How to Write an Essay about a Novel – Step by Step Guide

Writing about literature used to scare the heck out of me. I really couldn’t wrap my mind around analyzing a novel. You have the story. You have the characters. But so what? I had no idea what to write.

Luckily, a brilliant professor I had as an undergrad taught me how to analyze a novel in an essay. I taught this process in the university and as a tutor for many years. It’s simple, and it works. And in this tutorial, I’ll show it to you. So, let’s go!

Writing an essay about a novel or any work of fiction is a 6-step process. Steps 1-3 are the analysis part. Steps 4-6 are the writing part.

Step 1. create a list of elements of the novel .

Ask yourself, “What are the elements of this book?”

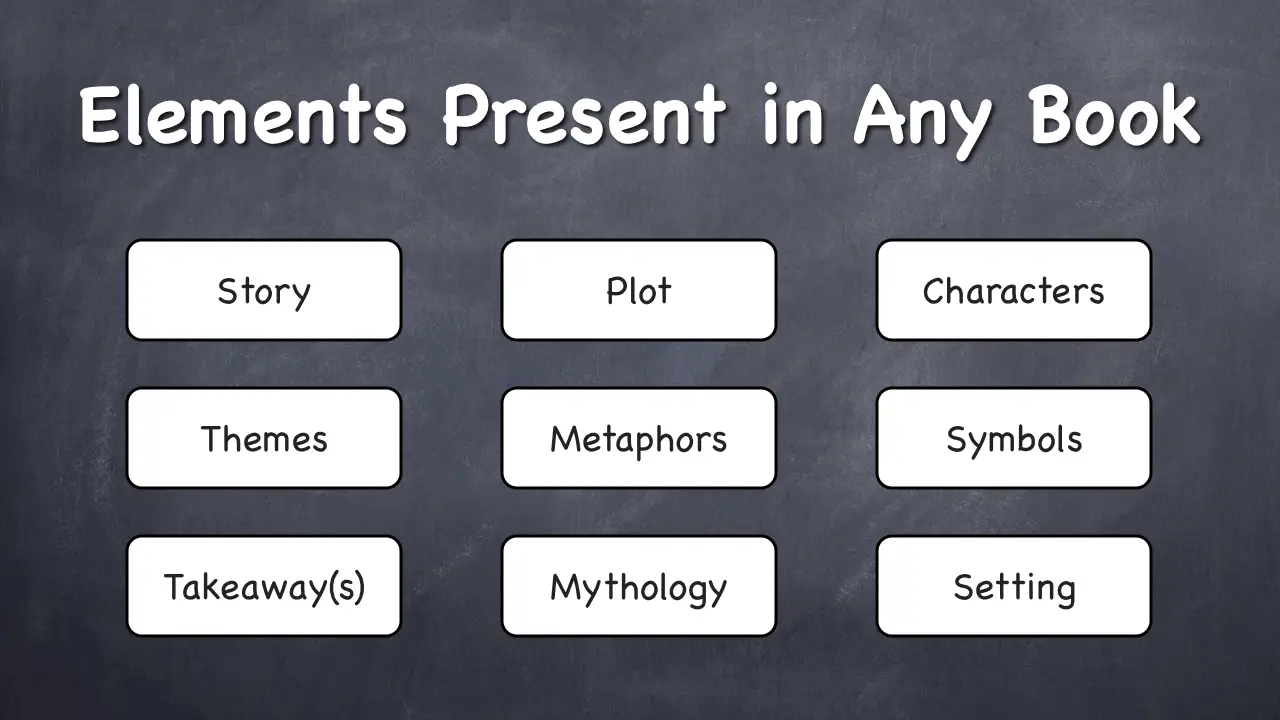

Well, here is a list of elements present in any work of fiction, any novel:

Here is a table of literary elements along with their descriptions.

| The entire dramatic account of events, from beginning to end | |

| The way dramatic events are arranged in the story | |

| A list of main and secondary characters | |

| Ideas the novel is about, such as , , , etc. | |

| Literary devices in which the author uses a familiar word or phrase to apply to another concept to which it is not literally applicable. E.g. “ .” | |

| Literary devices in which the author likens something to something else to illustrate a point. E.g. | |

| Images used to represent an idea. E.g. | |

| Lessons you’ve learned from the book | |

| Mythological elements in the story, such as , , and | |

| Where, when, and under what circumstances the action takes place. E.g. “War and Peace takes place in 19th century Russia and centers around the Russian-French war of 1812.” |

In this step, you simply pick 3-6 elements from the list I just gave you and arrange them as bullet points. You just want to make sure you pick elements that you are most familiar or comfortable with.

For example, you can create the following list:

This is just for you to capture the possibilities of what you can write about. It’s a very simple and quick step because I already gave you a list of elements.

Step 2. Pick 3 elements you are most comfortable with

In this step, we’ll use what I call The Power of Three . You don’t need more than three elements to write an excellent essay about a novel or a book.

Just pick three from the list you just created with which you are most familiar or that you understand the best. These will correspond to three sections in your essay.

If you’re an English major, you’ll be a lot more familiar with the term “metaphor” than if you major in Accounting.

But even if you’re a Math major, you are at least probably already familiar with what a story or a character is. And you’ve probably had a takeaway or a lesson from stories you’ve read or seen on screen.

Just pick what you can relate to most readily and easily.

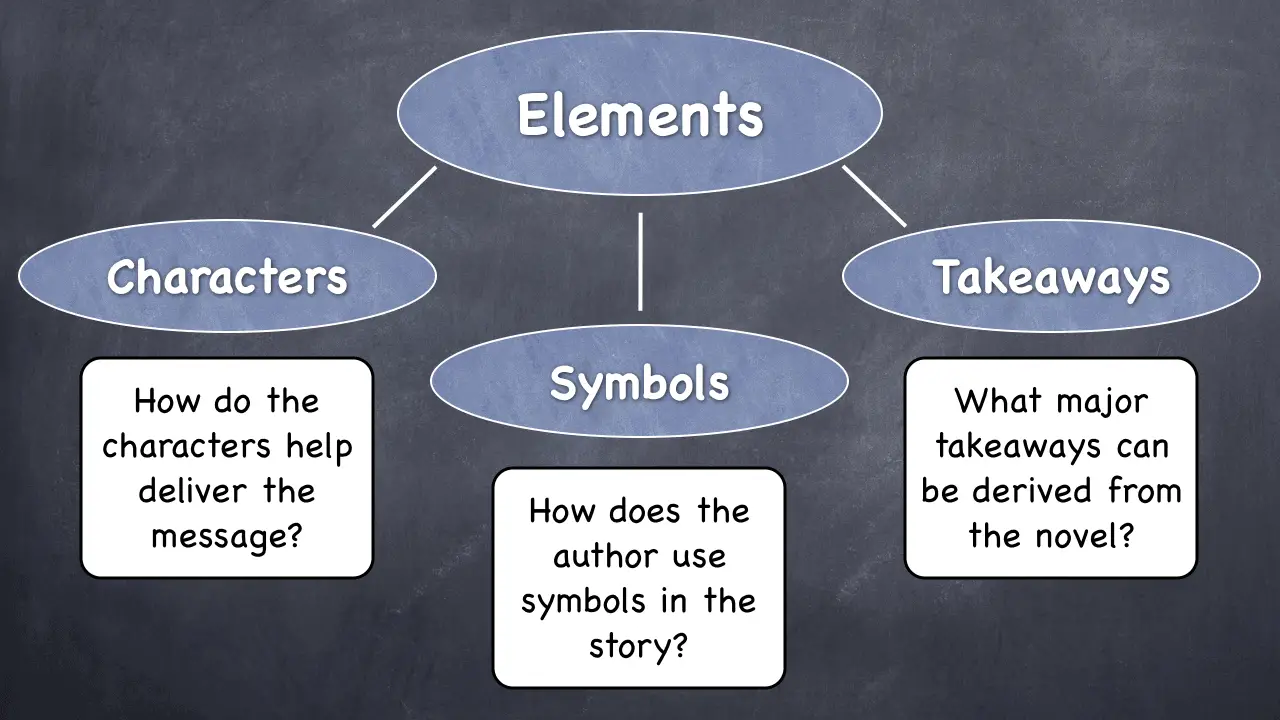

For example, you can pick Characters , Symbols , and Takeaways . Great!

You Can Also Pick Examples of an Element

Let’s say that you are really unfamiliar with most of the elements. In that case, you can just pick one and then list three examples of it.

For example, you can pick the element of Characters . And now all you need to do is choose three of the most memorable characters. You can do this with many of the elements of a novel.

You can pick three themes , such as Romance, Envy, and Adultery.

You can pick three symbols , such as a rose, a ring, and a boat. These can represent love, marriage, and departure.

Okay, great job picking your elements or examples of them.

For the rest of this tutorial, I chose to write about a novel by Fedor Dostoyevskiy, The Brothers Karamazov. This will be our example.

It is one of the greatest novels ever written. And it’s a mystery novel, too, which makes it fun.

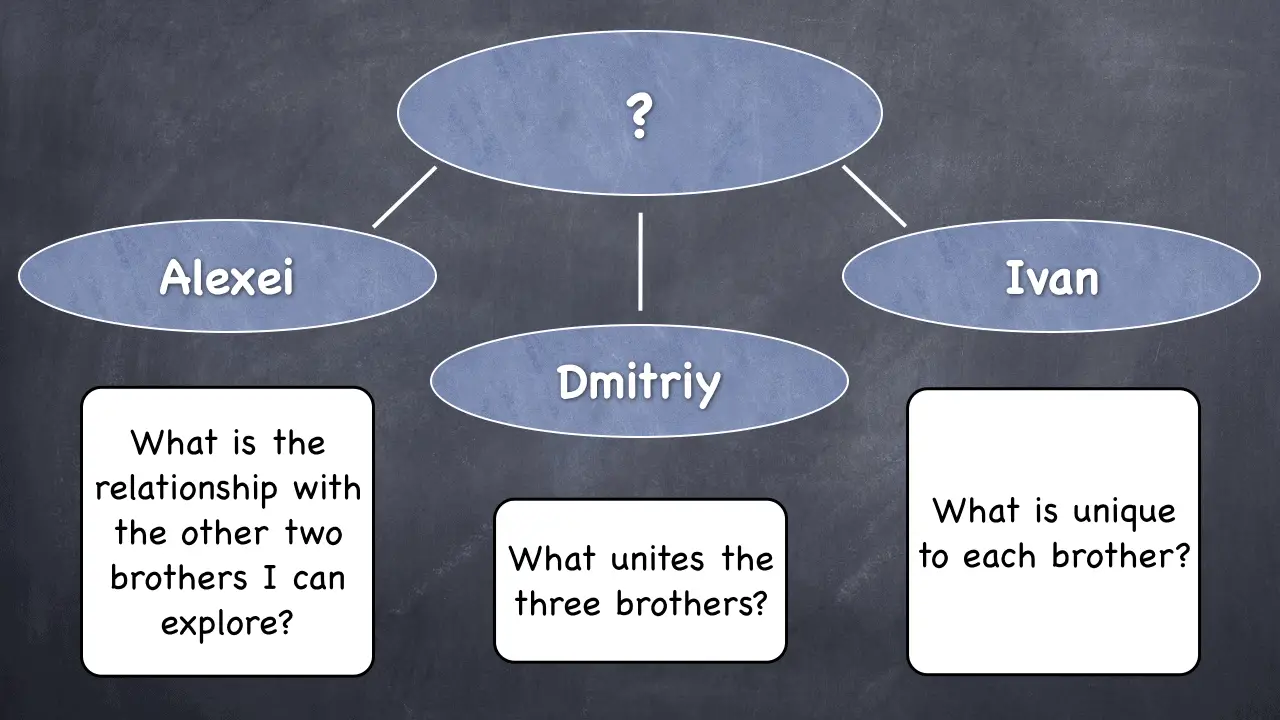

So now, let’s choose either three elements of this novel or three examples of an element. I find that one of the easiest ways to do this is to pick one element – Characters – and three examples of it.

In other words, I’m picking three characters. And the entire essay will be about these three characters.

Now, you may ask, if I write only about the characters, am I really writing an essay about the novel?

And the answer is, Yes. Because you can’t write about everything at once. You must pick something. Pick your battles.

And by doing that, you will have plenty of opportunities to make a statement about the whole novel. Does that make sense?

Just trust the process, and it will all become clear in the next steps.

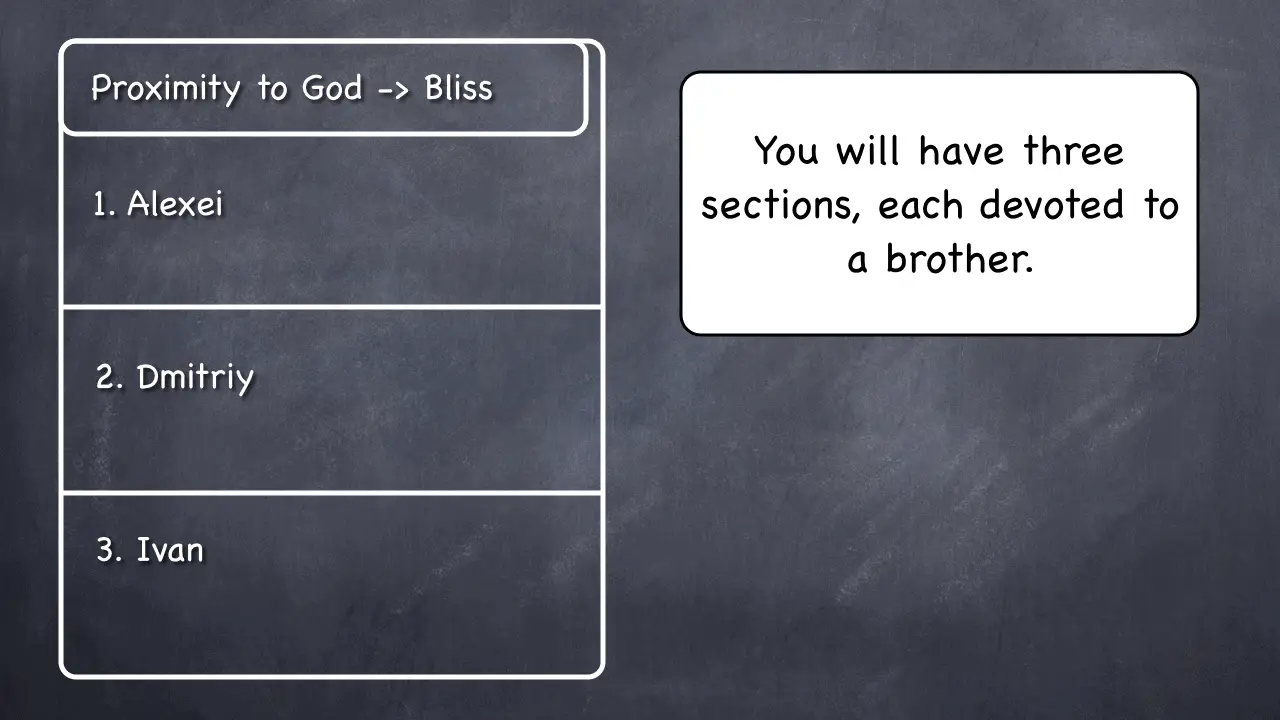

Let’s pick the three brothers – Alexei, Dmitriy, and Ivan.

And don’t worry – I won’t assume that you have read the book. And I won’t spoil it for you if you’re planning to.

So we have the three brothers. We’re ready to move on to the next step.

Step 3. Identify a relationship among these elements

In this step, you want to think about how these three elements that you picked are related to one another.

In this particular case, the three brothers are obviously related because they are brothers. But I want you to dig deeper and see if there is perhaps a theme in the novel that may be connecting the elements.

And, yes, I am using another element – theme – just to help me think about the book. Be creative and use whatever is available to you. It just so happens that religion is a very strong theme in this novel.

What do the three brothers have in common?

- They have the same father.

- Each one has a romantic interest (meaning, a beloved woman).

- All three have some kind of a relationship with God.

These are three ways in which the brothers are related to one another. All we need is one type of a relationship among them to write this essay.

This is a religious novel, and yes, some of the characters will be linked to a form of a divinity. In this case, the religion is Christianity.

Note: there are many ways in which you can play with elements of a novel and examples of them. Here’s a detailed video I made about this process:

Let’s see if we can pick the best relationship of those we just enumerated.

They all have the same father.

This relationship is only factual. It is not very interesting in any way. So we move on to the next one.

They all have women they love.

Each brother has a romantic interest, to use a literary term. We can examine each of the brothers as a lover.

Who is the most fervent lover? Who is perhaps more distant and closed? This is an interesting connecting relationship to explore.

One of them is the most passionate about his woman, but so is another one – I won’t say who so I don’t spoil the novel for you. The third brother seems rather intellectual about his love interest.

So, romantic interest is a good candidate for a connecting relationship. Let’s explore the next connection candidate.

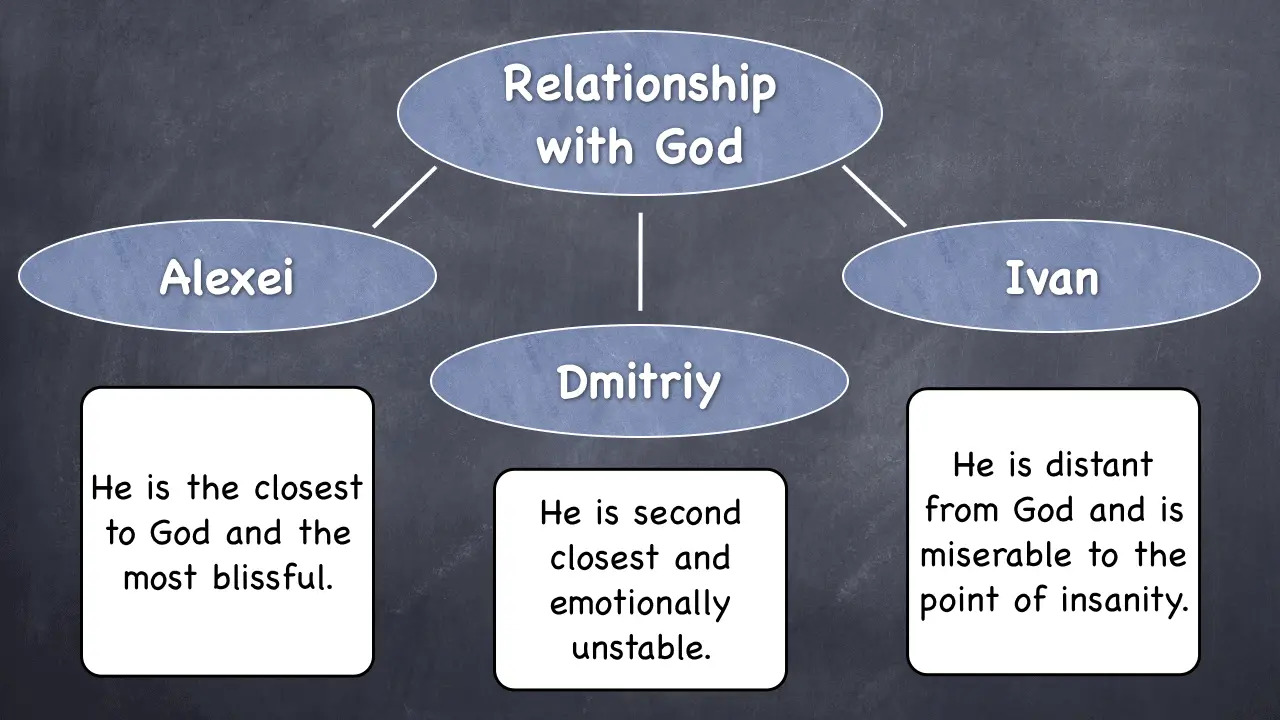

They all relate to God in one way or another.

Let’s see if we can put the brothers’ relationships with God in some sort of an order. Well, Alexei is a monk in learning. He lives at the monastery and studies Christianity. He is the closest to God.

Dmitriy is a believer, but he is more distant from God due to his passionate affair with his woman. He loses his head many times and does things that are ungodly, according to the author. So, although he is a believer, he is more distant from God than is Alexei.

Finally, Ivan is a self-proclaimed atheist. Therefore, he is the farthest away from God.

It looks like we got ourselves a nice sequence, or progression, which we can probably use to write this essay about this novel.

What is the sequence? The sequence is:

Alexei is the closest to God, Dmitriy is second closest, and Ivan is pretty far away.

It looks like we have a pattern here.

If we look at the brothers in the book and watch their emotions closely, we’ll come to the conclusion that they go from blissful to very emotionally unstable to downright miserable to the point of insanity.

Here’s the conclusion we must make:

The closer the character’s relationship with God, the happier he is, and the farther away he is from God, the more miserable he appears to be.

Wow. This is quite a conclusion. It looks like we have just uncovered one of Dostoyevskiy’s main arguments in this novel, if not the main point he is trying to make.

Now that we’ve identified our three elements (examples) and a strong connecting relationship among them, we can move on to Step 4.

Step 4. Take a stand and write your thesis statement

Now we’re ready to formulate our thesis statement. It consists of two parts:

- Your Thesis (your main argument)

- Your Outline of Support (how you plan to support your main point)

By now, we have everything we need to write a very clear and strong thesis statement.

First, let’s state our thesis as clearly and succinctly as possible, based on what we already know:

“In his novel Brothers Karamazov , Dostoyevskiy describes a world in which happiness is directly proportional to proximity to God. The closer to God a character is, the happier and more emotionally stable he is, and vice versa.”

See how clear this is? And most importantly, this is clear not only to the reader, but also to you as the writer. Now you know exactly what statement you will be supporting in the body of the essay.

Are we finished with the thesis statement? Not yet. The second part consists of your supporting points. And again, we have everything we need to write it. Let’s do it.

“Alexei’s state of mind is ultimately blissful, because he is a true and observant believer. Dmitriy’s faith is upstaged by his passion for a woman, and he suffers a lot as a result. Ivan’s renunciation of God makes him the unhappiest of the brothers and eventually leads him to insanity.”

Guess what – we have just written our complete thesis statement. And it’s also our whole first paragraph.

We are ready for Step 5.

Step 5. Write the body of the essay

Again, just like in the previous step, you have everything you need to structure and write out the body of this essay.

How many main sections will this essay have? Because we are writing about three brothers, it only makes sense that our essay will have three main sections.

Each section may have one or more paragraphs. So, here’s an important question to consider:

How many words or pages do you have to write?

Let’s say your teacher or professor wants you to write 2,000 words on this topic. Then, here is your strategic breakdown:

- Thesis Statement (first paragraph) = 100 words

- Conclusion (last paragraph) = 100 words

- Body of the Essay = 1,800 words

Let me show you how easy it is to subdivide the body of the essay into sections and subsections.

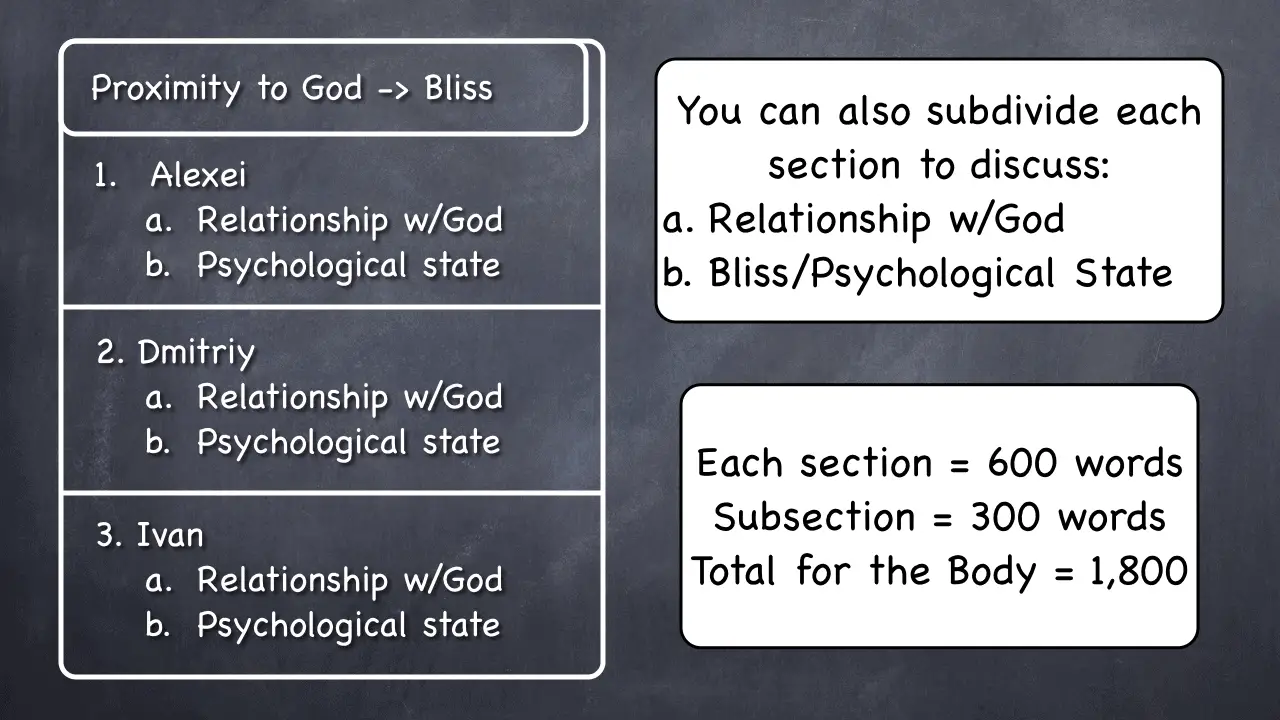

We already know that we have three sections. And we need 1,800 words total for the body. This leads us to 600 words per main section (meaning, per brother).

Can we subdivide further? Yes, we can. And we should.

When discussing each of the brothers, we connect two subjects: his relationship with God AND his psychological state. That’s how we make those connections.

So, we should simply subdivide each section of 600 words into two subsections of 300 words each. And now all we need to do is to write each part as if it were a standalone 300-word essay.

Does this make sense? See how simple and clear this is?

Writing Your Paragraphs

Writing good paragraphs is a topic for an entire article of its own. It is a science and an art.

In essence, you start your paragraph with a good lead sentence in which you make one point. Then, you provide reasons, explanations, and examples to support it.

Here is an article I wrote on how to write great paragraphs .

Once you’ve written the body of the essay, one last step remains.

Step 6. Add an introduction and a conclusion

Introductions and conclusions are those little parts of an essay that your teachers and professors will want you to write.

Introduction

In our example, we already have a full opening paragraph going. It’s our thesis statement.

To write an introduction, all you need to do is add one or two sentences above the thesis statement.

Here is our thesis statement:

“In his novel Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevskiy describes a world in which happiness is directly proportional to proximity to God. The closer to God a character is, the happier and more emotionally stable he is, and vice versa. Alexei’s state of mind is ultimately blissful, because he is a true and observant believer. Dmitriy’s faith is upstaged by his passion for a woman, and he suffers a lot as a result. Ivan’s renunciation of God makes him the unhappiest of the brothers and eventually leads him to insanity.”

As you can see, it is a complete paragraph that doesn’t lack anything. But because we need to have an introduction, here is a sentence with which we can open this paragraph:

“Dostoyevskiy is a great Russian novelist who explores the theme of religion in many of his books.”

And then just proceed with the rest of the paragraph. Read this sentence followed by the thesis statement, and you see that it works great. And it took me about 30 seconds to write this introductory sentence.

You can write conclusions in several different ways. But the most time-proven way is to simply restate your thesis.

If you write your thesis statement the way I teach, you will have a really strong opening paragraph that can be easily reworded to craft a good conclusion.

Here is an article I wrote (which includes a video) on how to write conclusions .

Congratulations!

You’ve made it to the end, and now you know exactly how to write an essay about a novel or any work of fiction!

Tutor Phil is an e-learning professional who helps adult learners finish their degrees by teaching them academic writing skills.

Recent Posts

How to Write an Essay about Why You Want to Become a Nurse

If you're eager to write an essay about why you want to become a nurse, then you've arrived at the right tutorial! An essay about why you want to enter the nursing profession can help to...

How to Write an Essay about Why You Deserve a Job

If you're preparing for a job application or interview, knowing how to express why you deserve a role is essential. This tutorial will guide you in crafting an effective essay to convey this...

How to Write an Essay About a Novel

Soheila battaglia, 25 jun 2018.

Think about the last novel you read. What about it did you love or hate? The purpose of a literature essay is to examine and evaluate a work of literature in an academic setting. To properly analyze a novel, you must break it down into its constitutive elements, including characterization, symbolism and theme. This process of analysis will help you to better understand the novel as a whole in order to write a thorough, insightful essay.

Explore this article

- Parts of the Novel

- Main Argument in the Essay

- Textual Evidence in the Essay

- Personal Interpretation Based on Evidence

1 Parts of the Novel

During and after reading a novel, the reader should ask a series of questions about aspects of the text to better understand the material. Readers might ask questions like regarding the characters' motivations. Or ask what are the main characters’ virtues and vices? Which of their actions or statements give insight into their morals? What do the characters desire? In terms of the novel's theme, the reader should ask, what is the story about? Are there any social problems conveyed through the novel? What messages does the author communicate regarding shared human experiences and perspectives on reality? If the story uses symbols, what do they represent? You may find that one or more of your responses to these questions will then become the base of your essay.

2 Main Argument in the Essay

The first step to writing an essay about a novel is to determine the main idea or argument. Millsaps College advises students, "Your essay should not just summarize the story's action or the writer's argument; your thesis should make an argument of your own." If the point you are making seems too general or too obvious, be more specific. For example, for the novel "Farenheit 451" by Ray Bradbury, the following main argument is too general: "The novel talks about the dangers of technology." A more specific and effective main argument would be, "Through its depiction of a highly controlled dystopian society, the novel conveys the dangers of using technology as an escape from human emotion and relationships." This main argument is your thesis statement.

3 Textual Evidence in the Essay

The English department at California State University, Channel Islands writes that "it's fine to make a point... but then you must provide examples that support your points." Specific evidence to support your argument includes direct references to the novel. These can be paraphrases, specific details or direct quotations. Remember that textual evidence should only be employed when it directly supports the main idea. That evidence must also be preceded or followed by analysis and an explanation of its relevance to your main point. Textual evidence must always be cited with page numbers from the novel.

4 Personal Interpretation Based on Evidence

Analysis and explanation show the reader you have closely read and reflected on the novel. Instead of summarizing or retelling the story, the focus of a literature essay should be the development of a particular point being made about the text. Your personal interpretation of the material can be conveyed through the conclusions you draw about the motivations and meanings of the novel and any real-world relationships. Those related conclusions need to be based on specific evidence from the text. Options for analyzing the text include looking it through an argument, story structure and author's intent, in a social context or from a psychological standpoint.

- 1 California State University, Channel Islands: Essay Writing Essentials

- 2 University of Nebraska-Lincoln: Some Questions to Use in Analyzing Novels

About the Author

Soheila Battaglia is a published and award-winning author and filmmaker. She holds an MA in literary cultures from New York University and a BA in ethnic studies from UC Berkeley. She is a college professor of literature and composition.

Related Articles

How to Write Comparative Essays in Literature

How to Write a Response to Literature Essay

How to Write a College Book Analysis

How to Write a Historical Narrative

How to Write a Critical Analysis of a Short Story

How to Write a Five-Paragraph Essay About a Story

How to Write Book Titles in an Essay

How to Teach Perspective to Children

Fiction Explication Vs. Analysis

Elementary Activities to Teach Themes in Literature

APA Format for Graphic Novels

What Is Expository Writing?

Guidelines for Students to Write a Memoir

How to Write a Fiction Story for 6th Graders

Rhetorical Essay Format

How to Write an Introduction for a Character Analysis

Fiction Vs. Nonfiction Writing Styles

Higher Order Thinking Skills for Reading

How to Write a Composition on the Figurative Language...

How to Teach Characterization in Literature to High...

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

How to Write an Essay About a Novel

How to Set Up a Rhetorical Analysis

Writing an engaging and stimulating essay about a novel can further develop your understanding of the text -- and earn a high grade as well. Even though there are a great number of ways to construct a well-developed essay about a novel, focus on the following prominent elements to ensure success. By analyzing these key elements in relation to a particular novel, you’ll better understand the text and be able to produce a cohesive, successful essay.

The thesis statement is the central argument of your essay. Pinpoint a particular characteristic about the novel that is open for interpretation and develop a position. It must be insightful and possess a clear counter argument. If you believe the protagonist divorced her husband because of her tragic upbringing and not her husband’s infidelity and you are confident the argument will sustain the entire essay, clearly state your position in the introductory paragraph. The thesis statement generally is the final sentence of the introductory paragraph.

Claims & Evidence

The best way to support your thesis statement is to make claims relevant to your central argument in the body of your essay. In order for your claims to have value, they must be justified with specific examples from the text. Analyze, interpret and present specific themes, character motivations, rising actions and all other elements of the novel that you believe support your central argument. The stronger your pieces of evidence are, the easier it will be to prove your claims.

Transitions

Each claim must transition smoothly into the next. Your essay is a single, cohesive piece, and the better your claims and evidence are able to build off one another the stronger and more persuasive your essay will be as a whole. Without smooth transitions from claim to claim and paragraph to paragraph, your reader will have difficulty piecing all of your positions together. This will inhibit them from seeing that your central argument has warrant and value.

Even though your conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay, it isn't simply a summation of everything you’ve already stated in the rest of the essay. The conclusion needs to elevate the essay as a whole and connect the thesis statement, claims and evidence together in a way that hasn’t yet been achieved. Offer an insight into a particular theme or character that hasn’t been addressed yet, and further convince your reader that your central argument is legitimate.

Related Articles

How to Write an Introduction to an Analytical Essay

The Parts of an Argument

How to Write a Thesis Statement for "Robinson Crusoe"

A Good Thesis Topic

How to Write an Autobiography Introduction

How to Write the Conclusion for a Persuasive Essay

How to Do an In-Depth Analysis Essay

How to Write a Grant Essay

- The University of North Carolina: The Writing Center: Literature(Fiction)

Jake Shore is an award-winning Brooklyn-based playwright, published short story writer and professor at Wagner College. His short fiction has appeared in many publications including Litro Magazine, one of London's leading literary magazines. Shore earned his MFA in creative writing from Goddard College.

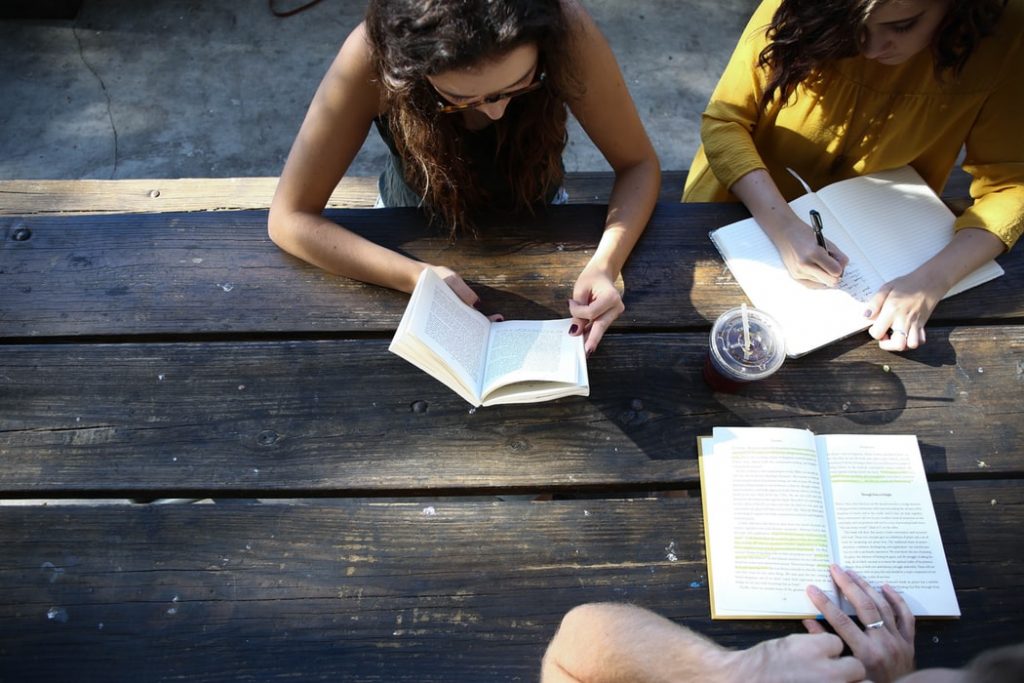

How to Write a Novel Study: A Complete Guide for Students & Teachers

What Is a Novel Study?

A novel study is essentially the process of reading and studying a novel closely. There are three formats the novel study can follow, namely:

- The whole-class format

- The small group format

- The individual format

Each of these formats comes with its own advantages and disadvantages. Which you will use in your classroom will depend on several variables, including the novel study’s purpose, class demographics, time constraints, etc.

This article will look at activities you can use with your students in a novel study. Though the focus will primarily be on the whole-class format, the activities outlined below can easily be adapted for small-group and individual novel studies.

But first, let’s take a look at some of the many considerable benefits of the novel study.

What Are the Benefits of a Novel Study?

The benefits of this type of learning are many and varied. Essentially, the novel itself serves as a jumping-off point for a diverse range of learning experiences that can benefit students’ learning in many ways.

Here are just three of these benefits.

1. Encourages a Love of Reading

As teachers, we are well aware of how much literature can enrich our lives. However, for many of our students, reading is a chore in and of itself and is to be avoided whenever possible.

The novel study sets aside time in class to focus on reading in an engaging manner that not only encourages students to enjoy reading but helps them develop the tools and strategies required to get the most out of the books they read.

2. Builds a Wider Knowledge Base

Sharing books in this manner creates opportunities for students to become exposed to experiences far beyond those of their daily lives. Not only will they enter new and unfamiliar worlds through the portal of fiction, but they’ll also be exposed to the experiences and opinions of other students in the class. These experiences and opinions may differ markedly from their own.

It will also widen the student’s knowledge and understanding of text structure, vocabulary, punctuation, and grammar . Novel studies are an extremely effective way to practice comprehension skills and improve critical thinking.

3. Boosts Class Cohesion

Whole class novel studies help your students to flex their muscles of cooperation as they work their way through a text together. They also help students to understand each other, take on board the opinions of others, and learn to defend their own thoughts and opinions.

While reading is often viewed as a solitary activity, reading in this manner can become a social experience that helps students to bond as a class.

What Should I Do in a Novel Study?

There are many different ways to undertake a novel study in your classroom.

For example, some teachers like to read the entire novel to their students first before going back through it as a class, focusing then on student interactions with the text.

Other teachers like to weave guided reading activities into their novel study sessions. However, this often works better with smaller groups where students can be grouped according to ability and assigned texts accordingly.

What shape a novel study takes in your classroom will depend on your student demographics and learning objectives. However, we can helpfully divide the various activities into pre-reading, during-reading, and post-reading. You can select those that suit your situation best.

Now, let’s look at some of these.

How to Start a Novel Study

Your novel study begins even before the first page is read. The activities below will help students tune in to the book they are about to read.

This is a crucial stage of the novel study, especially if the book is of historical significance or deals with historical events and where some background knowledge may be essential for understanding the novel.

Prereading Activities

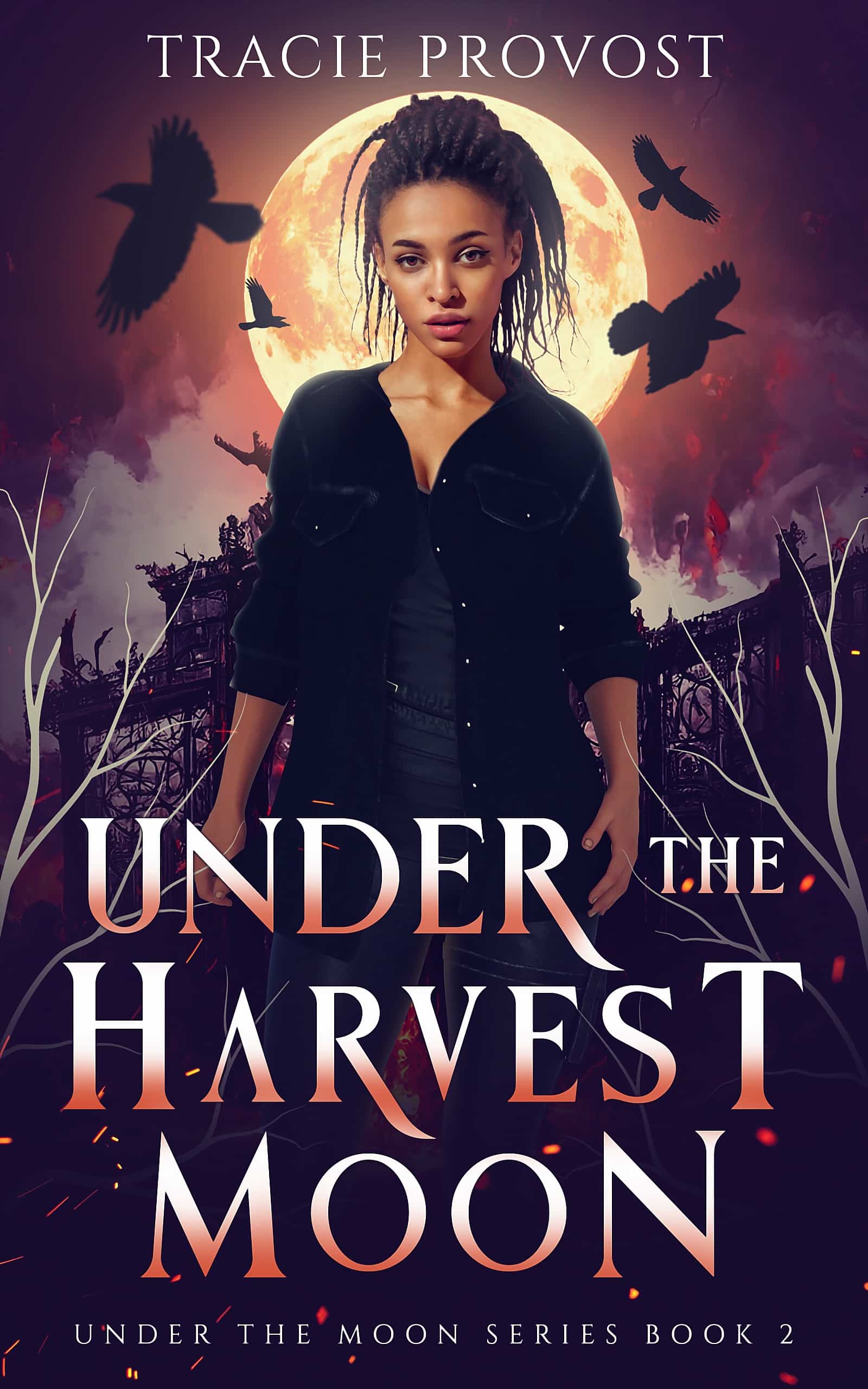

- Examine the Covers

Before opening the book, have students examine the covers closely, both front and back. What can they tell about the book before opening it based on:

- The cover illustration?

- The author’s name?

- The blurb on the back?

It’s useful to do this as a whole-class discussion to allow for sharing ideas. Ask questions to encourage reflection and get students to make predictions about the novel based on their answers and observations. For example:

- What information does the cover provide?

- Does the cover illustration intrigue you? Why?

- Does this novel remind you of any other books you’ve read? Why?

- Do you recognize the author’s name? What else have they written?

It can be pretty surprising just how much information you can glean from a novel’s covers.

- Generate a List of Questions

Once students have had a good chance to examine the novel’s covers in small groups, get them to generate questions they have about the book and its contents.

These questions may be based on their expectations in the first activity, but they may also be general questions related to common elements in all novels. For example:

- Where is the story set?

- When is it set?

- Who is the main character/protagonist in the novel?

- Who is the antagonist?

- What is the nature of the central conflict?

- What happens in the climax? Resolution? Etc.

While most of these questions will not be answered entirely until the students have read the novel, asking these questions will get the students thinking about the novel’s structure from the outset. This will be extremely useful for later activities.

- Take a Peek Inside

Now, it’s time to open the book to look closer. Task students to go ‘finger-walking’ through the book and, without reading the novel, explore the book’s pages for more surface information. For example:

- When was the book published? Why is this significant?

- Are there any illustrations inside? What impression do they make?

- Does the book have chapters? What do the chapter titles tell us about the story?

- Open a random page and read it. What language register does the writer use? What point of view is employed?

Encouraging students to work in small groups can be helpful here. You can also ask prompting questions to help students maintain focus during this activity.

During Reading Activities

The whole-class format is perhaps the most widely used in the classroom context. In this format, each student will usually have a copy of the text and follow along while the teacher or another student reads.

The reading will pause at intervals to allow the students to engage in discussion, ask questions, or complete various activities supporting learning goals related to the text they have been reading.

In general, novel study activities will focus on:

- Building vocabulary

- Improving comprehension

- Making text-to-text connections

- Making text-to-self connections

- Making text-to-world connections

In the following section, we’ll look at each of these in turn.

Reading is a fantastic way to build vocabulary; when your students encounter new vocabulary while reading, encourage them to employ several strategies to decipher the word before resorting to their dictionaries.

Firstly, what clues to the word’s meaning can the students find in the word itself? Do students recognize the word’s root or affixes? Does it resemble any other words they already know the meaning of?

Secondly, students should look at the context in which the word is used, not just in the sentence itself but also in the preceding and following paragraphs. What clues can the students find to the word’s meaning?

After analyzing the parts of the word and exhausting context clues, students can look up the word in dictionaries. However, they will still need to do some legwork to make the new word stick. Some valuable ways of committing a new word to memory include:

- Sketching a visual interpretation of the word

- Making a list of synonyms of the word using a thesaurus to assist

- Apply the target words in personal contexts (in conversation/writing sentences)

- Reading Comprehension

Vocabulary is only one aspect of comprehension. Novel studies afford students a valuable opportunity to develop their deep comprehension abilities.

Beyond just understanding the meaning of the words in a novel, students will work on their understanding of skills such as:

- Identifying the central idea/themes

- Examining character/plot development

- Distinguishing between fact and opinion

- Summarizing

- Inferencing

- Comparing and contrasting

While activities for teaching some of the more basic comprehension skills may be more self-evident, activities for teaching higher-level skills, such as inferencing, may require a bit more thought and planning.

We can define inference as the process of deriving a conclusion based on the available evidence in the text combined with the student’s background knowledge and experience.

Put simply, inference involves reading between the lines.

Inference = What is in the text + What I already know

To encourage students to use inference while completing a novel study, ask questions building on prompts such as:

- Why do you think…

- What do you think would happen if…

- What can you conclude about x based on what you’ve read?

- How does the writer feel about…

- How do you think x feels?

If you want to learn more about teaching inference in the classroom, check out our thorough article on the topic here .

- Making Connections

While vocabulary building and developing reading comprehension skills are a big part of what novel studies are all about, this type of reading lends itself to a deeper exploration of the power of the written word.

Too often, our students read prescribed texts without ever making any personal or profound connections to the material they read. Students can better understand what they are reading by exploring ways of connecting to a novel. There are three main types of connections we can explore:

- Text-to-self connections

- Text-to-text connections

- Text-to-world connections

Let’s look at how students can make each type of connection in a novel study.

Text-to-Self

This is all about the student making a personal connection and responding to the text as an individual. Essentially, this type of connection is about encouraging the students to share their thoughts and feelings on various aspects of the novel. This sharing can take the form of oral contributions to class discussions and debates or in the form of a written response.

Either way, question prompts are a great way to kick things off. Here are some examples to get the ball rolling.

- What does this incident remind you of in your own life?

- Which character do you identify with the most?

- Have you ever been in a similar situation? What happened?

- What would you do in this situation?

Text-to-Text

These connections are all about the student linking the novel they are studying to other texts they have read or seen. This could include other novels, comics, nonfiction books, websites, and poems.

Here are some useful prompts to encourage your students to make text-to-text connections.

- Have you ever read anything like this before?

- How is this text similar to/different from other texts you’ve looked at?

- What other fictional character does the hero of this novel remind you of?

Text-to-World

Making a text-to-world connection requires students to think about the novel in terms of the wider world. Here, students forge links with the broader culture and current affairs. Text-to-world connections will frequently require students to tie the novel into other areas of learning, such as social studies and the sciences.

Here are a few helpful text-to-world prompts.

- How do the events described in the novel relate to real-world events?

- What issues explored in the novel are pertinent in today’s world?

- How does the world described in the novel relate to the world we live in now?

Post-Reading Activities

The number of possible activities you can do to complete a novel is almost endless. Which activities you choose will depend on what aspect of the novel and/or objectives you are trying to teach. Here are just a few popular tasks students regularly complete after they finish reading a novel.

- Create a timeline of events.

- Graph the plot .

- Write a character profile.

- Design an alternative book cover/blurb.

- Write a summary of the novel.

- Write an alternative ending.

- Have a formal debate based on themes or issues explored in the novel.

- Write a book review.

Well, that’s enough to start a novel study in your classroom. However, if you’d like to read more on reading comprehension strategies you can employ in your novel studies, check out our depth article on the topic here .

The flexibility of the novel study format lends itself well to almost any age group; just be sure to choose a text that matches the general reading ability of your class. For older kids, you may even want to involve them in deciding what text to study.

However you decide to choose your novel, just be sure to read the text thoroughly in advance to stay one step ahead of your students – and don’t forget to have fun with it!

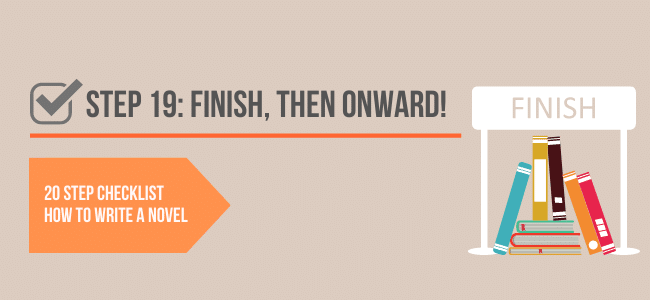

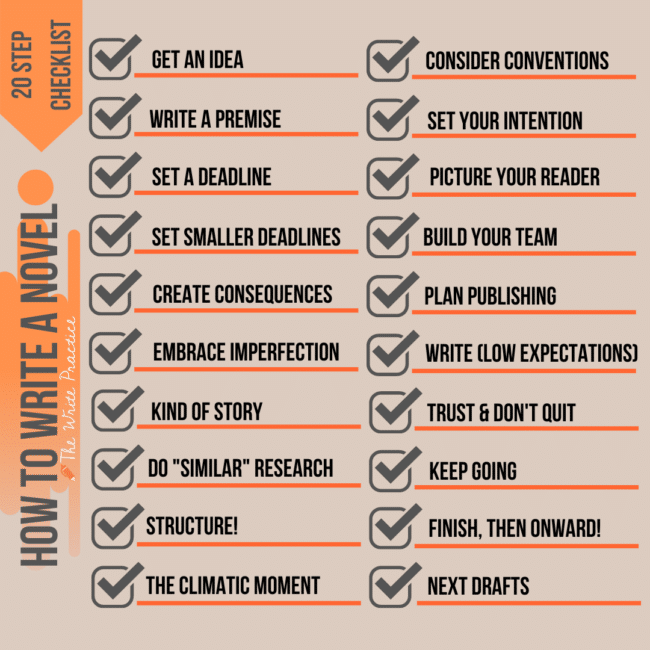

How to Write a Novel (Without Fail): The Ultimate 20-Step Guide

by Joe Bunting | 0 comments

What if you could learn how to write a novel without fail? What if you had a process so foolproof, you knew you would finish no matter what writer's block throws at you? The zombie apocalypse could finally strike and you’d still face the blank page to finish your novel.

Every day I talk to writers who don’t know how to write a novel. They worry they don’t have what it takes, and honestly, they’re right to worry.

Writing a novel, especially for the first time, is hard work, and the desk drawers and hard drives of many a great writer are filled with the skeletons of incomplete and failed books.

The good news is you don't have to be one of those failed writers.

You can be a writer that writes to the end.

You can be the kind of writer who masters how to write a novel.

Table of Contents

Looking for something specific? Jump straight to it here:

1. Get a great idea 2. Write your idea as a premise 3. Set a deadline 4. Set smaller deadlines building to the final deadline 5. Create a consequence 6. Strive for “good enough” and embrace imperfection 7. Figure out what kind of story you’re trying to tell 8. Read novels and watch films that are similar to yours 9. Structure, structure, structure! 10. Find the climactic moment in your novel 11. Consider the conventions 12. Set your intention 13. Picture your reader 14. Build your team 15. Plan the publishing process 16. Write (with low expectations) 17. Trust the process and don’t quit 118. Keep going, even when it hurts 19. Finish Draft One . . . then onward to the next 20. Draft 2, 3, 4, 5 Writers’ Best Tips on How to Write a Novel FAQ

My Journey to Learn How to Write a Novel

My name is Joe Bunting .

I used to worry I would never write a novel. Growing up, I dreamed about becoming a great novelist, writing books like the ones I loved to read. I had even tried writing novels, but I failed again and again.

So I decided to study creative writing in college. I wrote poems and short stories. I read books on writing. I earned an expensive degree.

But still, I didn’t know how to write a novel.

After college I started blogging, which led to a few gigs at a local newspaper and then a national magazine. I got a chance to ghostwrite a nonfiction book (and get paid for it!). I became a full-time, professional writer.

But even after writing a few books, I worried I didn’t have what it takes to write a novel. Novels just seemed different, harder somehow. No writing advice seemed to make it less daunting.

Maybe it was because they were so precious to me, but while writing a nonfiction book no longer intimidated me—writing a novel terrified me.

Write a novel? I didn’t know how to do it.

Until, one year later, I decided it was time. I needed to stop stalling and finally take on the process.

I crafted a plan to finish a novel using everything I’d ever learned about the book writing process. Every trick, hack, and technique I knew.

And the process worked.

I finished my novel in 100 days.

Today, I’m a Wall Street Journal bestselling author of thirteen books, and I'm passionate about teaching writers how to write and finish their books. (FINISH being the key word here.)

I’ve taught this process to hundreds of other writers who have used it to draft and complete their novels.

And today, I'm going to teach my “how to write a novel” process to you, too. In twenty manageable steps !

As I do this, I’ll share the single best novel writing tips from thirty-seven other fiction writers that you can use in your novel writing journey—

All of which is now compiled and constructed into The Write Planner : our tangible planning guide for writers that gives you this entire process in a clear, actionable, and manageable way.

If you’ve ever felt discouraged about not finishing your novel, like I did, or afraid that you don’t have what it takes to build a writing career, I’m here to tell you that you can.

There's a way to make your writing easier.

Smarter, even.

You just need to have the “write” process.

How to Write a Novel: The Foolproof, 20-Step Plan

Below, I’m going to share a foolproof process that anyone can use to write a novel, the same process I used to write my novels and books, and that hundreds of other writers have used to finish their novels too.

1. Get a Great Idea

Maybe you have a novel idea already. Maybe you have twenty ideas.

If you do, that’s awesome. Now, do this for me: Pat yourself on the back, and then forget any feeling of joy or accomplishment you have.

Here’s the thing: an idea alone, even a great idea, is just the first baby step in writing your book. There are nineteen more steps, and almost all of them are more difficult than coming up with your initial idea.

I love what George R.R. Martin said:

“Ideas are useless. Execution is everything.”

You have an idea. Now learn how to execute, starting with step two.

(And if you don’t have a novel idea yet, here’s a list of 100 story ideas that will help, or you can view our genre specific lists here: sci-fi ideas , thriller ideas , mystery ideas , romance ideas , and fantasy ideas . You can also look at the Ten Best Novel Ideas here . Check those out, then choose an idea or make up one of your own, When you're ready, come back for step two.)

2. Write Your Idea As a Premise

Now that you have a novel idea , write it out as a single-sentence premise.

What is a premise, and why do you need one?

A premise distills your novel idea down to a single sentence. This sentence will guide your entire writing and publishing process from beginning to end. It hooks the reader and captures the high stakes (and other major details) that advance and challenge the protagonist and plot.

It can also be a bit like an elevator pitch for your book. If someone asks you what your novel is about, you can share your premise to explain your story—you don't need a lengthy description.

Also, a premise is the most important part of a query letter or book proposal, so a good premise can actually help you get published.

What’s an example of a novel premise ?

Here’s an example from The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum:

A young girl is swept away to a magical land by a tornado and must embark on a quest to see the wizard who can help her return home.

Do you see the hooks? Young girl, magical land, embark on a quest (to see the wizard)—and don't forget her goal to return home.

This premise example very clearly contains the three elements every premise needs in order to stand out:

- A protagonist described in two words, e.g. a young girl or a world-weary witch.

- A goal. What the protagonist wants or needs.

- A situation or crisis the protagonist must face.

Ready to write your premise? We have a free worksheet that will guide you through writing a publishable premise: Download the worksheet here.

3. Set a Deadline

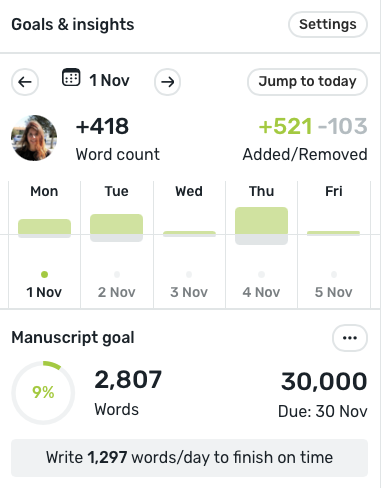

Before you do anything else, you need to set a deadline for when you’re going to finish the first draft of your novel.

Stephen King said a first draft should be written in no more than a season, so ninety days. National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo, exists to encourage people to write a book in just thirty days.

In our 100 Day Book Program, we give people a little longer than that, 100 days, which seems like a good length of time for most people (me included!).

I recommend setting your deadline no longer than four months. If it’s longer than that, you’ll procrastinate. A good length of time to write a book is something that makes you a little nervous, but not outright terrified.

Mark the deadline date in your calendar, kneel on the floor, close your eyes, and make a vow to yourself and your book idea that you will write the first draft novel by then, no matter what.

4. Set Smaller Deadlines Building to the Final Deadline

A novel can’t be written in a day. There’s no way to “cram” for a novel. The key to writing (and finishing) a novel is to make a little progress every day.

If you write a thousand words a day, something most people are capable of doing in an hour or two, for 100 days , by the end you’ll have a 100,000 word novel—which is a pretty long novel!

So set smaller, weekly deadlines that break up your book into pieces. I recommend trying to write 5,000 to 6,000 words per week by each Friday or Sunday, whichever works best for you. Your writing routine can be as flexible as you like, as long as you are hitting those smaller deadlines.

If you can hit all of your weekly deadlines, you know you’ll make your final deadline at the end.

As long as you hold yourself accountable to your smaller, feasible, and prioritized writing benchmarks.

5. Create a Consequence

You might think, “Setting a deadline is fine, but how do I actually hit my deadline?” Here’s a secret I learned from my friend Tim Grahl :

You need to create a consequence.

Try by taking these steps:

- Set your deadline.

- Write a check to an organization or nonprofit you hate (I did this during the 2016 U.S. presidential election by writing a check to the campaign of the candidate I liked least, whom shall remain nameless).

- Think of two other, minor consequences (like giving up your favorite TV show for a month or having to buy ice cream for everyone at work).

- Give your check, plus your list of two minor consequences, to a friend you trust with firm instructions to hold you to your consequences if you don’t meet your deadlines.

- If you miss one of your weekly deadlines, suffer one of your minor consequences (e.g. give up your favorite TV show).

- If you miss THREE weekly deadlines OR if you miss the final deadline, send your check to that organization you hate.

- Finally, write! I promise that if you complete steps one through six, you'll be incredibly focused.

When I took these steps while writing my seventh book, I finished it in sixty-three days. Sixty-three days!

It was the most focused I’ve ever been in my life.

Writing a book is hard work. Setting reasonable consequences make it harder to NOT finish than to finish.

Watch me walk a Wattpad famous writer through this process:

![how to write a essay on a novel Wattpad Famous Author Wanted Coaching. Here's What I Told Him [How to Write a Book Coaching]](https://thewritepractice.com/wp-content/cache/flying-press/mae2iPsg-4k-hqdefault.jpg)

6. Strive for “Good Enough” and Embrace Imperfection

The next few points are all about how to write a good story.

The reason we set a deadline before we consider how to write a story that stands out is because we could spend our entire lives learning how write a great story, but never actually write the actual story (and it’s in the writing process that you learn how to make your story great).

So learn how to make it great between writing sessions, but only good enough for the draft you’re currently writing. If you focus too much on this, it will ruin everything and you’ll never finish.

Writing a perfect novel, a novel like the one you have in your imagination, is an exercise in futility.

First drafts are inevitably horrible. Second drafts are a little better. Third drafts are better still.

But I'd bet none of these drafts approach the perfection that you built up in your head when you first considered your novel idea.

And yet, even if you know that, you’ll still try to write a perfect novel.

So remind yourself constantly, “This first draft doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to be good enough for now.”

And good enough for now, when you’re starting your first draft, just means you have words on a page that faintly resemble a story.

Writing is an iterative process. The purpose of your first draft is to have something you can improve in your second draft. Don’t overthink. Just do. (I’ll remind you of this later, in case you forget, and if you’re like me, you probably will.)

Ready to look at what makes a good story? Let’s jump into the next few points—but don’t forget your goal: to get your whole book, the complete story, on the page, no matter how messy your first draft reads.

7. Figure Out What Kind of Story You’re Trying to Tell

Now that you have a deadline, you can start to think more deeply about what your protagonist really wants.

A good story focuses primarily on just one core thing that the protagonist wants or needs, and the place where your protagonist’s want or need meets the reader’s expectations dictates your story's genre.

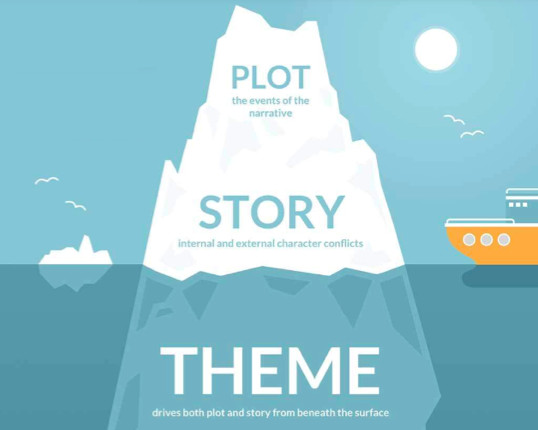

Plot type is a big subject, and for the purposes of this post, we don’t have time to fully explore it (check out my book The Write Structure here ).

But story type is about more than what shelf your book sits on at the bookstore.

The book type gets to the heart, the foundational values, of what your story is about. In my book The Write Structure , I define ten plot types, which correspond to six value scales. I’ll give an abbreviated version below:

External Values (What Your Protagonist Wants)

- Life vs. Death: Action, Adventure

- Life vs. a Fate Worse Than Death: Horror, Thriller, Mystery

- Love vs. Hate: Love, Romance

- Esteem: Performance, Sports

Internal Values (What Your Protagonist Needs)

Internal plot types work slightly different than external plot types. These are essential for your character's transformation from page one to the end and deal with either a character's shift in their black-and-white view, a character's moral compass, or a character's rise or fall in social status.

For more, check out The Write Structure .

The most common internal plot types are bulleted quickly below.

- Maturity/Sophistication vs. Immaturity/Naiveté: Coming of Age

- Good/Sacrifice vs. Evil/Selfishness: Morality, Temptation/Testing

Choosing Your External and Internal Plot Types Will Set You Up for Success

You can mix and match these genres to some extent. For your book to be commercially successful, you must have an external genre.

For your book to be considered more “character driven”—or a story that connects with the reader on a universal level—you should have an internal genre, too. (I highly recommend having both.)

You can also have a subplot. So that’s three genres that you can potentially incorporate into your novel.

For example, you might have an action plot with a love story subplot and a worldview education internal genre. Or a horror plot with a love story subplot and a morality internal genre. There’s a lot of room to maneuver.

Regardless of what you choose, the balance of the three will give your protagonist plenty of obstacles to face as they strive to achieve their goal from beginning to end. (For best results when you go to publish, though, make sure you have an external genre.)

If you want to have solid preparation to write you book, I highly recommend grabbing a copy of The Write Structure .

What two or three values are foundational to your story? Spend some time brainstorming what your book is really about. Even better, use our Write Structure worksheet to get to the heart of your story type.

8. Read Novels and Watch Films That Are Similar to Yours

“The hard truth is that books are made from books.”

I like to remember this quote from Cormac McCarthy when considering what my next novel is really about.

Now that you’ve thought about your novel's plot, it’s time to see how other great writers have pulled off the impossible and crafted a great story from the glimmer of an idea.

You might think, “My story is completely unique. There are no other stories similar to mine.”

If that’s you, then one small word of warning. If there are no books that are similar to yours, maybe there’s a reason for that.

Personally, I’ve read a lot of great books that were a lot of fun to read and were similar to other books. I’ve also read a lot of bad books that were completely unique.

Even precious, unique snowflakes look more or less like other snowflakes.

If you found your content genre in step three, select three to five novels and films that are in the same genre as yours and study them.

Don’t read/watch for pleasure. Instead, try to figure out the conventions, key scenes, and the way the author/filmmaker moves you through the story.

There's great strength in understanding how your story is the same but different.

9. STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE, STRUCTURE!

Those were the three words my college screenwriting professor, a successful Hollywood TV producer, wrote across the blackboard nearly every class. Your creative process doesn't matter without structure.

You can be a pantser , someone who writes by the seat of their pants.

You can be a plotter , someone who needs to have a detailed outline for each of the plot points in their novel.

You can even be a plantser , somewhere in between the two (like most writers, including me).

It doesn’t matter. You still have to know your story structure .

Here are a few important structural elements you’ll want to figure out for your novel before moving forward:

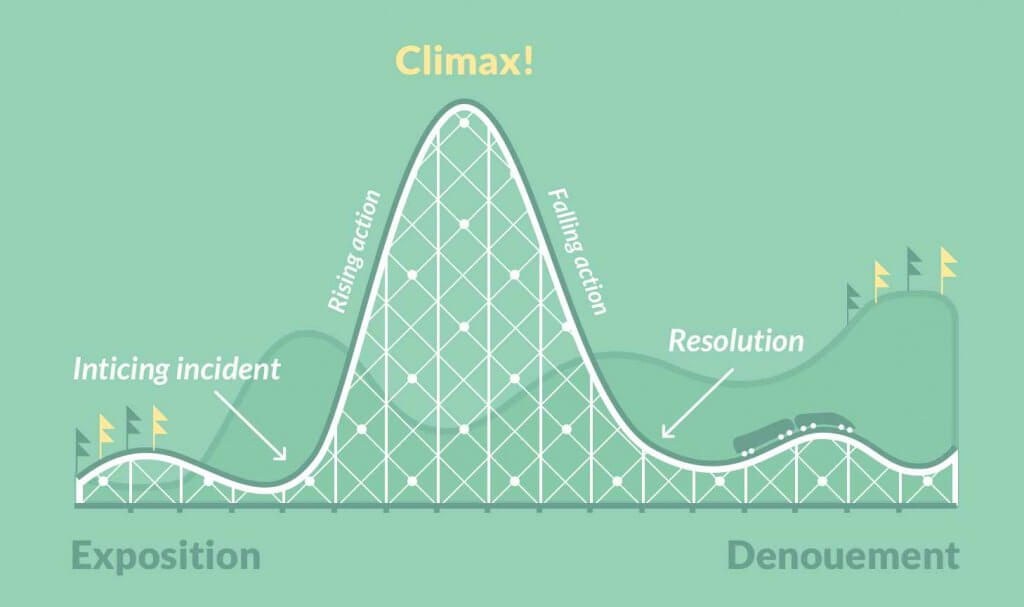

6 Key Moments of Story Structure

There are six required moments in every story, scene, and act. They are:

- Exposition : Introducing the world and the characters.

- Inciting incident : There’s a problem.

- Rising Action/Progressive complications : The problem gets worse, usually due to external conflict.

- Dilemma : The problem gets so bad that the character has no choice but to deal with it. Usually this happens off screen.

- Climax : The character makes their choice and the climax is the action that follows.

- Denouement : The problem is resolved (for now at least).

If you're unfamiliar with these terms, I recommend studying each of them, especially dilemma, which we'll talk about more in a moment. Mastering these will be a huge aid to your writing process.

For your first few scenes, try plotting out each of these six moments, focusing especially on the dilemma.

Better yet, download our story structure worksheet to guide you through the story structure process, from crafting your initial idea through to writing the synopsis.

I've included some more detailed thoughts (and must-knows) about structure briefly below:

Three Act Structure

The classic writing advice describes the three act structure well:

In the first act, put your character up a tree. In the second act, throw rocks at them. In the third act, bring them down.

Do you wonder whether you should use three act structure or five act structure? (Hint: you probably don't want to use the five act structure. Learn more about this type with our full guide on the five act structure here .)

Note that each of these acts should have the six key moments listed above.

The Dilemma

I mentioned the importance of a character undergoing a crisis, but it bears repeating since, for me, it completely transformed my writing process.

In every act, your protagonist must face an impossible choice. It is THIS choice that creates drama in your story. THIS is how your plot moves forward. If you don’t have a dilemma, if your character doesn’t choose, your scenes won’t work, nor will your acts or story.

In my writing, when I’m working on a first draft, I don’t focus on figuring out all five key moments every time (since I’ve internalized them by now), but I do try to figure out the crisis before I start writing .

I begin with that end in mind, and figure out how I can put the protagonist into a situation where they must make a difficult choice.

One that will have consequences even if they decide to do nothing.

When you do that, your scene works. When you don’t, it falls flat. The protagonist looks like a weak-willed observer of their own life, and ultimately your story will feel boring. Effective character development requires difficult choices.

Find the dilemma every time.

Write out a brief three-act outline with each of the six key moments for each act. It’s okay to leave those moments blank if you don’t know them right now. Fill in what you do know, and come back to it.

Point of View

Point of view, or POV, in a story refers to the narrator’s position in the description of events. There are four types of point of view, but there are only two main options used by most writers:

- Third-person limited point of view is the most common and easiest to use, especially for new writers. In this POV, the characters are referred to in third person (he/she/they) and the narrator has access to the thoughts and feelings to a maximum of one character at a time (and likely one character for the duration of the narrative). You can read more about how to use third-person limited here .

- First-person point of view is also very common and only slightly more difficult. In this POV, the narrator is a character in the story and uses first person pronouns (I/me/mine/we/ours) and has access only to their own thoughts and feelings. This point of view requires an especially strong style, one that shows the narrator's distinct attitude and voice as they tell the story.

The third option is used much less common, though is still found occasionally, especially in older works:

- Third-person omniscient point of view is much more difficult to pull off well and isn't recommended for first time authors. In this POV, the characters are referred to in third-person (he/she/him/her/they/them), but the narrator has access to the thoughts and feelings of any and all characters at the same time. This is a difficult narrative to pull off because of how disorienting it can be for the reader. Readers are placed “in the heads” of so many characters, which can easily destroy the drama of a story because of the lack of mystery.

One final option:

- Second-person point of view is the most difficult to pull off and isn't recommended for most authors. In this POV, the characters are referred to in second person (you/your). This choice is rarely (although not never) found in novels.

Get The Write Structure here »

10. Find the Climactic Moment in Your Novel

Every great novel has a climactic moment that the whole story builds up to—it's the whole reason a reader purchases a book and reads it to the end.

In Moby Dick , it’s the final showdown with the white whale.

In Pride and Prejudice , it’s Lizzie accepting Mr. Darcy’s proposal after discovering the lengths he went to in order to save her family.

In the final Harry Potter novel (spoiler alert!), it’s Harry offering himself up as a sacrifice to Voldemort to destroy the final Horcrux.

To be clear, you don’t have to have your climactic moment all planned out before you start writing your book . (Although knowing this might make writing and finishing your novel easier and more focused.)

But it IS a good idea to know what novels and films similar to yours have done.

For example, if you’re writing a performance story about a violinist, as I am, you need to have some kind of big violin competition at the end of your book.

If you’re writing a police procedural crime novel, you need to have a scene where the detective unmasks the murderer and explains the rationale behind the murder.

Think about the climactic moment your novel builds up before the final showdown at the end. This climactic moment will usually occur in the climax of the second or third act.

If you know this, fill in your outline with the climactic moment, then write out the five key moments of the scene for that moment.

If you don’t know them, just leave them blank. You can always come back to it.

11. Consider the Conventions

Readers are sophisticated. They’ve been taking in stories for years, since they were children, and they have deep expectations for what should be in your story.

That means if you want readers to like your story, you need to meet and even exceed some of those expectations.

Stories do this constantly. We call them conventions, or tropes, and they’re patterns that storytellers throughout history have found make for a good story.

In the romantic comedy (love) genre, for example, there is almost always the sidekick best friend, some kind of love triangle, and a meet cute moment where the two potential lovers meet.

In the mystery genre, the story always begins with a murder, there are one or more red herrings , and there’s a final unveiling of the murder at the end.

Think through the three to five novels and films you read/watched. What conventions and tropes did they have in common?

12. Set Your Intention

You’re almost ready to start writing. Before you do, set your intention.

Researchers have found that when you’re trying to create a new habit, if you imagine where and when you will participate in that habit, you’re far more likely to follow through.

For your writing, imagine where, when, and how much you will write each day. For example, you might imagine that you will write 1,000 words at your favorite coffee shop each afternoon during your lunch break.

As you imagine, picture your location and the writing space clearly in your mind. Watch yourself sitting down to work, typing on your laptop. Imagine your word count tracker going from 999 to 1,002 words.

When it’s time to write , you’ll be ready to go do it.

13. Picture Your Reader

The definition of a story is a narrative meant to entertain, amuse, or instruct. That implies there is someone being entertained, amused, or instructed!

I think it’s helpful to picture one person in your mind as you write (instead of an entire target audience). Then, as you write, you can better understand what would interest, amuse, or instruct them.

By picturing them, you will end up writing better stories.

Create a reader avatar.

Choose someone you know, or make up someone who would love your story. Describe them in terms of demographics and interests. Consider the question, “Why would this reader love my novel?”

When you write, write for them.

14. Build Your Team

Most people think they can write a novel on their own, that they need to stick themselves in some cabin in upstate New York or an attic apartment in Paris and just focus on writing their novel for a few months or decades.

And that’s why most people fail to finish writing a book .

As I’ve studied the lives of great writers, I’ve found that they all had a team. None of them did it all on their own. They all had people who supported and encouraged them as they wrote.

A team can look like:

- An editor with a publishing house

- A writing group

- An author mentor or coach

- An online writing course or community

Whatever you find, if you want to finish your novel, don’t make the mistake of believing you can do it all on your own (or that you have to do it on your own).

Find a writing group. Take an online writing class . Or hire a developmental editor .

Whatever you do, don’t keep trying to do everything by yourself.

15. Plan the Publishing Process

One thing I’ve found is that when successful people take on a task, they think through every part of the process from beginning to end. They create a plan. Their plan might change, but starting with a plan gives them clear focus for what they’re setting out to accomplish.

Most of the steps we’ve been talking about in this post involve planning (writing is coming up next, don’t worry), but in your plan, it’s important to think through things all the way to the end—the publishing and marketing process.

So spend ten or twenty minutes dreaming about how you’ll publish your novel (self-publishing vs. traditional publishing) and how you’ll promote it (to your email list, on social media, via Amazon ads, etc.).

By brainstorming about the publishing and marketing process, you’ll make it much more likely to actually finish your novel because you're eager for (and know what you want to do when you're at) the end.

Have no idea how to get published? Check out our 10-step book publishing and launch guide here .

16. Write (With Low Expectations)

You’ve created a plan. You know what you’re going to write, when you’re going to write it, and how you’re going to write.

Now it’s time to actually write it.

Sit down at the blank page. Take a deep breath. Write your very first chapter.

Don’t forget, your first draft is supposed to be bad.

Write anyway.

17. Trust the Process and Don’t Quit

As I’ve trained writers through the novel writing process in our 100 Day Book Program, inevitably around day sixty, they tell me how hard the process is, how tired they are of their story, how they have a new idea for a novel, and they want to work on that instead.

“Don’t quit,” I tell them. Trust the process. You’re so much closer than you think.

Then, miraculously, two or three weeks later, they’re emailing me to say they’re about to finish their books. They’re so grateful they didn’t quit.

This is the process. This is how it always goes.

Just when you think you’re not going to make it, you’re almost there.

Just when you most want to quit, that’s when you’re closest to a breakthrough.

Trust the process. Don’t quit. You’re going to make it.

Just keep showing up and doing the work (and remember, doing the work means writing imperfectly).

18. Keep Going, Even When It Hurts

Appliances always break when you’re writing a book.

Someone always gets sick making writing nearly impossible (either you or your spouse or all your kids or all of the above).

One writer told us recently a high-speed car chase ended with the car crashing into a building close to her house.

I’m not superstitious, but stuff like this always happens when you’re writing a book.

Expect it. Things will not go according to plan. Major real life problems will occur.

It will be really hard to stay focused for weeks on end.

This is where it’s so important to have a team (step fourteen). When life happens, you’ll need someone to vent to, to encourage you, and to support you.

No matter what, write anyway. This is what separates you from all the aspiring writers out there. You do the work even when it’s hard.

Keep going.

19. Finish Draft One… Then Onward to the Next

I followed this process, and then one day, I realized I’d written the second to last scene. And then the next day, my novel was finished.

It felt kind of anticlimactic.

I had wanted to write a novel for years, more than a decade. I had done it. And it wasn’t as big of a deal as I thought.

Amazing, without question.

But also just normal.

After all, I had been doing this, writing every day for ninety-nine days. Finishing was just another day.

But the journey itself? 100 days for writing a novel? That was amazing.

That was worth it.

And it will be worth it again and again.

Maybe it will be like that for you. You might finish your book and feel amazing and proud and relieved. You might also feel normal. It’s the difference between being an aspiring writer and being a real writer.

Real writers realize the joy is in the work, not in having a finished book .

When you get to this point, I just want to say, “Congratulations!”

You did it.

You finished a book. I’m so excited for you!

But also, as you will know when you get to this point, this is really just the beginning of your journey.

Your book isn’t nearly ready to publish yet.

So celebrate. Throw a party for yourself. Say thank you to all your team members. You finished. You should be proud!

After this celebratory breather, move on to your last step.

20. Next Drafts: Draft Two…Three…Four…Five

This is a novel writing guide, not a novel revising guide (that is coming soon!). But I’ll give you a few pointers on what to do after you write your novel:

- Rest. Take a break. You earned it. Resting also lets you get distance on your book, which you need right now.

- Read without revising. Most people jump right into the proofreading and line editing process. This is the worst thing you could do. Instead, read your novel from beginning to end without making revisions. You can take notes, but the goal for this is to create a plan for your next draft, not fix all your typos and misplaced commas . This step will usually reveal plot holes, character inconsistencies, and other high-level problems.

- Get feedback. Then, share your book with your team: editors and fellow writers (not friends and family yet). Ask for constructive feedback, especially structural feedback, not on typos for now.

- Next, rewrite for structure. Your second draft is all about fixing the structure of your novel. Revisit steps seven through eleven for help.

- Last, polish your prose. Your third (and additional) draft(s) is for fixing typos, line editing, and making your sentences sound nice. Save this for the end, because if you polish too soon, you might have to delete a whole scene that you spent hours rewriting.

Want to know more about what to do next? Check out our guide on what to do AFTER you finish your book here .

Writers’ Best Tips on How to Write a Novel

I’ve also asked the writers I’ve coached for their single tips on how to write a novel. These are from writers in our community who have followed this process and finished novels of their own. Here are their best novel writing tips:

“Get it out of your head and onto the page, because you can’t improve what’s not been written.” Imogen Mann

“What gets scheduled, gets done. Block time in your day to write. Set a time of day, place and duration that you will write 4-7 days/week until it becomes habit. It’s most effective if it’s the same time of day, in the same place. Then set your duration to a number of minutes or a number of words: 60 minutes, 500 words, whatever. Slowly but surely, those words string together into a piece of work!” Stacey Watkins

“Honestly? And nobody paid me for this one—enroll in the 100 Day Book challenge at The Write Practice. I had been writing around in my novel for years and it wasn’t until I took the challenge did I actually write it chapter by chapter from beginning to end in 80,000 words. Of course I now have to revise, revise, revise.” Madeline Slovenz

“I try to write for at least an hour every day. Some days I feel like the creativity flows out of me and others it’s awkward and slow. But yes, my advice is to write for at least one hour every day. It really helps.” Kurt Paulsen

“Be patient, be humble, be forgiving. Patient, because writing a novel well will take longer than you ever imagined. Humble, because being awake to your strengths and your weaknesses is the only way to grow as a writer. And forgiveness, for the days when nothing seems to work. Stay the course, and the reward at the end — whenever that comes — will be priceless. Because it will be all yours.” Erin Halden

“Single best tip I can recommend is the development of a plan. My early writing, historical stories for my world, was done as a pantser. But, when I took the 100 Day Book challenge , one of the steps was to produce an outline. Mine started as the briefest list of chapters. But, as I thought about it, the outline expanded to cover what was happening and who was in it. That lead to a pattern for the chapters, a timeline, and greater detail in the outline. I had always hated outlines, but like Patrick Rothfuss said in one of his interviews, that hatred may have been because of the way it was taught when I was in school (long ago.) I know I will use one for the second book (if I decide to go forward with it.) Just remember the plan is there for your needs. It doesn’t need to be a formal I. A. 1. a. format. It can simply be a set of notecards with general ideas you want to include in your story.” Patrick Macy

“Everybody who writes does so on faith and guts and determination. Just write one line. Just write one scene. Just write one page. And if you write more that day consider yourself fortunate. The more you do, the stronger the writing muscle gets. But don’t do a project; just break things down into small manageable bits.” Joe Hanzlik

“When you’re sending your novel out to beta readers , keep in mind some people‘s feedback may not resonate or be true for your vision of the work. Also, just because you’ve handed off a copy for beta reading doesn’t mean you don’t have control over how people give you feedback. For instance, if you don’t want line editing, ask them not to give paragraph and sentence corrections. Instead, ask for more general feedback on the character arcs, particular scenes in the story, the genre, ideal reader , etc. Be proactive about getting the kind of response you want and need.” B.E. Jackson

“Become your main character. Begin to think and act the way they would.” Valda Dracopoulos

“I write for minimum 3 hours starting 4 a.m. Mind is uncluttered and fresh with ideas. Daily issues and commitment can wait. Make a plan and stick to the basic plan.” R.B. Smith

“Stick to the plan (which includes writing an outline, puttin your butt in the chair and shipping). I’m trying to keep it simple!” Carole Wolf

“Have a spot where you write, get some bum glue, sit and write. I usually have a starting point, a flexible endpoint and the middle works itself out.” Vuyo Ngcakani

“Before I begin, I write down the ten key scenes that must be in the novel. What is the thing that must happen, who is there when it happens, where does it take place. Once I have those key scenes, I begin.” Cathy Ryan

“In my English classes, I was told to ‘show, don’t tell,' which is the most vague rule I’ve ever heard when it comes to writing. Until I saw a post that expanded upon this concept saying to ‘ show emotion, tell feelings …’. Showing emotion will bring the reader closer to the characters, to understand their actions better. But I don’t need to read about how slow she was moving due to tiredness.” Bryan Coulter

“For me, it’s the interaction between all of the characters. It drives almost all of my novels no matter how good or bad the plot may be .” Jonathan Srock

“Rules don’t apply in the first draft; they only apply when you begin to play with it in the second draft.” Victor Paul Scerri

“My best advice to you is: Just Write. No matter if you are not inspired, maybe you are writing how you can’t think of something to write or wrote something that sucks. But just having words written down gets you going and soon you’ll find yourself inspired. You just have to write.” Mony Martinez

“As Joseph Campbell said, “find your bliss.” Tap into a vein of whatever it is that “fills your glass” and take a ride on a stream of happy, joyful verbiage.” Jarrett Wilson

“Show don’t tell is the most cited rule in the history of fiction writing, but if you only show, you won’t get past ch. 1. Learn to master the other forms of narration as well.” Rebecka Jäger

“We’ve all been trained jump when the phone rings, or worse, to continually check in with social media. Good work requires focus, but I’ve had to adopt some hacks to achieve it. 1) Get up an hour before the rest of the household and start writing. Don’t check email, Facebook, Instagram, anything – just start working. 2) Use a timer app, to help keep you honest. I set it for 30 minutes, then it gives me a 5-minute break (when things are really humming, I ignore the breaks altogether). During that time, I don’t allow anything to interrupt me if I can help it. 3) Finally, set a 3-tiered word count goal: Good, Great, Amazing. Good is the number of words you need to generate in order to feel like you’ve accomplished something (1000 words, for example). Great would be a higher number, (say, 2000 words). 3000 words could be Amazing. What I love about this strategy is that it’s forgiving and inspiring at the same time.” Dave Strand

“My advice comes in two parts. First, I think it’s important to breathe life into characters, to give them emotions and personalities and quirks. Make them flawed so that they have plenty of room to grow. Make them feel real to the reader, so when they overcome the obstacles you throw in their way, or they don’t overcome them, the reader feels all the more connected and invested in their journey. Second, I think there’s just something so magical about a scene that transports me, as a reader, to the characters’ world; that allows me to see, feel, smell, and touch what the characters are experiencing. So, the second part of my advice is to describe the character’s experience of their surroundings keeping all of their senses in mind. Don’t stop simply with what they see.” Jennifer Baker

“Start with an outline (it can always be changed), set writing goals and stick to them, write every day, know that your first draft is going to suck and embrace that knowledge, and seek honest feedback. Oh, and celebrate milestones, especially when you type ‘The End’. Take a break from your novel (but don’t stop writing something — short stories, blog posts, articles, etc.) and then dive head-first into draft 2!” Jen Horgan O’Rourke