Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What Are Research Objectives and How to Write Them (with Examples)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Research is at the center of everything researchers do, and setting clear, well-defined research objectives plays a pivotal role in guiding scholars toward their desired outcomes. Research papers are essential instruments for researchers to effectively communicate their work. Among the many sections that constitute a research paper, the introduction plays a key role in providing a background and setting the context. 1 Research objectives, which define the aims of the study, are usually stated in the introduction. Every study has a research question that the authors are trying to answer, and the objective is an active statement about how the study will answer this research question. These objectives help guide the development and design of the study and steer the research in the appropriate direction; if this is not clearly defined, a project can fail!

Research studies have a research question, research hypothesis, and one or more research objectives. A research question is what a study aims to answer, and a research hypothesis is a predictive statement about the relationship between two or more variables, which the study sets out to prove or disprove. Objectives are specific, measurable goals that the study aims to achieve. The difference between these three is illustrated by the following example:

- Research question : How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

- Research hypothesis : Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

- Research objective : To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

This article discusses the importance of clear, well-thought out objectives and suggests methods to write them clearly.

What is the introduction in research papers?

Research objectives are usually included in the introduction section. This section is the first that the readers will read so it is essential that it conveys the subject matter appropriately and is well written to create a good first impression. A good introduction sets the tone of the paper and clearly outlines the contents so that the readers get a quick snapshot of what to expect.

A good introduction should aim to: 2,3

- Indicate the main subject area, its importance, and cite previous literature on the subject

- Define the gap(s) in existing research, ask a research question, and state the objectives

- Announce the present research and outline its novelty and significance

- Avoid repeating the Abstract, providing unnecessary information, and claiming novelty without accurate supporting information.

Why are research objectives important?

Objectives can help you stay focused and steer your research in the required direction. They help define and limit the scope of your research, which is important to efficiently manage your resources and time. The objectives help to create and maintain the overall structure, and specify two main things—the variables and the methods of quantifying the variables.

A good research objective:

- defines the scope of the study

- gives direction to the research

- helps maintain focus and avoid diversions from the topic

- minimizes wastage of resources like time, money, and energy

Types of research objectives

Research objectives can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives . 4 General objectives state what the research expects to achieve overall while specific objectives break this down into smaller, logically connected parts, each of which addresses various parts of the research problem. General objectives are the main goals of the study and are usually fewer in number while specific objectives are more in number because they address several aspects of the research problem.

Example (general objective): To investigate the factors influencing the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

Example (specific objective): To assess the influence of firm size on the financial performance of firms listed in the New York Stock Exchange market.

In addition to this broad classification, research objectives can be grouped into several categories depending on the research problem, as given in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of research objectives

| Exploratory | Explores a previously unstudied topic, issue, or phenomenon; aims to generate ideas or hypotheses |

| Descriptive | Describes the characteristics and features of a particular population or group |

| Explanatory | Explains the relationships between variables; seeks to identify cause-and-effect relationships |

| Predictive | Predicts future outcomes or events based on existing data samples or trends |

| Diagnostic | Identifies factors contributing to a particular problem |

| Comparative | Compares two or more groups or phenomena to identify similarities and differences |

| Historical | Examines past events and trends to understand their significance and impact |

| Methodological | Develops and improves research methods and techniques |

| Theoretical | Tests and refines existing theories or helps develop new theoretical perspectives |

Characteristics of research objectives

Research objectives must start with the word “To” because this helps readers identify the objective in the absence of headings and appropriate sectioning in research papers. 5,6

- A good objective is SMART (mostly applicable to specific objectives):

- Specific—clear about the what, why, when, and how

- Measurable—identifies the main variables of the study and quantifies the targets

- Achievable—attainable using the available time and resources

- Realistic—accurately addresses the scope of the problem

- Time-bound—identifies the time in which each step will be completed

- Research objectives clarify the purpose of research.

- They help understand the relationship and dissimilarities between variables.

- They provide a direction that helps the research to reach a definite conclusion.

How to write research objectives?

Research objectives can be written using the following steps: 7

- State your main research question clearly and concisely.

- Describe the ultimate goal of your study, which is similar to the research question but states the intended outcomes more definitively.

- Divide this main goal into subcategories to develop your objectives.

- Limit the number of objectives (1-2 general; 3-4 specific)

- Assess each objective using the SMART

- Start each objective with an action verb like assess, compare, determine, evaluate, etc., which makes the research appear more actionable.

- Use specific language without making the sentence data heavy.

- The most common section to add the objectives is the introduction and after the problem statement.

- Add the objectives to the abstract (if there is one).

- State the general objective first, followed by the specific objectives.

Formulating research objectives

Formulating research objectives has the following five steps, which could help researchers develop a clear objective: 8

- Identify the research problem.

- Review past studies on subjects similar to your problem statement, that is, studies that use similar methods, variables, etc.

- Identify the research gaps the current study should cover based on your literature review. These gaps could be theoretical, methodological, or conceptual.

- Define the research question(s) based on the gaps identified.

- Revise/relate the research problem based on the defined research question and the gaps identified. This is to confirm that there is an actual need for a study on the subject based on the gaps in literature.

- Identify and write the general and specific objectives.

- Incorporate the objectives into the study.

Advantages of research objectives

Adding clear research objectives has the following advantages: 4,8

- Maintains the focus and direction of the research

- Optimizes allocation of resources with minimal wastage

- Acts as a foundation for defining appropriate research questions and hypotheses

- Provides measurable outcomes that can help evaluate the success of the research

- Determines the feasibility of the research by helping to assess the availability of required resources

- Ensures relevance of the study to the subject and its contribution to existing literature

Disadvantages of research objectives

Research objectives also have few disadvantages, as listed below: 8

- Absence of clearly defined objectives can lead to ambiguity in the research process

- Unintentional bias could affect the validity and accuracy of the research findings

Key takeaways

- Research objectives are concise statements that describe what the research is aiming to achieve.

- They define the scope and direction of the research and maintain focus.

- The objectives should be SMART—specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound.

- Clear research objectives help avoid collection of data or resources not required for the study.

- Well-formulated specific objectives help develop the overall research methodology, including data collection, analysis, interpretation, and utilization.

- Research objectives should cover all aspects of the problem statement in a coherent way.

- They should be clearly stated using action verbs.

Frequently asked questions on research objectives

Q: what’s the difference between research objectives and aims 9.

A: Research aims are statements that reflect the broad goal(s) of the study and outline the general direction of the research. They are not specific but clearly define the focus of the study.

Example: This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.

Research objectives focus on the action to be taken to achieve the aims. They make the aims more practical and should be specific and actionable.

Example: To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation.

Q: What are the examples of research objectives, both general and specific?

A: Here are a few examples of research objectives:

- To identify the antiviral chemical constituents in Mumbukura gitoniensis (general)

- To carry out solvent extraction of dried flowers of Mumbukura gitoniensis and isolate the constituents. (specific)

- To determine the antiviral activity of each of the isolated compounds. (specific)

- To examine the extent, range, and method of coral reef rehabilitation projects in five shallow reef areas adjacent to popular tourist destinations in the Philippines.

- To investigate species richness of mammal communities in five protected areas over the past 20 years.

- To evaluate the potential application of AI techniques for estimating best-corrected visual acuity from fundus photographs with and without ancillary information.

- To investigate whether sport influences psychological parameters in the personality of asthmatic children.

Q: How do I develop research objectives?

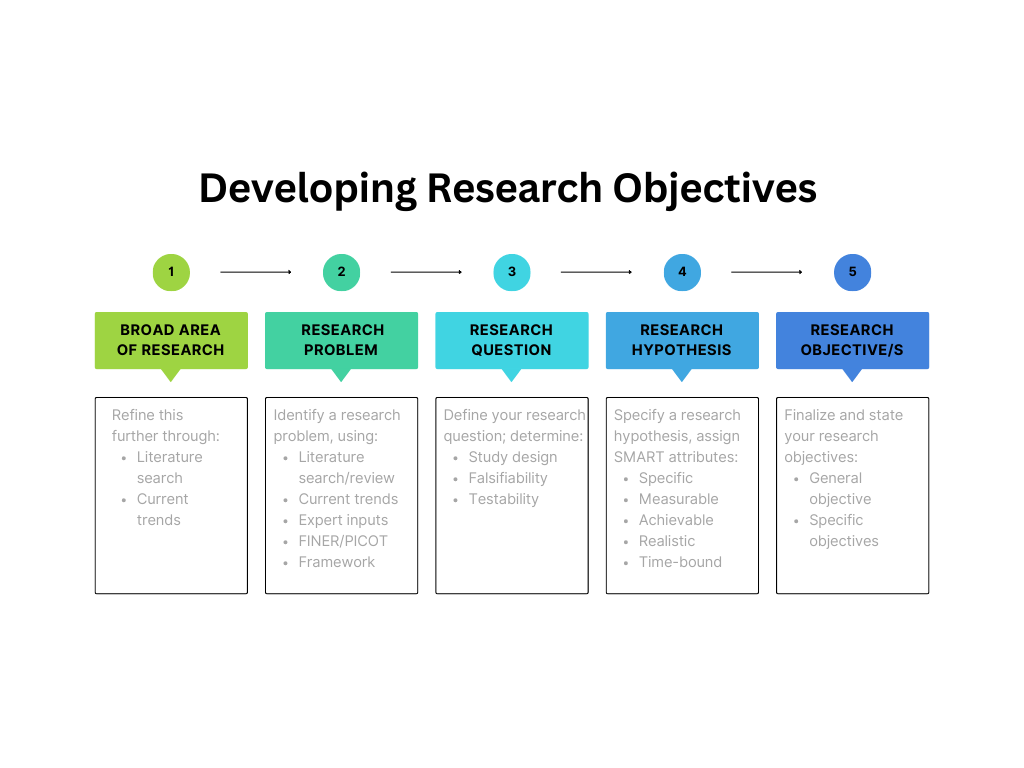

A: Developing research objectives begins with defining the problem statement clearly, as illustrated by Figure 1. Objectives specify how the research question will be answered and they determine what is to be measured to test the hypothesis.

Q: Are research objectives measurable?

A: The word “measurable” implies that something is quantifiable. In terms of research objectives, this means that the source and method of collecting data are identified and that all these aspects are feasible for the research. Some metrics can be created to measure your progress toward achieving your objectives.

Q: Can research objectives change during the study?

A: Revising research objectives during the study is acceptable in situations when the selected methodology is not progressing toward achieving the objective, or if there are challenges pertaining to resources, etc. One thing to keep in mind is the time and resources you would have to complete your research after revising the objectives. Thus, as long as your problem statement and hypotheses are unchanged, minor revisions to the research objectives are acceptable.

Q: What is the difference between research questions and research objectives? 10

| Broad statement; guide the overall direction of the research | Specific, measurable goals that the research aims to achieve |

| Identify the main problem | Define the specific outcomes the study aims to achieve |

| Used to generate hypotheses or identify gaps in existing knowledge | Used to establish clear and achievable targets for the research |

| Not mutually exclusive with research objectives | Should be directly related to the research question |

| Example: | Example: |

Q: Are research objectives the same as hypotheses?

A: No, hypotheses are predictive theories that are expressed in general terms. Research objectives, which are more specific, are developed from hypotheses and aim to test them. A hypothesis can be tested using several methods and each method will have different objectives because the methodology to be used could be different. A hypothesis is developed based on observation and reasoning; it is a calculated prediction about why a particular phenomenon is occurring. To test this prediction, different research objectives are formulated. Here’s a simple example of both a research hypothesis and research objective.

Research hypothesis : Employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

Research objective : To assess whether employees who arrive at work earlier are more productive.

To summarize, research objectives are an important part of research studies and should be written clearly to effectively communicate your research. We hope this article has given you a brief insight into the importance of using clearly defined research objectives and how to formulate them.

- Farrugia P, Petrisor BA, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Can J Surg. 2010 Aug;53(4):278-81.

- Abbadia J. How to write an introduction for a research paper. Mind the Graph website. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://mindthegraph.com/blog/how-to-write-an-introduction-for-a-research-paper/

- Writing a scientific paper: Introduction. UCI libraries website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249903

- Research objectives—Types, examples and writing guide. Researchmethod.net website. Accessed June 17, 2023. https://researchmethod.net/research-objectives/#:~:text=They%20provide%20a%20clear%20direction,track%20and%20achieve%20their%20goals .

- Bartle P. SMART Characteristics of good objectives. Community empowerment collective website. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://cec.vcn.bc.ca/cmp/modules/pd-smar.htm

- Research objectives. Studyprobe website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.studyprobe.in/2022/08/research-objectives.html

- Corredor F. How to write objectives in a research paper. wikiHow website. Accessed June 18, 2023. https://www.wikihow.com/Write-Objectives-in-a-Research-Proposal

- Research objectives: Definition, types, characteristics, advantages. AccountingNest website. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.accountingnest.com/articles/research/research-objectives

- Phair D., Shaeffer A. Research aims, objectives & questions. GradCoach website. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://gradcoach.com/research-aims-objectives-questions/

- Understanding the difference between research questions and objectives. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://board.researchersjob.com/blog/research-questions-and-objectives

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Independent Publishing in Academia?

Article Processing Charges: Impact on Open Access Publishing

- Scroll to top

- Light Dark Light Dark

Cart review

No products in the cart.

7 Essential Steps: How to Write a Research Brief That Gets Results

- Author Survey Point Team

- Published February 17, 2024

In this blog, we’ll explore seven essential steps to learn how to write a research brief that not only guides your project but also resonates with your audience. Research briefs are the unsung heroes of successful projects. Whether you’re a seasoned researcher or a newbie, crafting a well-structured brief can significantly impact the quality of your work.

Crafting a research brief that yields results is crucial. Explore the seven essential steps to write an effective research brief, ensuring success in your projects. Learn from experts and avoid common pitfalls.

Embarking on a research journey requires a well-crafted roadmap. A research brief serves as the compass, guiding you through the intricate terrain of data and insights. In this article, we will explore the seven essential steps to create a research brief that not only meets but exceeds expectations, ensuring the desired results.

Table of Contents

The Importance of Research Briefs

Why Research Briefs Matter

Research briefs are the cornerstone of successful projects. They set the tone, define objectives, and guide researchers toward meaningful outcomes. A well-structured brief not only saves time but also ensures the collected data aligns with the project goals.

How to Write a Research Brief: Understanding Your Objective

Defining Clear Research Goals

The first step in creating a research brief is understanding the project’s objective. Clearly define what you aim to achieve, ensuring every subsequent decision aligns with this overarching goal. Clarity at this stage is paramount.

Target Audience Analysis

Identifying and Understanding Your Audience

Knowing your audience is key to effective communication. Dive deep into demographic details, preferences, and behaviors. Tailor your research brief to resonate with the intended audience, enhancing its impact.

Crafting a Clear Research Question

Formulating Effective Research Queries

A well-defined research question is the compass that guides your entire project. Craft a question that is clear, concise, and directly aligns with your objectives. This foundational step ensures focused and purposeful research.

Literature Review

Building a Solid Foundation

Before venturing into uncharted territories, review existing literature. This not only provides valuable insights but also prevents redundancy. Acknowledge the work of others and identify gaps your research can fill.

Research Methodology

Choosing the Right Approach

Selecting the appropriate research methodology is pivotal. Whether qualitative or quantitative, the chosen approach should align with your objectives. Justify your choice, considering the nature of your research question.

How to Write a Research Brief: Data Collection

Ensuring Quality Information

Collecting data is where the rubber meets the road. Implement a robust data collection strategy, ensuring the information gathered is relevant, accurate, and aligns with your research question. Quality over quantity is the mantra.

Analysis and Interpretation

Extracting Meaningful Insights

Analysis is the heart of research. Interpret the collected data, drawing meaningful conclusions. Your insights should directly contribute to answering your research question and, consequently, achieving your objective.

Crafting a Compelling Title

Making Your Research Brief Stand Out

A captivating title is the first impression your research brief makes. It should be concise, intriguing, and reflective of the study’s essence. Crafting a compelling title sets the stage for your audience’s engagement.

The Power of Effective Communication

Conveying Your Message Clearly

Beyond the data, effective communication is crucial. Present your findings in a clear, concise manner. Utilize visuals, charts, and graphs to enhance understanding. Make your research brief accessible to a broad audience.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Mistakes That Can Derail Your Research

Avoiding common pitfalls is as important as following the right steps. Identify and steer clear of potential pitfalls that could compromise the integrity and effectiveness of your research brief. Learn from others’ mistakes to enhance your own success.

Real-life Success Stories

Learnings from Notable Research Briefs

Drawing inspiration from successful research briefs can provide valuable insights. Explore real-life success stories, understand the strategies employed, and apply these lessons to elevate the impact of your own research briefs.

How to Write a Research Brief: FAQ

Can I write multiple research questions? Certainly, but ensure they all align with your main objective. Quality over quantity is crucial in research.

How do I choose between qualitative and quantitative methods? Consider the nature of your research question. Qualitative methods delve into depth, while quantitative methods focus on breadth.

Is a literature review necessary for all research briefs? Yes, a literature review establishes the context for your research and prevents duplication of efforts.

How do I make my title captivating? A captivating title is concise, intriguing, and reflective of your study’s essence. Use language that sparks curiosity.

What are common pitfalls in research briefs? Common pitfalls include unclear objectives, biased data collection, and inadequate analysis. Be vigilant to avoid these pitfalls.

Can I use the same research methodology for every project? Adapt your research methodology to align with each project’s unique objectives. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach.

Wrapping Up the Research Brief Journey In conclusion, crafting a research brief that gets results requires a strategic approach. By following the seven essential steps outlined in this article, you can navigate the complexities of research with confidence. Remember, a well-prepared brief not only guides your journey but ensures the destination is one of success.

Survey Point Team

Related posts.

- Posted by Survey Point Team

How K12 Data Analytics Can Help You Achieve Your School’s Goals in 2024

Discover Why Data Science is Right for You: 7 Compelling Reasons to Dive In Today

Python vs R for Data Analysis: Which One Should Learn in 2024?

- Business & Enterprise

- Education, Learning & Skills

- Energy & Environment

- Financial Services

- Health & Wellbeing

- Higher Education

- Work & Welfare

- Behavioural insights

- Business Spotlight – IFF’s business omnibus

- Customer experience research

- Customer satisfaction measurement

- National statistics and complex surveys

- Stakeholder research

- Tenant satisfaction measures

- Our approach

- Trusted partner

- Equality, diversity & inclusion at IFF

- Sustainability at IFF

- Charity giving

- Meet the team

- News & resources

- Case studies

How to write an effective research brief

Whether you’re launching a simple survey or planning a large-scale project the quality of your brief will hugely impact on the value you get from the research. While it can take a little time and effort creating a research brief, it will undoubtedly be time well spent – getting you better results and return on your investment and saving you valuable resources on further clarification. At best, a poor brief will be a time drain on you and your team. At worst, the findings will fail to meet your objectives, costing you time and money.

We’ve seen a lot of research briefs over the years. Some of which have been well thought through and clear, helping us prepare a detailed proposal and deliver an effective project and subsequent results. And others which have been not so good, lacking clarity or detail.

Using this experience, we’ve put together a ‘how to’ guide on writing an effective research brief, to help you ensure success on your next project.

1. Preparation is key

As with any project, before you start it’s crucial you think through what you want and need to deliver. Here are some things you should consider:

- Why are you conducting the research? What exactly are you looking to understand?

- Who are you looking to understand better? Who do you need to speak to answer your research questions?

- Who are your internal stakeholders? Have you discussed the project needs with the people in your organisation who will use the findings or who are invested in the research?

- How will the findings be used?

- When do you need the findings?

- Have you agreed a budget with either your procurement team, or the relevant person in your organisation?

2. Be clear on your objectives

This is one of the most important parts of your brief to convey to the reader what you want out of the project and ensure you get results which deliver.

Projects should have around three or four overarching aims which set out what the project ultimately wants to achieve.

These might be things like:

- Assess the impact of……

- Examine views of…..

- Evaluate the effectiveness of….

In addition to project objectives, you should also include the key questions you want the research to answer. These should support you in meeting the aims of the research.

For example, if the project aim is to assess the impact of an intervention, your research questions might include:

- Who did the intervention target?

- What did the project deliver?

- What elements were successful, and why?

- What were the main enablers and barriers?

3. Remember your audience

Research agencies or organisations who will be responding to your brief might not know anything about your business. So, make sure you include enough background information in your brief to enable them to understand your needs and deliver effectively. And avoid use of jargon or acronyms which could lead to errors or confusion.

4. Structure your research brief

Before you start to populate your brief it’s worth considering all the information and sections you need to include, to structure your thinking and ensure you don’t miss anything important.

This might include some, or all, of the following:

- Background info

- Introduction

- Aims and objectives

- Research Question(s)

- Issues / Risks

- Methodology

- Timing and Outputs

- Project Management

5. Make it thorough, yet succinct

While it’s crucial to include all the relevant information to enable bidders to respond effectively, no one wants to read reams and reams of information. To avoid the key information getting lost in the details use annexes to add supplementary information which could be useful.

6. Consider how prescriptive you want to be on the methodology

The extent to which you want to specify the methodology will depend on the project you aim to deliver. There are benefits and risks to being overly prescriptive or offering free reign. If you outline in precise detail how you want the research to be conducted, you will hamper any original ideas from those invited to tender and might limit the impact on the research. Whereas, if you’re less prescriptive, allowing room for creativity, you risk not getting the project or results you want, or receiving proposals on a scale which you can’t resource.

Generally, it is useful to allow those invited to tender some scope to develop the methodology they propose to use. Exceptions might be where previous work has to be very precisely replicated or some other very precise commitment about the nature of findings has been given to stakeholders.

7. Define your timelines

As a minimum, you need to include when you want the project to start and end. But you should also include the timetable for procurement. When planning this, don’t underestimate the time and resource needed to run a procurement exercise. Make sure your evaluators are available when you need them and have enough time blocked out in their diary.

You’ll likely also want to include milestones for when you expect outputs to be delivered, such as deadlines for a draft report (providing opportunity for review and feedback) and the final report; allowing sufficient time between the two to enable your stakeholders to consult, for you to feedback and for the contractor to revise the report.

8. Set expectations on cost

You will most likely have budgetary constraints, with a figure for what you are prepared to spend. To save you and your bidders time, and to set realistic expectations, you should include an indication within your brief. This will prevent you receiving proposals which are way out of the ballpark; enable bidders to plan a project which delivers on (or at least close to) budget; and will prevent any nasty surprises, further down the line.

By following these tips you’ll be well on your way to creating an effective research brief which delivers on time and on budget.

If you’d like more guidance download our “step-by-step” guide, which includes a template and information for what to include in each section to ensure success.

Download the guide now.

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Handy Tips To Write A Clear Research Objectives With Examples

Introduction.

Research objectives play a crucial role in any research study. They provide a clear direction and purpose for the research, guiding the researcher in their investigation. Understanding research objectives is essential for conducting a successful study and achieving meaningful results.

In this comprehensive review, we will delve into the definition of research objectives, exploring their characteristics, types, and examples. We will also discuss the relationship between research objectives and research questions, as well as provide insights into how to write effective research objectives. Additionally, we will examine the role of research objectives in research methodology and highlight the importance of them in a study. By the end of this review, you will have a comprehensive understanding of research objectives and their significance in the research process.

Definition of Research Objectives: What Are They?

A research objective is defined as a clear and concise statement that outlines the specific goals and aims of a research study. These objectives are designed to be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART), ensuring they provide a structured pathway to accomplishing the intended outcomes of the project. Each objective serves as a foundational element that summarizes the purpose of your study, guiding the research activities and helping to measure progress toward the study’s goals. Additionally, research objectives are integral components of the research framework , establishing a clear direction that aligns with the overall research questions and hypotheses. This alignment helps to ensure that the study remains focused and relevant, facilitating the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of data.

Characteristics of Effective Research Objectives

Characteristics of research objectives include:

- Specific: Research objectives should be clear about the what, why, when, and how of the study.

- Measurable: Research objectives should identify the main variables of the study that can be measured or observed.

- Relevant: Research objectives should be relevant to the research topic and contribute to the overall understanding of the subject.

- Feasible: Research objectives should be achievable within the constraints of time, resources, and expertise available.

- Logical: Research objectives should follow a logical sequence and build upon each other to achieve the overall research goal.

- Observable: Research objectives should be observable or measurable in order to assess the progress and success of the research project.

- Unambiguous: Research objectives should be clear and unambiguous, leaving no room for interpretation or confusion.

- Measurable: Research objectives should be measurable, allowing for the collection of data and analysis of results.

By incorporating these characteristics into research objectives, researchers can ensure that their study is focused, achievable, and contributes to the body of knowledge in their field.

Types of Research Objectives

Research objective can be broadly classified into general and specific objectives. General objectives are broad statements that define the overall purpose of the research. They provide a broad direction for the study and help in setting the context. Specific objectives, on the other hand, are detailed objectives that describe what will be researched during the study. They are more focused and provide specific outcomes that the researcher aims to achieve. Specific objectives are derived from the general objectives and help in breaking down the research into smaller, manageable parts. The specific objectives should be clear, measurable, and achievable. They should be designed in a way that allows the researcher to answer the research questions and address the research problem.

In addition to general and specific objectives, research objective can also be categorized as descriptive or analytical objectives. Descriptive objectives focus on describing the characteristics or phenomena of a particular subject or population. They involve surveys, observations, and data collection to provide a detailed understanding of the subject. Analytical objectives, on the other hand, aim to analyze the relationships between variables or factors. They involve data analysis and interpretation to gain insights and draw conclusions.

Both descriptive and analytical objectives are important in research as they serve different purposes and contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

Examples of Research Objectives

Here are some examples of research objectives in different fields:

1. Objective: To identify key characteristics and styles of Renaissance art.

This objective focuses on exploring the characteristics and styles of art during the Renaissance period. The research may involve analyzing various artworks, studying historical documents, and interviewing experts in the field.

2. Objective: To analyze modern art trends and their impact on society.

This objective aims to examine the current trends in modern art and understand how they influence society. The research may involve analyzing artworks, conducting surveys or interviews with artists and art enthusiasts, and studying the social and cultural implications of modern art.

3. Objective: To investigate the effects of exercise on mental health.

This objective focuses on studying the relationship between exercise and mental health. The research may involve conducting experiments or surveys to assess the impact of exercise on factors such as stress, anxiety, and depression.

4. Objective: To explore the factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions in the fashion industry.

This objective aims to understand the various factors that influence consumers’ purchasing decisions in the fashion industry. The research may involve conducting surveys, analyzing consumer behavior data, and studying the impact of marketing strategies on consumer choices.

5. Objective: To examine the effectiveness of a new drug in treating a specific medical condition.

This objective focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of a newly developed drug in treating a particular medical condition. The research may involve conducting clinical trials, analyzing patient data, and comparing the outcomes of the new drug with existing treatment options.

These examples demonstrate the diversity of research objectives across different disciplines. Each objective is specific, measurable, and achievable, providing a clear direction for the research study.

Aligning Research Objectives with Research Questions

Research objectives and research questions are essential components of a research project. Research objective describe what you intend your research project to accomplish. They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and provide a clear direction for the research. Research questions, on the other hand, are the starting point of any good research. They guide the overall direction of the research and help identify and focus on the research gaps .

The main difference between research questions and objectives is their form. Research questions are stated in a question form, while objectives are specific, measurable, and achievable goals that you aim to accomplish within a specified timeframe. Research questions are broad statements that provide a roadmap for the research, while objectives break down the research aim into smaller, actionable steps.

Research objectives and research questions work together to form the ‘golden thread’ of a research project. The research aim specifies what the study will answer, while the objectives and questions specify how the study will answer it. They provide a clear focus and scope for the research project, helping researchers stay on track and ensure that their study is meaningful and relevant.

When writing research objectives and questions, it is important to be clear, concise, and specific. Each objective or question should address a specific aspect of the research and contribute to the overall goal of the study. They should also be measurable, meaning that their achievement can be assessed and evaluated. Additionally, research objectives and questions should be achievable within the given timeframe and resources of the research project. By clearly defining the objectives and questions, researchers can effectively plan and execute their research, leading to valuable insights and contributions to the field.

Guidelines for Writing Clear Research Objectives

Writing research objective is a crucial step in any research project. The objectives provide a clear direction and purpose for the study, guiding the researcher in their data collection and analysis. Here are some tips on how to write effective research objective:

1. Be clear and specific

Research objective should be written in a clear and specific manner. Avoid vague or ambiguous language that can lead to confusion. Clearly state what you intend to achieve through your research.

2. Use action verbs

Start your research objective with action verbs that describe the desired outcome. Action verbs such as ‘investigate’, ‘analyze’, ‘compare’, ‘evaluate’, or ‘identify’ help to convey the purpose of the study.

3. Align with research questions or hypotheses

Ensure that your research objectives are aligned with your research questions or hypotheses. The objectives should address the main goals of your study and provide a framework for answering your research questions or testing your hypotheses.

4. Be realistic and achievable

Set research objectives that are realistic and achievable within the scope of your study. Consider the available resources, time constraints, and feasibility of your objectives. Unrealistic objectives can lead to frustration and hinder the progress of your research.

5. Consider the significance and relevance

Reflect on the significance and relevance of your research objectives. How will achieving these objectives contribute to the existing knowledge or address a gap in the literature? Ensure that your objectives have a clear purpose and value.

6. Seek feedback

It is beneficial to seek feedback on your research objectives from colleagues, mentors, or experts in your field. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improving the clarity and effectiveness of your objectives.

7. Revise and refine

Research objectives are not set in stone. As you progress in your research, you may need to revise and refine your objectives to align with new findings or changes in the research context. Regularly review and update your objectives to ensure they remain relevant and focused.

By following these tips, you can write research objectives that are clear, focused, and aligned with your research goals. Well-defined objectives will guide your research process and help you achieve meaningful outcomes.

The Role of Research Objectives in Research Methodology

Research objectives play a crucial role in the research methodology . In research methodology, research objectives are formulated based on the research questions or problem statement. These objectives help in defining the scope and focus of the study, ensuring that the research is conducted in a systematic and organized manner.

The research objectives in research methodology act as a roadmap for the research project. They help in identifying the key variables to be studied, determining the research design and methodology, and selecting the appropriate data collection methods .

Furthermore, research objectives in research methodology assist in evaluating the success of the study. By setting clear objectives, researchers can assess whether the desired outcomes have been achieved and determine the effectiveness of the research methods employed. It is important to note that research objectives in research methodology should be aligned with the overall research aim. They should address the specific aspects or components of the research aim and provide a framework for achieving the desired outcomes.

Understanding The Dynamic of Research Objectives in Your Study

The research objectives of a study play a crucial role in guiding the research process, ensuring that the study is focused, purposeful, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field. It is important to note that the research objectives may evolve or change as the study progresses. As new information is gathered and analyzed, the researcher may need to revise the objectives to ensure that they remain relevant and achievable.

In summary, research objectives are essential components in writing an effective research paper . They provide a roadmap for the research process, guiding the researcher in their investigation and helping to ensure that the study is purposeful and meaningful. By understanding and effectively utilizing research objectives, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their research endeavors.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Writing An Accurate Conclusion In A Research Study: 5 Step-By-Step Guide

Writing An Abstract for Research Paper: Best Practices!

Wondering How To Write a Robust and Effective Problem Statement In Research Study? This Article Has It All!

Ultimate Guide to Boosting Your Creativity To Generate Great Research Ideas!

The Intricate Differences Between Research Papers, Theses, And Dissertations

Drafting Exceptional Research Abstracts: 7 Know-How!

Mastering Reference Management Tools for Effective Research Writing

Academic Integrity : Best Practice Of Upholding Honor in Research And Education

How to write a great qualitative research brief

It’s fast becoming the norm that clients come to us without a written brief. Sure, they know what they want to achieve, what their objectives are, but they don’t know how to write a qualitative research brief (or they’ve not got the time!).

I’m always the first to put my hands up and offer to help them write it. It takes the pressure off them and means that you are more immersed in the project, so it’s a win-win.

I’m going to share with you my thoughts on what makes a good qualitative research brief and why it’s so necessary to get it right (in case that isn’t obvious enough). Start with the wrong brief and you’re heading down the wrong path from the get-go. Not only will you set the wrong course, but you’ll probably cost the project incorrectly and even propose the wrong methods. There’s a handy briefing template you can download at the end of this blog that will help you focus on key points.

Before I dive into the specifics, here are three key things to consider:

Framing and re-framing

First and foremost, the brief frames the client’s problem or challenge, and it establishes the fundamental question(s) they want answering. More often than not, research briefs are framed through the lens of the business, when in fact, they should be through the lens of the consumer. Reframing is perhaps better to be done by the researcher/agency as they can see outside the business more readily than the client. The phrase, ‘wood for the trees’ is poignant.

Short and simple

Research briefs don’t need to be long and exhaustive. In fact, the shorter and more precise the better. This often shows the brief has been thought about and refined. A shorter brief also makes it easier for stakeholders of all kinds to ‘get it’.

Adopt the right tone

Like any written document that has its readers, a qualitative research brief needs to adopt the appropriate tone, be it a formal business one or a more relaxed consumer-friendly version. Most businesses are jam-packed with technical jargon so handle this with care and remove where possible so that everyone can be sure of being (and staying) on the same page.

OK, now to the details. Here’s what your qualitative research brief should include:

Provide a summary of the primary business the client is in, and clearly explain why the business exists, what its mission and vision are, and what the competitive set are. You should also look to include information about which markets the study should explore.

What research pre-exists and is shareable

We sometimes call this a ‘research amnesty’. It is vitally important we have sight of any pre-existing research so as not to duplicate any findings that already exist. No matter what form the research/insight is, throw it at us and we’ll read through it to create a detailed picture of the business/brand.

Research objectives

This is where you set about describing what the core research task is. For example, the research objective might be to find out what your customers think of your recently launched product or service. Set out specific research objectives to clarify the key questions you need to answer and the information you need to gather to address the challenge.

Now you’re starting to motor and get into the details around the questions that need to be answered, or the spaces you’re going to explore. Remember, qualitative research helps understand why people do what they do, so write the objectives through that lens and think about the behaviours, motivations, thoughts and feelings you want to understand.

Business objectives

Driving their research objective may be a more strategic business objective that is framed differently. Quite simply, it outlines why you are being asked to do this. For example, does the research support modifying a service or product or intended to deliver growth?

Stakeholder team

Which parties/departments (internal and/or external) will be involved with and have a vested interest in this research study. They might be a sponsor, collaborator or a third-party that needs an actionable outcome. Detail their requirements and comment on their level and method of involvement.

Target audience to research

Who do you need to talk to?

Are they current customers, lapsed customers or those of a competitor? Are demographics relevant, such as age, gender, income, occupation, location, company size, etc? Is social profiling relevant, or their personal attributes and proficiencies?

The target audience could include:

- Who you want researched and how many (sample size)?

- Source: Will the client be providing a customer list, or do you need to recommend the best way to source respondents such as panels, free-finding or social media?

Methodology

Based on the objectives, which qualitative research methods are best deployed and why. Are you proposing a combination of methods as is usually the case? Should the research be conducted face-to-face, by telephone or even online?

Consider internal milestones such as meetings and decision-making deadlines.

Timescale could include:

- Timescale for the procurement process, the start of the research and when you want the findings

- Whether you want to receive top-line findings in advance of the main findings

- Leaving time to receive a draft set of findings for you to review before receiving the final deliverables.

Do you have a specific research budget in mind, including incentives and recruitment?

Can you provide guidance on the available budget, even if it is only a ball-park figure?

Budget could include:

- An indication of available budget; stipulate whether or not this includes VAT.

- A breakdown of how recruitment and incentives.

- Payment terms (if standard)

Deliverables (what/how/when)

Do you want the findings in a written report format or as a presentation? You may want to have both or to have a meeting with us to discuss the findings.

Deliverables could include:

- Your preferred format for the findings — for example, a report in Word or a presentation in PowerPoint, hardcopy and/or electronic, etc

- Do you want the researcher to present the findings, either in-person or remotely?

- Is there anything else you expect the research team to provide?

If there are any pre-existing hunches, assumptions or hypotheses then now is a good time to share them with us. If they come out part-way through the project they may result in a re-brief and re-costing exercise, which is something to be avoided.

Materials the client will provide

Provide a detailed breakdown of the materials, assets and stimulus that the client will provide.

Examples might include:

- Visual brand identity assets

- Market reports/intelligence

- Information about competitors

- Stimulus materials

- Concepts and mockups

What does success look like?

Cast yourself into the future and imagine you are looking back at the successful project. What made it so successful, what was so good about it. Did it make you ‘famous’, if so why?

What does failure look like?

What are the failure factors of this project and what would team it unsuccessful? Another way to think about this would be to ask the question ‘Why might this project fail?’

Client contacts and roles

Who are the immediate client team responsible for running this project, including day-to-day contact details and email addresses. It’s also a good idea to address what time/input the client has to invest in the project as you may find they don’t want to be involved in the way you hope.

There you have it. There are of course more things to consider and more detail to add pending the size/scale/risk of the project, but hopefully, this will get you started. There are many mistakes you can make in executing qualitative research, this is just one. Here are a few others to be mindful of when it comes to online qualitative research and research communities.

If you need a briefing template you can download one of the ones we use here . Hope it helps!

If you have any questions, or have a brief you’d like help with…

Feel free to contact us .

Written by Further

Text to speech

- Defining Research Objectives: How To Write Them

Almost all industries use research for growth and development. Research objectives are how researchers ensure that their study has direction and makes a significant contribution to growing an industry or niche.

Research objectives provide a clear and concise statement of what the researcher wants to find out. As a researcher, you need to clearly outline and define research objectives to guide the research process and ensure that the study is relevant and generates the impact you want.

In this article, we will explore research objectives and how to leverage them to achieve successful research studies.

What Are Research Objectives?

Research objectives are what you want to achieve through your research study. They guide your research process and help you focus on the most important aspects of your topic.

You can also define the scope of your study and set realistic and attainable study goals with research objectives. For example, with clear research objectives, your study focuses on the specific goals you want to achieve and prevents you from spending time and resources collecting unnecessary data.

However, sticking to research objectives isn’t always easy, especially in broad or unconventional research. This is why most researchers follow the SMART criteria when defining their research objectives.

Understanding SMART Criteria in Research

Think of research objectives as a roadmap to achieving your research goals, with the SMART criteria as your navigator on the map.

SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. These criteria help you ensure that your research objectives are clear, specific, realistic, meaningful, and time-bound.

Here’s a breakdown of the SMART Criteria:

Specific : Your research objectives should be clear: what do you want to achieve, why do you want to achieve it, and how do you plan to achieve it? Avoid vague or broad statements that don’t provide enough direction for your research.

Measurable : Your research objectives should have metrics that help you track your progress and measure your results. Also, ensure the metrics are measurable with data to verify them.

Achievable : Your research objectives should be within your research scope, timeframe, and budget. Also, set goals that are challenging but not impossible.

Relevant: Your research objectives should be in line with the goal and significance of your study. Also, ensure that the objectives address a specific issue or knowledge gap that is interesting and relevant to your industry or niche.

Time-bound : Your research objectives should have a specific deadline or timeframe for completion. This will help you carefully set a schedule for your research activities and milestones and monitor your study progress.

Characteristics of Effective Research Objectives

Clarity : Your objectives should be clear and unambiguous so that anyone who reads them can understand what you intend to do. Avoid vague or general terms that could be taken out of context.

Specificity : Your objectives should be specific and address the research questions that you have formulated. Do not use broad or narrow objectives as they may restrict your field of research or make your research irrelevant.

Measurability : Define your metrics with indicators or metrics that help you determine if you’ve accomplished your goals or not. This will ensure you are tracking the research progress and making interventions when needed.

Also, do use objectives that are subjective or based on personal opinions, as they may be difficult to accurately verify and measure.

Achievability : Your objectives should be realistic and attainable, given the resources and time available for your research project. You should set objectives that match your skills and capabilities, they can be difficult but not so hard that they are realistically unachievable.

For example, setting very difficult make you lose confidence, and abandon your research. Also, setting very simple objectives could demotivate you and prevent you from closing the knowledge gap or making significant contributions to your field with your research.

Relevance : Your objectives should be relevant to your research topic and contribute to the existing knowledge in your field. Avoid objectives that are unrelated or insignificant, as they may waste your time or resources.

Time-bound : Your objectives should be time-bound and specify when you will complete them. Have a realistic and flexible timeframe for achieving your objectives, and track your progress with it.

Steps to Writing Research Objectives

Identify the research questions.

The first step in writing effective research objectives is to identify the research questions that you are trying to answer. Research questions help you narrow down your topic and identify the gaps or problems that you want to address with your research.

For example, if you are interested in the impact of technology on children’s development, your research questions could be:

- What is the relationship between technology use and academic performance among children?

- Are children who use technology more likely to do better in school than those who do not?

- What is the social and psychological impact of technology use on children?

Brainstorm Objectives

Once you have your research questions, you can brainstorm possible objectives that relate to them. Objectives are more specific than research questions, and they tell you what you want to achieve or learn in your research.

You can use verbs such as analyze, compare, evaluate, explore, investigate, etc. to express your objectives. Also, try to generate as many objectives as possible, without worrying about their quality or feasibility at this stage.

Prioritize Objectives

Once you’ve brainstormed your objectives, you’ll need to prioritize them based on their relevance and feasibility. Relevance is how relevant the objective is to your research topic and how well it fits into your overall research objective.

Feasibility is how realistic and feasible the objective is compared to the time, money, and expertise you have. You can create a matrix or ranking system to organize your objectives and pick the ones that matter the most.

Refine Objectives

The next step is to refine and revise your objectives to ensure clarity and specificity. Start by ensuring that your objectives are consistent and coherent with each other and with your research questions.

Make Objectives SMART

A useful way to refine your objectives is to make them SMART, which stands for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

- Specific : Objectives should clearly state what you hope to achieve.

- Measurable : They should be able to be quantified or evaluated.

- Achievable : realistic and within the scope of the research study.

- Relevant : They should be directly related to the research questions.

- Time-bound : specific timeframe for research completion.

Review and Finalize Objectives

The final step is to review your objectives for coherence and alignment with your research questions and aim. Ensure your objectives are logically connected and consistent with each other and with the purpose of your study.

You also need to check that your objectives are not too broad or too narrow, too easy or too hard, too many or too few. You can use a checklist or a rubric to evaluate your objectives and make modifications.

Examples of Well-Written Research Objectives

Example 1- Psychology

Research question: What are the effects of social media use on teenagers’ mental health?

Objective : To determine the relationship between the amount of time teenagers in the US spend on social media and their levels of anxiety and depression before and after using social media.

What Makes the Research Objective SMART?

The research objective is specific because it clearly states what the researcher hopes to achieve. It is measurable because it can be quantified by measuring the levels of anxiety and depression in teenagers.

Also, the objective is achievable because the researcher can collect enough data to answer the research question. It is relevant because it is directly related to the research question. It is time-bound because it has a specific deadline for completion.

Example 2- Marketing

Research question : How can a company increase its brand awareness by 10%?

Objective : To develop a marketing strategy that will increase the company’s sales by 10% within the next quarter.

How Is this Research Objective SMART?

The research states what the researcher hopes to achieve ( Specific ). You can also measure the company’s reach before and after the marketing plan is implemented ( Measurable ).

The research objective is also achievable because you can develop a marketing plan that will increase awareness by 10% within the timeframe. The objective is directly related to the research question ( Relevant ). It is also time-bound because it has a specific deadline for completion.

Research objectives are a well-designed roadmap to completing and achieving your overall research goal.

However, research goals are only effective if they are well-defined and backed up with the best practices such as the SMART criteria. Properly defining research objectives will help you plan and conduct your research project effectively and efficiently.