Why Is It Important to Study History?

Even if you live to be 100, you’ll never run out of new things to learn. From computer science and cryptocurrency to French literature and Spanish grammar, the world is full of knowledge and it’s all at your fingertips. So, why choose history?

Many people study history in high school and come away thinking it’s boring, irrelevant, or both. But as we get older, even just by a few years, we start to see the importance of understanding the past.

Why do we study history?

We study history because history doesn’t stay behind us. Studying history helps us understand how events in the past made things the way they are today. With lessons from the past, we not only learn about ourselves and how we came to be, but also develop the ability to avoid mistakes and create better paths for our societies.

How does history impact our lives today?

Events in the past have displaced families and groups, changing the makeup of regions and often causing tensions. Such events have also created government systems that have lasted generations beyond when they started. And all of it affects each person alive today.

Take the Great Depression, for example—one of the most difficult but impactful periods in American history. The economic crisis put almost 15 million people out of work and sent countless families into homelessness, stealing their sense of security. Many of those people would feel insecure for the rest of their lives.

The government had to learn how to help . This effort gave rise to Social Security, federal emergency relief programs, and funding for unemployment efforts. These changes continue to make life more secure for millions of Americans.

Society today comes from hundreds and thousands of actions like these. The more you learn about how these things happened, the better you understand real life.

What lessons can we learn from history?

History teaches us about things such as:

- Why some societies thrive while others fail.

- Why humans have gone to war.

- How people have changed society for the better.

History isn’t a study of others. The people you learn about may have lived decades or even centuries ago, but their actions directly affect how we live our lives today. Events that seem like dates on a page have been turning points in the story of our societies.

“Historical knowledge is no more and no less than carefully and critically constructed collective memory.” -William H. MacNeill, former president of the American Historical Association

Historical research builds and codifies these stories. When we study history, we learn how we got where we are, and why we live the way we do. It’s the study of us—of humans and our place in an ever changing world. Without it, we wouldn’t understand all of our triumphs and failures, and we would continually repeat patterns without building forward to something better.

As Spanish philosopher George Santayana once said, “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it. ”

How do past events help us understand the present?

The past creates the present. Our modern world exists because of events that happened long before our time. Only by understanding those events can we know how we got here, and where to go next.

1. History helps us understand change

History is full of transitions that have altered the world’s story. When you build your knowledge of history, you understand more about what created our present-day society.

Studying the American civil rights movement shows you how people organize successfully against oppressive systems. Learning about the fall of Rome teaches you that even the most powerful society can fall apart—and what happens to cause that crumbling.

By learning about different eras and their respective events, you start to see what changes might happen in the future and what would drive that change.

2. We learn from past mistakes

History gives us a better understanding of the world and how it operates. When you study a war, you learn more about how conflict escalates. You learn what dilemmas world leaders face and how they respond—and when those decisions lead to better or worse outcomes.

Historical study shows you the warning signs of many kinds of disaster, from genocide to climate inaction. Understanding these patterns will make you a more informed citizen and help you take action effectively.

3. We gain context for the human experience

Before 2020, most Americans hadn’t lived through a global pandemic. The 1918-1919 flu pandemic had faded from the popular picture of history, overshadowed by World War I on its back end and the Roaring 20s that followed.

Yet within months of COVID-19 entering the public awareness, historians and informed private citizens were writing about the flu pandemic again. Stories of a deadly second wave were re-told to warn people against the dangers of travel, and pictures of ancestors in masks re-emerged.

Through study of the past, we understand our own lives better. We see patterns as they re-emerge and take solace in the fact that others have gone through similar struggles

How do we study history?

There are many ways of studying and teaching history. Many people remember high school classes full of memorization—names, dates, and places of major historical events.

Decades ago, that kind of rote learning was important, but things have changed. Today, 60% of the world’s population and 90% of the U.S. population use the internet and can find those facts on demand. Today, learning history is about making connections and understanding not just what happened, but why.

Critical thinking

If you’ve ever served on a jury or read about a court case, you know that reconstructing the facts of the past isn’t a simple process. You have to consider the facts at hand, look at how they’re connected, and draw reasonable conclusions.

Take the fall of Rome , for example. In the Roman Empire’s last years, the central government was unstable yet the empire continued to spend money on expansion. Outside groups like the Huns and Saxons capitalized on that instability and invaded. The empire had split into East and West, further breaking down a sense of unity, and Christianity was replacing the Roman polytheistic religion.

When you become a student of history, you learn how to process facts like these and consider how one event affected the other. An expanding empire is harder to control, and invasions further tax resources. But what caused that instability in the first place? And why did expansion remain so important?

Once you learn how to think this way and ask these kinds of questions, you start engaging more actively with the world around you.

Finding the “So what?”

The study of history is fascinating, but that’s not the only reason why we do it. Learning the facts and following the thread of a story is just the first step.

The most important question in history is “So what?”.

For instance:

- Why were the Chinese so successful in maintaining their empire in Asia? Why did that change after the Industrial Revolution?

- Why was the invasion of Normandy in 1944 a turning point? What would happen if Allied forces hadn’t landed on French beaches?

Studying this way helps you see the relevance and importance of history, while giving you a deeper and more lasting understanding of what happened.

Where can I study history online?

The quality of your history education matters. You can read about major historical events on hundreds of websites and through YouTube videos, but it’s hard to know if you’re getting the full story. Many secondary sources are hit-or-miss when it comes to quality history teaching.

It’s best to learn history from a reputable educational institution. edX has history courses from some of the world’s top universities including Harvard , Columbia , and Tel Aviv . Explore one-topic in depth or take an overview approach—it’s completely up to you. The whole world is at your fingertips.

Related Posts

Why is it important to study logistics, are free online courses worth it, why is it important to study supply chain.

edX is the education movement for restless learners. Together with our founding partners Harvard and MIT, we’ve brought together over 35 million learners, the majority of top-ranked universities in the world, and industry-leading companies onto one online learning platform that supports learners at every stage. And we’re not stopping there—as a global nonprofit, we’re relentlessly pursuing our vision of a world where every learner can access education to unlock their potential, without the barriers of cost or location.

© 2021 edX. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Terms of Service

- Skip to main content

Life & Letters Magazine

Four Reasons Everyone Should Study History

By Rachel White July 23, 2018 facebook twitter email

In the past, STEM and the arts and humanities have largely been taught as unconnected disciplines, but there is more overlap between fields than many realize.

Erika Bsumek, an associate professor of history in the College of Liberal Arts and a 2018 recipient of the Regent’s Outstanding Teaching Awards , wants to help students see how different disciplines are connected. In her class, Building America : Engineering Society and Culture, 1868-19 80, Bsumek teaches humanities and STEM majors how history, culture and politics have shaped technological advances and, in turn, how technology has restructured society in numerous ways in the process.

Bsumek, who also teaches Native American and Environmental history, strives to help all of her students see the world around them in new ways. She says learning history can be interesting and even fun. The more history they learn, the better prepared they will be to solve the biggest challenges society faces now and in the future. Here are four reasons why she says learning history can help them do that.

- It helps us understand how our time is different from or similar to other periods.

In today’s world, where people often cherry pick facts about the past to prove points, it helps to place current events in historical context. History is an evidenced-based discipline. So, knowing how and where to find the facts one needs to gain a fuller understanding of today’s contentious debates can help us understand not only what is being said, but it can also help us grasp what kinds of historical comparisons people are making and why they are making them.

For instance, understanding how Native Americans were treated by both white settlers and the federal government can help us better understand why indigenous communities often resist what many non-American Indians view as seemingly “goodwill gestures” or “economic opportunities” — such as the proposed construction of a pipeline on or in proximity to Native land or a proposal to break up reservations into private parcels . Both kinds of actions have deep histories. Understanding the complexities associated with the historical experiences of the people involved can help build a better society.

- History helps you see the world around you in a new way.

Everything has a history. Trees have a history, music has a history, bridges have a history, political fights have a history, mathematical equations have a history. In fact, #everythinghasahistory. Learning about those histories can help us gain a deeper understanding of the world around us and the historical forces that connect us and continue to influence how we interact with each other and the environment.

For instance, when we turn on the tap to brush our teeth or fill our pots to cook we expect clean drinking water to flow. But, how many people know where their water comes from, who tests it for purity, or how society evolved to safeguard such controls? To forget those lessons makes us more prone to overlook the way we, as a society, need to continue to support the policies that made clean water a possibility.

- History education teaches us life skills.

In history courses, we learn not just about other people and places but we learn from them. We read the documents or materials that were produced at the time or listen to the oral histories people tell in order to convey the meaning of the past to successive generations. In doing so, we learn that there is just not one past, but a pluralism of pasts. This kind of knowledge can help the city manager and the engineer plan a new highway, city or park. It can also help us navigate our daily lives and learn to ask questions when we encounter people or places we don’t initially understand.

- Studying history teaches students the skill sets that they will need in almost any major or job.

Studying history and other humanities can not only pique one’s imagination and engage students, history courses can also help students learn how to take in vast amounts of information, how to write and communicate those ideas effectively, and, most importantly, to accept the fact that many problems have no clear-cut answer. As a result, history classes help students to cultivate flexibility and a willingness to change their minds as they go about solving problems in whatever field they ultimately choose.

Performance in history courses can also be a good indicator of a student’s overall ability to succeed in college. A recent article by the American Historical Association reports that “two national studies that show that college students who do not succeed in even one of their foundational-level [history] courses are the least likely to complete a degree at any institution over the 11-year period covered by the studies.” Why? The skills one learns in a well-taught history course can help students develop a flexible skill set they can use in their other classes and throughout their lives.

Featured image: Erika Bsumek at the Mansfield Dam located in Austin, Texas. Photo by Kirk Weddle.

Why should you study history?

To study history is to study change: historians are experts in examining and interpreting human identities and transformations of societies and civilizations over time. They use a range of methods and analytical tools to answer questions about the past and to reconstruct the diversity of past human experience: how profoundly people have differed in their ideas, institutions, and cultural practices; how widely their experiences have varied by time and place, and the ways they have struggled while inhabiting a shared world. Historians use a wide range of sources to weave individual lives and collective actions into narratives that bring critical perspectives on both our past and our present. Studying history helps us understand and grapple with complex questions and dilemmas by examining how the past has shaped (and continues to shape) global, national, and local relationships between societies and people.

The Past Teaches Us About the Present

Because history gives us the tools to analyze and explain problems in the past, it positions us to see patterns that might otherwise be invisible in the present – thus providing a crucial perspective for understanding (and solving!) current and future problems. For example, a course on the history of public health might emphasize how environmental pollution disproportionately affects less affluent communities – a major factor in the Flint water crisis. Understanding immigration patterns may provide crucial background for addressing ongoing racial or cultural tensions. In many ways, history interprets the events and causes that contributed to our current world.

History Builds Empathy Through Studying the Lives and Struggles of Others

Studying the diversity of human experience helps us appreciate cultures, ideas, and traditions that are not our own – and to recognize them as meaningful products of specific times and places. History helps us realize how different our lived experience is from that of our ancestors, yet how similar we are in our goals and values.

History Can Be Intensely Personal

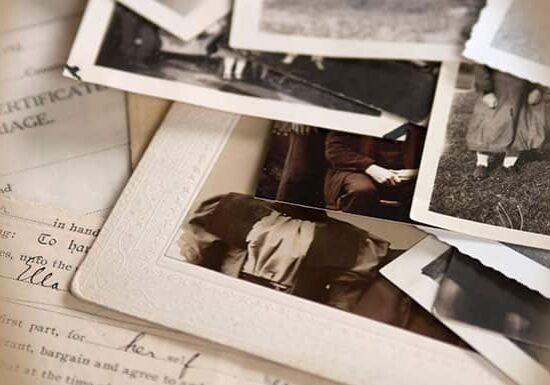

In learning about the past, we often discover how our own lives fit into the human experience. In October 2015, a UW alumnus named Michael Stern contacted Professor Amos Bitzan for help translating letters from his grandmother, Sara Spira, to his parents. Bitzan was able to integrate some of the letters into his class on the Holocaust to bring to life for his students the day-to-day realities of being Jewish in Nazi-occupied Poland. As Bitzan explained, “I realized that Sara Spira’s postcards could be a way for my students to integrate two facets of the study of the Holocaust: an analysis of victims and perpetrators.” And if you have ever seen an episode of “Who Do You Think You Are?”, you’ve seen the ways in which historical research can tell us amazing stories about our ancestors – stories we might not ever know otherwise.

“Doing” History is Like Completing a Puzzle or Solving a Mystery

Imagine asking a question about the past, assembling a set of clues through documents, artifacts, or other sources, and then piecing those clues together to tell a story that answers your question and tells you something unexpected about a different time and place. That’s doing history.

Everything Has a History

Everything we do, everything we use, everything else we study is the product of a complex set of causes, ideas, and practices. Even the material we learn in other courses has important historical elements – whether because our understanding of a topic changed over time or because the discipline takes a historical perspective. There is nothing that cannot become grist for the historian’s mill.

History Careers

- Overview More

- Why Study History? More

- What can I do with a degree in History? (pdf) More

Why Study History?

For a great many people, history is a set of facts, a collection of events, a series of things that happened, one after another, in the past. In fact, history is far more than these things-- it is a way of thinking about and seeing the world.

T o genuinely make sense of the past, you need to learn how to see it on its own terms, how to make the strange and unfamiliar logical and comprehensible, and how to empathize with people who once thought so differently than we do today. If you learn how to do these things, you begin to cultivate a crucial set of skills that not only help navigate the past, but the present as well. Once you can see the things that history teaches you, once you know how to penetrate unfamiliar modes of thought and behavior and can understand their inner logic, it becomes easier to make sense of the modern world and the diverse peoples and ideas that you will confront within it.

It might seem counterintuitive that one of the best ways to illuminate the present is by studying the past, but that is precisely why history can be so important. When we appreciate that history is not, first and foremost, a body of knowledge, but rather a way of thinking, it becomes a particularly powerful tool. Not everyone may choose to become a historian. Yet, whatever career you choose, knowing how to think historically will help.

By taking History courses at Stanford, you will develop

- critical, interpretive thinking skills through in-depth analysis of primary and secondary source materials.

the ability to identify different types of sources of historical knowledge.

analytical writing skills and close reading skills.

effective oral communication skills.

History coursework at Stanford is supported by mentorship from our world-class faculty and by unique research opportunities. These experiences enable undergraduate students to pursue successful careers in business, journalism, public service, law, education, government, medicine, and more. Learn what Stanford History majors and minors are doing after graduation .

Undergraduate Program

We offer the following degree options to Stanford undergraduate students:

Undergraduate Major : Become a historian and chart your path through the B.A. in consultation with your major advisor.

Honors in History : Join a passionate group of History majors who conduct in-depth research with Stanford faculty.

Undergraduate Minor : Complete six eligible courses for a minor in History.

Co-terminal Masters: Join the selective group of Stanford undergraduates who explore their passion in History before entering graduate school or professional life.

How to Declare

The first step in becoming a History major is finding a Faculty Advisor. The best way to find an advisor is simply to take a variety of History courses, drop in during faculty office hours, and introduce yourself as a prospective History major. Faculty are happy to suggest coursework and to offer counsel. You are also welcome to reach out to our undergraduate Peer Advisors about how to navigate Stanford History. Learn more about how to declare .

Herodotus: An Undergraduate Journal

Herodotus is a student-run publication founded in 1986 by the History Undergraduate Student Association (HUGSA). It bears the name of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, the 5th century BCE historian of the Greco-Persian Wars. Based on a rigorous, supportive peer-review process, the journal preserves and features the best undergraduate research conducted in the department. Browse Herodotus

Program Contacts

Thomas Mullaney

Director of Undergraduate Studies

Steven Press

Director of Honors and Research

Kai Dowding

Undergraduate Student Services Officer

Department Bookshelf

Browse the most recent publications from our faculty members.

Uncertain Past Time: Empire, Republic, and Politics | Belirsiz Geçmiş Zaman: İmparatorluk, Cumhuriyet Ve Siyaset

Embodied Knowledge: Women and Science before Silicon Valley

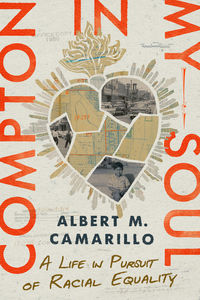

Compton in My Soul

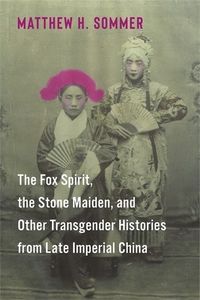

The Fox Spirit, the Stone Maiden, and Other Transgender Histories from Late Imperial China

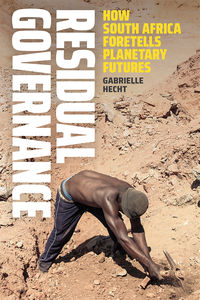

Residual Governance: How South Africa Foretells Planetary Futures

- Organisations & projects

- Bibliography

- Facts & figures

- Image gallery

- Lecture series

All people are living histories – which is why History matters

Penelope j. corfield.

Historians are often asked: what is the use or relevance of studying History (the capital letter signalling the academic field of study)? Why on earth does it matter what happened long ago? The answer is that History is inescapable. It studies the past and the legacies of the past in the present. Far from being a 'dead' subject, it connects things through time and encourages its students to take a long view of such connections.

All people and peoples are living histories. To take a few obvious examples: communities speak languages that are inherited from the past. They live in societies with complex cultures, traditions and religions that have not been created on the spur of the moment. People use technologies that they have not themselves invented. And each individual is born with a personal variant of an inherited genetic template, known as the genome, which has evolved during the entire life-span of the human species.

So understanding the linkages between past and present is absolutely basic for a good understanding of the condition of being human. That, in a nutshell, is why History matters. It is not just 'useful', it is essential.

The study of the past is essential for 'rooting' people in time. And why should that matter? The answer is that people who feel themselves to be rootless live rootless lives, often causing a lot of damage to themselves and others in the process. Indeed, at the most extreme end of the out-of-history spectrum, those individuals with the distressing experience of complete memory loss cannot manage on their own at all. In fact, all people have a full historical context. But some, generally for reasons that are no fault of their own, grow up with a weak or troubled sense of their own placing, whether within their families or within the wider world. They lack a sense of roots. For others, by contrast, the inherited legacy may even be too powerful and outright oppressive.

In all cases, understanding History is integral to a good understanding of the condition of being human. That allows people to build, and, as may well be necessary, also to change, upon a secure foundation. Neither of these options can be undertaken well without understanding the context and starting points. All living people live in the here-and-now but it took a long unfolding history to get everything to NOW. And that history is located in time-space, which holds this cosmos together, and which frames both the past and the present.

The discussion is amplified under the following headings:

Answering two objections to History

Noting two weak arguments in favour of studying history, celebrating the strong case for history, the repentance of henry ford: history is not bunk.

One common objection that historians encounter is the instant put-down that is derived from Henry Ford I, the impresario of the mass automobile. In 1916 he stated sweepingly: 'History is bunk'. Actually, Ford's original comment was not so well phrased and it was a journalist who boiled it down to three unforgettable words. Nonetheless, this is the phrasing that is attributed to Ford and it is this dictum that is often quoted by people wishing to express their scepticism about the subject.

Well, then, what is the use of History, if it is only bunk ? This rousingly old-fashioned term, for those who have not come across it before, is derived from the Dutch bunkum , meaning rubbish or nonsense.

Inwardly groaning, historians deploy various tactics in response. One obvious reaction is to challenge the terms of the question, in order to make questioners think again about the implications of their terminology. To demand an accountant-style audit of the instant usefulness of every subject smacks of a very crude model of education indeed. It implies that people learn only very specific things, for very specific purposes. For example, a would-be voyager to France, intending to work in that country, can readily identify the utility of learning the French language. However, since no-one can travel back in time to live in an earlier era, it might appear – following the logic of 'immediate application' – that studying anything other than the present-day would be 'useless'.

But not so. The 'immediate utility' formula is a deeply flawed proposition. Humans do not just learn gobbets of information for an immediate task at hand. And, much more fundamentally, the past and the present are not separated off into separate time-ghettos. Thus the would-be travellers who learn the French language are also learning French history, since the language was not invented today but has evolved for centuries into the present. And the same point applies all round. The would-be travellers who learn French have not appeared out of the void but are themselves historical beings. Their own capacity to understand language has been nurtured in the past, and, if they remember and repeat what they are learning, they are helping to transmit (and, if needs be, to adapt) a living language from the past into the future.

Education is not 'just' concerned with teaching specific tasks but it entails forming and informing the whole person, for and through the experience of living through time.

Learning the French language is a valuable human enterprise, and not just for people who live in France or who intend to travel to France. Similarly, people learn about astronomy without journeying in space, about marine biology without deep-sea diving, about genetics without cloning an animal, about economics without running a bank, about History without journeying physically into the past, and so forth. The human mind can and does explore much wider terrain than does the human body (though in fact human minds and bodies do undoubtedly have an impressive track record in physical exploration too). Huge amounts of what people learn is drawn from the past that has not been forgotten. Furthermore, humans display great ingenuity in trying to recover information about lost languages and departed civilisations, so that everything possible can be retained within humanity's collective memory banks.

Very well, the critics then sniff; let's accept that History has a role. But the second criticism levelled at the subject is that it is basic and boring. In other words, if History is not meaningless bunk , it is nonetheless poor fare, consisting of soul-sapping lists of facts and dates.

Further weary sighs come from historians when they hear this criticism. It often comes from people who do not care much for the subject but who simultaneously complain that schoolchildren do not know key dates, usually drawn from their national history. Perhaps the critics who complain that History-is-so-boring had the misfortune to be taught by uninspired teachers who dictated 'teacher's notes' or who inculcated the subject as a compendium of data to be learned by heart. Such pedagogic styles are best outlawed, although the information that they intended to convey is far from irrelevant.

Facts and dates provide some of the basic building blocks of History as a field of study, but on their own they have limited meaning. Take a specific case. It would be impossible to comprehend 20th-century world history if given nothing but a list of key dates, supplemented by information about (say) population growth rates, economic resources and church attendance. And even if further evidence were provided, relating to (say) the size of armies, the cost of oil, and comparative literacy levels, this cornucopia of data would still not furnish nearly enough clues to reconstruct a century's worth of world experience.

On its own, information is not knowledge. That great truth cannot be repeated too often. Having access to abundant information, whether varnished or unvarnished, does not in itself mean that people can make sense of the data.

Charles Dickens long ago satirised the 'facts and nothing but the facts' school of thought. In his novel Hard Times ,( 1 ) he invented the hard-nosed businessman, Thomas Gradgrind, who believes that knowledge is sub-divided into nuggets of information. Children should then be given 'Facts' and taught to avoid 'Fancy' – or any form of independent thought and imagination. In the Dickens novel, the Gradgrindian system comes to grief, and so it does in real life, if attempts are ever made to found education upon this theory.

People need mental frameworks that are primed to understand and to assess the available data and – as often happens – to challenge and update both the frameworks and the details too. So the task of educationalists is to help their students to develop adaptable and critical minds, as well as to gain specific expertise in specific subjects.

Returning to the case of someone first trying to understand 20th-century world history, the notional list of key dates and facts would need to be framed by reading (say) Eric Hobsbawm's Age of Extremes: the Short Twentieth Century ( 2 ) or, better still, by contrasting this study with (say) Mark Mazower's Dark Continent ( 3 ) or Bernard Wasserstein's Barbarism and Civilization ( 4 ) on 20th-century Europe, and/or Alexander Woodside's Lost Modernities: China, Vietnam, Korea and the Hazards of World History ( 5 ) or Ramachandra Guha's India after Gandhi: the History of the World's Largest Democracy ( 6 ) – to name but a few recent overview studies.

Or, better again, students can examine critically the views and sources that underpin these historians' big arguments, as well as debate all of this material (facts and ideas) with others. Above all, History students expect to study for themselves some of the original sources from the past; and, for their own independent projects, they are asked to find new sources and new arguments or to think of new ways of re-evaluating known sources to generate new arguments.

Such educational processes are a long, long way from memorising lists of facts. It follows therefore that History students' understanding of the subject cannot be properly assessed by asking single questions that require yes/no responses or by offering multiple-choice questions that have to be answered by ticking boxes. Such exercises are memory tests but not ways of evaluating an understanding of History.

Some arguments in favour of studying History also turn out, on close inspection, to be disappointingly weak. These do not need lengthy discussion but may be noted in passing.

For example, some people semi-concede the critics' case by saying things like: 'Well, History is not obviously useful but its study provides a means of learning useful skills' . But that says absolutely nothing about the content of the subject. Of course, the ability to analyse a diverse array of often discrepant data, to provide a reasoned interpretation of the said data, and to give a reasoned critique of one's own and other people's interpretations are invaluable life- and work-skills. These are abilities that History as a field of study is particularly good at inculcating. Nevertheless, the possession of analytical and interpretative skills is not a quality that is exclusive to historians. The chief point about studying History is to study the subject for the invaluable in-depth analysis and the long-term perspective it confers upon the entire human experience – the component skills being an essential ingredient of the process but not the prime justification.

Meanwhile, another variant reply to 'What is the use of History?' is often given in the following form: 'History is not useful but it is still worthwhile as a humane subject of study' . That response says something but the first phrase is wrong and the conclusion is far too weak. It implies that understanding the past and the legacies of the past is an optional extra within the educational system, with cultural value for those who are interested but without any general relevance. Such reasoning was behind the recent and highly controversial decision in Britain to remove History from the required curriculum for schoolchildren aged 14–16.

Yet, viewing the subject as an optional extra, to add cultural gloss, seriously underrates the foundational role for human awareness that is derived from understanding the past and its legacies. Dropping History as a universal subject will only increase rootlessness among young people. The decision points entirely in the wrong direction. Instead, educationalists should be planning for more interesting and powerful ways of teaching the subject. Otherwise it risks becoming too fragmented, including too many miscellaneous skills sessions, thereby obscuring the big 'human story' and depriving children of a vital collective resource.

Much more can be said – not just in defence of History but in terms of its positive advocacy. The best response is the simplest, as noted right at the start of this conversation. When asked 'Why History?' the answer is that History is inescapable. Here it should be reiterated that the subject is being defined broadly. The word 'History' in English usage has many applications. It can refer to 'the past'; or 'the study of the past'; and/or sometimes 'the meaning(s) of the past'. In this discussion, History with a capital H means the academic field of study; and the subject of such study, the past, is huge. In practice, of course, people specialise. The past/present of the globe is studied by geographers and geologists; the biological past/present by biologists and zoologists; the astronomical past/present by astrophysicists; and so forth.

Among professional historians, the prime focus is upon the past/present of the human species, although there are some who are studying the history of climate and/or the environmental history of the globe. Indeed, the boundaries between the specialist academic subjects are never rigid. So from a historian's point of view, much of what is studied under the rubric of (for example) Anthropology or Politics or Sociology or Law can be regarded as specialist sub-sets of History, which takes as its remit the whole of the human experience, or any section of that experience.

Certainly, studying the past in depth while simultaneously reviewing the long-term past/present of the human species directs people's attention to the mixture of continuities and different forms of change in human history, including revolution as well as evolution. Legacies from the past are preserved but also adapted, as each generation transmits them to the following one. Sometimes, too, there are mighty upheavals, which also need to be navigated and comprehended. And there is loss. Not every tradition continues unbroken. But humans can and do learn also from information about vanished cultures – and from pathways that were not followed.

Understanding all this helps people to establish a secure footing or 'location' within the unfolding saga of time, which by definition includes both duration and change. The metaphor is not one of fixation, like dropping an anchor or trying to halt the flow of time. Instead, it is the ability to keep a firm footing within history's rollercoaster that is so important. Another way of putting it is to have secure roots that will allow for continuity but also for growth and change.

Nothing, indeed, can be more relevant to successful functioning in the here-and-now. The immediate moment, known as the synchronic, is always located within the long-term unfolding of time: the diachronic. And the converse is also true. The long term of history always contributes to the immediate moment. Hence my twin maxims, the synchronic is always in the diachronic . The present moment is always part of an unfolding long term, which needs to be understood. And vice versa. The diachronic is always in the synchronic: the long term, the past, always contributes to the immediate moment.

As living creatures, humans have an instinctive synchro-mesh , that gears people into the present moment. But, in addition to that, having a perspective upon longitudinal time, and history within that, is one of the strengths of the alert human consciousness. It may be defined as a parallel process of diachro-mesh , to coin a new term. On the strength of that experience, societies and individuals assess the long-term passage of events from past to present – and, in many cases, manage to measure time not just in terms of nanoseconds but also in terms of millennia. Humans are exceptional animals for their ability to think 'long' as well as 'immediate'; and those abilities need to be cultivated.

If educational systems do not provide a systematic grounding in the study of History, then people will glean some picture of the past and the role of themselves, their families, and their significant associations (which include everything from nations and religions to local clubs and neighbourhood networks) from a medley of other resources – from cultural traditions, from collective memories, from myths, rumours, songs, sagas, from political and religious teachings and customs, from their families, their friends, and from every form of human communication from gossip to the printing press and on to the web.

People do learn, in other words, from a miscellany of resources that are assimilated both consciously and unconsciously. But what is learned may be patchy or confused, leaving some feeling rootless; or it may be simplified and partisan, leaving others feeling embattled or embittered. A good educational system should help people to study History more formally, more systematically, more accurately, more critically and more longitudinally. By that means, people will have access to a great human resource, compiled over many generations, which is the collective set of studies of the past, and the human story within that.

Humans do not learn from the past, people sometimes say. An extraordinary remark! People certainly do not learn from the future. And the present is so fleeting that everything that is learned in the present has already passed into the past by the time it is consolidated. Of course humans learn from the past – and that is why it is studied. History is thus not just about things 'long ago and far away' – though it includes that – but it is about all that makes humanity human – up close and personal.

Interestingly, Henry Ford's dictum that 'History is bunk' now itself forms part of human history. It has remained in circulation for 90 years since it was first coined. And it exemplifies a certain no-nonsense approach of the stereotypical go-ahead businessman, unwilling to be hide-bound by old ways. But Ford himself repented. He faced much derision for his apparent endorsement of know-nothingism. 'I did not say it [History] was bunk', he elaborated: 'It was bunk to me '. Some business leaders may perhaps affect contempt for what has gone before, but the wisest among them look to the past, to understand the foundations, as well as to the future, in order to build. Indeed, all leaders should reflect that arbitrary changes, imposed willy-nilly without any understanding of the historical context, generally fail. There are plenty of recent examples as well as long-ago case-histories to substantiate this observation. Politicians and generals in Iraq today – on all sides – should certainly take heed.

Model-T Ford 1908

After all, Ford's pioneering Model T motor-car did not arrive out of the blue in 1908. He had spent the previous 15 years testing a variety of horseless carriages. Furthermore, the Model T relied upon an advanced steel industry to supply the car's novel frame of light steel alloy, as well as the honed skills of the engineers who built the cars, and the savvy of the oil prospectors who refined petroleum for fuel, just as Ford's own novel design for electrical ignition drew upon the systematic study of electricity initiated in the 18th century, while the invention of the wheel was a human staple dating back some 5,000 years.

It took a lot of human history to create the automobile.

Ford Mustang 2007

And the process by no means halted with Henry Ford I. So the next invention that followed upon his innovations provided synchro-mesh gearing for these new motorised vehicles – and that change itself occurred within the diachro-mesh process of shared adaptations, major and minor, that were being developed, sustained, transmitted and revolutionised through time.

Later in life, Henry Ford himself became a keen collector of early American antique furniture, as well as of classic automobiles. In this way, he paid tribute both to his cultural ancestry and to the cumulative as well as revolutionary transformations in human transportation to which he had so notably contributed.

Moreover, for the Ford automobile company, there was a further twist in the tale. In his old age, the once-radical Henry Ford I turned into an out-of-touch despot. He failed to adapt with the changing industry and left his pioneering business almost bankrupt, to be saved only by new measures introduced by his grandson Henry Ford II. Time and history had the last laugh – outlasting even fast cars and scoffers at History.

Because humans are rooted in time, people do by one means or another pick up ideas about the past and its linkages with the present, even if these ideas are sketchy or uninformed or outright mythological. But it is best to gain access to the ideas and evidence of History as an integral part of normal education.

The broad span of human experience, viewed both in depth and longitudinally over time, is the subject of History as a field of study.

Therefore the true question is not: 'What is the use or relevance of History?' but rather: 'Given that all people are living histories, how can we all best learn about the long-unfolding human story in which all participate?'

Back to the top

Suggested further reading

H. Carr, What is History? (rev. edn., Basingstoke, 1986).

Drolet, The Postmodern Reader: Foundational Texts (London, 2003).

J. Evans, In Defence of History (London, 1997).

Gunn, History and Cultural Theory (Harlow, 2006).

Jenkins, Re-thinking History (London, 1991)

Jordanova, History in Practice (London, 2000).

The Routledge Companion to Historical Studies , ed. A. Munslow (London, 1999).

P. Thompson, The Poverty of Theory (London, 1978).

Tosh, The Pursuit of History: Aims, Methods and New Directions in the Study of Modern History (many edns., London, 1984–).

Penelope J. Corfield is professor of history at Royal Holloway, University of London. If quoting, please kindly acknowledge copyright: © Penelope J. Corfield 2008

The Institute of Historical Research © 2008

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

Why Is History Important And How Can It Benefit Your Future?

History is a topic that many find boring to study or a waste of time. But there is more to studying history than meets the eye. Let’s answer the age-old question: “Why is history important?”

What Is History?

History is the knowledge of and study of the past. It is the story of the past and a form of collective memory. History is the story of who we are, where we come from, and can potentially reveal where we are headed.

Why Study History: The Importance

History is important to study because it is essential for all of us in understanding ourselves and the world around us. There is a history of every field and topic, from medicine, to music, to art. To know and understand history is absolutely necessary, even though the results of historical study are not as visible, and less immediate.

Allows You To Comprehend More

1. our world.

History gives us a very clear picture of how the various aspects of society — such as technology, governmental systems, and even society as a whole — worked in the past so we understand how it came to work the way it is now.

2. Society And Other People

Studying history allows us to observe and understand how people and societies behaved. For example, we are able to evaluate war, even when a nation is at peace, by looking back at previous events. History provides us with the data that is used to create laws, or theories about various aspects of society.

3. Identity

History can help provide us with a sense of identity. This is actually one of the main reasons that history is still taught in schools around the world. Historians have been able to learn about how countries, families, and groups were formed, and how they evolved and developed over time. When an individual takes it upon themselves to dive deep into their own family’s history, they can understand how their family interacted with larger historical change. Did family serve in major wars? Were they present for significant events?

4. Present-Day Issues

History helps us to understand present-day issues by asking deeper questions as to why things are the way they are. Why did wars in Europe in the 20th century matter to countries around the world? How did Hitler gain and maintain power for as long as he had? How has this had an effect on shaping our world and our global political system today?

5. The Process Of Change Over Time

If we want to truly understand why something happened — in any area or field, such as one political party winning the last election vs the other, or a major change in the number of smokers — you need to look for factors that took place earlier. Only through the study of history can people really see and grasp the reasons behind these changes, and only through history can we understand what elements of an institution or a society continue regardless of continual change.

Photo by Yusuf Dündar on Unsplash

You learn a clear lesson, 1. political intelligence.

History can help us become better informed citizens. It shows us who we are as a collective group, and being informed of this is a key element in maintaining a democratic society. This knowledge helps people take an active role in the political forum through educated debates and by refining people’s core beliefs. Through knowledge of history, citizens can even change their old belief systems.

2. History Teaches Morals And Values

By looking at specific stories of individuals and situations, you can test your own morals and values. You can compare it to some real and difficult situations individuals have had to face in trying times. Looking to people who have faced and overcome adversity can be inspiring. You can study the great people of history who successfully worked through moral dilemmas, and also ordinary people who teach us lessons in courage, persistence and protest.

3. Builds Better Citizenship

The study of history is a non-negotiable aspect of better citizenship. This is one of the main reasons why it is taught as a part of school curricular. People that push for citizenship history (relationship between a citizen and the state) just want to promote a strong national identity and even national loyalty through the teaching of lessons of individual and collective success.

4. Learn From The Past And Notice Clear Warning Signs

We learn from past atrocities against groups of people; genocides, wars, and attacks. Through this collective suffering, we have learned to pay attention to the warning signs leading up to such atrocities. Society has been able to take these warning signs and fight against them when they see them in the present day. Knowing what events led up to these various wars helps us better influence our future.

5. Gaining A Career Through History

The skills that are acquired through learning about history, such as critical thinking, research, assessing information, etc, are all useful skills that are sought by employers. Many employers see these skills as being an asset in their employees and will hire those with history degrees in various roles and industries.

6. Personal Growth And Appreciation

Understanding past events and how they impact the world today can bring about empathy and understanding for groups of people whose history may be different from the mainstream. You will also understand the suffering, joy, and chaos that were necessary for the present day to happen and appreciate all that you are able to benefit from past efforts today.

Photo by Giammarco Boscaro on Unsplash

Develop and refine your skills through studying history, 1. reading and writing.

You can refine your reading skills by reading texts from a wide array of time periods. Language has changed and evolved over time and so has the way people write and express themselves. You can also refine your writing skills through learning to not just repeat what someone else said, but to analyze information from multiple sources and come up with your own conclusions. It’s two birds with one stone — better writing and critical thinking!

2. Craft Your Own Opinions

There are so many sources of information out in the world. Finding a decisive truth for many topics just doesn’t exist. What was a victory for one group was a great loss for another — you get to create your own opinions of these events.

3. Decision-Making

History gives us the opportunity to learn from others’ past mistakes. It helps us understand the many reasons why people may behave the way they do. As a result, it helps us become more impartial as decision-makers.

4. How To Do Research

In the study of history you will need to conduct research . This gives you the opportunity to look at two kinds of sources — primary (written at the time) and secondary sources (written about a time period, after the fact). This practice can teach you how to decipher between reliable and unreliable sources.

5. Quantitative Analysis

There are numbers and data to be learned from history. In terms of patterns: patterns in population, desertions during times of war, and even in environmental factors. These patterns that are found help clarify why things happened as they did.

6. Qualitative Analysis

It’s incredibly important to learn to question the quality of the information and “history” you are learning. Keep these two questions in mind as you read through information: How do I know what I’m reading are facts and accurate information? Could they be the writer’s opinions?

Photo by Matteo Maretto on Unsplash

We are all living histories.

All people and cultures are living histories. The languages we speak are inherited from the past. Our cultures, traditions, and religions are all inherited from the past. We even inherit our genetic makeup from those that lived before us. Knowing these connections give you a basic understanding of the condition of being human.

History Is Fun

Learning about history can be a great deal of fun. We have the throngs of movies about our past to prove it. History is full of some of the most interesting and fascinating stories ever told, including pirates, treasure, mysteries, and adventures. On a regular basis new stories from the past keep emerging to the mainstream. Better yet, there is a history of every topic and field. Whatever you find fascinating there is a history to go along with it. Dive a bit deeper into any topic’s history and you will be surprised by what you might find in the process.

The subject of history can help you develop your skills and transform you to be a better version of yourself as a citizen, a student, and person overall.

If you are looking to develop more of yourself and skills for your future career, check out the degree programs that are offered by University of the People — a tuition-free, 100% online, U.S. accredited university.

Related Articles

Pursuit home

- All sections

What history can really teach us

History is too intricate to teach simple lessons, but knowing your history is key to understanding the complexities of the present

By Professor Mark Edele, University of Melbourne

Today, at the start of the 21st century, history matters enormously to many people.

In Eastern Europe, one country after another is passing laws about what can and cannot be said about its past . Even laughing about it cannot be tolerated – Russia’s Ministry of Culture, for example, banned the 2018 comedy The Death of Stalin .

But aside from government sensitivities, history remains perennially popular. In Australia, overall enrolments in upper level history courses have increased from just over 10,000 in 1995 to well over 24,000 in 2016.

And Australia’s so-called “history wars” continuously “ reignite ”, whether it be competing views over British colonisation and the dominance of war in the national story, to most recently the controversy over the establishment of university courses focused on the history of western civilisation .

At my home institution, the University of Melbourne, the chair I occupy, as well as four other teaching positions in History, only exist because generous philanthropy driven by this appreciation for the past.

No laughing matter: The Death of Stalin and Putin's anxieties

Why are we so concerned with history?

It is partly because history is so closely tied to identity. History can serve as the foundation of a positive sense of self, either as part of a nation, of an empire, or a civilisation.

Indeed, the role of history in shaping national identities helped to establish it as a modern discipline – it rose together with the nation state.

But the professionalisation of history has long outgrown the nationalist impulse which originally fostered it.

Academic history is so committed to the factual record and to the disciplined study of sources, that its practitioners are now often at odds with their “end users” who either want an uncomplicated story of their own heritage, or a straightforward narrative of victimisation of the group they identify with.

But there is another reason to study history – to hopefully learn from it.

In what has been mocked as a failed job application, two Harvard academics have even called for the establishment of a “White House Council of Historical Advisers.”

This group of history sages would “begin with a current choice or predicament and attempt to analyse the historical record to provide perspective, stimulate imagination, find clues about what is likely to happen, suggest possible policy interventions, and assess probable consequences.”

There is only one problem with this idea to use history to help policy makers avoid mistakes – it seldom works.

Lucky discoveries of lost ancient history

Historical situations are so complex, that clear parallels are rare. Historical analogies can obscure the real situation rather than elucidate it, as a major study of the phenomenon points out.

The decision to send Marines to start ground operations in Vietnam in 1965 , or the intervention in Iraq in 2003 are among the disastrous choices made by historically well-read policy makers.

There are of course counter examples – American de-escalation of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 was partially driven by President John F. Kennedy remembering how World War I had started.

More recently, the memory of the Great Depression helped temper responses to the 2007-08 global financial crisis. On balance, however, the knowledge of history doesn’t guarantee good decision making.

Nor does it make you a better human being.

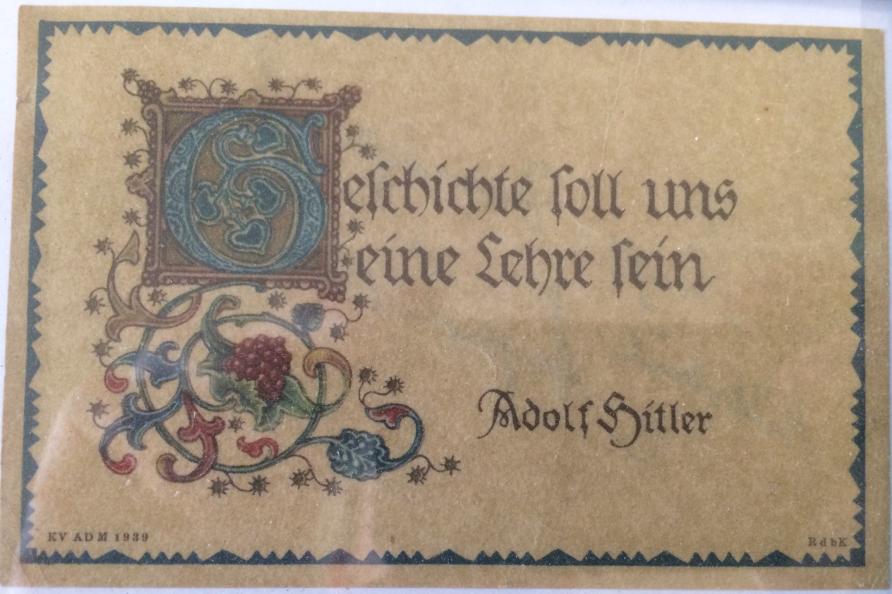

“History exists, so we can learn from it,” exclaims a 1930s bookmark signed by one Adolf Hitler.

Joseph Stalin’s library included closely annotated history volumes. The Soviet dictator was a keen student of the French Revolution, which had helped Napoleon into power.

Stalin also remembered World War I, when total war led to revolution. As a result he instituted the Great Terror of 1937-38 when nearly 700,000 people were shot in order to prevent history repeating itself.

Stalin also learned from the longer sweep of Russian history – that people needed the firm hand of a Tsar, that Russia had always been beaten because the country was weak and backward, and that weak leadership led to disaster.

He acted accordingly. Stalinism was a learned response of a diligent history student.

Rome's Augustus and the allure of the strongman

Why then should students pursue history majors? Why should the broader public read history? There are two main reasons.

One is concern with the present – how did we get here? This approach to history doesn’t try to teach lessons from the past in order to help us make decisions by blunt analogy. Instead, it enlightens us about the legacies of what came before us. It gives us a deeper understanding of the complexities of the present.

Rather than constructing analogies between Putin’s Russia, and, say, Stalinism or the pre-Soviet Romanov empire, “applied historians” might well inform decision makers and the broader public of what historical baggage Russian , Ukrainian or Polish actors bring to the table .

Rather than constructing analogies, historians of the present might help to dismantle facile lessons from the past. They can free our minds to face challenges of the present.

The second approach to history could be called “historicist” and it insists on understanding the past on its own terms.

By immersing themselves into the traces of the past, historians can begin to understand fundamentally different ways of living. This approach can be romantic and escapist, but not necessarily.

It teaches students and history enthusiasts an analytical empathy for the past that focuses on context and reflects careful reading of primary sources – practices which are widely transferable.

History then can teach analytical and emotional abilities, and convey real knowledge about the real, contemporary world. This knowledge is gained by disciplined study of primary sources and careful interpretation of historiography.

In times of post-truth politics, these are essential skills.

Banner: Getty Images

Sure, We Teach History. But Do We Know Why It’s Important?

- Share article

In 1980, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians began hearing testimony from Japanese-Americans who, after the Pearl Harbor attack, were forced at gunpoint into prison camps throughout the desolate interior of the United States.

Initiated by Sen. Daniel Inouye, a Hawaii Democrat who lost an arm fighting the Nazis, the commission was largely conceived in order to establish a legal and political case in Congress against internment and for some kind of redress. But Nisei men and women, the children of Japanese immigrants who had kept virtually silent for decades due to a social code inherited from their ancestors, captured the moment. They used the hearings to share their stories of sorrow and humiliation. The intense emotion of these personal histories galvanized a political movement that succeeded in winning monetary reparations from the federal government for those who had been interned. It was an unprecedented event in the American experience.

As my father, the Japanese-American Citizens League’s volunteer chief legislative strategist who helped convince President Ronald Reagan to sign the redress bill in 1988, later recalled, “I saw all these old people crying, and that made me cry. I guess the whole community cried.”

When the nation feels not just divided, but divided in an unprecedented way, studying history serves as a guide. A nation that can see through and place the turbulent present in historical context is better empowered to grasp the present and decide on the best course of action ahead.

Those who work in classrooms and with students grasp this. In a recent survey of educators who were presented with two choices, 78 percent told EdWeek Research Center they believed the primary purpose of teaching history is “to prepare students to be active and informed citizens,” compared with 22 percent who said the primary purpose of teaching history is “to teach analytical, research, and critical thinking skills.” (We should not, of course, label the second group wrong.)

Therefore, we study and share history in part to give us the foundation for action. We build that foundation in part by learning and sharing stories of immigrant forebears and their legacies; the 1619 Project from the New York Times, which consists of a series of essays about the legacy of slavery, does something similar, but in a fashion that its creators want to be unsettling, if not excruciating for many.

Telling different stories within a single broader narrative, and using those stories to create empathy within an agreed-upon historical framework, are powerful skills. Indeed, one of the key strategies for Japanese-American redress activists in Washington was—to use my father’s metaphor—selling the same Ford Taurus sedan in two different ways.

For a liberal audience, the main argument went like this: These immigrants and their children were the victims of powerful white men who, in the name of national security, exploited wartime panic and longstanding anti-Asian bigotry among other whites to deprive Japanese-Americans of their civil liberties.

For conservatives, the tougher audience, it went this way: Japanese-Americans were content to obey the law and grow artichokes and strawberries. They were exemplary models of enterprise, the free market, and family values—until they were deprived of private property rights and denied due process by an overbearing federal government.

Together, these arguments succeeded because both narratives underscored the ideals that presumably governed American history, and how internment undermined those ideals.

78% of teachers identify preparing students for citizenship as the main reason to teach history."

This should not be confused with warping history as if for some kind of novelistic experiment, or perverting it for political control. In his 1946 essay “ The Prevention of Literature ,” George Orwell wrote that totalitarian governments approach history as “something to be created rather than learned.”

But in classrooms, it has always been a struggle to teach history in a way that resonates with students. The CEO of Baltimore City schools, Sonja Santelises, thinks she’s found a way to do that: Help them see themselves up close in their hometown’s history.

Motivated partially by Baltimore’s often-negative portrayal in the media, Santelises recently oversaw the implementation of BMore Me, a social studies curriculum. The basic idea is “using the city as a classroom.”

They’ve explored how local geography impacted the Industrial Revolution in Baltimore. They learn what the history of certain neighborhoods reveals about the nation’s history of red-lining black families away from valuable land and capital. And they’ve heard stories from a community elder about singer Billie Holiday, who grew up in Baltimore, and from D. Watkins, who went from dealing drugs in the city to teaching at the University of Baltimore.

Santelises said the city curriculum’s emphasis on this approach that allows students to see themselves in history puts their own lives and people they know at the center of what can feel detached and distant. The consequences for this approach, if done right, can be profound, she argued.

“What makes people proud to be American? Well, part of it is that you’re validating people’s stories,” Santelises told me. “You’re validating their role.”

What’s also central to this approach, Santelises says, is that it allows children to see complexity in history and not just (in the case of black Americans, for example) one long and painful struggle against oppression.

“We don’t have to have a perfect or one story,” Santelises said. “That’s not the goal.”

In 1945, a young Army captain spoke at a service honoring Kazuo Masuda, a Japanese-American soldier who died in combat in Italy and whose family had been interned. This Army captain said men like Masuda were heroes, distinguished by their sacrifice and love of country, not their race.

That captain’s name was Ronald Reagan. Decades later as president, he was initially opposed to redress for internment. But when Reagan was reminded of that moment, he changed his mind. It was crucial for Reagan to see himself as a character in a crucial moment in American history.

The arc of that narrative can be questioned. Why did it take this chance moment in history to shift Reagan’s views? Why did men like Masuda have to prove their loyalty to the land of their birth? What about those Japanese-Americans who out of principle resisted military service?

Trying to answer those questions adds to the story I just laid out rather than subverting it. Still, it’s one story. History doesn’t always provide such dramatic, clear narratives. Similarly, what if such historical inquiry like the kind Santelises supports for her city’s students can’t be scaled up or made to work well elsewhere?

To such questions, Santelises responds that the approach in general can apply in all sorts of places for all kinds of students.

“Once you’re grounded and validated in the power of your own story,” Santelises said, “that’s what makes you want to go and learn about other people.”

The story of how President Ronald Reagan approved monetary reparations for Japanese-Americans interned during World War II is a long and complicated one. Learn more about the story and the role that author Andrew Ujifusa’s father played in it in this Twitter thread . A version of this article appeared in the January 08, 2020 edition of Education Week as Why Do We Study History?

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Department of History

College of humanities and sciences, why study history, what historians do.

Historical knowledge is no more and no less than carefully and critically constructed collective memory. William H. McNeill Why Study History? (1985)

It is a common misperception that the academic discipline of history consists of the memorization of unchanging facts about people who are long dead. People often equate history to a game of trivia, and therefore see it as a discipline with little practical applicability.

The study of history begins with questions, not answers. We seek to know what happened in the past, and we also seek to understand why – that is, how we should understand connections between one historical circumstance and another. In the process of seeking that understanding, historians work with historical evidence - evidence both written and oral, evidence embedded in both objects and texts, evidence in forms raging from numerical data to poetry and art. Meanwhile, as our present-day context raises new challenges for our communities, historians are inspired to ask new questions about the past, seeking understanding of a broad variety of human experiences. Historians explore questions about past politics and economics, intellectual developments, social concerns shaped by race, gender, and class, and facets of culture ranging from arts and languages to human spaces and emotions. As a result, the study of history is dynamic, rather than static, and those trained in this discipline develop valuable skills in gathering, evaluating, connecting, and interpreting factual information, and in the use evidence to argue persuasively for their conclusions.

History majors therefore graduate with analytical skills that equip them for a variety of employment opportunities. Employers value the skills history develops in the analysis of a variety of complex information, the clear and accessible communications and writing skills, and the management of time and projects. The strength and versatility of a history degree prepares students for successful careers in fields as diverse as teaching, museum curatorship, communications, public policy, sales and entrepreneurship, and managerial positions of many kinds.

- Here's which humanities major makes the most money after college , Mic, 5/12/15

- Surprise: humanities degrees provide great return on investment , Forbes, 11/20/14

- Connecting the dots: why a history degree is useful in the business world , Perspectives on History, 2/1/15

- Liberal arts in the data age , Harvard Business Review, July-August 2017

- 11 reasons to ignore the haters and major in the humanities , Business Insider, 6/27/13

- History is not a useless major: fighting myths with data , Perspectives on History, 5/1/17

The Historian's Skill Set

Given that history is such a dynamic field of inquiry, it would not make much sense if history majors were trained merely to recite factual information, or the interpretations of those facts endorsed by their professors. Instead, the goal of education in history is to impart a set of broadly-applicable skills to our students, skills which make them better at both consuming and imparting information. Our faculty envision the skills our graduates should have as follows:

- Information gathering: Graduates of our program should be able to gather information effectively from a variety of sources.

- Critical thinking: Graduates should be able to think critically about information, forming independent judgments based upon reliable evidence.

- Communication: Graduates should be able effectively to communicate their evidence-based observations and judgments, in oral/verbal and more lasting formats.

- Professionalization: Graduates should be able to perform according to workplace standards of professionalism, demonstrating independent initiative, accountability, adaptability and professional ethics.

In order to acquire these skills – skills which have applicability across a wide variety of careers – we require students not only to become familiar with the general narratives of human history, but also to explore, discuss and interpret the past by engaging with both documentary evidence and with historical debate. Thus, our classrooms and syllabi seek to develop the core skills outlined above by asking the following of our students:

- Research: Students in this program will locate information independently, and evaluate its utility for their purposes.

- Critical reading: Students will engage with a wide variety of texts, and glean useful information from them.

- Critical thinking about evidence: Students will evaluate the quality and utility of sources used to understand the past, keeping in mind their context, and purpose. Students will also make useful connections among disparate sources of information about history, and be able to propose causal relationships among them.

- Formulation of analysis: Students will use both historical sources and logical inferences to construct plausible interpretations of the past.

- Writing: Students will strive to write clearly, accurately, persuasively and elegantly, and to employ the research apparatus normative to historical scholarship.

- Presentations: Students will present information and arguments about the past in other formats, such as oral presentations, museum exhibits, archival guides, web-based presentations and so on.

- Project management and interpersonal engagement: Students will strive to work through the stages of any project or assignment in an organized and proactive manner, showing independence, timeliness, professional ethics, problem-solving skills, teamwork and collaboration, integrative learning and the transfer of skills, self-assessment and good judgment in seeking support or resources.

Active and Experiential Learning in History

People sometimes think that history courses are about sitting passively through long lectures and learning long lists of dull facts. Nothing could be further from the truth! Active, experiential learning lies at the heart of what we do in history courses .

We access the past through reading primary sources such as diaries, letters, court records, newspapers, movies and interviews – amazing windows into the past that history courses will teach you how to use effectively. We also use books and essays written by professional historians. History courses teach you how to extract arguments from these texts, compare them critically, and understand how historians' approaches to understanding the past have evolved over time (what we call "historiography"). We learn a range of applied skills, including archival research, digital/data analysis, oral history and role-playing, how to give oral presentations and how to present clearly organized, convincing arguments in written papers. History students get to visit museums and historical sites. They meet visiting historians, listen to them talk about their work and talk with them about their own work. Furthermore, the Department of History offers a range of exciting internships in the local community, and VCU has two clubs for history students, History Now! and the Alexandrian Society . Students can engage actively with the past not just here at VCU and in Richmond but throughout the world by signing up for Study Abroad programs.

As a history major, the world is at your fingertips!

Home — Essay Samples — Education — Study — History’s Value: Influence Of History Background On Modern Well-Being

History's Value: Influence of History Background on Modern Well-being

- Categories: Oral History Study

About this sample

Words: 1524 |

Published: Mar 1, 2019

Words: 1524 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Table of contents

History helps us understand people and societies, history provides identity, the importance of history in our own lives, history is useful in the world of work, works cited.

- acquiring a broad range of historical knowledge and understanding, including a sense of development over time, and an appreciation of the culture and attitudes of societies other than our own

- evaluating critically the significance and utility of a large body of material, including evidence from contemporary sources and the opinions of more recent historians

- engaging directly with questions and presenting independent opinions about them in arguments that are well-written, clearly expressed, coherently organized and effectively supported by relevant evidence;

- gaining the confidence to undertake self-directed learning, making the most effective use of time and resources, and increasingly defining one’s own questions and goals.

- Carr, E. H. (1961). What is history? Random House.

- Gaddis, J. L. (2002). The landscape of history: How historians map the past. Oxford University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. (2012). On history. New Press.

- Jenkins, K. (2011). Re-thinking history. Routledge.

- Marwick, A. (2006). The nature of history. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nash, G. B. (2015). American odyssey: The United States in the twentieth century. Oxford University Press.

- Scott, J. W. (1991). The evidence of experience. Critical inquiry, 17(4), 773-797.

- Tosh, J. (2017). The pursuit of history: Aims, methods and new directions in the study of history. Routledge.

- White, H. (2014). The content of the form: Narrative discourse and historical representation. JHU Press.

- Wineburg, S. S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Temple University Press.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 416 words

1 pages / 575 words

2 pages / 816 words

2 pages / 990 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Study

Paulo Freire's essay, "The Banking Concept of Education," challenges traditional educational paradigms and offers a thought-provoking critique of the way knowledge is imparted in traditional classrooms. In this essay, we will [...]