An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

How Psychological Safety Affects Team Performance: Mediating Role of Efficacy and Learning Behavior

1 Department of Business Administration, Seoul School of Integrated Sciences & Technologies (aSSIST), Seoul, South Korea

2 Department of Education, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, South Korea

Timothy Paul Connerton

3 Business School Lausanne, Chavannes, Switzerland

Associated Data

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

This article examines the mechanisms that influence team-level performance. It investigates psychological safety, a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking and a causal model mediated by learning behavior and efficacy. This model hypothesizes that psychological safety and efficacy are related, which have been believed to be same-dimension constructs. It also explains the process of how learning behavior affects the team’s efficacy. In a study of 104 field sales and service teams in South Korea, psychological safety did not directly affect team effectiveness. However, when mediated by learning behavior and efficacy, a full-mediation effect was found. The results show (i) that psychological safety is the engine of performance, not the fuel, and (ii) how individuals contribute to group performance under a psychologically safe climate, enhancing team processes. Based on the findings, this article suggests theoretical and methodological implications for future research to maximize teams’ effectiveness.

Introduction

Teams play a crucial role in highly effective organizations. Teams perform better than individuals ( Glassop, 2002 ), becoming sources for firms’ sustainable competitive advantage. Through horizontal interaction, the knowledge gained by teams contributes to performance on an organizational level ( Edmondson, 2012 ). There is a growing concern about how to improve the performance of teams in organizations. Although a large body of literature has focused on individual motivation over decades, research to advance the understanding of team motivation processes is insufficient ( Kozlowski and Bell, 2003 ; Chen and Kanfer, 2006 ).

From the literature, physical factors such as team size and task attributes, personal factors such as member competencies and personality, and organizational–environmental factors were studied as antecedents of team effectiveness (TEF) ( Cohen and Bailey, 1997 ; Mathieu et al., 2008 ). However, organizations are gradually recognizing the value of psychological assets, the importance of synergy among individuals and groups for innovation and growth in highly competitive markets ( Donaldson et al., 2011 ).

The concept of psychological safety appeared half a century ago in the organizational science field, but in recent years, empirical research flourished ( Frazier et al., 2017 ). Previous literature has shown that psychological safety has a direct influence on work performance ( Baer and Frese, 2003 ; Schaubroeck et al., 2011 ). Besides, more authors insisted that organizational support, safety climate, and performance are unquestionably related, implying that psychological safety might involve benefits that extend its influence on work engagement ( Rich et al., 2010 ; Christian et al., 2011 ).

Team psychological safety (TPS) is a shared belief that people feel safe about the interpersonal risks that arise concerning their behaviors in a team context ( Edmondson, 2018 ). “Project Aristotle,” which explored over 250 team-level variables, found that successful Google teams have five elements in common: psychological safety, dependability, structure and clarity, meaning, and impact of work ( Google, 2015 ). The findings argue that psychological safety is the most critical factor and a prerequisite to enabling the other four elements. However, surprisingly, despite the importance of that psychological factor, only 47% of employees across the world described that their workplaces are psychologically safe and healthy ( Ipsos, 2012 ).

As Edmondson (2018) pointed out, TPS is the engine of performance, not fuel. Various factors affect the mechanism in the underlying process. What we need to understand is “how” psychological safety leads to team performance. What is necessary for identifying such mechanisms are (i) extended, sustained research at group level and (ii) expansion of the studies in various contexts (e.g., country and culture). Notably, research conducted at the group level is insufficient compared to those conducted at the individual level in psychological safety literature. If related work continues and data accumulate, the theoretical background to examine the incremental validity issue at the group level will be intensified ( Frazier et al., 2017 ).

In many cases, psychological safety has been studied in limited regions (i.e., advanced economies in the west), and now the research context needs to be expanded ( Abror, 2017 ). There is a need to verify the influence of psychological safety on group performance, enhancing its explanatory potential and applicability in the workplace. Additional research is needed to determine what factors mediate the relationship between psychological safety and group effectiveness.

Psychological safety could affect behavioral outcomes such as team’s creativity ( Madjar and Ortiz-Walters, 2009 ), and both individual learning ( Carmeli and Gittell, 2009 ; Carmeli et al., 2009 ) and team learning ( Edmondson, 1999 ; Wong et al., 2010 ). Team learning behavior (TLB) is a symbolic variable that affects TEF. TLB is the process by which members interact, acquire knowledge and skills needed for their work, and share information ( Argote et al., 1999 ), and it raises the team process level to generate performance-oriented ideas. When members learn and improve their problem-solving skills, they can create a competitive organization ( Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000 ). Despite the mediating role of learning that has been empirically demonstrated in previous literature, it still needs to be dealt with as a research subject when considering the significance of learning in modern organizations.

Psychological safety has been linked to several attitudinal outcomes as well. Another factor that drives TEF is efficacy. Team efficacy (TE) is a member’s assessment of team ability to perform job-related activities successfully ( Walumbwa et al., 2004 ). Confidence in the team’s abilities affects performance and aligns the members’ activities on the team level ( Gibson et al., 2000 ; Gully et al., 2002 ). However, few studies have reported the effects of psychological safety to efficacy to present ( Abror, 2017 ). Therefore, there is a theoretical implication to see how efficacy mediates the relationship between psychological safety and performance at the group level. We selected the team’s learning behavior and efficacy as mediating variables to understand the mechanism for creating TEF. Despite the extensive research and empirical support for the critical role of psychological safety, a few unclear questions remain: How does psychological safety affect TEF? How does it affect learning behavior and efficacy? How does learning behavior mediate the overall relationship, and how does it affect the team’s efficacy? Does TE mediate between psychological safety and TEF?

Our aim in this research is to contribute to the team and psychological safety literature in three ways: (i) bring team literature together with related theories by examining psychological safety and learning behavior as determinants of TE; (ii) extend the TEF model and the traditional input–process–output (I–P–O) framework ( Hackman, 1987 ; Cohen and Bailey, 1997 ) by integrating psychological safety (as contextual input), learning behavior, and efficacy (as process and team traits) that might stimulate TEF; and (iii) embrace TE as a possible mediator between psychological safety and TEF creation.

Literature Review and Research Model

Psychological safety is “a condition in which one feels (a) included, (b) safe to learn, (c) safe to contribute, and (d) safe to challenge the status quo , without fear of being embarrassed, marginalized or punished in some way” ( Clark, 2019 ). TPS is a group variable that describes team context. In the last decade, the concept of psychological safety started attracting attention as a primary factor in predicting TEF.

Results from several empirical studies conducted in various regions and countries show that psychological safety plays a vital role in workplace effectiveness ( Edmondson and Lei, 2014 ). The psychological safety of individuals and their teams’ psychological safety are different constructs ( Baer and Frese, 2003 ). The concept was first pioneered by Schein and Bennis (1965) in organizational phenomena and developed by Kahn (1990) as a representative definition of the psychological safety of an individual.

Creating a psychologically safe workplace is different from being undisciplined or being unconditionally generous to any process or outcome ( Edmondson, 2012 ). Two factors—psychological safety and accountability for performance—identify four types of teams. In this regard, the presence of TPS does not necessarily mean that TEF will increase automatically.

Prior research also focused on the relationship between psychological safety and outcomes such as innovation, employee attitudes, creativity, knowledge sharing, voice behaviors, and communication ( Newman et al., 2017 ). Overall, TPS is known to have a positive association with TEF ( Schaubroeck et al., 2011 ; Kessel et al., 2012 ; Newman et al., 2017 ).

Extant literature has found positive associations between psychological safety and learning behavior at different levels ( Newman et al., 2017 ). Several pieces of empirical evidence on such relationships were found in previous literature at the team level ( Roberto, 2002 ; Van den Bossche et al., 2006 ; Stalmeijer et al., 2007 ; Bstieler and Hemmert, 2010 ; Ortega et al., 2010 ; Wong et al., 2010 ) and individual level.

In addition to this, the relationship between TPS and efficacy should be confirmed. Abror (2017) argues that TPS affects group efficacy. The author criticized Edmondson (1999) for putting TPS and TE on the same level and argued for the need to identify the relationship between the two factors. Recent studies started arguing that TPS may affect group efficacy ( May et al., 2004 ; Roussin et al., 2016 ; Hernandez and Guarana, 2018 ). TPS appears to have a significant effect on team behavior and goal orientation and improves performance while affecting a team’s efficacy ( Roussin et al., 2016 ). The following hypotheses arise from the above background.

- H1: TPS positively affects TEF.

- H2: TPS positively affects TLB.

- H3: TPS positively affects TE.

Discussions on team learning arose since Argyris (1986) defined organizational learning and discussed it as a sub-element of a learning organization. Edmondson (1999) used the term “team learning behavior” to distinguish the learning process from learning outcomes.

Team learning behavior is defined as gaining and sharing skills, knowledge, and information about work through the interaction of members ( Argote et al., 1999 ), an iterative team process leading to a change ( van Offenbeek, 2001 ). Gibson and Vermeulen (2003) defined TLB as a process of experimentation, reflective communication, and codification. The three elements are interdependent and difficult to replace. Edmondson et al. (2007) divided the perspective on team learning research into three streams.

Previous literature has shown that there is a positive relationship between TLB and TEF. Zellmer-Bruhn and Gibson (2006) identified the factors that influence team learning, team learning’s effects on task performance, and interpersonal relationships. TLB had a positive effect on TE. Van den Bossche et al. (2006) studied how teams build shared beliefs in a collaborative learning environment and found that team learning improves the perceived performance of a team.

Team learning behavior is also known to be positively associated with the team’s efficacy (i.e., van Emmerik et al., 2011 ). However, further research is needed to verify the direction of the causal relationship between the two variables.

This study views TLB as a process variable and identifies the relationship between TPS and TEF. Also, TLB’s mediating role between TPS and TE would be identified to confirm its value as a useful predictive tool. This section raises the following hypotheses:

- H4: TLB positively affects TEF.

- H5: TLB positively affects TE.

TE has a vital role in team research ( Rico et al., 2011 ). As the importance of creating team-based outcomes has grown, TE has attracted the interest of researchers ( Day et al., 2009 ).

Efficacy is the belief that an individual’s ability or competency to perform a particular task will produce a successful outcome ( Bandura, 1986 , 1997 ). When expanded into a group level, it becomes group efficacy, which is the belief of group members that they can accomplish a given task. TE is unlikely to be the sum of individual competence and self-esteem ( Bandura, 2000 ).

The concept of TE, together with team resilience and team optimism, is a representative sub-construct of positive organizational behavior ( West et al., 2009 ). It is an essential antecedent predicting group performance ( Werner and Lester, 2001 ; Gully et al., 2002 ; Chen et al., 2005 ; Tasa et al., 2007 ; Porter et al., 2011 ; Zoogah et al., 2015 ). The literature supports that efficacy coordinates group processes, such as decision-making and team communication. The level of belief can lead to different outcomes, even under the same conditions. Several empirical works have proved the effect of TE on team performance ( Mathieu et al., 2008 ). In the TE literature, it appears to influence TEF.

As such, we predicted that TE would activate collective processes and impact group performance. Teams that believe they can succeed in a given task can perform better. TE is expected to play an indispensable role in achieving crucial tasks that require enhanced team performance.

- H6: TE positively affects TEF.

Concepts such as team performance, characteristics, and attitudes of team members define TEF in a comprehensive way ( Shen and Chen, 2007 ). It is difficult to measure or give TEF one single definition. In earlier literature of TEF, the majority of studies defined “effectiveness” as physical outcomes. However, it gradually expanded to the concept of team performance, characteristics, or member attitudes ( Shen and Chen, 2007 ). Lin et al. (2005) insist that researchers should pay attention to various factors simultaneously at the individual and organizational levels to maximize performance.

Rousseau et al. (2006) summarized studies dealing with individual-level variables that improve TEF. As noted, the effectiveness criteria for defining a team’s performance are not limited to the team’s physical output. In addition to productivity, most studies adopted team member satisfaction, attitudes, and perceived outcomes as essential measures. The most widely used are performance and attitude aspects. In this study, TEF is measured by a team’s perception of their performance. Team performance is the result of a dynamic process of member interaction. In-role behavior describes a state in which team members play a supportive role in achieving goals ( Williams and Anderson, 1991 ). Surveys are common ways to measure perceived team performance ( Pearce and Sims, 2002 ; Pearce and Herbik, 2004 ). In this study, in-role behavior will measure TEF.

Theoretical Framework and the Moderating Role of TLB and TE

The theoretical foundation can be put on the social cognitive theory ( Bandura, 1988 ). According to the theory, learning is a cognitive process taking place in a social context and could occur purely via observation or instruction, even without direct reinforcement. Also, one’s sense of efficacy can play a crucial role in approaching goals, tasks, and challenges ( Luszczynska and Schwarzer, 2005 ). The theory adequately describes the mechanism of how psychological safety leads to its outcome variables and the relationship between behavioral changes and cognitive beliefs.

Psychological safety at the group level as a model of TEF uses some forms of the input–process–output (I–P–O) model as a theoretical framework. The I–P–O model is an approach that explains the mechanism of team outcome creation. It was Gladstein (1984) and Hackman (1987) who introduced the I–P–O model to explore the mechanism, and Cohen and Bailey (1997) further expanded the model to the TEF model. This framework suits the structural mediation process that involves TLB and TE as process variables for the research. The framework is still valid in many effectiveness research ( Liu et al., 2010 ; Dulebohn and Hoch, 2017 ; Escribano et al., 2017 ; Mansikka et al., 2017 ).

Team learning behavior is known to mediate the relationship between psychological safety and performance ( Edmondson, 1999 ; Li and Yan, 2009 ; Brueller and Carmeli, 2011 ; Kostopoulos and Bozionelos, 2011 ; Hirak et al., 2012 ; Huang and Jiang, 2012 ; Li and Tan, 2013 ; Ortega et al., 2014 ). Sanner and Bunderson (2013) found in their meta-analysis that TLB was a significant mediator in a large body of literature. In this regard, we try to confirm TLB’s mediating role in the TEF creation mechanism.

Bandura (1988) identified factors that affect efficacy. Social persuasion is encouragement or discouragement from another person. Also, psychological factors alter the level of efficacy. As noted earlier in the literature review, the team’s efficacy affects the performance ( Luszczynska and Schwarzer, 2005 ), and TLB affects TE.

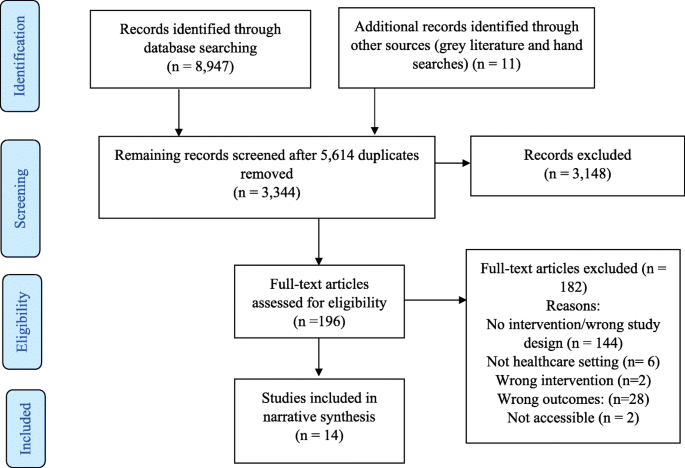

As such, this study investigates the following mediation effects. The hypothesized relationships of the research model (see Figure 2 ) are as follows:

Research model.

Psychological safety-accountability for performance framework. Source: Edmondson (2012 : 174).

- H7: TLB mediates the relationship between TPS and TE.

- H8: TE mediates the relationship between TPS and TEF.

- H9: TLB and TE jointly mediate the relationship between TPS and TEF.

Research Methodology

We collected samples from 16 local sales and service companies located in 98 outlets in South Korea. The survey targeted sales, service, and admin staff working at the front line. Under normal working conditions, field employees providing customer service have to work with a high level of customer orientation, with their service level evaluated continuously. Besides, they are exposed to complaints from dissatisfied customers and feel pressure about their performance, resulting in significant anxiety and stress. Therefore, fieldwork teams were considered appropriate for the research.

A mobile survey was sent to a total of 282 teams and 1,433 employees. Five hundred thirty-six questionnaires were recovered (37%), and 529 valid samples were analyzed. Frequency analysis was performed to examine the distribution of respondents (see Table 1 ).

Demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Attributes | Frequency | (%) | Attributes | Frequency | (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 465 | 87.9 | Tenure in team (months) | Under 6 | 87 | 16.4 |

| Female | 64 | 12.1 | 6∼12 | 80 | 15.1 | ||

| Age | Under 30 | 120 | 22.7 | 13∼24 | 94 | 17.8 | |

| 30∼35 | 142 | 26.8 | 25∼36 | 59 | 11.2 | ||

| 35∼40 | 133 | 25.1 | Above 37 | 209 | 39.5 | ||

| 40∼50 | 132 | 25.0 | Team function | Admin | 55 | 10.4 | |

| Above 50 | 2 | 0.4 | Sales | 236 | 44.6 | ||

| Tenure in company (years) | Under 3 | 222 | 42.0 | Service | 238 | 45.0 | |

| 3∼5 | 132 | 25.0 | Team size | 5 | 149 | 28.2 | |

| 5∼10 | 121 | 22.9 | 5∼7 | 253 | 47.8 | ||

| 10∼15 | 41 | 7.8 | 8∼10 | 80 | 15.1 | ||

| Above 15 | 13 | 2.5 | 11∼14 | 22 | 4.2 | ||

| Title | Staff | 207 | 39.1 | Above 15 | 25 | 4.7 | |

| AM | 126 | 23.8 | Education | High school | 109 | 20.6 | |

| MGR | 96 | 18.1 | Associate degree | 200 | 37.8 | ||

| AGM | 73 | 13.8 | Bachelor’s degree | 206 | 38.9 | ||

| Above GM | 27 | 5.1 | Master’s degree | 11 | 2.1 | ||

| Total | 529 | 100.0 | Doctor’s degree | 3 | 0.6 | ||

| No. of members (mean) | 4.5 | Member’s age (mean) | 31 | ||||

Respondents had the following characteristics: gender, 465 male (87.9%) and 64 female (12.1%); age, 30s group highest (26.8% for 30–35 and 25.1% for 35–40), mean = 31; title, staff level highest (39.1%); tenure, under 3 years (42.0%); tenure in the team, 3 years or above (39.5%); team size, less than five members (28.2%), mean = 4.5; team function, admin (10.4%), sales (44.6%), and service (45.0%); and education, bachelor’s degree (38.9%).

Measurements

Original measurements developed in English were translated to Korean and reviewed by HRD professionals and a group of Ph.D. students to ensure accuracy in the delivery of the meaning. All 27 items adopted a Likert 7-point scale, from 1 = not at all to 7 = to a large extent. TPS consisted of seven questions by Edmondson (1999) . Sample items were as follows: “Members are criticized when making a mistake,” “Members often ignore individual’s opinion,” and “Members do not degrade other people’s efforts.”

Team learning behavior adopted nine items from Gibson and Vermeulen (2003) . Sample items were as follows: “The team’s ideas and practices are introduced to other teams,” “Members exchange ideas,” and “The team leaves documents about the details of work.”

For measuring TE, we adjusted six items by Riggs and Knight (1994) . Sample items were as follows: “Members have the best work skills,” “Members have above-average ability,” “The team has excellent performance compared to other teams.”

Team effectiveness was adapted from Williams and Anderson (1991) , with the following sample items: “Fulfilling responsibilities given by the organization,” “Achieving the level of task that we expect,” and “Meeting official performance requirements” (see Table 2 and Appendix 1 ).

Measurement items of the construct.

| Variable | No. | Scale | Source | ||

| Independent | Team psychological safety | 7 | Likert 7-point | ||

| Mediator | Team learning behavior | Experimentation | 3 | ||

| Reflective communication | 3 | ||||

| Codification | 3 | ||||

| Team efficacy | 6 | ||||

| Dependent | Team effectiveness (in-role behavior) | 5 | |||

Analytical Procedure

Process Macro 3.3 was used for the mediated regression model, and Jamovi 1.0.0.0 was used for other analytical procedures, including exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and CFA. First, the demographic distribution was confirmed by frequency analysis. Second, the normality of distribution was tested by descriptive analysis. Third, EFA was carried out to test the variance. Fourth, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) secured the validity and reliability of the measurement model. Fifth, we tested the reliability and validity of each team’s value through ICC and R wg tests to clear level issues. Sixth, the regression analysis confirmed the relationships between variables. Seventh, statistical significance was confirmed by bootstrap replications. It verified the mediating effects and effect size within the relationships.

There is a possibility of common method bias (CMB) when measuring constructs in the same survey. This issue can lead to the structural underestimation or overestimation of the coefficients ( Bido et al., 2017 ). As criticized by Guide and Ketokivi (2015) , researchers should be careful about claiming that the issue is cleared after conducting weak tests, such as Harman’s (1967) . In this case, EFA is considered a legitimate statistical procedure to test CMB that supplements the weaknesses of Harman’s, considering both the structural model and the measurement model ( Bido et al., 2017 ). Also, when trying to identify a potential structure or to ensure if the measurements reflected the construct accurately, an additional EFA procedure could be considered, regardless of existing theoretical backgrounds ( Fabrigar and Wegener, 2012 ).

In this study, the maximum likelihood method and oblimin rotation were applied to extract the factors. In the process, variables that did not meet the criteria were removed (factor loadings less than 0.50 and communality less than 0.40). The results of Cronbach’s α confirmed the reliability of measurement instruments (see Table 3 ).

Result of exploratory factor analysis.

| Item | Factor loading | Communality | Cronbach’s α | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| TPS_1 | – | – | – | 0.682 | 0.510 | 0.793 |

| TPS_2 | – | – | – | 0.361 | 0.324 | |

| TPS_3 | – | – | – | 0.689 | 0.622 | |

| TPS_5 | – | – | – | 0.600 | 0.568 | |

| TLB _ex_1 | 0.621 | – | – | – | 0.787 | 0.922 |

| TLB_ex_2 | 0.647 | – | – | – | 0.705 | |

| TLB_ex_3 | 0.641 | – | – | – | 0.543 | |

| TLB_com_3 | 0.519 | – | – | – | 0.791 | |

| TLB_cod_1 | 0.758 | – | – | – | 0.545 | |

| TLB_cod_2 | 0.847 | – | – | – | 0.696 | |

| TLB_cod_3 | 0.810 | – | – | – | 0.604 | |

| TE_1 | – | 0.885 | – | – | 0.787 | 0.925 |

| TE_2 | – | 0.755 | – | – | 0.742 | |

| TE_4 | – | 0.819 | – | – | 0.715 | |

| TE_5 | – | 0.608 | – | – | 0.704 | |

| TE_6 | – | 0.622 | – | – | 0.727 | |

| TEF_1 | – | – | 0.621 | – | 0.713 | 0.916 |

| TEF_3 | – | – | 0.864 | – | 0.813 | |

| TEF_4 | – | – | 0.886 | – | 0.728 | |

| TEF_5 | – | – | 0.618 | – | 0.760 | |

| Eigen value | 4.126 | 3.799 | 3.107 | 2.353 | – | – |

| Variance (%) | 20.631 | 18.996 | 15.533 | 11.767 | 66.927 | – |

It was confirmed that the measurements constituting the four theoretical constructs were grouped into factors without difficulty, and the factor loadings and construct reliability (CR) were also found to be significant. The Bartlett test result showed that the model had a good fit ( P < 0.001), and the KMO statistics were 0.960, which is also acceptable. TPS question 2 showed a low communality level and was further reviewed for use in the following CFA. Finally, the model was used for CFA after removing three questions from TPS, one from TE, two from TLB, and one from TEF.

CFA was conducted to confirm the fit of the measurement model. The criteria for model fit are a chi-square NC (CMIN/ df ) of 5.0 and below, an absolute fitness index (SRMR) below 0.08, an RMSEA below 0.10, and incremental fitness index, TLI, and CFI above 0.90.

The average variance extracted (AVE) value ranged from 0.519 to 0.735, indicating that all variables met the criteria of 0.50 ( Bagozzi and Yi, 1988 ). The internal consistency of Cronbach’s α coefficient was found to be reliable, with all variables above 0.70 or higher ( Murphy and Davidshofer, 1988 ). The standard factor loadings of most items except for one item from TPS and two from TLB were above the recommended level of 0.70 and were significant ( P < 0.001) ( Hair et al., 2017 ). All the items in CFA were adopted, considering overall AVE ( Bagozzi and Yi, 1988 ). From the above analysis results, the measurement model is acceptable, showing an appropriate level of reliability.

The model fit details are as follows. From the results of χ 2 = 650 ( P < 0.001), NC (CMIN/ df ) = 3.963, TLI = 0.933, CFI = 0.942, SRMR = 0.044, and RMSEA = 0.075, no item showed lack in model fit criteria. The reliability analysis results are as shown in Table 4 .

Result of confirmatory factor analysis.

| Factor | Indicator | Estimate | Std. estimate | SE | -value | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

| TPS | TPS_1 | 1.000 | 0.705 | – | – | 0.809 | 0.519 | 0.793 |

| TPS_2 | 0.758 | 0.568 | 0.066 | 11.600*** | ||||

| TPS_3 | 0.956 | 0.812 | 0.056 | 17.000*** | ||||

| TPS_5 | 0.928 | 0.772 | 0.060 | 15.400*** | ||||

| TLB | TLB_ex_1 | 1.000 | 0.899 | – | – | 0.921 | 0.627 | 0.922 |

| TLB_ex_2 | 0.894 | 0.846 | 0.032 | 27.600*** | ||||

| TLB_ex_3 | 0.805 | 0.734 | 0.038 | 21.100*** | ||||

| TLB_com_3 | 0.934 | 0.892 | 0.030 | 31.400*** | ||||

| TLB_cod_1 | 0.769 | 0.682 | 0.041 | 18.600*** | ||||

| TLB_cod_2 | 0.921 | 0.780 | 0.040 | 23.300*** | ||||

| TLB_cod_3 | 0.824 | 0.675 | 0.045 | 18.200*** | ||||

| TE | TE_1 | 1.000 | 0.873 | – | – | 0.927 | 0.719 | 0.925 |

| TE_2 | 1.033 | 0.864 | 0.038 | 27.300*** | ||||

| TE_4 | 0.953 | 0.832 | 0.038 | 25.400*** | ||||

| TE_5 | 0.894 | 0.836 | 0.035 | 25.500*** | ||||

| TE_6 | 1.130 | 0.834 | 0.045 | 25.300*** | ||||

| TFE | TEF_1 | 1.000 | 0.844 | – | – | 0.917 | 0.735 | 0.916 |

| TEF_3 | 1.197 | 0.879 | 0.046 | 26.000*** | ||||

| TEF_4 | 1.168 | 0.823 | 0.050 | 23.300*** | ||||

| TEF_5 | 1.160 | 0.881 | 0.045 | 25.900*** | ||||

| Criteria | – | – | Under 5.0 | Above 0.90 | Above 0.90 | Under 0.08 | Under 0.10 | Interval |

| Result | 650 | 164 | 3.963 | 0.933 | 0.942 | 0.044 | 0.075 | 0.069∼0.081 |

Validity of the Constructs

Convergent validity and discriminant validity were verified to confirm the validity of the construct. Convergent validity is verified by factor loading, CR, and AVE. Convergent validity was confirmed from the measurement model as all the constructs were found to be higher than 0.50 in factor loading, 0.70 in CR, and 0.50 in AVE (see Table 5 ).

Test of convergent validity.

| Item | Factor loading | CR | AVE | |||

| Criteria | Above 0.50 | Above 0.70 | Above 0.50 | |||

| Accepted | Accepted | Accepted | ||||

| TPS | 0.714 | TPS | 0.809 | TPS | 0.519 | |

| TLB | 0.787 | TLB | 0.921 | TLB | 0.627 | |

| TE | 0.848 | TE | 0.927 | TE | 0.719 | |

| TEF | 0.857 | TEF | 0.917 | TEF | 0.735 | |

Discriminant validity means that latent variables are constructs that are independent of each other. If the correlation between factors is relatively high (above 0.80 or 0.85), the researcher can consider a more parsimonious model ( Brown, 2015 ). The results of correlation analysis among the factors are presented (see Table 6 ).

Correlations between dimensions.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. TPS | 5.748 | 1.249 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 2. TLB | 5.044 | 1.177 | 0.728*** | 1 | – | – |

| 3. TE | 5.615 | 1.109 | 0.750*** | 0.769*** | 1 | – |

| 4. TEF | 5.669 | 1.069 | 0.630*** | 0.772*** | 0.857*** | 1 |

The r ± 2SE method was applied to verify discriminant validity. This method adds and subtracts two standard error range from the correlation values of each factor and checks whether the value includes 1 in the range. The absence of 1 in the calculation range verifies the discriminant validity ( Fornell and Larcker, 1981 ). The r ± 2SE range of correlations among all factors did not include 1 (see Table 7 ).

Test of discriminant validity by r ± 2SE method.

| SE | - (2 × SE) | + (2 × SE) | Including 1 | ||

| TPS ↔ TE | 0.750 | 0.026 | 0.698 | 0.802 | N |

| TPS ↔ TLB | 0.728 | 0.027 | 0.674 | 0.782 | N |

| TPS ↔ TEF | 0.630 | 0.033 | 0.564 | 0.696 | N |

| TLB ↔ TE | 0.769 | 0.021 | 0.727 | 0.811 | N |

| TE ↔ TEF | 0.857 | 0.016 | 0.826 | 0.888 | N |

| TLB ↔ TEF | 0.772 | 0.021 | 0.729 | 0.815 | N |

Level Issue

This study assumes a team-level analysis. Klein et al. (1994) collectively defined three “level issues” that arise in group-level research, which are the level of theory, level of measurement, and level of analysis ( Klein et al., 1994 ). In this study, all the questionnaires measure the team’s view based on a reference-shift model. In the case of using the results of summed or averaged individual responses as a team value, there are two additional requirements as follows.

First, the group members’ responses must be consistent and show homogeneity. Second, the variation or variance between teams should be higher than that within a team. To prove this, Klein and Kozlowski (2000) proposed R wg (within-group interrater reliability), intraclass correlation (ICC)(1), and ICC(2). These are the methodologies that support inference for aggregation of individually collected data. This study conducted essential statistical procedures to resolve the level issues before aggregating individual values into a team value.

Checking the consistency and consensus of each rater’s answer to the question solves the problem. ICC is a standard method used for reliability verification in multilevel studies ( James, 1982 ). Reliability refers to the degree of consistency that an individual rater’s evaluation has, and there are two kinds, ICC(1) and ICC(2). Both use analysis of variance to verify data consistency. The usual cutoff level for ICC(1) is 0.20. ICC(2) further supplements ICC(1). It analyzes each group’s composite rating to verify the reliability and is acceptable at 0.60 or higher. The ICC(1) result shows that TEF did not meet the criteria, and TLB and TEF were not acceptable by ICC(2) baseline (see Table 8 ).

Test of level issue: ICC and r wg values.

| Factor | ICC(1) | ICC(2) | AVG. | -value |

| TPS | 4.340*** | |||

| TLB | 0.572 | 2.335*** | ||

| TE | 2.717*** | |||

| TEF | 0.144 | 0.431 | 1.757*** |

R wg is an additional verification procedure for the variables which did not meet baseline values. R wg , also referred to as the within-group agreement index, checks for consistency or reliability of lower-level data ( James et al., 1993 ). Its baseline is 0.70 or higher ( James et al., 1993 ; Klein and Kozlowski, 2000 ), but variables with R wg values higher than 0.50 can be aggregated as a team’s value ( James et al., 1993 ). Finally, a total of 104 team data were analyzed after excluding teams with less than three members and whose R wg values did not meet the requirements.

Hypothesis Test

Relationship between variables.

A process analysis was conducted to verify the effect size on direct and indirect effects simultaneously ( Hayes, 2013 ). By default, a thousand resampling of the percentile bootstrapping method is used to estimate the parameters. The absence of 0 in the 95% confidence interval identifies statistical significance ( Preacher et al., 2007 ; Hayes, 2013 ). The analysis was carried out based on the Hayes (2013) procedure to verify all the relationships and the direct and indirect effects.

The direct effect of TPS on TE was not significant (H1, β = 0.037). As expected, psychological safety activates team processes but may not direct driver of performance ( Edmondson, 2008 ). TPS had a positive effect on TLB (H2, β = 0.747) and had a significant positive effect on TE (H3, β = 0.596). The result was consistent with previous researches that a sense of safety has a significant impact on team behavior change and performance.

Also, TLB had a positive effect on TE (H4, β = 0.317). The learning process affected the team’s efficacy, which is the team’s emotional response. TLB had a positive effect on TEF (H5, β = 0.193) and was consistent with previous studies’ results that learning improves the quality of task performance.

Finally, the positive effect on TEF of TE was confirmed (H6, β = 0.694). In summary, TPS did not directly affect effectiveness but had a positive effect on other variables. In the other causal paths, positive causal relationships were identified (see Figure 3 and Table 9 ).

Result of main effect analysis.

| Hypothesis | Path | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Remarks | |

| H1 | TPS → TEF | 0.037 | 0.064 | 0.413 | (0.100) | 0.153 | Rejected |

| H2 | TPS → TLB | 0.747 | 0.060 | 11.349*** | 0.563 | 0.801 | Accepted |

| H3 | TPS → TE | 0.596 | 0.063 | 7.788*** | 0.367 | 0.618 | Accepted |

| H4 | TLB → TE | 0.317 | 0.069 | 4.149*** | 0.150 | 0.425 | Accepted |

| H5 | TLB → TEF | 0.193 | 0.060 | 2.513* | 0.032 | 0.268 | Accepted |

| H6 | TE → TEF | 0.694 | 0.079 | 7.520*** | 0.438 | 0.752 | Accepted |

Research model with regression coefficient values. ns: not significant.

Mediating Effect

For the mediating effects to be statistically significant, the indirect effect must show significance in the relationship of the independent variable to the dependent variable. If only the indirect effect is significant in a proposed model, it is a full-mediation effect. In a partial-mediation model, both indirect and direct effects are significant.

The mediating effect of TLB was identified between TPS and TEF (H7, β = 0.144). Also, the mediating role of TE was verified between TPS and TEF (H8, β = 0.413). The effect size was confirmed, and the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval did not contain 0. TLB and TE showed a double-mediation effect on the relationship between TPS and TEF (H9, β = 0.165).

The total effect of the research model was significant (β = 0.722). The applicability of the research model was supported, and TE was found to have the most substantial indirect effect. The results of the mediation effect analysis are presented (see Table 10 ).

Total, direct, indirect effect of research model.

| Hypothesis | Effect | Path | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Remarks |

| Total | TPS → TEF | 0.722 | 0.077 | 0.556 | 0.861 | Full mediation | |

| Direct | TPS → TEF | 0.037 | 0.064 | (0.100) | 0.153 | – | |

| H7 | Indirect 1 | TPS → TLB → TEF | 0.144 | 0.070 | 0.009 | 0.276 | Accepted |

| H8 | Indirect 2 | TPS → TE → TEF | 0.413 | 0.074 | 0.283 | 0.562 | Accepted |

| H9 | Indirect 3 | TPS → TLB → TE → TEF | 0.165 | 0.056 | 0.069 | 0.286 | Accepted |

In conclusion, TPS did not directly affect TEF, but TLB and TE indirectly influenced TEF. It also confirmed that TLB contributed to team performance through TE. From the above, the full-mediation and double-mediation effect were found in the research model.

This paper explored how psychological safety influences the team’s effectiveness through learning behavior and efficacy. We applied two mediators in the research design to examine causal relationships. In summary, the research model was found to have a full double-mediation effect. TPS did not have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

First, based on social cognitive theory, we have found the crucial roles of learning behavior and efficacy in connecting psychological safety and TEF. The finding of team learning’s mediation effect is consistent with previous studies (i.e., Kostopoulos and Bozionelos, 2011 ). Also, the mediating role of TE has been confirmed. To date, little research has been done on the mediating role of TE between psychological safety and TEF. As discussed earlier, psychological factors and climate could alter the level of efficacy. According to social cognitive theory, traits such as the team’s expectations and beliefs could be affected by the psychological factors (environment) and influencing behavior. When members believe that they can complete a given task, the team produces more positive results (e.g., Tasa et al., 2007 ; Porter et al., 2011 ).

Second, the results showed that learning behavior positively affects the team’s efficacy. The result was in line with van Emmerik et al. (2011) . This finding answers the request of Knapp (2016) for additional research to determine if efficacy is significantly related to learning behavior at the team level. Learning behavior is a process that leads to a shared result and is a link toward change in organizations. If the members recognize excellent communication in the team, they become more involved, and the belief in the team’s ability could be strengthened.

Third, the results did not support one of our hypotheses that psychological safety affects TEF. The research model supported full mediation. This result is consistent with the claims of Edmondson (2012 , 2018) . Psychological safety is the “engine,” not “fuel” for performance. If individuals are under an atmosphere that highly values their ideas and actions, employees can adapt themselves even to challenging tasks. A team’s psychological safety promotes team learning and consequently increases the team’s effectiveness. Also, the favorable climate promotes the team’s efficacy and contributes to the performance of the team.

Theoretical Implications

The findings of the study present important contributions to the present knowledge in the domain. First, the research contributes to psychological safety literature by unfolding its little-known relationship with TE, answering the theoretical call from Abror (2017) to examine the relationship between the two constructs. As discussed, we found a significant effect of TPS to TE, confirming the mechanism of how team performance is created through the path.

Today, there is only limited empirical evidence on the effect of psychological safety to efficacy ( Abror, 2017 ). The author criticized Edmondson (1999) for putting the two variables on the same level. Until recently, researchers have insisted that TPS and TE are both psychological factors on the same dimension. Therefore, the causal relationship between the two is rarely experimented. This paper aims to ignite debates on that theoretical discordance in the future based on the full-mediation effect identified.

Recent studies started arguing that psychological safety might affect group efficacy (e.g., Roussin et al., 2016 ; Hernandez and Guarana, 2018 ). In the field of education, researchers started reporting the relationship between psychological climate and efficacy. When there is a respectful, collaborative, and trusting school climate ( Bryk et al., 2010 ; Ronfeldt et al., 2013 ), teachers tend to report higher levels of efficacy and more likely to stay in the profession ( Allensworth et al., 2009 ; Johnson et al., 2012 ). The research hinted at the theoretical implications and discussions, moving a step forward under the workplace context.

Second, our research contributes to the current literature of TEF by developing and exploring the two different mediating paths, further broadening the boundaries of the studies in human behavior.

The study extends the prevailing framework for TEF ( Cohen and Bailey, 1997 ) by adding empirical data. In the research model, we added a less-proven relationship (i.e., TE as another mediator) to a “psychological safety–team learning–effectiveness” model, further contributing to the applicability and the expandability of the variables as valid predictors in future team studies. To our knowledge, little research has been conducted at a team level, incorporating TPS, TLB, TE, and TEF.

We approached from the aspects of social cognitive theory to explain the TEF creation mechanism that is affected by psychological factors. Prior literature also examined the relationship between psychological safety and other outcomes, integrating theoretical views from social learning theory, social identification theory, social information processing theory, or social exchange theory ( Carmeli, 2007 ; De clercq and Rius, 2007 ; Schaubroeck et al., 2011 ; Singh et al., 2013 ; Chen et al., 2014 ; Liu et al., 2014 ; Wang et al., 2018 ). Our study contributes to building concrete theoretical foundations, enriching various angles available to decipher the complicated phenomena under a team context.

The effect of TLB on TE also presents a new perspective. Previous research has demonstrated that efficacy affects learning behavior (i.e., van Emmerik et al., 2011 ). However, the studies that reported learning behavior’s effect on TE are limited. This study argues that learning behavior can be a catalyst for the efficacy of teams.

Furthermore, our research answers Frazier et al.’s (2017) call to continue research under the team context. Group-level research is insufficient compared to individual-level studies, and continued research would contribute to the robustness of related theories ( Frazier et al., 2017 ).

Third, the study extended the contexts where psychological safety research takes place. Most of the research was conducted in western countries and advanced economies ( Abror, 2017 ). Moreover, most of the literature dealt with limited work context (e.g., medical, healthcare, and nursing). This research paid attention to frontline sales and service employees in South Korea, broadening boundaries for future empirical work.

Implications for Practice

The research results may provide several implications for practice. First, the findings point to the vital role of safety climate as a performance enabler in an organization. Top management’s intense pressure can lead to extreme consequences ( Edmondson, 2018 ). Unconditional emphasis on psychological safety is also undesirable. Unrestrained psychological well-being could result in cheating and incompliance with the group’s social constraints ( Pearsall and Ellis, 2011 ). Leaders should pay close attention to establishing an equilibrium that might maximize team performance. Teams can move into a “learning zone” when accountability for performance interacts with psychological safety.

Second, the findings also suggest that energizing the team’s process should be considered for enhanced performance in teams. When a safe environment is ready, members facilitate learning from failures ( Hirak et al., 2012 ), and members’ feedback-seeking behavior and adaptability could be strengthened ( Gong and Li, 2019 ). Therefore, leaders can take a strategy that promotes a psychologically safe climate and stimulates interaction, regardless of external support at a team level. Raising the team’s efficacy would be a superior strategy, too. Regarding the limited resources and authority of team leaders, promoting the team process can be a reliable approach.

Third, the results shed light on the importance of team learning in an organizational context. There are limitations to a top-down approach and centralized training. Learning at a lower level should be stressed as a way of contributing to the firm’s sustainability. Leaders should pay attention to approaches that nurture the dynamic learning process that mediates psychological safety and efficacy, finally leading to performance.

Limitations and Future Research

In this study, we suggest several limitations as follows. First, as Wang et al. (2018) pointed out, it is still difficult for researchers to infer causal relationships when there is a possible underlying bias from research methodology. In any survey method, some form of bias may be present that leads to the overestimation or underestimation of coefficients or relations ( Bido et al., 2017 ). We collected data from multiple sources based on a single survey followed by a statistical procedure to test the CMB issue. We recommend future researchers of human behavior in business to consider the ex ante approach (i.e., the time difference in data collection) so that they can minimize the bias.

Second, longitudinal data collection would provide a stronger theoretical foundation than cross-sectional data. The mediation effect explained by cross-sectional data might not be fully adequate to reveal the hidden structural relationships ( Maxwell et al., 2011 ). Replication of this study based on longitudinal data collection would also be an option for future researchers, re-simulating the findings of the study.

Third, researchers can consider a new line of methodologies and other mediation variables. As Newman et al. (2017) suggested, a qualitative research approach would provide a more holistic and more profound understanding of how psychological safety influences the outcome. With more observational techniques, researches can provide descriptions of a vibrant and dynamic process of a TEF creation. Several factors can influence TEF as a mediator or a moderator. Including little known factors in a research model would provide precious evidence about teams in an era of rapid change.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics statement.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patients/participants or patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

SK devised the research idea, developed the research model, and performed the analytic calculations for the manuscript. HL and TC contributed to the final version of the manuscript and supervised the research. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Questionnaire and descriptive statistics.

| Author | Questionnaire | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| Members criticized when making a mistake* | 5.254 | 1.045 | 0.682 | 0.536 | |

| Can bring up work problems and awkward stories | |||||

| Members often ignore other people’s opinions* | |||||

| Able to take risks | |||||

| Cannot ask for help from other members* | |||||

| Members do not degrade my efforts | |||||

| My own skills and talents appreciated and utilized | |||||

| Actively propose new ideas for tasks | 4.932 | 1.321 | 0.500 | 0.087 | |

| Creating a new way of doing things. | |||||

| Ideas and practices often introduced to other teams | |||||

| Mutual communication | 5.535 | 1.272 | 1.072 | 0.977 | |

| Chance to express own opinions | |||||

| Exchange ideas with each other | |||||

| Documents the details of work | 4.533 | 1.409 | 0.246 | 0.415 | |

| Records good ideas | |||||

| Records or manages best practice | |||||

| Total | 5.000 | 1.205 | 0.593 | 0.236 | |

| Has above-average ability | 5.562 | 1.080 | 0.781 | 0.572 | |

| Members have the best work skills | |||||

| Some members can’t do their job properly* | |||||

| Excellent performance compared to other teams | |||||

| Can achieve more than the team’s goal | |||||

| Very efficient | |||||

| Fulfilling responsibilities given by the organization | 5.678 | 1.030 | 0.702 | 0.228 | |

| Achieving the level of task that we expect | |||||

| Meeting official performance requirements | |||||

| Doing a key role that can improve team’s evaluation |

- Abror A. (2017). The Relationship Between Psychological Safety, Self-Efficacy and Organisational Performance: A Case in Indonesian Companies. Doctoral dissertation, University of Hull, Kingston upon Hull. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allensworth E., Ponisciak S., Mazzeo C. (2009). The Schools Teachers Leave: Teacher Mobility in Chicago Public Schools. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED505882 (accessed June 2009). [ Google Scholar ]

- Argote L., Gruenfeld D., Naquin C. (1999). “ Group learning in organizations ,” in Groups at Work: Advances in Theory and Research , ed. Turner M. E. (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; ), 369–411. [ Google Scholar ]

- Argyris C. (1986). Reinforcing organizational defensive routines: an unintended human resources activity. Hum. Resour. Manage. 25 541–555. 10.1002/hrm.3930250405 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baer M., Frese M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. J. Organ. Behav. 24 45–68. 10.1002/job.179 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bagozzi R. P., Yi Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 16 74–94. 10.1007/bf02723327 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. (1986). “ Social foundations of thought and action ,” in The Health Psychology Reader , ed. Marks D. F. (London, UK: Sage Publications; ), 94–106. 10.4135/9781446221129.n6 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. (1988). Organisational applications of social cognitive theory. Austr. J. Manage. 13 275–302. 10.1177/031289628801300210 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman & Company. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 9 75–78. 10.1111/1467-8721.00064 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bido D. S., Mantovani D. M. N., Cohen E. D. (2017). Destruction of measurement scale through exploratory factor analysis in production and operations research. Gestão Produção 25 384–397. 10.1590/0104-530x3391-16 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown T. A. (2015). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research , 2nd Edn New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brueller D., Carmeli A. (2011). Linking capacities of high-quality relationships to team learning and performance in service organizations. Hum. Resour. Manage. 50 455–477. 10.1002/hrm.20435 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryk A., Sebring P., Allensworth E., Luppescu S., Easton J. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bstieler L., Hemmert M. (2010). Increasing learning and time efficiency in interorganizational new product development teams. J. Prod. Innov. Manage. 27 485–499. 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00731.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carmeli A. (2007). Social capital, psychological safety and learning behaviours from failure in organisations. Long Range Plann. 40 30–44. 10.1016/j.lrp.2006.12.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carmeli A., Brueller D., Dutton J. E. (2009). Learning behaviours in the workplace: the role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 26 81–98. 10.1002/sres.932 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carmeli A., Gittell J. H. (2009). High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 30 709–729. 10.1002/job.565 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen C., Liao J., Wen P. (2014). Why does formal mentoring matter? The mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of power distance orientation in the Chinese context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manage. 25 1112–1130. 10.1080/09585192.2013.816861 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen G., Kanfer R. (2006). Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior in work teams. Res. Organ. Behav. 27 223–267. 10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27006-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen G., Thomas B., Wallace J. C. (2005). A multilevel examination of the relationships among training outcomes, mediating regulatory processes, and adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 90 827–841. 10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.827 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Christian M. S., Garza A. S., Slaughter J. E. (2011). Work engagement: a quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 64 89–136. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark T. R. (2019). The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety. Available online at: http://adigaskell.org/2019/11/17/the-4-stages-of-psychological-safety/ (accessed November 17, 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen S. G., Bailey D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. J. Manage. 23 239–290. 10.1177/014920639702300303 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Day C., Hopkins D., Harris A., Ahtaridou E. (2009). The Impact of School Leadership on Pupil Outcomes. Available online at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/11329/1/DCSF-RR108.pdf (accessed June 2009). [ Google Scholar ]

- De clercq D., Rius I. B. (2007). Organizational commitment in Mexican small and medium-sized firms: the role of work status, organizational climate, and entrepreneurial orientation. J. Small Bus. Manage. 45 467–490. 10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00223.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donaldson S. I., Csikszentmihalyi M., Nakamura J. (2011). Applied Positive Psychology: Improving Everyday Life, Health, Schools, Work, and Society. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dulebohn J. H., Hoch J. E. (2017). Virtual teams in organizations. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 27 569–574. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.12.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dyer J. H., Nobeoka K. (2000). Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing network: the Toyota case. Strateg. Manage. J. 21 345–367. 10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(200003)21:3<345::aid-smj96<3.0.co;2-n [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmondson A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44 350–383. 10.2307/2666999 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmondson A. C. (2008). The competitive imperative of learning . Harv. Bus. Rev. 86 , 60–67. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmondson A. C. (2012). Teaming: How Organizations Learn, Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmondson A. C. (2018). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmondson A. C., Dillon J. R., Roloff K. S. (2007). Three perspectives on team learning. Acad. Manage. Ann. 1 269–314. 10.1080/078559811 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edmondson A. C., Lei Z. (2014). Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 1 23–43. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Escribano P., Dufour L., Maoret M. (2017). “ Will I socialize you? An IPO model of supervisors’ involvement in newcomers’ socialization ,” in Proceedings of the Academy of Management Annual Meeting , At Atlanta, GA: 10.5465/AMBPP.2017.251 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fabrigar L. R., Wegener D. T. (2012). Exploratory Factor Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fornell C., Larcker D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18 39–50. 10.1177/002224378101800104 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frazier M. L., Fainshmidt S., Klinger R. L., Pezeshkan A., Vracheva V. (2017). Psychological safety: a meta-analytic review and extension. Pers. Psychol. 70 113–165. 10.1111/peps.12183 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibson C., Vermeulen F. (2003). A healthy divide: subgroups as a stimulus for team learning behavior. Adm. Sci. Q. 48 202–239. 10.2307/3556657 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gibson C. B., Randel A. E., Earley P. C. (2000). Understanding group efficacy: an empirical test of multiple assessment methods. Group Organ. Manage. 25 67–97. 10.1177/1059601100251005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gladstein D. L. (1984). Groups in context: a model of task group effectiveness. Adm. Sci. Q. 29 499–517. 10.2307/2392936 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glassop L. I. (2002). The organizational benefits of teams. Hum. Relat. 55 225–249. 10.1177/0018726702055002184 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gong Z., Li T. (2019). Relationship between feedback environment established by mentor and nurses’ career adaptability: a cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manage. 27 1568–1575. 10.1111/jonm.12847 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Google (2015). Five Keys to A Successful Google Team. Available online at: https://rework.withgoogle.com/blog/five-keys-to-a-successful-google-team (accessed November 17, 2015). [ Google Scholar ]

- Guide V. D. R., Ketokivi M. (2015). Notes from the editors: redefining some methodological criteria for the journal. J. Operat. Manage. 37 5–8. 10.1016/S0272-6963(15)00056-X [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gully S. M., Incalcaterra K. A., Joshi A., Beaubien J. M. (2002). A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 87 819–832. 10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.819 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hackman J. R. (1987). “ The design of work teams ,” in Handbook of Organizational Behavior , ed. Lorsch J. (New York, NY: Prentice Hall; ), 315–342. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hair J. F., Hult G. T. M., Ringle C. M., Sarstedt M. (2017). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) , 2nd Edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harman D. (1967). A single factor test of common method variance. J. Psychol. 35 359–378. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hernandez M., Guarana C. L. (2018). An examination of the temporal intricacies of job engagement. J. Manage. 44 1711–1735. 10.1177/0149206315622573 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hirak R., Peng A. C., Carmeli A., Schaubroeck J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: the importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadersh. Q. 23 107–117. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang C.-C., Jiang P.-C. (2012). Exploring the psychological safety of R&D teams: an empirical analysis in Taiwan. J. Manage. Organ. 18 175–192. 10.1017/S1833367200000948 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ipsos (2012). Half (47%) of Global Employees Agree Their Workplace is Psychologically Safe and Healthy: Three in Ten (27%) Say Not. Available online at: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/half-47-global-employees-agree-their-workplace-psychologically-safe-and-healthy-three-ten-27-say (accessed March 14, 2012). [ Google Scholar ]

- James L. R. (1982). Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement . J. Appl. Psychol. 67 , 219–229. 10.1037/0021-9010.67.2.219 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- James L. R., Demaree R. G., Wolf G. (1993). rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 78 306–309. 10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson S. M., Kraft M. A., Papay J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: the effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teach. Coll. Rec. 114 1–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahn W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manage. J. 33 692–724. 10.5465/256287 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kessel M., Kratzer J., Schultz C. (2012). Psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and creative performance in healthcare teams. Creat. Innovat. Manage. 21 147–157. 10.1111/j.1467-8691.2012.00635.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein K. J., Dansereau F., Hall R. J. (1994). Levels issues in theory development, data collection, and analysis. Acad. Manage. Rev. 19 195–229. 10.5465/amr.1994.9410210745 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein K. J., Kozlowski S. W. (2000). From micro to meso: critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting multilevel research. Organ. Res. Methods 3 211–236. 10.1177/109442810033001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Knapp R. J. (2016). The Effects of Psychological Safety, Team Efficacy, and Transactive Memory System Development on Team Learning Behavior in Virtual Work Teams. Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kostopoulos K. C., Bozionelos N. (2011). Team exploratory and exploitative learning: psychological safety, task conflict, and team performance. Group Organ. Manage. 36 385–415. 10.1177/1059601111405985 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kozlowski S. W. J., Bell B. S. (2003). “ Work groups and teams in organizations ,” in Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 12 eds Borman W. C., Ilgen D. R., Klimoski R. J. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; ), 333–375. [ Google Scholar ]

- Li A. N., Tan H. H. (2013). What happens when you trust your supervisor? Mediators of individual performance in trust relationships. J. Organ. Behav. 34 407–425. 10.1002/job.1812 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li N., Yan J. (2009). The effects of trust climate on individual performance. Front. Bus. Res. China 3 :27–49. 10.1007/s11782-009-0002-6 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin Z., Yang H., Arya B., Huang Z., Li D. (2005). Structural versus individual perspectives on the dynamics of group performance: theoretical exploration and empirical investigation. J. Manage. 31 354–380. 10.1177/0149206304272150 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S., Hu J., Li Y., Wang Z., Lin X. (2014). Examining the cross-level relationship between shared leadership and learning in teams: evidence from China. Leadersh. Q. 25 282–295. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.08.006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu Y., Yan X., Sun Y. (2010). “ A meta-analysis of virtual team communication based on IPO model ,” in Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on E-Business Intelligence (ICEBI2010) , Kunming, 10.2991/icebi.2010.3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luszczynska A., Schwarzer R. (2005). “ Social cognitive theory ,” in Predicting Health Behaviour , eds Connor M., Norman P. (New York: NY: Open University Press; ), 127–169. [ Google Scholar ]

- Madjar N., Ortiz-Walters R. (2009). Trust in supervisors and trust in customers: their independent, relative, and joint effects on employee performance and creativity . Hum. Perform. 22 , 128–142. 10.1080/08959280902743501 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mansikka H., Harris D., Virtanen K. (2017). An input-process-output model of pilot core competencies. Aviat. Psychol. Appl. Hum. Fact. 7 78–85. 10.1027/2192-0923/a000120 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mathieu J., Maynard M. T., Rapp T., Gilson L. (2008). Team effectiveness 1997-2007: a review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future. J. Manage. 34 410–476. 10.1177/0149206308316061 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell S. E., Cole D. A., Mitchell M. A. (2011). Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behav. Res. 46 816–841. 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- May D. R., Gilson R. L., Harter L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77 11–37. 10.1348/096317904322915892 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy K. R., Davidshofer C. O. (1988). Psychological Testing: Principles, and Applications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Google Scholar ]

- Newman A., Donohue R., Eva N. (2017). Psychological safety: a systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 27 521–535. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortega A., Sánchez-Manzanares M., Gil F., Rico R. (2010). Team learning and effectiveness in virtual project teams: the role of beliefs about interpersonal context. Span. J. Psychol. 13 267–276. 10.1017/s113874160000384x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortega A., Van den Bossche P., Sánchez-Manzanares M., Rico R., Gil F. (2014). The influence of change-oriented leadership and psychological safety on team learning in healthcare teams. J. Bus. Psychol. 29 311–321. 10.1007/s10869-013-9315-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearce C. L., Herbik P. A. (2004). Citizenship behavior at the team level of analysis: the effects of team leadership, team commitment, perceived team support, and team size. J. Soc. Psychol. 144 293–310. 10.3200/SOCP.144.3.293-310 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearce C. L., Sims H. P., Jr. (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: an examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dyn. Theor. Res. Pract. 6 172–197. 10.1037/1089-2699.6.2.172 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearsall M. J., Ellis A. P. (2011). Thick as thieves: the effects of ethical orientation and psychological safety on unethical team behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 96 401–411. 10.1037/a0021503 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Porter C. O. L. H., Itir Gogus C., Yu R. C.-F. (2011). Does backing up behavior explain the efficacy–performance relationship in teams? Small Group Res. 42 458–474. 10.1177/1046496410390964 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Preacher K. J., Rucker D. D., Hayes A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav. Res. 42 185–227. 10.1080/00273170701341316 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rich B. L., Lepine J. A., Crawford E. R. (2010). Job engagement: antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manage. J. 53 617–635. 10.5465/AMJ.2010.51468988 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rico R., de la Hera C. M. A., Tabernero C. (2011). Work team effectiveness, a review of research from the last decade (1999-2009). Psychol. Spain 15 57–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Riggs M. L., Knight P. A. (1994). The impact of perceived group success-failure on motivational beliefs and attitudes: a causal model. J. Appl. Psychol. 79 755–766. 10.1037/0021-9010.79.5.755 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberto M. A. (2002). Lessons from Everest: the interaction of cognitive bias, psychological safety, and system complexity. Calif. Manage. Rev. 45 136–158. 10.2307/41166157 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ronfeldt M., Loeb S., Wyckoff J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 50 4–36. 10.3102/0002831212463813 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rousseau V., Aubé C., Savoie A. (2006). Teamwork behaviors: a review and an integration of frameworks. Small Group Res. 37 540–570. 10.1177/1046496406293125 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roussin C. J., MacLean T. L., Rudolph J. W. (2016). The safety in unsafe teams: a multilevel approach to team psychological safety. J. Manage. 42 1409–1433. 10.1177/0149206314525204 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanner B., Bunderson J. S. (2013). Psychological safety, learning, and performance: a comparison of direct and contingent effects. Acad. Manage. Proc. 2013 : 10198 10.5465/ambpp.2013.10198abstract [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schaubroeck J., Lam S. S. K., Peng A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 96 863–871. 10.1037/a0022625 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schein E. H., Bennis W. G. (1965). Personal and Organizational Change Through Group Methods: The Laboratory Approach. New York, NY: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shen M. J., Chen M. C. (2007). The relationship of leadership, team trust and team performance: a comparison of the service and manufacturing industries. Soc. Behav. Pers. 35 643–658. 10.2224/sbp.2007.35.5.643 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Singh B., Winkel D. E., Selvarajan T. T. (2013). Managing diversity at work: does psychological safety hold the key to racial differences in employee performance? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 86 242–263. 10.1111/joop.12015 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stalmeijer R. E., Gijselaers W. H., Wolfhagen I. H., Harendza S., Scherpbier A. J. (2007). How interdisciplinary teams can create multi-disciplinary education: the interplay between team processes and educational quality. Med. Educ. 41 1059–1066. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02898.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tasa K., Taggar S., Seijts G. H. (2007). The development of collective efficacy in teams: a multilevel and longitudinal perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 92 17–27. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.17 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van den Bossche P., Gijselaers W. H., Segers M., Kirschner P. A. (2006). Social and cognitive factors driving teamwork in collaborative learning environments: team learning beliefs and behaviors. Small Group Res. 37 490–521. 10.1177/1046496406292938 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van Emmerik H., Jawahar I. M., Schreurs B., De Cuyper N. (2011). Social capital, team efficacy and team potency: the mediating role of team learning behaviors. Career Dev. Int. 16 82–99. 10.1108/13620431111107829 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- van Offenbeek M. (2001). Processes and outcomes of team learning. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 10 303–317. 10.1080/13594320143000690 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Walumbwa F. O., Wang P., Lawler J. J., Shi K. (2004). The role of collective efficacy in the relations between transformational leadership and work outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 77 515–530. 10.1348/0963179042596441 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y., Liu J., Zhu Y. (2018). Humble leadership, psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and follower creativity: a cross-level investigation. Front. Psychol. 9 : 1727 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01727 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Werner J. M., Lester S. W. (2001). Applying a team effectiveness framework to the performance of student case teams. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 12 385–402. 10.1002/hrdq.1004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- West B. J., Patera J. L., Carsten M. K. (2009). Team level positivity: investigating positive psychological capacities and team level outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 30 249–267. 10.1002/job.593 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams L. J., Anderson S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manage. 17 601–617. 10.1177/014920639101700305 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wong A., Tjosvold D., Lu J. (2010). Leadership values and learning in China: the mediating role of psychological safety. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 48 86–107. 10.1177/1038411109355374 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zellmer-Bruhn M., Gibson C. (2006). Multinational organization context: implications for team learning and performance. Acad. Manage. J. 49 501–518. 10.5465/amj.2006.21794668 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zoogah D. B., Noe R. A., Shenkar O. (2015). Shared mental model, team communication and collective self-efficacy: an investigation of strategic alliance team effectiveness. Int. J. Strateg. Bus. Alliances 4 244–270. 10.1504/IJSBA.2015.075383 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior

Volume 10, 2023, review article, open access, psychological safety comes of age: observed themes in an established literature.

- Amy C. Edmondson 1 , and Derrick P. Bransby 1

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; email: [email protected] [email protected]

- Vol. 10:55-78 (Volume publication date January 2023) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

- First published as a Review in Advance on November 14, 2022

- Copyright © 2023 by the author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See credit lines of images or other third-party material in this article for license information

Since its renaissance in the 1990s, psychological safety research has flourished—a boom motivated by recognition of the challenge of navigating uncertainty and change. Today, its theoretical and practical significance is amplified by the increasingly complex and interdependent nature of the work in organizations. Conceptual and empirical research on psychological safety—a state of reduced interpersonal risk—is thus timely, relevant, and extensive. In this article, we review contemporary psychological safety research by describing its various content areas, assessing what has been learned in recent years, and suggesting directions for future research. We identify four dominant themes relating to psychological safety: getting things done, learning behaviors, improving the work experience, and leadership. Overall, psychological safety plays important roles in enabling organizations to learn and perform in dynamic environments, becoming particularly relevant in a world altered by a global pandemic.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Agarwal P , Farndale E. 2017 . High-performance work systems and creativity implementation: the role of psychological capital and psychological safety. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 27 : 3 440 – 58 [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad I , Umrani WA 2019 . The impact of ethical leadership style on job satisfaction: mediating role of perception of Green HRM and psychological safety. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 40 : 5 534 – 47 [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed F , Zhao F , Faraz NA , Qin YJ. 2021 . How inclusive leadership paves way for psychological well-being of employees during trauma and crisis: a three-wave longitudinal mediation study. J. Adv. Nurs. 77 : 2 819 – 31 [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M , Moen O , Brett PO. 2020 . The organizational climate for psychological safety: associations with SMEs’ innovation capabilities and innovation performance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 55 : 101554 [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum NP , Dow A , Mazmanian PE , Jundt DK , Appelbaum EN. 2016 . The effects of power, leadership and psychological safety on resident event reporting. Med. Educ. 50 : 3 343 – 50 [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz JE , Sudan S , Fitzpatrick L , Cotten SR , Jodoin C et al. 2019 . Organizational determinants of bullying and work disengagement among hospital nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 75 : 6 1229 – 38 [Google Scholar]