Last updated 20/06/24: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > European Psychiatry

- > Volume 26 Issue S2: Abstracts of the 19th European...

- > Olfactory reference syndrome - A case report

Article contents

Olfactory reference syndrome - a case report.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 April 2020

Olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), first described by Pryse-Phillips in 1971, is a rare psychiatric condition whose defining characteristic is a preoccupation with the belief that one emits a foul or offensive body odor, which is not perceived by others. Although the existence of ORS is now widely accepted, current classifications do not explicitly mention ORS as an independent category, but consider it as a delusional disorder, somatic type. Nonetheless, given this syndrome's consistent description along time and cultures, and the associated substancial distress and disability, many authors debate the possibility of a new classification in order to establish its nosological status.

The aim of this paper is to show and discuss some troublesome and complex issues of diagnosis and management of patients with ORS.

Herein we report a case of a 38-year-old woman who presented with ORS.

Improvement in ORS can take place, in some extent, with a variety of different modalities of treatment, with the disorder responding to antidepressants and psychotherapy more frequently than to neuroleptics. Data on ORS are still limited and more research in this field is needed. Awareness of this particular diagnosis allows appropriate treatment to be administered.

No CrossRef data available.

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 26, Issue S2

- D. Freitas (a1) , P. Ferreira (a1) and N. Fernandes (a1)

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(11)73423-X

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Olfactory reference syndrome: a still open nosological and treatment debate

Affiliations.

- 1 Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo State University-Univ Estadual Paulista (Unesp), Brazil.

- 2 Anxiety and Depression Research Program, Institute of Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro & D'Or Institute for Research and Education, Brazil.

- 3 Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo State University-Univ Estadual Paulista (Unesp), Brazil. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 25041636

- DOI: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.06.001

Objective: The objective was to report a case of olfactory reference syndrome (ORS) with several co-occurring disorders and to discuss ORS differential diagnoses, diagnostic criteria and classification.

Method: Case report.

Results: A 37-year-old married woman presented overvalued ideas of having bad breath since adolescence. She met current diagnostic criteria for social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, body dysmorphic disorder and major depressive disorder. ORS similarities and differences with some related disorders are discussed.

Conclusion: Further studies regarding symptoms, biomarkers and outcomes are needed to fully disentangle ORS from existing depressive, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders.

Keywords: Diagnostic criteria; Differential diagnoses; Nosological classification; Obsessive–compulsive disorder; Olfactory reference syndrome.

Copyright © 2014 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Transdiagnostic Approach to Olfactory Reference Syndrome: Neurobiological Considerations. Skimming KA, Miller CWT. Skimming KA, et al. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2019 May/Jun;27(3):193-200. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000215. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2019. PMID: 31082994 Review.

- Unremitting body odour: A case of Olfactory Reference Syndrome. Tee CK, Suzaily W. Tee CK, et al. Clin Ter. 2015;166(2):72-3. doi: 10.7417/CT.2015.1819. Clin Ter. 2015. PMID: 25945434

- Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders in obsessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety disorders. Lochner C, Stein DJ. Lochner C, et al. Psychopathology. 2010;43(6):389-96. doi: 10.1159/000321070. Epub 2010 Sep 16. Psychopathology. 2010. PMID: 20847586

- Body dysmorphic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: similarities, differences and the classification debate. Chosak A, Marques L, Greenberg JL, Jenike E, Dougherty DD, Wilhelm S. Chosak A, et al. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008 Aug;8(8):1209-18. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.8.1209. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008. PMID: 18671665 Review.

- Olfactory reference syndrome: diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis. Lochner C, Stein DJ. Lochner C, et al. J Postgrad Med. 2003 Oct-Dec;49(4):328-31. J Postgrad Med. 2003. PMID: 14699232

- Psychosomatic problems in dentistry. Toyofuku A. Toyofuku A. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016 Apr 30;10:14. doi: 10.1186/s13030-016-0068-2. eCollection 2016. Biopsychosoc Med. 2016. PMID: 27134647 Free PMC article. Review.

- Olfactory Reference Disorder: Diagnosis, Epidemiology and Management. Thomas E, du Plessis S, Chiliza B, Lochner C, Stein D. Thomas E, et al. CNS Drugs. 2015 Dec;29(12):999-1007. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0292-5. CNS Drugs. 2015. PMID: 26563195 Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Olfactory Reference Syndrome: A Case Report and Screening Tool

- Published: 29 April 2020

- Volume 28 , pages 344–348, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Yelena Chernyak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6925-1981 1 ,

- Kristine M. Chapleau 1 ,

- Shariff F. Tanious 1 ,

- Natalie C. Dattilo 2 ,

- David R. Diaz 1 &

- Sarah A. Landsberger 1

573 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Olfactory reference syndrome (ORS) is a lesser known disorder that is related to obsessive–compulsive disorder. ORS is the obsessional and inaccurate belief that one is emitting a foul odor leading to embarrassment or concern about offending others, excessive hygiene behaviors, and social avoidance that significantly interferes with daily functioning. Although ORS is rare, it is challenging to diagnose. ORS-sufferers first seek treatment from non-psychiatric providers (e.g., dermatologists, dentists.) to alleviate the perceived odor, which frequently leads to misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatments. Additionally, because ORS-sufferers can have limited insight and ideas of reference, they can be misdiagnosed as having a psychotic or delusional disorder. We present a case report of a 42-year-old woman with ORS, and how the correct diagnosis of ORS provided with psychiatric treatment led to significant improvement in her daily functioning. We provide a literature review on the disorder as well as a short screener to assess ORS.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Olfactory reference disorder—a review

Olfactory Reference Disorder: Diagnosis, Epidemiology and Management

Prevalence of olfactory reference disorder according to the icd-11 in a german university student sample.

Allen-Crooks, R., & Challacombe, F. (2017). Cognitive behavior therapy for olfactory reference disorder (ORD): A case study. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 13 , 7–13.

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR . Washington, DC: APA.

Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 . Washington, DC: APA.

Book Google Scholar

Asakura, S., Inoue, T., Kitagawa, N., Nasegama, M., Fujii, Y., Kako, Y., … Nakagawa, S. (2012). Social Anxiety/Taijin-Kyofu Scale (SATS): Development and psychometric evaluation of a new instrument. Psychopathology, 45 , 96–101.

Atmaca, M., Korkmaz, S., Namli, M. N., Kormaz, H., & Kuloglu, M. (2011). Olfactory reference syndrome treated with quetiapine: A case. Bull of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 21 , 246–248.

Begum, M., & McKenna, P. J. (2011). Olfactory reference syndrome: A systematic review of the world literature. Psychological Medicine, 41 , 453–461.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bizamcer, A. N., Dubin, W. R., & Hayburn, B. (2008). Olfactory reference syndrome. Psychosomatics, 49 , 77–81.

Feusner, J. D., Phillips, K. A., & Stein, D. J. (2010). Olfactory reference syndrome: Issues for DSM-V. Depression & Anxiety, 27 , 592–599.

Greenberg, J. L., Shaw, A. M., Reuman, L., Schwarts, R., & Wilhelm, S. (2016). Clinical features of olfactory reference syndrome: An internet-based study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 80 , 11–16.

Kasahara, Y., & Kenji, S. (1971). Ereuthophobia and allied conditions: A contribution toward the psychopathological and cross cultural study of a borderline state. In S. Arieti (Ed.), The world biennial of psychiatry in psychotherapy . New York: Basic Books.

Kozak, M. J., & Foa, E. B. (1994). Obsessions, overvalued ideas, and delusions in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 32 , 343–353.

Lim, L., & Wan, Y. M. (2015). Jikoshu-kyofu in Singapore. Australasian Psychiatry, 23 , 300–302.

Lochner, C., & Stein, D. (2003). Olfactory reference syndrome: Diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 49 , 328–331.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Marks, I., & Mishan, J. (1988). Dysmorphophobic avoidance with disturbed bodily perception: A pilot study of exposure therapy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 152 , 674–678.

Muffatti, R., Scarone, S., & Gambini, O. (2008). An olfactory reference syndrome successfully treated by aripiprazole augmentation to antidepressant therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, 21 , 258–260.

Phillips, K. A., Hollander, E., Rasmussen, S. A., Aronowitz, B. R., DeCaria, C., & Goodman, W. K. (1997). A severity rating scale or body dysmorphic disorder: Development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 33 , 17–22.

Phillips, K. A., & Menard, W. (2011). Olfactory reference syndrome: Demographic and clinical features of imagined body odor. General Hospital Psychiatry, 33 , 398–406.

Prazeres, A. M., Fontenelle, L. F., Medlowicz, M. V., De Mathis, M. A., Ferraro, Y. A., de Brito, N. F., … Miguel, E. C. (2010). Olfactory reference syndrome as a subtype of body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71 , 87–89.

Pryse-Phillips, W. (1971). An olfactory reference syndrome. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 47 , 484–509.

Stein, D. J., Le Roux, L., Bouwer, C., & Van Heerdeen, B. (1998). Is olfactory reference syndrome an obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder?: Two cases and a discussion. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 10 , 96–99.

Stein, D. J., Kogan, C. S., Atmaca, M., Fineberg, N. A., Fontenelle, L. F., Grant, J. E., … Van Den Heuvel, O. A. (2016). The classification of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders in the ICD-11. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190 , 663–674.

Suzuki, K., Takei, N., Iwata, Y., Sekine, Y., Toyoda, T., Nakamura, K., … Mori, N. (2004). Do olfactory reference syndrome and jiko-shu-kyofu (a subtype of taijin-kyofu) share a common entity? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109 , 150–155.

Teraishi, T., Takahashi, T., Suda, T., Hirano, J., Ogawa, T., Kuwahara, T., … Nomura, S. (2012). Successful treatment of olfactory reference syndrome with paroxetine. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 24 , E24.

Download references

This article has no funding source.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, 355 W. 16th St., Suite 2800, Indianapolis, IN, 46202, USA

Yelena Chernyak, Kristine M. Chapleau, Shariff F. Tanious, David R. Diaz & Sarah A. Landsberger

Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

Natalie C. Dattilo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yelena Chernyak .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

Yelena Chernyak, Kristine M. Chapleau, Shariff F. Tanious, Natalie C. Dattilo, David R. Diaz, and Sarah A. Landsberger declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All applicable human rights were honored during the writing of this manuscript.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this case report.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chernyak, Y., Chapleau, K.M., Tanious, S.F. et al. Olfactory Reference Syndrome: A Case Report and Screening Tool. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 28 , 344–348 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09721-9

Download citation

Published : 29 April 2020

Issue Date : June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09721-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Olfactory reference syndrome

- Psychiatric disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- Delusional disorders

- Obsessive–compulsive disorder

- Jikoshu-kyofu

- Taijin-kyofu

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 04 December 2023

Olfactory reference disorder—a review

- Savitha Soman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4866-372X 1 &

- Rajesh Nair 2

Middle East Current Psychiatry volume 30 , Article number: 95 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

894 Accesses

Metrics details

Olfactory Reference Disorder (ORD) is a known clinical entity for several decades; however, it is only in ICD 11 that it has found its niche. Long considered a delusional disorder, it is currently classified as an obsessive–compulsive (OC) spectrum disorder.

ORD is characterised by an erroneous conviction that the body is emitting an unpleasant smell. Patients harbour referential thinking, practise rituals to eliminate or mask the perceived odour, and avoid social interactions. While the conviction can be at a delusional level in some patients, the preoccupation has an obsessive quality in others. The level of insight can be varied. Patients present to mental health settings after traversing a long pathway of care comprising of various specialists. Medical and psychiatric conditions which can present with ORD-like symptoms need to be ruled out. Establishing a therapeutic alliance is the first step in management. There are no randomised controlled trials comparing treatment options in ORD. Antidepressants, antipsychotics, and their combinations have been used with varying degrees of success, in addition to psychotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. Data on prognosis is limited.

Introduction

Of the five senses that man is blessed with, smell, taste, and touch have always been accorded a backseat to sight and hearing. This applies to psychopathology as well where problems related to smell are often overlooked. A good example is that of olfactory reference disorder (ORD) or olfactory reference syndrome (ORS) as it used to be popularly called. Olfactory reference disorder is defined as a condition “in which one believes that his or her body emits a foul odour that makes people react in a negative way to their body” [ 1 ]. The presentation encompasses an overlapping phenomenology of overvalued ideas, delusions, somatic preoccupations, anxiety, and obsessive phenomena; hence, slotting it into a particular diagnostic category has been wrought with controversies. The theory that bodily odour is normal and that ORD may represent a higher intensity in its dimension has added to the confusion. ORD in its classical form or as an isolated body odour symptom of another disorder is a common clinical presentation. Though prevalence statistics for the disorder are available in literature, most studies also attach a disclaimer stating that these values are probably underestimated. Hence, the magnitude of this condition is presumably much higher than what is generally quoted. Patients suffer from intense embarrassment and personal distress and turn into social recluses because of ORD. There is also an associated risk of self-harm. Though the condition came to clinical attention several decades ago, our knowledge of the various treatment options remains restricted to case reports and case series. ORD has now been recognised as a prominent psychiatric condition and has found its niche in the recent versions of the classificatory systems.

The aim of this review is to provide an overview of olfactory reference disorder, covering the definition, evolution of the concept and classification, epidemiology, psychopathology and clinical features, comorbidities, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, assessment, treatment, and prognosis.

Evolution of the concept and classification

Descriptions of a clinical condition that resembles the current day ORS date to the 1800s, with cases being reported from Asia, Africa, the USA, Europe, and the Middle East. Several of these were then described as schizophrenia, though they did not meet the full criteria for the disorder. We owe the clinical description and the term olfactory reference syndrome to Pryse-Philips who proposed the same after analysing a large case series [ 1 ]. The condition has received several other monikers, chiefly, parosmia [ 2 ], hallucinations of smell [ 1 ], chronic olfactory paranoid syndrome [ 3 ], and monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis [ 4 ]. It was predominantly conceptualised as a type of delusional disorder [ 5 ].

Despite the clear existence of ORS, it had not been classified separately as a disorder in the earlier versions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

In the DSM IIIR, it is described as a common presentation of a “delusional disorder, somatic type”. The DSM IV TR and ICD 10 continued this tradition; the term ORS is not included in either of them. DSM IV makes a reference to ORS in the section on social phobia as well as under its culture-bound syndrome section, with specific mention of the Taijin Kyofusho of Japan [ 5 ].

However, a seminal paper that published a systematic review of 84 cases reported in existing literature, while supporting the existence of ORS, questioned its validity as a delusional disorder. The authors put forth the argument that while the conviction held by some patients (57%) amounts to a delusional level, not all cases are delusional (43%). They posited that the position of the ORS needs to be reconsidered in future classificatory systems [ 6 ].

Despite there being a proposal to include ORD as a separate disorder in the DSM 5, it only achieved a mention under the category “other specified obsessive–compulsive and related disorders”, with a specific mention of the culture-bound variant (Taijin Kyofusho).

ORD has finally come into its own in the ICD 11. It has merited a separate category with a code (6B22) under obsessive–compulsive and related disorders. Furthermore, it has been granted additional insight specifiers (fair to good, poor to absent insight and unspecified).

Another debate that has ranged since long is whether ORD must be classified categorically as a separate entity or conceptualised as a dimensional construct, considering its boundary with normal body odour concerns. One study that attempted to make this distinction assessed a mixed sample of 757 individuals (both community and student participants). Three independent taxometric procedures were conducted on three indicators derived from the Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale Modified for olfactory reference syndrome, namely, ORD obsessions, ORD compulsions, and avoidance. Two of the three revealed a dimensional rather than a categorical structure of ORD. The researchers suggested that in clinical practice, it would be better to view ORD as a dimensional concept while assessing and planning treatment [ 7 ].

Besides, though the neurobiology of ORD as a separate disorder has been poorly researched, an integrated neurobiological approach has been proposed [ 8 ]. ORD incorporates symptoms of various phenomenological types, and it is known that an overlapping circuitry is implicated in the neurobiology of trauma reactions, OCD, and psychotic spectrum disorders. This model also lends credence to the viewing of the ORD phenomenology as dimensional rather than categorical.

The classification of ORD has been summarised in Table 1 .

Epidemiology

The community prevalence of olfactory reference disorder ranges from 0.5 to 2.1%; however, since most of these values are based on self-report of body odour concerns, it is probably a far from accurate value [ 5 ]. There appears to be underreporting from developing nations as well [ 9 ].

Women are affected more, in addition to single individuals. The onset is most often in the mid-twenties [ 6 , 10 ], with some case reports suggesting an earlier age of onset [ 11 ].

The most frequently seen personality traits in these individuals (67%) correspond to the cluster C of the DSM (anxious, perfectionistic, and dependent) [ 6 ]. There is limited evidence to show that some of these patients may have a family history of schizophrenia [ 12 ].

Most patients reach a mental health setting only through a long pathway of care encompassing dentists, dermatologists, gastroenterologists, and, sometimes, even the surgical specialties [ 13 , 14 ]. The delay in clinical care is due to the embarrassing nature of the symptom. If ORD is associated with poor or absent insight, it delays treatment seeking even further.

Psychopathology and clinical features

The core symptom in ORD is a preoccupation with the erroneous belief that one’s body is emitting an offensive smell. Phenomenologically, these beliefs range from overvalued ideas to delusions [ 15 ]. The constant preoccupation also has an obsessive quality to it. The patient describes the odour as foul. One or several body parts may be held responsible as the source of the odour, commonly reported ones being the mouth, axillae, feet, and genital regions. The source may change over time. Rarely, patients report of non-bodily odours such as that of ammonia [ 2 ] or detergent [ 16 ]. Sometimes, the patient may be unable to pinpoint an exact region as the source of smell. The odour is reported to be present all the time. Half of the patients complain of being able to smell the foul odour [ 6 ]. Insight may be varied. In the systematic review previously quoted, 49% of the reports mention a precipitating event/statement, which while appearing to be incongruous at the time seemed to set the patients on a morbid course. These were chiefly smell-related negative experiences (85%) and less often unrelated sources of stress (17%). Common examples reported by patients include “an older sibling quipping that his feet smelled, a colleague turning away once or twice during a conversation, housemates teasing her for breaking wind, had an episode of halitosis during a severe throat infection, etc.” [ 6 ].

In keeping with the name, the belief is also accompanied by referential ideas (74%) that are sometimes of a delusional intensity. They often misinterpret other peoples’ actions, e.g. a couple of colleagues sniffed or took their handkerchiefs out when he was nearby, she was gifted a perfume for her birthday by her classmates, a vacant seat next to her on a bus was not claimed by anybody though the bus was full, friends stopped talking soon as she appeared in the distance, hence they probably had been discussing that she stank, etc. [ 6 ].

As a result, these patients often suffer from intense social anxiety; they avoid close relationships and social contacts or endure them with high levels of embarrassment and distress. In severe cases, they may become house bound [ 6 ].

There are repeated behaviours aimed at checking for, camouflaging, or eliminating the odour that these patients perceive. These could include multiple baths, ritualistic grooming, using deodorants or powder excessively, chewing gum or mints, and making drastic changes in diet. These are often time consuming and add to the social and occupational dysfunction [ 12 ].

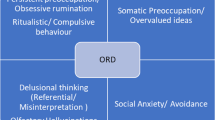

The range of psychopathology seen in ORD is summarised in Fig. 1 .

The range of psychopathology in ORD

A 2011 study of 20 patients diagnosed with ORD assessed them using semi structured measures to gather information about demographic and clinical features. Women constituted 60% of the sample, the mean age being 33.4 ± 14.1 years. The most common sources of the odour were reported from mouth (75%), armpits (60%), and genitals (35%). Delusional ORS beliefs and olfactory hallucinations were the most common (85%) followed by referential thinking (77%). Ninety-five percent of the patients reported repetitive behaviours. Fifty-three percent had undergone psychiatric hospitalisation for the symptoms, 68% reported suicidal ideation, while 32% had a history of attempts at self-harm. Forty-four percent had sought treatment from non-mental health specialists; the treatments received were reported as unhelpful in alleviation of symptoms [ 10 ].

Another Internet-based study that attempted to showcase the phenomenology of ORD obtained data from 253 subjects over a 3-month period in the year 2010. The participants were assessed using questionnaires that were specific to symptoms reported, along with the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS), Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale Modified for ORS (ORS-YBOCS), and Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS). The age of onset of the illness was found to be an average of 21.1 years, more than half had a chronic course. The source of the odours were the armpits, feet, and breasts. The nature of the odours commonly reported related to stool, garbage, and ammonia. Eighteen percent had poor insight; 64% reported referential delusions. Almost all the patients spent time in repetitive rituals to reduce or hide the perceived odour. Women had greater illness severity. Severity was also associated with poor insight and impairment in work and social relationships [ 17 ].

Comorbidities

Major depression is frequently comorbid, both anxiety and depressive symptoms being prominent in about 40% of patients, often as a reaction to the ORD [ 10 ]. Up to 30% of the patients attempt self-harm, and more than half require hospitalization [ 6 ]. Other comorbid conditions include obsessive–compulsive disorder [ 18 ], social anxiety disorder [ 5 ], body dysmorphic disorder [ 10 ], and substance use disorders [ 10 ].

The frequency of occurrence of these comorbidities is depicted in Table 2 .

According to the ICD-11 criteria, the essential features required to diagnose olfactory reference disorder include the following:

“Persistent preoccupation about emitting a foul or offensive body odour or breath (i.e. halitosis) that is either unnoticeable or slightly noticeable to others such that the individual’s concerns are markedly disproportionate to the smell, if any is perceptible

Excessive self-consciousness about the perceived odour, often including ideas of self-reference (i.e. the conviction that people are taking notice, judging, or talking about the odour)

The preoccupation or self-consciousness is accompanied by any of the following: repetitive and excessive behaviours, such as repeatedly checking for body odour or checking the perceived source of the smell (e.g. clothing), or repeatedly seeking reassurance; excessive attempts to camouflage, alter, or prevent the perceived odour (e.g. using perfume or deodorant, repetitive bathing, brushing teeth, or changing clothing, avoidance of certain foods); marked avoidance of social or other situations or stimuli that increase distress about the perceived foul or offensive odour (e.g. public transportation or other situations of close proximity to other people)

The symptoms are not a manifestation of another medical condition and are not due to the effects of a substance or medication on the central nervous system, including withdrawal effects

The symptoms result in significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. If functioning is maintained, it is only through significant additional effort.”

Differential diagnosis

Several medical illnesses may present with a body odour that is objectively verifiable. Common ones include those related to the skin (hyperhidrosis), oral cavity (halitosis and dental abscesses), genital areas (rectal fistulae), and metabolic causes (trimethylaminuria). If the classical features of ORD are not met, then an underlying cause should be considered. Rarely, circumscribed ORD presentations may be a result of illnesses like temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), arteriovenous malformations, and Parkinson’s disease. Associated olfactory hallucinations are rarely reported in ORD, and their presence must raise the suspicion of a TLE [ 19 ].

Psychiatric differentials include body dysmorphic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and other delusional disorders of the somatic type. Rarely, a major depression with psychotic symptoms, bodily distress disorder, or an avoidant personality disorder can also present with ORD-like features [ 20 ].

A boundary with normality needs to be considered especially in cultures where fear of emitting offensive odours is a known entity. Both the ICD 11 and the DSM 5 allude to these cultural presentations. One such condition that is popularly described from Japan, Korea, and certain other cultures is the Taijin Kyofusho (Kyofu-fear and Taijin-interpersonal relationships). It is akin to social anxiety and is characterised by an extreme fear that one may offend, hurt, or embarrass others by awkward or unacceptable social behaviour, body movements, or appearance. These could include beliefs about blushing, eye contact, or offensive body odour. The one related to body odour is termed as Jikoshu-Kyofu (Jiko: oneself; Shu: odour, Kyofu: fear).

A study [ 21 ] undertaken in 2004 aimed to clarify the relationship between the Japanese Jikoshu-Kyofu and the Western ORD. A series of seven cases were analysed with specific emphasis on phenomenology and treatment. The researchers found that symptoms, insight, and drug response in the cultural variant were found to be identical to ORD, except when the onset of symptoms had been at a relatively younger age. They questioned the validity of the Jikoshu-Kyofu as a culturally distinctive disorder.

In yet another study from Japan [ 22 ], the authors attempted to trace a possible causal relationship among social anxiety, ORS, pathologic halitosis, and preoccupation with bodily smells. One thousand three hundred sixty female students (19.6 ± 1.1 years) were assessed using a self-administered questionnaire. Statistically significant differences in the results for ORS and social anxiety ( P < 0.001) were found among the various severity grades of pathologic subjective halitosis. Participants with greater severity of pathologic subjective halitosis were found to be more preoccupied with body and mouth odours ( P < 0.05). It was found that social anxiety has a direct influence on both pathologic subjective halitosis and ORS.

Olfactory reference disorder can be differentiated from regular or culture-bound concerns of body odour by the extent of preoccupation, frequency of related rituals carried out, and the severity of distress or interference the individual experiences because of his/her symptoms.

A recent paper [ 23 ] on a case series of four patients with ORS has presented some very interesting findings. The authors measured the olfactory function of the patients using a “University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test”. They found that all the patients had a genuine smell impairment, like that observed in patients who have dysosmia or phantosmia due to olfactory epithelium damage. Based on their novel findings, the authors speculated that patients with ORS may have an actual smell perception difficulty.

A detailed clinical history taking will yield the symptoms necessary to make a diagnosis of olfactory reference disorder. If the presentation is atypical, relevant investigations need to be done to rule out underlying medical causes, e.g. an EEG when temporal lobe epilepsy is suspected.

A set of simple screening questions [ 24 ] can help uncover symptoms of ORD. “1. Are you very much concerned about your body odour? 2. Do you spend a lot of time worrying about your body odour? 3. Do you believe that other people perceive the body odour and take special notice of it? 4. Do you have urges to repeatedly do something to reduce the body odour? 5. Do you avoid certain situations due to this body odour? 6. Do these concerns affect your mood or daily life activities?”.

Rating scales that have been commonly employed include the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS) [ 25 , 26 ] which is a seven item clinician administered instrument that assesses insight or delusional thinking across several psychiatric conditions, The Yale Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale modified for ORD [ 27 , 28 ] which is a 12-item clinician-rated scale that assesses the severity of the ORD, and the Structured Clinical Interview for identifying disorders of the Obsessive–Compulsive Spectrum (SCID-OCSD) [ 29 ].

The available literature on treatment of ORD is restricted mainly to case reports and case series. There are no randomised controlled trials on the use of psychotropics in ORD. There have been reports of specialists using antidepressants of various classes [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ], both typical and atypical antipsychotics [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ], as well as combinations of antipsychotics and antidepressants [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Various degrees of success have been reported with individual and combination therapy. However, there is no investigational proof of whether combined or sequential treatment leads to a more favourable outcome.

Regarding non-pharmacological treatment, case studies have documented response to various modalities, commonly behavioural techniques [ 45 ], eye movement desensitization and reprocessing [ 46 ], and cognitive behavioural therapy [ 47 , 48 , 49 ]. There have also been reports of patients improving with only psychotherapy [ 6 ].

There have also been case reports of patients showing improvement after a course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was added to existing pharmacological management [ 50 ].

The systematic review [ 6 ] quoted in the article found that 33% of the patients improved with antipsychotic agents, while 55% responded well to antidepressant therapy. Only one in five cases showed symptom reduction with ECT, leucotomy did not have any effect on symptoms, and 78% improved with psychotherapy and 45% with varying combinations of treatment options. This lent further support to their argument that ORD must not be considered a delusional disorder.

Given the fact that the perception of the odour is considered a “physical” symptom by the sufferers, most of them may be reluctant to accept the need for psychiatric treatment. This is more pronounced when the ORS is associated with poor insight. However, most sufferers accept that the symptom is distressing and hampers their quality of life. Hence, the first step in offering treatment would be to establish a therapeutic rapport with the patient. The clinician needs to validate the patient’s symptom and, more importantly, the suffering endured. Patients are more likely to accept medications and therapy when offered to alleviate distress and anxiety rather than as a measure to stop the odour.

Data on prognosis of the condition is limited. Case reports and series have not measured treatment outcome or response in a uniform manner; some have relied on rating instruments, while others have simply commented on the symptoms that improved; each has used a different period from start of treatment to document response. Comorbidities have not been systematically examined while reporting response to treatment. In the 2011 systematic review [ 6 ], reduction in the olfactory symptoms was considered as recovery (complete or partial), while reduced preoccupation with the smell and interference in daily life activities was documented as improvement. Of the 84 cases assessed, 76 reported outcome data ranging from 2-week to 10-year follow-up period (average of 21 months). The authors found that 30% of the patients had recovered, 37% showed improvement, and 33% either continued to fare the same or worsened.

Olfactory reference syndrome is a commonly reported clinical condition which can present with varying degrees of insight. Sometimes, the severity of the conviction is almost delusional; at other times, it can present like an overvalued idea or with an associated obsessive component. Researchers have also attempted to view it as a dimensional concept, where concerns about normal body odour are intensified. Cultural variants have been described with components of associated social anxiety. Patients remain preoccupied with the perceived foul smell, often harbour ideas of reference, engage in repeated rituals to cleanse themselves of the odour, experience intense distress because of this condition, and suffer significant impairment in their social and occupational milieu. Like its nosological status, the treatment options also do not seem to be clear cut or conventionally defined. What appears to help the most is the establishment of a strong therapeutic alliance. Several classes of psychotropics alone and in combination have been tried with varying degrees of success, in addition to psychotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. We need randomised controlled trials to get a clear understanding of effective treatment options.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were created or analysed in this review.

Abbreviations

Olfactory Reference Disorder

Olfactory Reference Syndrome

International Classification of Diseases

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales

Yale-Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale Modified for ORS

Work and Social Adjustment Scale

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Electro-encephalogram

Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale

Structured Clinical Interview for identifying disorders of the Obsessive–Compulsive Spectrum

Electroconvulsive therapy

Pryse-Phillips W (1971) An olfactory reference syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 47:484–509

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tilley H (1895) Three cases of parosmia: causes, treatment, & C. The Lancet 146(3763):907–908

Google Scholar

Videbech T (1966) Chronic olfactory paranoid syndromes. Acta Psychiatr Scand 42(2):183–213

Munro A (1988) Monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 153:37–40

Feusner JD, Phillips KA, Stein DJ (2010) Olfactory reference syndrome: issues for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety 27(6):592–599

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Begum M, McKenna PJ (2011) Olfactory reference syndrome: a systematic review of the world literature. Psychol Med 41:453–461

Ren F, Zhou R, Zhou X, Schneider SC, Storch EA (2020) The latent structure of olfactory reference disorder symptoms: a taxometric analysis. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 27:100583

Skimming KA, Miller CWT (2019) Transdiagnostic approach to olfactory reference syndrome: neurobiological considerations. Harv Rev Psychiatry 27(3):193–200

PubMed Google Scholar

Osman AA (1991) Monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis in developing countries. Br J Psychiatry 159(3):428–431

Phillips KA, Menard W (2011) Olfactory reference syndrome: demographic and clinical features of imagined body odour. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 33(4):398–406

Ferreira JA, Dallaqua RP, Fontenelle LF, Torres AR (2014) Olfactory reference syndrome: a still open nosological and treatment debate. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 36(6):760–763

Cruzado L, Caceres-Taco E, Calizaya JR (2012) Apropos of an olfactory reference syndrome case. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 40(4):234–8

Miranda-Sivelo A, Bajo-Del Pozo C, Fructuoso-Castellar A (2013) Unnecessary surgical treatment in a case of olfactory reference syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35(6):683–684

Aydin M, Harvey-Woodworth CN (2014) Halitosis: a new definition and classification. Br Dent J 217(1):1–10

Jesus G, Gama Marques J, Durval R (2014) EPA-0909 – a review of olfactory reference syndrome about a series of clinical cases. Eur Psychiatry 29:1

Ross CA, Siddiqui AR, Matas M (1987) DSM-III: problems in diagnosis of paranoia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Can J Psychiatry 32(2):146–148

Greenberg JL, Shaw AM, Reuman L, Shwartz R, Wilhelm S (2016) Clinical features of olfactory reference syndrome: an Internet -based study. J Psychosom Res 80:11–16

Zerzinski M, Burdzik M, Zmuda R, Debski P, Witkowska- Berek A et al (2023) Olfactory obsessions: a study of prevalence and phenomenology in the course of obsessive - compulsive disorder. J Clin Med 12(9):3081

Chen C, Shih YH, Yen DJ, Lirng JF, Guo YC, Yu HY, Yiu CH (2003) Olfactory auras in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 44(2):257–260

Lochner C, Stein DJ (2003) Olfactory reference syndrome: diagnostic criteria & differential diagnosis. J Postgrad Med 49(4):328–331

Suzuki K, Takei N, Iwata Y, Sekine Y, Toyoda T, Nakamura K, Mori N (2004). Do olfactory reference syndrome and Jiko-shu-kyofu (a subtype of Taijin-kyofu) share a common entity? Acta Psychiatr Scand 109(2):150–155.

Tsuruta M, Takahashi T, Tokunaga M, Iwasaki M, Kataoka S, Kakuta S et al (2017) Relationships between pathologic subjective halitosis, olfactory reference syndrome, and social anxiety in young Japanese women. BMC Psychol 5:7

Tallab H, Sell EA, Bromley SM, Doty RL (2023) A novel perspective on olfactory reference syndrome and associated specified obsessive-compulsive disorders. Ann Case Rep 8(1):1137–1142

Phillips KA, Castle DJ (2007) How to help patients with olfactory reference syndrome. Curr Psychiatr 6(3):49–65

Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, la Ata KD, Rasmussen SA (1998) The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry 155:102

Phillips KA, Hart AS, Menard W, Eisen JL (2013) Psychometric evaluation of the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment 201(7):640–643

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL et al (1989) The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:1006–1011

Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR et al (1989) The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: II. Validity Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:1012–1016

Du Toit PL, van Kradenburg J, Niehaus D, Stein DJ (2001) Comparison of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients with and without comorbid putative obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders using a structured clinical interview. Compr Psychiatry 42:291–300

Brotman AW, Jenike MA (1984) Monosymptomatic hypochondriasis treated with tricyclic antidepressants. Am J of Psychiatry 141(12):1608–1609

CAS Google Scholar

Balaban OD, BOZ G, Senyasar K, Yazar MS, Keyvan A, Eradamlar N (2015) The olfactory reference syndrome treated with escitalopram: a case report. Marmara Med. J 28:120–122

Alhadi AN, Almaghrebi AH (2018) Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of olfactory reference syndrome: a case study. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord 19:23–28

Yoshimura R, Konishi Y, Okamato N, Ikenouchi A (2021) Letter to the Editor: Vortioxetine improved olfactory reference syndrome in a patient with major depressive disorder: a case report. Arch Clin Psychiatry 48(2):128

Ulzen TPM (1993) Letters to the Editor: Pimozide- responsive monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis in an adolescent. Can J Psychiatry 38(2):154–155

Basu D, Bhagat A, Giridhar C, Avasthi A, Kulhara P (1990) Monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis: a clinico-descriptive analysis. Indian J Psychol Med 13(2):147–152

Weintraub E, Robinson C (2000) A case of monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis treated with olanzapine. Ann Clin Psychiatry 12(4):247–249

Nakaya M (2004) Letters to the editor: Olanzapine treatment of monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 26:164–169

Albers AD, Amato I, Albers MW (2018) Olanzapine improved symptoms and olfactory function in an olfactory reference syndrome patient. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci 30(2):164–167

Ikenouchi A, Terao T, Nakamura J (2004) A male case of monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis responding to olanzapine: a case report. Pharmacopsychiatry 37:240–241

Reddy B, Nocera A, de Filippis R, Das S (2022) Two cases of olfactory reference syndrome treated with risperidone. Neuropsychiatric Invest 60(2):49–51

Elmer KB, George RM, Peterson K, Yokota AB, Langley AFB (2000) Therapeutic update: use of risperidone for the treatment of monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis. Journal Am Acad Dermatol 43:683–686

Karia S, Shrivastava S, DeSousa A, Shah N (2013) Olfactory reference syndrome: a case report. Int J Sci Res 2(9):261

Ozten E, Sayar GH, Tufan AE, Cerit C, Dogan O (2013) Olfactory reference syndrome: treated with sertraline and olanzapine. Sch J Med Case Rep 1(2):44–46

Jegede O, Virk I, Cherukupally K, Germain W, Fouron P, Olupona T, Jolayemi A (2018) Case Report: Olfactory reference syndrome with suicidal attempt treated with pimozide and fluvoxamine. Case Rep Psychiatry 2018:1–3. Article ID 7876497. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7876497 .

Milan MA, Kolko DJ (1982) Paradoxical intention in the treatment of obsessional flatulence ruminations. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 13(2):167–172

McGoldrick T, Begum M, Brown KW (2008) EMDR & olfactory reference syndrome: a case series. J EMDR Pract Res 2(1):63–68

Haica C (2021) Olfactory reference syndrome: a case report. Mental Health Human Resilience Int J 5(2):1–7

Martin-Pinchora AL, Antony MM (2011) Successful treatment of olfactory reference syndrome with cognitive behavioral therapy: a case study. Cogn Behav Pract 18:545–554

Zantvoord JB, Vulink N, Denys D (2016) Cognitive behavioural therapy for olfactory reference syndrome: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 77:9–10

Bhagat H, Bendre A, Dikshit R, DeSousa A, Shah N, Karia S (2017) Olfactory reference syndrome treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Annals Indian Psychiatry 1(2):129–131

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

No funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Savitha Soman

Sanjivani Multi-Speciality Hospital, Kollakadavu, Chengannur, Kerala, India

Rajesh Nair

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors have contributed to the literature review and compilation of the article. The manuscript has been read and approved by both the authors, the requirements for authorship have been met, and each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Savitha Soman .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Soman, S., Nair, R. Olfactory reference disorder—a review. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 30 , 95 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00367-5

Download citation

Received : 26 July 2023

Accepted : 15 September 2023

Published : 04 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-023-00367-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Olfactory Reference Syndrome

- Somatic preoccupation

- Ideas of reference

- From the Experts

These articles are about special topics related to OCD and related disorders. For more general information, please visit our "About OCD" section.

Olfactory Reference Syndrome: Problematic Preoccupation with Perceived Body Odor

by Katharine Phillips, MD

This article was initially published in the Winter 2018 edition of the OCD Newsletter .

Kyle is a 37-year-old single white male who believes that he has severe halitosis (bad breath) and flatulence, which makes him “stinky and smelly.” He states, “I know it’s true, because I can smell it, and why would people touch their face, sniff, and move away from me?” To minimize the awful odor that he is certain he emits, Kyle brushes his teeth for about an hour a day, which has damaged his gums and tooth enamel. He gargles with prescription-strength mouthwash about 20 times a day, wears lots of cologne, changes his underwear many times a day, and washes his clothes twice a day. Because he is embarrassed by the “horrible” odor he believes he emits, Kyle avoids most social situations. He does not date and has dropped out of college. Unable to work, he spends most of his time alone in his apartment. He states, “I have to stay alone, because I stink so much, and if I go out people will make fun of me.”

Kyle is experiencing olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), an underrecognized disorder characterized by preoccupation with the false belief that one emits a foul, unpleasant, or offensive body odor. This preoccupation causes significant distress or impairment in functioning (for example, avoidance of social situations). Although people with ORS believe that they really do smell bad, other people cannot detect the odor. ORS usually triggers excessive, repetitive behaviors such as repeatedly checking oneself for body odor, or excessive clothes laundering. As a result of these concerns, social anxiety and social avoidance are usually prominent, and the odor concerns are so distressing and impairing that suicidal thinking and suicide attempts are common (1-6).

ORS has many similarities to body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), which is characterized by distressing or impairing preoccupation with slight or nonexistent flaws in physical appearance, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (2,3,6). Our understanding of ORS and its relationship to other disorders is limited by a lack of research studies. However, ORS is not a new phenomenon; it has been consistently described around the world since the 1800s as a distressing and often severely impairing disorder (2,3,7,8). The largest studies come from Japan, Canada, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, and the United States (1,6,9-13).

DIAGNOSTIC STATUS OF ORS

A Google search of ORS yields approximately 590,000 results, reflecting the public’s interest in this condition. Efforts were made to add ORS to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5 th Edition (DSM-5) (14), but research evidence was considered too limited to include ORS as its own disorder with full diagnostic criteria. Instead, DSM-5 lists ORS as an example of an “Other Specified Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorder” (14). DSM-5 provides a very brief description of ORS’s key clinical features, but does not include full diagnostic criteria or discussion of ORS in the text (14). However, the recently published International Classification of Diseases, 11 th Edition (ICD-11), did add ORS as a new, separate disorder in the chapter of Obsessive-Compulsive or Related Disorders, alongside BDD and OCD (see Box) (15). It is hoped that inclusion of ORS in ICD-11 will foster much-needed research studies and enhance understanding and recognition of this often severe and underrecognized condition.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF ORS

Preoccupation with Perceived Body Odor

Individuals with ORS are excessively preoccupied with the belief that they emit an unpleasant or foul body odor, most commonly bad breath or sweat (see Table 1). They believe that the foul odor emanates from body areas that correspond to the type of odor — for example, bad breath from the mouth or sweat from the armpits or skin. Occasionally, the perceived odor may smell like non-bodily odors, such as ammonia, detergent, or rotten onions. Most — but not all — people with ORS report actually smelling the odor.

Insight and Referential Thinking

Most people with ORS are completely convinced that they actually smell terrible, despite the fact that other people cannot detect an odor; very few recognize that their belief about the body odor is inaccurate (6). The likely explanation for this mistaken perception is that most people with ORS report that they actually smell the odor themselves (see Table 1) (6).

Alternatively, those who do not smell the odor base their belief on a misinterpretation of other people’s comments, gestures, or behaviors. For example, if someone opens a window, touches their nose, moves away, or says “It’s stuffy in here,” people with ORS typically — and mistakenly — believe that their unpleasant body odor is the reason for such behavior (see Table 1). This inaccurate belief that other people are taking special notice of them in a negative way because they smell bad is known as referential thinking (or as ideas or delusions of reference).

Excessive Repetitive Behaviors

People with ORS experience their preoccupation with body odor as highly distressing, and it triggers upsetting feelings such as depressed mood, anxiety, and self-consciousness. For this reason, nearly everyone with ORS feels compelled to perform repetitive behaviors intended to mitigate, check, mask, or reassure themselves about their perceived odor. The most common behaviors are smelling oneself, excessive showering, and frequent clothes changing (see Table 1).

Camouflaging the Perceived Odor

People with ORS attempt to mask the perceived body odor, most often with excessive perfume or powder, chewing gum, excessive or strong deodorant, or mints (see Table 1). This behavior can occur repeatedly throughout the day.

Functional Impairment

ORS typically impairs functioning, which can range from mild to extreme; on average, impairment is severe in clinical samples of individuals with ORS (6). Nearly three-quarters of people with ORS report periods during which they avoided most social interactions because of their ORS symptoms, and about 50% report periods during which they avoided most of their important occupational, academic, or life activities because of ORS symptoms (6) (see Table 1). Some people are completely housebound because they feel too distressed, self-conscious, and embarrassed about the perceived odor to be around other people, or because they fear offending others with their smell.

High rates of psychiatric hospitalization, suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and completed suicide have been reported, which many individuals attribute primarily to their ORS symptoms (see Table 1) (1,6).

Comorbidity

Commonly co-occurring disorders are a major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder, drug or alcohol use disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder (6).

PREVALENCE AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

In one study, 60% of individuals with ORS were female, and most were single (6). The prevalence of ORS is not known, but it is certainly more common than generally recognized (2,3,16).

WHAT CAUSES ORS?

The cause of ORS has not been studied and thus is not known. Like other psychiatric disorders, its cause likely has many genetic and environmental determinants. ORS has similarities to BDD, OCD, and social anxiety disorder, and thus it may share some etiologic and pathophysiologic characteristics with these disorders. For example, ORS may involve abnormalities in the brain’s olfactory system that cause olfactory hallucinations or extreme sensitivity to odors. However, this theory has not been studied, and it likely is not relevant to the minority of those with ORS who do not actually smell the odor.

TREATMENT FOR ORS

No prospective medication studies have been done (either controlled or open-label studies). Case reports and small case series describe improvement with serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) monotherapy, neuroleptic (antipsychotic) monotherapy, non-SRI antidepressants (such as tricyclic antidepressants), or a combination of a neuroleptic and antidepressant medication (2-4). In the author’s clinical experience, SRIs at high doses often effectively treat ORS.

Psychotherapy

Reports on psychotherapy are similarly limited to single case reports and small case series, which report improvement with behavioral therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and paradoxical intention (2-4). In the author’s experience, cognitive behavioral therapy – consisting of cognitive restructuring and advanced cognitive strategies for core beliefs, including self-esteem work and self-compassion; ritual prevention; and exposure-based exercises along with behavioral experiments that are tailored to ORS symptoms – can be effective. ORS’s clinical features appear most similar to those of BDD, and an evidence-based CBT treatment manual for BDD can be easily adapted to treat ORS symptoms (17).

Non-Mental Health Medical Treatment

Nearly half of people with ORS seek non-mental health medical treatment for their perceived body odor (6), many before seeking mental health care (18); in one study, one third of people actually received such treatment (6). Patients may consult dentists, surgeons, and ear, nose, and throat specialists for supposed halitosis; proctologists, surgeons, and gastroenterologists for supposed anal odors; and other physicians such as dermatologists and gynecologists. Treatments such as a tonsillectomy for perceived bad breath or electrolysis of sweat glands for a perceived sweaty smell may be received. Such treatment does not appear to be effective for ORS symptoms and often leaves patients dissatisfied (6).

A neurologic workup, which may include an EEG, may sometimes be warranted to rule out a neurologic explanation (such as temporal lobe epilepsy or migraine aura) for perception of an odor that others cannot detect. This kind of evaluation is more relevant when concerns focus on nonbodily odors and occur only intermittently.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CLINICAL CARE

Current understanding of ORS is substantially limited by the very small number of published research studies on this condition. Nonetheless, it is important for clinicians and the public to be aware of ORS. Table 2 provides some clinical recommendations, based on current research-based knowledge about ORS and the author’s clinical experience. More research studies on all aspects of ORS are greatly needed to advance the understanding and treatment of this condition.

TABLE 1: Key Clinical Features of Olfactory Reference Syndrome

| Clinical Feature | % of Patients, or Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|

| Mouth | 75.00% |

| Armpits | 60.00% |

| Genitalia | 35.00% |

| Anus | 30.00% |

| Feet | 30.00% |

| Skin | 25.00% |

| Groin | 10.00% |

| Hands | 10.00% |

| Head/Scalp | 10.00% |

| Under Breasts | 5.00% |

| Total different # of sources | 2.9 ± 1.4 |

| Bad breath | 75.00% |

| Sweat | 65.00% |

| Other smell | 65.00% |

| Flatulence/Fecal | 30.00% |

| Urine | 20.00% |

| Vaginal | 10.00% |

| Olfactory hallucinations | 85.00% |

| Level of insight (Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale [BABS]) | 20.6 ± 3.7 (delusional/absent insight range) |

| Insight (% with delusional/absent insight on BABS) | 84.60% |

| Referential thinking (ideas or delusions of reference; lifetime) | 88.30% |

| Smelling self | 80.00% |

| Showering | 68.40% |

| Changing clothes | 50.00% |

| Seeking reassurance | 45.00% |

| Dieting/unusual food intake | 45.00% |

| Brushing teeth | 40.00% |

| Laundering clothes | 30.00% |

| Comparing to other people | 30.00% |

| Other behavior | 30.00% |

| At least one compulsive behavior | 95.00% |

| Total # of compulsive behaviors | 4.2 ± 2.0 |

| Perfume/Fragrance/Powder | 70.00% |

| Gum | 60.00% |

| Deodorant | 55.00% |

| Mints | 55.00% |

| Mouthwash | 50.00% |

| Toothpaste | 30.00% |

| Clothes | 25.00% |

| Other6 | 25.00% |

| At least one item used to mask odor | 100.00% |

| Total # of items used to mask odor | 4.0 ± 2.2 |

| Age of ORS onset | 15.6 ± 5.7 |

| ORS onset | |

| One set of odor(s) that started at same time and did not change | 38.90% |

| New odors added to ongoing previous odors | 44.40% |

| Complex additions and remissions of odors | 16.70% |

| Functional Impairment Attributed to ORS (lifetime) | |

| Avoidance of social interactions | 73.70% |

| Avoidance of occupational/academic/role activities | 47.40% |

| Housebound for at least 1 week | 40.00% |

| GAF (Global Assessment of Functioning) (current) | 47.5 ± 13.2 |

| History of suicidal ideation | 68.40% |

| History of suicidal ideation attributed primarily to ORS | 47.40% |

| Attempted suicide | 31.60% |

| Attempted suicide primarily due to ORS | 15.80% |

| History of physical violence | 50.00% |

| History of physical violence attributed primarily to ORS | 21.40% |

| Psychiatric hospitalization | 52.60% |

| Psychiatric hospitalization attributed primarily to ORS | 31.60% |

Table Notes

- Table is adapted from Phillips KA, Menard W. Olfactory reference syndrome: demographic and clinical features of imagined body odor. General Hospital Psychiatry 2011;33:398-406

- Total is greater than 100% because some patients reported multiple odors, odors that emanated from multiple body areas, multiple repetitive behaviors, or multiple masking strategies.

- Other smells were (n=1 for each): “like wearing sanitary napkins too long,” “unpleasant vaginal odor,” ammonia, “bad,” “body odor/mucus/post nasal drip,” “body odor/rotten odor/morning breath,” “hard/unpleasant smell,” “like 5 day-old food and cigarette smoke,” oily-fishy smell,” and “vegetable soup/putrid body (odor).”

- The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale (BABS) classifies false beliefs as characterized by excellent, good, fair, poor, or absent insight/delusional belief (19,20). On the BABS, mean scores for ORS are in the absent insight/delusional range, for BDD are in the poor insight range, and for OCD are in the good insight range.

- Other excessive behaviors were as follows; scrapes tongue/coughs to remove bacteria on tonsils/talks softly/uses feminine wash, scrapes back of tongue/checks tonsils to pull mucous off them, uses spoon to scrape skin on tongue and inside of mouth, checks breath by blowing into nose/drinking water, frequent haircuts/avoids hats, drinks lots of fluids.

- Other items/behaviors used to mask the odor were as follows (n=1 for each); spraying alcohol on self and furniture/wearing heavy underwear, putting cornstarch under feet, putting toilet paper in underwear, crossing legs/putting toilet paper in underwear, using air fresheners.

- The mean GAF score reflects serious symptoms or serious functional impairment.

- Physical violence was defined as motor behavior that physically injured another person or caused significant property damage.

TABLE 2: Key Recommendations for Clinical Practice 1

| Be familiar with ORS and its clinical features; it is more common than generally recognized. |

| Do not assume that ORS is simply a symptom of another psychiatric condition, such as depression, a psychotic disorder, BDD, or OCD; focus specifically on ORS when providing treatment. |

| Screen patients for ORS, especially those with high levels of social anxiety or social avoidance, referential thinking, or performance of the repetitive or camouflaging behaviors in Table 1. |

| For selected patients, consider a neurologic workup to rule out a neurologic explanation for olfactory hallucinations, such as temporal lobe epilepsy. |

| Medication is strongly recommended for patients with more severe ORS symptoms, especially those who are very impaired in terms of functioning, are severely depressed, or are more highly suicidal. Medication is also a good option when symptoms are mild or moderate in severity, especially if co-occurring disorders are present that may respond to similar medication (such as BDD, OCD, social anxiety disorder, or depression). |

| Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors — at high doses if lower doses are not effective — are recommended as the first-line medication for ORS (similar to BDD and OCD). |

| Atypical neuroleptics (such as aripiprazole or risperidone) may potentially be helpful in combination with an SRI (similar to BDD and OCD). These medications should especially be considered if an adequate trial with an SRI is not sufficiently helpful or if problematic agitation, very severe depression, marked impairment in functioning, worrisome suicidal thinking, or suicidal behavior are present. |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy that is tailored to ORS is also recommended, especially for more severe ORS symptoms. It is also a good option when symptoms are mild or moderate in severity. Core components of CBT appear to consist of cognitive therapy, exposure with behavioral experiments, and ritual prevention. |

| Given the presence of obsessions, repetitive behaviors (rituals), poor or absent ORS-related insight, depressive symptoms (usually present), and often-prominent social anxiety and avoidance, CBT for ORS appears most similar to that for BDD. In the author’s experience, an evidence-based treatment manual for BDD can easily be modified to effectively treat ORS17. |

| Many individuals with ORS desire non-mental health medical treatment for ORS concerns, such as removal of sweat glands or a tonsillectomy, which does not appear to be effective. |

| Because ORS-related insight is usually absent (i.e., ORS beliefs are usually delusional in nature), and because many individuals with ORS desire non-mental health medical treatment for ORS concerns, motivational interviewing is often needed to engage and retain patients in mental health treatment. |

Because research evidence on ORS is very limited, these recommendations are also based on the author’s clinical experience with ORS and may change as research studies are done.

Katharine A. Phillips, MD is Professor of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, Cornell University; an Attending Psychiatrist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital; and an Adjunct Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Dr. Phillips is also a member of the IOCDF Scientific and Clinical Advisory Board, a contributing member to the IOCDF www.HelpforBDD.org website, and a regular presenter at the Annual OCD Conference. Please address correspondence to: Katharine Phillips, MD, Weill Cornell Psychiatry Specialty Center, 315 East 62nd Street, New York, NY 10065; Telephone: 646-962-2820; Fax: 646-962-0175; email: [email protected]

- Pryse-Phillips W. (1971). An olfactory reference syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 47:484–509.

- Phillips KA, Gunderson C, Gruber U, Castle DJ. (2006). Delusions of body malodor: the olfactory reference syndrome. In: Brewer W, Castle D, Pantelis C, editors. Olfaction and the Brain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; pp. 334–353.

- Feusner JD, Phillips KA, Stein DJ. (2010). Olfactory reference syndrome: issues for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety, 27:592–599.

- Phillips KA, Castle DJ. (2007). How to help patients with olfactory reference syndrome. Curr Psychiatr, 6:49–65.

- Begum M, McKenna PJ. (2010). Olfactory reference syndrome: a systematic review of the world literature. Psychol Med, 1–9.

- Phillips KA, Menard W. (2011). Olfactory reference syndrome: demographic and clinical features of imagined body odor. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 33:398-406.

- Potts CS. (1891). Two cases of hallucination of smell. U Penn Med Mag, 226.

- Tilley H. (1895). Three cases of parosmia: causes and treatment. Lancet, 907–908.

- Yamada M, Shigemoto T, Kashiwamura KI, Nakamura Y, Ota T. (1977). Fear of emitting bad odors. Bull Yam Med School, 24:141–161.

- Prazeres AM, Fontenelle LF, Mendlowicz MV, de Mathis MA, Ferrão YA, de Brito NF, et al. (2010). Olfactory reference syndrome as a subtype of body dysmorphic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 71:87–89.

- Iwu CO, Akpata O. (1990). Delusional halitosis. Review of the literature and analysis of 32 cases. Br Dent J, 168:294–296.

- Osman AA. (1991). Monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis in developing countries. Br J Psychiatry, 159:428–431

- Greenberg J, Shaw AM, Reuman L, Schwartz R, Wilhelm S. (2016). Clinical features of olfactory reference syndrome: an internet-based study. J Psychosom Res, 80:11-6.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5 th Edition. (2013). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association.

- https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1119008568

16. Zhou X, Schneider SC, Cepeda SL, Storch EA. (2018). Olfactory reference syndrome symptoms in Chinese university students: Phenomenology, associated impairment, and clinical correlates. Compr Psychiatry, 86:91-95.

17. Wilhelm S, Phillips KA, Steketee G. (2013). Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Treatment Manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Greenberg JL, Berman NC, Braddick V, Schwartz R, Mothi SS, Wilhelm S. (2018). Treatment utilization and barriers to treatment among individuals with olfactory reference syndrome (ORS). J Psychosom Res, 105:31-36.

- Eisen JL, Phillips KA, Baer L, Beer DA, Atala KD, Rasmussen SA. (1998). The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry, 155:102-108.

- Phillips KA, Hart A, Menard W, Eisen JL. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis, 201:640-643.

In This Section

More resources.

- Fact Sheets & Brochures

- Books About OCD

- Educational Resources

Search iocdf.org

Your gift has the power to change the life of someone living with ocd..

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Olfactory Reference Syndrome: Issues for DSM-V

Jamie d. feusner.

1 Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, USA

Katharine A. Phillips

2 Butler Hospital and the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, USA

Dan J. Stein

3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Cape Town, South Africa