Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Enhancing Scientific Thinking Through the Development of Critical Thinking in Higher Education

- First Online: 22 September 2019

Cite this chapter

- Heidi Hyytinen 3 ,

- Auli Toom 3 &

- Richard J. Shavelson 4

1486 Accesses

27 Citations

3 Altmetric

Contemporary higher education is committed to enhancing students’ scientific thinking in part by improving their capacity to think critically, a competence that forms a foundation for scientific thinking. We introduce and evaluate the characteristic elements of critical thinking (i.e. cognitive skills, affective dispositions, knowledge), problematising the domain-specific and general aspects of critical thinking and elaborating justifications for teaching critical thinking. Finally, we argue that critical thinking needs to be integrated into curriculum, learning goals, teaching practices and assessment. The chapter emphasises the role of constructive alignment in teaching and use of a variety of teaching methods for teaching students to think critically in order to enhance their capacity for scientific thinking.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Fostering scientific literacy and critical thinking in elementary science education.

Critical Thinking

A Model of Critical Thinking in Higher Education

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., et al. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 1102–1134. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308326084 .

Article Google Scholar

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses . Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

Ayala, C. C., Shavelson, R. J., Araceli Ruiz-Primo, M., Brandon, P. R., Yin, Y., Furtak, E. M., et al. (2008). From formal embedded assessments to reflective lessons: The development of formative assessment studies. Applied Measurement in Education, 21 (4), 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/08957340802347787 .

Badcock, P. B. T., Pattison, P. E., & Harris, K.-L. (2010). Developing generic skills through university study: A study of arts, science and engineering in Australia. Higher Education, 60 (4), 441–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-010-9308-8 .

Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R., & Daniels, L. B. (1999). Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31 (3), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202799183133 .

Bailin, S., & Siegel, H. (2003). Critical thinking. In N. Blake, P. Smeyers, R. Smith, & P. Standish (Eds.), The Blackwell guide to the philosophy of education (pp. 181–193). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Banta, T., & Pike, G. (2012). Making the case against—One more time . Occasional Paper #15. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment. Retrieved from http://learningoutcomesassessment.org/documents/HerringPaperFINAL.pdf .

Barrie, S. C. (2006). Understanding what we mean by the generic attributes of graduates. Higher Education, 51 (2), 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6384-7 .

Barrie, S. C. (2007). A conceptual framework for the teaching and learning of generic graduate attributes. Studies in Higher Education, 3 (4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701476100 .

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83 (2), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415 .

Bereiter, C. (2002). Education and mind in the knowledge age . Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2009). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (3rd ed.). Berkshire, England: SRHE and Open University Press.

Bok, D. (2006). Our underachieving colleges. A candid look at how much students learn and why they should be learning more . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brooks, R., & Everett, G. (2009). Post-graduation reflections on the value of a degree. British Educational Research Journal, 35 (3), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920802044370 .

Denton, H., & McDonagh, D. (2005). An exercise in symbiosis: Undergraduate designers and a company product development team working together. The Design Journal, 8 (1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.2752/146069205789338315 .

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think . Boston, MA: D. C. Heath & Co.

Book Google Scholar

Dewey, J. (1941). Propositions, warranted assertibility, and truth. The Journal of Philosophy, 38 (7), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.2307/2017978 .

Dunlap, J. (2005). Problem-based learning and self-efficacy: How a capstone course prepares students for a profession. Educational Technology Research and Development, 53 (1), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02504858 .

Ennis, R. (1991). Critical thinking: A streamlined conception. Teaching Philosophy, 14 (1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil19911412 .

Ennis, R. (1993). Critical thinking assessment. Theory into practice, 32 (3), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849309543594 .

Evens, M., Verburgh, A., & Elen, J. (2013). Critical thinking in college freshmen: The impact of secondary and higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 2 (3), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v2n3p139 .

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED315423). Newark, DE: American Philosophical Association.

Fischer, F., Chinn, C. A., Engelmann, K., & Osborne, J. (Eds.). (2018). Scientific reasoning and argumentation: The roles of domain-specific and domain-general knowledge . New York, NY: Routledge.

Fisher, A. (2011). Critical thinking: An introduction . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gillies, R. (2004). The effects of cooperative learning on junior high school students during small group learning. Learning and Instruction, 14 (2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(03)00068-9 .

Greiff, S., Wüstenberg, S., Csapó, B., Demetriou, A., Hautamäki, J., Graesser, A., et al. (2014). Domain-general problem solving skills and education in the 21st century. Educational Research Review, 13, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.10.002 .

Halpern, D. F. (2014). Thought and knowledge (5th ed.). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Healy, A. (Ed.). (2008). Multiliteracies and diversity in education . Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Helle, L., Tynjälä, P., & Olkinuora, E. (2006). Project-based learning in post-secondary education—Theory, practice and rubber sling shots. Higher Education, 51 (2), 287–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6386-5 .

Hmelo-Silver, C. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16 (3), 235–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3 .

Hofstein, A., Shore, R., & Kipnis, M. (2004). Providing high school chemistry students with opportunities to develop learning skills in an inquiry-type laboratory—A case study. International Journal of Science Education, 26 (1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069032000070342 .

Holma, K. (2015). The critical spirit: Emotional and moral dimensions of critical thinking. Studier I Pædagogisk Filosofi, 4 (1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.7146/spf.v4i1.18280 .

Holma, K., & Hyytinen, H. (equal contribution) (2015). The philosophy of personal epistemology. Theory and Research in Education , 13 (3), 334 – 350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878515606608 .

Hopmann, S. (2007). Restrained teaching: The common core of Didaktik. European Educational Research Journal, 6 (2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2007.6.2.109 .

Hyytinen, H. (2015). Looking beyond the obvious: Theoretical, empirical and methodological insights into critical thinking (Doctoral dissertation). University of Helsinki, Studies in Educational Sciences 260. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/154312/LOOKINGB.pdf?sequence=1 .

Hyytinen, H., Löfström, E., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2017). Challenges in argumentation and paraphrasing among beginning students in educational science. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61 (4), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1147072 .

Hyytinen, H., Nissinen, K., Ursin, J., Toom, A., & Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2015). Problematising the equivalence of the test results of performance-based critical thinking tests for undergraduate students. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 44, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.11.001 .

Hyytinen, H., & Toom, A. (2019). Developing a performance assessment task in the Finnish higher education context: Conceptual and empirical insights. British Journal of Educational Psychology , 89 (3), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12283 .

Hyytinen, H., Toom, A., & Postareff, L. (2018). Unraveling the complex relationship in critical thinking, approaches to learning and self-efficacy beliefs among first-year educational science students. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.08.004 .

Jenert, T. (2014). Implementing-oriented study programmes at university: The challenge of academic culture. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung , 9 (2), 1–12. Retrieved from https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/publications/230455 .

Krolak-Schwerdt, S., Pitten Cate, I. M., & Hörstermann, T. (2018). Teachers’ judgments and decision-making: studies concerning the transition from primary to secondary education and their implications for teacher education. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, M. Toepper, H. A. Pant, C. Lautenbach, & C. Kuhn (Eds.), Assessment of learning outcomes in higher education—Cross-national comparisons and perspectives (pp. 73–101). Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_5 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Kuhn, D. (2005). Education for thinking . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Marton, F., & Trigwell, K. (2000). Variatio est mater studiorum. Higher Education Research & Development, 19 (3), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360020021455 .

Mills-Dick, K., & Hull, J. M. (2011). Collaborative research: Empowering students and connecting to community. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 17 (4), 381–387. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182140c2f .

Muukkonen, H., Lakkala, M., Toom, A., & Ilomäki, L. (2017). Assessment of competences in knowledge work and object-bound collaboration during higher education courses. In E. Kyndt, V. Donche, K. Trigwell, & S. Lindblom-Ylänne (Eds.), Higher education transitions: Theory and research (pp. 288–305). London: Routledge.

Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive psychology . New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Niiniluoto, I. (1980). Johdatus tieteenfilosofiaan . Helsinki: Otava.

Niiniluoto, I. (1984). Tieteellinen päättely ja selittäminen . Helsinki: Otava.

Niiniluoto, I. (1999). Critical scientific realism . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Oljar, E., & Koukal, D. R. (2019, February 3). How to make students better thinkers. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-to-Make-Students-Better/245576 .

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2008). The thinker’s guide to scientific thinking: Based on critical thinking concepts and principles . Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Phielix, C., Prins, F. J., Kirschner, P. A., Erkens, G., & Jaspers, J. (2011). Group awareness of social and cognitive performance in a CSCL environment: Effects of a peer feedback and reflection tool. Computers in Human Behavior, 27 (3), 1087–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.024 .

Rapanta, C., Garcia-Mila, M., & Gilabert, S. (2013). What is meant by argumentative competence? An integrative review of methods of analysis and assessment in education. Review of Educational Research, 83 (4), 483–520. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313487606 .

Ruiz-Primo, M., Schultz, S. E., Li, M., & Shavelson, R. J. (2001). Comparison of the reliability and validity of scores from two concept-mapping techniques. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38 (2), 260–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2736(200102)38:2%3c260:AID-TEA1005%3e3.0.CO;2-F .

Samarapungavan, A. (2018). Construing scientific evidence: The role of disciplinary knowledge in reasoning with and about evidence in scientific practice. In F. Fischer, C. A. Chinn, K. Engelmann, & J. Osborne (Eds.), Scientific reasoning and argumentation: The roles of domain-specific and domain-general knowledge (pp. 56–76). New York, NY: Routledge.

Segalàs, J., Mulder, K. F., & Ferrer-Balas, D. (2012). What do EESD “experts” think sustainability is? Which pedagogy is suitable to learn it? Results from interviews and Cmaps analysis gathered at EESD 2008. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 13 (3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371211242599 .

Shavelson, R. J. (2010a). On the measurement of competency. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training , 2 (1), 41–63. Retrieved from http://ervet.ch/pdf/PDF_V2_Issue1/shavelson.pdf .

Shavelson, R. J. (2010b). Measuring college learning responsibly: Accountability in a new era . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Shavelson, R. J. (2018). Discussion of papers and reflections on “exploring the limits of domain-generality”. In F. Fischer, C. A. Chinn, K. Engelmann, & J. Osborne (Eds.), Scientific reasoning and argumentation: The roles of domain-specific and domain-general knowledge (pp. 112–118). New York, NY: Routledge.

Shavelson, R. J., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., & Mariño, J. (2018). International performance assessment of learning in higher education (iPAL): Research and development. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, M. Toepper, H. A. Pant, C. Lautenbach, & C. Kuhn (Eds.). Assessment of learning outcomes in higher education—Cross-national comparisons and perspectives (pp. 193–214). Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_10 .

Siegel, H. (1991). The generalizability of critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 23 (1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.1991.tb00173.x .

Strijbos, J., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2015). Criteria and standards of generic competences at bachelor degree level: A review study. Educational Research Review, 14, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.001 .

Tomperi, T. (2017). Kriittisen ajattelun opettaminen ja filosofia. Pedagogisia perusteita. Niin & Näin , 4 (17), 95–112. Retrieved from https://netn.fi/artikkeli/kriittisen-ajattelun-opettaminen-ja-filosofia-pedagogisia-perusteita .

Toom, A. (2017). Teacher’s professional competencies: A complex divide between teacher’s work, teacher knowledge and teacher education. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 803–819). London: Sage.

Tremblay, K., Lalancette, D., & Roseveare, D. (2012). Assessment of higher education learning outcomes. In Feasibility study report. Design and implementation (Vol. 1) . OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/skills-beyond-school/AHELOFSReportVolume1.pdf .

Trigg, R. (2001). Understanding social science: A philosophical introduction to the social sciences . Oxford: Blackwell publishing.

Utriainen, J., Marttunen, M., Kallio, E., & Tynjälä, P. (2016). University applicants’ critical thinking skills: The case of the Finnish educational sciences. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61, 629–649. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1173092 .

Vartiainen, H., Liljeström, A., & Enkenberg, J. (2012). Design-oriented pedagogy for technology-enhanced learning to cross over the borders between formal and informal environments. Journal of Universal Computer Science, 18 (15), 2097–2119. https://doi.org/10.3217/jucs-018-15-2097 .

Virtanen, A., & Tynjälä, P. (2018). Factors explaining the learning of generic skills: a study of university students’ experiences. Teaching in Higher Education , https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1515195 .

Zahner, D., & Ciolfi, A. (2018). International comparison of a performance-based assessment in higher education. In O. Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, M. Toepper, H. A. Pant, C. Lautenbach, & C. Kuhn (Eds.). Assessment of learning outcomes in higher education—Cross-national comparisons and perspectives (pp. 215–244). Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74338-7_11 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Heidi Hyytinen & Auli Toom

Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Richard J. Shavelson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Heidi Hyytinen .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education and Culture, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland

Mari Murtonen

Department of Higher Education, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK

Kieran Balloo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Hyytinen, H., Toom, A., Shavelson, R.J. (2019). Enhancing Scientific Thinking Through the Development of Critical Thinking in Higher Education. In: Murtonen, M., Balloo, K. (eds) Redefining Scientific Thinking for Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24215-2_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24215-2_3

Published : 22 September 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-24214-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-24215-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Schools & departments

Critical thinking

Advice and resources to help you develop your critical voice.

Developing critical thinking skills is essential to your success at University and beyond. We all need to be critical thinkers to help us navigate our way through an information-rich world.

Whatever your discipline, you will engage with a wide variety of sources of information and evidence. You will develop the skills to make judgements about this evidence to form your own views and to present your views clearly.

One of the most common types of feedback received by students is that their work is ‘too descriptive’. This usually means that they have just stated what others have said and have not reflected critically on the material. They have not evaluated the evidence and constructed an argument.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the art of making clear, reasoned judgements based on interpreting, understanding, applying and synthesising evidence gathered from observation, reading and experimentation. Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2016) Essential Study Skills: The Complete Guide to Success at University (4th ed.) London: SAGE, p94.

Being critical does not just mean finding fault. It means assessing evidence from a variety of sources and making reasoned conclusions. As a result of your analysis you may decide that a particular piece of evidence is not robust, or that you disagree with the conclusion, but you should be able to state why you have come to this view and incorporate this into a bigger picture of the literature.

Being critical goes beyond describing what you have heard in lectures or what you have read. It involves synthesising, analysing and evaluating what you have learned to develop your own argument or position.

Critical thinking is important in all subjects and disciplines – in science and engineering, as well as the arts and humanities. The types of evidence used to develop arguments may be very different but the processes and techniques are similar. Critical thinking is required for both undergraduate and postgraduate levels of study.

What, where, when, who, why, how?

Purposeful reading can help with critical thinking because it encourages you to read actively rather than passively. When you read, ask yourself questions about what you are reading and make notes to record your views. Ask questions like:

- What is the main point of this paper/ article/ paragraph/ report/ blog?

- Who wrote it?

- Why was it written?

- When was it written?

- Has the context changed since it was written?

- Is the evidence presented robust?

- How did the authors come to their conclusions?

- Do you agree with the conclusions?

- What does this add to our knowledge?

- Why is it useful?

Our web page covering Reading at university includes a handout to help you develop your own critical reading form and a suggested reading notes record sheet. These resources will help you record your thoughts after you read, which will help you to construct your argument.

Reading at university

Developing an argument

Being a university student is about learning how to think, not what to think. Critical thinking shapes your own values and attitudes through a process of deliberating, debating and persuasion. Through developing your critical thinking you can move on from simply disagreeing to constructively assessing alternatives by building on doubts.

There are several key stages involved in developing your ideas and constructing an argument. You might like to use a form to help you think about the features of critical thinking and to break down the stages of developing your argument.

Features of critical thinking (pdf)

Features of critical thinking (Word rtf)

Our webpage on Academic writing includes a useful handout ‘Building an argument as you go’.

Academic writing

You should also consider the language you will use to introduce a range of viewpoints and to evaluate the various sources of evidence. This will help your reader to follow your argument. To get you started, the University of Manchester's Academic Phrasebank has a useful section on Being Critical.

Academic Phrasebank

Developing your critical thinking

Set yourself some tasks to help develop your critical thinking skills. Discuss material presented in lectures or from resource lists with your peers. Set up a critical reading group or use an online discussion forum. Think about a point you would like to make during discussions in tutorials and be prepared to back up your argument with evidence.

For more suggestions:

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (pdf)

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (Word rtf)

Published guides

For further advice and more detailed resources please see the Critical Thinking section of our list of published Study skills guides.

Study skills guides

This article was published on 2024-02-26

- Partnerships

Critical thinking

Effective lifelong learning

Executive summary

- One of the most striking characteristics of the XX and XXI centuries is the “exponential growth” of knowledge generated in any discipline, which is available to most of the world’s citizens.

- As it is no longer possible to comprehend all the information available, in relation to disciplines or even subdisciplines, education should promote the acquisition of learning abilities related to modes of thought rather than solely the accumulation or memorization of, in many cases, information that may be only infrequently useful.

- One mode of thought, reflective thinking or critical thinking, is a metacognitive process—a set of habituated intellectual resources put purposefully into action—that enables a deeper understanding of new information. It also provides a secure foundation for more effective problem-solving, decision-making, and appropriate argumentation of ideas and opinions.

- The global output of teaching critical thinking is adding new competences to everyone’s basic capacities for greater cognitive development and freedom.

“… Nothing better for the mental development of the child and the adolescent than to teach them superior ways of learning that complement, continue, rectify and elevate the spontaneous ways. Originality is a precious heritage that the pedagogue must not only guard, but lead, in the domain of values, to its maximum expression. And with superior ways of learning, culture and originality grow in parallel. To teach superior ways of learning is to add to the native powers, new powers for greater independence of the spirit in all its manifestations. It is teaching to move only upwards…Teaching to observe well, to think well, to feel good, to express oneself well and to act well is what, in sum, every pedagogical doctrine, new or old, revolutionary or conservative, of now and forever, is materialized.” (Clemente Estable, 1947 1 ).

Introduction and historical background

The brain is the organ that allows us to think. This confronts us with a philosophical challenge that has been accompanying human civilization for more than 2,500 years: H ow can the brain help us to understand how the brain enables us to understand? 2

Ancient Greek philosophers have already questioned themselves about the source of knowledge and cognitive functions and hypothesized about the fundamental role of the brain, in opposition to the heart or even the air or fire 3-6 . The Socratic method, involving the introspective scrutiny of thought guided by questioning, paved the long-lasting way to contemporary approaches and conceptions about “good thinking,” also called “reflective thinking,” 7 and more recently, “critical thinking” 8 .

As in any area of knowledge, most of the accumulated content—which is vast and always evolving—is nowadays accessible to everyone who has access to the internet. Thus, it can be argued that educational efforts should concentrate on improving the next generation’s modes of thinking. It is desirable to promote engagement with knowledge rather than transmitting the requirement of accumulating data—usually disposable information—through mastery or memorization 9 .

Critical thinking is a fundamental pillar in every field of learning within disciplines as diverse as science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as well as the humanities including literature, history, art, and philosophy 5,9,10 .

No matter the discipline, critical thinking pursues some end or purpose, such as answering a question, deciding, solving a problem, devising a plan, or carrying out a project to face present and future challenges 11 . Hence, it is also applicable to everyday life and is desirable for a plural society with citizenship literacy and scientific competence for participation in diverse situations, including dilemmas of scientific tenor 7,12 .

In spite of the explicit valuing of critical thinking, and iterative efforts to promote its effective incorporation in the curricula at different levels of education of science, humanities, and education itself, difficulties for deeper grasping of critical thinking and challenges for its fruitful integration in educational curricula persist 13,14 . Such difficulty is in part caused by a lack of consensus regarding a definition of critical thinking.

Defining critical thinking

Critical thinking is a mental process 11 like creative thinking, intuition, and emotional reasoning, all of which are important to the psychological life of an individual 10 . It pertains to a family of forms of higher order thinking, including problem-solving, creative thinking, and decision-making 15 . However, there is not a single or direct definition of critical thinking, probably reflecting the emphasis made on different features or aspects by several authors from diverse disciplines as education, philosophy, and neurosciences 7,10,16-18 .

Some of the distinguishing features of critical thinking and critical thinkers are ( 7, 11, 12, 16, 19, 20 ; see Figure 1):

Figure 1. Diagram of the principal features of critical thinking, including some of the necessary cognitive functions and intellectual resources. The arrows indicate the main mechanisms of modulation: top-down, involving the effect of upper on lower level intellectual resources (for example, the effect of metacognition on motivation that in turn affects perception), and bottom-up (such as the influence of self-analysis and habituation on self-regulation and metacognition).

- Critical thinkers pursue some end or purpose such as answering a question, making a decision, solving a problem, devising a plan, or carrying out a project to cope with present or future challenges.

- Accordingly, critical thinking is purposively put into action and driven by .

- As a result of this top-down influence, critical thinking is an attitude which does not occur spontaneously.

- Critical thinking also involves the knowledge, acquisition, and improvement of a spectrum of intellectual resources such as: – methods of logical inquiry; – information literacy to gather significant information about the problem and the context for embracing comprehensive background knowledge; – operational knowledge of processing skills for generation of concepts and beliefs: analysis, evaluation, inference, reflective judgment.

- To accomplish these intellectual resources, critical thinkers need to put into action the most basic cognitive functions such as perception, motor coordination and action, sensory-motor coordination, language perception and production, memory, and decision-making.

- Critical thinkers apply these procedures and methods in a systematic and reasonable way.

- As a result, critical thinking is not an immediate cognitive event but a process .

- The main outcome of critical thinking is a reflective, ordered, causal flow of ideas .

- Critical thinkers self-analyze and self-assess the mode of thinking.

- Consequently, critical thinking is a metacognitive process .

- Self-evaluation launches a bottom-up process for modulation and improvement of critical thinking, enabling greater adaptability to different situations.

- Thus, critical thinking also requires training and habituation .

- As a global outcome, critical thinking, as a metacognitive process, also refines self-regulation (i.e., the ability to understand and control our learning environments) 20 .

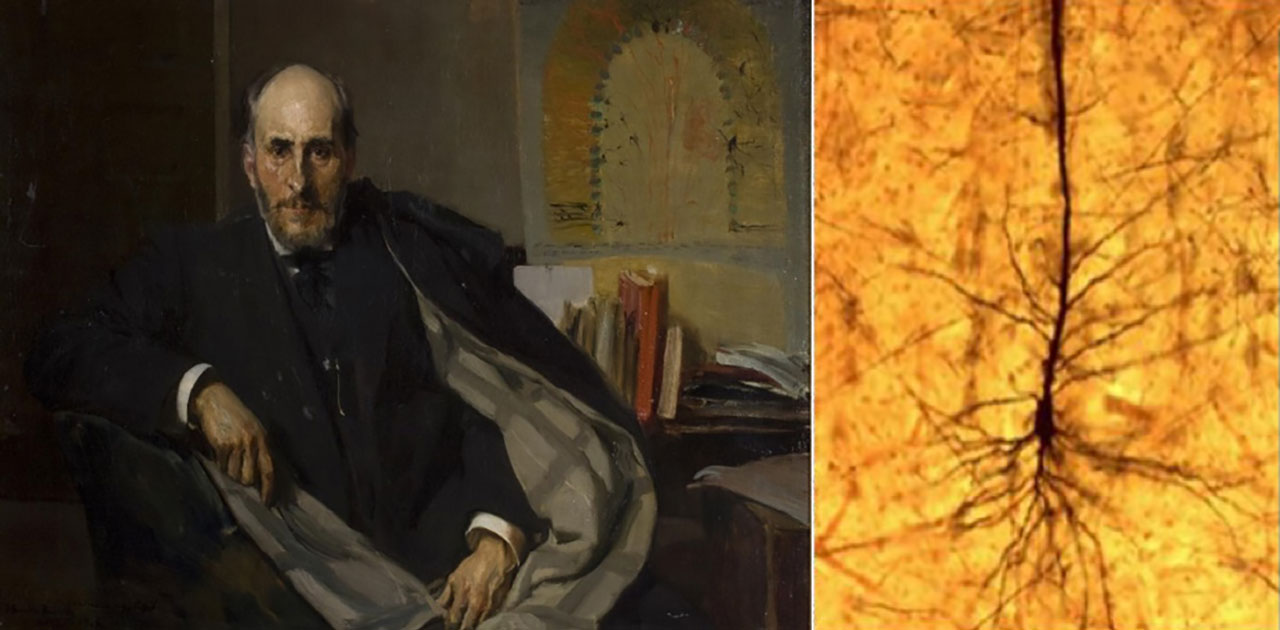

In sum, critical thinking is a purposeful, intellectually demanding, disciplined, plastic, and trainable mode of thinking in which motivation, self-analysis, and self-regulation play key roles. Several of these aspects were stressed by Santiago Ramón y Cajal (see Figure 2A). Cajal—founder of modern neuroscience and Nobel Prize of Medicine in 1906—hypothesized about the role of brain plasticity, metanalysis habituation, and self-regulation for the acquisition of knowledge about objects or problems: “When one thinks about the curious property that man possesses of changing and refining his mental activity in relation to a profoundly meditated object or problem, one cannot but suspect that the brain, thanks to its plasticity, evolves anatomically and dynamically, adapting progressively to the subject. This adequate and specific organization acquired by the nerve cells eventually produces what I would call professional talent or adaptation, and has its own will, that is, the energetic resolution to adapt our understanding to the nature of the matter.” 20

Figure 2. Left: Portrait of Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Oil painted by the Spanish Postimpressionist painter Joaquín Sorolla in 1906, the year Cajal received the Nobel Prize in Medicine 21 . Right: Microphotography of an original preparation of Cajal showing a pyramidal neuron of the human brain cortex. Staining: Golgi staining. Original handwritten label: Pyramid. Boy 22 .

Neural basis of critical thinking

Figure 3. Mapping of cognitive functions. The diagram superposed on the lateral view of the human brain indicates the location of distributed neural assemblies activated in relation to cognitive functions. Note that the indicated cognitive functions are involved in the same or successive phases of critical thinking. (Modified from ref. 26 ).

The cognitive functions and intellectual resources involved in critical thinking are emergent properties of the human brain’s structure and function which depend on the activity of its building blocks, the neurons (see Figure 2B). Neurons are specialized cells which are almost equal in number to nonneuronal cells in human brains. Of the total amount of 86 billon neurons, 19% form the cerebral cortex and 78% the cerebellum 23 . Neurons are interconnected and intercommunicate through specialized junctions called synapses, of which there are about 0,15 quadrillion in the cerebral cortex 24 and more than 3 trillion in the cerebellar cortex (considering the total number of Purkinje cells and the total amount of synapses/Purkinje cell 25 ). These stellar numbers help us imagine the density of the entangled brain web. This web is not fully active at any time. Instead, distributed groups of neurons or “distributed neural assemblies” are more active at certain topographies when particular cognitive functions are taking place 26 . Considering the spectrum of cognitive functions involved in the process of critical thinking, it will increase activation in much of the brain cortex (see Figure 3).

Teaching critical thinking

“It is not enough to know how we learn, we must know how to teach.” (Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, 2010 27 ).

Teachers have the invaluable potential power of fostering knowledge in the next generations of students and citizens. However, this power is expressed when teachers, instead of teaching what they know—and hence limiting students’ knowledge to their own—teach students to think critically and so open up the possibility that students’ knowledge will expand beyond the borders of the teachers’ own knowledge 28 . Thus, it is important to be aware that—similar to electrical circuits and Ohm’s law—the wealth and depth of students’ knowledge that is achieved or expressed depends not only on the energy or effort that students put in the task but also their own (internal) resistance as well as teachers’ (external) resistance. This metaphor exemplifies that the expected outcomes of education may be better achieved if teachers are familiar with the foundations of critical thinking, better appreciate its worth, and themselves become proficient at thinking critically, particularly in relation to their professional activity.

Now more than ever it is possible for teachers to build a framework to improve the teaching and learning of critical thinking in the classroom 29 thanks to a wealth of information and guidelines resulting from contributions of diverse disciplines since the renewed interest in critical thinking and its promotion in education pioneered by Dewey 7 at the dawn of the 20th century. According to Boisvert (1999 28 ), up to the 1980s, education focused on the abilities of critical thinking as goals to achieve.

Since then, a growing movement of critical thinking has been characterized by iterative attempts to define critical thinking, as well as by instructing teachers about this process and how to teach it. In parallel, several tools for assessment have been created 11, 30, 31, 32, 33 .

Nevertheless, the long-lasting aim has not been achieved. In trying to envisage more fruitful strategies, it is worth noting the difficulty of transmitting critical thinking as just a skill that can be trained without considering the context. On the contrary, the domain of knowledge and the development of critical thinking should be considered in parallel as related intellectual resources—as pointed out by Willimham 33 . It is worth pointing out that, parallel to the critical thinking movement, there has been an increasing simultaneous interest in the neural bases of critical thinking, leading to the emergence 5,34 of “educational neuroscience” 35 and “brain, mind and education” 36 . These interdisciplinary fields have been elucidating the fundamental mechanisms involved in critical thinking as well as the role of factors that impact on this ability. This, along with the tight collaboration between scientists and teachers, is forging a new (Machado) path or bridge over the “gulf” between these fields 35 .

References/Suggested Readings & Notes

- Estable, C. 1947. Pedagogía de presión normativa y pedagogía de la personalidad y de la vocación. An. Ateneo Urug., 2ª ed., 1, 155-156. http://www.periodicas.edu.uy/Anales_Ateneo_Uruguay/pdfs/Anales_Ateneo_Uruguay_2a_epoca_n2.pdf

- Shepherd, G, M. 1994. Neurobiology, 3rd edn , Oxford University Press.

- Cope, E. M. 1875. Plato’s Phaedo, Literally translated , Cambridge University Press.

- Adams, L. L. D. 1849. Hippocrates Translated from the Greek with a preliminary discourse and annotations. The Sydenham Society.

- Vieira, R. M., Tenreiro-Vieira, C. & Martins, I. P. Critical thinking: conceptual clarification and its importance in science education. Science Education International 22,43–54 (2011).

- Panegyres, K. P. & Panegyres, P. K. The ancient Greek discovery of the nervous system: Alcmaeon, Praxagoras and Herophilus. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 29, 21–24 (2016).

- Dewey, J. How we think. The Problem of Training Thought 14 (1910). doi:10.1037/10903-000

- Glaser, E. M. (1941). An experiment in the development of critical thinking . New York: Columbia University Teachers College.

- Edmonds, Michael, et al. History & Critical Thinking: A Handbook for Using Historical Documents to Improve Students’ Thinking Skills in the Secondary Grades. Wisconsin Historical Society, 2005. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/pdfs/lessons/EDU-History-and-Critical-Thinking-Handbook.pdf

- Mulnix, J. W. Thinking critically about critical thinking. Educational Philosophy and Theory 44, 464–479 (2012).

- Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R. & Daniels, L. B. Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies 31, 285–302 (1999).

- Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J. & Stewart, I. An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills and Creativity 12, 43–52 (2014).

- Paul, R. The state of critical thinking today. New Directions for Community Colleges 130, 27–39 (2005).

- Lloyd, M. & Bahr, N. Thinking critically about critical thinking in higher education. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning 4, 1–16 (2010).

- Rudd, R. D. Defining critical thinking. Techniques. 46 (2007).

- Siegel, H. (1988) . Educating reason: Rationality, critical thinking, and education . Philosophy of education research library. Routledge Inc.

- Siegel, H. in International Encyclopedia of Education 141–145 (Elsevier Ltd, 2010). doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00582-0

- Bailin, S. Critical thinking and science education. Science & Education (2002) 11: 361. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016042608621

- Facione, P. A. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. California Academic Press 1–19 (1990). doi:10.1080/00324728.2012.723893

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education 36(1–2), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-3917-8

- Ramon y Cajal, S. Recuerdos de mi vida . Juan Fernández Santarén, Barcelona. Editorial Crítica ( 1899); Of Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32562506).

- From: http://www.montelouro.es/Cajal.html.

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The human brain in numbers: a linearly scaled-up primate brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 3, (2009).

- Pakkenberg, B. et al. Aging and the human neocortex. Experimental Gerontology 38, 95–99 (2003).

- Nairn JG, Bedi KS, Mayhew TM, Campbell LF. On the number of Purkinje cells in the human cerebellum: unbiased estimates obtained by using the “fractionator”. J Comp Neurol. 290(4), 527-32 (1989).

- Pulvermüller, F., Garagnani, M. & Wennekers, T. Thinking in circuits: toward neurobiological explanation in cognitive neuroscience. Biological Cybernetics 108, 573–593 (2014).

- Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. The New Science of Teaching and Learning: Using the Best of Mind, Brain, and Education Science in the Classroom. Teachers College Press (2010).

- Chavan, A. A. & Khandagale V. S. Development of critical thinking skill programme for the student teachers of diploma in teacher education colleges. Issues Ideas Educ. http://dspace.chitkara.edu.in/xmlui/handle/1/159.

- Paul, R. & Elder, L. Guide for educators to critical thinking competency standards: standards, principles, performance indicators, and outcomes with a critical thinking master rubric. Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2007).

- Paul, R. W. Critical Thinking: What Every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World. Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2000). Retrieved from http://assets00.grou.ps/0F2E3C/wysiwyg_files/FilesModule/criticalthinkingandwriting/20090921185639-uxlhmlnvedpammxrz/CritThink1.pdf

- Paul, R. W., Elder, L. & Bartell, T. California Teacher Preparation for Instruction in Critical Thinking: Research Findings and Policy Recommendations. (1997). Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1001.1087&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Vieira, R. M. Formação continuada de professores do 1.º e 2.º ciclos do Ensino Básico para uma educação em Ciências com orientação CTS/PC. Tese de doutoramento (não publicada), Universidade de Aveiro. (2003). Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/374/37419205.pdf

- Willingham, D. T. Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach? American Educator 31, 8-19. (2007). Retrieved from http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Crit_Thinking.pdf

- Zadina, J. N. The emerging role of educational neuroscience in education reform. Psicología Educativa 21,71–77 (2015).

- Goswami, U. Neurociencia y Educación: ¿podemos ir de la investigación básica a su aplicación? Un posible marco de referencia desde la investigación en dislexia. Psicologia Educativa 21, 97–105 (2015).

- Schwartz, M. Mind, brain and education: a decade of evolution. Mind, Brain, and Education 9, 64–71 (2015).

- Cognitive Science

DEVELOPMENT OF CRITICAL THINKING AS THE PRIMARY GOAL OF EDUCATIONAL PROCESS

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Wirawan Sumbodo

- Sudiyono Sudiyono

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- News & Events

- Quick Links

- Majors & Programs

- People Finder

- home site index contact us

ScholarWorks@GVSU

- < Previous

Home > Graduate Research and Creative Practice > Culminating Experience Projects > 456

Culminating Experience Projects

The importance of critical thinking skills in secondary classrooms.

Clinton T. Sterkenburg , Grand Valley State University Follow

Date Approved

Graduate degree type, degree name.

Education-Instruction and Curriculum: Secondary Education (M.Ed.)

Degree Program

College of Education

First Advisor

Sherie Klee

Academic Year

According to research, many students lack effective critical thinking skills. The ability to think critically is crucial for individuals to be successful and responsible. Many students have difficulties understanding this important skill and especially lack the ability to initiate and apply the process. Although a difficult task, educators have the responsibility to teach critical skills to students and to discern when certain instructional methods or activities are not helping students. Each student is different, and their needs must be considered, this correlates with how they learn and process information. Research has shown that traditional teaching methods that require students to regurgitate information do not prove helpful in teaching students to apply and understand the critical thinking process. Therefore, effective teachers expand upon traditional teaching methods and differentiate instructional and activity design for imparting critical thinking skills to students. This project presents some of the possible reasons students have difficulties thinking critically and provides examples of instructional and lesson design methods that are proven to help students understand critical thinking. The goal of this project is to provide a guide for secondary teachers to address the lack of critical thinking skills in many students. The ability to think critically will greatly benefit students and help them become productive members of society.

ScholarWorks Citation

Sterkenburg, Clinton T., "The Importance of Critical Thinking Skills in Secondary Classrooms" (2024). Culminating Experience Projects . 456. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gradprojects/456

Since August 05, 2024

Included in

Curriculum and Instruction Commons , Secondary Education Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- University Archives

- Open Textbooks

- Open Educational Resources

- Graduate Research and Creative Practice

- Selected Works Galleries

Author Information

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit Research

- Graduate Student Resources

Home | About | FAQ | Contact | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Help Your Child Develop Critical Thinking Skills

Children today need to learn how to think critically more than ever because it's a skill that will be increasingly valuable to them in the future. Children must be able to do more than just learn facts in our ever-changing world. They must be able to comprehend the material, assess it, analyze it, compare it to the knowledge they have already acquired, and come to a logical conclusion to solve the current problem. Therefore, it's crucial to introduce children to various forms of critical thinking so they can become more adept at problem-solving in the future.

Critical thinking: What Is It? The capacity to derive new conclusions from preexisting knowledge and problem-solving techniques is known as critical thinking. It is a crucial ability for children to acquire since it enables them to investigate their surroundings and uncover new information. These abilities help young people realize the consequences of their own actions and assist them in making sensible decisions.

Ways to Develop Critical Thinking Skills:

Encourage Curiosity - Youngsters with inquisitive minds constantly seek to learn more about their surroundings. They seek to acquire updated knowledge regarding the same object or entirely different objects. Children frequently ask their elders "why" questions to quench their curiosity. To find the answers to the "why" questions, they must pique their curiosity and teach them a variety of new things.

Encourage the Interests of Children - Children can become quite engrossed in things that pique their interest for extended periods. They are more likely to be interested in learning and open to trying new things when they are enthusiastic about a subject or activity. Fostering new interests in children can help them learn more and provide opportunities for critical thinking.

Encourage Independent Thinking - Every day, children pick up a lot of knowledge, but it's crucial to assess whether it's true, pertinent, and useful. Encourage kids to share their thoughts on what they've learned so they can evaluate it and determine whether to apply it. This will help them develop these abilities. They will be more capable of making decisions as a result.

Give Them the Freedom to Learn - Children pick up skills on their own, especially in difficult situations. As parents, we may feel compelled to solve our children's problems for them, but it's usually best to wait and observe how the child approaches the issue and comes up with a solution on their own. Occasionally, a parent might have to step in and help. In these situations, parents can explain their own ideas and behaviours to their children and serve as an example of critical thinking.

Here are some specific activities that can help develop critical thinking skills in children:

- Puzzle Solving: Provide puzzles and brainteasers that challenge children to use logic and reasoning.

- Science Experiments: Conduct simple science experiments where children can hypothesize, test, and draw conclusions.

- Storytelling: Encourage children to create their own stories or build on existing ones, promoting creativity and logical sequencing.

- Debates: Organize friendly debates on age-appropriate topics to help children learn to form and defend their opinions.

- Role-Playing: Engage in role-playing games where children must make decisions based on different scenarios.

- Building Projects: Use building blocks or craft materials to construct projects that require planning and problem-solving.

Fostering critical thinking skills in children is an essential part of their development. By incorporating activities that encourage questioning, problem-solving, reflection, and creative thinking, children can build a strong foundation for future learning and decision-making. These skills not only enhance academic performance but also prepare children to navigate complex situations in everyday life. Through continuous practice and supportive guidance, children can become confident, independent thinkers.

- Entertainment

- Life & Style

To enjoy additional benefits

CONNECT WITH US

Benefits of speaking clubs in higher education institutions

Active participation can help students build confidence and hone their communication, analytical and critical thinking skills.

Updated - August 12, 2024 11:03 am IST

Published - August 10, 2024 11:33 am IST

In this ever-changing world, effective communication is crucial for success, and participating in speaking clubs is a way of developing this skill. | Photo Credit: Freepik

I t is true that in today’s world, acquiring knowledge is pivotal, but being able to effectively communicate ideas is equally crucial. According to research by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), employers highly value communication skills. This is where speaking clubs come into play, offering students a valuable chance to enhance their communication abilities and providing various benefits that set them apart in their academic and professional pursuits.

Confidence building and public speaking skills are the major benefits derived from participation in speaking clubs. Research from UCLA shows that 74% of students experience communication apprehension. Speaking clubs create a friendly environment for practising expression, thus allowing learners to overcome stage fright. Consistent involvement helps students become calm as they learn how to speak articulately and confidently. This newly found assertiveness also extends into other areas like participating in class discussions, and giving presentations and during interviews.

Multiple benefits

A successful speech requires research and persuasively organising ideas, and all this necessitates extensive learning. Also, students are taught to develop solid arguments with evidence. Thus an involvement with speaking clubs also leads to the development of analytical and critical thinking skills. Additionally, speaking clubs nurture active listening abilities, as members not only to present their speeches but also engage in the activities of their peers. This implies listening attentively, spotting strengths and weaknesses in arguments, and providing suggestions that help fellow speakers improve. These highly developed listening skills are valuable when working collaboratively on projects, operating in teams or any other context where effective communication matters.

Speaking clubs also offer a platform to explore diverse perspectives and cultures. Topics chosen for speeches can range from current events and social issues to personal experiences and cultural narratives. This fosters an environment of open exchange and debate, allowing students to learn from and appreciate the richness of a multicultural society. This broadened perspective equips students to become more well-rounded individuals and global citizens, better prepared to navigate an interconnected world.

Beyond the immediate benefits, speaking clubs can unveil a world of leadership opportunities. Active members often find themselves taking on leadership roles within the club, organising events, planning workshops, and mentoring new members. These experiences help develop skills such as leadership, delegation, and team management. Such experiences not only enhance resumes but also instill the confidence and ability to lead effectively in future endeavours.

The benefits of speaking clubs extend beyond the individual student. These organisations can nurture a more vibrant and engaged campus community. Through events, workshops, and inter-club competitions, they create opportunities for interaction and collaboration between students from different departments and backgrounds. This promotes a sense of fellowship and belonging, enriching the overall student experience.

Of course, to maximise the transformative power of speaking clubs, it’s crucial to cultivate a supportive and inclusive environment. Creating a space where constructive criticism is encouraged while negativity is discouraged is key. Additionally, offering workshops on topics like body language, vocal techniques, and crafting engaging presentations can greatly enhance the learning experience.

In this ever-changing world, effective communication is crucial for success, and participating in speaking clubs is a way of developing this skill. Promotion of speaking clubs should be top among the priorities of institutions to empower their students.

For those who cannot attend clubs because of different reasons, online clubs provide a supportive setting where one can perfect the art of public speaking while interacting with other learners from all over the globe.

The writer is Founder, Educate Online.

Related Topics

education / The Hindu Education Plus / careers / higher education / students / university / universities and colleges

Top News Today