Lessons From the Most Corrupt Judge in U.S. History

W e tend to think of our judges as black-robed monastics cloistered in their temples of justice, hermetically sealed off from worldly temptations. History teaches us this is not always so. Long before recent news reports about current U.S. Supreme Court Justices accepting gifts from private parties, a sordid and shocking case of judicial corruption–the worst in our nation’s history–unspooled in a downtown courtroom in Depression-era Manhattan. Though largely forgotten today, it serves as an enduring reminder that judges, too, are human.

Martin T. Manton was not just any judge. From 1918 to 1939, Manton served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, based in New York City. Even more so than today, New York then was the beating heart of the country’s commercial, financial, cultural, religious, and political life. This meant that the Second Circuit decided a disproportionate share of the country’s most consequential lawsuits. And it earned Manton, the court’s senior judge beginning in 1927, the informal title of “the tenth-ranking judge in the United States,” below only the nine Justices of the Supreme Court. A Columbia law graduate and the recipient of honorary degrees from five other universities, Manton came within a whisker of being appointed to the Supreme Court himself.

As if his day job weren’t enough, the prodigiously energetic jurist engaged in an impressive array of extrajudicial activities. Knighted by the Pope in 1924, he ranked as one of the top Catholic laymen in the United States. He was a leading proponent of international peace organizations such as the World Court. Unusually active for a judge in partisan politics, he is said to have played a key role in the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that led to Franklin Roosevelt’s first presidential nomination at the 1932 Democratic convention. On top of all this, he managed a small business empire out of his chambers, with extensive real estate holdings and interests in a variety of operating companies.

Less visibly, Manton operated a side business with a more unwholesome objective: cashing in on his status and power as a judge.

In literally dozens of cases, Manton solicited payments and “loans” (many never repaid) from litigants, or the lawyers representing them, in cases in the Second Circuit. Invariably, he would then write the decision for the court finding in favor of the party that fattened his bank account. In all, Manton raked in some $17 million (in today’s dollars) from his schemes. His prosecutor fittingly dubbed him a “merchant of justice,” who systematically abused his judicial office for private gain on a scale unmatched by any federal judge before or since.

All sorts of legal controversies proved grist for Manton’s corruption mill: high-stakes patent infringement battles between business rivals, internecine corporate disputes between stockholders and corporate officers, a constitutional challenge mounted by railroad interests to New York’s longstanding nickel subway fare, federal criminal prosecutions. Manton deployed a network of fixers, bagmen, and front men who helped to identify sources of bribes, negotiate the terms, and conceal the proceeds inside a maze of opaque financial arrangements. He even enlisted the help of another federal judge to deliver promised judicial benefits in some cases.

Sometimes the bribe money was paid in cash, which Manton stuck in a safe he kept in his chambers in the federal courthouse. Sometimes the benefits flowed to Manton’s family members, as when an insurance broker hired by receivers appointed by Manton agreed to funnel kickbacks to the judge’s sister and niece. On one occasion a litigant financed the cost of a transatlantic voyage for Manton’s summer vacation.

Manton’s machinations in some ways merely reflected the Tammany Hall credo of “honest graft,” in George Washington Plunkitt’s famous phrase: the idea that public servants were expected and entitled to profit off their positions. In such a culture, there was no shortage of private actors willing to feed the judge’s greed, even at the highest echelons of the business and legal elite. Among the many litigants who stuffed Manton’s pockets were the nation’s largest cigarette manufacturer, its second largest maker of electric razors, the head of the Warner Brothers movie studio, and the biggest baby chick hatchery on the East Coast. Prominent Wall Street lawyers orchestrated, facilitated, or closed their eyes to these illicit payments, including a Columbia law school classmate of Manton who was disbarred for his actions, and Thomas Chadbourne, founder of the venerable Chadbourne Parke law firm and one of the most influential lawyers of the era.

Read More: Sachems And Sinners, An Informal History of Tammany Hall

Even more disturbingly, Manton’s confederates included the underworld forces who, in tandem with the Tammany Hall political machine, ruled much of New York in the 1930s. As revealed in previously undisclosed FBI files, Manton fraternized with racketeers and accepted large loans and gifts from such unsavory sources. Compelling evidence shows that the two most notorious gangsters of the era, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro, arranged a payoff to Manton to secure their release on bail – whereupon they promptly began assassinating the witnesses against them. “He’s the only federal judge left in New York we can use to get people out of jail,” Tammany Hall boss and underworld ally Jimmy Hines reportedly said of Manton.

Today the risk of “another Manton” has been lessened by stringent financial disclosure requirements and ethical standards governing federal judges (though those standards are not binding on Supreme Court Justices). But criminal laws and canons of judicial ethics existed in Manton’s day too, and he nearly escaped accountability. Reports of his corruptibility had made their way to the FBI years earlier and were dutifully passed on by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to senior officials in FDR’s Justice Department, where they inexplicably languished. It took an enterprising reporter for the anti-Tammany New York World-Telegram to bring Manton’s misdeeds to light, aided by Manhattan District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey, who publicly released the findings of a probe by his office into Manton’s activities. At that point the Justice Department had no choice but to open its own investigation. In June 1939, after a trial in the very federal courthouse where he had once reigned supreme, a jury found Manton guilty. He was sentenced to two years in prison.

To the end, Manton insisted he’d done nothing wrong, because he would have ruled the same way regardless of the lucre bestowed by litigants. The appeals court that upheld his conviction emphatically disagreed, declaring that “judicial action, whether just or unjust, is not for sale” and warning that if Manton’s argument were sustained, “the event will mark the first step toward the abandonment of that imperative requisite of even-handed justice”: that “the judge must be perfectly and completely independent.” Words worth heeding in any era.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Peter Berkowitz

- Ross Levine

- Michael McFaul

- Timothy Garton Ash

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press, judicial corruption in developing countries: its causes and economic consequences.

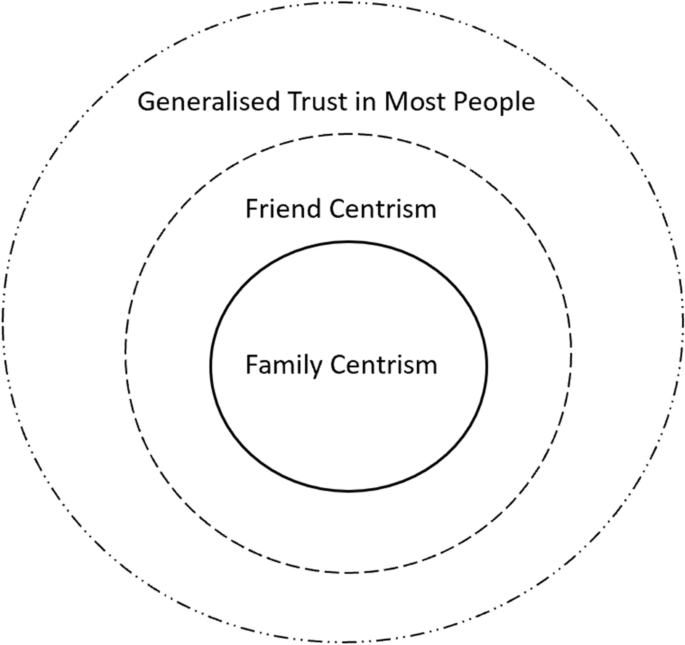

Many scholars have provided path-breaking contributions to the institutional analysis of systemic and systematic corruption. Descriptive studies focusing on corrupt practices and on the impact of corruption on economic development are abundant. Yet the literature has not yet isolated the main legal, organizational, and market-related causes of systemic corruption within the public sector in general and within the judiciary in particular.

This essay proposes a framework within which the institutional analysis of corrupt activities within the judiciary can be further understood in developing countries. First, an approach to the study of public sector corruption based on science, not on guesswork or intuition, must be verifiable if we are to develop reliable anticorruption policy prescriptions. Therefore, legal, economic, and organizational factors are proposed here to explain corruption within the judicial sectors of developing countries. Second, the economic theory of corruption should recognize that official corruption is a significant source of institutional inertia in public sector reforms. An account of the private costs and benefits of judicial reforms as perceived by public officials is also considered in this study.

The law and economics of development focuses its attention on the effects that well-functioning legal and judicial systems have on economic efficiency and development. Adam Smith states in his Lectures on Jurisprudence that a factor that "greatly retarded commerce was the imperfection of the law and the uncertainty in its application" (Smith, 528). Entrenched corrupt practices within the public sector (i.e., official systemic corruption) hamper the clear definition and enforcement of laws, and therefore, as Smith (1978) stated, commerce is impeded.

Systemic corruption within the public sector can be defined as the systematic use of public office for private benefit that results in a reduction in the quality or availability of public goods and services (Buscaglia 1997a). In these cases, corruption is systemic when a government agency only supplies a public good or service if an otherwise unwilling transfer of wealth takes place from an individual or firm to the public sector through bribery, extortion, fraud, or embezzlement.

Rose-Ackerman (1997, 5) states that "widespread corruption is a symptom that the state is functioning poorly." In fact, the entrenched characteristic of official corrupt practices is rooted in the abuse of market or organizational power by public sector officials (Buscaglia 1997a, 277). Many studies have already shown that the presence of perceived corruption retards economic growth, lowers investment, decreases private savings, and hampers political stability (Maoro 1995; Schleifer and Vishny 1993). Moreover, foreign direct investment has demonstrated a special negative reaction to the presence of corruption within the public sectors in developing countries (Leiken 1996); Lambsdorff (1998) shows that the degree of corruption in importing developing countries also affects the trade structure of exporting countries.

Many scholars have provided path-breaking contributions to the economic analysis of corruption. Studies focusing on describing corrupt practices and on analyzing the impact of corruption on economic development are abundant. Low compensation and weak monitoring systems are traditionally considered to be the main causes of corruption. In Becker-Stigler (1974) and Klitgaard (1991), official corruption through bribery of public officials reduces the expected punishment faced by potential criminals and thus hampers deterrence. In this context, increasing the salaries of public enforcers or paying private enforcement agencies for performance or both would tend to improve the quality of enforcement.

Rose-Ackerman (1978), Macrae (1982), Shleifer and Vishny (1993), and Maoro (1995) provide alternative approaches to the economic analysis of corruption. In those studies, corruption is considered to be a behavioral phenomena occurring between the state and the market domains. In all cases, they assume that people and firms respond to incentives by taking into account the probability of apprehension and conviction and the severity of punishment (Becker 1993). Of course, in all those studies, ethical attitudes matter. The economic analysis of corruption stresses, however, that, to a lesser or greater degree, people respond to incentives.

The existence of official corruption distorts market systems by introducing uncertainty in social and economic interactions (Andvig 1991). Moreover, official corruption is an essential input for the growth of organized criminal groups with the capacity to pose a significant international security threat through the illicit traffic of, among other things, narcotics, nuclear, chemical, and biological materials, alien smuggling, and international money-laundering operations (Leiken 1996).

The literature mentioned above provides an outstanding overview of the social situations associated with entrenched corruption within the public sectors. But an economic theory of corruption must contain more than just an account of the general situations enhancing corrupt practices. Therefore, in order to develop reliable anticorruption policies, it is necessary to go beyond the simply descriptive and symptomatic studies of official corruption by focusing on the search for scientifically tested causes of corrupt practices in specific institutions within the public sector. Although all the above studies have made path-breaking contributions to the economic analysis of corruption, the literature has not yet isolated or empirically tested the main legal, organizational, and economic causes of corruption within specific public sector institutions.

This essay advances a review of the causes of corruption within the judiciary in developing countries. First, corruption within the judiciary (e.g., paying a bribe to win a case) has a profound impact on the average citizen's perception of social equity and on economic efficiency (Buscaglia 1997b). The individual's judgment of how equitable the social environment is must be incorporated into the long-term impact of corruption on efficiency. Second, a scientific approach to the study of corruption must be empirically verifiable if we are to develop reliable public policy prescriptions in the fight against official corruption (a review of the latest findings in this area follows). Third, the economic theory of corruption should recognize that official corruption is a significant source of foot-dragging or institutional inertia in public sector and market reforms in developing countries. An account of the private costs and benefits of state reforms as perceived by public officials must also be considered in those cases.

T HE M AIN C AUSES OF C ORRUPTION WITHIN THE J UDICIARIES IN D EVELOPING C OUNTRIES

A scientific approach to the analysis of corruption is a necessary requirement in the fight against any social ill. Corruption is no exception. Systemic corruption deals with the use of public office for private benefit that is entrenched in such a way that, without it, an organization or institution cannot function as a supplier of a good or service. The probability of detecting corruption decreases as corruption becomes more systemic. Therefore, as corruption becomes more systemic, enforcement measures of the traditional kind affecting the expected punishment of committing illicit acts become less effective and other preventive measures, such as organizational changes (e.g., reducing procedural complexities in the provision of public services), salary increases, and other measures, become much more effective. The growth and decline of systemic corruption is also subject to laws of human behavior. We must better define those laws before implementing public policy. For this purpose we must

- Formulate a policy claim (e.g., administrations with high concentrations of organizational power in the hands of few public officials with no external auditing systems are prone to corrupt behavior)

- Formulate a logical explanation of a policy claim (e.g., why higher concentrations of organizational power and corrupt behavior go hand in hand)

- Gather information to support or disprove the claim

- Design public policies based on the findings

In this context, in order to design public policies in the fight against corruption, it is necessary to build a data base with quantitative and qualitative information related to all the factors thought to be related to certain types of systemic corrupt behavior (embezzlement, bribery, extortion, fraud, etc.). For example, the World Bank is currently assembling a data base of judicial systems worldwide (Buscaglia and Dakolias 1999) that covers those factors associated to relative successes in the fight for an efficient judiciary.

International experience shows that specific macropolicy actions are associated with the reduction in the perceived corruption in countries ranging from Uganda to Singapore, from Hong Kong to Chile (Kaufmann 1994). These actions include lowering tariffs and other trade barriers; unifying market exchange and interest rates; eliminating enterprise subsidies; minimizing enterprise regulation, licensing requirements, and other barriers to market entry; privatizing while demonopolizing government assets; enhancing transparency in the enforcement of banking, auditing, and accounting standards; and improving tax and budget administration. Other institutional reforms that hamper corrupt practices include civil service reform, legal and judicial reforms, and the strengthening and expansion of civil and political liberties. Finally, there are the microorganizational reforms, such as improving administrative procedures to avoid discretionary decision making and the duplication of functions, while introducing performance standards for all employees (related to time and production); determining salaries on the basis of performance standards; reducing the degree of organizational power of each individual in an organization; reducing procedural complexity; and making norms, internal rules, and laws well known among officials and users (Buscaglia and Gonzalez Asis 1999).

Sequencing the Design of Anticorruption Policies

The following steps are recommended in the design of anticorruption policies:

- Perform a diagnostic analysis within a country identifying, within a priority list, the main institutional areas where sys[chtemic corruption arises. This identification must be conducted through surveys of users of government services, businesses, or taxpayers. The survey should be applied to each government institution (e.g., customs, judiciary, tax agencies, and others).

- Once a priority list of areas subject to systemic corruption is derived, develop a data base for each of these institutions containing objective and subjective measures of corruption (e.g., reports of corruption, indictments related to fraud, embezzlement, extortion, or bribery in that agency, prices charged by the agency) and other variables that are thought to explain corruption. Gather information on procedural times in the provision of government services; users' perceptions of efficiency, effectiveness, corruption, and access related to that agency; procedural complexity in the provision of services; and so on.

- Conduct a statistical analysis clearly identifying the factors causing corruption in a specific government agency. Identify whether any of the economic, institutional, and organizational factors mentioned above are related to corruption.

- Once the diagnostic and identification stages are complete, civil society should become involved in implementating and monitoring the anticorruption policies. The action plan should be developed through consensus between civil society and government and contain problems, solutions, deadlines for implementation of solutions, and expected results.

This approach has been applied at the judicial and municipal levels in many countries with significant results (Buscaglia and Dakolias 1999). Those cases used the following steps: First, a survey was conducted of those users applying for specific permits from their local government (county office, in Venezuela). Those users were interviewed just after finishing the application procedure and were asked to rank the efficiency, effectiveness, level of access, quality of information received, and corruption in the administrative procedure used to obtain construction and industrial license permits. Next, numerical and qualitative data were gathered to identify those variables affecting the public's responses to the survey by applying statistical analyses. The results of this diagnostic study were then shared with representatives of civil society and local government at a workshop. In this workshop, representatives of civil society and local government could agree or disagree with the results.

Once the civil society and the government agreed on the nature of the problems, a technical empirical study conducted by the interdisciplinary team focused on how to reduce corruption and increase efficiency in those areas (e.g., issue of permits) covered by the diagnostic study. This technical study, which identified the mechanisms to reduce corruption and increase efficiency/effectiveness, was later discussed, understood, and accepted by members of the civil society and local government. Civil society was able to devise mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of reforms with deadlines included. The results of implementing these reforms must be measured months after the implementation stage has been completed through another survey of users applying for those same type of permits. The actual results were then compared with the expected results, previously defined as goals by civil society groups. Those experiences show that the implementation of any anticorruption campaign must be based on sound multidisciplinary scientific principles applied by researchers, practitioners, and civil society. Only a multidisciplinary approach specifying methodology, data, a scientific analysis of what works and what does not work, and, finally, a well-specified sequencing of policy steps as mentioned above can establish a solid policy consensus in the fight against systemic corruption.

Scholars have already recognized the advantages of going beyond the analysis of the impacts of corruption on economic growth and investment, and some have stated the urgent need to isolate the structural features that create corrupt incentives (Rose-Ackerman 1997). But only general situations within which corruption may arise have been identified in the literature. These situations are neither overlapping nor exhaustive. A rigorous analysis, however, of the corruption-enhancing factors within the courts has been unexplored in the literature. The need to develop an empirically testable anticorruption policy in the courts is necessary to incorporate the study of corruption into the mainstream of social science.

The empirical frameworks first introduced by Buscaglia (1997a) to Ecuador and Venezuela and by Buscaglia and Dakolias (1999) to Ecuador and Chile explain the yearly changes in the reports of corruption within first-instance courts dealing with commercial cases. That work shows that specific organizational structures and behavioral patterns within the courts in developing countries make them prone to the uncontrollable spread of systemic corrupt practices. For example, their work finds that the typical Latin American court provides internal organizational incentives toward corruption. A legal and economic analysis of corruption should be able to detect why the use of public office for private benefit becomes the norm. In theory, most developing countries possess a criminal code punishing corrupt practices and external auditing systems within the courts for monitoring case and cash flows. Even if they function properly, however, those two mechanisms would not be enough to counter the presence of systemic corruption in the application of the law. Other dimensions need to be addressed.

Specific and identifiable patterns in the administrative organization of the courts, coupled with a tremendous degree of legal discretion and procedural complexities, allow judges and court personnel to extract additional illicit fees for services rendered. Buscaglia (1997a) also finds that those characteristics fostering corrupt practices are compounded by the lack of alternative mechanisms to resolve disputes, thus giving the official court system a virtual monopoly. More specifically, according to Buscaglia (1998) and Buscaglia and Dakolias (1999), corrupt practices are enhanced by (1) internal organizational roles concentrated in the hands of a few decision makers within the court (e.g., judges concentrating a larger number of administrative and jurisdictional roles within their domain); (2) the number and complexity of the procedural steps coupled with a lack of procedural transparency followed within the courts; (3) great uncertainty related to the prevailing doctrines, laws, and regulations (e.g., increasing inconsistencies in the application of jurisprudence by the courts due to, among other factors, the lack of a legal data base and defective information systems within the courts); (4) few alternative sources of dispute resolution; and, finally, (5) the presence of organized crime groups (e.g., drug cartels), that, according to Gambetta (1993), demand corrupt practices from government officials.

These five factors associated with corrupt practices provide a clear guideline for public policy making. Developing countries such as Chile and Uganda that have enacted a simple procedural code while introducing alternative dispute resolutions have witnessed a reduction in the reports of court-related corruption. Moreover, the success stories of Singapore and Costa Rica show that corruption has been reduced by creating specialized administrative offices supporting the courts in matters related to court notifications, budget and personnel management, cash and case flows. These administrative support offices that were shared by many courts have decentralized administrative decision making while reducing the previously high and unmonitored concentration of organizational tasks in the hands of judges (Buscaglia 1997a).

C ORRUPTION AND I TS L ONG- T ERM I MPACT ON E FFICIENCY AND E QUITY

Some scholars have observed that official corruption generates immediate positive results for the individual citizen or organization who is willing and able to pay the bribe (Rosenn 1984). For example, Rose-Ackerman (1997) accepts that "payoffs to those who manage queues can be efficient since they give officials incentives both to work quickly and favor those who value their time highly." She further states that, in some restricted cases, widely accepted illegal payoffs need to be legalized (Rose-Ackerman 1997). This statement, however, disregards the effects that present entrenched corruption has on people's perception of social equity and on long-term efficiency. The widespread effects of corruption on the overall social system have a pernicious effect on efficiency in the long run. To understand this effect, an economic theory of ethics needs to be applied to the understanding of the long-term effects of corruption on efficiency.

The average individual's perception of how equitable a social system is has a pronounced effect on that individual's incentives to engage in productive activities (Buscaglia 1997a). The literature has delved into many of the negative impacts that corruption has on the efficient allocation of resources. Yet previous work does not pay attention to the effects that corruption has on the individual's perception of how equitable a social system is. First, in all developing countries, a vast majority of the population is not able to offer illicit payoffs to government officials, even when they are willing to do so (Buscaglia 1997a), and, second, legalizing illicit payoffs may have no impact on social behavior in societies where most social interactions are ruled not by modern laws but by multiple layers of customary and religious codes of behavior.

A significant impact of corruption on future efficiency is the effect that official corrupt practices have on the average citizen's perception of social equity. Homans (1974) shows that, in any human group, the relative status given to any member is determined by the "group's perception" of the member's contribution to the relevant social domain. Homans further states that changes in the relative wealth-related status of an individual member without a perceived change in his social contribution will face open hostility by the other members of society (e.g., envy may generate retaliation and destruction of social wealth). Therefore, within Homans's view, in cases of corrupt practices, a "socially unjustified" increase in the wealth-related status of those who offer and accept bribes represents a violation of the average citizen's notion of what constitutes an "equitable hierarchy" of status within society.

Homans's theory of ethics can be applied to the understanding of the effects of official systemic corruption on efficiency over time. Those members of society who are neither able nor willing to supply illicit incentives will be excluded from the provision of any "public good" (e.g., court services). In this case, even though corruption may remove red tape for those who are able and willing to pay the bribe, the provision of public services becomes inequitable in the perception of all of those who are excluded from the system due to their inability or unwillingness to become part of a corrupt transaction. This sense of inequity has a long-term effect on social interaction. Systemic official corruption promotes an inequitable social system where the allocation of resources is perceived to be weakly correlated to generally accepted rights and obligations. Buscaglia (1997a) shows that a "perceived" inequitable allocation of resources hampers the incentives to generate wealth by those who are excluded from the provision of basic public goods. The average citizen, who cannot receive a public service due to his inability to pay the illegal fee, ceases to demand the public good from the official system (Buscaglia 1997a). On many occasions, the higher price imposed by corrupt activities within the public sector forces citizens to seek alternative community-based mechanisms to obtain the public service (e.g., alternative dispute resolution mechanisms such as neighborhood councils). These community-based alternative private mechanisms, however, do not have the capacity to generate precedents in certain legal disputes affecting all society (e.g., human rights violations or constitutional issues) like the state's court system does. Hernando de Soto's account of these community-based institutions in Peru attests to the loss in a country's production capabilities owing to the high transaction costs of access to public services (de Soto 1989).

One may initially think that, by eliminating bureaucratic red tape, the payment of a bribe can also enhance economic efficiency. This is a fallacy, however, because corruption may benefit the individual who is able and willing to supply the bribe. As described above, however, the social environment is negatively affected by diminishing economic productivity over time becaue of the general perception that the allocation of resources is determined more by corrupt practices and less by productivity and, therefore, is inherently inequitable. This creates an environment where individuals, in order to obtain public services, may need to start seeking illicit transfers of wealth to the increasing exclusion of productive activities. In this respect, present corruption decreases future productivity, thereby reducing efficiency over time.

C ORRUPTION AND I NSTITUTIONAL I NERTIA

When designing anticorruption policies within the legal and judicial domains, we must take into account not only the costs and benefits to society of eradicating corruption in general but also the changes in present and future individual benefits and costs as perceived by public officials whose illicit rents will tend to diminish due to anticorruption public policies. Previous studies argue that institutional inertia in enacting reforms stems from the long-term nature of the benefits of reform in the reformers' mind, such as enhanced job opportunities and professional prestige (Buscaglia, Dakolias, and Ratliff 1995). These benefits cannot be directly captured in the short term by potential reformers within the government. Contrast the long-term nature of these benefits with the short-term nature of the main costs of reform, notably, a perceived decrease in state officials' illicit income. This asymmetry between short-term costs and long-term benefits tends to block policy initiatives related to public sector reforms. Reform sequencing, then, must ensure that short-term benefits compensate for the loss of rents faced by public officers responsible for implementing the changes. In turn, reform proposals generating longer-term benefits to the members of the court systems need to be implemented in later stages of the reform process (Buscaglia, Ratliff, and Dakolias 1996).

For example, previous studies of judicial reforms in Latin America argue that the institutional inertia in enacting reform stems from the long-term nature of the benefits of reform, such as increasing job stability, judicial independence, and professional prestige. Contrast the long-term nature of those benefits with the short-term nature of the main costs of judicial reform to reformers (e.g., explicit payoffs and other informal inducements provided to court officers). This contrast between short-term costs and long-term benefits has proven to block judicial reforms and explains why court reforms, which eventually would benefit most segments of society, are often resisted and delayed (Buscaglia, Dakolias, and Ratliff 1995). In this context, court reforms promoting uniformity, transparency, and accountability in the process of enforcing laws would necessarily diminish the court personnel's capacity to seek extra income through bribes. Reform sequencing, then, must ensure that short-term benefits to reformers compensate for the loss of illicit rents previously received by court officers responsible for implementing the changes. That is, initial reforms should focus on the public officials' short-term benefits. In turn, court reform proposals generating longer-term benefits need to be implemented in the later stages of the reform process.

Additional forces also enhance the anticorruption initiative. We usually observe that periods of institutional crisis come hand in hand with a general consensus among public officials to reform the public sector. For example, within the judiciary, a public sector crisis begins at the point where backlogs, delays, and payoffs increase the public's cost of accessing the system. When costs become too high, people restrict their demand for court services to the point where the capacity of judges and court personnel to justify their positions and to extract illicit payments from the public will diminish. At that point court officials increasingly embrace reforms in order to keep their jobs in the midst of public outcry (Buscaglia, Dakolias, and Ratliff 1996, 35). At this point, the public agency would likely be willing to conduct deeper reforms during a crisis as long as reform proposals contain sources of short-term benefits, such as higher salaries, institutional independence, and increased budgets.

It comes as no surprise, then, that those developing countries undertaking judicial reforms have all experienced a deep crisis in their court system, including Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, Hungary, and Singapore (Buscaglia and Dakolias 1999). In each of these five countries, additional short-term benefits guaranteed the political support of key magistrates who were willing to discuss judicial reform proposals only after a deep crisis threatened their jobs (Buscaglia and Ratliff 1997). Those benefits included generous early retirement packages, promotions for judges and support staff, new buildings, and expanded budgets.

Nevertheless, to ensure lasting anticorruption reforms, short-term benefits must be channeled through permanent institutional mechanisms capable of sustaining reform. The best institutional scenario is one in which public sector reforms are the by-product of a consensus involving the legislatures, the judiciary, bar associations, and civil society. Keep in mind, however, that legislatures are sometimes opposed to restructuring the courts in particular and other public institutions in general from which many of the members of the legislature also extract illicit rents.

This essay has provided a review of the most recent literature related to the economic causes of entrenched corruption within the public sector in general and particularly within the court systems in developing countries. This study stresses the need to develop scientific explanations of corruption containing objective and well-defined indicators of corrupt activities. Along these lines, this essay proposes that the joint effects of organizational, procedural, legal, and economic variables are able to explain the occurrence of corruption within the courts in developing countries.

Additionally, this essay describes how equity considerations by individuals affect long-term efficiency. Social psychologists could shed more light in future studies linking the impact of corruption on equity and efficiency. Finally, in order to understand and neutralize institutional inertia during anticorruption reforms, all future studies must incorporate the identification of those costs and benefits that are relevant to those who reform public sector institutions and are responsible for implementing new anticorruption policies.

The main question to be asked in the development of any anticorruption public policy approach is how to generate public policies based on sound and scientific principles that at the same time can be accepted and adopted by civil society and the public sector alike? The answer to this question is a necessary condition to developing a still absent international public policy consensus in the fight against corruption.

Andvig, Jens Christopher. 1989. "Korrupsjon i Utviklingsland" (Corruption in developing countries). Nordisk Tidsskrift for Politisk Ekonomi (Northern journal in political economy) 23: 51-70.

Becker, Gary. 1993. "Nobel Lecture: The Economic Way of Thinking about Behavior." Journal of Political Economy 108: 234-67

Becker, Gary, and George Stigler. 1974. "Law Enforcement, Malfeasance, and Compensation of Employees." Journal of Legal Studies 3: 1-18

Buscaglia, Edgardo. 1997a. "Corruption and Judicial Reform in Latin America." Policy Studies Journal 17, no 4: 273-95.

------. 1997b. "An Economic Analysis of Corrupt Practices within the Judiciary in Latin America." In Claus Ott and Georg Von Waggenheim, eds., Essays in Law and Economics V. Amsterdam: Kluwer Press.

------. 1995. "Stark Picture of Justice in Latin America." The Financial Times , March 21, p. A 13.

Buscaglia, Edgardo, and Maria Dakolias. 1999. "Comparative International Study of Court Performance Indicators: A Descriptive and Analytical Account." Legal and Judicial Reform Unit Technical Paper. The World Bank.

------. 1996. A Quantitative Analysis of the Judicial Sector: The Cases of Argentina and Ecuador . World Bank Technical Paper No 353. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Buscaglia, Edgardo, Maria Dakolias, and William Ratliff. 1995. Judicial Reform in Latin America: A Framework for National Development . Essays in Public Policy. Stanford: Hoover Institution.

Buscaglia, Edgardo, and Thomas Ulen. 1997. "A Quantitative Assessment of the Efficiency of the Judicial Sector in Latin America." International Review of Law and Economics 17, no 2.

Bussani, Mauro, and Ugo Mattei. 1997. "Making the Other Path Efficient: Economic Analysis and Tort Law in Less Developed Countries." In Law and Economics of Development , ed. Edgardo Buscaglia, William Ratliff, and Robert Cooter. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press.

Cooter, Robert. 1996. "The Rule of State Law and the Rule-of-Law State: Economic Analysis of the Legal Foundations of Development." In Law and Economics of Development , ed. Buscaglia, Ratliff, and Cooter.

de Soto, Hernando. 1989. The Other Path . New York: Harper and Row.

Gambetta, Diego. 1993. The Sicilian Mafia . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Homans, George C. 1974. Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms . New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Klitgaard, Robert. 1991. Adjusting to Reality: Beyond State versus Market in Economic Development . San Francisco: ICS Press.

Lambsdorff, Johann Graf. 1998. "An Empirical Investigation of Bribery in International Trade." European Journal of Development Research 10, no. 1 (June): 18-34.

Leiken, Robert S. 1996, "Controlling the Global Corruption Epidemic." Foreign Policy 5: 55-73.

Macrae, J. 1982. "Underdevelopment and the Economics of Corruption: A Game Theory Approach." World Development 10, no. 8: 677-87.

Mauro, Paolo. 1995. "Corruption and Growth." Quarterly Journal of Economics 110: 681-711

Ratliff, William, and Edgardo Buscaglia. 1997. "Judicial Reform: The Neglected Priority in Latin America." Annals of the National Academy of Social and Political Science 550: 59-71.

Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1997. "Corruption and Development." Manuscript.

------. 1978. Corruption: A Study in Political Economy . New York: Academic Press.

Shleifer, A., and R. W. Vishny. 1993. "Corruption." Quarterly Journal of Economics 108: 599-617

Smith, Adam. 1978. Lectures on Jurisprudence . Oxford, Eng.: Oxford University Press.

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

Corruption in Our Courts: What It Looks Like and Where It Is Hidden

Volume 133’s emerging scholar of the year: robyn powell, announcing the eighth annual student essay competition, announcing the ylj academic summer grants program.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

A Handful of Unlawful Behaviors, Led by Fraud and Bribery, Account for Nearly All Public Corruption Convictions Since 1985

A comprehensive analysis of nearly 57,000 corruption cases in federal courts spanning 30 years revealed that fraud and bribery dominated the types of conduct underlying criminal cases, accounting for 76% of the lead charges in cases resulting in convictions. Those two unlawful behavior types, combined with extortion and conspiracy, broadly informed the lead charges in virtually all examined corruption convictions in federal courts from 1985 to 2015.

That was a key finding of a case records study by a research team led by Jay S. Albanese of Virginia Commonwealth University. The purpose of the study, sponsored by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), was to fill a literature gap with empirically based knowledge of prosecution practices, corruption-fighting statutes, and types of behavior underlying prosecutions. New insights on corrupt behavior could inform new policies to prevent some corrupt conduct and discover some corrupt acts earlier. [1] The findings may also help the justice system focus crime prevention and enforcement strategies on those behaviors most often associated with criminal prosecution, and distinguish among types of corruption more likely to occur at the federal, state, or local level, the researchers said. [2]

All of the corruption case records examined came from federal courts, accessed in court and prosecutor databases, and the researchers compared cases in three different tiers: federal-level, state-level, and local-level corruption.

Corruption Crime Types Vary Among Government Levels

Fraud was the focus of corruption charges in 40.6% of all analyzed cases, with bribery accounting for the lead charge in 35.6% of cases. [3] But the prevalence of charged conduct categories varied somewhat depending on the level of government activity addressed in the prosecution. In federal-level corruption litigation, the first-charged conduct was fraud in 5,579 of 12,663 cases (44.1%) and bribery in 5,129 cases (41%). Similarly, in state-level cases, lead fraud charges outnumbered lead bribery charges, 1,112 cases (29.3%) to 1,070 (28%), out of a total of 3,792 state-level convictions. But in local-government corruption matters, lead bribery charges exceeded lead fraud charges, 2,421 cases (34%) to 2,051 (29%), out of 7,090 total convictions.

Extortion charges were a distant third among lead charges in federal- and local-level corruption cases in federal court, but extortion led all crime types charged in state-level matters. In those cases, extortion led fraud by 1,156 to 1,112 charge types (30% to 29%), with bribery trailing slightly at 1,070 (28%), out of the total of 3,792 state-level corruption charge types.

Together, the four prevalent categories of corrupt behavior — fraud, bribery, and extortion, along with conspiracy — “form the operational meaning of corruption in practice,” the researchers concluded. [4]

Drilling down, the team identified eight discrete corrupt activities, covering all public corruption, through a closer analysis of about 2,400 cases from 2013 to 2015. Those eight activities are: [5]

- Receipt of a bribe

- Solicitation of a bribe

- Contract fraud

- Embezzlement

- Official misconduct

- Obstruction of justice

- Violation of regulatory laws

The researchers noted a nexus between heightened corruption risk and public service at the state and, especially, local levels. They pointed out that public officials serving on government boards and councils, as well as in elected office and law enforcement positions, were often employed part time, undertrained, and undersupervised. The report on corrupt behavior types said that the “lack of professionalism” in the public officials’ roles and expectations “provided the space to exploit opportunities to enrich themselves.” [6]

Remedies for Corruption

The researchers propose several corruption remedies, including: [7]

- Transparency in contract award processes and government spending practices.

- Dual training of individuals on public duties to avoid having a single person authorizing and reviewing payments.

- Introducing mandatory ethics training for government entities.

- Better protections for whistleblowers.

- A focus on fairness in prosecutions.

- Mandatory ethics training for federal programs and state and local entities.

What Motivated Corruption?

A separate aspect of the research by Albanese and his colleagues was an empirical analysis of corruption defendants’ criminal motivation broken down into four categories: [8]

Positive — motivated by external factors, usually social or economic, that push the individual toward crime. An assumption underlying this explanation is that changing the influences on individuals will prevent crime.

Classical — an individual decision to maximize personal benefit through corrupt conduct; it can be deterred by increasing the threat of apprehension and punishment.

Structural — driven by systemic political and economic conditions; it can be deterred by legal and structural changes to election processes, balance of power, enforcement of laws, and due process.

Ethical — guided by individual decisions to act ethically or wrongfully; it can be deterred by education and reinforcement of ethical decisions.

For the corruption motivation analysis, researchers interviewed 72 individuals who have direct experience, in different capacities, with a variety of public corruption matters, [9] The themes that were discussed informed the coding of the interviews, and qualitative analysis software completed the evaluation.

Of the four corruption cause categories, ethical explanations led, at 38% of total explanations gleaned from the interviews and analysis; 28% offered a structural explanation; 19% offered a classical explanation; and 15% offered a positivist explanation.

About This Article

The research described in this article was funded by NIJ grant 2015-IJ-CX-0007, awarded to Virginia Commonwealth University. This article is based on three reports: the grantee Final Summary Overview on the project, “ Developing Empirically-Driven Public Corruption Prevention Strategies ” (2018), Jay S. Albanese, principal investigator; and two published articles, also written by members of the research team:

- Jay S. Albanese, Kristine Artello, and Linh Thi Nguyen, “ Distinguishing Corruption in Law and Practice: Empirically Separating Conviction Charges from Underlying Behaviors ,” Public Integrity 21 no. 1 (2019): 22-37.

- Jay Albanese and Kristine Artello, “Focusing Anti-Corruption Efforts More Effectively: An Empirical Look at Offender Motivation—Positive, Classical, Structural and Ethical Approaches,” Advances in Applied Sociology 8 no. 6 (2018): 471-485.

[note 1] , [note 2] , [note 3] , [note 6] , [note 7] Jay S. Albanese, Kristine Artello, and Linh Thi Nguyen, “Distinguishing Corruption in Law and Practice: Empirically Separating Conviction Charges from Underlying Behaviors,” Public Integrity 21 no. 1 (2019): 25.

[note 4] , [note 5] Jay Albanese, “Final Summary Overview: Developing Empirically-Driven Public Corruption Prevention Strategies,” Final Report to the National Institute of Justice, grant number 2015-IJ-CX-0007, 2018, 4.

[note 8] , [note 9] Jay Albanese and Kristine Artello, “Focusing Anti-Corruption Efforts More Effectively: An Empirical Look at Offender Motivation—Positive, Classical, Structural and Ethical Approaches,” Advances in Applied Sociology 8 no. 6 (2018): 471-485, at 478.

Cite this Article

Read more about:, related publications.

- Developing Empirically-Driven Public Corruption Prevention Strategies

Related Awards

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Corruption in the Judiciary: Balancing Accountability and Judicial Independence

Related Papers

Susan Rose-Ackerman

Scott Stafne

A non-corrupt judiciary is a fundamental condition for the endorsement of rule of law and the ability to guarantee basic human rights in society. The judiciary must therefore be an independent and fair body that fights corruption, not the other way around. This essay systematizes different binding and non-binding international, and to some extent regional, norms and standards regarding corruption in the judiciary and judicial independence, and presents potential factors and effects of judicial corruption, through an inventory of documents recognized by organizations such as the United Nations and the Council of Europe. Further, the essay presents different anti-corruption strategies and the dilemma of implementing such strategies with regard to judicial independence. The advantages and disadvantages of different anti-corruption strategies are reviewed through the study of some successful and unsuccessful examples. There are several definitions of corruption, this essay emanates from the definition of ‘abuse of office for personal or private gain’, a definition that is wide but yet well recognized. The factors of judicial corruption are many and often overlapping, but they vary from state to state and must hence be analyzed individually to find the factual reasons for what generates corruption. The effects are detrimental and break down the very core of rule of law and corrupt judges neglect fundamental principles such as equality, impartiality, propriety and integrity. With regard to the different factors and effects, the norms and standards, and the anti-corruption strategies, a discussion follows about how to rid the judiciary from corruption with preservation of the respect of judicial independence. The discussion also raises the predicament that malpractice of various fundamental principles e.g. judicial independence can occur and further distort unhealthy judiciaries. The main conclusion regarding anti-corruption strategies is that they must be carefully weighed against the principle of independence.

Dr. Marcos Iglesias , Andrew Banfield

When it comes to corruption, our first thoughts fly towards high level politicians that accept great amounts of money for favours that can go from millionaire building contracts, to simply sign a paper that can transform a natural space into a multi apartment building. In these cases, voters, those who initially trusted these politicians trust that the judicial system we be able to fight against corruption in any way necessary. Judicial independence becomes crucial when talking about corruption, court efficiency turns into a matter of great importance because of the need of judicial fairness when it comes to resolve corruption cases. Clerks can be bribed to slow down cases, but judges may also be tempted to accept a bribe to dismiss a case, or even pressure by the politician whom positioned him where he is in order to avoid being sentenced for an illegal act. The study of judicial corruption is to this extent of great importance, as is the way to have a totally independent judicial system to guarantee no possibility of legal unfairness. In order to do so, to completely different legal systems have been compared as to see how they deal with judicial independence and which is the perception citizens have of this independence when it comes to ask justice to protect their rights. How is judicial independence guaranteed? How is judicial corruption eradicated when encountered? This study sees in to different legal systems such as the Australian legal system, based on Common Law, and other European systems that base their existence on Roman law. It will compare the actual mechanisms that exist in order to prevent, detect and eradicate any possible case of corruption between those chosen, or selected, to dispense justice, to then compare the actual number of cases of judicial corruption in each country studied. The conclusions of the study will see which legal system has been most effective when it comes to deal with judicial corruption, which have been the most effective mechanisms implemented to fight against judicial corruption and if these are improvable in any way. The study will be done be comparing judicial sentences related to high level corruption in order to how being n power can affect the outcome. This would be related to inequality as to judicial independence due to the importance of the judicial system.

Christabella Judith Aceng

Corruption is not a novel phenomenon. It is gravely despised by society and is conceived as a social vice that needs to be tackled with great concern. This is because, corruption tendencies hinder peace, stability, sustainable development, democracy, and human rights around the globe. Corruption tendencies continue to consume various levels of society while leaving ruin. The judiciary has not been spared this sentiment. The Judiciary, the temple of justice is the peak for conflict resolution where citizens hope for redress through a fair, accessible efficient and effective justice process. Therefore, case of judicial corruption undermines the justice process and disregards the rule of law. The paper therefore seeks to address the component of judicial corruption. The structure of the discussion includes: the definition of judicial corruption while identifying which actors the concept refers to; the forms, causes, impact, instigating factors, legal framework strategies to cub judicial corruption, conclusion and recommendation.

Andre Thomashausen

Preventing and combating corruption in the judiciary Paper presented at the "Activism Against Corruption in Africa" Conference organised by Konrad Adenauer Foundation on 22-25 November 2016, Johannesburg South Africa. A reflection on 1. Judicial Corruption Perception in South Africa 2. National Legal Instruments 3. International Obligations 4. Extra-Judicial Watchdogs or Guardians 5. Anti-Corruption Watchdog Accountability 6. Causes of Judicial Corruption and their Remedies

International Review of Law and Economics

Stefan Voigt

Beijing Law Review

Felix Okiri

This study sought to underscore the central role of morals and ethics in reducing judicial corruption. The paper proceeded to study the concepts of integrity and corruption. Subsequently, the paper studied Kenya’s development and current law on integrity, public service and corruption and possible areas for reform. The study found out that despite near-adequate legislations , Kenya’s jurisprudence depicts a state of despair, lack of good will and numerous constraints in the anti-corruption process: many of the cases prosecuted in court have either been terminated by the courts or have not succeeded as a result of lack of political good will and political interference. The paper concluded that corruption is not only a legal issue but also a moral one—that is why major solutions to taming judicial corruption have flopped as a result of the linear approach to offering solutions. The paper found out that in order to offer formidable solutions to corruption in the judiciary, the legislative and policy approaches ought to be structured and conceptualized in a more realistic and feasible manner to that of ordinary obligations and offences. As a central point of interest, premium must be attached to integrity, as a moral concern, in order to offer sustainable solution to corruption in the judiciary.

This thesis presents an overview of the susceptibility of the Common Law system and the Civil Law system on corruption and their respective contribution to a judiciary possessing optimal degrees of internal and external independence. A judiciary with such independence is, on the one hand, a significant factor in the battle against corruption; on the other hand such a judiciary has the greatest likelihood of being immune from corruption itself. Since the Common and the Civil Law systems differ in the appointment system of judges and their mechanisms of checks and balances, each legal system has its advantages and disadvantages in terms of securing the judiciary an optimal degree of independence. Various existing, as well as a number of prospective features will be presented, which combine the advantages of the Common and Civil Law systems. These features would guarantee optimal levels of judicial independence, making the judiciary a strong player in the fight against corruption.

Columbia University Colloquium

This paper examines the correlation between judicial independence, and its historical consolidation in constitutional democracies, and corruption incidence in a comparative-historical approach between the countries of India, Brazil and the United States. Its goal is to assert whether increasing judicial independence has had a positive correlation with corruption control, and if so, how different institutional judicial structures alter this relationship.

Corruption, Grabbing and Development

Siri Gloppen

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Diana Budusan

Saminu Danbaki

Maya Elvira

SSRN Electronic Journal

Iman Mirzazadeh

Catharina Womack

THE CONTRIBUTION OF THE JUDICIAL SERVICE COMMISSION TO THE JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE, INTEGRITY, TRANSPARENCY, ACCOUNTABILITY AND THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE JUDICIAL SECTOR

Kudzai B Tapfuma

Emmanuel Yeboah-Assiamah

Atlantis Press

Eko Nursetiawan

International Journal of Professional Business Review

Andi Muhammad Asrun

Abdirashid Ismail

Commonwealth Law Bulletin

Nihal Jayawickrama

Korean Associaon of Internaonal Associaon of Constuonal Law

BAMISAYE OLUTOLA

Young Africa Research Journal

Walter K H O B E Ochieng

Max Planck Encyclopedia of Comparative Constitutional Law, Oxford University Press

Piotr Mikuli

IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science

Abdalrazak Alsheban

The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention

Fozia Shaheen

Perceptions of the Independence of Judges in Europe

Frans Van Dijk

Africa Journal of Comparative Constitutional Law

Oñati Socio-Legal Series

karin pedersen

David Ngira

Indian Journal of Law and Justice

Shaista Qayoom

KAS African Law Study Library - Librairie Africaine d’Etudes Juridiques

Alexander Saba

Luiz Pedone

JURIDICA INTERNATIONAL

Victoria Rodríguez-Blanco

Pranab Kharel , gaurab kc

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Doha Declaration

Unided nations office on drugs and crime.

- Education for Justice

- Judicial Integrity

- Prisoner Rehabilitation

- Crime Prevention through Sports

- Human Rights

- Partnerships

- Crime Congress 14

Corruption, Human Rights, and Judicial Independence

By Special Rapporteur Diego García-Sayán

The Honourable Diego Garcia-Sayán acts as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers. He was a judge of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and was elected Vice-President of the Court from 2008 to 2009 and President of the Court for two consecutive terms. He previously served as Peru's Minister of Justice and Minister of Foreign Affairs. Garcia-Sayán recently shared his views on corruption and judicial independence with UNODC as part of the Organization's on-going work on promoting judicial integrity. All opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author as an external expert and do not necessarily reflect the official position of UNODC.

______________________________

"Corruption has a direct impact on the validity of human rights, largely because of two reasons.

On one side, corruption deprives societies of important resources that could be used for basic needs, such as public health, education, infrastructure, or security. The OECD has indicated that the cost of corruption, in its different modalities, constitutes more than 5% of the global GDP.

On another side, corruption has direct damaging consequences in general on the functioning of state institutions, and in particular on the administration of justice. Corruption decreases public trust in justice and weakens the capacity of judicial systems to guarantee the protection of human rights, and it affects the tasks and duties of the judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and other legal professionals.

By seeking impunity, corruption has a devastating effect on the judicial system as a whole. One of the goals of human rights is to fight corruption and its implications on the administration of justice, as is to act against corruption through an independent and strong administration of justice. For this, the United Nations Convention against Corruption is a fundamental instrument for the protection of human rights.

In my report presented last year at the General Assembly, I established that "as a key tool to fight against corruption, the Convention should also be considered as a fundamental international instrument for the protection of human rights, and that it should merit, consequently, the permanent attention of the bodies competent in this matter". [1]

Corruption in the Judicial System

Corruption undermines the core of the administration of justice, generating a substantial obstacle to the right to an impartial trial, and severely undermining the population's trust in the judiciary.

Corruption has a variety of faces, bribery being only one of them, another being political corruption, much more unattainable and imprecise. Its broad range of action enables it not only to influence the judicial system, but all the sectors of state administration as well.

Illicit interferences with justice can also be violent, particularly when perpetrated directly by members of organised crime. These forays are intended to secure specific objectives, such as the closing of a particular case, or the acquittal of a given individual.

Corruption and the Historical Responsibility of Justice

Internal norms in different states and several relevant international instruments establish different ranges of obligations to confront corruption. However, while judicial systems are themselves the target of corruption and organised crime, it is precisely within judicial systems that societies have their main instrument to prevent and fight corruption.

Article 11 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption - a fundamental international treaty - emphasizes the decisive role of the judicial branch in the fight against corruption, and establishes that in order to carry out this role effectively, the judicial branch itself must be free of corruption, and that its members must act with integrity. Substantive guidelines on matters of internal organization, which are fundamental to prevent and confront corruption, have been included in the Convention.

There are core obligations in the Treaty on international cooperation between judicial and prosecutorial bodies of sovereign States (Chapter IV) which are unprecedented in a multilateral treaty. For example, it contains substantive and operational obligations in extradition matters, the transfer of convicted persons and judicial assistance, referral of criminal proceedings from one country to another, joint investigations, and, in general, clear substantive obligations in matters of cooperation for compliance with the law.

Judicial Integrity and the Fight against Corruption

In 2016, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime launched a global programme to promote a culture of lawfulness. It includes the creation of a Global Judicial Integrity Network to share best practices and lessons learned on the fundamental challenges and new questions relating to judicial integrity and the prevention of corruption.

This is an important step for the creation of a common language and a common perspective amongst different domains of the United Nations. In my capacity as Special Rapporteur, I have already expressed my full disposal to collaborate in the implementation of this programme."

[1] United Nations, A/72/140. 35 July 2017

Related Multimedia

Related Stories

Supported by the State of Qatar

60 years crime congress.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Why the Supreme Court Is Blind to Its Own Corruption

By Randall D. Eliason

Mr. Eliason is the former chief of the fraud and public corruption section at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia.

The scandal surrounding Justice Clarence Thomas has further eroded the already record-low public confidence in the Supreme Court. If Chief Justice John Roberts wonders how such a thing could have happened, he might start looking for answers within the cloistered walls of his own courtroom.

Over more than two decades, the Supreme Court has gutted laws aimed at fighting corruption and at limiting the ability of the powerful to enrich public officials in a position to advance their interests. As a result, today wealthy individuals and corporations may buy political access and influence with little fear of legal consequences, either for them or for the beneficiaries of their largess.

No wonder Justice Thomas apparently thought his behavior was no big deal.

He has been under fire for secretly accepting , from the Republican megadonor Harlan Crow, luxury vacations worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, a real estate deal (involving the home where his mother was living) and the payment of private school tuition for a grandnephew the justice was raising. Meanwhile, over the years, conservative groups with which Mr. Crow was affiliated filed amicus briefs in several matters before the Supreme Court .

That sounds like the very definition of corruption. But over the years, many justices — and not just conservatives — have championed a different definition.

The landmark case is the court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission . A five-justice majority — including Justice Thomas — struck down decades-old restrictions on independent campaign expenditures by corporations, holding that they violated the companies’ free speech rights. It rejected the argument that such laws were necessary to prevent the damage to democracy that results from unbridled corporate spending and the undue influence it can create.

The government’s legitimate interest in fighting corruption, the court held, is limited to direct quid pro quo deals, in which a public official makes a specific commitment to act in exchange for something of value. The appearance of potentially improper influence or access is not enough.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Insights IAS Brochure |

- OUR CENTERS Bangalore Delhi Lucknow Mysuru --> Srinagar Dharwad Hyderabad

Call us @ 08069405205

Search Here

- An Introduction to the CSE Exam

- Personality Test

- Annual Calendar by UPSC-2025

- Common Myths about the Exam

- About Insights IAS

- Our Mission, Vision & Values

- Director's Desk

- Meet Our Team

- Our Branches

- Careers at Insights IAS

- Daily Current Affairs+PIB Summary

- Insights into Editorials

- Insta Revision Modules for Prelims

- Current Affairs Quiz

- Static Quiz

- Current Affairs RTM

- Insta-DART(CSAT)

- Insta 75 Days Revision Tests for Prelims 2024

- Secure (Mains Answer writing)

- Secure Synopsis

- Ethics Case Studies

- Insta Ethics

- Weekly Essay Challenge

- Insta Revision Modules-Mains

- Insta 75 Days Revision Tests for Mains

- Secure (Archive)

- Anthropology

- Law Optional

- Kannada Literature

- Public Administration

- English Literature

- Medical Science

- Mathematics

- Commerce & Accountancy

- Monthly Magazine: CURRENT AFFAIRS 30

- Content for Mains Enrichment (CME)

- InstaMaps: Important Places in News

- Weekly CA Magazine

- The PRIME Magazine

- Insta Revision Modules-Prelims

- Insta-DART(CSAT) Quiz

- Insta 75 days Revision Tests for Prelims 2022

- Insights SECURE(Mains Answer Writing)

- Interview Transcripts

- Previous Years' Question Papers-Prelims

- Answer Keys for Prelims PYQs

- Solve Prelims PYQs

- Previous Years' Question Papers-Mains

- UPSC CSE Syllabus

- Toppers from Insights IAS

- Testimonials

- Felicitation

- UPSC Results

- Indian Heritage & Culture

- Ancient Indian History

- Medieval Indian History

- Modern Indian History

- World History

- World Geography

- Indian Geography

- Indian Society

- Social Justice

- International Relations

- Agriculture

- Environment & Ecology

- Disaster Management

- Science & Technology

- Security Issues

- Ethics, Integrity and Aptitude

- Insights IAS Brochure

- Indian Heritage & Culture

- Enivornment & Ecology

Insights into Editorial: India’s judiciary and the slackening cog of trust

Introduction:

Centrality of justice in human lives is summed up in a few words by the Greek philosopher, Aristotle: “ It is in justice that the ordering of society is centred .” Yet, a vast majority of countries have highly corrupt judiciaries.

Forms of Corruption in Judiciary:

Judicial corruption is inimical to judicial independence and to the constitutionally desired social order.

Judicial corruption takes two forms : political interference in the judicial process by the legislative or executive branch, and bribery.

Despite accumulation of evidence on corrupt practices, the pressure to rule in favor of political interests remains intense.

For judges who refuse to comply, political retaliation can be swift and harsh .

Bribery can occur throughout the chain of the judicial process: judges may accept bribes to delay or accelerate verdicts, accept or deny appeals, or simply to decide a case in a certain way.

Court officials coax bribes for free services; and lawyers charge additional “fees” to expedite or delay cases.