- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms , including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies , or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly

It's always a good practice to give credit where it's due, and the same goes for citing any works that have influenced your paper. Building your arguments on credible references adds value and authenticity to your research. In the formatting guidelines section, you’ll find an overview of different citation styles (MLA, CMOS, or APA), which will help you meet any publishing or academic requirements and strengthen your paper's credibility. It is essential to follow the guidelines provided by your school or the publication you are submitting to ensure the accuracy and relevance of your citations.

11. Ensure your work is original

It is crucial to ensure the originality of your paper, as plagiarism can lead to serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, you should use proper paraphrasing and quoting techniques. Paraphrasing is rewriting a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. Quoting involves directly citing the source. Giving credit to the original author or source is essential whenever you borrow their ideas or words. You can also use plagiarism detection tools such as Scribbr or Grammarly to check the originality of your paper. These tools compare your draft writing to a vast database of online sources. If you find any accidental plagiarism, you should correct it immediately by rephrasing or citing the source.

12. Revise, edit, and proofread

One of the essential qualities of excellent writers is their ability to understand the importance of editing and proofreading. Even though it's tempting to call it a day once you've finished your writing, editing your work can significantly improve its quality. It's natural to overlook the weaker areas when you've just finished writing a paper. Therefore, it's best to take a break of a day or two, or even up to a week, to refresh your mind. This way, you can return to your work with a new perspective. After some breathing room, you can spot any inconsistencies, spelling and grammar errors, typos, or missing citations and correct them.

- The best research paper format

The format of your research paper should align with the requirements set forth by your college, school, or target publication.

There is no one “best” format, per se. Depending on the stated requirements, you may need to include the following elements:

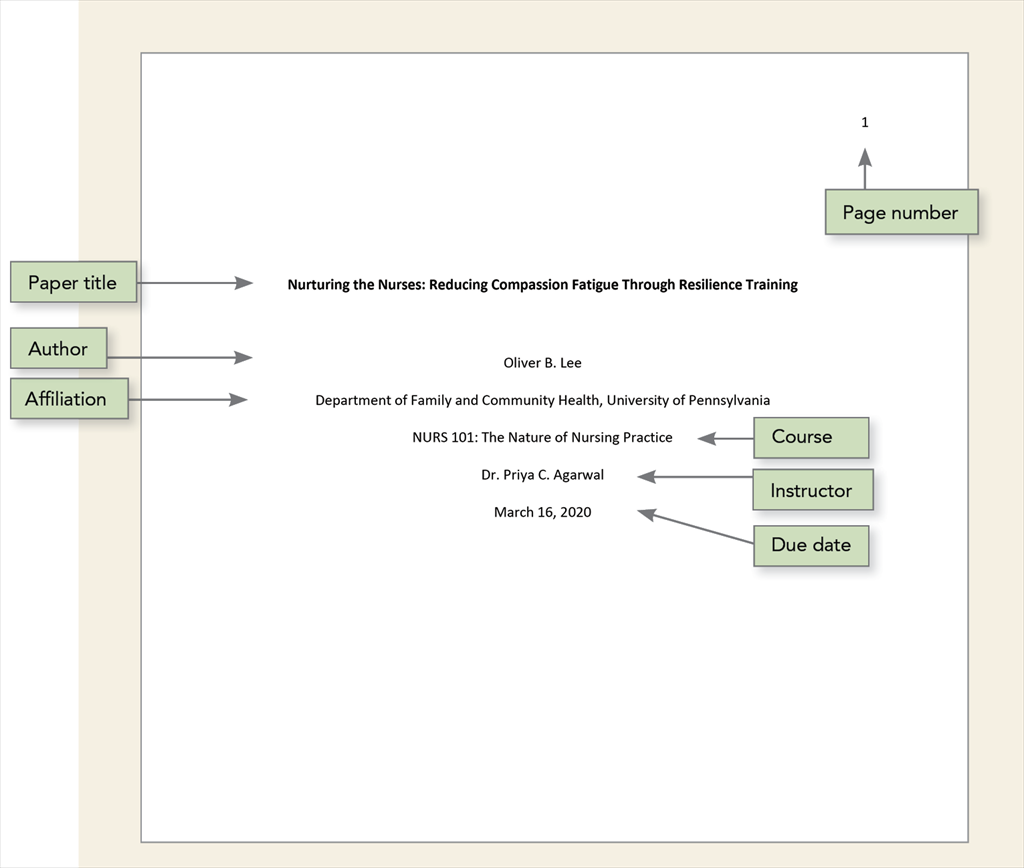

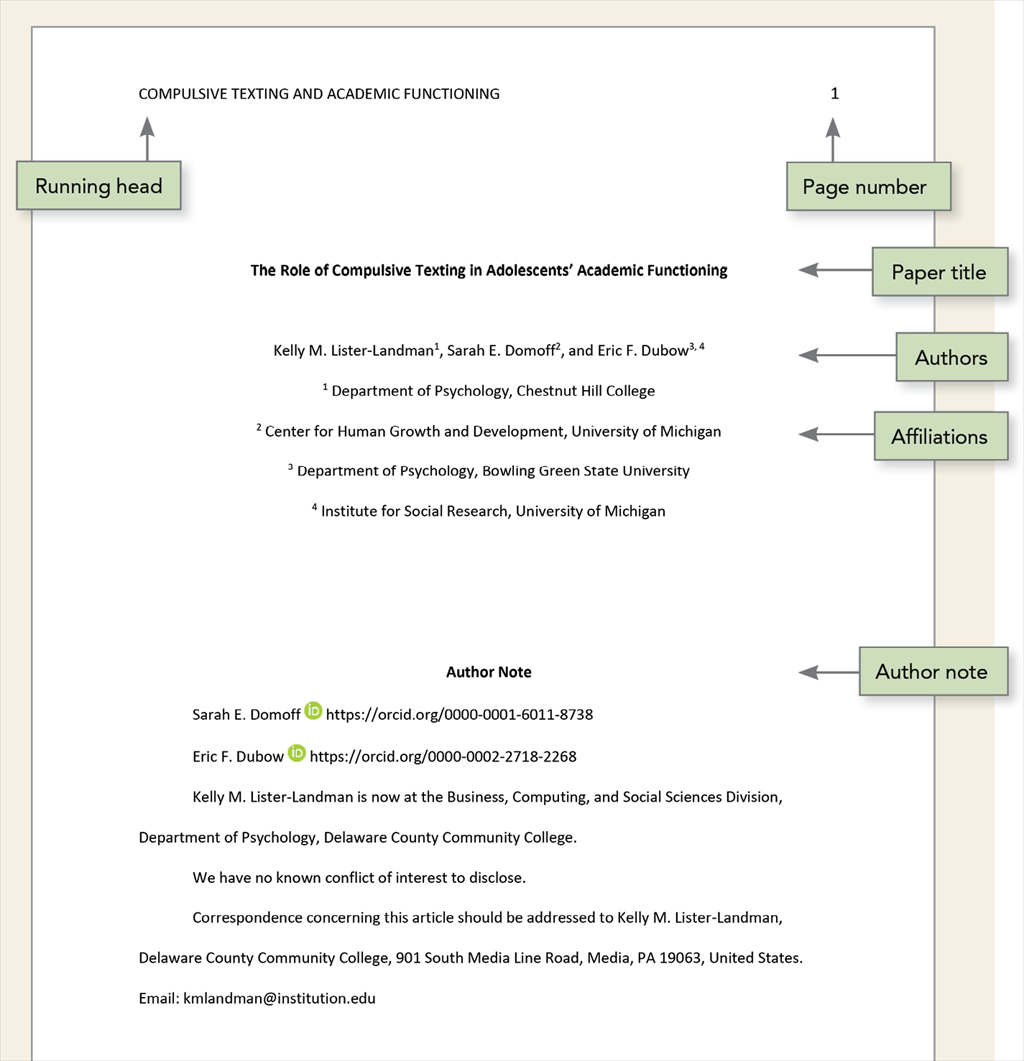

Title page: The title page of a research paper typically includes the title, author's name, and institutional affiliation and may include additional information such as a course name or instructor's name.

Table of contents: Include a table of contents to make it easy for readers to find specific sections of your paper.

Abstract: The abstract is a summary of the purpose of the paper.

Methods : In this section, describe the research methods used. This may include collecting data , conducting interviews, or doing field research .

Results: Summarize the conclusions you drew from your research in this section.

Discussion: In this section, discuss the implications of your research . Be sure to mention any significant limitations to your approach and suggest areas for further research.

Tables, charts, and illustrations: Use tables, charts, and illustrations to help convey your research findings and make them easier to understand.

Works cited or reference page: Include a works cited or reference page to give credit to the sources that you used to conduct your research.

Bibliography: Provide a list of all the sources you consulted while conducting your research.

Dedication and acknowledgments : Optionally, you may include a dedication and acknowledgments section to thank individuals who helped you with your research.

- General style and formatting guidelines

Formatting your research paper means you can submit it to your college, journal, or other publications in compliance with their criteria.

Research papers tend to follow the American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) guidelines.

Here’s how each style guide is typically used:

Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS):

CMOS is a versatile style guide used for various types of writing. It's known for its flexibility and use in the humanities. CMOS provides guidelines for citations, formatting, and overall writing style. It allows for both footnotes and in-text citations, giving writers options based on their preferences or publication requirements.

American Psychological Association (APA):

APA is common in the social sciences. It’s hailed for its clarity and emphasis on precision. It has specific rules for citing sources, creating references, and formatting papers. APA style uses in-text citations with an accompanying reference list. It's designed to convey information efficiently and is widely used in academic and scientific writing.

Modern Language Association (MLA):

MLA is widely used in the humanities, especially literature and language studies. It emphasizes the author-page format for in-text citations and provides guidelines for creating a "Works Cited" page. MLA is known for its focus on the author's name and the literary works cited. It’s frequently used in disciplines that prioritize literary analysis and critical thinking.

To confirm you're using the latest style guide, check the official website or publisher's site for updates, consult academic resources, and verify the guide's publication date. Online platforms and educational resources may also provide summaries and alerts about any revisions or additions to the style guide.

Citing sources

When working on your research paper, it's important to cite the sources you used properly. Your citation style will guide you through this process. Generally, there are three parts to citing sources in your research paper:

First, provide a brief citation in the body of your essay. This is also known as a parenthetical or in-text citation.

Second, include a full citation in the Reference list at the end of your paper. Different types of citations include in-text citations, footnotes, and reference lists.

In-text citations include the author's surname and the date of the citation.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page of your research paper. They may also be summarized within a reference list at the end of the paper.

A reference list includes all of the research used within the paper at the end of the document. It should include the author, date, paper title, and publisher listed in the order that aligns with your citation style.

10 research paper writing tips:

Following some best practices is essential to writing a research paper that contributes to your field of study and creates a positive impact.

These tactics will help you structure your argument effectively and ensure your work benefits others:

Clear and precise language: Ensure your language is unambiguous. Use academic language appropriately, but keep it simple. Also, provide clear takeaways for your audience.

Effective idea separation: Organize the vast amount of information and sources in your paper with paragraphs and titles. Create easily digestible sections for your readers to navigate through.

Compelling intro: Craft an engaging introduction that captures your reader's interest. Hook your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

Thorough revision and editing: Take the time to review and edit your paper comprehensively. Use tools like Grammarly to detect and correct small, overlooked errors.

Thesis precision: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your paper. Ensure that your thesis aligns with your research's overall purpose and contribution.

Logical flow of ideas: Maintain a logical progression throughout the paper. Use transitions effectively to connect different sections and maintain coherence.

Critical evaluation of sources: Evaluate and critically assess the relevance and reliability of your sources. Ensure that your research is based on credible and up-to-date information.

Thematic consistency: Maintain a consistent theme throughout the paper. Ensure that all sections contribute cohesively to the overall argument.

Relevant supporting evidence: Provide concise and relevant evidence to support your arguments. Avoid unnecessary details that may distract from the main points.

Embrace counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing views to strengthen your position. Show that you have considered alternative arguments in your field.

7 research tips

If you want your paper to not only be well-written but also contribute to the progress of human knowledge, consider these tips to take your paper to the next level:

Selecting the appropriate topic: The topic you select should align with your area of expertise, comply with the requirements of your project, and have sufficient resources for a comprehensive investigation.

Use academic databases: Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR offer a wealth of research papers that can help you discover everything you need to know about your chosen topic.

Critically evaluate sources: It is important not to accept research findings at face value. Instead, it is crucial to critically analyze the information to avoid jumping to conclusions or overlooking important details. A well-written research paper requires a critical analysis with thorough reasoning to support claims.

Diversify your sources: Expand your research horizons by exploring a variety of sources beyond the standard databases. Utilize books, conference proceedings, and interviews to gather diverse perspectives and enrich your understanding of the topic.

Take detailed notes: Detailed note-taking is crucial during research and can help you form the outline and body of your paper.

Stay up on trends: Keep abreast of the latest developments in your field by regularly checking for recent publications. Subscribe to newsletters, follow relevant journals, and attend conferences to stay informed about emerging trends and advancements.

Engage in peer review: Seek feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the rigor and validity of your research . Peer review helps identify potential weaknesses in your methodology and strengthens the overall credibility of your findings.

- The real-world impact of research papers

Writing a research paper is more than an academic or business exercise. The experience provides an opportunity to explore a subject in-depth, broaden one's understanding, and arrive at meaningful conclusions. With careful planning, dedication, and hard work, writing a research paper can be a fulfilling and enriching experience contributing to advancing knowledge.

How do I publish my research paper?

Many academics wish to publish their research papers. While challenging, your paper might get traction if it covers new and well-written information. To publish your research paper, find a target publication, thoroughly read their guidelines, format your paper accordingly, and send it to them per their instructions. You may need to include a cover letter, too. After submission, your paper may be peer-reviewed by experts to assess its legitimacy, quality, originality, and methodology. Following review, you will be informed by the publication whether they have accepted or rejected your paper.

What is a good opening sentence for a research paper?

Beginning your research paper with a compelling introduction can ensure readers are interested in going further. A relevant quote, a compelling statistic, or a bold argument can start the paper and hook your reader. Remember, though, that the most important aspect of a research paper is the quality of the information––not necessarily your ability to storytell, so ensure anything you write aligns with your goals.

Research paper vs. a research proposal—what’s the difference?

While some may confuse research papers and proposals, they are different documents.

A research proposal comes before a research paper. It is a detailed document that outlines an intended area of exploration. It includes the research topic, methodology, timeline, sources, and potential conclusions. Research proposals are often required when seeking approval to conduct research.

A research paper is a summary of research findings. A research paper follows a structured format to present those findings and construct an argument or conclusion.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

- 10 research paper

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Primacy of the research question, structure of the paper, writing a research article: advice to beginners.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Thomas V. Perneger, Patricia M. Hudelson, Writing a research article: advice to beginners, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 16, Issue 3, June 2004, Pages 191–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Writing research papers does not come naturally to most of us. The typical research paper is a highly codified rhetorical form [ 1 , 2 ]. Knowledge of the rules—some explicit, others implied—goes a long way toward writing a paper that will get accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

A good research paper addresses a specific research question. The research question—or study objective or main research hypothesis—is the central organizing principle of the paper. Whatever relates to the research question belongs in the paper; the rest doesn’t. This is perhaps obvious when the paper reports on a well planned research project. However, in applied domains such as quality improvement, some papers are written based on projects that were undertaken for operational reasons, and not with the primary aim of producing new knowledge. In such cases, authors should define the main research question a posteriori and design the paper around it.

Generally, only one main research question should be addressed in a paper (secondary but related questions are allowed). If a project allows you to explore several distinct research questions, write several papers. For instance, if you measured the impact of obtaining written consent on patient satisfaction at a specialized clinic using a newly developed questionnaire, you may want to write one paper on the questionnaire development and validation, and another on the impact of the intervention. The idea is not to split results into ‘least publishable units’, a practice that is rightly decried, but rather into ‘optimally publishable units’.

What is a good research question? The key attributes are: (i) specificity; (ii) originality or novelty; and (iii) general relevance to a broad scientific community. The research question should be precise and not merely identify a general area of inquiry. It can often (but not always) be expressed in terms of a possible association between X and Y in a population Z, for example ‘we examined whether providing patients about to be discharged from the hospital with written information about their medications would improve their compliance with the treatment 1 month later’. A study does not necessarily have to break completely new ground, but it should extend previous knowledge in a useful way, or alternatively refute existing knowledge. Finally, the question should be of interest to others who work in the same scientific area. The latter requirement is more challenging for those who work in applied science than for basic scientists. While it may safely be assumed that the human genome is the same worldwide, whether the results of a local quality improvement project have wider relevance requires careful consideration and argument.

Once the research question is clearly defined, writing the paper becomes considerably easier. The paper will ask the question, then answer it. The key to successful scientific writing is getting the structure of the paper right. The basic structure of a typical research paper is the sequence of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion (sometimes abbreviated as IMRAD). Each section addresses a different objective. The authors state: (i) the problem they intend to address—in other terms, the research question—in the Introduction; (ii) what they did to answer the question in the Methods section; (iii) what they observed in the Results section; and (iv) what they think the results mean in the Discussion.

In turn, each basic section addresses several topics, and may be divided into subsections (Table 1 ). In the Introduction, the authors should explain the rationale and background to the study. What is the research question, and why is it important to ask it? While it is neither necessary nor desirable to provide a full-blown review of the literature as a prelude to the study, it is helpful to situate the study within some larger field of enquiry. The research question should always be spelled out, and not merely left for the reader to guess.

Typical structure of a research paper

| Introduction |

| State why the problem you address is important |

| State what is lacking in the current knowledge |

| State the objectives of your study or the research question |

| Methods |

| Describe the context and setting of the study |

| Specify the study design |

| Describe the ‘population’ (patients, doctors, hospitals, etc.) |

| Describe the sampling strategy |

| Describe the intervention (if applicable) |

| Identify the main study variables |

| Describe data collection instruments and procedures |

| Outline analysis methods |

| Results |

| Report on data collection and recruitment (response rates, etc.) |

| Describe participants (demographic, clinical condition, etc.) |

| Present key findings with respect to the central research question |

| Present secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.) |

| Discussion |

| State the main findings of the study |

| Discuss the main results with reference to previous research |

| Discuss policy and practice implications of the results |

| Analyse the strengths and limitations of the study |

| Offer perspectives for future work |

| Introduction |

| State why the problem you address is important |

| State what is lacking in the current knowledge |

| State the objectives of your study or the research question |

| Methods |

| Describe the context and setting of the study |

| Specify the study design |

| Describe the ‘population’ (patients, doctors, hospitals, etc.) |

| Describe the sampling strategy |

| Describe the intervention (if applicable) |

| Identify the main study variables |

| Describe data collection instruments and procedures |

| Outline analysis methods |

| Results |

| Report on data collection and recruitment (response rates, etc.) |

| Describe participants (demographic, clinical condition, etc.) |

| Present key findings with respect to the central research question |

| Present secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.) |

| Discussion |

| State the main findings of the study |

| Discuss the main results with reference to previous research |

| Discuss policy and practice implications of the results |

| Analyse the strengths and limitations of the study |

| Offer perspectives for future work |

The Methods section should provide the readers with sufficient detail about the study methods to be able to reproduce the study if so desired. Thus, this section should be specific, concrete, technical, and fairly detailed. The study setting, the sampling strategy used, instruments, data collection methods, and analysis strategies should be described. In the case of qualitative research studies, it is also useful to tell the reader which research tradition the study utilizes and to link the choice of methodological strategies with the research goals [ 3 ].

The Results section is typically fairly straightforward and factual. All results that relate to the research question should be given in detail, including simple counts and percentages. Resist the temptation to demonstrate analytic ability and the richness of the dataset by providing numerous tables of non-essential results.

The Discussion section allows the most freedom. This is why the Discussion is the most difficult to write, and is often the weakest part of a paper. Structured Discussion sections have been proposed by some journal editors [ 4 ]. While strict adherence to such rules may not be necessary, following a plan such as that proposed in Table 1 may help the novice writer stay on track.

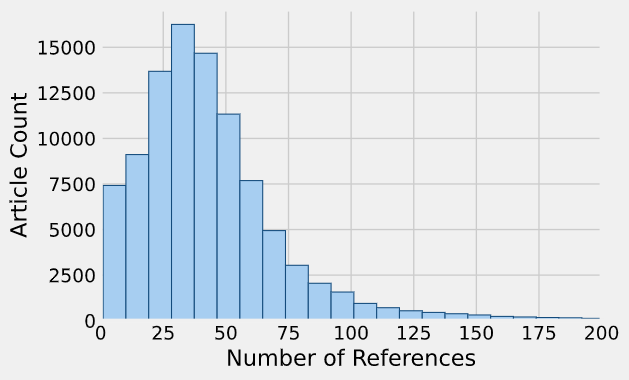

References should be used wisely. Key assertions should be referenced, as well as the methods and instruments used. However, unless the paper is a comprehensive review of a topic, there is no need to be exhaustive. Also, references to unpublished work, to documents in the grey literature (technical reports), or to any source that the reader will have difficulty finding or understanding should be avoided.

Having the structure of the paper in place is a good start. However, there are many details that have to be attended to while writing. An obvious recommendation is to read, and follow, the instructions to authors published by the journal (typically found on the journal’s website). Another concerns non-native writers of English: do have a native speaker edit the manuscript. A paper usually goes through several drafts before it is submitted. When revising a paper, it is useful to keep an eye out for the most common mistakes (Table 2 ). If you avoid all those, your paper should be in good shape.

Common mistakes seen in manuscripts submitted to this journal

| The research question is not specified |

| The stated aim of the paper is tautological (e.g. ‘The aim of this paper is to describe what we did’) or vague (e.g. ‘We explored issues related to X’) |

| The structure of the paper is chaotic (e.g. methods are described in the Results section) |

| The manuscripts does not follow the journal’s instructions for authors |

| The paper much exceeds the maximum number of words allowed |

| The Introduction is an extensive review of the literature |

| Methods, interventions and instruments are not described in sufficient detail |

| Results are reported selectively (e.g. percentages without frequencies, -values without measures of effect) |

| The same results appear both in a table and in the text |

| Detailed tables are provided for results that do not relate to the main research question |

| In the Introduction and Discussion, key arguments are not backed up by appropriate references |

| References are out of date or cannot be accessed by most readers |

| The Discussion does not provide an answer to the research question |

| The Discussion overstates the implications of the results and does not acknowledge the limitations of the study |

| The paper is written in poor English |

| The research question is not specified |

| The stated aim of the paper is tautological (e.g. ‘The aim of this paper is to describe what we did’) or vague (e.g. ‘We explored issues related to X’) |

| The structure of the paper is chaotic (e.g. methods are described in the Results section) |

| The manuscripts does not follow the journal’s instructions for authors |

| The paper much exceeds the maximum number of words allowed |

| The Introduction is an extensive review of the literature |

| Methods, interventions and instruments are not described in sufficient detail |

| Results are reported selectively (e.g. percentages without frequencies, -values without measures of effect) |

| The same results appear both in a table and in the text |

| Detailed tables are provided for results that do not relate to the main research question |

| In the Introduction and Discussion, key arguments are not backed up by appropriate references |

| References are out of date or cannot be accessed by most readers |

| The Discussion does not provide an answer to the research question |

| The Discussion overstates the implications of the results and does not acknowledge the limitations of the study |

| The paper is written in poor English |

Huth EJ . How to Write and Publish Papers in the Medical Sciences , 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1990 .

Browner WS . Publishing and Presenting Clinical Research . Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999 .

Devers KJ , Frankel RM. Getting qualitative research published. Educ Health 2001 ; 14 : 109 –117.

Docherty M , Smith R. The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers. Br Med J 1999 ; 318 : 1224 –1225.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2016 | 1 |

| January 2017 | 242 |

| February 2017 | 451 |

| March 2017 | 632 |

| April 2017 | 289 |

| May 2017 | 349 |

| June 2017 | 347 |

| July 2017 | 752 |

| August 2017 | 649 |

| September 2017 | 844 |

| October 2017 | 920 |

| November 2017 | 1,646 |

| December 2017 | 7,530 |

| January 2018 | 8,339 |

| February 2018 | 9,141 |

| March 2018 | 13,810 |

| April 2018 | 19,070 |

| May 2018 | 16,599 |

| June 2018 | 13,752 |

| July 2018 | 12,558 |

| August 2018 | 15,395 |

| September 2018 | 14,283 |

| October 2018 | 14,089 |

| November 2018 | 17,418 |

| December 2018 | 16,718 |

| January 2019 | 17,941 |

| February 2019 | 15,452 |

| March 2019 | 17,862 |

| April 2019 | 18,214 |

| May 2019 | 17,643 |

| June 2019 | 13,983 |

| July 2019 | 13,079 |

| August 2019 | 12,840 |

| September 2019 | 12,724 |

| October 2019 | 10,555 |

| November 2019 | 9,256 |

| December 2019 | 7,084 |

| January 2020 | 7,476 |

| February 2020 | 8,890 |

| March 2020 | 8,359 |

| April 2020 | 13,466 |

| May 2020 | 6,115 |

| June 2020 | 8,233 |

| July 2020 | 7,063 |

| August 2020 | 6,487 |

| September 2020 | 8,284 |

| October 2020 | 9,266 |

| November 2020 | 10,248 |

| December 2020 | 10,201 |

| January 2021 | 9,786 |

| February 2021 | 10,582 |

| March 2021 | 10,011 |

| April 2021 | 10,238 |

| May 2021 | 9,880 |

| June 2021 | 8,729 |

| July 2021 | 6,278 |

| August 2021 | 6,723 |

| September 2021 | 7,704 |

| October 2021 | 8,604 |

| November 2021 | 9,733 |

| December 2021 | 7,678 |

| January 2022 | 7,286 |

| February 2022 | 7,406 |

| March 2022 | 8,097 |

| April 2022 | 7,589 |

| May 2022 | 8,337 |

| June 2022 | 5,305 |

| July 2022 | 3,959 |

| August 2022 | 4,166 |

| September 2022 | 5,435 |

| October 2022 | 5,294 |

| November 2022 | 5,096 |

| December 2022 | 4,104 |

| January 2023 | 3,550 |

| February 2023 | 4,079 |

| March 2023 | 4,935 |

| April 2023 | 3,793 |

| May 2023 | 3,689 |

| June 2023 | 2,548 |

| July 2023 | 2,313 |

| August 2023 | 2,125 |

| September 2023 | 2,172 |

| October 2023 | 2,859 |

| November 2023 | 2,767 |

| December 2023 | 2,335 |

| January 2024 | 2,825 |

| February 2024 | 2,630 |

| March 2024 | 2,874 |

| April 2024 | 2,311 |

| May 2024 | 2,108 |

| June 2024 | 1,586 |

| July 2024 | 8,045 |

| August 2024 | 1,924 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

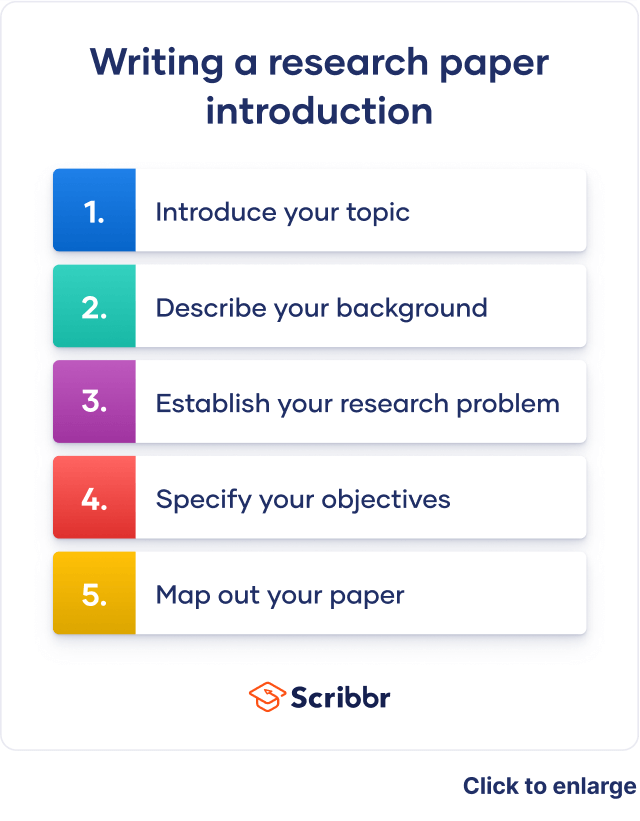

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Outline – Types, Example, Template

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Implications in Research – Types, Examples and...

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Research Paper Title Page – Example and Making...

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

280k Accesses

15 Citations

710 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

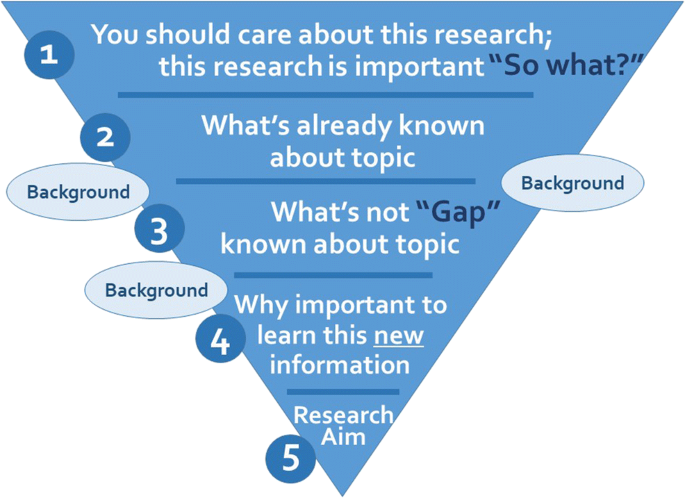

Structure of the Introduction Section

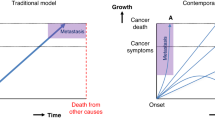

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

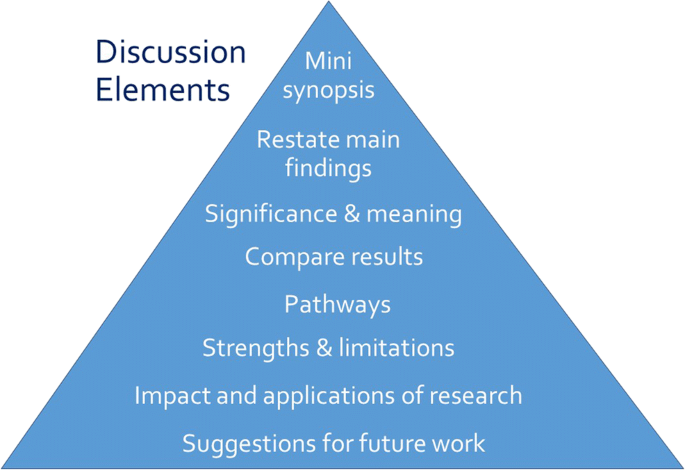

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

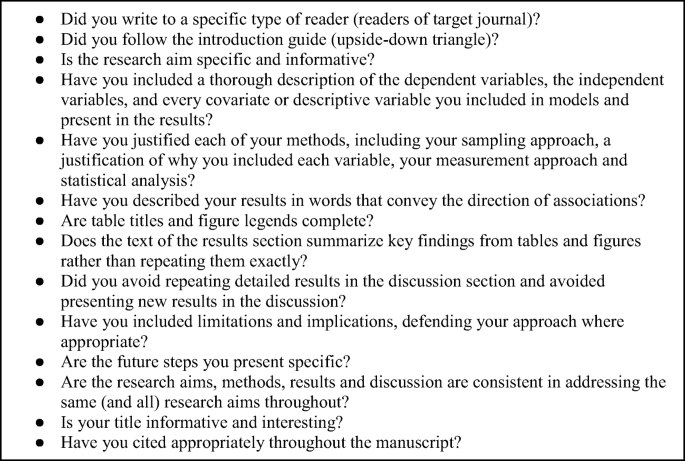

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions