Ragged Dick: Or, Street Life in New York with the Boot Blacks

Horatio alger, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

| Theme Analysis |

Horatio Alger didn’t coin the adage, “dress for the job you want, not the one you have,” but he certainly believed in it. Clothes are incredibly important in Ragged Dick , a story whose titular fourteen-year-old orphan shines shoes on the streets of New York. In the book, those who wear nice clothes and take care of their appearance, are successful, where those with little care for their apparel, or whose clothing is ill-fitted or worn, are presented as lazy—and thus bound to remain in poverty. This is more than just a reflection of class values or even the late-nineteenth-century obsession with clothing; Alger suggests that the clothes literally make the man. Even a simple upgrade in one’s wardrobe, then, is capable of changing a person and being a springboard into a new life of social respectability and economic prosperity.

Dick ’s new suit —presented to him by Frank Whitney before the two begin their sight-seeing tour—doesn’t just change the way he looks; it changes the way he feels about his life. After seeing himself in the new suit, he realizes how dirty and worthless he looks in his former vagabond clothes and is unwilling to return to them. With this realization comes adjacent ones, like the understanding that he doesn’t want to eat breakfast, or live at, at the same places where boys in vagabond clothes do. It’s not that Dick feels as though he’s suddenly better than these boys. Rather, he feels as though he’s been awakened to a new way of life, one that has shown him who he is capable of becoming. The other boys could be awakened to their potential, too, if they only had the right clothes. In this way, the suit has alienated Dick from his previous existence. He no longer feels like he can be a part of that life, and instead begins making plans for a new one—one better fitting a boy in a nice suit.

A similar transformation happens to Dick’s friend Fosdick when Dick helps him to purchase a new set of clothes. Fosdick always suspected that he was cut out to be more than a shoeshine boy. Indeed, he expected—because Fosdick had been groomed for college by his father, prior to his untimely death—that he would attend college and live a comfortable life. However, as his deteriorating circumstances forced him into the ragged clothes of a bootblack (someone who shines shoes), his vision for that life began to dim. While Dick’s friendship, coupled with the room and board that Dick provides the boy, give Fosdick a better life, his outlook isn’t improved until Dick buys him a suit. Once adorned in the trappings of a successful young man, however, Fosdick again believes that he can be one—and instantly finds the courage to look for a better job.

Almost as a testament to their figurative statuses in Ragged Dick , neither of the boys’ suits appear susceptible to wear and tear—despite the hard use that the shoeshine boys surely put them to. Both boys own only a single suit, which they wear daily during their long outdoor shifts. Besides the obvious, damaging exposure to the weather, the boys’ work consists of a constant bending down to shine shoes, which would wear the garments out, and a constant exposure to shoe polish itself, which would easily stain them. Indeed, this hard work is precisely the reason that the boys’ former clothes are so dirty, tattered, and generally out of order. Yet the suits are resilient—a testament to the fact that they are more than mere clothes and are, instead, enduring symbols of the boys’ newfound path towards a more respectable life.

It’s no wonder, then, that Dick and Fosdick putting on suits cause such anger in people like the street urchin Micky Maguire , who tries to hurt Dick when he sees him wearing fancy new clothes. Though Micky believes that Dick is “putting on airs” through his sartorial choices, the reality is quite different. Through his clothes, Dick has already taken the first step down the path to a better life. This new life is one that Micky, whose clothes are of the same vagabond sort as Dick’s were previously, will never have access to—not because he doesn’t own a suit, but because he doesn’t want to own one. He is, instead, quite happy to wear tattered hand-me-downs, including Dick’s original clothes, which Maguire steals by story’s end. At that time, Maguire had a chance to steal Dick’s better clothing, as well, but—happy with his station in life—had no desire to do so. Clothes, then, are yet another testament to Dick’s pluck and industrious nature.

Clothes Make the Man ThemeTracker

Clothes Make the Man Quotes in Ragged Dick: Or, Street Life in New York with the Boot Blacks

Another of Dick's faults was his extravagance. Being always wide-awake and ready for business, he earned enough to have supported him comfortably and respectably. There were not a few young clerks who employed Dick from time to time in his professional capacity, who scarcely earned as much as he, greatly as their style and dress exceeded his. But Dick was careless of his earnings.

“I’m afraid you haven’t washed your face this morning,” said Mr. Whitney […]

“They didn’t have no wash-bowls at the hotel where I stopped,” said Dick.

“What hotel did you stop at?”

“The Box Hotel.” “The Box Hotel?” “Yes, sir, I slept in a box on Spruce Street.”

When Dick was dressed in his new attire, with his face and hands clean, and his hair brushed, it was difficult to imagine that he was the same boy.

Dick succeeded in getting quite a neat-looking cap, which corresponded much better with his appearance than the one he had on. The last, not being considered worth keeping, Dick dropped on the sidewalk, from which, on looking back, he saw it picked up by a brother boot-black who appeared to consider it better than his own.

Turning towards our hero, he said, “May I inquire, young man, whether you are largely invested in the Erie Railroad?”

“Did you ever read the Bible?” asked Frank, who had some idea of the neglected state of Dick’s education. “No,” said Dick. “I’ve heard it’s a good book, but I never read one. I ain’t much on readin’. It makes my head ache.”

“Some boys is born with a silver spoon in their mouth. Victoria’s boys is born with a gold spoon, set with di’monds; but gold and silver was scarce when I was born, and mine was pewter.”

“I know his game,” whispered Dick. “Come along and you’ll see what it is.”

I ain’t got no mother. She died when I wasn’t but three years old. My father went to sea; but he went off before mother died, and nothin’ was ever heard of him. I expect he got wrecked, or died at sea.

There isn’t but one thing to do. Just give me back that money, and I’ll see that you’re not touched. If you don’t, I’ll give you up to the first p’liceman we meet.

Save your money, my lad, buy books, and determine to be somebody, and you may yet fill an honorable position.

Mr. Henderson, this is a member of my Sunday school class, for whose good qualities and good abilities I can speak confidently.

Dick read this letter with much satisfaction. It is always pleasant to be remembered, and Dick had so few friends that it was more to him than to boys who are better provided. Again, he felt a new sense of importance in having a letter addressed to him. It was the first letter he had ever received. If it had been sent to him a year before, he would not have been able to read it. But now, thanks to Fosdick's instructions, he could not only read writing, but he could write a very good hand himself.

I've give up sleepin' in boxes, and old wagons, findin' it didn't agree with my constitution. I've hired a room in Mott Street, and have got a private tooter,

who rooms with me and looks after my studies in the evenin'. Mott Street ain't very fashionable; but my manshun on Fifth Avenoo isn't finished yet, and I'm afraid it won't be till I'm a gray-haired veteran. I've got a hundred dollars towards it, which I've saved from my earnin's. I haven't forgot what you and your uncle said to me, and I'm trying to grow up 'spectable.

“…you were ‘Ragged Dick.’ You must drop that name, and think of yourself now as—”

“Richard Hunter, Esq.” said our hero, smiling.

“A young gentleman on the way to fame and fortune,” added Fosdick.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to quick search

- Skip to global navigation

Ars Orientalis

Clothes make the man.

- Volume 47 | Permalink

- Print article

- Download PDF 5.6mb

A few decades later, for example, the Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens made a drawing of a man in Korean dress (fig. 2). A detailed and meticulous rendering, the work is not necessarily accurate in all of its elements, [4] but it demonstrates a fascination with the exotic and distant—particularly intriguing in this case because there was little direct contact between Northern Europe and Korea in the early seventeenth century.

Europeans were not alone in their fascination with dress. Engagement with matters of dress on the part of various Asian peoples prior to modern times is a significant thread running through the papers in this volume. In work focusing on objects as diverse as embroidered cotton capes made in Bengal for a European market (Karl), cotton garments worn at the Mughal court (Houghteling), and inscribed silk bands used in Īlkḫānid courtly garments (Mühlemann), the articles here demonstrate clearly that the region was home to a sophisticated, nuanced, and culturally specific understanding of the communicative value of textiles and clothing.

A full account of the ways in which people across Asia engaged with dress in the medieval and early modern periods is beyond the scope of a brief introduction, but a few examples—apart from those addressed in the volume’s articles—can be mentioned here. A particularly important example of contemporary interest in matters of style and dress from the tenth-century Islamic world is provided by a book called On Elegance and Elegant People ( Kitab al-zarf wa’l-zurafa’ ), by Abu l-Tayyib Muhammed al-Washsha. [5] The author writes about contemporary dress, perfumes, and acceptable social behavior, describes differences between clothing for men and for women, and generally provides a guide to behavior for the elite of the Abbasid empire. For the early modern Ottoman Empire, the dress of court members, foreign emissaries, military figures, and people in the street is detailed in historical paintings by court artists, with single-page paintings of fashionable women becoming particularly popular in the eighteenth century (fig. 3).

For China, as for Korea, there is an abundance of written documentation concerning dress—particularly official dress, which was an important aspect of court culture—and the careful observance of clothing standards (which varied according to class and status) was considered essential to maintaining stability. In addition to official records, literature (both poetry and novels) provides information about the clothing of other groups of people. One such example is the Honglou Meng , or A Dream of the Red Mansion , in which a young woman from a well-off Han family enters the imperial harem. The novel includes descriptions of the dress and accessories that become part of her new life. [6]

With the passage of time, the first European costume books evolved into more comprehensive explorations, and gradually the field of costume studies took shape. Important early examples of European studies of costume include Costumes historiques des XVIe, XVIIe, et XVIIIe siècles by Georges Duplessis, published in 1867, and Auguste Racinet’s Le costume historique , published in 1888. Learned societies for the study of costume—such as the Société de l’Histoire du Costume, established in France in 1907—were formed in the early twentieth century.

The field of costume studies has been particularly robust in Great Britain, which is home to remarkable collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum, local collections at innumerable smaller museums (foremost among them the Fashion Museum in Bath), and the flagship academic program for the study of dress (at the Courtauld Institute, founded in 1965). Prominent among British academic achievements in costume studies are mid-century foundational works by James Laver, Quentin Bell, Stella Mary Newton, Anne Buck, and others. The Costume Society was formed in 1964 and began publishing its journal, Costume , a year later. Similar scholarly organizations were founded in other countries at around the same time, with important collections of dress established at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute as well as the Musée du Louvre and the Musée Galliera in Paris, to mention only a few. In more recent decades, costume studies have been enriched by an engagement with new theoretical and methodological models, and the field has become increasingly interdisciplinary. Post-colonialism, gender studies, consumption studies, global art history, the material turn—all have influenced the ways in which scholars of dress approach their work. Increased attention to the theoretical across the field was signaled by the founding of the journal Fashion Theory , under the direction of Valerie Steele, in 1997; today there exists a rich and diverse bibliography in the study of dress/costume/fashion. [7]

In Asia, as in Europe and America, research on dress takes place in a variety of university and museum contexts. Historians of dress may be engaged in departments and programs from fashion design to anthropology, home economics, industrial design, and art history. At Seoul National University, for example, the Department of Textiles, Merchandising, and Fashion Design is in the College of Human Ecology. The Fashion Design program at Ewha Women’s University, also in Seoul, is now in the College of Art and Design, having been part of the Division of Decorative Art when it was formed in 1967. The Bunka Fashion College, today one of the most important fashion education institutions in East Asia, had its beginnings in 1919 as dressmaking school for women, established in a Tokyo dressmaking shop. While many programs, such as those of the Bunka Fashion College, are well established, others are more recent. In Beirut, the Lebanese American University has created a new program in Fashion Design (including costume history), initiated in collaboration with the London College of Fashion. The program is housed in the School of Architecture and Design, and its first undergraduates entered in 2013. [8]

Scholars based in museums, universities, and technical institutes across Asia and the Middle East are making important contributions to the field in a range of languages. International academic organizations and conferences bring scholars together on a regular basis, allowing a level of exchange that would not have been possible even forty years ago. Recent years have seen the publication of surveys and basic introductory texts on the history of dress in Asia that provide well-informed and seriously researched accounts for the scholar and for interested members of the public alike. Foremost among these is the Berg Encylopedia of World Dress and Fashion (reviewed in Ars Orientalis ’s Digital Initiatives), which exists in both print and online versions. Published first in 2010 and continually updated, it contains hundreds of articles about costume history and fashion across Asia, written by scholars based both in the region and outside of it. Asia is covered in three volumes, Volume 4: South Asia and Southeast Asia, Volume 5: Central and Southwest Asia, and Volume 6: East Asia, edited by distinguished scholars Jasleen Dhamija, Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, and John E. Vollmer, respectively.

Across the Middle East and Asia we also find a number of significant collections for the study of both traditional and contemporary dress; some have long histories, others are more recent. As the great costume collections in Europe were being assembled in the late nineteenth century, attention also was being given to important collections of dress in Asia, particularly in the context of royal courts. As early as 1846, costumes of the Ottoman Janissaries (a former military order) were displayed in an exhibition space created in the Church of Hagia Irene in Istanbul. A few decades later, a more elaborate display of the costumes of the Ottoman sultans was created in the Treasury building of the Topkapı Palace. [9] Permission was required to visit, but travelers’ accounts suggest that such permission was not difficult to obtain. Today, the stunning collection of costumes of the Ottoman sultans and the royal family in the Topkapı Sarayı Museum, although exhibited infrequently, is the subject of ongoing research. The Sadberk Hanım Museum, a private institution north of Istanbul, also holds an important collection of Turkish dress, and smaller museums across the country feature collections of dress, usually displayed in galleries devoted to ethnography.

With its rich tradition of textile production, India is home to important museum collections of textiles and dress, particularly the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, formerly the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India, in Mumbai. Founded in 1905, the museum opened a new gallery of textiles and costume in 2015 to display their extensive holdings. A tour of the galleries is available on Google Cultural Institute. [10] The Calico Museum of Textiles in Ahmedabad—founded in 1949, inaugurated by Jahaharlal Nehru, and now managed by the Sarabhai Foundation—occupies historic buildings with innovative exhibitions dedicated to a stunning collection of court and local dress, export textiles, furnishing textiles, tents, and carpets.

In the past two decades, China has seen an explosion in the creation of new museums, some of which are devoted to dress or display significant collections of such. Among these are the Beijing National Costume Museum, founded in 2000, and the Shanghai Museum of Textiles and Costume on the campus of Donghua University, which opened to the public in 2009. The China National Silk Museum in Hangzhou, home to extensive collections of historical textiles and costumes, as well as conservation labs and research facilities, is an internationally known center for the study of sericulture and Chinese textile history.

The Kyoto Costume Institute, founded in 1978, is devoted to the study of Western dress. It holds extensive collections, has developed an impressive digital presence, and has published a series of important exhibition catalogues. A research center, the institute lacks exhibition space (apart from one small gallery) and thus works in partnership with museums around the globe to present exhibitions. Another important institution for the history of dress in Japan is the Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum, which is part of the Bunka Fashion College. Founded in 1979, the museum began with a study collection for students—focusing on early examples of westernized dress in Japan, European garments, and kimono—but has gradually expanded to include garments from all regions of the world.

Korea has an extensive network of museums, a number of which hold significant collections of dress, mostly drawn from Korean costume traditions. Foremost among these are the National Palace Museum of Korea—which houses court artifacts, including a rich costume collection, as well as extensive archives—and the National Museum of Korea, both in Seoul. Clothing from outside the court is preserved in the National Folk Museum. Other important collections may be found in museums associated with universities or colleges that have long histories of teaching dressmaking in the twentieth century, fashion design, and costume history.

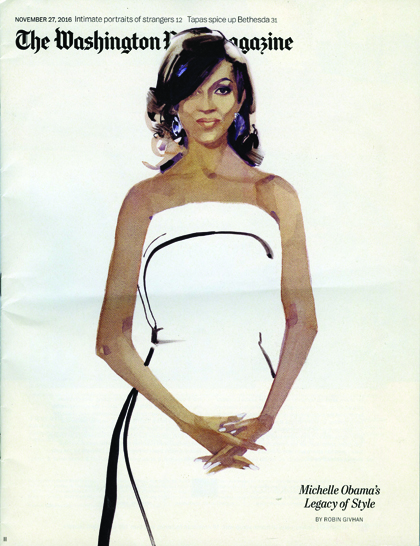

Dress intersects with everyday life in a way that few other areas of art history do: we all participate in the fashion economy through the purchase and wearing of clothes, and even the most unworldly among us understands the sharp distinction in impression created by jeans and a T-shirt versus a well-pressed suit. This intersection with the quotidian, and with popular culture, creates opportunities for the scholar of dress everywhere: in the blockbuster exhibitions at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art each summer, in heated debates in the press about girls’ rights to wear hijab in school or while competing in sports, and in popular analyses of the fashion strategies adopted by public figures—for example, the November 2016 cover story about Michelle Obama’s style in The Washington Post Magazine (fig. 4.) The ubiquity of fashion means that popular interest fuels the creation of large-scale collections of images and information, such as the Google Cultural Institute’s “We Wear Culture” project, launched while this volume was in production (reviewed in Digital Initiatives). Public engagement with (some aspects of) dress provides the opportunity for scholars to share with a much larger audience than we typically expect insights about the role of dress in constructing social identity, in maintaining or challenging social norms, and in shaping a global economy.

Noticing a significant uptick in the number of panels on dress at academic conferences, the editors determined that a volume of Ars Orientalis devoted to “New Research on Dress across Asia” would find an enthusiastic audience. We put out a call for papers in 2015 and received an astonishing number of submissions. They ran the gamut from studies on dress in ancient China to explorations of contemporary dress in Oman, and each provided an excellent look at one slice of current work in this very broadly defined field. We were spoiled for choice in creating the volume, and in making the article selections we looked for a balance of region, time period, research focus, and methodology. Thus, we are pleased to include here eleven articles that range from those based primarily on textual sources to those that explore archaeological remains, ethnographic work, and trade goods, stretching across Asia, from Egypt to Japan. It goes without saying that we received many fine submissions that, for reasons of space, could not be included in this volume.

As a group, these eleven articles allow us to consider a number of key questions in the study of dress in general, and dress in Asia more specifically. These include the divide between the timelessness of “traditional” dress and the fast-paced changes of what we call “fashion”; the categories of evidence that come into play; the ways in which Orientalism has effected the study of dress; and the approaches that are being taken to the study of dress, as well as the questions being asked.

There is a temporal tension at the center of the study of dress across Asia, one that we continue to address in our work. [11] Traditional dress in places outside of Europe and North America has been described repeatedly as timeless and unchanging (as opposed to the fast-paced changes of “fashion”), despite clear evidence to the contrary. Unwinding the reasons for this phenomenon is a complicated process, but it perhaps begins with the fact that early costume histories were written by scholars who were specialists in European dress, looking outward to other parts of the world. Understanding the changes that took place in traditional dress requires extensive research—and access to a wide range of source materials that were not necessarily available for those formative early studies. Finally, perhaps these studies reflect an overlay of Orientalist constructs of an unchanging “Orient” that persisted well into the twentieth century.

Several articles in the volume address aspects of this temporal tension. The fashion–costume divide, which is another way of referring to the perceived disjuncture between traditional and Euro-American dress, is a core issue in Heather Chan’s examination of Vogue magazine’s depictions of Chinese dress (and women) from 1892 to 1943. Chan analyzes the ways in which Chinese dress elements were framed and reframed for the Vogue audience as political and cultural circumstances changed, and she interrogates what it would mean for American ideas of modernity if China were also understood to participate in a fashion economy. While it is not the primary focus of his article, Frank Feltens refers to the fast-paced production of hinagata bon (textile pattern catalogues); the attendant commodification of dress speaks to the fact that in seventeenth-century (and later) Japan, clothing was not static. In her study of the present-day dress of Omani men, Aisa Martinez demonstrates that their clothing appears to be traditional but is in fact responsive to matters of national and regional identity in the present day.

One of the great joys and challenges of studying dress is the range of source material that can be deployed in the service of this work. Certainly, a diversity of sources is a characteristic of the papers brought together in this volume. Found in archives, archaeological contexts, large and small museums, and private collections (to name only the most obvious places), such evidence includes written accounts like dynastic histories, religious texts, legal documents, diaries, letters, and travelers’ accounts; painted representations from albums, scrolls, and architectural contexts such as tombs; and stelae as well as other archaeological remains. For later periods, photographs, magazines, and other kinds of media become extremely important. And, of course, there are the dress elements themselves, found in varying degrees of preservation and often with very little, if any, accompanying information. With their broad temporal range from the early Christian period in Egypt through the present day, studies in this volume depend on the fragmentary archaeological record (Pleşa) as well as on modern media, in the form of Vogue magazine illustrations (Chan). Written texts such as court records, travelers’ accounts, pattern books, and others are analyzed in the work of nearly every author in this volume, playing a particularly significant role in the articles by Feltens, Houghteling, and Karl. Visual representations of dress, whether in painting, photography, or other media, are key elements in the work of Mühlemann, Nolan, Scarce, and Ikeda and Adriasola. Mühlemann and Karl confront the challenges of working with scanty historical remains, while the studies by Brown and Martinez examine present-day examples of dress, with the additional ethnographic component that such material requires.

The examination of diverse categories of evidence is an essential aspect of any study of dress, but in no case are these categories of evidence straightforward. Confronting the limitations of the evidence and understanding how to assess what has come down to us is part of any historically based inquiry, and costume studies are no exception. Looking at only three of the most obvious and important categories of evidence—visual representations of dress, archaeological evidence, and textual descriptions—visual representations of dress always require extremely careful assessments of context and purpose before being used as evidence for the precise appearance or use of garments and accessories. In her article, Sylvia Houghteling marshals a range of evidence, including a series of Mughal paintings. As she considers these paintings, she is careful to note elements of dress that may be present to signal specific meanings, as opposed to portraying actual clothing worn by the ruler. This is particularly evident in her discussion of the well-known image showing the Mughal ruler Jahangir embracing his contemporary rival, Shah ‘Abbas (fig. 5). Houghteling posits that Jahangir is shown wearing simple clothes of local manufacture to make clear that he is not wearing a Safavid gift, thus asserting his independence from any foreign ruler. Similarly, the archaeological record is by nature incomplete—in drawing conclusions based on archaeological evidence, how do we account for lacunas? Alexandra Pleşa’s examination of archaeological evidence from two burial sites in Egypt includes a discussion of the methodological limitations of her study, as it is based on earlier, incomplete, and inconsistently recorded excavations. She outlines the impact of these limitations on her work and acknowledges that over time, as new material comes to light, her conclusions may well require reassessment. Such acknowledgement of the gaps or limitations of primary sources is essential. As for textual sources, to consider one important genre of such material, court historians, a prolific body of observers, were writing for a specific audience and at the behest of powerful patrons. Surely those circumstances shaped their narratives; for example, descriptions of lavish costume and jewelry were perhaps exaggerated to flatter their patrons. In the Ottoman context, Erin Hyde Nolan examines the way in which a collection of costumes was photographed for presentation in the Ottoman pavilion at the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna in order to display a modern and diverse Ottoman identity.

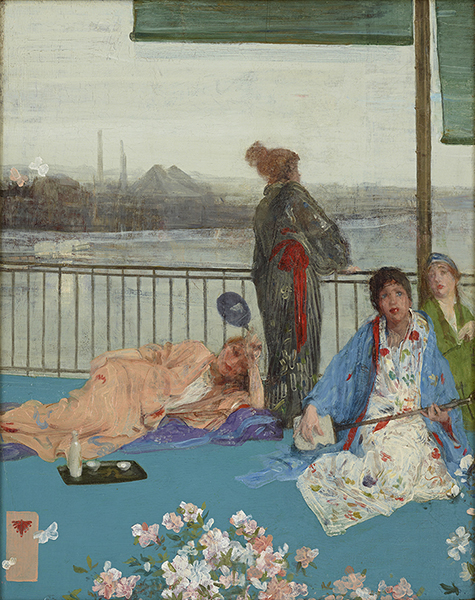

Orientalism, both as a fact and as a body of theory, has been an important influence on how we understand dress from Asia. [12] When I write of Orientalism as a fact, I have in mind the interest that Europeans and, later, North Americans took in aspects of the dress and culture of Asia and the Middle East. Emerging at different moments and places, these movements (Chinoiserie, Japonisme, Turquerie) generated a fascination with the textiles and dress of particular places, which were then reinterpreted in Europe according to local tastes (fig. 6). These movements prove useful to us because examples of dress and dress accessories that may not have been preserved otherwise may now be studied in European collections. However, these particular interests in dress were aspects of larger constructs of assumptions and understandings of the Middle East and Asia. Such constructs were tied to trade and imperial interests, which (although they played out quite differently in various places) meant that reports of local dress and customs, and even the images that were recorded by European observers, were shaped by specific assumptions; thus, these sources must be used carefully. In this volume, Jennifer Scarce’s article about Lord Byron in Albanian dress, based on his portraits and on the study of the actual garments, highlights the complex context, both at home and in the Ottoman Empire, for his purchase and wearing of a distinctive set of garments that communicated clear political messages. Heather Chan explicitly addresses the impact of Orientalism on early twentieth-century American attitudes toward China and Chinese women in her analysis of Vogue ’s representations of Chinese fashion.

The study of dress is transdisciplinary in the best sense of the word and allows us to ask—and to offer answers to—a diverse range of questions, from the very specific to the much more broad. As the articles in this volume demonstrate, knowledge gleaned through the study of dress and related materials can be used to inform a wide array of topics—for example, how the public identity of an artist can be shaped by an association with textile patterns and fashion, as Frank Feltens demonstrates in his article on Ogata Kōrin. In Ikeda Shinobu’s study, translated and introduced by Ignacio Adriasola, a series of paintings of Chinese women produced by the Japanese artist Umehara Ryūzaburō in the period 1939–43 is analyzed in the larger context of war art and as an example of how dress is used to enact ideology.

As with any historically based inquiry, the careful analysis of primary sources is essential to make a convincing and wide-ranging argument. The challenges presented by some of those sources has been mentioned above, but what sets the scholar of dress apart from most art historians is engagement with a very specific set of raw materials, complex production technologies, and vocabularies of ornament, to mention only the most general of the elements of the study of dress. In this volume, Corinne Mühlemann looks at the weaving techniques and placement of inscriptions in fragmentary remains of larger textiles to understand how they might have functioned in their original context. In her study of the ceremonial dress of a group of Nepalese Buddhist monks, Kerry Brown undertakes a detailed analysis of specific elements of their dress, particularly the ornaments on their headgear, to understand exactly which elements reflect individual choice and which convey important information about the wearer to the public. The detailed information that close attention to matters of raw material, weaving, embroidering, tailoring, and ornament provides allows the scholar to address other questions: why were these elements combined in this particular way, who made the garment, who wore or used it, what was its function in a larger social context, and, finally, what do all of these characteristics reveal about power structures, specific social or religious practices, and the aesthetic values of a society?

The eleven articles in this volume approach their subjects in a variety of ways and employ diverse methods to accomplish their research goals. As we have seen, the material which forms the basis of their research presents the gamut of what might be expected in a volume dedicated to the study of dress. From the focus on a single costume or type of garment, in the case of Jennifer Scarce and Barbara Karl’s work, to a kind of fabric or production technique (Houghteling, Mühlemann), the clothing of a particular group (Brown, Martinez) or a specific set of representations (Chan, Nolan, Feltens), and the use of archaeological remains (Pleşa) or painted representations of dress (Ikeda and Adriasola), these articles use the examination of dress and related material to advance understanding of aspects of their larger subject matter. Their work is part of an exciting and wide-ranging conversation taking place around the globe as scholars mine the world of dress for all that it can reveal about the people who make and wear clothing.

Ars Orientalis Volume 47

Permalink: https://doi.org/10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.001

Permissions: Copyright to the content of the articles published in the Ars Orientalis remains with the journal. Copyright to the images in the articles published in Ars Orientalis remains with the image rights owners. This article may be copied for use by nonprofit educational institutions, and individual scholars and educators, for scholarly or instructional purposes only, provided that (1) copies are distributed at or below cost, (2) the author, the publisher, and the Journal are identified on the copy, and (3) proper notice of the copyright appears on each copy. For other uses, content permission must be obtained from Ars Orientalis and image permission must be obtained from the rights owners.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy .

Hosted by Michigan Publishing , a division of the University of Michigan Library .

For more information please contact [email protected] .

Print ISSN: 0571-1371 • Online ISSN: 2328-1286

- Submissions

- Request Book Reviews

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Onkar Sharma

Literary Yard

Search for meaning

Clothes Make the Man

By: Richard D. Hartwell

“Clothes make the man.”

“You are judged by your appearance.”

“Your appearance reveals the real you.”

These were some of the admonitions with which I grew up. They were leveled at me almost daily: by my mother, by my stepfather, by teachers, by various and sundry girlfriends. I tried to argue with them, with the logic of them, with the fallacy of following their unstated dicta. All to no avail, as the world was ruled by the illogic of the commandment: dress well, go forth, and the world will be yours! I ignored this advice and continued to dress as the rebel, both with and without a cause, which became a senior high school yearbook caption no less.

I wore blue jeans then. I wear blue jeans now. I wore white tee shirts then with a pack of Pall Malls rolled up in the left sleeve. I quit smoking over twenty-five years ago and I affect oversize, tropical-pattern shirts now to cover my belly. I wore black penny-loafers then with white socks, but the shoes are now brown, just as comfortable, but it seems I’ve now learned to tie my own laces.

Did I lose respect from some for the way I dressed then? Of course! Do I lose it now? Perhaps, from some! Do clothes make the man? No, no more now than then, but do others still make quick judgments based on outward appearance? Of course! And for some, those quick judgments take an infinite amount of time to reverse. For some, those quick judgments become self-fulfilling and never will be reversed.

Share this:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

Archaeology/History Essay

- Sleepwalking into war — and lessons for today

A Poetics of the Pledge of Allegiance

Essay Global Politics

Walking along the eall.

White Rose, Red Orchestra: the German Resistance to Hitler

Type your email…

- Archaeology/History

- Books Reviews

- Content Marketing

- Global Politics

- Literary criticism

- LiteraryArt

- Non-Fiction

- Video Interviews

Recent Posts

- Recipe: Green Chilli Pickle

- Viral relics: what can they tell us?

- Falling for Corfu – Lessons from the Land of the Gods

- ‘Sweet Rest’ and other poems

Recent Comments

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

The Disguised Wife: Gender Inversion and Gender Conformity

DOI link for The Disguised Wife: Gender Inversion and Gender Conformity

Click here to navigate to parent product.

We’ll have a swashing and a martial outside

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Sign in to access Harper’s Magazine

We've recently updated our website to make signing in easier and more secure

Hi there . You have 1 free article this month. Connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access

You've reached your free article limit for this month. connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access, thanks for being a subscriber, keller–clothes make the man.

Wenn ein Fürst Land und Leute nimmt; wenn ein Priester die Lehre seiner Kirche ohne Überzeugung vertritt, aber die Güter seiner Pfründe mit Würde verzehrt; wenn ein dünkelvoller Lehrer die Ehren und Vorteile eines hohen Lehramtes inne hat und genießt, ohne von der Höhe seiner Wissenschaft den mindesten Begriff zu haben und derselben auch nur den kleinsten Vorschub zu leisten; wenn ein Künstler ohne Tugend, mit leichtfertigem Tun und leerer Gaukelei sich in Mode bringt und Brot und Ruhm der wahren Arbeit vorwegstiehlt; oder wenn ein Schwindler, der einen großen Kaufmannsnamen ererbt oder erschlichen hat, durch seine Torheiten und Gewissenlosigkeiten Tausende um ihre Ersparnisse und Notpfennige bringt, so weinen alle diese nicht über sich, sondern erfreuen sich ihres Wohlseins und bleiben nicht einen Abend ohne aufheiternde Gesellschaft und gute Freunde.

When a prince is seized of land and people, when a priest presents the doctrine of his church without conviction, but consumes the fruits of his sinecure with dignity, when a conceited teacher holds the honors and benefits of his educational office without the slightest thought given to the significance of his learning and without advancing it in the slightest way, when an artist achieves fame without virtue, through frivolous dealings and empty jugglery, stealing the bread and reputation of those who labor honestly; or when a swindler who inherits or obtains by fraud the name of a great commercial house and then parts thousands of their savings, then all of these people do not cry over their prospects, but rather find delight in their good fortune and never miss an evening without cheerful company and good friends.

— Gottfried Keller , Kleider machen Leute from Die Leute aus Seldwyla (1874) in Sämtliche Werke und ausgewählte Briefe vol. 2, p. 282 (C. Heselhaus ed. 1958)(S.H. transl.)

In the past week, George Will took a swipe at blue jeans. It was a high Tory romp: “Denim is the carefully calculated costume of people eager to communicate indifference to appearances,” he writes. “But the appearances that people choose to present in public are cues from which we make inferences about their maturity and respect for those to whom they are presenting themselves.” And Will offers this quite plausible lodestar for sartorial good taste: “This is not complicated. For men, sartorial good taste can be reduced to one rule: If Fred Astaire would not have worn it, don’t wear it. For women, substitute Grace Kelly.” This would give us a country looking like a movie set from the era of Art deco and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. An odd choice for Will, it strikes me, but the aesthetics were splendid.

But Will’s piece makes me think of a wonderful short story by the nineteenth century Swiss writer Gottfried Keller. It’s called Kleider machen Leute and is rendered in English as Clothes Make the Man (although Keller’s usage is not gender specific). It tells the story of a young Silesian apprentice tailor who, wandering in the countryside on a dismal November day without a penny in his pocket (his boss being on the verge of bankruptcy and having withheld his wages) is mistaken based on the very fine cut of his clothes and his fur hat. A driver jokingly refers to him as “Mister Count,” and soon the entire town takes him for a down-on-his-luck Polish nobleman. Keller is a very fine story teller, perhaps the best that Switzerland ever produced, and his eye for fine detail and ironic juxtaposition and his ability to blend the poignant, tragic and comic in a short work are very impressive. This story surely is one of his best, because it can be appreciated as a simple anecdote, as a masterful demonstration of the raconteur’s art, or as a work that delivers a powerful moral message. Keller also stands out in my view because, like very few other writers of his age who use the German language, he sings the hymn of democracy and freedom—that credo is indeed essential to his work. But the subject that Will takes up lies right at the heart of Keller’s work.

In Clothes Make the Man , Keller records with great attention the sort of judgment that society makes on an individual almost entirely on the basis of clothes. Indeed, he makes the plot turn on this fact. In the course of this we see a rehearsal of the questions that Will raises: do clothes show the respect a person shows towards his society and those with whom he deals? Do they present an opportunity for self-expression? Can they be a vehicle for deception? But in the end, Keller describes very carefully the prejudices that Will has taken to heart, but he does not share them. For Keller, clothes do not in fact make the man, they may give some sense of him, but often as not that will be deceptive. It is the content of a man’s character that makes him, of course. And in the end we learn that an unassuming Silesian apprentice may indeed be a noble figure, though the nobility is of another sort.

But for Will, denim is a token of change and rebellion. He calls its attraction a sign of “arrested development” and seems to see in it a sign of the youth movement of 1968. But perhaps he’s reading a bit too much into this. Perhaps the attraction of denim is largely a matter of comfort and not politics. I remember being lectured by my grandmother. Jeans, she said, were for farm workers. For my generation, they were part of an essential style palette, they are practical and comfortable. But such style shifts have occurred many times before and likely will again. Will takes us back to the age of Edmund Burke. In the age of revolution, the tories wore their hair in a pigtail, as did the Old Whigs like Burke, while the younger generation wore their hair loose and disdained wearing anything wrapped around their necks. George Will then would have been a devotee of the pigtail, just as Will today abhors denim. Indeed, it would hardly suit him. Will belongs in a three-piece suit with a starched shirt and an Oxford college tie. I couldn’t imagine him comfortable in other clothes.

More from Scott Horton

Lincoln’s Party

Sidney Blumenthal on the origins of the Republican Party, the fallout from Clinton’s emails, and his new biography of Abraham Lincoln

Joseph Hickman discusses his new book, The Burn Pits, which tells the story of thousands of U.S. soldiers who, after returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, have developed rare cancers and respiratory diseases.

Beltway Secrecy

In five easy lessons

“An unexpectedly excellent magazine that stands out amid a homogenized media landscape.” —the New York Times

Quote Investigator®

Tracing Quotations

Clothes Make the Man. Naked People Have Little or No Influence in Society

Mark Twain? Merle Johnson? Apocryphal?

Clothes make the man. Naked people have little or no influence in society.

But I cannot seem to find any direct reference for this quote. The best citation I have seen was dated more than fifteen years after Twain’s death in 1910.

Quote Investigator: The earliest known evidence for this saying was published in the book: “More Maxims of Mark”. This slim volume was compiled by Merle Johnson and privately printed in November 1927. Only fifty first edition copies were created, so gaining access to the work can be difficult. The Rubenstein Rare Book Library at Duke University holds book number 14 of 50. With the help of digital images captured by a friend, QI was able to verify that the quotation is present on page number 6 of this book. Below is the saying under investigation together with the preceding and succeeding entries. Maxims in the work were presented in uppercase: [1] 1927, More Maxims of Mark by Mark Twain, Compiled by Merle Johnson, Quote Page 6, First edition privately printed November 1927; Number 14 of 50 copies. (Verified with page images from the Rubenstein … Continue reading

CIVILIZATION IS A LIMITLESS MULTIPLICATION OF UNNECESSARY NECESSARIES. CLOTHES MAKE THE MAN. NAKED PEOPLE HAVE LITTLE OR NO INFLUENCE IN SOCIETY. DO YOUR DUTY TODAY AND REPENT TOMORROW.

Merle Johnson was a rare book collector, and he published the first careful bibliography of Twain’s works in 1910 shortly after the writer’s death. Twain scholars believe that the sayings compiled by Johnson in “More Maxims of Mark” are properly ascribed to Twain.

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

The notion that “clothes make the man” has a very long history. The character Polonius employed a version of the saying in William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. Here is the text from the 1604 quarto held by the Folger Shakespeare Library. Emphasis added to excerpts by QI : [2] Website: The Shakespeare Quartos Archive, Document: 1604 Quarto held by Folger Shakespeare Library, Play Title: Hamlet – The tragicall historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke, Transcription: Created … Continue reading

For the apparrell oft proclaimes the man

In 1847 the periodical “Hogg’s Weekly Instructor” embedded the adage within disapproving commentary: [3] 1847 September 11, Hogg’s Weekly Instructor, Mrs Bells Ball: A Chapter from ‘Levy Lawrence’s Account of Himself’ (In Graham’s Philadelphia Magazine), Start Page 42, … Continue reading

I remarked that I considered him a fool who said ‘clothes make the man’ —it was no such thing, the man makes the clothes . I cited instances of great geniuses who were very slovenly in their dress.

A passage that Twain wrote in one of his notebooks in the period around August 1897 dealt with the theme of this quotation. In 1935 his biographer Albert Bigelow Paine selected material from the author’s collection of notes and published a volume called “Mark Twain’s Notebook”. Here is the relevant passage: [4] 1935, “Mark Twain’s Notebook” by Mark Twain, Edited by Albert Bigelow Paine, Page 337, [August or September 1897], Harper & Brothers, New York. (Verified on paper)

Strip the human race, absolutely naked, and it would be a real democracy. But the introduction of even a rag of tiger skin, or a cowtail, could make a badge of distinction and be the beginning of a monarchy.

In 1905 Twain published a story titled “The Czar’s Soliloquy” in The North American Review. The work began with an epigram that provided the framework of the narrative: [5] 1905 March, The North American Review, Volume 180, Number 3, The Czar’s Soliloquy by Mark Twain, Start Page 321, Quote Page 321 and 322, The North American Review Publishing Company, Franklin … Continue reading

After the Czar’s morning bath it is his habit to meditate an hour before dressing himself—London Times Correspondence.

In the following two short excerpts Twain was writing in the voice of the Czar of Russia. The opinions being expressed were the Czar’s constructed and refracted through the creative prism of Twain’s intellect: [6] 1905 March, The North American Review, Volume 180, Number 3, The Czar’s Soliloquy by Mark Twain, Start Page 321, Quote Page 321 and 322, The North American Review Publishing Company, Franklin … Continue reading

As Teufelsdröckh suggested what would man be—what would any man be—without his clothes? As soon as one stops and thinks over that proposition, one realizes that without his clothes a man would be nothing at all; that the clothes do not merely make the man, the clothes are the man; that without them he is a cipher, a vacancy, a nobody, a nothing. … There is no power without clothes . It is the power that governs the human race. Strip its chiefs to the skin, and no State could be governed; naked officials could exercise no authority; they would look (and be) like everybody else–commonplace, inconsequential.

In 1927 “More Maxims of Mark” was published and it included the quotation as mentioned above in this post: [7] 1927, More Maxims of Mark by Mark Twain, Compiled by Merle Johnson, Quote Page 6, First edition privately printed November 1927; Number 14 of 50 copies. (Verified with page images from the Rubenstein … Continue reading

Many variations of the expression “clothes make the man” have been created over the years. Here are two examples printed in “Esar’s Comic Dictionary” in 1943 [8] 1943, Esar’s Comic Dictionary by Evan Esar, Page 52 and 292, Harvest House, New York. (Verified on paper)

Clothes make the man —uncomfortable. Clothes make the man, but when it comes to a woman, clothes merely show how she is made.

In conclusion, it is reasonable to credit Twain with this quotation despite the fact that the earliest evidence is posthumous.

Image Notes: Clothesline illustration from Poco a Poco: An Elementary Direct Method for Learning Spanish (1922) by Guillermo Hall.

(Thanks to correspondent Timothy Slater who told QI about a German version of the adage: Kleider machen Leute.)

Update History: On May 26, 2017 the citations dated 1604 and 1847 were added.

| ↑1, ↑7 | 1927, More Maxims of Mark by Mark Twain, Compiled by Merle Johnson, Quote Page 6, First edition privately printed November 1927; Number 14 of 50 copies. (Verified with page images from the Rubenstein Library at Duke University; special thanks to Mike) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Website: The Shakespeare Quartos Archive, Document: 1604 Quarto held by Folger Shakespeare Library, Play Title: Hamlet – The tragicall historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke, Transcription: Created from digital images of the Quarto, Website description: A joint project of six institutions in the U.K. and U.S. that hold pre-1642 Shakespeare quartos including the Bodleian Library, the British Library, the University of Edinburgh Library, and the Folger Shakespeare Library. (Accessed quartos.org on February 24, 2016) |

| ↑3 | 1847 September 11, Hogg’s Weekly Instructor, Mrs Bells Ball: A Chapter from ‘Levy Lawrence’s Account of Himself’ (In Graham’s Philadelphia Magazine), Start Page 42, Quote Page 43, Column 2, Published by James Hogg, Edinburgh, Scotland. (Google Books Full View) |

| ↑4 | 1935, “Mark Twain’s Notebook” by Mark Twain, Edited by Albert Bigelow Paine, Page 337, [August or September 1897], Harper & Brothers, New York. (Verified on paper) |

| ↑5, ↑6 | 1905 March, The North American Review, Volume 180, Number 3, The Czar’s Soliloquy by Mark Twain, Start Page 321, Quote Page 321 and 322, The North American Review Publishing Company, Franklin Square, New York. (Google Books full view) |

| ↑8 | 1943, Esar’s Comic Dictionary by Evan Esar, Page 52 and 292, Harvest House, New York. (Verified on paper) |

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CLOTHES MAKE THE MAN

2017, Ars Orientalis

Related Papers

Linda F Matheson

Linda Matheson

Here is a link to the online hosting platform, www.maneyonline.com/dre, and the corporate website at www.maneypublishing.com. Abstract This article explores a symbolic, non-western, non-contemporary, class-privileged, and dominantly masculine world-that of China's gentry and Imperial Courts in their transition from the Ming Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty (1573-1722). Modern Western theories of identity and representation through dress are analyzed-using both artifact and discourse analysis-as to whether or not they can transcend cultural and temporal contexts. In particular the essay examines Eastern evidence from the seventeenth century that supports the activity of the premise behind the trickle-down theory of clothing attributed to Georg Simmel in the twentieth century West. Additionally, issues such as cultural ambivalence, creative ferment, and collective tensions in transitional contexts are considered in testing the applicability of symbolic interactionist theory of the contemporaryWest to the changing aesthetic codes and social meanings of the royal robes in the ancient East.

Fashion Theory-the Journal of Dress Body & Culture

Paola Zamperini

Aida Y Wong

Rachel Silberstein

A Fashionable Century: Textile Artistry and Commerce in the Late Qing is an interdisciplinary study that draws on art history, fashion theory, dress history, anthropology, and cultural studies. This is the first book by Rachel Silberstein, a scholar of Chinese material culture specializing in fashion, gender and textile handicrafts. In order to better convey "the voices and texts of the Qing dynasty or studies by Chinese scholars" (p. xv), she makes extensive use of primary sources with expert translation. This volume is not a chronological survey like Antonia Finnane's Changing Clothes in China (2008) or a handbook of key garment types like Valery Garrett's Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day (2007). Rather, it is a polemical exploration of the relationship between fashion and ethnic identity, the impact of the market economy, regionalism, and women's agency. This book considers instances of transgression where ordinary people dressed up to impersonate high society as integral to fashion trends, imitating "dukes [by] wearing rank badge coats, dragon roundels, and jewel-topped hats" (p. 52) and splurging on ritual costumes which went counter to Confucian frugality. The age-old rules were such that attires had to t "the season, occasion, and most of all, identity" (p. 52). But these rules appeared to be constantly outed in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), a time of ethnic coexistence , commercial vibrancy, and technical innovation in fashion production. The anonymity of Qing creators such as workshop sta f and pattern makers presents a particular challenge to researchers, one that is compounded by the generic labeling of Chinese dress items in many museums. As Silberstein points out, there was no detailed provenance, no preface, no maker's mark, and no publisher, to verify an item's exact origins (p. 11). There were brand names and regional labels, but unlike today's fashion system which orchestrates coherent trends from season to season, product developments in the Qing dynasty proved more di fused. Silberstein further questions the fashion values expressed in formal texts that exclusively represented the viewpoints of the male literati. For a more comprehensive picture of how styles and wearers were evaluated, she not only examines gazetteers and dynastic histories, but also lesser-known, vernacular sources such as songs and "bamboo ballads" or

Positions-east Asia Cultures Critique

Heather McKay

Studies in Late Antiquity: A Journal

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

The Right to Dress

Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture, eds. J. Edmondson & A. Keith, Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press

Jonathan Edmondson

Laura Pérez Hernández

East Asian History

Sarah Dauncey

China Review International

Shao-yun Yang

The Lady with the Phoenix Crown: Tang-Period Grave Goods of the Noblewoman Li Chui (711-736)

Shing Mueller

International Journal of Fashion Studies

Svenja Bethke

Betül İpşirli Argıt

Aleksandra Hallmann

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Essay on Clothes Make The Man

Students are often asked to write an essay on Clothes Make The Man in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Clothes Make The Man

First impressions.

When you meet someone, their clothes are often the first thing you notice. Nice, clean outfits can make a person seem smart and confident. This is why people often dress up for important events like job interviews or weddings.

Feeling Good

Social signals.

What we wear sends messages to others about who we are. Uniforms, for example, show that a person belongs to a certain group, like a school or a company.

Respect and Manners

Dressing properly for different places shows respect. Wearing the right clothes to a religious place or a formal party is part of good manners. It shows you understand and care about the rules of where you are.

250 Words Essay on Clothes Make The Man

Introduction to the saying.

When you meet someone for the first time, the way you dress can make a big difference. Nice and tidy clothes can give the impression that you are neat and take care of yourself. This can help in situations like job interviews or meeting new friends.

Confidence Booster

Wearing clothes that you feel good in can also make you feel more confident. When you know you look good, you might do better in school or feel braver to speak up. It’s like putting on a superhero costume; you feel stronger and more powerful.

Respect and Responsibility

Dressing properly for different events shows respect. For example, wearing a uniform at school means you are part of a team. It can also teach you to be responsible for keeping your clothes clean and ready.

Clothes Don’t Define You

Even though clothes can say a lot, they don’t tell everything about who you are. It’s important to remember that being kind, smart, and hardworking is much more important than what you wear.

In the end, clothes can help make a good impression and give you confidence, but the real you is about your actions and your heart. It’s fine to dress well, but always make sure your personality shines brighter than your outfit.

500 Words Essay on Clothes Make The Man

There is an old saying that goes, “Clothes make the man.” What this means is that what we wear can say a lot about who we are. It’s not just about looking good, but also about how clothes can make us feel confident and change how others see us. In this essay, we will talk about why clothes are important and how they can affect our lives.

When we meet someone for the first time, we often notice what they are wearing. Nice, clean, and well-fitting clothes can make a good first impression. This is important in many situations, like job interviews or the first day at a new school. If we dress well, people may think we are smart and serious about our work or studies. This doesn’t mean we need expensive clothes, but wearing clothes that are right for the occasion can help us start on the right foot.

Wearing clothes that we like and that fit us well can make us feel more confident. When we know we look good, we might stand taller, smile more, and speak more clearly. This confidence can help us do better in school, in sports, or when we talk to new people. It’s like wearing a superhero’s costume – it gives us a little extra power to face the world.

Clothes and Culture

Clothes can also tell a story about where we come from. Traditional outfits from different countries can show our culture and heritage. For example, a Japanese kimono or an Indian sari can share a part of our history and traditions with others. By wearing these clothes, we keep our culture alive and share it with others.

Expression of Personality

The colors and styles we choose to wear can show our personality. Someone who loves bright colors and fun patterns might be showing that they are creative and like to have fun. On the other hand, someone who wears a lot of black or gray might want to look serious or just likes those colors. Our clothes let us express who we are without saying a word.

Dressing appropriately for different places shows respect and responsibility. At school, there might be a dress code that helps students learn how to dress for different situations. By following the dress code, students show that they respect the rules and understand what is expected of them. This is a skill that will help them later in life when they go to work or attend important events.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Clothes Make the Man—Literally

What we wear affects how we perceive ourselves.

Posted August 24, 2012

At my school’s sleep research facility, we are bringing back students for a follow-up study. Most of them don't seem to recall the uncomfortable beds or having electrodes pasted to their scalp from their baseline test, which was done back when they were in elementary school. (For our sake in recruiting participants, that's probably for the best.)

Nowadays they're older, wiser, more self-aware, and, as teenagers , a bit more judgmental. The researchers in charge of performing psychometric testing—new college grads and not much older or taller than the participants themselves—recently made an interesting observation: if they wear a white coat when interacting with the participants (and their parents), they receive more respect.

According to a study by Hajo Adam and Adam Galinsky of Norwestern University, it's possible that these individuals not only look more professional, but subconsciously feel more professional. In other words, the clothes may literally make the man (or woman).

The study, published February in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , observed an interesting phenomenon: wear a white coat you believe belongs to a doctor, and you'll be more focused. Wear a white coat you believe belongs to a painter, and you won't see that improvement.

It's been well-established—in the scientific literature and real life—that what we wear affects how others perceive us. Women who wear more masculine clothes to an interview (such as a dress suit) are more likely to be hired. People dressed conservatively are perceived as self-controlled and reliable, while those wearing more daring clothing are viewed as more attractive and individualistic.

We've recognized these distinctions since childhood —we learn what's appropriate to wear to school, to interviews, to parties. Even those confined to uniform convey their own unique style in an attempt to change how they are perceived by others.

This new study contributes to a growing field known as "embodied cognition "—the idea that we think with not only our brains, but with our physical experiences. Including, it seems, the clothes we're wearing.

Adam and Gallinsky explored this notion in three simple experiments:

In the first experiment, 58 participants were randomly assigned to wear either a white lab coat or street clothes. They were then subject to an incongruity task in which they had to spot items that didn't belong to a set (for instance, the word "red" written in green ink). Those in white coats made half as many errors as those in street clothes.

Next, 74 participants were subject to one of three conditions: wearing what they believed to be a doctor's coat, wearing a painter's coat, or simply seeing a doctor's coat nearby. They then underwent a sustained attention task, studying two similar pictures side-by-side in order to spot the four minor differences between them (not unlike these fun little tasks designed to keep a kid busy for...well, a few minutes anyway). Those who believed they were wearing a doctor's coat (which was, in fact, identical to the painter's coat) spotted more differences than the other two test groups.

Finally, participants wore either doctors' or painters' coats, and were instructed to examine a doctor's lab coat displayed in front of them. They then wrote essays on their opinion of each coat type. Once again, they were tested for sustained attention ("spot the difference"). Again, those wearing the coat saw the greatest improvement in the task. Simply looking at the item, then, does not affect behavior.

According to Galinsky, we must see and feel the clothes on our body— experience it in every way—for it to influence our psyche.

The symbolic meaning of a doctor's lab coat is clear. Physicians are careful, hardworking, and attentive. Do the psychometric testers in my lab become doctors—mentally—when they decide to put on a white coat? Do police officers feel braver on duty in uniform than they normally would in street clothes? Perhaps more importantly, does one dressed as an M&M for Halloween become chocolate?

Another important question remains. Do the cognitive changes last for long periods, or do they eventually wear off? Will one always feel more focused and attentive in a white coat, or will one habituate? According to Galinsky, further research is needed.

In the meantime, if you'll excuse me, I must go hijack a very large person and test my M&Ms costume theory.

Adam, H., & Galinsky, A. (2012). Enclothed cognition Journal of Experimental Social Psychology DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.02.008

Jordan Gaines Lewis, Ph.D. , is a science communicator and postdoctoral researcher at Penn State College of Medicine.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

U.S. Dictionary.com Newsletter

Fill in the form below and receive news in your email box, clothes make the man: definition, meaning, and origin.

The phrase "clothes make the man" is an old saying that points out the significant impact of clothing on a person's image and how they are perceived by others. It suggests that attire can influence one's social standing, professional image, and overall impression.

- It implies that clothing significantly affects how a person is viewed by others.

- It encourages dressing appropriately to enhance one's image and social perception.

What Does "Clothes Make the Man" Mean?

The phrase "clothes make the man" underscores the importance of dressing well and its influence on societal perceptions and personal branding. The saying is often used to express the idea that good clothing can make someone look more competent, professional, and trustworthy. For example , choosing to wear a formal suit for a job interview often leaves a better impression, suggesting seriousness and respect for the occasion. This phrase is a reminder that attire is not merely about fashion, but it also plays a crucial role in how people interact with and judge us.

More about the phrase's meaning:

- It stresses the role of clothing in creating a positive or desired impression.

- The phrase is used to encourage people to dress suitably for various situations.

- It conveys the idea that a person's outfit can enhance their confidence and perceived status.

- This saying is applicable in diverse settings, from professional environments to social gatherings.

- Related expressions include "dress for success" and "the tailor makes the man."

Where Does "Clothes Make the Man" Come From?

This idea was first expressed by Homer in his epic poem, the Odyssey, and it has been echoed by many other writers and thinkers throughout history, including Erasmus, Shakespeare, and Mark Twain. The proverb “clothes maketh the man” was first recorded in Latin by Erasmus in his book Adagia. Erasmus quotes Quintilian: “From these things, you may be sure, men get a good report” and “To dress within the formal limits and with an air gives men, as the Greek line testifies authority.” This implies that dressing well can help a person to project an image of authority and competence.

Historical Example

"Well, if it is true that 'clothes make the man,' "said Mr. Stuart," I am afraid our opinions may not be always correct, and in some cases might not be very charitable." - Hazel; or, Perilpoint Lighthouse by Emily Grace Harding, 1885

10 Examples of "Clothes Make the Man" in Sentences

To understand how this phrase is used in everyday life , let's look at some examples:

- He always believed that clothes make the man , so he dressed sharply for every business meeting.

- She advised her son that clothes make the man as he prepared for his first job interview.

- I am rooting for you in this competition, remember, clothes make the man , so choose your outfit wisely.

- When he started his new role, he remembered the saying clothes make the man and invested in a new wardrobe.

- Have a safe trip , and don't forget, clothes make the man , so pack accordingly to make a good impression.

- Even if you’re old skool , clothes make the man , so dressing appropriately for the occasion is key.

- In the novel, the character transformed his life by following the principle that clothes make the man .

- She saw a motivational quote online saying, "In business, clothes make the man ."

- Want to make waves at the event? Clothes make the man , so choose an outfit that stands out.

- Dress to impress at the gala because, as the saying goes, clothes make the man , and your attire can leave a lasting impression.

Examples of "Clothes Make the Man" in Pop Culture

This phrase is quite popular in pop culture, often used in contexts where appearance is key to character development or storyline.

Here are some notable examples:

- John White's book " CLOTHES MAKE THE MAN: Dress for Success in Business and Life " offers guidance on how men can use their wardrobe to succeed in their personal and professional lives.

- Finnian Burnett's novella " The Clothes Make the Man " delves into its characters' emotional journeys, focusing on the significant role of clothing in their lives.

- In the 1990 film "Joe Versus the Volcano," the character Marshall, portrayed by Ossie Davis, utters the line, " Clothes make the man. I believe that ," underlining the importance of attire.

- Logan's song " Clothes Make the Man ," available on Spotify, explores the theme of how clothing shapes one's identity and the way others perceive them.

- The "Hangin' with Mr. Cooper" TV episode titled " Clothes Make the Man ," released in 1994, centers around the characters being duped into buying costly clothing, highlighting the societal focus on outward appearances.

Synonyms: Other Ways to Say "Clothes Make the Man"

Various other phrases convey a similar meaning:

- Dress for success

- Appearance matters

- Fashion defines

- Attire reflects character

- Style speaks volumes

- Wardrobe influences perception

- Dress shapes the person

- Outfit impacts impression

- Clothing speaks

- Garments tell a story

10 Frequently Asked Questions About "Clothes Make the Man":

- What does "clothes make the man" mean?

"Clothes make the man" suggests that a person's attire significantly influences how they are perceived by others. It implies that good dressing can enhance one's image and status.

- How can I use "clothes make the man" in a sentence?

You can use it to emphasize the importance of dressing well. For example: "He always dresses impeccably for interviews, truly believing that clothes make the man."

- Is "clothes make the man" relevant in today's world?

Yes, it remains relevant, especially in professional and social contexts where first impressions based on attire can be crucial.

- Can "clothes make the man" apply to women as well?

Yes, the phrase is gender-neutral in its modern application. It applies to anyone, regardless of gender, emphasizing the importance of appearance.

- Is this phrase often used in the fashion industry?

Yes, it's commonly used in the fashion industry to highlight the impact of clothing on personal branding and image.

- Does dressing well always guarantee success?

No, while dressing well can contribute to a positive impression, success also depends on other factors like skills, experience, and attitude.

- Are there cultures where "clothes make the man" is more relevant?

The importance of attire varies across cultures, but in many societies, particularly those with formal business cultures, this phrase holds significant relevance.

- Can this phrase create pressure to conform to certain dress standards?

Yes, it can lead to pressure to conform to certain dress codes, especially in professional environments.

- How has the meaning of "clothes make the man" evolved over time?

The core idea remains the same, but its application has broadened to include a wider range of personal and professional contexts, and it's more inclusive of different styles and trends.

- Is there a negative side to "clothes make the man"?

Yes, it can perpetuate superficial judgments based on appearance and can sometimes overshadow the importance of a person's character and abilities.

Final Thoughts About "Clothes Make the Man"

The phrase "clothes make the man" is a timeless concept that emphasizes the power of clothing in shaping perceptions. While it's a valuable reminder of the impact of personal appearance, it's also important to balance this with an understanding of the individual's qualities beyond their attire.

- It's a phrase that highlights the influence of clothing on perception and status.

- Applicable to all genders, it's relevant in various cultural and professional contexts.

- While beneficial in some respects, it's important not to rely solely on attire for judgments about a person.

- The phrase has evolved to encompass diverse fashion trends and personal expressions.

Related posts:

- Laugh Riot: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- A Perfect Match for: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- A Quarter Past 8: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Put Foot in Mouth: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Slip My Mind: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- To Hit The Head: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Brick Someone: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Tune Into: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Go Easy on Me: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Headed Back: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- As Per: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Below Par: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Out of Context: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- Scarred Me for Life: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- If at First You Don't Succeed, Try, Try Again: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

We encourage you to share this article on Twitter and Facebook . Just click those two links - you'll see why.

It's important to share the news to spread the truth. Most people won't.

- Register: Definition, Meaning, and Examples

- Doesn't Suit Me: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

- A: Definition, Meaning, and Examples

- Mince Words: Definition, Meaning, and Origin

Exploring the Intersection of Art, Faith and the Human experience

Do Clothes Make the Man? An Essay by Edward Knippers

Clothes make the man. Naked people have little or no influence on society – Mark Twain

…apparel oft proclaims the man… – William Shakespeare

the man is his clothing – Classical Greek

Why Clothes?