- Ebooks & Courses

- Practice Tests

How To Write an IELTS Map Essay

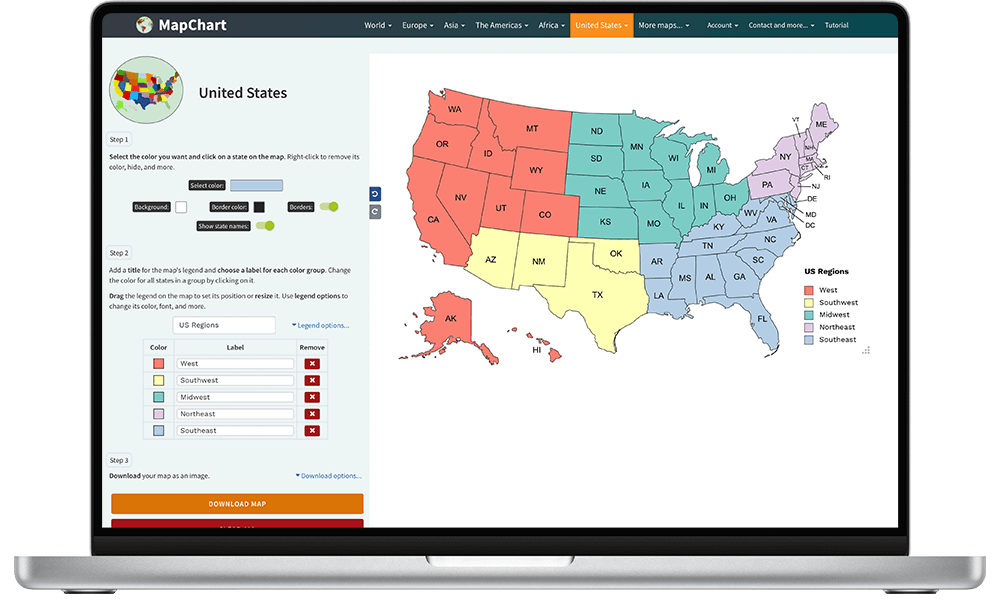

IELTS map questions are the easiest to answer. There are no numbers to analyse, just 2 or 3 maps to compare. Very occasionally, there might only be a single map, but this is rare.

The maps will be of the same location at different times. This could be in the past, the present time or a plan for a proposed development in the future. You are required to write about the changes you see between the maps.

There are 5 steps to writing a high-scoring IELTS map essay:

1) Analyse the question

2) Identify the main features

3) Write an introduction

4) Write an overview

5) Write the details paragraphs

I must emphasise the importance of steps 1 and 2. It is essential that you complete this planning stage properly before you start writing. You’ll understand why when I guide you through it. It should only take 5 minutes, leaving you a full 15 minute to write your essay.

In this lesson, we’re going to work through the 5 stages step-by-step as we answer a practice IELTS map question.

Before we begin, here’s a model essay structure that you can use as a guideline for all IELTS Academic Task 1 questions.

Ideally, your essay should have 4 paragraphs:

Paragraph 1 – Introduction

Paragraph 2 – Overview

Paragraph 3 – 1 st main feature

Paragraph 4 – 2 nd main feature

We now have everything we need to begin planning and writing our IELTS map essay.

Here’s our practice question:

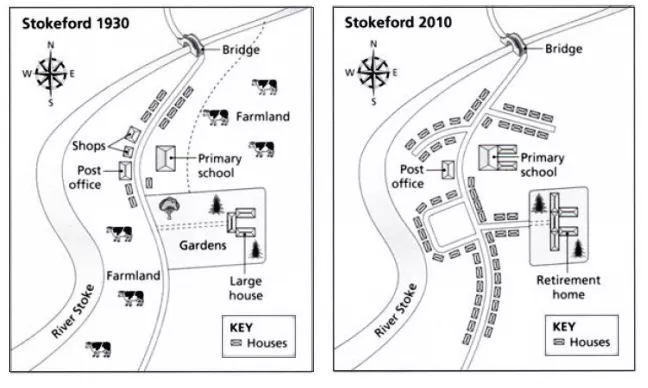

The maps below show the village of Stokeford in 1930 and 2010.

Summarise the information by selecting and reporting the main features, and make comparisons where relevant.

Write at least 150 words.

Step 1 – Analyse the question

The format of every Academic Task 1 question is the same. Here is our practice question again with the words that will be included in all questions highlighted.

Every question consists of:

- Sentence 1 – A brief description of the graphic

- Sentence 2 – The instructions

- The graphic – map, chart, graph, table, etc.

Sentence 2 tells you what you have to do.

You must do 3 things:

1. Select the main features.

2. Write about the main features.

3. Compare the main features.

All three tasks refer to the ‘ main features ’ of the graphic. You do not have to write about everything. Just pick out 2 or 3 key features and you’ll have plenty to write about.

Step 2 – Identify the Main Features

All you are looking for are the main features. Start with the earliest map. Identify the key features and look to see how they have changed in the later map, and again in the final map if there are three.

Here are some useful questions to ask?

1) What time periods are shown?

Are the maps of past, present or future situations? This is important to note because it will determine whether you write your essay using past, present or future tenses.

The two maps in our practice IELTS map question show the village of Stokeford at two different times in the past. This immediately tells us that we will need to use the past tense in our essay.

2) What are the main differences between the maps?

What features have disappeared? What new features are in their place?

3) What features have remained the same over the time period?

Although the location on the maps will have undergone major development, some features may remain unchanged.

Also, think about directional language you can use, such as:

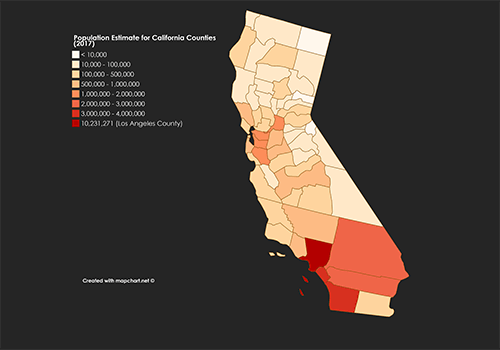

So, what information is contained our maps? Here they are again.

Source: IELTS past paper

There are a number of different features we could select such as, the loss of the shops, the disappearance of farmland, the enlargement of the school and the development of the large house into a retirement home.

Many maps will contain far more changes than our sample maps and the changes may be more complex. In such cases, you won’t have time to write about all of them and will need to select just 2 or 3 main features to focus on.

Our maps are quite simple so we’ll list all 4 of the major changes I’ve just identified.

Main feature 1: The farmland has been built on.

Main feature 2: The large house has been converted into a retirement home.

Main feature 3: The school has been enlarged.

Main feature 4: The shops have disappeared.

The key features you select will be the starting point for your IELTS map essay. You will then go on to add more detail later. However, with just 20 minutes allowed for Task 1, and a requirement of only 150 words, you won't be able to include many details.

We’re now ready to begin writing our essay. Here’s a reminder of the 4 part structure we’re going to use.

For this essay, we’ll adapt this a little to write about two of the features in Paragraph 3 and the other two features in Paragraph 4.

Step 3 – Write an Introduction

In the introduction, you should simply paraphrase the question, that is, say the same thing in a different way. You can do this by using synonyms and changing the sentence structure. For example:

Introduction (Paragraph 1):

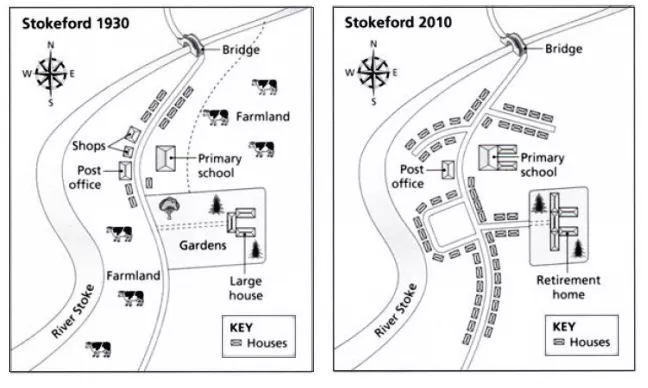

The two maps illustrate how the village of Stokeford, situated on the east bank of the River Stoke, changed over an 80 year period from 1930 to 2010.

This is all you need to do for the introduction.

Step 4 – Write an Overview (Paragraph 2)

In the second paragraph, you should describe the general changes that have taken place. The detail comes later in the essay.

State the information simply. No elaborate vocabulary or grammar structures are required, just the appropriate words and correct verb tenses.

For example:

Overview (Paragraph 2):

There was considerable development of the settlement over these years and it was gradually transformed from a small rural village into a largely residential area.

Two sentences would be better than one for the second paragraph but we’ll be getting into the detail if we say more about these maps at this point, so we’ll leave the overview as one sentence.

Step 5 – Write the 1st Detail Paragraph

Paragraphs 3 and 4 of your IELTS map essay are where you include more detailed information. In paragraph 3, you should give evidence to support your first 1or 2 key features.

In the case of our main features, 1 and 3 are closely related so we’ll write about these two together.

Here they are again:

And this is an example of what you could write:

Paragraph 3 :

The most notable change is the presence of housing in 2010 on the areas that were farmland back in 1930. New roads were constructed on this land and many residential properties built. In response to the considerable increase in population, the primary school was extended to around double the size of the previous building.

Step 6 – Write the 2nd Detail Paragraph

For the fourth and final paragraph, you do the same thing for your remaining key features.

Here are the two we have left:

This is an example of what you could write:

Paragraph 4 :

Whilst the post office remained as a village amenity, the two shops that can be seen to the north-west of the school in 1930, no longer existed by 2010, having been replaced by houses. There also used to be an extensive property standing in its own large gardens situated to the south-east of the school. At some time between 1930 and 2010, this was extended and converted into a retirement home. This was another significant transformation for the village.

Here are the four paragraphs brought together to create our finished essay.

Finished IELTS Map Essay

This sample IELTS map essay is well over the minimum word limit so you can see that you don’t have space to include very much detail at all. That’s why it is essential to select just a couple of main features to write about.

Now use what you’ve learnt in this lesson to practice answering other IELTS map questions. Start slowly at first and keep practicing until you can plan and write a complete essay in around 20 minutes.

Want to watch and listen to this lesson?

Click on this video.

Would you prefer to share this page with others by linking to it?

- Click on the HTML link code below.

- Copy and paste it, adding a note of your own, into your blog, a Web page, forums, a blog comment, your Facebook account, or anywhere that someone would find this page valuable.

Like this page?

Ielts academic writing task 1 – all lessons.

IELTS Academic Writing – A summary of the test including important facts, test format & assessment.

Academic Writing Task 1 – The format, the 7 question types & sample questions, assessment & marking criteria. All the key information you need to know.

Understanding Task 1 Questions – How to quickly and easily analyse and understand IELTS Writing Task 2 questions.

How To Plan a Task 1 Essay – Discover 3 reasons why you must plan, the 4 simple steps of essay planning and learn a simple 4 part essay structure.

Vocabulary for Task 1 Essays – Learn key vocabulary for a high-scoring essay. Word lists & a downloadable PDF.

Grammar for Task 1 Essays – Essential grammar for Task 1 Academic essays including, verb tenses, key sentence structures, articles & prepositions.

The 7 Question Types:

Click the links below for a step-by-step lesson on each type of Task 1 question.

- Table Chart

- Process Diagram

- Multiple Graphs

- IELTS Writing

- IELTS Maps Essays

- Back To Top

* New * Grammar For IELTS Ebooks

$9.99 each Full Set Just $ 23.97

Find Out More >>

IELTS Courses

Full details...

IELTS Writing Ebook

Discount Offer

$7 each Full Set Just $ 21

Find out more >>

Testimonials

“I am very excited to have found such fabulous and detailed content. I commend your good work.” Jose M.

“Thanks for the amazing videos. These are ‘to the point’, short videos, beautifully explained with practical examples." Adari J.

"Hi Jacky, I bought a listening book from you this morning. You know what? I’m 100% satisfied. It’s super helpful. If I’d had the chance to read this book 7 years ago, my job would be very different now." Loi H.

"Hi Jacky, I recently got my IELTS results and I was pleased to discover that I got an 8.5 score. I'm firmly convinced your website and your videos played a strategic role in my preparation. I was able to improve my writing skills thanks to the effective method you provide. I also only relied on your tips regarding the reading section and I was able to get a 9! Thank you very much." Giano

“After listening to your videos, I knew I had to ditch every other IELTS tutor I'd been listening to. Your explanations are clear and easy to understand. Anyways, I took the test a few weeks ago and my result came back: Speaking 7, listening 9, Reading 8.5 and Writing 7 with an average band score of 8. Thanks, IELTS Jacky." Laide Z.

Contact

About Me

Site Map

Privacy Policy

Disclaimer

IELTS changes lives.

Let's work together so it changes yours too.

Copyright © 2024 IELT Jacky

All Right Reserved

IELTS is a registered trademark of the University of Cambridge, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia. This site and its owners are not affiliated, approved or endorsed by the University of Cambridge ESOL, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia.

MAPS ESSAY EXAMPLES

IELTS Writing Task 1 Academic Maps Essay Examples

View High Band Score Examples Of IELTS Writing Task 1Academic Maps Essays.

IELTS Writing Task 1 – Maps Example Essay 4

IELTS Writing Task 1 Academic map essay example that is a band score 8. The question is: The map below shows the changes in an American town between 1948 and 2010. Take a look at the sample answer.

IELTS Writing Task 1 – Maps Example Essay 3

IELTS Writing Task 1 Academic map essay example that is a band score 8. The question is: The map below is of the town of Garlsdon. A new supermarket (S) is planned for the town. The map shows two possible sites for the supermarket. Take a look at the sample answer.

IELTS Writing Task 1 – Maps Example Essay 2

IELTS Writing Task 1 Academic map essay example that is a band score 8. The question is: The diagram shows the proposed changes to Foster road. Write a 150-word report describing the proposed changes for a local committee. Take a look at the sample answer.

IELTS Writing Task 1 – Maps Example Essay 1

IELTS Writing Task 1 Academic map essay example that is a band score 8. The question is: The two maps below show an island, before and after the construction of some tourist facilities. Take a look at the sample answer.

Essay on Earth

500 words essay on earth.

The earth is the planet that we live on and it is the fifth-largest planet. It is positioned in third place from the Sun. This essay on earth will help you learn all about it in detail. Our earth is the only planet that can sustain humans and other living species. The vital substances such as air, water, and land make it possible.

All About Essay on Earth

The rocks make up the earth that has been around for billions of years. Similarly, water also makes up the earth. In fact, water covers 70% of the surface. It includes the oceans that you see, the rivers, the sea and more.

Thus, the remaining 30% is covered with land. The earth moves around the sun in an orbit and takes around 364 days plus 6 hours to complete one round around it. Thus, we refer to it as a year.

Just like revolution, the earth also rotates on its axis within 24 hours that we refer to as a solar day. When rotation is happening, some of the places on the planet face the sun while the others hide from it.

As a result, we get day and night. There are three layers on the earth which we know as the core, mantle and crust. The core is the centre of the earth that is usually very hot. Further, we have the crust that is the outer layer. Finally, between the core and crust, we have the mantle i.e. the middle part.

The layer that we live on is the outer one with the rocks. Earth is home to not just humans but millions of other plants and species. The water and air on the earth make it possible for life to sustain. As the earth is the only livable planet, we must protect it at all costs.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

There is No Planet B

The human impact on the planet earth is very dangerous. Through this essay on earth, we wish to make people aware of protecting the earth. There is no balance with nature as human activities are hampering the earth.

Needless to say, we are responsible for the climate crisis that is happening right now. Climate change is getting worse and we need to start getting serious about it. It has a direct impact on our food, air, education, water, and more.

The rising temperature and natural disasters are clear warning signs. Therefore, we need to come together to save the earth and leave a better planet for our future generations.

Being ignorant is not an option anymore. We must spread awareness about the crisis and take preventive measures to protect the earth. We must all plant more trees and avoid using non-biodegradable products.

Further, it is vital to choose sustainable options and use reusable alternatives. We must save the earth to save our future. There is no Planet B and we must start acting like it accordingly.

Conclusion of Essay on Earth

All in all, we must work together to plant more trees and avoid using plastic. It is also important to limit the use of non-renewable resources to give our future generations a better planet.

FAQ on Essay on Earth

Question 1: What is the earth for kids?

Answer 1: Earth is the third farthest planet from the sun. It is bright and bluish in appearance when we see it from outer space. Water covers 70% of the earth while land covers 30%. Moreover, the earth is the only planet that can sustain life.

Question 2: How can we protect the earth?

Answer 2: We can protect the earth by limiting the use of non-renewable resources. Further, we must not waste water and avoid using plastic.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

The Waldseemüller Map: Charting the New World

Two obscure 16th-century German scholars named the American continent and changed the way people thought about the world

Toby Lester

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Waldseemuller-Map-631.jpg)

It was a curious little book. When a few copies began resurfacing, in the 18th century, nobody knew what to make of it. One hundred and three pages long and written in Latin, it announced itself on its title page as follows:

INTRODUCTION TO COSMOGRAPHY WITH CERTAIN PRINCIPLES OF GEOMETRY AND ASTRONOMY NECESSARY FOR THIS MATTER

ADDITIONALLY, THE FOUR VOYAGES OF AMERIGO VESPUCCI

A DESCRIPTION OF THE WHOLE WORLD ON BOTH A GLOBE AND A FLAT SURFACE WITH THE INSERTION OF THOSE LANDS UNKNOWN TO PTOLEMY DISCOVERED BY RECENT MEN

The book—known today as the Cosmographiae Introductio , or Introduction to Cosmography —listed no author. But a printer's mark recorded that it had been published in 1507, in St. Dié, a town in eastern France some 60 miles southwest of Strasbourg, in the Vosges Mountains of Lorraine.

The word "cosmography" isn't used much today, but educated readers in 1507 knew what it meant: the study of the known world and its place in the cosmos. The author of the Introduction to Cosmography laid out the organization of the cosmos as it had been described for more than 1,000 years: the Earth sat motionless at the center, surrounded by a set of giant revolving concentric spheres. The Moon, the Sun and the planets each had their own sphere, and beyond them was the firmament, a single sphere studded with all of the stars. Each of these spheres wheeled grandly around the Earth at its own pace, in a never-ending celestial procession.

All of this was delivered in the dry manner of a textbook. But near the end, in a chapter devoted to the makeup of the Earth, the author elbowed his way onto the page and made an oddly personal announcement. It came just after he had introduced readers to Asia, Africa and Europe—the three parts of the world known to Europeans since antiquity. "These parts," he wrote, "have in fact now been more widely explored, and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci (as will be heard in what follows). Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I do not see why anyone should rightly prevent this [new part] from being called Amerigen—the land of Amerigo, as it were—or America, after its discoverer, Americus, a man of perceptive character."

How strange. With no fanfare, near the end of a minor Latin treatise on cosmography, a nameless 16th-century author briefly stepped out of obscurity to give America its name—and then disappeared again.

Those who began studying the book soon noticed something else mysterious. In an easy-to-miss paragraph printed on the back of a foldout diagram, the author wrote, "The purpose of this little book is to write a sort of introduction to the whole world that we have depicted on a globe and on a flat surface. The globe, certainly, I have limited in size. But the map is larger."

Various remarks made in passing throughout the book implied that this map was extraordinary. It had been printed on several sheets, the author noted, suggesting that it was unusually large. It had been based on several sources: a brand-new letter by Amerigo Vespucci (included in the Introduction to Cosmography ); the work of the second-century Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy; and charts of the regions of the western Atlantic newly explored by Vespucci, Columbus and others. Most significant, it depicted the New World in a dramatically new way. "It is found," the author wrote, "to be surrounded on all sides by the ocean."

This was an astonishing statement. Histories of New World discovery have long told us that it was only in 1513—after Vasco Núñez de Balboa had first caught sight of the Pacific by looking west from a mountain peak in Panama—that Europeans began to conceive of the New World as something other than a part of Asia. And it was only after 1520, once Magellan had rounded the tip of South America and sailed into the Pacific, that Europeans were thought to have confirmed the continental nature of the New World. And yet here, in a book published in 1507, were references to a large world map that showed a new, fourth part of the world and called it America.

The references were tantalizing, but for those studying the Introduction to Cosmography in the 19th century, there was an obvious problem. The book contained no such map.

Scholars and collectors alike began to search for it, and by the 1890s, as the 400th anniversary of Columbus' first voyage approached, the search had become a quest for the cartographical Holy Grail. "No lost maps have ever been sought for so diligently as these," Britain's Geographical Journal declared at the turn of the century, referring both to the large map and the globe. But nothing turned up. In 1896, the historian of discovery John Boyd Thacher simply threw up his hands. "The mystery of the map," he wrote, "is a mystery still."

On March 4, 1493, seeking refuge from heavy seas, a storm-battered caravel flying the Spanish flag limped into Portugal's Tagus River estuary. In command was one Christoforo Colombo, a Genoese sailor destined to become better known by his Latinized name, Christopher Columbus. After finding a suitable anchorage site, Columbus dispatched a letter to his sponsors, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, reporting in exultation that after a 33-day crossing he had reached the Indies, a vast archipelago on the eastern outskirts of Asia.

The Spanish sovereigns greeted the news with excitement and pride, though neither they nor anybody else initially assumed that Columbus had done anything revolutionary. European sailors had been discovering new islands in the Atlantic for more than a century—the Canaries, the Madeiras, the Azores, the Cape Verde islands. People had good reason, based on the dazzling variety of islands that dotted the oceans of medieval maps, to assume that many more remained to be found.

Some people assumed that Columbus had found nothing more than a few new Canary Islands. Even if Columbus had reached the Indies, that didn't mean he had expanded Europe's geographical horizons. By sailing west to what appeared to be the Indies (but in actuality were the islands of the Caribbean), he had confirmed an ancient theory that nothing but a small ocean separated Europe from Asia. Columbus had closed a geographical circle, it seemed—making the world smaller, not larger.

But the world began to expand again in the early 1500s. The news first reached most Europeans in letters by Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine merchant who had taken part in at least two voyages across the Atlantic, one sponsored by Spain, the other by Portugal, and had sailed along a giant continental landmass that appeared on no maps of the time. What was sensational, even mind-blowing, about this newly discovered land was that it stretched thousands of miles beyond the Equator to the south . Printers in Florence jumped at the chance to publicize the news, and in late 1502 or early 1503 they printed a doctored version of one of Vespucci's letters, under the title Mundus Novus , or New World , in which he appeared to say that he'd discovered a new continent. The work quickly became a best seller.

"In the past," it began, "I have written to you in rather ample detail about my return from those new regions...and which can be called a new world, since our ancestors had no knowledge of them, and they are entirely new matter to those who hear about them. Indeed, it surpasses the opinion of our ancient authorities, since most of them assert that there is no continent south of the equator....[But] I have discovered a continent in those southern regions that is inhabited by more numerous peoples and animals than in our Europe, or Asia or Africa."

This passage has been described as a watershed moment in European geographical thought—the moment at which a European first became aware that the New World was distinct from Asia. But "new world" didn't necessarily mean then what it means today. Europeans used it regularly to describe any part of the known world that they had not previously visited or seen described. In fact, in another letter, unambiguously attributed to Vespucci, he made clear where he thought he had been on his voyages. "We concluded," he wrote, "that this was continental land—which I esteem to be bounded by the eastern part of Asia."

In 1504 or so, a copy of the New World letter fell into the hands of an Alsatian scholar and poet named Matthias Ringmann. Then in his early 20s, Ringmann taught school and worked as a proofreader at a small printing press in Strasbourg, but he had a side interest in classical geography—specifically, the work of Ptolemy. In a work known as the Geography , Ptolemy had explained how to map the world in degrees of latitude and longitude, a system he had used to stitch together a comprehensive picture of the world as it was known in antiquity. His maps depicted most of Europe, the northern half of Africa and the western half of Asia, but they didn't, of course, include all the parts of Asia visited by Marco Polo in the 13th century, or the parts of southern Africa discovered by the Portuguese in the latter half of the 15th century.

When Ringmann came across the New World letter, he was immersed in a careful study of Ptolemy's Geography , and he recognized that Vespucci, unlike Columbus, appeared to have sailed south right off the edge of the world that Ptolemy had mapped. Thrilled, Ringmann printed his own version of the New World letter in 1505—and to emphasize the southness of Vespucci's discovery, he changed the work's title from New World to On the Southern Shore Recently Discovered by the King of Portugal , referring to Vespucci's sponsor, King Manuel.

Not long afterward, Ringmann teamed up with a German cartographer named Martin Waldseemüller to prepare a new edition of Ptolemy's Geography . Sponsored by René II, the Duke of Lorraine, Ringmann and Waldseemüller set up shop in the little French town of St. Dié, in the mountains just southwest of Strasbourg. Working as part of a small group of humanists and printers known as the Gymnasium Vosagense, the pair developed an ambitious plan. Their edition would include not only 27 definitive maps of the ancient world, as Ptolemy had described it, but also 20 maps showing the discoveries of modern Europeans, all drawn according to the principles laid out in the Geography —a historical first.

Duke René seems to have been instrumental in inspiring this leap. From unknown contacts he had received yet another Vespucci letter, also falsified, describing his voyages and at least one nautical chart depicting the new coastlines explored to date by the Portuguese. The letter and the chart confirmed to Ringmann and Waldseemüller that Vespucci had indeed discovered a huge unknown land across the ocean to the west, in the Southern Hemisphere.

What happened next is unclear. At some time in 1505 or 1506, Ringmann and Waldseemüller decided that the land Vespucci had explored was not a part of Asia. Instead, they concluded that it must be a new, fourth part of the world.

Temporarily setting aside their work on their Ptolemy atlas, Ringmann and Waldseemüller threw themselves into the production of a grand new map that would introduce Europe to this new idea of a four-part world. The map would span 12 separate sheets, printed from carefully carved wood blocks; when pasted together, the sheets would measure a stunning 4 1/2 by 8 feet—creating one of the largest printed maps, if not the largest, ever produced to that time. In April of 1507, they began printing the map, and would later report turning out 1,000 copies.

Much of what the map showed would have come as no surprise to Europeans familiar with geography. Its depiction of Europe and North Africa derived directly from Ptolemy; sub- Saharan Africa derived from recent Portuguese nautical charts; and Asia derived from the works of Ptolemy and Marco Polo. But on the left side of the map was something altogether new. Rising out of the formerly uncharted waters of the Atlantic, stretching almost from the map's top to its bottom, was a strange new landmass, long and thin and mostly blank—and there, written across what is known today as Brazil, was a strange new name: America.

Libraries today list Martin Waldseemüller as the author of the Introduction to Cosmography , but the book does not actually single him out as such. It includes opening dedications by both him and Ringmann, but these refer to the map, not the text—and Ringmann's dedication comes first. In fact, Ringmann's fingerprints are all over the work. The book's author, for instance, demonstrates a familiarity with ancient Greek—a language that Ringmann knew well but Waldseemüller did not. The author embellishes his writing with snatches of verse by Virgil, Ovid and other classical writers—a literary tic that characterizes all of Ringmann's writing. And the one contemporary writer mentioned in the book was a friend of Ringmann's.

Ringmann the writer, Waldseemüller the mapmaker: the two men would team up in precisely this way in 1511, when Waldseemüller printed a grand map of Europe. Accompanying the map was a booklet titled Description of Europe , and in dedicating his map to Duke Antoine of Lorraine, Waldseemüller made clear who had written the book. "I humbly beg of you to accept with benevolence my work," he wrote, "with an explanatory summary prepared by Ringmann." He might just as well have been referring to the Introduction to Cosmography .

Why dwell on this arcane question of authorship? Because whoever wrote the Introduction to Cosmography was almost certainly the person who coined the name "America"—and here, too, the balance tilts in Ringmann's favor. The famous naming-of-America paragraph sounds a lot like Ringmann. He's known, for example, to have spent time mulling over the use of feminine names for concepts and places. "Why are all the virtues, the intellectual qualities and the sciences always symbolized as if they belonged to the feminine sex?" he would write in a 1511 essay. "Where does this custom spring from: a usage common not only to the pagan writers but also to the scholars of the church? It originated from the belief that knowledge is destined to be fertile of good works....Even the three parts of the old world received the name of women."

Ringmann reveals his hand in other ways. In both poetry and prose he regularly amused himself by making up words, by punning in different languages and by investing his writing with hidden meanings. The naming-of-America passage is rich in just this sort of wordplay, much of which requires a familiarity with Greek. The key to the whole passage, almost always overlooked, is the curious name Amerigen (which Ringmann quickly Latinizes and then feminizes to come up with America). To get Amerigen, Ringmann combined the name Amerigo with the Greek word gen, the accusative form of a word meaning "earth," and by doing so coined a name that means—as he himself explains—"land of Amerigo."

But the word yields other meanings. Gen can also mean "born" in Greek, and the word ameros can mean "new," making it possible to read Amerigen as not only "land of Amerigo" but also "born new"—a double-entendre that would have delighted Ringmann, and one that very nicely complements the idea of fertility that he associated with female names. The name may also contain a play on meros , a Greek word sometimes translated as "place." Here Amerigen becomes A-meri-gen, or "No-place-land"—not a bad way to describe a previously unnamed continent whose geography is still uncertain.

Copies of the Waldseemüller map began to appear at German universities in the decade after 1507; sketches of it and copies made by students and professors in Cologne, Tübingen, Leipzig and Vienna survive. The map clearly was getting around, as was the Introduction to Cosmography itself. The little book was reprinted several times and attracted acclaim across Europe, largely because of the long Vespucci letter.

What about Vespucci himself? Did he ever come across the map or the Introduction to Cosmography ? Did he ever learn that the New World had been named in his honor? The odds are that he did not. Neither the book nor the name is known to have made it to the Iberian Peninsula before he died, in Seville, in 1512. But both surfaced there soon afterward: the name America first appeared in Spain in a book printed in 1520, and Christopher Columbus' son Ferdinand, who lived in Spain, acquired a copy of the Introduction to Cosmography sometime before 1539. The Spanish didn't like the name, however. Believing that Vespucci had somehow named the New World after himself, usurping Columbus' rightful glory, they refused to put the name America on official maps and documents for two more centuries. But their cause was lost from the start. The name America, such a natural poetic counterpart to Asia, Africa and Europa, had filled a vacuum, and there was no going back, especially not after the young Gerardus Mercator, destined to become the century's most influential cartographer, decided that the whole of the New World, not just its southern part, should be so labeled. The two names he put on his 1538 world map are the ones we've used ever since: North America and South America.

Ringmann didn't have long to live after finishing the Introduction to Cosmography . By 1509 he was suffering from chest pains and exhaustion, probably from tuberculosis, and by the fall of 1511, not yet 30, he was dead. After Ringmann's death Waldseemüller continued to make maps, including at least three that depicted the New World, but never again did he depict it as surrounded by water, or call it America—more evidence that these ideas were Ringmann's. On one of his later maps, the Carta Marina of 1516—which identifies South America only as "Terra Nova"—Waldseemüller even issued a cryptic apology that seems to refer to his great 1507 map: "We will seem to you, reader, previously to have diligently presented and shown a representation of the world that was filled with error, wonder, and confusion.... As we have lately come to understand, our previous representation pleased very few people. Therefore, since true seekers of knowledge rarely color their words in confusing rhetoric, and do not embellish facts with charm but instead with a venerable abundance of simplicity, we must say that we cover our heads with a humble hood."

Waldseemüller produced no other maps after the Carta Marina, and some four years later, on March 16, 1520, in his mid-40s, he died—"dead without a will," a clerk would later write when recording the sale of his house in St. Dié.

During the decades that followed, copies of the 1507 map wore out or were discarded in favor of more up-to-date and better-printed maps, and by 1570 the map had all but vanished. One copy did survive, however. Sometime between 1515 and 1517, the Nuremberg mathematician and geographer Johannes Schöner acquired a copy and bound it into a beechwood-covered folio that he kept in his reference library. Between 1515 and 1520, Schöner studied the map carefully, but by the time he died, in 1545, he probably had not opened it in years. The map had begun its long sleep, which would last more than 350 years.

It was found again by accident, as happens so often with lost treasures. In the summer of 1901, freed from his teaching duties at Stella Matutina, a Jesuit boarding school in Feldkirch, Austria, Father Joseph Fischer set out for Germany. Balding, bespectacled and 44 years old, Fischer was a professor of history and geography. For seven years he had been haunting the public and private libraries of Europe in his spare time, hoping to find maps that showed evidence of the early Atlantic voyages of the Norsemen. This current trip was no exception. Earlier in the year, Fischer had received word that the impressive collection of maps and books at Wolfegg Castle, in southern Germany, included a rare 15th-century map that depicted Greenland in an unusual way. He had to travel only some 50 miles to reach Wolfegg, a tiny town in the rolling countryside just north of Austria and Switzerland, not far from Lake Constance. He reached the town on July 15, and upon his arrival at the castle, he would later recall, he was offered "a most friendly welcome and all the assistance that could be desired."

The map of Greenland turned out to be everything Fischer had hoped. As was his custom on research trips, after studying the map Fischer began a systematic search of the castle's entire collection. For two days he made his way through the inventory of maps and prints and spent hours immersed in the castle's rare books. And then, on July 17, his third day there, he walked over to the castle's south tower, where he had been told he would find a small second-floor garret containing what little he hadn't yet seen of the castle's collection.

The garret is a simple room. It's designed for storage, not show. Bookshelves line three of its walls from floor to ceiling, and two windows let in a cheery amount of sunlight. Wandering about the room and peering at the spines of the books on the shelves, Fischer soon came across a large folio with beechwood covers, bound together with finely tooled pigskin. Two Gothic brass clasps held the folio shut, and Fischer gently pried them open. On the inside cover he found a small bookplate, bearing the date 1515 and the name of the folio's original owner: Johannes Schöner. "Posterity," the inscription began, "Schöner gives this to you as an offering."

Fischer started leafing through the folio. To his amazement, he discovered that it contained not only a rare 1515 star chart engraved by the German artist Albrecht Dürer, but also two giant world maps. Fischer had never seen anything quite like them. In pristine condition, printed from intricately carved wood blocks, each one was made up of separate sheets that, if removed from the folio and assembled, would create maps approximately 4 1/2 by 8 feet in size.

Fischer began examining the first map in the folio. Its title, running in block letters across the bottom of the map, read, THE WHOLE WORLD ACCORDING TO THE TRADITION OF PTOLEMY AND THE VOYAGES OF AMERIGO VESPUCCI AND OTHERS. This language brought to mind the Introduction to Cosmography , a work Fischer knew well, as did the portraits of Ptolemy and Vespucci that he saw at the top of the map.

Could this be... the map? Fischer began to study it sheet by sheet. Its two center sheets, which showed Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East and western Asia, came straight from Ptolemy. Farther to the east, it presented the Far East as described by Marco Polo. Southern Africa reflected the nautical charts of the Portuguese.

It was an unusual mix of styles and sources: precisely the sort of synthesis, Fischer realized, that the Introduction to Cosmography had promised. But he began to get truly excited when he turned to the map's three western sheets. There, rising out of the sea and stretching from the top to bottom, was the New World, surrounded by water.

A legend at the bottom of the page corresponded verbatim to a paragraph in the Introduction to Cosmography . North America appeared on the top sheet, a runt version of its modern self. Just to the south lay a number of Caribbean islands, among them two big ones identified as Spagnolla and Isabella. A small legend read, "These islands were discovered by Columbus, an admiral of Genoa, at the command of the King of Spain." Moreover, the vast southern landmass stretching from above the Equator to the bottom of the map was labeled DISTANT UNKNOWN LAND. Another legend read THIS WHOLE REGION WAS DISCOVERED BY THE ORDER OF THE KING OF CASTILE. But what must have brought Fischer's heart to his mouth was what he saw on the bottom sheet: AMERICA.

The 1507 map! It had to be. Alone in the little garret in the tower of Wolfegg Castle, Father Fischer realized that he had discovered the most sought-after map of all time.

Fischer took the news of his discovery straight to his mentor, the renowned Innsbruck geographer Franz Ritter von Wieser. In the fall of 1901, after intense study, the two went public. The reception was ecstatic. "Geographical students in all parts of the world have awaited with the deepest interest details of this most important discovery," the Geographical Journal declared, breaking the news in a February 1902 essay, "but no one was probably prepared for the gigantic cartographical monster which Prof. Fischer has now awakened from so many centuries of peaceful slumber." On March 2 the New York Times followed suit: "There has lately been made in Europe one of the most remarkable discoveries in the history of cartography," its report read.

Interest in the map grew. In 1907, the London-based bookseller Henry Newton Stevens Jr., a leading dealer in Americana, secured the rights to put the 1507 map up for sale during its 400th-anniversary year. Stevens offered it as a package with the other large Waldseemüller map—the Carta Marina of 1516, which had also been bound into Schöner's folio—for $300,000, or about $7 million in today's currency. But he found no takers. The 400th anniversary passed, two world wars and the cold war engulfed Europe, and the Waldseemüller map, left alone in its tower garret, went to sleep for another century.

Today, at last, the map is awake again—this time, it would appear, for good. In 2003, after years of negotiation with the owners of Wolfegg Castle and the German government, the Library of Congress acquired it for $10 million. On April 30, 2007, almost exactly 500 years after its making, German Chancellor Angela Merkel officially transferred the map to the United States. That December, the Library of Congress put it on permanent display in its grand Jefferson Building, where it is the centerpiece of an exhibit titled "Exploring the Early Americas."

As you move through it, you pass a variety of priceless cultural artifacts made in the pre-Columbian Americas, and a choice selection of original texts and maps dating from the period of first contact between the New World and the Old. Finally you arrive at an inner sanctum, and there, reunited with the Introduction to Cosmography , the Carta Marina and a few other select geographical treasures, is the Waldseemüller map. The room is quiet, the lighting dim. To study the map you have to move close and peer carefully through the glass—and when you do, it begins to tell its stories.

Adapted from The Fourth Part of the World , by Toby Lester. © 2009 Toby Lester. Published by the Free Press. Reproduced with permission.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

About this Interactive

Related resources.

Expository writing is an increasingly important skill for elementary, middle, and high school students to master. This interactive graphic organizer helps students develop an outline that includes an introductory statement, main ideas they want to discuss or describe, supporting details, and a conclusion that summarizes the main ideas. The tool offers multiple ways to navigate information including a graphic in the upper right-hand corner that allows students to move around the map without having to work in a linear fashion. The finished map can be saved, e-mailed, or printed.

- Student Interactives

- Strategy Guides

- Lesson Plans

- Calendar Activities

The Persuasion Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to map out their arguments for a persuasive essay or debate.

This Strategy Guide describes the processes involved in composing and producing audio files that are published online as podcasts.

This strategy guide explains the writing process and offers practical methods for applying it in your classroom to help students become proficient writers.

This strategy guide clarifies the difference between persuasion and argumentation, stressing the connection between close reading of text to gather evidence and formation of a strong argumentative claim about text.

Students will identify how Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream of nonviolent conflict-resolution is reinterpreted in modern texts. Homework is differentiated to prompt discussion on how nonviolence is portrayed through characterization and conflict. Students will be formally assessed on a thesis essay that addresses the Six Kingian Principles of Nonviolence.

Students develop their reading, writing, research, and technology skills using graphic novels. As a final activity, students create their own graphic novels using comic software.

Students are encouraged to understand a book that the teacher reads aloud to create a new ending for it using the writing process.

While drafting a literary analysis essay (or another type of argument) of their own, students work in pairs to investigate advice for writing conclusions and to analyze conclusions of sample essays. They then draft two conclusions for their essay, select one, and reflect on what they have learned through the process.

Students analyze rhetorical strategies in online editorials, building knowledge of strategies and awareness of local and national issues. This lesson teaches students connections between subject, writer, and audience and how rhetorical strategies are used in everyday writing.

It's not easy surviving fourth grade (or third or fifth)! In this lesson, students brainstorm survival tips for future fourth graders and incorporate those tips into an essay.

Students explore the nature and structure of expository texts that focus on cause and effect and apply what they learned using graphic organizers and writing paragraphs to outline cause-and-effect relationships.

Students prepare an already published scholarly article for presentation, with an emphasis on identification of the author's thesis and argument structure.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Examples >

- Essay Topics

Essays on World Map

5 samples on this topic

On this resource, we've put together a directory of free paper samples regarding World Map. The plan is to provide you with a sample similar to your World Map essay topic so that you could have a closer look at it in order to grasp a clear idea of what a brilliant academic work should look like. You are also recommended to use the best World Map writing practices displayed by expert authors and, eventually, develop a top-notch paper of your own.

However, if writing World Map papers entirely by yourself is not an option at this point, WowEssays.com essay writer service might still be able to help you out. For example, our authors can pen a unique World Map essay sample exclusively for you. This example paper on World Map will be written from scratch and tailored to your individual requirements, fairly priced, and sent to you within the pre-set deadline. Choose your writer and buy custom essay now!

Research Paper On Poland History

History of Poland

Poland or officially, the Republic of Poland, is located in central Europe. It shares borders with Germany, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Belarus and Ukraine. It has a population of 38.4 million people and the country is divided into 16 administrative units. The World War II was a grim event for Poland as millions of Polish people perished in this war.

Political makeup

Free Rationale for Lesson Plans Essay

Example of research study about johannesburg research paper.

Introduction

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Home » World Maps » World Map

World Map - Political - Click a Country

Buy a united states wall map.

Political Map of the World

Buy a world wall map.

Use Google Earth Free

CIA Political Map of the World

World Country Outline Maps

Satellite image maps of u.s. states.

CIA Time Zone Map of the World

World Map of Cities at Night

Maps of the World's Oceans

Types of Maps

Countries of the World

World Physical Map

Buy a Physical World Wall Map

Physical Map of the World

Countries of the World:

Essay on Our World

Students are often asked to write an essay on Our World in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Our World

What is our world.

Our world is the place where we live. It is a big ball floating in space. It has land, water, air, and many kinds of plants and animals. People live all over the world in different countries.

The Land and Seas

The world has seven big pieces of land called continents. Between these lands are oceans. The land has mountains, valleys, and flat areas. The seas are deep and full of fish and other sea creatures.

Weather and Climate

Our world has different kinds of weather. Some places are hot, some are cold. Rain, snow, and sunshine happen because of the weather. Climate is what the weather is like over a long time.

People and Cultures

Many people live on Earth. They speak different languages and have different traditions. This is called culture. People eat different foods, wear different clothes, and celebrate different festivals.

Animals and Plants

Our world has many animals and plants. Some live in forests, some in deserts, and some in the water. They all need each other to live and grow. This is called nature.

250 Words Essay on Our World

Our beautiful planet.

Our world is a wonderful place. It is full of different lands, waters, and skies. The Earth is the third planet from the sun and the only place we know that has life. It has seven big land parts called continents and five large water parts called oceans.

The Variety of Life

Many types of living things call Earth their home. From tiny bugs to huge whales, life is everywhere. Trees and plants grow in many places and help make the air we breathe. Animals live on land, in water, and in the air. People live all over the world in cities, towns, and villages.

The Changing Seasons

Our world has seasons because our planet tilts as it goes around the sun. Some places have four seasons: spring, summer, fall, and winter. Each season has its own kind of weather and changes in nature. In spring, flowers bloom. Summer brings warmth and sunshine. Fall makes leaves change color. Winter covers many places with snow.

Our Shared Home

Earth is a shared home for all of us. We must take care of it. This means not littering, recycling, and saving water. Everyone can help, even kids. By taking care of our world, we make sure it stays beautiful and safe for all living things, including us, for a very long time.

500 Words Essay on Our World

Our world is a wonderful place filled with all sorts of amazing things. It’s like a giant home that we all share with people, animals, plants, and many other living things. The world has different parts, like the land where we walk and build houses, the sky where birds fly and clouds float, and the oceans that have fish and other sea creatures.

The land is split into parts called continents, and each one has its own special features. For example, Africa has vast deserts and amazing wildlife, while Europe is known for its rich history and beautiful cities. No matter where you are on land, there’s always something new and exciting to see.

The Blue Oceans

Our planet is mostly covered by water, which is why it looks blue from space. The oceans are home to thousands of creatures, from tiny fish to huge whales. The water in the oceans also helps to keep our world’s climate just right, so it’s not too hot or too cold. We also use the oceans to travel from one place to another and to find food.

The Sky Above Us

When we look up, we see the sky. During the day, it’s bright because of the sun, which gives us light and warmth. At night, the sky changes and becomes dark, but it’s still beautiful with the moon and stars. The sky also gives us weather, which can be sunny, rainy, or snowy.

Living Things

Our world is full of life. People live in different places, speak various languages, and have their own ways of doing things. Animals can be found everywhere, from the hot savannas of Africa to the cold Arctic. Plants grow all over too, giving us food to eat and air to breathe.

Taking Care of Our World

It’s important to take care of our world because it’s the only one we have. We need to make sure that we don’t harm the environment. This means not polluting the air and water, and not cutting down too many trees. We should also try to use less energy by doing simple things like turning off lights when we’re not using them.

Learning and Exploring

There’s so much to learn about our world. By reading books, going to school, and talking to different people, we can learn about other cultures and places. Exploring can be as simple as visiting a park near your home or as big as traveling to another country.

Our world is an amazing place that’s full of wonders. From the deep blue oceans to the vast continents, and the sky above, there’s always something new to discover. It’s important to remember that we need to take care of our planet so it stays beautiful and healthy. By learning and exploring, we can all help to make sure our world is a great place for everyone.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Our Universe

- Essay on Our Planet Our Health

- Essay on Our Nation

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks

Published on February 9, 2015 by Shane Bryson . Revised on July 23, 2023 by Shona McCombes.

This example guides you through the structure of an essay. It shows how to build an effective introduction , focused paragraphs , clear transitions between ideas, and a strong conclusion .

Each paragraph addresses a single central point, introduced by a topic sentence , and each point is directly related to the thesis statement .

As you read, hover over the highlighted parts to learn what they do and why they work.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay, an appeal to the senses: the development of the braille system in nineteenth-century france.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

In France, debates about how to deal with disability led to the adoption of different strategies over time. While people with temporary difficulties were able to access public welfare, the most common response to people with long-term disabilities, such as hearing or vision loss, was to group them together in institutions (Tombs, 1996). At first, a joint institute for the blind and deaf was created, and although the partnership was motivated more by financial considerations than by the well-being of the residents, the institute aimed to help people develop skills valuable to society (Weygand, 2009). Eventually blind institutions were separated from deaf institutions, and the focus shifted towards education of the blind, as was the case for the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, which Louis Braille attended (Jimenez et al, 2009). The growing acknowledgement of the uniqueness of different disabilities led to more targeted education strategies, fostering an environment in which the benefits of a specifically blind education could be more widely recognized.

Several different systems of tactile reading can be seen as forerunners to the method Louis Braille developed, but these systems were all developed based on the sighted system. The Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris taught the students to read embossed roman letters, a method created by the school’s founder, Valentin Hauy (Jimenez et al., 2009). Reading this way proved to be a rather arduous task, as the letters were difficult to distinguish by touch. The embossed letter method was based on the reading system of sighted people, with minimal adaptation for those with vision loss. As a result, this method did not gain significant success among blind students.

Louis Braille was bound to be influenced by his school’s founder, but the most influential pre-Braille tactile reading system was Charles Barbier’s night writing. A soldier in Napoleon’s army, Barbier developed a system in 1819 that used 12 dots with a five line musical staff (Kersten, 1997). His intention was to develop a system that would allow the military to communicate at night without the need for light (Herron, 2009). The code developed by Barbier was phonetic (Jimenez et al., 2009); in other words, the code was designed for sighted people and was based on the sounds of words, not on an actual alphabet. Barbier discovered that variants of raised dots within a square were the easiest method of reading by touch (Jimenez et al., 2009). This system proved effective for the transmission of short messages between military personnel, but the symbols were too large for the fingertip, greatly reducing the speed at which a message could be read (Herron, 2009). For this reason, it was unsuitable for daily use and was not widely adopted in the blind community.

Nevertheless, Barbier’s military dot system was more efficient than Hauy’s embossed letters, and it provided the framework within which Louis Braille developed his method. Barbier’s system, with its dashes and dots, could form over 4000 combinations (Jimenez et al., 2009). Compared to the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, this was an absurdly high number. Braille kept the raised dot form, but developed a more manageable system that would reflect the sighted alphabet. He replaced Barbier’s dashes and dots with just six dots in a rectangular configuration (Jimenez et al., 2009). The result was that the blind population in France had a tactile reading system using dots (like Barbier’s) that was based on the structure of the sighted alphabet (like Hauy’s); crucially, this system was the first developed specifically for the purposes of the blind.

While the Braille system gained immediate popularity with the blind students at the Institute in Paris, it had to gain acceptance among the sighted before its adoption throughout France. This support was necessary because sighted teachers and leaders had ultimate control over the propagation of Braille resources. Many of the teachers at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth resisted learning Braille’s system because they found the tactile method of reading difficult to learn (Bullock & Galst, 2009). This resistance was symptomatic of the prevalent attitude that the blind population had to adapt to the sighted world rather than develop their own tools and methods. Over time, however, with the increasing impetus to make social contribution possible for all, teachers began to appreciate the usefulness of Braille’s system (Bullock & Galst, 2009), realizing that access to reading could help improve the productivity and integration of people with vision loss. It took approximately 30 years, but the French government eventually approved the Braille system, and it was established throughout the country (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

Although Blind people remained marginalized throughout the nineteenth century, the Braille system granted them growing opportunities for social participation. Most obviously, Braille allowed people with vision loss to read the same alphabet used by sighted people (Bullock & Galst, 2009), allowing them to participate in certain cultural experiences previously unavailable to them. Written works, such as books and poetry, had previously been inaccessible to the blind population without the aid of a reader, limiting their autonomy. As books began to be distributed in Braille, this barrier was reduced, enabling people with vision loss to access information autonomously. The closing of the gap between the abilities of blind and the sighted contributed to a gradual shift in blind people’s status, lessening the cultural perception of the blind as essentially different and facilitating greater social integration.

The Braille system also had important cultural effects beyond the sphere of written culture. Its invention later led to the development of a music notation system for the blind, although Louis Braille did not develop this system himself (Jimenez, et al., 2009). This development helped remove a cultural obstacle that had been introduced by the popularization of written musical notation in the early 1500s. While music had previously been an arena in which the blind could participate on equal footing, the transition from memory-based performance to notation-based performance meant that blind musicians were no longer able to compete with sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997). As a result, a tactile musical notation system became necessary for professional equality between blind and sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997).

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Bullock, J. D., & Galst, J. M. (2009). The Story of Louis Braille. Archives of Ophthalmology , 127(11), 1532. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.286.

Herron, M. (2009, May 6). Blind visionary. Retrieved from https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2009/05/blind-visionary/.

Jiménez, J., Olea, J., Torres, J., Alonso, I., Harder, D., & Fischer, K. (2009). Biography of Louis Braille and Invention of the Braille Alphabet. Survey of Ophthalmology , 54(1), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.006.

Kersten, F.G. (1997). The history and development of Braille music methodology. The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education , 18(2). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40214926.

Mellor, C.M. (2006). Louis Braille: A touch of genius . Boston: National Braille Press.

Tombs, R. (1996). France: 1814-1914 . London: Pearson Education Ltd.

Weygand, Z. (2009). The blind in French society from the Middle Ages to the century of Louis Braille . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bryson, S. (2023, July 23). Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/example-essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Why Taiwan Was So Prepared for a Powerful Earthquake

Decades of learning from disasters, tightening building codes and increasing public awareness may have helped its people better weather strong quakes.

Search-and-rescue teams recover a body from a leaning building in Hualien, Taiwan. Thanks to improvements in building codes after past earthquakes, many structures withstood Wednesday’s quake. Credit...

Supported by

- Share full article

By Chris Buckley , Meaghan Tobin and Siyi Zhao

Photographs by Lam Yik Fei

Chris Buckley reported from the city of Hualien, Meaghan Tobin from Taipei, in Taiwan.

- April 4, 2024

When the largest earthquake in Taiwan in half a century struck off its east coast, the buildings in the closest city, Hualien, swayed and rocked. As more than 300 aftershocks rocked the island over the next 24 hours to Thursday morning, the buildings shook again and again.

But for the most part, they stood.

Even the two buildings that suffered the most damage remained largely intact, allowing residents to climb to safety out the windows of upper stories. One of them, the rounded, red brick Uranus Building, which leaned precariously after its first floors collapsed, was mostly drawing curious onlookers.

The building is a reminder of how much Taiwan has prepared for disasters like the magnitude-7.4 earthquake that jolted the island on Wednesday. Perhaps because of improvements in building codes, greater public awareness and highly trained search-and-rescue operations — and, likely, a dose of good luck — the casualty figures were relatively low. By Thursday, 10 people had died and more than 1,000 others were injured. Several dozen were missing.

“Similar level earthquakes in other societies have killed far more people,” said Daniel Aldrich , a director of the Global Resilience Institute at Northeastern University. Of Taiwan, he added: “And most of these deaths, it seems, have come from rock slides and boulders, rather than building collapses.”

Across the island, rail traffic had resumed by Thursday, including trains to Hualien. Workers who had been stuck in a rock quarry were lifted out by helicopter. Roads were slowly being repaired. Hundreds of people were stranded at a hotel near a national park because of a blocked road, but they were visited by rescuers and medics.

On Thursday in Hualien city, the area around the Uranus Building was sealed off, while construction workers tried to prevent the leaning structure from toppling completely. First they placed three-legged concrete blocks that resembled giant Lego pieces in front of the building, and then they piled dirt and rocks on top of those blocks with excavators.

“We came to see for ourselves how serious it was, why it has tilted,” said Chang Mei-chu, 66, a retiree who rode a scooter with her husband Lai Yung-chi, 72, to the building on Thursday. Mr. Lai said he was a retired builder who used to install power and water pipes in buildings, and so he knew about building standards. The couple’s apartment, near Hualien’s train station, had not been badly damaged, he said.

“I wasn’t worried about our building, because I know they paid attention to earthquake resistance when building it. I watched them pour the cement to make sure,” Mr. Lai said. “There have been improvements. After each earthquake, they raise the standards some more.”

It was possible to walk for city blocks without seeing clear signs of the powerful earthquake. Many buildings remained intact, some of them old and weather-worn; others modern, multistory concrete-and-glass structures. Shops were open, selling coffee, ice cream and betel nuts. Next to the Uranus Building, a popular night market with food stalls offering fried seafood, dumplings and sweets was up and running by Thursday evening.

Earthquakes are unavoidable in Taiwan, which sits on multiple active faults. Decades of work learning from other disasters, implementing strict building codes and increasing public awareness have gone into helping its people weather frequent strong quakes.

Not far from the Uranus Building, for example, officials had inspected a building with cracked pillars and concluded that it was dangerous to stay in. Residents were given 15 minutes to dash inside and retrieve as many belongings as they could. Some ran out with computers, while others threw bags of clothes out of windows onto the street, which was also still littered with broken glass and cement fragments from the quake.

One of its residents, Chen Ching-ming, a preacher at a church next door, said he thought the building might be torn down. He was able to salvage a TV and some bedding, which now sat on the sidewalk, and was preparing to go back in for more. “I’ll lose a lot of valuable things — a fridge, a microwave, a washing machine,” he said. “All gone.”

Requirements for earthquake resistance have been built into Taiwan’s building codes since 1974. In the decades since, the writers of Taiwan’s building code also applied lessons learned from other major earthquakes around the world, including in Mexico and Los Angeles, to strengthen Taiwan’s code.

After more than 2,400 people were killed and at least 10,000 others injured during the Chi-Chi quake of 1999, thousands of buildings built before the quake were reviewed and reinforced. After another strong quake in 2018 in Hualien, the government ordered a new round of building inspections. Since then, multiple updates to the building code have been released.

“We have retrofitted more than 10,000 school buildings in the last 20 years,” said Chung-Che Chou, the director general of the National Center for Research on Earthquake Engineering in Taipei.

The government had also helped reinforce private apartment buildings over the past six years by adding new steel braces and increasing column and beam sizes, Dr. Chou said. Not far from the buildings that partially collapsed in Hualien, some of the older buildings that had been retrofitted in this way survived Wednesday’s quake, he said.

The result of all this is that even Taiwan’s tallest skyscrapers can withstand regular seismic jolts. The capital city’s most iconic building, Taipei 101, once the tallest building in the world, was engineered to stand through typhoon winds and frequent quakes. Still, some experts say that more needs to be done to either strengthen or demolish structures that don’t meet standards, and such calls have grown louder in the wake of the latest earthquake.

Taiwan has another major reason to protect its infrastructure: It is home to the majority of production for the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world’s largest maker of advanced computer chips. The supply chain for electronics from smartphones to cars to fighter jets rests on the output of TSMC’s factories, which make these chips in facilities that cost billions of dollars to build.

The 1999 quake also prompted TSMC to take extra steps to insulate its factories from earthquake damage. The company made major structural adjustments and adopted new technologies like early warning systems. When another large quake struck the southern city of Kaohsiung in February 2016, TSMC’s two nearby factories survived without structural damage.

Taiwan has made strides in its response to disasters, experts say. In the first 24 hours after the quake, rescuers freed hundreds of people who were trapped in cars in between rockfalls on the highway and stranded on mountain ledges in rock quarries.

“After years of hard work on capacity building, the overall performance of the island has improved significantly,” said Bruce Wong, an emergency management consultant in Hong Kong. Taiwan’s rescue teams have come to specialize in complex efforts, he said, and it has also been able to tap the skills of trained volunteers.

Taiwan’s resilience also stems from a strong civil society that is involved in public preparedness for disasters.