- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Special Issues

- Supplements

- Virtual Collection

- Online Only Articles

- International Spotlight

- Free Editor's Choice

- Free Feature Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Calls for Papers

- Why Submit to the GSA Portfolio?

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Journals Career Network

- About The Gerontologist

- About The Gerontological Society of America

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- GSA Journals

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Design and methods, implications, conclusions.

- < Previous

Dementia Care Mapping: A Review of the Research Literature

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Dawn Brooker, Dementia Care Mapping: A Review of the Research Literature, The Gerontologist , Volume 45, Issue suppl_1, October 2005, Pages 11–18, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.11

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Purpose: The published literature on dementia care mapping (DCM) in improving quality of life and quality of care through practice development and research dates back to 1993. The purpose of this review of the research literature is to answer some key questions about the nature of the tool and its efficacy, to inform the ongoing revision of the tool, and to set an agenda for future research. Design and Methods: The DCM bibliographic database at the University of Bradford in the United Kingdom contains all publications known on DCM ( http://www.bradford.ac.uk/acad/health/dcm ). This formed the basis of the review. Texts that specifically examined the efficacy of DCM or in which DCM was used as a main measure in the evaluation or research were reviewed. Results: Thirty-four papers were categorized into five main types: (a) cross-sectional surveys, (b) evaluations of interventions, (c) practice development evaluations, (d) multimethod evaluations, and (e) papers investigating the psychometric properties of DCM. Implications: These publications provide some evidence regarding the efficacy of DCM, issues of validity and reliability, and its use in practice and research. The need for further development and research in a number of key areas is highlighted.

Dementia Care Mapping (DCM; Bradford Dementia Group, 1997 ) is an observational tool that has been used in formal dementia-care settings over the past 13 years, both as an instrument for developing person-centered care practice and as a tool in quality-of-life research. It developed from the pioneering work of the late Professor Tom Kitwood on person-centered care. In his final book, Dementia Reconsidered, Kitwood (1997) described DCM as “a serious attempt to take the standpoint of the person with dementia, using a combination of empathy and observational skill” (p 4). The instrument has been described fully elsewhere ( Kuhn, Ortigara, & Kasayka, 2000 ). In brief, an observer (mapper) tracks 5 people with dementia (participants) continuously over a representative time period (e.g., 6 hr during the waking day). Mapping takes place in communal areas of care facilities. After each 5-min period (a time frame), two types of codes are used to record what has happened to each individual. The behavioral category code (BCC) describes 1 of 24 different domains of participant behavior that has occurred. BCCs are subdivided into those behaviors that are thought to have high potential for well-being (Type 1) and those with low potential (Type 2). The mapper also makes a decision for each time frame, based on behavioral indicators, about the relative state of ill-being or well-being experienced by the person with dementia, called a well- or ill-being value (WIB). This is expressed on a 6-point scale ranging from extreme ill-being to extreme well-being. WIB values can be averaged to arrive at a WIB score. This provides an index of relative well-being for a particular time period for an individual or a group.

Personal detractions (PDs) and Positive events (PEs) are recorded whenever they occur. Personal detractions are staff behaviors that have the potential to undermine the personhood of those with dementia ( Kitwood, 1997 ). These are described and coded according to type and severity. Positive events—those that enhance personhood—also are recorded by the mapper, but these are not coded in a systematic manner.

DCM is grounded in the theoretical perspective of a person-centered approach to dementia care. Person-centered care values all people regardless of age and health status, is individualized, emphasizes the perspective of the person with dementia, and stresses the importance of relationships ( Brooker, 2004 ). Within Kitwood's writing is the assumption that, for people with dementia, well-being is a direct result of the quality of relationships they enjoy with those around them. The interdependency of the quality of the care environment to the relative quality of life experienced by people with dementia is central to person-centered care practice. In placing DCM in the taxonomy of measures of quality of life and quality of care, DCM attempts to measure elements of both. In its BCCs and WIBs, DCM measures relative well-being, affect, engagement, and occupation, which are important elements of quality of life. Through PDs and PEs, DCM records the quality-of-care practice as it promotes or undermines the personhood of those being mapped.

The method and coding system were originally developed through ethological observations of many hours in nursing homes, hospital facilities, and day care facilities in the United Kingdom ( Kitwood & Bredin, 1994 ). It was designed primarily as a tool to develop person-centered care practice over time with data being fed back to care teams who could then use it to improve their practice. The original development work is not available in the public domain. DCM has been criticized for this ( Adams, 1996 ). Also, many of the basic psychometric tests expected in the development of such a complex tool were not published.

Despite this, DCM has grown in popularity over the years. Many practitioners have used these codes successfully in many different situations and continue to do so. The reasons for this have not been systematically investigated. In part, it may be because DCM provides a vehicle for those wishing to systematically move dementia care from primarily a custodial and task-focused model into one that respects people with dementia as human beings. There are very few other tools that purport to do this or that have been shown to be effective in this endeavor in the field of dementia care.

DCM certification is only available through licensed trainers who undergo rigorous preparation for their role and use standardized training methods prepared by the University of Bradford. The basic training is a 3-day course, with further options of advanced training and evaluator status also available. DCM training is currently available in the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, Denmark, Australia, Switzerland, and Japan.

DCM has been through a number of changes since its inception. Until 1997, DCM 6 th edition was used. In 1997, DCM was revised based on feedback from practitioners resulting in the 7 th edition ( Bradford Dementia Group, 1997 ). The changes were made, in part, to clarify terminology (e.g., care values became well- or ill-being values); there was an increase in the number of BCCs, from 17 to 24, and PEs were formally recorded as part of the DCM evaluation. There were, however, no published papers demonstrating the relationship between scores on the 6 th and 7 th editions of DCM. During the past 3 years, various international working groups and field trials have made suggestions for revisions to DCM 7. DCM 8 will be launched in late 2005 in the United Kingdom.

Beavis, Simpson, and Graham (2002) reviewed literature on DCM from 1992 until June 2001 and identified nine papers that met their inclusion criteria. There have been important papers published since this time, and, using similar inclusion criteria (discussed below), the current review identified 34 papers. This review aims to clarify what is known about the DCM tool and to inform the direction of DCM 8 and future research.

The international DCM network led by the University of Bradford maintains a DCM bibliographic database that contains all known publications on DCM ( http://www.bradford.ac.uk/acad/health/dcm ). This database formed the basis of this review. It includes refereed and nonrefereed journal articles, book chapters, theses, and non-English language texts. It is updated by the Bradford Dementia Group with annual bibliographic searches on Medline, Cinahl, and Psychinfo using the terms “DCM” and “dementia care mapping” as well as personal correspondence from practitioners and researchers.

I included articles that specifically examined the efficacy of DCM or in which DCM was a main measure in evaluation or research. There were no exclusion criteria based on quality of scientific design. Articles that were purely descriptive were excluded, as were dissertations. There are many additional articles and publications that describe aspects of DCM and its use. Some of these will be referred to in the discussion. The review includes articles published between 1993 and March 2005.

I assigned each article to one of five categories according to its basic purpose in using DCM. I developed tables that summarize key parameters pertinent to this review: (a) settings and size; (b) aims of study as set out by the authors; (c) length of time mapped; (d) sample selection and characteristics; (e) study design; (f) version of DCM used; (g) interrater reliability; (h) DCM outcomes, (i) statistical tests; and (j) level of significance. (The full tables summarizing each article can be downloaded from the Web site previously mentioned or are available on request from the author.)

Thirty-four articles met the inclusion criteria. They were divided into five main types.

1. Cross-Sectional Surveys

In 11 articles, DCM was used in a number of different facilities, and the results either compared or pooled. Some of these presented baseline data for intended further studies ( Wilkinson, 1993 ; Williams & Rees, 1997 ; Younger & Martin, 2000 ) whereas others had the explicit aim of surveying quality of care or quality of life ( Ballard et al., 2001 ; Innes & Surr, 2001 ; Kuhn, Kasayka, & Lechner, 2002 ; Perrin, 1997 ). An additional 4 articles used DCM to investigate the relationship between participants' characteristics and well-being and activity ( Chung, 2004 ; Kuhn, Edelman, & Fultom, 2005 ; Kuhn, Fulton, & Edelman, 2004 ; Potkins et al., 2003 ).

Seven of these articles presented data from U.K. long-term facilities ( Ballard et al., 2001 ; Innes & Surr, 2001 ; Perrin, 1997 ; Potkins et al., 2003 ; Wilkinson, 1993 ; Williams & Rees, 1997 ; Younger & Martin, 2000 ). Three were U.S. studies examining assisted living facilities and day care facilities ( Kuhn et al., 2002 ; Kuhn, Edelman, & Fulton, 2005 ; Kuhn, Fulton, & Edelman, 2004 ), and 1 was from Hong Kong ( Chung, 2004 ). They ranged in size from 30 people in 6 facilities surveyed by Wilkinson (1993) to the largest study by Ballard and colleagues (2001) , who surveyed 218 people in 17 facilities; the average study size was 110 people in 8 facilities. All mapped for around 6 hr, except for Williams and Rees (1997) and Younger and Martin (2000) , who mapped for 12 hr. DCM 6 was used by Wilkinson (1993) , Perrin (1997) , and Williams and Rees (1997) .

2. Evaluation of Intervention

There were 10 articles in which DCM was used to evaluate the impact of various interventions on the lives of people with dementia. Bredin, Kitwood, and Wattis (1995) first used DCM to evaluate the impact of merging two wards. It has been used to evaluate a number of nonpharmacological therapeutic interventions, such as group reminiscence ( Brooker & Duce, 2000 ), aromatherapy ( Ballard, O'Brien, Reichelt, & Perry, 2002 ), sensory stimulation groups ( Maguire & Gosling, 2003 ), intergenerational programs ( Jarrott & Bruno, 2003 ), and horticultural therapy ( Gigliotti, Jarrott, & Yorgason, 2004 ). It also has been used as part of the evaluation of larger scale changes in therapeutic regimen, for example outdoor activities ( Brooker, 2001 ), person-centered care training ( Lintern, Woods, & Phair, 2000a ), a liaison psychiatry service ( Ballard, Powell, et al., 2002 ), and a double-blind, placebo-controlled, neuroleptic discontinuation study ( Ballard et al., 2004 ).

Length of time for which mapping occurred was much more varied with the shortest time being 30 min ( Maguire & Gosling, 2003 ) to the longest at 5 days per participant ( Jarrott & Bruno, 2003 ). Studies ranged in size from the smallest, n = 14 ( Gigliotti et al., 2004 ), to the largest, n = 82 ( Ballard et al., 2004 ).

All evaluations were a within-subjects design, apart from Jarrott and Bruno (2003) , who compared two groups. Control groups were used in just over half the studies ( Ballard, O'Brien, et al., 2002 ; Ballard, Powell, et al., 2002 ; Ballard et al., 2004 ; Brooker, 2001 ; Brooker & Duce, 2000 ; Gigolotti et al., 2004 ; Jarrott & Bruno). Demonstrable changes in DCM scores were shown in all studies with the exceptions of Lintern and colleagues (2000a) ; Ballard, Powell, and colleagues; and Ballard and colleagues. Statistically significant changes in DCM scores were demonstrated in Bredin and colleagues (1995) ; Brooker and Duce; Brooker (2001) ; Ballard, O'Brien, and colleagues; Jarrott and Bruno; and Gigliotti and colleagues.

3. Evaluation of DCM in Practice Development

Six articles investigated the ability of DCM to develop practice over time by means of repeated evaluations. In these reports DCM was used in a developmental process or in a continuous quality-improvement cycle with the explicit goal of using DCM data to change care practice. Barnett (1995) ; Brooker, Foster, Banner, Payne, and Jackson (1998) , and Martin and Younger (2001) report results across a number of facilities, whereas Lintern, Woods and Phair (2000b) ; Martin & Younger (2000) , and Wylie, Madjar, & Walton (2002) report results from single facilities. In the largest of these studies, Brooker and colleagues reported DCM across nine facilities for three annual cycles; the smallest of these was Martin and Younger (2000) . DCM 6 was used by Barnett; Lintern and colleagues (2000a) , and Brooker and colleagues. All of the studies showed demonstrable changes in DCM scores over time. Brooker and colleagues was the only study to use statistical analysis to demonstrate the significance of change over time.

4. MultiMethod Qualitative Evaluations

Three articles reported using DCM as part of a multimethod evaluation of a single facility or service ( Barnett, 2000 ; Parker, 1999 ; Pritchard & Dewing, 2001 ). All these articles were qualitative evaluations and used DCM in this frame.

5. Investigations of Psychometric Properties

Four studies looked directly at some of the psychometric properties of DCM. Fossey, Lee, and Ballard (2002) examined internal consistency, test–retest and concurrent validity, and shortened mapping time in a U.K. long-term population of 2 cohorts of 123 and 54, respectively. The 2 cohorts were chosen to increase the variance in dependency and agitation. All were mapped for 6 hr on each occasion, 24 mapped 1 week apart, and 30 mapped between 2 and 4 weeks apart. Test–retest reliability was established for both cohorts. Internal consistency was demonstrated between the main parameters. A correlation was found between key parameters in the hour prior to lunch and the total 6-hr map.

Edelman, Fulton, and Kuhn, (2004) compared five dementia-specific quality-of-life measures, including DCM, in 54 people with dementia in 3 U.S. day-care facilities. WIB scores did not correlate with quality-of-life interviews but did correlate with proxy measures. WIB scores did not correlate with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores but they did with the number of dependent activities of daily living (ADLs). In a second study on 166 people with dementia in 8 different facilities, Edelman, Kuhn, and Fulton (2004) further assessed the relationship between DCM and MMSE scores, number of dependent ADLs, depressive symptoms, and facility type. Low WIB scores and higher percentages of sleep correlated with low MMSE scores and higher dependency. WIB scores were lower in dementia specific nursing homes than assisted living facilities and day care. There was not a significant relationship between DCM scores and depressive symptoms.

Thornton, Hatton, and Tatham (2004) assessed interrater reliability in routine mapping on 20 participants. They also compared BCCs to actual amount of time spent in different behaviors and looked at the relationship between dependency and WIB scores in 64 patients in a U.K. long-stay and day-care facility. They found that interrater reliability in routine maps was less than 50% for 12 codes. They also demonstrated that DCM gives lower indication of passive and withdrawn behaviors than continuous time sampling. Correlations between dependency and WIB score also were demonstrated.

DCM Data Across Studies

Despite the variety of studies, there is consistency of what they report in terms of DCM data. In long-term care, BCC codes A (social interaction), B (watching), and F (eating and drinking) appear as the most frequent codes almost without exception. Codes K (walking) and N (sleeping) appear as the next most frequently cited. In facilities with lower WIB scores, C (withdrawn) and W (repetitive self-stimulation) appear in the top five ( Chung, 2004 ; Innes & Surr, 2001 ; Perrin, 1997 ). In facilities with higher WIB scores, codes E (creative activity), J (exercise), and M (engaging with media such as books, TV) appear more frequently ( Brooker et al., 1998 ; Kuhn et al., 2002 ; Martin & Younger, 2001 ). Taking the group WIB scores across the studies as a whole ( n = 39, excluding the less well-described studies) these provided an average (mean) group WIB of 0.9 ( SD = 0.92) for long-term care. Group WIB scores from long-term care facilities ranged between −0.32 ( Ballard et al., 2001 ) to 1.5 ( Innes & Surr, 2001 ).

Generally, a greater diversity of BCCs and higher WIB scores are reported in day-care facilities ( Barnett, 2000 ; Brooker et al., 1998 ; Kuhn et al., 2004 ; Martin & Younger, 2001 ; Williams & Rees 1997 ) with BCC codes M (media), G (games), L (work-like activity) and I (intellectual), J (physical exercise), E (creative expression), and H (handicrafts) appearing in the top five reported codes. Of the eight day-care group WIB scores reported, the mean is 1.94 (range = 1.17 to 2.79, SD = 0.47). WIB scores and diversity of activity both increase during periods of therapeutic activity ( Brooker & Duce, 2000 ; Gigliotti et al., 2004 ; Jarrott & Bruno, 2003 ; Maguire & Gosling, 2003 ; Pritchard & Dewing, 2001 ; Wilkinson, 1993 ).

There is less data available for assisted-living facilities, the only report being Kuhn and colleagues (2002) . The spread of WIB scores and the frequency of BCCs were similar to those reported for nursing home facilities. Lower scores, less diversity of activity, and a greater occurrence of personal detractions occurred in the smaller dementia-specific facilities rather than in larger mixed facilities, although this could have been confounded with greater dependency in the smaller facilities.

Many published DCM evaluations do not report PDs. A number suggest that the highest level of PDs occur in those facilities with the lowest WIB scores ( Brooker et al., 1998 ; Innes & Surr, 2001 ; Kuhn et al., 2002 ; Williams & Rees, 1997 ). Most PDs reported fall in the mild to moderate category. Innes and Surr were the only authors to report positive events. Nineteen of the studies reported interrater reliability data which ranged from 0.7 to 1.0, most reporting concordance coefficients of 0.8.

These studies can help to answer, at least in part, some common questions about DCM. In addition to this, issues are highlighted that should be taken forward in the development of DCM.

Does DCM Measure Quality of Care and/or Quality of Life?

In terms of concurrent validity with other measures there is some evidence that DCM is related to indicators of quality of care. Bredin and colleagues (1995) reported a relationship between a decrease in DCM scores and an increase in pressure sores. Brooker and colleagues (1998) reported a clustering of high WIB scores occurring in facilities where other quality audit tools demonstrated better quality of care.

There is some evidence of concurrent validity of WIB scores with proxy quality-of-life measures. Fossey and colleagues (2002) demonstrated a significant correlation between WIB scores and the Blau (1977) proxy measure of quality of life. Edelman and colleagues (2004) demonstrated a moderately significant correlation between WIB scores and two staff proxy measures of quality of life—the Quality of Life AD–Staff ( Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, 2000 ) and the Alzheimer's Disease-Related Quality of Life (ADRQL; Rabins, Kasper, Kleinman, Black, & Patrick, 1999 ) in adult day care. This study did not demonstrate a correlation between any of these measures compared to direct quality-of-life interviews with a less cognitively impaired subgroup. In his multimethod study, Parker (1999) noted that during interviews, people with dementia rated their quality of life as better than their DCM scores would suggest.

Data from a larger, as yet unpublished, study ( Edelman, Kuhn, Fulton, Kasayka, & Lechner, 2002 ) also compared DCM results with another observational measure—the Affect Rating Scale ( Lawton, 1997 ). On the Affect Rating Scale, positive WIBs correlated with positive affect and negative WIB scores with negative affect. Brooker and colleagues (1998) also demonstrated a significant correlation between WIB score and level of observed engagement ( McFayden, 1984 ) on a small sample of 10 participants.

DCM measures something similar to proxy measures and other observation measures. DCM is somewhat different from other quality-of-life and quality-of-care measures in that it attempts to measure elements of both. In training to use DCM, mappers are explicitly taught to increase their empathy for the viewpoint of the person with dementia and to use this during their coding decisions.

Can Different Mappers Use DCM Reliably?

When many different mappers are engaged in mapping at different points in time, drifts in coding can have a significant impact on results ( Thornton et al., 2004 ) unless systematic checking is in place to prevent this. It is perfectly possible to achieve acceptable interrater reliability as many of the studies here demonstrate. Surr and Bonde-Nielsen (2003) outline the various ways in which reliability can be achieved in routine mapping. Although interrater reliability can be demonstrated within studies—and should always be so where more than a single mapper has been used—it cannot be assumed when comparing one study to another. This is a major challenge for those providing DCM training. One of the main ways of achieving interrater reliability in practice is for all mappers to have regular checks with a “gold standard mapper.” Provisions need to be made to make the status of a gold standard mapper more formalized, possibly through advanced DCM training. This status could be accredited by regular web-based or video role-play materials that mappers have to code correctly to maintain their status.

In terms of the development of DCM 8, efforts should be made to decrease ambiguity in the codes and to eliminate any unnecessary complexity from the rules. Thornton and colleagues (2004) and work currently being undertaken in Germany ( Ruesing, 2003 ) have helped clarify the most problematic codes. There are no published data on the interrater reliability of PD and PE recordings. This also should be incorporated in DCM 8.

Only Fossey and colleagues (2002) looked at test–retest reliability. The best correlation was between percentage of +3 and +5, followed by overall WIB score. Significance was more moderate for type of BCC but still at an acceptable level. This finding requires replication.

Does DCM Show Representative Reliability Across All People With Dementia?

There is evidence to suggest that level of dependency is correlated with DCM scores, specifically that low WIB scores are associated with high dependency levels. This has been demonstrated statistically on three different continents ( Brooker et al., 1998 ; Chung, 2004 ; Edelman et al., 2004 ; Kuhn et al., 2004 ; Thornton et al., 2004 ) using three different measures of dependency.

On the other hand, Younger and Martin (2000) found the highest scores in their study occurred in the facility that had the most dependent participants. Edelman and colleagues (2004) , Jarrott and Bruno (2003) , and Gigliotti and colleagues (2004) demonstrated no correlation between level of cognitive impairment and WIB score.

The correlations between low WIB scores and high dependency may of course be related to a third factor of poorer quality of psychosocial care for people with dementia who have high dependency needs. In support of this, Brooker and colleagues (1998) found that the correlation between dependency and WIB score disappeared after three successive cycles of DCM. The authors believed that, by this stage, ways of supporting well-being of participants who were highly dependent had been better established.

It is also not clear whether there are particular features that are more prevalent in higher dependency groups that might either make a subset more difficult to engage with and thus more difficult for them to achieve higher DCM scores. For example, Potkins and colleagues (2003) demonstrated that language dysfunction was associated with poorer BCC distribution regardless of level of cognitive impairment.

The evidence that dependency level skews DCM results is strong enough to suggest that a measure of dependency should be routinely taken alongside DCM evaluations so that the results can be scrutinized for this relationship. One of the problems with doing this is agreeing on a particular measure of dependency. The Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly measure (CAPE; Pattie & Gilleard, 1979 ) has been used most often but is difficult to access and not culturally appropriate outside the United Kingdom. A standard measure of dependency to be used alongside DCM needs to be agreed upon.

Does DCM Change Care Practice?

In 2001, an international “think tank” of DCM practitioners came together to review their collective experience on DCM ( Brooker & Rogers, 2001 ). Their conclusions from practice were that DCM, used within an organizational framework that supported person-centered care, could improve levels of well-being, increase the diversity of occupation, and decrease the incidence of personal detractions. The published developmental evaluations reviewed here supports this assertion both for larger scale quality-assurance initiatives ( Brooker et al., 1998 , Martin & Younger, 2001 ) and more in-depth developments in single establishments ( Lintern et al., 2000b ; Martin & Younger, 2000 ; Wylie et al., 2002 ). The face validity of DCM for practitioners appears high in formal evaluations (Brooker et al.; Younger & Martin, 2000 ) and in the large numbers of people undertaking DCM training.

DCM has been used as a tool for practice development by many people and organizations. The mix of papers in this review cannot be taken as a reflection of the way in which DCM is used generally. By the nature of their work, those in practice development are less likely to publish than those engaged in research. The research issue for whether DCM changes care practice is to clarify the way in which DCM is used and the organizational setting conditions necessary to maximize impact.

A difficult issue, in terms of validity for practice development, is whether using DCM in a repeated cycle of evaluations actually improves quality of life for people with dementia. A problem with all of the studies outlined above is that their only measure of improvement was DCM. In other words, DCM served as both the intervention and the outcome measure. Without a longitudinal controlled study of DCM as a tool for practice development, which utilizes other quality of life measures as the main outcome, it cannot be said categorically that DCM improves quality of life. There are many practitioners who believe that DCM does have a positive impact when used within certain setting conditions ( Brooker & Rogers, 2001 ). In the context of working in a field where tools for practice development are not common, DCM is a tool that practitioners want to use.

Is DCM a Suitable Tool for Research?

DCM was not designed to be a research tool, and investigations into its reliability and validity are only just beginning to appear. Acceptable interrater reliability is achievable, and concurrent validity with other proxy measures of quality of life has been demonstrated. Fossey and colleagues (2002) demonstrated internal consistency and test–retest reliability. These findings require replication, and the issue of the impact of dependency and diagnosis on scores needs to be determined, as does the impact of care regimen. Further research into its psychometric properties continues, and more studies are expected. Careful consideration should be given in deciding whether DCM is fit for purpose given the specific topic under investigation.

DCM has been used in cross-sectional surveys, evaluations of interventions, and multimethod qualitative evaluations by a number of researchers. In terms of cross-sectional surveys, there are tools that may be more suited to this task that do not have the attendant time-consuming problems and specialist training associated with DCM ( Edelman et al., 2004 ). Whether they would be better tools for the purpose of answering the specific research questions is debatable.

From the studies presented here, DCM seems to be suited to smaller scale within-subjects or group comparison intervention evaluations, given that it appears to demonstrate discrimination on a variety of interventions. In multimethod qualitative designs, DCM appears to enrich the data derived from proxy and service-user interviews and focus groups. DCM provides an opportunity to represent a reflection on what could be the viewpoint of service users who are unable to participate fully in interviews.

What is clear is that BCCs do not measure real-time estimates of different types of behavior ( Thornton et al., 2004 ). Because of the rules of coding in DCM, it will underestimate the occurrence of socially passive and withdrawn behavior compared to data collected with continuous time sampling. Researchers interested in looking at withdrawn and passive behavior might be better advised to use another tool. It is worthy of note, however, that despite this, three studies ( Ballard, O'Brien et al., 2002 ; Gigliotti et al., 2004 ; Potkins et al., 2003 ) found DCM discriminated between groups on social withdrawal in their evaluations.

There are a number of modifications to DCM that might prove useful when using DCM in research. A current U.S.-led project is considering whether some of the operational rules within DCM for selecting specific BCC and WIBs should be changed for the purposes of research evaluations. A number of studies reviewed that presented group-level data have collapsed the number of BCCs into a number of supracategories ( Chung, 2004 ; Gigliotti et al., 2004 ; Kuhn et al., 2004 ). It may be that streamlining DCM further by using time sampling could provide a more useful research alternative as has already been tried by McKee, Houston, and Barnes (2002) . Further research is needed to clarify how streamlined versions relate to the full tool and whether the same degree of training would be necessary to use them.

What Do the Scores Mean in Terms of Benchmarking?

The table on how to interpret DCM data in the DCM manual ( Bradford Dementia Group, 1997 ) is not based on published data. Evidence from this review presents a range of group WIB scores against which to benchmark, suggesting that scores are generally higher in day care than long-stay care. How much this is confounded by the different dependency levels is unclear. Work is currently underway to develop an international database of DCM results to which all international strategic DCM partners would have access. The database should include participant and facilities factors that could be used in stratified analyses, correlational studies, and as adjustment factors. The quality of DCM data in the international database could be safeguarded by only accepting data that has been verified by a gold-standard mapper.

What Is a Significant Change in Scores?

Published studies that have looked at change through developmental evaluation report group WIB changes in the range of 0.5. A study by Brooker and colleagues (1998) was the only developmental evaluation to present a statistical analysis of the results where changes of 0.1 to 0.5 were significant at the 0.03 level over 3 data points, and changes at 0.7 and 0.9 were significant at the 0.005 and 0.001 level, respectively, between 2 data points. Intervention studies ( Brooker & Duce, 2000 ; Brooker, 2001 ; Gigliotti et al, 2004 ; Jarrott & Bruno, 2003 ) report differences in the range of 0.4 to 1.1, which were all statistically significant. Changes in individual WIB scores, WIB value profiles, and BCC profiles are more variable. Further research is needed to clarify what constitutes a clinically significant change.

How Long Should a Map Be?

Six hr is the current guidance in DCM training, but there is no empirical evidence to verify the representativeness of this time period. Most of the studies here have mapped for 6 hr, although those using DCM for practice-development purposes mapped for much longer ( Brooker et al., 1998 ; Martin & Younger, 2001 ; Williams & Rees; Wylie et al., 2002 ). It also is evident from practice that useful insights can be gained from mapping for just a couple of hours ( Heller, 2004 ). Length of maps will depend, in part, on the reason for mapping, but there is a drive to spend the least amount of time possible collecting data. Fossey and colleagues (2002) found a statistically significant correlation between the hour prior to lunch and a 6-hr map on all their key indicators at the group level. It is likely that there would be a great deal more variation on an individual level. An unpublished U.S study ( Douglass & Johnson, 2002 ) mapped 18 residents during a 6-day period for periods of 2, 4, 6, and 8 hr in a continuing care retirement community. Acceptable levels of interrater reliability were demonstrated in maps of more than 4 hr in duration. This important issue requires further research.

These studies report evidence that DCM has a role in practice development and research within the broad aim of improving the quality of the lived experience for people with dementia. Priority should be given to a controlled longitudinal study to evaluate fully the impact of DCM in improving quality of life through practice development. A large international database on DCM results would help clarify the relationship between DCM results, dependency, diagnostic group, and facility characteristics. Steps need to be taken through the development of the method, training, and accreditation to ensure reliability. Further research would help clarify the clinical significance of change in scores, the length of mapping, and amendments to the method when it is used as a research tool.

The published work on DCM is of variable quality but is growing in strength. DCM's advantages are that it is standardized, quality controlled, international, responsive to change, multidisciplinary, and has an increasing research base. DCM provides a shared language and focus across professional disciplines, care staff, and management teams. It is seen as a valid measure by frontline staff as well as those responsible for managing and commissioning care. It also provides a shared language between practitioners and researchers. DCM holds a unique position in relation to quality of life in dementia care, being both an evaluative instrument and as a vehicle for practice development in person-centered care. Many of the intervention evaluations cited above have been undertaken because DCM has given practitioners a way of trying to evaluate their practice. Maintaining a dialogue between the worlds of research and practice in health and social care is a major challenge. DCM provides an opportunity to do this.

Thanks go to the anonymous reviewers of an earlier version of this paper and to my DCM colleagues, Claire Surr and Carolinda Douglass.

Bradford Dementia Group, School of Health Studies, University of Bradford, Yorkshire, UK.

Decision Editor: Richard Schulz, PhD

* Indicates articles included in the review.

Adams, T., ( 1996 ). Kitwood's approach to dementia and dementia care: A critical but appreciative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23 , 948 -953.

*Ballard, C., Fossey, J., Chithramohan, R., Howard, R., Burns, A., & Thompson, P., et al ( 2001 ). Quality of care in private sector and NHS facilities for people with dementia: Cross sectional survey. British Medical Journal, 323 , 426 -427.

*Ballard, C., O'Brien, J. T., Reichelt, K., & Perry, E., ( 2002 ). Aromatherapy as a safe and effective treatment for the management of agitation in severe dementia: The results of a double blind, placebo-controlled trial with Melissa. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63 , 553 -558.

*Ballard, C., Powell, I., James, I., Reichelt, K., Myint, P., & Potkins, D., et al ( 2002 ). Can psychiatric liaison reduce neuroleptic use and reduce health service utilization for dementia patients residing in care facilities? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17 , 140 -145.

*Ballard, C., Thomas, A., Fossey, J., Lee, L., Jacoby, R., & Lana, M., et al ( 2004 ). A 3-month, randomised, placebo-controlled, neuroleptic discontinuation study in 100 people with dementia: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory is a predictor of clinical outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65 , 114 -119.

*Barnett, E., ( 1995 ). A window of insight into quality of care. Journal of Dementia Care, 3 , (4), 23 -26.

*Barnett, E., ( 2000 ). Including the person with dementia in designing and delivering care—‘I need to be me!’ . London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Beavis, D., Simpson, S., & Graham, I., ( 2002 ). A literature review of dementia care mapping: Methodological considerations and efficacy. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9 , 725 -736.

Blau, T. H., ( 1977 ). Quality of life, social indicators, and criteria of change. Professional Psychology, 8 , 464 -473.

Bradford Dementia Group. ( 1997 ). Evaluating dementia care: The DCM Method (7 th ed.). Bradford, U.K.: University of Bradford.

*Bredin, K., Kitwood, T., & Wattis, J., ( 1995 ). Decline in quality of life for patients with severe dementia following a ward merger. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 10 , 967 -973.

*Brooker, D., ( 2001 ). Enriching lives: Evaluation of the ExtraCare Activity Challenge. Journal of Dementia Care, 9 , (3), 33 -37.

Brooker, D., ( 2004 ). What is person-centred care for people with dementia? Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 13 , 215 -222.

*Brooker, D., & Duce, L., ( 2000 ). Well-being and activity in dementia: A comparison of group reminiscence therapy, structured goal-directed group activity, and unstructured time. Aging & Mental Health, 4 , 354 -358.

*Brooker, D., Foster, N., Banner, A., Payne, M., & Jackson, L., ( 1998 ). The efficacy of Dementia Care Mapping as an audit tool: Report of a 3-year British NHS evaluation. Aging & Mental Health, 2 , 60 -70.

Brooker, D., & Rogers, L., (Eds.) ( 2001 ). DCM think tank transcripts 2001 . Bradford, U.K.: University of Bradford.

*Chung, J. C. C., ( 2004 ). Activity participation and well-being in people with dementia in long-term care settings. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 24 , (1), 22 -31.

Douglass, C., & Johnson, A., ( 2002 ). Implementation of DCM in a long-term care setting: Measures of reliability, validity, and ease of use . Paper presented as part of the symposium on DCM at The Gerontological Society of America annual scientific meeting, Boston, MA.

*Edelman, P., Fulton, B. R., & Kuhn, D., ( 2004 ). Comparison of dementia-specific quality of life measures in adult day centers. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 23 , 25 -42.

*Edelman, P., Kuhn, D., & Fulton, B. R., ( 2004 ). Influence of cognitive impairment, functional impairment, and care setting on dementia care mapping results. Aging and Mental Health, 8 , 514 -523.

Edelman, P., Kuhn, D., Fulton, B., Kasayka, R., & Lechner, C., ( 2002 ). The relationship of DCM to five measures of dementia specific quality of life . Paper presented as part of the symposium on DCM at The Gerontological Society of America annual scientific meeting, Boston, MA.

*Fossey, J., Lee, L., & Ballard, C., ( 2002 ). Dementia Care Mapping as a research tool for measuring quality of life in care settings: Psychometric properties. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17 , 1064 -1070.

*Gigliotti, C. M., Jarrott, S. E., & Yorgason, J., ( 2004 ). Harvesting health: Effects of three types of horticultural therapy activities for persons with dementia. Dementia, 3 , 161 -170.

Heller, L., ( 2004 ). The Thursday Club. In D. Brooker, P. Edwards, & S. Benson (Eds.), DCM: Experience and insights into practice (pp. 110–111). London: Hawker Publications.

*Innes, A., & Surr, C., ( 2001 ). Measuring the well-being of people with dementia living in formal care settings: The use of Dementia Care Mapping. Aging and Mental Health, 5 , 258 -268.

*Jarrott, S. E., & Bruno, K., ( 2003 ). Intergenerational activities involving persons with dementia: An observational assessment. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 18 , 31 -37.

Kitwood, T., ( 1997 ). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first . Buckingham, U.K.: Open University Press.

Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K., ( 1994 ). Charting the course of quality care. Journal of Dementia Care, 2 , (3), 22 -23.

Kuhn, D., Edelman, P., & Fulton, B. R., ( 2005 ). Daytime sleep and the threat to well-being of persons with dementia. Dementia, 4 , 233 -247.

*Kuhn, D., Fulton, B. R., & Edelman, P., ( 2004 ). Factors influencing participation in activities in dementia care settings. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly, 5 , 144 -152.

*Kuhn, D., Kasayka, R., & Lechner, C., ( 2002 ). Behavioral observations and quality of life among persons with dementia in 10 assisted living facilities. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 17 , 291 -298.

Kuhn, D., Ortigara, A., & Kasayka, R., ( 2000 ). Dementia Care Mapping: An innovative tool to measure person-centered care. Alzheimer's Care Quarterly, 1 , 7 -15.

Lawton, M. P., ( 1997 ). Assessing quality of life in Alzheimer's Disease research. Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders, 11 , 91 -99.

*Lintern, T., Woods, R., & Phair, L., ( 2000 ). Before and after training: A case study of intervention. Journal of Dementia Care, 8 , (1), 15 -17.

*Lintern, T., Woods, R., & Phair, L., ( 2000 ). Training is not enough to change care practice. Journal of Dementia Care, 8 , (2), 15 -17.

Logsdon, R. G., Gibbons, L. E., McCurry, S. M., & Teri, L., ( 2000 ). Quality of life in Alzheimer's disease: Patient and care giver reports. In S. Albert & R. G. Logsdon (Eds.), Assessing quality of life in Alzheimer's disease (pp. 17–30). New York: Springer.

*Maguire, S., & Gosling, A., ( 2003 ). Social and sensory stimulation groups: Do the benefits last? Journal of Dementia Care, 11 , (2), 20 -21.

*Martin, G., & Younger, D., ( 2000 ). Anti-oppressive practice: A route to the empowerment of people with dementia through communication and choice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 7 , 59 -67.

*Martin, G. W., & Younger, D., ( 2001 ). Person-centred care for people with dementia: A quality audit approach. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 8 , 443 -448.

McFayden, M., ( 1984 ). The measurement of engagement in institutionalised elderly. In I. Hanley & J. Hodge (Eds.), Psychological approaches to care of the elderly (pp. 136–163). London: Croom Helm.

McKee, K. J., Houston, D. M., & Barnes, S., ( 2002 ). Methods for assessing quality of life and well-being in frail older people. Psychology and Health, 17 , 737 -751.

*Parker, J., ( 1999 ). Education and learning for the evaluation of dementia care: The perceptions of social workers in training. Education and Ageing, 14 , 297 -314.

Pattie, A. H., & Gilleard, C. J., ( 1979 ). Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly (CAPE) . Sevenoaks, Kent, U.K.: Hodder & Stoughton.

*Perrin, T., ( 1997 ). Occupational need in severe dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25 , 934 -941.

*Potkins, D., Myint, P., Bannister, C., Tadros, G., Chithramohan, R., & Swann, A., et al ( 2003 ). Language impairment in dementia: Impact on symptoms and care needs in residential homes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18 , 1002 -1006.

*Pritchard, E. J., & Dewing, J., ( 2001 ). A multi-method evaluation of an independent dementia care service and its approach. Aging & Mental Health, 5 , 63 -72.

Rabins, P., Kasper, J. D., Kleinman, L., Black, B. S., & Patrick, D. L., ( 1999 ). Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 5 , 33 -48.

Ruesing, D., ( 2003 ). Die Reliabilitat und Validitat des Beobachtunginstruments: DCM [The reliability and validity of observational instruments: DCM]. Unpublished master's thesis, University of Witten Herdecke, Germany.

Surr, C., & Bonde-Nielsen, E., ( 2003 ). Inter-rater reliability in DCM. Journal of Dementia Care, 11 , (6), 33 -36.

*Thornton, A., Hatton, C., & Tatham, A., ( 2004 ). DCM reconsidered: Exploring the reliability and validity of the observational tool. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19 , 718 -726.

*Wilkinson, A. M., ( 1993 ). Dementia Care Mapping: A pilot study of its implementation in a psychogeriatric service. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 8 , 1027 -1029.

*Williams, J., & Rees, J., ( 1997 ). The use of ‘dementia care mapping’ as a method of evaluating care received by patients with dementia: An initiative to improve quality of life. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25 , 316 -323.

*Wylie, K., Madjar, I., & Walton, J., ( 2002 ). Dementia Care Mapping: A person-centered approach to improving the quality of care in residential settings. Geriaction, 20 , (2), 5 -9.

*Younger, D., & Martin, G., ( 2000 ). Dementia Care Mapping: An approach to quality audit of services for people with dementia in two health districts. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32 , 1206 -1212.

Email alerts

Citing articles via, looking for your next opportunity.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1758-5341

- Copyright © 2024 The Gerontological Society of America

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,861,927 articles, preprints and more)

- Available from publisher site using DOI. A subscription may be required. Full text

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Dementia care mapping: a review of the research literature.

Author information, affiliations.

- Brooker D 1

The Gerontologist , 01 Oct 2005 , 45 Spec No 1(1): 11-18 https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.11 PMID: 16230745

Abstract

Design and methods, implications, full text links .

Read article at publisher's site: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.11

References

Articles referenced by this article (43)

Kitwood's approach to dementia and dementia care: a critical but appreciative review.

J Adv Nurs, (5):948-953 1996

MED: 8732522

Quality of care in private sector and NHS facilities for people with dementia: cross sectional survey.

Ballard C , Fossey J , Chithramohan R , Howard R , Burns A , Thompson P , Tadros G , Fairbairn A

BMJ, (7310):426-427 2001

MED: 11520838

Title not supplied

AUTHOR UNKNOWN

Clin Psychol 2002

Can psychiatric liaison reduce neuroleptic use and reduce health service utilization for dementia patients residing in care facilities.

Ballard C , Powell I , James I , Reichelt K , Myint P , Potkins D , Bannister C , Lana M , Howard R , O'Brien J , Swann A , Robinson D , Shrimanker J , Barber R

Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, (2):140-145 2002

MED: 11813276

Clin Psychol 2004

JOURNAL OF DEMENTIA CARE 1995

A literature review of dementia care mapping: methodological considerations and efficacy.

Beavis D , Simpson S , Graham I

J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, (6):725-736 2002

MED: 12472826

PROFESSIONAL PSYCHOLOGY 1977

Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995

JOURNAL OF DEMENTIA CARE 2001

Citations & impact

Impact metrics, citations of article over time, alternative metrics.

Smart citations by scite.ai Smart citations by scite.ai include citation statements extracted from the full text of the citing article. The number of the statements may be higher than the number of citations provided by EuropePMC if one paper cites another multiple times or lower if scite has not yet processed some of the citing articles. Explore citation contexts and check if this article has been supported or disputed. https://scite.ai/reports/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.11

Article citations, iatrogenic suffering at the end of life: an ethnographic study..

Green L , Capstick A , Oyebode J

Palliat Med , 37(7):984-992, 23 Apr 2023

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 37088974 | PMCID: PMC10320702

Effects of the use of autobiographical photographs on emotional induction in older adults: a systematic review.

Toledano-González A , Romero-Ayuso D , Fernández-Pérez D , Nieto M , Ricarte JJ , Navarro-Bravo B , Ros L , Latorre JM

Psychol Res , 87(4):988-1011, 20 Jul 2022

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 35859072

Assessing Momentary Well-Being in People Living With Dementia: A Systematic Review of Observational Instruments.

Madsø KG , Flo-Groeneboom E , Pachana NA , Nordhus IH

Front Psychol , 12:742510, 23 Nov 2021

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 34887803 | PMCID: PMC8649635

Known in the nursing home: development and evaluation of a digital person-centered artistic photo-activity intervention to promote social interaction between residents with dementia, and their formal and informal carers.

Tan JRO , Boersma P , Ettema TP , Aëgerter L , Gobbens R , Stek ML , Dröes RM

BMC Geriatr , 22(1):25, 06 Jan 2022

Cited by: 2 articles | PMID: 34991472 | PMCID: PMC8733433

Person-Centred Care Transformation in a Nursing Home for Residents with Dementia.

Ho P , Cheong RCY , Ong SP , Fusek C , Wee SL , Yap PLK

Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra , 11(1):1-9, 01 Jan 2021

Cited by: 3 articles | PMID: 33790933 | PMCID: PMC7989831

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

An examination of the psychometric properties and efficacy of Dementia Care Mapping.

Cooke HA , Chaudhury H

Dementia (London) , 12(6):790-805, 21 May 2012

Cited by: 10 articles | PMID: 24337640

Implementing Dementia Care Mapping as a practice development tool in dementia care services: a systematic review.

Surr CA , Griffiths AW , Kelley R

Clin Interv Aging , 13:165-177, 26 Jan 2018

Cited by: 8 articles | PMID: 29416325 | PMCID: PMC5790091

J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs , 9(6):725-736, 01 Dec 2002

Cited by: 30 articles | PMID: 12472826

Dementia Care Mapping as a research tool for measuring quality of life in care settings: psychometric properties.

Fossey J , Lee L , Ballard C

Int J Geriatr Psychiatry , 17(11):1064-1070, 01 Nov 2002

Cited by: 61 articles | PMID: 12404656

Dementia Care Mapping reconsidered: exploring the reliability and validity of the observational tool.

Thornton A , Hatton C , Tatham A

Int J Geriatr Psychiatry , 19(8):718-726, 01 Aug 2004

Cited by: 17 articles | PMID: 15290694

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Dementia care mapping: a review of the research literature

Affiliation.

- 1 Bradford Dementia Group, School of Health Studies, University of Bradford, Unity Building, Bradford, Yorkshire BD5 0BB, UK. [email protected]

- PMID: 16230745

- DOI: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.11

Purpose: The published literature on dementia care mapping (DCM) in improving quality of life and quality of care through practice development and research dates back to 1993. The purpose of this review of the research literature is to answer some key questions about the nature of the tool and its efficacy, to inform the ongoing revision of the tool, and to set an agenda for future research.

Design and methods: The DCM bibliographic database at the University of Bradford in the United Kingdom contains all publications known on DCM (http://www.bradford.ac.uk/acad/health/dcm). This formed the basis of the review. Texts that specifically examined the efficacy of DCM or in which DCM was used as a main measure in the evaluation or research were reviewed.

Results: Thirty-four papers were categorized into five main types: (a) cross-sectional surveys, (b) evaluations of interventions, (c) practice development evaluations, (d) multimethod evaluations, and (e) papers investigating the psychometric properties of DCM.

Implications: These publications provide some evidence regarding the efficacy of DCM, issues of validity and reliability, and its use in practice and research. The need for further development and research in a number of key areas is highlighted.

Publication types

- Dementia / therapy*

- Quality of Health Care*

- Quality of Life*

- User Support Information

- Browse by Year

- Browse by Subject

- Browse by Division

- Browse by Author

- Simple Search

- Advanced Search

Actions (login required)

Assessing Culturally Tailored Dementia Interventions to Support Informal Caregivers of People Living with Dementia (PLWD): A Scoping Review

- Published: 28 March 2024

Cite this article

- Araya Dimtsu Assfaw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2163-0338 1 ,

- Kerstin M. Reinschmidt 2 ,

- Thomas A. Teasdale 2 ,

- Lancer Stephens 3 ,

- Keith L. Kleszynski 4 &

- Kathleen Dwyer 5

28 Accesses

Explore all metrics

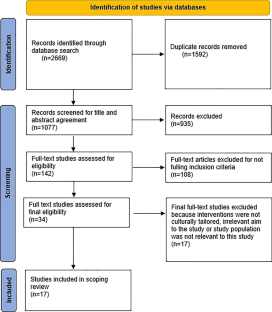

The review aimed to identify and describe dementia care interventions and programs that are culturally tailored to support racial and ethnic minority informal caregivers of community-dwelling people living with dementia (PLWD) to identify gaps in need. Culturally targeted interventions to support vulnerable minority informal caregivers are important in addressing the care needs of PLWD and eliminating racial and ethnic dementia disparities. Nevertheless, little is known about the existing interventions and programs that are culturally tailored to support racial and ethnic minority groups, in particular, African-American caregivers in the care of their family members. We conducted a Scoping review, searching eight databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, APA PsycINFO, CINAHL, PUBMED, Scopus, and Web of Science between January 2012 and June 2022. Our search identified 2669 records, of which 17 articles were included in the analysis. The review addressed how these interventions have been developed to meet the needs and preferences of minority caregivers, particularly, African-American caregivers in culturally responsive ways. Findings show that culturally tailored interventions have the potential to improve the caregiving ability of informal caregivers. Supporting informal caregivers appears to be an effective strategy often improving the well-being of PLWD and reducing caregiver burden. The review demonstrates the paucity and diversity of research on culturally tailored dementia interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities. This scoping review identified gaps in the existing literature and aims for future work to develop and investigate cultural tailoring of interventions.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Barriers and facilitators in accessing dementia care by ethnic minority groups: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies.

Cassandra Kenning, Gavin Daker-White, … Waquas Waheed

Language and Culture in the Caregiving of People with Dementia in Care Homes - What Are the Implications for Well-Being? A Scoping Review with a Welsh Perspective

Conor Martin, Bob Woods & Siôn Williams

Dementia and migration: culturally sensitive healthcare services and projects in Germany

Jessica Monsees, Sümeyra Öztürk & Jochen René Thyrian

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

2021 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(3):327–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12328 .

2022 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(4):700–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12638 .

What is Alzheimer’s Disease? | CDC. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/aginginfo/alzheimers.htm .

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2019;15(3):321–87.

Skufca, L. AARP family caregiving survey: Caregivers’ reflections on changing roles. AARP Research. 2017;10.

2020 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12068 .

Gallagher-Thompson D, Haley W, Guy D, Rupert M, Argüelles T, Zeiss LM, Long C, Tennstedt S, Ory M. Tailoring psychological interventions for ethnically diverse dementia caregivers. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2003;10:423–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg042 .

Cooper C, Tandy AR, Balamurali TB, Livingston G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in use of dementia treatment, care, and research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):193–203.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Babulal GM, Quiroz YT, Albensi BC, Arenaza-Urquijo E, Astell AJ, Babiloni C, Bahar-Fuchs A, Bell J, Bowman GL, Brickman AM, Chételat G, Ciro C, Cohen AD, Dilworth-Anderson P, Dodge HH, Dreux S, Edland S, Esbensen A, Evered L, Ewers M., … International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment, Alzheimer’s Association. Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimers Dement : J Alzheimers Assoc. 2019;15(2):292–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.09.009

Fabius CD, Wolff JL, Kasper JD. Race differences in characteristics and experiences of black and white caregivers of older Americans. Gerontologist. 2020;60(7):1244–53.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rainville C, Skufca L, Mehegan L. Family caregiving and out-of-pocket costs: 2016 report. African American RP Public Policy Institute; 2016.

Google Scholar

Hughes TB, Black BS, Albert M, Gitlin LN, Johnson DM, Lyketsos CG, Samus QM. Correlates of objective and subjective measures of caregiver burden among dementia caregivers: influence of unmet patient and caregiver dementia-related care needs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1875–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610214001240 .

Darnell KR, McGuire C, Danner DD. African American participation in Alzheimer’s disease research that includes brain donation. Am J Alzheimers Dis Dement®. 2011;26(6):469–76.

Article Google Scholar

Armstrong TD, Crum LD, Rieger RH, Bennett TA, Edwards LJ. Attitudes of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(3):552–74.

Portacolone E, Palmer NR, Lichtenberg P, Waters CM, Hill CV, Keiser S, Vest L, Maloof M, Tran T, Martinez P, Guerrero J, Johnson JK. Earning the trust of African American communities to increase representation in dementia research. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(Suppl 2):719–34. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.30.S2.719 .

Dimtsu Assfaw, A., Reinschmidt, K. M., Teasdale, T. A., Stephens, L., Kleszynski, K. L., & Dwyer, K. Describing providers' perspectives on the needs and challenges of family caregivers of African American people living with dementia. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2023;1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2023.2299486 .

McCarron HR, Wright A, Moone RP, Toomey T, Osypuk TL, Shippee T. Assets and unmet needs of diverse older adults: Perspectives of community-based service providers in Minnesota. J Health Disparities Res Pract. 2020;13(1):6.

Barnes LL. Alzheimer disease in African American individuals: increased incidence or not enough data? Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18(1):56–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00589-3 .

Burgdorf JG, Amjad H. Impact of diagnosed (vs undiagnosed) dementia on family caregiving experiences. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(4):1236–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18155 .

Lathren CR, Sloane PD, Hoyle JD, Zimmerman S, Kaufer DI. Improving dementia diagnosis and management in primary care: a cohort study of the impact of a training and support program on physician competency, practice patterns, and community linkages. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13(1):1–7.

Byers MD, Resciniti NV, Ureña S, Leith K, Brown MJ, Lampe NM, Friedman DB. An evaluation of Dementia Dialogues®: a program for informal and formal caregivers in North and South Carolina. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(1):82–91.

Glueckauf RL. Telephone-mediated, faith-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for depressed African-American dementia caregivers [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting, American Psychological Association, Toronto, Canada; 2015.

Glueckauf RL, Davis WS, Allen K, Chipi P, Schettini G, Tegen L, Jian X, Gustafson DJ, Maze J, Mosser B, Prescott S, Robinson F, Short C, Ticket S, VanMatre J, DiGeronimo T, Ramirez C. Integrative cognitive-behavioral and spiritual counseling for rural dementia caregivers with depression. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54(4):449–61.

Lampe NM, Desai N, Norton-Brown T, Nowakowski AC, Glueckauf RL. African-American lay pastoral care facilitators’ perspectives on dementia caregiver education and training. Qual Rep. 2022;27(2):324–39.

Joo JY. Effectiveness of culturally tailored diabetes interventions for Asian immigrants to the United States: a systematic review. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(5):605–15.

Brijnath B, Croy S, Sabates J, Thodis A, Ellis S, de Crespigny F, Moxey A, Day R, Dobson A, Elliott C, Etherington C, Geronimo MA, Hlis D, Lampit A, Low LF, Straiton N, Temple J. Including ethnic minorities in dementia research: Recommendations from a scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12222. https://doi.org/10.1002/trc2.12222 .

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Khalil H, Larsen P, Marnie C, Pollock D, Tricco AC, Munn Z. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid Synth. 2022;20(4):953–68. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-21-00242 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Le CT, Lee JA. Home visit based mindfulness intervention for Vietnamese American dementia family caregivers: a pilot feasibility study. Asia Pac Island Nurs J. 2021;5(4):207.

Bergeron CD, Robinson MT, Willis FB, Albertie ML, Wainwright JD, Fudge MR, Parfitt FC, Crook JE, Ball CT, Lucas JA. Testing an Alzheimer's disease educational approach in two African American neighborhoods in Florida. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(6):2283–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01165-7 .

Goeman D, King J, Koch S. Development of a model of dementia support and pathway for culturally and linguistically diverse communities using co-creation and participatory action research. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e013064.

Lee JA, Nguyen H, Park J, Tran L, Nguyen T, Huynh Y. Usages of computers and smartphones to develop dementia care education program for Asian American family caregivers. Healthc Informat Res. 2017;23(4):338–42.

Han HR, Choi S, Wang J, Lee HB. Pilot testing of a dementia literacy intervention for Korean American elders with dementia and their caregivers. J Clin Transl Res. 2021;7(6):712.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chua J, Pachana NA. Use of a psychoeducational skill training DVD program to reduce stress in Chinese Australian and Singaporean dementia caregivers: a pilot study. Clin Gerontol. 2016;39(1):3–14.

Browne CV, Muneoka S, Ka'opua LS, Wu YY, Burrage RL, Lee YJ, Mokuau NK, Braun KL. Developing a culturally responsive dementia storybook with Native Hawaiian youth. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2022;43(3):315–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2021.1885398 .

Chi I, Liu M, Wang S. Developing the Asian Pacific islander caregiver train-the-trainer program in the United States. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2020;29(6):490–507.

Lincoln KD, Chow TW, Gaines BF. BrainWorks: a comparative effectiveness trial to examine Alzheimer’s disease education for community-dwelling African Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(1):53–61.

Wang Y, Xiao LD, Yu Y, Huang R, You H, Liu M. An individualized telephone-based care support program for rural family caregivers of people with dementia: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):1–11.

Dunn DJ, Schwartz A, Teufel-Shone NI, Meyer LA. Educational program to promote resilience for caregivers, family members, and community members in the care of elderly Native Americans who are experiencing memory loss and cognitive decline. Visions: J Rogerian Nurs Sci. 2019;25(2).

Epps F, Moore M, Chester M, Gore J, Sainz M, Adkins A, Clevenger C, Aycock D. The Alter program: a nurse-led, dementia-friendly program for African American faith communities and families living with dementia. Nurs Adm Q. 2022;46(1):72–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000506 .

Richardson RC, Sistler AB. The well-being of elderly black caregivers and noncaregivers: a preliminary study. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1999;31(1–2):109–17.

Lampe NM, Desai N, Norton-Brown T, Nowakowski AC, Glueckauf RL. African American lay pastoral care facilitators’ perspectives on dementia caregiver education and training. Qual Rep. 2022;27(2):324–39.

Czaja SJ, Lee CC, Perdomo D, Loewenstein D, Bravo M, Moxley PhD, J. H., & Schulz, R. Community REACH: an implementation of an evidence-based caregiver program. Gerontologist. 2018;58(2):e130–7.

Levy-Storms L, Cherry DL, Lee LJ, Wolf SM. Reducing safety risk among underserved caregivers with an Alzheimer’s home safety program. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(9):902–9.

Napoles AM, Chadiha L, Eversley R, Moreno-John G. Reviews: developing culturally sensitive dementia caregiver interventions: are we there yet? Am J Alzheimers Dis Dement. 2010;25(5):389–406.

Jones I. Social class, dementia and the fourth age. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39(2):303–17.

Sidani S, Ibrahim S, Lok J, Fan L, Fox M, Guruge S. An integrated strategy for the cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions. Health. 2017;9(04):738.

Berwald S, Roche M, Adelman S, Mukadam N, Livingston G. Black African and Caribbean British Communities’ perceptions of memory problems: “We don’t do dementia.” PloS one. 2016;11(4):e0151878.

Lynch CP, Williams JS, J Ruggiero K, G Knapp R, Egede LE. Tablet-aided behavioral intervention effect on self-management skills (TABLETS) for diabetes. Trials. 2016;17:157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1243-2 .

Chandler J, Sox L, Kellam K, Feder L, Nemeth L, Treiber F. Impact of a culturally tailored mHealth medication regimen self-management program upon blood pressure among hypertensive Hispanic adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(7):1226.

Joseph RP, Keller C, Adams MA, Ainsworth BE. Print versus a culturally-relevant Facebook and text message delivered intervention to promote physical activity in African American women: a randomized pilot trial. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):1–18.

Lucero RJ, Fehlberg EA, Patel AGM, Bjarnardottir RI, Williams R, Lee K, Ansell M, Bakken S, Luchsinger JA, Mittelman M. The effects of information and communication technologies on informal caregivers of persons living with dementia: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;5:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2018.11.003.PMC6315277 .

Adewuya AO, Momodu O, Olibamoyo O, Adegbaju A, Adesoji O, Adegbokun A. The effectiveness and acceptability of mobile telephone adherence support for management of depression in the Mental Health in Primary Care (MeHPriC) project, Lagos, Nigeria: a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2019;253:118–25.

Epps F, Alexander K, Brewster GS, Parker LJ, Chester M, Tomlinson A, Adkins A, Zingg S, Thornton J. Promoting dementia awareness in African‐American faith communities. Publ Health Nurs. 2020;37(5):715–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12759 .

Epps F, Foster K, Alexander K, Brewster G, Chester M, Thornton J, Aycock D. Perceptions and attitudes toward dementia in predominantly African American congregants. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(11):1511–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820987350 .

Su D, Garg A, Wiens J, Meyer E, Cai G. Assessing health needs in African American churches: a mixed methods study. J Relig Health. 2021;60(2):1179–97.

Williams LF, Cousin L. “A charge to keep I have”: black pastors’ perceptions of their influence on health behaviors and outcomes in their churches and communities. J Relig Health. 2021;60(2):1069–82.

James T, Mukadam N, Sommerlad A, Ceballos SG, Livingston G. Culturally tailored therapeutic interventions for people affected by dementia: a systematic review and new conceptual model. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(3):e171–9.

Abramson CM, Hashemi M, Sánchez-Jankowski M. Perceived discrimination in US healthcare: charting the effects of key social characteristics within and across racial groups. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:615–21.

McDaniel M, Richardson A, Gonzalez D, Caraveo CA, Wagner L, Skopec L. Black and African American adults’ perspectives on discrimination and unfair judgment in health care. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2021.

Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK. African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: healthcare for diverse populations. J Cultural Divers. 2007;14(2), 56–60.

Hammonds EM, Reverby SM. Toward a historically informed analysis of racial health disparities since 1619. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1348–9.

Jones C, Jablonski RA. “I don’t want to be a guinea pig”: recruiting older African Americans. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(3):3–4.

Joo JY, Liu MF. Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: a scoping review. Nurs Open. 2021;8(5):2078–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.733 .

Joyce KE, Cartwright N. Bridging the gap between research and practice: predicting what will work locally. Am Educ Res J. 2020;57(3):1045–82.

Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Duran B, Magarati M, Pearson C, Belone L, Davis J, DeWindt L, Kastelic S, Lucero J, Ruddock C, Sutter E, Dutta MJ. Culture-centeredness in community-based participatory research: contributions to health education intervention research. Health Educ Res. 2019;34(4):372–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyz021 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Sheryl Lynn Hamilton of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Robert M Bird Health Sciences Library for her assistance in the search strategy process.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology- Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Araya Dimtsu Assfaw

Hudson College of Public Health, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA

Kerstin M. Reinschmidt & Thomas A. Teasdale

Hudson College of Public Health & Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Research Center, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA

Lancer Stephens

Department of Medicine, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA

Keith L. Kleszynski

Fran and Earl Ziegler College of Nursing, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA

Kathleen Dwyer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The first author, Araya Dimtsu Assfaw, performed material preparation, data collection, and analysis. All authors commented on the previous version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Araya Dimtsu Assfaw .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

This is a review study and does not involve the voluntary participation of human subjects. Therefore, no ethical approval is required.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Assfaw, A.D., Reinschmidt, K.M., Teasdale, T.A. et al. Assessing Culturally Tailored Dementia Interventions to Support Informal Caregivers of People Living with Dementia (PLWD): A Scoping Review. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-01985-3

Download citation

Received : 19 September 2023

Revised : 13 March 2024

Accepted : 17 March 2024

Published : 28 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-01985-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cultural tailoring

- Ethnic minority

- African-Americans

- Health disparities

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Geriatr

Dissemination and implementation research in dementia care: a systematic scoping review and evidence map

Ilianna lourida.

1 NIHR CLAHRC South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC), University of Exeter Medical School, University of Exeter, South Cloisters, St Luke’s Campus, Exeter, EX1 2LU UK

Rebecca A Abbott

Morwenna rogers, iain a lang, bridie kent.

2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK

Jo Thompson Coon

Associated data.

A list of the reviewed studies supporting our findings and on which the conclusions of the manuscript rely can be found in Additional files, Additional file 5 .

The need to better understand implementing evidence-informed dementia care has been recognised in multiple priority-setting partnerships. The aim of this scoping review was to give an overview of the state of the evidence on implementation and dissemination of dementia care, and create a systematic evidence map.