What Is Research Methodology? A Plain-Language Explanation & Definition (With Examples)

By Derek Jansen (MBA) and Kerryn Warren (PhD) | June 2020 (Last updated April 2023)

If you’re new to formal academic research, it’s quite likely that you’re feeling a little overwhelmed by all the technical lingo that gets thrown around. And who could blame you – “research methodology”, “research methods”, “sampling strategies”… it all seems never-ending!

In this post, we’ll demystify the landscape with plain-language explanations and loads of examples (including easy-to-follow videos), so that you can approach your dissertation, thesis or research project with confidence. Let’s get started.

Research Methodology 101

- What exactly research methodology means

- What qualitative , quantitative and mixed methods are

- What sampling strategy is

- What data collection methods are

- What data analysis methods are

- How to choose your research methodology

- Example of a research methodology

What is research methodology?

Research methodology simply refers to the practical “how” of a research study. More specifically, it’s about how a researcher systematically designs a study to ensure valid and reliable results that address the research aims, objectives and research questions . Specifically, how the researcher went about deciding:

- What type of data to collect (e.g., qualitative or quantitative data )

- Who to collect it from (i.e., the sampling strategy )

- How to collect it (i.e., the data collection method )

- How to analyse it (i.e., the data analysis methods )

Within any formal piece of academic research (be it a dissertation, thesis or journal article), you’ll find a research methodology chapter or section which covers the aspects mentioned above. Importantly, a good methodology chapter explains not just what methodological choices were made, but also explains why they were made. In other words, the methodology chapter should justify the design choices, by showing that the chosen methods and techniques are the best fit for the research aims, objectives and research questions.

So, it’s the same as research design?

Not quite. As we mentioned, research methodology refers to the collection of practical decisions regarding what data you’ll collect, from who, how you’ll collect it and how you’ll analyse it. Research design, on the other hand, is more about the overall strategy you’ll adopt in your study. For example, whether you’ll use an experimental design in which you manipulate one variable while controlling others. You can learn more about research design and the various design types here .

Need a helping hand?

What are qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods?

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods are different types of methodological approaches, distinguished by their focus on words , numbers or both . This is a bit of an oversimplification, but its a good starting point for understanding.

Let’s take a closer look.

Qualitative research refers to research which focuses on collecting and analysing words (written or spoken) and textual or visual data, whereas quantitative research focuses on measurement and testing using numerical data . Qualitative analysis can also focus on other “softer” data points, such as body language or visual elements.

It’s quite common for a qualitative methodology to be used when the research aims and research questions are exploratory in nature. For example, a qualitative methodology might be used to understand peoples’ perceptions about an event that took place, or a political candidate running for president.

Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and research questions are confirmatory in nature. For example, a quantitative methodology might be used to measure the relationship between two variables (e.g. personality type and likelihood to commit a crime) or to test a set of hypotheses .

As you’ve probably guessed, the mixed-method methodology attempts to combine the best of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to integrate perspectives and create a rich picture. If you’d like to learn more about these three methodological approaches, be sure to watch our explainer video below.

What is sampling strategy?

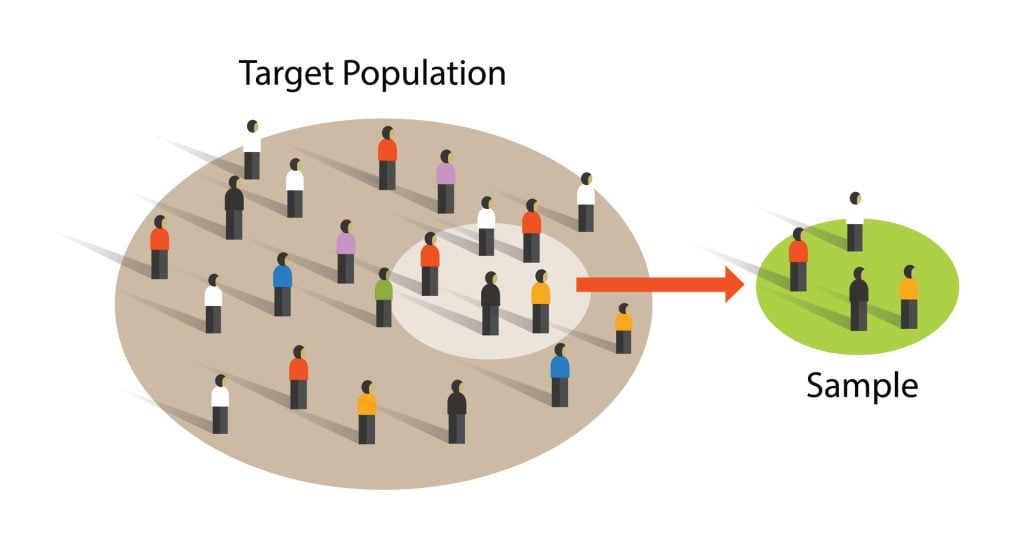

Simply put, sampling is about deciding who (or where) you’re going to collect your data from . Why does this matter? Well, generally it’s not possible to collect data from every single person in your group of interest (this is called the “population”), so you’ll need to engage a smaller portion of that group that’s accessible and manageable (this is called the “sample”).

How you go about selecting the sample (i.e., your sampling strategy) will have a major impact on your study. There are many different sampling methods you can choose from, but the two overarching categories are probability sampling and non-probability sampling .

Probability sampling involves using a completely random sample from the group of people you’re interested in. This is comparable to throwing the names all potential participants into a hat, shaking it up, and picking out the “winners”. By using a completely random sample, you’ll minimise the risk of selection bias and the results of your study will be more generalisable to the entire population.

Non-probability sampling , on the other hand, doesn’t use a random sample . For example, it might involve using a convenience sample, which means you’d only interview or survey people that you have access to (perhaps your friends, family or work colleagues), rather than a truly random sample. With non-probability sampling, the results are typically not generalisable .

To learn more about sampling methods, be sure to check out the video below.

What are data collection methods?

As the name suggests, data collection methods simply refers to the way in which you go about collecting the data for your study. Some of the most common data collection methods include:

- Interviews (which can be unstructured, semi-structured or structured)

- Focus groups and group interviews

- Surveys (online or physical surveys)

- Observations (watching and recording activities)

- Biophysical measurements (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, etc.)

- Documents and records (e.g., financial reports, court records, etc.)

The choice of which data collection method to use depends on your overall research aims and research questions , as well as practicalities and resource constraints. For example, if your research is exploratory in nature, qualitative methods such as interviews and focus groups would likely be a good fit. Conversely, if your research aims to measure specific variables or test hypotheses, large-scale surveys that produce large volumes of numerical data would likely be a better fit.

What are data analysis methods?

Data analysis methods refer to the methods and techniques that you’ll use to make sense of your data. These can be grouped according to whether the research is qualitative (words-based) or quantitative (numbers-based).

Popular data analysis methods in qualitative research include:

- Qualitative content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Narrative analysis

- Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)

- Visual analysis (of photographs, videos, art, etc.)

Qualitative data analysis all begins with data coding , after which an analysis method is applied. In some cases, more than one analysis method is used, depending on the research aims and research questions . In the video below, we explore some common qualitative analysis methods, along with practical examples.

Moving on to the quantitative side of things, popular data analysis methods in this type of research include:

- Descriptive statistics (e.g. means, medians, modes )

- Inferential statistics (e.g. correlation, regression, structural equation modelling)

Again, the choice of which data collection method to use depends on your overall research aims and objectives , as well as practicalities and resource constraints. In the video below, we explain some core concepts central to quantitative analysis.

How do I choose a research methodology?

As you’ve probably picked up by now, your research aims and objectives have a major influence on the research methodology . So, the starting point for developing your research methodology is to take a step back and look at the big picture of your research, before you make methodology decisions. The first question you need to ask yourself is whether your research is exploratory or confirmatory in nature.

If your research aims and objectives are primarily exploratory in nature, your research will likely be qualitative and therefore you might consider qualitative data collection methods (e.g. interviews) and analysis methods (e.g. qualitative content analysis).

Conversely, if your research aims and objective are looking to measure or test something (i.e. they’re confirmatory), then your research will quite likely be quantitative in nature, and you might consider quantitative data collection methods (e.g. surveys) and analyses (e.g. statistical analysis).

Designing your research and working out your methodology is a large topic, which we cover extensively on the blog . For now, however, the key takeaway is that you should always start with your research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread). Every methodological choice you make needs align with those three components.

Example of a research methodology chapter

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of a research methodology from an actual dissertation, as well as an overview of our free methodology template .

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

198 Comments

Thank you for this simple yet comprehensive and easy to digest presentation. God Bless!

You’re most welcome, Leo. Best of luck with your research!

I found it very useful. many thanks

This is really directional. A make-easy research knowledge.

Thank you for this, I think will help my research proposal

Thanks for good interpretation,well understood.

Good morning sorry I want to the search topic

Thank u more

Thank you, your explanation is simple and very helpful.

Very educative a.nd exciting platform. A bigger thank you and I’ll like to always be with you

That’s the best analysis

So simple yet so insightful. Thank you.

This really easy to read as it is self-explanatory. Very much appreciated…

Thanks for this. It’s so helpful and explicit. For those elements highlighted in orange, they were good sources of referrals for concepts I didn’t understand. A million thanks for this.

Good morning, I have been reading your research lessons through out a period of times. They are important, impressive and clear. Want to subscribe and be and be active with you.

Thankyou So much Sir Derek…

Good morning thanks so much for the on line lectures am a student of university of Makeni.select a research topic and deliberate on it so that we’ll continue to understand more.sorry that’s a suggestion.

Beautiful presentation. I love it.

please provide a research mehodology example for zoology

It’s very educative and well explained

Thanks for the concise and informative data.

This is really good for students to be safe and well understand that research is all about

Thank you so much Derek sir🖤🙏🤗

Very simple and reliable

This is really helpful. Thanks alot. God bless you.

very useful, Thank you very much..

thanks a lot its really useful

in a nutshell..thank you!

Thanks for updating my understanding on this aspect of my Thesis writing.

thank you so much my through this video am competently going to do a good job my thesis

Very simple but yet insightful Thank you

This has been an eye opening experience. Thank you grad coach team.

Very useful message for research scholars

Really very helpful thank you

yes you are right and i’m left

Research methodology with a simplest way i have never seen before this article.

wow thank u so much

Good morning thanks so much for the on line lectures am a student of university of Makeni.select a research topic and deliberate on is so that we will continue to understand more.sorry that’s a suggestion.

Very precise and informative.

Thanks for simplifying these terms for us, really appreciate it.

Thanks this has really helped me. It is very easy to understand.

I found the notes and the presentation assisting and opening my understanding on research methodology

Good presentation

Im so glad you clarified my misconceptions. Im now ready to fry my onions. Thank you so much. God bless

Thank you a lot.

thanks for the easy way of learning and desirable presentation.

Thanks a lot. I am inspired

Well written

I am writing a APA Format paper . I using questionnaire with 120 STDs teacher for my participant. Can you write me mthology for this research. Send it through email sent. Just need a sample as an example please. My topic is ” impacts of overcrowding on students learning

Thanks for your comment.

We can’t write your methodology for you. If you’re looking for samples, you should be able to find some sample methodologies on Google. Alternatively, you can download some previous dissertations from a dissertation directory and have a look at the methodology chapters therein.

All the best with your research.

Thank you so much for this!! God Bless

Thank you. Explicit explanation

Thank you, Derek and Kerryn, for making this simple to understand. I’m currently at the inception stage of my research.

Thnks a lot , this was very usefull on my assignment

excellent explanation

I’m currently working on my master’s thesis, thanks for this! I’m certain that I will use Qualitative methodology.

Thanks a lot for this concise piece, it was quite relieving and helpful. God bless you BIG…

I am currently doing my dissertation proposal and I am sure that I will do quantitative research. Thank you very much it was extremely helpful.

Very interesting and informative yet I would like to know about examples of Research Questions as well, if possible.

I’m about to submit a research presentation, I have come to understand from your simplification on understanding research methodology. My research will be mixed methodology, qualitative as well as quantitative. So aim and objective of mixed method would be both exploratory and confirmatory. Thanks you very much for your guidance.

OMG thanks for that, you’re a life saver. You covered all the points I needed. Thank you so much ❤️ ❤️ ❤️

Thank you immensely for this simple, easy to comprehend explanation of data collection methods. I have been stuck here for months 😩. Glad I found your piece. Super insightful.

I’m going to write synopsis which will be quantitative research method and I don’t know how to frame my topic, can I kindly get some ideas..

Thanks for this, I was really struggling.

This was really informative I was struggling but this helped me.

Thanks a lot for this information, simple and straightforward. I’m a last year student from the University of South Africa UNISA South Africa.

its very much informative and understandable. I have enlightened.

An interesting nice exploration of a topic.

Thank you. Accurate and simple🥰

This article was really helpful, it helped me understanding the basic concepts of the topic Research Methodology. The examples were very clear, and easy to understand. I would like to visit this website again. Thank you so much for such a great explanation of the subject.

Thanks dude

Thank you Doctor Derek for this wonderful piece, please help to provide your details for reference purpose. God bless.

Many compliments to you

Great work , thank you very much for the simple explanation

Thank you. I had to give a presentation on this topic. I have looked everywhere on the internet but this is the best and simple explanation.

thank you, its very informative.

Well explained. Now I know my research methodology will be qualitative and exploratory. Thank you so much, keep up the good work

Well explained, thank you very much.

This is good explanation, I have understood the different methods of research. Thanks a lot.

Great work…very well explanation

Thanks Derek. Kerryn was just fantastic!

Great to hear that, Hyacinth. Best of luck with your research!

Its a good templates very attractive and important to PhD students and lectuter

Thanks for the feedback, Matobela. Good luck with your research methodology.

Thank you. This is really helpful.

You’re very welcome, Elie. Good luck with your research methodology.

Well explained thanks

This is a very helpful site especially for young researchers at college. It provides sufficient information to guide students and equip them with the necessary foundation to ask any other questions aimed at deepening their understanding.

Thanks for the kind words, Edward. Good luck with your research!

Thank you. I have learned a lot.

Great to hear that, Ngwisa. Good luck with your research methodology!

Thank you for keeping your presentation simples and short and covering key information for research methodology. My key takeaway: Start with defining your research objective the other will depend on the aims of your research question.

My name is Zanele I would like to be assisted with my research , and the topic is shortage of nursing staff globally want are the causes , effects on health, patients and community and also globally

Thanks for making it simple and clear. It greatly helped in understanding research methodology. Regards.

This is well simplified and straight to the point

Thank you Dr

I was given an assignment to research 2 publications and describe their research methodology? I don’t know how to start this task can someone help me?

Sure. You’re welcome to book an initial consultation with one of our Research Coaches to discuss how we can assist – https://gradcoach.com/book/new/ .

Thanks a lot I am relieved of a heavy burden.keep up with the good work

I’m very much grateful Dr Derek. I’m planning to pursue one of the careers that really needs one to be very much eager to know. There’s a lot of research to do and everything, but since I’ve gotten this information I will use it to the best of my potential.

Thank you so much, words are not enough to explain how helpful this session has been for me!

Thanks this has thought me alot.

Very concise and helpful. Thanks a lot

Thank Derek. This is very helpful. Your step by step explanation has made it easier for me to understand different concepts. Now i can get on with my research.

I wish i had come across this sooner. So simple but yet insightful

really nice explanation thank you so much

I’m so grateful finding this site, it’s really helpful…….every term well explained and provide accurate understanding especially to student going into an in-depth research for the very first time, even though my lecturer already explained this topic to the class, I think I got the clear and efficient explanation here, much thanks to the author.

It is very helpful material

I would like to be assisted with my research topic : Literature Review and research methodologies. My topic is : what is the relationship between unemployment and economic growth?

Its really nice and good for us.

THANKS SO MUCH FOR EXPLANATION, ITS VERY CLEAR TO ME WHAT I WILL BE DOING FROM NOW .GREAT READS.

Short but sweet.Thank you

Informative article. Thanks for your detailed information.

I’m currently working on my Ph.D. thesis. Thanks a lot, Derek and Kerryn, Well-organized sequences, facilitate the readers’ following.

great article for someone who does not have any background can even understand

I am a bit confused about research design and methodology. Are they the same? If not, what are the differences and how are they related?

Thanks in advance.

concise and informative.

Thank you very much

How can we site this article is Harvard style?

Very well written piece that afforded better understanding of the concept. Thank you!

Am a new researcher trying to learn how best to write a research proposal. I find your article spot on and want to download the free template but finding difficulties. Can u kindly send it to my email, the free download entitled, “Free Download: Research Proposal Template (with Examples)”.

Thank too much

Thank you very much for your comprehensive explanation about research methodology so I like to thank you again for giving us such great things.

Good very well explained.Thanks for sharing it.

Thank u sir, it is really a good guideline.

so helpful thank you very much.

Thanks for the video it was very explanatory and detailed, easy to comprehend and follow up. please, keep it up the good work

It was very helpful, a well-written document with precise information.

how do i reference this?

MLA Jansen, Derek, and Kerryn Warren. “What (Exactly) Is Research Methodology?” Grad Coach, June 2021, gradcoach.com/what-is-research-methodology/.

APA Jansen, D., & Warren, K. (2021, June). What (Exactly) Is Research Methodology? Grad Coach. https://gradcoach.com/what-is-research-methodology/

Your explanation is easily understood. Thank you

Very help article. Now I can go my methodology chapter in my thesis with ease

I feel guided ,Thank you

This simplification is very helpful. It is simple but very educative, thanks ever so much

The write up is informative and educative. It is an academic intellectual representation that every good researcher can find useful. Thanks

Wow, this is wonderful long live.

Nice initiative

thank you the video was helpful to me.

Thank you very much for your simple and clear explanations I’m really satisfied by the way you did it By now, I think I can realize a very good article by following your fastidious indications May God bless you

Thanks very much, it was very concise and informational for a beginner like me to gain an insight into what i am about to undertake. I really appreciate.

very informative sir, it is amazing to understand the meaning of question hidden behind that, and simple language is used other than legislature to understand easily. stay happy.

This one is really amazing. All content in your youtube channel is a very helpful guide for doing research. Thanks, GradCoach.

research methodologies

Please send me more information concerning dissertation research.

Nice piece of knowledge shared….. #Thump_UP

This is amazing, it has said it all. Thanks to Gradcoach

This is wonderful,very elaborate and clear.I hope to reach out for your assistance in my research very soon.

This is the answer I am searching about…

realy thanks a lot

Thank you very much for this awesome, to the point and inclusive article.

Thank you very much I need validity and reliability explanation I have exams

Thank you for a well explained piece. This will help me going forward.

Very simple and well detailed Many thanks

This is so very simple yet so very effective and comprehensive. An Excellent piece of work.

I wish I saw this earlier on! Great insights for a beginner(researcher) like me. Thanks a mil!

Thank you very much, for such a simplified, clear and practical step by step both for academic students and general research work. Holistic, effective to use and easy to read step by step. One can easily apply the steps in practical terms and produce a quality document/up-to standard

Thanks for simplifying these terms for us, really appreciated.

Thanks for a great work. well understood .

This was very helpful. It was simple but profound and very easy to understand. Thank you so much!

Great and amazing research guidelines. Best site for learning research

hello sir/ma’am, i didn’t find yet that what type of research methodology i am using. because i am writing my report on CSR and collect all my data from websites and articles so which type of methodology i should write in dissertation report. please help me. i am from India.

how does this really work?

perfect content, thanks a lot

As a researcher, I commend you for the detailed and simplified information on the topic in question. I would like to remain in touch for the sharing of research ideas on other topics. Thank you

Impressive. Thank you, Grad Coach 😍

Thank you Grad Coach for this piece of information. I have at least learned about the different types of research methodologies.

Very useful content with easy way

Thank you very much for the presentation. I am an MPH student with the Adventist University of Africa. I have successfully completed my theory and starting on my research this July. My topic is “Factors associated with Dental Caries in (one District) in Botswana. I need help on how to go about this quantitative research

I am so grateful to run across something that was sooo helpful. I have been on my doctorate journey for quite some time. Your breakdown on methodology helped me to refresh my intent. Thank you.

thanks so much for this good lecture. student from university of science and technology, Wudil. Kano Nigeria.

It’s profound easy to understand I appreciate

Thanks a lot for sharing superb information in a detailed but concise manner. It was really helpful and helped a lot in getting into my own research methodology.

Comment * thanks very much

This was sooo helpful for me thank you so much i didn’t even know what i had to write thank you!

You’re most welcome 🙂

Simple and good. Very much helpful. Thank you so much.

This is very good work. I have benefited.

Thank you so much for sharing

This is powerful thank you so much guys

I am nkasa lizwi doing my research proposal on honors with the university of Walter Sisulu Komani I m on part 3 now can you assist me.my topic is: transitional challenges faced by educators in intermediate phase in the Alfred Nzo District.

Appreciate the presentation. Very useful step-by-step guidelines to follow.

I appreciate sir

wow! This is super insightful for me. Thank you!

Indeed this material is very helpful! Kudos writers/authors.

I want to say thank you very much, I got a lot of info and knowledge. Be blessed.

I want present a seminar paper on Optimisation of Deep learning-based models on vulnerability detection in digital transactions.

Need assistance

Dear Sir, I want to be assisted on my research on Sanitation and Water management in emergencies areas.

I am deeply grateful for the knowledge gained. I will be getting in touch shortly as I want to be assisted in my ongoing research.

The information shared is informative, crisp and clear. Kudos Team! And thanks a lot!

hello i want to study

Hello!! Grad coach teams. I am extremely happy in your tutorial or consultation. i am really benefited all material and briefing. Thank you very much for your generous helps. Please keep it up. If you add in your briefing, references for further reading, it will be very nice.

All I have to say is, thank u gyz.

Good, l thanks

thank you, it is very useful

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is A Literature Review (In A Dissertation Or Thesis) - Grad Coach - […] the literature review is to inform the choice of methodology for your own research. As we’ve discussed on the Grad Coach blog,…

- Free Download: Research Proposal Template (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Research design (methodology) […]

- Dissertation vs Thesis: What's the difference? - Grad Coach - […] and thesis writing on a daily basis – everything from how to find a good research topic to which…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Research methods--quantitative, qualitative, and more: overview.

- Quantitative Research

- Qualitative Research

- Data Science Methods (Machine Learning, AI, Big Data)

- Text Mining and Computational Text Analysis

- Evidence Synthesis/Systematic Reviews

- Get Data, Get Help!

About Research Methods

This guide provides an overview of research methods, how to choose and use them, and supports and resources at UC Berkeley.

As Patten and Newhart note in the book Understanding Research Methods , "Research methods are the building blocks of the scientific enterprise. They are the "how" for building systematic knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge through research is by its nature a collective endeavor. Each well-designed study provides evidence that may support, amend, refute, or deepen the understanding of existing knowledge...Decisions are important throughout the practice of research and are designed to help researchers collect evidence that includes the full spectrum of the phenomenon under study, to maintain logical rules, and to mitigate or account for possible sources of bias. In many ways, learning research methods is learning how to see and make these decisions."

The choice of methods varies by discipline, by the kind of phenomenon being studied and the data being used to study it, by the technology available, and more. This guide is an introduction, but if you don't see what you need here, always contact your subject librarian, and/or take a look to see if there's a library research guide that will answer your question.

Suggestions for changes and additions to this guide are welcome!

START HERE: SAGE Research Methods

Without question, the most comprehensive resource available from the library is SAGE Research Methods. HERE IS THE ONLINE GUIDE to this one-stop shopping collection, and some helpful links are below:

- SAGE Research Methods

- Little Green Books (Quantitative Methods)

- Little Blue Books (Qualitative Methods)

- Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

- Case studies of real research projects

- Sample datasets for hands-on practice

- Streaming video--see methods come to life

- Methodspace- -a community for researchers

- SAGE Research Methods Course Mapping

Library Data Services at UC Berkeley

Library Data Services Program and Digital Scholarship Services

The LDSP offers a variety of services and tools ! From this link, check out pages for each of the following topics: discovering data, managing data, collecting data, GIS data, text data mining, publishing data, digital scholarship, open science, and the Research Data Management Program.

Be sure also to check out the visual guide to where to seek assistance on campus with any research question you may have!

Library GIS Services

Other Data Services at Berkeley

D-Lab Supports Berkeley faculty, staff, and graduate students with research in data intensive social science, including a wide range of training and workshop offerings Dryad Dryad is a simple self-service tool for researchers to use in publishing their datasets. It provides tools for the effective publication of and access to research data. Geospatial Innovation Facility (GIF) Provides leadership and training across a broad array of integrated mapping technologies on campu Research Data Management A UC Berkeley guide and consulting service for research data management issues

General Research Methods Resources

Here are some general resources for assistance:

- Assistance from ICPSR (must create an account to access): Getting Help with Data , and Resources for Students

- Wiley Stats Ref for background information on statistics topics

- Survey Documentation and Analysis (SDA) . Program for easy web-based analysis of survey data.

Consultants

- D-Lab/Data Science Discovery Consultants Request help with your research project from peer consultants.

- Research data (RDM) consulting Meet with RDM consultants before designing the data security, storage, and sharing aspects of your qualitative project.

- Statistics Department Consulting Services A service in which advanced graduate students, under faculty supervision, are available to consult during specified hours in the Fall and Spring semesters.

Related Resourcex

- IRB / CPHS Qualitative research projects with human subjects often require that you go through an ethics review.

- OURS (Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarships) OURS supports undergraduates who want to embark on research projects and assistantships. In particular, check out their "Getting Started in Research" workshops

- Sponsored Projects Sponsored projects works with researchers applying for major external grants.

- Next: Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2023 3:14 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/researchmethods

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

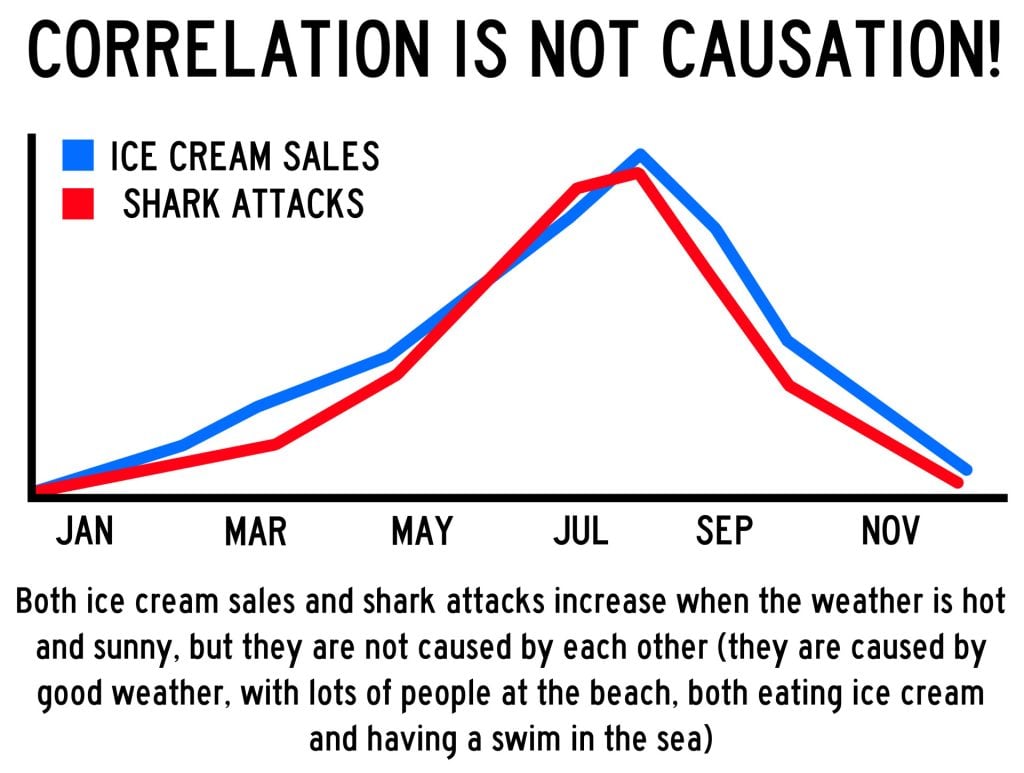

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 20 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Research Methods In Psychology

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Research methods in psychology are systematic procedures used to observe, describe, predict, and explain behavior and mental processes. They include experiments, surveys, case studies, and naturalistic observations, ensuring data collection is objective and reliable to understand and explain psychological phenomena.

Hypotheses are statements about the prediction of the results, that can be verified or disproved by some investigation.

There are four types of hypotheses :

- Null Hypotheses (H0 ) – these predict that no difference will be found in the results between the conditions. Typically these are written ‘There will be no difference…’

- Alternative Hypotheses (Ha or H1) – these predict that there will be a significant difference in the results between the two conditions. This is also known as the experimental hypothesis.

- One-tailed (directional) hypotheses – these state the specific direction the researcher expects the results to move in, e.g. higher, lower, more, less. In a correlation study, the predicted direction of the correlation can be either positive or negative.

- Two-tailed (non-directional) hypotheses – these state that a difference will be found between the conditions of the independent variable but does not state the direction of a difference or relationship. Typically these are always written ‘There will be a difference ….’

All research has an alternative hypothesis (either a one-tailed or two-tailed) and a corresponding null hypothesis.

Once the research is conducted and results are found, psychologists must accept one hypothesis and reject the other.

So, if a difference is found, the Psychologist would accept the alternative hypothesis and reject the null. The opposite applies if no difference is found.

Sampling techniques

Sampling is the process of selecting a representative group from the population under study.

A sample is the participants you select from a target population (the group you are interested in) to make generalizations about.

Representative means the extent to which a sample mirrors a researcher’s target population and reflects its characteristics.

Generalisability means the extent to which their findings can be applied to the larger population of which their sample was a part.

- Volunteer sample : where participants pick themselves through newspaper adverts, noticeboards or online.

- Opportunity sampling : also known as convenience sampling , uses people who are available at the time the study is carried out and willing to take part. It is based on convenience.

- Random sampling : when every person in the target population has an equal chance of being selected. An example of random sampling would be picking names out of a hat.

- Systematic sampling : when a system is used to select participants. Picking every Nth person from all possible participants. N = the number of people in the research population / the number of people needed for the sample.

- Stratified sampling : when you identify the subgroups and select participants in proportion to their occurrences.

- Snowball sampling : when researchers find a few participants, and then ask them to find participants themselves and so on.

- Quota sampling : when researchers will be told to ensure the sample fits certain quotas, for example they might be told to find 90 participants, with 30 of them being unemployed.

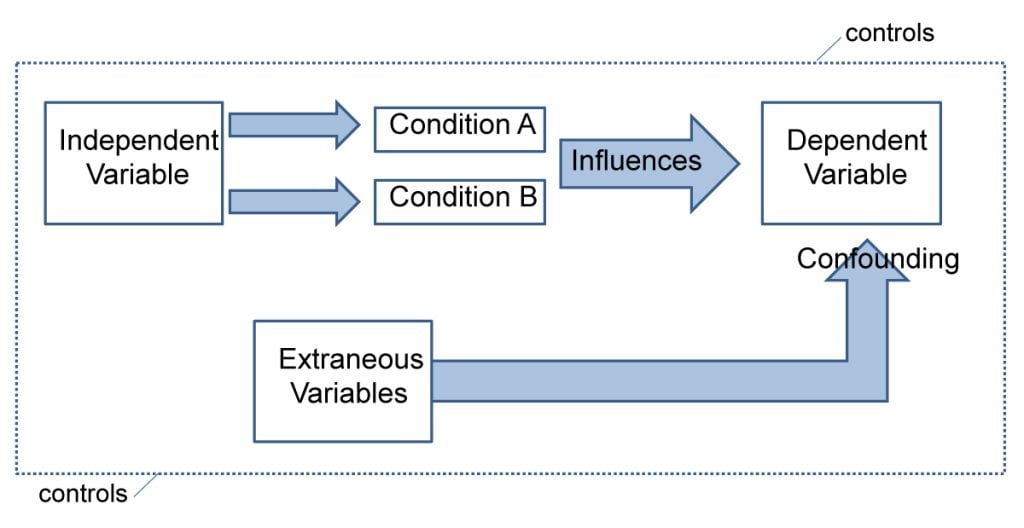

Experiments always have an independent and dependent variable .

- The independent variable is the one the experimenter manipulates (the thing that changes between the conditions the participants are placed into). It is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

- The dependent variable is the thing being measured, or the results of the experiment.

Operationalization of variables means making them measurable/quantifiable. We must use operationalization to ensure that variables are in a form that can be easily tested.

For instance, we can’t really measure ‘happiness’, but we can measure how many times a person smiles within a two-hour period.

By operationalizing variables, we make it easy for someone else to replicate our research. Remember, this is important because we can check if our findings are reliable.

Extraneous variables are all variables which are not independent variable but could affect the results of the experiment.

It can be a natural characteristic of the participant, such as intelligence levels, gender, or age for example, or it could be a situational feature of the environment such as lighting or noise.

Demand characteristics are a type of extraneous variable that occurs if the participants work out the aims of the research study, they may begin to behave in a certain way.

For example, in Milgram’s research , critics argued that participants worked out that the shocks were not real and they administered them as they thought this was what was required of them.

Extraneous variables must be controlled so that they do not affect (confound) the results.

Randomly allocating participants to their conditions or using a matched pairs experimental design can help to reduce participant variables.

Situational variables are controlled by using standardized procedures, ensuring every participant in a given condition is treated in the same way

Experimental Design

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to each condition of the independent variable, such as a control or experimental group.

- Independent design ( between-groups design ): each participant is selected for only one group. With the independent design, the most common way of deciding which participants go into which group is by means of randomization.

- Matched participants design : each participant is selected for only one group, but the participants in the two groups are matched for some relevant factor or factors (e.g. ability; sex; age).

- Repeated measures design ( within groups) : each participant appears in both groups, so that there are exactly the same participants in each group.

- The main problem with the repeated measures design is that there may well be order effects. Their experiences during the experiment may change the participants in various ways.

- They may perform better when they appear in the second group because they have gained useful information about the experiment or about the task. On the other hand, they may perform less well on the second occasion because of tiredness or boredom.

- Counterbalancing is the best way of preventing order effects from disrupting the findings of an experiment, and involves ensuring that each condition is equally likely to be used first and second by the participants.

If we wish to compare two groups with respect to a given independent variable, it is essential to make sure that the two groups do not differ in any other important way.

Experimental Methods

All experimental methods involve an iv (independent variable) and dv (dependent variable)..

- Field experiments are conducted in the everyday (natural) environment of the participants. The experimenter still manipulates the IV, but in a real-life setting. It may be possible to control extraneous variables, though such control is more difficult than in a lab experiment.

- Natural experiments are when a naturally occurring IV is investigated that isn’t deliberately manipulated, it exists anyway. Participants are not randomly allocated, and the natural event may only occur rarely.

Case studies are in-depth investigations of a person, group, event, or community. It uses information from a range of sources, such as from the person concerned and also from their family and friends.

Many techniques may be used such as interviews, psychological tests, observations and experiments. Case studies are generally longitudinal: in other words, they follow the individual or group over an extended period of time.

Case studies are widely used in psychology and among the best-known ones carried out were by Sigmund Freud . He conducted very detailed investigations into the private lives of his patients in an attempt to both understand and help them overcome their illnesses.

Case studies provide rich qualitative data and have high levels of ecological validity. However, it is difficult to generalize from individual cases as each one has unique characteristics.

Correlational Studies

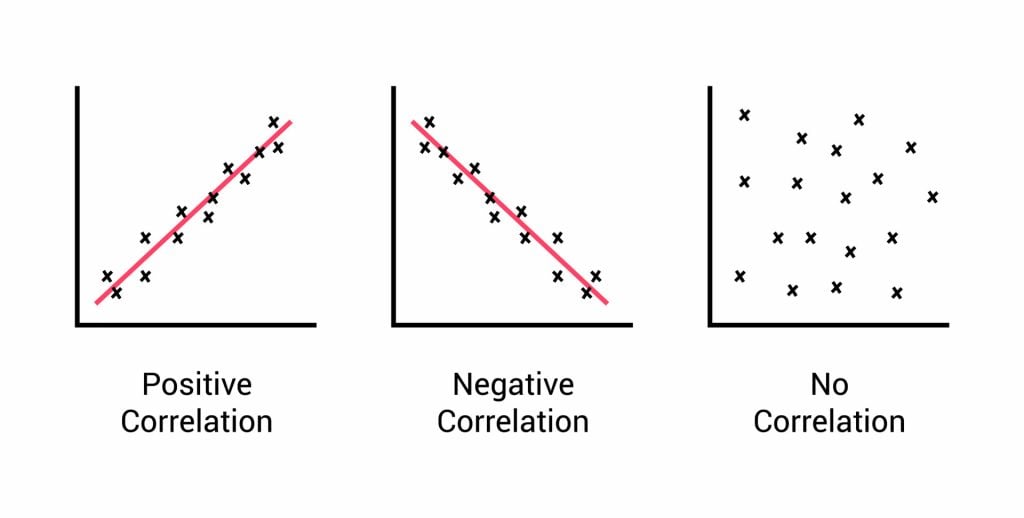

Correlation means association; it is a measure of the extent to which two variables are related. One of the variables can be regarded as the predictor variable with the other one as the outcome variable.

Correlational studies typically involve obtaining two different measures from a group of participants, and then assessing the degree of association between the measures.

The predictor variable can be seen as occurring before the outcome variable in some sense. It is called the predictor variable, because it forms the basis for predicting the value of the outcome variable.

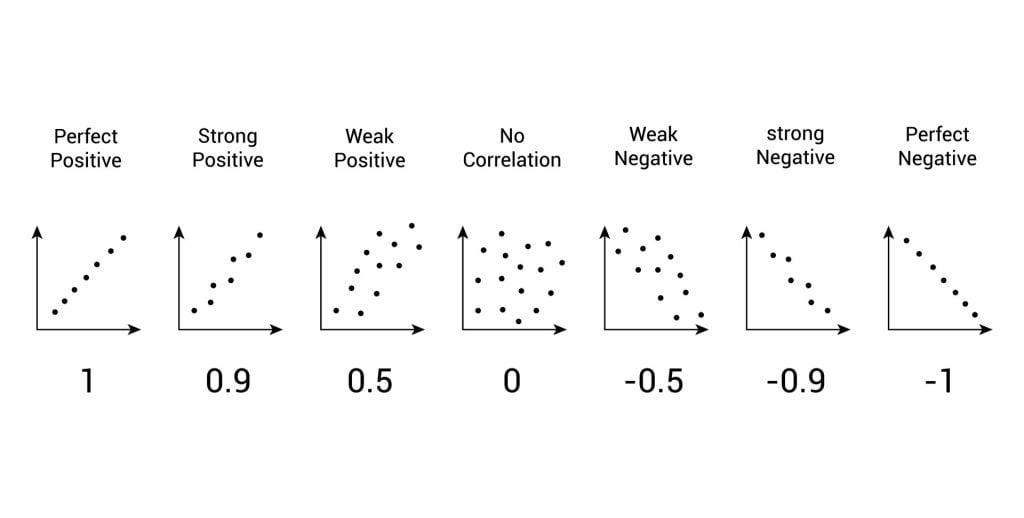

Relationships between variables can be displayed on a graph or as a numerical score called a correlation coefficient.

- If an increase in one variable tends to be associated with an increase in the other, then this is known as a positive correlation .

- If an increase in one variable tends to be associated with a decrease in the other, then this is known as a negative correlation .

- A zero correlation occurs when there is no relationship between variables.

After looking at the scattergraph, if we want to be sure that a significant relationship does exist between the two variables, a statistical test of correlation can be conducted, such as Spearman’s rho.

The test will give us a score, called a correlation coefficient . This is a value between 0 and 1, and the closer to 1 the score is, the stronger the relationship between the variables. This value can be both positive e.g. 0.63, or negative -0.63.

A correlation between variables, however, does not automatically mean that the change in one variable is the cause of the change in the values of the other variable. A correlation only shows if there is a relationship between variables.

Correlation does not always prove causation, as a third variable may be involved.

Interview Methods

Interviews are commonly divided into two types: structured and unstructured.

A fixed, predetermined set of questions is put to every participant in the same order and in the same way.

Responses are recorded on a questionnaire, and the researcher presets the order and wording of questions, and sometimes the range of alternative answers.

The interviewer stays within their role and maintains social distance from the interviewee.

There are no set questions, and the participant can raise whatever topics he/she feels are relevant and ask them in their own way. Questions are posed about participants’ answers to the subject

Unstructured interviews are most useful in qualitative research to analyze attitudes and values.

Though they rarely provide a valid basis for generalization, their main advantage is that they enable the researcher to probe social actors’ subjective point of view.

Questionnaire Method

Questionnaires can be thought of as a kind of written interview. They can be carried out face to face, by telephone, or post.

The choice of questions is important because of the need to avoid bias or ambiguity in the questions, ‘leading’ the respondent or causing offense.

- Open questions are designed to encourage a full, meaningful answer using the subject’s own knowledge and feelings. They provide insights into feelings, opinions, and understanding. Example: “How do you feel about that situation?”

- Closed questions can be answered with a simple “yes” or “no” or specific information, limiting the depth of response. They are useful for gathering specific facts or confirming details. Example: “Do you feel anxious in crowds?”

Its other practical advantages are that it is cheaper than face-to-face interviews and can be used to contact many respondents scattered over a wide area relatively quickly.

Observations

There are different types of observation methods :

- Covert observation is where the researcher doesn’t tell the participants they are being observed until after the study is complete. There could be ethical problems or deception and consent with this particular observation method.

- Overt observation is where a researcher tells the participants they are being observed and what they are being observed for.

- Controlled : behavior is observed under controlled laboratory conditions (e.g., Bandura’s Bobo doll study).

- Natural : Here, spontaneous behavior is recorded in a natural setting.

- Participant : Here, the observer has direct contact with the group of people they are observing. The researcher becomes a member of the group they are researching.

- Non-participant (aka “fly on the wall): The researcher does not have direct contact with the people being observed. The observation of participants’ behavior is from a distance

Pilot Study

A pilot study is a small scale preliminary study conducted in order to evaluate the feasibility of the key s teps in a future, full-scale project.

A pilot study is an initial run-through of the procedures to be used in an investigation; it involves selecting a few people and trying out the study on them. It is possible to save time, and in some cases, money, by identifying any flaws in the procedures designed by the researcher.

A pilot study can help the researcher spot any ambiguities (i.e. unusual things) or confusion in the information given to participants or problems with the task devised.

Sometimes the task is too hard, and the researcher may get a floor effect, because none of the participants can score at all or can complete the task – all performances are low.

The opposite effect is a ceiling effect, when the task is so easy that all achieve virtually full marks or top performances and are “hitting the ceiling”.

Research Design

In cross-sectional research , a researcher compares multiple segments of the population at the same time

Sometimes, we want to see how people change over time, as in studies of human development and lifespan. Longitudinal research is a research design in which data-gathering is administered repeatedly over an extended period of time.

In cohort studies , the participants must share a common factor or characteristic such as age, demographic, or occupation. A cohort study is a type of longitudinal study in which researchers monitor and observe a chosen population over an extended period.

Triangulation means using more than one research method to improve the study’s validity.

Reliability

Reliability is a measure of consistency, if a particular measurement is repeated and the same result is obtained then it is described as being reliable.

- Test-retest reliability : assessing the same person on two different occasions which shows the extent to which the test produces the same answers.

- Inter-observer reliability : the extent to which there is an agreement between two or more observers.

Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis is a systematic review that involves identifying an aim and then searching for research studies that have addressed similar aims/hypotheses.

This is done by looking through various databases, and then decisions are made about what studies are to be included/excluded.

Strengths: Increases the conclusions’ validity as they’re based on a wider range.

Weaknesses: Research designs in studies can vary, so they are not truly comparable.

Peer Review

A researcher submits an article to a journal. The choice of the journal may be determined by the journal’s audience or prestige.

The journal selects two or more appropriate experts (psychologists working in a similar field) to peer review the article without payment. The peer reviewers assess: the methods and designs used, originality of the findings, the validity of the original research findings and its content, structure and language.

Feedback from the reviewer determines whether the article is accepted. The article may be: Accepted as it is, accepted with revisions, sent back to the author to revise and re-submit or rejected without the possibility of submission.

The editor makes the final decision whether to accept or reject the research report based on the reviewers comments/ recommendations.

Peer review is important because it prevent faulty data from entering the public domain, it provides a way of checking the validity of findings and the quality of the methodology and is used to assess the research rating of university departments.

Peer reviews may be an ideal, whereas in practice there are lots of problems. For example, it slows publication down and may prevent unusual, new work being published. Some reviewers might use it as an opportunity to prevent competing researchers from publishing work.

Some people doubt whether peer review can really prevent the publication of fraudulent research.

The advent of the internet means that a lot of research and academic comment is being published without official peer reviews than before, though systems are evolving on the internet where everyone really has a chance to offer their opinions and police the quality of research.

Types of Data

- Quantitative data is numerical data e.g. reaction time or number of mistakes. It represents how much or how long, how many there are of something. A tally of behavioral categories and closed questions in a questionnaire collect quantitative data.

- Qualitative data is virtually any type of information that can be observed and recorded that is not numerical in nature and can be in the form of written or verbal communication. Open questions in questionnaires and accounts from observational studies collect qualitative data.

- Primary data is first-hand data collected for the purpose of the investigation.

- Secondary data is information that has been collected by someone other than the person who is conducting the research e.g. taken from journals, books or articles.

Validity means how well a piece of research actually measures what it sets out to, or how well it reflects the reality it claims to represent.

Validity is whether the observed effect is genuine and represents what is actually out there in the world.

- Concurrent validity is the extent to which a psychological measure relates to an existing similar measure and obtains close results. For example, a new intelligence test compared to an established test.

- Face validity : does the test measure what it’s supposed to measure ‘on the face of it’. This is done by ‘eyeballing’ the measuring or by passing it to an expert to check.

- Ecological validit y is the extent to which findings from a research study can be generalized to other settings / real life.

- Temporal validity is the extent to which findings from a research study can be generalized to other historical times.

Features of Science

- Paradigm – A set of shared assumptions and agreed methods within a scientific discipline.

- Paradigm shift – The result of the scientific revolution: a significant change in the dominant unifying theory within a scientific discipline.

- Objectivity – When all sources of personal bias are minimised so not to distort or influence the research process.

- Empirical method – Scientific approaches that are based on the gathering of evidence through direct observation and experience.

- Replicability – The extent to which scientific procedures and findings can be repeated by other researchers.

- Falsifiability – The principle that a theory cannot be considered scientific unless it admits the possibility of being proved untrue.

Statistical Testing

A significant result is one where there is a low probability that chance factors were responsible for any observed difference, correlation, or association in the variables tested.

If our test is significant, we can reject our null hypothesis and accept our alternative hypothesis.

If our test is not significant, we can accept our null hypothesis and reject our alternative hypothesis. A null hypothesis is a statement of no effect.

In Psychology, we use p < 0.05 (as it strikes a balance between making a type I and II error) but p < 0.01 is used in tests that could cause harm like introducing a new drug.

A type I error is when the null hypothesis is rejected when it should have been accepted (happens when a lenient significance level is used, an error of optimism).

A type II error is when the null hypothesis is accepted when it should have been rejected (happens when a stringent significance level is used, an error of pessimism).

Ethical Issues

- Informed consent is when participants are able to make an informed judgment about whether to take part. It causes them to guess the aims of the study and change their behavior.

- To deal with it, we can gain presumptive consent or ask them to formally indicate their agreement to participate but it may invalidate the purpose of the study and it is not guaranteed that the participants would understand.

- Deception should only be used when it is approved by an ethics committee, as it involves deliberately misleading or withholding information. Participants should be fully debriefed after the study but debriefing can’t turn the clock back.

- All participants should be informed at the beginning that they have the right to withdraw if they ever feel distressed or uncomfortable.

- It causes bias as the ones that stayed are obedient and some may not withdraw as they may have been given incentives or feel like they’re spoiling the study. Researchers can offer the right to withdraw data after participation.

- Participants should all have protection from harm . The researcher should avoid risks greater than those experienced in everyday life and they should stop the study if any harm is suspected. However, the harm may not be apparent at the time of the study.

- Confidentiality concerns the communication of personal information. The researchers should not record any names but use numbers or false names though it may not be possible as it is sometimes possible to work out who the researchers were.

What is Research Methodology? Definition, Types, and Examples

Research methodology 1,2 is a structured and scientific approach used to collect, analyze, and interpret quantitative or qualitative data to answer research questions or test hypotheses. A research methodology is like a plan for carrying out research and helps keep researchers on track by limiting the scope of the research. Several aspects must be considered before selecting an appropriate research methodology, such as research limitations and ethical concerns that may affect your research.

The research methodology section in a scientific paper describes the different methodological choices made, such as the data collection and analysis methods, and why these choices were selected. The reasons should explain why the methods chosen are the most appropriate to answer the research question. A good research methodology also helps ensure the reliability and validity of the research findings. There are three types of research methodology—quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method, which can be chosen based on the research objectives.

What is research methodology ?

A research methodology describes the techniques and procedures used to identify and analyze information regarding a specific research topic. It is a process by which researchers design their study so that they can achieve their objectives using the selected research instruments. It includes all the important aspects of research, including research design, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and the overall framework within which the research is conducted. While these points can help you understand what is research methodology, you also need to know why it is important to pick the right methodology.

Why is research methodology important?

Having a good research methodology in place has the following advantages: 3

- Helps other researchers who may want to replicate your research; the explanations will be of benefit to them.

- You can easily answer any questions about your research if they arise at a later stage.

- A research methodology provides a framework and guidelines for researchers to clearly define research questions, hypotheses, and objectives.

- It helps researchers identify the most appropriate research design, sampling technique, and data collection and analysis methods.

- A sound research methodology helps researchers ensure that their findings are valid and reliable and free from biases and errors.

- It also helps ensure that ethical guidelines are followed while conducting research.

- A good research methodology helps researchers in planning their research efficiently, by ensuring optimum usage of their time and resources.

Writing the methods section of a research paper? Let Paperpal help you achieve perfection

Types of research methodology.

There are three types of research methodology based on the type of research and the data required. 1

- Quantitative research methodology focuses on measuring and testing numerical data. This approach is good for reaching a large number of people in a short amount of time. This type of research helps in testing the causal relationships between variables, making predictions, and generalizing results to wider populations.

- Qualitative research methodology examines the opinions, behaviors, and experiences of people. It collects and analyzes words and textual data. This research methodology requires fewer participants but is still more time consuming because the time spent per participant is quite large. This method is used in exploratory research where the research problem being investigated is not clearly defined.

- Mixed-method research methodology uses the characteristics of both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies in the same study. This method allows researchers to validate their findings, verify if the results observed using both methods are complementary, and explain any unexpected results obtained from one method by using the other method.

What are the types of sampling designs in research methodology?

Sampling 4 is an important part of a research methodology and involves selecting a representative sample of the population to conduct the study, making statistical inferences about them, and estimating the characteristics of the whole population based on these inferences. There are two types of sampling designs in research methodology—probability and nonprobability.

- Probability sampling

In this type of sampling design, a sample is chosen from a larger population using some form of random selection, that is, every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. The different types of probability sampling are:

- Systematic —sample members are chosen at regular intervals. It requires selecting a starting point for the sample and sample size determination that can be repeated at regular intervals. This type of sampling method has a predefined range; hence, it is the least time consuming.

- Stratified —researchers divide the population into smaller groups that don’t overlap but represent the entire population. While sampling, these groups can be organized, and then a sample can be drawn from each group separately.

- Cluster —the population is divided into clusters based on demographic parameters like age, sex, location, etc.

- Convenience —selects participants who are most easily accessible to researchers due to geographical proximity, availability at a particular time, etc.

- Purposive —participants are selected at the researcher’s discretion. Researchers consider the purpose of the study and the understanding of the target audience.

- Snowball —already selected participants use their social networks to refer the researcher to other potential participants.