My Ideal World Essay & Paragraphs For Students

As a kid, I loved imagining what the perfect world would be like. In this essay, I will describe my vision for an ideal place where everyone is happy and things work smoothly. One day, real life could be just as great as the world in my head.

Table of Contents

Essay On My Ideal World

In my ideal world, there would be no bullying or rude behavior between people. (Topic sentence) Everyone would treat each other with kindness like best friends do. No one would feel left out or made fun of, so confidence and teamwork could reign supreme instead of nasty attitudes. With smiles as currency, who would not want to get up each morning in such a light-filled land?

Fair (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Rules and Leaders

Another key part of my ideal place involves leaders focused on the greater good. Laws and guidelines would unite communities by being reasonable, not overbearing. (Transition) Listening to citizens and compromising would solve problems, not force. (Topic sentence) Leaders lead by moral example, so trust between governance and people could eliminate corruption. Civic participation empowers all voices while shared hope for the future ties society close.

A Clean Environment

My perfect world also cares deeply for the natural realm, providing for our needs and wants. Clean water, fresh air and healthy soil maintain a sustainable balance. (Transition) Eco-initiatives create green jobs while renewing resources for generations ahead to discover nature’s beauty. (Topic sentence) Respecting inhabitants, big and small, teaches humanity that nature’s wonders come with caring for all. Together as stewards, our earth and its inhabitants thrive prosperously as one community joined in hands.

Advanced Technology

Though simple in ways, technological progress moves society closer to my ideal, with discoveries improving lives every day. Medical breakthroughs cure illness; efficient cars run on air. Machines handle labor so creativity and relationships can blossom freely. (Transition) However, nature remains treasured, and machines serve not to overtake humankind. Online worlds unite distant friends while safeguarding privacy. Advances enhance life’s experiences when guided with wisdom.

Lasting Peace

Most of all, peace would exist between all people and nations in a perfect world. Cooperation overcomes squabbling over perceived differences for the sake of shared hopes. (Topic sentence) Understanding, compassion and nonviolence resolve conflicts, so energy focuses on mutual interests like science, arts and exploration. Without fear of harm, the fullest potential of the human spirit could flourish across borders as one.

In closing, while still just a dream, envisioning an ideal world motivates making real life closer bit by bit. With effort gradually shifting perspectives on what moves society ahead harmoniously, one day, compassion will be reality’s common currency where all people’s voices and inherent worth ring clear. I hope such a world might pass through each small act of kindness.

Hello! Welcome to my Blog StudyParagraphs.co. My name is Angelina. I am a college professor. I love reading writing for kids students. This blog is full with valuable knowledge for all class students. Thank you for reading my articles.

Related Posts:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Corrections

What Is the Ideal World? 5 Utopias Proposed by Famous Philosophers

What is the ideal world? Is it a utopia where everyone is happy and has no material problems? Or is it something else?

What would an ideal world look like? Most of us would agree that an ideal world is a place where everyone can live in peace and harmony; a place where there is no poverty or hunger, and where all people have the opportunity to reach their full potential. Unfortunately, there is no definitive answer to this question as it is, at least to some degree, a matter of personal opinion.

Some believe that the ideal state is one where everyone is happy and content with their lives. Others may think that the ideal state is one where there is perfect harmony and balance between all individuals and groups. Ultimately, what constitutes an ideal state depends on the values and beliefs we prioritize. In this article, we’ll take a look at the ideal world according to five famous philosophers: Plato, Thomas More, Campanella, Burke, and Godwin. We will explore what they believe the perfect world would look like and what it takes to get there.

1. Plato’s Ideal World: A Perfectly Balanced State

The theory of the ideal state is most fully represented by Plato in the Republic, and it was further developed in the Laws . According to Plato, true political art is the art of saving and educating the soul; therefore, he puts forward the thesis that true philosophy coincides with true politics. Only if a politician becomes a philosopher (and vice versa) can a true state be built based on the highest values of the Truth and the Good.

The ideal state, according to Plato, like the soul, has a tripartite structure. Following this tripartite structure (management, protection, and production of material goods), the population is divided into three classes: producers or workers, auxiliaries, and guardians or soldiers. A fair state structure should ensure their harmonious coexistence.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

The first and “lowest” class is formed from people whose lustful tendencies prevail. The second, protective class of people is formed from people in whom the strong-willed principle prevails. They feel a watchful duty and are vigilant against both internal and external danger. If the virtue of moderation and a kind of love for order and discipline prevails in a person, then they can be part of the most worthy class of people, and it is those who are meant to manage the state.

According to Plato, only aristocrats are called to govern the state as the best and most wise citizens. Rulers should be those who know how to love their City more than others and who can fulfill their duty with the greatest zeal. Most importantly, these rulers need to know how to recognize and contemplate the Good. In other words, the rational principle prevails in them, and they can rightfully be called “sages”.

So, a perfect state is the one in which the workers are guided by moderation, the military by courage and strength, and the ruling class by wisdom.

The concept of justice in an ideal state is based on the idea that everyone does what they have to do; it concerns the citizens in the City in analogy with the parts of the soul in the soul. Justice in the outer world is manifested only when it is also present in the soul. Therefore, in a perfect City, the education and upbringing of citizens must be perfect, and this education will have to be tailored to each class in a specific way.

Plato attaches great importance to the education of guards as an active part of the population from which rulers emerge. Education worthy of rulers had to combine practical skills with the development of philosophy. The purpose of education is to give a model that the ruler should use in an effort to embody this Good in the state.

In the Republic Plato states that living in an ideal world is not as important as it might seem. It can be good enough to live according to the laws of this City, that is, according to the laws of the Good, Truth, and Justice. After all, before appearing in reality externally, that is, in history, the Platonic City is first born inside people themselves.

2. The Utopian Wonder Island by Thomas More

Utopia by Thomas More , written in 1516, is the book that gave the name to the corresponding genre in literature and the new model of the ideal world. More’s Utopia is an island nation. The king rules in this state, but the highest administrative positions are elected. The problem, however, is that every citizen of Utopia is tightly tied to their professional corporation, which means they have no chance of gaining access to management.

Since the rulers are very far-removed from the people, there is no single thought-out ideology or religion on the island: belief in a single deity is preferred, but everyone is free to think through the “details” at their own discretion. You can be Christian or a pagan. It cannot be said that some Gods are better than others or that no Gods exist at all.

There is no money and private property on the island. Organized distribution of goods has completely supplanted free trade, and instead of the labor market, there is a universal labor service. Utopians do not work very hard, but only because enslaved people do the dirty and hard work. The islanders enslave their citizens as punishment for shameful acts; alternatively, foreigners awaiting execution for a crime they committed can also be enslaved.

Under these conditions, no aesthetic diversity is possible: the life of one family is no different from the life of another; language, customs, institutions, laws, houses, and even the layout of cities throughout the island are the same.

Of course, the project of the English writer was never realized, but some of its features are easy to recognize in contemporary states. These similarities are not due to funny coincidences, but due to universal patterns. For example, More believed that rejecting private property inevitably led to a cultural unification – something that can be observed in states where private property was limited in some way. Another obvious insight we can take from More’s utopia is the following: without a technological breakthrough, it is possible to reduce the labor load for some citizens only by super-exploiting others.

3. The City of the Sun by Tommaso Campanella

The ideal world model of Tommaso Campanella’s City of the Sun is perhaps the most famous and most “totalitarian” of all utopias. In the City of the Sun , according to the utopian idea, all kinds of teaching aids were to be depicted right on the walls: trees, animals, celestial bodies, minerals, rivers, seas, and mountains.

All troubles, all crimes, Campanella believed, came from two things – from private property and from the family. Therefore, in the City of the Sun, everything is a common good, and monogamous marriage and the right of parents to have a child are declared a relic of the past. “Solariums”, these new utopian citizens, always work together, they eat only in common dining rooms, and sleep in shared bedrooms.

The ideas of democracy are alien to solariums. A caste of priest-scientists leads the city: the high priest, named Metaphysician or the Sun, and his co-rulers – Power, Wisdom, and Love. Nobody chooses them; on the contrary, the supreme rulers appoint all the lower-lever leaders, priests-scholars of the lowest rank.

Science is the religion of solariums. The goal of their life is to climb the steps of rational knowledge. And it is built in strict accordance with scientific principles, which, in turn, are applied to everyday empiricism by priests.

At the top of the temple are twenty-four priests who, at midnight, at noon, morning, and evening, four times a day, sing psalms to God. They must observe the stars, mark their movements with the aid of an astrolabe, and study their powers and effects on human affairs. By doing this they know what changes have occurred or are about to occur in certain areas of the earth and at what time. They determine the best times for fertilization, the days of sowing, harvesting; they are, in a sense, transmitters and a link between God and people.

You might read this description and think: what is wrong with this harmonious system? Where does it fail? Why is a society governed by scientists and based on science not viable? One could argue that the City of the Sun is not a utopia because a person cannot be happy without the opportunity to be alone with themselves, with their wife/husband, children, favorite things, and even their sins. Like any other utopia that forgoes private property, Campanella’s utopia deprives a person of this type of happiness.

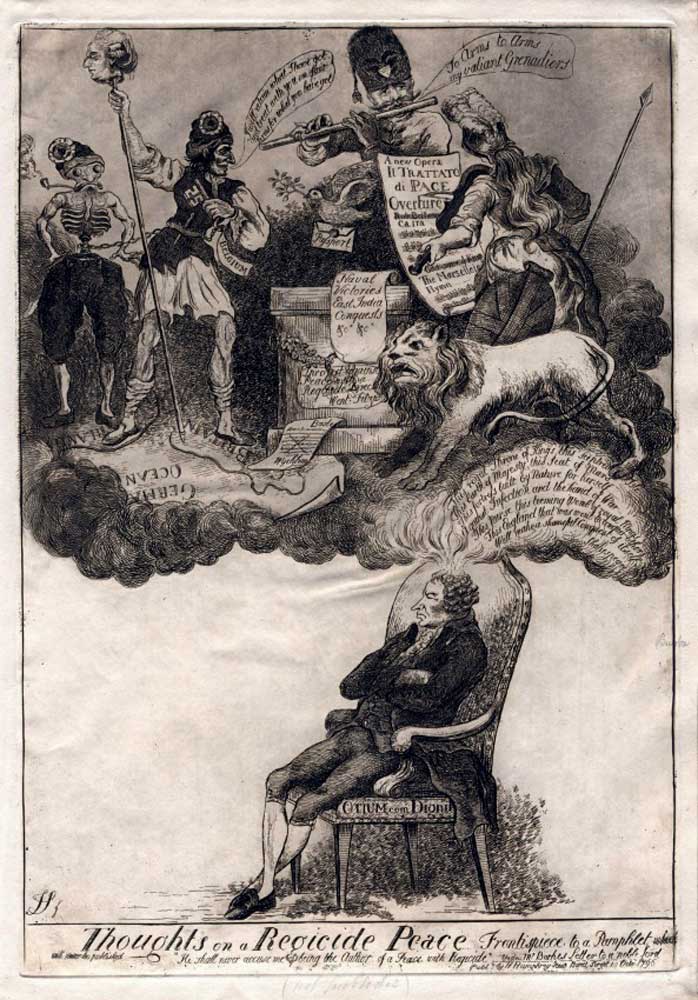

4. Burke’s Conservative Utopia

Edmund Burke is the founder of the ideology of conservatism . His Vindication of Natural Society is the first conservative utopia. It was written by Burke in response to Viscount Henry Bolingbroke’s Letters on the Study and Use of History , in which the latter attacked the Church. Burke, interestingly, does not defend the institutions of religion, but the institutions of the state, showing that there is as much sense in their elimination as in the elimination of church institutions.

The philosopher resorts to an ironic form of presentation of an ideal world. He describes every form of government known to humanity. Burke says that all of them – in direct or roundabout ways – lead a person to slavery. Therefore, he suggests, let’s abandon the state and live according to the laws of a “natural society.” If political society, whatever form it may take, has already turned the majority into the property of a few and has led to the emergence of exploitative forms of work, vices, and diseases, then should we continue to worship such a harmful idol and sacrifice our health and freedom to it?

Burke believes that a completely different picture is observed in the state of nature. There is no need for anything that nature provides. In such a state, a person cannot experience any other needs than those that can be satisfied by very moderate work, and, therefore, there is no slavery. There is no luxury here either because no one alone can create the things necessary for it. Life is simple and, therefore, happy.

However, Burke is ironic. His point of view lies precisely in the fact that no development of society is possible without historical continuity, without relying on already existing political, social, and religious institutions. For him, the existing state is natural, and any revolutionary project that breaks social reality is artificial.

5. Godwin’s Anarchist Utopia

Many ignored Burke’s irony and seriously considered him as a theoretician of anarchism . One such person was William Godwin , inventor of the first real anarchist utopia. In the opening part of his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice , he mostly paraphrases Burke, and in the second, he offers a positive program.

At the center of Godwin’s ideal worldview is the individual, whose entire behavior is determined by reason. A society can only be healthy if it is built on the principles of reason. There is only one truth, which means that the true structure of society is only one. It is hardly worth looking for this arrangement in the past because the whole history of humanity is a history of crimes. It is a history of state violence against an individual. And not only the state, but in general, everything that enslaves the mind imposes a unifying norm on it.

An ideal person in Godwin’s worldview is the eternal “enemy of the state”. Godwin believes that humanity is waiting for a New Era where small and self-sufficient communities populated by new people will replace states.

So, What Is The Ideal World?

It’s a question that many people have asked over the centuries, and no single answer has satisfied everyone. In this article, we looked at five different perspectives on the ideal state from famous philosophers. Each of them had their own idea about what constituted a perfect world and how to get there. While their views differed in some ways, they all agreed that striving for something better than the world we live in today was important. And to get there, we’ll need to change our ways and work together towards a common goal.

Plato’s Philosophy: 10 Breakthroughs That Contributed to Society

By Viktoriya Sus MA Philosophy Viktoriya is a writer from L’viv, Ukraine. She has knowledge about the main thinkers. In her free time, she loves to read books on philosophy and analyze whether ancient philosophical thought is relevant today. Besides writing, she loves traveling, learning new languages, and visiting museums.

Frequently Read Together

Plato’s Republic: Who Are the Philosopher Kings?

Utopia: Is the Perfect World a Possibility?

What Did Martin Heidegger Mean By “Science Cannot Think”?

Just another weblog

What is an ideal world? How would I act in an ideal world as an ideal citizen?

An ideal world would be a much more friendly, helping environment compared to today’s society. In the world today, all individuals have the tendency to be rude, judgmental, competitive, and hostile, just for some examples. In an ideal world, the majority of these tendencies would not exist. No one has the power to stop people from acting all of these different ways, but the way people act can be improved. To improve the world around us, people need to learn to accept others for who they are. Individuals tend to judge each other on all different aspects such as race, gender and sexual orientation. If judgment such as this could be eliminated, that would be one step closer to an ideal world. Another great aspect to improve in society is hostility. There is not hostility just between individuals, but between different nations in today’s society and that makes for an unpleasant environment in parts of the world. An example of this would be the Malaysia Airlines plane that was shot down over Ukraine in mid-July this past summer. This event has caused much hostility among the different countries over the past couple of months. To become an ideal citizen in an ideal world, I would try to make myself a better person than what I am now. However, I would not try to completely change who I am either. One aspect of myself that I would change is that I would try to always look at events with a positive view and try to keep all negative thoughts away from me. This would help me with other aspects such as being less judgmental and being a happier person. Another way I would improve myself is by getting even more involved in my community and I would try to achieve all of my goals to the best of my ability. By being this better person, I would not only be a better member of society but I would be changing myself to better my own future.

4 Comments on What is an ideal world? How would I act in an ideal world as an ideal citizen?

Alejandro Cuevas

Coming back to the utopia part (I’m sorry if I’m sounding obnoxious or something like that, I simply love debates and other people’s opinions on things) I believe that a society in which everybody looks for each other and strives to ultimately help others doesn’t maintain or human nature. We humans are drive by our self-interests, we are egotistical by nature. (This belief is better explained in http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Psychological_egoism.html ) So, in a society where altruism is the ultimate drive for people’s actions, is our human nature maintained? What are we saving? What do we become? We live in a wonderful society in exchange of losing our natural behavior. And you may say then, well, a certain degree of egoism may be present then in people’s lives. But well, then again, from that starting point sprouts traits such as competitiveness.

Stephanie Reed Springer

Alejandro, I disagree to some extent with your assertions that we need to be judgmental and competitive. I think the way Marisa is defining it, being judgmental means having unfair prejudices. She explains that people form opinions based on characteristics like sexual orientation, gender, and race. Judgments based on these factors are actually prejudices, meaning you are lumping an entire group of people under certain stereotypes. These types of judgments are never okay. Where I agree with you is that we do have to judge others on occasion, but we should never do it without getting to know them first. For example, we must determine with whom we want to be friends. Obviously, we can’t be friends with everyone and will have to judge who we like and have shared interests with. On the topic of competition, I think that in a true utopia, you could do away with competition and be motivated solely by self-improvement and the desire to help others.

While I definitely like to believe in the idea of an “ideal world”, to what extent will this be good? For instance, you mentioned some bad traits like “judgmental” or “competitive”. What would happen to the world if there was no sense of competitiveness between individuals? And I’m parting from the point that this sense of competitiveness usually sparks progress and self-superation in society. Or, for instance, being judgmental is also a “necessary evil” (if you want to call it that). We need somebody to point out our flaws in order to improve. It is hard to accept, but ultimately necessary. While I’m not seeking to avow these two “traits” in their full extent, it is important to not rule them out completely. An utopia usually brings to your mind happiness, joy, and a sense of peacefulness. However, to what degree is an utopia actually related to this? Can humans achieve such state while maintaining their inherent human behaviors (that is, the traits and attitudes that define your humanity)?

I like the classification that you made with the unpleasant characteristics of people who are rude, judgmental, competitive, and hostile. I think that these traits stem from something deeper, and that is the insecurity that each one of us feels. People would have no reason to try to look down on one another or prove individual worth if each person was fully content with himself or herself. I think that it is this internal issue that is manifested through our interactions with other people. In order to become this ideal person in an ideal world, like anyone else, you must start with this internal issue first.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Skip to main content

India’s Largest Career Transformation Portal

Essay on My vision of an ideal world order

September 30, 2019 by Sandeep

If you had the power to model and shape an ideal world order, what would your vision be? In order to envision this, there several more questions to introspect on. What kind of world would we want to live in?

What would that look like? What kinds of activities would be at the forefront of culture? In what areas would the most energy be devoted to? What kind of role models would be best for your ideal world?

Once these questions, among many more, are answered to your satisfaction, you will have a rough idea of what your ideal world order would be. But before that, let us understand what a world order is.

What is World Order?

The definition of a world order is a system controlling events in the world, especially a set of arrangements established internationally for preserving global political stability. It is an international-relations term describing the distribution of power among world powers.

World order as a term can be used both analytically and prescriptively. Both usages serve important purposes in grasping the realities of political life on a global level. Analytically, world order refers to the arrangement of power and authority that provides the framework for the conduct of diplomacy and world politics on a global scale.

Prescriptively, world order refers to a preferred arrangement of power and authority that is associated with the realisation of such values as peace, economic growth and equity, human rights, and environmental quality and sustainability. This essay is in reference to world order prescriptively.

My Ideal World Order

My ideal world order would contain several different aspects, some similar to the current world, while others from a completely different perspective. Here are some of the changes I envision in an ideal world.

Energy Utilisation

We all know that due to climate change, or rather, the climate catastrophe, we have only twelve years to save our Earth. It has occurred to me quite often that one of the main reasons for global warming is the over utilization of resources for energy. Scientists are already working on ways to use solar energy to generate electricity.

In my ideal world order, the world would run using the help of a Dyson sphere. A Dyson sphere is a hypothetical mega structure that completely encompasses a star and captures a large percentage of its power output. In this way, the pollution output rate would fall massively, global warming would decrease, and the world would be a much better place to live in.

World Equality

In my world order, men & women would be considered as equal. Members of the LGBTQ community would be treated as equals. Racism would never be even thought of. There would be no poor and rich difference, but not with communism. No discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, sexual preferences, colour, caste, religion, or opinions would exist.

Every individual would be expected and by social presence adhere to a moral code of conduct, which would include respecting each other, respecting the law, adhering to the law, minding one’s manners in both public & private life. This sort of equality would promote justice and indirectly would improve the law and order situation to its best.

If we could avoid the discrimination, we can avoid the tag of under-developed, developing and developed countries; as each and every country will come upfront to help each other with their requirements in a mutual understanding.

Education System

In my ideal world, there would be little at most to absolutely no resemblance to the current education system. The grading system would be completely abolished. Fishes would be taught to swim as well as they can, monkeys would be taught to climb trees, lions to roar and catch prey, deer to graze and hide from lions.

Elephants would learn to use their trunks to the best of their abilities, squirrels to differentiate between good nuts and bad ones, birds to fly as high as their wings allow, the flightless ones to walk/swim as much as they can. To sum it up, each one would be taught to harbour their own talent and work on that to make it the best they can.

Of course, I don’t mean to say that in an ideal world, we will be educating animals; these animals are simply in reference to differently abled human beings.

Another point under education is that it would be completely free. A school in Assam has begun accepting one small bag of plastic waste as a school fee. The waste collected is then either reused or recycled. Imagine if all the schools and universities used this method!

Our world would be so spotlessly clean, children at a young age would learn how easy it is to reduce wastage and plastic, and parents would not have to go into debts simply to afford good education for their children.

Student debts would also considerably go down, which in my opinion, is an amazing thing. Many students even now are burdened by heavy tuition fee. How nice it would be to unload that burden from their backs!

A Peaceful Existence

In my ideal world order, there would be absolutely no terrorism or war at all. Governments would want only the best for their respective countries – not just to make their nation a superpower, but rather to ensure the welfare of their citizens. All countries would be friendly with each other, with no hostility, disagreements or anger.

Armies would be smaller and digital protection on LoC would be higher. Governments of different countries would be expected to maintain peace, encourage fair & free trade, and cut the beginning of any terrorist seeds at the bud itself.

The world will have deep-rooted respect and pride for the soldiers who sacrifice their personal life to safe-guard the country. A terror free world will also promote tourism and merry amongst the masses who could travel to any part of the country without any fear.

Although people would still be allowed to follow the religion and faith they chose, there would be no fights or trifles among devotees of different religions. Everyone would strictly follow a policy of ‘Live and let Live’.

Addiction Control

Another great hit would be on the addiction forming substances. I would not increase the taxes on alcohol & tobacco products each year, as the government does now to reduce addictions; rather I would completely close down the industries producing these products along with any drug related activities.

This would help a lot many families from getting shattered. Despite of the known health hazards, these addiction forming substances lure the trade industry with their high margin and revenue generation for any country.

My vision is more confined to the general well-being of the human beings with respect to their health, with is undoubtedly much more important than the wealth. In addition, we would form more rehab centres which are verified to help patients overcome addictions and cure themselves.

There are also other ways to get the same feeling as these drugs give, but in a helpful way. Researcher have found several spots in the fore brain, especially in the hypothalamus, which on electrical stimulation, forms a pleasure spot. These stimulation could be given in return for marvellous deeds or for a clean-up drive. This not only motivates people to live their best lives, but also keeps them happier than they could be with drugs.

This is a brief summary of my vision of an ideal world order. The ideal will always be approximate and never exact. However, our vision of an orderly world does not have to remain simply a vision.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

This entry discusses philosophical idealism as a movement chiefly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, although anticipated by certain aspects of seventeenth century philosophy and continuing into the twentieth century. It revises the standard distinction between epistemological idealism, the view that the contents of human knowledge are ineluctably determined by the structure of human thought, and ontological idealism, the view that epistemological idealism delivers truth because reality itself is a form of thought and human thought participates in it, in favor of a distinction earlier suggested by A.C. Ewing, between epistemological and metaphysical arguments for idealism as itself a metaphysical position. After discussing precursors, the entry focuses on the eighteenth-century versions of idealism due to Berkeley, Hume, and Kant, the nineteenth-century movements of German idealism and subsequently British and American idealism, and then concludes with an examination of the attack upon idealism by Moore and Russell and the late defense of idealism by Brand Blanshard.

With the possible exception of the introduction (Section 1), each of the sections below can be read independently and readers are welcome to focus on the section(s) of most interest.

1. Introduction

2. idealism in early modern rationalism, 3. idealism in early modern british philosophy, 5. german idealism, 6. schopenhauer, 7. nietzsche (and a glimpse beyond), 8. british and american idealism, 9. the fate of idealism in the twentieth century, primary literature, selected secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

The terms “idealism” and “idealist” are by no means used only within philosophy; they are used in many everyday contexts as well. Optimists who believe that, in the long run, good will prevail are often called “idealists”. This is not because such people are thought to be devoted to a philosophical doctrine but because of their outlook on life generally; indeed, they may even be pitied, or perhaps envied, for displaying a naïve worldview and not being philosophically critical at all. Even within philosophy, the terms “idealism” and “idealist” are used in different ways, which often makes their meaning dependent on the context. However, independently of context one can distinguish between a descriptive (or classificatory) use of these terms and a polemical one, although sometimes these different uses occur together. Their descriptive use is best documented by paying attention to the large number of different “idealisms” that appear in philosophical textbooks and encyclopedias, ranging from metaphysical idealism through epistemological and aesthetic to moral or ethical idealism. Within these idealisms one can find further distinctions, such as those between subjective, objective and absolute idealism, and even more obscure characterizations such as speculative idealism and transcendental idealism. It is also remarkable that the term “idealism”, at least within philosophy, is often used in such a way that it gets its meaning through what is taken to be its opposite: as the meaningful use of the term “outside” depends on a contrast with something considered to be inside, so the meaning of the term “idealism” is often fixed by what is taken to be its opposite. Thus, an idealist is someone who is not a realist, not a materialist, not a dogmatist, not an empiricist, and so on. Given the fact that many also want to distinguish between realism, materialism, dogmatism, and empiricism, it is obvious that thinking of the meaning of “idealism” as determined by what it is meant to be opposed to leads to further complexity and gives rise to the impression that underlying such characterizations lies some polemical intent.

Within modern philosophy there are sometimes taken to be two fundamental conceptions of idealism:

- something mental (the mind, spirit, reason, will) is the ultimate foundation of all reality, or even exhaustive of reality, and

- although the existence of something independent of the mind is conceded, everything that we can know about this mind-independent “reality” is held to be so permeated by the creative, formative, or constructive activities of the mind (of some kind or other) that all claims to knowledge must be considered, in some sense, to be a form of self-knowledge.

Idealism in sense (1) has been called “metaphysical” or “ontological idealism”, while idealism in sense (2) has been called “formal” or “epistemological idealism”. The modern paradigm of idealism in sense (1) might be considered to be George Berkeley’s “immaterialism”, according to which all that exists are ideas and the minds, less than divine or divine, that have them. (Berkeley himself did not use the term “idealism”.) The fountainhead for idealism in sense (2) might be the position that Immanuel Kant asserted (if not clearly in the first edition of his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) then in his Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics (1783) and in the “Refutation of Idealism” in the second edition of the Critique ) according to which idealism does “not concern the existence of things”, but asserts only that our “modes of representation” of them, above all space and time, are not “determinations that belong to things in themselves” but features of our own minds. Kant called his position “transcendental” and “critical” idealism, and it has also been called “formal” idealism. However, Kant’s position does not provide a clear model of idealism at all. While Kant himself claimed that his position combined “empirical realism” with “transcendental idealism”, that is, combined realism about external, spatio-temporal objects in ordinary life and science with the denial of the reality of space and time at the level of things as they are in themselves, it also insisted upon the reality of things as they are in themselves existing independently from our representations of them, thus denying their reducibility to representations or the minds that have them. In this way, Kant’s position actually combines the transcendental ideality of space and time with a kind of realism about the existence of things other than minds.

So instead of using Kant as any kind of model for epistemological idealism, in this entry we will distinguish between metaphysical and epistemological arguments for idealism understood as a metaphysical doctrine, namely that everything that exists is in some way mental. We thus agree with A.C. Ewing, who wrote in 1934 that all forms of idealism

have in common the view that there can be no physical objects existing apart from some experience, and this might perhaps be taken as the definition of idealism, provided that we regard thinking as part of experience and do not imply by “experience” passivity, and provided we include under experience not only human experience but the so-called “Absolute Experience” or the experience of a God such as Berkeley postulates. (Ewing 1934: 3)

in other words, while reducing all reality to some kind of perception is one form of idealism, it is not the only form—reality may be reduced to the mental on other conceptions of the latter. Thus Willem deVries’s more recent definition of idealism as the general theory that reduces reality to some form or other of the mental is just:

Roughly, the genus comprises theories that attribute ontological priority to the mental, especially the conceptual or ideational, over the non-mental. (deVries 2009: 211)

We also agree with Jeremy Dunham, Iain Hamilton Grant, and Sean Watson when they write that

the idealist, rather than being anti-realist, is in fact … a realist concerning elements more usually dismissed from reality. (Dunham, Grant, & Watson 2011: 4)

namely mind of some kind or other: the idealist denies the mind-independent reality of matter, but hardly denies the reality of mind (or, on their account, which goes back to Plato, Ideas or Forms as well as minds; we will not consider pre-modern forms of idealism in any detail). However, following Ewing (see his chapters II, IV–V, and VIII), we will distinguish metaphysical from epistemological arguments for idealism. Metaphysical arguments proceed by identifying some general constraints on existence and arguing that only minds of some sort or other satisfy such conditions; epistemological arguments work by identifying some conditions for knowledge and arguing that only objects that are in some sense or other mental can satisfy the conditions for being known. In particular, epistemological arguments for idealism assume that there is a necessary isomorphism between knowledge and its object that can obtain only if the object of knowledge is itself mental; we propose that this is the difference between epistemologically-motivated idealism and a more neutral position, which might be identified with philosophers such as Rudolf Carnap, W.V.O. Quine, and Donald Davidson, holding that of course we always know things from some point of view, but any “external” question about whether or not our point of view “corresponds” to independent reality is either meaningless or at least not answerable on theoretical grounds. It is in order to preserve the distinction between traditional idealism and positions such as the latter that we recommend retaining the claim that reality is in some way or other exclusively mental and thinking of epistemological arguments for idealism rather than epistemological idealism as such.

Of course these strategies can be combined by a single philosopher. Berkeley does so, and so does Kant in arguing for the transcendental idealist part of his complex position. Others separate them, for example F.H. Bradley and J.McT.E. McTaggart constructed metaphysical arguments for idealism, while Josiah Royce and Brand Blanshard offered epistemological arguments.

In what follows, we will concentrate mainly on the discussion of philosophical theories that either endorse or claim to endorse idealism on ontological and/or epistemological grounds. At some points in its complex history, however, above all in the social as well as philosophical movement that dominated British and American universities in the second half of the nineteenth century and through the first World War, idealism in either of its philosophical forms was indeed connected to idealism in the popular sense of progressive and optimistic social thought. This was true for figures such as Bradley and Royce and their predecessors and contemporaries such as Thomas Hill Green and Bernard Bosanquet. There has recently been considerable interest in British or more generally Anglophone idealism as a movement in social philosophy, or even a social movement, but we will not pursue that here (see Mander 2011; Boucher & Vincent 2012; Mander [ed.] 2000; and Mander & Panagakou [eds.] 2016).

Our distinctions between epistemological and ontological idealism, on the one hand, and that between metaphysical and epistemological arguments for idealism, on the other hand, has not always been clearly made. However, the American philosopher Josiah Royce pointed in the direction of our distinction at the end of the nineteenth century. On Royce’s definitions, epistemological idealism

involves a theory of the nature of our human knowledge ; and various decidedly different theories are called by this name in view of one common feature, namely, the stress that they lay upon the “subjectivity” of a larger or smaller portion of what pretends to be our knowledge of things. (1892: xii–xiii)

Metaphysical idealism, he says, “is a theory as to the nature of the real world , however we may come to know that nature” (1892: xiii), namely, as he says quoting from another philosopher of the time,

the “belief in a spiritual principle at the basis of the world, without the reduction of the physical world to a mere illusion”. (1892: xiii; quoting Falckenberg 1886: 476).

But Royce then argued that epistemological idealism ultimately entails a foundation of metaphysical idealism, in particular that “the question as to how we ‘transcend’ the ‘subjective’ in our knowledge”, that is, the purely individual, although it exists for both metaphysical realists and idealists, can only be answered by metaphysical idealists (1892: xiv). We will argue similarly that while epistemology can entail idealism, on the assumption that the isomorphism between knowledge and the known must be in some sense necessary and that this can be so only if the known as well as knowledge is in some sense mental, this should be distinguished from the more general and extremely widespread view that our knowledge is always formed within our own point of view, conceptual framework, or web of belief. This view may well be the default position of much twentieth-century philosophy, “continental” as well as “analytic”, but does not by itself entail that reality is essentially mental.

Our distinction between epistemological and metaphysical arguments for idealism can also be associated with a distinction between two major kinds of motives for idealism: those which are grounded in self-conceptions, i.e., in convictions about the role that the self or the human being plays in the world, and those based on what might correspondingly be called world-convictions, i.e., on conceptions about the way the world is constituted objectively or at least appears to be constituted to a human subject. Concerning motives based on self-conceptions of human beings, idealism has seemed hard to avoid by many who have taken freedom in one of its many guises (freedom of choice, freedom of the will, freedom as autonomy) to be an integral part of any conception of the self worth pursuing, because the belief in the reality of freedom often goes together with a commitment to some version of mental causation, and it is tempting to think that the easiest (or at least the most economical) way to account for mental causation consists in “mentalizing” or idealizing all of reality, thus leading to ontological idealism, or at least to maintain that the kind of causal determinism that seems to conflict with freedom is only one of our ways of representing the world, thus leading to epistemological idealism. Motives for idealism based on world-convictions can be found in many different attitudes towards objectivity. If one is to believe in science as the best and only way to get an objective (subject-independent) conception of reality, one might still turn to idealism, at least epistemological idealism, because of the conditions supposed to be necessary in order to make sense of the very concept of a law (of nature) or of the normativity of logical inferences for nature itself. If one believes in the non-conventional reality of normative facts one might also be drawn to idealism in order to account for their non-physical reality—Plato’s idealism, which asserts the reality of non-physical Ideas to explain the status of norms and then reduces all other reality to mere simulacra of the former might be considered a forerunner of ontological idealism motivated by concern for the reality of norms. An inclination toward idealism might even arise from considerations pertaining to the ontological status of aesthetic values (is beauty an objective attribute of objects?) or from the inability or the unwillingness to think of the constitution of social and cultural phenomena like society or religion in terms of physical theory. In short: There are about as many motives and reasons for endorsing idealism as there are different aspects of reality to be known or explained.

Although we have just referred to Plato, the term “idealism” became the name for a whole family of positions in philosophy only in the course of the eighteenth century. Even then, those whom critics called “idealists” did not identify themselves as such until the time of Kant, and no sooner did the label come into use than did those to whom it was applied or who used it themselves attempt to escape it or refine it. As already mentioned, Berkeley, the paradigmatic idealist in the British tradition, did not use the name for his own position, which he called rather immaterialism; and Leibniz, at least some versions of whose monadology might be considered idealist, also did not call his position by that name. Rather, in contrasting Epicurus with Plato, Leibniz called the latter an idealist and the former a materialist, because according to him idealists like Plato hold that “everything occurs in the soul as if there were no body” whereas on the materialism of Epicurus “everything occurs in the body as if there were no soul” (“Reply to the Thoughts on the System of Pre-established Harmony contained in the Second Edition of Mr. Bayle’s Critical Dictionary, Article Rorarius”, 1702, PPL : 578), although in this text Leibniz also says that his own view combines both of these positions. It seems to have been Christian Wolff who first used “idealism” explicitly as a classificatory term. Wolff, often considered the most dedicated Leibnizian of his time (although in fact his position was more eclectic than at least some versions of Leibniz’s) set out to integrate the terms “idealism” and “materialism” into his taxonomy of philosophical attitudes of those “who strive towards the knowledge and philosophy of things” in the Preface to the other [second] Edition of his so-called German Metaphysics [ Vernünfftige Gedancken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt, den Liebhabern der Wahrheit mitgetheilet (Halle: Carl Hermann Hemmerde, 1747)]. Wolff distinguishes between two basic attitudes, one of which he sees exemplified by the skeptic, the other by what he calls “the dogmatist”. The skeptic doubts the possibility of knowledge in general and thus refuses to defend any positive claim at all. By contrast, the dogmatist puts forward positive doctrines, and these can be divided into those which posit as fundamental either one single kind of entities [ Art der Dinge ] or two different kinds. Wolff names the supporters of the first position “monists” and the adherents of the second “dualists”. This amounts to the division of all dogmatic doctrines, i.e., all knowledge-claims with respect to the ultimate constitution of reality, into monistic and dualistic theories. Here is where the term “idealist” then makes its appearance in Wolff’s typology: he distinguishes within the monists between idealists and materialists. Idealists “concede only spirits or else those things that do not consist of matter”, whereas materialists “do not accept anything in philosophy other than the corporeal and take spirits and souls to be a corporeal force”. Dualists, on the contrary, are happy “to accept both bodies and spirits as real and mutually independent things”. Wolff then goes on to distinguish within idealism between “egoism” and “pluralism”, depending on whether an idealist thinks just of himself as a real entity or whether he will allow for more than one (spiritual) entity; the first of these positions would also come to be called solipsism, so that solipsism would be a variety of (ontological) idealism but not all idealism would be solipsism.

Wolff’s way of classifying a philosophical system was enormously influential in eighteenth-century Continental philosophy—for example, it was closely followed by Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten in his 1739 Metaphysica , which was in turn used by Kant as the textbook for his metaphysics (and anthropology) lectures throughout his career, and whose definition of dogmatic idealism, as contrasted to his own “transcendental” or “critical” idealism, would also be that it is the position according to which there are only minds—and so it is no surprise that almost all talk about idealism was heavily influenced by Wolff’s characterization. This is so because it reflects the main metaphysical disputes in seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century philosophy on the Continent quite well. In terms of Wolff’s distinctions, these disputes can be framed as disputes between (a) monists and dualists and (b) idealists and materialists; positions in this debate were often influenced by perplexities surrounding the (ontological) question of the interaction of substances, although they were also influenced by the (epistemological) debate over innatism. Although neither dualism, whose main representative was Descartes (who asserted the existence of both res cogitans and res extensa ), nor monism, allegedly though debatably represented by Spinoza in its materialistic version ( substantia, deus, natura ) and by Leibniz in its idealistic form (monad, entelechy, simple substance) succeeded in finding satisfying answers to this and related questions, in the early modern era these disputes shaped the conception of what the object of metaphysics ( metaphysica generalis sive ontologia ) was supposed to be.

Prior to Wolff, neither defending nor refuting idealism seems to have been a central issue for rationalist philosophers, and none of them called themselves idealists. Yet what are by later lights idealistic tendencies can nevertheless be found among them.

While Descartes’s “first philosophy” clearly defends dualism, he takes his target to be skepticism rather than idealism, and thus is from our point of view concerned to resist the adoption of epistemological grounds; Spinoza is often though controversially thought to defend a form of materialism, but takes his primary target to be pluralism as contrasted to monism; and Leibniz does not seem overly worried about choosing between idealist and dualist forms of his “monadology”, while his famous thesis that each monad represents the entire universe from its own point of view might be taken to be a form of epistemological ground for idealism, but Leibniz does not seem to conceive of it as such. Nicolas Malebranche’s theory of “seeing all things in God” might be the closest we find to an explicit assertion in seventeenth-century philosophy of an argument for idealism on both epistemological and ontological grounds, and thus as a forerunner of the “absolute” idealism of the nineteenth century. While from a later point of view it may seem surprising that these rationalists were not more concerned with explicitly asserting or refuting one or both versions of idealism, perhaps they were more concerned with theological puzzles about the nature and essence of God, metaphysical questions as to how to reconcile the respective conception of God with views about the interaction of substances of fundamentally different kinds, and epistemological problems as to the possibility of knowledge and cognitive certainty than they were worried about whether the ultimate constituents of reality were mental or material elements.

However, if one were to situate their thoughts within the framework provided by Wolff it is not that difficult to find traces of idealism derived from both ontological and epistemological grounds in their respective positions. With respect to their metaphysical or ontological teachings, this claim may seem surprising. Whereas according to Wolff idealists are representatives of a species of metaphysical monism Descartes is one of the most outspoken metaphysical dualists. Hence to impute idealistic tendencies to Descartes’ metaphysics looks like a mistake. And in the case of Spinoza one could argue that although he definitely is a (very radical) monist and thus could count as an idealist within Wolff’s taxonomy, he is traditionally considered to be rather a materialist in Wolff’s sense. Consequently, it appears as if already for conceptual reasons there is no basis to burden either Descartes or Spinoza with idealism as defined by Wolff. Leibniz, meanwhile, often seems unwilling to commit himself to idealism even though that is the most natural interpretation of his monadology, while only Malebranche, as noted, seems to come close to explicitly asserting epistemological and perhaps ontological arguments for idealism as well.

Nevertheless, both Descartes and Spinoza provide a starting point for their metaphysical doctrines with their conceptions of God, a starting point that is already infected with idealistic elements if idealism is understood as implying a commitment to the primacy or at least the unavoidability and irreducibility of mental items in the constitution and order of things in general. Both agree that in order to gain insight into the constitution of the world one has to find out what God wants us, or maybe better: allows us to know about it (see, e.g., Descartes: Meditations IV , 7–8 and especially 13; Spinoza: Ethics I , XVI). They also agree that the world is created by God although they have different views as to what this means. Whereas Descartes thinks of God as existing outside the world of the existing things He created (see Meditations III , 13 and 22) Spinoza holds that whatever exists is just a peculiar way in which God is present (see Ethics I , XXV, Corollary). Of all existing things all that God permits us to know clearly and distinctly is (again according to both Descartes and Spinoza) that their nature consists either in thinking or in extension. This claim can be seen as providing in the case of Descartes the basis for his justification of ontological dualism. His distinction between extended and thinking substances is not just meant to give rise to a complete classification of all existing things in virtue of their main attributes but also to highlight the irreducibility of mental (thinking) substances to physical or corporeal (extended) substances because of differences between their intrinsic natures (see, e.g., Meditations VI , 19, and Principles of Philosophy I , 51–54). In the case of Spinoza thinking and extension not only refer to attributes of individual things but primarily to attributes of God (see Ethics II , Proposition I, II, and VII, Scholium), making them the fundamental ways in which God himself expresses his nature in each individual thing. This move gives rise to his ontological monism because he can claim that all individual things are just modes in which God’s presence is expressed according to these attributes.

Although the idea that God is the creator of the world of individual existing things (Descartes) or that God himself is manifested in every individual existing thing (Spinoza) might already be considered to be sufficient as a motivating force for subsequent disputes as to the true nature of reality and thus might have given rise to what were then called “idealistic” positions in ontology, other peculiarities within Descartes’ and Spinoza’s position might well have led to the same result, i.e., to the adoption of idealism on ontological grounds. Especially their disagreement about God’s corporeality might have been such a motive. Whereas Descartes vigorously denies the corporeality of God ( Principles of Philosophy I , 23) and hence could be seen as endorsing idealism, Spinoza vehemently insists on God’s corporeality ( Ethics I , Proposition XV, Scholium) and thus could be taken to be in favor of materialism.

Things are different when it comes to epistemological grounds for idealism. It seems to be very difficult to connect Descartes’ and Spinoza’s views concerning knowledge with conceptions according to which knowledge has something to do with a cognizing subject actively contributing to the constitution of the object of knowledge. This is so because both Descartes and Spinoza think of cognition as a result of a process in which we become aware of what really is the case independently of us both with respect to the nature of objects and with respect to their conceptual and material relations. Descartes and Spinoza take cognition to be a process of grasping clear and distinct ideas of what is the true character of existing things rather than a process of contributing to the formation of their nature. According to Descartes the sources of our knowledge of things are our abilities to have intuitions of the simple nature of things and to draw conclusions from these intuitions via deduction ( Rules for the Direction of the Mind III, 4 ff.). For him the cognitive procedure is a process of discovery (see Discourse on the Method , Part 6, 6) of what already is out there as the real nature of things created by God by finding out the clear and distinct ideas we can have of them ( Discourse , Part 4, 3 and 7). In a similar vein Spinoza thinks of knowledge as an activity that in its highest form as intuitive (or third genus of) cognition leads to an adequate insight into the essence of things ( Ethics II , Proposition XL, Scholium II, and Ethics V , Propositions XXV–XXVIII), an insight that gives rise to general concepts ( notiones communes ) on which ratiocinationes , i.e., the processes of inference and deduction, are based ( Ethics II , Proposition XL, Scholium I) the results of which provide the second genus of cognition ( ratio ). Thus the problem for both Descartes and Spinoza is not so much that of the epistemologically motivated idealist, i.e., to uncover what we contribute through our cognitive faculties to our conception of an object, rather their problem is to determine how it comes that we very often have a distorted view of what there is and are accordingly led to misguided beliefs and errors. Given what they take to be a basic fact that God has endowed us with the capacity to know the truth (albeit within certain limits), i.e., to know to a certain degree how or what things really are, this interest in the possibility of error makes perfectly good sense ( Meditations IV , 3–17; Principles of Philosophy I , 70–72; Ethics II , Proposition 49, Scholium).

In his project for a “universal characteristic”, Leibniz can be regarded as having taken great interest in a method for inquiry, but he does not seem to have taken much interest in the epistemological issue of skepticism or the possibility of knowledge, and thus did not explicitly characterize his famous “monadology” as a form of an epistemological ground for idealism. But he did take a great interest in the ontology of substances, God the infinite substance and everything else as finite substances (in contrast to Spinoza, he rejected monism). Yet while the logic of his monadology clearly points toward idealism, Leibniz frequently attempted to avoid this conclusion. One explicitly ontological argument for the monadology that Leibniz often deploys is that, on pain of infinite regress, everything composite must ultimately consist of simples, but that since space and time are infinitely divisible extended matter cannot be simple while thoughts, even with complex content, do not literally have parts, nor do the minds that have them, so minds, or monads, are the only candidates for the ultimate constituents of reality. Thus the late text entitled “The Monadology” begins with the assertions that

The monad which we are here to discuss is nothing but a simple substance which enters into compounds,

There must be simple substances, since there are compounds, [and] the compounded is but a collection or an aggregate of simples,

where there are no parts, it is impossible to have either extension, or figure, or divisibility

and conversely where there is simplicity there cannot be extension or figure or divisibility (§§1–3). Yet monads must have some qualities in order to exist (§8) and to differ from one another, as they must (§9), and if the fundamental properties of matter are excluded, this leaves the fundamental properties of mind, which Leibniz holds to be perception, “The passing state which enfolds and represents a multitude in unity” (§14) and appetition, “the internal principle which brings about change or the passage from one perception to another” (§15; all from PPL : 643–4). This argument clearly seems to imply that all finite substances are ultimately mental in nature (and the infinite substance, God, is obviously mental in nature), thus it seems to be a paradigmatic ontological argument for idealism, from which an epistemological argument for idealism would automatically follow, since if there is knowledge of reality at all, which Leibniz hardly seems to doubt, and reality is ultimately mental, then knowledge too must be of the mental.

Yet Leibniz often seems to avert such a conclusion by appeal to his idea of “pre-established harmony”, and this is possible because he himself interprets this idea in two different ways. Early in his career, in such texts as “Primary Truths” (1680–84) and the “Discourse on Metaphysics” (1686) (both texts unpublished in Leibniz’s lifetime and not known to his immediate successors such as Wolff and Baumgarten), Leibniz introduces the doctrine of pre-established harmony on truth-theoretical grounds. His argument is that everything that is true of a substance is so because the predicate of a true proposition is contained in the complete concept of its subject and because that complete concept reflects the properties or “traces” in the substance that is that subject; that there are true propositions linking every substance in the world to every other, thus the complete concept of each substance must be a complete concept of the universe itself and each substance must bear within itself as properties traces of every other in the universe; and thus that each substance must reflect, or, as mental, represent the entire universe. Yet since (finite) substances are also defined as existing independently of one another (although not existing independently from the infinite substance, God), there is a question as to why each should truthfully represent all the others, which Leibniz answers by appeal to the idea of a pre-established harmony: although considered from the point of view of the concept of substance it does not seem necessary that every substance truly represent all the others, in his goodness, thus in his preference for a maximally harmonious world, God has nevertheless made it such that they do.

In this mood, Leibniz tends to explain the existence of body as an artifact of the fact that each monad represents the world from its own point of view: physical locations and the bodies that occupy them are just the way in which the difference in the points of view of the monads is represented by them, but have no deeper reality; or, as Leibniz often says, space, spatiality, and bodies are just phenomena bene fundata , i.e., “well-founded modes of our consideration” ( PPL : 270).

However, sometimes Leibniz writes as if space and time are not merely the way in which the pre-established harmony among monads presents itself to (their) consciousness, but as if the mental and physical or extended are two separate realms, each evolving entirely in accordance with its own laws, but with a pre-established harmony between them creating the appearance of interaction. Perhaps Leibniz was genuinely undecided between two interpretations of the pre-established harmony and two conceptions of the reality of body, sometimes being a committed idealism and sometimes a dualist. (As we will see later, even among the most committed absolute idealists of the nineteenth century it is not always clear whether they are actually denying the existence of matter or only subordinating it to mind in one way or another).

Leibniz’s monadology could thus be seen as a forerunner of both epistemological and ontological arguments for idealism, and his conception of space and time as phenomena bene fundata was clearly a forerunner of Kant’s transcendental idealism. But as we have just seen, he did not himself unequivocally affirm idealism, and as we will shortly see subsequent Leibnizians such as Alexander Baumgarten argued for dualism and for a corresponding interpretation of pre-established harmony. Nicolas Malebranche was also a dualist, committed to the existence of both mind and body, and an occasionalist, who held that since causation is necessary connection and the only truly necessary connection is between God’s intentions and their effects, bodies cannot directly cause modifications of minds (or each other) but rather there can be a causal relation between body and mind only if God intends the mind to undergo a certain modification upon the occasion of a certain change in a body (hence the term “occasionalism”). This is a metaphysical argument. His further doctrine that the mind sees all things in God, however, can be seen as an epistemological argument, for it depends on his particular view of what modifications the mind undergoes in perception. He holds that sensations are literally modifications in the mind, but that they are highly indeterminate, or in later terminology lack determinate intentional objects, and that genuine understanding occurs only when and to the extent that the determinate ideas in the perfect intellect of God are disclosed to finite, human minds, to the extent that they are. Malebranche’s position can be considered a theological form of Platonism: Plato held that the true Ideas or Forms of things have a kind of perfection that neither ordinary objects nor representations of them in human minds do, and therefore must exist someplace else; Malebranche takes the obvious further step of supposing that perfect ideas can exist only in the perfect intellect of God. He then supposes that human thought is intelligible to the extent that these ideas are disclosed to it, on the occasion of various sensations themselves occasioned by God but not literally through those sensations. The crucial point is that genuine understanding consists in the apprehension of ideas, even though these are literally in the mind of God rather than of individual human beings, rather than of physical objects, even though the latter do exist. Malebranche had significant influence on both Berkeley and Hume, although neither the former and certainly not the latter accepted his position in its entirety. His position that knowledge consists in individual minds apprehending ideas in some greater mind would also be recreated by idealists as late as T.H. Green and Josiah Royce in the second half of the nineteenth century, as we will later see.

Before we turn to British or Anglophone versions of idealism, earlier or later, one last word about idealism within pre-Kantian rationalist philosophy is in order. As earlier mentioned, dualism rather than idealism became the default position of the German successors to Leibniz, the so-called “Leibnizo-Wolffians” who dominated the teaching of philosophy in many German universities for fifty years from the third decade of the eighteenth century until the time of Kant and in some cases even beyond, and they correspondingly opted for the interpretation of the pre-established harmony as a relation between minds and bodies rather than among minds or monads alone. It may also be noted that defending dualism by means of an explicit “refutation of idealism” became the norm among these philosophers. This may be seen in Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten’s Metaphysica of 1739, which would become Kant’s textbook for his lecture courses in metaphysics and “anthropology” (empirical psychology) until the very end of the eighteenth century. Baumgarten accepts that the ultimate constituents of the world must be simples, hence monads of some kind. But he does not suppose that monads are necessarily minds or intellects, hence a dualism of monads is at least possible. Idealism would be the position that there are only intellectual monads; he says that

An intellectual substance, i.e., a substance endowed with intellect, is a spirit (an intelligence, a person)…. Whoever admits only spirits in this world is an idealist. ( Metaphysics , §402, pp. 175–6)

Baumgarten follows Wolff in distinguishing between two possible forms of idealism, first egoism, which admits the existence of only one spirit, that of the person contemplating such a doctrine, and then idealism proper, which allows the existence of multiple spirits. But both are refuted by the same argument. This argument builds on a Leibnizian principle not hitherto mentioned, the principle of plenitude, or the principle that the perfection of the most perfect world, which is the one that God created, consists in the maximal variety of the universe compatible with its unity or coherence (e.g., “Monadology”, §58, PPL : 648), which was in turn the basis of one of Leibniz’s arguments for the identity of indiscernibles. Baumgarten then argues simply that a universe that contains not only more substances but also more kinds of substances rather than fewer is a more perfect universe, and necessarily exists in preference to the other; and a universe that contains not only multiple minds rather than a single mind but also bodies in addition to minds is therefore a more perfect universe than either of the former would be, and is therefore the kind of world that actually exists. In his words,

the egotistical world, such as an egoist posits, is not the most perfect. And even if there is only one non-intellectual monad possible in itself that is compossible with spirits in the world, whose perfection either subtracts nothing from the perfection of the spirits, or does not subtract from the perfection of the spirits so much as it adds to the perfection of the whole, then the idealistic world, such as is posited by the idealist, is not the most perfect, ( Metaphysics , §438, [2013: 183])

and hence not the kind of world that exists. No one outside of the immediate sphere of Leibnizianism would ever again proffer such a refutation of idealism. But both Baumgarten’s recognition of idealism and his refutation of it in a university textbook make it clear that by the middle of the eighteenth century idealism had become a standard topic for philosophical discussion, a position it would retain for another century and a half or more.

The relation between ontological and epistemological arguments for idealism is complex. Idealism can be argued for on ontological grounds, and then bring an epistemological argument in its train. Or an epistemological argument can be offered independently of ontological assumptions but lead to idealism, especially in the hope of avoiding skepticism. The first option may have been characteristic of some rationalists, such as Leibniz in his more strictly idealist mood. Both forms of argument are found within early modern British philosophy. We find epistemological considerations pushing toward idealism in both Hobbes and Locke in spite of the avowed materialism of the first and dualism of the second, who therefore obviously did not call themselves idealists. Berkeley argues for idealism on epistemological grounds and then adds ontological considerations in order to avert skepticism, although he calls his position immaterialism rather than idealism. Berkeley’s contemporary Arthur Collier, who explicitly denies the existence of mind-independent matter without giving his own position a name, argues first in an epistemological mood, then moves from epistemology to ontology. Hume, by contrast, although calling himself neither an immaterialist nor an idealist, nevertheless adopts epistemological arguments for idealism similar to some of Berkeley’s, but then uses that position as the basis for a critique of traditional metaphysical pretensions, including those to idealism—while also being drawn to idealism in resistance to what he regards as the natural tendency to dualism. Hume’s critical attitude toward metaphysics is subsequently taken up by Kant, although Kant famously asserts on practical grounds some of the very same metaphysical theses that he argues cannot be asserted on theoretical grounds.

The British philosophers were all hostile toward dogmatic metaphysics in Wolff’s sense, although until the time of Hume, who had some familiarity with Leibniz, the metaphysics with which they were familiar were those of Descartes, Aristotelian scholasticism, and Neo-Platonism, which had become domesticated in Britain through the work of the Cambridge Platonists in the second half of the seventeenth century. All of these movements fed into the general movement of rationalism, while the British philosophers, typically lumped together under the rubric of empiricism in spite of their own differences, all believed, albeit for different reasons, that the doctrines put forward by dogmatic metaphysicians rest on a totally unfounded conception of knowledge and cannot survive rational scrutiny (empiricists might themselves be considered critical rationalists). Thus the primary task of philosophy for these philosophers became that of providing a theory of knowledge based on an adequate assessment of the constitution of human nature, for they were interested in knowledge only as a human achievement. However, it is not human nature in general that is of interest in this context but the workings of those human powers or faculties that are responsible for our human ability to relate to the world in terms of knowledge-claims. (Thus Kant’s attempt to argue on practical grounds for metaphysical theses that could not be justified on theoretical grounds would be a major departure from the methods of the British empiricists.) These faculties were attributed by the British as well as their Continental opponents to what was called “spirit” or “mind” ( mens , consciousness, Bewußtsein ), an attribution which resulted in moving the “operations of the mind” into the center of philosophical attention. Reflections on the conditions of the possibility of knowledge led Hobbes and Locke to idealism in spite of their ontological commitments to materialism or dualism respectively, while Berkeley concluded that their epistemology would lead to a skepticism that could be avoided only by his own more radical “immaterialist” ontology. Hume’s position remains complex and for this reason controversial. His thesis that our beliefs in causation, external objects, and even the self are all founded on “custom” and imagination rather than “reason” may be considered an epistemological position without ontological implications, thus not an argument for idealism; but while he sometimes seems to attempt to avoid commitment on ontological questions altogether, at other times, as in his argument that the existence of external objects in addition to our impressions is only a fiction, he seems to infer idealism from his epistemology. In spite of their differences, almost all British philosophers from Hobbes up to and including Hume insisted that the highest priority for philosophy is to give an analysis of the conditions and the origin of knowledge, while they gave not only somewhat different accounts of what these conditions consist in and how they contribute to a convincing story about the origin of knowledge but they also had to face quite interesting “metaphysical” consequences from their respective accounts.

This is easily confirmed by looking briefly at some of their main convictions concerning knowledge, starting with Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679). As Hobbes points out in the chapters Of Philosophy and Of Method in the first part ( Computation or Logic ) of the first section ( Concerning Body ) of his Elements of Philosophy (1655), knowledge is the result of the manipulation of sensory input based on the employment of logical rules of reasoning (ratiocination) in acts of what he calls “computation”. He describes the details of this process most succinctly in a short passage in chapter 6 of the first part ( Human Nature ) of his The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (1640), his first major philosophical work. After distinguishing what he calls “sense, or knowledge original” from “knowledge … which we call science”, he goes on to “define” knowledge “to be evidence of truth, from some beginning or principle of sense” and formulates four principles that are constitutive of knowledge:

The first principle of knowledge therefore is that we have such and such conceptions; the second, that we have thus and thus named the things whereof they are conceptions; the third is, that we have joined those names in such manner, as to make true propositions; the fourth and last is, that we have joined those propositions in such manner as they be concluding. (1640: I.6.4)

The message is straightforward with respect to both the basis and the formation of knowledge: senses (sensations) are basic to our acquisition of knowledge in that they lead to conceptions (representations) to which we attach names (concepts) which we then put together into propositions which, if true, already constitute knowledge, and from which there arise further knowledge if we draw conclusions in an orderly way from them.