Brought to you by:

The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster: Causes, Consequences, and Implications

By: Jochen Reb, Yoshisuke Iinuma, Havovi Joshi

This case study discusses the causes, consequences and implications of the nuclear disaster at Tokyo Electric Power Company's (TEPCO's) Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant that was triggered by a…

- Length: 11 page(s)

- Publication Date: Oct 25, 2012

- Discipline: General Management

- Product #: SMU103-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

This case study discusses the causes, consequences and implications of the nuclear disaster at Tokyo Electric Power Company's (TEPCO's) Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant that was triggered by a massive 9.0 magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunami waves on March 11, 2011. There are two essential questions: First, "How could it have come so far?" Japan is rightfully considered a technologically advanced nation and is known for its diligence and high-quality products. While the combined earthquake/tsunami triggered the catastrophe, there are a number of deeper underlying causes that are described in the first section of the case. Second, "What next?" While the plant technically achieved cold shutdown with all damaged reactors reaching temperatures below 100°C, this did not mean that the Fukushima disaster was over. Instead, numerous consequences and implications extend into the future.

Learning Objectives

Students will become more aware of the psychological, interpersonal, organisational, and institutional contributors to crises. They will learn to recognise the development, characteristics, and negative consequences of groupthink; and understand the crucial role of communications during crisis management. Students will also discuss broader implications such as the future of nuclear energy and the responsibility of organisations in catastrophes.

Oct 25, 2012

Discipline:

General Management

Geographies:

Industries:

Energy and natural resources sector

Singapore Management University

SMU103-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Javascript Required!

Javascript is required for this site.

Fukushima Daiichi Accident

(Updated August 2023)

- Following a major earthquake, a 15-metre tsunami disabled the power supply and cooling of three Fukushima Daiichi reactors, causing a nuclear accident beginning on 11 March 2011. All three cores largely melted in the first three days.

- The accident was rated level 7 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, due to high radioactive releases over days 4 to 6, eventually a total of some 940 PBq (I-131 eq).

- All four Fukushima Daiichi reactors were written off due to damage in the accident – 2719 MWe net.

- After two weeks, the three reactors (units 1-3) were stable with water addition and by July they were being cooled with recycled water from the new treatment plant. Official 'cold shutdown condition' was announced in mid-December.

- Apart from cooling, the basic ongoing task was to prevent release of radioactive materials, particularly in contaminated water leaked from the three units. This task became newsworthy in August 2013.

- There have been no deaths or cases of radiation sickness from the nuclear accident, but over 100,000 people were evacuated from their homes as a preventative measure. Government nervousness has delayed the return of many.

- Official figures show that there have been 2313 disaster-related deaths among evacuees from Fukushima prefecture. Disaster-related deaths are in addition to the about 19,500 that were killed by the earthquake or tsunami.

The Great East Japan Earthquake of magnitude 9.0 at 2.46 pm on Friday 11 March 2011 did considerable damage in the region, and the large tsunami it created caused very much more. The earthquake was centred 130 km offshore the city of Sendai in Miyagi prefecture on the eastern coast of Honshu Island (the main part of Japan), and was a rare and complex double quake giving a severe duration of about 3 minutes. An area of the seafloor extending 650 km north-south moved typically 10-20 metres horizontally. Japan moved a few metres east and the local coastline subsided half a metre. The tsunami inundated about 560 km 2 and resulted in a human death toll of about 19,500 and much damage to coastal ports and towns, with over a million buildings destroyed or partly collapsed.

Eleven reactors at four nuclear power plants in the region were operating at the time and all shut down automatically when the earthquake hit. Subsequent inspection showed no significant damage to any from the earthquake. The operating units which shut down were Tokyo Electric Power Company's (Tepco's) Fukushima Daiichi 1, 2, 3, and Fukushima Daini 1, 2, 3, 4, Tohoku's Onagawa 1, 2, 3, and Japco's Tokai, total 9377 MWe net. Fukushima Daiichi units 4, 5&6 were not operating at the time, but were affected. The main problem initially centred on Fukushima Daiichi 1-3. Unit 4 became a problem on day five.

The reactors proved robust seismically, but vulnerable to the tsunami. Power, from grid or backup generators, was available to run the residual heat removal (RHR) system cooling pumps at eight of the eleven units, and despite some problems they achieved 'cold shutdown' within about four days. The other three, at Fukushima Daiichi, lost power at 3.42 pm, almost an hour after the earthquake, when the entire site was flooded by the 15-metre tsunami. This disabled 12 of 13 backup generators onsite and also the heat exchangers for dumping reactor waste heat and decay heat to the sea. The three units lost the ability to maintain proper reactor cooling and water circulation functions. Electrical switchgear was also disabled. Thereafter, many weeks of focused work centred on restoring heat removal from the reactors and coping with overheated spent fuel ponds. This was undertaken by hundreds of Tepco employees as well as some contractors, supported by firefighting and military personnel. Some of the Tepco staff had lost homes, and even families, in the tsunami, and were initially living in temporary accommodation under great difficulty and privation, with some personal risk. A hardened onsite emergency response centre was unable to be used in grappling with the situation, due to radioactive contamination.

Three Tepco employees at the Daiichi and Daini plants were killed directly by the earthquake and tsunami, but there have been no fatalities from the nuclear accident.

Among hundreds of aftershocks, an earthquake with magnitude 7.1, closer to Fukushima than the 11 March one, was experienced on 7 April, but without further damage to the plant. On 11 April a magnitude 7.1 earthquake and on 12 April a magnitude 6.3 earthquake, both with the epicentre at Fukushima-Hamadori, caused no further problems.

The two Fukushima plants and their siting

The Daiichi (first) and Daini (second) Fukushima plants are sited about 11 km apart on the coast, Daini to the south.

The recorded seismic data for both plants – some 180 km from the epicentre – shows that 550 Gal (0.56 g) was the maximum ground acceleration for Daiichi, and 254 Gal was maximum for Daini. Daiichi units 2, 3 and 5 exceeded their maximum response acceleration design basis in an east-west direction by about 20%. The recording was over 130-150 seconds. (All nuclear plants in Japan are built on rock – ground acceleration was around 2000 Gal a few kilometres north, on sediments).

The original design basis tsunami height was 3.1 m for Daiichi based on assessment of the 1960 Chile tsunami and so the plant had been built about 10 metres above sea level with the seawater pumps 4 m above sea level. The Daini plant was built 13 metres above sea level. In 2002 the design basis was revised to 5.7 metres above, and the seawater pumps were sealed. In the event, tsunami heights coming ashore were about 15 metres, and the Daiichi turbine halls were under some 5 metres of seawater until levels subsided. Daini was less affected. The maximum amplitude of this tsunami was 23 metres at point of origin, about 180 km from Fukushima.

In the last century there have been eight tsunamis in the region with maximum amplitudes at origin above 10 metres (some much more), these having arisen from earthquakes of magnitude 7.7 to 8.4, on average one every 12 years. Those in 1983 and in 1993 were the most recent affecting Japan, with maximum heights at origin of 14.5 metres and 31 metres respectively, both induced by magnitude 7.7 earthquakes. The June 1896 earthquake of estimated magnitude 8.3 produced a tsunami with run-up height of 38 metres in Tohoku region, killing more than 27,000 people.

The tsunami countermeasures taken when Fukushima Daiichi was designed and sited in the 1960s were considered acceptable in relation to the scientific knowledge then, with low recorded run-up heights for that particular coastline. But some 18 years before the 2011 disaster, new scientific knowledge had emerged about the likelihood of a large earthquake and resulting major tsunami of some 15.7 metres at the Daiichi site. However, this had not yet led to any major action by either the plant operator, Tepco, or government regulators, notably the Nuclear & Industrial Safety Agency (NISA). Discussion was ongoing, but action minimal. The tsunami countermeasures could also have been reviewed in accordance with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) guidelines which required taking into account high tsunami levels, but NISA continued to allow the Fukushima plant to operate without sufficient countermeasures such as moving the backup generators up the hill, sealing the lower part of the buildings, and having some back-up for seawater pumps, despite clear warnings.

A report from the Japanese government's Earthquake Research Committee on earthquakes and tsunamis off the Pacific coastline of northeastern Japan in February 2011 was due for release in April, and might finally have brought about changes. The document includes analysis of a magnitude 8.3 earthquake that is known to have struck the region more than 1140 years ago, triggering enormous tsunamis that flooded vast areas of Miyagi and Fukushima prefectures. The report concludes that the region should be alerted of the risk of a similar disaster striking again. The 11 March earthquake measured magnitude 9.0 and involved substantial shifting of multiple sections of seabed over a source area of 200 x 400 km. Tsunami waves devastated wide areas of Miyagi, Iwate and Fukushima prefectures.

(See also background on Earthquakes and Seismic Protection for Nuclear Power Plants in Japan )

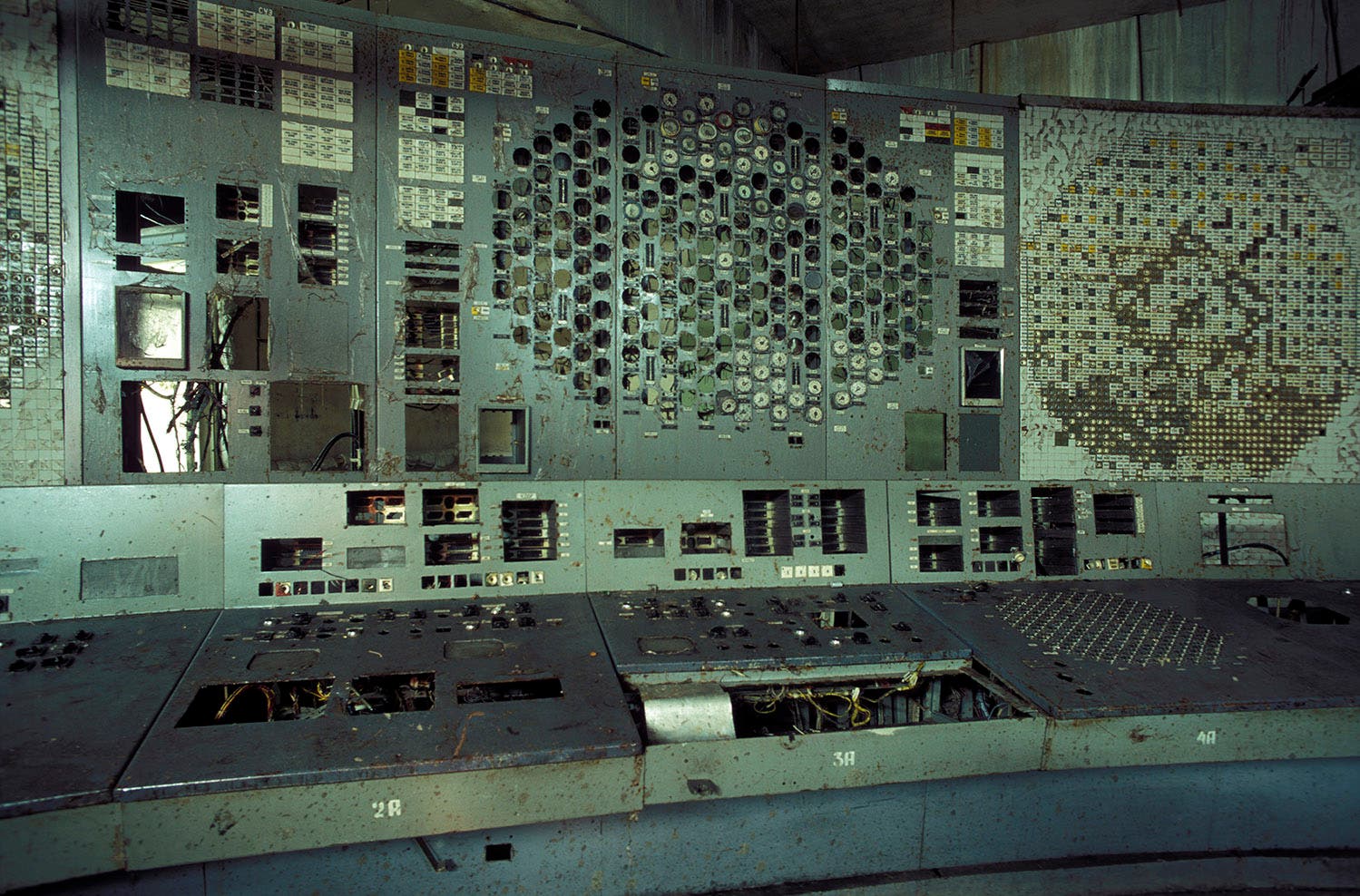

Events at Fukushima Daiichi 1-3 & 4

It appears that no serious damage was done to the reactors by the earthquake, and the operating units 1-3 were automatically shut down in response to it, as designed. At the same time all six external power supply sources were lost due to earthquake damage, so the emergency diesel generators located in the basements of the turbine buildings started up. Initially cooling would have been maintained through the main steam circuit bypassing the turbine and going through the condensers.

Then 41 minutes later, at 3:42 pm, the first tsunami wave hit, followed by a second 8 minutes later. These submerged and damaged the seawater pumps for both the main condenser circuits and the auxiliary cooling circuits, notably the residual heat removal (RHR) cooling system. They also drowned the diesel generators and inundated the electrical switchgear and batteries, all located in the basements of the turbine buildings (the one surviving air-cooled generator was serving units 5&6). So there was a station blackout, and the reactors were isolated from their ultimate heat sink. The tsunamis also damaged and obstructed roads, making outside access difficult.

All this put reactors 1-3 in a dire situation and led the authorities to order, and subsequently extend, an evacuation while engineers worked to restore power and cooling. The 125-volt DC back-up batteries for units 1&2 were flooded and failed, leaving them without instrumentation, control or lighting. Unit 3 had battery power for about 30 hours.

At 7:03 pm Friday 11 March a nuclear emergency was declared, and at 8:50pm the Fukushima prefecture issued an evacuation order for people within 2 km of the plant. At 9:23 pm the prime minister extended this to 3 km, and at 5:44 am on 12 March he extended it to 10 km. He visited the plant soon after. Later on Saturday 12 March he extended the evacuation zone to 20 km.

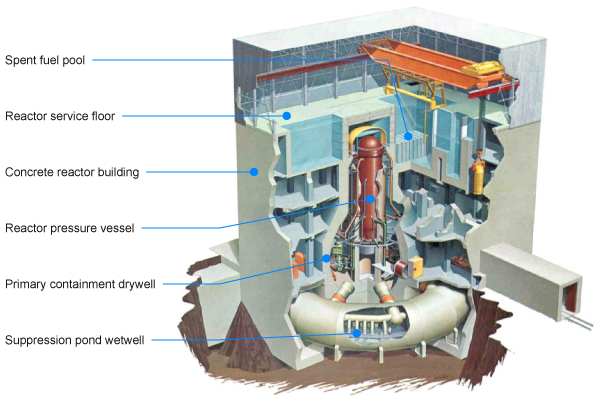

Inside the Fukushima Daiichi reactors

The Fukushima Daiichi reactors were GE boiling water reactors (BWRs) of an early (1960s) design supplied by GE, Toshiba and Hitachi, with what is known as a Mark I containment. Reactors 1-3 came into commercial operation 1971-75. Reactor capacity was 460 MWe for unit 1, 784 MWe for units 2-5, and 1100 MWe for unit 6.

When the power failed at 3:42 pm, about one hour after shutdown of the fission reactions, the reactor cores would still have been producing about 1.5% of their nominal thermal power, from fission product decay – about 22 MW in unit 1 and 33 MW in units 2&3. Without heat removal by circulation to an outside heat exchanger, this produced a lot of steam in the reactor pressure vessels (RPVs) housing the cores, and this was released into the dry primary containment (PCV) through safety valves. Later this was accompanied by hydrogen, produced by the interaction of the fuel's very hot zirconium cladding with steam after the water level dropped.

As pressure started to rise here, the steam was directed into the suppression chamber/wetwell under the reactor, within the containment, but the internal temperature and pressure nevertheless rose quite rapidly. Water injection commenced, using the various systems provide for this and finally the emergency core cooling system (ECCS). These systems progressively failed over three days, so from early Saturday water injection to the RPV was with fire pumps, but this required the internal pressures to be relieved initially by venting into the suppression chamber/wetwell. Seawater injection into unit 1 began at 7:00 pm on Saturday 12, into unit 3 on Sunday 13 and unit 2 on Monday 14. Tepco management ignored an instruction from the prime minister to cease the seawater injection into unit 1, and this instruction was withdrawn shortly afterwards.

Inside unit 1 , it is understood that the water level dropped to the top of the fuel about three hours after the scram (about 6:00 pm) and the bottom of the fuel 1.5 hours later (7:30 pm). The temperature of the exposed fuel rose to some 2800°C so that the central part started to melt after a few hours and by 16 hours after the scram (7:00 am Saturday) most of it had fallen into the water at the bottom of the RPV. After that, RPV temperatures decreased steadily.

As pressure rose, attempts were made to vent the containment, and when external power and compressed air sources were harnessed this was successful, by about 2:30 pm Saturday, though some manual venting was apparently achieved at about 10:17 am. The venting was designed to be through an external stack, but in the absence of power much of it apparently backflowed to the service floor at the top of the reactor building, representing a serious failure of this system (though another possibility is leakage from the drywell). The vented steam, noble gases and aerosols were accompanied by hydrogen. At 3:36 pm on Saturday 12, there was a hydrogen explosion on the service floor of the building above unit 1 reactor containment, blowing off the roof and cladding on the top part of the building, after the hydrogen mixed with air and ignited. (Oxidation of the zirconium cladding at high temperatures in the presence of steam produces hydrogen exothermically, with this exacerbating the fuel decay heat problem.)

In unit 1 most of the core – as corium, composed of melted fuel and control rods – was assumed to be in the bottom of the RPV, but later it appeared that it had mostly gone through the bottom of the RPV and eroded about 65 cm into the drywell concrete below (which is 2.6 m thick). This reduced the intensity of the heat and enabled the mass to solidify.

Much of the fuel in units 2&3 also apparently melted to some degree, but to a lesser extent than in unit 1, and a day or two later. In mid-May 2011 the unit 1 core would still have been producing 1.8 MW of heat, and units 2&3 about 3.0 MW each.

In mid-2013 the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) confirmed that the earthquake itself had caused no damage to unit 1.

In unit 2 , water injection using the steam-driven back-up water injection system failed on Monday 14, and it was about six hours before a fire pump started injecting seawater into the RPV. Before the fire pump could be used RPV pressure had to be relieved via the wetwell, which required power and nitrogen, hence the delay. Meanwhile the reactor water level dropped rapidly after backup cooling was lost, so that core damage started about 8 pm, and it is now understood that much of the fuel then melted and probably fell into the water at the bottom of the RPV about 100 hours after the scram. Pressure was vented on Sunday 13 and again on Tuesday 15, and meanwhile the blowout panel near the top of the building was opened to avoid a repetition of the hydrogen explosion at unit 1. Early on Tuesday 15, the pressure suppression chamber under the actual reactor seemed to rupture, possibly due to a hydrogen explosion there, and the drywell containment pressure inside dropped. However, subsequent inspection of the suppression chamber did not support the rupture interpretation. Later analysis suggested that a leak of the primary containment developed on Tuesday 15. Most of the radioactive releases from the site appeared to come from unit 2.

In unit 3 , the main backup water injection system failed at about 11:00 am on Saturday 12, and early on Sunday 13 water injection using the high pressure system failed also and water levels dropped dramatically. RPV pressure was reduced by venting steam into the wetwell, allowing injection of seawater using a fire pump from just before noon. Early on Sunday venting the suppression chamber and containment was successfully undertaken. It is now understood that core damage started about 5:30 am and much or all of the fuel melted on the morning of Sunday 13 and fell into the bottom of the RPV, with some probably going through the bottom of the reactor pressure vessel and onto the concrete below.

Early on Monday 14 PCV venting was repeated, and this evidently backflowed to the service floor of the building, so that at 11:00 am a very large hydrogen explosion here above unit 3 reactor containment blew off much of the roof and walls and demolished the top part of the building. This explosion created a lot of debris, and some of that on the ground near unit 3 was very radioactive.

In defuelled unit 4 , at about 6:00 am on Tuesday 15 March, there was an explosion which destroyed the top of the building and damaged unit 3's superstructure further. This was apparently from hydrogen arising in unit 3 and reaching unit 4 by backflow in shared ducts when vented from unit 3.

Units 1-3: Water had been injected into each of the three reactor units more or less continuously, and in the absence of normal heat removal via external heat exchanger this water was boiling off for some months. In the government report to the IAEA in June it was estimated that to the end of May about 40% of the injected water boiled off, and 60% leaked out the bottom. In June 2011 this was adding to the contaminated water onsite by about 500 m 3 per day. In January 2013 4.5 to 5.5 m 3 /h was being added to each RPV via core spray and feedwater systems, hence 370 m 3 per day, and temperatures at the bottom of RPVs were 19 °C in unit 1 and 32 °C in units 2&3, at little above atmospheric pressure.

There was a peak of radioactive release on Tuesday 15, apparently mostly from unit 2, but the precise source remains uncertain. Due to volatile and easily-airborne fission products being carried with the hydrogen and steam, the venting and hydrogen explosions discharged a lot of radioactive material into the atmosphere, notably iodine and caesium. NISA said in June that it estimated that 800-1000 kg of hydrogen had been produced in each of the units.

Nitrogen was being injected into the PCVs of all three reactors to remove concerns about further hydrogen explosions, and in December this was started also for the pressure vessels. Gas control systems which extract and clean the gas from the PCV to avoid leakage of caesium were commissioned for all three units.

Throughout 2011 injection into the RPVs of water circulated through the new water treatment plant achieved relatively effective cooling, and temperatures at the bottom of the RPVs were stable in the range 60-76 °C at the end of October, and 27-54 °C in mid-January 2012. RPV pressures ranged from atmospheric to slightly above (102-109 kPa) in January, due to water and nitrogen injection. However, since they were leaking, the normal definition of 'cold shutdown' did not apply, and Tepco waited to bring radioactive releases under control before declaring 'cold shutdown condition' in mid-December, with NISA's approval. This, with the prime minister's announcement of it, formally brought to a close the 'accident' phase of events.

The AC electricity supply from external source was connected to all units by 22 March. Power was restored to instrumentation in all units except unit 3 by 25 March. However, radiation levels inside the plant were so high that normal access was impossible until June.

Event sequence following earthquake (timing from it: 14:46, 11 March)

* according to 2012 MAAP (Modular Accident Analysis Program) analysis

By March 2016 total decay heat in units 1-3 had dropped to 1 MW for all three, about 1% of the original level, meaning that cooling water injection – then 100 m 3 /d – could be interrupted for up to two days.

Results of muon measurements in unit 2 in 2016 indicate that most of the fuel debris in unit 2 is in the bottom of the reactor vessel.

Tepco has written off the four reactors damaged by the accident, and is decommissioning them.

Summary : Major fuel melting occurred early on in all three units, though the fuel remained essentially contained except for some volatile fission products vented early on, or released from unit 2 in mid-March, and some soluble ones which were leaking with the water, especially from unit 2, where the containment is evidently breached. Cooling is provided from external sources, using treated recycled water, with a stable heat removal path from the actual reactors to external heat sinks. Access has been gained to all three reactor buildings, but dose rates remain high inside. Tepco declared 'cold shutdown condition' in mid-December 2011 when radioactive releases had reduced to minimal levels.

(See also background on nuclear reactors at Fukushima Daiichi .)

Fuel ponds: developing problems

Used fuel needs to be cooled and shielded. This is initially by water, in ponds. After about three years underwater, used fuel can be transferred to dry storage, with air ventilation simply by convection. Used fuel generates heat, so the water in ponds is circulated by electric pumps through external heat exchangers, so that the heat is dumped and a low temperature maintained. There are fuel ponds near the top of all six reactor buildings at the Daiichi plant, adjacent to the top of each reactor so that the fuel can be unloaded underwater when the top is off the reactor pressure vessel and it is flooded. The ponds hold some fresh fuel and some used fuel, the latter pending its transfer to the onsite central used/spent fuel storage. (There is some dry storage onsite to extend the plant's capacity.)

At the time of the accident, in addition to a large number of used fuel assemblies, unit 4's pond also held a full core load of 548 fuel assemblies while the reactor was undergoing maintenance, these having been removed at the end of November, and were to be replaced in the core.

A separate set of problems arose as the fuel ponds, holding fresh and used fuel in the upper part of the reactor structures, were found to be depleted in water. The primary cause of the low water levels was loss of cooling circulation to external heat exchangers, leading to elevated temperatures and probably boiling, especially in the heavily-loaded unit 4 fuel pond. Here the fuel would have been uncovered in about 7 days due to water boiling off. However, the fact that unit 4 was unloaded meant that there was a large inventory of water at the top of the structure, and enough of this replenished the fuel pond to prevent the fuel becoming uncovered – the minimum level reached was about 1.2 m above the fuel on about 22 April.

After the hydrogen explosion in unit 4 early on Tuesday 15 March, Tepco was told to implement injection of water to unit 4 pond which had a particularly high heat load (3 MW) from 1331 used fuel assemblies in it, so it was the main focus of concern. It needed the addition of about 100 m 3 /day to replenish it after circulation ceased.

From Tuesday 15 March attention was given to replenishing the water in the ponds of units 1, 2&3 as well. Initially this was attempted with fire pumps but from 22 March a concrete pump with 58-metre boom enabled more precise targeting of water through the damaged walls of the service floors. There was some use of built-in plumbing for unit 2. Analysis of radionuclides in water from the used fuel ponds suggested that some of the fuel assemblies might have been damaged, but the majority were intact.

There was concern about the structural strength of unit 4 building, so support for the pond was reinforced by the end of July.

New cooling circuits with heat exchangers adjacent to the reactor buildings for all four ponds were commissioned after a few months, and each reduced the pool temperature from 70 °C to normal in a few days. Each has a primary circuit within the reactor and waste treatment buildings and a secondary circuit dumping heat through a small dry cooling tower outside the building.

The next task was to remove the salt from those ponds which had seawater added, to reduce the potential for corrosion.

In July 2012 two of the 204 fresh fuel assemblies were removed from the unit 4 pool and transferred to the central spent fuel pool for detailed inspection to check damage, particularly corrosion. They were found to have no deformation or corrosion. Unloading the 1331 spent fuel assemblies in pond 4 and transferring them to the central spent fuel pool commenced in mid-November 2013 and was completed 13 months later. These comprised 783 spent fuel plus the full fuel load of 548.

The next focus of attention was the unit 3 pool. In 2015 the damaged fuel handling equipment and other wreckage was removed from the destroyed upper level of the reactor building. Toshiba built a 74-tonne fuel handling machine for transferring the 566 fuel assemblies into casks and to remove debris in the pool, and a crane for lifting the fuel transfer casks. Installation of a cover over the fuel handling machine was completed in February 2018. Removal and transferral of the fuel to the central spent fuel pool began in mid-April 2019 and was completed at the end of February 2021.

The onsite central spent fuel pool in 2011 held about 60% of the Daiichi used fuel, and is immediately west (inland) of unit 4. It lost circulation with the power outage, and temperature increased to 73 °C by the time mains power and cooling were restored after two weeks. In late 2013 this pond, with capacity for 6840*, held 6375 fuel assemblies, the same as at the time of the accident. In June 2018, Tepco announced it would transfer some of the fuel assemblies stored in the central spent fuel pool to an onsite temporary dry storage facility to clear sufficient space for the fuel assemblies from unit 3's pool. The dry storage facility has a capacity of at least 2930 assemblies in 65 casks – each dry cask holds 50 fuel assemblies. Eventually these will be shipped to JNFL’s Rokkasho reprocessing plant or to Recyclable Fuel Storage Company’s Mutsu facility.

* effectively 6750, due to one rack of 90 having some damaged fuel.

Summary: The spent fuel storage pools survived the earthquake, tsunami and hydrogen explosions without significant damage to the fuel, significant radiological release, or threat to public safety. The new cooling circuits with external heat exchangers for the four ponds are working well and temperatures are normal. Analysis of water has confirmed that most fuel rods are intact. All fuel assemblies have been removed from the unit 3&4 pools.

(See also background on Fukushima Fuel Ponds and Decommissioning section below.)

Radioactive releases to air

Regarding releases to air and also water leakage from Fukushima Daiichi, the main radionuclide from among the many kinds of fission products in the fuel was volatile iodine-131, which has a half-life of 8 days. The other main radionuclide is caesium-137, which has a 30-year half-life, is easily carried in a plume, and when it lands it may contaminate land for some time. It is a strong gamma-emitter in its decay. Cs-134 is also produced and dispersed; it has a two-year half-life. Caesium is soluble and can be taken into the body, but does not concentrate in any particular organs, and has a biological half-life of about 70 days. In assessing the significance of atmospheric releases, the Cs-137 figure is multiplied by 40 and added to the I-131 number to give an 'iodine-131 equivalent' figure.

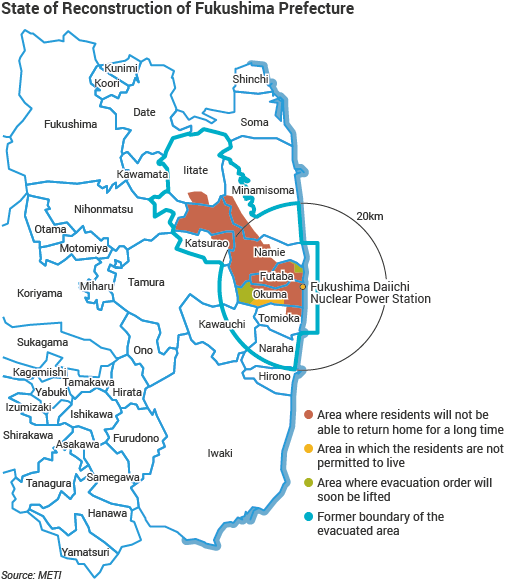

As cooling failed on the first day, evacuations were progressively ordered, due to uncertainty about what was happening inside the reactors and the possible effects. By the evening of Saturday 12 March the evacuation zone had been extended to 20 km from the plant. From 20 to 30 km from the plant, the criterion of 20 mSv/yr dose rate was applied to determine evacuation, and is now the criterion for return being allowed. 20 mSv/yr was also the general limit set for children's dose rate related to outdoor activities, but there were calls to reduce this. In areas with 20-50 mSv/yr from April 2012 residency is restricted, with remediation action taken. See later section on Public health and return of evacuees .

A significant problem in tracking radioactive release was that 23 out of the 24 radiation monitoring stations on the plant site were disabled by the tsunami.

There is some uncertainty about the amount and exact sources of radioactive releases to air (see also background on Radiation Exposure ).

Japan’s regulator, the Nuclear & Industrial Safety Agency (NISA), estimated in June 2011 that 770 PBq (iodine-131 equivalent) of radioactivity had been released, but the Nuclear Safety Commission (NSC, a policy body) in August lowered this estimate to 570 PBq . The 770 PBq figure is about 15% of the Chernobyl release of 5200 PBq iodine-131 equivalent. Most of the release was by the end of March 2011.

Tepco sprayed a dust-suppressing polymer resin around the plant to ensure that fallout from mid-March was not mobilized by wind or rain. In addition it removed a lot of rubble with remote control front-end loaders, and this further reduced ambient radiation levels, halving them near unit 1. The highest radiation levels onsite came from debris left on the ground after the explosions at units 3&4.

Reactor covers

In mid-May 2011 work started towards constructing a cover over unit 1 to reduce airborne radioactive releases from the site, to keep out the rain, and to enable measurement of radioactive releases within the structure through its ventilation system. The frame was assembled over the reactor, enclosing an area 42 x 47 m, and 54 m high. The sections of the steel frame fitted together remotely without the use of screws and bolts. All the wall panels had a flameproof coating, and the structure had a filtered ventilation system capable of handling 40,000 cubic metres of air per hour through six lines, including two backup lines. The cover structure was fitted with internal monitoring cameras, radiation and hydrogen detectors, thermometers and a pipe for water injection. The cover was completed with ventilation systems working by the end of October 2011. It was expected to be needed for two years. In May 2013 Tepco announced its more permanent replacement, to be built over four years. It started demolishing the 2011 cover in 2014 and finished in 2016. In December 2019 it decided to install the replacement cover before removing debris from the top floor of the building. A crane and other equipment for fuel removal will be installed under the cover, similar to that over unit 4.

More substantial covers were designed to fit around units 3&4 reactor buildings after the top floors were cleared up in 2012.

A cantilevered structure was built over unit 4 from April 2012 to July 2013 to enable recovery of the contents of the spent fuel pond. This is a 69 x 31 m cover (53 m high) and it was fully equipped by the end of 2013 to enable unloading of used fuel from the storage pond into casks, each holding 22 fuel assemblies, and removal of the casks. This operation was accomplished under water, using the new fuel handling machine (replacing the one destroyed by the hydrogen explosion) so that the used fuel could be transferred to the central storage onsite. Transfer was completed in December 2014. A video of the process is available on Tepco's website.

A different design of cover was built over unit 3, and foundation work began in 2012. Large rubble removal took place from 2013 to 2015, including the damaged fuel handling machine. An arched cover was prefabricated, 57 m long and 19 m wide, and supported by the turbine building on one side and the ground on the other. A crane removed the 566 fuel assemblies from the pool and some remaining rubble. Spent fuel removal from unit 3 pool began in April 2019 and was completed in February 2021. Spent fuel removal from units 1&2 pools was scheduled in 2018, but is now scheduled to begin in 2023.

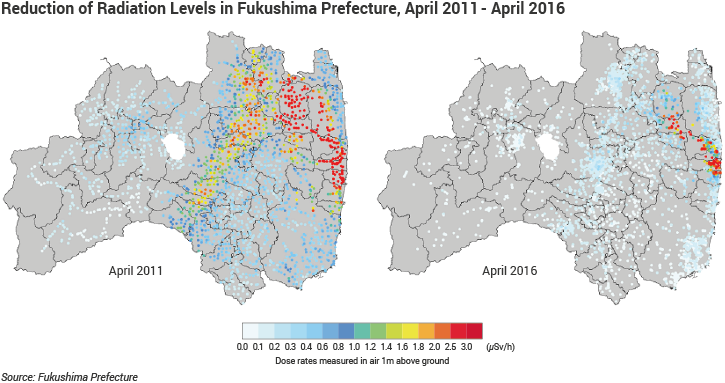

Maps from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Tehcnology (MEXT) aerial surveys carried out approximately one year apart show the reduction in contamination from late 2011 to late 2012. Areas with colour changes in 2012 showed approximately half the contamination as surveyed in 2011, the difference coming from decay of caesium-134 (two-year half-life) and natural processes like wind and rain. In blue areas, ambient radiation is very similar to global background levels at <0.5 microsieverts per hour, which is equal to <4.4 mSv/yr.

Tests on radioactivity in rice have been made and caesium was found in a few of them. The highest levels were about one-quarter of the allowable limit of 500 Bq/kg, so shipments to market are permitted.

Summary : Major releases of radionuclides, including long-lived caesium, occurred to air, mainly in mid-March. The population within a 20km radius had been evacuated three days earlier. Considerable work was done to reduce the amount of radioactive debris onsite and to stabilize dust. The main source of radioactive releases was the apparent hydrogen explosion in the suppression chamber of unit 2 on 15 March. A cover building for unit 1 reactor was built and the unit is now being dismantled, a more substantial one for unit 4 was built to enable fuel removal during 2014. Radioactive releases in mid-August 2011 had reduced to 5 GBq/hr, and dose rate from these at the plant boundary was 1.7 mSv/yr, less than natural background.

Sequence of evacuation orders based on the report by The National Diet of Japan Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission : 11 March 14:46 JST The earthquake occurred. 15:42 TEPCO made the first emergency report to the government. 19:03 The government announced nuclear emergency. 20:50 The Fukushima Prefecture Office ordered 2km radius evacuation. 21:23 The government ordered 3km evacuation and to keep staying inside buildings in the area of 3-10km radius. 12 March 05:44 The government ordered 10km radius evacuation. 18:25 The government ordered 20km evacuation. 15 March 11:01 The government ordered to keep staying inside buildings in the area of 20-30km from the plant. 25 March The government requested voluntary evacuation in the area of 20-30km. 21 April The government set the 20km radius no-go area.

Radiation exposure on the plant site

By the end of 2011, Tepco had checked the radiation exposure of 19,594 people who had worked on the site since 11 March. For many of these both external dose and internal doses (measured with whole-body counters) were considered. It reported that 167 workers had received doses over 100 mSv. Of these 135 had received 100 to 150 mSv, twenty-three 150-200 mSv, three more 200-250 mSv, and six had received over 250 mSv (309 to 678 mSv) apparently due to inhaling iodine-131 fumes early on. The latter included the units 3&4 control room operators in the first two days who had not been wearing breathing apparatus. There were up to 200 workers onsite each day. Recovery workers wear personal monitors, with breathing apparatus and protective clothing which protect against alpha and beta radiation. The level of 250 mSv was the allowable maximum short-term dose for Fukushima Daiichi accident clean-up workers through to December 2011, 500 mSv is the international allowable short-term dose "for emergency workers taking life-saving actions". In January 2012 the allowable maximum reverted to 50 mSv/yr.

No radiation casualties (acute radiation syndrome) occurred, and few other injuries, though higher than normal doses, were being accumulated by several hundred workers onsite. High radiation levels in the three reactor buildings hindered access there.

Monitoring of seawater, soil and atmosphere is at 25 locations on the plant site, 12 locations on the boundary, and others further afield. Government and IAEA monitoring of air and seawater is ongoing. Some high but not health-threatening levels of iodine-131 were found in March, but with an eight-day half-life, most I-131 had gone by the end of April 2011.

A radiation survey map of the site made in March 2013 revealed substantial progress: the highest dose rate anywhere on the site was 0.15 mSv/h near units 3 and 4. (Soon after the accident a similar survey put the highest dose rate at 300 mSv/h near rubble lying alongside unit 3.) The majority of the power plant area was at less than 0.01 mSv/h. These reduced levels are reflected in worker doses: during January 2013, the 5702 workers at the site received an average of 0.86 mSv, with 75% of workers recorded as receiving less than 1 mSv. In total, only about 2% of workers received over 5 mSv and the highest dose in January was 12.65 mSv for one worker.

Media reports have referred to 'nuclear gypsies' – casual workers employed by subcontractors on a short-term basis, and allegedly prone to receiving higher and unsupervised radiation doses. This transient workforce has been part of the nuclear scene for at least four decades, and at Fukushima their doses are very rigorously monitored. If they reach certain levels, e.g. 30 mSv but varying according to circumstance, they are reassigned to lower-exposure areas.

Tepco figures submitted to the NRA for the period to end January 2014 showed 173 workers had received more than 100 mSv (six more than two years earlier) and 1578 had received 50 to 100 mSv. This was among a total of 32,024, 64% more than had worked there two years earlier. Since April 2013 none of the 13,154 who had worked onsite had received more than 50 mSv, and 96% of these had less than a 20 mSv dose. Early in 2014 there were about 4000 onsite each weekday.

Summary : Six workers received radiation doses apparently over the 250 mSv level set by NISA, but at levels below those which would cause radiation sickness.

Radiation exposure and fallout beyond the plant site

On 4 April 2011, radiation levels of 0.06 mSv/day were recorded in Fukushima city, 65 km northwest of the plant, about 60 times higher than normal but posing no health risk according to authorities. Monitoring beyond the 20 km evacuation radius to 13 April showed one location – around Iitate – with up to 0.266 mSv/day dose rate, but elsewhere no more than one-tenth of this. At the end of July the highest level measured within 30km radius was 0.84 mSv/day in Namie town, 24 km away. The safety limit set by the central government in mid-April for public recreation areas was 3.8 microsieverts per hour (0.09 mSv/day).

In June 2013, analysis from Japan's Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) showed that the most contaminated areas in the Fukushima evacuation zone had reduced in size by three-quarters over the previous two years. The area subject to high dose rates (over 166 mSv/yr) diminished from 27% of the 1117 km 2 zone to 6% over 15 months to March 2013, and in the ‘no residence’ portion (originally 83-166 mSv/yr) no areas remained at this level and 70% was below 33 mSv/yr. The least-contaminated area is now entirely below 33 mSv/yr.

In August 2011 The Act on Special Measures Concerning the Handling of Radioactive Pollution was enacted and it took full effect from January 2012 as the main legal instrument to deal with all remediation activities in the affected areas, as well as the management of materials removed as a result of those activities. It specified two categories of land: Special Decontamination Areas consisting of the 'restricted areas' located within a 20 km radius from the Fukushima Daiichi plant, and 'deliberate evacuation areas' where the annual cumulative dose for individuals was anticipated to exceed 20 mSv. The national government promotes decontamination in these areas. These areas are subdivided into three: dose 1-20 mSv/yr (green); dose 20-50 mSv/yr (yellow); and dose over 50 mSv/yr and over 20 mSv/yr averaged over 5 years (red). Intensive Contamination Survey Areas including the so-called Decontamination Implementation Areas, where an additional annual cumulative dose between 1 mSv and 20 mSv was estimated for individuals. Municipalities implement decontamination activities in these areas.

Following a detailed study by 80 international experts, the UN Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation's (UNSCEAR's) May 2013 Report to the General Assembly concluded: "No radiation-related deaths or acute diseases have been observed among the workers and general public exposed to radiation from the accident. The doses to the general public, both those incurred during the first year and estimated for their lifetimes, are generally low or very low. No discernible increased incidence of radiation-related health effects are expected among exposed members of the public or their descendants."

However, the report noted: "More than 160 additional workers received effective doses currently estimated to be over 100 mSv, predominantly from external exposures. Among this group, an increased risk of cancer would be expected in the future. However, any increased incidence of cancer in this group is expected to be indiscernible because of the difficulty of confirming such a small incidence against the normal statistical fluctuations in cancer incidence."

These workers are individually monitored annually for potential late radiation-related health effects. UNSCEAR’s follow-up white paper in October 2015 said that none of the new information appraised after the 2013 report “materially affected the main findings or challenged the major assumptions of the 2013 Fukushima report."

By contrast, the public was exposed to 10-50 times less radiation. Most Japanese people were exposed to additional radiation amounting to less than the typical natural background level of 2.1 mSv per year.

In 2018 UNSCEAR decided to update the 2013 report to reflect the latest findings. In March 2021, UNSCEAR published its 2020 Report , which broadly confirms the major findings and conclusions of the 2013 report. The 2020 Report states: "No adverse health effects among Fukushima residents have been documented that are directly attributable to radiation exposure from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant accident. The Committee’s revised estimates of dose are such that future radiation-associated health effects are unlikely to be discernible."

People living in Fukushima prefecture are expected to be exposed to around 10 mSv over their entire lifetimes, while for those living further away the dose would be 0.2 mSv per year. The UNSCEAR conclusion reinforces the findings of several international reports to date, including one from the World Health Organization (WHO) that considered the health risk to the most exposed people possible: a postulated girl under one year of age living in Iitate or Namie that did not evacuate and continued life as normal for four months after the accident. Such a child's theoretical risk of developing any cancer would be increased only marginally, according to the WHO's analysis.

Despite the conclusions of reports from UNSCEAR and the WHO, the Japanese government in 2018 acknowledged a connection between the death of a former plant worker and radiation exposure. The man had been diagnosed with lung cancer in February 2016.

Eleven municipalities in the former restricted zone or planned evacuation area, within 20 km of the plant or where annual cumulative radiation dose is greater than 20 mSv, are designated 'special decontamination areas', where decontamination work is being implemented by the government. A further 100 municipalities in eight prefectures, where dose rates are equivalent to over 1 mSv per year are classed as 'intensive decontamination survey areas', where decontamination is being implemented by each municipality with funding and technical support from the national government. Decontamination of all 11 special decontamination areas has been completed.

In October 2013 a 16-member IAEA mission reported on remediation and decontamination in the special decontamination areas. Its preliminary report said that decontamination efforts were commendable but driven by unrealistic targets. If annual radiation dose was below 20 mSv, such as generally in intensive decontamination survey areas, this level was “acceptable and in line with the international standards and with the recommendations from the relevant international organizations, e.g. ICRP, IAEA, UNSCEAR and WHO.” The clear implication was that people in such areas should be allowed to return home. Furthermore the government should increase efforts to communicate this to the public, and should explain that its long-term goal of achieving an additional individual dose of 1 mSv/yr is unrealistic and unnecessary in the short term. Also, there is potential to produce more food safely in contaminated areas.

Radioactivity, primarily from caesium-137, in the evacuation zone and other areas beyond it has been reported in terms of kBq/kg (compared with kBq/m 2 around Chernobyl. A total of 3000 km 2 was contaminated above 180 kBq/m 2 , compared with 29,400 km 2 from Chernobyl). However the main measure has been presumed doses in mSv/yr. The government has adopted 20 mSv/yr as its goal for the evacuation zone and more contaminated areas outside it, and supports municipal government work to reduce levels below that. The total area under consideration for attention is 13,000 km 2 . In 2016 the Ministry of Environment announced that material with less than 8 kBq/kg caesium would no longer be specified as waste, and subject to restrictions on disposal. It allowed use of contaminated soil for embankments, where the activity was less then 8 kBq/kg, and unrestricted use if less than 100 Bq/kg. Most of the stored wastes have decayed to below the 8 kBq/kg level.

Summary : There have been no harmful effects from radiation on local people, nor any doses approaching harmful levels. However, some 160,000 people were evacuated from their homes and only from 2012 were allowed limited return. As of July 2020 over 41,000 remained displaced due to government concern about radiological effects from the accident.

Public health and return of evacuees

Permanent return remains a high priority, and the evacuation zone is being decontaminated where required and possible, so that evacuees can return. There are many cases of evacuation stress including transfer trauma among evacuees, and once the situation had stabilized at the plant these outweighed the radiological hazards of returning, with 2313 deaths reported (see below ).

In December 2011 the government said that where annual radiation dose would be below 20 mSv/yr, the government would help residents return home as soon as possible and assist local municipalities with decontamination and repair of infrastructure. In areas where radiation levels are over 20 mSv/yr evacuees will be asked to continue living elsewhere for “a few years” until the government completes decontamination and recovery work. The government said it would consider purchasing land and houses from residents of these areas if the evacuees wish to sell them.

In November 2013 the NRA decided to change the way radiation exposure was estimated. Instead of airborne surveys being the basis, personal dosimeters would be used, giving very much more accurate figures, often much less than airborne estimates. The same criteria would be used, as above, with 20 mSv/yr being the threshold of concern to authorities.

In February 2014 the results of a study were published showing that 458 residents of two study areas 20 to 30 km from the plant and a third one 50 km northwest received radiation doses from the contaminated ground similar to the country’s natural background levels. Measurement was by personal dosimeters over August-September 2012.

By September 2020, 2313 disaster-related deaths among evacuees from Fukushima prefecture*, that were not due to radiation-induced damage or to the earthquake or to the tsunami, had been identified by the Japanese authorities. About 90% of deaths were for persons above 66 years of age. Of these, about 30% occurred within the first three months of the evacuations, and about 80% within two years.

* An additional 1454 disaster-related deaths have been reported among evacuees from other tsunami- and earthquake-related prefectures. Disaster-related deaths are in addition to the over 19,500 that died in the actual earthquake and tsunami.

The premature disaster-related deaths were mainly related to (i) physical and mental illness brought about by having to reside in shelters and the trauma of being forced to move from care settings and homes; and (ii) delays in obtaining needed medical support because of the enormous destruction caused by the earthquake and tsunami.

However, the radiation levels in most of the evacuated areas were not greater than the natural radiation levels in high background areas elsewhere in the world where no adverse health effect is evident.

In its December 2018 report , the Fukushima prefectural government said that the number of ‘indirect’ deaths in the prefecture was greater than the number (1829) killed in the earthquake and tsunami. It put the figure then at 2259 (since revised up to 2313) as determined by municipal panels that examine links between the disaster’s aftermath and deaths. The figure is greater than for Iwate and Miyagi prefectures, with 469 and 929 respectively, though they had much higher loss of life in the earthquake and tsunami – over 14,000. The disparity is attributed to the older age group involved among Fukushima’s evacuated earthquake/tsunami survivors, about 90% of indirect deaths being of people over 66. Causes of indirect deaths include physical and mental stress stemming from long stays at shelters, a lack of initial care as a result of hospitals being disabled by the disaster, and suicides. Evaluation of ‘indirect deaths’ is according to a model developed by Niigata prefecture after the 2004 earthquake there ( Japan Times 20/2/14 ). As of July 2020, over 41,000 people from Fukushima were still living as evacuees.

Evacuees over a period of six years received ¥100,000 (about $1000) per month in psychological suffering compensation. The money was tax-exempt and paid unconditionally. In October 2013, about 84,000 evacuees received the payments. Statistics indicate that an average family of four has received about ¥90 million ($900,000) in compensation from Tepco. As of January 2021 the Fukushima accident evacuees had received ¥9.7 trillion in personal and property compensation.

The Fukushima prefecture had 17,000 government-financed temporary housing units for some 29,500 evacuees from the accident. The prefectural government said residents could continue to use these until March 2015 ( Japan Times 17/11/13 ). The number compared with very few built in Miyagi, Iwate and Aomori prefectures for the 222,700 tsunami survivor refugees there.

In April 2019, the first residents of Okuma, the closest town to the plant, were allowed to return home. In August 2022 the last remaining evacuation order – for Futaba, the town that hosts the Fukushima plant – was lifted.

According to a survey released by the prefectural government in April 2017, the majority of people who voluntarily evacuated their homes after the accident and who are now living outside of Fukushima prefecture do not intend to return. A Mainichi report said that 78.2% of respondents to the survey preferred to continue living in the area to which they had moved, while only 18.3% intended to move back to the prefecture. Of the voluntary evacuees still living in Fukushima prefecture, 23.6% planned to stay where they were, while 66.6% hoped to return to their original homes.

An August 2012 Reconstruction Agency report also considered workers at Fukushima power plant. Of almost 1500 surveyed, many were stressed, due to evacuating their homes (70%), believing they had come close to death (53%), the loss of homes in the tsunami (32%), deaths of colleagues (20%) and of family members (6%) mostly in the tsunami. The death toll directly due to the nuclear accident or radiation exposure remained zero, but stress and disruption due to the continuing evacuation remains high.

Tokyo’s Board of Audit reported in October 2013 that 23% of recovery funding – about ¥1.45 trillion ($14.5 billion) – had been misappropriated. Some 326 out of about 1400 projects funded had no direct relevance to the natural disaster or Fukushima Daiichi accident (Mainichi 1/11/13).

Summary : Many evacuated people remain unable to fully return home due to government-mandated restrictions based on conservative radiation exposure criteria. 2313 premature disaster-related deaths were caused by the evacuations, with 90% of the deaths occuring in people aged 66 and older. Decontamination work is proceeding while radiation levels decline naturally. The October 2013 IAEA report made clear that many evacuees should be allowed to return home. As of July 2020, over 41,000 people from Fukushima were still living as evacuees.

Managing contaminated water

Removing contaminated water from the reactor and turbine buildings had become the main challenge by week 3, along with contaminated water in trenches carrying cabling and pipework. This was both from the tsunami inundation and leakage from reactors. Run-off from the site into the sea was also carrying radionuclides well in excess of allowable levels. By the end of March all storages around the four units – basically the main condenser units and condensate tanks – were largely full of contaminated water pumped from the buildings.

Accordingly, with government approval, Tepco over 4-10 April released to the sea about 10,400 cubic metres of slightly contaminated water (0.15 TBq total) in order to free up storage for more highly-contaminated water from unit 2 reactor and turbine buildings which needed to be removed to make safe working conditions. Unit 2 was the main source of contaminated water, though some of it comes from drainage pits. NISA confirmed that there was no significant change in radioactivity levels in the sea as a result of the 0.15 TBq discharge in April 2011.

By the end of June 2011, Tepco had installed 109 concrete panels to seal the water intakes of units 1-4, preventing contaminated water leaking to the harbour. From mid-June some treatment with zeolite of seawater at 30 m 3 /hr was being undertaken near the water intakes for units 2&3, inside submerged barriers installed in April. From October, a steel water shield wall was built on the sea frontage of units 1-4. It extends about one kilometre, and down to an impermeable layer beneath two permeable strata which potentially leak contaminated groundwater to the sea. The inner harbour area which has some contamination is about 30 ha in area. The government in September 2013 said: “At present, statistically-significant increase of radioactive concentration in the sea outside the port of the Tepco’s Fukushima Daiichi NPS has not been detected.” And also: “The results of monitoring of seawater in Japan are constantly below the standard of 10 Bq/L” (the WHO standard for Cs-137 in drinking water). In 2012 the Japanese standard for caesium in food supply was dropped from 500 to 100 Bq/kg. In July-August 2014 only 0.6% of fish caught offshore from the plant exceeded this lower level, compared with 53% in the months immediately following the accident.

Long-term management and disposal

Tepco in 2011 built a new wastewater treatment facility to treat contaminated water. The company used both US proprietary adsorption and French conventional technologies in the new 1200 m 3 /day treatment plant. A supplementary and simpler SARRY (simplified active water retrieve and recovery system) plant to remove caesium using Japanese technology and made by Toshiba and The Shaw Group was installed and commissioned in August 2011. These plants reduce caesium from about 55 MBq/L to 5.5 kBq/L – about ten times better than designed. Desalination is necessary on account of the seawater earlier used for cooling, and the 1200 m 3 /day desalination plant produces 480 m 3 of clean water while 720 m 3 goes to storage. A steady increase in volume of the stored water (about 400 m 3 /d net) is due to groundwater finding its way into parts of the plant and needing removal and treatment.

Some 1000 storage tanks were set up progressively after the accident, including initially 350 steel tanks with rubber seams, each holding 1200 m 3 . A few of these developed leaks in 2013.

Early in 2013 Tepco started to test and commission the Advanced Liquid Processing System ( ALPS ), developed by EnergySolutions and Toshiba. Each of six trains is capable of processing 250 m 3 /day to remove 62 remaining radioisotopes. By the end of 2014, an ALPS of 500 m 3 /d had been added, making total capacity 2000 m 3 /d. The NRA approved the extra capacity in August 2014.

Earlier in September 2013 report from the Atomic Energy Society of Japan recommended diluting the ALPS-treated water with seawater and releasing it to the sea at the legal discharge concentration of 0.06 MBq/L, with monitoring to ensure that normal background tritium levels of 10 Bq/L are not exceeded. (The WHO drinking water guideline is 0.01 MBq/L tritium.) The IAEA supports release of tritiated water to the ocean, as does Dale Klein, chairman of Tepco’s Nuclear Reform Monitoring Committee (NRMC) and former chairman of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

ALPS is a chemical system which removes radionuclides to below legal limits for release. However, because tritium is contained in water molecules, ALPS cannot remove it, which gives rise to questions about the discharge of treated water to the sea. Tritium is a weak beta-emitter which does not bio-accumulate (half-life 12 years), and its concentration has levelled off at about 1 MBq/L in the stored water, with dilution from groundwater balancing further release from the fuel debris.

In 2014 a new Kurion strontium removal system was commissioned. This is mobile and can be moved around the tank groups to further clean up water which has been treated by ALPS.

In June 2015 108 m 3 /day of clean water was being circulated through each reactor (units 1-3). Collected water from them, with high radioactivity levels, was being treated for caesium removal and re-used. Apart from this recirculating loop, the cumulative treated volume was then 1.232 million cubic metres. In storage onsite was 459,000 m 3 of fully treated water (by ALPS), and 190,000 m 3 of partially-treated water (strontium removed), which was being added to at 400 m 3 /day due to groundwater inflow. Almost 600 m 3 of sludge from the water treatment was stored in shielded containers.

In 2016 Kurion (now owned by Veolia) completed a demonstration project for tritium removal at low concentrations, with its new Modular Detritiation System (MDS),* in response to a ¥1 billion commission from METI.

* In this, an electrolyser produces hydrogen and oxygen, with the tritium reporting in the hydrogen. This is fed through a catalytic exchange column with a little water which preferentially takes up the tritium. The concentrated tritiated water is fed through a ‘getter bed’ of dry metal hydrate, where the tritium replaces hydrogen, and the material is stored, being stable up to 500 °C. It can be incorporated into concrete and disposed as low-level waste. The tritium is concentrated 1000 to 20,000 times. The MDS is the first system to be able economically to treat large volumes of water with low tritium concentrations, and builds on existing heavy water tritium removal systems. Each module treats up to 7200 litres per day.

In November 2019 the trade and industry ministry stated that annual radiation levels from the release of the tritium-tainted water are estimated at between 0.052 and 0.62 microsieverts if it were disposed of at sea and 1.3 microsieverts if it were released into the atmosphere, compared with the 2100 microsieverts (2.1 mSv) that humans are naturally exposed to annually.

In March 2020, TEPCO released a study in relation to two disposal methods of the ALPS-treated water – discharge into the sea and vapour discharge.

In April 2021 the Japanese government confirmed that the water would be released into the sea in 2023. In August 2021 Tepco announced plans for the construction of an undersea tunnel about 1 kilometre in length, which will allow the release of the water into an area where no fishing rights are in place. In May 2022 the NRA endorsed Tepco’s plans.

ALPS-treated water is currently stored in more than 1000 tanks onsite with a storage capacity of 1.37 million cubic metres which are expected to reach full capacity by late 2023 or early 2024. Some of the ALPS treated water will require secondary processing to further reduce concentrations of radionuclides in line with government requirements.

In August 2023 the Japanese government asked Tepco to begin preparations for the release of the treated water, with the first water set to be discharged from 24 August 2023. Tepco plans to discharge the water using a two-step process. First, a small amount of treated water will be diluted with seawater and stored in a vertical discharge shaft in order to sample, measure and verify the tritium levels of the water. The water will then be discharged into the sea via the 1km undersea tunnel. The IAEA opened an office at the Fukushima Daiichi plant in July 2023 in order to continuously monitor and assess the activities related to the release of the treated water and ensure alignment with safety standards. The IAEA will also provide real-time monitoring data.

Apart from the above-ground water treatment activity, there is now a groundwater bypass to reduce the groundwater level above the reactors by about 1.5 metres, pumping from 12 wells and from May 2014, discharging the uncontaminated water into the sea. This prevents some of it flowing into the reactor basements and becoming contaminated. In addition, an impermeable wall was constructed on the sea-side of the reactors, and inside this a frozen soil wall was created to further block water flow into the reactor buildings.

In October 2013 guidelines for rainwater release from the site allowed Tepco to release water to the sea without specific NRA approval as long as it conformed to activity limits. Tepco has been working to 25 Bq/L caesium and 10 Bq/L strontium-90.

Summary: A large amount of contaminated water has accumulated onsite and has been treated to remove radioactive elements, apart from tritium. In April 2021, the Japanese government confirmed that the water would be released into the sea. Some radioactivity has already been released to the sea, but this has mostly been low-level and it has not had any significant impact beyond the immediate plant structures. Concentrations outside these structures have been below regulatory levels since April 2011. The release of the treated water will commence in August 2023 and will be continuously monitored by IAEA staff present at the site.

IRID and NDF involvement

The International Research Institute for Nuclear Decommissioning ( IRID ) was set up in August 2013 Japan by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA), Japanese utilities and reactor vendors, with a focus on Fukushima Daiichi 1-4.

In September 2013 IRID called for submissions on the management of contaminated water at Fukushima. In particular, proposals were sought for dealing with: the accumulation of contaminated water (in storage tanks, etc ); the treatment of contaminated water including tritium removal; the removal of radioactive materials from the seawater in the plant's 30 ha harbour; the management of contaminated water inside the buildings; measures to block groundwater from flowing into the site; and, understanding the flow of groundwater. Responses were submitted to the government in November.

In December 2013 IRID called for innovative proposals for removing fuel debris from units 1-3 about 2020.

In August 2014 the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation (NDF) was set up by the government as a planning body with management support for R&D projects, taking over IRID’s planning role. It works with IRID, whose focus now is on developing mid- and long-term decommissioning technologies. The NDF also works with Tepco Fukushima Daiichi D&D Engineering Co., which has responsibility for operating the actual decommissioning work there. The NDF will be the main body interacting with the government (METI) to implement policy.

Fukushima Daiichi 5&6

Units 5&6, in a separate building, also lost power on 11 March due to the tsunami. They were in 'cold shutdown' at the time, but still requiring pumped cooling. One air-cooled diesel generator at unit 6 was located higher and so survived the tsunami and enabled repairs on Saturday 19, allowing full restoration of cooling for units 5&6. While the power was off their core temperature had risen to over 100 °C (128 °C in unit 5) under pressure, and they had been cooled with normal water injection. They were restored to cold shutdown by the normal recirculating system on 20 March, and mains power was restored on 21-22 March.

In September 2013 Tepco commenced work to remove the fuel from unit 6. Prime minister Abe then called for Tepco to decommission both units. Tepco announced in December 2013 that it would decommission both units from the end of January 2014. Unit 5 was a 760 MWe BWR the same as units 2-4, and unit 6 was larger – 1067 MWe. They entered commercial operation in 1978 and 1979 respectively. It is proposed that they will be used for training.

Remediation on site and decommissioning units 1-4

Tepco published a six- to nine-month plan in April 2011 for dealing with the disabled Fukushima reactors, and updated this several times subsequently. Remediation over the first couple of years proceeded approximately as planned. In August 2011 Tepco announced its general plan for proceeding with removing fuel from the four units, initially from the spent fuel ponds and then from the actual reactors. At the end of 2013 Tepco announced the establishment of an internal entity to focus on measures for decommissioning units 1-6 and dealing with contaminated water. The new company, Fukushima Daiichi Decontamination & Decommissioning Engineering Company, commenced operations in April 2014.

In June 2015 the government revised the decommissioning plan for the second time, though without major change. It clarified milestones to accomplish preventive and multi-layered measures, involving the three principles of removing the source of the contamination, isolating groundwater from the contamination source, and preventing leakage of the contaminated water. It included a new goal of cutting the amount of groundwater flowing into the buildings to less than 100 m 3 per day by April 2016. The schedule for fuel removal from the pond at unit 1 was postponed from late FY17 to FY20, while that for unit 2 was delayed from early FY20 to later the same fiscal year, and that at unit 3 from early FY15 to FY17. Fuel debris removal was to begin in 2021, as before. In September 2017 the government updated the June 2015 decommissioning roadmap, with no changes to the framework, and confirming first removal of fuel debris from unit 1 in 2021. Treatment of all contaminated water accumulated in the reactor buildings was to be completed by 2020.

However, Tepco’s latest roadmap shows fuel removal from the pond at unit 1 is now expected FY27-28, and from unit 2 FY24-FY26. For unit 3, fuel removal was completed in February 2021.

Tepco has a website giving updates on decommissioning work and environmental monitoring.

Storage ponds : Debris has been removed from the upper parts of the reactor buildings using large cranes and heavy machinery. Casks to transfer the removed fuel to the central spent fuel facility have been designed and manufactured using existing cask technology.

In July 2012 two unused fuel assemblies were removed from unit 4 pond, and were found to be in good shape, with no deformation or corrosion. Tepco started removal of both fresh and used fuel from the pond in November 2013, 22 assemblies at a time in each cask, with 1331 used and 202 new ones to be moved. This was uneventful, and the task continued through 2014. By 22 December 2014, all 1331 used as well as all 202 new fuel assemblies had been moved in 71 cask shuttles without incident. All of the radioactive used fuel was removed by early November, eliminating a significant radiological hazard on the site. The used fuel went to the central storage pond, from which older assemblies were transferred to dry cask storage. The fresh fuel assemblies are stored in the pool of the undamaged unit 6.

Tepco completed moving fuel from unit 3 in February 2021. It will now focus on 292 used fuel assemblies and 100 new ones from unit 1, and then 587 used assemblies and 28 new ones from unit 2 will be transferred. The NRA has expressed concern about the unit 1 used fuel.

Reactors 1-3 order of work : The locations of leaks from the primary containment vessels (PCVs) and reactor buildings should first be identified using manual and remotely controlled dosimeters, cameras, etc. , then the conditions inside the PCVs should be indirectly analysed from the outside via measurements of gamma rays, echo soundings, etc . Any leakage points will be repaired and both reactor vessels (RPVs) and PCVs filled with water sufficient to achieve shielding. Then the vessel heads will be removed. The location of melted fuel and corium will then be established. In particular, the distribution of damaged fuel believed to have flowed out from the RPVs into PCVs will be ascertained, and it will be sampled and analysed. After examination of the inside of the reactors, states of the damaged fuel rods and reactor core internals, sampling will be done and the damaged core material will be removed from the RPVs as well as from the PCVs. Updated plans are on the IRID website.

The four reactors will be completely demolished in 30-40 years – much the same timeframe as for any nuclear plant. As noted above, units 5&6 commenced decommissioning in 2014 and will be used for training.

Earlier, consortia led by both Hitachi-GE and Toshiba submitted proposals to Tepco for decommissioning units 1-4. This would generally involve removing the fuel and then sealing the units for a further decade or two while the activation products in the steel of the reactor pressure vessels decay. They can then be demolished. Removal of the very degraded fuel will be a long process in units 1-3, but will draw on experience at Three Mile Island in the USA.

Tepco has allocated ¥207 billion ($2.5 billion) in its accounts for decommissioning units 1-4. In March 2020, Tepco announced that ¥1.37 trillion ($12.6 billion) would be required for the removal of damaged fuel from units 2&3, with no estimates being made for the fuel in unit 1 which suffered the most damage of the three reactors.

The government has allocated ¥1150 billion ($15 billion) for decontamination in the region, with the promise of more if needed.

The Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE) calculated that as of January 2017 Tepco needed an estimated ¥22,000 billion ($190 billion), double the original estimate, to implement fuel debris removal, cleanup and for compensation to firms and individuals in Fukushima prefecture. Of this amount, Tepco would pay ¥16 trillion. Other Japanese nuclear operators would pay ¥4 trillion through the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corp (NDF), and the Japanese government would pay ¥2 trillion for cleanup in Fukushima prefecture.

A 12-member international expert team assembled by the IAEA at the request of the Japanese government carried out a fact-finding mission in October 2011 on remediation strategies for contaminated land. Its report focused on the remediation of the affected areas outside of the 20 km restricted area. The team said that it agreed with the prioritization and the general strategy being implemented, but advised the government to focus on actual dose reduction. They should "avoid over-conservatism" which "could not effectively contribute to the reduction of exposure doses" to people. It warned the government against being preoccupied with "contamination concentrations ... rather than dose levels," since this "does not automatically lead to reduction of doses for the public." The report also called on the Japanese authorities to "maintain their focus on remediation activities that bring the best results in reducing the doses to the public." A follow-up mission was carried out in October 2013.

Fukushima Daini plant

The four units at Fukushima Daini were shut down automatically due to the earthquake. The tsunami – here only 9 m high – affected the generators and there was major interruption to cooling due to damaged heat exchangers, so the reactors were almost completely isolated from their ultimate heat sink. Damage to the diesel generators was limited and also the earthquake left one of the external power lines intact, avoiding a station blackout as at Daiichi units 1-4. Staff laid and energized 8.8 km of heavy-duty electric cables in 30 hours to supplement power.

In units 1, 2&4 there were cooling problems still evident on Tuesday 15. Unit 3 was undamaged and continued to 'cold shutdown' status on the 12th, but the other units suffered flooding to pump rooms where the equipment transfers heat from the reactor heat removal circuit to the sea. Pump motors were replaced in less than 30 hours. All units achieved 'cold shutdown' by 16 March, meaning core temperature less than 100 °C at atmospheric pressure (101 kPa), but still requiring some water circulation. The almost complete loss of ultimate heat sink for a day proved a significant challenge, but the cores were kept fully covered.

Radiation monitoring figures remained at low levels, little above background.

There was no technical reason for the Fukushima Daini plant not to restart. However, Tepco in October 2012 said it planned to transfer the fuel from the four reactors to used fuel ponds, and this was done. In February 2015 the prime minister said that restarting the four units was essentially a matter for Tepco to decide. In July 2019 Tepco announced its decision to decommission the four reactors.

International Nuclear Event Scale assessment

Japan's Nuclear & Industrial Safety Agency originally declared the Fukushima Daiichi 1-3 accident as level 5 on the International Nuclear Events Scale (INES) – an accident with wider consequences, the same level as Three Mile Island in 1979. The sequence of events relating to the fuel pond at unit 4 was rated INES level 3 – a serious incident.

However, a month after the tsunami the NSC raised the rating to level 7 for units 1-3 together, 'a major accident', saying that a re-evaluation of early radioactive releases suggested that some 630 PBq of I-131 equivalent had been discharged, mostly in the first week. This then matched the criterion for level 7. In early June NISA increased its estimate of releases to 770 PBq, from about half that, though in August the NSC lowered this estimate to 570 PBq.

For Fukushima Daini, NISA declared INES level 3 for units 1, 2, 4 – each a serious incident.

Accident liability and compensation