- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Critical Thinking & Language Learning

From a very young age, learning a language is of utmost importance. Starting from our mother tongue, we then learn another language (usually English, Spanish, German or French). Learning – and teaching- methods though, don’t always work as expected. Conventional teaching and learning techniques are starting to become a feature of the past now, as new methods are considered to be more efficient. One of these techniques is critical thinking.

Critical Thinking Defined

When we discuss Critical thinking, we refer to some specific practices. First of all, critical thinking occurs when we doubt something- a text, an idea, a political statement, a speech, a piece of information, an article.

Second of all, it also occurs when we look at a specific issue or problem, from more than one perspective. Third of all, it also occurs when we criticize something, in a constructive way. For example, disagreeing with the words of a journalist, while pointing out the problem and supporting our opinion with arguments. Also, when critically viewing new information, we can find more meanings that might be indirect.

Therefore, it becomes apparent why Critical Thinking is necessary when learning a language.

Critical thinking affecting Language Learning

The first person who supported the use of Critical thinking in education was the American philosopher John Dewey. According to his beliefs, teaching Critical thinking to the students is actually the ultimate goal of education.

In combination with this belief, school/ college activities that require Critical thinking can affect the efficiency of learning for students. Combining experiential learning with real-life activities urges a student to think outside the box, using his/her emotional intelligence. Thus, learning is achieved in a way that the student understands and enjoys more.

In addition, learning a language can be achieved by many practical activities that combine critical thinking with the material taught in class. Hence, learning becomes more inclusive and practical.

Critical thinking improving Language Learning

In many cases, it has been proved that language learning is achieved way better when activities that require critical thinking are included. This happens because students not only use their existing knowledge but because they also apply it to a real-life situation. In this way, the knowledge they acquire during these activities is more memorable.

Furthermore, when a student participates in such activities, he/she becomes an “active participant”, as he/she interacts with other students while constructing his/her learning. Through this process, the student perceives the knowledge learned at the moment in his/her own way, and because of this fact, this knowledge is remembered – and used- more easily (learning stops being too theoretical and is applied in practice).

Overall, critical thinking allows a learner to “process” a language, and perceive it in his/her own way. Therefore, language learning becomes easier, more efficient, and applicable.

As critical thinking affects language learning, language learning affects critical thinking too. Learning a language requires the ability to learn a whole new ideology, a very different culture – in many cases-, and practically, a different language from yours ( in many cases). That means that you learn a set of grammatic and syntactic rules that might not be the same as the ones of your own language.

Overall, learning a language demands many skills that help you acquire a whole new ideology. Therefore, language learning “sharpens” your Critical thinking skills, as you get to compare and contrast your mother tongue with another language ( when learning a second language).

Language learning improving Critical Thinking Skills

Per the above fact, it is useful to mention that critical thinking skills are improved through the process of language learning. Critical thinking and language learning support each other at a level where Critical thinking can almost teach you the language itself.

For example, critically assessing a situation and its character- during which you have to communicate in a specific language with someone, has already given you the necessary “tool” that guarantees the efficiency of the communication.

In addition, problem-solving and conflict can also improve critical thinking skills. For example, in a conversation where you have to support your argument without been affected by the potential disagreement and annoyance of the other participant (during a language learning-related activity), proper selection of language is needed. This can be accomplished by applying your knowledge and by using your critical thinking skills.

Furthermore, while learning a language a person can participate in various activities where different kinds of critical thinking are unlocked. Therefore, critical thinking becomes more spherical. As a necessary and useful process, language learning provides critical thinking with a lot more dimensions.

The kind of relationship between Critical thinking and language learning

As mentioned above, Critical thinking and language learning support and affect each other. It is very important to realize that language learning can become much more efficient and interesting if critical thinking is applied and used. At the same time, critical thinking skills can be acquired and improved while learning a language, because of the variety of exercises and activities this process includes.

Their relationship is only positive. They both positively contribute to the efficiency of each other. Nevertheless, Critical Thinking is a skill, which we use on numerous occasions. Language learning is a procedure, that needs critical thinking.

In other words, critical thinking is not dependent on language learning, when it comes to its improvement and formation whereas language learning needs critical thinking, as it has the goal of being as much efficient as possible.

Overall, it is a unique relationship during which each “party” offers and receives positive traits and features.

On An Ending Note

Taking everything into consideration, we can see that this relationship between Language learning and critical thinking is very beneficial, for both parties. However, viewing this relationship from a strict perspective, we can conclude that Language Learning ( a.k.a., the educational field) can take into advantage Critical thinking as a tool that guarantees effective learning and use it more.

https://ajssr.unitar.my/doc/vol1i2/2107.pdf

https://unitec.researchbank.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10652/3680/revised-critical-thinking-paper-May-2016-.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

You may also like

What Is Drone Mentality?

Drone mentality is a pattern of going through the motions, paying little to no attention to what’s going on around you. Think […]

Thinking Critically About New Information

We are constantly inundated with new information all of the time, even if it’s just sensory input from what we smell, hear, […]

What is historical thinking?

Historical thinking is something that more and more people are taking an interest in, but do you know what it really means? […]

Thinking Critically About Your Personal Finance in a Recession

You don’t have to be a world-renowned economist to see the financial storm clouds brewing all around us. Inflation is through […]

- Our Mission

5 Ways to Boost Critical Thinking in World Language Classes

One way to raise students’ engagement is to ask them to do more work—meaningful work with authentic materials from the target culture.

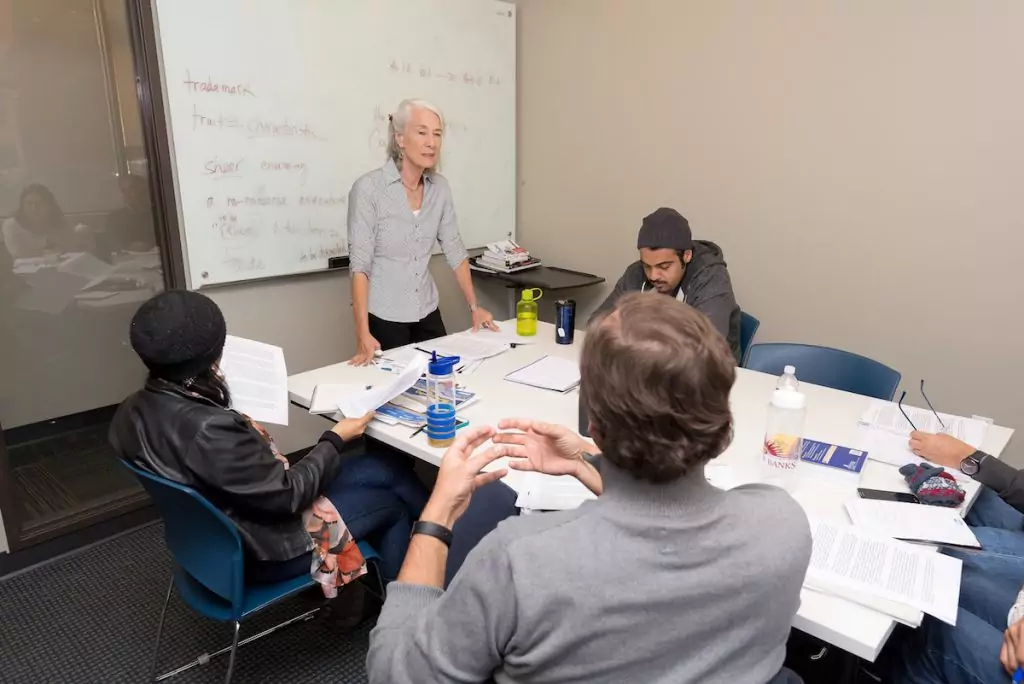

As teachers, we’ve all experienced lessons that fell flat. The students were uninspired or disengaged, and wore blank, expressionless faces. While these moments can feel disappointing and discouraging, they help us learn and improve by honing our instructional choices.

These experiences have provoked me to think differently about my lessons—what could I do differently? Where was I going wrong? I realized that part of the reason my students seemed uninspired in these moments was likely because I was not asking them to do much. They were not thinking critically, making cultural comparisons, or problem-solving. This realization led me to boost the levels of rigor and critical thinking in my world language classes.

5 Ways to Increase Students’ Critical Thinking

1. Evaluate the questions you’re asking: Are your questions crafted to produce detailed, in-depth responses, or do they lead to one-word answers? Do they allow students to draw on their personal experiences or offer their opinions? Do they inspire students to passionately debate, or to engage in an exchange with a peer? Are students answering these questions enthusiastically? Let’s look at an example of a flat question versus a dynamic one.

“Why is global warming a serious issue?” is an important question, but it doesn’t require students to offer details about their thoughts or opinions on the matter, and it is unlikely to result in an enthusiastic response. Changing it to, “How could the effects of global warming impact or change your future life, and how does this make you feel?” directly solicits students’ perspectives. This question gets students thinking about their own lives, which can heighten their engagement.

2. Place culture at the core of your lessons and units: Language teachers are not solely responsible for teaching a language—we should also be exposing our students to the culture(s) associated with the target language. Our students often make deeper connections with cultural aspects of the language rather than with the linguistic ones. Embrace this!

If a Spanish teacher, for example, is teaching a unit about foods, they can focus on the Mediterranean diet in Spain and make a connection to healthy lifestyle practices. If they’re teaching a unit about the environment, they might focus on why Costa Rica is a leader in sustainability and ecotourism. Weaving cultural points into essential questions adds another layer of rigor to our units of study.

Try requiring that students make cultural comparisons between their native culture(s) and the target one. This gives them the opportunity to think critically about their own cultures and allows them to recognize that not every culture is the same, guiding them to be more culturally competent global citizens.

3. Plan lessons and design activities with Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy: Some powerful verbs featured in Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy —such as recall , interpret , infer , execute , differentiate , critique , and produce —draw attention to the skills we want to develop in our students.

For example, we want our students to interpret authentic resources such as infographics or podcasts. We want them to infer the meaning behind the titles of news articles or short stories. We want them to differentiate between cultural practices in the target language country and the United States. We want them to critique statements or texts that we present to them, and we want them to produce well-executed pieces of writing or oral presentations.

Let these verbs guide your methods and lesson planning. Engaging in the acts of recalling, interpreting, inferring, executing, differentiating, critiquing and producing will aid your students in accomplishing more rigorous tasks.

4. Incorporate authentic resources: There’s no better way to expose students to culture and higher-order thinking than with authentic resources—real-life materials from the target country, including infographics, articles, songs, films, podcasts, commercials, written ads, and so on.

Authentic resources need not be reserved for higher-level classes—they can be used at any level. Adapt the task—not the resource—for the appropriate level. Level one students often need an authentic resource to pique their interest in the language and culture. For example, when teaching novice students about foods and eating habits in the target country, incorporate an authentic menu for them to examine and analyze. Create a basic task like a graphic organizer for them to complete with the menu. They don’t need to understand every word in order to complete the task. Intermediate level students can likely interpret an authentic resource with little to no assistance.

Using authentic resources can entice students to continue on their language learning journey, igniting their curiosity. Such resources also present an increased level of rigor and challenge. Students are required to evaluate and analyze an authentic cultural product when evaluating these resources.

5. Give students independence: While it’s sometimes tempting to lecture students and control the entirety of the class period, releasing some control can be empowering. Let students think independently and design some of their own tasks. Require them to problem-solve. Give them choices. Let them own their learning and take an active role in it. Giving students time to work independently fosters a rigorous environment in which students are able to think critically without constant assistance.

Rather than providing questions immediately after reading an article with your students, allow them to come up with the questions. Identify key vocabulary by asking students which words they associate with the given topic instead of providing a list. And instead of leading every class discussion, assign students different jobs in group discussions, or allow them to take turns facilitating a whole-class discussion. When students are given a chance to lead, they generally rise to the occasion, which can lead to deeper learning.

Explore More

Stay in our orbit.

Stay connected with industry news, resources for English teachers and job seekers, ELT events, and more.

Explore Topics

- Global Elt News

- Job Resources

- Industry Insights

- Teaching English Online

- Classroom Games / Activities

- Teaching English Abroad

- Professional Development

Popular Articles

- 5 Popular ESL Teaching Methods Every Teacher Should Know

- 10 Fun Ways to Use Realia in Your ESL Classroom

- How to Teach ESL Vocabulary: Top Methods for Introducing New Words

- Advice From an Expert: TEFL Interview Questions & How to Answer Them

- What Is TESOL? What Is TEFL? Which Certificate Is Better – TEFL or TESOL?

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the ESL Classroom

- Linda D'Argenio

- December 22, 2022

Critical thinking has become a central concept in today’s educational landscape, regardless of the subject taught. Critical thinking is not a new idea. It has been present since the time of Greek philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Socrates’ famous quote, “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel,” underscores the nature of learning (students are not blank slates to be filled with content by their teachers) and the significance of inquisitiveness in a true learning process, both in the ESL classroom and in the wider world of education. Teaching critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom will benefit your students throughout their language-learning journey.

In more recent times, philosopher John Dewey made critical thinking one of the cornerstones of his educational philosophy. Nowadays, educators often quote critical thinking as the most important tool to sort out the barrage of information students are exposed to in our media-dominated world , to analyze situations and elaborate solutions. Teaching critical thinking skills is an integral part of teaching 21st-century skills .

Table of Contents

What is critical thinking?

There are many definitions of critical thinking. They are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary. Some of the main ones are outlined below.

Dewey’s definition

In John Dewey’s educational theory, critical thinking examines the beliefs and preexisting knowledge that individuals use to assess situations and make decisions. If such beliefs and knowledge are faulty or unsupported, they will lead to faulty assessments and decision-making. In essence, Dewey advocated for a scientific mindset in approaching problem-solving .

Goal-directed thinking

Critical thinking is goal-directed. We question the underlying premises of our reflection process to ensure we arrive at the proper conclusions and decisions.

Critical thinking as a metacognitive process

According to Matthew Lipman, in Thinking in Education, “Reflective thinking is thinking that is aware of its own assumptions and implications as well as being conscious of the reasons and evidence that support this or that conclusion. (…) Reflective thinking is prepared to recognize the factors that make for bias, prejudice, and self-deception . It involves thinking about its procedures at the same time as it involves thinking about its subject matter” (Lipman, 2003).

Awareness of context

This is an important aspect of critical thinking. As stated by Diane Halpern in Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking , “[The critical] thinker is using skills that are thoughtful and effective for the particular context and type of thinking task” (Halpern, 1996)

What are the elements of critical thinking?

Several elements go into the process of critical thinking.

- Identifying the problem. If critical thinking is viewed mainly as a goal-oriented activity, the first element is to identify the issue or problem one wants to solve. However, the critical thinking process can be triggered simply by observation of a phenomenon that attracts our attention and warrants an explanation.

- Researching and gathering of information that is relevant to the object of inquiry. One should gather diverse information and examine contrasting points of view to achieve comprehensive knowledge on the given topic.

- Evaluation of biases. What biases can we identify in the information that has been gathered in the research phase? But also, what biases do we, as learners, bring to the information-gathering process?

- Inference. What conclusions can be derived by an examination of the information? Can we use our preexisting knowledge to help us draw conclusions?

- Assessment of contrasting arguments on an issue. One looks at a wide range of opinions and evaluates their merits.

- Decision-making. Decisions should be based on the above.

Why is critical thinking important in ESL teaching?

The teaching of critical thinking skills plays a pivotal role in language instruction. Consider the following:

Language is the primary vehicle for the expression of thought, and how we organize our thoughts is closely connected with the structure of our native language. Thus, critical thinking begins with reflecting on language. To help students understand how to effectively structure and express their thinking processes in English, ESL teachers need to incorporate critical thinking in English Language Teaching (ELT) in an inclusive and interesting way .

For ESL students to reach their personal, academic, or career goals, they need to become proficient in English and be able to think critically about issues that are important to them. Acquiring literacy in English goes hand in hand with developing the thinking skills necessary for students to progress in their personal and professional lives. Thus, teachers need to prioritize the teaching of critical thinking skills.

How do ESL students develop critical thinking skills?

Establishing an effective environment

The first step in assisting the development of critical thinking in language learning is to provide an environment in which students feel supported and willing to take risks. To express one’s thoughts in another language can be a considerable source of anxiety. Students often feel exposed and judged if they are not yet able to communicate effectively in English. Thus, the teacher should strive to minimize the “affective filter.” This concept, first introduced by Stephen Krashen, posits that students’ learning outcomes are strongly influenced by their state of mind. Students who feel nervous or anxious will be less open to learning. They will also be less willing to take the risks involved in actively participating in class activities for fear that this may expose their weaknesses.

One way to create such an environment and facilitate students’ expression is to scaffold language so students can concentrate more on the message/content and less on grammar/accuracy.

Applying context

As mentioned above, an important aspect of critical thinking is context. The information doesn’t exist in a vacuum but is always received and interpreted in a specific situational and cultural environment. Because English learners (ELs) come from diverse cultural and language backgrounds and don’t necessarily share the same background as their classmates and teacher, it is crucial for the teacher to provide a context for the information transmitted. Contextualization helps students to understand the message properly.

Asking questions

One of the best ways to stimulate critical thinking is to ask questions. According to Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy ( Taxonomy of Educational Objectives , 1956), thinking skills are divided into lower-order and higher-order skills. Lower-order skills include knowledge, comprehension, and application; higher-order skills include analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. To stimulate critical thinking in ELT, teachers need to ask questions that address both levels of thinking processes. For additional information, read this article by the TESL Association of Ontario on developing critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom .

Watch the following clip from a BridgeUniverse Expert Series webinar to learn how to set measurable objectives based on Bloom’s Taxonomy ( watch the full webinar – and others! – here ):

How can we implement critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom?

Several activities can be used in the ESL classroom to foster critical thinking skills. Teaching critical thinking examples include:

Activities that scaffold language and facilitate students’ expression

These can be as basic as posting lists of important English function words like conjunctions, personal and demonstrative pronouns, question words, etc., in the classroom. Students can refer to these tables when they need help to express their thoughts in a less simplistic way or make explicit the logical relation between sentences (because… therefore; if… then; although… however, etc.). There are a variety of methods to introduce new vocabulary based on student age, proficiency level, and classroom experience.

Activities that encourage students to make connections between their preexisting knowledge of an issue and the new information presented

One such exercise consists of asking students to make predictions about what will happen in a story, a video, or any other context. Predictions activate the students’ preexisting knowledge and encourage them to link it with the new data, make inferences, and build hypotheses.

Critical thinking is only one of the 21st-century skills English students need to succeed. Explore all of Bridge’s 21st-Century Teaching Skills Micro-credential courses to modernize your classroom!

Change of perspective and contextualization activities.

Asking students to put themselves in someone else’s shoes is a challenging but fruitful practice that encourages them to understand and empathize with other perspectives. It creates a different cultural and emotional context or vantage point from which to consider an issue. It helps assess the merit of contrasting arguments and reach a more balanced conclusion.

One way of accomplishing this is to use a written text and ask students to rewrite it from another person’s perspective. This automatically leads students to adopt a different point of view and reflect on the context of the communication. Another is to use roleplay . This is possibly an even more effective activity. In role-play, actors tend to identify more intimately with their characters than in a written piece. There are other elements that go into acting, like body language, voice inflection, etc., and they all need to reflect the perspective of the other.

Collaborative activities

Activities that require students to collaborate also allow them to share and contrast their opinions with their peers and cooperate in problem-solving (which, after all, is one of the goals of critical thinking). Think/write-pair-share is one such activity. Students are asked to work out a problem by themselves and then share their conclusions with their peers. A collaborative approach to learning engages a variety of language skill sets, including conversational skills, problem-solving, and conflict resolution, as well as critical thinking.

In today’s educational and societal context, critical thinking has become an important tool for sorting out information, making decisions, and solving problems. Critical thinking in language learning and the ESL classroom helps students to structure and express their thoughts effectively. It is an essential skill to ensure students’ personal and professional success.

Take an in-depth look at incorporating critical thinking skills into the ESL classroom with the Bridge Micro-credential course in Promoting Critical Thinking Skills.

Linda D'Argenio

Linda D'Argenio is a native of Naples, Italy. She is a world language teacher (English, Italian, and Mandarin Chinese,) translator, and writer. She has studied and worked in Italy, Germany, China, and the U.S. In 2003, Linda earned her doctoral degree in Classical Chinese Literature from Columbia University. She has taught students at both the school and college levels. Linda lives in Brooklyn, NY.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Teaching and Assessing Critical Thinking in Second Language Writing: An Infusion Approach

Dong Yanning holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia. She is currently vice president of Higher English Education Publishing at Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. Her research focuses on teaching English as a second language, second language writing and critical thinking.

Recent calls for promoting students’ critical thinking (CT) abilities leave second language (L2) teachers wondering how to integrate CT into their existing agenda. Framed by Paul and Elder’s (2001) CT model, the study explores how CT could be effectively taught in L2 writing as a way to improve students’ CT skills and L2 writing performance. In this study, an infusion approach was developed and implemented in actual classroom teaching. Mixed methods were employed to investigate: (1) the effectiveness of the infusion approach on improving students’ CT and L2 writing scores; (2) the relationship between students’ CT and L2 writing scores; and (3) the effects of the infusion approach on students’ learning of CT and L2 writing. The results of the statistical analyses indicate that the infusion approach has effectively improved students’ CT and L2 writing scores and that there was a significant positive relationship ( r =0.893, p <0.01) between students’ CT and L2 writing scores. The results of the post-study interview illustrate that the infusion approach has beneficial effects on students’ learning of CT and L2 writing by bridging the abstract CT theories and interactive writing activities and by integrating the instruction and practice of CT into those of L2 writing.

About the author

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research , 78 (4), 1102-1134. 10.3102/0034654308326084 Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, L. W. & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Search in Google Scholar

Bailin, S., & Siegel, H. (2003). Critical thinking. In N. Blake, P. Smeyers, R. Smith, & P. Standish (Eds.), The Blackwell guide to the philosophy of education (pp. 181-193). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. Search in Google Scholar

Bean, J. C. (2011). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Search in Google Scholar

Beyer, B. K. (2008). How to teach thinking skills in social studies and history. The Social Studies , 99 (5), 196-201. 10.3200/TSSS.99.5.196-201 Search in Google Scholar

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Committee of college and university examiners: Handbook 1 cognitive domain . New York, NY: David McKay Company, Inc. Search in Google Scholar

Cambridge ESOL. (2011). Cambridge IELTS 8 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Case, R. (2005). Moving critical thinking to the main stage. Education Canada , 45 (2), 45-49. Search in Google Scholar

Çavdar, G., & Doe, S. (2012). Learning through writing: Teaching critical thinking skills in writing assignments. PS: Political Science and Politics , 45 (2), 298-306. 10.1017/S1049096511002137 Search in Google Scholar

Coe, C. D. (2011). Scaffolded writing as a tool for critical thinking: Teaching beginning students how to write arguments. Teaching Philosophy , 34 (1), 33. 10.5840/teachphil20113413 Search in Google Scholar

Cottrell, S. (2005). Critical thinking skills: Developing effective analysis and argument . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. Search in Google Scholar

Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educational Researcher , 18 (3), 4-10. 10.3102/0013189X018003004 Search in Google Scholar

Ennis, R. H. (2003). Critical thinking assessment. In D. Fasko (Ed.), Critical thinking and reasoning (pp. 293–310). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Search in Google Scholar

Facione, P. A. (1990a). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction . Santa Clara, CA: The California Academic. Search in Google Scholar

Facione, P. A. (1990b). The California Critical Thinking Skills Test . Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press. Search in Google Scholar

Ferris, D. (2003). Response to student writing: Implications for second language students . Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 10.4324/9781410607201 Search in Google Scholar

Franklin, D., Weinberg, J., & Reifler, J. (2014). Teaching writing and critical thinking in large political science classes. Journal of Political Science Education , 10 (2), 155-165. 10.1080/15512169.2014.892431 Search in Google Scholar

Hatcher, D. L. (1999). Why critical thinking should be combined with written composition. Informal Logic , 19 (2&3), 171-183. 10.22329/il.v19i2.2326 Search in Google Scholar

IELTS Writing Task 2 Band Descriptors. (n.d.). IELTS . Retrieved March 25, 2013 from http://www.ielts.org/researchers/score_processing_and_reporting.aspx#Writing Search in Google Scholar

Jacobson, J. & Lapp, D. (2010). Revisiting Bloom’s taxonomy: A framework for modeling writing and critical thinking skills. The California Reader , 43 (3), 32-47. Search in Google Scholar

Li, L. W. (2011).&英语写作中的读者意识与思辨能力培养——基于教学行动研究的探讨[An action research on how to increase reader awareness and critical thinking]. Foreign Language in China, 8 (3), 66-73. Search in Google Scholar

Marin, L. M., & Halpern, D. F. (2011). Pedagogy for developing critical thinking in adolescents: Explicit instruction produces greatest gains. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 6 (1), 1-13. 10.1016/j.tsc.2010.08.002 Search in Google Scholar

McPeck, J. E. (1981). Critical thinking and education . Oxford: M. Robertson. Search in Google Scholar

Min, H. (2005). Training students to become successful peer reviewers. System, 33 (2), 293-308. 10.1016/j.system.2004.11.003 Search in Google Scholar

Min, H. (2006). The effects of trained peer review on L2 students’ revision types and writing quality. Journal of Second Language Writing , 15 (2), 118-141. 10.1016/j.jslw.2006.01.003 Search in Google Scholar

Moghaddam, M. M., & Malekzadeh, S. (2011). Improving L2 writing ability in the light of critical thinking. Theory and Practice in Language Studies , 1 (7), 789-797. 10.4304/tpls.1.7.789-797 Search in Google Scholar

Mulnix, J. W., Mulnix, M. J. (2010). Using a writing portfolio project to teach critical thinking skills. Teaching Philosophy, 33 (1), 27. 10.5840/teachphil20103313 Search in Google Scholar

Norris, S. P. (2003). The meaning of critical thinking test performance: The effects of abilities and dispositions on scores. In D. Fasko (Ed.), Critical thinking and reasoning: Current research, theory and practice . Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. Search in Google Scholar

Nosich, G. M. (2005). Problems with two standard models for teaching critical thinking. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2005 (130), 59-67. 10.1002/cc.196 Search in Google Scholar

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2001). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your learning and your life . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Search in Google Scholar

Petress, K. (2004). Critical thinking: An extended definition. Education , 124 (3), 461-466. Search in Google Scholar

Rao, Z. (2007). Training in brainstorming and developing writing skills. ELT Journal , 61 (2), 100-106. 10.1093/elt/ccm002 Search in Google Scholar

Richards, J. (1990). New trends in the teaching of writing in ESL/L2. In Z. Wang (Ed.), ELT in China: Papers presented at the International Symposium on Teaching English in the Chinese context . Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. Search in Google Scholar

Shi, L. (1998). Effects of prewriting discussions on adult ESL students’ compositions. Journal of Second Language Writing , 7 (3), 319-345. 10.1016/S1060-3743(98)90020-0 Search in Google Scholar

Silva, E. (2008). Measuring skills for the 21st Century . Washington, DC: Education Sector. Search in Google Scholar

Tiruneh, D. T., Verburgh, A., & Elen, J. (2014). Effectiveness of critical thinking instruction in higher education: A systematic review of intervention studies. Higher Education Studies , 4 (1), 1. 10.5539/hes.v4n1p1 Search in Google Scholar

Tsui, L. (1999). Courses and instruction affecting critical thinking. Research in Higher Education , 40 (2), 185-200. 10.1023/A:1018734630124 Search in Google Scholar

Understand how to calculate your IELTS scores. (2014). Retrieved March 21, 2014, from http://takeielts.britishcouncil.org/find-out-about-results/understand-your-ielts-scores . Search in Google Scholar

Watson, G., & Glaser, E. M. (1980). Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal . Cleveland, OH: Psychological Corporation. Search in Google Scholar

Zeng, M. R. (2012).论英语议论文写作与思辨能力培养[Argumentative writing and the cultivation of critical thinking ability]. Education Teaching Forum, 23 , 67-70. Search in Google Scholar

Appendices: Appendix A

CT-oriented Brainstorming Worksheet for the Experimental Group

CT-oriented Peer-review Checklist

The Criteria for Assessing CT in L2 Writing

© 2017 FLTRP, Walter de Gruyter, Cultural and Education Section British Embassy

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

MINI REVIEW article

English as a foreign language teachers’ critical thinking ability and l2 students’ classroom engagement.

- School of Foreign Studies, Hebei University, Baoding, China

Critical thinking has been the focus of many studies considering the educational and social contexts. However, English as a foreign language (EFL) context is the one in which studies about critical thinking and its link to classroom engagement have not been carried out as much as expected. Hence, this study investigated to understand the association between EFL teachers’ critical thinking ability and students’ classroom engagement to get a broader understanding of the impact critical thinking has on students’ success. To do this, firstly, both variables of this study are defined and explicated. Then, the relationship between critical thinking and students’ classroom engagement is discussed. Finally, the implications of this research and also its limitations along with suggestions for further studies are put forward.

Introduction

“Critical thinking enables individuals to use standards of argumentation, rules of logic, standards of practical deliberation, standards governing inquiry and justification in specialized areas of study, standards for judging intellectual products, etc.” ( Bailin et al., 1999 , p. 291). Paul and Elder (2007) conceptualized critical thinking as the art of analysis and evaluation, considering the point that it can be improved since a quality life needs the quality of thinking. Facione (2011) noted that happiness cannot be guaranteed even if good judgment is practiced and critical thinking is enhanced; however, it undoubtedly offers more opportunities for this goal to be achieved. It has been stressed that autonomy can be shaped through critical thinking ability and one’s learning process can critically be evaluated ( Delmastro and Balada, 2012 ). According to a study conducted by Marin and Pava (2017) , English as a foreign language (EFL) critical thinker has the following characteristics: they are active, continuously asking questions, and seeking information which helps them build associations between L2 learning and other features of everyday life. They describe as people, having the capability to analyze and organize thoughts that can be expressed through speaking and writing. They almost always tries to put what has learned before into practice. Beyond doubt, in order to enhance critical thinking skill in EFL learners, teachers should consider the point that teaching is not just about grammar and vocabulary; instead, it concentrates on enhancing teaching, encouraging to be creative, encourage to learn independently, strategies for making decisions and evaluating himself. Similarly, opportunities must be provided by the educators to provide a learning environment in which autonomous learning, active engagement, reflection on learners’ learning process, and L2 advancement are emphasized, for instance, task-based activities. Thus, this study is different from other studies since the focus is placed on teachers’ critical thinking ability to help students thrive rather than students’ critical thinking ability. The reason is that differentiates it from the previous studies is that providing students with opportunities, in which thinking differently is appreciated, would be absolutely rewarding and it is the skill that should be much more highlighted in the studies. Therefore, critical thinking is a skill through which students’ confidence can be raised, leading to their active engagement in the classroom and their being successful since they can see the issues from a different point of view and novel solutions to those problems can be proposed. In the current study, first of all, both teachers’ critical thinking ability and students’ classroom engagement have been discussed. Given that, the association between these two variables has been dealt with. Then, the implications and restrictions of the study as well as some recommendations for further studies have been proposed.

Teachers’ Critical Thinking Ability

Critical thinking has attracted much attention since teachers’ way of thinking and beliefs has a pivotal impact on what students achieve in terms of academic success and attainments. Dewey (1933 , p. 9), who can be regarded as the father of modern critical thinking, conceptualized it as “active, persistent, and careful of a belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds which support it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” As defined by Chance (1986) , critical thinking is conceptualized as the capability that one puts into practice to do the followings through this ability: facts which are analyzed, ideas that are generated and organized, opinions that are defended, comparisons that are made, inferences that are drawn, arguments which are evaluated, ideas that are organized, and problems that are solved. As stated by Vdovina and Gaibisso (2013) , critical thinking is relevant to quality thinking that enables learners to communicate with others, gain knowledge, and deal with ideas, attitudes, and beliefs in a more skillful way. Based on what has been proposed by Shirkhani and Fahim (2011) , critical thinking is an integral factor in many ways. The first reason that can be taken into consideration is that when language learners take responsibility for the way they think; they can evaluate the way they learn in a more successful way. Secondly, critical thinking causes learners to experience a meaningful process of learning in which learning a language is meaningful to them. Thirdly, critical thinking and learners’ achievement are positively correlated. If the learners are shown how to think critically, they get proficient in learning a language. Likewise, Liaw (2007) study indicated that when the content-based approach is implemented in the class, it promotes EFL students’ critical thinking skills. It should be noted that in a content-based approach, attention is focused on the content and what can be perceived through it.

Besides, as Davidson (1998) noted, “the English teachers are expected to provide learners with the ability to communicate with native speakers, valuing overt comments, clever criticism, and intellectual claims.” In a similar manner, Meyers (1986) proposed that teachers can facilitate critical thinking through the activities that are assigned, the tasks that are set, and the feedback that is provided. A study done in a Chinese context by Li and Liu (2021) put forward the taxonomy of critical thinking ability in the EFL learning context and in this study, five skills through which critical thinking can be practiced, were proposed: analyzing, inferring, evaluating, synthesizing, and self-reflection/self-correction ( Wang and Derakhshan, 2021 ). Li (2021) also indicated that the development of critical thinking in international students can be facilitated by learning Chinese. According to a study done by Birjandi and Bagherkazemi (2010) , a critical thinker has the following characteristics:

• problems are identified by them and relevant solutions are dealt with,

• valid and invalid inferences are recognized by them,

• decisions and judgments are suspended by them when there is not enough evidence to prove it

• the difference between logical reasoning and justifying is perceived by them

• relevant questions are asked by them to see if their students have understood

• statements and arguments are evaluated

• lack of understanding can be accepted by them

• they have developed a sense of curiosity

• clear criteria for analyzing ideas are defined

• he is a good listener and gives others feedback

• he believes that critical thinking is a never-ending process that needs to be evaluated

• judgment is suspended by them until all facts have been collected

• they seek evidence for the assumptions to be advocated

• opinions are adjusted by them when there are some new facts

• incorrect information is easily rejected by them.

Consequently, according to the characteristics mentioned above, teachers with the ability to think critically is good problem solvers and when facing a problem during the class, they can have greater reasoning skills so as to find a solution to the problem. They are curious and they also ask their students questions to create a sense of curiosity in them. Additionally, they do not accept the new ideas easily, instead, they analyze them and sometimes make them better.

Classroom Engagement

Engagement is an inseparable part of the learning process and a multifold phenomenon. Classroom engagement refers to the amount of participation that students take in the class to be actively involved in the activities and whether the mental and physical activities have a goal. Engagement itself is a context-oriented phrase which relies on cultures, families, school activities, and peers ( Finn and Zimmer, 2012 ). It has been categorized into different groups: Behavioral engagement such as the amount to which students participate actively in the class; emotional engagement pertains to high levels of enthusiasm which is linked to high levels of boredom and anxiety; cognitive engagement such as the usage of learning strategy and self-regulation; agentic engagement such as the amount of conscious effort so that the learning experience would be enriched ( Wang and Guan, 2020 ; Hiver et al., 2021 ). Amongst the aforementioned categories, the one which is strongly important in the learning process is behavioral engagement in that it is relevant to the actual recognition of an individual’s learning talents ( Dörnyei, 2019 ). Another possibility that can be viewed is to consider engagement from two other aspects, internal and external. The former implies how much time and effort is allocated to the process of the learning. The latter entails the measures that are taken at the institutional level so that the resources would be dealt with along with other options of learning and services for support, encouraging the involvement in activities leading to the possible outcomes such as consistency and satisfaction ( Harper and Quaye, 2009 ).

Much attention is deserved to be paid to engagement since it is perceived as a behavioral means with which students’ motivation can be realized and as a result, development through the learning process can occur ( Jang et al., 2010 ). Active involvement should be strengthened in L2 classes to prevent disruptive behaviors and diminish the valence of emotions that are negative such as feeling anxious, frustrated, and bored.

Regarding “classroom engagement,” its opposie word “disengagement” can play a significant role in not engaging the students in the class, leading to them feeling bored and demotivated in the class, so from this aspect, it would be worth considering this phrase as well. It has been claimed by some authors ( Skinner, 2016 ) that disengagement itself does not happen frequently in educational settings due largely to the fact that it is related to extreme behaviors, and it is when another phrase disaffection can be considered significant. Disaffection is characterized by disinterest, aversion, resignation, and reduced effort. Therefore, our perception of boredom as a complex emotion can be enhanced, and it can be dealt with more systematically if boredom is viewed through the following factors, disengagement, and disaffection ( Wang and Guan, 2020 ; Derakhshan et al., 2021 ). As Elder and Paul (2004) mentioned, students should be taught to actively make questions- that is a good emblem of engagement- which is a radical part of critical thinking. The more the students can question, the more they can learn. Some students get accustomed to memorizing the facts and have never been faced with the outcomes of the poor decisions they made since there is always someone to back them and they had better be challenged, being questioned by their teachers ( Rezaei et al., 2011 ).

The Relationship Between Teachers’ Critical Thinking Ability and Classroom Engagement

Critical thinking has been said to widen one’s horizon because it may shape students’ mindsets and help them take a look at items from a different viewpoint. When one has learned to think critically, they will never accept the status quo easily, he will welcome the opposing ideas and will evaluate the arguments. In the EFL context, when a learner has the capability to think critically, or he has been taught to think critically, he always looks for reasons learning new materials and in this respect, his curiosity allows him to learn everything in depth and challenge his schemata to make a link between the newly learned ideas and the ones he has already known. Critical thinking is not a term that can be utilized just for the specific type of people; it can be taught and practiced to be enhanced. The way ideas can be generated and the way comparisons can be made is highly relevant to what has been called critical thinking. Different items can be conceptualized in different ways when we look at them through the lens of critical thinking; therefore, it can have a positive effect on students’ mindsets and the way they live. From an educational point of view, the decisions that have been made by the students, the solutions that have been put forward to tackle a problem when it comes to a learning context, and the way through which their process of learning is ameliorated are all impacted by teachers’ critical thinking. When teachers think critically and they strive to see different skills from a different point of view, it is where students’ sense of curiosity is tickled and their imagination is stretched so as to think of things in a various way.

Implications and Further Suggestions for Research

Critical thinking is believed to have an enormous effect on students’ classroom engagement. As mentioned above, according to Dewey (1933) , the more the students practice thinking critically, the more successful they are in terms of academic achievements because they can decide more rationally, and their problems can be addressed more sensibly. Attention should be paid that this study is of great significance for those people who are engaged in the learning process including those devising curriculums, develop materials, teachers, and learners. Critical thinking is a skill that should be developed in learners so that they would compare and contrast ideas, and as a result, decide wisely and accomplish what they have planned for. Accordingly, opportunities must be provided by the educators to provide a learning environment in which autonomous learning, active engagement, reflection on learners’ learning process, and L2 advancement are emphasized, for example, task-based activities ( Han and Wang, 2021 ).

Additionally, further studies can be done to find more about the variables in this study.

With regard to various age groups, the understanding of critical thinking might be different. Teenagers are said to start thinking critically and hypothetically; however, undoubtedly there is a big difference between what can be perceived about critical thinking by teenagers and adolescents in the educational contexts. Consequently, how different levels of critical thinking can be conceptualized in the learning context is one of the studies that can be conducted in the future. Secondly, teachers’ success and well-being are also tremendously affected by the way they think. Therefore, from this point of view, a study can be conducted in the future so as to find the correlation between teachers’ critical thinking and other aspects of their lives. The reason why this study should be carried out is that considering the L2 environment, students’ way of thinking is impacted by how they are treated by their teachers. Teachers are supposed to equip students with techniques through which the learning process will be facilitated and students’ creativity will be boosted, therefore, it is what helps them to be critical thinkers both in the classroom context and out of it. Another line of research that is worth being done is that diverse activities that can enhance learners’ ability of critical thinking should be categorized based on learners’ characters. In a modern educational world where individual differences are emphasized, classroom activities should be classified, regarding the learning differences of the learners. Therefore, according to Birjandi and Bagherkazemi (2010) ; Vdovina and Gaibisso (2013) , and Li and Liu (2021) , teachers’ critical thinking ability play a vital role in how students are engaged in the class.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This review was supported by the Social Science Foundation of Hebei Province of China “Testing and Research on Critical Thinking Ability of Undergraduates in Hebei Province under the Background of ‘Belt and Road’ Education Action” (Project Number: HB20YY017).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R., and Daniels, L. B. (1999). Conceptualizing critical thinking. J. Curric. Stud. 31, 285–302. doi: 10.1080/002202799183133

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Birjandi, P., and Bagherkazemi, M. (2010). The relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ critical thinking ability and their professional success. Engl. Lang. Teach. 3, 135–145. doi: 10.5539/elt.v3n2p135

Chance, P. (1986). Thinking in the Classroom: A Survey of Programs. New York, NY: Teachers college press.

Google Scholar

Davidson, B. (1998). A case for critical thinking in the English language classroom. TESOL Q. 32, 119–123. doi: 10.2307/3587906

Delmastro, A. L., and Balada, E. (2012). Modelo y estrategias para la promoción del pensamiento crítico en el aula de lenguas extranjeras. Synergies Venezuela 7, 25–37.

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., and Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions. System 101:102556. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

Dewey, J. (1933). How we Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educational Process. Boston, MA: D.C. Heath and company in English, 301.

Dörnyei, Z. (2019). Towards a better understanding of the L2 learning experience, the Cinderella of the L2 motivational self system. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 19–30. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2019.9.1.2

Elder, L., and Paul, R. (2004). Critical thinking. and the art of close reading, part IV. J. Dev. Educ. 28, 36–37.

Facione, P. A. (2011). Critical thinking: what it is and why it counts. Insight Asses. 2007, 1–23.

Finn, J. D., and Zimmer, K. S. (2012). “Student engagement: what is it? Why does it matter?,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement , eds S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (Boston, MA: Springer), 97–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_5

Han, Y., and Wang, Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL Teachers’ self-efficacy, reflection, and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 12:763234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763234

Harper, S. R., and Quaye, S. J. (2009). “Beyond sameness, with engagement and outcomes for all: an introduction,” in Student Engagement in Higher Education , eds S. R. Harper and S. J. Quaye (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–15. doi: 10.1515/9781501754586-003

Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., and Wu, J. (2021). Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang. Teach. Res. doi: 10.1177/13621688211001289

Jang, H., Reeve, J., and Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: it is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 588–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019682

Li, X., and Liu, J. (2021). Mapping the taxonomy of critical thinking ability in EFL. Think. Skills Creat. 41:100880. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100880

Li, Z. (2021). Critical thinking cultivation in Chinese learning classes for International students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Think. Skills Creat. 40:100845. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100845

Liaw, M. L. (2007). Content-based reading and writing for critical thinking skills in an EFL context. Engl. Teach. Learn. 31, 45–87. doi: 10.6330/ETL.2007.31.2.02

Marin, M. A., and Pava, L. (2017). Conceptions of critical thinking from university EFL teachers. Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 78–88. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n7p78

Meyers, C. (1986). Teaching Students to Think Critically. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Paul, R., and Elder, L. (2007). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking: Concepts & Tools. Tomales, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Rezaei, S., Derakhshan, A., and Bagherkazemi, M. (2011). Critical thinking in language education. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 2, 769–777. doi: 10.4304/jltr.2.4.769-777

Shirkhani, S., and Fahim, M. (2011). Enhancing critical thinking in foreign language learners. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.214

Skinner, E. (2016). “Engagement and disaffection as central to processes of motivational resilience and development,” in Handbook of Motivation at School , eds K. R. Wentzel and D. B. Miele (New York, NY: Routledge), 145–168. doi: 10.4324/9781315773384

Vdovina, E., and Gaibisso, L. (2013). Developing critical thinking in the English Language classroom: a lesson plan. ELTA J. 1, 54–68.

Wang, Y. L., and Guan, H. F. (2020). Exploring demotivation factors of Chinese learners of English as a foreign language based on positive psychology. Rev. Argent. Clin. Psicol. 29, 851–861. doi: 10.24205/03276716.2020.116

Wang, Y. L., and Derakhshan, A. (2021). Book review on “Professional development of CLIL teachers. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 1–4. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12353

Keywords : critical thinking, classroom engagement, foreign language learning, EFL classroom, EFT teacher

Citation: Yan Z (2021) English as a Foreign Language Teachers’ Critical Thinking Ability and L2 Students’ Classroom Engagement. Front. Psychol. 12:773138. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.773138

Received: 09 September 2021; Accepted: 19 October 2021; Published: 12 November 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Yan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ziguang Yan, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Everything Advanced Search

100 Facts About Critical Thinking

English to Spanish

Part of the 100 Facts Language Learning series

Find similar titles by category

Sorry, but no copies are available to lend at this time. Please try later.

Choosing the right learning strategy

A guide to mental strategies for effective learning.

By MIT Horizon

What does learning look like? Most people picture someone sitting at a desk with books open, intently focused on reading and highlighting. Maybe the learner is also taking a few notes. Or maybe they are staring at a computer screen. These mental images align with the general stereotype of learning activity, which is oriented toward the dedication and hard work we can observe in a diligent learner. In reality, so much of what really makes learning happen is not in those visible behaviors, it is in the mental activity a person is doing.

Beyond the motivation to focus, effective learning requires using the right mental strategies. The approach you take can significantly affect how quickly you learn, how deeply you understand, and how well you’ll be able to remember.

Your goal may determine which strategy will be most useful. Even if your goal is complete mastery, considering the sequence of approaches can also be useful. It is important to consider how to choose the right strategy at the right time, so let’s discuss some ideas to keep in mind.

Fact-based learning and automaticity

Some parts of the learning process depend upon memorizing information accurately and being able to recall it quickly. This kind of learning can serve as the foundation for more complex conceptual understanding, both by solidifying some knowledge and, perhaps even more critically, by freeing up cognitive resources to think about bigger ideas.

For example, imagine trying to solve a simple algebra problem like 6(x + 7) — 4(x — 9) = 14 if you had to recalculate 6 * 7 by adding 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 + 6 (I’m tired just looking at that!). Or trying to read a sentence, say in a foreign language, without knowing what sounds each letter makes. You’d spend a lot of your time and mental energy on really basic elements and not have the brainpower left over to actually think about the underlying meaning of what you are doing or how it relates to anything else.

We need a large base of knowledge in a given domain before we can start to think deeply about it, so how can we help ourselves learn these kinds of facts more effectively? One important principle is the idea of retrieval practice. This is the idea that, to get better at recalling information fluently, we need to practice retrieving it. This doesn’t sound revolutionary, but think about how people generally study — they often reread material and repeat important information to themselves. Unfortunately, that doesn’t best prepare them for actually getting information out. Instead, techniques like practice quizzes and flashcards can be used to practice recalling something when you need it.

Memory research has found that spacing out this kind of practice makes it more effective. We’ve all had the experience of cramming for a test, remembering some of the information the following day, and then promptly forgetting it. That is because our ability to recall information tends to decrease over time, so we need to occasionally practice for a memory to become more robust and reliable.

Ideally, with enough retrieval practice, spaced out over time, our ability to recall information becomes automatic , something that requires little to no cognitive effort, leaving us free to spend our energy focusing on developing conceptual understanding .

Conceptual understanding

While it can be impressive to rattle off specific facts from memory, the goal of learning is not just to recall pieces of information easily. We know we’ve learned well when we understand something deeply and can explain the underlying ideas and principles. To make sure that kind of learning occurs, we need to use techniques that target that level of knowledge. One surefire way to foster that kind of learning is by asking yourself questions. Research on both “self-explanation” and “elaborative interrogation” reveal a benefit for asking yourself questions such as “how?” and “why?,” and making sure you can respond in your own words and in a way that is clear to yourself.

There are a few reasons this technique is important to spotlight. For one thing, we can often trick ourselves into thinking we’ve learned something more deeply than we really have. After reading some text on a new topic, it is easy to feel like we’ve learned something from it. But if we need to explain what it is we learned, we may discover that we are missing some critical elements. For another thing, explaining in our own words can help us make connections that deepen our understanding. Creating your own, personally relevant analogies and metaphors will help you learn in a robust way. For example, someone learning about generative AI systems might come up with an explanation like “Generative AI systems are like chefs who have trained by watching tons of chefs do all sorts of things related to cooking for all different cuisines and techniques (its training data). When you ask this chef to make a new recipe (to generate a response), it draws on that knowledge to come up with its own ideas.” This is a surface-level kind of mapping, but this kind of thinking can lead to a better understanding of the underlying ideas.

Generative learning

Self-explaining and responding to those kinds of internal prompts are ways to get yourself to actively produce something with the information you’ve been learning. As discussed above, learning is not just about getting as much information as possible into your head; the measure of successful learning is being able to do something with the knowledge and skills you’ve internalized. So, practice doing that! One simple way you can do that is by creating a written summary of what you’ve covered. You can also create other kinds of visual representations, like concept maps or flow charts. And you can go beyond self-explanation (making sense of things in your own mind), to trying to teach others; often, we find the explanation that made intuitive sense and made us think “yeah, I’ve got this” falls apart when we try to verbalize it in a way that is clear to someone else. If your learning is happening as part of professional development, schedule some time to tell your colleagues about what you’ve been learning. Or, try creating a sample project that uses what you’ve learned. Even if the work isn’t perfect, the act of trying to productively use your knowledge will only help solidify it and build a foundation for next time.

The right tool

Analogies can be effective ways to improve learning, so here is one to consider: Choosing the right learning strategy is like selecting the most suitable tool for a job.

It can significantly enhance efficiency, effectiveness, and satisfaction in the learning process. Whether it’s mastering fact-based knowledge through spaced repetition and practice testing or developing a deeper conceptual understanding via elaborative interrogation and making analogies, the key lies in aligning your approach with your ultimate goals and sequencing your learning in a way that helps you achieve those goals.

Originally published at https://horizon.mit.edu/ . Part of MIT Open Learning, MIT Horizon is comprised of a continuous learning library, events, and experiences designed to help organizations keep their workforce ahead of disruptive technologies.

Choosing the right learning strategy was originally published in MIT Open Learning on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Open Learning newsletter

Dear Duolingo: How can I learn to think in a new language?

Welcome to another week of Dear Duolingo, an advice column just for learners. Catch up on past installments here .

Hey there, learners! We're back this week with one of our most popular questions. It doesn't have an easy answer, but in this post you'll find a step-by-step guide you can use for any language you're learning. Here's our question:

This week's question

Dear Duolingo, I've been learning Russian on Duolingo, and I realized that I always have to translate words from English to Russian in my head. How do I become better at thinking in Russian? Thank you, Thinking Aloud

This process of translating in your head is totally normal , especially for beginner and intermediate learners… and it sure can feel frustrating! Our brains naturally turn to the language they know best because these neural connections are the strongest. To use a new language quickly and effectively, you'll want to work towards going right from an idea to how you express it in the language you're learning—without translating first.

The truth is that learning to think in a language requires a lot of practice —and a lot of patience—but it's never too soon to start trying! This week, I describe what I like to do when I'm learning a new language, starting from when I only know a few words, so intermediate learners may want to skip the first steps. You may find other techniques that you like, too!

Ground rules

Treat this thinking exercise like a game, especially until you get the hang of it. There are three rules I like to follow—and the first is crucial.

This is harder than it seems, and at the beginning, you won't know very much! That's ok and in fact, that's the point: To build up this new thinking skill, work on building strong connections for the words you know best, the ones that come to you most easily. If you don't already know a word, then don't include it in your thinking exercise.

For most learners, using the language in conversations is the real goal, so don't just think to yourself in the language— talk to yourself in the language! If possible, find places where you can talk out loud comfortably, like at home by yourself, to your pets, on a walk in the park, etc. (You can even put on headphones to pretend that you're on the phone with someone!)

In order to learn to think in your new language:

- 🥴 You are going to feel foolish.

- 🤐 You won't be able to say very much.

- 🥱 You won't sound smart or interesting.

- 😱 You are going to make lots of mistakes . (But that's the point! Work through those mistakes! Get used to making mistakes!)

Ok, on your mark… get set… THINK!

Step 1: Think words you know

Start small and start easy. The goal of this first stage is to start building connections directly between ideas and words you know, and skip over that translation step. What you think (or say out loud) doesn't have to make sense, and it doesn't have to be sentences or even phrases. Just start thinking those isolated words!

If you were learning English, that might mean thinking: Coffee… man… girl… and… the… And that is good enough! The goal here is just to use what you know and think think think.

How to use your lessons to help: Take screenshots of words and phrases you wish came to you more easily, and dedicate a thinking session to including a few of them.

Step 2: Think little sentences

In this step, start grouping words together. You don't have to make real sentences, but maybe you think Coffee and tea instead of the individual words. The phrases or sentences can be simple, boring, and repetitive—it depends on what you've learned and what's easiest for you to pull from your memory . Remember Rule #1: Stick to what you know!

Here, the goal is to keep strengthening the connections between words and ideas and to start making what you're thinking a bit more practical. There are simple ways to do this if you're very new to the language, like by using and to connect words, and once you start learning some verbs, you can incorporate those: The coffee is here, the tea is here, the man is here, the girl is here .

As you progress through your lessons, you'll probably find that you move back and forth between steps 1 and 2: Maybe for brand new words, you like to practice thinking them individually, and you eventually start including them in the phrases and sentences you know. As you study the language longer, you'll be able to include brand-new words right into sentences and phrases.

How to use your lessons to help: When you encounter verbs or phrases that are especially relevant or interesting to you, screenshot them to include in your thinking practice. You can also do this to record phrases that you can make a lot of use of, like May I have a ___? or I'd like to ___.

Even if your goal is thinking in the new language, you can practice other skills to help. I like to write out little sentences and dialogues —also using only what I already know (Rule #1!)—to help me practice putting words together in phrases.

Step 3: Describe everything around you

Once you have more vocabulary and grammar under your belt, start narrating things to yourself. You won't sound interesting, but that's not the point 😅 Remember you want to build connections in your brain and practice thinking . Imagine it like a sport: If you're training to play tennis, you'll do lots of exercises and drills that look pretty different from what playing a real tennis match looks like. But you're building up the muscles and skills to do the real thing!

In Step 3, you'll describe actual things you see, or what you're doing, or what you imagine doing. Since you want to stick to the words you already know, you might be making a lot of this up, and it might be repetitive: I am here, I am at home, I have a bed, I have a cat, This is my bed, This is my cat, etc . Try to go on as long as you can! As you get more comfortable with these basics, you'll find it easier to include new words and make longer sentences.

How to use your lessons to help: Do a lesson (or two!) before your thinking session and get inspiration from the vocabulary and grammar you see. You can challenge yourself to think about the specific topic of the lesson, or to target your thinking to particular grammatical structures from the lesson.

Step 4: Do this as much as possible!

This isn't really a separate step—you can do this even when you only know a few words. It's great to take advantage of speaking out loud whenever possible, but you probably have even more opportunities to do thinking practice. You can quietly think words, phrases, and sentences to yourself on the bus, while walking to your car, while washing your hands, while waiting in line, while in the elevator… just about any time!

It’s like training a muscle: You need to build muscle memory, and your brain needs to get used to putting together the ideas, words, and grammar you'll need to communicate. For most learners, it's simply unrealistic to expect to jump to full sentences about relevant topics. But you can get there with practice and by starting small!

Step 5: Reflect on what's missing

Once you're at the sentence and description stages, start noticing what words and phrases you'd like to pull from your memory more easily. Keep track of them, maybe on your phone or in a notebook, and write down their equivalents when you come across them in your lessons. That way, when you're ready for another little thinking session, you can refer back to your list and include some new items in your thinking.

One thing that's nice about this low-pressure thinking technique is that it makes it easy to focus on particular grammar or vocabulary that you want extra practice with. For example, if you'll be using the new language at an upcoming family gathering, maybe you want to practice describing a recent trip—so you can focus your thinking on the past tense. What verbs do you know the past tense in really well? Which verbs have irregular conjugations or they just don't come to you as quickly?

How to use your lessons to help: Doing Legendary levels or practice for older units is a great way to gather up the vocabulary and grammar you aren't including in your thinking yet.

It's a lot to think about!

Incorporate these thinking exercises into your daily practice and spend lots of time on Step 3 to get your brain used to thinking about the real objects, routines, and needs in your daily life. Just like learning vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation, learning to think in your new language takes a long time, so chip away at it a little every day!

For more answers to your language and learning questions, get in touch with us by emailing [email protected] .

Related Posts All Posts

Essential english vocabulary for u.s. restaurants, how do you use inclusive language in spanish.

MIT Sloan Management Review Article on Critical Thinking and Cognitive Flexibility

- MIT Sloan Management Review

What is the best way for a modern executive to process information? How do managers and business leaders gather and interpret information effectively?

In this collection of articles, you'll learn:

- How to use technology-enabled insights to make informed decisions and predictions when dealing with uncertainty and complex issues

- The dangers of projection and making assumptions during decision making and negotiation processes

- How to utilize technology to create “better selves” within business

- The benefits of data and experimentation over intuition, assumptions, or perceived expertise

- How to identify and interpret weak or indistinct indicators of change

Learn more about MIT SMR.

In this Book

- Introduction

- Building a More Intelligent Enterprise

- How Assumptions of Consensus Undermine Decision Making