- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

- Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

University News | 2.1.2022

The Legal Landscape for Climate Change

Jody freeman on the possibilities for federal action.

Cox professor of law Jody Freeman spoke recently about climate change and the law Art courtesy of the Harvard Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning

What is the U.S. legal landscape for addressing climate change? Cox professor of law Jody Freeman provided an overview of the dynamics among the three branches of federal government during a January 31 Zoom talk convened by the Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning. What she had to say about the Supreme Court was eye-opening.

Freeman, a former counselor for energy and climate change in the Obama administration from 2009 to 2010, and now an independent director of fossil fuel producer ConocoPhillips, began with background: the Biden administration’s policy challenges, the deadlock in Congress, and the role the courts play.

Regulating Three Major Sources of Greenhouse Gases

The recent history of executive-branch climate actions, she recounted, saw the Trump administration freezing, rolling back, or rescinding “every major Obama administration climate effort, whether it was regulating carbon emissions from the power sector,…trying to control emissions from the oil and gas industry, [or]…withdrawing from the international climate agreement known as the Paris accord.”

• Transportation . The Biden administration in turn has sought to halt the changes Trump had initiated, by asking the courts to hold the regulations Trump promulgated in abeyance. Acting through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which “has the legal authority to take these steps under the Clean Air Act of 1972,” the White House has since early 2021 developed a new round of standards for the transportation sector, made final in December; they would control carbon dioxide emissions from cars and trucks from 2023 to 2026 more stringently than the standards put forth under the Trump EPA. (Rules for 2027 and beyond are being developed now.)

“All of those standards are really designed to ramp up over time and drive electrification,” said Freeman—and aimed to fulfill President Biden’s pledge that “half of the new cars sold in 2030 will be zero-emission vehicles. And the auto industry, including GM and Ford and others, have lined up to say they have an aspiration or goal to make sure that at least half of all new cars” and 40 to 50 percent of new trucks sold in 2030 or 2035 will be electric or zero-emission. That, she said, is “a big promise.”

• Methane . In a parallel effort, she continued, the EPA has proposed a set of standards for all oil and gas facilities to control methane leaks. Methane is a much more potent, but much shorter-lived, greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, making it “the single fastest, most effective opportunity we have to reduce the impact of climate change.” The standards are designed to require detection, monitoring, and control of methane from existing and new oil and natural-gas operations, including production, processing, transmission, “and the rest.” After transportation, “that is the second important sector that the Biden team has identified as a big contributor to greenhouse gases.”

• Electric power . Finally, the “third leg” of the major Biden climate rules, in development now, are new standards for the electric-power industry—the area, Freeman explained, in which the courts have become involved. The Trump administration had advanced “a very weak rule” regulating the power sector that adopted “a narrow…theory of the government’s authority.” That approach, and its premise that regulation could only be applied to effect marginal changes at individual power plants, rather than covering the sector as a whole, “wound up in the courts,” said Freeman, “and the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the Trump rule, which said that the government couldn’t do much to regulate the power sector.”

Although the rule no longer exists, Freeman explained, “the Supreme Court did grant review [of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision] and said it would hear the case,”—perhaps to use it “as an opportunity to send a message to the Environmental Protection Agency not to get out over its skis with the next regulation.”

Even as the Biden administration works to develop its own rule to regulate the power sector, it finds itself in the peculiar position of having to go to court to defend the Trump-era approach—“a complicated legal situation,” as she characterized it.

Congressional Inaction and Limits on Executive Power

Stepping back for a moment from the particulars of the Biden approach, Freeman asked rhetorically, “Why is the President using his executive power, with executive-branch agencies like EPA, to put in place a climate plan?” The answer, she said, is that “Congress has largely failed to adopt an approach to climate change.” The recently enacted, trillion-dollar infrastructure bill, she said, could have included a grant system for clean energy that would have awarded money to the power sector if it lowered greenhouse-gas emissions year over year—and penalized it if it did not, “but that never made it through Congress.” And although Congress has allocated funds to support electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, a step she called “very positive,” there has been no major legislation to drive greenhouse-gas emissions down.

Given that “Congress isn’t adopting climate policy,” the President is using the executive branch, through “laws on the books…to make as much progress as possible.” At the Glasgow climate meeting last November—the annual conference of the parties to the Paris Agreement—the administration pledged to reach “a 50 to 52 percent reduction in U.S. net economy-wide greenhouse-gas emissions by 2030, which is a very significant pledge. Delivering on that,” Freeman noted, “depends now on these major regulations” governing transportation, oil and gas production, and power generation.

Freeman said she considers these developments to be positive steps, but that the rules would need to be made final during the Biden presidency and then built upon in a second term or by a successor president in order to meet such ambitious goals. Doing so will be difficult without congressional action, she noted.

The Supreme Court’s Blocking Role

Notably, the Supreme Court might play a major role in determining the success or failure of U.S climate-change policy. “As you know, there are now six justices appointed by Republicans who appear to be poised to undo precedents,” said Freeman. “They’re not being shy about willingness to reject government regulation when they think that the government has overreached,” she explained, citing their rejection of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s vaccine mandate for businesses. She said the governing statute is broadly worded and gives OSHA “quite capacious power to set workplace safety standards” and to protect workplaces from new hazards. The fact that the Court struck that down is “a signal” that the Court has reservations about broad government regulation.

With respect to climate change, “We’re waiting to see what the Supreme Court may do to clip the wings of the Environmental Protection Agency” as part of its review of the Trump-era power-sector rule: “There’s some concern that the Court’s reading of the Clean Air Act” will constrain the agency’s rulemaking authority.

Freeman described the stakes as enormous: “If that were to happen, we’d be left in a world, in the United States anyway, where the Congress is largely inactive on climate change” and the executive branch might be “severely constrained by a Supreme Court skeptical of regulatory power.” (For background on the long-term fallout of climate change, see the Harvard Magazine feature article, “ Controlling the Global Thermostat .”)

“The starkest way to put it,” she continued, “is that we could find ourselves in a place where climate policy is not being made by the United States Congress, nor…by the elected president carrying out delegated power under laws long on the books, but…by six Supreme Court justices who are unaccountable and unelected.” If such a scenario were to transpire, Freeman put it delicately, “I think that would be an uncomfortable place for climate policy.”

Were that to occur, the Supreme Court’s limitation on U.S. action would also adversely affect international efforts to address climate change, Freeman said: U.S. leadership on climate is crucial to the success of the coalition of both large and rapidly growing economies around the world.

But encouragingly, Freeman concluded, there is broad domestic industry support for climate regulation. Automobile manufacturers have “largely lined up in favor of the new car standards,” she said, and “quite a considerable section of the oil and gas industry has been supportive of comprehensive methane regulation.” In addition, “a significant swath of the electric power industry wants the EPA to regulate their sector; they don’t want the court to scuttle the EPA’s authority” to regulate them. “My hope” she concluded, is that “the Biden administration succeeds…, the court does not severely constrain the EPA’s authority, and that success will breed success.”

You might also like

Talking About Tipping Points

Developing response capability for a climate emergency

Historic Humor

University Archives to preserve Harvard Lampoon materials

Academia’s Absence from Homelessness

“The lack of dedicated research funding in this area is a major, major problem.”

Most popular

Claudine Gay in First Post-Presidency Appearance

At Morning Prayers, speaks of resilience and the unknown

Post-COVID Learning Losses

Children face potentially permanent setbacks

Plants on a Changing Planet

How long will the world’s forests impound carbon below ground?

More to explore

Why do Groups Hate?

Mina Cikara explores how people come into conflict, in politics and beyond

Private Equity in Medicine and the Quality of Care

Hundreds of U.S. hospitals are owned by private equity firms—does monetizing medicine affect the quality of care?

John Harvard's Journal

Construction on Commercial Enterprise Research Campus in Allston

Construction on Harvard’s commercial enterprise research campus and new theater in Allston

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS EXPLAINER

- 16 April 2024

Do climate lawsuits lead to action? Researchers assess their impact

- Carissa Wong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

More people are filing lawsuits against governments and corporations for not doing enough to combat climate change. Credit: Suleiman Mbatiah/AFP via Getty

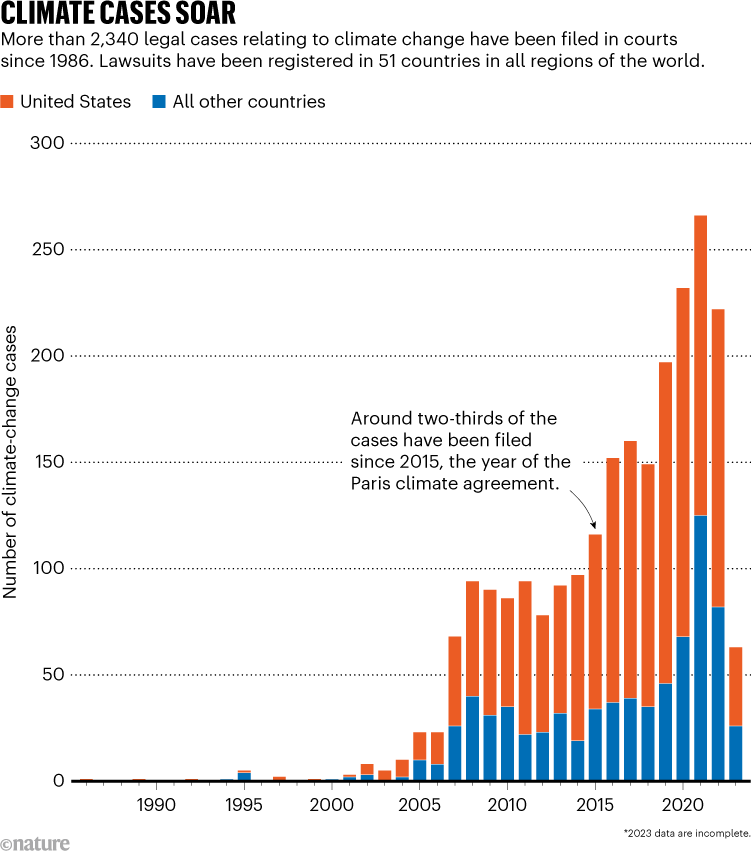

Climate litigation is in the spotlight again after a landmark decision last week. The top European human-rights court deemed that the Swiss government was violating its citizens’ human rights through its lack of climate action. The case, brought by more than 2,000 older women , is one of more than 2,300 climate lawsuits that have been filed against companies and governments around the world (see ‘Climate cases soar’).

But does legal action relating to climate change make a difference to nations’ and corporations’ actions? Litigation is spurring on governments and companies to ramp up climate measures, say researchers.

‘Truly historic’: How science helped kids win a landmark climate trial

“There are a number of notable climate wins in court that have led to action by governments,” says Lucy Maxwell, a human-rights lawyer and co-director of the Climate Litigation Network, a non-profit organization in London.

Nature explores whether lawsuits are making a difference in the fight against global warming.

What have climate court cases achieved?

One pivotal case that spurred on change was brought against the Dutch government in 2013, by the Urgenda Foundation, an environmental group based in Zaandam, the Netherlands, along with some 900 Dutch citizens. The court ordered the government to reduce the country’s greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 25% by 2020, compared with 1990 levels, a target that the government met. As a result, in 2021, the government announced an investment of €6.8 billion (US$7.2 billion) toward climate measures. It also passed a law to phase out the use of coal-fired power by 2030 and, as pledged, closed a coal-production plant by 2020, says Maxwell.

Source: Grantham Research Institute/Sabin Center for Climate Change Law

In 2020, young environmental activists in Germany, backed by organizations such as Greenpeace, won a case arguing that the German government’s target of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels was insufficient to limit global temperature rise to “well below 2 ºC”, the goal of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. As a result, the government strengthened its emissions-reduction target to a 65% cut by 2030, and set a goal to reduce emissions by 88% by 2040. It also brought forward a target to reach ‘climate neutrality’ — ensuring that greenhouse-gas emissions are equal to or less than the emissions absorbed from the atmosphere by natural processes — by 2045 instead of 2050. “In the Netherlands and Germany, action was taken immediately after court orders,” says Maxwell.

In its 2022 report , the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change acknowledged for the first time that climate litigation can cause an “increase in a country’s overall ambition to tackle climate change”.

“That was a big moment for climate litigation, because it did really show how it can impact states’ ambition,” says Maria Antonia Tigre, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University in New York City.

What about cases that fail?

Cases that fail in court can be beneficial, says Joana Setzer at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

In a 2015 case called Juliana v. United States , a group of young people sued the US government for not doing enough to slow down climate change, which they said violated their constitutional right to life and liberty. “This is a case that has faced many legal hurdles, that didn’t result in the court mandating policy change. But it has raised public awareness of climate issues and helped other cases,” says Setzer.

One lawsuit that benefited from the Juliana case was won last year by young people in Montana , says Setzer. The court ruled that the state was violating the plaintiffs’ right to a “clean and healthful environment”, by permitting fossil-fuel development without considering its effects on the climate. The ruling means that the state must consider climate change when approving or renewing fossil-fuel projects.

What happens when people sue corporations?

In a working paper , Setzer and her colleagues found that climate litigation against corporations can dent the firms’ share prices. The researchers analysed 108 climate lawsuits filed between 2005 to 2021 against public US and European corporations. They found that case filings and court judgments against big fossil-fuel firms, such as Shell and BP, saw immediate drops in the companies’ overall valuations and share prices. “We find that, especially after 2019, there is a more significant drop in share prices,” says Setzer. “This sends a strong message to investors, and to the companies themselves, that there is a reputational damage that can result from this litigation,” she says.

In an analysis of 120 climate cases, published on 17 April by the Grantham Research Institute, Setzer’s team found that climate litigation can curb greenwashing in companies’ advertisements — this includes making misleading statements about how climate-friendly certain products are, or disinformation about the effects of climate change. “With litigation being brought, companies are definitely communicating differently and being more cautious,” she says.

What’s coming next in climate litigation?

Maxwell thinks that people will bring more lawsuits that demand compensation from governments and companies for loss and damage caused by climate change. And more cases will be focused on climate adaptation — suing governments for not doing enough to prepare for and adjust to the effects of climate change, she says. In an ongoing case from 2015, Peruvian farmer Saúl Luciano Lliuya argued that RWE, Germany’s largest electricity producer, should contribute to the cost of protecting his hometown from floods caused by a melting glacier. He argued that planet-heating greenhouse gases emitted by RWE increase the risk of flooding.

More cases will be challenging an over-reliance by governments on carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies — which remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it underground — in reaching emissions targets, says Maxwell. CCS technologies have not yet proved to work at a large scale. For instance, in February, researchers criticized the European Union for relying too much on CCS in its plans to cut greenhouse-gas emissions by 90% by 2040 compared with 1990 levels.

“There is a tendency now for companies and governments to say, we’ll use carbon capture, we’ll find some technology,” says Setzer. “In the courts, we’ll start seeing to what extent you can count on the future technologies, to what extent you really have to start acting now.”

What about lower-income countries?

There will also be more climate cases filed in the global south, which generally receive less attention than those in the global north, says Antonia Tigre. “There is more funding now being channelled to the global south for bringing these types of cases,” she says. This month, India’s supreme court ruled that people have a fundamental right to be free from the negative effects of climate change.

Last week’s Swiss success demonstrates that people can hold polluters to account through lawsuits, say researchers. “Litigation allows stakeholders who often don't get a seat at the table to be involved in pushing for further action,” says Antonia Tigre.

Maxwell thinks that the judgment will influence lawsuits worldwide. “It sends a very clear message to governments,” she says. “To comply with their human-rights obligations, countries need to have science-based, rapid, ambitious climate action.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-01081-w

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Climate change

Exclusive: official investigation reveals how superconductivity physicist faked blockbuster results

News 06 APR 24

Is IVF at risk in the US? Scientists fear for the fertility treatment’s future

News 02 APR 24

Sam Bankman-Fried sentencing: crypto-funded researchers grapple with FTX collapse

News 28 MAR 24

Will AI accelerate or delay the race to net-zero emissions?

Comment 22 APR 24

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is ‘transforming’ from repeated coral bleaching

News 19 APR 24

Nearly half of China’s major cities are sinking — some ‘rapidly’

News 18 APR 24

Research Associate - Brain Cancer

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Senior Manager, Animal Care

Research associate - genomics, postdoctoral associate- artificial intelligence, postdoctoral research fellow.

Looking for postdoctoral fellowship candidates to advance genomic research in the study of lung diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital and HMS.

Boston, Massachusetts

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Frontiers in Climate

- Climate Law and Policy

- Research Topics

Climate Law and Policy 2023: A Proactive Retrospective on Intergovernmental Strategies

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

This collection explores the immediate implications for climate law and policy following the 27th Conference of Parties (COP27) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), released in a series of volumes beginning in late 2022. The short articles and essays in ...

Keywords : IPCC AR6, COP 27, environmental justice, carbon taxes, climate law and policy, geoengineering

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines, participating journals.

Manuscripts can be submitted to this Research Topic via the following journals:

total views

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

Harvard Law School

07/30/2020 - Corporate Climate Disclosures

Climate Change is Changing the Practice of Law

by Hana Vizcarra

Staff Attorney Hana Vizcarra was a panelist on the CLE Showcase panel “Climate Change and the Legal Profession: Beyond ‘Environmental Law’” held on July 30, 2020 at the American Bar Association’s 2020 Annual Meeting . This post is based on remarks she made as part of that panel. If you are an ABA Member you can attend the 2020 Virtual Annual Meeting for free and watch this and other panels on demand.

In 2019, the American Bar Association (ABA) House of Delegates adopted a resolution on climate change . The resolution urges government and the private sector to recognize their obligation to address climate action and to take action, urges Congress to enact climate change legislation and the US government to engage in international efforts to address climate change. The ABA also called on lawyers to take on climate change-related pro bono activities and to advise their clients of the risks and opportunities of climate change.

As part of its commitment to this resolution, the ABA included a panel on climate change and the practice of law at its 2020 Annual Meeting. The CLE Showcase event was moderated by Roger Martella of GE and panelists included myself, Prof. Michael Gerrard of Columbia Law, and Hilary Tompkins of Hogan Lovells. We discussed how climate change is impacting the practice of law, and not just environmental law. This post summarizes some of my remarks as part of this event.

Environmental law is interdisciplinary. One of the reasons I enjoy practicing environmental law is that it touches every part of the economy, every industry, and engages the full spectrum of lawyering skills. We work on transactions, litigate, advise on compliance and regulation, etc. We are not simply the keepers of the secrets of the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, NEPA, and other core environmental statutes; we are also administrative law attorneys, comfortable with torts, familiar with contract and land use law, and regularly encounter constitutional law questions.

And yet, the number of practice areas that intersect with environmental law only seem to grow, particularly when it comes to climate change. Try as we might, environmental lawyers can’t be experts in all aspects of these other areas of law. Other practitioners need to be familiar enough to recognize when and how climate change-related issues impact their work.

Climate change will affect your practice. Climate change is already impacting how we live our lives and how companies do business. And when that happens, it impacts the law.

Corporate disclosure practices are changing in the face of persistent efforts by shareholders and stakeholders to encourage more transparency on climate change risks and opportunities. As shareholders internalize the possibility of climate change impacts on the companies they invest in, they recognize climate-related information as crucial to their decisionmaking. Concern about climate change and desire for more insight into corporate strategy on the topic is no longer limited to values investors trying to get companies to do good in the world. This information now forms part of the total mix of information that investors want to consider in their analyses.

I don’t want to overstate the extent to which investors use climate-related information right now. This continues to be an evolving space but it is one that has changed rapidly in the last few years as shareholders become more knowledgeable on the issues, better understand the scope of information available to them, and have put resources towards figuring out how to integrate that information into their decisionmaking tools. Because of the malleable nature of the materiality standard in US securities law, investors’ increasing use of climate-related information can impact what the law sees as required disclosures. [1] Securities lawyers will be asked to consider these changes in investor demands and trends in corporate reporting.

Concern over climate change uncertainties goes beyond investors. It is changing how the whole financial sector evaluates its assets and what conditions are placed on companies to receive financing. Banks have announced new lending policies that restrict lending to certain types of extractive industries and are trying to better understand the scope of their own risks. Many financial institutions have shareholders pressuring them on their climate-related disclosure as well and there is increasing interest among bank regulators. The Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure recommendations released in 2017 included supplemental guidance for the financial sector about how financial entities should disclose climate risks and opportunities.

Financial regulators are already considering whether climate change poses systemic risks to the financial system. While US regulators are generally behind their European counterparts in grappling with how to address climate risks in their supervisory and regulatory capacities, they are not ignoring the issue. The CFTC is preparing a report right now on climate-related systemic risk to the financial sector for which it requested public comment . The Federal Reserve is also assessing these risks. US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said in January that the Fed has a role to play “to ensure that the financial system is resilient and robust against the risks of climate change” and is working to understand how to do so. Chairman Powell has also indicated a willingness to eventually join the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGSF) and has sent representatives to participate in NGFS meetings. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco hosted a conference on climate change in 2019, commissioning a series of papers. The Executive Vice President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Kevin Stiroh, delivered remarks on climate change and risk management in bank supervision at a March 4, 2020 event at Harvard Business School. Stiroh is also the co-chair of the recently established Task Force on Climate-Related Risk (TFCR) of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision which released its first report in April. Financial regulators in the US are closely following efforts of central banks and regulators in other countries to develop stress testing and disclosure requirements.

While the energy sector gets much of the limelight when it comes to climate change impacts, many other industries are already recognizing physical and transition risks from climate change. Infrastructure development, real estate, and insurance are areas that already have had to adjust to very real climate-related impacts. Recent research calls into question the future of the 30-year mortgage in many areas of the country. The FEMA flood maps that insurers, developers, and local governments rely on for planning purposes and pricing risk don’t fully reflect expected climate risk. Some insurers and even some state governments have started to develop their own sea level rise and flooding data with more up-to-date climate science and projections.

These are just a few examples of how climate change is already impacting areas of law not strictly considered environmental.

Beyond independent financial regulators, the federal government is not currently working to integrate climate change risks into legal frameworks. The current administration instead has focused on preventing better integration of the collective scientific knowledge on climate change into federal regulatory structures. It has consistently worked to rollback existing environmental standards , with a particular emphasis on regulations designed to lessen the output of greenhouse gases. Many regulatory proposals in the last few years have incorporated legal interpretations designed to limit the federal government’s authority to regulate around climate change and environmental protections. In some instances, this administration has short circuited climate-conscious efforts in the private sector by rolling back regulations they have already complied with or voiced support for.

Even without new regulations, your area of practice will be impacted by climate change. As lawyers, we tend to focus most on new legislation and regulation. But lawyers need to be aware of how climate change is impacting their clients in other ways and how applicable legal standards may change even where new statutes or regulations have not materialized.

Companies you represent face changing risk exposures and financial outcomes. Many of our laws have legal standards that evolve as information comes to light such that courts will eventually see them differently even absent new regulation. For example, what courts consider material to an investor’s decisionmaking in securities law will shift as more investors incorporate climate change risk information into their ordinary course of business.

Climate change is already affecting a wide range of legal practices and its impacts on the law are only just beginning to be felt. In-house attorneys and outside counsel must have a grasp of how climate change will impact the businesses they work with, their supply chains, the contracts they draw up, their internal risk management and audit procedures, and board level governance.

When I was in private practice, I did not consider myself a “climate change attorney.” I was a typical environmental law practice attorney focused on individual client needs with little time to step back and consider broader trends that might eventually impact client outcomes. But each of us must start considering how broader trends related to climate change impacts the law we practice or we run the risk of these forces changing legal standards before we even notice.

As a trusted advisor, you are tasked with helping clients see these trends coming. You will need to help them understand the potential risks and liabilities associated with climate change—whether from physical impacts on their operations, changing expectations of shareholders and regulators, or evolving legal standards.

Climate change will affect your practice and environmental attorneys need your help in analyzing how it impacts your area of practice.

[1] Read more about how this is happening for climate change information in The Reasonable Investor and Climate-Related Information: Changing Expectations for Financial Disclosures , published in the February 2020 edition of the Environmental Law Reporter.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- About Journal of Environmental Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- JEL Workshops

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. the european climate law and procedural climate governance, 3. medium- and long-term targets, 4. monitoring and evaluation, 5. climate policy integration, 6. scientific expert advice, 7. access to justice, 8. inclusiveness and public participation, 9. conclusions.

- < Previous

The European Climate Law: Strengthening EU Procedural Climate Governance?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Kati Kulovesi, Sebastian Oberthür, Harro van Asselt, Annalisa Savaresi, The European Climate Law: Strengthening EU Procedural Climate Governance?, Journal of Environmental Law , Volume 36, Issue 1, March 2024, Pages 23–42, https://doi.org/10.1093/jel/eqad034

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In 2021, the European Union (EU) adopted the so-called European Climate Law (ECL), enshrining in law the 2050 climate-neutrality objective and upgraded 2030 emission reduction target. The ECL bears the hallmarks of what we term ‘procedural climate governance’, which comprises the regulatory frameworks, instruments, institutions and processes that shape substantive climate policies and their implementation. This article identifies seven key functions of procedural climate governance—target-setting; planning; monitoring and evaluation; climate policy integration; scientific expert advice; access to justice; and public participation—and uses these for critically assessing the ECL. We argue that while the ECL has significantly strengthened important aspects of EU procedural climate governance, further reforms are needed for the EU to develop and implement the substantive policies towards a climate-neutral and climate-resilient economy and society and to bolster public support and ownership of the transition. The upcoming reviews of the ECL and the Governance Regulation provide a critical opportunity for strengthening procedural climate governance in the EU.

In April 2021, the European Union (EU) adopted a Regulation commonly known as the European Climate Law (ECL). 1 The ECL enshrines in law the goals for the EU to become climate neutral by 2050 and to reduce its net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 55% from 1990 levels by 2030. The ECL—alongside the Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action (Governance Regulation) 2 —establishes a regulatory framework for the implementation and further development of climate policy in the EU, with a view to achieving the Union’s mid- to long-term climate targets.

Like most national framework climate laws, the ECL bears the hallmarks of what we term ‘procedural climate governance’. This comprises the instruments, institutions and processes that shape substantive climate policies and their implementation. 3 Procedural climate governance consists of a range of elements, such as target-setting, planning and monitoring and evaluation. It also includes features related to the quality of climate governance, such as access to justice, inclusiveness and public participation, and independent scientific advice. Procedural climate governance therefore has the potential to strengthen the throughput legitimacy 4 of EU climate change law and help overcome what Fisher has criticised as the EU’s ‘linear’, output-oriented approach. 5 To the extent it is effective, procedural governance forms an essential part of a successful response to climate change by aligning governance structures with core features of the climate challenge, such as its long-term, dynamic, uncertain, complex and cross-sectoral nature. 6

Building on earlier work developing the concept of procedural climate governance, 7 this article identifies its seven key functions, and uses these as an analytical lens for critically assessing the ECL and its contribution to procedural climate governance in the EU. In doing so, the article seeks to improve understanding of the ‘largely uncharted legal territory’ of EU climate change law, 8 with a specific focus on the ECL, which—notwithstanding its importance as an overarching legal framework for the future development of EU climate change law—has thus far received limited scholarly attention. 9 Potential reasons for this limited scholarly attention to the ECL include its procedural focus, which adds a new dimension to EU climate change law and is possibly not yet fully understood by legal scholars. Our analysis focuses primarily on climate change mitigation governance, although the ECL also introduces elements of procedural climate governance for adaptation to climate change. 10

We start by discussing in Section 2 how and why the ECL—along with the Governance Regulation—constitutes the core of the EU’s legal framework for procedural climate governance. In Sections 3–8, we analyse the extent to which the ECL advances six functions of procedural climate governance, namely: target-setting (Section 3); monitoring and evaluation (Section 4); climate policy integration (Section 5); scientific expert advice (Section 6); access to justice (Section 7); and inclusiveness and public participation (Section 8) and conclusion (Section 9).

2.1 Procedural Climate Governance

As outlined above, the ECL develops the legal framework for what can be termed the EU’s procedural climate governance. The notion of procedural governance is related to the distinction between substantive and procedural policy measures. Whereas substantive climate policy instruments, such as the EU emissions trading system, aim to directly mitigate GHG emissions, procedural climate governance instead sets the overarching goals for substantive climate policy and puts in place the instruments, institutions and processes for planning, implementing, enforcing and adjusting substantive climate policies. 11 Procedural climate governance is closely related to throughput legitimacy, which relates to the quality of governance, notably with respect to transparency and accountability, as well as inclusiveness and openness. 12 As Fisher has argued, ‘ensuring that the challenges of climate change are met’ requires shifting the traditional emphasis away from the EU’s input and output legitimacy towards its throughput legitimacy, including ‘a focus on how disruption is managed as fairly as possible, on how disputes are resolved, and on how consensus is built’. 13

The growing importance of procedural climate governance is underscored by the proliferation of national framework laws on climate change, especially in Europe. 14 Following the example of the 2008 UK Climate Change Act, 15 EU Member States with framework climate laws now include Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Malta, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden. 16 Such national framework climate laws commonly incorporate elements of procedural climate governance, making national climate targets legally binding through domestic law 17 and establishing governance procedures and institutional responsibilities relating to climate policy planning, monitoring and reporting. Many such laws also include provisions for scientific advisory bodies, as well as for public participation, transparency and accountability. 18

Here, we identify seven key functions of procedural climate governance. 19 First, medium- and long-term targets play an important role in guiding the development of substantive climate policies, offering direction over a longer period and improving legal certainty. 20 In addition, they can play a critical role in ensuring that the global carbon budget is distributed fairly between generations and countries. Second, medium- and long-term climate policy planning is crucial in view of the long-term perspective needed to effectively respond to the climate crisis. Its main functions relate to aligning substantive policies with climate targets and for engaging the public and scientific experts in policy instrument choice and design. 21 Increasingly, planning must also consider the need for a just transition and any adverse and unequal socioeconomic consequences of climate policies on individuals and communities. 22 Third, arrangements for monitoring and evaluation of implementation —providing for enforcement where needed—are key for enabling climate governance to take stock of progress and ensuring that substantive policies are delivered. Related to this function are legal mandates and procedures for modifying and re-aligning substantive climate policies with climate targets in case of insufficient progress. Fourth, the integration of climate objectives into other policy areas (i.e., climate policy integration ) is important in view of the cross-sectoral nature of the climate change challenge and the whole-of-government approach needed to respond to it. 23 Fifth, scientific expert advice is essential for an objective evaluation of substantive climate policy options and for assessing progress made in the light of changing scientific insights. Sixth, mechanisms for holding policymakers to account, including through judicial means and by providing for access to justice , are important for determining the adequacy of climate policy goals and the effective implementation of climate policies. 24 Lastly, inclusiveness and meaningful public participation can be considered crucial for supporting the legitimacy and acceptance of climate policy. 25 This function also covers access to information and openness of the relevant policy processes as important aspects of transparency. 26

2.2 The ECL and the Governance Regulation as the Legal Framework for EU Procedural Climate Governance

To assess the contribution of the ECL to procedural climate governance in the EU, it is crucial to understand how the ECL and the Governance Regulation complement each other. To start with, the ECL is based on Article 192(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and solely addresses EU climate policy, whereas the Governance Regulation is based on both Articles 192(1) and 194(2) and addresses both climate and energy policy. Different competencies have been used because the Governance Regulation is closely related to the EU initiative known as the Energy Union, 27 and its key aims include ensuring the implementation of both the EU’s 2030 climate and energy targets. 28 The ECL, in turn, focuses on EU climate policy and is therefore based on environmental competence only.

Furthermore, the ECL primarily addresses the EU level and introduces obligations mainly for the Commission. By contrast, the Governance Regulation imposes several obligations directly on EU Member States, while also containing obligations for the Commission, especially to review and ensure adequate ambition and progress at the Member State and EU levels. Regarding the functions of procedural climate governance introduced in Section 2.1, the Governance Regulation focuses on planning, whereas the ECL mainly addresses EU climate targets, climate policy integration and scientific expert advice. The two instruments furthermore address different aspects of monitoring and evaluation, as well as inclusiveness and public participation, while neither addresses access to justice.

Having been described as an ‘umbrella regulation’ establishing a common governance system for EU climate and energy policy, 29 the Governance Regulation covers three of the functions of procedural climate governance. 30 On planning, it specifically requires EU Member States to prepare mid-term National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) every 10 years, and to update these every five years. 31 The current NECPs detail how each Member State intends to achieve its 2030 climate and energy targets and are being revised and updated in 2023/2024. Every 10 years, Member States must also prepare Long-Term Strategies (LTSs) covering at least the next 30 years. 32 In addition to various monitoring and reporting obligations for the Commission and Member States related to the EU’s internal climate and energy targets, the Governance Regulation addresses monitoring and evaluation by incorporating and amending the earlier Monitoring Mechanism Regulation 33 to ensure the EU’s compliance with the reporting obligations under the Paris Agreement. 34 Importantly, Member States must submit integrated national energy and climate progress reports (biennial progress reports), starting from 2023 and every two years thereafter. 35 In addition to mandating the Commission to review NECPs and issue related guidance to Member States, the Governance Regulation prescribes action to be taken by the Commission in response to insufficient ambition and progress by individual Member States or collectively. 36 The Governance Regulation also seeks to enhance inclusiveness and public participation at the Member State level. 37

As this article focuses on the ECL, the following sections analyse those five functions of procedural climate governance that the ECL either addresses exclusively (target-setting, climate policy integration, scientific expert advice) or in tandem with the Governance Regulation (monitoring and evaluation, inclusiveness and public participation). While the focus will be on the ECL, aspects of the Governance Regulation will, where relevant, also be discussed for a fuller understanding of the EU’s legal framework for procedural climate governance. Since planning is primarily addressed in the Governance Regulation, but not in the ECL, this function of procedural climate governance is not addressed further in this article. We also analyse access to justice, which is not covered by either the ECL or the Governance Regulation but is an important element of procedural climate governance (Section 7).

Target-setting is a key feature of procedural climate governance. Arguably, enshrining climate targets in legislation not only strengthens their credibility but it also offers some certainty and long-term perspective to industry and investors. 38 The ECL includes the EU’s 2050 climate-neutrality objective, an upgraded EU net emission reduction target for 2030, and a process for defining both the EU’s 2040 climate target and an indicative GHG emissions budget for 2030–2050.

3.1 Climate Neutrality by 2050

One of the key elements of the ECL is ‘a binding objective of climate neutrality in the Union by 2050’. 39 More concretely, GHG emissions and removals ‘shall be balanced within the Union at the latest by 2050, thus reducing emissions to net zero by that date’. 40 The target covers all GHG emissions and removals by sinks. In addition, the EU ‘shall aim to have negative emissions’ after 2050. 41

The ECL represents significant progress for procedural climate governance as the first legal instrument with a binding climate-neutrality objective for one of the world’s largest GHG emitters. The 2050 climate-neutrality objective might also align with the global net-zero goal in Article 4(1) of the Paris Agreement, depending, however, on how this somewhat opaque provision is interpreted, 42 including with respect to the highly contentious question of burden-sharing between countries.

It is less clear whether the EU’s 2050 climate-neutrality objective aligns with the collective 1.5/2°C temperature goal in Article 2(1)(a) of the Paris Agreement. While the 1.5°C goal is aspirational, it forms the current benchmark for countries’ mitigation efforts, 43 and the reference point for defining countries’ equitable share of the remaining global carbon budget. Accordingly, recent advice by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (ESABCC; see Section 6)—mandated by the ECL—suggests that the EU’s fair share of the remaining global carbon budget for the 1.5°C goal from the start of 2020 based on an equal per capita allocation of emissions would amount to 20–25 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Gt CO 2 -eq.). 44 However, the Advisory Board adds that ‘[d]ividing the same budget using approaches informed by other ethical principles (such as the ability to pay or historical emissions) produces estimates of the EU share, which in some cases suggest that the EU has already used its fair share of the global carbon budget’. 45

Notably, the ECL defers to future decision-making to determine to what extent climate neutrality in the EU will be achieved through emission reductions, and how much it will rely on natural (e.g., forests, soil, wetlands) or artificial sinks (e.g., direct air capture or bioenergy with carbon capture and storage). This critical issue is to be covered by the Commission’s 2024 proposal for an indicative EU carbon budget for 2030–2050 (see Section 3.2). 46 The delay in resolving this issue is concerning given the rapid drop in the EU forest sink, which is projected to further decrease under current management practices. 47

During the law-making process, the European Parliament proposed including in the ECL an obligation for each Member State to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 at the latest. 48 However, this proposal was unsuccessful and the ECL does not, in its current form, specify how individual Member States are expected to contribute to the collective climate-neutrality objective. Instead, the ECL merely emphasises ‘the importance of promoting both fairness and solidarity among Member States and cost-effectiveness in achieving this objective’. 49 At the time of writing, 13 Member States had a self-defined climate-neutrality target enshrined in national legislation; 50 six had set such targets through policy documents; 51 and eight Member States had no national climate-neutrality targets. 52 The Commission has estimated that the Member States’ national targets in 2023 leave a gap of eight percent to net-zero emissions by 2050. 53 To close this important gap in the EU’s procedural climate governance framework, clarity is needed on contributions by individual Member States and/or the three key climate pillars of EU climate law, namely emissions trading, effort sharing, and land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). This issue should be considered in the reviews of the ECL and the Governance Regulation due in the first half of 2024. 54

3.2 Intermediate Targets

The ECL increases the EU’s 2030 net GHG emission reduction target from at least 40% to at least 55% compared to 1990 levels. The Parliament had proposed including in the ECL a 60% emission reduction target for 2030. The final compromise 55 was a 2030 target equal to a net emission reduction of at least 57%. This would be achieved by limiting the contribution of net removals to the 55% target to 225 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, while aiming for actual net removals of 310 million tonnes. The EU has subsequently passed legislation aiming to increase net removals in the LULUCF sector from 280 to 310 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030. 56 However, due to the inclusion of removals from the LULUCF sector, the EU’s actual emission reduction target for 2030 amounts to only 52.8%, 57 so that the EU’s revised 2030 target relies more on the LULUCF sector than its initial 2030 target.

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and researchers have criticised the EU’s strengthened 2030 target enshrined in the ECL for being insufficient. The NGO Climate Action Tracker suggests that the EU’s mitigation target for 2030 needs substantial improvement to be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C. 58 Gheuens and Oberthür argue that an EU target between 60–70% would have been ‘an ideal range’. 59 Similarly, a report by Climate Analytics – one of the organisations behind Climate Action Tracker – suggests that the EU mitigation target can ‘feasibly’ be increased to 61–73% below 1990 levels by 2030, excluding LULUCF. 60

From the perspective of international fairness, the EU would arguably need to do even more. As another Climate Analytics report claims, the EU’s target ‘would result in warming between 2 and 3°C (with a 66% probability) by 2100 if all countries were to set targets of an equivalent fair share level of mitigation ambition’. 61 Following this logic, they posit that the EU should achieve emission reductions of at least 93% below 1990 levels (again, excluding LULUCF) by 2030. 62 Another study on ‘fair shares’ suggests that the EU’s (and other developed states’) emissions should be net zero or net-negative by 2030. 63 Hence, the EU’s strengthened 2030 target as enshrined in the ECL is an important, yet still insufficient step towards an internationally and intergenerationally fair implementation of the Paris Agreement.

The ECL also outlines the process for setting the EU’s 2040 target. To this end, the Commission is required to prepare a proposal to amend the ECL within six months after the first global stocktake under the Paris Agreement, 64 which concluded at the end of 2023. 65 When tabling this proposal, the Commission is required to specify, in a separate report, an indicative EU GHG budget for 2030–2050, as well as the related methodology. 66 In making its proposal, the Commission has to take a wide range of considerations into account, including not only familiar criteria such as environmental effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, but also broader considerations, such as costs of inaction and the ‘need to ensure a just and socially fair transition for all’. 67 At the time of writing, the Commission is expected to release a communication with options for the 2040 target in early 2024. As European Parliament elections are due in June 2024, and a new Commission would take over soon after, the actual legislative proposal would likely be tabled only after the new Commission has assumed office. 68

Carbon budgets have been described as a useful tool to gauge the consistency of climate targets with global temperature goals. 69 The EU’s indicative carbon budget is expected to help evaluate whether the ECL targets represent a fair and equitable contribution to the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the 1.5°C goal. After ‘considering multiple dimensions of fairness and feasibility’, the ESABCC suggested an emission reduction of 90–95% from 1990 levels by 2040 and an EU GHG emission budget of 11 to 14 Gt CO 2 -eq. 70

It can be questioned whether the ECL’s current lack of a clear emission trajectory from 2030 to 2050 is consistent with the principle of intergenerational equity. In this respect, the ECL bears similarities with the first German Climate Change Act, which was declared unconstitutional precisely because it did not clearly outline steps towards Germany’s 2050 carbon-neutrality goal beyond 2030. 71 According to the German Constitutional Court, one generation ‘must not be allowed to consume large portions of the [GHG] budget while bearing a relatively minor share of the reduction effort, if this would involve leaving subsequent generations with a drastic reduction burden and expose their lives to serious losses of freedom’. 72 The ECL, however, does not list either international or intergenerational equity among the issues that the Commission must take into account when proposing the EU’s 2040 target and indicative carbon budget. 73 Nevertheless, the ESABCC’s consideration of ‘multiple dimensions of fairness and feasibility’ shows that such considerations can and should be taken into account in the target-setting process. 74

Provisions on monitoring and evaluation of implementation of substantive climate policies, and legal requirements for their enforcement and/or adjustment in cases of insufficient progress, are crucial features of procedural climate governance. Ultimately, the role of such provisions is to ensure that climate policies deliver, and that climate targets are met. Otherwise, governments could be tempted to prioritise short-term interests and delay difficult political decisions on concrete climate policies needed to achieve climate targets. 75 As noted in Section 2, the Governance Regulation includes provisions on monitoring and reporting, as well as on action to be taken by the Commission in case of insufficient progress towards the EU’s 2030 climate and energy targets. The ECL introduces additional processes for the Commission to track progress towards the ECL objectives and to respond to lack of progress. These new processes include assessing the Member States’ collective progress towards the ECL’s 2050 climate-neutrality and adaptation objectives as well as the consistency of EU measures with these objectives. The Commission must also assess Member States’ national measures in light of the ECL objectives.

4.1 Assessing EU-Level Measures

The Commission must regularly assess Member States’ collective progress towards the ECL’s objectives, 76 as well as the consistency of EU measures with these objectives. 77 The first such assessments were presented in the autumn of 2023, with further rounds due every five years thereafter. 78 The ECL progress assessments are linked with, and complement, the relevant annual assessments of progress towards the 2030 climate and energy targets under the Governance Regulation, and the conclusions of the collective progress assessment will be published together with the State of the Energy Union report that the Commission must prepare under the Governance Regulation. 79

While these progress and consistency assessments promise added value, a shortcoming in the ECL is that it does not spell out crucial details, such as the indicators and methodology to be used by the Commission in these assessments, the scope and focus of the consistency assessment, and the role of the ESABCC (see Section 6). 80 Indeed, the Commission’s first Climate Action Progress Report of October 2023 also identifies the need for more detailed monitoring ‘to better highlight areas where progress is lacking or more action is needed’. 81

If the Commission concludes that insufficient progress towards the ECL’s objectives has been made, or that Union measures are inconsistent with the ECL objectives, it must ‘take the necessary measures in accordance with the Treaties’. 82 In practice, this could mean proposing new measures. However, neither the meaning of ‘necessary measures’ nor the threshold for the Commission to propose additional measures has been specified in the ECL. In light of this, as detailed in Section 7, a shortcoming in the ECL is that it does not include specific accountability mechanisms – such as the possibility to seek judicial review – to challenge the conclusions from the Commission’s progress and consistency assessments and/or the responses taken to address inadequate progress or inconsistency.

4.2 Assessing Member States’ National Measures

By 30 September 2023, and every five years thereafter, the Commission must also assess the consistency of Member States’ national measures with the ECL’s climate-neutrality and adaptation objectives. The assessment will be based on NECPs, LTSs and biennial progress reports. 83

If the Commission finds a Member State’s measures to be inconsistent with either of the ECL’s two objectives, it may issue recommendations to the Member State. 84 However, the Commission must first give ‘due consideration’ to Member States’ collective progress towards the ECL goals (see Section 4.1). As discussed in Section 3.1, the ECL does not spell out individual Member States’ contributions to the climate-neutrality objective. In practice therefore, the Commission will need to give concrete meaning to the terms ‘fairness’, ‘solidarity among Member States’ and ‘cost-effectiveness’ in Article 2(2) of the ECL. This gap may also be addressed in the review of the ECL, although this review comes too late for the first assessment round.

Within six months of receiving the Commission’s recommendations, a Member State must let the Commission know how it intends to address these ‘in a spirit of solidarity between Member States and the Union and between Member States’. 85 The Member States’ biennial progress reports prepared under the Governance Regulation must also explain how they have addressed the Commission’s recommendations. 86 If a Member State decides not to address the recommendations or a substantial part thereof, it must provide its reasoning in the same report. 87

The ECL’s five-yearly consistency assessments of Member States’ measures are complementary to progress assessments under the Governance Regulation. The assessments under the Governance Regulation require the Commission to assess every two years each Member State’s progress towards the objectives set out in its NECP. 88 In case of insufficient progress, the Commission must issue recommendations to the Member State in question. 89 The findings of the first such assessment in 2023 are described below (Section 4.3).

Both the Governance Regulation and the ECL thus rely mainly on the Commission’s recommendations for promoting compliance. 90 Under the ECL, the Commission has discretion in issuing recommendations, whereas the Governance Regulation requires the Commission to do so whenever it finds a Member State making insufficient progress. The Commission’s recommendations to Member States have not been particularly effective in the context of the European Semester 91 —an annual process through which the EU coordinates and monitors budgetary, fiscal, economic and social policies and creates a space for discussing these between the EU institutions and Member States. 92 The same concern may be formulated regarding the effectiveness of the Commission recommendations under the ECL and Governance Regulation.

In assessing enforcement-related provisions in the ECL and Governance Regulation, it must be taken into account that additional means of judicial enforcement exist in EU law. The Commission may, for example, initiate infringement procedures against Member States breaching their EU law obligations, including those under the ECL and the Governance Regulation. Indeed, in September 2022, the Commission started infringement procedures against Bulgaria, Ireland, Poland and Romania for not complying with their obligation to submit LTSs under the Governance Regulation. The Commission may also initiate infringement action against Member States for lack of compliance with substantive climate policy obligations. In addition to enforcement action by the Commission, citizens may also seek to challenge inaction through EU or Member State courts, although this is subject to important limitations, as will be discussed in Section 7.

The possibility of infringement procedures under general EU law therefore complements in an important way the specific enforcement-related provisions in the ECL and Governance Regulation. However, recourse to infringement also has limitations: implementation of EU environmental law remains generally rather weak and enforcement action by the Commission has been described as too slow. 93

4.3 Implementing the Commission Assessments

The Commission’s assessments of EU and national measures’ progress on and consistency with the ECL objectives play a key role in ensuring that the ECL’s objectives are met. The details of these assessments, including their factual basis and indicators to be used to measure progress, are therefore crucial. The ECL contains a provision defining elements that are common to the various Commission assessments. While the ECL provides some guidance on the assessment of Member States’ collective progress and consistency of collective and individual Member States’ measures with the ECL targets, it leaves many details to be elaborated by the Commission. 94

The starting point for the Commission’s first and second climate-neutrality progress assessments, which are due by 2023 and 2028 respectively, is an ‘indicative linear trajectory’ linking the EU’s 2030, 2040 (once adopted) and 2050 climate targets. 95 From the next assessment (due by 2033) onwards, assessments must take a linear trajectory, taking the 2040 and 2050 targets as its starting and end points respectively. 96 The European Environment Agency (EEA) is to assist the Commission in preparing the assessments. 97 The ECL lists several information sources that the Commission must use as a basis for its assessments, including: information submitted and reported under the Governance Regulation; reports by the EEA, the ESABCC and the Commission’s Joint Research Centre; scientific information, including the latest reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; and supplementary information on environmentally sustainable investment by the EU or the Member States, such as that provided under the Taxonomy Regulation. 98

However, the ECL lacks important details on methodologies and indicators that could help ensure the quality of the Commission assessments, leading some commentators to call on the Commission to start a transparent process to develop the monitoring of progress. 99 The role of the newly created ESABCC in the assessments should also be considered and potentially strengthened (see Section 6). 100

In practice, the first Commission progress assessment published in October 2023 identified the need for both better monitoring and additional mitigation measures to cut around 1,600 million tonnes of CO 2 equivalent (or 34 percentage points) to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. 101 Concerning further action, the Commission emphasised its plans to publish in early 2024 a communication on the EU 2040 climate target, setting a path from 2030 to net-zero emissions in 2050. 102 This, according to the Commission, ‘will provide the information needed to ensure that measures and investments to implement the EU’s 2030 targets are also well aligned with the pathways to climate neutrality by 2050’ and ‘keep progress on track to climate neutrality’. 103

Climate policy integration is an important element of procedural climate governance. 104 Accordingly, all sectors and policy areas must be aligned with, and contribute to, the achievement of the climate-neutrality objective. Conceptually, the idea of climate policy integration is closely related to the whole-of-government approach, which includes the ’aspiration to achieve horizontal and vertical coordination’, ‘eliminate situations in which different policies undermine each other’ and create ‘synergies by bringing together different stakeholders in a particular policy area’. 105 For climate policy integration to take place, different public authorities must not work in siloes, but institutional mandates and processes must be created for considering different sectors and policy areas more holistically in light of the ECL’s objectives and targets. The ECL makes important advances in developing the EU’s procedural climate governance in this respect while leaving significant room for further improvement.

In particular, the ECL requires the Commission to assess whether any draft EU measures or legislative proposals, including budget proposals, are consistent with the climate-neutrality objective, the 2030 and 2040 climate targets, and the adaptation objective. 106 The Commission must then ‘endeavour’ to align all measures it proposes with the objectives of the ECL 107 and explain the reasons for any non-alignment. 108 The ECL thus creates an important mandate and procedural mechanism for strengthening the integration of climate considerations into all areas of EU law and policy. 109 The relevant sectors and policy areas include energy, industry, transport, agriculture, forestry, and buildings, but also finance, trade and general foreign policy. 110

The quinquennial consistency assessments of EU and national measures discussed in Section 4 also have potential for enhancing climate policy integration. Their potential depends on how the Commission will define the scope of its assessments, and especially on what policies and measures beyond climate and energy policy it will consider. The ECL’s requirement that any recommendations that the Commission may issue to Member States ‘shall be complementary to the latest country-specific recommendations issued in the context of the European Semester’ 111 provides a clear opening in this respect.

Overall, however, policy integration in the ECL falls short of requiring ‘principled priority’ for climate policy. 112 The Commission’s impact assessments will continue to be made public only at the stage when the measure or proposal in question is published. 113 A Parliament proposal to oblige the Commission in the ECL to make the impact assessment immediately and directly available to the public was rejected. 114 The public will have no opportunity to comment on the impact assessment before the Commission has finalised its proposal or measure. 115 Furthermore, the ECL lacks criteria for assessing the consistency or alignment of legislative proposals with the climate-neutrality and adaptation objectives. It provides no safeguards for preventing legislative or budgetary proposals from being inconsistent with the ECL objectives. 116 In this context, the ECL also fails to codify, let alone elaborate on, the European Green Deal’s pledge to ‘do no harm’ 117 or require maximising synergies between climate policy and other policy areas.

Various national framework climate laws establish scientific expert bodies to offer advice to policymakers. Such bodies are important for ensuring that scientific and expert knowledge inform climate policymaking and implementation. Depending on their mandate, these bodies can play different formal and informal roles, including those of watchdog, knowledge broker and convenor. 118 They arguably add ‘unique value’ 119 to climate governance by increasing ‘the transparency and legitimacy of policymaking, contributing to greater political and public support’. 120 At least some of these bodies have been ‘instrumental in providing the analytical basis for more ambitious climate action’. 121 At the same time, studies also suggest that there are limits to what these bodies can achieve, and warnings issued by an advisory body, e.g., that a country is not on course to meet its targets, may go unheeded. 122

The ECL establishes a climate expert advisory body, the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change. 123 It also invites Member States to establish their own national climate advisory bodies. 124 The ESABCC is composed of 15 members chosen based on merit, including scientific excellence, with a view to covering ‘a broad range of relevant disciplines’. 125 There is a requirement for geographical and gender balance. 126 The members are appointed for a four-year term, which can be renewed once. 127 The Advisory Board members are independent of the Member States and of the EU institutions. 128 The ESABCC is supported by a secretariat hosted by the EEA, which has a budget to cover up to 14 staff, as well as €500,000 for other tasks. 129

The ESABCC’s mandate is broad and general. Among others, it is tasked with considering the latest scientific insights, and providing scientific advice and issuing reports on existing and proposed EU measures, climate targets and indicative GHG budgets, and their coherence with the objectives of the ECL and the Paris Agreement. 130 Its other tasks include identifying actions and opportunities to achieve the EU climate targets, raising awareness of climate change and its impacts, and stimulating dialogue and cooperation between scientific bodies within the Union. 131 The Advisory Board is mandated to set out its own work programme while consulting the Management Board of its host institution, the EEA. 132

The ESABCC has the potential to strengthen EU climate policy. Its independence from the EU institutions and the Member States enables it to provide impartial advice. Due to its general mandate, the Advisory Board can exercise discretion in identifying critical priorities. It has already provided advice to the Commission on the 2040 EU target and the 2030–2050 carbon budget, recommending a reduction of GHG emissions by 90–95% by 2040 (from 1990 levels) (see Section 3.2). 133 Its 2023 work programme further indicates that the Board plans to engage with a range of issues, such as mitigation options for agriculture, land use and forestry, and their links with adaptation to climate change. 134

However, the ESABCC’s role and mandate could be strengthened by identifying entry points in the EU climate policy process where the Advisory Board’s input would be required —in combination with an obligation to take its input into consideration. A comparative analysis of national advisory bodies points to the added value of a clear mandate, with specific roles and responsibilities. 135 For example, the UK Climate Change Committee’s specific tasks include advising the UK Government in the preparation of carbon budgets, and in both the UK and New Zealand there is a legal obligation for the government to respond to advice given by the respective advisory bodies. 136 By contrast, the ECL does not include an obligation for the Commission to respond to (or heed) the recommendations issued by the ESABCC. The ECL merely lists the Advisory Board’s latest reports among the materials that the Commission must consider when proposing the EU’s 2040 target and the 2030–2050 indicative carbon budget, conducting the five-yearly progress and consistency assessments, and reviewing the operation of the ECL following each global stocktake under the Paris Agreement. 137 Without a clear mandate to engage in critical aspects of the policy process, the realisation of the ESABCC’s potential to enhance the quality and ambition of EU climate policy largely depends on how the Advisory Board will define its agenda, and how its recommendations and advice will be received by EU policymakers. For these reasons, the ESABCC’s mandate is an issue that merits further consideration during the forthcoming review of the ECL. 138 The Commission’s five-yearly progress and consistency assessments under the ECL are obvious places where independent scientific input would seem beneficial, including an obligation to take this input into account. 139

Framework climate laws, at least in theory, can be used to hold governments to account for adopting sufficiently ambitious climate policies and their effective implementation. 140 However, evidence is emerging, including from the UK, 141 Ireland 142 and Finland, 143 that national climate framework laws are not necessarily being effectively implemented and may lack adequate accountability mechanisms. Against this backdrop, access to justice is a critical element of procedural climate governance and throughput legitimacy. As parties to the Aarhus Convention, 144 the EU and its Member States have committed to ensuring access to justice in environmental matters. In practice, however, citizens’ access to the EU courts remains constrained, 145 whereas access to Member States’ national courts varies significantly. 146

Litigation in support of stronger climate action (so-called ‘strategic’ climate litigation) has significantly increased across the EU in recent years. 147 Some EU Member States’ courts have delivered judgements granting the claims of applicants demanding more ambitious climate action. 148 The same surge of litigation has not happened before the courts of the EU, where the majority of climate law-based lawsuits have concerned the implementation of the Emissions Trading Directive. 149 Only few strategic lawsuits have been filed before the courts of the EU. 150 Some of the early cases— Carvalho 151 and Sabo 152 —were rejected at the admissibility stage, as the Court deemed that the applicants had no standing to challenge EU law measures of general application.

The 2021 revision of the so-called Aarhus Regulation 153 has bolstered the powers of NGOs and some individuals to request an ‘internal review’—a procedure enabling them to ask EU institutions to review their own decisions on environmental matters, and eventually bring a case before the Court of Justice of the EU. NGOs have recently relied on this procedure to request the EU courts to annul the decisions to include forest biomass in and list natural gas and nuclear energy as sustainable investment under, the Taxonomy Regulation. 154

The ECL could have further strengthened the hand of climate litigants, by including an explicit provision enabling citizens and other relevant stakeholders, such as NGOs, to question, for example, the findings of the Commission’s assessments of progress towards climate neutrality or its proposed EU-level action following such assessments (or the lack thereof). During the negotiations of the ECL, the NGO ClientEarth highlighted the need to ensure accountability of the EU institutions and the Member States, should they fail to meet the ECL targets and objectives. 155 It also proposed inserting a provision in the Governance Regulation giving citizens access to the courts of Member States to challenge the substantive or procedural legality of NECPs and LTSs. 156 The Parliament made a similar proposal during the trilogue negotiations. 157