Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Social Class in the United States

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish objective and subjective measures of social class.

- Outline the functionalist view of the American class structure.

- Outline the conflict view of the American class structure.

- Discuss whether the United States has much vertical social mobility.

There is a surprising amount of disagreement among sociologists on the number of social classes in the United States and even on how to measure social class membership. We first look at the measurement issue and then discuss the number and types of classes sociologists have delineated.

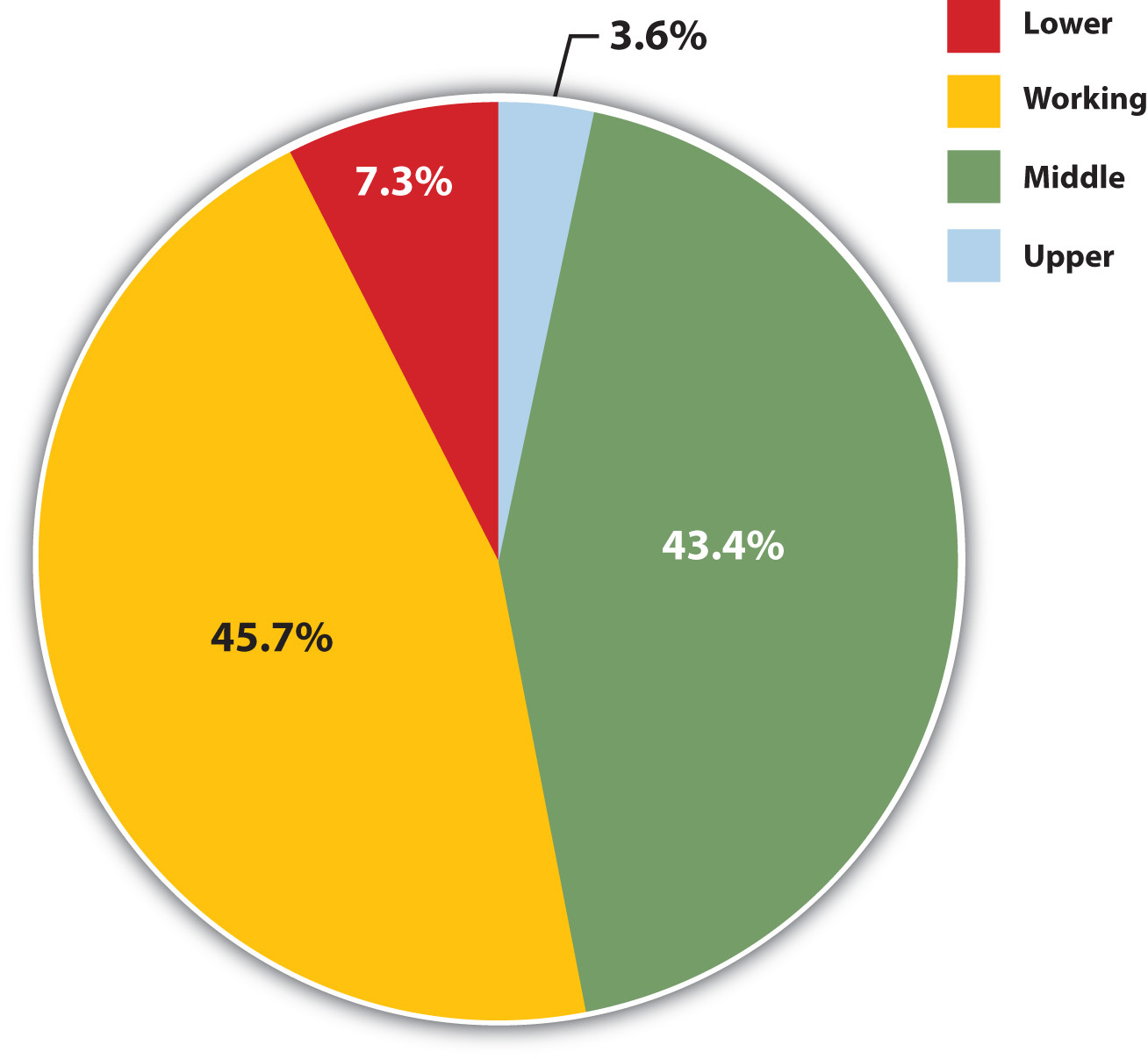

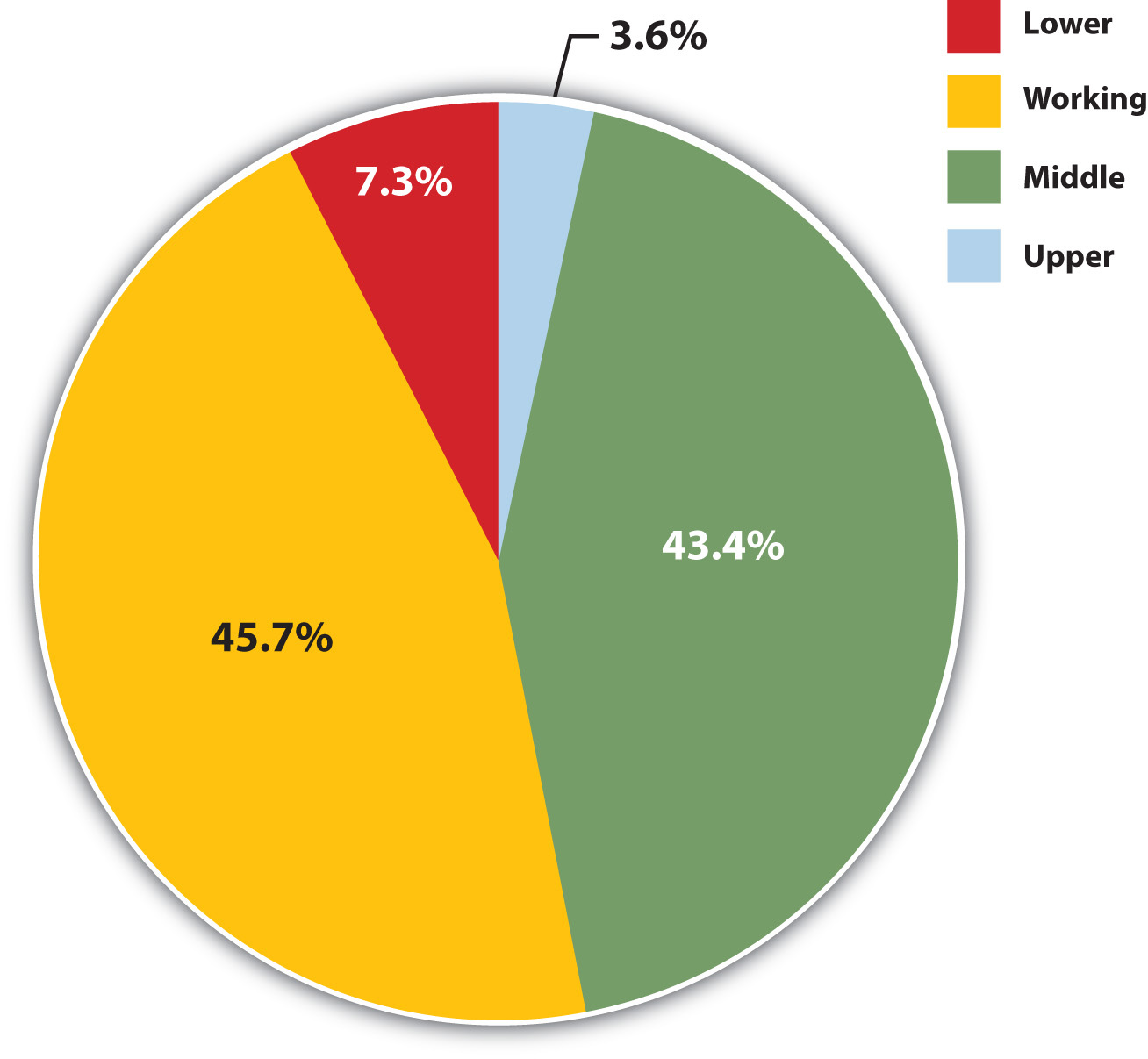

Measuring Social Class

We can measure social class either objectively or subjectively . If we choose the objective method, we classify people according to one or more criteria, such as their occupation, education, and/or income. The researcher is the one who decides which social class people are in based on where they stand in regard to these variables. If we choose the subjective method, we ask people what class they think they are in. For example, the General Social Survey asks, “If you were asked to use one of four names for your social class, which would you say you belong in: the lower class, the working class, the middle class, or the upper class?” Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” depicts responses to this question. The trouble with such a subjective measure is that some people say they are in a social class that differs from what objective criteria might indicate they are in. This problem leads most sociologists to favor objective measures of social class when they study stratification in American society.

Figure 8.3 Subjective Social Class Membership

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

Yet even here there is disagreement between functionalist theorists and conflict theorists on which objective measures to use. Functionalist sociologists rely on measures of socioeconomic status (SES) , such as education, income, and occupation, to determine someone’s social class. Sometimes one of these three variables is used by itself to measure social class, and sometimes two or all three of the variables are combined (in ways that need not concern us) to measure social class. When occupation is used, sociologists often rely on standard measures of occupational prestige. Since the late 1940s, national surveys have asked Americans to rate the prestige of dozens of occupations, and their ratings are averaged together to yield prestige scores for the occupations (Hodge, Siegel, & Rossi, 1964). Over the years these scores have been relatively stable. Here are some average prestige scores for various occupations: physician, 86; college professor, 74; elementary school teacher, 64; letter carrier, 47; garbage collector, 28; and janitor, 22.

Despite SES’s usefulness, conflict sociologists prefer different, though still objective, measures of social class that take into account ownership of the means of production and other dynamics of the workplace. These measures are closer to what Marx meant by the concept of class throughout his work, and they take into account the many types of occupations and workplace structures that he could not have envisioned when he was writing during the 19th century.

For example, corporations have many upper-level managers who do not own the means of production but still determine the activities of workers under them. They thus do not fit neatly into either of Marx’s two major classes, the bourgeoisie or the proletariat. Recognizing these problems, conflict sociologists delineate social class on the basis of several factors, including the ownership of the means of production, the degree of autonomy workers enjoy in their jobs, and whether they supervise other workers or are supervised themselves (Wright, 2000).

The American Class Structure

As should be evident, it is not easy to determine how many social classes exist in the United States. Over the decades, sociologists have outlined as many as six or seven social classes based on such things as, once again, education, occupation, and income, but also on lifestyle, the schools people’s children attend, a family’s reputation in the community, how “old” or “new” people’s wealth is, and so forth (Coleman & Rainwater, 1978; Warner & Lunt, 1941). For the sake of clarity, we will limit ourselves to the four social classes included in Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” : the upper class, the middle class, the working class, and the lower class. Although subcategories exist within some of these broad categories, they still capture the most important differences in the American class structure (Gilbert, 2011). The annual income categories listed for each class are admittedly somewhat arbitrary but are based on the percentage of households above or below a specific income level.

The Upper Class

Depending on how it is defined, the upper class consists of about 4% of the U.S. population and includes households with annual incomes (2009 data) of more than $200,000 (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2010). Some scholars would raise the ante further by limiting the upper class to households with incomes of at least $500,000 or so, which in turn reduces this class to about 1% of the population, with an average wealth (income, stocks and bonds, and real estate) of several million dollars. However it is defined, the upper class has much wealth, power, and influence (Kerbo, 2009).

The upper class in the United States consists of about 4% of all households and possesses much wealth, power, and influence.

Steven Martin – Highland Park Mansion – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Members of the upper-upper class have “old” money that has been in their families for generations; some boast of their ancestors coming over on the Mayflower . They belong to exclusive clubs and live in exclusive neighborhoods; have their names in the Social Register ; send their children to expensive private schools; serve on the boards of museums, corporations, and major charities; and exert much influence on the political process and other areas of life from behind the scenes. Members of the lower-upper class have “new” money acquired through hard work, lucky investments, and/or athletic prowess. In many ways their lives are similar to those of their old-money counterparts, but they do not enjoy the prestige that old money brings. Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft and the richest person in the United States in 2009, would be considered a member of the lower-upper class because his money is too “new.” Because he does not have a long-standing pedigree, upper-upper class members might even be tempted to disparage his immense wealth, at least in private.

The Middle Class

Many of us like to think of ourselves in the middle class, as Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” showed, and many of us are. The middle class includes the 46% of all households whose annual incomes range from $50,000 to $199,999. As this very broad range suggests, the middle class includes people with many different levels of education and income and many different types of jobs. It is thus helpful to distinguish the upper-middle class from the lower-middle class on the upper and lower ends of this income bracket, respectively. The upper-middle class has household incomes from about $150,000 to $199,000, amounting to about 4.4% of all households. People in the upper-middle class typically have college and, very often, graduate or professional degrees; live in the suburbs or in fairly expensive urban areas; and are bankers, lawyers, engineers, corporate managers, and financial advisers, among other occupations.

The upper-middle class in the United States consists of about 4.4% of all households, with incomes ranging from $150,000 to $199,000.

Alyson Hurt – Back Porch – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The lower-middle class has household incomes from about $50,000 to $74,999, amounting to about 18% of all families. People in this income bracket typically work in white-collar jobs as nurses, teachers, and the like. Many have college degrees, usually from the less prestigious colleges, but many also have 2-year degrees or only a high school degree. They live somewhat comfortable lives but can hardly afford to go on expensive vacations or buy expensive cars and can send their children to expensive colleges only if they receive significant financial aid.

The Working Class

The working class in the United States consists of about 25% of all households, whose members work in blue-collar jobs and less skilled clerical positions.

Lisa Risager – Ebeltoft – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Working-class households have annual incomes between about $25,000 and $49,999 and constitute about 25% of all U.S. households. They generally work in blue-collar jobs such as factory work, construction, restaurant serving, and less skilled clerical positions. People in the working class typically do not have 4-year college degrees, and some do not have high school degrees. Although most are not living in official poverty, their financial situation is very uncomfortable. A single large medical bill or expensive car repair would be almost impossible to pay without going into considerable debt. Working-class families are far less likely than their wealthier counterparts to own their own homes or to send their children to college. Many of them live at risk for unemployment as their companies downsize by laying off workers even in good times, and hundreds of thousands began to be laid off when the U.S. recession began in 2008.

The Lower Class

The lower class or poor in the United States constitute about 25% of all households. Many poor individuals lack high school degrees and are unemployed or employed only part time.

Chris Hunkeler – Trailer Homes – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Although lower class is a common term, many observers prefer a less negative-sounding term like the poor, which is the term used here. The poor have household incomes under $25,000 and constitute about 25% of all U.S. households. Many of the poor lack high school degrees, and many are unemployed or employed only part time in semiskilled or unskilled jobs. When they do work, they work as janitors, house cleaners, migrant laborers, and shoe shiners. They tend to rent apartments rather than own their own homes, lack medical insurance, and have inadequate diets. We will discuss the poor further when we focus later in this chapter on inequality and poverty in the United States.

Social Mobility

Regardless of how we measure and define social class, what are our chances of moving up or down within the American class structure? As we saw earlier, the degree of vertical social mobility is a key distinguishing feature of systems of stratification. Class systems such as in the United States are thought to be open, meaning that social mobility is relatively high. It is important, then, to determine how much social mobility exists in the United States.

Here we need to distinguish between two types of vertical social mobility. Intergenerational mobility refers to mobility from one generation to the next within the same family. If children from poor parents end up in high-paying jobs, the children have experienced upward intergenerational mobility. Conversely, if children of college professors end up hauling trash for a living, these children have experienced downward intergenerational mobility. Intragenerational mobility refers to mobility within a person’s own lifetime. If you start out as an administrative assistant in a large corporation and end up as an upper-level manager, you have experienced upward intragenerational mobility. But if you start out from business school as an upper-level manager and get laid off 10 years later because of corporate downsizing, you have experienced downward intragenerational mobility.

Sociologists have conducted a good deal of research on vertical mobility, much of it involving the movement of males up or down the occupational prestige ladder compared to their fathers, with the earliest studies beginning in the 1960s (Blau & Duncan, 1967; Featherman & Hauser, 1978). For better or worse, the focus on males occurred because the initial research occurred when many women were still homemakers and also because women back then were excluded from many studies in the social and biological sciences. The early research on males found that about half of sons end up in higher-prestige jobs than their fathers had but that the difference between the sons’ jobs and their fathers’ was relatively small. For example, a child of a janitor may end up running a hardware store but is very unlikely to end up as a corporate executive. To reach that lofty position, it helps greatly to have parents in jobs much more prestigious than a janitor’s. Contemporary research also finds much less mobility among African Americans and Latinos than among non-Latino whites with the same education and family backgrounds, suggesting an important negative impact of racial and ethnic discrimination (see Chapter 7 “Deviance, Crime, and Social Control” ).

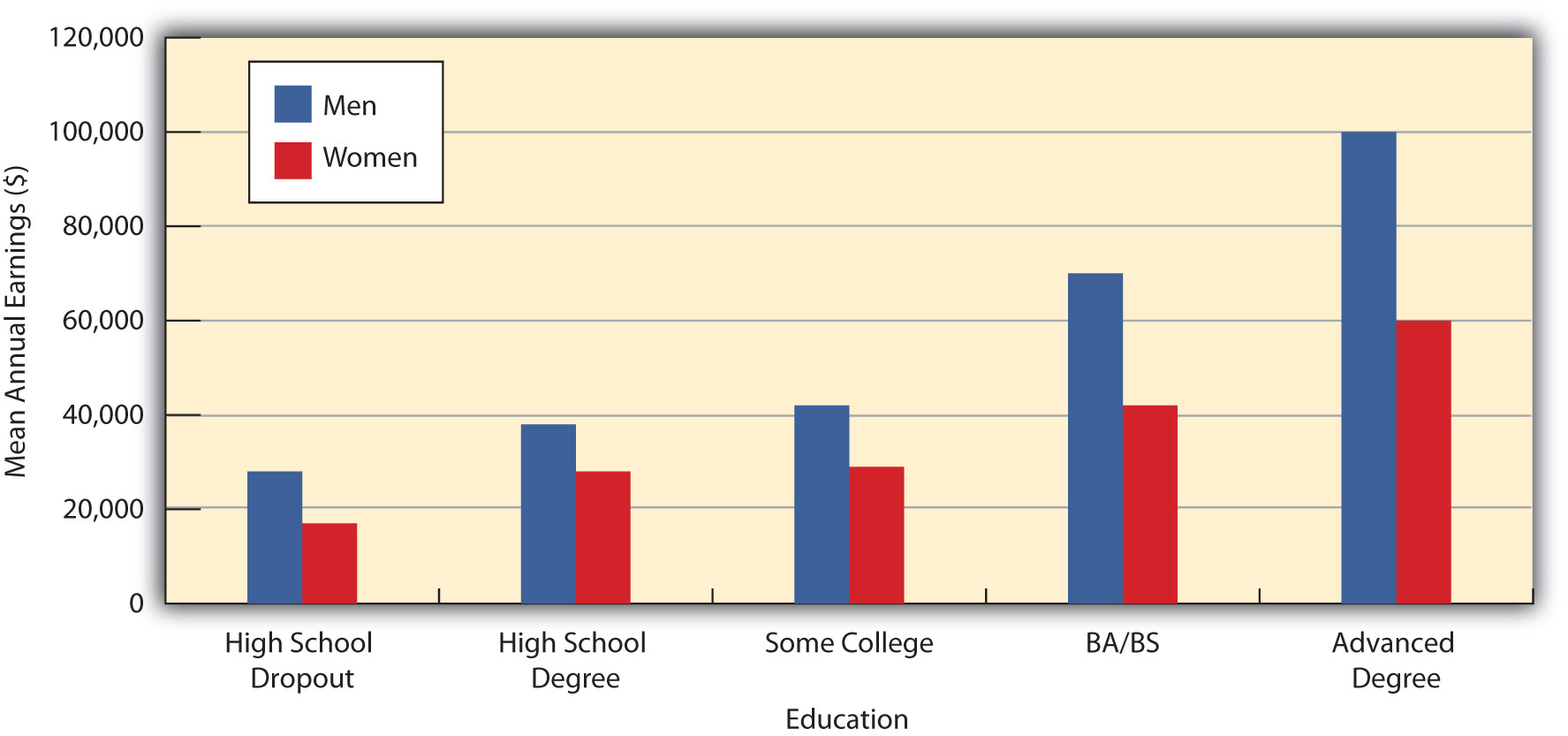

A college education is a key step toward achieving upward social mobility. However, the payoff of education is often higher for men than for women and for whites than for people of color.

Nazareth College – Commencement 2013 – CC BY 2.0.

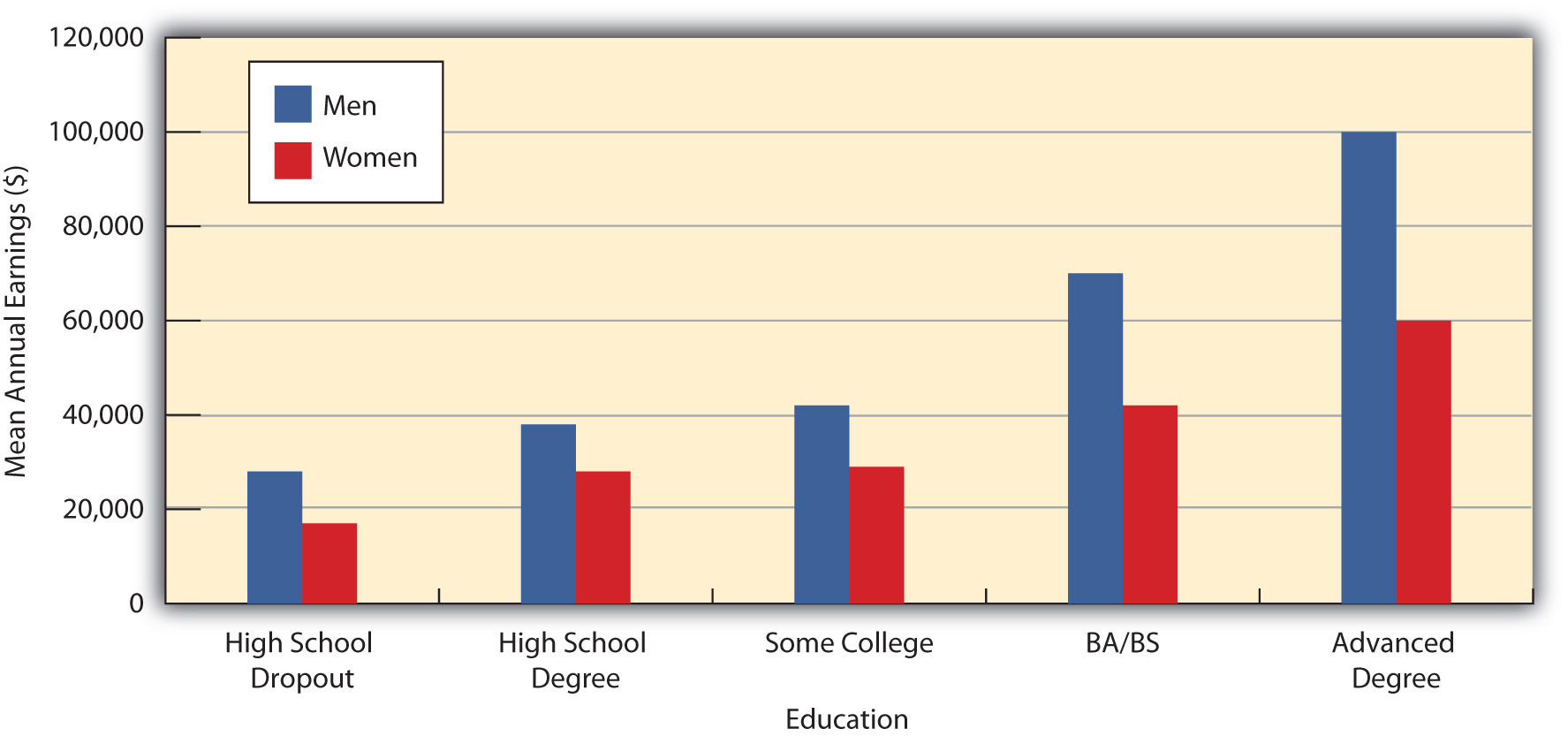

A key vehicle for upward mobility is formal education. Regardless of the socioeconomic status of our parents, we are much more likely to end up in a high-paying job if we attain a college degree or, increasingly, a graduate or professional degree. Figure 8.4 “Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007” vividly shows the difference that education makes for Americans’ median annual incomes. Notice, however, that for a given level of education, men’s incomes are greater than women’s. Figure 8.4 “Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007” thus suggests that the payoff of education is higher for men than for women, and many studies support this conclusion (Green & Ferber, 2008). The reasons for this gender difference are complex and will be discussed further in Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” . To the extent vertical social mobility exists in the United States, then, it is higher for men than for women and higher for whites than for people of color.

Figure 8.4 Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010 . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab .

Certainly the United States has upward social mobility, even when we take into account gender and racial discrimination. Whether we conclude the United States has a lot of vertical mobility or just a little is the key question, and the answer to this question depends on how the data are interpreted. People can and do move up the socioeconomic ladder, but their movement is fairly limited. Hardly anyone starts at the bottom of the ladder and ends up at the top. As we see later in this chapter, recent trends in the U.S. economy have made it more difficult to move up the ladder and have even worsened the status of some people.

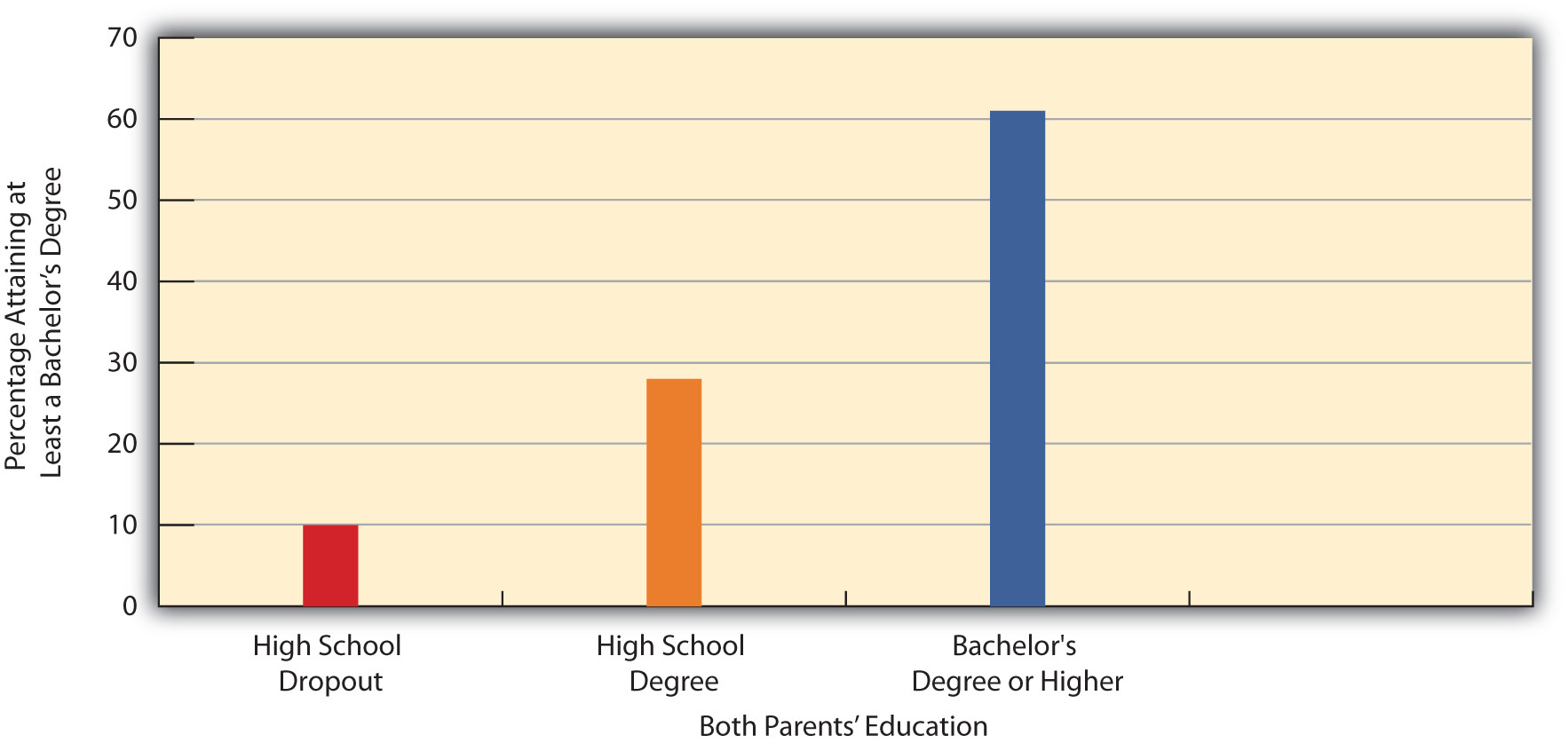

One way of understanding the issue of U.S. mobility is to see how much parents’ education affects the education their children attain. Figure 8.5 “Parents’ Education and Percentage of Respondents Who Have a College Degree” compares how General Social Survey respondents with parents of different educational backgrounds fare in attaining a college (bachelor’s) degree. For the sake of clarity, the figure includes only those respondents whose parents had the same level of education as each other: they either both dropped out of high school, both were high school graduates, or both were college graduates.

Figure 8.5 Parents’ Education and Percentage of Respondents Who Have a College Degree

As Figure 8.5 “Parents’ Education and Percentage of Respondents Who Have a College Degree” indicates, we are much more likely to get a college degree if our parents had college degrees themselves. The two bars for respondents whose parents were high school graduates or dropouts, respectively, do represent upward mobility, because the respondents are graduating from college even though their parents did not. But the three bars taken together also show that our chances of going to college depend heavily on our parents’ education (and presumably their income and other aspects of our family backgrounds). The American Dream does exist, but it is much more likely to remain only a dream unless we come from advantaged backgrounds. In fact, there is less vertical mobility in the United States than in other Western democracies. As a recent analysis summarized the evidence, “There is considerably more mobility in most of the other developed economies of Europe and Scandinavia than in the United States” (Mishel, Bernstein, & Shierholz, 2009, p. 108).

Key Takeaways

- Several ways of measuring social class exist. Functionalist and conflict sociologists disagree on which objective criteria to use in measuring social class. Subjective measures of social class, which rely on people rating their own social class, may lack some validity.

- Sociologists disagree on the number of social classes in the United States, but a common view is that the United States has four classes: upper, middle, working, and lower. Further variations exist within the upper and middle classes.

- The United States has some vertical social mobility, but not as much as several nations in Western Europe.

For Your Review

- Which way of measuring social class do you prefer, objective or subjective? Explain your answer.

- Which objective measurement of social class do you prefer, functionalist or conflict? Explain your answer.

Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American occupational structure . New York, NY: Wiley.

Coleman, R. P., & Rainwater, L. (1978). Social standing in America . New York, NY: Basic Books.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2010). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009 (Current Population Report P60-238). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Featherman, D. L., & Hauser, R. M. (1978). Opportunity and change . New York, NY: Academic Press.

Gilbert, D. (2011). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality (8th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Green, C. A., & Ferber, M. A. (2008). The long-term impact of labor market interruptions: How crucial is timing? Review of Social Economy, 66 , 351–379.

Hodge, R. W., Siegel, P., & Rossi, P. (1964). Occupational prestige in the United States, 1925–63. American Journal of Sociology, 70 , 286–302.

Kerbo, H. R. (2009). Social stratification and inequality . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Mishel, L., Bernstein, J., & Shierholz, H. (2009). The state of working America 2008/2009 . Ithaca, NY: ILR Press [An imprint of Cornell University Press].

Warner, W. L., & Lunt, P. S. (1941). The social life of a modern community . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wright, E. O. (2000). Class counts: Comparative studies in class analysis . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Social Class in the United States

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish objective and subjective measures of social class.

- Discuss whether the United States has much vertical social mobility.

Most sociologists define social class as a grouping based on similar social factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. These factors affect how much power and prestige a person has. Social stratification reflects an unequal distribution of resources. In most cases, having more money means having more power or more opportunities. There is a surprising amount of disagreement among sociologists on the number of social classes in the United States and even on how to measure social class membership. We first look at the measurement issue and then discuss the number and types of classes sociologists have delineated.

Measuring Social Class

We can measure social class either objectively or subjectively . If we choose the objective method, we classify people according to one or more criteria, such as their occupation, education, and/or income. The researcher is the one who decides which social class people are in based on where they stand in regard to these variables. If we choose the subjective method, we ask people what class they think they are in. For example, the General Social Survey asks, “If you were asked to use one of four names for your social class, which would you say you belong in: the lower class, the working class, the middle class, or the upper class?” Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” depicts responses to this question. The trouble with such a subjective measure is that some people say they are in a social class that differs from what objective criteria might indicate they are in. This problem leads most sociologists to favor objective measures of social class when they study stratification in American society.

Figure 8.3 Subjective Social Class Membership

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

Yet even here there is disagreement between functionalist theorists and conflict theorists on which objective measures to use. Functionalist sociologists rely on measures of socioeconomic status (SES) , such as education, income, and occupation, to determine someone’s social class. Sometimes one of these three variables is used by itself to measure social class, and sometimes two or all three of the variables are combined (in ways that need not concern us) to measure social class. When occupation is used, sociologists often rely on standard measures of occupational prestige. Since the late 1940s, national surveys have asked Americans to rate the prestige of dozens of occupations, and their ratings are averaged together to yield prestige scores for the occupations (Hodge, Siegel, & Rossi, 1964). Over the years these scores have been relatively stable. Here are some average prestige scores for various occupations: physician, 86; college professor, 74; elementary school teacher, 64; letter carrier, 47; garbage collector, 28; and janitor, 22.

Despite SES’s usefulness, conflict sociologists prefer different, though still objective, measures of social class that take into account ownership of the means of production and other dynamics of the workplace. These measures are closer to what Marx meant by the concept of class throughout his work, and they take into account the many types of occupations and workplace structures that he could not have envisioned when he was writing during the 19th century.

For example, corporations have many upper-level managers who do not own the means of production but still determine the activities of workers under them. They thus do not fit neatly into either of Marx’s two major classes, the bourgeoisie or the proletariat. Recognizing these problems, conflict sociologists delineate social class on the basis of several factors, including the ownership of the means of production, the degree of autonomy workers enjoy in their jobs, and whether they supervise other workers or are supervised themselves (Wright, 2000).

The American Class Structure

As should be evident, it is not easy to determine how many social classes exist in the United States. Over the decades, sociologists have outlined as many as six or seven social classes based on such things as, once again, education, occupation, and income, but also on lifestyle, the schools people’s children attend, a family’s reputation in the community, how “old” or “new” people’s wealth is, and so forth (Coleman & Rainwater, 1978; Warner & Lunt, 1941). For the sake of clarity, we will limit ourselves to the four social classes included in Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” : the upper class, the middle class, the working class, and the lower class. Although subcategories exist within some of these broad categories, they still capture the most important differences in the American class structure (Gilbert, 2011). The annual income categories listed for each class are admittedly somewhat arbitrary but are based on the percentage of households above or below a specific income level.

The Upper Class

The upper class is considered the top, and only the powerful elite get to see the view from there. In the United States, people with extreme wealth make up 1 percent of the population, and they own one-third of the country’s wealth (Beeghley 2008).

The upper class in the United States consists of about 1% of all households and possesses much wealth, power, and influence.

Steven Martin – Highland Park Mansion – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Money provides not just access to material goods, but also access to a lot of power. As corporate leaders, members of the upper class make decisions that affect the job status of millions of people. As media owners, they influence the collective identity of the nation. They run the major network television stations, radio broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, publishing houses, and sports franchises. As board members of the most influential colleges and universities, they influence cultural attitudes and values. As philanthropists, they establish foundations to support social causes they believe in. As campaign contributors, they sway politicians and fund campaigns, sometimes to protect their own economic interests.

U.S. society has historically distinguished between “old money” (inherited wealth passed from one generation to the next) and “new money” (wealth you have earned and built yourself). While both types may have equal net worth, they have traditionally held different social standings. People of old money, firmly situated in the upper class for generations, have held high prestige. Their families have socialized them to know the customs, norms, and expectations that come with wealth. Often, the very wealthy don’t work for wages. Some study business or become lawyers in order to manage the family fortune. Others, such as Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian, capitalize on being a rich socialite and transform that into celebrity status, flaunting a wealthy lifestyle.

However, new-money members of the upper class are not oriented to the customs and mores of the elite. They haven’t gone to the most exclusive schools. They have not established old-money social ties. People with new money might flaunt their wealth, buying sports cars and mansions, but they might still exhibit behaviors attributed to the middle and lower classes.

The Middle Class

Many people consider themselves middle class, but there are differing ideas about what that means. People with annual incomes of $150,000 call themselves middle class, as do people who annually earn $30,000. That helps explain why, in the United States, the middle class is broken into upper and lower subcategories. Upper-middle-class people tend to hold bachelor’s and postgraduate degrees. They’ve studied subjects such as business, management, law, or medicine. Lower-middle-class members hold bachelor’s degrees from four-year colleges or associate’s degrees from two-year community or technical colleges.

The upper-middle class in the United States consists of about 4.4% of all households, with incomes ranging from $150,000 to $199,000.

Alyson Hurt – Back Porch – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Comfort is a key concept to the middle class. Middle-class people work hard and live fairly comfortable lives. Upper-middle-class people tend to pursue careers that earn comfortable incomes. They provide their families with large homes and nice cars. They may go skiing or boating on vacation. Their children receive high-quality education and healthcare (Gilbert 2010).

In the lower middle class, people hold jobs supervised by members of the upper middle class. They fill technical, lower-level management or administrative support positions. Compared to lower-class work, lower-middle-class jobs carry more prestige and come with slightly higher paychecks. With these incomes, people can afford a decent, mainstream lifestyle, but they struggle to maintain it. They generally don’t have enough income to build significant savings. In addition, their grip on class status is more precarious than in the upper tiers of the class system. When budgets are tight, lower-middle-class people are often the ones to lose their jobs.

The Working Class

The working class in the United States consists of about 25% of all households, whose members work in blue-collar jobs and less skilled clerical positions.

Lisa Risager – Ebeltoft – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Working-class households generally work in blue-collar jobs such as factory work, construction, restaurant serving, and less skilled clerical positions. People in the working class typically do not have 4-year college degrees, and some do not have high school degrees. Although most are not living in official poverty, their financial situation is very uncomfortable. A single large medical bill or expensive car repair would be almost impossible to pay without going into considerable debt. Working-class families are far less likely than their wealthier counterparts to own their own homes or to send their children to college. Many of them live at risk for unemployment as their companies downsize by laying off workers even in good times, and hundreds of thousands began to be laid off when the U.S. recession began in 2008.

The Lower Class

The lower class or poor in the United States constitute about 25% of all households. Many poor individuals lack high school degrees and are unemployed or employed only part time.

Chris Hunkeler – Trailer Homes – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Although lower class is a common term, many observers prefer a less-negative sounding term like the poor, which is used here. Just like the middle and upper classes, the lower class can be divided into subsets: the working class, the working poor, and the underclass. Compared to the lower middle class, lower-class people have less of an educational background and earn smaller incomes. They work jobs that require little prior skill or experience and often do routine tasks under close supervision.

The working poor have unskilled, low-paying employment. However, their jobs rarely offer benefits such as healthcare or retirement planning, and their positions are often seasonal or temporary. They work as sharecroppers, migrant farm workers, house cleaners, and day laborers. Some are high school dropouts. Some are illiterate, unable to read job ads.

How can people work full-time and still be poor? Even working full-time, millions of the working poor earn incomes too meager to support a family. Minimum wage varies from state to state, but in many states it is approaching $8.00 per hour (Department of Labor 2014). At that rate, working 40 hours a week earns $320. That comes to $16,640 a year, before tax and deductions. Even for a single person, the pay is low. A married couple with children will have a hard time covering expenses.

The underclass is the United States’ lowest tier. Members of the underclass live mainly in inner cities. Many are unemployed or underemployed. Those who do hold jobs typically perform menial tasks for little pay. Some of the underclass are homeless. For many, welfare systems provide a much-needed support through food assistance, medical care, housing, and the like.

We will discuss the poor further when we focus later in this chapter on inequality and poverty in the United States.

Social Mobility

Social mobility refers to the ability to change positions within a social stratification system. When people improve or diminish their economic status in a way that affects social class, they experience social mobility.

Individuals can experience upward or downward social mobility for a variety of reasons. Upward mobility refers to an increase—or upward shift—in social class. In the United States, people applaud the rags-to-riches achievements of celebrities like Oprah Winfrey or LeBron James. But the truth is that relative to the overall population, the number of people who rise from poverty to wealth is very small. Still, upward mobility is not only about becoming rich and famous. In the United States, people who earn a college degree, get a job promotion, or marry someone with a good income may move up socially. In contrast, downward mobility indicates a lowering of one’s social class. Some people move downward because of business setbacks, unemployment, or illness. Dropping out of school, losing a job, or getting a divorce may result in a loss of income or status and, therefore, downward social mobility.

Nazareth College – Commencement 2013 – CC BY 2.0.

A key vehicle for upward mobility is formal education. Regardless of the socioeconomic status of our parents, we are much more likely to end up in a high-paying job if we attain a college degree or, increasingly, a graduate or professional degree. Figure 8.4 “Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007” vividly shows the difference that education makes for Americans’ median annual incomes. Notice, however, that for a given level of education, men’s incomes are greater than women’s. Figure 8.4 “Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007” thus suggests that the payoff of education is higher for men than for women, and many studies support this conclusion (Green & Ferber, 2008). The reasons for this gender difference are complex and will be discussed further in Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” . To the extent vertical social mobility exists in the United States, then, it is higher for men than for women and higher for whites than for people of color.

Figure 8.4 Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010 . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab .

It is not uncommon for different generations of a family to belong to varying social classes. This is known as intergenerational mobility . For example, an upper-class executive may have parents who belonged to the middle class. In turn, those parents may have been raised in the lower class. Patterns of intergenerational mobility can reflect long-term societal changes.

Similarly, intragenerational mobility refers to changes in a person’s social mobility over the course of his or her lifetime. For example, the wealth and prestige experienced by one person may be quite different from that of his or her siblings.

Structural mobility happens when societal changes enable a whole group of people to move up or down the social class ladder. Structural mobility is attributable to changes in society as a whole, not individual changes. In the first half of the twentieth century, industrialization expanded the U.S. economy, raising the standard of living and leading to upward structural mobility. In today’s work economy, the recent recession and the outsourcing of jobs overseas have contributed to high unemployment rates. Many people have experienced economic setbacks, creating a wave of downward structural mobility.

When analyzing the trends and movements in social mobility, sociologists consider all modes of mobility. Scholars recognize that mobility is not as common or easy to achieve as many people think. In fact, some consider social mobility a myth. The American Dream does exist, but it is much more likely to remain only a dream unless we come from advantaged backgrounds. In fact, there is less vertical mobility in the United States than in other Western democracies. As a recent analysis summarized the evidence, “There is considerably more mobility in most of the other developed economies of Europe and Scandinavia than in the United States” (Mishel, Bernstein, & Shierholz, 2009, p. 108).

Key Takeaways

- Several ways of measuring social class exist. Functionalist and conflict sociologists disagree on which objective criteria to use in measuring social class. Subjective measures of social class, which rely on people rating their own social class, may lack some validity.

- Sociologists disagree on the number of social classes in the United States, but a common view is that the United States has four classes: upper, middle, working, and lower. Further variations exist within the upper and middle classes.

- The United States has some vertical social mobility, but not as much as several nations in Western Europe.

Beeghley, Leonard. 2008. The Structure of Social Stratification in the United States . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Coleman, R. P., & Rainwater, L. (1978). Social standing in America . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gilbert, D. (2011). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality (8th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Green, C. A., & Ferber, M. A. (2008). The long-term impact of labor market interruptions: How crucial is timing? Review of Social Economy, 66 , 351–379.

Hodge, R. W., Siegel, P., & Rossi, P. (1964). Occupational prestige in the United States, 1925–63. American Journal of Sociology, 70 , 286–302.

Mishel, L., Bernstein, J., & Shierholz, H. (2009). The state of working America 2008/2009 . Ithaca, NY: ILR Press [An imprint of Cornell University Press].

Warner, W. L., & Lunt, P. S. (1941). The social life of a modern community . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wright, E. O. (2000). Class counts: Comparative studies in class analysis . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Introduction to Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The dangerous separation of the American upper middle class

Subscribe to the center for economic security and opportunity newsletter, richard v. reeves richard v. reeves president - american institute for boys and men @richardvreeves.

September 3, 2015

- 10 min read

The American upper middle class is separating, slowly but surely, from the rest of society. This separation is most obvious in terms of income—where the top fifth have been prospering while the majority lags behind. But the separation is not just economic. Gaps are growing on a whole range of dimensions, including family structure, education, lifestyle, and geography. Indeed, these dimensions of advantage appear to be clustering more tightly together, each thereby amplifying the effect of the other.

In a new series of Social Mobility Memos, we will examine the state of the American upper middle class: its composition, degree of separation from the majority, and perpetuation over time and across generations. Some may wonder about the moral purpose of such an exercise. After all, what does it matter if those at the top are flourishing? To be sure, there is a danger here of indulging in the economics of envy. Whether the separation is a problem is a question on which sensible people can disagree. The first task, however, is to get a sense of what’s going on.

“We are the 80 percent!” Not quite the same ring as “We are the 99 percent!”

For many, the most attractive class dividing line is the one between those at the very, very top and everybody else. It is true that the top 1 percent is pulling away very dramatically from the bottom 99 percent. But the top 1 percent is by definition a small group. It is not plausible to claim that the individual or family in the 95 th or 99 th percentile are in any way part of mainstream America, even if many of them think so: over a third of the demonstrators on the May Day ‘Occupy’ march in 2011 had annual earnings of more than $100,000 .

For others, the most important division is at the other end of the spectrum: the poverty line. The poor have not fallen behind the middle class in recent decades. But they have not caught up either. There is a case to be made that whatever is happening towards the top of the distribution, the gap we should care most about is between families struggling to put food on the table and those with adequate, middling incomes.

This may be right. But two points are worth making. First, it is vitally important for policy analysts and policy makers to at least be clear about their primary concern. If reducing poverty is the goal, then it should be made explicit, rather than confusing it with reducing inequality—especially given that a good deal ( though not all ) of the motive force behind contemporary inequality is gap towards the top. Of course, both objectives can be pursued at the same time. But we need to be clear that they are distinct.

Second, we should be attentive to role of biography. Most journalists, scholars and policy wonks are members of the upper middle class. This undoubtedly influences their (OK, our ) treatment of inequality. Those of us in the upper middle class typically find it more comfortable to examine the problems of inequality way up into the stratosphere of the super-rich, or towards the bottom of the pile among families in poverty or with low incomes. It is discomfiting to think that the inequality problem may be closer to home.

Defining the upper middle class

Class is a slippery concept, especially in a society that likes to think of itself as classless—or, more precisely, one in which everyone likes to think of themselves as middle class. In 2014, 85 percent of U.S. adults described themselves as ‘middle class’; a figure essentially unchanged since 1939, when a Gallup poll found that 88 percent described themselves in the same way.

Given that almost all Americans are middle class, the most important distinctions occur within that broad group. Only a tiny proportion—1 percent or 2 percent—is ever willing to label itself ‘upper class.’ But a significant minority adopts the ‘upper middle class’ description: 13 percent in the most recent poll, down from 19 percent captured in 2008:

These numbers are in fact quite similar to those generated by most sociologists, who have a leaning towards occupational status, and who typically define the upper middle class as comprising professionals and managers, around 15-20 percent of the working-age population.

Income provides a cleaner instrument with which to dissect the distribution, however, since it is easier to track over time and compare objectively. Income is also an example of what the philosopher Joseph Fishkin describes as an ‘instrumental good,’ bringing other benefits along with it.

Class is of course made up of a subtle, shifting blend of economic, social, education and attitudinal factors. But for my purposes, an income-based classification will provide a good starting point, not least because the trends in income inequality are fairly clear: the top fifth is pulling away from the rest of society.

In this first memo, I present some descriptive data for three groups:

- Upper middle class (top 20 percent by family income)

- Middle ‘half’ (the next two quintiles down, i.e. 40 percent)

- Bottom ‘half’ (the bottom two quintiles, i.e. 40 percent)

People tend to have higher incomes as they get older (at least until retirement). We therefore have to be careful not to confuse cohort effects with real trends. For this reason, wherever possible and appropriate, we have constructed our income quintiles for a narrow age range (mostly 35 to 40).

Upper middle class incomes: On the up

There is plenty of argument about the extent of inequality. But nobody questions the fact that in recent decades, incomes in the upper middle class are rising relative to the rest of the distribution. Families in the top quintile receive about half of overall income:

Upper middle class families have seen much stronger growth in real incomes in recent decades:

It is also true that there is growing inequality within the top quintile. Indeed, the higher up the distribution, the greater the rise in inequality. This is true even within the top 1 percent , where it is the top 0.1 percent or even 0.01 percent who are seeing the fastest lift-off in income.

“Where did you get your second degree?” The upper middle class and education

The upper middle class is pulling away economically. But class is not just about money. Education is an important ingredient, too. A higher level of education tends to be associated with greater occupational prestige and autonomy, as well as job quality and security. It is also worth remembering, even in this instrumental age, that education is a good in itself.

Given the strong association between education and earnings, it is hardly a surprise that the adults in the families in the top income quintile tend to have higher levels of education. A quarter of household heads have a postgraduate or professional qualification, a third have a four-year degree, and most of the rest have at least some college education:

In recent decades, the labor market returns to education have risen. Other things equal, this should tighten the relationship between family income status and education attainment: in other words, an upper middle class income and an upper middle class education will go together even more often.

A simple way to test this is to look at the correlation between being in the top income quintile and meeting certain education benchmarks. We correlate top quintile income status with three education measures: years of schooling, level of educational attainment, and being in the top quintile of the educational distribution. An advantage of the third is that it is a purely relative measure, and so is not influenced by rising overall education levels.

As expected, the association between education and a high family income has tightened over time. The trend is less strong for the years of schooling measure, almost certainly because of the significant increase in high school graduation rates. But it is clear that those with high education levels now have an even better chance of also having a high family income. (Education is such a big part of the upper middle class separation story, not least in terms of intergenerational transmission, that it will receive special attention in a future Memo in this series.) When different dimensions of advantage cluster together more tightly, the separation of the upper middle class becomes sharper: just as the clustering of disadvantages amplifies the effect of poverty.

Families, marriage, and social class

American society is divided along economic and educational lines, but also on the fault-line of the family. There is a much-discussed ‘marriage gap’ between affluent, well-educated Americans and their less-advantaged peers. Families in the top income quintile are much more likely to feature a married couple than those lower down the distribution. Of course, the fact of being married helps to push up family income, since two adults have twice the earnings potential. Nonetheless, the gaps by income in family structure are striking. There are more never-married than married adults (aged 35 to 40) in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution (37 percent v. 33 percent). In the top quintile, the picture is reversed: a large majority of household heads (83 percent) are married, while just 11 percent have never been married:

In itself, the relationship between upper middle class status and family structure may seem of little concern. Whether people choose to marry or not is a personal choice. But family structure, as a marker and predictor of family stability, makes a difference to the life chances of the next generation. To the extent that upper middle class Americans are able to form planned, stable, committed families, their children will benefit—and be more likely to retain their childhood class status when they become adults.

Voting and attitudes

There is a great deal of concern about the impact of the super-rich on American politics, and rightly so: read Darrell West’s book Billionaires for a balanced account. But while the Trumps and Kochs and Buffetts have the money to fund presidential campaigns, the upper middle class have plenty of political clout, too. They vote, they organize, they lobby, they complain: and their voices are heard. It is an established fact that those with higher incomes are more likely to vote. In 2012, three out of four top-income household heads voted, compared to just half of those towards the bottom (note these are not precisely the same cut-offs as the income quintiles):

The upper middle class are also more likely to believe in the American Dream that hard work gets you ahead, no doubt in part because they believe, rightly or wrongly, that the statement applies to themselves:

An upper middle class status is likely to be both a cause and consequence of a high degree of self- confidence and ability to navigate the complexities of the world. As the famous Chicago advice columnist Ann Landers once wrote, “Class is an aura of confidence that is being sure without being cocky. Class has nothing to do with money. Class never runs scared. It is self-discipline and self-knowledge.”

Survey data provides some support for the Landers ‘aura of confidence’ thesis. There are large differences in the extent to which individuals at different points on the income scale feel comfortable with the pace of change:

In fact, between the mid-1970s and the end of the 20 th century, members of the upper middle class seem if anything to have become more relaxed about the changes in the world around them. (Note: we have not yet been able to access more recent data on this question.)

The writer and scholar Reihan Salam has developed some downbeat views about the upper middle class. Writing in Slate , he despairs that “though many of the upper-middle-class individuals I’ve come to know are good, decent people, I’ve come to the conclusion that upper-middle-class Americans threaten to destroy everything that is best in our country.”

Hyperbole, of course. But there is certainly cause for concern. Salam points to the successful rebellion against President Obama’s plans to curb 529 college savings plans, which essentially amount to a tax giveaway to the upper middle class. While the politics of the reform were badly bungled, it was indeed a reminder that the American upper middle class knows how to take care of itself. Efforts to increase redistribution, or loosen licensing laws, or free up housing markets, or reform school admissions can all run into the solid wall of rational, self-interested upper middle class resistance. This is when the separation of the upper middle class shifts from being a sociological curiosity to an economic and political problem.

In the long run, an even bigger threat might be posed by the perpetuation of upper middle class status over the generations. There is intergenerational ‘stickiness’ at the bottom of the income distribution; but there is at least as much at the other end, and some evidence that the U.S. shows particularly low rates of downward mobility from the top. When status becomes more strongly inherited, inequality hardens into stratification, open societies start to close up, and class distinctions sharpen.

Economic Studies

Center for Economic Security and Opportunity

Joseph Parilla, Glencora Haskins, Mark Muro

May 21, 2024

Robert Maxim

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Social Class — Gregory Mantsios Class in America Analysis

Gregory Mantsios Class in America Analysis

- Categories: American Culture Culture Shock Social Class

About this sample

Words: 522 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 522 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Debunking the myth of meritocracy, the role of media, impact of social class on healthcare.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1046 words

2 pages / 980 words

8 pages / 3854 words

2 pages / 1115 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Social Class

The relationship between language and social class is a complex and multifaceted one, underscoring the ways in which language can both reflect and perpetuate societal hierarchies. Language serves as a vehicle for communication, [...]

Eileen Chang’s short story “Sealed Off” is a powerful exploration of the impact of war and political turmoil on the lives of ordinary people. Set during the Second Sino-Japanese War, the story takes place in Shanghai, a city [...]

Hurstcote is a novel written by E. Nesbit, published in 1900. The novel revolves around the theme of the impact of social class on individual lives and relationships. The story follows the life of a young woman named Agatha, who [...]

Social class is a central theme in Marjane Satrapi's graphic novel, Persepolis. It is a complex and multifaceted issue that is depicted through a range of characters and situations. Through Satrapi's use of characterisation, [...]

Society is divided and stratified by race, gender, sexuality, as well as by class. This stratification is everlasting, generating and repeating, usually leading to inequality. In a rapid and modernised society, social class is [...]

Stereotypes are pervasive in society, influencing how we perceive and interact with others. They are preconceived notions or beliefs about certain groups of people, often based on limited or inaccurate information. Social class [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen Essay

Chapter 4 of the book “The Family” by Philip N Cohen discusses the relationship between families and social class. The chapter explores the six classes that make up the American class system, which ranges from higher to lower classes. The most wealthy and influential people belong to the upper class, whereas skilled laborers and white-collar professionals make up the middle class and contribute to societal stratification. The working class is composed of blue-collar workers, while the lower class is made up of those who are living in poverty.

Class persistence refers to a person’s propensity to stay in the same social class as their parents, while social mobility refers to a person’s ability to advance or regress along the social class spectrum. The chapter examines the elements that affect social mobility, such as wealth, employment, and education, and how social networks can help or impede it. The chapter also highlights the impact of social class on family dynamics, such as how parents raise their kids and the beliefs and perspectives handed down through the generations. It also discusses how social class affects families’ access to resources and opportunities, such as healthcare, education, and housing.

In conclusion, Chapter 4 provides an overview of the theories of the American class structure, social class, the American class structure, mobility, and persistence, as well as the impact of social class on family dynamics and access to resources. This chapter’s keywords include power, social class, prestige, wealth, social mobility, occupation, social stratification, and class persistence. Understanding how families and social class interact in American culture requires understanding these words.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 9). Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen. https://ivypanda.com/essays/families-and-social-classes-in-america/

"Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen." IvyPanda , 9 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/families-and-social-classes-in-america/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen'. 9 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen." February 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/families-and-social-classes-in-america/.

1. IvyPanda . "Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen." February 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/families-and-social-classes-in-america/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Families and Social Class: Chapter 4 of “The Family” by Philip N. Cohen." February 9, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/families-and-social-classes-in-america/.

- Pink-Collar Criminal: Gender in White-Collar Crime

- Chapter 3 of “The Family” Book by Philip N. Cohen

- Knowledge Existence for Skepticism

- American Values: The Pursuit of Success

- Equality of Opportunity in Society

- Body Positivity: The Issue of Fatphobia

- The Aging Population's Retirement Security

- Cultural Analysis of PETA Commercial

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.5A: Consequences of Social Class

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 8219

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

One’s position in the the social class hierarchy has far-reaching effects on their health, family life, education, etc.

Learning Objectives

- Describe how socioeconomic status (SES) relates to the distributiuon of social opportunities and resources

- While sociologists debate exactly how social classes are divided, there is substantial evidence that socioeconomic status is tied to tangible advantages and outcomes.

- Social class in the United States is a controversial issue, with social scientists disagreeing over models, definitions, and even the basic question of whether or not distinct classes exist.

- Many Americans believe in a simple three-class model that includes the rich or upper class, the middle class, and the poor or working class.

- hierarchy : Any group of objects ranked so that everyone but the topmost is subordinate to a specified group above it.

- socioeconomic : Of or pertaining to social and economic factors.

In the United States, a person’s social class has far-reaching consequences. Social class refers to the the grouping of individuals in a stratified hierarchy based on wealth, income, education, occupation, and social network (though other factors are sometimes considered). One’s position in the social class hierarchy may impact, for example, health, family life, education, religious affiliation, political participation, and experience with the criminal justice system.

Social class in the United States is a controversial issue, with social scientists disagreeing over models, definitions, and even the basic question of whether or not distinct classes exist. Many Americans believe in a simple three-class model that includes the rich or upper class, the middle class, and the poor or working class. More complex models that have been proposed by social scientists describe as many as a dozen class levels. Regardless of which model of social classes used, it is clear that socioeconomic status (SES) is tied to particular opportunities and resources. Socioeconomic status refers to a person’s position in the social hierarchy and is determined by their income, wealth, occupational prestige, and educational attainment.

While social class may be an amorphous and diffuse concept, with scholars disagreeing over its definition, tangible advantages are associated with high socioeconomic status. People in the highest SES bracket, generally referred to as the upper class, likely have better access to healthcare, marry people of higher social status, attend more prestigious schools, and are more influential in politics than people in the middle class or working class. People in the upper class are members of elite social networks, effectively meaning that they have access to people in powerful positions who have specialized knowledge. These social networks confer benefits ranging from advantages in seeking education and employment to leniency by police and the courts. Sociologists may dispute exactly how to model the distinctions between socioeconomic statuses, but the higher up the class hierarchy one is in America, the better health, educational, and professional outcomes one is likely to have.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

The psychology of social class: How socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour

Antony s. r. manstead.

1 Cardiff University, UK

Drawing on recent research on the psychology of social class, I argue that the material conditions in which people grow up and live have a lasting impact on their personal and social identities and that this influences both the way they think and feel about their social environment and key aspects of their social behaviour. Relative to middle‐class counterparts, lower/working‐class individuals are less likely to define themselves in terms of their socioeconomic status and are more likely to have interdependent self‐concepts; they are also more inclined to explain social events in situational terms, as a result of having a lower sense of personal control. Working‐class people score higher on measures of empathy and are more likely to help others in distress. The widely held view that working‐class individuals are more prejudiced towards immigrants and ethnic minorities is shown to be a function of economic threat, in that highly educated people also express prejudice towards these groups when the latter are described as highly educated and therefore pose an economic threat. The fact that middle‐class norms of independence prevail in universities and prestigious workplaces makes working‐class people less likely to apply for positions in such institutions, less likely to be selected and less likely to stay if selected. In other words, social class differences in identity, cognition, feelings, and behaviour make it less likely that working‐class individuals can benefit from educational and occupational opportunities to improve their material circumstances. This means that redistributive policies are needed to break the cycle of deprivation that limits opportunities and threatens social cohesion.

We are all middle class now. John Prescott, former Labour Deputy Prime Minister, 1997

Class is a Communist concept. It groups people as bundles and sets them against one another. Margaret Thatcher, former Conservative Prime Minister, 1992

One of the ironies of modern Western societies, with their emphasis on meritocratic values that promote the notion that people can achieve what they want if they have enough talent and are prepared to work hard, is that the divisions between social classes are becoming wider, not narrower. In the United Kingdom, for example, figures from the Equality Trust ( 2017 ) show that the top one‐fifth of households have 40% of national income, whereas the bottom one‐fifth have just 8%. These figures are based on 2012 data. Between 1938 and 1979, income inequality in the United Kingdom did reduce to some extent, but in subsequent decades, this process has reversed. Between 1979 and 2009/2010, the top 10% of the population increased its share of national income from 21% to 31%, whereas the share received by the bottom 10% fell from 4% to 1%. Wealth inequality is even starker than income inequality. Figures from the UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2014 ) show that in the period 2012–2014, the wealthiest 10% of households in Great Britain owned 45% of household wealth, whereas the least wealthy 50% of households owned <9%. How can these very large divisions in material income and wealth be reconciled with the view that the class structure that used to prevail in the United Kingdom until at least the mid‐20th century is no longer relevant, because the traditional working class has ‘disappeared’, as asserted by John Prescott in one of the opening quotes, and reflected in the thesis of embourgeoisement analysed by Goldthorpe and Lockwood ( 1963 )? More pertinently for the present article, what implications do these changing patterns of wealth and income distribution have for class identity, social cognition, and social behaviour?

The first point to address concerns the supposed disappearance of the class system. As recent sociological research has conclusively shown, the class system in the United Kingdom is very much still in existence, albeit in a way that differs from the more traditional forms that were based primarily on occupation. In one of the more comprehensive recent studies, Savage et al . ( 2013 ) analysed the results of a large survey of social class in the United Kingdom, the BBC's 2011 Great British Class Survey, which involved 161,400 web respondents, along with the results of a nationally representative sample survey. Using latent class analysis, the authors identified seven classes, ranging from an ‘elite’, with an average annual household income of £89,000, to a ‘precariat’ with an average annual household income of £8,000. Among the many interesting results is the fact that the ‘traditional working‐class’ category formed only 14% of the population. This undoubtedly reflects the impact of de‐industrialization and is almost certainly the basis of the widely held view that the ‘old’ class system in the United Kingdom no longer applies. As Savage et al .'s research clearly shows, the old class system has been reconfigured as a result of economic and political developments, but it is patently true that the members of the different classes identified by these researchers inhabit worlds that rarely intersect, let alone overlap. The research by Savage et al . revealed that the differences between the social classes they identified extended beyond differences in financial circumstances. There were also marked differences in social and cultural capital, as indexed by size of social network and extent of engagement with different cultural activities, respectively. From a social psychological perspective, it seems likely that growing up and living under such different social and economic contexts would have a considerable impact on people's thoughts, feelings and behaviours. The central aim of this article was to examine the nature of this impact.

One interesting reflection of the complicated ways in which objective and subjective indicators of social class intersect can be found in an analysis of data from the British Social Attitudes survey (Evans & Mellon, 2016 ). Despite the fact that there has been a dramatic decline in traditional working‐class occupations, large numbers of UK citizens still describe themselves as being ‘working class’. Overall, around 60% of respondents define themselves as working class, and the proportion of people who do so has hardly changed during the past 33 years. One might reasonably ask whether and how much it matters that many people whose occupational status suggests that they are middle class describe themselves as working class. Evans and Mellon ( 2016 ) show quite persuasively that this self‐identification does matter. In all occupational classes other than managerial and professional, whether respondents identified themselves as working class or middle class made a substantial difference to their political attitudes, with those identifying as working class being less likely to be classed as right‐wing. No wonder Margaret Thatcher was keen to dispense with the concept of class, as evidenced by the quotation at the start of this paper. Moreover, self‐identification as working class was significantly associated with social attitudes in all occupational classes. For example, these respondents were more likely to have authoritarian attitudes and less likely to be in favour of immigration, a point I will return to later. It is clear from this research that subjective class identity is linked to quite marked differences in socio‐political attitudes.

A note on terminology

In what follows, I will refer to a set of concepts that are related but by no means interchangeable. As we have already seen, there is a distinction to be drawn between objective and subjective indicators of social class. In Marxist terms, class is defined objectively in terms of one's relationship to the means of production. You either have ownership of the means of production, in which case you belong to the bourgeoisie, or you sell your labour, in which case you belong to the proletariat, and there is a clear qualitative difference between the two classes. This worked well when most people could be classified either as owners or as workers. As we have seen, such an approach has become harder to sustain in an era when traditional occupations have been shrinking or have already disappeared, a sizeable middle‐class of managers and professionals has emerged, and class divisions are based on wealth and social and cultural capital.

An alternative approach is one that focuses on quantitative differences in socioeconomic status (SES), which is generally defined in terms of an individual's economic position and educational attainment, relative to others, as well as his or her occupation. As will be shown below, when people are asked about their identities, they think more readily in terms of SES than in terms of social class. This is probably because they have a reasonable sense of where they stand, relative to others, in terms of economic factors and educational attainment, and perhaps recognize that traditional boundaries between social classes have become less distinct. For these reasons, much of the social psychological literature on social class has focused on SES as indexed by income and educational attainment, and/or on subjective social class, rather than social class defined in terms of relationship to the means of production. For present purposes, the terms ‘working class’, which tends to be used more by European researchers, and ‘lower class’, which tends to be used by US researchers, are used interchangeably. Similarly, the terms ‘middle class’ and ‘upper class’ will be used interchangeably, despite the different connotations of the latter term in the United States and in Europe, where it tends to be reserved for members of the land‐owning aristocracy. A final point about terminology concerns ‘ideology’, which will here be used to refer to a set of beliefs, norms and values, examples being the meritocratic ideology that pervades most education systems and the (related) ideology of social mobility that is prominent in the United States.

Socioeconomic status and identity

Social psychological analyses of identity have traditionally not paid much attention to social class or SES as a component of identity. Instead, the focus has been on categories such as race, gender, sexual orientation, nationality and age. Easterbrook, Kuppens, and Manstead ( 2018 ) analysed data from two large, representative samples of British adults and showed that respondents placed high subjective importance on their identities that are indicative of SES. Indeed, they attached at least as much importance to their SES identities as they did to identities (such as ethnicity or gender) more commonly studied by self and identity researchers. Easterbrook and colleagues also showed that objective indicators of a person's SES were robust and powerful predictors of the importance they placed on different types of identities within their self‐concepts: Those with higher SES attached more importance to identities that are indicative of their SES position, but less importance on identities that are rooted in basic demographics or related to their sociocultural orientation (and vice versa).

To arrive at these conclusions, Easterbook and colleagues analysed data from two large British surveys: The Citizenship Survey (CS; Department for Communities and Local Government, 2012 ); and Understanding Society: The UK Household Longitudinal Study (USS; Buck & McFall, 2012 ). The CS is a (now discontinued) biannual survey of a regionally representative sample of around 10,000 adults in England and Wales, with an ethnic minority boost sample of around 5,000. The researchers analysed the most recent data, collected via interviews in 2010–2011. The USS is an annual longitudinal household panel survey that began in 2009. Easterbrook and colleagues analysed Wave 5 (2013–2014), the more recent of the two waves in which the majority of respondents answered questions relevant to class and other social identities.