Chapter 2: The Constitution and Its Origins

The Ratification of the Constitution

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the steps required to ratify the Constitution

- Describe arguments the framers raised in support of a strong national government and counterpoints raised by the Anti-Federalists

On September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia voted to approve the document they had drafted over the course of many months. Some did not support it, but the majority did. Before it could become the law of the land, however, the Constitution faced another hurdle. It had to be ratified by the states.

THE RATIFICATION PROCESS

Article VII, the final article of the Constitution, required that before the Constitution could become law and a new government could form, the document had to be ratified by nine of the thirteen states. Eleven days after the delegates at the Philadelphia convention approved it, copies of the Constitution were sent to each of the states, which were to hold ratifying conventions to either accept or reject it.

This approach to ratification was an unusual one. Since the authority inherent in the Articles of Confederation and the Confederation Congress had rested on the consent of the states, changes to the nation’s government should also have been ratified by the state legislatures. Instead, by calling upon state legislatures to hold ratification conventions to approve the Constitution, the framers avoided asking the legislators to approve a document that would require them to give up a degree of their own power. The men attending the ratification conventions would be delegates elected by their neighbors to represent their interests. They were not being asked to relinquish their power; in fact, they were being asked to place limits upon the power of their state legislators, whom they may not have elected in the first place. Finally, because the new nation was to be a republic in which power was held by the people through their elected representatives, it was considered appropriate to leave the ultimate acceptance or rejection of the Constitution to the nation’s citizens. If convention delegates, who were chosen by popular vote, approved it, then the new government could rightly claim that it ruled with the consent of the people.

The greatest sticking point when it came to ratification, as it had been at the Constitutional Convention itself, was the relative power of the state and federal governments. The framers of the Constitution believed that without the ability to maintain and command an army and navy, impose taxes, and force the states to comply with laws passed by Congress, the young nation would not survive for very long. But many people resisted increasing the powers of the national government at the expense of the states. Virginia’s Patrick Henry, for example, feared that the newly created office of president would place excessive power in the hands of one man. He also disapproved of the federal government’s new ability to tax its citizens. This right, Henry believed, should remain with the states.

Other delegates, such as Edmund Randolph of Virginia, disapproved of the Constitution because it created a new federal judicial system. Their fear was that the federal courts would be too far away from where those who were tried lived. State courts were located closer to the homes of both plaintiffs and defendants, and it was believed that judges and juries in state courts could better understand the actions of those who appeared before them. In response to these fears, the federal government created federal courts in each of the states as well as in Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, and Kentucky, which was part of Virginia. [1]

Perhaps the greatest source of dissatisfaction with the Constitution was that it did not guarantee protection of individual liberties. State governments had given jury trials to residents charged with violating the law and allowed their residents to possess weapons for their protection. Some had practiced religious tolerance as well. The Constitution, however, did not contain reassurances that the federal government would do so. Although it provided for habeas corpus and prohibited both a religious test for holding office and granting noble titles, some citizens feared the loss of their traditional rights and the violation of their liberties. This led many of the Constitution’s opponents to call for a bill of rights and the refusal to ratify the document without one. The lack of a bill of rights was especially problematic in Virginia, as the Virginia Declaration of Rights was the most extensive rights-granting document among the states. The promise that a bill of rights would be drafted for the Constitution persuaded delegates in many states to support ratification. [2]

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Thomas Jefferson on the Bill of Rights

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson carried on a lively correspondence regarding the ratification of the Constitution. In the following excerpt (reproduced as written) from a letter dated March 15, 1789, after the Constitution had been ratified by nine states but before it had been approved by all thirteen, Jefferson reiterates his previously expressed concerns that a bill of rights to protect citizens’ freedoms was necessary and should be added to the Constitution:

“In the arguments in favor of a declaration of rights, . . . I am happy to find that on the whole you are a friend to this amendment. The Declaration of rights is like all other human blessings alloyed with some inconveniences, and not accomplishing fully it’s object. But the good in this instance vastly overweighs the evil. . . . This instrument [the Constitution] forms us into one state as to certain objects, and gives us a legislative & executive body for these objects. It should therefore guard us against their abuses of power. . . . Experience proves the inefficacy of a bill of rights. True. But tho it is not absolutely efficacious under all circumstances, it is of great potency always, and rarely inefficacious. . . . There is a remarkeable difference between the . . . Inconveniences which attend a Declaration of rights, & those which attend the want of it. . . . The inconveniences of the want of a Declaration are permanent, afflicting & irreparable: they are in constant progression from bad to worse.” [3]

What were some of the inconveniences of not having a bill of rights that Jefferson mentioned? Why did he decide in favor of having one?

It was clear how some states would vote. Smaller states, like Delaware, favored the Constitution. Equal representation in the Senate would give them a degree of equality with the larger states, and a strong national government with an army at its command would be better able to defend them than their state militias could. Larger states, however, had significant power to lose. They did not believe they needed the federal government to defend them and disliked the prospect of having to provide tax money to support the new government. Thus, from the very beginning, the supporters of the Constitution feared that New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would refuse to ratify it. That would mean all nine of the remaining states would have to, and Rhode Island, the smallest state, was unlikely to do so. It had not even sent delegates to the convention in Philadelphia. And even if it joined the other states in ratifying the document and the requisite nine votes were cast, the new nation would not be secure without its largest, wealthiest, and most populous states as members of the union.

THE RATIFICATION CAMPAIGN

On the question of ratification, citizens quickly separated into two groups: Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The Federalists supported it. They tended to be among the elite members of society—wealthy and well-educated landowners, businessmen, and former military commanders who believed a strong government would be better for both national defense and economic growth. A national currency, which the federal government had the power to create, would ease business transactions. The ability of the federal government to regulate trade and place tariffs on imports would protect merchants from foreign competition. Furthermore, the power to collect taxes would allow the national government to fund internal improvements like roads, which would also help businessmen. Support for the Federalists was especially strong in New England.

Opponents of ratification were called Anti-Federalists . Anti-Federalists feared the power of the national government and believed state legislatures, with which they had more contact, could better protect their freedoms. Although some Anti-Federalists, like Patrick Henry, were wealthy, most distrusted the elite and believed a strong federal government would favor the rich over those of “the middling sort.” This was certainly the fear of Melancton Smith, a New York merchant and landowner, who believed that power should rest in the hands of small, landowning farmers of average wealth who “are more temperate, of better morals and less ambitious than the great.” [4] Even members of the social elite, like Henry, feared that the centralization of power would lead to the creation of a political aristocracy, to the detriment of state sovereignty and individual liberty.

Related to these concerns were fears that the strong central government Federalists advocated for would levy taxes on farmers and planters, who lacked the hard currency needed to pay them. Many also believed Congress would impose tariffs on foreign imports that would make American agricultural products less welcome in Europe and in European colonies in the western hemisphere. For these reasons, Anti-Federalist sentiment was especially strong in the South.

Some Anti-Federalists also believed that the large federal republic that the Constitution would create could not work as intended. Americans had long believed that virtue was necessary in a nation where people governed themselves (i.e., the ability to put self-interest and petty concerns aside for the good of the larger community). In small republics, similarities among members of the community would naturally lead them to the same positions and make it easier for those in power to understand the needs of their neighbors. In a larger republic, one that encompassed nearly the entire Eastern Seaboard and ran west to the Appalachian Mountains, people would lack such a strong commonality of interests. [5]

Likewise, Anti-Federalists argued, the diversity of religion tolerated by the Constitution would prevent the formation of a political community with shared values and interests. The Constitution contained no provisions for government support of churches or of religious education, and Article VI explicitly forbade the use of religious tests to determine eligibility for public office. This caused many, like Henry Abbot of North Carolina, to fear that government would be placed in the hands of “pagans . . . and Mahometans [Muslims].” [6]

It is difficult to determine how many people were Federalists and how many were Anti-Federalists in 1787. The Federalists won the day, but they may not have been in the majority. First, the Federalist position tended to win support among businessmen, large farmers, and, in the South, plantation owners. These people tended to live along the Eastern Seaboard. In 1787, most of the states were divided into voting districts in a manner that gave more votes to the eastern part of the state than to the western part. [7] Thus, in some states, like Virginia and South Carolina, small farmers who may have favored the Anti-Federalist position were unable to elect as many delegates to state ratification conventions as those who lived in the east. Small settlements may also have lacked the funds to send delegates to the convention. [8]

In all the states, educated men authored pamphlets and published essays and cartoons arguing either for or against ratification. Although many writers supported each position, it is the Federalist essays that are now best known. The arguments these authors put forth, along with explicit guarantees that amendments would be added to protect individual liberties, helped to sway delegates to ratification conventions in many states.

For obvious reasons, smaller, less populous states favored the Constitution and the protection of a strong federal government. Delaware and New Jersey ratified the document within a few months after it was sent to them for approval in 1787. Connecticut ratified it early in 1788. Some of the larger states, such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, also voted in favor of the new government. New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution in the summer of 1788.

Although the Constitution went into effect following ratification by New Hampshire, four states still remained outside the newly formed union. Two were the wealthy, populous states of Virginia and New York. In Virginia, James Madison’s active support and the intercession of George Washington, who wrote letters to the convention, changed the minds of many. Some who had initially opposed the Constitution, such as Edmund Randolph, were persuaded that the creation of a strong union was necessary for the country’s survival and changed their position. Other Virginia delegates were swayed by the promise that a bill of rights similar to the Virginia Declaration of Rights would be added after the Constitution was ratified. On June 25, 1788, Virginia became the tenth state to grant its approval.

The approval of New York was the last major hurdle. Facing considerable opposition to the Constitution in that state, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote a series of essays, beginning in 1787, arguing for a strong federal government and support of the Constitution. Later compiled as The Federalist and now known as The Federalist Papers , these eighty-five essays were originally published in newspapers in New York and other states under the name of Publius, a supporter of the Roman Republic.

The essays addressed a variety of issues that troubled citizens. For example, in Federalist No. 51, attributed to James Madison, the author assured readers they did not need to fear that the national government would grow too powerful. The federal system, in which power was divided between the national and state governments, and the division of authority within the federal government into separate branches would prevent any one part of the government from becoming too strong. Furthermore, tyranny could not arise in a government in which “the legislature necessarily predominates.” Finally, the desire of office holders in each branch of government to exercise the powers given to them, described as “personal motives,” would encourage them to limit any attempt by the other branches to overstep their authority. According to Madison, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Other essays countered different criticisms made of the Constitution and echoed the argument in favor of a strong national government. In Federalist No. 35, for example, Hamilton argued that people’s interests could in fact be represented by men who were not their neighbors. Indeed, Hamilton asked rhetorically, would American citizens best be served by a representative “whose observation does not travel beyond the circle of his neighbors and his acquaintances” or by someone with more extensive knowledge of the world? To those who argued that a merchant and land-owning elite would come to dominate Congress, Hamilton countered that the majority of men currently sitting in New York’s state senate and assembly were landowners of moderate wealth and that artisans usually chose merchants, “their natural patron[s] and friend[s],” to represent them. An aristocracy would not arise, and if it did, its members would have been chosen by lesser men. Similarly, Jay reminded New Yorkers in Federalist No. 2 that union had been the goal of Americans since the time of the Revolution. A desire for union was natural among people of such “similar sentiments” who “were united to each other by the strongest ties,” and the government proposed by the Constitution was the best means of achieving that union.

Objections that an elite group of wealthy and educated bankers, businessmen, and large landowners would come to dominate the nation’s politics were also addressed by Madison in Federalist No. 10. Americans need not fear the power of factions or special interests, he argued, for the republic was too big and the interests of its people too diverse to allow the development of large, powerful political parties. Likewise, elected representatives, who were expected to “possess the most attractive merit,” would protect the government from being controlled by “an unjust and interested [biased in favor of their own interests] majority.”

For those who worried that the president might indeed grow too ambitious or king-like, Hamilton, in Federalist No. 68, provided assurance that placing the leadership of the country in the hands of one person was not dangerous. Electors from each state would select the president. Because these men would be members of a “transient” body called together only for the purpose of choosing the president and would meet in separate deliberations in each state, they would be free of corruption and beyond the influence of the “heats and ferments” of the voters. Indeed, Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 70, instead of being afraid that the president would become a tyrant, Americans should realize that it was easier to control one person than it was to control many. Furthermore, one person could also act with an “energy” that Congress did not possess. Making decisions alone, the president could decide what actions should be taken faster than could Congress, whose deliberations, because of its size, were necessarily slow. At times, the “decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch” of the chief executive might be necessary.

LINK TO LEARNING

The Library of Congress has The Federalist Papers on their website. The Anti-Federalists also produced a body of writings, less extensive than The Federalists Papers , which argued against the ratification of the Constitution. However, these were not written by one small group of men as The Federalist Papers had been. A collection of the writings that are unofficially called The Anti-Federalist Papers is also available online.

The arguments of the Federalists were persuasive, but whether they actually succeeded in changing the minds of New Yorkers is unclear. Once Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788, New York realized that it had little choice but to do so as well. If it did not ratify the Constitution, it would be the last large state that had not joined the union. Thus, on July 26, 1788, the majority of delegates to New York’s ratification convention voted to accept the Constitution. A year later, North Carolina became the twelfth state to approve. Alone and realizing it could not hope to survive on its own, Rhode Island became the last state to ratify, nearly two years after New York had done so.

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Term Limits

One of the objections raised to the Constitution’s new government was that it did not set term limits for members of Congress or the president. Those who opposed a strong central government argued that this failure could allow a handful of powerful men to gain control of the nation and rule it for as long as they wished. Although the framers did not anticipate the idea of career politicians, those who supported the Constitution argued that reelecting the president and reappointing senators by state legislatures would create a body of experienced men who could better guide the country through crises. A president who did not prove to be a good leader would be voted out of office instead of being reelected. In fact, presidents long followed George Washington’s example and limited themselves to two terms. Only in 1951, after Franklin Roosevelt had been elected four times, was the Twenty-Second Amendment passed to restrict the presidency to two terms.

Are term limits a good idea? Should they have originally been included in the Constitution? Why or why not? Are there times when term limits might not be good?

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 2.4 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary , and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Pauline Maier. 2010. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon & Schuster, 464. ↵

- Maier, Ratification, 431. ↵

- Letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, March 15, 1789, https://www.gwu.edu/~ffcp/exhibit/p7/p7_1text.html . ↵

- Isaac Krannick. 1999. “The Great National Discussion: The Discourse of Politics in 1787.” In What Did the Constitution Mean to Early Americans? ed. Edward Countryman. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 52. ↵

- Krannick, Great National Discussion, 42-43. ↵

- Krannick, Great National Discussion, 42. ↵

- Evelyn C. Fink and William H. Riker. 1989. "The Strategy of Ratification." In The Federalist Papers and the New Institutionalism, eds. Bernard Grofman and Donald Wittman. New York: Agathon, 229. ↵

- Fink and Riker, Strategy of Ratification, 221. ↵

those who supported ratification of the Constitution

those who did not support ratification of the Constitution

a collection of eighty-five essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in support of ratification of the Constitution

American Government (2e - Second Edition) Copyright © 2019 by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

- Main Reading Room

Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History

Introduction.

- Federalist Nos. 1-10

- Federalist Nos. 11-20

- Federalist Nos. 21-30

- Federalist Nos. 31-40

- Federalist Nos. 41-50

- Federalist Nos. 51-60

- Federalist Nos. 61-70

- Federalist Nos. 71-80

- Federalist Nos. 81-85

- Related Digital Resources

- External Websites

- Print Resources

History, Humanities & Social Sciences : Ask a Librarian

Have a question? Need assistance? Use our online form to ask a librarian for help.

Chat with a librarian , Monday through Friday, 12-4pm Eastern Time (except Federal Holidays).

Authors: Ken Drexler, Reference Specialist, Researcher and Reference Services Division

Robert Brammer, Legal Information Specialist, Law Library of Congress

Editor: Barbara Bavis, Bibliographic and Research Instruction Librarian, Law Library of Congress

Created: May 3, 2019

Last Updated: August 13, 2019

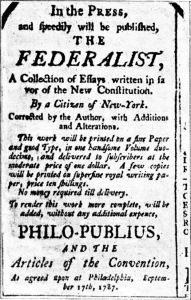

The Federalist Papers were a series of eighty-five essays urging the citizens of New York to ratify the new United States Constitution. Written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, the essays originally appeared anonymously in New York newspapers in 1787 and 1788 under the pen name "Publius." The Federalist Papers are considered one of the most important sources for interpreting and understanding the original intent of the Constitution.

- The Federalist Papers - Full Text This web-friendly presentation of the original text of the Federalist Papers (also known as The Federalist ) was obtained from the e-text archives of Project Gutenberg.

Title Page of "The Federalist" (N.Y. John Tiebout, 1799). 1799. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

Publius (pseudonym for james madison). “the federalist. no. x” in the new york daily advertiser. page 2. (november 22, 1787). library of congress serial and government publications division.

The federalist : a collection of essays, written in favour of the new Constitution, as agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. . Library of Congress Rare Book & Special Collections Division.

- Next: Full Text of The Federalist Papers >>

- Last Updated: Sep 10, 2024 7:02 AM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Federalist papers summary

Federalist papers , formally The Federalist , Eighty-five essays on the proposed Constitution of the United States and the nature of republican government, published in 1787–88 by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay in an effort to persuade voters of New York state to support ratification. Most of the essays first appeared serially in New York newspapers; they were reprinted in other states and then published as a book in 1788. A few of the essays were issued separately later. All were signed “Publius.” They presented a masterly exposition of the federal system and the means of attaining the ideals of justice, general welfare, and the rights of individuals.

The Ratification of the Constitution

OpenStax and Lumen Learning

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the steps required to ratify the Constitution

- Describe arguments the framers raised in support of a strong national government and counterpoints raised by the Anti-Federalists

On September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia voted to approve the document they had drafted over the course of many months. Some did not support it, but the majority did. Before it could become the law of the land, however, the Constitution faced another hurdle. It had to be ratified by the states.

THE RATIFICATION PROCESS

Article VII, the final article of the Constitution, required that before the Constitution could become law and a new government could form, the document had to be ratified by nine of the thirteen states. Eleven days after the delegates at the Philadelphia convention approved it, copies of the Constitution were sent to each of the states, which were to hold ratifying conventions to either accept or reject it.

This approach to ratification was an unusual one. Since the authority inherent in the Articles of Confederation and the Confederation Congress had rested on the consent of the states, changes to the nation’s government should also have been ratified by the state legislatures. Instead, by calling upon state legislatures to hold ratification conventions to approve the Constitution, the framers avoided asking the legislators to approve a document that would require them to give up a degree of their own power. The men attending the ratification conventions would be delegates elected by their neighbors to represent their interests. They were not being asked to relinquish their power; in fact, they were being asked to place limits upon the power of their state legislators, whom they may not have elected in the first place. Finally, because the new nation was to be a republic in which power was held by the people through their elected representatives, it was considered appropriate to leave the ultimate acceptance or rejection of the Constitution to the nation’s citizens. If convention delegates, who were chosen by popular vote, approved it, then the new government could rightly claim that it ruled with the consent of the people.

The greatest sticking point when it came to ratification, as it had been at the Constitutional Convention itself, was the relative power of the state and federal governments. The framers of the Constitution believed that without the ability to maintain and command an army and navy, impose taxes, and force the states to comply with laws passed by Congress, the young nation would not survive for very long. But many people resisted increasing the powers of the national government at the expense of the states. Virginia’s Patrick Henry, for example, feared that the newly created office of president would place excessive power in the hands of one man. He also disapproved of the federal government’s new ability to tax its citizens. This right, Henry believed, should remain with the states.

Other delegates, such as Edmund Randolph of Virginia, disapproved of the Constitution because it created a new federal judicial system. Their fear was that the federal courts would be too far away from where those who were tried lived. State courts were located closer to the homes of both plaintiffs and defendants, and it was believed that judges and juries in state courts could better understand the actions of those who appeared before them. In response to these fears, the federal government created federal courts in each of the states as well as in Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, and Kentucky, which was part of Virginia. [1]

Perhaps the greatest source of dissatisfaction with the Constitution was that it did not guarantee protection of individual liberties. State governments had given jury trials to residents charged with violating the law and allowed their residents to possess weapons for their protection. Some had practiced religious tolerance as well. The Constitution, however, did not contain reassurances that the federal government would do so. Although it provided for habeas corpus and prohibited both a religious test for holding office and granting noble titles, some citizens feared the loss of their traditional rights and the violation of their liberties. This led many of the Constitution’s opponents to call for a bill of rights and the refusal to ratify the document without one. The lack of a bill of rights was especially problematic in Virginia, as the Virginia Declaration of Rights was the most extensive rights-granting document among the states. The promise that a bill of rights would be drafted for the Constitution persuaded delegates in many states to support ratification. [2]

INSIDER PERSPECTIVE

Thomas Jefferson on the Bill of Rights

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson carried on a lively correspondence regarding the ratification of the Constitution. In the following excerpt (reproduced as written) from a letter dated March 15, 1789, after the Constitution had been ratified by nine states but before it had been approved by all thirteen, Jefferson reiterates his previously expressed concerns that a bill of rights to protect citizens’ freedoms was necessary and should be added to the Constitution:

“In the arguments in favor of a declaration of rights, . . . I am happy to find that on the whole you are a friend to this amendment. The Declaration of rights is like all other human blessings alloyed with some inconveniences, and not accomplishing fully it’s object. But the good in this instance vastly overweighs the evil. . . . This instrument [the Constitution] forms us into one state as to certain objects, and gives us a legislative & executive body for these objects. It should therefore guard us against their abuses of power. . . . Experience proves the inefficacy of a bill of rights. True. But tho it is not absolutely efficacious under all circumstances, it is of great potency always, and rarely inefficacious. . . . There is a remarkeable difference between the . . . Inconveniences which attend a Declaration of rights, & those which attend the want of it. . . . The inconveniences of the want of a Declaration are permanent, afflicting & irreparable: they are in constant progression from bad to worse.” [3]

What were some of the inconveniences of not having a bill of rights that Jefferson mentioned? Why did he decide in favor of having one?

It was clear how some states would vote. Smaller states, like Delaware, favored the Constitution. Equal representation in the Senate would give them a degree of equality with the larger states, and a strong national government with an army at its command would be better able to defend them than their state militias could. Larger states, however, had significant power to lose. They did not believe they needed the federal government to defend them and disliked the prospect of having to provide tax money to support the new government. Thus, from the very beginning, the supporters of the Constitution feared that New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would refuse to ratify it. That would mean all nine of the remaining states would have to, and Rhode Island, the smallest state, was unlikely to do so. It had not even sent delegates to the convention in Philadelphia. And even if it joined the other states in ratifying the document and the requisite nine votes were cast, the new nation would not be secure without its largest, wealthiest, and most populous states as members of the union.

THE RATIFICATION CAMPAIGN

On the question of ratification, citizens quickly separated into two groups: Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The Federalists supported it. They tended to be among the elite members of society—wealthy and well-educated landowners, businessmen, and former military commanders who believed a strong government would be better for both national defense and economic growth. A national currency, which the federal government had the power to create, would ease business transactions. The ability of the federal government to regulate trade and place tariffs on imports would protect merchants from foreign competition. Furthermore, the power to collect taxes would allow the national government to fund internal improvements like roads, which would also help businessmen. Support for the Federalists was especially strong in New England.

Opponents of ratification were called Anti-Federalists . Anti-Federalists feared the power of the national government and believed state legislatures, with which they had more contact, could better protect their freedoms. Although some Anti-Federalists, like Patrick Henry, were wealthy, most distrusted the elite and believed a strong federal government would favor the rich over those of “the middling sort.” This was certainly the fear of Melancton Smith, a New York merchant and landowner, who believed that power should rest in the hands of small, landowning farmers of average wealth who “are more temperate, of better morals and less ambitious than the great.” [4] Even members of the social elite, like Henry, feared that the centralization of power would lead to the creation of a political aristocracy, to the detriment of state sovereignty and individual liberty.

Related to these concerns were fears that the strong central government Federalists advocated for would levy taxes on farmers and planters, who lacked the hard currency needed to pay them. Many also believed Congress would impose tariffs on foreign imports that would make American agricultural products less welcome in Europe and in European colonies in the western hemisphere. For these reasons, Anti-Federalist sentiment was especially strong in the South.

Some Anti-Federalists also believed that the large federal republic that the Constitution would create could not work as intended. Americans had long believed that virtue was necessary in a nation where people governed themselves (i.e., the ability to put self-interest and petty concerns aside for the good of the larger community). In small republics, similarities among members of the community would naturally lead them to the same positions and make it easier for those in power to understand the needs of their neighbors. In a larger republic, one that encompassed nearly the entire Eastern Seaboard and ran west to the Appalachian Mountains, people would lack such a strong commonality of interests. [5]

Likewise, Anti-Federalists argued, the diversity of religion tolerated by the Constitution would prevent the formation of a political community with shared values and interests. The Constitution contained no provisions for government support of churches or of religious education, and Article VI explicitly forbade the use of religious tests to determine eligibility for public office. This caused many, like Henry Abbot of North Carolina, to fear that government would be placed in the hands of “pagans . . . and Mahometans [Muslims].” [6]

It is difficult to determine how many people were Federalists and how many were Anti-Federalists in 1787. The Federalists won the day, but they may not have been in the majority. First, the Federalist position tended to win support among businessmen, large farmers, and, in the South, plantation owners. These people tended to live along the Eastern Seaboard. In 1787, most of the states were divided into voting districts in a manner that gave more votes to the eastern part of the state than to the western part. [7] Thus, in some states, like Virginia and South Carolina, small farmers who may have favored the Anti-Federalist position were unable to elect as many delegates to state ratification conventions as those who lived in the east. Small settlements may also have lacked the funds to send delegates to the convention. [8]

In all the states, educated men authored pamphlets and published essays and cartoons arguing either for or against ratification. Although many writers supported each position, it is the Federalist essays that are now best known. The arguments these authors put forth, along with explicit guarantees that amendments would be added to protect individual liberties, helped to sway delegates to ratification conventions in many states.

For obvious reasons, smaller, less populous states favored the Constitution and the protection of a strong federal government. Delaware and New Jersey ratified the document within a few months after it was sent to them for approval in 1787. Connecticut ratified it early in 1788. Some of the larger states, such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, also voted in favor of the new government. New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution in the summer of 1788.

Although the Constitution went into effect following ratification by New Hampshire, four states still remained outside the newly formed union. Two were the wealthy, populous states of Virginia and New York. In Virginia, James Madison’s active support and the intercession of George Washington, who wrote letters to the convention, changed the minds of many. Some who had initially opposed the Constitution, such as Edmund Randolph, were persuaded that the creation of a strong union was necessary for the country’s survival and changed their positions. Other Virginia delegates were swayed by the promise that a bill of rights similar to the Virginia Declaration of Rights would be added after the Constitution was ratified. On June 25, 1788, Virginia became the tenth state to grant its approval.

The approval of New York was the last major hurdle. Facing considerable opposition to the Constitution in that state, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote a series of essays, beginning in 1787, arguing for a strong federal government and support of the Constitution. Later compiled as The Federalist and now known as The Federalist Papers , these eighty-five essays were originally published in newspapers in New York and other states under the name of Publius, a supporter of the Roman Republic.

The essays addressed a variety of issues that troubled citizens. For example, in Federalist No. 51, attributed to James Madison, the author assured readers they did not need to fear that the national government would grow too powerful. The federal system, in which power was divided between the national and state governments, and the division of authority within the federal government into separate branches would prevent any one part of the government from becoming too strong. Furthermore, tyranny could not arise in a government in which “the legislature necessarily predominates.” Finally, the desire of office holders in each branch of government to exercise the powers given to them, described as “personal motives,” would encourage them to limit any attempt by the other branches to overstep their authority. According to Madison, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Other essays countered different criticisms made of the Constitution and echoed the argument in favor of a strong national government. In Federalist No. 35, for example, Hamilton argued that people’s interests could in fact be represented by men who were not their neighbors. Indeed, Hamilton asked rhetorically, would American citizens best be served by a representative “whose observation does not travel beyond the circle of his neighbors and his acquaintances” or by someone with more extensive knowledge of the world? To those who argued that a merchant and land-owning elite would come to dominate Congress, Hamilton countered that the majority of men currently sitting in New York’s state senate and assembly were landowners of moderate wealth and that artisans usually chose merchants, “their natural patron[s] and friend[s],” to represent them. An aristocracy would not arise, and if it did, its members would have been chosen by lesser men. Similarly, Jay reminded New Yorkers in Federalist No. 2 that union had been the goal of Americans since the time of the Revolution. A desire for union was natural among people of such “similar sentiments” who “were united to each other by the strongest ties,” and the government proposed by the Constitution was the best means of achieving that union.

Objections that an elite group of wealthy and educated bankers, businessmen, and large landowners would come to dominate the nation’s politics were also addressed by Madison in Federalist No. 10. Americans need not fear the power of factions or special interests, he argued, for the republic was too big and the interests of its people too diverse to allow the development of large, powerful political parties. Likewise, elected representatives, who were expected to “possess the most attractive merit,” would protect the government from being controlled by “an unjust and interested [biased in favor of their own interests] majority.”

For those who worried that the president might indeed grow too ambitious or king-like, Hamilton, in Federalist No. 68, provided assurance that placing the leadership of the country in the hands of one person was not dangerous. Electors from each state would select the president. Because these men would be members of a “transient” body called together only for the purpose of choosing the president and would meet in separate deliberations in each state, they would be free of corruption and beyond the influence of the “heats and ferments” of the voters. Indeed, Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 70, instead of being afraid that the president would become a tyrant, Americans should realize that it was easier to control one person than it was to control many. Furthermore, one person could also act with an “energy” that Congress did not possess. Making decisions alone, the president could decide what actions should be taken faster than could Congress, whose deliberations, because of its size, were necessarily slow. At times, the “decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch” of the chief executive might be necessary.

LINK TO LEARNING

The Library of Congress has The Federalist Papers on their website. The Anti-Federalists also produced a body of writings, less extensive than The Federalist Papers , which argued against the ratification of the Constitution. However, these were not written by one small group of men as The Federalist Papers had been. A collection of the writings that are unofficially called The Anti-Federalist Papers is also available online.

The arguments of the Federalists were persuasive, but whether they actually succeeded in changing the minds of New Yorkers is unclear. Once Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788, New York realized that it had little choice but to do so as well. If it did not ratify the Constitution, it would be the last large state that had not joined the union. Thus, on July 26, 1788, the majority of delegates to New York’s ratification convention voted to accept the Constitution. A year later, North Carolina became the twelfth state to approve. Alone and realizing it could not hope to survive on its own, Rhode Island became the last state to ratify, nearly two years after New York had done so.

FINDING A MIDDLE GROUND

Term Limits

One of the objections raised to the Constitution’s new government was that it did not set term limits for members of Congress or the president. Those who opposed a strong central government argued that this failure could allow a handful of powerful men to gain control of the nation and rule it for as long as they wished. Although the framers did not anticipate the idea of career politicians, those who supported the Constitution argued that reelecting the president and reappointing senators by state legislatures would create a body of experienced men who could better guide the country through crises. A president who did not prove to be a good leader would be voted out of office instead of being reelected. In fact, presidents long followed George Washington’s example and limited themselves to two terms. Only in 1951, after Franklin Roosevelt had been elected four times, was the Twenty-Second Amendment passed to restrict the presidency to two terms.

Are term limits a good idea? Should they have originally been included in the Constitution? Why or why not? Are there times when term limits might not be good?

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 2.4 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary , and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Pauline Maier. 2010. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon & Schuster, 464. ↵

- Maier, Ratification, 431. ↵

- Letter from Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, March 15, 1789, https://www.gwu.edu/~ffcp/exhibit/p7/p7_1text.html . ↵

- Isaac Krannick. 1999. “The Great National Discussion: The Discourse of Politics in 1787.” In What Did the Constitution Mean to Early Americans? ed. Edward Countryman. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 52. ↵

- Krannick, Great National Discussion, 42-43. ↵

- Krannick, Great National Discussion, 42. ↵

- Evelyn C. Fink and William H. Riker. 1989. "The Strategy of Ratification." In The Federalist Papers and the New Institutionalism, eds. Bernard Grofman and Donald Wittman. New York: Agathon, 229. ↵

- Fink and Riker, Strategy of Ratification, 221. ↵

those who supported ratification of the Constitution

those who did not support ratification of the Constitution

a collection of eighty-five essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in support of ratification of the Constitution

The Ratification of the Constitution Copyright © 2022 by OpenStax and Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The Cambridge Companion to The Federalist

The eighty-five Federalist essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison as 'Publius' to support the ratification of the Constitution in 1787–88 are regarded as the preeminent American contribution to Western political theory. Recently, there have been major developments in scholarship on the Revolutionary and Founding era as well as increased public interest in constitutional matters that make this a propitious moment to reflect on the contributions and complexity of The Federalist. This volume of specially commissioned essays covers the broad scope of 'Publius' work, including historical, political, philosophical, juridical, and moral dimensions. In so doing, they bring the design and arguments of the text into focus for twenty-first century scholars, students, and citizens and show how these diverse treatments of The Federalist are associated with an array of substantive political and constitutional perspectives in our own time.

Library electronic resources outage May 29th and 30th

Between 9:00 PM EST on Saturday, May 29th and 9:00 PM EST on Sunday, May 30th users will not be able to access resources through the Law Library’s Catalog, the Law Library’s Database List, the Law Library’s Frequently Used Databases List, or the Law Library’s Research Guides. Users can still access databases that require an individual user account (ex. Westlaw, LexisNexis, and Bloomberg Law), or databases listed on the Main Library’s A-Z Database List.

- Georgetown Law Library

Constitutional Law and History Research Guide

- Historical Documents & Resources

- Introduction/Key Resources

- Primary Law

- Treatises and Other Secondary Sources

- State Constitutional Law

On this page

Proceedings of the federal convention of 1787, anti-federalist arguments, federalist arguments, bill of rights and amendment history, key to icons.

- Georgetown only

- On Bloomberg

- More Info (hover)

- Preeminent Treatise

Introduction

The events and discussions leading to the adoption of the Constitution and its amendments are recorded in a variety of reports, journals, and other documents. These materials continue to be important resources as courts attempt to apply the terms of an 18th century document to evolving modern circumstances. The following proceedings and documents can provide valuable historical background on the U.S. Constitution.

There is no official record of the proceedings regarding the Constitutional Convention of 1787. James Madison kept the journal of the proceedings, but it included only procedural information. Several editions of this journal are available online and in print at the library:

- The Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787: Which framed the Constitution of the United States of America / reported by James Madison (1920 ed.)

A more modern source to consult is Max Farrand's T he Records of the Federal Constitution of 1787 . Farrand's Records remains the single best source for discussions of the Constitutional Convention as it gathers together the documentary records of the Constitutional Convention and the materials necessary to study the workings of the Constitutional Convention. Published in 1911, the documentary records of the Constitutional Convention were compiled into three volumes containing the notes by major participants and the texts of various alternative plans presented. The three volumes also includes notes and letters by many other participants, as well as the various constitutional plans proposed during the convention.

Full text access to the 1911 edition is available online at the following sources:

- HeinOnline's World Constitutions Illustrated

- A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875

Subsequent editions:

- The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (rev. 1937) In 1937, Farrand published a revised edition, which included a fourth volume.

- The Records of the Federal convention of 1787 (rev. 1987) In 1987, a supplement to Farrand's Records was compiled and edited by James Hutson.

For more on the Anti-Federalists, who made the case against ratification, as well as debates on the ratification of the Constitution, see:

- The Complete Anti-Federalist by Herbert J. Storing The most comprehensive collection of Anti-Federalist writings.

- Birth of the Bill of Rights : Encyclopedia of the Antifederalists by Jon L. Wakelyn Includes biographies of 140 prominent Anti-Federalists, as well as major speeches and writings arranged by state.

- Debates in the Several State Conventions, on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, as Recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia, in 1787 by Jonathan Elliot A five-volume collection compiled by Jonathan Elliot remains the best source for materials about the national government's transitional period between the closing of the Constitutional Convention in September 1787 and the opening of the First Federal Congress in March 1789

- The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (UVA Press, Digital Edition) This work is generally considered more accurate and authoritative than Elliot's Debates. This landmark work in historical and legal scholarship draws upon thousands of sources to trace the Constitution’s progress through each of the thirteen states’ conventions. The digital edition allows users to search the complete contents by date, title, author, recipient, or state affiliation and preserves the copious annotations of the print edition.

The Federalist Papers (also known as "The Federalist") were a series of eighty-five essays urging the citizens of New York to ratify the new United States Constitution written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay.The Federalist Papers are considered one of the most important sources for interpreting and understanding the original intent of the Constitution.

These arguments made for ratification of the Constitution were published in collected form as The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution (1788) , which is available from the following sources:

- The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution (HeinOnline) Essays written during the early development of American Constitutional History. Includes "The Federalist" and other essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. Also available in print.

- The Federalist and Other Constitutional Papers In addition to The Federalist, this book includes information on other essays and discussions from between the time when the work of the Federal Convention was announced and the time when the Constitution was adopted by the States.

- The Federalist Papers (Yale's Avalon Project) The Avalon Project provides primary source materials relevant to the fields of law, history, economics, politics, diplomacy, and government.

- The Federalist Papers (Library of Congress) The original text of the Federalist Papers obtained from the e-text archives of Project Gutenberg.

The Amendments Project

- The Amendments Project The Amendments Project (TAP) is a searchable archive of the full text of nearly every amendment to the U.S. Constitution proposed in Congress between 1789 and 2022 (more than 11,000 proposals).Only twenty-seven amendments to the U.S. Constitution have ever been ratified; the Amendments Project is, then, an archive of failures.

Since ratification in 1788, thousands of amendments have been proposed, though the Constitution has been amended only twenty-seven times. As outlined in Article V, amendments to the Constitution are proposed by Congress and presented to the states for ratification. These amendments are discussed in length in the following sources:

- Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues, 1789-2010 by John R. Vile Provides a comprehensive analysis of the United States' constitutional amendments. With over 400 short articles, this encyclopedia tells the whole story of constitutional amendments: the rigorous ratification process, the significance of the 27 amendments, and the thousands that didn't pass.

- The Founders' Constitution by Philip B. Kurland & Ralph Lerner Covers the first twelve amendments as well as the original seven articles.

- The Complete Bill of Rights : the Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins by Neil H. Cogan Provides excerpts from source documents arranged by amendment as well as texts of proposals in Congress and from the state conventions, and discussion of the amendments in Congress, conventions, newspapers and letters.

- The Reconstruction Amendments' Debates : the Legislative History and Contemporary Debates in Congress on the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments by Alfred Avins The Reconstruction amendments such as the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses were proposed by Congress and the deliberations of the House and Senate debates for these amendments were reprinted in this source. It also contains guide explaining the context of each document.

- Constitutional Amendments, 1789 to the Present by Kris E. Palmer Addresses each amendment in order with a length article on the original context and subsequent interpretation.

- << Previous: Introduction/Key Resources

- Next: Primary Law >>

- © Georgetown University Law Library. These guides may be used for educational purposes, as long as proper credit is given. These guides may not be sold. Any comments, suggestions, or requests to republish or adapt a guide should be submitted using the Research Guides Comments form . Proper credit includes the statement: Written by, or adapted from, Georgetown Law Library (current as of .....).

- Last Updated: Sep 13, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/constitutionallaw

2.4 The Ratification of the Constitution

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the steps required to ratify the Constitution

- Describe arguments the framers raised in support of a strong national government and counterpoints raised by the Anti-Federalists

On September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia voted to approve the document they had drafted over the course of many months. Some did not support it, but the majority did. Before it could become the law of the land, however, the Constitution faced another hurdle. It had to be ratified by the states.

THE RATIFICATION PROCESS

Article VII, the final article of the Constitution, required that before the Constitution could become law and a new government could form, the document had to be ratified by nine of the thirteen states. Eleven days after the delegates at the Philadelphia convention approved it, copies of the Constitution were sent to each of the states, which were to hold ratifying conventions to either accept or reject it.

This approach to ratification was an unusual one. Since the authority inherent in the Articles of Confederation and the Confederation Congress had rested on the consent of the states, changes to the nation’s government should also have been ratified by the state legislatures. Instead, by calling upon state legislatures to hold ratification conventions to approve the Constitution, the framers avoided asking the legislators to approve a document that would require them to give up a degree of their own power. The men attending the ratification conventions would be delegates elected by their neighbors to represent their interests. They were not being asked to relinquish their power; in fact, they were being asked to place limits upon the power of their state legislators, whom they may not have elected in the first place. Finally, because the new nation was to be a republic in which power was held by the people through their elected representatives, it was considered appropriate to leave the ultimate acceptance or rejection of the Constitution to the nation’s citizens. If convention delegates, who were chosen by popular vote, approved it, then the new government could rightly claim that it ruled with the consent of the people.

The greatest sticking point when it came to ratification, as it had been at the Constitutional Convention itself, was the relative power of the state and federal governments. The framers of the Constitution believed that without the ability to maintain and command an army and navy, impose taxes, and force the states to comply with laws passed by Congress, the young nation would not survive for very long. But many people resisted increasing the powers of the national government at the expense of the states. Virginia’s Patrick Henry , for example, feared that the newly created office of president would place excessive power in the hands of one man. He also disapproved of the federal government’s new ability to tax its citizens. This right, Henry believed, should remain with the states.

Other delegates, such as Edmund Randolph of Virginia, disapproved of the Constitution because it created a new federal judicial system. Their fear was that the federal courts would be too far away from where those who were tried lived. State courts were located closer to the homes of both plaintiffs and defendants, and it was believed that judges and juries in state courts could better understand the actions of those who appeared before them. In response to these fears, the federal government created federal courts in each of the states as well as in Maine, which was then part of Massachusetts, and Kentucky, which was part of Virginia. 11

Perhaps the greatest source of dissatisfaction with the Constitution was that it did not guarantee protection of individual liberties. State governments had given jury trials to residents charged with violating the law and allowed their residents to possess weapons for their protection. Some had practiced religious tolerance as well. The Constitution, however, did not contain reassurances that the federal government would do so. Although it provided for habeas corpus and prohibited both a religious test for holding office and granting noble titles, some citizens feared the loss of their traditional rights and the violation of their liberties. This led many of the Constitution’s opponents to call for a bill of rights and the refusal to ratify the document without one. The lack of a bill of rights was especially problematic in Virginia, as the Virginia Declaration of Rights was the most extensive rights-granting document among the states. The promise that a bill of rights would be drafted for the Constitution persuaded delegates in many states to support ratification. 12

Insider Perspective

Thomas jefferson on the bill of rights.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson carried on a lively correspondence regarding the ratification of the Constitution. In the following excerpt (reproduced as written) from a letter dated March 15, 1789, after the Constitution had been ratified by nine states but before it had been approved by all thirteen, Jefferson reiterates his previously expressed concerns that a bill of rights to protect citizens’ freedoms was necessary and should be added to the Constitution:

“In the arguments in favor of a declaration of rights, . . . I am happy to find that on the whole you are a friend to this amendment. The Declaration of rights is like all other human blessings alloyed with some inconveniences, and not accomplishing fully it’s object. But the good in this instance vastly overweighs the evil. . . . This instrument [the Constitution] forms us into one state as to certain objects, and gives us a legislative & executive body for these objects. It should therefore guard us against their abuses of power. . . . Experience proves the inefficacy of a bill of rights. True. But tho it is not absolutely efficacious under all circumstances, it is of great potency always, and rarely inefficacious. . . . There is a remarkeable difference between the . . . Inconveniences which attend a Declaration of rights, & those which attend the want of it. . . . The inconveniences of the want of a Declaration are permanent, afflicting & irreparable: they are in constant progression from bad to worse.” 13

What were some of the inconveniences of not having a bill of rights that Jefferson mentioned? Why did he decide in favor of having one?

It was clear how some states would vote. Smaller states, like Delaware, favored the Constitution. Equal representation in the Senate would give them a degree of equality with the larger states, and a strong national government with an army at its command would be better able to defend them than their state militias could. Larger states, however, had significant power to lose. They did not believe they needed the federal government to defend them and disliked the prospect of having to provide tax money to support the new government. Thus, from the very beginning, the supporters of the Constitution feared that New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would refuse to ratify it. That would mean all nine of the remaining states would have to, and Rhode Island, the smallest state, was unlikely to do so. It had not even sent delegates to the convention in Philadelphia. And even if it joined the other states in ratifying the document and the requisite nine votes were cast, the new nation would not be secure without its largest, wealthiest, and most populous states as members of the union.

THE RATIFICATION CAMPAIGN

On the question of ratification, citizens quickly separated into two groups: Federalists and Anti-Federalists. The Federalists supported it. They tended to be among the elite members of society—wealthy and well-educated landowners, businessmen, and former military commanders who believed a strong government would be better for both national defense and economic growth. A national currency, which the federal government had the power to create, would ease business transactions. The ability of the federal government to regulate trade and place tariffs on imports would protect merchants from foreign competition. Furthermore, the power to collect taxes would allow the national government to fund internal improvements like roads, which would also help businessmen. Support for the Federalists was especially strong in New England.

Opponents of ratification were called Anti-Federalists . Anti-Federalists feared the power of the national government and believed state legislatures, with which they had more contact, could better protect their freedoms. Although some Anti-Federalists, like Patrick Henry , were wealthy, most distrusted the elite and believed a strong federal government would favor the rich over those of “the middling sort.” This was certainly the fear of Melancton Smith , a New York merchant and landowner, who believed that power should rest in the hands of small, landowning farmers of average wealth who “are more temperate, of better morals and less ambitious than the great.” 14 Even members of the social elite, like Henry, feared that the centralization of power would lead to the creation of a political aristocracy, to the detriment of state sovereignty and individual liberty.

Related to these concerns were fears that the strong central government Federalists advocated for would levy taxes on farmers and planters, who lacked the hard currency needed to pay them. Many also believed Congress would impose tariffs on foreign imports that would make American agricultural products less welcome in Europe and in European colonies in the western hemisphere. For these reasons, Anti-Federalist sentiment was especially strong in the South.

Some Anti-Federalists also believed that the large federal republic that the Constitution would create could not work as intended. Americans had long believed that virtue was necessary in a nation where people governed themselves (i.e., the ability to put self-interest and petty concerns aside for the good of the larger community). In small republics, similarities among members of the community would naturally lead them to the same positions and make it easier for those in power to understand the needs of their neighbors. In a larger republic, one that encompassed nearly the entire Eastern Seaboard and ran west to the Appalachian Mountains, people would lack such a strong commonality of interests. 15

Likewise, Anti-Federalists argued, the diversity of religion tolerated by the Constitution would prevent the formation of a political community with shared values and interests. The Constitution contained no provisions for government support of churches or of religious education, and Article VI explicitly forbade the use of religious tests to determine eligibility for public office. This caused many, like Henry Abbot of North Carolina, to fear that government would be placed in the hands of “pagans . . . and Mahometans [Muslims].” 16

It is difficult to determine how many people were Federalists and how many were Anti-Federalists in 1787. The Federalists won the day, but they may not have been in the majority. First, the Federalist position tended to win support among businessmen, large farmers, and, in the South, plantation owners. These people tended to live along the Eastern Seaboard. In 1787, most of the states were divided into voting districts in a manner that gave more votes to the eastern part of the state than to the western part. 17 Thus, in some states, like Virginia and South Carolina, small farmers who may have favored the Anti-Federalist position were unable to elect as many delegates to state ratification conventions as those who lived in the east. Small settlements may also have lacked the funds to send delegates to the convention. 18

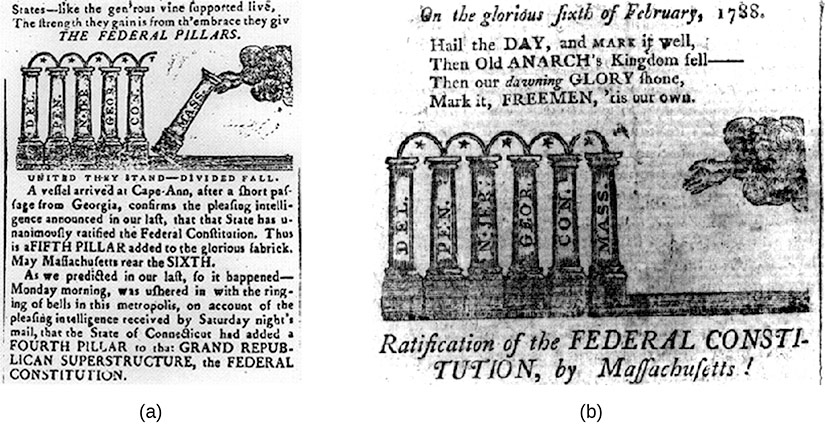

In all the states, educated men authored pamphlets and published essays and cartoons arguing either for or against ratification ( Figure 2.11 ). Although many writers supported each position, it is the Federalist essays that are now best known. The arguments these authors put forth, along with explicit guarantees that amendments would be added to protect individual liberties, helped to sway delegates to ratification conventions in many states.

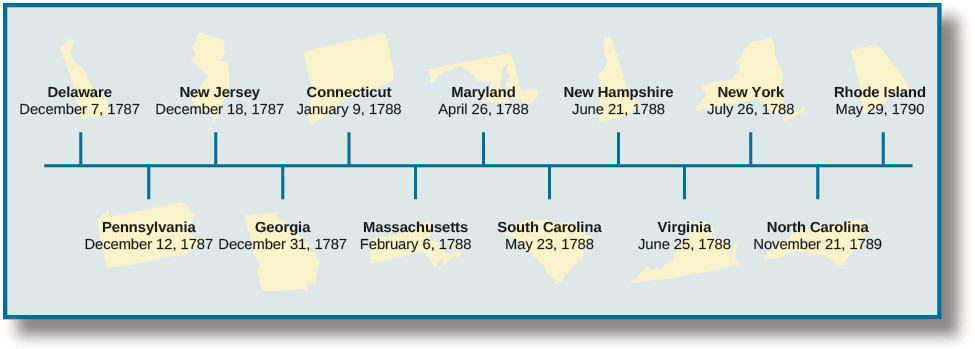

For obvious reasons, smaller, less populous states favored the Constitution and the protection of a strong federal government. As shown in Figure 2.12 , Delaware and New Jersey ratified the document within a few months after it was sent to them for approval in 1787. Connecticut ratified it early in 1788. Some of the larger states, such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, also voted in favor of the new government. New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution in the summer of 1788.

Although the Constitution went into effect following ratification by New Hampshire, four states still remained outside the newly formed union. Two were the wealthy, populous states of Virginia and New York. In Virginia, James Madison’s active support and the intercession of George Washington, who wrote letters to the convention, changed the minds of many. Some who had initially opposed the Constitution, such as Edmund Randolph, were persuaded that the creation of a strong union was necessary for the country’s survival and changed their position. Other Virginia delegates were swayed by the promise that a bill of rights similar to the Virginia Declaration of Rights would be added after the Constitution was ratified. On June 25, 1788, Virginia became the tenth state to grant its approval.

The approval of New York was the last major hurdle. Facing considerable opposition to the Constitution in that state, Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay wrote a series of essays, beginning in 1787, arguing for a strong federal government and support of the Constitution ( Figure 2.13 ). Later compiled as The Federalist and now known as The Federalist Papers , these eighty-five essays were originally published in newspapers in New York and other states under the name of Publius, a supporter of the Roman Republic.

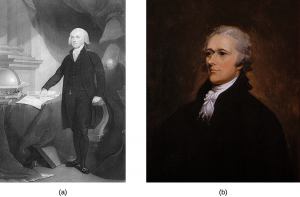

The essays addressed a variety of issues that troubled citizens. For example, in Federalist No. 51, attributed to James Madison ( Figure 2.14 ), the author assured readers they did not need to fear that the national government would grow too powerful. The federal system, in which power was divided between the national and state governments, and the division of authority within the federal government into separate branches would prevent any one part of the government from becoming too strong. Furthermore, tyranny could not arise in a government in which “the legislature necessarily predominates.” Finally, the desire of office holders in each branch of government to exercise the powers given to them, described as “personal motives,” would encourage them to limit any attempt by the other branches to overstep their authority. According to Madison , “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Other essays countered different criticisms made of the Constitution and echoed the argument in favor of a strong national government. In Federalist No. 35 , for example, Hamilton ( Figure 2.14 ) argued that people’s interests could in fact be represented by men who were not their neighbors. Indeed, Hamilton asked rhetorically, would American citizens best be served by a representative “whose observation does not travel beyond the circle of his neighbors and his acquaintances” or by someone with more extensive knowledge of the world? To those who argued that a merchant and land-owning elite would come to dominate Congress, Hamilton countered that the majority of men currently sitting in New York’s state senate and assembly were landowners of moderate wealth and that artisans usually chose merchants, “their natural patron[s] and friend[s],” to represent them. An aristocracy would not arise, and if it did, its members would have been chosen by lesser men. Similarly, Jay reminded New Yorkers in Federalist No. 2 that union had been the goal of Americans since the time of the Revolution. A desire for union was natural among people of such “similar sentiments” who “were united to each other by the strongest ties,” and the government proposed by the Constitution was the best means of achieving that union.

Objections that an elite group of wealthy and educated bankers, businessmen, and large landowners would come to dominate the nation’s politics were also addressed by Madison in Federalist No. 10 . Americans need not fear the power of factions or special interests, he argued, for the republic was too big and the interests of its people too diverse to allow the development of large, powerful political parties. Likewise, elected representatives, who were expected to “possess the most attractive merit,” would protect the government from being controlled by “an unjust and interested [biased in favor of their own interests] majority.”

For those who worried that the president might indeed grow too ambitious or king-like, Hamilton, in Federalist No. 68 , provided assurance that placing the leadership of the country in the hands of one person was not dangerous. Electors from each state would select the president. Because these men would be members of a “transient” body called together only for the purpose of choosing the president and would meet in separate deliberations in each state, they would be free of corruption and beyond the influence of the “heats and ferments” of the voters. Indeed, Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 70 , instead of being afraid that the president would become a tyrant, Americans should realize that it was easier to control one person than it was to control many. Furthermore, one person could also act with an “energy” that Congress did not possess. Making decisions alone, the president could decide what actions should be taken faster than could Congress, whose deliberations, because of its size, were necessarily slow. At times, the “decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch” of the chief executive might be necessary.

Link to Learning

The Library of Congress has The Federalist Papers on their website. The Anti-Federalists also produced a body of writings, less extensive than The Federalists Papers , which argued against the ratification of the Constitution. However, these were not written by one small group of men as The Federalist Papers had been. A collection of the writings that are unofficially called The Anti-Federalist Papers is also available online.

The arguments of the Federalists were persuasive, but whether they actually succeeded in changing the minds of New Yorkers is unclear. Once Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788, New York realized that it had little choice but to do so as well. If it did not ratify the Constitution, it would be the last large state that had not joined the union. Thus, on July 26, 1788, the majority of delegates to New York’s ratification convention voted to accept the Constitution. A year later, North Carolina became the twelfth state to approve. Alone and realizing it could not hope to survive on its own, Rhode Island became the last state to ratify, nearly two years after New York had done so.

Finding a Middle Ground

Term limits.

One of the objections raised to the Constitution’s new government was that it did not set term limits for members of Congress or the president. Those who opposed a strong central government argued that this failure could allow a handful of powerful men to gain control of the nation and rule it for as long as they wished. Although the framers did not anticipate the idea of career politicians, those who supported the Constitution argued that reelecting the president and reappointing senators by state legislatures would create a body of experienced men who could better guide the country through crises. A president who did not prove to be a good leader would be voted out of office instead of being reelected. In fact, presidents long followed George Washington’s example and limited themselves to two terms. Only in 1951, after Franklin Roosevelt had been elected four times, was the Twenty-Second Amendment passed to restrict the presidency to two terms.

Are term limits a good idea? Should they have originally been included in the Constitution? Why or why not? Are there times when term limits might not be good?

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Glen Krutz, Sylvie Waskiewicz, PhD

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: American Government 3e

- Publication date: Jul 28, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/2-4-the-ratification-of-the-constitution