- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream' speech in its entirety

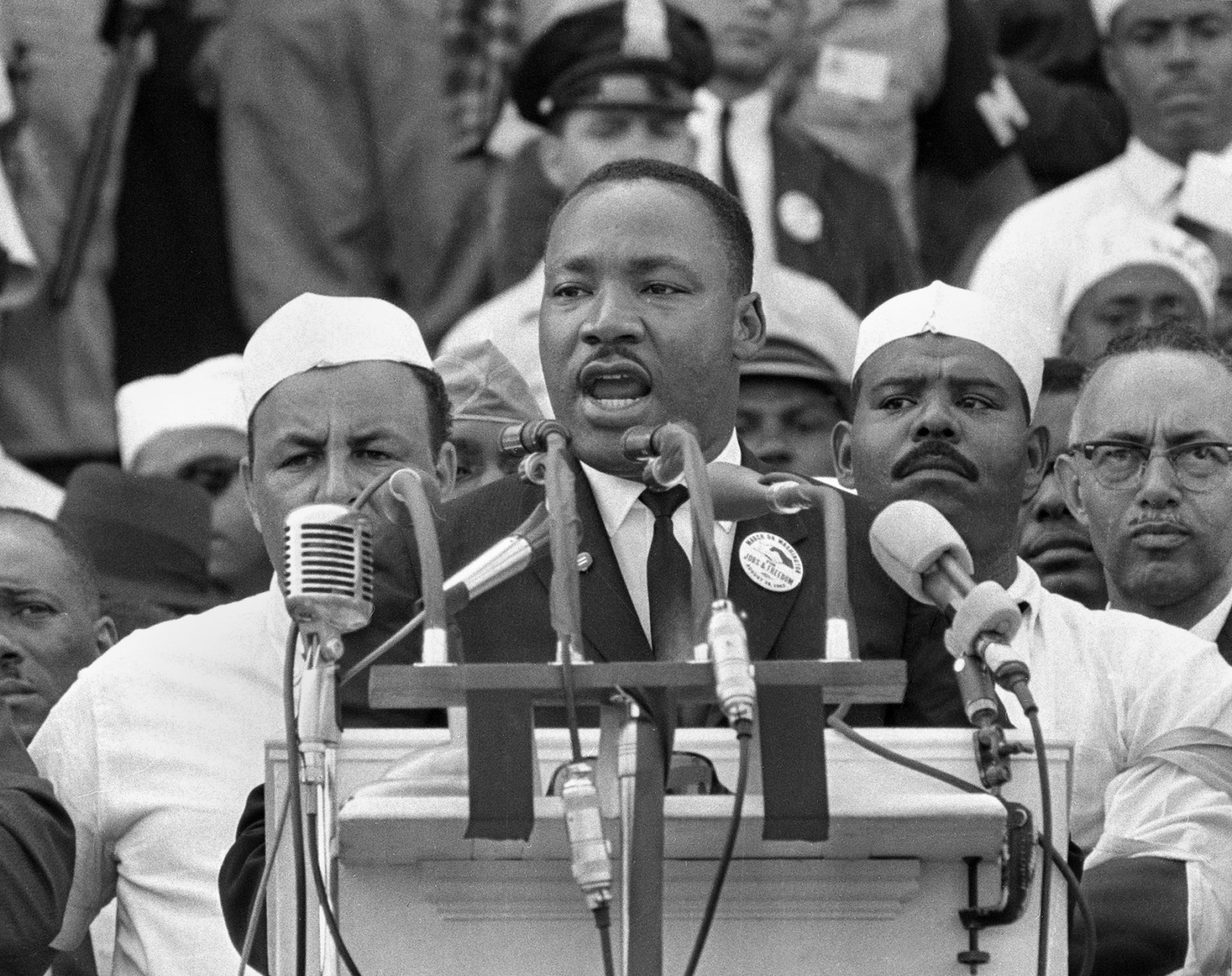

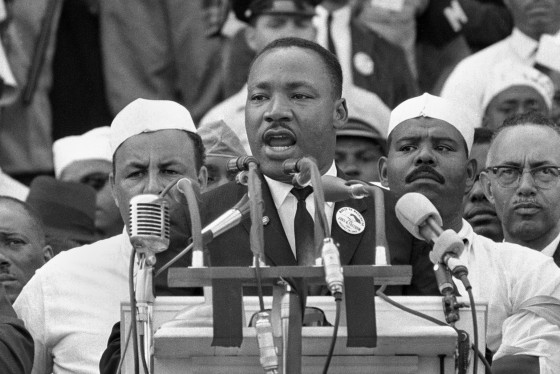

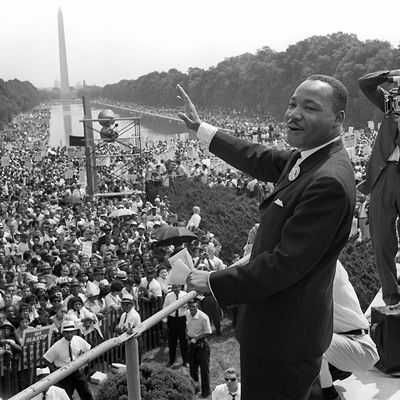

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington.

Monday marks Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Below is a transcript of his celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. NPR's Talk of the Nation aired the speech in 2010 — listen to that broadcast at the audio link above.

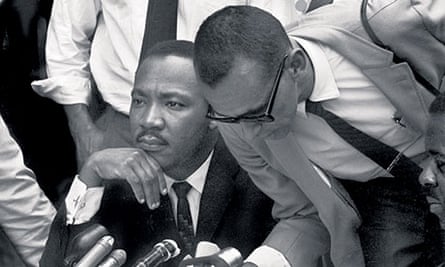

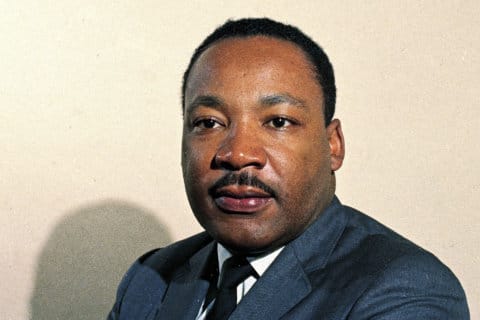

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders gather before a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington. National Archives/Hulton Archive via Getty Images hide caption

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.: Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check.

Code Switch

The power of martin luther king jr.'s anger.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

Martin Luther King is not your mascot

We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we've come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

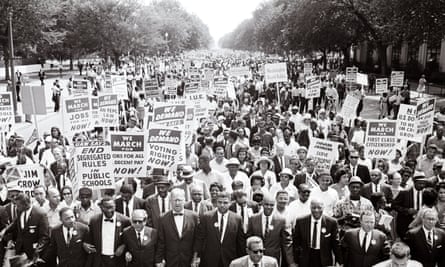

Civil rights protesters march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Kurt Severin/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

Throughline

Bayard rustin: the man behind the march on washington (2021).

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.

And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

How The Voting Rights Act Came To Be And How It's Changed

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

People clap and sing along to a freedom song between speeches at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Express Newspapers via Getty Images hide caption

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

Nikole Hannah-Jones on the power of collective memory

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

Correction Jan. 15, 2024

A previous version of this transcript included the line, "We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now." The correct wording is "We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now."

I Have a Dream Speech Transcript – Martin Luther King Jr.

One of the most iconic and famous speeches of all time, Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech was delivered during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. Read the full transcript of this classic speech.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 00:59 ) I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 01:32 ) Five score years ago, a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves, who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity, but 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. 100 years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. 100 years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. 100 years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 03:10 ) So we’ve come here today to dramatize the shameful condition. In a sense, we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which ever American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 04:25 ) But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom, and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 06:16 ) It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summit of the Negroes legitimate discontent will not pass until that is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 06:53 ) There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges. But that is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plain of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy, which has engulfed the Negro community, must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize their destiny is tied up in our destiny.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 08:54 ) They have come realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone, and as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. They are those who asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negroes basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating, For Whites Only. We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote, and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, we are not satisfied and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 10:48 ) I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that honor and suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friend, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, “We hold these truths to be self evident that all men are created.”

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 12:54 ) I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day, even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of our skin, but by the content of that character. I have a dream today.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 13:50 ) I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 14:27 ) I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain and the crooked places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is a faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 15:29 ) This will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning, My country, Tis of thee, Sweet land of Liberty, Of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, Land of the Pilgrim’s pride, From every mountainside, Let freedom ring. If America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

Martin Luther King Jr.: ( 15:58 ) So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snow capped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring, and when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholic, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

Transcribe Your Own Content Try Rev and save time transcribing, captioning, and subtitling.

Other Related Transcripts

Stay updated.

Get a weekly digest of the week’s most important transcripts in your inbox. It’s the news, without the news.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Martin Luther King: the story behind his 'I have a dream' speech

It’s 50 years since King gave that speech. Gary Younge finds out how it made history (and how it nearly fell flat)

T he night before the March on Washington , on 28 August 1963, Martin Luther King asked his aides for advice about the next day’s speech. “Don’t use the lines about ‘I have a dream’, his adviser Wyatt Walker told him. “It’s trite, it’s cliche. You’ve used it too many times already.”

King had indeed employed the refrain several times before. It had featured in an address just a week earlier at a fundraiser in Chicago, and a few months before that at a huge rally in Detroit. As with most of his speeches, both had been well received, but neither had been regarded as momentous.

This speech had to be different. While King was by now a national political figure, relatively few outside the black church and the civil rights movement had heard him give a full address. With all three television networks offering live coverage of the march for jobs and freedom, this would be his oratorical introduction to the nation.

After a wide range of conflicting suggestions from his staff, King left the lobby at the Willard hotel in DC to put the final touches to a speech he hoped would be received, in his words, “like the Gettysburg address”. “I am now going upstairs to my room to counsel with my Lord,” he told them. “I will see you all tomorrow.”

A few floors below King’s suite, Walker made himself available. King would call down and tell him what he wanted to say; Walker would write something he hoped worked, then head up the stairs to present it to King.

“When it came to my speech drafts,” wrote Clarence Jones, who had already penned the first draft, “[King] often acted like an interior designer. I would deliver four strong walls and he would use his God-given abilities to furnish the place so it felt like home.” King finished the outline at about midnight and then wrote a draft in longhand. One of his aides who went to King’s suite that night saw words crossed out three or four times. He thought it looked as though King were writing poetry. King went to sleep at about 4am, giving the text to his aides to print and distribute. The “I have a dream” section was not in it.

A few hours after King went to sleep, the march’s organiser, Bayard Rustin, wandered on to the Washington Mall, where the demonstration would take place later that day, with some of his assistants, to find security personnel and journalists outnumbering demonstrators. Political marches in Washington are now commonplace, but in 1963 attempting to stage a march of this size in that place was unprecedented. The movement had high hopes for a large turnout and originally set a goal of 100,000. From the reservations on coaches and trains alone, they guessed they should be at least close to that figure. But when the morning came, that expectation did little to calm their nerves. Reporters badgered Rustin about the ramifications for both the event and the movement if the crowd turned out to be smaller than anticipated. Rustin, forever theatrical, took a round pocket watch from his trousers and some paper from his jacket. Examining first the paper and then the watch, he turned to the reporters and said: “Everything is right on schedule.” The piece of paper was blank.

The first official Freedom Train arrived at Washington’s Union station from Pittsburgh at 8.02am, records Charles Euchner in Nobody Turn Me Around. Within a couple of hours, thousands were pouring through the stations every five minutes, while almost two buses a minute rolled into DC from across the country. About 250,000 people showed up that day. The Washington Mall was awash with Hollywood celebrities, including Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr, Burt Lancaster, James Garner and Harry Belafonte. Marlon Brando wandered around brandishing an electric cattle prod, a symbol of police brutality. Josephine Baker made it over from France. Paul Newman mingled with the crowd.

It was a hectic morning for King, paying a courtesy visit with other march leaders to politicians at the Capitol, but he still found time to fiddle with the speech. When he eventually walked to the podium, the typed final version was once more full of crossings out and scribbles.

Rustin had limited the speakers to just five minutes each, and threatened to come on with a crook and haul them from the podium when their time was up. But they all overran and, given the heat – 87F at noon – and humidity, the crowd’s mood began to wane. Weary from a night’s travel, many were anxious to make good time on the journey back and had already left. King was 16th on an official programme that included the national anthem, the invocation, a prayer, a tribute to women, two sets of songs and nine other speakers. Only the benediction and the pledge came after. Portions of the crowd had moved off to seek respite from the heat under the trees on the Mall while others dipped their feet in the reflecting pool. Those most eager for a view of the podium braved the sun under the shade of their umbrellas.

“There was… an air of subtle depression, of wistful apathy which existed in many,” wrote Norman Mailer. “One felt a little of the muted disappointment which attacks a crowd in the seventh inning of a very important baseball game when the score has gone 11-3. The home team is ahead, but the tension is broken: one’s concern is no longer noble.”

But if they were exhausted, they were no less excited. Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson had lifted spirits with I’ve Been ‘Buked and I’ve Been Scorned. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, followed, recalling his time as a rabbi in Berlin under Hitler: “A great people who had created a great civilisation had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hate, in the face of brutality and in the face of mass murder,” he said. “America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent.”

King was next. The area around the mic was crowded with speakers, dignitaries and their entourages. Wearing a black suit, black tie and white shirt, King edged through the melee towards the podium.

“I tell students today, ‘There were no jumbotrons [large screen TVs] back then,’ “ says Rachelle Horowitz, the young activist who organised transport to the march. “All people could see was a speck. And they listened to it.”

King started slowly, and stuck close to his prepared text. “I thought it was a good speech,” recalled John Lewis, the leader of the student wing of the movement, who had addressed the march earlier that day. “But it was not nearly as powerful as many I had heard him make. As he moved towards his final words, it seemed that he, too, could sense that he was falling short. He hadn’t locked into that power he so often found.”

King was winding up what would have been a well-received but, by his standards, fairly unremarkable oration. “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana,” he said. Then, behind him, Mahalia Jackson cried out: “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin.” Jackson had a particularly intimate emotional relationship with King, who when he felt down would call her for some “gospel musical therapy”.

“She was his favourite gospel singer, and he would ask her to sing The Old Rugged Cross or Jesus Met The Woman At The Well down the phone,” Jones explains. Jackson had seen him deliver the dream refrain in Detroit in June and clearly it had moved her.

“Go back to the slums and ghettoes of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed,” King said. Jackson shouted again: “Tell ‘em about the dream.” “Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends.” Then King grabbed the podium and set his prepared text to his left. “When he was reading from his text, he stood like a lecturer,” Jones says. “But from the moment he set that text aside, he took on the stance of a Baptist preacher.” Jones turned to the person standing next to him and said: “Those people don’t know it, but they’re about to go to church.”

A smattering of applause filled a pause more pregnant than most.

“So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.”

“Aw, shit,” Walker said. “He’s using the dream.”

For all King’s careful preparation, the part of the speech that went on to enter the history books was added extemporaneously while he was standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, speaking in full flight to the crowd. “I know that on the eve of his speech it was not in his mind to revisit the dream,” Jones insists.

It is open to debate just how spontaneous the insertion of the “I have a dream” section was (Euchner says a guest in the adjacent hotel room to King heard him rehearsing the segment the night before), but the two things we know for sure are that it was not in the prepared text and it wasn’t invented on the spot. King had been using the refrain for well over a year. Talking some months later of his decision to include the passage, King said: “I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point. The audience response was wonderful that day… And all of a sudden this thing came to me that… I’d used many times before… ‘I have a dream.’ And I just felt that I wanted to use it here… I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn’t come back to it.”

“Though [King] was extremely well known before he stepped up to the lectern,” Jones wrote, “he had stepped down on the other side of history.”

Watching the whole thing on TV in the White House, President John F Kennedy, who had never heard an entire King speech before, remarked: “He’s damned good. Damned good.” Almost everyone, including even King’s enemies, recognised the speech’s reach and resonance. William Sullivan, the FBI’s assistant director of domestic intelligence, recommended: “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous negro of the future of this nation.”

A few in the crowd were unimpressed. Anne Moody, a black activist who had made the trip from rural Mississippi, recalled: “I sat on the grass and listened to the speakers, to discover we had ‘dreamers’ instead of leaders leading us. Just about every one of them stood up there dreaming. Martin Luther King went on and on talking about his dream. I sat there thinking that in Canton we never had time to sleep, much less dream.”

But most were ebullient. “It would be like if, right now in the Arab spring, somebody made a speech that was 15 minutes long that summarised what this whole period of social change was all about,” one of King’s most trusted aides, Andrew Young, told me. “The country was in more turmoil than it had been in since before the second world war. People didn’t understand it. And he explained it. It wasn’t a black speech. It wasn’t just a Christian speech. It was an all-American speech.”

Fifty years on, the speech enjoys both national and global acclaim . A 1999 survey conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M University , of 137 leading scholars of public address, named it the greatest speech of the 20th century.

During the protests in Tiananmen Square, China, some protesters held up posters of King saying “I have a dream”. On the wall that Israel has built around parts of the West Bank, someone has written “I have a dream. This is not part of that dream.” The phrase “I have a dream” has been spotted in such disparate places as a train in Budapest and on a mural in suburban Sydney. Asked in 2008 whether they thought the speech was “relevant to people of your generation”, 68% of Americans said yes, including 76% of blacks and 67% of whites. Only 4% were not familiar with it.

But few of those in the movement thought at the time that it would be the speech by which King would be remembered 50 years later.

“Rustin always said that King’s genius was that he could simultaneously talk to a black audience about why they needed to achieve their freedom and address a white audience about why they should support that freedom,” recalls Horowitz. “Simultaneously. It was a genius that he could do that as one Gestalt… King’s was the poetry that made the march immortal. He capped off the day perfectly. He did what everybody wanted him to do and expected him to do. But I don’t think anybody predicted at the time that the speech would do what it did since.”

Their bemusement was justified. For if, in its immediate aftermath, the speech had any significant political impact, it was not obvious. “At the time of King’s death in April 1968 , his speech at the March on Washington had nearly vanished from public view,” writes Drew Hansen in his book about the speech, The Dream. “There was no reason to believe that King’s speech would one day come to be seen as a defining moment for his career and for the civil rights movement as a whole… King’s speech at the march is almost never mentioned during the monumental debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which occupy around 64,000 pages of the Congressional record.”

History does not objectively sift through speeches, pick out the best on their merits and then dedicate them faithfully to public memory. It commits itself to the task with great prejudice and fickle appreciation, in a manner that tells us as much about the historian and the times as the speech itself. The speech was marginalised because, in the last few years of his life, King himself was marginalised, and few who had the power to elevate his speech to iconic status had any self-interest in doing so. His growing propensity to take on issues of poverty, followed by his opposition to the Vietnam war, lost him the support of the political class and much of his white and more conservative base.

King’s speech at the March on Washington offers a positive prognosis on the apparently chronic American ailment of racism. As such, it is a rare thing to find in almost any culture or nation: an optimistic oration about race that acknowledges the desperate circumstances that made it necessary while still projecting hope, patriotism, humanism and militancy.

In the age of Obama and the Tea Party, there is something in there for everyone. It speaks, in the vernacular of the black church, with clarity and conviction to African Americans’ historical plight and looks forward to a time when that plight will be eliminated (“We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating ‘for whites only’. No, no, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream”).

Its nod to all that is sacred in American political culture, from the founding fathers to the American dream, makes it patriotic (“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”). It sets bigotry against colour-blindness while prescribing no route map for how we get from one to the other. (“I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists… little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”)

But the breadth of its appeal is to some extent at the expense of depth. It is in no small part so widely admired because the interpretations of what King was saying vary so widely. Polls show that while African Americans and American whites both agree about the extent to which “the dream has been realised”, they profoundly disagree on the state of contemporary race relations. The recent acquittal of George Zimmerman over the shooting of the black teenager Trayvon Martin illustrates the degree to which blacks and whites are less likely to see the same problems, more likely to disagree on the causes of those problems and, therefore, unlikely to agree on a remedy. Hearing the same speech, they understand different things.

Conservatives, meanwhile, have been keen to co-opt both King and the speech. I n 2010, Tea Party favourite Glenn Beck held the “Restoring Honour” rally at the Lincoln Memorial on the 47th anniversary of the speech, telling a crowd of about 90,000: “The man who stood down on those stairs… gave his life for everyone’s right to have a dream.” Almost a year later, black republican presidential candidate Herman Cain opened his speech to the southern Republican leadership conference with the words, “I have a dream.”

Their embrace of the speech has made some black intellectuals and activists wary. They fear that the speech can too easily be distorted in a manner that undermines the speaker’s legacy. “In the light of the determined misuse of King’s rhetoric, a modest proposal appears in order,” Georgetown university professor Michael Dyson wrote in 2001. “A 10-year moratorium on listening to or reading ‘I Have a Dream’.” At first blush, such a proposal seems absurd and counter- productive. After all, King’s words have convinced many Americans that racial justice should be aggressively pursued. The sad truth is, however, that our political climate has eroded the real point of King’s beautiful words.”

These responses tell us at least as much about now as then, perhaps more. The 50th anniversary of “I have a dream” arrives at a time when the president is black, whites are destined to become a minority in the US in little more than a generation, and civil rights-era protections are being dismantled. Segregationists have all but disappeared, even if segregation as a lived experience has not. Racism, however, remains.

Fifty years on, it is clear that in eliminating legal segregation – not racism, but formal, codified discrimination – the civil rights movement delivered the last moral victory in America for which there is still a consensus. While the struggle to defeat it was bitter and divisive, nobody today is seriously campaigning for the return of segregation or openly mourning its demise. The speech’s appeal lies in the fact that, whatever the interpretation, it remains the most eloquent, poetic, unapologetic and public articulation of that victory.

- Martin Luther King

- US politics

Barack Obama's speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial – full transcript

March on Washington: Barack Obama leads 50th anniversary celebrations

The meaning of Martin Luther King's speech: then and now

Thousands march on Washington to remember Martin Luther King's dream

March on Washington: 50th anniversary – in pictures

March on Washington: thousands arrive for 50th anniversary – as it happened

Remembering my time at the 1963 March on Washington

Comments (…), most viewed.

Freedom's Ring "I Have a Dream" Speech

Main navigation.

Freedom's Ring is Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech, annotated. Here you can compare the written and spoken speech, explore multimedia images, listen to movement activists and uncover historical context.

Fifty years ago, in the concluding address of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King demanded the riches of freedom and the security of justice. Today his language of love, nonviolent direct action and redemptive suffering, resonates globally in the millions who stand up for freedom and elevate democracy to its ideals. How do the echoes of King's Dream live within you?

Freedom's Ring serves as an innovative and thought-provoking resource for teachers, students, and the larger community. Evan Bissell, a Bay Area artist and educator, and webdesigner Erik Loyer worked with King Institute's Dr. Andrea McEvoy Spero, Dr. Clayborne Carson and Regina Covington to create an engaging experience that documents one of the most famous events in Civil Rights history. Freedom's Ring compliments the King Legacy Series by Beacon Press and the corresponding curriculum guide.

Freedom’s Ring

King’s “i have a dream” speech.

Freedom’s Ring is Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, animated. Here you can compare the written and spoken speech, explore multimedia images, listen to movement activists, and uncover historical context. Fifty years ago, as the culminating address of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King demanded the riches of freedom and the security of justice. Today, his language of love, nonviolent direct action, and redemptive suffering resonates globally in the millions who stand up for freedom together and elevate democracy to its ideals. How do the echoes of King’s Dream live within you?

Credits & Acknowledgements

Director, Art and Content: Evan Bissell Design and Programming: Erik Loyer Content, Curriculum Design and Project Coordinator: Andrea McEvoy Spero Project Advisor: Clayborne Carson Video: Owen Bissell Project Administration: Regina Covington

Freedom’s Ring is a project of The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University in collaboration with Beacon Press’s King Legacy Series.

We extend our deep appreciation to the many people whose work and lives contributed to Freedom’s Ring. Thank you to the interviewees: Aldo Billingslea, Clayborne Carson, Dorothy Cotton, Miriam Glickman, Kazu Haga, Bruce Hartford, Ericka Huggins, Clarence B. Jones, Kim Nalley, Wazir Peacock, and Marcus Shelby.

Thank you to Tenisha Armstrong. Her dedication and tireless efforts in editing Dr. King’s papers allow us to make this history available to teachers and students.

Thank you to the many photographers whose work has inspired much of this project and allowed these important histories to continue. We have made our best efforts to credit these photographers. They include: Bob Adelman, Eve Arnold, George Ballis, Martha Cooper, Benedict Fernandez, Bob Fitch, Declan Haun, Matt Herron, John Loengard, Danny Lyon, Spider Martin, Charles Moore/Black Star, Herbert Randall, Steve Schapiro, Flip Schulke, Maria Varela, and Tamio Wakayama.

Thank you to David Stein for his invaluable contributions and conversations about this history. Thanks to Lucas Guilkey for his work on the videos, Ming-kuo Hung for editing support, and Naomi Wilson for her comments on content.

Thanks to Beacon Press for editing support.

Thanks to Headlands Center for the Arts for the time and space to finish the project.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute Staff:

Clayborne Carson Director

Tenisha Armstrong Associate Director and Editor of the King Papers Project

Regina Covington Administrator

Andrea McEvoy Spero Director of Education

Clarence B. Jones Scholar in Residence

Susan Carson Editorial Consultant

Stacey Zwald Assistant Editor

Dave Beals Research Assistant

Video hosting by Critical Commons Content management by Scalar , a project of the Alliance for Networking Visual Culture

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time. New York: Dell, 1985. Print.

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King years, 1954-63. New York : Simon and Schuster, 1988. Print.

Carson, Clayborne, eds. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.. New York: Intellectual Properties Management; Warner Books, 1998. Print.

Freed, Leonard. This Is the Day: The March on Washington. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013. Print.

Hansen, Drew D.. The Dream: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Speech that Inspired a Nation. New York : Ecco. 2003. Print.

Johnson, Charles and Bob Adelman. King: The Photobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York : Viking, 2000. Print.

Jones, Clarence B. and Stuart Connelly. Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print.

Jones, William P.. The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights. New York : W.W. Norton, 2013. Print.

Jones, William P. and Labor and Working-Class History Association. “The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class.” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 7.3 (2010). Print.

Kasher, Steven. The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954-68. New York: Abbeville, 1996. Print.

Katznelson, Ira. Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time. New York: Liveright, 2013. Print.

Kelen, Leslie G., eds. This Light of Ours: Activist Photographers of the Civil Rights Movement. Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2011. Print.

LaFayette, Jr., Bernard and David C. Jehnsen. The Nonviolence Briefing Booklet: A 2-Day Orientation to Kingian Nonviolence Conflict Reconciliation. 1995. Galena: Institute for Human Rights and Responsibilities. 2007. Print.

Le Blanc, Paul. “Freedom Budget: The Promise of the Civil Rights Movement for Economic Justice.” WorkingUSA: The Journal of Labor & Society 16 (2013), 43-58. Print.

Levine, Ellen. Freedom's Children : Young Civil Rights Activists Tell Their Own Stories. New York : Putnam, 1993. Print.

Lewis, John and Michael D’Orso. Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998. Print.

Sundquist, Eric J.. King’s Dream. New Haven : Yale University, 2009. Print.

Scroll position

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Aug 28, 1963 ce: martin luther king jr. gives "i have a dream" speech.

On August 28, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington, a large gathering of civil rights protesters in Washington, D.C., United States.

Social Studies, Civics, U.S. History

Loading ...

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., took the podium at the March on Washington and addressed the gathered crowd, which numbered 200,000 people or more. His speech became famous for its recurring phrase “I have a dream.” He imagined a future in which “the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners" could "sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” a future in which his four children are judged not "by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." King's moving speech became a central part of his legacy. King was born in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, in 1929. Like his father and grandfather, King studied theology and became a Baptist pastor . In 1957, he was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference ( SCLC ), which became a leading civil rights organization. Under King's leadership, the SCLC promoted nonviolent resistance to segregation, often in the form of marches and boycotts. In his campaign for racial equality, King gave hundreds of speeches, and was arrested more than 20 times. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 for his "nonviolent struggle for civil rights ." On April 4, 1968, King was shot and killed while standing on a balcony of his motel room in Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

National Archives at New York City

Martin Luther King, Jr.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr., delivered a speech to a massive group of civil rights marchers gathered around the Lincoln memorial in Washington DC. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom brought together the nations most prominent civil rights leaders, along with tens of thousands of marchers, to press the United States government for equality. The culmination of this event was the influential and most memorable speech of Dr. King's career. Popularly known as the "I have a Dream" speech, the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. influenced the Federal government to take more direct actions to more fully realize racial equality.

Mister Maestro, Inc., and Twentieth Century Fox Records Company recorded the speech and offered the recording for sale. Dr. King and his attorneys claimed that the speech was copyrighted and the recording violated that copyright. The court found in favor of Dr. King. Among the papers filed in the case and available at the National Archives at New York City is a deposition given by Martin Luther King, Jr. and signed in his own hand.

Educational Activities

Discussion Questions:

- What was the official name for the event on August 28th, 1963? What does this title tell us about its focus?

- What organizations were involved in the the March on Washington? What does this tell us about the event?

- How does Martin Luther King, Jr. describe his writing process?

- What are the major issues of this case? In other words, what is Martin Luther King, Jr. disputing?

- How does Martin Luther King, Jr. describe his earlier speech on June 23rd in Detroit?

- How does Martin Luther King, Jr. compare and contrast the two "I have a dream..." speeches? What are the major similarities and differences?

Additional Resources from the National Archives concerning Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Official Program for the March on Washington

- The March (from the National Archives YouTube Channel)

- Searching for Martin Luther King, Jr., in the records of the National Archives

- Records on African Americans at the National Archives

- Teaching With Documents: Court Documents Related to Martin Luther King, Jr., and Memphis Sanitation Workers

Other Resources on Martin Luther King, Jr.

- The King Center

- National Park Service-National Historic Site

- Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream' speech in its entirety - National Public Radio (NPR)

NEWS ALERT: House passes reauthorization of key US surveillance program

EXCLUSIVE: ‘It’s not a hope — it’s a plan’: Interview with Army Corps of Engineers official on front line of Baltimore Key Bridge recovery

The true story behind MLK’s iconic ‘I Have a Dream’ speech

January 20, 2019, 9:00 PM

- Share This:

- share on facebook

- share on threads

- share on linkedin

- share on email

Share This Gallery:

This article originally appeared on WTOP.com on August 23, 2013.

WASHINGTON – If not for two spontaneous, subtle, impeccably-timed acts, the iconic phrase “I Have a Dream” delivered by Martin Luther King Jr. on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial may have never been spoken.

Among King’s inner circle were two people he spoke with virtually every day: his attorney Clarence B. Jones and New York businessman Stanley Levinson. In early July, when it was clear the march would happen, Jones and Levinson met with King regularly and were tasked with drafting a framework for the speech.

“We felt that Martin had an obligation to provide leadership, offering a vision that we were involved in action not activity; a clear-eyed assessment of the challenges we faced and a road map of how we could best meet those challenges,” Jones, who also served as King’s draft speechwriter, wrote in his book, “Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation.”

The night before the march, in a cordoned-off area of the Willard Hotel lobby, a final meeting was planned to go over the final details of King’s speech.

According to Jones, along with he and King, the other attendees at the meeting were Cleveland Robinson, Walter Fauntroy, Bernard Lee, Ralph Abernathy, Lawrence Reddick and Bayard Rustin.

After a vigorous debate in which Jones took notes, he went to his hotel room and turned his notes into words King could recite. A short time later, he delivered his draft to King. As was customary in their relationship of speechwriter and speech-giver, King took the draft to tweak it and make his own. Jones didn’t see the final draft.

As King made his way through the first several paragraphs of the speech, Jones realized King had not changed a word he had written.

“What I was writing was not my original writing,” Jones says. “It was merely a summary of what we had discussed before. I had simply put it into textual form in case he wanted to use that to reference in putting his speech together.”

Related Gallery

A look at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and his impact as the leader of the African-American Civil Rights Movement.

“That process was really as a result of taming egos,” says Jones.

After a series of meetings the week leading up to the march, it was decided King would appear in the middle of the program.

Jones wasn’t having it. In the middle of one planning meeting without King, he made his case for King to not only speak last, but to also speak the longest.

“I said you run the risk … that after he speaks a lot of the people at the march will get up and leave,” Jones says he told the group.

His plea worked.

“A. Phillip Randolph agreed with me, and Ted Brown and Bayard [Rustin], and so forth,” Jones says. “And, so it was agreed that [King] would be the last speaker.”

And, if needed, King would be given the most time for his speech.

By interrupting a single meeting, Jones had set the stage for history.

A preacher emerges

By 1963 Mahalia Jackson was already a legend in Gospel music. In 1950, she became the first Gospel singer to perform at Carnegie Hall. She sang at President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural ball in 1961. And before King took the stage to speak at the march, Jackson belted out the Negro spirituals “How I Got Over” and “I’ve Been ‘Buked, and I’ve Been Scorned.”

Jackson was also King’s favorite singer.

“When Martin would get low … he would track Mahalia down, wherever she was, and call her on the phone,” Jones writes in “Behind the Dream.”

Jackson had King’s trust.

She was also on the platform, sitting in the area of celebrities and dignitaries behind King, as he read from his prepared text :

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

King paused for 10 seconds as the crowd cheered him on. During that pause, the trajectory of the speech, and its place in history, transformed.

Jones says he was about 15 yards behind King, when he heard someone from the stage yell out to King.

“Mahalia Jackson…she shouted to him, ‘Tell them about the dream, Martin. Tell them about the dream’,” Jones says.

King also heard it.

“His reaction to it was to look in the direction of Mahalia, but then to take the prepared text that he was reading and slide it to the left side of the lectern,” Jones says.

King had gone from lecturer to preacher.

“I turned to somebody standing next to me and I said, ‘These people don’t know it, but they’re about to go to church’,” Jones says.

King proceeded, and it was in that moment that the “dream” became reality:

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.

The rest is history.

“From there on, that part of the speech that has become so celebrated as the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech was completely extemporaneous and was completely spontaneous,” Jones says.

King weaved his way through the remaining five minutes of the speech knitting together phrases and storylines culminating by a booming close in the spirit of the southern Baptist church world from which he was raised:

Free at last, free at last, Great God Almighty, We are free at last.

And even that line has a story.

“He had incorporated near the end some notes that he had made quoting in the words of an old Baptist preacher, ‘Free at last, free at last, free at last’,” Jones says.

Jones believes that while Dr. King’s speech immediately ascended into the rarified air of history-defining performances, the moment, aside from the words, in which it was given played a major role.

“The fact of the matter is that the overwhelming majority of people in America, white people particularly, had never heard or seen Martin Luther King, Jr. speak before. So, what you had that Wednesday, August 28, 1963, is that you had television pictures and the voice of Martin Luther King rebroadcast as part of the evening news in the top 100 television markets in the country. So, when the nation saw and heard this person speaking, they had as delayed reaction as I had when [the speech] was given. I was mesmerized.”

In order to protect King from being taken advantage of, Jones had the speech copyrighted. Though he faced a legal battle to have it upheld, the copyright is currently in effect until 2038.

Not even that process went smoothly. The speech was almost filed for copyright without a title. Jones was about to send the documents off to be filed with the speech titled “Martin Luther King’s Unpublished Speech of August 28, 1963.”

According to Jones, once it was pointed out to him that such a title wasn’t memorable, he changed it. With the white correction ribbon on his typewriter, Jones erased the black-typed ink, and above the line which read “Give the title of the work as it appears on the copies,” Jones gave the speech its proper name.

“I Have a Dream.”

Related News

Chronology of a civil rights icon: Martin Luther King Jr.

Free events for Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Arizona just revived an 1864 law criminalizing abortion. Here’s what’s happening in other states

Recommended.

Maryland gym shooting: Man in critical condition after shots fired at LA Fitness

Rainy days bring coastal flood warning for DC's Wharf, Northern Va. ahead of sunnier weekend

House passes reauthorization of key US surveillance program after days of upheaval over changes

Related categories:.

“I Have A Dream”: Annotated

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic speech, annotated with relevant scholarship on the literary, political, and religious roots of his words.

For this month’s Annotations, we’ve taken Martin Luther King, Jr.’s iconic “I Have A Dream” speech, and provided scholarly analysis of its groundings and inspirations—the speech’s religious, political, historical and cultural underpinnings are wide-ranging and have been read as jeremiad, call to action, and literature. While the speech itself has been used (and sometimes misused) to call for a “color-blind” country, its power is only increased by knowing its rhetorical and intellectual antecedents.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand signed the Emancipation Proclamation . This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity.

But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition.

In a sense we have come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.” But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check — a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now . This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God’s children. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred .

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream .

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day the state of Alabama, whose governor’s lips are presently dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, will be transformed into a situation where little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted , every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith with which I return to the South. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood . With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

This will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with a new meaning, “My country, ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim’s pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.”

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee!

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last! free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

For dynamic annotations of this speech and other iconic works, see The Understanding Series from JSTOR Labs .

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- Colorful Lights to Cure What Ails You

- Ayahs Abroad: Colonial Nannies Cross The Empire

The Taj Mahal Today

Beryl Markham, Warrior of the Skies

Recent posts.

- The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Policing

- A Brief Guide to Birdwatching in the Age of Dinosaurs

- Vulture Cultures

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

15 Things You Might Not Know About the ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

Fifty years ago today, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and it has since become one of the most famous orations in history. You’ve seen the clips and heard its most famous lines on countless occasions, but here are some of the things you probably didn’t know about how the speech was written, how it was delivered, and how it was received.

1. King had previously used his “dream” rhetoric before — “ many times before ,” as he acknowledged — in lesser-known speeches.

2 . King may have taken the “dream” language from then-22-year-old Prathia Hall , who used it during a speech at the burnt remains of the Mount Olive Baptist Church in 1962.

3. The night before the speech, King’s adviser Wyatt Walker suggested he not use any of that “dream” stuff during the March on Washington speech, calling it “trite” and “cliche.”

4. King didn’t write the speech entirely by himself. The first draft was written by his advisers Stanley Levison and Clarence Jones, and the final speech included input from many others.

5. The day before, King and his advisers met to discuss the speech in the lobby of the Willard Hotel because it would be harder to wiretap than a suite.

6. King was up until 4 a.m. the night before working on the speech.

7. The original draft was entitled “ Normalcy - Never Again” and didn’t contain any references to King’s dreams.

8. Before the speech, King told an aide that he wanted to deliver “ sort of a Gettysburg Address .” (Nailed it.)

9. King was the final speaker of the day, and some attendees — hot, tired, and anticipating a long trip home — had already left before he took the podium. Worst “gotta beat the traffic” ever?

10. King put aside his prepared remarks and extemporaneously delved into the “dream” section of the speech after his friend Mahalia Jackson, a gospel singer, shouted out to him : “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin.”

11. King borrowed a long passage about freedom ringing from various mountains across the country (“ So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania! Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!…”) from a 1952 speech by Rev. Archibald Carey .

12. Watching the speech from the White House, President Kennedy remarked either “ He’s damned good ” or “ That guy is really good .”

13. The head of the FBI ’s domestic intelligence division, William Sullivan, was not as enamored . Two days later, he wrote in a memo that the speech solidified King “as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.”

14. Many of the next day’s newspaper reporters overlooked not only the “dream” section of the speech, but even the speeches in general, focusing instead “ on the extraordinary spectacle of the march itself .”

15. Though celebrated now, the speech had “ nearly vanished from public view ” by the time of King’s death in 1968.

This list has been updated with another thing you probably didn’t know.

- dr. martin luther king jr.

- things that happened a while ago

- i have a dream

Most Viewed Stories

- Andrew Huberman’s Mechanisms of Control

- Thankfully, O.J. Simpson Was One of a Kind

- O.J. and the Untouchables: Getting Away With It

- Biden Has All But Caught Up With Trump in Polls

- What on Earth Is Aileen Cannon Doing?

- Arizona’s Senate Race Is a Battle Over the Nature of Reality

Editor’s Picks

Most Popular

- Thankfully, O.J. Simpson Was One of a Kind By Will Leitch

- Andrew Huberman’s Mechanisms of Control By Kerry Howley

- Biden Has All But Caught Up With Trump in Polls By Ed Kilgore

- O.J. and the Untouchables: Getting Away With It By Tad Friend

- What on Earth Is Aileen Cannon Doing? By Benjamin Hart

- Arizona’s Senate Race Is a Battle Over the Nature of Reality By Olivia Nuzzi

What is your email?

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

7 Things You May Not Know About MLK’s ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: August 3, 2023 | Original: January 13, 2021

On August 28, 1963, in front of a crowd of nearly 250,000 people spread across the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the Baptist preacher and civil rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his now-famous “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Organizers of the event, officially known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, had hoped 100,000 people would attend. In the end, more than twice that number flooded into the nation’s capital for the massive protest march, making it the largest demonstration in U.S. history to that date.

King’s “I Have a Dream” speech now stands out as one of the 20th century’s most unforgettable moments, but a few facts about it may still surprise you.

1. There were initially no women included in the event.

Despite the central role that women like Rosa Parks , Ella Baker, Daisy Bates and others played in the civil rights movement , all the speakers at the March on Washington were men. But at the urging of Anna Hedgeman, the only woman on the planning committee, the organizers added a “Tribute to Negro Women Fighters for Freedom” to the program. Bates spoke briefly in the place of Myrlie Evers, widow of the murdered civil rights leader Medgar Evers , and Parks and several others were recognized and asked to take a bow. “We will sit-in and we will kneel-in and we will lie-in if necessary until every Negro in America can vote,” Bates said. “This we pledge to the women of America.”

2. A white labor leader and a rabbi were among the 10 speakers on stage that day.

King was preceded by nine other speakers, notably including civil rights leaders like A. Philip Randolph and a young John Lewis , the future congressman from Georgia. The most prominent white speaker was Walter Reuther , head of the United Automobile Workers, a powerful labor union. The UAW helped fund the March on Washington, and Reuther would later march alongside King from Selma to Montgomery to protest for Black voting rights.

Joachim Prinz, the president of the American Jewish Congress, spoke directly before King. “A great people who had created a great civilization had become a nation of silent onlookers,” Prinz said of his experience as a rabbi in Berlin during the horrors perpetrated by Adolf Hitler ’s Nazi regime. “America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent.”

3. King almost didn’t deliver what is now the most famous part of the speech.

King had debuted the phrase “I have a dream” in his speeches at least nine months before the March on Washington, and used it several times since then. His advisers discouraged him from using the same theme again, and he had apparently drafted a version of the speech that didn’t include it. But as he spoke that day, the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson prompted him to “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” Abandoning his prepared text, King improvised the rest of his speech, with electrifying results.

4. The speech makes allusions to the Gettysburg Address, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, Shakespeare and the Bible.