysis of scientific (gender-related) papers that relies on methods and tools of social network analysis and text mining. Our procedure has four main steps: (1) data collection, (2) text preprocessing, (3) keywords extraction and classification, and (4) evaluation of semantic importance and image.

Data collection

In this study, we analyze 22 years of literature on gender-related research. Following established practice for scoping reviews [ 42 ], our data collection consisted of two main steps, which we summarize here below.

Firstly, we retrieved from the Scopus database all the articles written in English that contained the term “gender” in their title, abstract or keywords and were published in a journal listed in the Academic Journal Guide 2018 ranking of the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) ( https://charteredabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/AJG2018-Methodology.pdf ), considering the time period from Jan 2000 to May 2021. We used this information considering that abstracts, titles and keywords represent the most informative part of a paper, while using the full-text would increase the signal-to-noise ratio for information extraction. Indeed, these textual elements already demonstrated to be reliable sources of information for the task of domain lexicon extraction [ 43 , 44 ]. We chose Scopus as source of literature because of its popularity, its update rate, and because it offers an API to ease the querying process. Indeed, while it does not allow to retrieve the full text of scientific articles, the Scopus API offers access to titles, abstracts, citation information and metadata for all its indexed scholarly journals. Moreover, we decided to focus on the journals listed in the AJG 2018 ranking because we were interested in reviewing business and economics related gender studies only. The AJG is indeed widely used by universities and business schools as a reference point for journal and research rigor and quality. This first step, executed in June 2021, returned more than 55,000 papers.

In the second step–because a look at the papers showed very sparse results, many of which were not in line with the topic of this literature review (e.g., papers dealing with health care or medical issues, where the word gender indicates the gender of the patients)–we applied further inclusion criteria to make the sample more focused on the topic of this literature review (i.e., women’s gender equality issues). Specifically, we only retained those papers mentioning, in their title and/or abstract, both gender-related keywords (e.g., daughter, female, mother) and keywords referring to bias and equality issues (e.g., equality, bias, diversity, inclusion). After text pre-processing (see next section), keywords were first identified from a frequency-weighted list of words found in the titles, abstracts and keywords in the initial list of papers, extracted through text mining (following the same approach as [ 43 ]). They were selected by two of the co-authors independently, following respectively a bottom up and a top-down approach. The bottom-up approach consisted of examining the words found in the frequency-weighted list and classifying those related to gender and equality. The top-down approach consisted in searching in the word list for notable gender and equality-related words. Table 1 reports the sets of keywords we considered, together with some examples of words that were used to search for their presence in the dataset (a full list is provided in the S1 Text ). At end of this second step, we obtained a final sample of 15,465 relevant papers.

| Keyword set | Examples of searched words | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Bride | |

| Daughter | , | |

| Female | , | |

| Femini | , , | |

| Girl | ||

| Lady | , | |

| Maid | ||

| Mother | , , | |

| Queen | ||

| Widow | ||

| Wife | , | |

| Woman | , | |

| Equality | Bias | , , |

| Diversity | , | |

| Empower | , , | |

| Equality | , , | |

| Equity | , , | |

| Homeworking | , , | |

| Inclusion | , , | |

| Quota | ||

| Stereotype | , , |

Text processing and keyword extraction

Text preprocessing aims at structuring text into a form that can be analyzed by statistical models. In the present section, we describe the preprocessing steps we applied to paper titles and abstracts, which, as explained below, partially follow a standard text preprocessing pipeline [ 45 ]. These activities have been performed using the R package udpipe [ 46 ].

The first step is n-gram extraction (i.e., a sequence of words from a given text sample) to identify which n-grams are important in the analysis, since domain-specific lexicons are often composed by bi-grams and tri-grams [ 47 ]. Multi-word extraction is usually implemented with statistics and linguistic rules, thus using the statistical properties of n-grams or machine learning approaches [ 48 ]. However, for the present paper, we used Scopus metadata in order to have a more effective and efficient n-grams collection approach [ 49 ]. We used the keywords of each paper in order to tag n-grams with their associated keywords automatically. Using this greedy approach, it was possible to collect all the keywords listed by the authors of the papers. From this list, we extracted only keywords composed by two, three and four words, we removed all the acronyms and rare keywords (i.e., appearing in less than 1% of papers), and we clustered keywords showing a high orthographic similarity–measured using a Levenshtein distance [ 50 ] lower than 2, considering these groups of keywords as representing same concepts, but expressed with different spelling. After tagging the n-grams in the abstracts, we followed a common data preparation pipeline that consists of the following steps: (i) tokenization, that splits the text into tokens (i.e., single words and previously tagged multi-words); (ii) removal of stop-words (i.e. those words that add little meaning to the text, usually being very common and short functional words–such as “and”, “or”, or “of”); (iii) parts-of-speech tagging, that is providing information concerning the morphological role of a word and its morphosyntactic context (e.g., if the token is a determiner, the next token is a noun or an adjective with very high confidence, [ 51 ]); and (iv) lemmatization, which consists in substituting each word with its dictionary form (or lemma). The output of the latter step allows grouping together the inflected forms of a word. For example, the verbs “am”, “are”, and “is” have the shared lemma “be”, or the nouns “cat” and “cats” both share the lemma “cat”. We preferred lemmatization over stemming [ 52 ] in order to obtain more interpretable results.

In addition, we identified a further set of keywords (with respect to those listed in the “keywords” field) by applying a series of automatic words unification and removal steps, as suggested in past research [ 53 , 54 ]. We removed: sparse terms (i.e., occurring in less than 0.1% of all documents), common terms (i.e., occurring in more than 10% of all documents) and retained only nouns and adjectives. It is relevant to notice that no document was lost due to these steps. We then used the TF-IDF function [ 55 ] to produce a new list of keywords. We additionally tested other approaches for the identification and clustering of keywords–such as TextRank [ 56 ] or Latent Dirichlet Allocation [ 57 ]–without obtaining more informative results.

Classification of research topics

To guide the literature analysis, two experts met regularly to examine the sample of collected papers and to identify the main topics and trends in gender research. Initially, they conducted brainstorming sessions on the topics they expected to find, due to their knowledge of the literature. This led to an initial list of topics. Subsequently, the experts worked independently, also supported by the keywords in paper titles and abstracts extracted with the procedure described above.

Considering all this information, each expert identified and clustered relevant keywords into topics. At the end of the process, the two assignments were compared and exhibited a 92% agreement. Another meeting was held to discuss discordant cases and reach a consensus. This resulted in a list of 27 topics, briefly introduced in Table 2 and subsequently detailed in the following sections.

| Topic | Short Description |

|---|---|

| Behavior | Behavioral aspects related to gender |

| Board of directors | Women in boards of directors |

| Career Progression | Women’s promotion and career advancement |

| Compensation | Salary and rewards in relation to employment |

| Culture | Ideas, customs and social behaviors, including bias and stereotypes |

| Decision-making | The decision-making process |

| Education | Primary, secondary and tertiary education |

| Empowerment | Authority, power and self-confidence |

| Entrepreneurship | Women starting their own enterprises |

| Family | Women’s relationship with family and family obligations, wok-life balance |

| Feminine | Female characteristics |

| Governance | The governance structures of firms and society |

| Hiring | Appointing women to positions within the workforce |

| Human Capital | The intellectual capital resulting from education and social capital |

| Leadership | Leadership skills and leadership positions |

| Management | Managerial practices and processes |

| Masculine | Male characteristics |

| Network | Networking dynamics as they relate to women |

| Organization | The organization of firms |

| Parenting | The act of raising children and its implications |

| Performance | Measuring the work output of individuals, teams and organizations |

| Personality | Traits and individual characteristics of women |

| Politics | Policies and regulations, women in politics |

| Reputation | How women are viewed by their colleagues, peers and society |

| Role | The roles covered by women in the workforce |

| Sustainability | Women’s relation to sustainability and social responsibility |

| Well-Being | Psychological, personal, and social welfare of women |

Evaluation of semantic importance

Working on the lemmatized corpus of the 15,465 papers included in our sample, we proceeded with the evaluation of semantic importance trends for each topic and with the analysis of their connections and prevalent textual associations. To this aim, we used the Semantic Brand Score indicator [ 36 ], calculated through the SBS BI webapp [ 37 ] that also produced a brand image report for each topic. For this study we relied on the computing resources of the ENEA/CRESCO infrastructure [ 58 ].

The Semantic Brand Score (SBS) is a measure of semantic importance that combines methods of social network analysis and text mining. It is usually applied for the analysis of (big) textual data to evaluate the importance of one or more brands, names, words, or sets of keywords [ 36 ]. Indeed, the concept of “brand” is intended in a flexible way and goes beyond products or commercial brands. In this study, we evaluate the SBS time-trends of the keywords defining the research topics discussed in the previous section. Semantic importance comprises the three dimensions of topic prevalence, diversity and connectivity. Prevalence measures how frequently a research topic is used in the discourse. The more a topic is mentioned by scientific articles, the more the research community will be aware of it, with possible increase of future studies; this construct is partly related to that of brand awareness [ 59 ]. This effect is even stronger, considering that we are analyzing the title, abstract and keywords of the papers, i.e. the parts that have the highest visibility. A very important characteristic of the SBS is that it considers the relationships among words in a text. Topic importance is not just a matter of how frequently a topic is mentioned, but also of the associations a topic has in the text. Specifically, texts are transformed into networks of co-occurring words, and relationships are studied through social network analysis [ 60 ]. This step is necessary to calculate the other two dimensions of our semantic importance indicator. Accordingly, a social network of words is generated for each time period considered in the analysis–i.e., a graph made of n nodes (words) and E edges weighted by co-occurrence frequency, with W being the set of edge weights. The keywords representing each topic were clustered into single nodes.

The construct of diversity relates to that of brand image [ 59 ], in the sense that it considers the richness and distinctiveness of textual (topic) associations. Considering the above-mentioned networks, we calculated diversity using the distinctiveness centrality metric–as in the formula presented by Fronzetti Colladon and Naldi [ 61 ].

Lastly, connectivity was measured as the weighted betweenness centrality [ 62 , 63 ] of each research topic node. We used the formula presented by Wasserman and Faust [ 60 ]. The dimension of connectivity represents the “brokerage power” of each research topic–i.e., how much it can serve as a bridge to connect other terms (and ultimately topics) in the discourse [ 36 ].

The SBS is the final composite indicator obtained by summing the standardized scores of prevalence, diversity and connectivity. Standardization was carried out considering all the words in the corpus, for each specific timeframe.

This methodology, applied to a large and heterogeneous body of text, enables to automatically identify two important sets of information that add value to the literature review. Firstly, the relevance of each topic in literature is measured through a composite indicator of semantic importance, rather than simply looking at word frequencies. This provides a much richer picture of the topics that are at the center of the discourse, as well as of the topics that are emerging in the literature. Secondly, it enables to examine the extent of the semantic relationship between topics, looking at how tightly their discourses are linked. In a field such as gender equality, where many topics are closely linked to each other and present overlaps in issues and solutions, this methodology offers a novel perspective with respect to traditional literature reviews. In addition, it ensures reproducibility over time and the possibility to semi-automatically update the analysis, as new papers become available.

Overview of main topics

In terms of descriptive textual statistics, our corpus is made of 15,465 text documents, consisting of a total of 2,685,893 lemmatized tokens (words) and 32,279 types. As a result, the type-token ratio is 1.2%. The number of hapaxes is 12,141, with a hapax-token ratio of 37.61%.

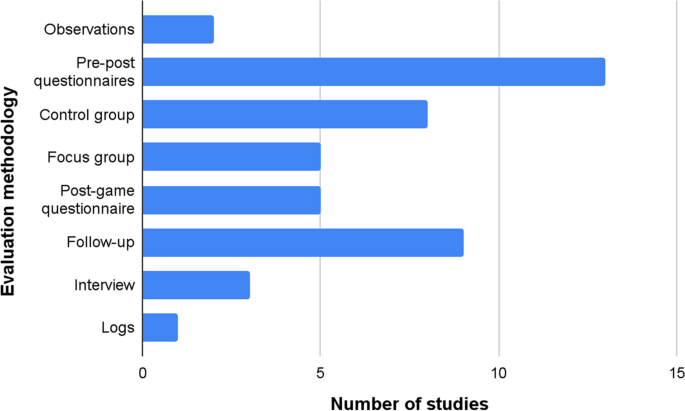

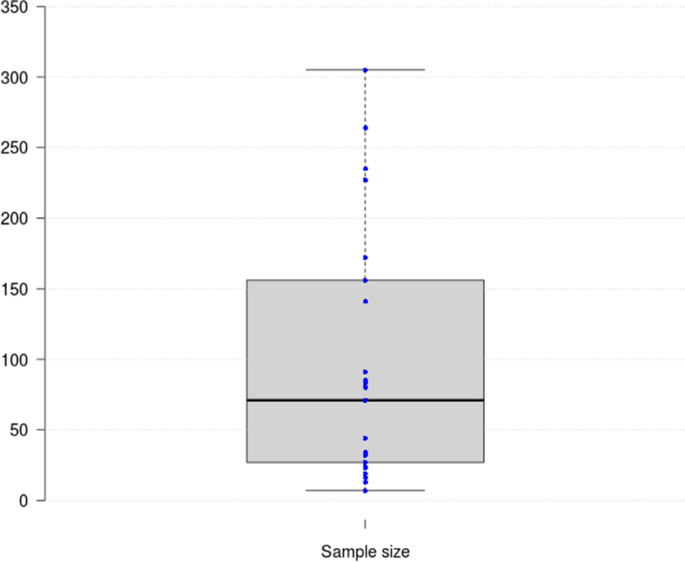

Fig 1 shows the list of 27 topics by decreasing SBS. The most researched topic is compensation , exceeding all others in prevalence, diversity, and connectivity. This means it is not only mentioned more often than other topics, but it is also connected to a greater number of other topics and is central to the discourse on gender equality. The next four topics are, in order of SBS, role , education , decision-making , and career progression . These topics, except for education , all concern women in the workforce. Between these first five topics and the following ones there is a clear drop in SBS scores. In particular, the topics that follow have a lower connectivity than the first five. They are hiring , performance , behavior , organization , and human capital . Again, except for behavior and human capital , the other three topics are purely related to women in the workforce. After another drop-off, the following topics deal prevalently with women in society. This trend highlights that research on gender in business journals has so far mainly paid attention to the conditions that women experience in business contexts, while also devoting some attention to women in society.

Fig 2 shows the SBS time series of the top 10 topics. While there has been a general increase in the number of Scopus-indexed publications in the last decade, we notice that some SBS trends remain steady, or even decrease. In particular, we observe that the main topic of the last twenty-two years, compensation , is losing momentum. Since 2016, it has been surpassed by decision-making , education and role , which may indicate that literature is increasingly attempting to identify root causes of compensation inequalities. Moreover, in the last two years, the topics of hiring , performance , and organization are experiencing the largest importance increase.

Fig 3 shows the SBS time trends of the remaining 17 topics (i.e., those not in the top 10). As we can see from the graph, there are some that maintain a steady trend–such as reputation , management , networks and governance , which also seem to have little importance. More relevant topics with average stationary trends (except for the last two years) are culture , family , and parenting . The feminine topic is among the most important here, and one of those that exhibit the larger variations over time (similarly to leadership ). On the other hand, the are some topics that, even if not among the most important, show increasing SBS trends; therefore, they could be considered as emerging topics and could become popular in the near future. These are entrepreneurship , leadership , board of directors , and sustainability . These emerging topics are also interesting to anticipate future trends in gender equality research that are conducive to overall equality in society.

In addition to the SBS score of the different topics, the network of terms they are associated to enables to gauge the extent to which their images (textual associations) overlap or differ ( Fig 4 ).

There is a central cluster of topics with high similarity, which are all connected with women in the workforce. The cluster includes topics such as organization , decision-making , performance , hiring , human capital , education and compensation . In addition, the topic of well-being is found within this cluster, suggesting that women’s equality in the workforce is associated to well-being considerations. The emerging topics of entrepreneurship and leadership are also closely connected with each other, possibly implying that leadership is a much-researched quality in female entrepreneurship. Topics that are relatively more distant include personality , politics , feminine , empowerment , management , board of directors , reputation , governance , parenting , masculine and network .

The following sections describe the top 10 topics and their main associations in literature (see Table 3 ), while providing a brief overview of the emerging topics.

| Topic | Top associations (other topics in bold) |

|---|---|

| Behavior | social, work, , differences, related, , child, positive, group, individual, self, influence, relationship, stereotype, health, inequality, change, , student, participant, , , experience, , , intention |

| Career Progression | , inequality, difference , work, social, equity, , , , , level, , development, policy, examine, role, self, experience, , support, , individual, , perceive, academic, differences |

| Compensation | gap, , difference, inequality, , , work, increase, higher, lower, market, less, labor, household, low, , age, time, high, labour, attention, discrimination, change, country, individual, status |

| Decision Making | , , social, work, , , inequality, household, group, policy, , process, , health, , level, role, individual, , , equity, , stereotype, different, , change |

| Education | age, inequality, level, , study, social, health, gap, status, equity, student, , , child, , school, economic, policy, work, , experience, higher, access, household, development |

| Hiring | , work, , , discrimination, level, , time, , gap, sector, , market, social, increase, status, , policy, inequality, experience, differences, lower, equity, high, data, satisfaction, |

| Human Capital | , , work, , social, , , , self, , health, , , student, , group, child, individual, development, age, differences, lack, gap, focus, change |

| Organization | work, , , inequality, , , social, diversity, policy, level, change, , employee, individual, , equity, , practice, value, , management, structure, discrimination, , |

| Performance | , , , stereotype, work, , , , , self, impact, social, , , difference, high, firm, threat, student, inequality, role, , increase, relationship, experience |

| Role | , , work, , , , firm, , , social, , role, , employee, less, increase, experience, traditional, , stereotype, sector, , business, gap, group, data |

Compensation

The topic of compensation is related to the topics of role , hiring , education and career progression , however, also sees a very high association with the words gap and inequality . Indeed, a well-known debate in degrowth economics centers around whether and how to adequately compensate women for their childbearing, childrearing, caregiver and household work [e.g., 30 ].

Even in paid work, women continue being offered lower compensations than their male counterparts who have the same job or cover the same role [ 64 – 67 ]. This severe inequality has been widely studied by scholars over the last twenty-two years. Dealing with this topic, some specific roles have been addressed. Specifically, research highlighted differences in compensation between female and male CEOs [e.g., 68 ], top executives [e.g., 69 ], and boards’ directors [e.g., 70 ]. Scholars investigated the determinants of these gaps, such as the gender composition of the board [e.g., 71 – 73 ] or women’s individual characteristics [e.g., 71 , 74 ].

Among these individual characteristics, education plays a relevant role [ 75 ]. Education is indeed presented as the solution for women, not only to achieve top executive roles, but also to reduce wage inequality [e.g., 76 , 77 ]. Past research has highlighted education influences on gender wage gaps, specifically referring to gender differences in skills [e.g., 78 ], college majors [e.g., 79 ], and college selectivity [e.g., 80 ].

Finally, the wage gap issue is strictly interrelated with hiring –e.g., looking at whether being a mother affects hiring and compensation [e.g., 65 , 81 ] or relating compensation to unemployment [e.g., 82 ]–and career progression –for instance looking at meritocracy [ 83 , 84 ] or the characteristics of the boss for whom women work [e.g., 85 ].

The roles covered by women have been deeply investigated. Scholars have focused on the role of women in their families and the society as a whole [e.g., 14 , 15 ], and, more widely, in business contexts [e.g., 18 , 81 ]. Indeed, despite still lagging behind their male counterparts [e.g., 86 , 87 ], in the last decade there has been an increase in top ranked positions achieved by women [e.g., 88 , 89 ]. Following this phenomenon, scholars have posed greater attention towards the presence of women in the board of directors [e.g., 16 , 18 , 90 , 91 ], given the increasing pressure to appoint female directors that firms, especially listed ones, have experienced. Other scholars have focused on the presence of women covering the role of CEO [e.g., 17 , 92 ] or being part of the top management team [e.g., 93 ]. Irrespectively of the level of analysis, all these studies tried to uncover the antecedents of women’s presence among top managers [e.g., 92 , 94 ] and the consequences of having a them involved in the firm’s decision-making –e.g., on performance [e.g., 19 , 95 , 96 ], risk [e.g., 97 , 98 ], and corporate social responsibility [e.g., 99 , 100 ].

Besides studying the difficulties and discriminations faced by women in getting a job [ 81 , 101 ], and, more specifically in the hiring , appointment, or career progression to these apical roles [e.g., 70 , 83 ], the majority of research of women’s roles dealt with compensation issues. Specifically, scholars highlight the pay-gap that still exists between women and men, both in general [e.g., 64 , 65 ], as well as referring to boards’ directors [e.g., 70 , 102 ], CEOs and executives [e.g., 69 , 103 , 104 ].

Finally, other scholars focused on the behavior of women when dealing with business. In this sense, particular attention has been paid to leadership and entrepreneurial behaviors. The former quite overlaps with dealing with the roles mentioned above, but also includes aspects such as leaders being stereotyped as masculine [e.g., 105 ], the need for greater exposure to female leaders to reduce biases [e.g., 106 ], or female leaders acting as queen bees [e.g., 107 ]. Regarding entrepreneurship , scholars mainly investigated women’s entrepreneurial entry [e.g., 108 , 109 ], differences between female and male entrepreneurs in the evaluations and funding received from investors [e.g., 110 , 111 ], and their performance gap [e.g., 112 , 113 ].

Education has long been recognized as key to social advancement and economic stability [ 114 ], for job progression and also a barrier to gender equality, especially in STEM-related fields. Research on education and gender equality is mostly linked with the topics of compensation , human capital , career progression , hiring , parenting and decision-making .

Education contributes to a higher human capital [ 115 ] and constitutes an investment on the part of women towards their future. In this context, literature points to the gender gap in educational attainment, and the consequences for women from a social, economic, personal and professional standpoint. Women are found to have less access to formal education and information, especially in emerging countries, which in turn may cause them to lose social and economic opportunities [e.g., 12 , 116 – 119 ]. Education in local and rural communities is also paramount to communicate the benefits of female empowerment , contributing to overall societal well-being [e.g., 120 ].

Once women access education, the image they have of the world and their place in society (i.e., habitus) affects their education performance [ 13 ] and is passed on to their children. These situations reinforce gender stereotypes, which become self-fulfilling prophecies that may negatively affect female students’ performance by lowering their confidence and heightening their anxiety [ 121 , 122 ]. Besides formal education, also the information that women are exposed to on a daily basis contributes to their human capital . Digital inequalities, for instance, stems from men spending more time online and acquiring higher digital skills than women [ 123 ].

Education is also a factor that should boost employability of candidates and thus hiring , career progression and compensation , however the relationship between these factors is not straightforward [ 115 ]. First, educational choices ( decision-making ) are influenced by variables such as self-efficacy and the presence of barriers, irrespectively of the career opportunities they offer, especially in STEM [ 124 ]. This brings additional difficulties to women’s enrollment and persistence in scientific and technical fields of study due to stereotypes and biases [ 125 , 126 ]. Moreover, access to education does not automatically translate into job opportunities for women and minority groups [ 127 , 128 ] or into female access to managerial positions [ 129 ].

Finally, parenting is reported as an antecedent of education [e.g., 130 ], with much of the literature focusing on the role of parents’ education on the opportunities afforded to children to enroll in education [ 131 – 134 ] and the role of parenting in their offspring’s perception of study fields and attitudes towards learning [ 135 – 138 ]. Parental education is also a predictor of the other related topics, namely human capital and compensation [ 139 ].

Decision-making

This literature mainly points to the fact that women are thought to make decisions differently than men. Women have indeed different priorities, such as they care more about people’s well-being, working with people or helping others, rather than maximizing their personal (or their firm’s) gain [ 140 ]. In other words, women typically present more communal than agentic behaviors, which are instead more frequent among men [ 141 ]. These different attitude, behavior and preferences in turn affect the decisions they make [e.g., 142 ] and the decision-making of the firm in which they work [e.g., 143 ].

At the individual level, gender affects, for instance, career aspirations [e.g., 144 ] and choices [e.g., 142 , 145 ], or the decision of creating a venture [e.g., 108 , 109 , 146 ]. Moreover, in everyday life, women and men make different decisions regarding partners [e.g., 147 ], childcare [e.g., 148 ], education [e.g., 149 ], attention to the environment [e.g., 150 ] and politics [e.g., 151 ].

At the firm level, scholars highlighted, for example, how the presence of women in the board affects corporate decisions [e.g., 152 , 153 ], that female CEOs are more conservative in accounting decisions [e.g., 154 ], or that female CFOs tend to make more conservative decisions regarding the firm’s financial reporting [e.g., 155 ]. Nevertheless, firm level research also investigated decisions that, influenced by gender bias, affect women, such as those pertaining hiring [e.g., 156 , 157 ], compensation [e.g., 73 , 158 ], or the empowerment of women once appointed [ 159 ].

Career progression

Once women have entered the workforce, the key aspect to achieve gender equality becomes career progression , including efforts toward overcoming the glass ceiling. Indeed, according to the SBS analysis, career progression is highly related to words such as work, social issues and equality. The topic with which it has the highest semantic overlap is role , followed by decision-making , hiring , education , compensation , leadership , human capital , and family .

Career progression implies an advancement in the hierarchical ladder of the firm, assigning managerial roles to women. Coherently, much of the literature has focused on identifying rationales for a greater female participation in the top management team and board of directors [e.g., 95 ] as well as the best criteria to ensure that the decision-makers promote the most valuable employees irrespectively of their individual characteristics, such as gender [e.g., 84 ]. The link between career progression , role and compensation is often provided in practice by performance appraisal exercises, frequently rooted in a culture of meritocracy that guides bonuses, salary increases and promotions. However, performance appraisals can actually mask gender-biased decisions where women are held to higher standards than their male colleagues [e.g., 83 , 84 , 95 , 160 , 161 ]. Women often have less opportunities to gain leadership experience and are less visible than their male colleagues, which constitute barriers to career advancement [e.g., 162 ]. Therefore, transparency and accountability, together with procedures that discourage discretionary choices, are paramount to achieve a fair career progression [e.g., 84 ], together with the relaxation of strict job boundaries in favor of cross-functional and self-directed tasks [e.g., 163 ].

In addition, a series of stereotypes about the type of leadership characteristics that are required for top management positions, which fit better with typical male and agentic attributes, are another key barrier to career advancement for women [e.g., 92 , 160 ].

Hiring is the entrance gateway for women into the workforce. Therefore, it is related to other workforce topics such as compensation , role , career progression , decision-making , human capital , performance , organization and education .

A first stream of literature focuses on the process leading up to candidates’ job applications, demonstrating that bias exists before positions are even opened, and it is perpetuated both by men and women through networking and gatekeeping practices [e.g., 164 , 165 ].

The hiring process itself is also subject to biases [ 166 ], for example gender-congruity bias that leads to men being preferred candidates in male-dominated sectors [e.g., 167 ], women being hired in positions with higher risk of failure [e.g., 168 ] and limited transparency and accountability afforded by written processes and procedures [e.g., 164 ] that all contribute to ascriptive inequality. In addition, providing incentives for evaluators to hire women may actually work to this end; however, this is not the case when supporting female candidates endangers higher-ranking male ones [ 169 ].

Another interesting perspective, instead, looks at top management teams’ composition and the effects on hiring practices, indicating that firms with more women in top management are less likely to lay off staff [e.g., 152 ].

Performance

Several scholars posed their attention towards women’s performance, its consequences [e.g., 170 , 171 ] and the implications of having women in decision-making positions [e.g., 18 , 19 ].

At the individual level, research focused on differences in educational and academic performance between women and men, especially referring to the gender gap in STEM fields [e.g., 171 ]. The presence of stereotype threats–that is the expectation that the members of a social group (e.g., women) “must deal with the possibility of being judged or treated stereotypically, or of doing something that would confirm the stereotype” [ 172 ]–affects women’s interested in STEM [e.g., 173 ], as well as their cognitive ability tests, penalizing them [e.g., 174 ]. A stronger gender identification enhances this gap [e.g., 175 ], whereas mentoring and role models can be used as solutions to this problem [e.g., 121 ]. Despite the negative effect of stereotype threats on girls’ performance [ 176 ], female and male students perform equally in mathematics and related subjects [e.g., 177 ]. Moreover, while individuals’ performance at school and university generally affects their achievements and the field in which they end up working, evidence reveals that performance in math or other scientific subjects does not explain why fewer women enter STEM working fields; rather this gap depends on other aspects, such as culture, past working experiences, or self-efficacy [e.g., 170 ]. Finally, scholars have highlighted the penalization that women face for their positive performance, for instance when they succeed in traditionally male areas [e.g., 178 ]. This penalization is explained by the violation of gender-stereotypic prescriptions [e.g., 179 , 180 ], that is having women well performing in agentic areas, which are typical associated to men. Performance penalization can thus be overcome by clearly conveying communal characteristics and behaviors [ 178 ].

Evidence has been provided on how the involvement of women in boards of directors and decision-making positions affects firms’ performance. Nevertheless, results are mixed, with some studies showing positive effects on financial [ 19 , 181 , 182 ] and corporate social performance [ 99 , 182 , 183 ]. Other studies maintain a negative association [e.g., 18 ], and other again mixed [e.g., 184 ] or non-significant association [e.g., 185 ]. Also with respect to the presence of a female CEO, mixed results emerged so far, with some researches demonstrating a positive effect on firm’s performance [e.g., 96 , 186 ], while other obtaining only a limited evidence of this relationship [e.g., 103 ] or a negative one [e.g., 187 ].

Finally, some studies have investigated whether and how women’s performance affects their hiring [e.g., 101 ] and career progression [e.g., 83 , 160 ]. For instance, academic performance leads to different returns in hiring for women and men. Specifically, high-achieving men are called back significantly more often than high-achieving women, which are penalized when they have a major in mathematics; this result depends on employers’ gendered standards for applicants [e.g., 101 ]. Once appointed, performance ratings are more strongly related to promotions for women than men, and promoted women typically show higher past performance ratings than those of promoted men. This suggesting that women are subject to stricter standards for promotion [e.g., 160 ].

Behavioral aspects related to gender follow two main streams of literature. The first examines female personality and behavior in the workplace, and their alignment with cultural expectations or stereotypes [e.g., 188 ] as well as their impacts on equality. There is a common bias that depicts women as less agentic than males. Certain characteristics, such as those more congruent with male behaviors–e.g., self-promotion [e.g., 189 ], negotiation skills [e.g., 190 ] and general agentic behavior [e.g., 191 ]–, are less accepted in women. However, characteristics such as individualism in women have been found to promote greater gender equality in society [ 192 ]. In addition, behaviors such as display of emotions [e.g., 193 ], which are stereotypically female, work against women’s acceptance in the workplace, requiring women to carefully moderate their behavior to avoid exclusion. A counter-intuitive result is that women and minorities, which are more marginalized in the workplace, tend to be better problem-solvers in innovation competitions due to their different knowledge bases [ 194 ].

The other side of the coin is examined in a parallel literature stream on behavior towards women in the workplace. As a result of biases, prejudices and stereotypes, women may experience adverse behavior from their colleagues, such as incivility and harassment, which undermine their well-being [e.g., 195 , 196 ]. Biases that go beyond gender, such as for overweight people, are also more strongly applied to women [ 197 ].

Organization

The role of women and gender bias in organizations has been studied from different perspectives, which mirror those presented in detail in the following sections. Specifically, most research highlighted the stereotypical view of leaders [e.g., 105 ] and the roles played by women within firms, for instance referring to presence in the board of directors [e.g., 18 , 90 , 91 ], appointment as CEOs [e.g., 16 ], or top executives [e.g., 93 ].

Scholars have investigated antecedents and consequences of the presence of women in these apical roles. On the one side they looked at hiring and career progression [e.g., 83 , 92 , 160 , 168 , 198 ], finding women typically disadvantaged with respect to their male counterparts. On the other side, they studied women’s leadership styles and influence on the firm’s decision-making [e.g., 152 , 154 , 155 , 199 ], with implications for performance [e.g., 18 , 19 , 96 ].

Human capital

Human capital is a transverse topic that touches upon many different aspects of female gender equality. As such, it has the most associations with other topics, starting with education as mentioned above, with career-related topics such as role , decision-making , hiring , career progression , performance , compensation , leadership and organization . Another topic with which there is a close connection is behavior . In general, human capital is approached both from the education standpoint but also from the perspective of social capital.

The behavioral aspect in human capital comprises research related to gender differences for example in cultural and religious beliefs that influence women’s attitudes and perceptions towards STEM subjects [ 142 , 200 – 202 ], towards employment [ 203 ] or towards environmental issues [ 150 , 204 ]. These cultural differences also emerge in the context of globalization which may accelerate gender equality in the workforce [ 205 , 206 ]. Gender differences also appear in behaviors such as motivation [ 207 ], and in negotiation [ 190 ], and have repercussions on women’s decision-making related to their careers. The so-called gender equality paradox sees women in countries with lower gender equality more likely to pursue studies and careers in STEM fields, whereas the gap in STEM enrollment widens as countries achieve greater equality in society [ 171 ].

Career progression is modeled by literature as a choice-process where personal preferences, culture and decision-making affect the chosen path and the outcomes. Some literature highlights how women tend to self-select into different professions than men, often due to stereotypes rather than actual ability to perform in these professions [ 142 , 144 ]. These stereotypes also affect the perceptions of female performance or the amount of human capital required to equal male performance [ 110 , 193 , 208 ], particularly for mothers [ 81 ]. It is therefore often assumed that women are better suited to less visible and less leadership -oriented roles [ 209 ]. Women also express differing preferences towards work-family balance, which affect whether and how they pursue human capital gains [ 210 ], and ultimately their career progression and salary .

On the other hand, men are often unaware of gendered processes and behaviors that they carry forward in their interactions and decision-making [ 211 , 212 ]. Therefore, initiatives aimed at increasing managers’ human capital –by raising awareness of gender disparities in their organizations and engaging them in diversity promotion–are essential steps to counter gender bias and segregation [ 213 ].

Emerging topics: Leadership and entrepreneurship

Among the emerging topics, the most pervasive one is women reaching leadership positions in the workforce and in society. This is still a rare occurrence for two main types of factors, on the one hand, bias and discrimination make it harder for women to access leadership positions [e.g., 214 – 216 ], on the other hand, the competitive nature and high pressure associated with leadership positions, coupled with the lack of women currently represented, reduce women’s desire to achieve them [e.g., 209 , 217 ]. Women are more effective leaders when they have access to education, resources and a diverse environment with representation [e.g., 218 , 219 ].

One sector where there is potential for women to carve out a leadership role is entrepreneurship . Although at the start of the millennium the discourse on entrepreneurship was found to be “discriminatory, gender-biased, ethnocentrically determined and ideologically controlled” [ 220 ], an increasing body of literature is studying how to stimulate female entrepreneurship as an alternative pathway to wealth, leadership and empowerment [e.g., 221 ]. Many barriers exist for women to access entrepreneurship, including the institutional and legal environment, social and cultural factors, access to knowledge and resources, and individual behavior [e.g., 222 , 223 ]. Education has been found to raise women’s entrepreneurial intentions [e.g., 224 ], although this effect is smaller than for men [e.g., 109 ]. In addition, increasing self-efficacy and risk-taking behavior constitute important success factors [e.g., 225 ].

Finally, the topic of sustainability is worth mentioning, as it is the primary objective of the SDGs and is closely associated with societal well-being. As society grapples with the effects of climate change and increasing depletion of natural resources, a narrative has emerged on women and their greater link to the environment [ 226 ]. Studies in developed countries have found some support for women leaders’ attention to sustainability issues in firms [e.g., 227 – 229 ], and smaller resource consumption by women [ 230 ]. At the same time, women will likely be more affected by the consequences of climate change [e.g., 230 ] but often lack the decision-making power to influence local decision-making on resource management and environmental policies [e.g., 231 ].

Research gaps and conclusions

Research on gender equality has advanced rapidly in the past decades, with a steady increase in publications, both in mainstream topics related to women in education and the workforce, and in emerging topics. Through a novel approach combining methods of text mining and social network analysis, we examined a comprehensive body of literature comprising 15,465 papers published between 2000 and mid 2021 on topics related to gender equality. We identified a set of 27 topics addressed by the literature and examined their connections.

At the highest level of abstraction, it is worth noting that papers abound on the identification of issues related to gender inequalities and imbalances in the workforce and in society. Literature has thoroughly examined the (unconscious) biases, barriers, stereotypes, and discriminatory behaviors that women are facing as a result of their gender. Instead, there are much fewer papers that discuss or demonstrate effective solutions to overcome gender bias [e.g., 121 , 143 , 145 , 163 , 194 , 213 , 232 ]. This is partly due to the relative ease in studying the status quo, as opposed to studying changes in the status quo. However, we observed a shift in the more recent years towards solution seeking in this domain, which we strongly encourage future researchers to focus on. In the future, we may focus on collecting and mapping pro-active contributions to gender studies, using additional Natural Language Processing techniques, able to measure the sentiment of scientific papers [ 43 ].

All of the mainstream topics identified in our literature review are closely related, and there is a wealth of insights looking at the intersection between issues such as education and career progression or human capital and role . However, emerging topics are worthy of being furtherly explored. It would be interesting to see more work on the topic of female entrepreneurship , exploring aspects such as education , personality , governance , management and leadership . For instance, how can education support female entrepreneurship? How can self-efficacy and risk-taking behaviors be taught or enhanced? What are the differences in managerial and governance styles of female entrepreneurs? Which personality traits are associated with successful entrepreneurs? Which traits are preferred by venture capitalists and funding bodies?

The emerging topic of sustainability also deserves further attention, as our society struggles with climate change and its consequences. It would be interesting to see more research on the intersection between sustainability and entrepreneurship , looking at how female entrepreneurs are tackling sustainability issues, examining both their business models and their company governance . In addition, scholars are suggested to dig deeper into the relationship between family values and behaviors.

Moreover, it would be relevant to understand how women’s networks (social capital), or the composition and structure of social networks involving both women and men, enable them to increase their remuneration and reach top corporate positions, participate in key decision-making bodies, and have a voice in communities. Furthermore, the achievement of gender equality might significantly change firm networks and ecosystems, with important implications for their performance and survival.

Similarly, research at the nexus of (corporate) governance , career progression , compensation and female empowerment could yield useful insights–for example discussing how enterprises, institutions and countries are managed and the impact for women and other minorities. Are there specific governance structures that favor diversity and inclusion?

Lastly, we foresee an emerging stream of research pertaining how the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic challenged women, especially in the workforce, by making gender biases more evident.

For our analysis, we considered a set of 15,465 articles downloaded from the Scopus database (which is the largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature). As we were interested in reviewing business and economics related gender studies, we only considered those papers published in journals listed in the Academic Journal Guide (AJG) 2018 ranking of the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS). All the journals listed in this ranking are also indexed by Scopus. Therefore, looking at a single database (i.e., Scopus) should not be considered a limitation of our study. However, future research could consider different databases and inclusion criteria.

With our literature review, we offer researchers a comprehensive map of major gender-related research trends over the past twenty-two years. This can serve as a lens to look to the future, contributing to the achievement of SDG5. Researchers may use our study as a starting point to identify key themes addressed in the literature. In addition, our methodological approach–based on the use of the Semantic Brand Score and its webapp–could support scholars interested in reviewing other areas of research.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments.

The computing resources and the related technical support used for this work have been provided by CRESCO/ENEAGRID High Performance Computing infrastructure and its staff. CRESCO/ENEAGRID High Performance Computing infrastructure is funded by ENEA, the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development and by Italian and European research programmes (see http://www.cresco.enea.it/english for information).

Funding Statement

P.B and F.C.: Grant of the Department of Energy, Systems, Territory and Construction of the University of Pisa (DESTEC) for the project “Measuring Gender Bias with Semantic Analysis: The Development of an Assessment Tool and its Application in the European Space Industry. P.B., F.C., A.F.C., P.R.: Grant of the Italian Association of Management Engineering (AiIG), “Misure di sostegno ai soci giovani AiIG” 2020, for the project “Gender Equality Through Data Intelligence (GEDI)”. F.C.: EU project ASSETs+ Project (Alliance for Strategic Skills addressing Emerging Technologies in Defence) EAC/A03/2018 - Erasmus+ programme, Sector Skills Alliances, Lot 3: Sector Skills Alliance for implementing a new strategic approach (Blueprint) to sectoral cooperation on skills G.A. NUMBER: 612678-EPP-1-2019-1-IT-EPPKA2-SSA-B.

Data Availability

- 2020 GEM REPORT

- Inclusion and education

- Monitoring SDG 4

- Recommendations

- 2020 Webpage

- Press Release

- RELATED PUBLICATIONS

- Gender Report

- Youth Report

- Latin America and the Caribbean

- Central and Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia

- Background papers

- Statistical Tables

- 2019 Report

- 2017/8 Report

- 2016 Report

A new generation: 25 years of efforts for gender equality in education

2020 Gender Report

Credit: Johanna de Tessières / HI

KEY MESSAGES

Over the past 25 years, girls’ access to education has dramatically improved, closing a four percentage point gap in enrolment ratios. In addition, girls have reached or overtaken boys in terms of learning outcomes in reading and mathematics.

However, girls, particularly those with intersecting disadvantages in terms of poverty or disability, still face the worst forms of acute exclusion in the world’s poorest countries.

Education is a critical lever for women’s rights. A focus on education, particularly that of girls, can break the cycle of disadvantage between generations, as children tend to acquire more education than their parents. At the same time, the extent to which parental education determines children’s education, while declining slowly, is still high,which calls for interventions to prevent inequality from persisting.

Gender equality in education cannot be achieved by the education sector alone.Residual negative gender norms in society bring gender bias in education, influencing teachers’ attitudes, subject and career choices, and affect women’s opportunities later in life.

Countries need to focus on making schools more inclusive for all students, whatever their background, ability or identity. This requires better sanitation facilities in schools,greater attention to school-related gender-based violence, including online, and policies encouraging pregnant girls to go back to school. The message of inclusion resonates strongly at a time when COVID-19 has exacerbated inequality.

Inside the Report

- Introduction

- Laws and Policies

- Partnerships

Key findings

There has been a generational leap in access to education for girls over the past 25 years.„.

- Since 1995, the number of girls enrolled in primary and secondary school has risen by 180 million.„

- Globally, equal numbers of girls and boys were enrolled in primary and secondary education in 2018, whereas in 1995 around 90 girls were enrolled for every 100 boys; significant increases in Southern Asia, and India in particular, drove this growth.„

- Female enrolment tripled in tertiary education; at the country level, gender disparity at men’s expense exists in 74% of the countries with data.„

- Between 1995 and 2018, the percentage of countries with gender parity in education rose from 56% to 65% in primary, from 45% to 51% in lower secondary and from 13% to 24% in upper secondary education.„

- Among the 56 countries with data for 2000–18, primary completion rates improved faster for girls than boys. In one-third of the 86 countries with 2013–18 data, girls were more likely to complete primary school than boys.

Girls’ learning outcomes are improving faster than boys’, but new gender gaps are developing in digital literacy skills and a majority of illiterate adults are still women.„

- Girls’ advantage over boys in reading widened in more than half of the 38 countries and territories that took part in PISA in both 2000 and 2018. Girls now perform as well as boys in mathematics in over half of countries and do better than boys in one-quarter of countries.„

- Disparity in ICT skills is emerging. Among 10 low- and middle-income countries with detailed data, women are less likely to have used a basic arithmetic formula in a spreadsheet in the 7 poorest countries, while parity exists in the 3 richest countries.„

- The share of women among illiterate youth has decreased since around 2005, especially in Eastern and South-eastern Asia. But the share of illiterate adult women has remained constant for the past 20 years at around 63%. And in 2018, fewer than 80 adult women were literate for every 100 adult men in 12 countries, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

Despite progress, girls continue to face the worst forms of exclusion.„

- Globally, three-quarters of children of primary school age who may never set foot in school are girls.„In 2018, fewer than 90 girls were enrolled for every 100 boys in 7 countries in primary, 14 countries in lower secondary and 23 countries in upper secondary education.„

- Fewer than 80 girls for every 100 boys completed primary in 4 countries, lower secondary in 15 countries and upper secondary in 22 countries.

Gender interacts with other disadvantages to exacerbate exclusion from education.„

- In at least 20 countries, hardly any poor, rural young woman complete upper secondary school.„

- In 24 countries participating in PISA 2018, over 70% of poor boys did not achieve the minimum reading proficiency level.„

- The most disadvantaged women are further left behind in terms of literacy skills. In 59 countries, women aged 15 to 49 from the poorest households are 4 times more likely to be illiterate than those from the richest households.„

- Women with disabilities tend to be particularly disadvantaged. In Mozambique, 49% of men with disabilities can read and write, compared with 17% of women with disabilities.

Some subjects are still male-dominated, which affects equality in work and adult learning opportunities.„

- Globally, the share of females in TVET enrolment declined from 45% in 1995 to 42% in 2018.

- Globally, the percentage of females studying engineering, manufacturing and construction or ICT is below 25% in over two-thirds of countries.„