Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

Published on March 31, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

An observational study is used to answer a research question based purely on what the researcher observes. There is no interference or manipulation of the research subjects, and no control and treatment groups .

These studies are often qualitative in nature and can be used for both exploratory and explanatory research purposes. While quantitative observational studies exist, they are less common.

Observational studies are generally used in hard science, medical, and social science fields. This is often due to ethical or practical concerns that prevent the researcher from conducting a traditional experiment . However, the lack of control and treatment groups means that forming inferences is difficult, and there is a risk of confounding variables and observer bias impacting your analysis.

Table of contents

Types of observation, types of observational studies, observational study example, advantages and disadvantages of observational studies, observational study vs. experiment, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

There are many types of observation, and it can be challenging to tell the difference between them. Here are some of the most common types to help you choose the best one for your observational study.

| The researcher observes how the participants respond to their environment in “real-life” settings but does not influence their behavior in any way | Observing monkeys in a zoo enclosure | |

| Also occurs in “real-life” settings, but here, the researcher immerses themselves in the participant group over a period of time | Spending a few months in a hospital with patients suffering from a particular illness | |

| Utilizing coding and a strict observational schedule, researchers observe participants in order to count how often a particular phenomenon occurs | Counting the number of times children laugh in a classroom | |

| Hinges on the fact that the participants do not know they are being observed | Observing interactions in public spaces, like bus rides or parks | |

| Involves counting or numerical data | Observations related to age, weight, or height | |

| Involves “five senses”: sight, sound, smell, taste, or hearing | Observations related to colors, sounds, or music | |

| Investigates a person or group of people over time, with the idea that close investigation can later be to other people or groups | Observing a child or group of children over the course of their time in elementary school | |

| Utilizes primary sources from libraries, archives, or other repositories to investigate a | Analyzing US Census data or telephone records |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

There are three main types of observational studies: cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies .

Cohort studies

Cohort studies are more longitudinal in nature, as they follow a group of participants over a period of time. Members of the cohort are selected because of a shared characteristic, such as smoking, and they are often observed over a period of years.

Case–control studies

Case–control studies bring together two groups, a case study group and a control group . The case study group has a particular attribute while the control group does not. The two groups are then compared, to see if the case group exhibits a particular characteristic more than the control group.

For example, if you compared smokers (the case study group) with non-smokers (the control group), you could observe whether the smokers had more instances of lung disease than the non-smokers.

Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies analyze a population of study at a specific point in time.

This often involves narrowing previously collected data to one point in time to test the prevalence of a theory—for example, analyzing how many people were diagnosed with lung disease in March of a given year. It can also be a one-time observation, such as spending one day in the lung disease wing of a hospital.

Observational studies are usually quite straightforward to design and conduct. Sometimes all you need is a notebook and pen! As you design your study, you can follow these steps.

Step 1: Identify your research topic and objectives

The first step is to determine what you’re interested in observing and why. Observational studies are a great fit if you are unable to do an experiment for practical or ethical reasons , or if your research topic hinges on natural behaviors.

Step 2: Choose your observation type and technique

In terms of technique, there are a few things to consider:

- Are you determining what you want to observe beforehand, or going in open-minded?

- Is there another research method that would make sense in tandem with an observational study?

- If yes, make sure you conduct a covert observation.

- If not, think about whether observing from afar or actively participating in your observation is a better fit.

- How can you preempt confounding variables that could impact your analysis?

- You could observe the children playing at the playground in a naturalistic observation.

- You could spend a month at a day care in your town conducting participant observation, immersing yourself in the day-to-day life of the children.

- You could conduct covert observation behind a wall or glass, where the children can’t see you.

Overall, it is crucial to stay organized. Devise a shorthand for your notes, or perhaps design templates that you can fill in. Since these observations occur in real time, you won’t get a second chance with the same data.

Step 3: Set up your observational study

Before conducting your observations, there are a few things to attend to:

- Plan ahead: If you’re interested in day cares, you’ll need to call a few in your area to plan a visit. They may not all allow observation, or consent from parents may be needed, so give yourself enough time to set everything up.

- Determine your note-taking method: Observational studies often rely on note-taking because other methods, like video or audio recording, run the risk of changing participant behavior.

- Get informed consent from your participants (or their parents) if you want to record: Ultimately, even though it may make your analysis easier, the challenges posed by recording participants often make pen-and-paper a better choice.

Step 4: Conduct your observation

After you’ve chosen a type of observation, decided on your technique, and chosen a time and place, it’s time to conduct your observation.

Here, you can split them into case and control groups. The children with siblings have a characteristic you are interested in (siblings), while the children in the control group do not.

When conducting observational studies, be very careful of confounding or “lurking” variables. In the example above, you observed children as they were dropped off, gauging whether or not they were upset. However, there are a variety of other factors that could be at play here (e.g., illness).

Step 5: Analyze your data

After you finish your observation, immediately record your initial thoughts and impressions, as well as follow-up questions or any issues you perceived during the observation. If you audio- or video-recorded your observations, you can transcribe them.

Your analysis can take an inductive or deductive approach :

- If you conducted your observations in a more open-ended way, an inductive approach allows your data to determine your themes.

- If you had specific hypotheses prior to conducting your observations, a deductive approach analyzes whether your data confirm those themes or ideas you had previously.

Next, you can conduct your thematic or content analysis . Due to the open-ended nature of observational studies, the best fit is likely thematic analysis .

Step 6: Discuss avenues for future research

Observational studies are generally exploratory in nature, and they often aren’t strong enough to yield standalone conclusions due to their very high susceptibility to observer bias and confounding variables. For this reason, observational studies can only show association, not causation .

If you are excited about the preliminary conclusions you’ve drawn and wish to proceed with your topic, you may need to change to a different research method , such as an experiment.

- Observational studies can provide information about difficult-to-analyze topics in a low-cost, efficient manner.

- They allow you to study subjects that cannot be randomized safely, efficiently, or ethically .

- They are often quite straightforward to conduct, since you just observe participant behavior as it happens or utilize preexisting data.

- They’re often invaluable in informing later, larger-scale clinical trials or experimental designs.

Disadvantages

- Observational studies struggle to stand on their own as a reliable research method. There is a high risk of observer bias and undetected confounding variables or omitted variables .

- They lack conclusive results, typically are not externally valid or generalizable, and can usually only form a basis for further research.

- They cannot make statements about the safety or efficacy of the intervention or treatment they study, only observe reactions to it. Therefore, they offer less satisfying results than other methods.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that a properly conducted observational study will never attempt to influence responses, while experimental designs by definition have some sort of treatment condition applied to a portion of participants.

However, there may be times when it’s impossible, dangerous, or impractical to influence the behavior of your participants. This can be the case in medical studies, where it is unethical or cruel to withhold potentially life-saving intervention, or in longitudinal analyses where you don’t have the ability to follow your group over the course of their lifetime.

An observational study may be the right fit for your research if random assignment of participants to control and treatment groups is impossible or highly difficult. However, the issues observational studies raise in terms of validity , confounding variables, and conclusiveness can mean that an experiment is more reliable.

If you’re able to randomize your participants safely and your research question is definitely causal in nature, consider using an experiment.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

An observational study is a great choice for you if your research question is based purely on observations. If there are ethical, logistical, or practical concerns that prevent you from conducting a traditional experiment , an observational study may be a good choice. In an observational study, there is no interference or manipulation of the research subjects, as well as no control or treatment groups .

The key difference between observational studies and experimental designs is that a well-done observational study does not influence the responses of participants, while experiments do have some sort of treatment condition applied to at least some participants by random assignment .

A quasi-experiment is a type of research design that attempts to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. The main difference with a true experiment is that the groups are not randomly assigned.

Exploratory research aims to explore the main aspects of an under-researched problem, while explanatory research aims to explain the causes and consequences of a well-defined problem.

Experimental design means planning a set of procedures to investigate a relationship between variables . To design a controlled experiment, you need:

- A testable hypothesis

- At least one independent variable that can be precisely manipulated

- At least one dependent variable that can be precisely measured

When designing the experiment, you decide:

- How you will manipulate the variable(s)

- How you will control for any potential confounding variables

- How many subjects or samples will be included in the study

- How subjects will be assigned to treatment levels

Experimental design is essential to the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/observational-study/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, naturalistic observation | definition, guide & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

What is an Observational Study: Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost 10 Comments

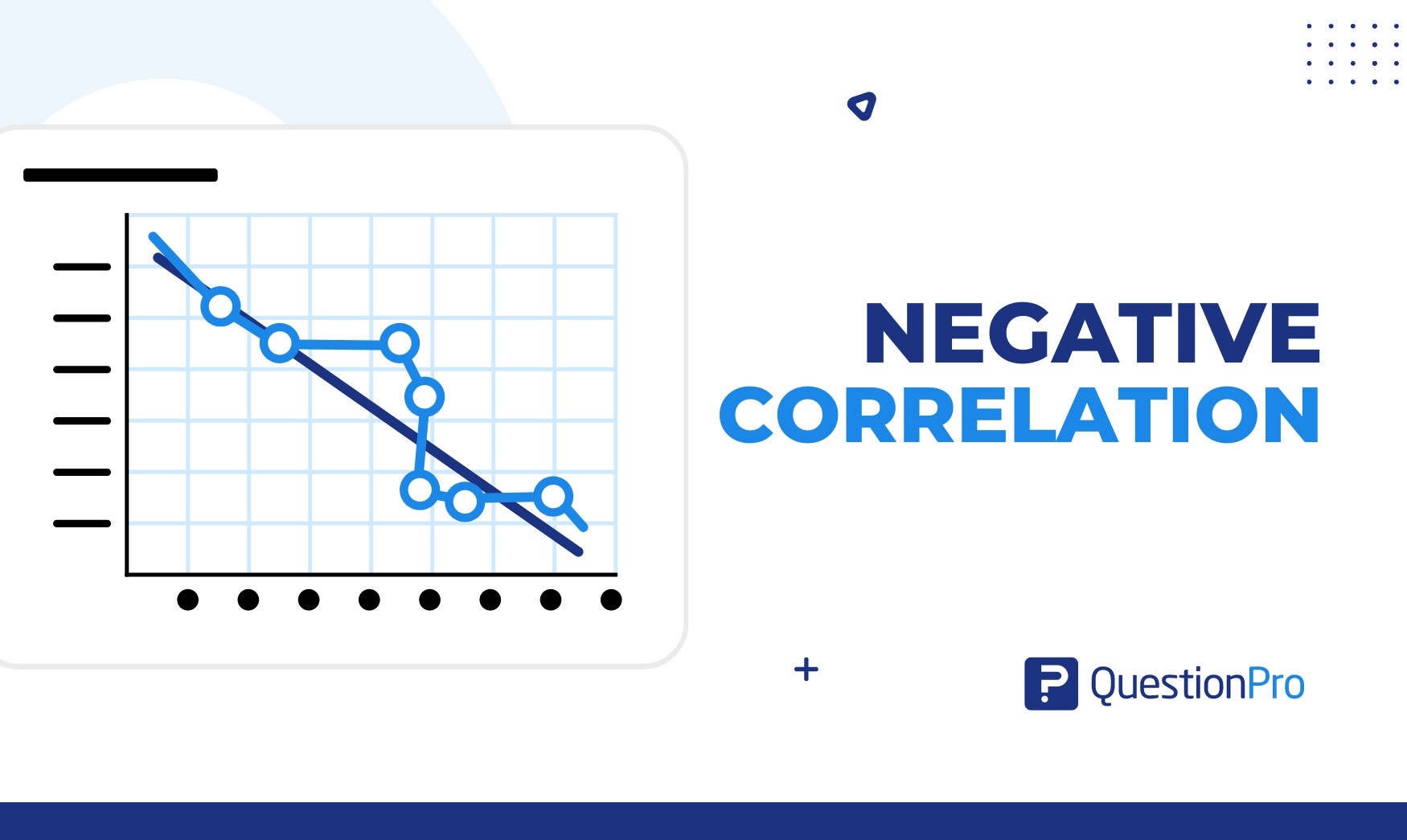

What is an Observational Study?

An observational study uses sample data to find correlations in situations where the researchers do not control the treatment, or independent variable, that relates to the primary research question. The definition of an observational study hinges on the notion that the researchers only observe subjects and do not assign them to the control and treatment groups. That’s the key difference between an observational study vs experiment. These studies are also known as quasi-experiments and correlational studies .

True experiments assign subject to the experimental groups where the researchers can manipulate the conditions. Unfortunately, random assignment is not always possible. For these cases, you can conduct an observational study.

In this post, learn about the types of observational studies, why they are susceptible to confounding variables, and how they compare to experiments. I’ll close this post by reviewing a published observational study about vitamin supplement usage.

Observational Study Definition

In an observational study, the researchers only observe the subjects and do not interfere or try to influence the outcomes. In other words, the researchers do not control the treatments or assign subjects to experimental groups. Instead, they observe and measure variables of interest and look for relationships between them. Usually, researchers conduct observational studies when it is difficult, impossible, or unethical to assign study participants to the experimental groups randomly. If you can’t randomly assign subjects to the treatment and control groups, then you observe the subjects in their self-selected states.

Observational Study vs Experiment

Randomized experiments provide better results than observational studies. Consequently, you should always use a randomized experiment whenever possible. However, if randomization is not possible, science should not come to a halt. After all, we still want to learn things, discover relationships, and make discoveries. For these cases, observational studies are a good alternative to a true experiment. Let’s compare the differences between an observational study vs. an experiment.

Random assignment in an experiment reduces systematic differences between experimental groups at the beginning of the study, which increases your confidence that the treatments caused any differences between groups you observe at the end of the study. In contrast, an observational study uses self-formed groups that can have pre-existing differences, which introduces the problem of confounding variables. More on that later!

In a randomized experiment, randomization tends to equalize confounders between groups and, thereby, prevents problems. In my post about random assignment , I describe that process as an elegant solution for confounding variables. You don’t need to measure or even know which variables are confounders, and randomization will still mitigate their effects. Additionally, you can use control variables in an experiment to keep the conditions as consistent as possible. For more detail about the differences, read Observational Study vs. Experiment .

|

| |

| Does not assign subjects to groups | Randomly assigns subjects to control and treatment groups |

| Does not control variables that can affect outcome | Administers treatments and controls influence of other variables |

| Correlational findings. Differences might be due to confounders rather than the treatment | More confident that treatments cause the differences in outcomes |

If you’re looking for a middle ground choice between observational studies vs experiments, consider using a quasi-experimental design. These methods don’t require you to randomly assign participants to the experimental groups and still allow you to draw better causal conclusions about an intervention than an observational study. Learn more about Quasi-Experimental Design Overview & Examples .

Related posts : Experimental Design: Definition and Examples , Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) , and Control Groups in Experiments

Observational Study Examples

Consider using an observational study when random assignment for an experiment is problematic. This approach allows us to proceed and draw conclusions about effects even though we can’t control the independent variables. The following observational study examples will help you understand when and why to use them.

For example, if you’re studying how depression affects performance of an activity, it’s impossible to assign subjects to the depression and control group randomly. However, you can have subjects with and without depression perform the activity and compare the results in an observational study.

Or imagine trying to assign subjects to cigarette smoking and non-smoking groups randomly?! However, you can observe people in both groups and assess the differences in health outcomes in an observational study.

Suppose you’re studying a treatment for a disease. Ideally, you recruit a group of patients who all have the disease, and then randomly assign them to the treatment and control group. However, it’s unethical to withhold the treatment, which rules out a control group. Instead, you can compare patients who voluntarily do not use the medicine to those who do use it.

In all these observational study examples, the researchers do not assign subjects to the experimental groups. Instead, they observe people who are already in these groups and compare the outcomes. Hence, the scientists must use an observational study vs. an experiment.

Types of Observational Studies

The observational study definition states that researchers only observe the outcomes and do not manipulate or control factors . Despite this limitation, there various types of observational studies.

The following experimental designs are three standard types of observational studies.

- Cohort Study : A longitudinal observational study that follows a group who share a defining characteristic. These studies frequently determine whether exposure to risk factor affects an outcome over time.

- Case-Control Study : A retrospective observational study that compares two existing groups—the case group with the condition and the control group without it. Researchers compare the groups looking for potential risk factors for the condition.

- Cross-Sectional Study : Takes a snapshot of a moment in time so researchers can understand the prevalence of outcomes and correlations between variables at that instant.

Qualitative research studies are usually observational in nature, but they collect non-numeric data and do not perform statistical analyses.

Retrospective studies must be observational.

Later in this post, we’ll closely examine a quantitative observational study example that assesses vitamin supplement consumption and how that affects the risk of death. It’s possible to use random assignment to place each subject in either the vitamin treatment group or the control group. However, the study assesses vitamin consumption in 40,000 participants over the course of two decades. It’s unrealistic to enforce the treatment and control protocols over such a long time for so many people!

Drawbacks of Observational Studies

While observational studies get around the inability to assign subjects randomly, this approach opens the door to the problem of confounding variables. A confounding variable, or confounder, correlates with both the experimental groups and the outcome variable. Because there is no random process that equalizes the experimental groups in an observational study, confounding variables can systematically differ between groups when the study begins. Consequently, confounders can be the actual cause for differences in outcome at the end of the study rather than the primary variable of interest. If an experiment does not account for confounding variables, confounders can bias the results and create spurious correlations .

Performing an observational study can decrease the internal validity of your study but increase the external validity. Learn more about internal and external validity .

Let’s see how this works. Imagine an observational study that compares people who take vitamin supplements to those who do not. People who use vitamin supplements voluntarily will tend to have other healthy habits that exist at the beginning of the study. These healthy habits are confounding variables. If there are differences in health outcomes at the end of the study, it’s possible that these healthy habits actually caused them rather than the vitamin consumption itself. In short, confounders confuse the results because they provide alternative explanations for the differences.

Despite the limitations, an observational study can be a valid approach. However, you must ensure that your research accounts for confounding variables. Fortunately, there are several methods for doing just that!

Learn more about Correlation vs. Causation: Understanding the Differences .

Accounting for Confounding Variables in an Observational Study

Because observational studies don’t use random assignment, confounders can be distributed disproportionately between conditions. Consequently, experimenters need to know which variables are confounders, measure them, and then use a method to account for them. It involves more work, and the additional measurements can increase the costs. And there’s always a chance that researchers will fail to identify a confounder, not account for it, and produce biased results. However, if randomization isn’t an option, then you probably need to consider an observational study.

Trait matching and statistically controlling confounders using multivariate procedures are two standard approaches for incorporating confounding variables.

Related post : Causation versus Correlation in Statistics

Matching in Observational Studies

Matching is a technique that involves selecting study participants with similar characteristics outside the variable of interest or treatment. Rather than using random assignment to equalize the experimental groups, the experimenters do it by matching observable characteristics. For every participant in the treatment group, the researchers find a participant with comparable traits to include in the control group. Matching subjects facilitates valid comparisons between those groups. The researchers use subject-area knowledge to identify characteristics that are critical to match.

For example, a vitamin supplement study using matching will select subjects who have similar health-related habits and attributes. The goal is that vitamin consumption will be the primary difference between the groups, which helps you attribute differences in health outcomes to vitamin consumption. However, the researchers are still observing participants who decide whether they consume supplements.

Matching has some drawbacks. The experimenters might not be aware of all the relevant characteristics they need to match. In other words, the groups might be different in an essential aspect that the researchers don’t recognize. For example, in the hypothetical vitamin study, there might be a healthy habit or attribute that affects the outcome that the researchers don’t measure and match. These unmatched characteristics might cause the observed differences in outcomes rather than vitamin consumption.

Learn more about Matched Pairs Design: Uses & Examples .

Using Multiple Regression in Observational Studies

Random assignment and matching use different methods to equalize the experimental groups in an observational study. However, statistical techniques, such as multiple regression analysis , don’t try to equalize the groups but instead use a model that accounts for confounding variables. These studies statistically control for confounding variables.

In multiple regression analysis, including a variable in the model holds it constant while you vary the variable/treatment of interest. For information about this property, read my post When Should I Use Regression Analysis?

As with matching, the challenge is to identify, measure, and include all confounders in the regression model. Failure to include a confounding variable in a regression model can cause omitted variable bias to distort your results.

Next, we’ll look at a published observational study that uses multiple regression to account for confounding variables.

Related post : Independent and Dependent Variables in a Regression Model

Vitamin Supplement Observational Study Example

Murso et al. (2011)* use a longitudinal observational study that ran 22 years to assess differences in death rates for subjects who used vitamin supplements regularly compared to those who did not use them. This study used surveys to record the characteristics of approximately 40,000 participants. The surveys asked questions about potential confounding variables such as demographic information, food intake, health details, physical activity, and, of course, supplement intake.

Because this is an observational study, the subjects decided for themselves whether they were taking vitamin supplements. Consequently, it’s safe to assume that supplement users and non-users might be different in other ways. From their article, the researchers found the following pre-existing differences between the two groups:

Supplement users had a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, and smoking status; a lower BMI and waist to hip ratio, and were less likely to live on a farm. Supplement users had a higher educational level, were more physically active and were more likely to use estrogen replacement therapy. Also, supplement users were more likely to have a lower intake of energy, total fat, and monounsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids and to have a higher intake of protein, carbohydrates, polyunsaturated fatty acids, alcohol, whole grain products, fruits, and vegetables.

Whew! That’s a long list of differences! Supplement users were different from non-users in a multitude of ways that are likely to affect their risk of dying. The researchers must account for these confounding variables when they compare supplement users to non-users. If they do not, their results can be biased.

This example illustrates a key difference between an observational study vs experiment. In a randomized experiment, the randomization would have equalized the characteristics of those the researchers assigned to the treatment and control groups. Instead, the study works with self-sorted groups that have numerous pre-existing differences!

Using Multiple Regression to Statistically Control for Confounders

To account for these initial differences in the vitamin supplement observational study, the researchers use regression analysis and include the confounding variables in the model.

The researchers present three regression models. The simplest model accounts only for age and caloric intake. Next, are two models that include additional confounding variables beyond age and calories. The first model adds various demographic information and seven health measures. The second model includes everything in the previous model and adds several more specific dietary intake measures. Using statistical significance as a guide for specifying the correct regression model , the researchers present the model with the most variables as the basis for their final results.

It’s instructive to compare the raw results and the final regression results.

Raw results

The raw differences in death risks for consumers of folic acid, vitamin B6, magnesium, zinc, copper, and multivitamins are NOT statistically significant. However, the raw results show a significant reduction in the death risk for users of B complex, C, calcium, D, and E.

However, those are the raw results for the observational study, and they do not control for the long list of differences between the groups that exist at the beginning of the study. After using the regression model to control for the confounding variables statistically, the results change dramatically.

Adjusted results

Of the 15 supplements that the study tracked in the observational study, researchers found consuming seven of these supplements were linked to a statistically significant INCREASE in death risk ( p-value < 0.05): multivitamins (increase in death risk 2.4%), vitamin B6 (4.1%), iron (3.9%), folic acid (5.9%), zinc (3.0%), magnesium (3.6%), and copper (18.0%). Only calcium was associated with a statistically significant reduction in death risk of 3.8%.

In short, the raw results suggest that those who consume supplements either have the same or lower death risks than non-consumers. However, these results do not account for the multitude of healthier habits and attributes in the group that uses supplements.

In fact, these confounders seem to produce most of the apparent benefits in the raw results because, after you statistically control the effects of these confounding variables, the results worsen for those who consume vitamin supplements. The adjusted results indicate that most vitamin supplements actually increase your death risk!

This research illustrates the differences between an observational study vs experiment. Namely how the pre-existing differences between the groups allow confounders to bias the raw results, making the vitamin consumption outcomes look better than they really are.

In conclusion, if you can’t randomly assign subjects to the experimental groups, an observational study might be right for you. However, be aware that you’ll need to identify, measure, and account for confounding variables in your experimental design.

Jaakko Mursu, PhD; Kim Robien, PhD; Lisa J. Harnack, DrPH, MPH; Kyong Park, PhD; David R. Jacobs Jr, PhD; Dietary Supplements and Mortality Rate in Older Women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study ; Arch Intern Med . 2011;171(18):1625-1633.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

December 30, 2023 at 5:05 am

I see, but our professor required us to indicate what year it was put into the article. May you tell me what year was this published originally? <3

December 30, 2023 at 3:40 pm

December 29, 2023 at 10:46 am

Hi, may I use your article as a citation for my thesis paper? If so, may I know the exact date you published this article? Thank you!

December 29, 2023 at 2:13 pm

Definitely feel free to cite this article! 🙂

When citing online resources, you typically use an “Accessed” date rather than a publication date because online content can change over time. For more information, read Purdue University’s Citing Electronic Resources .

November 18, 2021 at 10:09 pm

Love your content and has been very helpful!

Can you please advise the question below using an observational data set:

I have three years of observational GPS data collected on athletes (2019/2020/2021). Approximately 14-15 athletes per game and 8 games per year. The GPS software outputs 50+ variables for each athlete in each game, which we have narrowed down to 16 variables of interest from previous research.

2 factors 1) Period (first half, second half, and whole game), 2) Position (two groups with three subgroups in each – forwards (group 1, group 2, group 3) and backs (group 1, group 2, group 3))

16 variables of interest – all numerical and scale variables. Some of these are correlated, but not all.

My understanding is that I can use a oneway ANOVA for each year on it’s own, using one factor at a time (period or position) with post hoc analysis. This is fine, if data meets assumptions and is normally distributed. This tells me any significant interactions between variables of interest with chosen factor. For example, with position factor, do forwards in group 1 cover more total running distance than forwards in group 2 or backs in group 3.

However, I want to go deeper with my analysis. If I want to see if forwards in group 1 cover more total running distance in period 1 than backs in group 3 in the same period, I need an additional factor and the oneway ANOVA does not suit. Therefore I can use a twoway ANOVA instead of 2 oneway ANOVA’s and that solves the issue, correct?

This is complicated further by looking to compare 2019 to 2020 or 2019 to 2021 to identify changes over time, which would introduce a third independent variable.

I believe this would require a threeway ANOVA for this observational data set. 3 factors – Position, Period, and Year?

Are there any issues or concerns you see at first glance?

I appreciate your time and consideration.

April 12, 2021 at 2:02 pm

Could an observational study use a correlational design.

e.g. measuring effects of two variables on happiness, if you’re not intervening.

April 13, 2021 at 12:14 am

Typically, with observational studies, you’d want to include potential confounders, etc. Consequently, I’ve seen regression analysis used more frequently for observational studies to be able to control for other things because you’re not using randomization. You could use correlation to observe the relationship. However, you wouldn’t be controlling for potential confounding variables. Just something to consider.

April 11, 2021 at 1:28 pm

Hi, If I am to administer moderate doses of coffee for a hypothetical experiment, does it raise ethical concerns? Can I use random assignment for it?

April 11, 2021 at 4:06 pm

I don’t see any inherent ethical problems here as long as you describe the participant’s experience in the experiment including the coffee consumption. They key with human subjects is “informed consent.” They’re agreeing to participate based on a full and accurate understanding of what participation involves. Additionally, you as a researcher, understand the process well enough to be able to ensure their safety.

In your study, as long as subject know they’ll be drinking coffee and agree to that, I don’t see a problem. It’s a proven safe substance for the vast majority of people. If potential subjects are aware of the need to consume coffee, they can determine whether they are ok with that before agreeing to participate.

June 17, 2019 at 4:51 am

Really great article which explains observational and experimental study very well. It presents broad picture with the case study which helped a lot in understanding the core concepts. Thanks

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

What is Observational Study Design and Types

- 4 minute read

Table of Contents

Most people think of a traditional experimental design when they consider research and published research papers. There is, however, a type of research that is more observational in nature, and it is appropriately referred to as “observational studies.”

There are many valuable reasons to utilize an observational study design. But, just as in research experimental design, different methods can be used when you’re considering this type of study. In this article, we’ll look at the advantages and disadvantages of an observational study design, as well as the 3 types of observational studies.

What is Observational Study Design?

An observational study is when researchers are looking at the effect of some type of intervention, risk, a diagnostic test or treatment, without trying to manipulate who is, or who isn’t, exposed to it.

This differs from an experimental study, where the scientists are manipulating who is exposed to the treatment, intervention, etc., by having a control group, or those who are not exposed, and an experimental group, or those who are exposed to the intervention, treatment, etc. In the best studies, the groups are randomized, or chosen by chance.

Any evidence derived from systematic reviews is considered the best in the hierarchy of evidence, which considers which studies are deemed the most reliable. Next would be any evidence that comes from randomized controlled trials. Cohort studies and case studies follow, in that order.

Cohort studies and case studies are considered observational in design, whereas the randomized controlled trial would be an experimental study.

Let’s take a closer look at the different types of observational study design.

The 3 types of Observational Studies

The different types of observational studies are used for different reasons. Selecting the best type for your research is critical to a successful outcome. One of the main reasons observational studies are used is when a randomized experiment would be considered unethical. For example, a life-saving medication used in a public health emergency. They are also used when looking at aetiology, or the cause of a condition or disease, as well as the treatment of rare conditions.

Case Control Observational Study

Researchers in case control studies identify individuals with an existing health issue or condition, or “cases,” along with a similar group without the condition, or “controls.” These two groups are then compared to identify predictors and outcomes. This type of study is helpful to generate a hypothesis that can then be researched.

Cohort Observational Study

This type of observational study is often used to help understand cause and effect. A cohort observational study looks at causes, incidence and prognosis, for example. A cohort is a group of people who are linked in a particular way, for example, a birth cohort would include people who were born within a specific period of time. Scientists might compare what happens to the members of the cohort who have been exposed to some variable to what occurs with members of the cohort who haven’t been exposed.

Cross Sectional Observational Study

Unlike a cohort observational study, a cross sectional observational study does not explore cause and effect, but instead looks at prevalence. Here you would look at data from a particular group at one very specific period of time. Researchers would simply observe and record information about something present in the population, without manipulating any variables or interventions. These types of studies are commonly used in psychology, education and social science.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Observational Study Design

Observational study designs have the distinct advantage of allowing researchers to explore answers to questions where a randomized controlled trial, or RCT, would be unethical. Additionally, if the study is focused on a rare condition, studying existing cases as compared to non-affected individuals might be the most effective way to identify possible causes of the condition. Likewise, if very little is known about a condition or circumstance, a cohort study would be a good study design choice.

A primary advantage to the observational study design is that they can generally be completed quickly and inexpensively. A RCT can take years before the data is compiled and available. RCTs are more complex and involved, requiring many more logistics and details to iron out, whereas an observational study can be more easily designed and completed.

The main disadvantage of observational study designs is that they’re more open to dispute than an RCT. Of particular concern would be confounding biases. This is when a cohort might share other characteristics that affect the outcome versus the outcome stated in the study. An example would be that people who practice good sleeping habits have less heart disease. But, maybe those who practice effective sleeping habits also, in general, eat better and exercise more.

Language Editing Plus Service

Need help with your research writing? With our Language Editing Plus service , we’ll help you improve the flow and writing of your paper, including UNLIMITED editing support. Use the simulator below to check the price for your manuscript, using the total number of words of the document.

Clinical Questions: PICO and PEO Research

Paper Retraction: Meaning and Main Reasons

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Privacy Policy

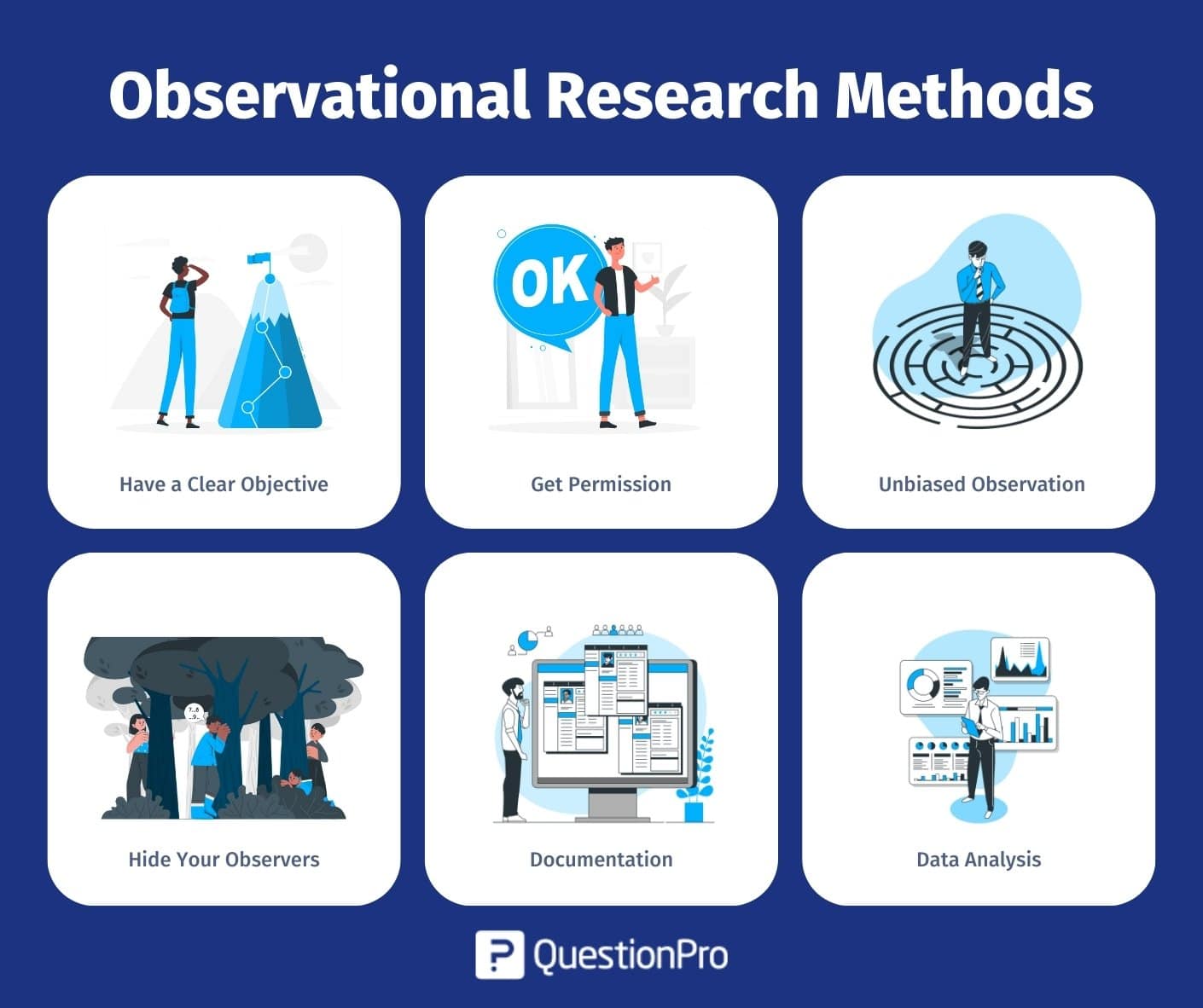

Home » Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Table of Contents

Observational Research

Definition:

Observational research is a type of research method where the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment. In other words, the researcher does not intervene or manipulate any variables but simply observes and describes what is happening.

Observation

Observation is the process of collecting and recording data by observing and noting events, behaviors, or phenomena in a systematic and objective manner. It is a fundamental method used in research, scientific inquiry, and everyday life to gain an understanding of the world around us.

Types of Observational Research

Observational research can be categorized into different types based on the level of control and the degree of involvement of the researcher in the study. Some of the common types of observational research are:

Naturalistic Observation

In naturalistic observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of individuals or groups in their natural environment without any interference or manipulation of variables.

Controlled Observation

In controlled observation, the researcher controls the environment in which the observation is taking place. This type of observation is often used in laboratory settings.

Participant Observation

In participant observation, the researcher becomes an active participant in the group or situation being observed. The researcher may interact with the individuals being observed and gather data on their behavior, attitudes, and experiences.

Structured Observation

In structured observation, the researcher defines a set of behaviors or events to be observed and records their occurrence.

Unstructured Observation

In unstructured observation, the researcher observes and records any behaviors or events that occur without predetermined categories.

Cross-Sectional Observation

In cross-sectional observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of different individuals or groups at a single point in time.

Longitudinal Observation

In longitudinal observation, the researcher observes and records the behavior of the same individuals or groups over an extended period of time.

Data Collection Methods

Observational research uses various data collection methods to gather information about the behaviors and experiences of individuals or groups being observed. Some common data collection methods used in observational research include:

Field Notes

This method involves recording detailed notes of the observed behavior, events, and interactions. These notes are usually written in real-time during the observation process.

Audio and Video Recordings

Audio and video recordings can be used to capture the observed behavior and interactions. These recordings can be later analyzed to extract relevant information.

Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires can be used to gather additional information from the individuals or groups being observed. This method can be used to validate or supplement the observational data.

Time Sampling

This method involves taking a snapshot of the observed behavior at pre-determined time intervals. This method helps to identify the frequency and duration of the observed behavior.

Event Sampling

This method involves recording specific events or behaviors that are of interest to the researcher. This method helps to provide detailed information about specific behaviors or events.

Checklists and Rating Scales

Checklists and rating scales can be used to record the occurrence and frequency of specific behaviors or events. This method helps to simplify and standardize the data collection process.

Observational Data Analysis Methods

Observational Data Analysis Methods are:

Descriptive Statistics

This method involves using statistical techniques such as frequency distributions, means, and standard deviations to summarize the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis involves identifying patterns and themes in the observed behaviors or interactions. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves categorizing and counting the occurrences of specific behaviors or events. This analysis can be done manually or with the help of software tools.

Time-series Analysis

Time-series analysis involves analyzing the changes in behavior or interactions over time. This analysis can help identify trends and patterns in the observed data.

Inter-observer Reliability Analysis

Inter-observer reliability analysis involves comparing the observations made by multiple observers to ensure the consistency and reliability of the data.

Multivariate Analysis

Multivariate analysis involves analyzing multiple variables simultaneously to identify the relationships between the observed behaviors, events, or interactions.

Event Coding

This method involves coding observed behaviors or events into specific categories and then analyzing the frequency and duration of each category.

Cluster Analysis

Cluster analysis involves grouping similar behaviors or events into clusters based on their characteristics or patterns.

Latent Class Analysis

Latent class analysis involves identifying subgroups of individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors or interactions.

Social network Analysis

Social network analysis involves mapping the social relationships and interactions between individuals or groups based on their observed behaviors.

The choice of data analysis method depends on the research question, the type of data collected, and the available resources. Researchers should choose the appropriate method that best fits their research question and objectives. It is also important to ensure the validity and reliability of the data analysis by using appropriate statistical tests and measures.

Applications of Observational Research

Observational research is a versatile research method that can be used in a variety of fields to explore and understand human behavior, attitudes, and preferences. Here are some common applications of observational research:

- Psychology : Observational research is commonly used in psychology to study human behavior in natural settings. This can include observing children at play to understand their social development or observing people’s reactions to stress to better understand how stress affects behavior.

- Marketing : Observational research is used in marketing to understand consumer behavior and preferences. This can include observing shoppers in stores to understand how they make purchase decisions or observing how people interact with advertisements to determine their effectiveness.

- Education : Observational research is used in education to study teaching and learning in natural settings. This can include observing classrooms to understand how teachers interact with students or observing students to understand how they learn.

- Anthropology : Observational research is commonly used in anthropology to understand cultural practices and beliefs. This can include observing people’s daily routines to understand their culture or observing rituals and ceremonies to better understand their significance.

- Healthcare : Observational research is used in healthcare to understand patient behavior and preferences. This can include observing patients in hospitals to understand how they interact with healthcare professionals or observing patients with chronic illnesses to better understand their daily routines and needs.

- Sociology : Observational research is used in sociology to understand social interactions and relationships. This can include observing people in public spaces to understand how they interact with others or observing groups to understand how they function.

- Ecology : Observational research is used in ecology to understand the behavior and interactions of animals and plants in their natural habitats. This can include observing animal behavior to understand their social structures or observing plant growth to understand their response to environmental factors.

- Criminology : Observational research is used in criminology to understand criminal behavior and the factors that contribute to it. This can include observing criminal activity in a particular area to identify patterns or observing the behavior of inmates to understand their experience in the criminal justice system.

Observational Research Examples

Here are some real-time observational research examples:

- A researcher observes and records the behaviors of a group of children on a playground to study their social interactions and play patterns.

- A researcher observes the buying behaviors of customers in a retail store to study the impact of store layout and product placement on purchase decisions.

- A researcher observes the behavior of drivers at a busy intersection to study the effectiveness of traffic signs and signals.

- A researcher observes the behavior of patients in a hospital to study the impact of staff communication and interaction on patient satisfaction and recovery.

- A researcher observes the behavior of employees in a workplace to study the impact of the work environment on productivity and job satisfaction.

- A researcher observes the behavior of shoppers in a mall to study the impact of music and lighting on consumer behavior.

- A researcher observes the behavior of animals in their natural habitat to study their social and feeding behaviors.

- A researcher observes the behavior of students in a classroom to study the effectiveness of teaching methods and student engagement.

- A researcher observes the behavior of pedestrians and cyclists on a city street to study the impact of infrastructure and traffic regulations on safety.

How to Conduct Observational Research

Here are some general steps for conducting Observational Research:

- Define the Research Question: Determine the research question and objectives to guide the observational research study. The research question should be specific, clear, and relevant to the area of study.

- Choose the appropriate observational method: Choose the appropriate observational method based on the research question, the type of data required, and the available resources.

- Plan the observation: Plan the observation by selecting the observation location, duration, and sampling technique. Identify the population or sample to be observed and the characteristics to be recorded.

- Train observers: Train the observers on the observational method, data collection tools, and techniques. Ensure that the observers understand the research question and objectives and can accurately record the observed behaviors or events.

- Conduct the observation : Conduct the observation by recording the observed behaviors or events using the data collection tools and techniques. Ensure that the observation is conducted in a consistent and unbiased manner.

- Analyze the data: Analyze the observed data using appropriate data analysis methods such as descriptive statistics, qualitative analysis, or content analysis. Validate the data by checking the inter-observer reliability and conducting statistical tests.

- Interpret the results: Interpret the results by answering the research question and objectives. Identify the patterns, trends, or relationships in the observed data and draw conclusions based on the analysis.

- Report the findings: Report the findings in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate visual aids and tables. Discuss the implications of the results and the limitations of the study.

When to use Observational Research

Here are some situations where observational research can be useful:

- Exploratory Research: Observational research can be used in exploratory studies to gain insights into new phenomena or areas of interest.

- Hypothesis Generation: Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses about the relationships between variables, which can be tested using experimental research.

- Naturalistic Settings: Observational research is useful in naturalistic settings where it is difficult or unethical to manipulate the environment or variables.

- Human Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying human behavior, such as social interactions, decision-making, and communication patterns.

- Animal Behavior: Observational research is useful in studying animal behavior in their natural habitats, such as social and feeding behaviors.

- Longitudinal Studies: Observational research can be used in longitudinal studies to observe changes in behavior over time.

- Ethical Considerations: Observational research can be used in situations where manipulating the environment or variables would be unethical or impractical.

Purpose of Observational Research

Observational research is a method of collecting and analyzing data by observing individuals or phenomena in their natural settings, without manipulating them in any way. The purpose of observational research is to gain insights into human behavior, attitudes, and preferences, as well as to identify patterns, trends, and relationships that may exist between variables.

The primary purpose of observational research is to generate hypotheses that can be tested through more rigorous experimental methods. By observing behavior and identifying patterns, researchers can develop a better understanding of the factors that influence human behavior, and use this knowledge to design experiments that test specific hypotheses.

Observational research is also used to generate descriptive data about a population or phenomenon. For example, an observational study of shoppers in a grocery store might reveal that women are more likely than men to buy organic produce. This type of information can be useful for marketers or policy-makers who want to understand consumer preferences and behavior.

In addition, observational research can be used to monitor changes over time. By observing behavior at different points in time, researchers can identify trends and changes that may be indicative of broader social or cultural shifts.

Overall, the purpose of observational research is to provide insights into human behavior and to generate hypotheses that can be tested through further research.

Advantages of Observational Research

There are several advantages to using observational research in different fields, including:

- Naturalistic observation: Observational research allows researchers to observe behavior in a naturalistic setting, which means that people are observed in their natural environment without the constraints of a laboratory. This helps to ensure that the behavior observed is more representative of the real-world situation.

- Unobtrusive : Observational research is often unobtrusive, which means that the researcher does not interfere with the behavior being observed. This can reduce the likelihood of the research being affected by the observer’s presence or the Hawthorne effect, where people modify their behavior when they know they are being observed.

- Cost-effective : Observational research can be less expensive than other research methods, such as experiments or surveys. Researchers do not need to recruit participants or pay for expensive equipment, making it a more cost-effective research method.

- Flexibility: Observational research is a flexible research method that can be used in a variety of settings and for a range of research questions. Observational research can be used to generate hypotheses, to collect data on behavior, or to monitor changes over time.

- Rich data : Observational research provides rich data that can be analyzed to identify patterns and relationships between variables. It can also provide context for behaviors, helping to explain why people behave in a certain way.

- Validity : Observational research can provide high levels of validity, meaning that the results accurately reflect the behavior being studied. This is because the behavior is being observed in a natural setting without interference from the researcher.

Disadvantages of Observational Research

While observational research has many advantages, it also has some limitations and disadvantages. Here are some of the disadvantages of observational research:

- Observer bias: Observational research is prone to observer bias, which is when the observer’s own beliefs and assumptions affect the way they interpret and record behavior. This can lead to inaccurate or unreliable data.

- Limited generalizability: The behavior observed in a specific setting may not be representative of the behavior in other settings. This can limit the generalizability of the findings from observational research.

- Difficulty in establishing causality: Observational research is often correlational, which means that it identifies relationships between variables but does not establish causality. This can make it difficult to determine if a particular behavior is causing an outcome or if the relationship is due to other factors.

- Ethical concerns: Observational research can raise ethical concerns if the participants being observed are unaware that they are being observed or if the observations invade their privacy.

- Time-consuming: Observational research can be time-consuming, especially if the behavior being observed is infrequent or occurs over a long period of time. This can make it difficult to collect enough data to draw valid conclusions.

- Difficulty in measuring internal processes: Observational research may not be effective in measuring internal processes, such as thoughts, feelings, and attitudes. This can limit the ability to understand the reasons behind behavior.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

One-to-One Interview – Methods and Guide

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

What Are Observational Studies?

Observational studies are research studies in which researchers collect information from participants or look at data that was already collected.

In observational studies, researchers follow groups of people over a period of time. Depending on the study, groups may include healthy people, people with cancer, or people who are at high risk for developing cancer, such as those with a family history.

How observational studies help cancer research

Observational studies can help researchers learn more about cancer and suggest paths for future research that may lead to insights such as:

- how specific cancers form, grow, and spread

- genes that cause cancer to develop at a high rate within certain groups

- exposures or behaviors that may increase the risk of cancer

- clues to help prevent cancer

- clues that lead to new treatments

- patterns and trends of new cancer cases

- the experiences of people who have had cancer in the past

Types of observational studies

There are different types of observational studies. Two examples include natural history and longitudinal studies.

Natural history studies look at certain conditions in people with cancer or people who are at a high risk of developing cancer. Researchers often collect information about a person’s and their family’s medical history, as well as blood, saliva, and tumor samples that may be studied to learn more about how cancer develops or how it responds to treatment.

Longitudinal studies gather data on people over time, often to see whether those with different exposures have different cancer outcomes. Examples include those with different kinds of diets, smoking history, or other traits.

What to expect

Find Observation Studies >

View a studies that are looking for people now.

What you do as part of an observational study depends on the study. In some studies, you may be asked to fill out surveys or questionnaires. Researchers may ask about your medical history and that of your family. They might ask you to provide tissue samples, such as blood, saliva, or—if you have cancer—your tumor. Some studies may require your medical records. For some studies you might be asked to come in for an in-person visit with the research team.

Depending on the study, you might provide samples and information just once, or many times over the course of the study.

Possible risks and benefits

There are few risks to taking part in an observational research study. One possible risk is the accidental release of information from your health records. To prevent this from happening, there are security measures in place to protect your privacy. A benefit of taking part in an observational study is knowing that you will help doctors learn more about cancer. These studies help create a foundation that can lead to further research that may help people with cancer in the future. Or they might help people in the future avoid cancer.

Your rights

Before you join a study, the research team will make sure you understand:

- why the study is being done

- what will happen during the study

- how it may affect your daily life

Once you understand the study and decide to take part, you will be asked to sign a consent form. But even after you sign the form, you can change your mind and leave the study at any time.

Costs and expenses

Most observational studies are free to those who take part. As you think about joining an observational study, be sure to ask the study team about costs.

Observational Studies

- © 2002

- Latest edition

- Paul R. Rosenbaum 0

Department of Statistics, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Includes supplementary material: sn.pub/extras

Part of the book series: Springer Series in Statistics (SSS)

46k Accesses

1961 Citations

18 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

Two Simple Models for Observational Studies

Opportunities, devices, and instruments, causal inference in randomized experiments.

- Sensitivity

- Treatment Effects

Table of contents (12 chapters)

Front matter.

Paul R. Rosenbaum

Randomized Experiments

Overt bias in observational studies, sensitivity to hidden bias, models for treatment effects, known effects, multiple reference groups in case-referent studies, multiple control groups, coherence and focused hypotheses, constructing matched sets and strata, planning an observational study, some strategic issues, back matter, authors and affiliations, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Observational Studies

Authors : Paul R. Rosenbaum

Series Title : Springer Series in Statistics

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-3692-2

Publisher : Springer New York, NY

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Copyright Information : Springer Science+Business Media New York 2002

Hardcover ISBN : 978-0-387-98967-9 Published: 08 January 2002

Softcover ISBN : 978-1-4419-3191-7 Published: 01 December 2010

eBook ISBN : 978-1-4757-3692-2 Published: 17 April 2013

Series ISSN : 0172-7397

Series E-ISSN : 2197-568X

Edition Number : 2

Number of Pages : XIV, 377

Number of Illustrations : 6 b/w illustrations

Topics : Statistical Theory and Methods , Statistics for Life Sciences, Medicine, Health Sciences , Statistics for Social Sciences, Humanities, Law , Statistics for Business, Management, Economics, Finance, Insurance

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

10 Observational Research Examples

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Observational research involves observing the actions of people or animals, usually in their natural environments.

For example, Jane Goodall famously observed chimpanzees in the wild and reported on their group behaviors. Similarly, many educational researchers will conduct observations in classrooms to gain insights into how children learn.

Examples of Observational Research

1. jane goodall’s research.

Jane Goodall is famous for her discovery that chimpanzees use tools. It is one of the most remarkable findings in psychology and anthropology .

Her primary method of study involved simply entering the natural habitat of her research subjects, sitting down with pencil and paper, and making detailed notes of what she observed.

Those observations were later organized and transformed into research papers that provided the world with amazing insights into animal behavior.

When she first discovered that chimpanzees use twigs to “fish” for termites, it was absolutely stunning. The renowned Louis Leakey proclaimed: “we must now redefine tool, redefine man, or accept chimps as humans.”

2. Linguistic Development of Children

Answering a question like, “how do children learn to speak,” can only be answered by observing young children at home.

By the time kids get to first grade, their language skills have already become well-developed, with a vocabulary of thousands of words and the ability to use relatively complex sentences.

Therefore, a researcher has to conduct their study in the child’s home environment. This typically involves having a trained data collector sit in a corner of a room and take detailed notes about what and how parents speak to their child.

Those observations are later classified in a way that they can be converted into quantifiable measures for statistical analysis.

For example, the data might be coded in terms of how many words the parents spoke, degree of sentence complexity, or emotional dynamic of being encouraging or critical. When the data is analyzed, it might reveal how patterns of parental comments are linked to the child’s level of linguistic development.

Related Article: 15 Action Research Examples

3. Consumer Product Design

Before Apple releases a new product to the market, they conduct extensive analyses of how the product will be perceived and used by consumers.

The company wants to know what kind of experience the consumer will have when using the product. Is the interface user-friendly and smooth? Does it fit comfortably in a person’s hand?

Is the overall experience pleasant?

So, the company will arrange for groups of prospective customers come to the lab and simply use the next iteration of one of their great products. That lab will absolutely contain a two-way mirror and a team of trained observers sitting behind it, taking detailed notes of what the test groups are doing. The groups might even be video recorded so their behavior can be observed again and again.

That will be followed by a focus group discussion , maybe a survey or two, and possibly some one-on-one interviews.

4. Satellite Images of Walmart

Observational research can even make some people millions of dollars. For example, a report by NPR describes how stock market analysts observe Walmart parking lots to predict the company’s earnings.

The analysts purchase satellite images of selected parking lots across the country, maybe even worldwide. That data is combined with what they know about customer purchasing habits, broken down by time of day and geographic region.

Over time, a detailed set of calculations are performed that allows the analysts to predict the company’s earnings with a remarkable degree of accuracy .

This kind of observational research can result in substantial profits.

5. Spying on Farms

Similar to the example above, observational research can also be implemented to study agriculture and farming.

By using infrared imaging software from satellites, some companies can observe crops across the globe. The images provide measures of chlorophyll absorption and moisture content, which can then be used to predict yields. Those images also allow analysts to simply count the number of acres being planted for specific crops across the globe.

In commodities such as wheat and corn, that prediction can lead to huge profits in the futures markets.

It’s an interesting application of observational research with serious monetary implications.

6. Decision-making Group Dynamics

When large corporations make big decisions, it can have serious consequences to the company’s profitability, or even survival.

Therefore, having a deep understanding of decision-making processes is essential. Although most of us think that we are quite rational in how we process information and formulate a solution, as it turns out, that’s not entirely true.

Decades of psychological research has focused on the function of statements that people make to each other during meetings. For example, there are task-masters, harmonizers, jokers, and others that are not involved at all.

A typical study involves having professional, trained observers watch a meeting transpire, either from a two-way mirror, by sitting-in on the meeting at the side, or observing through CCTV.

By tracking who says what to whom, and the type of statements being made, researchers can identify weaknesses and inefficiencies in how a particular group engages the decision-making process.

See More: Decision-Making Examples

7. Case Studies

A case study is an in-depth examination of one particular person. It is a form of observational research that involves the researcher spending a great deal of time with a single individual to gain a very detailed understanding of their behavior.

The researcher may take extensive notes, conduct interviews with the individual, or take video recordings of behavior for further study.

Case studies give a level of detailed information that is not available when studying large groups of people. That level of detail can often provide insights into a phenomenon that could lead to the development of a new theory or help a researcher identify new areas of research.

Researchers sometimes have no choice but to conduct a case study in situations in which the phenomenon under study is “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017). Because the condition is so uncommon, it is impossible to find a large enough sample of cases to study with quantitative methods.

Go Deeper: Pros and Cons of Case Study Research

8. Infant Attachment

One of the first studies on infant attachment utilized an observational research methodology . Mary Ainsworth went to Uganda in 1954 to study maternal practices and mother/infant bonding.

Ainsworth visited the homes of 26 families on a bi-monthly basis for 2 years, taking detailed notes and interviewing the mothers regarding their parenting practices.

Her notes were then turned into academic papers and formed the basis for the Strange Situations test that she developed for the laboratory setting.

The Strange Situations test consists of 8 situations, each one lasting no more than a few minutes. Trained observers are stationed behind a two-way mirror and have been trained to make systematic observations of the baby’s actions in each situation.

9. Ethnographic Research

Ethnography is a type of observational research where the researcher becomes part of a particular group or society.

The researcher’s role as data collector is hidden and they attempt to immerse themselves in the community as a regular member of the group.

By being a part of the group and keeping one’s purpose hidden, the researcher can observe the natural behavior of the members up-close. The group will behave as they would naturally and treat the researcher as if they were just another member. This can lead to insights into the group dynamics , beliefs, customs and rituals that could never be studied otherwise.

10. Time and Motion Studies

Time and motion studies involve observing work processes in the work environment. The goal is to make procedures more efficient, which can involve reducing the number of movements needed to complete a task.

Reducing the movements necessary to complete a task increases efficiency, and therefore improves productivity. A time and motion study can also identify safety issues that may cause harm to workers, and thereby help create a safer work environment.

The two most famous early pioneers of this type of observational research are Frank and Lillian Gilbreth.

Lilian was a psychologist that began to study the bricklayers of her husband Frank’s construction company. Together, they figured out a way to reduce the number of movements needed to lay bricks from 18 to 4 (see original video footage here ).

The couple became quite famous for their work during the industrial revolution and

Lillian became the only psychologist to appear on a postage stamp (in 1884).

Why do Observational Research?

Psychologists and anthropologists employ this methodology because: