- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2019

Evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings: protocol for systematic review

- Susan A. Rombouts 1 ,

- James Conigrave 2 ,

- Eva Louie 1 ,

- Paul Haber 1 , 3 &

- Kirsten C. Morley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0868-9928 1

Systematic Reviews volume 8 , Article number: 275 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

7423 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is highly prevalent and accounts globally for 1.6% of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) among females and 6.0% of DALYs among males. Effective treatments for AUDs are available but are not commonly practiced in primary health care. Furthermore, referral to specialized care is often not successful and patients that do seek treatment are likely to have developed more severe dependence. A more cost-efficient health care model is to treat less severe AUD in a primary care setting before the onset of greater dependence severity. Few models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care have been developed and with limited implementation. This proposed systematic review will synthesize and evaluate differential models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care settings.

We will conduct a systematic review to synthesize studies that evaluate the effectiveness of models of care in the treatment of AUD in primary health care. A comprehensive search approach will be conducted using the following databases; MEDLINE (1946 to present), PsycINFO (1806 to present), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1991 to present), and Embase (1947 to present).

Reference searches of relevant reviews and articles will be conducted. Similarly, a gray literature search will be done with the help of Google and the gray matter tool which is a checklist of health-related sites organized by topic. Two researchers will independently review all titles and abstracts followed by full-text review for inclusion. The planned method of extracting data from articles and the critical appraisal will also be done in duplicate. For the critical appraisal, the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2.0 will be used.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to guide improvement of design and implementation of evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings. The evidence will define which models are most promising and will guide further research.

Protocol registration number

PROSPERO CRD42019120293.

Peer Review reports

It is well recognized that alcohol use disorders (AUD) have a damaging impact on the health of the population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 5.3% of all global deaths were attributable to alcohol consumption in 2016 [ 1 ]. The 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study reported that alcohol use led to 1.6% (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 1.4–2.0) of total DALYs globally among females and 6.0% (5.4–6.7) among males, resulting in alcohol use being the seventh leading risk factor for both premature death and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [ 2 ]. Among people aged 15–49 years, alcohol use was the leading risk factor for mortality and disability with 8.9% (95% UI 7.8–9.9) of all attributable DALYs for men and 2.3% (2.0–2.6) for women [ 2 ]. AUD has been linked to many physical and mental health complications, such as coronary heart disease, liver cirrhosis, a variety of cancers, depression, anxiety, and dementia [ 2 , 3 ]. Despite the high morbidity and mortality rate associated with hazardous alcohol use, the global prevalence of alcohol use disorders among persons aged above 15 years in 2016 was stated to be 5.1% (2.5% considered as harmful use and 2.6% as severe AUD), with the highest prevalence in the European and American region (8.8% and 8.2%, respectively) [ 1 ].

Effective and safe treatment for AUD is available through psychosocial and/or pharmacological interventions yet is not often received and is not commonly practiced in primary health care. While a recent European study reported 8.7% prevalence of alcohol dependence in primary health care populations [ 4 ], the vast majority of patients do not receive the professional treatment needed, with only 1 in 5 patients with alcohol dependence receiving any formal treatment [ 4 ]. In Australia, it is estimated that only 3% of individuals with AUD receive approved pharmacotherapy for the disorder [ 5 , 6 ]. Recognition of AUD in general practice uncommonly leads to treatment before severe medical and social disintegration [ 7 ]. Referral to specialized care is often not successful, and those patients that do seek treatment are likely to have more severe dependence with higher levels of alcohol use and concurrent mental and physical comorbidity [ 4 ].

Identifying and treating early stage AUDs in primary care settings can prevent condition worsening. This may reduce the need for more complex and more expensive specialized care. The high prevalence of AUD in primary health care and the chronic relapsing character of AUD make primary care a suitable and important location for implementing evidence-based interventions. Successful implementation of treatment models requires overcoming multiple barriers. Qualitative studies have identified several of those barriers such as limited time, limited organizational capacity, fear of losing patients, and physicians feeling incompetent in treating AUD [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Additionally, a recent systematic review revealed that diagnostic sensitivity of primary care physicians in the identification of AUD was 41.7% and that only in 27.3% alcohol problems were recorded correctly in primary care records [ 11 ].

Several models for primary care have been created to increase identification and treatment of patients with AUD. Of those, the model, screening, brief interventions, and referral to specialized treatment for people with severe AUD (SBIRT [ 12 ]) is most well-known. Multiple systematic reviews exist, confirming its effectiveness [ 13 , 14 , 15 ], although implementation in primary care has been inadequate. Moreover, most studies have looked primarily at SBIRT for the treatment of less severe AUD [ 16 ]. In the treatment of severe AUD, efficacy of SBIRT is limited [ 16 ]. Additionally, many patient referred to specialized care often do not attend as they encounter numerous difficulties in health care systems including stigmatization, costs, lack of information about existing treatments, and lack of non-abstinence-treatment goals [ 7 ]. An effective model of care for improved management of AUD that can be efficiently implemented in primary care settings is required.

Review objective

This proposed systematic review will synthesize and evaluate differential models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care settings. We aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the models of care in increasing engagement and reducing alcohol consumption.

By providing this overview, we aim to guide improvement of design and implementation of evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings.

The systematic review is registered in PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42019120293) and the current protocol has been written according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) recommended for systematic reviews [ 17 ]. A PRISMA-P checklist is included as Additional file 1 .

Eligibility criteria

Criteria for considering studies for this review are classified by the following:

Study design

Both individualized and cluster randomized trials will be included. Masking of patients and/or physicians is not an inclusion criterion as it is often hard to accomplish in these types of studies.

Patients in primary health care who are identified (using screening tools or by primary health care physician) as suffering from AUD (from mild to severe) or hazardous alcohol drinking habits (e.g., comorbidity, concurrent medication use). Eligible patients need to have had formal assessment of AUD with diagnostic tools such as Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV/V) or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) and/or formal assessment of hazardous alcohol use assessed by the Comorbidity Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool (CARET) or the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test (AUDIT) and/or alcohol use exceeding guideline recommendations to reduce health risks (e.g., US dietary guideline (2015–2020) specifies excessive drinking for women as ≥ 4 standard drinks (SD) on any day and/or ≥ 8 SD per week and for men ≥ 5 SD on any day and/or ≥ 15 SD per week).

Studies evaluating models of care for additional diseases (e.g., other dependencies/mental health) other than AUD are included when they have conducted data analysis on the alcohol use disorder patient data separately or when 80% or more of the included patients have AUD.

Intervention

The intervention should consist of a model of care; therefore, it should include multiple components and cover different stages of the care pathway (e.g., identification of patients, training of staff, modifying access to resources, and treatment). An example is the Chronic Care Model (CCM) which is a primary health care model designed for chronic (relapsing) conditions and involves six elements: linkage to community resources, redesign of health care organization, self-management support, delivery system redesign (e.g., use of non-physician personnel), decision support, and the use of clinical information systems [ 18 , 19 ].

As numerous articles have already assessed the treatment model SBIRT, this model of care will be excluded from our review unless the particular model adds a specific new aspect. Also, the article has to assess the effectiveness of the model rather than assessing the effectiveness of the particular treatment used. Because identification of patients is vital to including them in the trial, a care model that only evaluates either patient identification or treatment without including both will be excluded from this review.

Model effectiveness may be in comparison with the usual care or a different treatment model.

Included studies need to include at least one of the following outcome measures: alcohol consumption, treatment engagement, uptake of pharmacological agents, and/or quality of life.

Solely quantitative research will be included in this systematic review (e.g., randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster RCTs). We will only include peer-reviewed articles.

Restrictions (language/time period)

Studies published in English after 1 January 1998 will be included in this systematic review.

Studies have to be conducted in primary health care settings as such treatment facilities need to be physically in or attached to the primary care clinic. Examples are co-located clinics, veteran health primary care clinic, hospital-based primary care clinic, and community primary health clinics. Specialized primary health care clinics such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) clinics are excluded from this systematic review. All studies were included, irrespective of country of origin.

Search strategy and information sources

A comprehensive search will be conducted. The following databases will be consulted: MEDLINE (1946 to present), PsycINFO (1806 to present), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1991 to present), and Embase (1947 to present). Initially, the search terms will be kept broad including alcohol use disorder (+synonyms), primary health care, and treatment to minimize the risk of missing any potentially relevant articles. Depending on the number of references attained by this preliminary search, we will add search terms referring to models such as models of care, integrated models, and stepped-care models, to limit the number of articles. Additionally, we will conduct reference searches of relevant reviews and articles. Similarly, a gray literature search will be done with the help of Google and the Gray Matters tool which is a checklist of health-related sites organized by topic. The tool is produced by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) [ 20 ].

See Additional file 2 for a draft of our search strategy in MEDLINE.

Data collection

The selection of relevant articles is based on several consecutive steps. All references will be managed using EndNote (EndNote version X9 Clarivate Analytics). Initially, duplicates will be removed from the database after which all the titles will be screened with the purpose of discarding clearly irrelevant articles. The remaining records will be included in an abstract and full-text screen. All steps will be done independently by two researchers. Disagreement will lead to consultation of a third researcher.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two researchers will extract data from included records. At the conclusion of data extraction, these two researchers will meet with the lead author to resolve any discrepancies.

In order to follow a structured approach, an extraction form will be used. Key elements of the extraction form are information about design of the study (randomized, blinded, control), type of participants (alcohol use, screening tool used, socio-economic status, severity of alcohol use, age, sex, number of participants), study setting (primary health care setting, VA centers, co-located), type of intervention/model of care (separate elements of the models), type of health care worker (primary, secondary (co-located)), duration of follow-up, outcome measures used in the study, and funding sources. We do not anticipate having sufficient studies for a meta-analysis. As such, we plan to perform a narrative synthesis. We will synthesize the findings from the included articles by cohort characteristics, differential aspects of the intervention, controls, and type of outcome measures.

Sensitivity analyses will be conducted when issues suitable for sensitivity analysis are identified during the review process (e.g., major differences in quality of the included articles).

Potential meta-analysis

In the event that sufficient numbers of effect sizes can be extracted, a meta-analytic synthesis will be performed. We will extract effect sizes from each study accordingly. Two effect sizes will be extracted (and transformed where appropriate). Categorical outcomes will be given in log odds ratios and continuous measures will be converted into standardized mean differences. Variation in effect sizes attributable to real differences (heterogeneity) will be estimated using the inconsistency index ( I 2 ) [ 21 , 22 ]. We anticipate high degrees of variation among effect sizes, as a result moderation and subgroup-analyses will be employed as appropriate. In particular, moderation analysis will focus on the degree of heterogeneity attributable to differences in cohort population (pre-intervention drinking severity, age, etc.), type of model/intervention, and study quality. We anticipate that each model of care will require a sub-group analysis, in which case a separate meta-analysis will be performed for each type of model. Small study effect will be assessed with funnel plots and Egger’s symmetry tests [ 23 ]. When we cannot obtain enough effect sizes for synthesis or when the included studies are too diverse, we will aim to illustrate patterns in the data by graphical display (e.g., bubble plot) [ 24 ].

Critical appraisal of studies

All studies will be critically assessed by two researchers independently using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (RoB 2) [ 25 ]. This tool facilitates systematic assessment of the quality of the article per outcome according to the five domains: bias due to (1) the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, and (5) selection of the reported results. An additional domain 1b must be used when assessing the randomization process for cluster-randomized studies.

Meta-biases such as outcome reporting bias will be evaluated by determining whether the protocol was published before recruitment of patients. Additionally, trial registries will be checked to determine whether the reported outcome measures and statistical methods are similar to the ones described in the registry. The gray literature search will be of assistance when checking for publication bias; however, completely eliminating the presence of publication bias is impossible.

Similar to article selection, any disagreement between the researchers will lead to discussion and consultation of a third researcher. The strength of the evidence will be graded according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [ 26 ].

The primary outcome measure of this proposed systematic review is the consumption of alcohol at follow-up. Consumption of alcohol is often quantified in drinking quantity (e.g., number of drinks per week), drinking frequency (e.g., percentage of days abstinent), binge frequency (e.g., number of heavy drinking days), and drinking intensity (e.g., number of drinks per drinking day). Additionally, outcomes such as percentage/proportion included patients that are abstinent or considered heavy/risky drinkers at follow-up. We aim to report all these outcomes. The consumption of alcohol is often self-reported by patients. When studies report outcomes at multiple time points, we will consider the longest follow-up of individual studies as a primary outcome measure.

Depending on the included studies, we will also consider secondary outcome measures such as treatment engagement (e.g., number of visits or pharmacotherapy uptake), economic outcome measures, health care utilization, quality of life assessment (physical/mental), alcohol-related problems/harm, and mental health score for depression or anxiety.

This proposed systematic review will synthesize and evaluate differential models of care for the management of AUD in primary health care settings.

Given the complexities of researching models of care in primary care and the paucity of a focus on AUD treatment, there are likely to be only a few studies that sufficiently address the research question. Therefore, we will do a preliminary search without the search terms for model of care. Additionally, the search for online non-academic studies presents a challenge. However, the Gray Matters tool will be of guidance and will limit the possibility of missing useful studies. Further, due to diversity of treatment models, outcome measures, and limitations in research design, it is possible that a meta-analysis for comparative effectiveness may not be appropriate. Moreover, in the absence of large, cluster randomized controlled trials, it will be difficult to distinguish between the effectiveness of the treatment given and that of the model of care and/or implementation procedure. Nonetheless, we will synthesize the literature and provide a critical evaluation of the quality of the evidence.

This review will assist the design and implementation of models of care for the management of AUD in primary care settings. This review will thus improve the management of AUD in primary health care and potentially increase the uptake of evidence-based interventions for AUD.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Alcohol use disorder

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification test

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

The Comorbidity Alcohol Risk Evaluation

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Human immunodeficiency virus

10 - International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols

Screening, brief intervention, referral to specialized treatment

Standard drinks

World Health Organization

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health: World health organization; 2018.

The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):987–1012.

Article Google Scholar

WHO. Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol: World health organization; 2010.

Rehm J, Allamani A, Elekes Z, Jakubczyk A, Manthey J, Probst C, et al. Alcohol dependence and treatment utilization in Europe - a representative cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:90.

Morley KC, Logge W, Pearson SA, Baillie A, Haber PS. National trends in alcohol pharmacotherapy: findings from an Australian claims database. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166:254–7.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Morley KC, Logge W, Pearson SA, Baillie A, Haber PS. Socioeconomic and geographic disparities in access to pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;74:23–5.

Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, Shield KD, Struzzo P, Wojnar M, et al. Alcohol use disorders in primary health care: what do we know and where do we go? Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(4):422–7.

Le KB, Johnson JA, Seale JP, Woodall H, Clark DC, Parish DC, et al. Primary care residents lack comfort and experience with alcohol screening and brief intervention: a multi-site survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):790–6.

McLellan AT, Starrels JL, Tai B, Gordon AJ, Brown R, Ghitza U, et al. Can substance use disorders be managed using the chronic care model? review and recommendations from a NIDA consensus group. Public Health Rev. 2014;35(2).

Storholm ED, Ober AJ, Hunter SB, Becker KM, Iyiewuare PO, Pham C, et al. Barriers to integrating the continuum of care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: a qualitative longitudinal study. J Subst Abus Treat. 2017;83:45–54.

Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Bird V, Rizzo M. Clinical recognition and recording of alcohol disorders by clinicians in primary and secondary care: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:93–100.

Babor TF, Ritson EB, Hodgson RJ. Alcohol-related problems in the primary health care setting: a review of early intervention strategies. Br J Addict. 1986;81(1):23–46.

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):Cd004148.

O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, Schulte B, Schmidt C, Reimer J, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49(1):66–78.

Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(9):986–95.

Saitz R. ‘SBIRT’ is the answer? Probably not. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1416–7.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Bmj. 2015;350:g7647.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. Jama. 2002;288(14):1775–9.

Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. Jama. 2002;288(15):1909–14.

CADTH. Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature Internet. 2018 (cited 2019 Feb 22).

Higgins JPT. Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Google Scholar

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ. Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Higgins JPT, López-López JA, Becker BJ, Davies SR, Dawson S, Grimshaw JM, et al. Synthesising quantitative evidence in systematic reviews of complex health interventions. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(Suppl 1):e000858–e.

Higgins, J.P.T., Sterne, J.A.C., Savović, J., Page, M.J., Hróbjartsson, A., Boutron, I., Reeves, B., Eldridge, S. (2016). A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. In: Chandler, J., McKenzie, J., Boutron, I., Welch, V. (editors). Cochrane methods. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 10 (Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD201601 .

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editor(s). Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach (updated October 2013). GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/handbook.html ).

Download references

Acknowledgements

There is no dedicated funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Discipline of Addiction Medicine, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Susan A. Rombouts, Eva Louie, Paul Haber & Kirsten C. Morley

NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Indigenous Health and Alcohol, Central Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

James Conigrave

Drug Health Services, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, NSW, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KM and PH conceived the presented idea of a systematic review and meta-analysis and helped with the scope of the literature. KM is the senior researcher providing overall guidance and the guarantor of this review. SR developed the background, search strategy, and data extraction form. SR and EL will both be working on the data extraction and risk of bias assessment. SR and JC will conduct the data analysis and synthesize the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kirsten C. Morley .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

PRISMA-P 2015 Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Draft search strategy MEDLINE. Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rombouts, S.A., Conigrave, J., Louie, E. et al. Evidence-based models of care for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary health care settings: protocol for systematic review. Syst Rev 8 , 275 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1157-7

Download citation

Received : 25 March 2019

Accepted : 13 September 2019

Published : 13 November 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1157-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Model of care

- Primary health care

- Systematic review

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- June 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 6 CURRENT ISSUE pp.461-564

- May 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 5 pp.347-460

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions

Maladaptive substance use and substance use disorders are highly prevalent and are among the most significant public health problems. Substance use is commonly comorbid with psychiatric disorders, and treatment efforts need to concurrently address both. The papers in this issue highlight new findings that are directly relevant to understanding, treating, and developing policies to better serve those afflicted with addictions. While treatments exist, the need for more effective treatments is clear, especially those focused on decreasing relapse rates. The negative affective state, hyperkatifeia, that accompanies longer-term abstinence is an important treatment target that should be emphasized in current practice as well as in new treatment development. In addition to developing a better understanding of the neurobiology of addictions and abstinence, it is necessary to ensure that there is equitable access to currently available treatments and treatment programs. Additional resources must be allocated to this cause. This depends on the recognition that health care inequities and societal barriers are major contributors to the continued high prevalence of substance use disorders, the individual suffering they inflict, and the huge toll that they incur at a societal level.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 US Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018. Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019 ( https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH ) Google Scholar

2 Koob GF, Powell P, White A : Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1031–1037 Link , Google Scholar

3 Cassidy CM, Carpenter KM, Konova AB, et al. : Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1038–1047 Link , Google Scholar

4 Bradberry CW : Neuromelanin MRI: dark substance shines a light on dopamine dysfunction and cocaine use (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1019–1021 Abstract , Google Scholar

5 Blaine SK, Wemm S, Fogelman N, et al. : Association of prefrontal-striatal functional pathology with alcohol abstinence days at treatment initiation and heavy drinking after treatment initiation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1048–1059 Link , Google Scholar

6 Sullivan EV : Why timing matters in alcohol use disorder recovery (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1022–1024 Abstract , Google Scholar

7 Lees B, Mewton L, Jacobus J, et al. : Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with psychological, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1060–1072 Link , Google Scholar

8 McCormack C, Monk C : Considering prenatal alcohol exposure in a developmental origins of health and disease framework (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1025–1028 Abstract , Google Scholar

9 Evans-Polce RJ, Kcomt L, Veliz PT, et al. : Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1073–1081 Abstract , Google Scholar

10 Grant BF, Shmulewitz D, Compton WM : Nicotine use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1082–1090 Link , Google Scholar

11 Brady KT : Social determinants of health and smoking cessation: a challenge (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1029–1030 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 28 May 2024

Associations of semaglutide with incidence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder in real-world population

- William Wang 1 ,

- Nora D. Volkow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6668-0908 2 ,

- Nathan A. Berger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7086-9885 1 ,

- Pamela B. Davis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7113-5338 3 ,

- David C. Kaelber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7855-9515 4 &

- Rong Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3127-4795 5

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 4548 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

7884 Accesses

236 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Clinical pharmacology

- Drug safety

- Therapeutics

Alcohol use disorders are among the top causes of the global burden of disease, yet therapeutic interventions are limited. Reduced desire to drink in patients treated with semaglutide has raised interest regarding its potential therapeutic benefits for alcohol use disorders. In this retrospective cohort study of electronic health records of 83,825 patients with obesity, we show that semaglutide compared with other anti-obesity medications is associated with a 50%-56% lower risk for both the incidence and recurrence of alcohol use disorder for a 12-month follow-up period. Consistent reductions were seen for patients stratified by gender, age group, race and in patients with and without type 2 diabetes. Similar findings are replicated in the study population with 598,803 patients with type 2 diabetes. These findings provide evidence of the potential benefit of semaglutide in AUD in real-world populations and call for further randomized clinicl trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Long-term weight loss effects of semaglutide in obesity without diabetes in the SELECT trial

Divergent age-associated and metabolism-associated gut microbiome signatures modulate cardiovascular disease risk

Introduction.

An estimated 29.5 million or 10.6% of Americans ages 12 and older had an alcohol use disorder (AUD) in 2021 1 . AUD, which is responsible for more than 80,000 annual deaths in the USA is among the top 10 conditions associated with the largest global burden of disease 2 . Despite its large public health impact, there are only 3 medications for AUD approved by the FDA and 4 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and their therapeutic benefits are modest 3 , 4 . Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new medication for treating AUD.

Recent reports of reduced drinking in people being treated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA) medications for T2DM or obesity have generated interest in the potential of these medications for treating AUD 5 , 6 . In particular semaglutide, a GLP-1RA approved for treating type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in 2017 and obesity in 2021, reduced drinking and relapse in alcohol-dependent rodents 7 , 8 . Anecdotal reports from patients prescribed semaglutide describe a reduced desire to drink 9 that have been subsequently corroborated by a report of reduced alcohol drinking with semaglutide and tirzepatide based on analyses of social media texts and follow up of selected participants 10 and a case series reporting decreased symptoms of AUD in patients treated with semaglutide 11 . Moreover, a small clinical trial ( n = 127) that evaluated the GLP-1RA agonist exenatide compared to placebo as an adjunct to standard cognitive-behavioral therapy, reported that exenatide significantly reduced heavy drinking days and total alcohol intake in a subgroup of patients with obesity 12 . However, as of now information on the clinical benefits of semaglutide for AUD prevention and treatment in real-world populations is still very limited. Here we took advantage of a large database of patient electronic health records (EHRs) to conduct a nationwide multicenter retrospective cohort study to assess the association of semaglutide with both the incidence and recurrence of AUD in individuals with obesity and with and without a prior history of AUD. We assessed the reproducibility of the findings in a separate cohort of patients with T2DM from non-overlapping time periods. We also compared patients who suffered from obesity who had T2DM (~33%) and those who did not (~67%); as well as patients with T2DM who suffered from obesity (~40%) and those who did not (~60%), to evaluate if there were potential interactions on the effects of semaglutide in patients with these two co-morbid conditions. Outcomes were separately evaluated by age, sex, and race.

Association of semaglutide with incident AUD diagnosis in patients with obesity and no prior history of AUD

The study population consisted of 83,825 patients with obesity who had no prior diagnosis of AUD and were for the first time prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications including naltrexone or topiramate in 6/2021–12/2022. The semaglutide cohort ( n = 45,797) compared with the non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications cohort ( n = 38,028) was older, had a higher prevalence of severe obesity and obesity-associated comorbidities including T2DM and lower prevalence of mental disorders, and tobacco use disorder. After propensity-score matching, the two cohorts (26,566 in each cohort, mean age 51.2 years, 65.9% women, 15.8% black, 66.6% white, 6.5% Hispanic) were balanced (Table 1 ). The semaglutide cohort ( n = 45,797) compared with the naltrexone/topiramate cohort ( n = 16,676) was older, had a higher prevalence of severe obesity and obesity-associated comorbidities including T2DM and a lower prevalence of mental disorders, and tobacco use disorder. After propensity-score matching, the two cohorts (15,097 in each cohort, mean age 49.2 years, 71.0% women, 17.2% black, 64.6% white, 6.9% Hispanic) were balanced.

Matched cohorts were followed for 12 months after the index event. Compared to non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications, semaglutide was associated with a significantly lower risk of incident AUD diagnosis (0.37% vs 0.73%; HR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.39–0.63), consistent across gender, age group and race. Significant lower risks were observed in patients with T2DM and without T2DM (Fig. 1a ). Compared to naltrexone or topiramate, semaglutide was associated with a significantly lower risk of incident AUD diagnosis (0.35% vs 0.78%; HR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.32–0.61), consistent across gender, age group and race and in patients with and without T2DM (Fig. 1b ).

a Comparison between propensity-score matched semaglutide and non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications cohorts, stratified by gender, age group, race, and diagnosis of T2DM. b Comparison between propensity-score matched semaglutide and naltrexone/topiramate cohorts, stratified by gender, age group, race, and the diagnosis of T2DM. Patients were followed for 12 months after the index event (first prescription of semaglutide, non-GLP-1 RA anti-obesity medications, or naltrexone/topiramate during 6/2021–12/2022). Hazard rates were calculated using Cox proportional hazards analysis to estimate hazard rates of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied. Overall risk = number of patients with outcomes during the 12-month time window/number of patients in the cohort at the beginning of the time window. AUD Alcohol use disorders, GLP-1RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, T2DM type 2 diabetes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Association of semaglutide with recurrent AUD diagnosis in patients with obesity and a prior history of AUD

The study population consisted of 4254 patients with obesity who had a prior diagnosis of AUD and were for the first time prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications including naltrexone or topiramate in 6/2021–12/2022. The semaglutide cohort ( n = 1470) compared with the non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications cohort ( n = 2784) was older, included more women, had a higher prevalence of severe obesity and obesity-associated comorbidities including T2DM and lower prevalence of adverse socioeconomic determinants of health, mental disorders, and substance use disorders. After propensity-score matching, the two cohorts (1051 in each cohort, mean age 52.6 years, 41.5% women, 16.6% black, 66.2% white, 7.4% Hispanic) were balanced (Table 2 ). The semaglutide cohort ( n = 1470) compared with the naltrexone/topiramate cohort ( n = 1430) was older, included more women, had a higher prevalence of severe obesity and obesity-associated comorbidities including T2DM and lower prevalence of adverse socioeconomic determinants of health, problems with lifestyle, and substance use disorders. After propensity-score matching, the two cohorts (715 in each cohort, mean age 51.5 years, 40.7% women, 15.8% black, 67.7% white, 6.7% Hispanic) were balanced.

Matched cohorts were followed for 12 months after the index event. Compared to non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications, semaglutide was associated with a significantly lower risk of recurrent AUD diagnosis (22.6% vs 43.0%; HR: 0.44, 95% CI: 0.38–0.52), which was consistent across gender, age group and race. Significant lower risks were observed in patients with T2DM and without T2DM (Fig. 2a ). Compared to naltrexone or topiramate, semaglutide was associated with a significantly lower risk of incident AUD diagnosis (21.5% vs 59.9%; HR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.21–0.30), which was consistent across gender, age group and race and in patients with and without T2DM (Fig. 2b ).

a Comparison between propensity-score matched semaglutide and non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications cohorts, stratified by gender, age group, race, and the status of T2DM. b Comparison between propensity-score matched semaglutide and naltrexone/topiramate cohorts, stratified by gender, age group, race, and diagnosis of T2DM. Patients were followed for 12 months after the index event (first prescription of semaglutide, non-GLP-1 RA anti-obesity medications, or naltrexone/topiramate during 6/2021–12/2022). Hazard rates were calculated using Cox proportional hazards analysis to estimate hazard rates of outcome at daily time intervals with censoring applied. Overall risk = number of patients with outcomes during the 12-month time window/number of patients in the cohort at the beginning of the time window. AUD Alcohol use disorders, GLP-1RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, T2DM type 2 diabetes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Association of semaglutide with incident and recurrent AUD diagnosis in patients with T2DM

The study population for the analysis of incident AUD diagnosis in patients with T2DM consisted of 598,803 patients with T2DM who had no prior diagnosis of AUD and were for the first time prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications in 12/2017–5/2021. The semaglutide cohort ( n = 25,686) compared with the non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications cohort ( n = 573,117) was younger, had a higher prevalence of problems related to lifestyle, severe obesity, obesity-associated comorbidities and mental disorders. After propensity-score matching, the two cohorts (26,670 in each cohort, mean age 58.0 years, 45.3% women, 14.7% black, 60.3% white, 6.5% Hispanic) were balanced (Supplementary Table 1 ).

The study population for the analysis of recurrent AUD diagnosis in patients with T2DM consisted of 22,113 patients with T2DM who had a prior diagnosis of AUD and were for the first time prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications in 12/2017–5/2021. The semaglutide cohort ( n = 668) compared with the non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications cohort ( n = 21,445) had a higher prevalence of adverse socioeconomic determinants of health, problems related to lifestyle, severe obesity, obesity-associated comorbidities and mental disorders. After propensity-score matching, the two cohorts (653 in each cohort, mean age 57.4 years, 25.9% women, 17.2% black, 55.5% white, 8.5% Hispanic) were balanced (Supplementary Table 2 ).

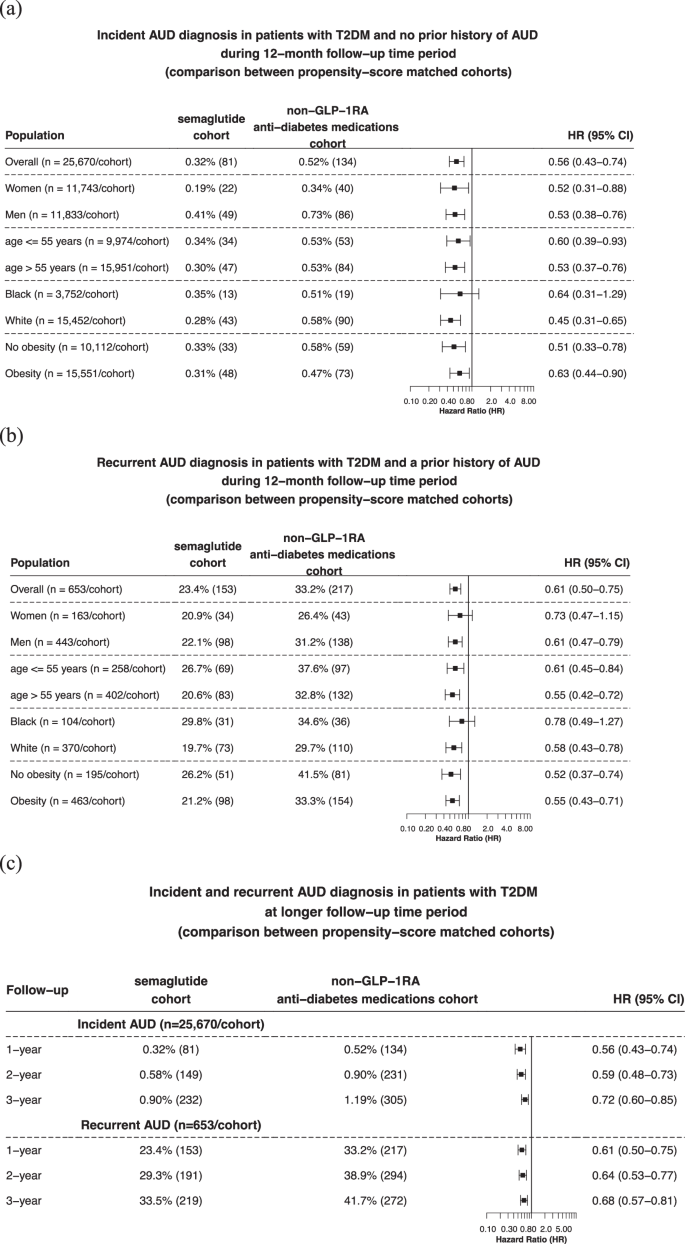

Matched cohorts were followed for 12 months after the index event. Compared to non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications, semaglutide was associated with a significantly lower risk of incident AUD diagnosis (0.32% vs 0.52%; HR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.43–0.74), consistent across gender, age group and race. Significant lower risks were observed in patients with and without a diagnosis of obesity (Fig. 3a ). Semaglutide compared with non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications was associated with a significantly lower risk of recurrent AUD diagnosis (23.4% vs 33.2%; HR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.50–0.75), consistent across gender, age group, and race. Significant lower risks were observed in patients with and without a diagnosis of obesity (Fig. 3b ). The significantly lower risk associations of semaglutide with both incident and recurrent AUD persisted, though slightly attenuated with overlapping confidence intervals, for the 2-year and 3-year follow-up (Fig. 3C ).

a Comparison of 12-month risk for incident AUD diagnosis between propensity-score matched semaglutide and non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications cohorts, stratified by gender, age group, race, and the diagnosis of obesity. b Comparison of 12-month risk of recurrent AUD diagnosis between propensity-score matched semaglutide and non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications cohorts, stratified by gender, age group, race, and the diagnosis of obesity. c Comparison of longer-term risks of incident and recurrent AUD diagnosis between propensity-score matched semaglutide and non-GLP-1RA anti-diabetes medications cohorts. Patients were followed for 12 months, 2-year and 3-year after the index event (first prescription of semaglutide, non-GLP-1 RA anti-diabetes medications in 12/2017–5/2021). AUD Alcohol use disorders, GLP-1RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, T2DM type 2 diabetes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Here we document a potential beneficial effect of semaglutide on both the incidence and recurrence of AUD in real-world populations. The findings were replicated in two separate populations with different characteristics, no-overlapping periods, and non-overlapping patients prescribed semaglutide: one with obesity and the other with T2DM. These beneficial effects are consistent with anecdotal reports that patients prescribed semaglutide describe reduced desire to drink alcohol while on the medication 9 and with recent clinical reports; one documenting reduced alcohol drinking with semaglutide or tirzepatide based on analyses of social media texts and follow up of selected participants 10 , and another of decreased symptoms of AUD in a case series of patients treated with semaglutide 11 . It is also consistent with a small clinical trial study of the GLP-1RA drug exenatide, which significantly reduced heavy drinking days and total alcohol intake in patients with obesity 12 and with a register-based study in Demark showing that GLP-1RAs (though semaglutide was not included) compared with dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP4) were associated with lower incidence of alcohol-related events in 2009–2017 13 . It is also consistent with preclinical studies that documented reduced drinking in rodents exposed to semaglutide 8 and that prevented relapse in a rat model of alcohol dependence 7 .

The underlying mechanisms have not been fully delineated but are likely to involve modulation of the brain dopamine reward system via GLP-1 receptors, which are present both in the ventral tegmental areas (VTA), where dopamine neurons are located, and in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), which is the main projection of VTA dopamine neurons 14 . The involvement of the dopamine reward pathway in modulating food and alcohol consumption 15 could explain why semaglutide is beneficial in reducing food consumption 16 and in animal models reducing alcohol and other drug consumption 5 . Indeed, semaglutide binds to the NAc 7 where it has been shown to attenuate alcohol-induced dopamine increases in alcohol drinking rats 7 providing evidence of semaglutide’s modulation of the mesolimbic dopamine reward system 17 . Importantly the rewarding effects of food are a main contributor to overeating and obesity 18 just as the rewarding effects of alcohol drive alcohol consumption 19 .

Because GLP-1 also mediates stress responses 20 , this could be another mechanism by which semaglutide could buffer stress-related overeating and alcohol consumption 21 . The habenula, which has a high concentration of GLP1 receptors 22 could also participate in semaglutide’s actions as it is involved in the negative reinforcement in obesity 23 and in alcohol and other substance use disorders 24 . Additionally, the anti-inflammatory effects of semaglutide and other GLP1-RA medication have also been implicated in its potential beneficial effects for AUD and other substance use disorder 6 . However, the beneficial effects of semaglutide for alcohol consumption could also reflect the fact that alcohol like food serves as a source of energy 25 , and could include a combination of central 7 and peripheral mechanisms such as the effects of semaglutide on alcohol absorption, pharmacokinetics and metabolism 10 . Though there are no reports on semaglutide’s effects on alcohol absorption and pharmacokinetics it is likely that since it decreases gastric emptying it would also likely decrease alcohol’s absorption. Because the rate of alcohol absorption influences its rewarding effects 26 , delayed absorption could make alcohol less rewarding. Delayed absorption could also increase alcohol’s metabolism in the stomach into acetaldehyde 27 , which would enhance its aversive effects.

As of now, only one randomized clinical trial has been published that evaluated the effects of a GLP-1RA exenatide in patients with AUD 12 . Though this trial did not report reductions in heavy alcohol drinking days (main outcome), it showed a significant attenuation of brain activation to alcohol cues. Also, in a secondary analysis the investigators found a significant reduction in heavy drinking days and total alcohol intake in AUD patients with obesity. This is relevant to our findings since the benefits of semaglutide were observed in patients with obesity and in patients with T2DM many of whom also had obesity. In the analysis of patients with T2DM stratified by their having or not having a diagnosis of obesity, we observed that the lower risk of incident AUD with semaglutide in patients without obesity was similar in patients with obesity. In summary, our study provides real-world evidence supporting the therapeutic benefits of semaglutide for AUD. It is important to clarify that our findings of lower risk of AUD incidence and relapse in patients taking semaglutide cannot be interpreted to indicate that semaglutide reduced AUD symptomatology and are insufficient to justify clinicians’ use of semaglutide off-label to treat AUD. For this to happen data from randomized clinical trials are necessary. Currently, there are five registered clinical trials to evaluate the effect of semaglutide in AUD, and some are already recruiting 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 . Since individuals with AUD are at higher risk for mood disorders and suicidality 33 , 34 and there have been concerns that semaglutide could increase these 35 , though recent evidence suggests it decreases them 36 , it will be important for future clinical trials to assess semaglutide’s effects in mood and suicidal ideation. Future studies should also evaluate interactions with alcohol and with medications for AUD.

Our study has several limitations: First, this is a retrospective observational study, so no causal inferences can be drawn. Second, our study populations represented those who had medical encounters with healthcare systems contributing to the TriNetX Platform. Finding from this study need to be validated in other populations. Third, there are limitations inherent in retrospective observational studies including unmeasured or uncontrolled confounders, self-selection, reverse causality, and other biases. Although the findings were replicated in two separate study populations with different characteristics at two non-overlapping study periods and with non-overlapping exposure cohorts, potential biases or confounders could not be fully eliminated in this observational study. Fourth the follow-up time for the main analyses was 8 months. For the study population with T2DM we conducted a longer follow-up - up to 3 years and observed consistently lower risks in both incident and recurrent AUD associated with semaglutide. However, future studies are necessary to evaluate longer-term associations of semaglutide with AUD in patients with obesity. Fifth, the weekly higher dose format of 2.4 mg semaglutide (marketed as Wegovy) was approved for weight management, and the lower dose format of 0.5–1 mg semaglutide (marketed as Ozempic) was approved for treating T2DM). Interestingly we observed a stronger association of semaglutide with recurrent AUD in patients with obesity than in patients with T2DM (HR of 0.53 vs. 0.74), which could suggest a potential dosage effect. However, the characteristics of these 2 study populations, the comparators, and the study periods were different. Since different dose forms of semaglutide were approved for different disease indications, we could not directly examine the dosage effect of semaglutide in our study.

In summary, our results find an association between reduced risk for incident and AUD relapse with the prescription of smaglutide in patients with obesity or T2DM. While these findings provide preliminary evidence of the potential benefit of semaglutide in AUD in real-world populations further randomized clinical trials are needed to support its use clinically for AUD.

We used built-in statistical and informatics functions within the TriNetX Analytics Platform 37 (Research US Collaborative Network) to analyze aggregated and de-identified patient electronic health records (EHRs). Analyses were performed on January 26, 2024. At the time of this study, TriNetX Research US Collaborative Network contained EHRs of 105.3 million patients from 61 healthcare organizations, most of which are large academic medical institutions, in the US across 50 states: 25%, 17%, 41%, and 12% in the Northeast, Midwest, South, West, respectively, and 5% unknown region. We previously used the TriNetX platform to perform retrospective cohort studies 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 in various populations including patients with substance use disorders 38 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 51 . We also used the TriNetX platform to examine the associations of GLP-1RAs with colorectal cancer 50 and semaglutide with suicidal ideations 36 and cannabis use disorder 51 .

TriNetX de-identifies and aggregates EHRs from contributing healthcare systems completes an intensive data preprocessing stage to minimize missing values, maps the data to a common clinical data model, and provides web-based analytics tools to analyze patient EHRs. All variables are either binary, categorical, or continuous but essentially guaranteed to exist. Missing sex, race, and ethnicity values are represented using “Unknown Sex”, “Unknown race” and “Unknown Ethnicity”, respectively. For other variables (e.g., medical conditions, medications, procedures, lab tests, and socio-economic determinant health), the value is either present or absent, and “missing” is not pertinent.

Ethics statement

The TriNetX platform aggregates and HIPAA de-identifies data contributed from the electronic health records of participating healthcare organizations. The TriNetX platform also only reports population-level results (no access to individual patient data) and uses statistical “blurring”, reporting all population-level counts between 1 and 10 as 10. Based on the de-identification methods used by TriNetX, as per HIPAA privacy and security rules 52 , TriNetX sought and obtained expert attestation that TriNetX data is HIPAA de-identified. Because the data in the TriNetX platform is HIPAA de-identified, and therefore, “by definition” is deemed to allow no access to protected health information (and therefore no risk of protected health information disclosure), Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) have no jurisdiction of studies using HIPAA de-identified data 53 . Since the study concerns non-human subject research, consent from participants was waived and IRB approval was not required for this study.

Study populations

The study population with obesity.

The analyses for the association of semaglutide with both incident and recurrent diagnosis of AUD in patients with obesity were restricted to a starting date of 6/2021 when semaglutide was approved in the US for weight management as Wegovy and an ending date of 12/2022, which allowed for a 12-month follow-up period by the time of data collection and analysis on January 26, 2024.

To assess the associations of semaglutide with incident AUD (first time diagnosis of AUD), the study population included 83,825 patients who had active medical encounters for the diagnosis of obesity in 6/2021–12/2022, were for the first time (new-user design) prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications (naltrexone, topiramate, bupropion, orlistat, phentermine) 54 during 6/2021–12/2022 (time zero or index event), had no diagnosis of AUD on or before the index event and had a diagnosis of at least one of obesity-associated comorbidities (T2D, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hyperlipidemia, heart diseases, stroke) on or before the index event. Patients who were prescribed other GLP-1RAs or had bariatric surgery on or before the index event were excluded. This study population was then divided into 3 cohorts: (1) semaglutide cohort – 45,797 patients who were first-time prescribed semaglutide, (2) non-GLP1-RA anti-obesity medication cohort – 38,028 patients who were first-time prescribed non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications but not semaglutide and (3) naltrexone/topiramate cohort – 16,676 patients who were first time prescribed naltrexone and topiramate but not semaglutide. Among the non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications, naltrexone and topiramate were also prescribed for AUD 3 . We constructed the naltrexone/topiramate cohort to compare semaglutide to naltrexone/topiramate for incident AUD risk in patients with obesity. We used new-user design to mitigate prevalent user bias and confounding associated with the drug itself 55 , 56 .

To assess the associations of semaglutide with recurrent AUD diagnosis (recurrent medical encounters for AUD diagnosis), the study population included 4254 patients who had active medical encounters for the diagnosis of obesity in 6/2021–12/2022, were for the first time (new-user design) prescribed semaglutide or non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications during 6/2021–12/2022 (index event), had a diagnosis of AUD on or before the index event and had a diagnosis of at least one of obesity-associated comorbidities on or before the index event. Patients who were prescribed other GLP-1RAs or had bariatric surgery on or before the index event were excluded. This study population was then divided into 3 cohorts: (1) semaglutide cohort – 1470 patients who were first-time prescribed semaglutide, (2) non-GLP1-RA anti-obesity medication cohort – 2784 patients who were first-time prescribed non-GLP-1RA anti-obesity medications but not semaglutide and (3) naltrexone/topiramate cohort – 1430 patients who were first time prescribed naltrexone and topiramate but not semaglutide. We constructed the naltrexone/topiramate cohort to compare semaglutide to naltrexone/topiramate for recurrent AUD risk in patients with obesity.

The study populations with T2DM

The analyses on the associations of semaglutide with both incident and recurrent AUD among patients with T2DM had a starting time of 12/2017 when semaglutide was approved in the US to treat T2DM as Ozempic and an ending date of 5/2021 to allow us to separately examine the associations of semaglutide on AUD as Ozempic from those as Wegovy in the study population with obesity. Since patients in the study population with obesity were for the first time prescribed semaglutide after 6/2021, there was no overlap in the exposure cohorts for these two study populations.