- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Early life and works

Mature life and works.

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Endowment for the Humanities - Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Poets.org - Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Poetry Foundation - Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Age of the Sage - Transmitting the Wisdoms of the Ages - Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Literary Devices - Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Official Site of The Home of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Ralph Waldo Emerson - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

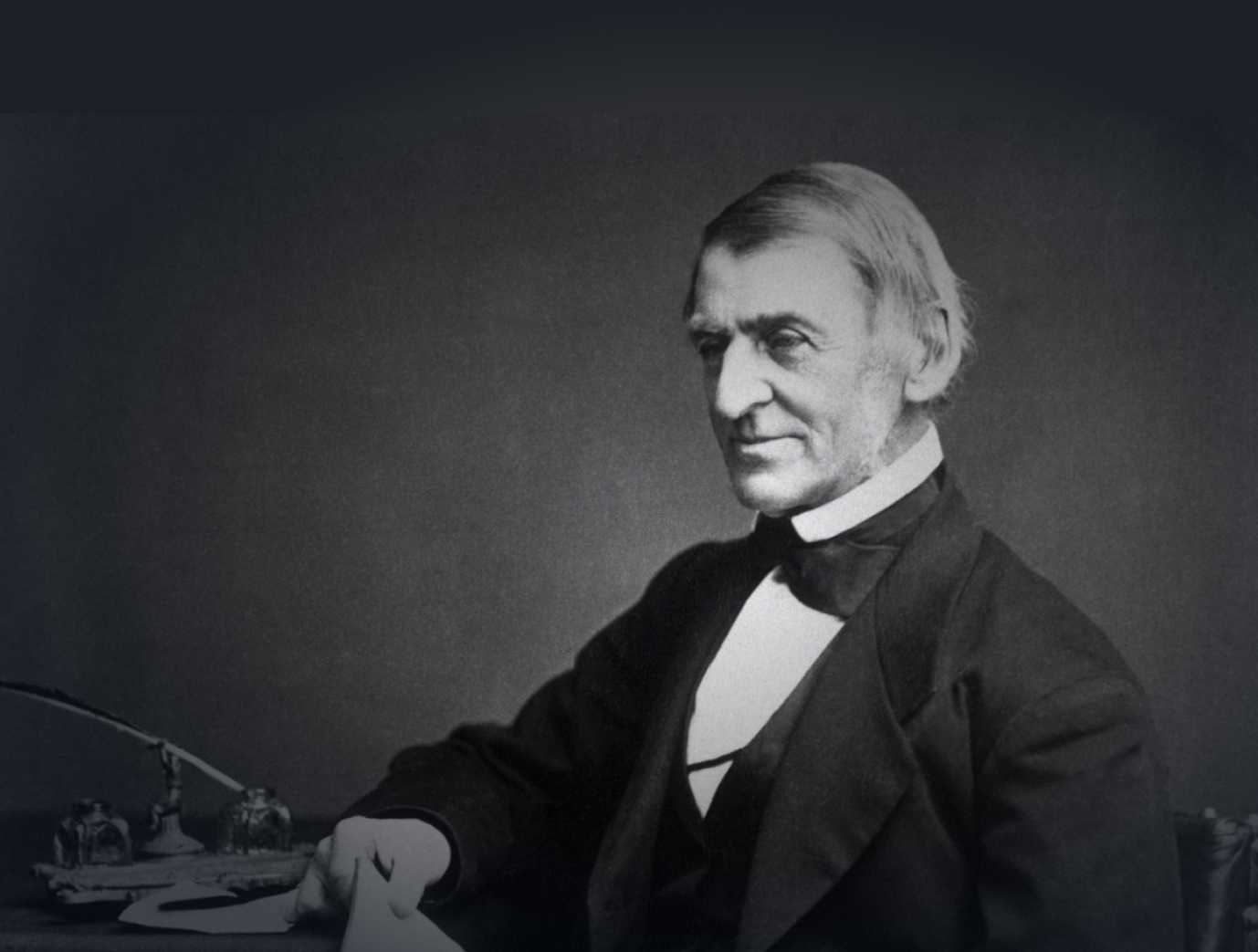

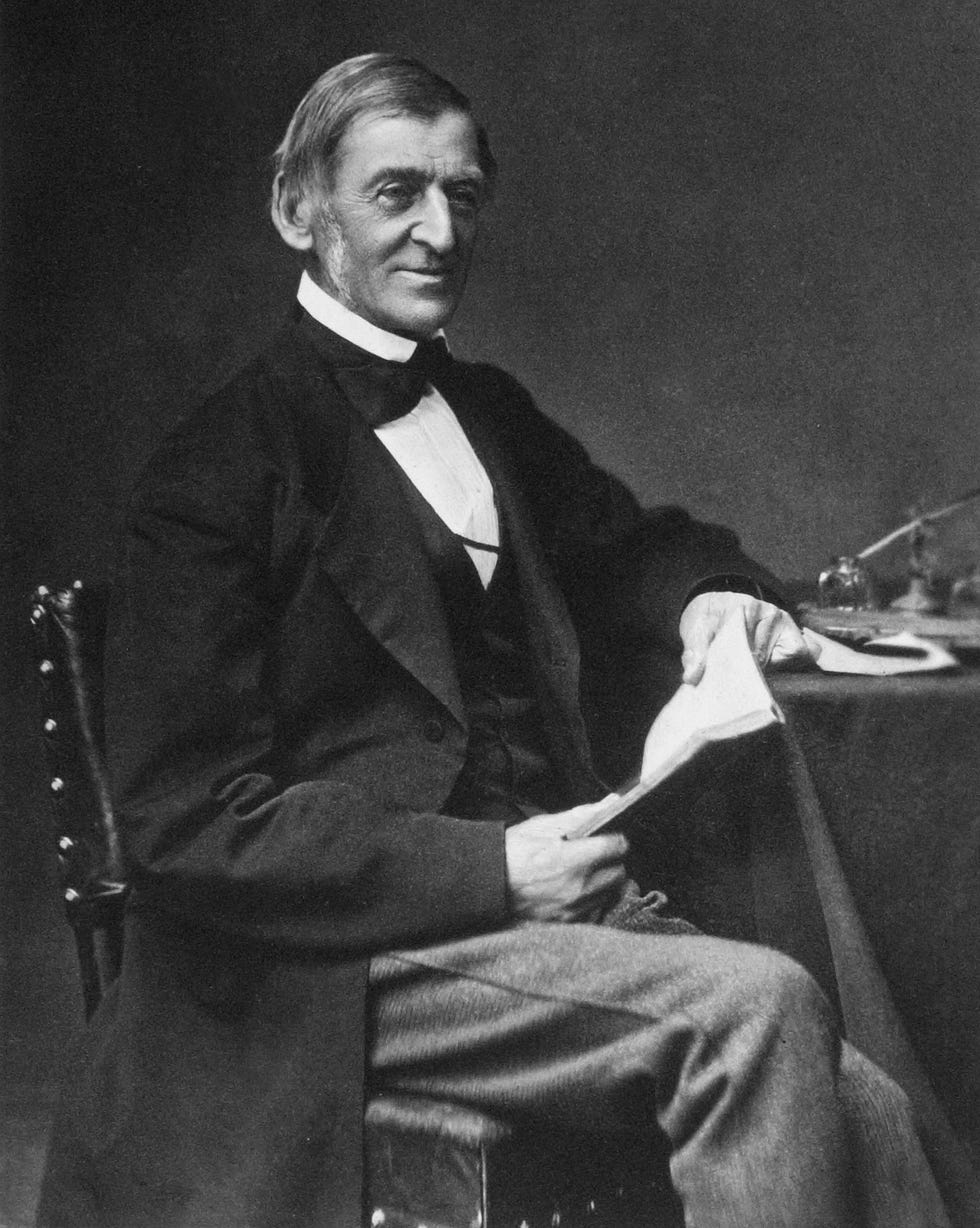

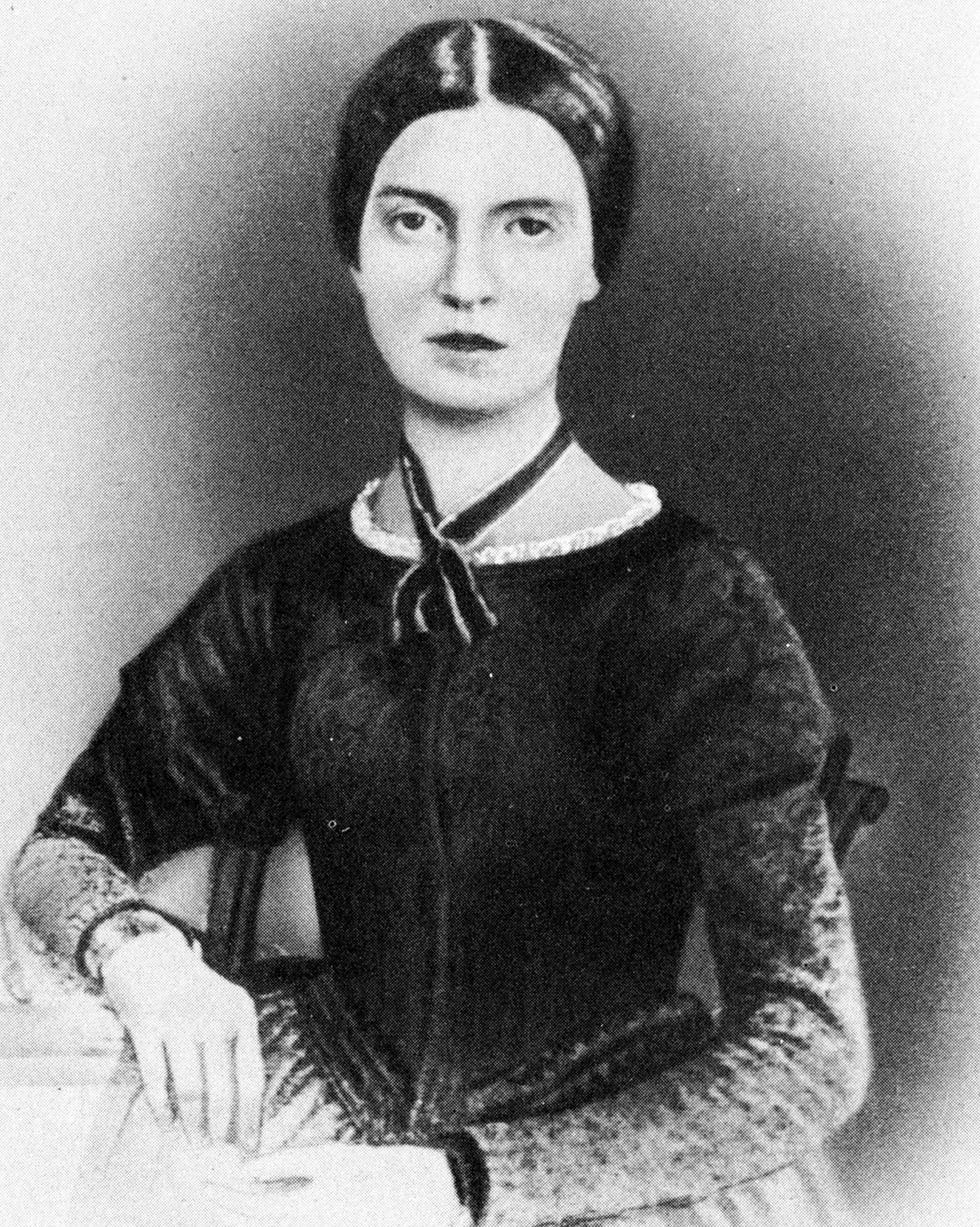

Ralph Waldo Emerson (born May 25, 1803, Boston , Massachusetts , U.S.—died April 27, 1882, Concord , Massachusetts) was an American lecturer, poet, and essayist, the leading exponent of New England Transcendentalism .

Emerson was the son of the Reverend William Emerson, a Unitarian clergyman and friend of the arts. The son inherited the profession of divinity, which had attracted all his ancestors in direct line from Puritan days. The family of his mother, Ruth Haskins, was strongly Anglican, and among influences on Emerson were such Anglican writers and thinkers as Ralph Cudworth , Robert Leighton , Jeremy Taylor , and Samuel Taylor Coleridge .

On May 12, 1811, Emerson’s father died, leaving the son largely to the intellectual care of Mary Moody Emerson, his aunt, who took her duties seriously. In 1812 Emerson entered the Boston Public Latin School, where his juvenile verses were encouraged and his literary gifts recognized. In 1817 he entered Harvard College (later Harvard University), where he began his journals, which may be the most remarkable record of the “march of Mind” to appear in the United States . He graduated in 1821 and taught school while preparing for part-time study in the Harvard Divinity School.

Though Emerson was licensed to preach in the Unitarian community in 1826, illness slowed the progress of his career, and he was not ordained to the Unitarian ministry at the Second Church, Boston, until 1829. There he began to win fame as a preacher, and his position seemed secure. In 1829 he also married Ellen Louisa Tucker. When she died of tuberculosis in 1831, his grief drove him to question his beliefs and his profession. But in the previous few years Emerson had already begun to question Christian doctrines. His older brother William, who had gone to Germany, had acquainted him with the new biblical criticism and the doubts that had been cast on the historicity of miracles. Emerson’s own sermons, from the first, had been unusually free of traditional doctrine and were instead a personal exploration of the uses of spirit, showing an idealistic tendency and announcing his personal doctrine of self-reliance and self-sufficiency. Indeed, his sermons had divested Christianity of all external or historical supports and made its basis one’s private intuition of the universal moral law and its test a life of virtuous accomplishment. Unitarianism had little appeal to him by now, and in 1832 he resigned from the ministry.

When Emerson left the church, he was in search of a more certain conviction of God than that granted by the historical evidences of miracles. He wanted his own revelation—i.e., a direct and immediate experience of God. When he left his pulpit he journeyed to Europe. In Paris he saw Antoine-Laurent de Jussieu ’s collection of natural specimens arranged in a developmental order that confirmed his belief in man’s spiritual relation to nature. In England he paid memorable visits to Samuel Taylor Coleridge , William Wordsworth , and Thomas Carlyle . At home once more in 1833, he began to write Nature and established himself as a popular and influential lecturer. By 1834 he had found a permanent dwelling place in Concord, Massachusetts, and in the following year he married Lydia Jackson and settled into the kind of quiet domestic life that was essential to his work.

The 1830s saw Emerson become an independent literary man. During this decade his own personal doubts and difficulties were increasingly shared by other intellectuals . Before the decade was over his personal manifestos— Nature , “The American Scholar,” and the divinity school Address —had rallied together a group that came to be called the Transcendentalists, of which he was popularly acknowledged the spokesman. Emerson helped initiate Transcendentalism by publishing anonymously in Boston in 1836 a little book of 95 pages entitled Nature . Having found the answers to his spiritual doubts, he formulated his essential philosophy, and almost everything he ever wrote afterward was an extension, amplification, or amendment of the ideas he first affirmed in Nature .

Emerson’s religious doubts had lain deeper than his objection to the Unitarians’ retention of belief in the historicity of miracles. He was also deeply unsettled by Newtonian physics’ mechanistic conception of the universe and by the Lockean psychology of sensation that he had learned at Harvard. Emerson felt that there was no place for free will in the chains of mechanical cause and effect that rationalist philosophers conceived the world as being made up of. This world could be known only through the senses rather than through thought and intuition; it determined men physically and psychologically; and yet it made them victims of circumstance, beings whose superfluous mental powers were incapable of truly ascertaining reality.

Emerson reclaimed an idealistic philosophy from this dead end of 18th-century rationalism by once again asserting the human ability to transcend the materialistic world of sense experience and facts and become conscious of the all-pervading spirit of the universe and the potentialities of human freedom. God could best be found by looking inward into one’s own self, one’s own soul, and from such an enlightened self-awareness would in turn come freedom of action and the ability to change one’s world according to the dictates of one’s ideals and conscience . Human spiritual renewal thus proceeds from the individual’s intimate personal experience of his own portion of the divine “oversoul,” which is present in and permeates the entire creation and all living things, and which is accessible if only a person takes the trouble to look for it. Emerson enunciates how “reason,” which to him denotes the intuitive awareness of eternal truth, can be relied upon in ways quite different from one’s reliance on “understanding”—i.e., the ordinary gathering of sense-data and the logical comprehension of the material world. Emerson’s doctrine of self-sufficiency and self-reliance naturally springs from his view that the individual need only look into his own heart for the spiritual guidance that has hitherto been the province of the established churches. The individual must then have the courage to be himself and to trust the inner force within him as he lives his life according to his intuitively derived precepts.

Obviously these ideas are far from original, and it is clear that Emerson was influenced in his formulation of them by his previous readings of Neoplatonist philosophy, the works of Coleridge and other European Romantics , the writings of Emmanuel Swedenborg , Hindu philosophy, and other sources. What set Emerson apart from others who were expressing similar Transcendentalist notions were his abilities as a polished literary stylist able to express his thought with vividness and breadth of vision. His philosophical exposition has a peculiar power and an organic unity whose cumulative effect was highly suggestive and stimulating to his contemporary readers’ imaginations.

In a lecture entitled “The American Scholar” (August 31, 1837), Emerson described the resources and duties of the new liberated intellectual that he himself had become. This address was in effect a challenge to the Harvard intelligentsia, warning against pedantry, imitation of others, traditionalism, and scholarship unrelated to life. Emerson’s “ Address at Divinity College,” Harvard University, in 1838 was another challenge, this time directed against a lifeless Christian tradition, especially Unitarianism as he had known it. He dismissed religious institutions and the divinity of Jesus as failures in man’s attempt to encounter deity directly through the moral principle or through an intuited sentiment of virtue. This address alienated many, left him with few opportunities to preach, and resulted in his being ostracized by Harvard for many years. Young disciples , however, joined the informal Transcendental Club (founded in 1836) and encouraged him in his activities.

In 1840 he helped launch The Dial , first edited by Margaret Fuller and later by himself, thus providing an outlet for the new ideas Transcendentalists were trying to present to America. Though short-lived, the magazine provided a rallying point for the younger members of the school. From his continuing lecture series, he gathered his Essays into two volumes (1841, 1844), which made him internationally famous. In his first volume of Essays Emerson consolidated his thoughts on moral individualism and preached the ethics of self-reliance , the duty of self-cultivation , and the need for the expression of self. The second volume of Essays shows Emerson accommodating his earlier idealism to the limitations of real life; his later works show an increasing acquiescence to the state of things, less reliance on self, greater respect for society, and an awareness of the ambiguities and incompleteness of genius.

His Representative Men (1849) contained biographies of Plato , Swedenborg, Montaigne , Shakespeare , Napoleon , and Goethe . In English Traits he gave a character analysis of a people from which he himself stemmed. The Conduct of Life (1860), Emerson’s most mature work, reveals a developed humanism together with a full awareness of human limitations. It may be considered as partly confession. Emerson’s collected Poems (1846) were supplemented by others in May-Day (1867), and the two volumes established his reputation as a major American poet.

By the 1860s Emerson’s reputation in America was secure, for time was wearing down the novelty of his rebellion as he slowly accommodated himself to society. He continued to give frequent lectures, but the writing he did after 1860 shows a waning of his intellectual powers. A new generation knew only the old Emerson and had absorbed his teaching without recalling the acrimony it had occasioned. Upon his death in 1882 Emerson was transformed into the Sage of Concord, shorn of his power as a liberator and enrolled among the worthies of the very tradition he had set out to destroy.

Emerson’s voice and rhetoric sustained the faith of thousands in the American lecture circuits between 1834 and the American Civil War . He served as a cultural middleman through whom the aesthetic and philosophical currents of Europe passed to America, and he led his countrymen during the burst of literary glory known as the American renaissance (1835–65). As a principal spokesman for Transcendentalism, the American tributary of European Romanticism , Emerson gave direction to a religious, philosophical, and ethical movement that above all stressed belief in the spiritual potential of every person.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Ralph Waldo Emerson

American poet, essayist, and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson was born on May 25, 1803, in Boston. After studying at Harvard and teaching for a brief time, Emerson entered the ministry. He was appointed to the Old Second Church in his native city, but soon became an unwilling preacher. Unable in conscience to administer the sacrament of the Lord’s Soon after the death of his nineteen-year-old wife of tuberculosis, Emerson resigned his pastorate in 1831.

The following year, Emerson sailed for Europe, visiting Thomas Carlyle and Samuel Taylor Coleridge . Carlyle, the Scottish-born English writer, was famous for his explosive attacks on hypocrisy and materialism, his distrust of democracy, and his highly romantic belief in the power of the individual. Emerson’s friendship with Carlyle was both lasting and significant; the insights of the British thinker helped Emerson formulate his own philosophy.

On his return to New England, Emerson became known for challenging traditional thought. In 1835, he married his second wife, Lydia Jackson, and settled in Concord, Massachusetts. Known in the local literary circle as “The Sage of Concord,” Emerson became the chief spokesman for Transcendentalism, the American philosophic and literary movement. Centered in New England during the nineteenth century, Transcendentalism was a reaction against scientific rationalism.

Emerson’s first book, Nature (1836), is perhaps the best expression of his Transcendentalism, the belief that everything in our world—even a drop of dew—is a microcosm of the universe. His concept of the Over-Soul—a Supreme Mind that every man and woman share—allowed Transcendentalists to disregard external authority and to rely instead on direct experience. “Trust thyself,” Emerson’s motto, became the code of Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, and W. E. Channing. From 1842 to 1844, Emerson edited the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial .

Emerson wrote a poetic prose, ordering his essays by recurring themes and images. His poetry, on the other hand, is often called harsh and didactic. Among Emerson’s most well known works are Essays, First and Second Series (1841, 1844). The First Series includes Emerson's famous essay, “Self-Reliance,” in which the writer instructs his listener to examine his relationship with Nature and God, and to trust his own judgment above all others.

Emerson’s other volumes include Poems (1847), Representative Men (1850), The Conduct of Life (1860), and English Traits (1865). His best-known addresses are The American Scholar (1837) and The Divinity School Address , which he delivered before the graduates of the Harvard Divinity School, shocking Boston’s conservative clergymen with his descriptions of the divinity of man and the humanity of Jesus.

Emerson’s philosophy is characterized by its reliance on intuition as the only way to comprehend reality, and his concepts owe much to the works of Plotinus, Emanuel Swedenborg, and Jakob Böhme. A believer in the “divine sufficiency of the individual,” Emerson was a steady optimist. His refusal to grant the existence of evil caused Herman Melville , Nathaniel Hawthorne , and Henry James, Sr., among others, to doubt his judgment. In spite of their skepticism, Emerson’s beliefs are of central importance in the history of American culture.

Ralph Waldo Emerson died of pneumonia on April 27, 1882.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for “common speech” within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

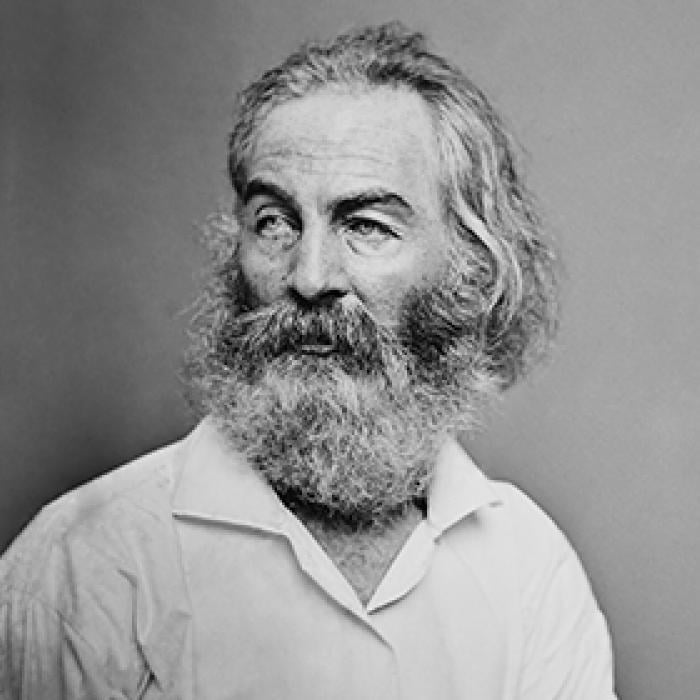

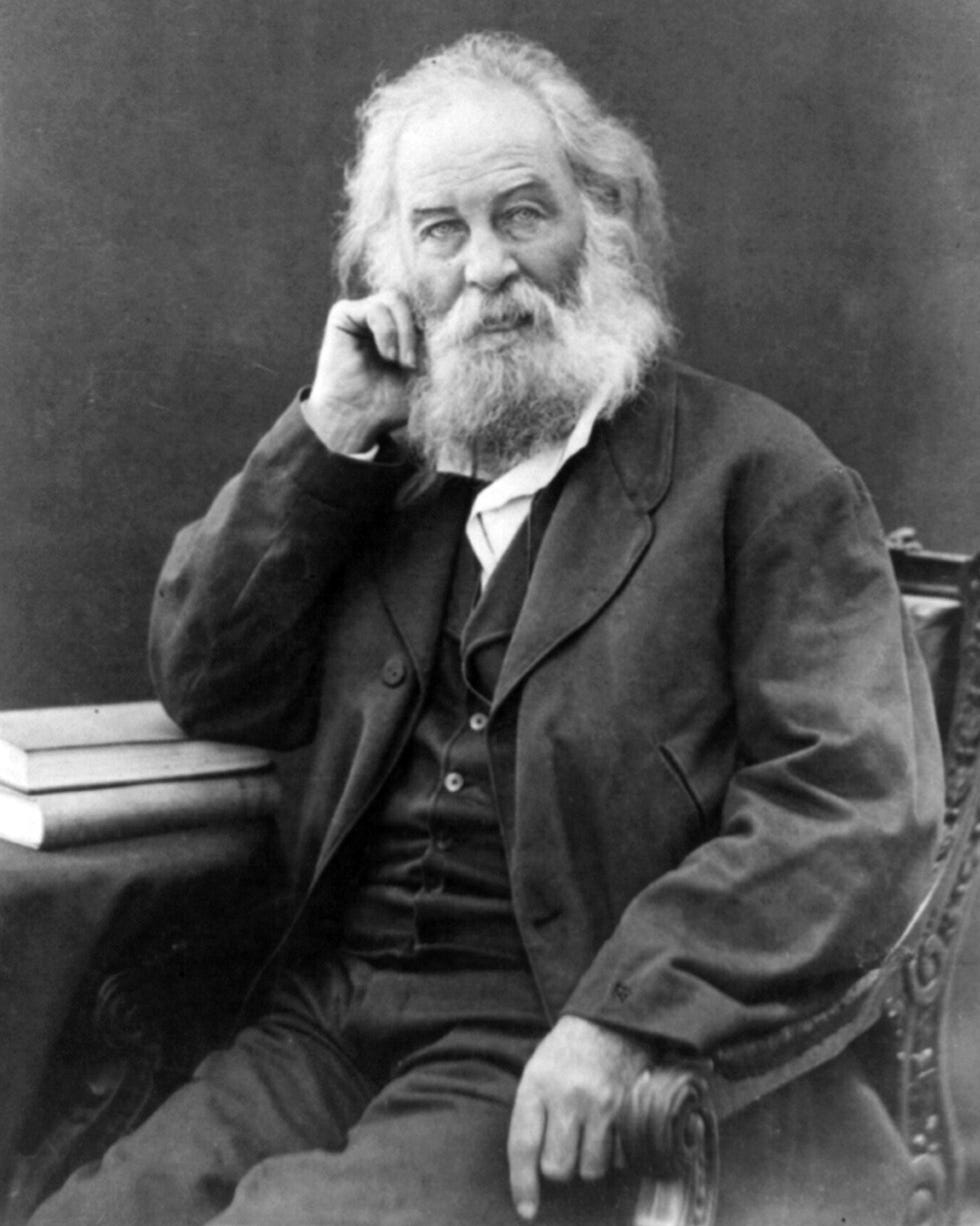

Walt Whitman

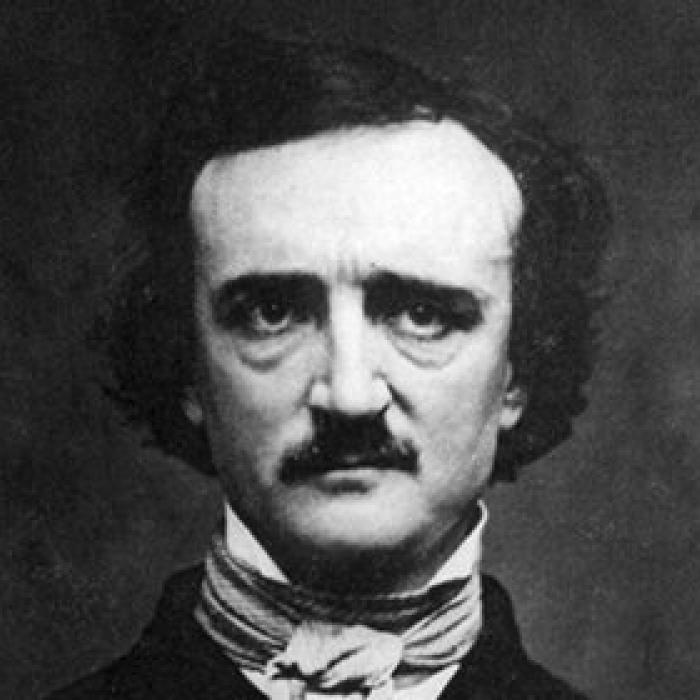

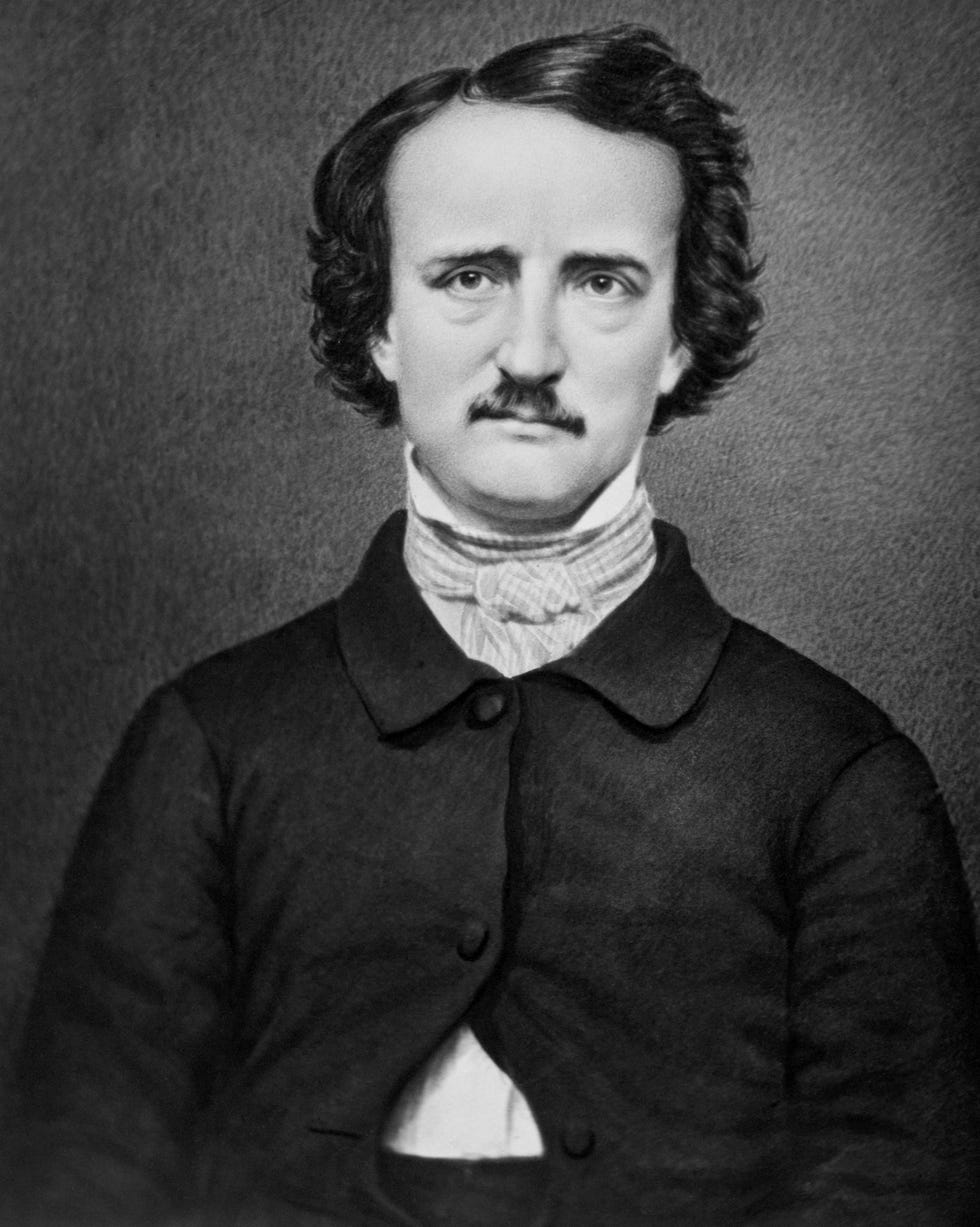

Edgar Allan Poe

Born in 1809, Edgar Allan Poe had a profound impact on American and international literature as an editor, poet, and critic.

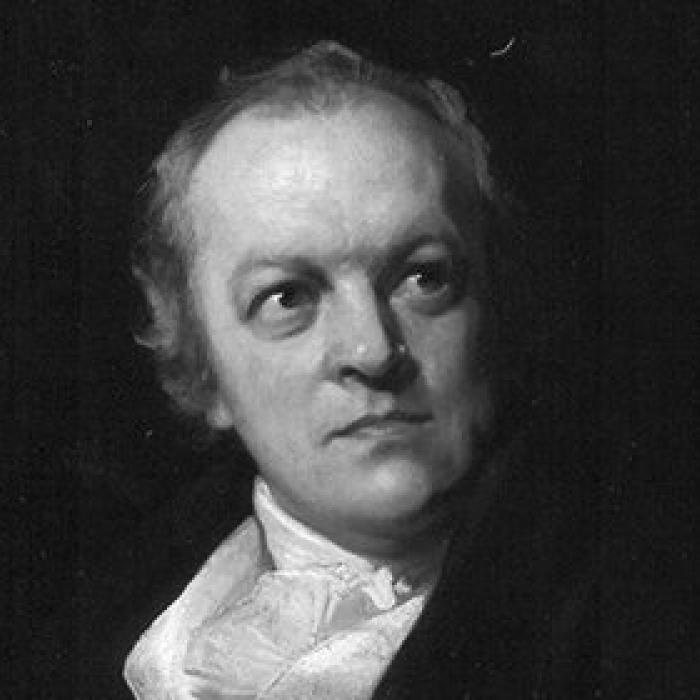

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God "put his head to the window"; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

- Poem Guides

- Poem of the Day

- Collections

- Harriet Books

- Featured Blogger

- Articles Home

- All Articles

- Podcasts Home

- All Podcasts

- Glossary of Poetic Terms

- Poetry Out Loud

- Upcoming Events

- All Past Events

- Exhibitions

- Poetry Magazine Home

- Current Issue

- Poetry Magazine Archive

- Subscriptions

- About the Magazine

- How to Submit

- Advertise with Us

- About Us Home

- Foundation News

- Awards & Grants

- Media Partnerships

- Press Releases

- Newsletters

Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Print this page

- Email this page

Ralph Waldo Emerson—a New England preacher, essayist, lecturer, poet, and philosopher—was one of the most influential writers and thinkers of the 19th century in the United States. Emerson was also the first major American literary and intellectual figure to widely explore, write seriously about, and seek to broaden the domestic audience for classical Asian and Middle Eastern works. He not only gave countless readers their first exposure to non-Western modes of thinking, metaphysical concepts, and sacred mythologies; he also shaped the way subsequent generations of American writers and thinkers approached the vast cultural resources of Asia and the Middle East. Emerson was born on May 25, 1803 in Boston, Massachusetts. As a boy, his first contact with the non-Western world came by way of the merchandise that bustled across the India Wharf in Boston harbor, a major nexus of the Indo-Chinese trade that flourished in New England after the Revolutionary War. Emerson’s first contact with writings from and about the non-Western world came by way of his father, William Emerson, a Unitarian minister with a genteel interest in learning and letters.

In 1817, at the age of 14, Emerson entered Harvard College. While at Harvard, Emerson had little opportunity to study the diverse literary and religious traditions of Asia or the Middle East. The curriculum focused on Greek and Roman writers, British logicians and philosophers, Euclidean geometry and algebra, and post-Enlightenment defenses of revealed religion. As his journals and library borrowing records attest, however, in his spare time, Emerson paid keen attention to the wider European Romantic interest in the “Orient” or the “East,” which to him meant the ancient lands and sacred traditions east of classical Greece, such as Egypt, the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, China, and India. An aspiring poet, Emerson also gravitated to selections of poetry that took up Eastern themes and Eastern poetry, including the works of Saadi and Hafez , which he would embrace in adulthood.

Like other Anglo-American readers of his period, Emerson relied heavily on British colonial agents for his knowledge of India, reading treatises, travelogues, and translations of legal, religious, and poetic texts produced in the wake of Britain’s imperial expansion into India. As a consequence, Emerson’s writing about South Asia (as well as China, Persia, and the Arab world) often traffics in the menagerie of 19th century Euro-American stereotypes and misconceptions. Examples can be found in Emerson’s “Indian Superstition,” a densely allusive poem that he composed for Harvard College’s graduation ceremonies in 1822. In the 156-line poem, Emerson describes how “Superstition,” the personification of religious tyranny in Asia, has enslaved “[D]ishonored India.” With its Romantic primitivism and bombastic imagery, “Indian Superstition” is perhaps closer to caricature than considered literary art. Yet, for all its excess, Emerson’s poem is notable for departing from a common formula of the period according to which a debased India could only be redeemed through Western colonialism. Instead, Emerson urges Indians to resist the shackles of the British Empire as forcefully as they should resist the mental chains of religious superstition. He exhorts ordinary Indians to look upon the example of post-revolution America as an emblem of what a modern democratic nation could achieve. After he graduated from Harvard, Emerson’s enthusiasm for non-Western subjects waned, primarily because he devoted himself to becoming a Unitarian minister. In 1831 Emerson’s wife, Ellen Tucker Emerson, died of tuberculosis, an event that galvanized a series of personal and professional changes in his life. The next year Emerson resigned his pulpit at the Second Church of Boston, publicly citing the fact that he did not believe in the special divinity of Jesus and thus could no longer administer the sacrament of communion. After traveling through Europe, where he met literary luminaries such as William Wordsworth and Thomas Carlyle, Emerson returned to his ancestral home in Concord, Massachusetts. He began a career as a public lecturer, which lasted almost 50 years, and married Lydia Jackson, whom he affectionately referred to as “Mine Asia”—a pun on Asia Minor, the location of the ancient kingdom of Lydia. In 1836 Emerson published Nature, the first major statement of his mature philosophy and a groundbreaking book that catalyzed the Transcendentalist movement in New England. Along with Emerson, the New England Transcendentalists were an eclectic group of religious, literary, educational, and social reformers that included Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Theodore Parker, and Henry David Thoreau. The movement grew out of Unitarianism in the greater Boston area; was deeply influenced by British and German Romanticism, especially as interpreted by Samuel Taylor Coleridge; and revolved around a form of philosophical and spiritual idealism that valued intuition over the senses.

With the publication of his Essays in 1841 and Essays: Second Series in 1844, Emerson emerged as a trans-Atlantic literary celebrity. In his essays from this period Emerson did not explicitly take up Eastern subjects or ideas; however, scholars agree that there are similarities between Emerson’s “Over-Soul” in his 1841 essay of that name and the Hindu conception of Brahman . Scholars also agree that there are similarities between Emerson’s belief described in his 1841 essay “Compensation” and the Hindu doctrine of karma . Moreover, in his published writings during this period, Emerson cited maxims, referred to prominent figures, and otherwise incorporated allusions drawn from Asian and Middle Eastern literatures with surprising regularity. He added these “lustres” to his nonfiction writing for at least two reasons. First, by treating non-Western texts with the same respect afforded cultural authorities in the Western traditions, he could disrupt the parochial expectations of his American and European audiences. Second, by adducing evidence from traditions outside of America and Europe, he could assert the universality of his observations on society, fate, ethics, and philosophy. Emerson’s engagement with Eastern cultural sources is also evident in his poetry from the 1840s. For example, inspired by his reading of Persian verse, Emerson wrote “Saadi” in 1842, a poetic tribute to the aphorist, panegyrist, and lyrical poet of the same name.

When scholars discuss the limitations of Emerson’s writing about the East, they often refer to the essay “Plato; or the Philosopher,” published in Representative Men in 1850. In that volume, Emerson argues that the Greek philosopher brought together the two “cardinal facts” at the core of all philosophy: Unity and Variety. According to Emerson, the tendency to “dwell in the conception of the fundamental Unity” is primarily an Eastern trait, while the impulse toward variety is a Western one. Emerson praises in Plato what he probably valued in himself—an ability to synthesize the best aspects of unity and variety, immensity and detail, East and West. And yet Emerson’s conceptualization of the East in the “Plato” essay poses problems that are worth noting.

As scholars have observed, when Emerson claims to speak about “Asia,” he seems to have India in mind (that is, the country with the “social institution of caste”). It is a muddling of distinctions that suggests Emerson was unconcerned about the vital differences among the cultures of Asia and the Middle East. Emerson also eschews political or economic comparisons in favor of idealized intellectual ones, supporting the notion that “the East” was more for him an abstract idea than a place inhabited by actual people. Also, even though Emerson purports to offer a balanced view of an East that “[loves] infinity” and a West that [“delights] in boundaries,” his language seems to favor Europe—with its activity, creativity, “discipline,” “arts, inventions, trade, freedom”—over Asia, with its “immovable institutions” and “deaf, unimplorable, immense fate.” Emerson’s vague and polarized thinking in “Plato” closely aligns with the stereotypical typologies about East and West that prevailed in the wider culture, pointing to the limits of Emerson’s intellectual vision when trying to imagine the Eastern Other.

In 1856 Emerson composed a lyric poem originally called “Song of the Soul” and later published in the Atlantic in 1857 under the title “ Brahma .” The poem dramatizes an idea that Emerson closely associated with Hinduism; namely, that the material world is essentially an illusory mask of the divine spirit that dwells in all beings. Although it stands to reason that the poem is written from the perspective of Brahma, the Hindu god of creation, or even Brahman, the absolute or universal soul, the speaker in the poem does not name itself. Instead, the speaker enumerates the ways in which it eludes characterization. The opening lines of the four-stanza verse exemplify the riddle-like quality of the poem as a whole: “If the red slayer think he slays, / Or if the slain think he is slain,/ They know not well the subtle ways / I keep, and pass, and turn again.”

In many ways, “Brahma” is a distillation of Emerson’s reading of Hindu sacred literatures over the previous two decades, from the Baghavad Gita to the Katha Upanishad . When “Brahma” inspired dozens of mocking parodies in the Atlantic —its paradoxical style proved to be too much for many antebellum American readers, who objected to its exotic obscurities—Emerson told his daughter that one did not need to adopt a Hindu perspective to understand the poem. One could easily substitute “Jehovah” for “Brahma,” he explained, and not lose the sense of the verse.

In 1858 Emerson published a long essay, “Persian Poetry,” in the Atlantic . As a way of introducing American readers to what was likely an unfamiliar poetic tradition, Emerson drew parallels between Persian poetry and Homeric epics, English ballads, and the works of William Shakespeare. He also noted that the legends of Persian mythology could sometimes be found in the Hebrew Bible. As part of his exposition, Emerson included his own English translations of the poets Hafez, Saadi, Khayyam , and Enweri, by way of the German translations of Persian poetry by Baron von Hammer-Purgstall. Emerson had no competence in any Asian or Middle Eastern language, and he never read a non-Western text in its original language. But Emerson had been translating von Hammer’s German texts in his journals since 1846. By the end of his life, Emerson produced at least 64 translations, totaling more than 700 lines of Persian verse, many of which can be found in “Orientalist,” a notebook he began to keep in the 1850s.

In 1872 Emerson sailed for England and then Egypt with his daughter, Ellen. As he toured the cities of Alexandria and Cairo, Emerson noted observations about the Pyramids, the Nile River, and his woeful ignorance of the Arabic language. But at 70 years old, Emerson’s most significant writings about the East were behind him. Ten years later, on April 27, 1882, Emerson died in Concord, leaving an enduring legacy as the seminal figure of modern American Orientalism. His lifelong excursions into the libraries of classical Asian and Middle Eastern literatures were those of an enthusiast instead of a rigorous scholar, and he often relied on crude Romantic stereotypes and failed to recognize the differences among the cultures and peoples of the East. But Ralph Waldo Emerson expanded the Eastern horizons of generations of American readers and writers, and he persuasively demonstrated how classical Indian, Chinese, and Persian works could be used as a means to bring the inquiring self into a fresh appreciation of its own profound powers.

Concord Hymn

- See All Poems by Ralph Waldo Emerson

A Voice From the Tomb

Waiting for form.

- See All Related Content

- U.S., New England

- Poems by This Poet

- Prose by This Poet

- Bibliography

Each and All

Give all to love, ode, inscribed to william h. channing, ode to beauty, parks and ponds, the snow-storm, from “the poet”.

Poems and prose about conflict, armed conflict, and poetry's role in shaping perceptions and outcomes of war.

Jones Very's divine possession briefly captivated the Transcendentalists, but his idealism proved a trap.

How Robert Frost made poetry modern.

Further Readings

Bibliographies:

- Joel Myerson, Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Descriptive Bibliography (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1982).

- Robert E. Burkholder and Myerson, "Ralph Waldo Emerson," in The Transcendentalists: A Review of Research and Criticism , edited by Myerson (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1984), pp. 135-166.

- Burkholder and Myerson, Emerson: An Annotated Secondary Bibliography (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985).

- Burkholder and Myerson, Ralph Waldo Emerson: An Annotated Bibliography of Criticism, 1980-1991 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994).

Biographies:

- Moncure Daniel Conway, Emerson at Home and Abroad (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1882).

- Oliver Wendell Holmes, Ralph Waldo Emerson (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1884).

- David Greene Haskins, Ralph Waldo Emerson: His Maternal Ancestors (Boston: Cupples, Upham, 1886).

- James Elliot Cabot, A Memoir of Ralph Waldo Emerson , 2 volumes (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1887).

- Edward Waldo Emerson, Emerson in Concord (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1889).

- O. W. Firkins, Ralph Waldo Emerson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1915).

- Denton J. Snider, A Biography of Ralph Waldo Emerson (St. Louis: William Harvey Miner, 1921).

- Ralph L. Rusk, The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson (New York: Scribners, 1949).

- Henry F. Pommer, Emerson's First Marriage (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1967).

- Gay Wilson Allen, Waldo Emerson: A Biography (New York: Viking, 1981).

- John McAleer, Ralph Waldo Emerson: Days of Encounter (Boston: Little, Brown, 1984).

- Evelyn Barish, Emerson: The Roots of Prophecy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989).

- Albert J. von Frank, An Emerson Chronology (New York: G. K. Hall, 1994).

- Robert D. Richardson Jr., Emerson: The Mind on Fire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

References:

- Sacvan Bercovitch, The Rites of Assent (New York: Routledge, 1993).

- Edmund G. Berry, Emerson's Plutarch (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961).

- Jonathan Bishop, Emerson on the Soul (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1964).

- Lawrence Buell, Literary Transcendentalism (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1973).

- Stanley Cavell, Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

- Mary Kupiec Cayton, Emerson's Emergence: Self and Society in the Transformation of New England, 1800-1845 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989).

- John Jay Chapman, Emerson and Other Essays (New York: Scribners, 1898).

- Julie Ellison, Emerson's Romantic Style (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).

- Charles Feidelson Jr., Symbolism and American Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961).

- Maurice Gonnaud, Individu et societe dans l'oeuvre de Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essai de biographie spirituelle (Paris, 1964); translated by Lawrence Rosenwald as An Uneasy Solitude: Individual and Society in the Work of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987).

- Len Gougeon, Virtue's Hero: Emerson, Antislavery, and Reform (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990).

- Kenneth Marc Harris, Carlyle and Emerson: Their Long Debate (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978).

- Alan D. Hodder, Emerson's Rhetoric of Revelation: Nature, the Reader, and the Apocalypse Within (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989).

- Vivian C. Hopkins, Spires of Form: A Study of Emerson's Aesthetic Theory (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1951).

- Michael Lopez, Emerson and Power: Creative Antagonism in the Nineteenth Century (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1996).

- Lopez, ed., Emerson/Nietzsche, ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance , 43 (1998).

- F. O. Matthiessen, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1941).

- John Michael, Emerson and Skepticism: The Cipher of the World (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988).

- Wesley T. Mott, "The Strains of Eloquence": Emerson and His Sermons (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1989).

- Mott and Robert E. Burkholder, eds., Emersonian Circles: Essays in Honor of Joel Myerson (Rochester, N.Y.: University of Rochester Press, 1997).

- Joel Myerson, ed., A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Philip L. Nicoloff, Emerson on Race and History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961).

- Richard R. O'Keefe, Mythic Archetypes in Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Blakean Reading (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1995).

- B. L. Packer, Emerson's Fall: A New Interpretation of the Major Essays (New York: Continuum, 1982).

- Sherman Paul, Emerson's Angle of Vision: Man and Nature in the American Experience (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1952).

- Joel Porte, Emerson and Thoreau: Transcendentalists in Conflict (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1966).

- Porte, Representative Man: Ralph Waldo Emerson in His Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979; revised, 1988).

- Porte and Saundra Morris, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- David Porter, Emerson and Literary Change (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978).

- Susan L. Roberson, Emerson in His Sermons: A Man-Made Self (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1995).

- David M. Robinson, Apostle of Culture: Emerson as Preacher Lecturer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982).

- Robinson, Emerson and The Conduct of Life (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Lawrence Rosenwald, Emerson and the Art of the Diary (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

- F. B. Sanborn, ed., The Genius and Character of Emerson (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1885).

- Merton M. Sealts, Jr., Emerson on the Scholar (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1992).

- Sealts, and Alfred R. Ferguson, eds., Emerson's Nature--Origin, Growth, Meaning (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969; revised, 1979).

- Richard F. Teichgraeber, Sublime Thoughts/Penny Wisdom: Situating Emerson and Thoreau in the American Market (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

- Gustaaf Van Cromphout, Emerson's Ethics (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999).

- Van Cromphout, Emerson's Modernity and the Example of Goethe (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1990).

- Albert J. von Frank, The Trials of Anthony Burns: Freedom and Slavery in Emerson's Boston (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- Hyatt Waggoner, Emerson as Poet (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974).

- Stephen E. Whicher, Freedom and Fate: An Inner Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1953).

- R. A. Yoder, Emerson and the Orphic Poet in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978).

- Charles L. Young, Emerson's Montaigne (New York: Macmillan, 1941).

- Christina Zwarg, Feminist Conversations: Fuller, Emerson, and the Play of Reading (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1995).

- Audio Poems

- Audio Poem of the Day

- Twitter Find us on Twitter

- Facebook Find us on Facebook

- Instagram Find us on Instagram

- Facebook Find us on Facebook Poetry Foundation Children

- Twitter Find us on Twitter Poetry Magazine

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Poetry Mobile App

- 61 West Superior Street, Chicago, IL 60654

- © 2024 Poetry Foundation

The American Scholar: Emerson’s Superb Speech on the Life of the Mind, the Art of Creative Reading, and the Building Blocks of Genius

By maria popova.

Titled “The American Scholar,” the speech was eventually included in the indispensable volume Essays and Lectures ( public library | free download ) — the source of Emerson’s enduring wisdom on the two pillars of friendship , the key to personal growth , what beauty really means , and how to live with maximum aliveness . Nearly two centuries later, his oratory masterwork speaks to some of the most pressing issues of our time and his piercing insight into the cultural responsibility and creative challenges of the scholar applies equally to the writer, the artist, and the journalist of today.

Long before our era’s foundational theories of how creativity works , Emerson argues that the fertile mind is one which connects the seemingly disconnected :

To the young mind, every thing is individual, stands by itself. By and by, it finds how to join two things, and see in them one nature; then three, then three thousand; and so, tyrannized over by its own unifying instinct, it goes on tying things together, diminishing anomalies, discovering roots running under ground, whereby contrary and remote things cohere, and flower out from one stem.

Echoing Goethe’s insistence upon the importance of building one’s mental library of influences , Emerson considers the singular value of books to the developing mind:

[A] great influence into the spirit of the scholar, is, the mind of the Past, — in whatever form, whether of literature, of art, of institutions, that mind is inscribed. Books are the best type of the influence of the past… The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again… It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.

But books — like any technology of thought, indeed — aren’t inherently valuable; we confer value upon them by the nature of our use. To deny ourselves the wealth of human genius contained in books, Emerson argues, is to rob ourselves of vital inspiration; but to rely on books as blind dogma is to blunt our own creative genius:

Books are the best of things, well used; abused, among the worst. What is the right use? What is the one end, which all means go to effect? They are for nothing but to inspire. I had better never see a book, than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul. This every man is entitled to; this every man contains within him, although, in almost all men, obstructed, and as yet unborn. The soul active sees absolute truth; and utters truth, or creates. In this action, it is genius; not the privilege of here and there a favorite, but the sound estate of every man. In its essence, it is progressive. The book, the college, the school of art, the institution of any kind, stop with some past utterance of genius. This is good, say they, — let us hold by this. They pin me down. They look backward and not forward. But genius looks forward: the eyes of man are set in his forehead, not in his hindhead: man hopes: genius creates. […] Instead of being its own seer, let it receive from another mind its truth, though it were in torrents of light, without periods of solitude, inquest, and self-recovery, and a fatal disservice is done. Genius is always sufficiently the enemy of genius by over influence.

Genius, says Emerson, is best nurtured by a balance of reading books and “reading” life — in fact, even more important than being a scholar by the lamplight of the study is being a scholar in the luminous school of life:

Undoubtedly there is a right way of reading, so it be sternly subordinated. Man Thinking must not be subdued by his instruments. Books are for the scholar’s idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men’s transcripts of their readings. But when the intervals of darkness come, as come they must, — when the sun is hid, and the stars withdraw their shining, — we repair to the lamps which were kindled by their ray, to guide our steps to the East again, where the dawn is. We hear, that we may speak.

And yet the pleasure of reading, Emerson reminds us in a remark that applies perfectly to this very speech, is unparalleled in granting us a sense of communion with kindred spirits and likeminds long gone:

It is remarkable, the character of the pleasure we derive from the best books… There is some awe mixed with the joy of our surprise, when this poet, who lived in some past world, two or three hundred years ago, says that which lies close to my own soul, that which I also had wellnigh thought and said.

But since the fruits of reading are ones we must actively reap, Emerson makes a beautiful case for the art of creative reading:

I would not be hurried … to underrate the Book. … As the human body can be nourished on any food, though it were boiled grass and the broth of shoes, so the human mind can be fed by any knowledge… I only would say, that it needs a strong head to bear that diet. One must be an inventor to read well. As the proverb says, “He that would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry out the wealth of the Indies.” There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant, and the sense of our author is as broad as the world.

In a sentiment that calls to mind Tom Wolfe’s magnificent commencement address on the rise of the pseudo-intellectual , Emerson admonishes against mistaking the academic charades of knowledge for knowledge itself:

Colleges … can only highly serve us, when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and, by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns, and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit.

And yet the true scholar, Emerson argues, is the person able to bridge ideas with actions:

Action is with the scholar subordinate, but it is essential. Without it, he is not yet man. Without it, thought can never ripen into truth. Whilst the world hangs before the eye as a cloud of beauty, we cannot even see its beauty. Inaction is cowardice, but there can be no scholar without the heroic mind. The preamble of thought, the transition through which it passes from the unconscious to the conscious, is action… Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not. […] I do not see how any man can afford, for the sake of his nerves and his nap, to spare any action in which he can partake. It is pearls and rubies to his discourse. Drudgery, calamity, exasperation, want, are instructers in eloquence and wisdom. The true scholar grudges every opportunity of action past by, as a loss of power. It is the raw material out of which the intellect moulds her splendid products. […] He who has put forth his total strength in fit actions, has the richest return of wisdom.

In a sentiment that resonates with poet Sylvia Plath’s formative experience as a farm worker and philosopher Simone Weil’s decision to labor incognito at a car factory before entrusting her writings to a farmer , Emerson argues for “the dignity and necessity of labor to every citizen” and insists that the true scholar must acquire learning not only by reading but by living fully:

If it were only for a vocabulary, the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary. Years are well spent in country labors; in town, — in the insight into trades and manufactures; in frank intercourse with many men and women; in science; in art; to the one end of mastering in all their facts a language by which to illustrate and embody our perceptions. I learn immediately from any speaker how much he has already lived, through the poverty or the splendor of his speech. Life lies behind us as the quarry from whence we get tiles and copestones for the masonry of to-day. […] Character is higher than intellect. Thinking is the function. Living is the functionary. The stream retreats to its source. A great soul will be strong to live, as well as strong to think. Does he lack organ or medium to impart his truths? He can still fall back on this elemental force of living them. This is a total act. Thinking is a partial act… The scholar loses no hour which the man lives.

With this, he turns to the role of the scholar in society — a role he sees much as William Faulkner saw the role of the writer and Joseph Conrad saw that of the artist . Emerson writes:

The office of the scholar is to cheer, to raise, and to guide men by showing them facts amidst appearances.

But doing that, he points out, is an act of creative rebellion — one not for the faint of heart or timid of conviction, for those who insist on maintaining appearances will always push back against the tellers of truth. Asserting that the scholar must “defer never to the popular cry” — a piercing and timely incantation in our era of catering to the lowest common denominator of culture, where entire industries are built upon indulging the popular cry — Emerson urges:

In the long period of his preparation, [the true scholar] must betray often an ignorance and shiftlessness in popular arts, incurring the disdain of the able who shoulder him aside. Long he must stammer in his speech; often forego the living for the dead. Worse yet, he must accept, — how often! poverty and solitude. For the ease and pleasure of treading the old road, accepting the fashions, the education, the religion of society, he takes the cross of making his own, and, of course, the self-accusation, the faint heart, the frequent uncertainty and loss of time, which are the nettles and tangling vines in the way of the self-relying and self-directed; and the state of virtual hostility in which he seems to stand to society… For all this loss and scorn, what offset? He is to find consolation in exercising the highest functions of human nature. He is one, who raises himself from private considerations, and breathes and lives on public and illustrious thoughts. He is the world’s eye. He is the world’s heart. He is to resist the vulgar prosperity that retrogrades ever to barbarism, by preserving and communicating heroic sentiments, noble biographies, melodious verse, and the conclusions of history. Whatsoever oracles the human heart, in all emergencies, in all solemn hours, has uttered as its commentary on the world of actions, — these he shall receive and impart.

In a remark particularly assuring amid the outrage culture of our time, Emerson admonishes against getting caught up in the fads of controversy:

The world of any moment is the merest appearance. Some great decorum, some fetish of a government, some ephemeral trade, or war, or man, is cried up by half mankind and cried down by the other half, as if all depended on this particular up or down. The odds are that the whole question is not worth the poorest thought which the scholar has lost in listening to the controversy. Let him not quit his belief that a popgun is a popgun, though the ancient and honorable of the earth affirm it to be the crack of doom. In silence, in steadiness, in severe abstraction, let him hold by himself; add observation to observation, patient of neglect, patient of reproach; and bide his own time, — happy enough, if he can satisfy himself alone, that this day he has seen something truly. […] Free should the scholar be, — free and brave… Brave; for fear is a thing, which a scholar by his very function puts behind him. Fear always springs from ignorance… The world is his, who can see through its pretension.

“The American Scholar” is a timeless and enormously nourishing read in its entirety, and a spiritually rejuvenating reread, as is just about everything in Emerson’s Essays and Lectures . Complement it with Parker Palmer, a modern-day Emerson, on the six pillars of the wholehearted life and Susan Sontag on storytelling and how to be a moral human being .

— Published August 31, 2015 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/08/31/emerson-the-american-scholar/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, culture education philosophy ralph waldo emerson, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Ralph Waldo Emerson The Best 5 Books to Read

R alph Waldo Emerson (1803 - 1882) was a philosopher and essayist perhaps best known for spearheading American Transcendentalism, a philosophical movement that emphasizes the power of individualism, self-reliance, and the natural world.

One of the key hallmarks of the Transcendentalist movement, which notably included Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau (see our reading list of Thoreau’s best books here ), is its celebration of the supremacy — even divinity — of nature.

Divinity is not locked in a distant heaven, say transcendentalists; it is accessible right here in the company of the natural world.

We are thus at our best not when we conform to voices outside ourselves, but when we follow the voice within — the glimmering insight, the “immense intelligence” of our natural intuition and instincts.

Society on this view is seen as a corrupting force — it takes us away from our natural wisdom.

As unique individuals, we should not conform to generic belief systems or conventions, Emerson writes, but instead “enjoy an original relation to the universe.”

Emerson offers the beginnings of a path for how we might resist the pressures of society in his famous 1841 essay, Self-Reliance (read my Self-Reliance summary and analysis here ), which features in the collection below.

A famous passage from Emerson’s Self-Reliance that encapsulates the theme of much of his work runs as follows:

You will always find those who think they know what is your duty better than you know it. It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

This reading list consists of the best books by and about Ralph Waldo Emerson.

After reading some of the books on this list, you’ll understand why this brilliant thinker was heralded by the great German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche as “the most gifted of the Americans” (see my reading list of Nietzsche’s best books here ), and remains so celebrated to this day.

Let’s dive in!

1. Nature and Selected Essays, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

BY RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Nature was Emerson’s first book, and it set out the core principles for much of his (and Transcendentalist) thought.

Published in 1836 following the traumatic death of his first wife, Nature features Emerson at his sermonic best. Having left the Church, Emerson aimed to deliver secular lectures that nevertheless contained an almost religious power of their own. Nature is his first attempt at doing so with the written word — and in this regard it’s an undisputed success.

Emerson meditates on the power and beauty of nature and our profound, unbreakable connection to it. He writes:

Nature always wears the colors of the spirit. To a man laboring under calamity, the heat of his own fire hath sadness in it.

The essence of nature is integral to the essence of ourselves, and Emerson implores us to both explore and live in harmony with it.

If you’re interested in Emerson and Transcendentalism, there’s no better book to start with. As well as the book-length Nature essay, Nature and Selected Essays also includes many other of Emerson’s most acclaimed essays, including Self-Reliance, The Poet, and The American Scholar.

2. The Annotated Emerson, by Ralph Waldo Emerson and David Mikics

The Annotated Emerson

While Emerson is regarded as one of America’s greatest writers, his luxurious 19th-century prose can appear a little dense to the modern eye. Hence The Annotated Emerson : a brilliant book — published in 2012 — that contextualizes, illustrates, and discusses Emerson’s most important works.

Presenting some of Emerson’s most significant essays (including Nature, Self-Reliance, and more), the scholar David Mikics provides brilliant commentary throughout, drawing on Emerson’s journal entries and providing biographical details to supplement the work and bring Emerson’s writing to life.

For those seeking a deeper understanding of Emerson’s work, The Annotated Emerson is highly recommended.

3. Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays and Lectures, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays and Lectures

If you’re looking for a one-stop shop for all things Emerson, then look no further than Ralph Waldo Emerson: Essays and Lectures , published in 1983.

This anthology contains all of Emerson’s essays and lectures, as well as a wealth of helpful contextual and biographical detail.

At 1150 pages, this anthology’s a beast — but you won’t need another!

4. Emerson: The Mind on Fire, by Robert D. Richardson

Emerson: The Mind on Fire

BY ROBERT D. RICHARDSON

If you’re looking to learn more about the life Emerson lived and the events that shaped his work, Robert D. Richardson’s Emerson: The Mind on Fire is a fantastic biography, excellently researched and engagingly written.

In 100 bite-size chapters, Richardson lovingly weaves the story of Emerson’s intellectual development, his spearheading of the Transcendentalist movement (and often fraught interpersonal relationships with its members), his legacy as one of the greatest figureheads of American literature, and his lasting impact on the American psyche.

If you’re interested in Emerson, this autobiography is an essential addition to your bookshelf.

5. Emerson in His Journals, by Joel Porte

Emerson in His Journals

BY JOEL PORTE

For much of his long and fascinating life, Emerson kept a detailed journal. In 1984, Emerson scholar Joel Porte edited Emerson’s vast collection of journal entries to produce Emerson in His Journals , a book that should delight fans of Emerson and his work.

In these pages, we are granted intimate access into some of the major events in Emerson’s life — like his complex relationship with fellow Transcendentalist Margaret Fuller — from Emerson’s own perspective .

We see a side to Emerson that he would never expose in his published writings, rendering Emerson in His Journals an enthralling addition for hardcore Emerson scholars.

Further reading

Are there any other books you think should be on this list? Let us know via email or drop us a message on Twitter or Instagram .

In the meantime, why not explore more of our reading lists on the best philosophy books :

View All Reading Lists

Essential Philosophy Books by Subject

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free):

About the author.

Jack Maden Founder Philosophy Break

Having received great value from studying philosophy for 15+ years (picking up a master’s degree along the way), I founded Philosophy Break in 2018 as an online social enterprise dedicated to making the subject’s wisdom accessible to all. Learn more about me and the project here.

If you enjoy learning about humanity’s greatest thinkers, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one mind-opening idea from philosophy, and invite you to share your view.

Subscribe for free here , and join 13,000+ philosophers enjoying a nugget of profundity each week (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time).

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 13,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Each philosophy break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your curiosity.

Aristotle vs the Stoics: What Does Happiness Require?

5 -MIN BREAK

5 Existential Problems All Humans Share

4 -MIN BREAK

The Buddha’s Four Noble Truths: the Cure for Suffering

7 -MIN BREAK

Compatibilism: Philosophy’s Favorite Answer to the Free Will Debate

10 -MIN BREAK

View All Breaks

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

| (From Amos Bronson Alcott, , Boston: A. Williams and Co., 1882) |

Ralph Waldo Emerson

An American essayist, poet, and popular philosopher, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–82) began his career as a Unitarian minister in Boston, but achieved worldwide fame as a lecturer and the author of such essays as “Self-Reliance,” “History,” “The Over-Soul,” and “Fate.” Drawing on English and German Romanticism, Neoplatonism, Kantianism, and Hinduism, Emerson developed a metaphysics of process, an epistemology of moods, and an “existentialist” ethics of self-improvement. He influenced generations of Americans, from his friend Henry David Thoreau to John Dewey, and in Europe, Friedrich Nietzsche, who takes up such Emersonian themes as power, fate, the uses of poetry and history, and the critique of Christianity.

1. Chronology of Emerson's Life

2.1 education, 2.2 process, 2.3 morality, 2.4 christianity, 2.6 unity and moods, 3.1 consistency, 3.2 early and late emerson, 3.3 sources and influence, works by emerson, selected writings on emerson, other internet resources, related entries.

| 1803 | Born in Boston to William and Ruth Haskins Emerson. |

| 1811 | Father dies, probably of tuberculosis. |

| 1812 | Enters Boston Public Latin School |

| 1817 | Begins study at Harvard College: Greek, Latin, History, Rhetoric. |

| 1820 | Starts first journal, entitled “The Wide World.” |

| 1821 | Graduates from Harvard and begins teaching at his brother William's school for young ladies in Boston. |

| 1825 | Enters Harvard Divinity School. |

| 1829 | Marries Ellen Tucker and is ordained minister at Boston's Second Church. |

| 1831 | Ellen Tucker Emerson dies, at age 19. |

| 1832 | Resigns position as minister and sails for Europe. |

| 1833 | Meets Wordsworth, Coleridge, J. S. Mill, and Thomas Carlyle. Returns to Boston in November, where he begins a career as a lecturer. |

| 1834 | Receives first half of a substantial inheritance from Ellen's estate (second half comes in 1837). |

| 1835 | Marries Lidian Jackson. |

| 1836 | Publishes first book, . |

| 1838 | Delivers the “Divinity School Address.” Protests relocation of the Cherokees in letter to President Van Buren. |

| 1841 | published (contains “Self-Reliance,” “The Over-Soul,” “Circles,” “History”). |

| 1842 | Son Waldo dies of scarlet fever at the age of 5. |

| 1844 | published (contains “The Poet,” “Experience,” “Nominalist and Realist”). |

| 1847–8 | Lectures in England. |

| 1850 | Publishes (essays on Plato, Swedenborg, Montaigne, Goethe, Napoleon). |

| 1851–60 | Speaks against Fugitive Slave Law and in support of anti-slavery candidates in Concord, Boston, New York, Philadelphia. |

| 1856 | Publishes . |

| 1860 | Publishes (contains “Culture” and “Fate”). |

| 1867 | Lectures in nine western states. |

| 1870 | Publishes Presents sixteen lectures in Harvard's Philosophy Department. |

| 1872–3 | After a period of failing health, travels to Europe, Egypt. |

| 1875 | Journal entries cease. |

| 1882 | Dies in Concord. |

2. Major Themes in Emerson's Philosophy

In “The American Scholar,” delivered as the Phi Beta Kappa Address in 1837, Emerson maintains that the scholar is educated by nature, books, and action. Nature is the first in time (since it is always there) and the first in importance of the three. Nature's variety conceals underlying laws that are at the same time laws of the human mind: “the ancient precept, ‘Know thyself,’ and the modern precept, ‘Study nature,’ become at last one maxim” (CW1: 55). Books, the second component of the scholar's education, offer us the influence of the past. Yet much of what passes for education is mere idolization of books — transferring the “sacredness which applies to the act of creation…to the record.” The proper relation to books is not that of the “bookworm” or “bibliomaniac,” but that of the “creative” reader (CW1: 58) who uses books as a stimulus to attain “his own sight of principles.” Used well, books “inspire…the active soul” (CW1: 56). Great books are mere records of such inspiration, and their value derives only, Emerson holds, from their role in inspiring or recording such states of the soul. The “end” Emerson finds in nature is not a vast collection of books, but, as he puts it in “The Poet,” “the production of new individuals,…or the passage of the soul into higher forms” (CW3:14)

The third component of the scholar's education is action. Without it, thought “can never ripen into truth” (CW1: 59). Action is the process whereby what is not fully formed passes into expressive consciousness. Life is the scholar's “dictionary” (CW1: 60), the source for what she has to say: “Only so much do I know as I have lived” (CW1:59). The true scholar speaks from experience, not in imitation of others; her words, as Emerson puts it, are “are loaded with life…” (CW1: 59). The scholar's education in original experience and self-expression is appropriate, according to Emerson, not only for a small class of people, but for everyone. Its goal is the creation of a democratic nation. Only when we learn to “walk on our own feet” and to “speak our own minds,” he holds, will a nation “for the first time exist” (CW1: 70).

Emerson returned to the topic of education late in his career in “Education,” an address he gave in various versions at graduation exercises in the 1860's. Self-reliance appears in the essay in his discussion of respect. The “secret of Education,” he states, “lies in respecting the pupil.” It is not for the teacher to choose what the pupil will know and do, but for the pupil to discover “his own secret.” The teacher must therefore “wait and see the new product of Nature” (E: 143), guiding and disciplining when appropriate-not with the aim of encouraging repetition or imitation, but with that of finding the new power that is each child's gift to the world. The aim of education is to “keep” the child's “nature and arm it with knowledge in the very direction in which it points” (E: 144). This aim is sacrificed in mass education, Emerson warns. Instead of educating “masses,” we must educate “reverently, one by one,” with the attitude that “the whole world is needed for the tuition of each pupil” (E: 154).

Emerson is in many ways a process philosopher, for whom the universe is fundamentally in flux and “permanence is but a word of degrees” (CW 2: 179). Even as he talks of “Being,” Emerson represents it not as a stable “wall” but as a series of “interminable oceans” (CW3: 42). This metaphysical position has epistemological correlates: that there is no final explanation of any fact, and that each law will be incorporated in “some more general law presently to disclose itself” (CW2: 181). Process is the basis for the succession of moods Emerson describes in “Experience,” (CW3: 30), and for the emphasis on the present throughout his philosophy.

Some of Emerson's most striking ideas about morality and truth follow from his process metaphysics: that no virtues are final or eternal, all being “initial,” (CW2: 187); that truth is a matter of glimpses, not steady views. We have a choice, Emerson writes in “Intellect,” “between truth and repose,” but we cannot have both (CW2: 202). Fresh truth, like the thoughts of genius, comes always as a surprise, as what Emerson calls “the newness” (CW3: 40). He therefore looks for a “certain brief experience, which surprise[s] me in the highway or in the market, in some place, at some time…” (CW1: 213). This is an experience that cannot be repeated by simply returning to a place or to an object such as a painting. A great disappointment of life, Emerson finds, is that one can only “see” certain pictures once, and that the stories and people who fill a day or an hour with pleasure and insight are not able to repeat the performance.

Emerson's basic view of religion also coheres with his emphasis on process, for he holds that one finds God only in the present: “God is, not was” (CW1:89). In contrast, what Emerson calls “historical Christianity” (CW1: 82) proceeds “as if God were dead” (CW1: 84). Even history, which seems obviously about the past, has its true use, Emerson holds, as the servant of the present: “The student is to read history actively and not passively; to esteem his own life the text, and books the commentary” (CW2: 5).

Emerson's views about morality are intertwined with his metaphysics of process, and with his perfectionism, his idea that life has the goal of passing into “higher forms” (CW3:14). The goal remains, but the forms of human life, including the virtues, are all “initial” (CW2: 187). The word “initial” suggests the verb “initiate,” and one interpretation of Emerson's claim that “all virtues are initial” is that virtues initiate historically developing forms of life, such as those of the Roman nobility or the Confucian junxi . Emerson does have a sense of morality as developing historically, but in the context in “Circles” where his statement appears he presses a more radical and skeptical position: that our virtues often must be abandoned rather than developed. “The terror of reform,” he writes, “is the discovery that we must cast away our virtues, or what we have always esteemed such, into the same pit that has consumed our grosser vices” (CW2: 187). The qualifying phrase “or what we have always esteemed such” means that Emerson does not embrace an easy relativism, according to which what is taken to be a virtue at any time must actually be a virtue. Yet he does cast a pall of suspicion over all established modes of thinking and acting. The proper standpoint from which to survey the virtues is the ‘new moment‘ — what he elsewhere calls truth rather than repose (CW2:202) — in which what once seemed important may appear “trivial” or “vain” (CW2:189). From this perspective (or more properly the developing set of such perspectives) the virtues do not disappear, but they may be fundamentally altered and rearranged.

Although Emerson is thus in no position to set forth a system of morality, he nevertheless delineates throughout his work a set of virtues and heroes, and a corresponding set of vices and villains. In “Circles” the vices are “forms of old age,” and the hero the “receptive, aspiring” youth (CW2:189). In the “Divinity School Address,” the villain is the “spectral” preacher whose sermons offer no hint that he has ever lived. “Self Reliance” condemns virtues that are really “penances” (CW2: 31), and the philanthropy of abolitionists who display an idealized “love” for those far away, but are full of hatred for those close by (CW2: 30).

Conformity is the chief Emersonian vice, the opposite or “aversion” of the virtue of “self-reliance.” We conform when we pay unearned respect to clothing and other symbols of status, when we show “the foolish face of praise” or the “forced smile which we put on in company where we do not feel at ease in answer to conversation which does not interest us” (CW2: 32). Emerson criticizes our conformity even to our own past actions-when they no longer fit the needs or aspirations of the present. This is the context in which he states that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen, philosophers and divines” (CW2: 33). There is wise and there is foolish consistency, and it is foolish to be consistent if that interferes with the “main enterprise of the world for splendor, for extent,…the upbuilding of a man” (CW1: 65).

If Emerson criticizes much of human life, he nevertheless devotes most of his attention to the virtues. Chief among these is what he calls “self-reliance.” The phrase connotes originality and spontaneity, and is memorably represented in the image of a group of nonchalant boys, “sure of a dinner…who would disdain as much as a lord to do or say aught to conciliate one…” The boys sit in judgment on the world and the people in it, offering a free, “irresponsible” condemnation of those they see as “silly” or “troublesome,” and praise for those they find “interesting” or “eloquent.” (CW2: 29). The figure of the boys illustrates Emerson's characteristic combination of the romantic (in the glorification of children) and the classical (in the idea of a hierarchy in which the boys occupy the place of lords or nobles).

Although he develops a series of analyses and images of self-reliance, Emerson nevertheless destabilizes his own use of the concept. “To talk of reliance,” he writes, “is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is” (CW 2:40). ‘Self-reliance’ can be taken to mean that there is a self already formed on which we may rely. The “self” on which we are to “rely” is, in contrast, the original self that we are in the process of creating. Such a self, to use a phrase from Nietzsche's Ecce Homo, “becomes what it is.”

For Emerson, the best human relationships require the confident and independent nature of the self-reliant. Emerson's ideal society is a confrontation of powerful, independent “gods, talking from peak to peak all round Olympus.” There will be a proper distance between these gods, who, Emerson advises, “should meet each morning, as from foreign countries, and spending the day together should depart, as into foreign countries” (CW 3:81). Even “lovers,” he advises, “should guard their strangeness” (CW3: 82). Emerson portrays himself as preserving such distance in the cool confession with which he closes “Nominalist and Realist,” the last of the Essays, Second Series :

I talked yesterday with a pair of philosophers: I endeavored to show my good men that I liked everything by turns and nothing long…. Could they but once understand, that I loved to know that they existed, and heartily wished them Godspeed, yet, out of my poverty of life and thought, had no word or welcome for them when they came to see me, and could well consent to their living in Oregon, for any claim I felt on them, it would be a great satisfaction (CW 3:145).

The self-reliant person will “publish” her results, but she must first learn to detect that spark of originality or genius that is her particular gift to the world. It is not a gift that is available on demand, however, and a major task of life is to meld genius with its expression. “The man,” Emerson states “is only half himself, the other half is his expression” (CW 3:4). There are young people of genius, Emerson laments in “Experience,” who promise “a new world” but never deliver: they fail to find the focus for their genius “within the actual horizon of human life” (CW 3:31). Although Emerson emphasizes our independence and even distance from one another, then, the payoff for self-reliance is public and social. The scholar finds that the most private and secret of his thoughts turn out to be “the most acceptable, most public, and universally true” (CW1: 63). And the great “representative men” Emerson identifies are marked by their influence on the world. Their names-Plato, Moses, Jesus, Luther, Copernicus, even Napoleon-are “ploughed into the history of this world” (CW1: 80).

Although self-reliance is central, it is not the only Emersonian virtue. Emerson also praises a kind of trust, and the practice of a “wise skepticism.” There are times, he holds, when we must let go and trust to the nature of the universe: “As the traveler who has lost his way, throws his reins on his horse's neck, and trusts to the instinct of the animal to find his road, so must we do with the divine animal who carries us through this world” (CW3:16). But the world of flux and conflicting evidence also requires a kind of epistemological and practical flexibility that Emerson calls “wise skepticism” (CW4: 89). His representative skeptic of this sort is Michel de Montaigne, who as portrayed in Representative Men is no unbeliever, but a man with a strong sense of self, rooted in the earth and common life, whose quest is for knowledge. He wants “a near view of the best game and the chief players; what is best in the planet; art and nature, places and events; but mainly men” (CW4: 91). Yet he knows that life is perilous and uncertain, “a storm of many elements,” the navigation through which requires a flexible ship, “fit to the form of man.” (CW4: 91).