Film Studies

- Introduction

- Basic information on film

- Finding a specific film title

- Readings on streaming video

- National cinemas This link opens in a new window

- Course guides for Film & Media Studies

- Starting your research ...

- Researching early films

- 1960's film history

- 1970's film history

- Books about film

- Film reviews

- Journals & magazines about film

- Feminist film theory

- Auteur theory

- Feminist film criticism

- Box office information

- Film audiences

- Mass media Industry

- Cinema Pressbooks from the Original Studio Collections

- Congressional Hearings & Communism

- Herrick Library Digital Collections

- Hollywood and the Production Code

- Media History Digital Library

- Moving Picture World

- African American diaspora

- Asian American diaspora

- Hispanic American diaspora

- Native American & Indigenous peoples diasporas

- Examples on film

- Film genres This link opens in a new window

- Film & society

- Screenwriting

- Shakespeare on film

- Color in film

- A short list of film festivals

- Film awards

- Internet resources

- Future of Media

- Back to Film & Media

- Scholarly communication This link opens in a new window

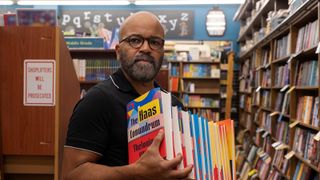

Subject Librarian

Finding scholarly articles and journal title(s)

Articles and other writings about movies can be found in many publications. Our collection has one journal that looks exclusively at film adaptations, Adaptation . You can use Film & Television Literature Index or the Summon box below to find articles.

Citing and Tracking Your Bibliographic References

Use this guide to help you learn how to correctly cite and keep track of the references you find for your research.

Keeping up with the journal literature

You can get the app from the App Store or Google Play.

Don't own or use a mobile device? You can still use BrowZine! It's now available in a web version. You can get to it here . The web version works the same way as the app version. Find the journals you like, create a custom Bookshelf, get ToCs and read the articles you want.

A definition for 'Adaptation'

A pre-existing work that has been made into a film. Adaptations are often of literary or theatrical works, but musical theatre, best-selling fiction and non-fiction, comic books, computer games , children’s toys, and so on have also been regularly adapted for the cinema. Adaptations of well-known literary and theatrical texts were common in the silent era ( see silent cinema ; costume drama ; epic film ; history film ) and have been a staple of virtually all national cinemas through the 20th and 21st centuries. Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories (1887–1927) have been adapted in a range of national contexts but probably the most adapted author is Shakespeare, whose plays have appeared in film form as a large-budget Hollywood musical ( West Side Story (Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise, US, 1961)), a historical epic set in feudal Japan ( Kumonosu-jo / Throne of Blood (Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1957)), a Bollywood musical ( Angoor (Gulzar, India, 1982)), and a children’s animation ( The Lion King (Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff, US, 1994)), to name but a few. Adaptations often sit within cycles associated with a particular time and place, as with the British heritage film in the 1980s ( see cycle ). It is claimed that adaptations account for up to 50 per cent of all Hollywood films and are consistently rated amongst the highest grossing at the box office , as aptly demonstrated by the commercial success of recent adaptations of the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Other varied US adaptations include: computer games ( Resident Evil (Paul W.S. Anderson, 2002)), graphic novels ( Ghost World (Terry Zwigoff, 2001)), comic books ( The Avengers (Joss Whedon, 2012)); see also cinematic universe ; superhero film ), and children’s toys ( Transformers: The Last Knight (Michael Bay, 2017)). A number of films also display a certain level of self-reflexivity regarding the process of adaptation, as can be seen in Adaptation (Spike Jonze, US, 2002) and The LEGO Movie (Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, 2012). A property ripe for adaptation is referred to as pre-sold ; older works in particular are attractive to film producers because they are often out of copyright ( see deal, the ).

Kuhn, A., & Westwell, G. (2020). " Adaptation ." In A Dictionary of Film Studies . Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 Feb. 2022

In the Library's collections

The following are useful subject headings for searching the online catalog. The books on adapting source materials for films are shelved in the call number range PN 1997.85 on Baker Level 4 .

- film adaptations

- fotonovelas

- motion picture authorship This is the subject heading used instead of "screenwriting." The books on screenwriting and screenwriters are shelved in the PN 1996 through PN 1997.85 on Baker Level 4 .

- motion picture plays technique

- shakespeare william 1564 1616 film adaptations This is an example subject search for adaptations for a specific author.

Introductory reading(s)

Selected book title(s)

Other library resource(s)

Most of these are resources for actual scripts.

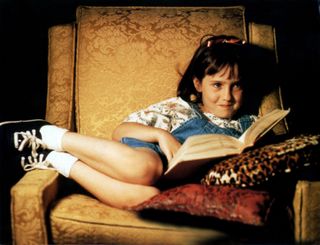

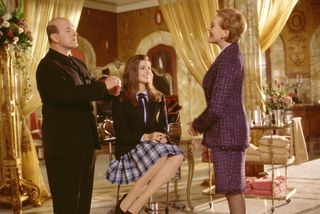

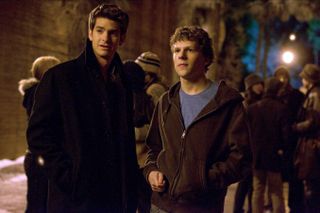

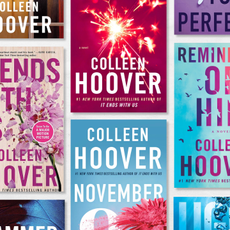

A short selection of adapted films

Here is a short list of adapted films located in the Jones Media Center or available through streaming. Find more film adaptations in the library's online catalog.

- << Previous: Screenwriting

- Next: Shakespeare on film >>

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2024 3:41 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.dartmouth.edu/filmstudies

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Adaptation

Introduction.

- Filmographies

- Bibliographies

- Literature versus Cinema

- Interart Analogies

- Medium-Specific Studies

- Case Studies of Classic Fiction

- Case Studies of Modern Fiction

- Theoretically Oriented Collections

- Thematically Oriented Collections

- Cultural Studies

- Around the World

- Painting, Performance, Television

- Convergence Culture

- Adaptation, Remediation, and Intermediality

- Translation

- Textual and Biological Adaptation

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- André Bazin

- Australian Cinema

- Dashiell Hammett

- David Cronenberg

- Documentary Film

- Douglas Sirk

- Erich Von Stroheim

- Film and Literature

- Francis Ford Coppola

- Game of Thrones

- Hou Hsiao-Hsien

- Icelandic Cinema

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- It Happened One Night

- Jean Renoir

- Lee Chang-dong

- Luchino Visconti

- Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Ridley Scott

- Robert Altman

- Robert Bresson

- Roger Corman

- Russian Cinema

- Sally Potter

- Shakespeare on Film

- Sidney Lumet

- Terry Gilliam

- The Coen Brothers

- The Godfather Trilogy

- The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

- The Wizard of Oz

- Wong Kar-wai

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- À bout de souffle

- Superhero Films

- Wim Wenders

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Adaptation by Thomas Leitch , Kyle Meikle LAST REVIEWED: 29 September 2014 LAST MODIFIED: 29 September 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0116

Studies of cinematic adaptations—films based, as the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences puts it, on material originally presented in another medium—are scarcely a century old. Even so, particular studies of adaptation, the process by which texts in a wide range of media are transformed into films (and more recently into other texts that are not necessarily films), cannot be properly understood without reference to the specific period they were produced in. Each generation of adaptation studies has produced its own principles and orthodoxies, typically by attacking the orthodoxies and principles of the preceding generation. Adaptation studies have regularly alternated between polemics that attacked earlier assumptions in the field and readings of individual adaptations that have explored the implications of these attacks and so implicitly established new orthodoxies. The earliest work on adaptation, from Vachel Lindsay’s The Art of the Moving Picture , first published in 1915, to André Bazin’s “Adaptation, or the Cinema as Digest,” first published in 1948, grapples with the general relationship between literature and cinema as presentational modes. The second phase, focusing mostly on adaptations of individual novels to films, follows George Bluestone’s highly influential 2003 study Novels into Film , originally published in 1957, in assuming a series of categorical distinctions between verbal and visual representational modes. Most studies of individual adaptations and their sources, and most textbooks on adaptation, have been produced under the influence of these assumptions. In this third phase, Robert Stam’s 2000 article “Beyond Fidelity: The Dialogics of Adaptation” rejects the binary distinctions between source texts and adaptations; Kamilla Elliott’s 2003 book Rethinking the Novel/Film Debate deconstructs the binary distinctions between verbal and visual texts; and Linda Hutcheon and Siobhan O’Flynn’s 2012 book A Theory of Adaptation emphasizes the continuities between texts that have been explicitly identified as adaptations and all other texts as intertextual palimpsests marked by traces of innumerable earlier texts. This third phase has generated most of the leading work on adaptation theory. An emerging fourth phase is heralded by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s 1999 study Remediation: Understanding New Media and Lev Manovich’s 2001 book The Language of New Media . Both are inspired by the rise of the digital media that establishes every reader as a potential writer. These analysts use a Wiki-based model of writing as community participation rather than individual creation to break down the distinction between reading and writing and recast adaptation as a quintessential instance of the incessant process of textual production. A leading tendency of this fourth phase has been to use methodologies developed for literature-to-film adaptation to analyze adaptations that range far outside literature and cinema.

General Resources

Earlier than any other area of cinema studies, adaptation began to generate a substantial body of resources specifically designed for teachers, students, and academic researchers. The dominance of the case study in the second phase of adaptation studies produced an especially comprehensive and wide-ranging series of literature-to-cinema filmographies, some aiming for exhaustiveness, others for greater selectivity and more extended analysis of particular novel-to-film or theater-to-film pairs. The prominence of college courses in film adaptation generated a number of textbooks focusing on cinematic adaptation, and later a series of essays considering the larger theoretical and pedagogical issues that were raised, or that could be raised, by focusing on adaptations.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Downton Abbey

- Dr. Strangelove

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Golden Girls, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latin American Cinema

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Cinema

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Television

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Tati, Jacques

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and Film

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yang, Edward

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.66.14.236]

- 185.66.14.236

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Introduction: the art of adaptation in film and video games.

We live in a world of adaptation, and a failure to study that world means we must ignore an increasingly important part of contemporary culture. —Dennis Cutchins ( 2018 )

Conflicts of Interest

- Barr, Matthew. 2020. The Force Is Strong with This One (but Not That One): What Makes a Successful Star Wars Video Game Adaptation? Arts 9: 131. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barr, Pippin. 2020. Film Adaptation as Experimental Game Design. Arts 9: 103. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Belau, Linda. 2021. Impossible Origins: Trauma Narrative and Cinematic Adaptation. Arts 10: 15. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cattrysse, Patrick. 2018. An Evolutionary View of Cultural Adaptation: Some Considerations. In The Routledge Companion to Adaptation . Edited by Dennis Cutchins, Katja Krebs and Eckart Voigts. New York: Routledge, pp. 27–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cutchins, Dennis. 2018. Introduction. In The Routledge Companion to Adaptation . Edited by Dennis Cutchins, Katja Krebs and Eckart Voigts. New York: Routledge, p. 3. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emig, Rainer. 2018. Adaptation and the Concept of the Original. In The Routledge Companion to Adaptation . Edited by Dennis Cutchins, Katja Krebs and Eckart Voigts. New York: Routledge, pp. 39–54. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freer, Scott. 2020. Remediating ‘Prufrock’. Arts 9: 104. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gawroński, Slawomir, and Kinga Bajorek. 2020. A Real Witcher—Slavic or Universal; from a Book, a Game or a TV Series? In the Circle of Multimedia Adaptations of a Fantasy Series of Novels “The Witcher” by A. Sapkowski. Arts 9: 102. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hiltunen, Kaisa, Heidi Björklund, Aino Nurmesjärvi, Jenna Purhonen, Minna Rainio, Nina Sääskilahti, and Antti Vallius. 2020. Tale(s) of the Forest—Re-Creation of a Primeval Forest in Three Environmental Narratives. Arts 9: 125. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hutcheon, Linda. 2004. On the Art of Adaptation. Daedalus 133: 108–11. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Landwehr, Margarete. 2020. Empathy and Community in the Age of Refugees: Petzold’s Radical Translation of Seghers’ Transit. Arts 9: 118. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mangiron, Carme. 2021. Found in Translation: Evolving Approaches for the Localization of Japanese Video Games. Arts 10: 9. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Moore, Kevin C. 2020. Readapting Pandemic Premediation and Propaganda: Soderbergh’s Contagion amid COVID-19. Arts 9: 112. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Novitz, Julian. 2020. ‘The Time Is Out of Joint’: Interactivity and Player Agency in Videogame Adaptations of Hamlet . Arts 9: 122. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sell, Mike. 2021. What Is a Videogame Movie? Arts 10: 24. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thomas, Christian. 2021a. Writing for Emotional Impact in Film and Video Games: Lessons in Character Development, Realism, and Interactivity from the Alien Media Franchise. Arts 10: 20. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Thomas, Christian. 2021b. Interview: Acclaimed Game Designer Ryan Kaufman Discusses Telltale Games, Star Wars , Harry Potter , and How Video Games Can Transform Us. Arts 10: 46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Wang, Zhuoyi. 2020. Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis. Arts 9: 78. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhu, Ping. 2020. From Patricide to Patrilineality: Adapting The Wandering Earth for the Big Screen. Arts 9: 94. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Thomas, C. Introduction: The Art of Adaptation in Film and Video Games. Arts 2022 , 11 , 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040071

Thomas C. Introduction: The Art of Adaptation in Film and Video Games. Arts . 2022; 11(4):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040071

Thomas, Christian. 2022. "Introduction: The Art of Adaptation in Film and Video Games" Arts 11, no. 4: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11040071

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

The Study of Historical Films as Adaptation: Some Critical Reflections

- First Online: 27 September 2018

Cite this chapter

- Patrick Cattrysse 4 , 5 , 6

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Adaptation and Visual Culture ((PSADVC))

624 Accesses

This chapter suggests that the study of historical film studies and literary film adaptations shows similarities, which warrant exchanging concepts and methods to benefit both disciplines. Hence, section “ Historical Film Studies: A Brief Introduction ” sketches a brief introduction to the field of historical film studies. Section “ The Adaptation as End-Product ” looks into how literary or historical film adaptations, understood as end-products, may involve highlighting or, rather, hiding adaptational tracks. Section “ Adaptation as a Process ” focuses on the adaptation process and discusses pros and cons of distinguishing between a selection policy and an actual adaptation policy. Finally, section “ Systemic Relations Between Process and End-Product ” discusses some research questions dealing with systemic relations that may obtain between the presentation and perception of a set of literary or historical film adaptations, understood as end-products, and features of their adaptational processes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Temporalities of Adaptation

Introduction: Adaptation’s Past, Adaptation’s Future

What Can Adaptation Studies Learn from Fan Studies?

Agger, Gunhild. “The Role of History in Bestseller and Blockbuster Culture.” Akademisk Kvarter , vol. 7, 2013: pp. 299–316.

Google Scholar

Alavi, Bettina, et al., eds. Zeitgeschichte - Medien - Historische Bildung . V&R Unipress, 2010.

Andrew, Dudley. Concepts in Film Theory . Oxford University Press, 1984.

———. “Adapting Cinema to History: A Revolution in the Making.” A Companion to Literature and Film , Blackwell, 2004: pp. 189–204.

Asheim, Lester E. From Book to Film: A Comparative Analysis of the Content of Selected Novels and the Motion Pictures Based Upon Them . University of Chicago, 1949.

———. “From Book to Film: Mass Appeals.” Hollywood Quarterly , vol. 5, 1951: pp. 334–349.

Article Google Scholar

———. “From Book to Film: Summary.” The Quarterly of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 6, 1952: pp. 258–273.

Blackburn, Simon. Truth: A Guide for the Perplexed . Penguin Books, 2006.

Boyd, Brian. On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition and Fiction . The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

Broich, Ulrich. “Formen Der Markierung von Intertextualität.” Intertextualität: Formen, Funktionen, Anglistische Fallstudien , Niemeyer Verlag, 1985: pp. 31–47.

Bushnell, William S. “Paying for the Damage: The Quiet American Revisited.” History & Film , vol. 36, no. 2, 2006: pp. 38–44.

Calhoun, Claudia. “The Story You Are About to Hear Is True”: Dragnet, Transmedia Storytelling, and the Power of the Postwar Police Procedural . Yale University, 2014.

Cameron, Kenneth M. America on Film: Hollywood and American History . Continuum, 1997.

Carroll, Noël. “On the Narrative Connection.” New Perspectives on Narrative Perspective , State University of New York Press, 2001: pp. 21–41.

Cattrysse, Patrick. “‘The Naked City’ and the Semi-Documentary.” Image-Reality-Spectator: Essays on Documentary Film and Television , ACCO, 1989: pp. 132–154.

———. L’Adaptation filmique de textes littéraires: Le film noir américain . Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1990, http://independent.academia.edu/CattryssePatrick/Books .

———. “Vertaling, Adaptatie en Intertekstualiteit.” Communicatie , vol. 21, no. 1, 1991: pp. 38–47.

———. “De Semi-Documentaire: Een Analyse in Termen van Normen en Systemen.” Communicatie , vol. 20, no. 3, 1991 [1990]: pp. 11–32.

———. Pour une théorie de l’adaptation filmique: Le film noir américain . Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 1992.

———. “Pour une Approche Intersystémique du Cinéma.” Towards a Pragmatics of the Audio-Visual: Theory and History , vol. 1, Nodus Publikationen, 1994: pp. 61–75.

———. “Simone Murray, The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation . Book Review.” Translation: A Transdisciplinary Journal , 2012, http://translation.fusp.it/reviews/the-adaptation-industry-the-cultural-economy-of-contemporary-literary-adaptation .

———. Descriptive Adaptation Studies: Epistemological and Methodological Issues . Garant Publishers, 2014.

———. “An Evolutionary View of Cultural Adaptation: Some Considerations.” The Routledge Companion to Adaptation , Routledge, 2018.

Chapman, Adam. Digital Games as History . Routledge, 2016.

Dagmar, Brunow. Remediating Transcultural Memory . Walter de Gruyter, 2015.

Davis, David. “Fictional Truth and Fictional Authors.” British Journal of Aesthetics , vol. 36, no. 1, 1996: pp. 43–55.

Deshpande, Anirudh. “Films as Historical Sources or Alternative History.” Economic and Political Weekly , vol. 39, no. 40, 2004: pp. 4455–4459.

Elliott, Andrew B. Remaking the Middle Ages: The Methods of Cinema and History in Portraying the Medieval World . McFarland & Co., 2011.

Even-Zohar, Itamar. “The Position of Translated Literature Within the Literary Polysystem.” Literature and Translation: New Perspectives in Literary Studies , ACCO, 1978: pp. 117–127.

Falbe-Hansen, Rasmus. “The Filmmaker as Historian.” P.O.V.A Danish Journal of Film Studies , vol. 16, 2003: pp. 109–117.

García-Carpintero, Manuel. “Fictional Entities, Theoretical Models and Figurative Truth.” Beyond Mimesis and Convention: Representation in Art and Science , Springer, 2010: pp. 139–168.

Gazzaniga, Michael S. Who’s in Charge? Free Will and the Science of the Brain . Harper Collins Books, 2011.

Gottschall, Jonathan. The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human . Mariner Books Edition, 2013.

Greene, Graham. The Quiet American . Vintage Books, 1955.

———. Ways of Escape . Vintage Books, 2002.

Guynn, William. Writing History in Film . Routledge, 2006.

Herman, David. Story Logic: Problems and Possibilities of Narrative . University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Hughes-Warrington, Marnie. History Goes to the Movies: Studying History on Film . New Edition, Routledge, 2006.

Book Google Scholar

———, ed. The History on Film Reader . Routledge, 2009.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow . Penguin Books, 2011.

Kroon, Frederick. “The Fiction of Creationism.” Truth in Fiction . De Gruyter, 2013: pp. 203–222.

Kroon, Frederick, and Alberto Voltolini. “Fiction.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition), 2011, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/fiction .

Krutnik, Frank. In a Lonely Street: Film Noir, Genre, Masculinity . Routledge, 1991.

Laass, Eva. Broken Taboos, Subjective Truths: Forms and Functions of Unreliable Narration in Contemporary American Cinema—A Contribution to Film Narratology . Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2008.

Lafferty, William. “A Reappraisal of the Semi-Documentary in Hollywood, 1945–1948.” Velvet Light Trap , vol. 20, 1983: pp. 22–26.

Leitch, Thomas. Film Adaptation & Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to the Passion of the Christ . John Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Lorenz, Chris. De Constructie van het Verleden: Een Inleiding in de Theorie van de Geschiedenis . Meppel, 1987.

Mico, Ted, et al., eds. Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies . Henry Holt & Co., 1996.

Minda, John Paul. The Psychology of Thinking: Reasoning, Decision-Making & Problem-Solving . Sage, 2015.

Murray, Simone. The Adaptation Industry: The Cultural Economy of Contemporary Literary Adaptation . Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.

Pauleit, Winfried, et al., eds. Film und Geschichte: Produktion und Erfahrung von Geschichte Durch Bewegtbild und Ton . Bertz-Fischer Verlag, 2015.

Phelan, James. Living to Tell About It: A Rhetoric of Ethics and Character Narration . Cornell University Press, 2005.

Phelan, James, and Mary Patricia Martin. “The Lessons of ‘Weymouth’: Homodiegesis, Unreliability, Ethics, and The Remains of the Day .” Narratologies: New Perspectives on Narrative Analysis , Ohio State University Press, 1999: pp. 88–109.

Popper, Karl R. Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach . Clarendon Press, 1972.

Raw, Laurence, and Defne Ersin Tutan, eds. The Adaptation of History: Essays on Ways of Telling the Past . McFarland, 2013.

Rosenstone, Robert A. Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History . Harvard University Press, 1995.

———. History on Film/Film on History . Pearson Education Ltd., 2006.

———. “Historian in Spite of Myself.” Rethinking History: The Journal of Theory and Practice , vol. 11, no. 4, 2007: pp. 589–595.

———. History on Film/Film on History , 2nd ed. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013.

Schaeffer, Jean-Marie. Pourquoi la Fiction? Editions du Seuil, 1999.

Symmons, Tom. The New Hollywood Historical Film: 1967–78 . Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Toplin, Robert B. History by Hollywood: The Use and Abuse of the American Past . University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Treacey, Mia E. M. Reframing the Past: History, Film and Television . Routledge, 2015.

Trochim, William M. K. “Positivism and Post-Positivism.” Research Methods Knowledge Base , 2006: n.p.

Vasey, Ruth. The World According to Hollywood, 1918–1939 . University of Exeter Press, 1997.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universiteit Antwerpen, Antwerp, Belgium

Patrick Cattrysse

Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

Emerson College European Center, Well, The Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Patrick Cattrysse .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Media, Film and Communication, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Davinia Thornley

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cattrysse, P. (2018). The Study of Historical Films as Adaptation: Some Critical Reflections. In: Thornley, D. (eds) True Event Adaptation. Palgrave Studies in Adaptation and Visual Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97322-7_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97322-7_2

Published : 27 September 2018

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-97321-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-97322-7

eBook Packages : Literature, Cultural and Media Studies Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Cultural Studies General

- Film Studies

Literature and Film: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Film Adaptation

ISBN: 978-0-631-23054-0

October 2004

Wiley-Blackwell

Robert Stam , Alessandra Raengo

Robert Stam is University Professor at New York University. His many books include Film Theory: An Introduction (Blackwell, 2000), Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media (with Ella Shohat, 1994), and Subversive Pleasures: Bakhtin, Cultural Criticism and Film (1989). With Toby Miller, he is the editor of Film and Theory (Blackwell, 2000) and The Blackwell Companion to Film Theory (2000).

Alessandra Raengo is finishing her PhD in the Cinema Studies Department at New York University. Her dissertation explores race and vernacular social criticism in American culture between 1945 and 1968. Among her publications are The Birth of Film Genres (1999) and The Bounds of Representation (2000), both multilingual volumes edited with Leonardo Quaresima and Laura Vichi.

- Brings together the very latest scholarship in the field of literature and film studies, written by leading international experts.

- Explores in detail a wide spectrum of novels and adaptations, from established classics ( The Grapes of Wrath , The Last of the Mohicans ) to genre works ( Dracula , Cape Fear ) to contemporary classics ( The English Patient , Beloved).

- Analyses individual films as well larger themes.

07 Adapting History and Literature into Movies

This essay offers an overview of adaptation, an initiation for the educated reader who is not a communications or film specialist. It will reference “The Social and Cultural Construction of Abraham Lincoln in U.S. Movies and on U.S. TV”—but mainly with an eye to the larger issue of cinematographic adaptation itself.

Apples and Giraffes

Literature and film, movies and books, compare like apples and giraffes, said contemporary American writer Dennis Lehane. 1 But they do compare. They do interbreed. As do history and film. But the question is: How and why do history, literature and movies fruitfully nourish one another? When apples, giraffes, and other exotica interbreed what results?

Many thousands of movies are adaptations from historical or literary sources. Hence the recent internet vernacular of “litflicks”—literature adapted into flicks, the flickering medium of the motion pictures. 2 History is generically dealt with by cinema in the epic, period, or historical film. Film historians generally distinguish the epic group from the strict historical group by its sheer size, expense, and the sumptuousness of the movie’s costumes and sets. The period film is distinguished by the production fact that it can be set in the far distant past or the immediate present, as in the Jazz Age, 1926 version of The Great Gatsby or with the achingly Sixties, 1969 film Zabriskie Point . 3

Although literature, history, and movies are distinct forms of communication thousands of solutions and accommodations have been found so they can get along and have fruitful relationships. The first key is the nature and tradition of adaptation itself. Tales evolve and one generation adjusts the stories of the past to the present time and to its modern needs and ways of story telling. “My dramas are but slices cut off from the great banquet of Homer’s poems,” wrote the Greek dramatist Aeschylus (525–456 B.C.). 4 But Aeschylus’ dramas were leaner and meaner, in search of a higher truth which synthesized moral opposites, profoundly simpler than anything all-embracing Homer ever wrote. For it is the singer, not the song, that makes the splendor of communication successful. And a story retold, as Aeschylus retold Homer, continues. What is beneath the surface of the story that has been told before and will be told again—a story that has been alive among humans for centuries or millennia?

Literature, History, and Movies

Consider how information exists and knowledge is distilled. How a story is told is as important as its subject matter. Thus, three fundamental points about how the nature of literature and history effect their relation to movies:

First, legend precedes historical fact. Did Nestor and Ajax in the Iliad ever actually exist and do what Homer claims they did? Until factual, textual proof is found this remains, at the least, an open question. The Iliad remains legend rather than history, literature rather than history, superstition rather than science. Hence, human culture as we know it shows that literature precedes history as a practice of inquiry, as a creative record of human events.

Second, a fundamental distinction exists between history and memory. History is then, memory is now. A judicious, critical management of documentary evidence allows history to get as close as possible to the facts of the past; then as it was then. Memory is the past remembered and reconstructed through the lens of the present and its building blocks. 5 Movies flourish in a popular, contemporary market place. They must entertain the sensibilities of the present. Anachronism is their delight and pleasure. Memory is their very breath. So history inevitably gets short-changed in movies—with some notable exceptions.

Third, with regard to the history of ideas, one distinguishes between an older meaning of literature as literacy and the cultivation of reading (dominant through the eighteenth century) and a newer reality and reference to literature as a body of writing which contrasts with erudition and which emphasizes wit, talent, and taste (which begins to dominate the older meaning by the end of the eighteenth century). 6 Story-telling movies that are not straight documentary or raw, live footage have a much stronger generic affinity to literature than to history. Thus the movie-history relation is more a connection rather than a similarity, an association rather than nearness. The difference is subtle but meaningful. The viewer can expect a movie to be like literature. But can you expect a movie to be history?

Two exceptions of note which prove the rule with regard to movies and history are documentary cinema and raw footage. Documentary cinema has a closer relation to history. Documentary can function like journalism or on-the-spot news, though news is “only the rough draft of history”—as publisher Phil Graham of The Washington Post once said. Conventional wisdom defines documentary as “relating to or found in documents: aiming at presentation of reality,” 7 “broadly: factual, objective.” 8

But look deeper and one often finds that the non-fiction film or photo which is about “real life” was treated subjectively and sometimes doctored just as much as a piece of fiction. Though documentary is relied upon as objective fact, as proven support for something, it can easily be a constructed, subjective artifact and be synonymous with social persuasion or propaganda. This is not a problem, but an asset for documentary, and a point to which this essay shall return. Raw footage is also known as “stock shot” and is film footage of actual, ordinary or exceptional events which is stocked away and then used as movie filler, a means to intensify mimesis in a fiction film or documentary, a way to cut production costs, or kept for historical record. One outstanding case of stock shot would be the Zapruder Film . This was the only live movie made of the John F. Kennedy assassination of November 22, 1963 by amateur cameraman and garment manufacturer Abraham Zapruder of Dallas, Texas. 9 This film has been used or referenced in about forty movies to date, including Oliver Stone’s 1991, bullying but engrossing movie JFK , a 1999, HBO Sopranos’ episode, and conspiracy theory documentaries of the last few years. 10

The vitality of adaptation and influence evolved in Western culture through various epochs down to the European Age of the Enlightenment, when the proprietary concept of plagiarism came into common play. Prior to that, new versions of old tales, such as European medieval romances, were considered to refurbish and refit stories that had been told before and would be told again and again. There was once a much stronger sense of the common property of culture. The change that came about during the European Enlightenment had to do with owning painting and art criticism, literature, natural philosophy, history, and music. 11

The originality, stylistic authority and proprietary rights of a composer and a composition became a major factor in the production, adaptation, and consumption of culture. This was capped by a new sense of individualism, a term and concept which did not come into common use in the English language until the early 1800s. 12 One result was the “self-made” author who could make a living from his writings and was deservedly proud that he could do so by selling his work to the public and did not have to toady to patronage. The Augustan poet, satirist, and translator Alexander Pope (1688–1794) was the first outstanding Anglo-American example of this. From his Homeric translations he made a net profit of the then very large sum of £10,000 and he bragged he could “. . . live and thrive Indebted to / no Prince or Peer alive.” 13

Precedents for plagiarism existed. Stealing from another person’s work among the literate elite in ancient Greece and Rome was taken as a cowardly sign that one lacked personal, creative integrity. Around the time Johann Gutenberg’s printing press was working (beginning in Strasbourg in the 1430s), the legal phenomenon of “letters patent” came into existence—a document from the monarch which conferred the privilege, or patent, to print, usually given to a Stationer’s Company or guild. It was the first Anglo-American law, the Occidental Copyright Law Statute of Queen Anne of England of 1710, which expressly guaranteed copyright. Which, in turn, was followed in the newly minted United States by the first U.S. Copyright Act of 1790. 14

The concept and practice of adaptation as a break from the original creation, and not as a refitting flourished once copyright and plagiarism were written into the granite of the law. The term’s two-fold original meaning adapted to this cultural, social, and economic change. First by the Latin etymology of adaptation: ad —“near, adjacent to,” and aptus : “to fasten, to fit.” While the secondary, derived meaning of adaptation as something “broken up” and “remade totally anew” adapted to the newer social and commercial sense in a world where “capitalism” was also a new word.

Cultural History

Final introductory note: This essay about adapting history and literature into film is a cultural history approach to the question of cinematographic adaptation. It highlights concern for cultural translation, with how the culture and language of the past has been transformed into the present.

Culture is not handed on like a baton in a relay race from one generation to another or from one nation to another. As it evolves, culture has to be reproduced. “A culture does not have an independent inertia.” 15 In classical terms, cultural history is a secular humanist, Aristotelian approach to culture. My a priori assumption is that all knowledge is gained and perpetuated by the close association between the human mind, spirit, and body conditioned by the environment of its time. No Greater Power—from archetypes, to Godhead, to Platonic “forms”—exists independently of our sensible world, of our human need to construct, guide, give and get what we require as human beings. Man is his own maker.

The ancient art and craft of adaptive communication means recreation. Beneath the surface of a story refurbished over the ages and updated by different media lies a heritage of useful knowledge which adds to well-being in proportion as it is communicated. The genesis of the forms themselves can now help us to figure out the relationship of literature to film, the written word to the visual image.

Malleable Forms and Contents

Protean Forms and Authenticity

In his classic study Novels Into Film (1954), George Bluestone argued that the novel is “protean because it has assimilated essays, letters, memoirs, histories, religious tracts, and manifestoes” 16 —and one may add: the folk tale, the play, epic, and romance. Film itself is also specially “protean because it has assimilated photography, music, dialog, the dance”—and one may add: literature and history, painting, visible color, audible sound, and the art of inducing a sleeplike trance.

But movies do more. Movies are distinct from both literature and history because a movie has to move on multiple tracks, combine two or more types of media. As the German American film theorist and perceptual psychologist Rudolf Arnheim (1904–2007) noted in 1938, a movie is a composite work of art which:

. . . is possible only if complete structures, produced by the media, are integrated in the form of parallelism. Naturally, such a ‘double track’ will make sense only if the components do not simply convey the same thing; they must complete each other in the sense of dealing differently with the same subject; each medium must treat the subject in its own way, and the resulting difference must be in accordance with those that exist between the media. 17

History has also assimilated different genres. But, more importantly, it has traditionally been considered to be of two sorts: the biographies of great people or the story of ordinary folk. This began as the long-standing distinction in history between the work of Thucydides and that of Herodotus. Thucydides wrote heroic political history which emphasized the interrelations of the highly privileged. Thucydides reserved the moral drama of historical tragedy for an elite (as did literature until the modern, industrial age). Herodotus’ work was pluralistic, polyvalent, democratic. His tone was colloquial rather than terse, his narrative was far more about people than abstractions. In the Herodotean words of Henry Ford’s amanuensis William John Cameron (1878–1955): “The history of historians is usually bunk . . . but history that you can see is of great value. It is not the past of the books, . . . it is the past of living men and women; folks pretty much like ourselves.” 18 The contemporary American cultural historian Karl Krober has updated these issues in his study Make-Believe in Film and Fiction (2006) and argued for a different set of contrasts regarding the fundamental differences between literature and movies. Literature, he claims, makes it easier to share subjective fantasies, it frees the mind from limits of time and space, and it dramatizes the ethical significance of ordinary behavior, while simultaneously intensifying readers’ awareness of how they themselves think or feel. Movies’ uniquely magnify movements to produce stories which are specially potent in exposing hypocrisy, problems of criminality in modern society, and the relation between nature and man, the private self and the natural environment. 19 In other words, movies are more like journalism—the rough draft of history. The American playwright, movie director and screenwriter David Mamet (1947– ) has put the matter more succinctly in basic building terms. Literature, he said (and a play in particular) “is like an airplane. You don’t want to have any extra parts there.” While “a movie’s more like a car; it can probably sustain a couple extra parts to make it look pretty.” 20

The protean blends of history and cinema match nicely in the epic spectacular. The movie set in an epic—the film’s stage arrangement, scenery, props, place and costumes—takes on such force of character that it has the strength of an actual subject. Like a documentary, an epic spectacular owes a great deal of its effectiveness to the coherence and apparent authenticity of all elements in the film. The set is a spine that must exist so the body of the movie can exist. The director must bring spine and body to life. And so history appears to be reborn in the epic movie. 21

Authentic setting both enhances the veracity of an epic movie and gives the popular audience a tantalizing insight into the people and places that helped to make history happen. MGM’s 1959 Ben Hur sent out second unit scouts to film locations in Italy, along with England, France, Mexico and Spain, to achieve this. Of course, this was a gross factual error. The creative point was not to achieve one hundred percent factual, historical accuracy, but to attain the emotional perspective of epic space. In character terms, the late Charlton Heston was beautifully cast with his stern, hawk-like features, intense, stoic expression, and sinewy, athletic frame. The point being that historical accuracy in the movie context should be judged by different rules than the dialectical, academic context of history. “There is no point in comparing the relative value of the various media. Personal preferences exist, but each medium reaches the heights in its own way.” 22 In the movie business, as opposed to the history business, authentic does not mean factually erudite. It means coherence. It means history recast into fresh dramatic form. At its best, the epic spectacular combines heroic political history with pluralistic, polyvalent and democratic themes—as in David Lean’s superb Anglo-American production Lawrence of Arabia (1962). It is a movie business formula that has produced hokum and rubbish, but also cinematic masterpieces and cutting-edge advances in narrative form and multimedia technology. In American cinema, it is a formula that has worked from D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916) through the twentieth and twenty-first century Western, the Bible epic, war movie, sword and sandal Roman Empire film or British Empire movie, the disaster film, and the science fiction intergalactic adventure movie.

Word, Image, Technology

One last point about the material and conceptual nature of literature, history, and movies. Literature and history must have the word— logos . Their particular nature as media consists “precisely in the abstractness of language, which calls every object by the collective name of its species and therefore defines it in only a generic way, without reaching the object itself in its individual concreteness . . ., hence the spiritual quality of its vision, the acuteness and succinctness of its descriptions.” 23 As literature and history advance beyond their oral stage, they demand the written word (or print) conveyed by reading. The medium of movies needs images in motion which are conveyed by a projection on to a screen. In all works of art there is a hierarchy of media. For movies the image, iconos , dominates.

A movie gets to places literature and history do not. And then it delivers that place to its audience in a way literature and history cannot. The audience, in turn, must use their eyes for a movie to work. After all, are not literature and history forms of communication which are more available to a blind person? With literature and history the audience sees with their inner eye, not as much with their outer, physical eye. “Film creates a fully defined and immediate physical reality that requires dramatization and exploration; it brings characters visually realized into direct relationship with their environment and in immediate proximity to the viewer.” 24

Cinema also needs electricity. Movies could never have existed without the necessary technology. Print advanced literature beyond the spoken word and the written page and allowed mass media. But technology midwifed movies into their very existence. Technological determinism has played a much greater part in the creation of movies. From its modern inception, the technology also helps to distinguish the entertainment film from the documentary. In 1893 the American inventor and businessman Thomas Edison created the first film company to make and show movies to the public. The Edison Company filmed in a tar paper barn set on a swivel, in which the roof could be opened or closed so as to adjust to the sun. Edison’s unwieldy camera, the Kinetograph, was a large, fixed machine run by an electric motor to ensure smooth motion. The point here is that Edison’s “camera did not go out to examine the world; instead, items of the world were brought to it—to perform. Thus Edison began with a vaudeville parade: dancers, jugglers, contortionists, magicians, strong men, boxers, cowboy rope twirlers.” 25

In contrast, documentary cinema was first developed by Louis Lumière in 1895 by using the cinématographe camera which was a hundredth of the weight of Edison’s Kinetograph. The cinématographe was about the size of a small suitcase, very portable, and could film, print, or project. Edison’s movies were entertaining indoor performances. Lumière’s movies documented the world outdoors. His camera “was an ideal instrument for catching life on the run”— sur le vif , as Lumière put it. 26

The American film director, comedian and cartoonist Terry Gilliam has argued that the nineteenth century sense of cinema as a whole came from the flickering passages seen by riders in trains when they looked out at the passing landscape through the train window’s frame. 27 One technology inspired another. And without electricity in the 1890s neither the Lumière brothers in France nor Thomas Edison and George Eastman working together in America could have established the craft of filming and projection. (However, vigorous, mobile entertainment existed prior to the new technology—the street theater, the carnival, and the enthusiastic links of circus rings. So it was not the technology alone that provided the creative genesis.)

The novel dates back at least to Heliodorus (third century A.D.). In the long run the novel is a far more formal genre and has been a more creative medium than film. Both novel and literature are preindustrial arts, but movies are an industrial art. The novel also has a lengthy record as a class-oriented medium. For centuries the novel relied on the upper and middle-class elitism of literacy. Cinema was born as mass and popular cultures bloomed in urban civilizations in modern times. As critics have noted about cinema since its pre-World War One days of Nickelodeon entertainment, it is the most popular and democratic of art forms (although admission did not always cost only a nickel). The 1913 admission price to the spectacular movie Quo Vadis was the current equivalent of about $31.00. 28

Movies fed on the placenta of the popular, the common coin, and not on the support of a superior class. 29 Movies were ushered into existence by the common, human hunger for story. This is part of the special process which, together with other characteristics, helps to define American culture. “American man,” wrote Eric Hoffer, “is eminently a storyteller. His search for a purpose, a cause, an ideal, a mission and the like is largely a search for a plot and a pattern in the development of his life story—a story that is basically without meaning or pattern.” 30 Every American group creates stories about its own heroes and villains which help to reinforce and provide identity for the group. In its relatively short run compared to literature and history, the movie business has democratically catered to wider audience needs and market demands.

The Visual Book

At the risk of arguing by list, note that the illustrated book has been around for a very long time. The written text has a huge history of visual relationships. Indeed, has the written text ever not been illustrated? 31 For our American cultural history purposes a fascinating detail in this long chronicle is that the very first best seller in America was an illustrated book. Indeed, it was a very illustrated book: Francis Quarles’ Emblemes (1635) and Hieroglyphikes (1638). These were each an emblem book—a work of moral and religious verse based on Bible quotations in which the word text was matched by allegorical illustrations. Quarles’ Emblemes and Hieroglyphikes were the best emblem books produced in England in English, and undoubtedly in America as well. 32

Which is to say that America was ever a nation with a strong preference for visual communication, long before the cinema. The entertainment industry, with movies and TV in particular, are to the United States what wine is to France or oil is to Saudi Arabia. One reason why movies made such great headway in the United States was because of the nation’s pronounced national taste for and tradition of visual communication and storytelling. Once twentieth-century U.S. mass media was established in 1930—with electric sound recordings, radio and movies—non-fiction book titles outnumbered fiction titles. The greater part of storytelling moved to the new media.

Types of Adaptation

When adapting from literature to film, one begins with the raw stuff, the subject matter of a short story, novella, or novel, of a play, history, biography, or with a poem, song, or folk tale. It is all good because it is ready-made and market-tested. The characters and stories are already popular. Now they have to be mass-produced. Three types of adaptation follow: loose, faithful, or literal. 33 Adaptation is by nature a translation into a different medium which expresses itself by using a different group of techniques, essential materials, and rules of creative harmony.

The loose adaptation takes the raw stuff and reweaves it into a movie as the director, producer, or studio wishes and as the movie needs. Contemporary cultural norms are often a determining factor. The various adaptations of James Cain’s all-American novel The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) became more overtly sexual as the times—and countries of adaptation—changed. One could easily imagine an effective and even momentarily pornographic adaptation of this steamy, laconic crime thriller at some point in the future. 34 In The Postman Always Rings Twice libidinal action is the narrative’s existential pumping force. Its eros and thanatos are deliciously extreme and invite loose play. 35

One should wonder about action. Overall, are Americans and American cinema prone to loose adaptations because of an emphasis on action as an end in itself within the civilization? “I need a little less talk and a lot more action,” is a common State-side saying. And as Anglo-American actor Michael Caine claimed in his autobiography: “The British make ‘talking pictures;’ Americans make ‘moving pictures.’” 36 This is not universally true, but good enough to be a rule of thumb. In American national tradition, a movie is a mover and a shaker, it tries to provide emotional satisfaction for it audience. Example: The 1935 film version of Jack London’s excellent Call of the Wild —starring Clark Gable, Jack Oakie and Loretta Young, was a fine film in its own way (billed with the tagline: “An Epic Novel . . . An Epic Picture!”)—but it typically lacked the level of thoughtful backstory present in the novel. 37 Plus, the very popular buddy character in the movie, Short Hoolihan, was played by Jack Oakie (1903–1978). Oakie was the inveterate scene stealer with the charm of a big, friendly, flappy, hairy dog. He was the nation’s loveable, pudgy, all-American, good time “Okie” character of the era. “No matter how hard I worked all day, I could always find a party to go to,” he wrote in his autobiography Jack Oakie’s Double Takes . 38 Just as the actors Richard Roundtree in Shaft (1971) and Eddie Murphy in Beverly Hills Cop (1984) provided audience interest because they integrated a new kind of American into the mainstream—a back-talking, thoroughly male, self-confident, Black protagonist—so did Jack Oakie in his time and place blend in a hearty contemporary figure: a working-class, funny and eventually successful White guy from Oklahoma or the Red River Valley country. 39

Jack Oakie’s popularity was more important than the integrity of Jack London’s original text. After Hoolihan-Oakie was shown to die in Call of the Wild ’s world premiere held at the Cathay Circle Theater in Los Angeles (an action true to the novel), the audience was so upset that a new ending was provided for the movie in which Oakie lived, so the public (and MGM’s box office) would not be disappointed. And would Jack London, champion of the rough and tumble working class (who wrote: “affluence means influence”), have been upset? Why not let Hoolihan-Oakie live? A traditional condition of action rather than reflection in American cinema was specially true through the 1950s and 1960s. Then something changed. By that time over five hundred art house or art theater halls flourished in the U.S.A. showing foreign films: in the Boston, Massachusetts area, for example, the well-known Brattle Street Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Coolidge Corner Theater in Brookline, or the Paris Cinema on Boylston Street in Boston. There was both an artistic and a market message here.

The new generation of Baby Boomer U.S. audience and film makers were subsequently receptive to and incorporated into U.S. films the serious aesthetic and social intentions of non-U.S. movies. At one level, this distinction gradually dissolved between the reflective-artistic qualities of U.S. and non-U.S. films, and consequently the number of art theaters rapidly dwindled. At another level, the American need for action, star power, and contemporaneity which could justify loose adaptation remained. Examples of loose adaptation in American cinema would be: The Best Years of Our Lives (1945, directed by William Wyler—adapted from the prose poem Glory for Me by MacKinlay Kantor 40 ), King Creole (1958, directed by Michael Curtiz, loosely adapted from A Stone for Danny Fisher by Harold Robbins 41 ), or Disney’s Pinocchio (1940, loosely based on the original Italian version). The loose adaptation may add additional subplots and characters, change situation or setting. Some of the original, in spirit or in fact, still remains. Loose adaptation can also mean expanding only a few lines from an original text. The original Biblical story of David and Bathsheba—the approximately one thousand words of II Samuel 11: 2–27, 12: 1–24—is part of one of the oldest pieces of historiography in the Western world, II Samuel 9–20 and I Kings 11–22. It became the movie David and Bathsheba (1951, taglined: “For this woman . . . he broke God’s own commandment!”). 42 This loose adaptation of a Biblical text was earnest, austere and languid.

As often happens with folklore or Biblical texts, star power and storyline changes heightened the interest and drama of the plot. In the original Biblical version King David spies Bathsheba by chance: “And it came to pass in an eveningtide, that David arose from his bed, and walked upon the roof of the king’s house: and from the roof he saw a woman washing herself; and the woman was very beautiful to look upon.” (II Samuel 11.2) But in the adaptation directed by Henry King and written by Philip Dunne (which received the Academy Award nomination for Best Writing: Story and Screenplay), Bathsheba exposed herself on purpose in order to seduce David. Their subsequent betrayal was an expression of mutual complicity. The vicarious interest of the 1950s American women in the movie audience was heightened. Bathsheba was an agent, not just a victim. Like popular music and folk song, texts from the Bible, legends, or folklore have the nature of common property. Like popular song, the original text is anonymous or invented by an individual or group who yields it to the community. The story or song is then modified or taken apart in performance.

Arguably the most adapted source works are legends. Some film historians count the vampire legend as the single most adapted tale of all time. Could a legend be that tantalizing end point for history and beginning place for myth where all is possible? 43

The faithful adaptation takes the literary or historical experience and tries to translate it as close as possible into the filmic experience. Sometimes there are equivalents in film to the original way of saying or doing what happens in literature and history, and sometimes not. And “faithful” depends on the movie makers’ knack to be true to the original spirit of the raw stuff, the primary source. Faithful works from the inside out; loose works from the outside in. Loose has no problem with dismantling and reassembling, breaking up and remaking totally anew. Faithful wants to stay loyal to the intention of the original, to convey the heart and soul. So in a faithful adaptation, even if the movie went so far as to change the original story’s ending, the movie makers would want to make sure that they did not betray the core meaning.

Some outstanding twentieth century examples of faithful cinematic renditions of an original literary or historical text are: The Ox-Bow Incident (1943, directed by William Wellman; novel: 1940), The Grapes of Wrath (1940, directed by John Ford; novel: 1939), The Godfather (1972, directed by Francis Ford Coppola; novel:1969), The Man Who Would Be King (1975, directed by John Huston, from Rudyard Kipling’s short story of the same name 1888), The Dead (1987, directed by John Huston, from the story in Joyce’s Dubliners, 1914 ), Dances With Wolves (1990, directed by Kevin Costner, adapted from Michael Blake’s novel of the same name, 1986–1988.)

The faithful adaptation has the thorny problem of the narrator and the general commentary. The narrator is the good shepherd who guides the flock of meanings in the original, word-based text. How do you replace such an important figure without loosing direction? In Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath , for example, seventeen percent of the novel were general commentary. In the movie’s faithful adaptation by John Ford and Twentieth Century Fox there was no voice-over narrator in the filmic space. 44 But each medium worked perfectly well on its own terms. The movie Grapes of Wrath maintained a serious narrative tone. It had mature quality of cinematic sound, coloring, photography and casting which helped to replace and even enhance the historical novel’s original voice. Dorothea Lange’s 1930s pitch-perfect photographic style was incorporated by the film’s Director of Photography Gregg Toland. Alfred Newman’s musical score achieved superb shading. The casting of the Joad family was done with vigor and depth: Jane Darwell as Ma Joad, solid as oak, yet vulnerable in her strength; Henry Fonda,—as Steinbeck himself said: “A lean, stringy, dark-faced piece of electricity walked out on the screen and he had me. I believed my own story again.” 45 The public relations department at Twentieth Century Fox possibly pushed this maturity too far. They emphasized the serious nature of the movie’s subject when it was released by stressing that Grapes of Wrath was only for an adult audience. It was taglined: “The thousands who have read the book will know why WE WILL NOT SELL ANY CHILDREN TICKETS to see this picture!” 46

The social conventions of 1940 also did not allow John Ford to end Grapes of Wrath with the novel’s last scene of young Rose of Sharon baring her breast and suckling the starving man who “was about fifty, his whiskery face gaunt, and his open eyes . . . vague and staring” and who hadn’t eaten for about six days. But Ford did manage to end his version with the book’s characteristic note of spreading the milk of human kindness. The movie draws to a conclusion with a concise version of the novel’s chapter twenty-eight farewell scene between Tom Joad and his mother.

A strong expression of a literal adaptation is often a play performed as a movie. This includes movies filmed on stage and in performance (as in the Broadway Theater Archive series 47 ). Or it could be a play such as Arthur Miller’s Death of A Salesman (1949) which has been faithfully transmuted at least three times into cinema: in 1951 (directed by László Benedek, starring Frederic March as Willy Loman), in 1966 (directed by Alex Segal, starring Lee J. Cobb, who had already appeared in Miller’s original 1949 production), and then in 1985 (directed by Volker Schlöndorff, starring Dustin Hoffman). A good example of an outstanding historical play literally adapted to film is Sunrise at Campobello , 1960, adapted from the 1958 stage drama about Franklin Delano Roosevelt written by the politically engaged Dore Schary. 48

What happens to the play transferred to film? Well, a film has incredibly more space than a stage. A movie can literally take the scenic arrangement outside and the medium offers the director all sorts of tempting forms of physical and psychological expansion. Franklin Roosevelt’s dramatic walk without crutches on his crippled legs to the podium, with one hand on a cane and the other hand clutching his son’s arm, to deliver the 1924 Presidential nominating speech for Al Smith before thousands of spectators at the Democratic Party Convention within the huge dome of Madison Square Garden is suitably heightened in the movie version.

Film offers a variety of focused and sustained camera angles. It expands or contracts our experience by virtue of the absence of the space-time continuum. Shots in separate spaces are edited together. Different times can be spliced, joined, or blended. The everyday sequential chain of experience is removed, intensified, or rearranged. The environment—the viewing filter of a dark theater or a quiet room—enhances the experience. This can make the literal adaptation of a visually contained text, like the rooms in Death of a Salesman , claustrophobic. Yet, by doing so, it heightens the play’s inherent tone of psychological oppression and impending doom. Each version of Death of a Salesman is enhanced by cinematic techniques of expressionism.