Why we need religion

Stephen asma, an agnostic, argues powerfully that religion is natural and beneficial. is it such a leap to believe that it is grounded in truth.

It is a truth, though sadly not one universally acknowledged, that what you think of religion largely depends on what you think is religion. If you believe religion to be primarily a means of explaining the origins and processes of the world and of nature, you’ll measure it with a scientific yardstick and find it wanting. If you think it is a metaphysical enterprise, making propositional but untestable statements about human identity and destiny, you’ll assess it on more philosophical principles, and find it momentous or meaningless depending on whether you like your ideas falsifiable. If you think it’s a series of ethical guidelines for how to navigate the world, with little truth content in themselves, you’ll measure it on a moral scale, and find it inspiring or dispiriting, depending on which bits you’re looking at. And so on and so forth. Stephen Asma is Professor of Philosophy at Columbia College in Chicago and, once upon time, a happy inhabitant of the first of these camps. Most of his early publications were “strenuously” critical of religion. He wrote enthusiastically for various sceptical and secularist publications, and even found himself listed in “Who’s who in hell,” a publication of which I was heretofore blissfully unaware. However, some challenging encounters, wider reading and deeper reflection began to change his mind. “I’m an agnostic and a citizen of a wealthy nation,” he confesses towards the end of his provocatively-entitled 2018 Why We Need Religion , “but when my own son was in the emergency room with an illness, I prayed spontaneously.” “I’m not naïve,” he goes on to say. “I don’t think it did a damn thing to heal him. But it is a response that will not go and that should not go away if it provides genuine relief for anxiety and anguish.” We have been here before. Such a non-conversion to “religion” is the cue for a toe-curlingly patronising exercise in religious non-defence. Religion may be irrational and infantile, you know, but it’s good for the children, especially the adult ones. This, however, is not the direction in which Asma heads. To be clear, he still sees religion as irrational, although his extended discussion of creationism rather suggests he’s going for the low-hanging fruit here. Rather, he now views religion—his focus is primarily on Christianity and Buddhism, but much of what he says applies more widely—as natural, beneficial, humanising, and, indeed, indispensable. The key is the body. Why We Need Religion takes our embodied and affective nature very seriously and shows, in detail and with impressive supporting evidence, that religious commitment—beliefs, practices, rituals, etc.—help protect and manage our emotional life with unparalleled and probably irreplaceable success. Religion is, in effect, a management system for our emotional lives that helps the human organism stay healthy and well. Take grief as an example. Human grief has both elaborate cognitive and neurochemical dimensions (not, of course, disconnected things). We ruminate on moments past, futures lost, hopes dashed, memories decaying. At the same time, human—like all mammalian—grief is a form of separation distress. Mammalian brains are hardwired for the calming comfort of a caregiver’s touch, and when that is denied us, especially permanently, the brain experiences a “major reduction in opioids, oxytocin and prolactin.” Religious belief attenuates the severity of that separation, and religious practices develop, codify, and authenticate grieving customs that serve to offer a kind of emotional surrogate for loss. Both cognitively and affectively, religion helps us cope with grief. That, of course, is one of the reasons why non-religious religions like Secular Humanism so often get into the funeral business. Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Asma looks at grief, forgiveness, resilience, sacrifice, joy, fear and other deep emotions besides. Time and again, he shows how religion contains “cultural structures that enshrine and celebrate some important adaptive psychological” states, drawing on evidence that would have upset his younger, more muscular secular self. Empirical studies, he writes half way through, confirm our long held assumption that “religious people try more than others to overcome their grudges.” Similarly, the evidence that education increases forgiveness and reduces violence “is somewhat thin.” The second of these is eminently believable but even I have problems believing the former. If true, there are certainly some pretty powerful counter-examples. The book differs from the “but isn’t religion helpful” genre, then, for reasons of its scientific rigour, but also on account of the author’s sensitivity and empathy. Not only does it take some courage to begin a book by confessing a change of heart (if not mind) as Asma does, but it takes more, for example, to emphasise with the religiously violent. “People who dismiss religious-fuelled rage as intrinsically evil or primitive,” he writes, “have usually never faced real enemies.” Asma is not, of course, legitimising such rage or violence; simply seeking to understand it. In prosperous western liberal democracies, like our own, it is easy to think of one’s enemy as “a misunderstood force, whom one can eventually negotiate with.” That being so, religious rage is intolerable and an obvious moral failing. “Would that such [western] circumstances were long-lived and ubiquitous,” he remarks. “But they are neither.” This is powerful, striking at the heart of what makes people like you, me and those likely to read his book feel so morally superior. All that being so, it seems to me to be a natural step to move (or at least to edge) from religion’s affective importance to its cognitive reliability; i.e. from the kind of goodness (or at least usefulness) of which Asma writes, to its truth. Now, to be clear, this move need not be made. Just because something is (or can be) good, that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily true. However, we should, at least, pause here. You can make a very strong argument that religion has played a positive role in human evolution, enabling individual and group survival, strength and cohesion, thereby being selected for in the evolutionary process. True, evolution selects for survival, not truth… but the two are hardly independent. Broadly speaking, an organism whose cognitive functions are capable of tracking “that which is the case” is likely to do better than one that doesn’t. Whether you are finding prey, sensing a predator, or responding otherwise to your environment, it helps if your evolved senses are trained on the truth. It strikes me that the same point can be made of the apparently ubiquitous human need for religion (or in some places now, religion-like substitutes). As Steven Pinker (of all people!) once remarked “we have colour vision because there are differences in wavelength in the world. We have depth perception because the world actually does exist in three dimensions. By the same logic someone might be tempted to say that if we have a ‘God module’ there must be a God it’s an adaptation to.” Pinker of course is not tempted to say that. Nor, it seems, is Asma. I am. Nick Spencer is Senior Fellow at Theos "Why We Need Religion" by Stephen Asma is published by Oxford University Press

Why Do We Have Religion Anyway?

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Self-Control

- Self-Regulation

- Spirituality

The vast majority of the world’s 7 billion people practice some kind of religion, ranging from massive worldwide churches to obscure spiritual traditions and local sects. Nobody really knows how many religions there are on the planet, but whatever the number, there are at least that many theories about why we have religion at all. One idea is that, as humans evolved from small hunter-gatherer tribes into large agrarian cultures, our ancestors needed to encourage cooperation and tolerance among relative strangers. Religion then—along with the belief in a moralizing God—was a cultural adaptation to these challenges.

But that’s just one idea. There are many others—or make up your own. But they are all just theories. None has been empirically tested. A team of psychological scientists at Queen’s University, Ontario, is now offering a novel idea about the origin of religion, and what’s more they’re delivering some preliminary scientific evidence to support their reasoning. Researcher Kevin Rounding and his colleagues are arguing that the primary purpose of religious belief is to enhance the basic cognitive process of self-control, which in turn promotes any number of valuable social behaviors.

They tested this theory in four fairly simple experiments, using classic measures of self-control. In the first study, for example, they used a word game to prime some volunteers’ (but not others’) subconscious thoughts of religion. Then they asked all the volunteers (using a ruse) to drink an unsavory mix of OJ and vinegar, one ounce at a time. They were told they could stop any time, and to take as much time as they liked, and that they would be paid a small amount for each ounce of the brew that they drank.

The amount they drank was a proxy for self-discipline. The more OJ and vinegar they forced down, they greater their self-control. And as predicted, those with religion on their mind endured longer at the unpleasant task. Since society and religion ask us to tolerate many things we don’t particularly like for the common good, the scientists interpret this finding as evidence of a particular kind of self-control.

Another way to think of self-control, perhaps the most familiar, is delayed gratification—resisting immediate temptation to wait for a greater reward later on. In another experiment, the scientists again primed some of the volunteers with hidden religious words, but in this case they were told (falsely) that the experiment was concluded and that they would be paid. They were told, further, that they could either return the next day and be paid $5, or come back in a week and get $6. This is a widely used laboratory paradigm for measuring the exertion of discipline in the face of temptation, and indeed, almost twice as many of those with religion opted for more money later.

Self-control is costly, consuming a lot of mental resources. Recent research has demonstrated that our cognitive power—in the form of glucose, the brain’s fuel—is limited. The mind and brain can become fatigued, just like a muscle, and when depleted, normal self-control is impaired. The third experiment built on an understanding of this process, often called “ego depletion.” The scientists wanted to see if cognitively depleted people are “refueled” with reminders of religion, so they had only half of the volunteers perform a mentally draining task while listening to loud music. Then they primed half of these depleted volunteers, and half the controls, with religious words. So at this point, there were four groups: Depleted; depleted but religiously primed; undepleted controls; and religiously primed controls. All of these volunteers then attempted a set of geometrical puzzles, which, unknown to them, were impossible to solve. The impossible task was included to test their persistence against great difficulty—another measure of self-control.

The results were unambiguous. Among those who were mentally depleted, the ones with religion on their minds persisted longer at the impossible task—suggesting that the religious priming restored their cognitive powers—and their patience in the process. They performed basically the same as those who were never tired out in the first place. The scientists take this as strong evidence for the replenishing effect of religion on self-discipline.

The fourth and final experiment was the only one with ambiguous results. The first three studies had shown direct causal evidence of religion on self-control—and downstream effects on enduring discomfort, delaying rewards, and exerting patience. But is it possible that the religious priming might have activated something else—moral intuition, or death-related concerns? In order to rule out these possibilities, the scientists used a completely secular self-control task, one with no moral overlay: the so-called Stroop task. This is the task where one must rapidly identify the ink that words are printed in, rather than read the words. It’s very difficult, requiring mental exertion and self-control.

The scientists primed some with religious words as usual, but others were primed with moral words—virtue, righteous—and still others with words related to mortality—deadly, grave, and so forth. Then all the volunteers attempted the Stroop task on a computer, which measured accuracy and reaction time. The results, as reported in a forthcoming issue of the journal Psychological Science , showed that religiously primed volunteers had much more self-control than did controls or those primed to think about mortality. But those with religion on their minds were statistically no different than those with morality on their minds. This was an unexpected finding, and it suggests that activating an implicit moral sensibility may have some of the same effects as religion.

It’s not entirely clear what cognitive mechanism is at work in religion’s influence on self-control. One possibility is that religion makes people mindful of an ever watchful God, and thus encourages more self-monitoring. Or religious priming may activate concerns of supernatural punishment. A more secular explanation is that religious priming makes people more concerned about their reputation in the community, leading to more careful self-monitoring. Notably, almost a third of the volunteers in these studies were self-defined atheists or agnostics, suggesting that these robust effects have little or nothing to do with the suggestibility of the most devout.

Wray Herbert’s book, On Second Thought, was recently published in paperback. Excerpts from his two blogs—“We’re Only Human” and “Full Frontal Psychology”—appear regularly in Scientific American and in The Huffington Post.

I think that religion was created by people and for people. When you look at the similarities between religions, they all have a core idea of something being there after death, and in Christianity especially, there is a punishment for doing the wrong thing and a reward for doing the right thing. In other words, it’s manipulation. We’ve seen throughout history how religion has been used to control massive populations through this manipulation. It’s also used as a source of comfort, i.e. thinking that someone is in a better place after death. But I also believe that religion is for people who are unable to think for themselves. Religions tell you how to think, what to think, when to think, and what to think about. If you legitimately believe that all people must rely on a 2,000-year-old book to be a good person and lead a good life, then I honestly don’t know what to tell you.

I completely agree.

Nothing in this world was invented by man without a need. Religion should have been invented to meet a need. To understand the need we need to port ourselves 2000 years hence leaving behind our prejudices and beliefs. In that world, you will find small colonies of humans who had ‘leaders’, kings may be.

Every king made his own laws. And it was not uncommon to find a new king ruling every now and then. Law kept changing with every king. Life should have been pretty difficult.

For example, one king might say all food is common for the village. And you just can pick up anything you want and eat it. The next guy might say if you keep food in your house it is yours. And if you pick food from others house, you will be beheaded. A kid moving from one king to the other might end up getting beheaded!

So people thought of common rules and laws. That’s why all religions espouse laws of life. How to live? What rules to follow? Etc.,

It also explains why most religions call themselves way of life. You will also find Mohammed the Prophet was a ‘judge’ as his prime job. Jesus was called a traitor, obviously, he created a new law which was against Roman laws. And you used ways to tell others what religion you follow. So that they know which law you follow. For instance, people wore cross. Or a head gear, a mark in the forehead, long hair and such.

It also explains why polity and religion went together in the early days.

And God was used to add sanctity to it!

Essentially it was in place of constitutions/ laws of the land. Now that laws are driven by nations, the need for religions slowly started vanishing. They took over the place held by philosophy thus far and laid claim to God analysis. But that is social history.

Religious beliefs or some particular religion was created by people(messenger) who wish to give people better life, at that time religion played important role for bettermint but actually now a days we need same role according to new generation but not in the name of religion. We have to learn that all human being at same importance, all need love and care. Cast, religion, colour, race, country , all these things is destroying human. Instead think tanks should make better rules and regulations to follow for bettermint same as business rules, traffic rules.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Caring for Loved Ones the Top Priority for People Worldwide

Evolutionary psychologists have focused much of their research on the human pursuit of love and sex, but a global study shows that people’s strongest motivations lie elsewhere.

Evolutionary psychologists have focused much their research on the human pursuit of love and sex, but a global study shows that people’s strongest motivations lie elsewhere.

Adapting Into the Future

Humans’ unique cognitive abilities emerged from a cycle of interactions between brain, culture, and environment, says Atsushi Iriki.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- U.S. Public Becoming Less Religious

- Chapter 1: Importance of Religion and Religious Beliefs

Table of Contents

- Chapter 2: Religious Practices and Experiences

- Chapter 3: Views of Religious Institutions

- Chapter 4: Social and Political Attitudes

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Putting Findings From the Religious Landscape Study Into Context

While religion remains important in the lives of most Americans, the 2014 Religious Landscape Study finds that Americans as a whole have become somewhat less religious in recent years by certain traditional measures of religious commitment. For instance, fewer U.S. adults now say religion is very important in their lives than did so seven years ago, when Pew Research Center conducted a similarly extensive religion survey. Fewer adults also express absolutely certain belief in God, say they believe in heaven or say their religion’s sacred text is the word of God.

The change in Americans’ religious beliefs coincides with the rising share of the U.S. public that is not affiliated with any religion. The unaffiliated not only make up a growing portion of the population, they also are growing increasingly secular, at least on some key measures of religious belief. For instance, fewer religious “nones” say religion is very important to them than was the case in 2007, and fewer say they believe in God or believe in heaven or hell.

Among people who do identify with a religion, however, there has been little, if any, change on many measures of religious belief. People who are affiliated with a religious tradition are as likely now as in the recent past to say religion is very important in their lives and to believe in heaven. They also are as likely to believe in God, although the share of religiously affiliated adults who believe in God with absolute certainty has declined somewhat.

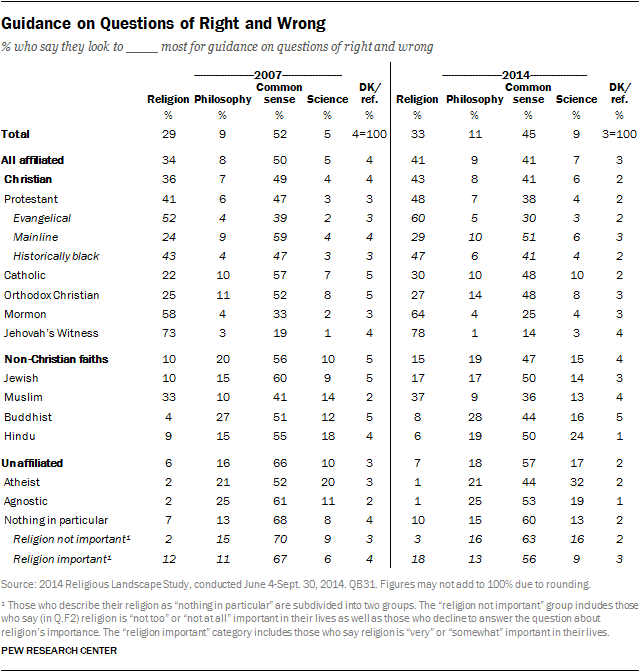

When seeking guidance on questions of right and wrong, a plurality of Americans say they rely primarily on their common sense and personal experiences. But there has been a noticeable increase in the share of religiously affiliated adults who say they turn to their religious teachings for guidance.

This chapter takes a detailed look at the religious beliefs of U.S. adults – including members of a variety of religious groups – and compares the results of the current study with the 2007 Religious Landscape Study. The chapter also examines Americans’ views on religion and salvation, religion and modernity, and religion and morality.

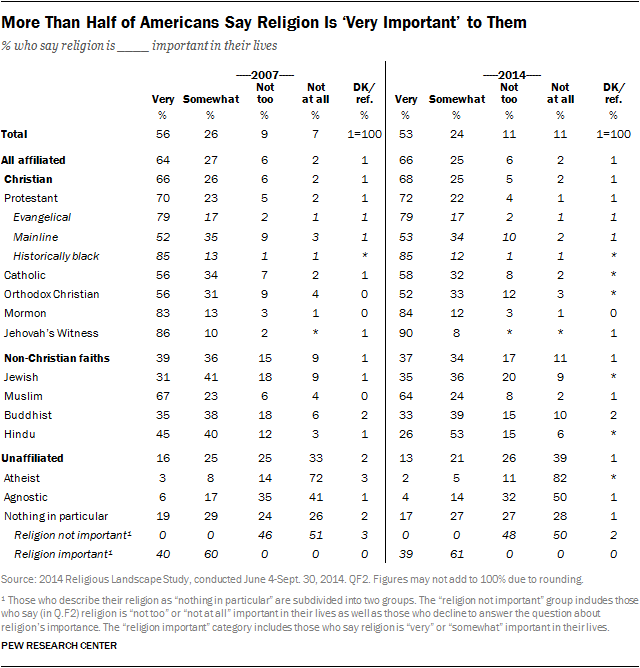

Importance of Religion

Three-quarters of U.S. adults say religion is at least “somewhat” important in their lives, with more than half (53%) saying it is “very” important. Approximately one-in-five say religion is “not too” (11%) or “not at all” important in their lives (11%).

Although religion remains important to many Americans, its importance has slipped modestly in the last seven years. In 2007, Americans were more likely to say religion was very important (56%) or somewhat important (26%) to them than they are today. Only 16% of respondents in 2007 said religion was not too or not at all important to them.

The decline in the share of Americans who say religion is very important in their lives is closely tied to the growth of the religiously unaffiliated, whose share of the population has risen from 16% to 23% over the past seven years. Compared with those who are religiously affiliated, religious “nones” are far less likely to describe religion as a key part of their lives; just 13% say religion is very important to them. Furthermore, the share of the “nones” who say religion is not an important part of their lives has grown considerably in recent years. Today, two-thirds of the unaffiliated (65%) say religion is not too or not at all important to them, up from 57% in 2007.

For Americans who are religiously affiliated, the importance people attach to religion varies somewhat by religious tradition. Roughly eight-in-ten or more Jehovah’s Witnesses (90%), members of historically black Protestant churches (85%), Mormons (84%) and evangelical Protestants (79%) say religion is very important in their lives. These figures have stayed about the same in recent years.

Smaller majorities of most other religious groups say religion plays a very important role in their lives. This includes 64% of Muslims, 58% of Catholics and 53% of mainline Protestants. Roughly half of Orthodox Christians (52%) also say this. Fewer Jews, Buddhists and Hindus say religion is very important to them, but most members of those groups indicate that religion is at least somewhat important in their lives.

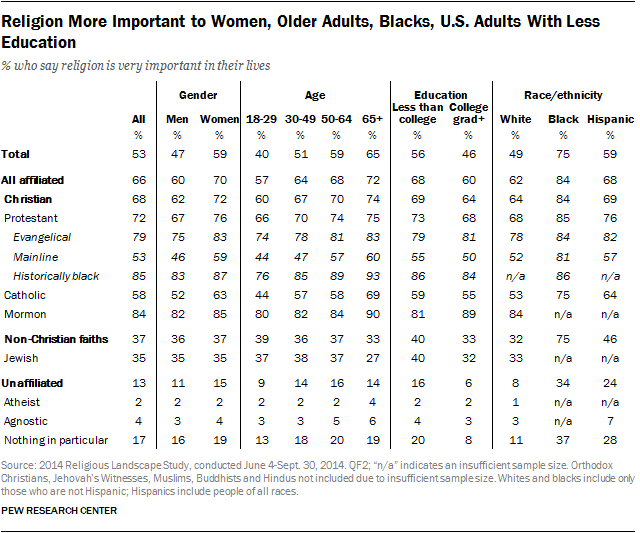

The survey also finds that older adults are more likely than younger adults to say religion is very important in their lives, and women are more likely than men to express this view. Additionally, those with a college degree typically are less likely than those with lower levels of education to say religion is very important in their lives. And blacks are much more likely than whites or Hispanics to say religion is very important in their lives. These patterns are seen in the population as a whole and within many – though not all – religious groups.

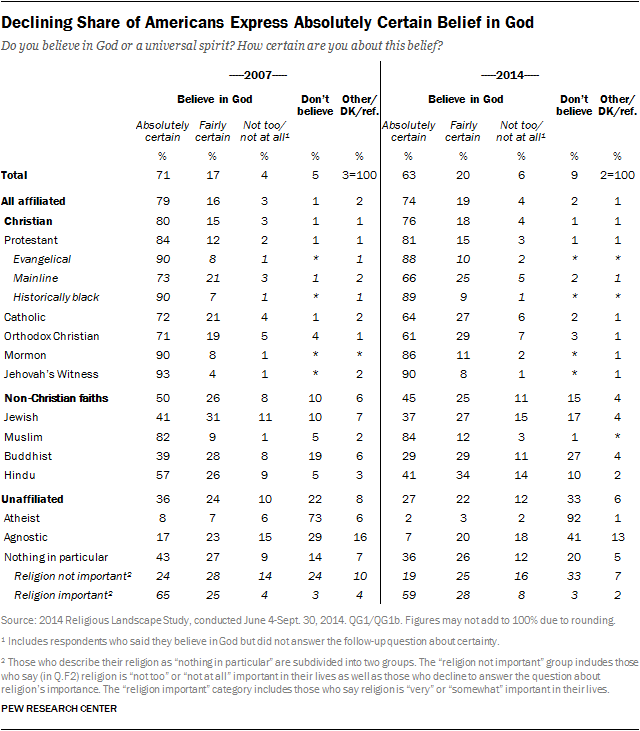

Belief in God

Nearly nine-in-ten Americans (89%) say they believe in “God or a universal spirit,” and most of them (63% of all adults) are absolutely certain in this belief. There has been a modest decline in the share of Americans who believe in God since the Religious Landscape Study was first conducted in 2007 (from 92% to 89%), and a bigger drop in the share of Americans who say they believe in God with absolute certainty (from 71% to 63%).

Majorities of adherents of most Christian traditions say they believe in God with absolute certainty. But this conviction has declined noticeably in recent years among several Christian groups. The largest drops have been among mainline Protestants (down from 73% in 2007 to 66% today), Catholics (from 72% to 64%) and Orthodox Christians (from 71% to 61%).

Among non-Christians, the pattern is mixed. Most Muslims (84%) are absolutely certain that God exists, but far fewer Hindus (41%), Jews (37%) or Buddhists (29%) are certain there is a God or universal spirit.

As was the case in 2007, most religiously unaffiliated people continue to express some level of belief in God or a universal spirit. However, the share of religious “nones” who believe in God has dropped substantially in recent years (from 70% in 2007 to 61% today). And religious “nones” who believe in God are far less certain about this belief compared with those who identify with a religion. In fact, most religiously unaffiliated believers say they are less than absolutely certain about God’s existence.

Nearly one-in-ten U.S. adults overall (9%) now say they do not believe in God, up from 5% in 2007.

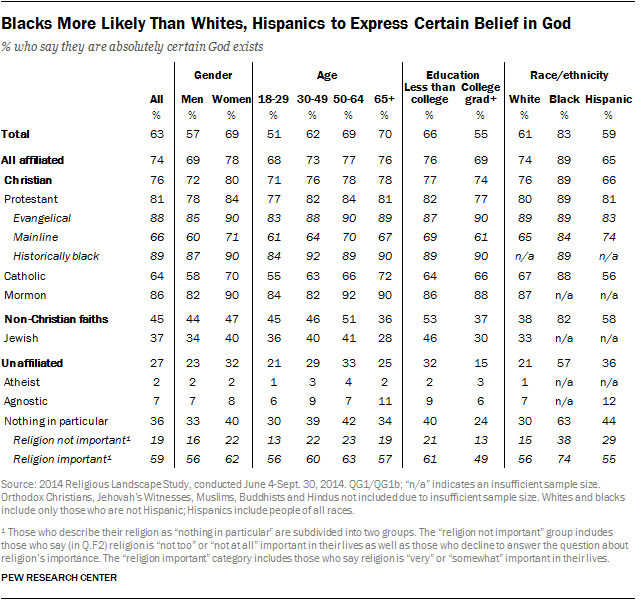

Women are much more likely than men to say they are absolutely certain about God’s existence (69% vs. 57%), and older Americans are much more likely than younger adults to say they are absolutely convinced that God exists. Two-thirds of those with less than a college degree express certainty about God’s existence, compared with 55% of college graduates. Additionally, 83% of blacks say they are absolutely certain about God’s existence, while roughly six-in-ten whites (61%) and Hispanics (59%) hold this view.

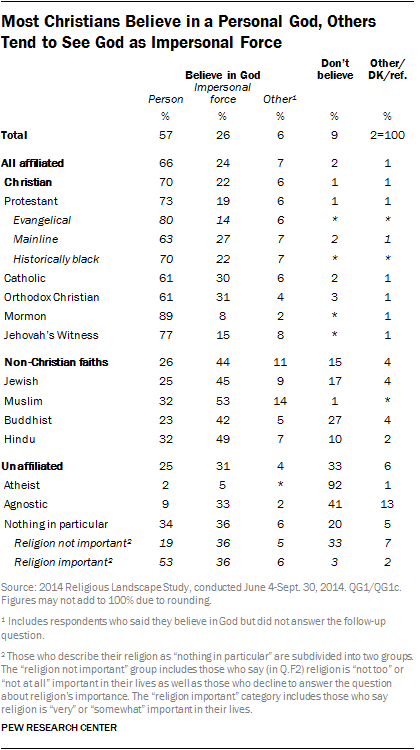

There is considerable variation in the way members of different religious groups conceive of God. For example, seven-in-ten Christians think of God as a person with whom people can have a relationship. Only about a quarter of those who belong to non-Christian faiths (26%) share this view. Among non-Christian faiths, it is more common to see God as an impersonal force.

Among the religiously unaffiliated, roughly three-in-ten (31%) say God is an impersonal force, a quarter say God is best viewed as a person and a third say God does not exist. However, among the subset of religious “nones” who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” and who also say religion is very or somewhat important in their lives, a slim majority (53%) say they believe in a personal God.

Although the share of adults who believe in God has declined modestly in recent years, among those who do believe in God, views about the nature of God are little changed since 2007. In both 2007 and 2014, roughly two-thirds of people who believe in God said they think of God as a person, while just under three-in-ten see God as an impersonal force.

Beliefs About the Afterlife

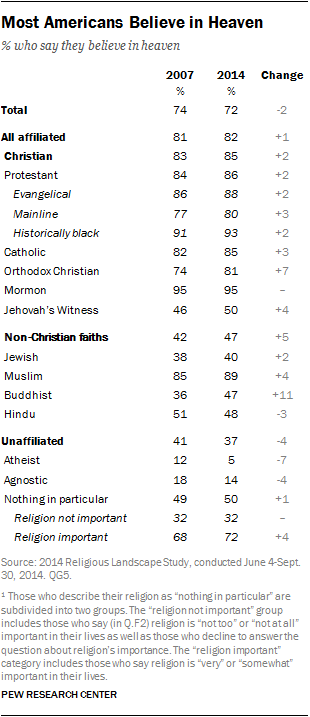

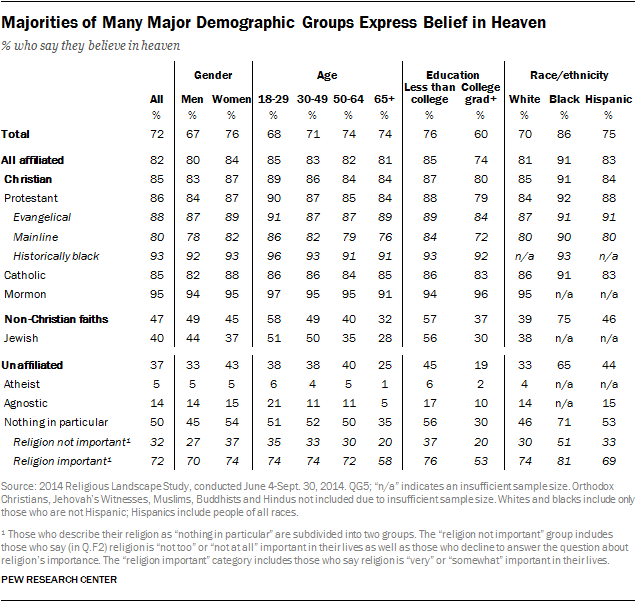

Roughly seven-in-ten Americans (72%) believe in “a heaven, where people who have led good lives are eternally rewarded.”

Belief in heaven is nearly universal among Mormons (95%) and members of the historically black Protestant tradition (93%). Belief in heaven also is widely held by evangelical Protestants (88%), Catholics (85%), Orthodox Christians (81%) and mainline Protestants (80%).

The vast majority of Muslims (89%) also believe in heaven. About half of Hindus in the survey (48%) say they believe in heaven, as do 47% of Buddhists surveyed.

The only groups where significantly fewer than half say they believe in heaven are Jews (40%) and the unaffiliated (37%). While relatively few atheists or agnostics believe in heaven, a large share of those whose religion is “nothing in particular” and who also say religion is at least somewhat important in their lives do believe in heaven (72%).

The survey also finds that, overall, women are more likely than men to say they believe in heaven, and those with less than a college degree are more likely than those with a college degree to express this view. Slightly bigger shares of blacks and Hispanics than whites say they believe in heaven, and older Americans are slightly more likely than younger adults to hold this belief. In many cases, however, these demographic differences in belief in heaven are smaller within religious traditions than among the public as a whole. Among evangelical Protestants, for example, men are just as likely as women to believe in heaven, and young people are just as likely as older evangelicals to hold this belief.

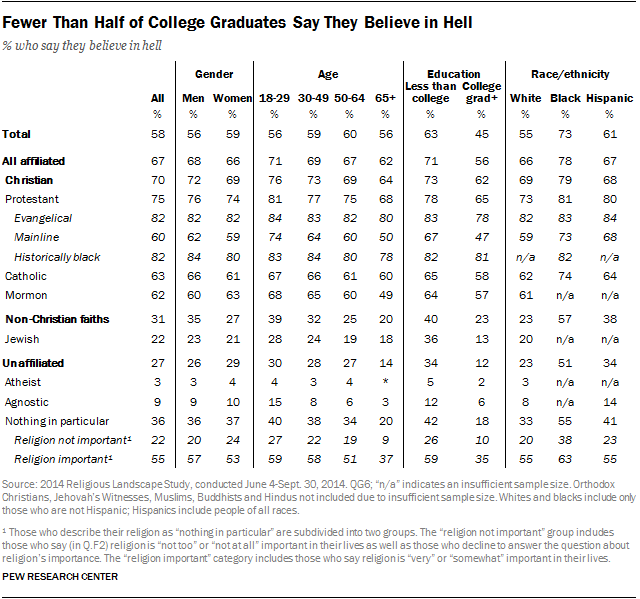

Belief in “hell, where people who have lived bad lives and die without being sorry are eternally punished,” is less widespread than belief in heaven. About six-in-ten Americans (58%) believe in hell, little changed from 2007.

Belief in hell is most common among members of historically black Protestant churches (82%) and evangelical Protestant churches (82%). Somewhat fewer Catholics (63%), Mormons (62%), mainline Protestants (60%) and Orthodox Christians (59%) say they believe in hell.

Three-quarters of U.S. Muslims (76%) believe in hell, but belief in hell is less common among other non-Christian groups, including Buddhists (32%), Hindus (28%), Jews (22%) and the religiously unaffiliated (27%).

U.S. adults with less than a college degree are more likely than college graduates to say they believe in hell, and blacks are more likely than Hispanics and whites to believe in hell. However, there are minimal differences between men and women and between younger and older adults on this question.

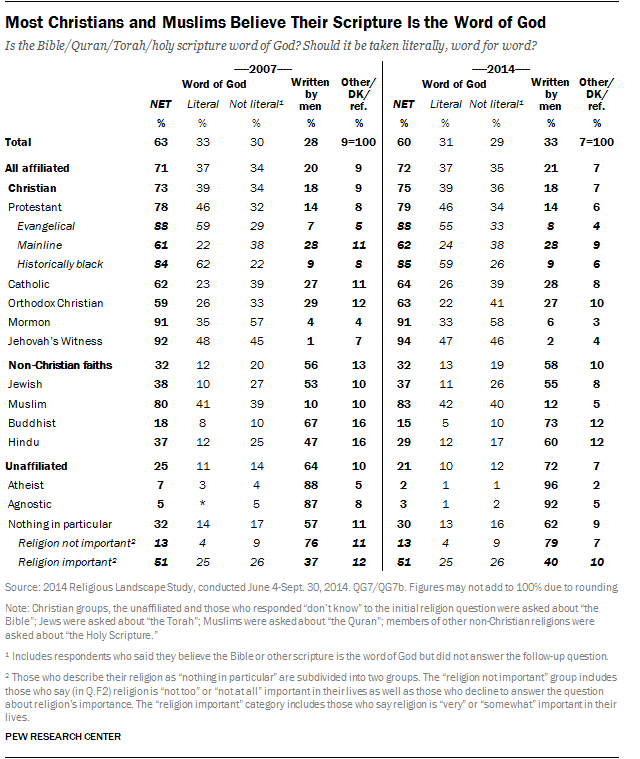

Beliefs About Holy Scripture

Six-in-ten Americans (60%) view their religion’s sacred text as the word of God. This represents a slight decline from 2007, when 63% of the public held this view. Within most religious groups, there has been little movement on this question, but among the unaffiliated, there has been a modest decline in the share who view the Bible as the word of God (from 25% to 21%).

Three-quarters of Christians believe the Bible is the word of God, including about nine-in-ten evangelicals (88%), Mormons (91%) and Jehovah’s Witnesses (94%). Among members of other Christian traditions, smaller majorities say the Bible is the word of God.

Although there is widespread agreement across Christian groups on this question, there is disagreement about whether the Bible can be taken “literally, word for word.” Most evangelical Protestants (55%) and members of historically black Protestant churches (59%) believe the Bible should be taken literally, but fewer Christians from other traditions espouse a literalist view of the Bible. There has been little change in recent years in the share of Christians who believe the Bible should be interpreted literally, word for word.

Most Muslims (83%) accept the Quran (also spelled Koran) as the word of God. Far fewer Jews (37%), Hindus (29%) and Buddhists (15%) say their scripture is the word of God.

The share of the unaffiliated who believe the Bible was written by men and is not the word of God has risen by 8 percentage points in recent years, from 64% in 2007 to 72% in 2014. But while most religious “nones” say the Bible was written by men, about half of those who say they have no particular religion and who also say religion is at least somewhat important in their lives believe the Bible is the word of God (51%).

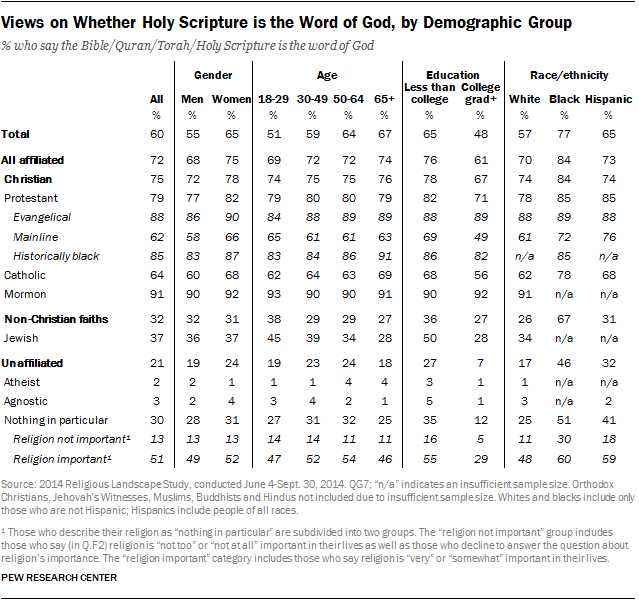

As on some other traditional measures of religious belief, older adults are more likely than younger adults to say their religion’s holy text is the word of God. And those with less than a college degree also are much more likely than college graduates to say their religion’s scripture is the word of God. Additionally, more women than men and more blacks than Hispanics and whites say their religion’s holy text is the word of God. For the most part, however, differences in beliefs about the Bible are larger across religious traditions (e.g., between evangelicals and Catholics and religious “nones”) than differences between demographic groups within the same religious tradition.

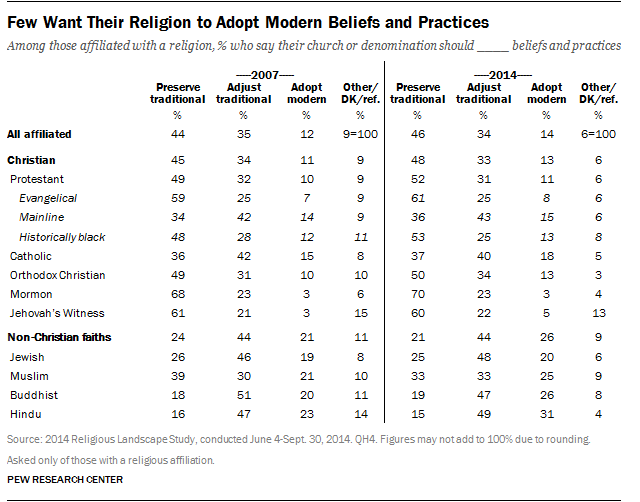

Beliefs About Religion and Modernity

Respondents in the survey who are affiliated with a religion were asked to choose one of three statements that best reflects their view of how their religion should engage with modernity. A plurality of religiously affiliated Americans (46%) believe their religion should “preserve traditional beliefs and practices.” A third (34%) say their congregation or denomination should “adjust traditional beliefs and practices in light of new circumstances.” Only 14% of people who are affiliated with a religious tradition say their religion should “adopt modern beliefs and practices.”

These findings are little changed from 2007, when 44% of affiliated respondents said their religion should preserve its traditional beliefs and practices, 35% said their religion should adjust its traditional beliefs and 12% said their religion should adopt modern beliefs and practices.

The belief that their religion should preserve traditional practices is held by most Mormons (70%), Jehovah’s Witnesses (60%), evangelical Protestants (61%) and members of historically black Protestant churches (53%), as well as half of Orthodox Christians (50%).

Muslims are closely divided on whether their religion should preserve traditional beliefs and practices or adjust traditional beliefs and practices in light of new circumstances. Among other religious groups, including Jews, mainline Protestants and Catholics, the most common view is that religions should adjust traditional practices.

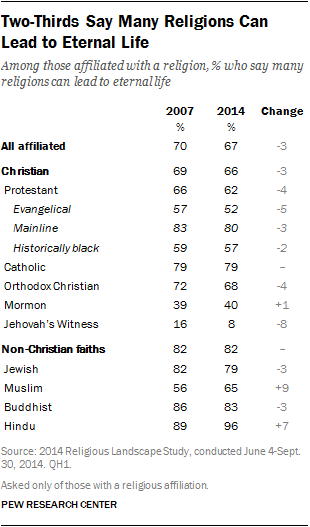

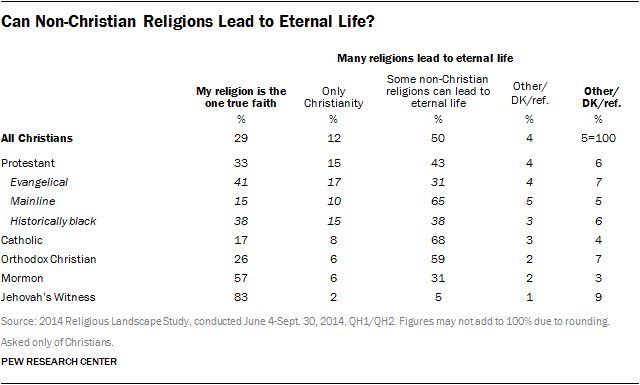

Paths to Eternal Life

Two-thirds of those who identify with a religious group say many religions (not just their own) can lead to eternal life, down slightly from 2007, when 70% of all religiously affiliated adults said this.

This view is held by the vast majority of mainline Protestants (80%) and Catholics (79%), as well as smaller majorities of Orthodox Christians (68%) and members of historically black Protestant churches (57%) and about half of evangelicals (52%). Fewer than half of Mormons (40%) and only about one-in-ten Jehovah’s Witnesses (8%) believe that many religions can lead to eternal life.

Among the non-Christian religious traditions that are large enough to be analyzed, most say many religions can lead to eternal life.

Most Christians who say many religions can lead to eternal life also say non-Christian religions can lead to heaven. In fact, half of all Christians say some non-Christian faiths can lead to eternal life, while about four-in-ten say either that theirs is the one true faith leading to eternal life or that only Christianity can result in everlasting life. About one-in-ten Christians express no opinion or provide other views on these matters.

Two-thirds of Catholics (68%) and mainline Protestants (65%) say some non-Christian religions can lead to eternal life, as do 59% of Orthodox Christians. This view is less common among other Christian groups. Roughly four-in-ten members of historically black Protestant denominations (38%) say some non-Christian religions can lead to eternal life, as do three-in-ten evangelical Protestants and Mormons (31% each). Very few Jehovah’s Witnesses (5%) believe this.

Religion and Morality

When looking for answers to questions about right and wrong, more Americans say they turn to practical experience and common sense (45%) than to any other source of guidance. The next most common source of guidance is religious beliefs and teachings (33%), while far fewer turn to philosophy and reason (11%) or scientific information (9%).

Since the 2007 Religious Landscape Study, however, the share of U.S. adults who say they turn to practical experience has decreased by 7 percentage points (from 52% to 45%) while the share who say they look to religious teachings has increased by 4 points (from 29% to 33%). This turn to religious teachings as a source of moral guidance has occurred across many religious traditions, with the largest increases among evangelical Protestants and Catholics.

Six-in-ten or more evangelical Protestants, Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses say they turn to religious teachings and beliefs for moral guidance. Members of historically black Protestant churches are more divided: 47% say they rely on religious teachings while 41% rely on practical experience. Fewer Catholics (30%), mainline Protestants (29%) and Orthodox Christians (27%) turn primarily to religion for guidance on questions of right and wrong.

Fewer religious “nones” now say they use common sense and practical experience as their main source of guidance in this area (57%) than said this in 2007 (66%). But instead of finding guidance through religious teachings, more of the “nones” are turning to scientific information; the share who say they rely on scientific information has increased from 10% to 17% in recent years. The reliance on science is most common among self-identified atheists; one-third of this group (32%) relies primarily on scientific information for guidance on questions of right and wrong.

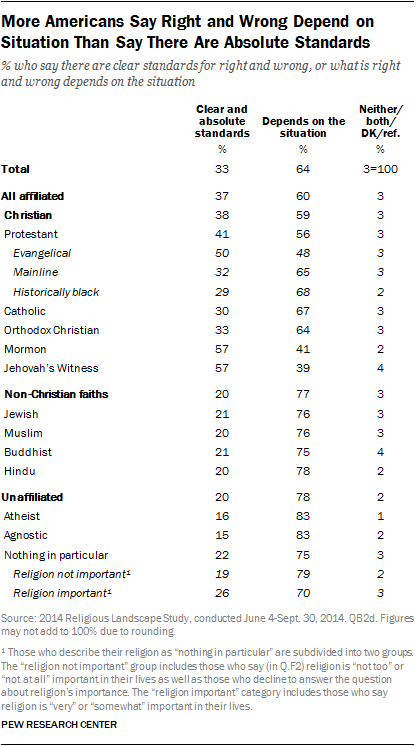

Nearly two-thirds of U.S. adults (64%) say that whether something is right or wrong depends on the situation, while a third say there are clear and absolute standards for what is right or wrong. In 2007, a different question about moral absolutes found that 39% of Americans completely agreed with the statement “there are clear and absolute standards for what is right and wrong.”

While Christians overall are more likely than members of other religious groups to say there are absolute standards for right and wrong, there are large differences within Christianity. Nearly six-in-ten Mormons (57%) and Jehovah’s Witnesses (57%) say there are clear standards for right and wrong. Evangelical Protestants are divided in their opinions, with 50% saying there are absolute standards and 48% saying it depends on the situation. Fewer Orthodox Christians (33%), mainline Protestants (32%), Catholics (30%) and members of the historically black Protestant tradition (29%) say there are clear and absolute standards of right and wrong.

Among members of non-Christian faiths, about three-quarters assert that determining right from wrong is often situational. Similarly, more than eight-in-ten atheists and agnostics express this view, as do three-quarters of those whose religion is “nothing in particular.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- Catholicism

- Christianity

- Evangelicalism

- Religion & Politics

- Religiously Unaffiliated

- Trust in Government

- Trust, Facts & Democracy

Where is the most religious place in the world?

Rituals honoring deceased ancestors vary widely in east and southeast asia, 6 facts about religion and spirituality in east asian societies, religion and spirituality in east asian societies, 8 facts about atheists, most popular, report materials.

- Religious Landscape Study

- RLS national telephone survey questionnaire

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

Why study religion?

Big questions.

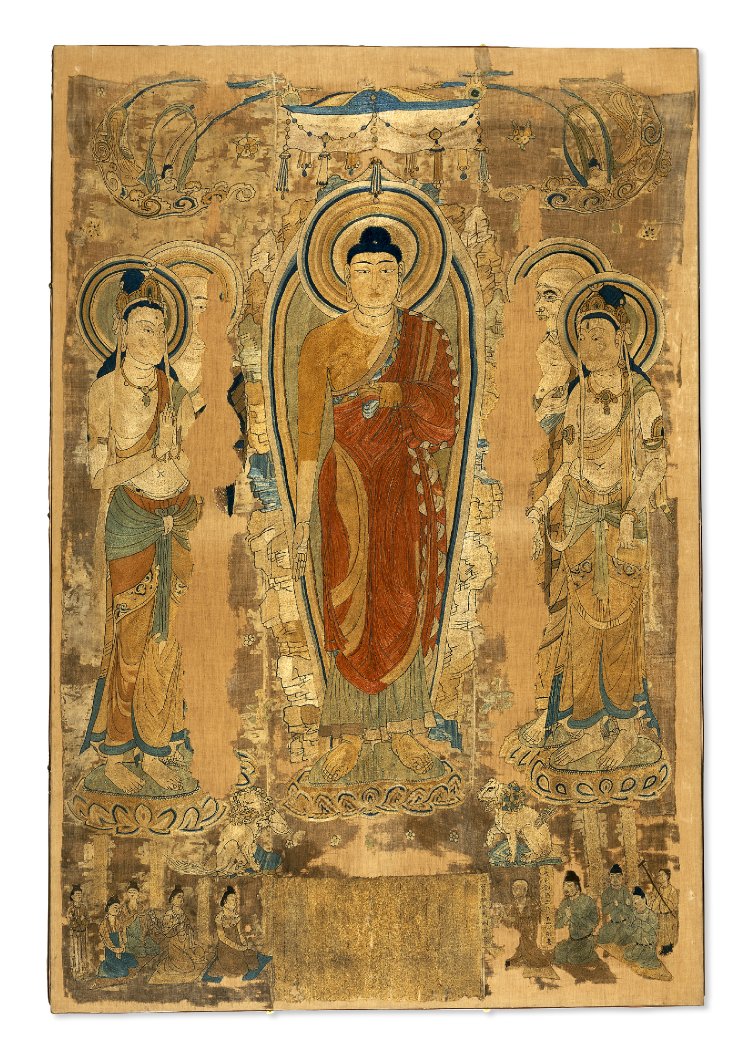

Whether you consider yourself a religious person or not, or whether you think religion has played a positive or negative role in history, it is an incontrovertible fact that from the beginning of time, humans have engaged in activities that we now call religion, such as worship, prayer, and rituals marking important life passages. Moreover, religions have always asked fundamental questions, such as: What is the true meaning of life? What happens to us after death? How do we explain human suffering and injustices?

Human Understanding

The answers different religious traditions give to these important questions are many and varied and often contradictory. But the questions themselves are ones with which humans throughout time have grappled, and probably will continue to grapple with into the indefinite future. Thus, one of the first reasons to study religion is simply to deepen our understanding of others and ourselves, even as we pursue other realms of knowledge.

Cultural Influence

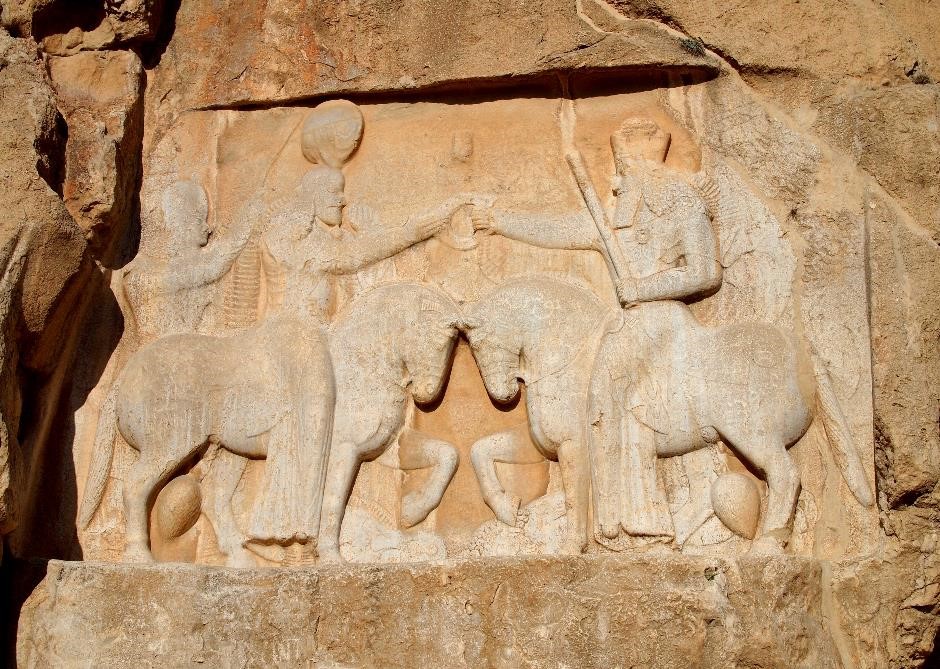

We also study religion in order to learn more about how different aspects of human life—politics, science, literature, art, law, economics—have been and continue to be shaped by changing religious notions of, for example, good and evil, images of the deity and the divine, salvation and punishment, etc. By studying different religious doctrines, rituals, stories, and scriptures, we can also come to understand how different communities of believers—past and present, East and West—have used their religious traditions to shape, sustain, transform themselves.

Global Insight

More than ever before, the world we live in is both multicultural and global. We no longer need to travel across the ocean to visit a Hindu temple or an Islamic mosque or to meet a Sikh or a Jain. The chances are that you can find a temple or mosque within a few miles of where you live, and it is almost certain that you will be meet someone from any and all of these religious traditions on campus or on the street. This makes it even more essential that we cultivate our ability to understand and interpret other people’s religious traditions.

Interdisciplinary

Finally, the academic study of religion is inherently multidisciplinary. This is reflected in our program here at Washington University, which draws faculty from different disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences, such as history, anthropology, literature, art history, and political science. Studying religion thus provides you an opportunity to learn about a range of disciplinary approaches, and, even more importantly, the connections and linkages among them. In this way studying religion invites us all to think in a more interdisciplinary and integral way about the world and our place in it.

Ready to learn more?

Reach out to us if you're curious about studying religion at WashU. Or, check out our event page for upcoming social events where you can meet current religious studies faculty and students!

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 The Purpose of Religion

Author Webpage

- Published: September 2005

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The purposes of the practice of a religion are to achieve the goals of salvation for oneself and others, and (if there is a God) to render due worship and obedience to God. Different religions have different understandings of salvation and God. It is rational for someone to pursue these goals by following a religious way (the practices commended by some religion, e.g., Buddhism or Christianity), in so far as they judge that it would be greatly worthwhile to achieve those goals and in so far as they judge that it is to some degree probable that they will attain them by following the way of that religion. They will judge that in so far as they judge the creed of that religion to be to some degree probable (not necessarily more probable than not). The goals of the Christian religion are better than those of Buddhism.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 49 |

| November 2022 | 26 |

| December 2022 | 28 |

| January 2023 | 20 |

| February 2023 | 23 |

| March 2023 | 17 |

| April 2023 | 31 |

| May 2023 | 16 |

| June 2023 | 19 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| August 2023 | 20 |

| September 2023 | 9 |

| October 2023 | 29 |

| November 2023 | 26 |

| December 2023 | 24 |

| January 2024 | 19 |

| February 2024 | 18 |

| March 2024 | 13 |

| April 2024 | 42 |

| May 2024 | 13 |

| June 2024 | 6 |

| July 2024 | 17 |

| August 2024 | 4 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Does Ethics Require Religion?

There is a spectrum of views about how religion and ethics are related—from the view that religion is the absolute bedrock of ethics to one that holds that ethics is based on humanistic assumptions justified mainly, and sometimes only, by appeals to reason. These two extremes tend to be argued in a way that offers little room for compromise or pragmatic solutions to real issues we face everyday.

The relationship between religion and ethics is about the relationship between revelation and reason. Religion is based in some measure on the idea that God (or some deity) reveals insights about life and its true meaning. These insights are collected in texts (the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, etc.) and presented as “revelation.” Ethics, from a strictly humanistic perspective, is based on the tenets of reason: Anything that is not rationally verifiable cannot be considered justifiable. From this perspective, ethical principles need not derive their authority from religious doctrine. Instead, these principles are upheld for their value in promoting independent and responsible individuals—people who are capable of making decisions that maximize their own well-being while respecting the well-being of others.

Even though religious and secular ethics don’t derive their authority from the same source, we still must find a way to establish common ground between them; otherwise we’re condemning ourselves to live amidst social discord and division.

I believe we can accommodate the requirements of reason and religion by developing certain qualities that we would bring to our everyday ethical discussions. Aristotle said that cultivating qualities (he called them “virtues”) like prudence, reason, accommodation, compromise, moderation, wisdom, honesty, and truthfulness, among others, would enable us all to enter the discussions and conflicts between religion and ethics—where differences exist—with a measure of moderation and agreement. When ethics and religion collide, nobody wins; when religion and ethics find room for robust discussion and agreement, we maximize the prospects for constructive choices in our society.

About the Author

James a. donahue.

James A. Donahue, Ph.D., is the president and a professor of ethics at the Graduate Theological Union.

You May Also Enjoy

Moral Monkeys

Do we need God to be good?

Moral intuition.

The Science of Spirituality: A Review of Fingerprints of God

Empathy vs. logic vs. morality.

- Access your dashboard and other settings here.

- My Dashboard

- What's your big question?

- What's New

Do humans | need religion?

For many people across the world, religion plays an important part in their daily lives and identities. While others lead happy lives without believing in a god(s). Why do some of us feel the ‘need to believe’?

Crunching the numbers!

Where are people least likely to think that a belief in God is key to being a good person?

- Britain

- Germany